Abstract

One-third of patients discharged from hospitals to skilled nursing facilities (SNF) are sent back to the Emergency Department (ED) within 30 days. Little is known about those patients who are discharged from the ED directly back to SNF. We considered these ED visits as potentially avoidable since they did not result in observation or hospitalization stay. Using a retrospective chart review of 1010 patients with ED visits within 14-days of discharge to SNF from University of Pennsylvania health system (UPHS) in 2020–2021, we identified 202 patients with potentially avoidable ED visits among medical and surgical patients. The most common reasons for these ED visits were mechanical falls (17.3%), postoperative problems (16.8%), and cardiac or pulmonary complaints (11.4%). Future interventions to decrease avoidable ED visits from SNFs should aim to provide access for SNF patients to receive timely outpatient lab and imaging services and postoperative follow-ups.

INTRODUCTION

One in five adults hospitalized in acute care hospitals is discharged to skilled nursing facilities (SNF).1,2 Patients who qualify for post-hospitalization SNF care frequently need additional skilled nursing and/or physical rehabilitation to return to their baseline after hospitalization. Patients discharged to SNF tend to be older, have more medical comorbidities, and are almost twice as likely to experience a postdischarge Emergency Department (ED) visit compared with community discharges.3 In 2016, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services added nursing home ED visit rates to the list of quality measures of nursing home performance.4 In 2017, 21.8% of patients discharged to SNFs for postacute care were re-hospitalized within 30 days of SNF admission, and 12.0% had at least one ED visit that did not result in rehospitalization or observation stay.5 Health systems aiming to reduce unnecessary ED use may want to target interventions to patients with the latter category of ED visits – those that are discharged from ED back to SNF. Thus, to inform interventions that could reduce unnecessary ED use, we aimed to characterize potentially avoidable ED encounters for SNF patients.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective analysis of 1010 consecutive patients who had an ED visit within 14 days of discharge to SNF from the six UPHS hospitals between September 2020 and September 2021. Of the 1010 patients who had ED visits, 522 patients (51.7%) were admitted from the ED to inpatient services, 246 patients (24.3%) were triaged to an observation stay, and 242 patients (24.0%) were discharged from the ED back to SNF. Of these 242 patients, 40 were excluded because they did not present directly from SNF, but rather from home, an outpatient clinic, or dialysis center. The remaining 202 charts were reviewed to abstract the patient demographics and clinic al characteristics. Using a standardized abstraction instrument, two reviewers (YT and VA) independently abstracted a 10% random sample of the charts, with no disagreement observed between the two reviewers. The rest of the charts were reviewed by one reviewer. This study was reviewed by the UPHS Institutional Review Board and was determined to be a quality improvement initiative.

RESULTS

Of the 202 patients discharged to 54 SNFs in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware from six UPHS hospitals, 56.4% had initial hospital stays for medical conditions, and the remaining 43.6% underwent surgical procedures. Four of the 54 SNFs accounted for more than half of the potentially avoidable ED encounters. Table 1 shows our patient characteristics. The average age was 71.7 (SD 13.8), and 51.5% of the patients were female. Compared to patients in the medical subgroup, patients in the surgical subgroup are younger (68.7 vs. 74.0, p = .009), more likely to be instructed by an outpatient provider to return to ED (12.5% vs. 0.9%, p < .001), and more likely to receive a specialty consultation in the ED (45.5% vs. 8.8%, p < .001).

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics.

| Overall | Medical | Surgical | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients, N (%) | 202 (100%) | 114 (56.4%) | 88 (43.6%) | N/A |

| Age, mean (SD) | 71.7 (13.8) | 74.0 (14.5) | 68.7 (12.2) | .00861 |

| Sex, N (%) | ||||

| F | 104 (51.5%) | 56 (49.1%) | 48 (54.5%) | .442 |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 109 (54.0%) | 63 (55.2%) | 46 (52.3%) | .323 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 87 (43.0%) | 46 (40.4%) | 41 (46.6%) | |

| Other | 6 (3.0%) | 5 (4.4%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Insurance, N (%) | ||||

| Medicaid | 39 (19.3%) | 17 (14.9%) | 22 (25%) | .0613 |

| Medicare | 117 (57.9%) | 74 (64.9%) | 43 (48.9%) | |

| Others | 46 (22.8%) | 23 (20.2%) | 23 (26.1%) | |

| Initial hospitalization length (days), mean (SD) | 9.9 (8.5) | 10.4 (9.1) | 9.2 (7.7) | .281 |

| ED return time (days), mean (SD) | 5.3 (4.2) | 5.7 (4.2) | 4.8 (4.1) | .151 |

| ED return instructed by outpatient provider, N (%) | 12 (5.9) | 1 (0.9%) | 11 (12.5%) | <.0012 |

| Weekends/holidays, N (%) | 58 (28.7%) | 28 (24.6%) | 30 (34.1%) | .142 |

| Cases involving consultation in the ED, N (%) | 50 (24.8%) | 10 (8.8%) | 40 (45.5%) | <.0012 |

| Patients requiring treatment in the ED, N (%) | 55 (27.2%) | 25 (21.9%) | 30 (34.0%) | .0542 |

| Patients with outpatient appointments between hospital discharge and ED visit, N (%) | 23 (11.4%) | 11 (9.6%) | 12 (13.6%) | .382 |

| Patients with planned hospice, N (%) | 3 (1.5%) | 3 (2.6%) | 0 (0%) | .262 |

Mann-Whitney U test.

Fisher's test.

Mantel-Haenszel test.

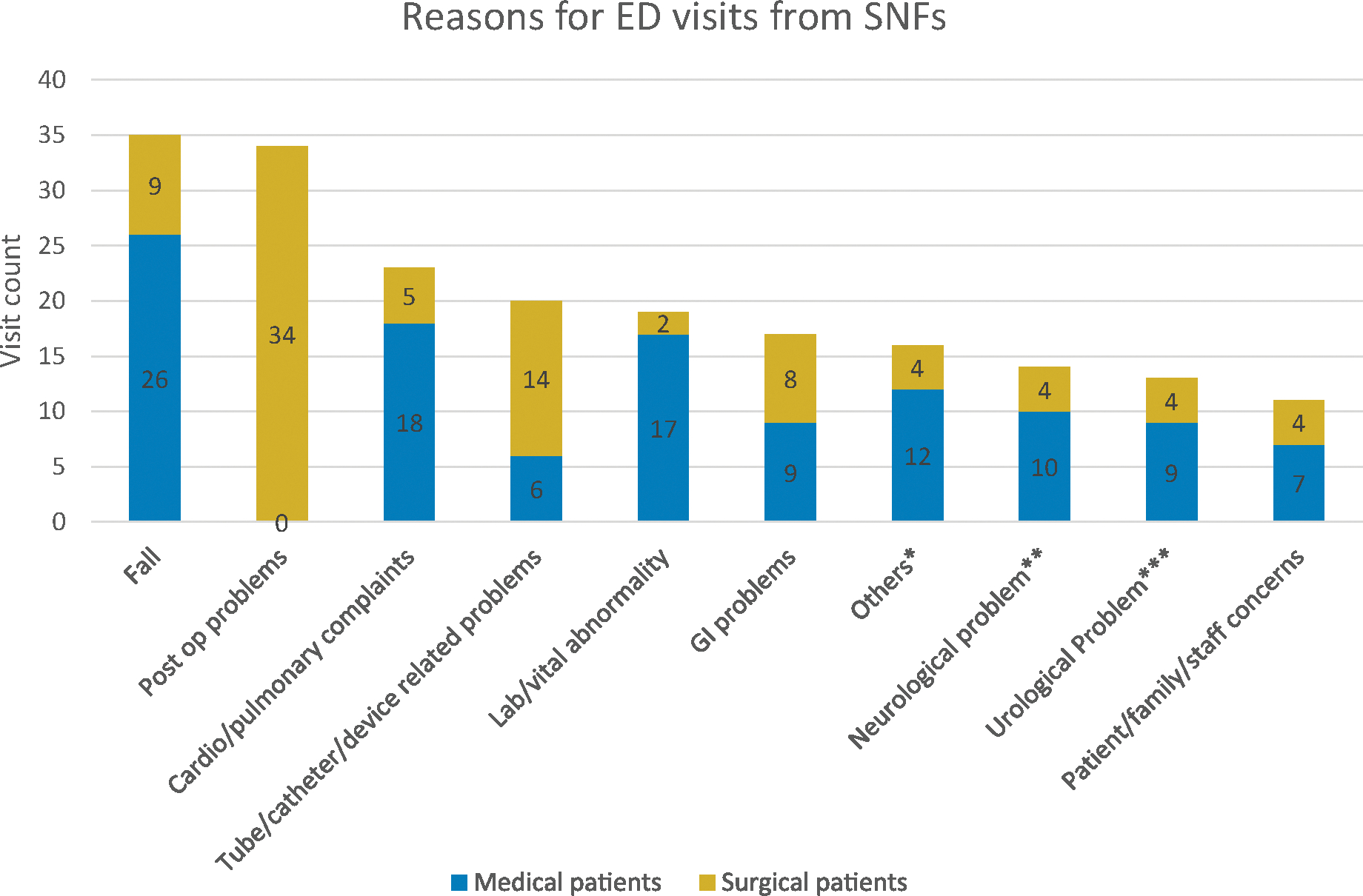

The most common reasons for return ED visits from SNFs for the overall patient group were mechanical falls (17.3%), postoperative problems (16.8%), and cardiac/pulmonary complaints (11.4%) (Figure 1). Of the 35 patients who had mechanical falls at SNFs, all patients had CT head in the ED without findings of intracranial bleed. Six patients (17.1%) needed skin laceration repair, and two needed finger splinting; the other 27 (77.1%) did not require any procedural intervention. Of the 34 patients with postoperative symptoms (e.g., pain, bleeding, drainage, fever), 28 patients (82.0%) had surgical consultation in the ED. Eight patients (23.5%) received interventions such as a dressing changes, suture removal, closed reduction of a dislocated joint, or starting oral antibiotics. Among patients with cardiac/pulmonary complaints including sudden onset chest pain, dyspnea, or palpitations, one had a surgical consultation for a breast abscess requiring incision and drainage, the other patients were discharged without any procedural interventions or new medications.

FIGURE 1.

Reasons for return ED visits from short-term nursing facilities *Others include allergic reaction, epistaxis, abscess, report of assault, transition to hospice. **Neurological problems include altered mental status, lightheadedness, headache, and tremors. ***Urological problems include urinary retention, hematuria, and urinary tract infection.

Comparing the medical and surgical subgroups, tube/catheter/device-related problems (16.0%) were more common among surgical patients, while abnormal vital signs or lab results (15.0%) were more common among medical patients. Of the 20 patients with device or catheter malfunction (e.g. feeding tube, tracheostomy, central line), 8 (40.0%) required subspecialty consultations, and 15 (75.0%) received procedural interventions, including feeding tube replacement, tracheostomy repositioning, and central line exchange. Of the 19 patients with abnormal vitals/labs, 3 (16.0%) required blood transfusion, and 1 (5%) received potassium repletion. The other 15 (68.0%) did not receive any new medications.

DISCUSSION

In this study, one in five ED visits from SNFs resulted in same-day discharge back to SNF. Although patients discharged to SNFs receive more intensive skilled nursing and rehabilitation services compared with patients in the community, they encounter barriers to timely evaluation outside of the ED setting. Thus, there is an urgent need to eliminate barriers to care in place at SNFs to reduce ED transfers.

Barriers to care in place at SNFs include the limited availability of clinicians trained to evaluate SNF patients in person or virtually, especially after hours. Second, many SNFs face financial barriers and staffing shortages that preclude the use of virtual consultations for urgent concerns. Hospitals may be able to address these problems by expanding virtual consultation infrastructure and strengthening health information exchange with local SNFs to ensure they have detailed discharge instructions, which may prevent some ED visits. Third, although SNFs contract with mobile labs and imaging services for residents, the availability of diagnostic testing on an urgent basis is variable. For example, on-site phlebotomy and imaging services for X-rays, ultrasounds, and EKGs may be available during the day but unavailable after business hours. Follow-up of urgent results after-hours and decisions regarding further management is limited at SNF depending on staff and service availability. Furthermore, outpatient testing costs typically come out of SNF reimbursement, so SNFs have a financial incentive to defer expensive CT or MRI imaging to the ED.

Initiatives such as the INTERACT program have attempted to implement guidelines and communications tools to help SNF staff identify and triage acute clinical deterioration. INTERACT was associated with fewer potentially avoidable hospitalizations from SNF, but there was no change in ED visits.6 One potential explanation for the mixed findings may be an unmet need for urgent diagnostic testing for SNF patients. Recent quality improvement projects have shown feasibility and overall improvement in SNF care. These have included an urgent care model including an on-site advanced care provider for help with triage and management of patients with new clinical deterioration, and an emergency care model in which a multidisciplinary team helps with triage and acute intervention at SNF to prevent avoidable ED transfers.7,8 Part of the promise of these models may be related to their ability to identify and address the need for urgent diagnostic testing in SNF patients.

Nonetheless, some patients benefited from referrals to ED despite being discharged back to SNF. They were mainly patients sent to ED for tube/catheter-related problems. Although timely access to outpatient surgery or infusion centers may enable SNF patients to bypass the ED to obtain these services, most centers would find it challenging to coordinate this care outside of the ED. Another example of this may be a patient with a high-risk fall for whom imaging was indicated but would not be able to be completed in an SNF in a timely manner. While some falls require urgent evaluations that must be completed in the ED, many patients who fall do not require subsequent interventions or prolonged observation in the ED, as evidenced by the frequent discharge back to SNF observed in this study. Nevertheless, these patients are at a high risk of falling again. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) fall management program for nursing facilities shifts the fall response from a crisis management mode to a proactive risk reduction mode for those patients.9

A limitation of our study is that it was a single health system retrospective study. However, this health system included multiple hospitals ranging from an academic teaching hospitals to community hospitals, both in suburban and urban settings. Another limitation stems from the retrospective nature of our analysis. Prospective work measuring outcomes of patients in SNFs with access to same-day diagnostic testing and subspecialty consultation via telemedicine versus those without access to these services would better assess the role of these services in ED use from SNFs. Additionally, our study reflects data collected during the COVID pandemic, which was characterized by severe staffing shortages in SNFs. It is possible that potentially avoidable ED encounters might have been exacerbated due to COVID staff shortages at SNFs.

Understanding the most common reasons why SNF patients return to the ED could help guide interventions to minimize unnecessary ED use. Our findings demonstrate that some SNF patients could benefit greatly from better access to same-day physician evaluation and diagnostic testing, as well as telemedicine for specialty care. This could potentially be achieved with a model in which SNFs partner with acute care hospitals to coordinate urgent tests and diagnostic imaging in a timely fashion and have designated SNF providers follow up on the results and arrange necessary outpatient appointments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Kira Ryskina is supported by grant NIA R01AG066841.

Funding information

National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Number: R01AG066841

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen LA, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, et al. Discharge to a skilled nursing facility and subsequent clinical outcomes among older patients hospitalized for heart failure. Circ: Heart Failure. 2011;4(3):293–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tian W (AHRQ). An all-payer view of hospital discharge to postacute care, 2013. HCUP Statistical Brief #205. May 2016. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb205-Hospital-Discharge-Postacute-Care.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venkatesh AK, Gettel CJ, Mei H, et al. Where skilled nursing facility residents get acute care: is the emergency department the medical home? J Appl Gerontol. 2021;40(8):828–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nursing home compare claims-based quality measure technical specifications, April 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/Downloads/Nursing-Home-Compare-Claims-based-Measures-Technical-Specifications-April-2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saliba D, Weimer DL, Shi Y, Mukamel DB. Examination of the new short-stay nursing home quality measures: rehospitalizations, emergency department visits, and successful returns to the community. Inquiry. 2018;55:46958018786816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kane RL, Huckfeldt P, Tappen R, et al. Effects of an intervention to reduce hospitalizations from nursing homes a randomized implementation trial of the INTERACT program. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1257–1264. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liggett A, Medved D, Dobschuetz D, Lindquist L. Applying an urgent care model to the skilled nursing facility setting. JAMDA. 2022;23(3). doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.01.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brickman KR, Silvestri JA. The emergency care model: a new paradigm for skilled nursing facilities. Geriatr Nurs (Minneap). 2020;41(3):242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2019.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agency for healthcare research and quality: the falls management program: a quality improvement initiative for nursing facilities. https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/settings/long-term-care/resource/injuries/fallspx/man2.html.