Abstract

Active immunotherapy of cancer requires the availability of a source of tumor antigens. To date, no such antigen associated with lung cancer has been identified. We have therefore investigated the ability of dendritic cells (DC) to capture whole irradiated human lung tumor cells and to present a defined surrogate antigen derived from the ingested tumor cells. We also describe an in vitro system using a modified human adenocarcinoma cell line (A549-M1) that expresses the well-characterized, immunogenic influenza M1 matrix protein as a surrogate tumor antigen. Peripheral blood monocyte-derived DC, when co-cultured with sub-lethally irradiated A549 cells or primary lung tumor cells derived from surgical resection of non-small cell carcinoma (NSCLC), efficiently ingested the tumor cells as determined by flow cytometry analysis and confocal microscopic examination. More importantly, DC loaded with irradiated A549-M1 cells efficiently processed and presented tumor cell-derived M1 antigen to T cells and elicited antigen-specific immune responses that included IFNγ release from an M1-specific T-cell line, expansion of M1 peptide-specific Vβ17+ and CD8+ peripheral T cells and generation of M1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL). We also compared DC loaded with irradiated tumor cells to those loaded with tumor cell lysate or killed tumor cells and found that irradiated lung tumor cells as a source of tumor antigen for DC loading is superior to tumor cell lysate or killed tumor cells in efficient induction of antigen-specific T-cell responses. Our results demonstrate the feasibility of using lung tumor cell-loaded DC to induce immune responses against lung cancer-associated antigens and support ongoing efforts to develop a DC-based lung cancer vaccine.

Keywords: Dendritic cells, Lung cancer, Cancer vaccine, Immunotherapy

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in both men and women in the United States. Conventional treatments for lung cancer include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy used alone or in combination. Despite the increasingly intense application and continuous modification of these approaches, the overall cure rate for lung cancer remains poor, especially for patients with advanced disease [2, 10]. Thus, the need to explore new treatment options is paramount.

Recent clinical studies have shown that immunotherapeutics with DC-based cancer vaccines have the potential to improve patient outcome for a wide range of tumor types, including melanoma, B-cell lymphoma, multiple myeloma, fibrosarcoma, kidney cancer and prostate cancer [3, 12, 14, 18, 19, 22, 29, 33, 35, 44]. DC are potent antigen-presenting cells uniquely capable of inducing both primary and recall immune responses, and they are key to stimulating clinically meaningful antitumor immunity. Increasing evidence has demonstrated that DC, when loaded with tumor antigens, are able to process the loaded antigens and present antigenic epitopes to T cells, resulting in the induction of tumor-specific CTL and antitumor immunity.

To date, many methods have been developed or evaluated for loading tumor antigens to DC [48]. The choice of method is largely dependent on the type of DC vaccine to be developed, the availability of defined tumor antigens or antigenic peptide epitopes and the supply of tumor materials. For those tumor types for which no defined tumor-specific antigens are available, such as lung cancer, loading DC with whole tumor cells is a practical choice. It has been shown that dendritic cells can efficiently phagocytose various forms of tumor cells, including live, apoptotic and necrotic tumor cells and acquire tumor antigens from the phagocytosed tumor cells [1, 4, 5, 16, 23, 24, 37]. Human DC loaded with tumor cells derived from either fresh tumor tissues or established tumor cell lines have induced tumor-specific CTL in vitro for renal cell carcinoma [23], melanoma [7, 8, 21], squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck [16] and acute myeloid leukemia [42]. In mouse models, CTL induction and protective antitumor immunity with tumor cell-loaded DC were also demonstrated in vivo [8, 24, 31, 34, 41]. To date, no studies have addressed the use of this approach for lung cancer. In this study, we assessed the feasibility of developing a DC-based vaccine for the treatment of lung cancer. Using a well-characterized, immunogenic influenza matrix protein [27] as a surrogate tumor antigen, we demonstrated the efficiency of DC in acquiring and presenting antigenic epitopes derived from the phagocytosed irradiated lung tumor cells. The results provide insight into the development of alternative strategies for treatment of lung cancer and extend the repertoire of tumor types that may be suitable for the development of DC-based cancer vaccines.

Materials and methods

Cells, cytokines and antibodies

Human lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549 was maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS). Primary lung tumor cells were prepared from surgical resection of the non-small cell carcinoma by digestion of the tumor tissue in an enzyme cocktail containing Pulmozyme (Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, Calif.) and collagenase (Advanced Biofactures, Lynbrook, N.Y.). For DC loading, lung tumor cells were either treated with a sub-lethal dose of γ-irradiation (20,000 rads; 137Cs-source), heat killed (65 °C, 30 min), or subjected to four freeze-thaw cycles to generate cell lysate. Tumor material was added directly to the DC culture flask on day 5 or 6 of culture. T cells specific for an immunodominant, HLA-A0201-restricted influenza matrix protein M1 peptide (M58-66, GILGFVFTL) were generated in our laboratory by repeated stimulation of the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from an HLA-A0201+ normal donor with the M1 peptide. These cells were maintained routinely in AIM-V medium supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated human AB serum, 20 U/ml IL-2 and 5 ng/ml IL-15 and periodically re-stimulated with the M1 peptide-loaded DC to retain the peptide specificity.

Cytokines used in the study are granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Immunex Corp., Seattle, Wash.), interleukin (IL)-4 (Peprotech, Inc., Rocky Hill, N.J.), interferon-γ (IFNγ) (Pierce Endogen, Rockford, Ill.), IL-2 (Peprotech) and IL-15 (Peprotech).

Most fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies used for FACS analysis were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.). These are antibodies for CD11c, CD40, CD80, CD83, CD86, HLA-ABC and HLA-DPDQDR. FITC-labeled anti-Vβ17 antibody was purchased from Beckman Coulter (Brea, Calif.). Antibodies for Western blot were anti-β-actin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-influenza-matrix (ViroStat, Portland, Me.). Antibodies used in ELISA assays for IL-12(p70), IL-10 and IFNγ were all purchased from Pierce Endogen. Anti-cytokeratin antibody was obtained from Becton Dickenson Immunocytometry Systems (San Jose, Calif.).

Infection of A549 cells with adenoviral vector expressing M1 protein

To modify A549 cells to express the influenza M1 protein, cells were infected with a non-replicating adenoviral vector encoding M1 protein (Adv-M1). Briefly, sub-confluent cultures of A549 cells were infected with the recombinant adenovirus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 for 5 h at 37 °C in a CO2/humidified incubator. After infection, the medium containing the virus was removed and replaced with fresh RPMI/1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. The cells were cultured for another 24 h, then harvested, irradiated and used to load DC. Western blot analysis confirmed the expression of the M1 protein by the infected cells. Infection of A549 cells with an adenovirus expressing a green fluorescent protein (Adv/GFP) was included as a control. Flow cytometric analysis and fluorescent microscopic examination confirmed the expression of GFP in ≥ 97% of cells 24 h after infection.

Generation of peripheral blood monocyte-derived DC

PBMC were isolated from the leukapheresis of normal HLA-A0201+ donors by Histopaque-1077 density gradient centrifugation. Monocyte-derived DC were generated from PBMC as described previously [28]. Briefly, PBMC were incubated in tissue culture flasks for 1 h at 37 °C in Opti-MEM medium (Life technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) supplemented with 1% heat-inactivated plasma. After incubation, non-adherent cells were removed, and adherent cells were cultured for 5 or 6 days in X-VIVO 15 medium (BioWhittaker, Inc. Walkersville, Md.) containing 500 U/ml GM-CSF and 500 U/ml IL-4 to generate immature DC. To induce maturation, the cells were stimulated with 2.7–4.1×105 cfu/ml Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG-Tice, Organon Teknika, Durham, N.C.) and IFNγ (1,000 U/ml) for 18–24 h.

Assay for uptake of lung tumor cells by DC

A549 and primary lung tumor cells were labeled green with PKH67 using a Green Fluorescent Cell Linker Mini Kit (Sigma) as per the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were then irradiated, mixed with immature or mature DC at a ratio of 1:1 and incubated for varying lengths of time. To assess tumor cell uptake, DC were collected, stained with a PE-labeled anti-CD11c antibody (red) and analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACS-Calibur (Becton Dickinson).

Confocal microscopy

DC were loaded with PKH67-labeled, irradiated A549 or primary lung tumor cells for 24 h, and then adhered to glass coverslips for 2 h at 37 °C. Adherent cells were washed once with PBS, then fixed for 30 min at room temperature with PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 120 mM sucrose. The fixation reaction was stopped by washing the cells with 50 mM NH4Cl in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Following two additional washes with PBS, the cells were stained with an anti-human CD11c antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 568 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Ore.). After staining, the cells were washed twice with PBS and mounted on slides with 15 μl of DABCO-containing mounting buffer (Molecular Probes). Samples were analyzed at the Scientific Imaging Lab at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Seattle, Wash.) using a wide-field epifluorescent/brightfield microscope (IX70, Olympus), operating on the DeltaVision Deconvolution Image Restoration Microscopy System and software (SoftWorx, v2.5, Applied Precision, Issaquah, Wash.).

Western blot

Adenovirus-infected and control A549 cells were lysed with a buffer containing 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 100 μg/ml PMSF and 0.02% sodium azide [36]. Proteins from an equivalent number of cells were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto an Immobilon-P PVDF membrane (Millipore Corp, Bedford, Mass.). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked by incubation of the membrane overnight at 4 °C in TBS containing 5% nonfat dry milk. The membrane was then incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-influenza-matrix protein and anti-β-actin antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation for an additional hour with an HRP-conjugated goat-anti-mouse IgG (KPL, Gaithersburg, Md.). The membrane was washed extensively with TBS plus 0.5% Tween-20 after each incubation. The influenza M1 and the β-actin proteins on the membrane were visualized with LumiGLO Chemiluminescent Substrate (KPL) and exposure to Kodak BioMax Light film (Sigma).

T-cell stimulation assays

Immature DC with or without tumor cell loading were added to 48- and 24-well plates with 1×105 and 2×105 DC per well, respectively. DC were then matured with BCG and IFNγ for 18–24 h as described above. In experiments using transwell chambers (Corning, Corning, N.Y.) to prevent cell-cell contact during DC loading, DC were cultured in the lower chamber of a 24-well plate and the irradiated A549-M1 cells were added in equal number to the upper chamber. After 24 h, the upper chamber containing tumor cells was removed and the DC matured. After maturation, the wells were rinsed three times with PBS to remove remnant BCG and IFNγ.

To assay for IFNγ release from M1 peptide-specific T cells, the T cells (1×105/well) were added to DC in the 48-well plate in a total volume of 0.5 ml AIM-V medium supplemented with 5% human AB serum. After incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, 200 μl of supernatant from each well was collected and assayed for IFNγ release by ELISA.

To determine the expansion of the M1 peptide-specific Vβ17+ CD8 T cell, MHC class II+ cell-deplete PBMC (≥84% CD3+ cells) from a matched HLA-A0201 donor were added to DC in the 24-well plate at a concentration of 2×105 per well in above AIM-V medium plus IL-2 (20 U/ml) and IL-15 (5 ng/ml). The cells were then incubated at 37 °C for 8–10 days. During the incubation, half of the medium in each well was replaced with fresh medium every 2–3 days. After incubation, cells were harvested, counted and stained with FITC-labeled anti-Vβ17 and PE-labeled anti-CD8 antibodies. The percent Vβ17+CD8+ T cells was determined by FACS analysis, and the absolute number of Vβ17+ CD8 T cells in each well was calculated by multiplying the percent Vβ17+CD8+ cells with the total number of cells counted.

Assays for cytokine production

ELISA assays were used to measure IL-12 and IL-10 production by DC and IFNγ release from M1 peptide-specific T cells. Briefly, 96-well plates were coated overnight at 4 °C with anti-human IL-12(p70), anti-human IL-10 or anti-human IFNγ antibodies at 1–3 μg /ml in PBS (pH 7.4). Nonspecific binding sites were then blocked with assay buffer (4% BSA in PBS, pH 7.4) and the plates rinsed with wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl; pH 8.0 and 0.2% Tween-20). Culture supernatants (50 μl) were added in duplicate wells followed by, without washing, 50 μl biotin-labeled anti-human IL-12, anti-human IL-10 or anti-human IFNγ antibodies. The reaction of cytokine and antibody was detected by incubation of the plates with streptavidin-HRP for 1 h and then with OPD (O-phenylenediamine) or TMB (3, 3', 5, 5'-tetramethylbenzidine) substrate solution for 30 min. Color development was stopped with 0.18 M H2SO4, and absorbance was determined at 450 nm using an EL-340 Bio Kinetics Microplate ELISA reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc, Winooski, Vt.). Unless indicated otherwise, all cytokine and antibody binding steps were carried out at room temperature for 1 h and were followed by washing the plate at least three times with wash buffer. Antibodies were diluted in assay buffer and used at pre-determined concentrations.

Cytotoxicity assay

T2 target cells were pulsed with or without 10 μg of M1 peptide for 1 h at 37 °C in a volume of 0.5 ml, washed to remove excess peptide and then labeled with 100 μCi of sodium [51Cr] -chromate (PerkinElmer, Wellesley, Mass.) for 1 h at 37 °C. Labeled cells were washed three times and plated in triplicate wells at 1,000 cells/well in 100 μl AIM-V medium containing 5% human AB serum in a round-bottomed 96-well plate. Effector cells from Vβ17+CD8+ T cell expansion cultures were added to the corresponding wells in a final volume of 0.2 ml/well to give effector:target (E:T) ratios of 50:1, 10:1 and 2:1. After a 4-h incubation, supernatant (35 μl/well) was transferred to a lumaplate and counted on a TopCount NXT Microplate Scintillation and Luminescence Counter (Packard BioScience, Meriden, Conn.). Spontaneous and total releases of 51Cr were determined from the supernatants of the target cells incubated with medium alone and 2% Triton X-100, respectively. Specific lysis was calculated as follows: % specific lysis = (sample release-spontaneous release)/(total release-spontaneous release) ×100. Percent killing of unpulsed T2 cells was subtracted from that of M1-pulsed T2 cells. Spontaneous release did not exceed 6%.

Results

Immature DC efficiently capture irradiated lung tumor cells

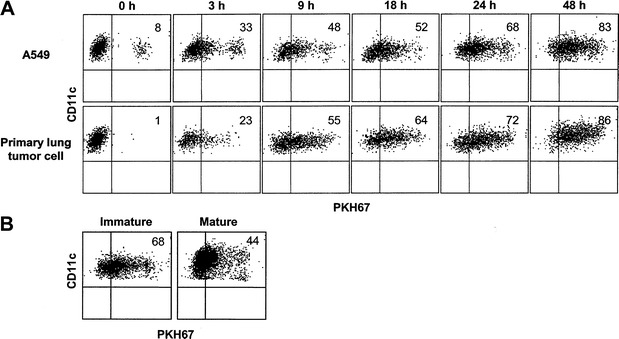

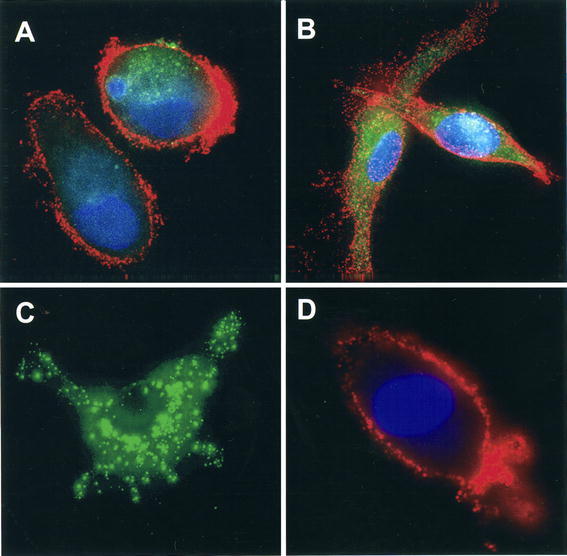

To determine the capacity of monocyte-derived DC to capture irradiated lung tumor cells, we cultured immature DC with an equal number of PKH67-labeled, irradiated A549 cells or primary non-small cell lung carcinoma cells for a period of time from 0 to 48 h. At various time points, the cells were harvested and stained with a PE-labeled anti-human CD11c antibody. DC that captured lung tumor cells acquired the PKH67 stain and were identified as CD11c+PKH67+ double positive cells by FACS analysis. As shown in Fig. 1A, the percentage of DC that captured A549 cells increased with increased time of loading, reaching 83% double positive cells after 48 h. A similar percentage (86%) of such double positive cells was also detected when DC were cultured with primary lung tumor cells. The uptake of tumor cells by DC was not dependent on irradiation, since live, non-irradiated cells were captured to the same degree (data not shown). When DC were matured with BCG and IFNγ for 24 h before adding irradiated A549 cells, the number of DC that captured A549 cells was lower than that of immature DC (Fig. 1B), demonstrating the reduced phagocytic capability of DC after maturation. The internalization of the irradiated tumor cells by DC was also confirmed by confocal microscopy. Figure 2 clearly shows the presence of green (PKH67)-colored A549 and primary lung tumor cell materials localized within the cytoplasm of CD11c+ (red) DC. Together, these data indicate that immature DC effectively capture irradiated lung tumor cells.

Fig. 1.

DC efficiently capture irradiated lung tumor cells. A A549 and primary lung tumor cells were labeled with PKH67, irradiated and mixed with an equal number of immature DC for varying lengths of time as indicated. The cells were subsequently stained with a PE-labeled anti-CD11c antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. B PKH67-labeled and irradiated A549 cells were cultured for 24 h with immature DC or DC matured with BCG and IFNγ. The cells were then stained with PE-labeled anti-CD11c antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. The cells shown were gated on CD11c+ populations. Values indicated in the upper right quadrant are the percent DC that captured tumor cells (CD11c+PKH67+)

Fig. 2.

Uptake of irradiated A549 and primary lung tumor cells by DC. Immature DC were loaded with PKH67-labeled, irradiated A549 or primary lung tumor cells for 24 h and then transferred to glass coverslips. Adherent DC were stained with Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated anti-CD11c (red) and the nuclear stain DAPI (blue). Samples were analyzed with a widefield epifluorescent/brightfield microscope. A A549 cell material internalized by DC; B primary lung tumor cell material internalized by DC; C A549 cell alone; D DC alone. (mid-plane images)

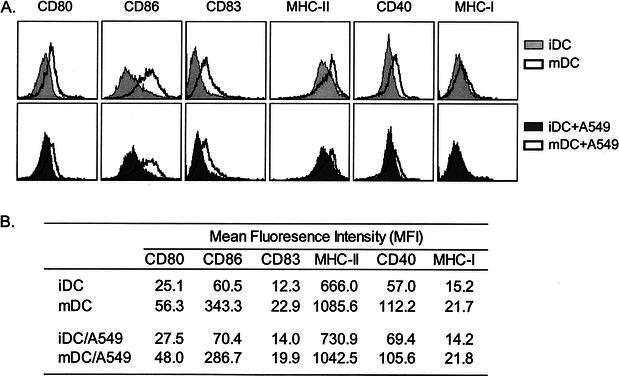

Uptake of irradiated lung tumor cells does not affect DC maturation

It is well documented that maturation of DC enhances their capacity to present antigens to T cells. To determine whether the uptake of irradiated lung tumor cells induces the maturation of DC or affects the ability of DC to become mature, we evaluated the expression of several surface molecules, including MHC class I and II, CD40, CD80, CD83 and CD86, as well as the production of cytokines by DC after tumor cell loading. To mature DC, we used a combination of killed mycobacteria (BCG) and an inflammatory cytokine (IFNγ), both of which have been shown to induce DC maturation [17, 40, 45, 46]. As shown in Fig. 3, without the addition of external maturation factors, DC possessed an immature phenotype, with low expression of CD83, moderate expression of CD40, CD80, CD86, MHC class I, and high expression of MHC class II. Uptake of irradiated A549 cells did not alter this phenotype, as the levels of these surface molecules were similar to those of unloaded DC. After maturation with BCG and IFNγ, the expression of all above surface molecules increased, as manifested by increases in both percent positive cells and the mean fluorescence intensities for these molecules. Importantly, DC exposed to maturation factors after A549 cell loading up-regulated expression levels of the above cell surface molecules in a manner similar to that of unloaded mature DC. These results indicate that uptake of irradiated lung tumor cells in itself does not induce DC maturation, nor affect the ability of DC to become mature in response to external stimuli.

Fig. 3.

Cell surface phenotype of A549-loaded immature and mature DC. Immature DC were mixed with or without irradiated A549 cells for 24 h and then untreated or matured with BCG and IFNγ for an additional 24 h. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of the indicated surface markers. A Histograms of various surface markers expressed by immature and mature DC with or without loading of A549 cells. B The corresponding mean fluorescence intensities of each surface marker. A representative experiment of three is shown

Mature DC loaded with irradiated lung tumor cells produce a high level of IL-12

We next determined the levels of cytokines IL-12 and IL-10 produced by DC after maturation with BCG and IFNγ and compared those to the levels produced by DC matured after the uptake of A549 cells. Before maturation, immature DC, with or without loading of tumor cells, showed a very low level of IL-12 and no detectable IL-10 production (Fig. 4). Treatment of DC with BCG and IFNγ strongly induced the production of the bioactive IL-12(p70). Similar high levels of IL-12 were also detected in supernatants from DC matured after the uptake of A549 lung tumor cells. This indicated that the capability of DC to produce IL-12 upon maturation by BCG and IFNγ was not impaired by the uptake of irradiated A549 lung tumor cells. The treatment with BCG and IFNγ did not induce significant increases in IL-10 production by DC.

Fig. 4.

Mature DC loaded with irradiated A549 cells produce high level of IL-12. Immature DC were loaded with or without irradiated A549 cells for 24 h, then matured with BCG and IFNγ for an additional 24 h. Supernatants collected at the end of the culture period were tested for IL-12 and IL-10 by ELISA. Bars represent the mean ± SD of triplicate wells. A representative experiment of three is shown. The amounts of IL-12 from mature DC in the presence or absence of A549 are significantly different ( P <0.001, Student's t -test) from those of IL-12 produced by immature DC. No significant difference was detected for IL-10 produced by immature or mature DC ( P >0.05, Student's t -test)

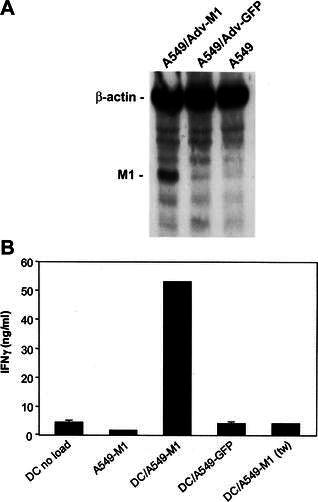

DC loaded with irradiated lung tumor cells induce antigen-specific IFNγ production

DC-based cancer vaccine using whole tumor cells as the source of tumor antigen is based on the ability of DC to process and present antigenic epitopes derived from ingested tumor cells to elicit antigen-specific immune responses. We first determined the ability of lung tumor cell-loaded DC to induce antigen-specific IFNγ secretion from T cells. Since well-defined tumor-specific antigens for lung cancer cells are lacking, we modified A549 cells to express the influenza M1 protein as a surrogate tumor antigen. Expression of the M1 protein by the modified A549-M1 cells was confirmed by western blot analysis (Fig. 5A). When DC loaded with an equivalent number of irradiated A549-M1 cells were used to stimulate autologous M1 peptide-specific T cells, a high level of IFNγ release from the T cells was detected (Fig. 5B). The specificity of the T cell response to A549-M1-loaded DC was confirmed by the lack of induction of IFNγ release from T cells stimulated with A549-M1 tumor cells alone, unloaded DC or DC loaded with A549 cells transduced to express GFP. To exclude the possibility that DC acquired T cell stimulatory activity from capturing the M1 proteins that may be released or leaked into the culture medium from A549-M1 tumor cells, we also cultured DC with A549-M1 cells in a transwell equipped with a porous membrane to allow diffusion of free proteins but not of whole cells. As expected, DC separated from the irradiated A549-M1 cells in the transwell did not activate specific T cells to release IFNγ, indicating that physical contact between DC and tumor cells was necessary for antigen acquisition and presentation. Taken together, these findings strengthened our assertion that stimulatory activity of DC was due to processing and presentation of antigenic epitopes derived from M1 protein integral to the modified tumor cells.

Fig. 5.

DC loaded with irradiated A549-M1 tumor cells stimulate IFNγ release by antigen-specific T cells. A Western blot analysis of M1 protein expression by A549-M1 cells. Lysates from equivalent number of control A549 cells and A549 cells infected with an adenovirus expressing influenza M1 protein (Adv-M1) or green fluorescent protein (Adv-GFP) were electrophoresed on a 12% SDS-PAGE, blotted onto an Immobilon-P PVDF membrane and hybridized with anti-influenza-matrix-HRP and anti-human β-actin antibodies simultaneously. The M1 and β-actin proteins on the membrane were visualized with the LumiGLO Chemiluminescent Substrate followed by exposure of the membrane to Kodak BioMax Light film. B Immature DC were loaded with or without an equal number of A549-M1 or A549-GFP tumor cells for 24 h. The cells were then matured with BCG and IFNγ and cultured with an equal number of cells from a M1-peptide-specific T cell line. After 24 h, supernatants were collected and analyzed for IFNγ release by ELISA. Cultures in which DC were separated from tumor cells by a 0.4-mm transwell membrane during the loading period are indicated by the notation ( tw). Bars represent the mean ± SD of triplicate wells. The results are representatives of four ( A) and three ( B) experiments

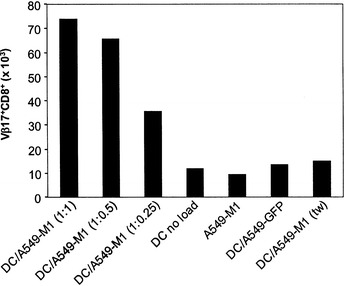

DC loaded with irradiated lung tumor cells induce the expansion of the antigen-specific CD8+ T cells

It has been shown that the T cell response to M1 protein-derived peptide (M58-66) is dominated by CD8+ T cells bearing TCR Vβ17 in HLA-A0201 individuals [25]. Thus, we evaluated the ability of the A549-M1-loaded DC to induce the expansion of the M1 peptide-specific Vβ17+CD8+ T cell population. In this study, we loaded a fixed number of immature DC with decreasing numbers of irradiated A549-M1 cells to yield a series of DC:tumor cell ratios of 1:1, 1:0.5 and 1:0.25. After maturation with BCG and IFNγ, the A549-M1-loaded DC were incubated with autologous, MHC class II+ cell-depleted PBMC. After 8–10 days, the number of Vβ17+CD8+ double positive T cells increased markedly in the cultures with DC loaded with irradiated A549-M1 cells (Fig. 6). The greatest expansion of Vβ17+CD8+ T cells was achieved when PBMC were stimulated with DC loaded with an equivalent number of A549-M1 cells (DC:tumor cell ratio of 1:1) and the number decreased when fewer tumor cells were used to load DC. Stimulation of the PBMC with DC or A549-M1 cells alone, or with DC loaded with A549-GFP cells did not result in the expansion of Vβ17+CD8+ T cells, confirming the specificity of the M1-restricted Vβ17+CD8+ T cell expansion by A549-M1-loaded DC. Again, DC separated from the M1-549 cells by a transwell membrane during loading did not induce the Vβ17+CD8+ T cell expansion.

Fig. 6.

DC loaded with irradiated A549-M1 tumor cells induce the expansion of the antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Immature DC were mixed with A549-M1 tumor cells at different DC:tumor cell ratios as indicated or control A549-GFP cells at a ratio of 1:1 and incubated for 24 h. The cells were then matured with BCG and IFNγ and cultured with MHC II-depleted autologous PBMC (84% CD3+) at a DC:PBMC ratio of 1:10 in the presence of IL-2 (20 U/ml) and IL-15 (5 ng/ml). One week later, the cells were counted, stained with a FITC-labeled anti-Vβ17 and PE-labeled anti-CD8 antibodies and analyzed by FACS. The absolute number of Vβ17+CD8+ cells was determined by multiplying the percent Vβ17+CD8+ cells identified by FACS with the total number of cells counted. A representative experiment of three is shown. ( tw transwell)

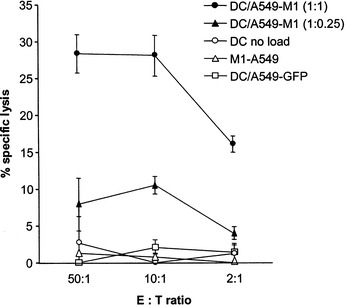

DC loaded with irradiated lung tumor cells induce the generation of antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells

Next, we investigated whether the expanded Vβ17+CD8+ T cells possessed cytolytic activity against the target cells displaying the M1 peptide. To test this, we collected the cells from above Vβ17+CD8+ T-cell expansion cultures with the highest and the lowest DC:tumor cell ratios (1:1 and 1:0.25, respectively) and tested them for their ability to lyse M1 peptide-pulsed T2 target cells in a standard 4-h 51Cr-release assay. As shown in Fig. 7, T cells generated from cultures containing A549-M1-loaded DC specifically killed M1 peptide-pulsed T2 target cells. In accordance with the observations from the expansion of Vβ17+CD8+ T cells, DC loaded with the A549-M1 cells at a ratio of 1:1 demonstrated higher levels of CTL activity than those loaded with fewer tumor cells (DC:tumor ratio of 1:0.25). No cytolytic activity against M1 peptide-pulsed targets was detected from T cells cultured with DC alone, A549-M1 tumor cells alone or DC loaded with A549-GFP cells. In addition, T cells stimulated with A549-M1-loaded DC did not lyse T2 targets pulsed with an irrelevant melanoma MART-1 peptide (not shown). Together, these results demonstrate that DC loaded with irradiated A549 lung tumor cells effectively acquired and presented antigen from the tumor cells and stimulated the expansion of antigen-specific T cells with CTL effector function.

Fig. 7.

DC loaded with irradiated A549-M1 tumor cells induce the generation of the antigen-specific CTL. Effector T cells from expansion cultures described in Fig. 6 were collected and mixed with M1-peptide pulsed, 51Cr-labeled T2 target cells at the effector:target (E:T) ratios indicated. The CTL activity was determined by a standard 4-h 51Cr-release assay. Points represent the mean ± SD of triplicate wells. The results are representatives of two experiments

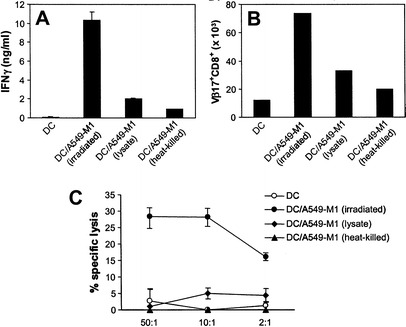

DC loaded with irradiated tumor cells are more efficient in induction of antigen-specific T cell responses than DC loaded with cell lysate or heat-killed cells

Several studies have shown that other forms of tumor cells including necrotic or killed tumor cells and tumor cell lysates are also potential sources of tumor antigens for the development of DC-based cancer vaccines. Thus, we compared the immunostimulatory capacity of DC loaded with irradiated tumor cells with that of DC loaded with equivalent amounts of a necrotic preparation of A549-M1 (cell lysate) or heat-killed cells. As shown in Fig. 8, DC loaded with irradiated tumor cells were most effective in stimulating IFNγ release from M1-specific T cells when compared to those loaded with tumor cell lysate or heat-killed tumor cells (Fig. 8A). Similarly, the greatest expansion of the M1 peptide-specific Vβ17+CD8+ T cells from PBMC was achieved using DC loaded with irradiated tumor cells (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, only DC loaded with irradiated tumor cells elicited T cells with measurable lytic activity against M1-peptide-bearing targets (Fig. 8C). Together, these results clearly demonstrate that irradiated lung tumor cells as a source of tumor antigen for DC loading is superior to tumor cell lysate or heat-killed tumor cells in efficient induction of antigen-specific T cell responses and thus represents the best choice for the development of DC-based vaccine for lung cancer.

Fig. 8.

DC loaded with irradiated A549-M1 tumor cells are more efficient in induction of antigen-specific T cell responses. DC loaded with irradiated or heat-killed A549-M1 cells or with A549-M1 lysate were compared for their ability to induce ( A) release of IFN from M1 peptide-specific T-cell line, ( B) expansion of antigen-specific V17+CD8+ cells from PBMC and ( C) generation of antigen-specific CTL

Discussion

Immunotherapy of cancer using DC-based vaccine relies on the capability of DC to acquire and present tumor antigens in order to elicit antitumor immune responses. Such capability of DC was recently demonstrated for a variety of tumor types [3, 12, 14, 18, 19, 22, 29, 33, 35, 44]. However, no such study has been reported for lung cancer. One impediment for such a study lies in the lack of defined tumor antigen from lung cancer cells for the evaluation of antigen-specific immune responses. Here, we describe an in vitro system to assess the capacity of DC to acquire and present antigen from lung cancer cells. We show that monocyte-derived DC are capable of capturing irradiated lung tumor cells. Using modified lung tumor cells expressing influenza M1 protein, we were able to demonstrate the efficiency of DC in acquiring and presenting a defined tumor-derived antigen capable of generating measurable immune responses that include: (1) IFNγ release from an M1-specific T cell line, (2) expansion of M1 peptide-specific T cells in PBMC, as characterized by TCR Vβ17 and CD8 expression and (3) generation of antigen-specific CTL.

IL-12 has been shown to play an important role in stimulating IFNγ production from activated T cells [6, 15, 26, 39], and thus, induces the development of type 1 (Th1) immune response characteristic of CTL activation. In contrast, IL-10 primarily directs a type 2 response through the activation of Th2 cells and ultimately can suppress the development of CTL [30]. It has become increasingly clear that successful induction of effective antitumor immunity is dependent on the generation of a Th1 type immune response that activates IFNγ production and tumor-specific CTL, the cells directly responsible for killing tumor cells in vivo [8, 9, 11, 20, 47, 49]. Thus, the ability of DC to produce IL-12 upon maturation may, to a large extent, determine the success of a DC vaccine in eliciting antitumor immunity. Our results showed that maturation of the A549-loaded DC with BCG and IFNγ strongly induced IL-12, but not IL-10, production from these cells. When co-cultured with T cells, the BCG/IFNγ-matured, A549-loaded DC were able to induce antigen-specific T cell activation, resulting in both high level production of IFNγ from the T cells and the generation of CTL. Together, our results demonstrate the capability of lung cancer cell-loaded DC to initiate a Th1 response specific to the antigen derived from the lung cancer cells and an effective method to generate mature DC that produce cytokines important to the development of effective antitumor immunity.

In our study, loading of immature DC with A549 lung cancer cells did not induce the maturation of DC, as no up-regulation of costimulatory molecules or maturation-associated markers nor the production of IL-12 was detected. Such lack of maturation of DC after ingesting the irradiated tumor cells is not uncommon. It has been observed that loading of DC with irradiated apoptotic cells from melanoma, kidney adenocarcinoma, EBV-transformed B lymphocytes or normal fibroblasts did not induce DC maturation [13, 21, 32, 37]. To date, only certain necrotic tumor cells or tumor cell lysate have been reported to be able to induce DC maturation after being ingested by DC [13, 32, 37, 38]. Therefore, to develop potent T cell stimulatory capacity, DC that have phagocytosed irradiated lung tumor cells must be matured with external maturation stimuli. We show that, although DC loaded with irradiated A549 cells do not undergo the process of maturation, these cells are fully capable of responding to the BCG/IFNγ-induced maturation.

In addition to irradiated tumor cells, several other forms of tumor cells such as necrotic or killed tumor cells and tumor cell lysates have also been used as sources of tumor antigens for DC loading [48]. While all these forms of tumor cells have been shown to be immunogenic, they are not equally efficient in promoting antitumor immune responses for a given tumor type or in a given experiment system. Some studies showed that DC loaded with apoptotic or non-replicating live tumor cells were more efficient than those loaded with tumor cell lysates or killed tumor cells in induction of tumor-specific CTL and antitumor immunity [16, 34, 43], whereas others demonstrated that necrotic cells or cell lysate, but not apoptotic cells, are essential for priming antitumor immune responses [37]. In our study, irradiated lung tumor cells proved to be a more immunogenic source of antigen than either equivalent cell lysate or heat-killed cells. The reason why the irradiated tumor cells are more immunogenic in this and other studies is still not clear. It has been reported that freeze-thaw tumor cell lysates can inhibit the CTL activity in vitro [43]. It is also possible that the type of lung tumor cells used in this study accounts for the better immunogenicity observed with irradiated tumor cells.

Recently, the method of loading DC with antigens derived from whole tumors or cell components became an attractive strategy for the development of DC-based cancer vaccines [48]. However, unlike the DC vaccines loaded with defined antigens for which the antigen-specific immune responses are readily measurable, it is difficult to assess the immune responses induced by DC loaded with whole tumor cell antigens from the tumor types with no defined tumor antigens, especially when the HLA-matched or autologous materials are difficult to obtain. In these instances, the use of a well-defined surrogate antigen as a marker is helpful, as it provides a measurement for monitoring the efficiency of DC in acquiring and presenting tumor-derived antigens and in inducing antigen-specific immune responses. In addition, it also provides a useful system to analyze and optimize the experimental parameters for each component of DC vaccines in vitro, since this process cannot be done in controlled clinical trials. Finally, we believe that the system described in this study is not limited to lung cancer and can be used in general for other tumor types with no defined tumor antigens available to assess the function of DC and the immune responses induced by DC.

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael D. Roth and Sylvia M. Kiertscher and their colleagues at the UCLA School of Medicine for development of the lung tumor cell isolation procedure and for provision of primary NSCLC tissue. We also thank Robert Bader for his assistance with cytokine assays.

Footnotes

Y. Zhou and J.A. McEarchern contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Albert Nature. 1998;392:86. doi: 10.1038/32183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Moundhri Br J Cancer. 1998;78:282. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banchereau Cancer Res. 2001;61:6451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellone J Immunol. 1997;159:5391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Celluzzi J Immunol. 1998;160:3081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan J Exp Med. 1991;173:869. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang Anticancer Res. 2000;20:1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Int J Cancer. 2001;93:539. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dredge J Immunol. 2002;168:4914. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.4914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreira Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;41:57. doi: 10.1016/S1040-8428(01)00197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fong J Immunol. 2001;167:7150. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.7150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fong Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:245. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallucci Nat Med. 1999;5:1249. doi: 10.1038/15200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geiger Lancet. 2000;356:1163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02762-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heufler Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:659. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann Cancer Res. 2000;60:3542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmann J Immunother. 2001;24:162. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200103000-00011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holtl J Urol. 1999;161:777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu Nat Med. 1996;2:52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inagawa Anticancer Res. 1998;18:3957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenne Cancer Res. 2000;60:4446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kugler Nat Med. 2000;6:332. doi: 10.1038/73193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurokawa Int J Cancer. 2001;91:749. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200002)9999:9999<::aid-ijc1141>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambert J Immunother. 2001;24:232. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200105000-00006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehner J Exp Med. 1995;181:79. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macatonia J Immunol. 1995;154:5071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morrison Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:903. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy Prostate. 1999;39:54. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(19990401)39:1<54::AID-PROS9>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nestle Nat Med. 1998;4:328. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ouyang Immunity. 1998;9:745. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80671-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paczesny Cancer Res. 2001;61:2386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pietra Cancer Res. 2001;61:8218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reichardt Blood. 1999;93:2411. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ronchetti J Immunol. 1999;163:130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salgaller Cancer. 1999;86:2674. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19991215)86:12<2674::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook a laboratory manual. 1989;3:18. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sauter J Exp Med. 2000;191:423. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnurr Cancer Res. 2001;61:6445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seder Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10188. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith Immunol Lett. 2001;76:79. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2478(00)00324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Son Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1472. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200108000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spisek Cancer Res. 2002;62:2861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strome Cancer Res. 2002;62:1884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thurner J Exp Med. 1999;190:1669. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thurnher Int J Cancer. 1997;70:128. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970106)70:1<128::AID-IJC19>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsuji Infect Immun. 2000;68:6883. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.12.6883-6890.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:450. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.4.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou J Immunother. 2002;25:289. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200207000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zitvogel J Exp Med. 1996;183:87. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]