Abstract

The search for alternative strategies of therapy remains a major issue for most neoplastic diseases. The expression of several tumor antigens makes human rhabdomyosarcomas, which are the most frequent form of soft tissue tumor in children, a good candidate for tumor-specific immunotherapy. To assess the feasibility of this approach, we evaluated the ability of rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines to process and present the MAGE-A tumor antigens to effectors of the immune system. To this end, we investigated recognition of MAGE-A–positive rhabdomyosarcoma cells by HLA-B*3701-restricted T cells specific for a MAGE-A–derived peptide. Low level of HLA expression impaired recognition of the tumor cells. Therefore, to obtain HLA expression avoiding the use of IFN-γ and TNF-α, which could affect the proteasome activity, a rhabdomyosarcoma line was transduced by a retroviral vector encoding the HLA-B*3701 allele. Recognition of the infected cells was then observed also in the absence of IFN-γ and TNF-α treatment, thus demonstrating that rhabdomyosarcoma cells were indeed able to naturally process and present the MAGE-A antigens. These results demonstrate that rhabdomyosarcoma cells expressing MAGE-A can be targets of tumor-specific effectors, suggesting the feasibility of clinical protocols of specific immunotherapy also for the treatment of rhabdomyosarcoma.

Keywords: Rhabdomyosarcoma, Immunotherapy, MAGE, Tumor antigens

Introduction

Rhabdomyosarcoma is the commonest, highly malignant soft tissue tumor in childhood [1]. Pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma can be classified in two major subtypes, embryonal and alveolar, which have distinct clinical behaviors. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas usually are more aggressive than the embryonal variants. The unfavorable prognosis is related to the propensity of this subtype for early and wide dissemination and to a poor response to chemotherapy [1].

The chance to cure patients with metastatic and recurrent rhabdomyosarcomas is indeed very poor: surgical resections are often difficult, and in many advanced stages of the disease, tumor relapses become resistant to most chemo and radiotherapy treatments [2].

In this context, investigations for new and alternative strategies of tumor therapies are crucial. Up to now, only a small number of immunotherapy protocols have been reported, and without any significant clinical response [3, 4]. Indeed, the development of highly specific and controlled experimental trials has been hampered by the lack of information available on the antigenic and immunological properties of rhabdomyosarcomas.

Recently, expression of the tumor-specific antigens MAGE, GAGE, and BAGE has been shown in rhabdomyosarcoma [5]. These antigens are particularly relevant from a clinical point of view, because of their broad tumor-specific expression in cancers, which has allowed the development of several clinical trials of peptide vaccination in melanoma patients [6].

Presentation of MAGE-, GAGE-, and BAGE-derived peptides in association with HLA class I and II molecules to CD8+ or CD4+ T lymphocytes has been documented for melanomas [7, 8] and tumor cells of several histotypes [9, 10]. However, no data have been reported so far concerning the ability of rhabdomyosarcoma cells to efficiently present these TAAs to T-cell effectors.

In this study we analyzed whether rhabdomyosarcoma cells expressing MAGE-A tumor antigens are indeed able to process and present MAGE-A–derived epitopes to immune effectors. The results obtained suggest the feasibility of clinical protocols of specific immunotherapy also for the treatment of rhabdomyosarcoma.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

CCA, RD/18, and RC2 rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines were established in Dr Lollini’s laboratory. RH-30 cells were a kind gift from Dr A. Rosolen (University of Padua, Italy) and Dr D.N. Shapiro (St Jude Children’s Hospital, Memphis, TN). The MSR3-B37 and MSR3-B52 melanoma lines, expressing HLA-B37 and HLA-B52, respectively, and the lymphoblastoid B cell line MSR3-EBV were established in our laboratory [11]. C1R was purchased from the ATCC (Rockville, MD) and transduced to express either HLA-B37 (C1R-B37) or HLA-B52 (C1R-B52).

Neoplastic cell lines were grown in complete IMDM supplemented with 10% FCS, glutamine, and antibiotics. The HLA molecular typing of the rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines was performed by the SSOP method as described elsewhere [12].

RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted using RNAzolTMB (Biotecx, Houston, TX) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Single-stranded cDNA synthesis was carried out on 2 μg of total RNA with oligo-dT and Moloney leukemia virus–derived reverse transcriptase. At the end of the reaction, cDNA was resuspended in 100 μl of water. Fifty microliters of reaction mixture containing 5 μl of cDNA, 4 μl of a 10-mM dNTPs mixture, 5 μl of 10X DNA polymerase buffer (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland), 2 U of Dynazyme polymerase (Finnzymes), and sense and antisense oligonucleotide primers (for oligonucleotide-primer sequence and concentration and for gene-specific PCR amplification programs, see Dalerba et al. [5]). PCR amplification products were size fractionated on a 1.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized on a UV transilluminator. Samples scored positive when a band of the appropriate size was visible on the gel.

Cytotoxicity and cytokine release assays

Lytic activity of the TCL 337 was tested in a chromium release assay as described previously [13].

To evaluate IFN-γ release, 8×103 responders were incubated for 24 h with 4×104 target cells in the presence of 50 U/ml IL-2. Where indicated, targets were pretreated for 72 h with 10 ng/ml TNF-α and 20 U/ml IFN-γ, and/or pulsed with 10-µM peptide for 2 h at room temperature and washed in medium before plating. IFN-γ released in 100 μl of supernatant was measured using an IFN-γ release kit (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Immunofluorescence analysis

Expression of cell surface molecules was analyzed by labeling 0.2×106 to 0.4×106 cells with the relevant mAbs under standard conditions. A secondary, FITC-labeled goat antimouse IgG mAb (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) was used to visualize binding of unlabeled mAbs. FACS analysis of fluorescence was conducted according to standard methods.

Retroviral vector-mediated gene transfer of HLA-B*3701 into rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines

The retroviral vector B37-CSM, coding for the HLA-B*3701 molecule, was constructed as previously described [11]. It encodes the HLA-B*3701 molecule, under the control of the viral LTR, and the truncated form of the human low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor (LNGFR), which was driven by the Sv40 promoter.

Transduction of rhabdomyosarcoma cells was performed by cultivation with retrovirus-containing supernatant in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/ml). Three or four rounds of infection of at least 4 h were performed. Efficiency of infection was evaluated by immunofluorescence analysis with the LNGFR-specific mAb 20.4 (ATCC, Rockville, MD). Pure populations of infected cells were immunoselected for LNGFR expression by magnetic beads (Dynabeads M-450; Dynal, Oslo, Norway) coated with the LNGFR-specific mAb 20.4.

Results

Analysis of MAGE-A expression in rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines

Expression of the T-cell–defined antigens MAGE-A1, MAGE-A2, MAGE-A3, and MAGE-A6 was analyzed by RT-PCR in rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines RD/18, RC2, RH30, and CCA. As reported in Table 1, none of the cell lines expresses MAGE-A1 mRNA, while MAGE-A2 and MAGE-A3 were detected in all of them, except CCA. MAGE-A6 was expressed only in RD/18 and RH30 cells. The RT-PCR analysis was in agreement with the results reported by Dalerba et al. [5].

Table 1.

Expression of MAGE-1 and MAGE-3 genes and HLA molecular typing of rhabdomyosarcoma lines

| Cell line | Origin | MAGE genea | HLA-Ab | HLA-Bb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A6 | ||||

| RD/18 | Embryonal | − | + | + | + | A*01/- | B*3701/- |

| CCA | Embryonal | − | − | − | − | A*02/- | B*1801/*35 |

| RC2 | Alveolar | − | + | + | − | A*01/- | B*3701/*1402 |

| RH30 | Alveolar | − | + | + | + | Neg. | Neg. |

aExpression was evaluated by RT-PCR analysis with specific primers

bMolecular typing was performed using the SSOPs system on genomic DNA

To evaluate whether rhabdomyosarcoma cells can be the target of antigen-specific T-cell effectors, we investigated the recognition of these cell lines by MAGE-A–specific effectors. We have previously described a HLA-B*3701–restricted cytotoxic T cell line, named TCL 337, isolated by stimulation of peripheral blood lymphocytes of a melanoma patient with autologous tumor cells expressing only the HLA-B37 allele. The target of TCL 337 is the peptide MAGE-A.127-136 (REPVTKAEML, hereafter referred to as M.127) endogenously processed from MAGE-A1, MAGE-A2, MAGE-A3, and MAGE-A6 products [11].

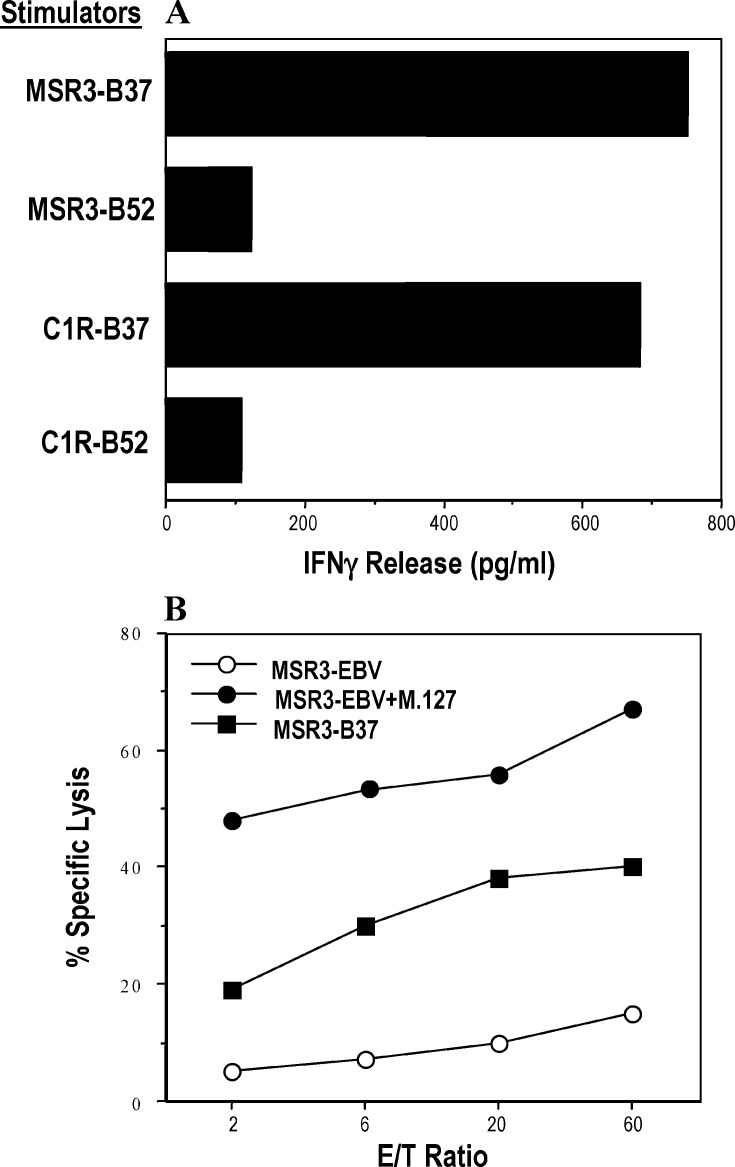

As shown in Fig. 1A, TCL 337 recognized the autologous melanoma cell line MSR3-B37 and the HLA-B*3701–transfected EBV cell line C1R that endogenously express MAGE-A3 (i.e., C1R-B37). Furthermore, TCL 337 lysed specifically autologous EBV cells (i.e., MSR3-EBV) upon incubation with the synthetic M.127 peptide (Fig. 1B) [11].

Fig. 1A, B.

Antigen specificity of TCL 337. A TCL 337 recognized the autologous tumor cell line MSR-B37 and the MAGE-A3+ EBV cell line C1R, previously transfected with cDNA encoding HLA-B*3701. Recognition of the target cells was evaluated as IFN-γ release after 24 h of incubation, as described in “Materials and methods.” B Target antigen of TCL 337 is the peptide M.127 presented by HLAB*3701. TCL 337 specifically lysed the autologous EBV cell line MSR3-EBV in the presence but not in the absence of 10 μM of M.127 peptide, which is encoded by MAGE-A1, MAGE-A2, MAGE-A3, and MAGE-A6 [11]. Lytic activity was evaluated in a classical cytotoxic assay at the indicated E/T ratio

Specific recognition of rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines by TCL 337

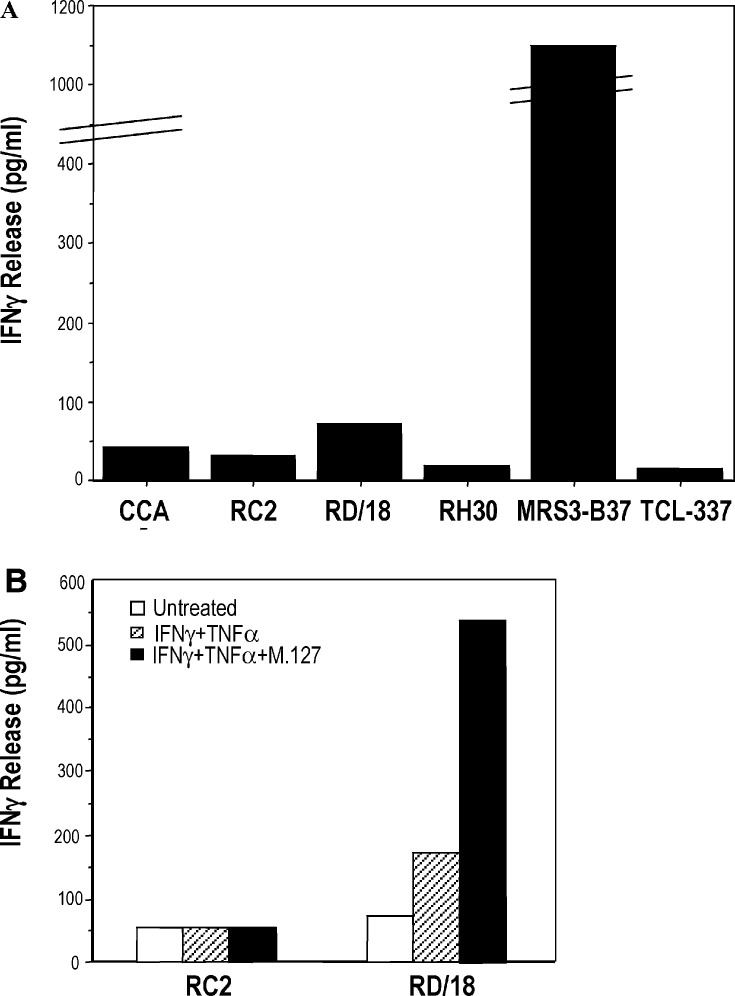

Recognition of the rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines (described in Table 1) by TCL 337 was evaluated in an IFN-γ release assay. As expected, the lines RH30 (HLA class I–negative) and CCA (HLA-B*3701–negative) were not recognized (Fig. 2A). In spite of HLA-B*3701 typing and MAGE-A2, MAGE-A3, and MAGE-A6 expression, the RC2 and RD/18 cells were not significantly recognized (Fig. 2A); only a barely detectable amount of IFN-γ was released in the presence of the rhabdomyosarcoma cell line RD/18.

Fig. 2A, B.

Recognition of several rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines by TCL 337. A As expected, the rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines RH30 and CCA that are HLA-B*3701–negative were not recognized. Surprisingly a nearly undetectable amount of IFN-γ was released by TCL 337, in the presence of the RC2 and RD/18 cell lines, molecularly characterized as HLA-B*3701 and MAGE-A2, MAGE-A3–positive. B Upon treatment of the RC2 and RD/18 cell lines with IFN-γ and TNF-α, a slight recognition of the RD/18 cells was observed. This recognition was further increased in the presence of peptide M.127. Neither the cytokine treatment nor the peptide pulsing restored recognition of RC2 cells

To investigate whether the absence of recognition of the RC2 and RD/18 cell lines by TCL 337 was due to their inability to process and present the MAGE-A–derived epitope on the cell surface, or to the loss of MHC class I expression, the cells were incubated with IFN-γ and TNF-α, pulsed with peptide M.127 and used as stimulators in an IFN-γ release assay. As shown in Fig. 2B, the cytokine-treated RC2 line was not recognized even when it was pulsed with the exogenous peptide M.127, suggesting that the absence of recognition was due to the lack of HLA-B*3701 expression, rather than to the inability of the cells to process and present the target peptide on the cell surface. On the contrary, an increase of IFN-γ release was detected in the presence of cytokine-treated RD/18 cells (Fig. 2B). The release was further improved when the cells were pulsed with the exogenous peptide M.127 (Fig. 2B), indicating that treatment with IFN-γ plus TNF-α partially restores HLA-B*3701 expression, as confirmed by the immunofluorescence analysis reported in Table 2, and allows presentation of the MAGE-A epitope by RD/18 cells.

Table 2.

Cell surface expression of HLA molecules on rhabdomyosarcoma lines. ND not done

| Cell line | Cytokine treatmenta | MFIb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-B, HLA-C | HLA-Bw4 | ||

| RD/18 | - | 36.3 | 6 |

| RD/18 | + | 501 | 95.4 |

| RC2 | - | 31.3 | 1 |

| RC2 | + | ND | ND |

| RD/18LB37c | - | 265.4 | 76.7 |

aCells were treated with TNF-α and IFN-γ, as described in “Materials and methods”

b MFI indicates “mean fluorescence value” as detected by FACS analysis. Surface expression of HLA molecules was evaluated by indirect fluorescence staining using the mAb 4E or 116–52, recognizing HLA-B, HLA-C and HLA-Bw4, respectively

cRD/18LB37 cells were obtained by transduction of RD/18 cells with the retroviral vector B37-CSM encoding HLA-B*3701

It has been previously reported that treatment with IFN-γ up-regulates three proteasome subunits—LMP-2, LMP-7, and MECL—giving rise to what is commonly referred to as the “immunoproteasome,” in contrast to the 20S “housekeeping” proteasome. These new proteasome subunits are able to replace the catalytic subunits and modify the range of peptides or simply increase and accelerate the generation of the same set of peptides [14].

To verify whether rhabdomyosarcoma cells are able to process and present the target peptide independently of IFN-γ treatment, RD/18 cells were infected with the B37-CSM retroviral vector encoding the HLA-B*3701 molecule and a truncated form of the low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor (LNGFr), as marker gene. We chose to transduce the RD/18 line because of both its higher rate of proliferation compared with RC2, and the presence in the RD/18 cells of a fully functional processing machinery, as indicated by the experiments showed in Fig. 2.

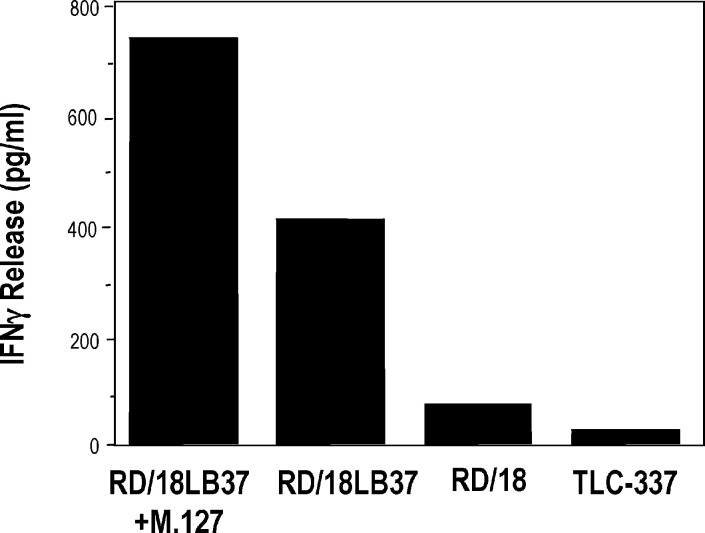

A pure population of RD/18-transduced cells (i.e., RD/18LB37) expressing HLA-Bw4 (Table 2) was obtained by cell sorting as described in “Materials and methods.” The RD/18LB37 cells were then used as stimulators in an IFN-γ release assay. As shown in Fig. 3, the rhabdomyosarcoma line RD/18LB37 was recognized by TCL 337 even in the absence of exogenous M.127 peptide. These results demonstrate that rhabdomyosarcoma cells not only express MAGE-A mRNAs but are also able to process and present the tumor-specific antigens to T-cell effectors of the immune system.

Fig. 3.

Recognition of the RD/18LB37 cells by TCL 337. The transduced RD/18LB37 cells induced IFN-γ release by the TLC 337. This recognition is only slightly increased by the addition of 10 μM of M.127 peptide

Discussion

MAGE genes, belonging to the cancer-testis family of TAAs, have a pattern of expression particularly relevant from a clinical point of view. Indeed, protocols of tumor-specific immunotherapy using peptides derived from MAGE-A1 and MAGE-A3 are currently ongoing in patients affected by melanomas, with encouraging results [6]. The expression of MAGE-A genes has been extensively studied in adult neoplasia [15, 16, 17], and in some pediatric tumors. Their expression has been frequently detected in patients affected by neuroblastoma [18,19] and high-grade brain tumors, like medulloblastoma, glioblastoma multiforme, and ependymoma [20].

Recently, the expression of MAGE-A gene has been demonstrated also in a significant proportion of pediatric patients affected by rhabdomyosarcoma (MAGE-A1, 38%; MAGE-A2, 51%; MAGE-A3, 35%; MAGE-A4, 22%; MAGE-A6, 35%) [5]. However, no data were available on the ability of rhabdomyosarcoma cells to present TAA-derived epitopes to effector T cells. Indeed, detection of either the mRNAs encoding TAAs or their derived protein products does not assure that these proteins are indeed correctly processed by rhabdomyosarcoma cells, to generate antigenic peptides.

In this paper we demonstrate that rhabdomyosarcoma cells not only express several members of the MAGE-A gene family, but they are also able to process the encoded proteins and to present the derived antigenic peptides to T-cell effectors of the immune system. Indeed, a rhabdomyosarcoma line (i.e., RD/18) expressing MAGE-A2, MAGE-A3, and MAGE-A6 was recognized by a HLA-B*3701–restricted T cell line, specific for those antigens. Upon treatment with IFN-γ and TNF-α or the infection with a retroviral vector encoding the HLA-B*3701 molecule, RD/18 cells were recognized with higher efficiency, suggesting that recognition of rhabdomyosarcoma cells by T-cell effectors could be impaired by down-regulation of MHC class I gene expression.

The loss or down-regulation of HLA class I molecules is a very common event during malignant transformation. Many tumors escape T-cell recognition by the loss of MHC class I gene expression [21]. The molecular mechanisms responsible for this phenotype involve genomic loss [22], attenuation of class I transcription [23, 24] or hypermethylation of HLA promoters [25].

In particular, rhabdomyosarcomas may display either a complete loss or an increased expression of HLA molecules compared with the normal counterpart. These modifications seem to be associated with malignant transformation of striated muscle tissue and with the degree of cellular differentiation [26].

The loss or down-regulation of HLA class I molecules could be a great obstacle for the development of tumor-specific immunotherapy trials. However, type I interferon receptors have been detected in fresh rhabdomyosarcoma specimens, and there are clear indications that HLA class I expression can be restored by in vitro treatment with IFN-γ and TNF-α in rhabdomyosarcoma (see Table 2) as well as in other tumor histotypes [9]. It remains to establish whether the same results could be also achieved in vivo through the systemic administration of appropriate cytokines.

In pediatric tumors immunotherapy has been rarely attempted. However, it has been recently demonstrated that vaccination with autologous tumor lysate–pulsed dendritic cells in children is feasible, nontoxic, and able to elicit specific T-cell responses and to induce metastases regression [27].

Our data suggest that similar approaches of active immunotherapy directed against defined tumor antigens (e.g., MAGE-A3) could be exploited also for the treatment of rhabdomyosarcoma patients.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC).

References

- 1.Barr J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997;19:183. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199711000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pappo J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2123. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.8.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koscielniak Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:227. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moritake Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21:725. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalerba Int J Cancer. 2001;93:85. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchand Int J Cancer. 1999;80:219. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990118)80:2<219::aid-ijc10>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Science. 1991;254:1643. doi: 10.1126/science.1840703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boël Immunity. 1995;2:167. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Traversari Gene Ther. 1997;4:1029. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleischhauer J Immunol. 1997;159:2513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanzarella Cancer Res. 1999;59:2668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennedy LJ, Poulton KV, Thimson W, Williams F, Middleton D, Howell WM, Tarassi K, Papasteriades C, Albert E, Fleischhauer K, Chandanayingyong D, Tiercy JM, Juji T, Tokunaga K, Ollier WER (1997) HLA class I DNA typing using sequence specific oligonucleotide probes (SSOP). In: Charron D (ed) HLA genetic diversity of hla functional and medical implication, vol 1. EDK Medical and Scientific, Paris, p 216

- 13.Fleischhauer Cancer Res. 1998;58:2969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fruh Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:76. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patard Int J Cancer. 1995;64:60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910640112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russo Int J Cancer. 1995;64:1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russo Int J Cancer. 1996;67:457. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960729)67:3<457::AID-IJC24>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishida Int J Cancer. 1996;69:375. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961021)69:5<375::AID-IJC4>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corrias Int J Cancer. 1996;69:403. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961021)69:5<403::AID-IJC9>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scarcella Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrido Immunol Today. 1997;18:89. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(96)10075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramal Hum Immunol. 2000;61:1001. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(00)00171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrido Adv Cancer Res. 1995;67:155. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60713-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koopman J Exp Med. 2000;191:961. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serrano Int J Cancer. 2001;94:243. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandez Immunobiology. 1991;182:440. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geiger Lancet. 2000;356:1163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02762-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rimoldi Int J Cancer. 2000;86:749. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000601)86:5<749::AID-IJC24>3.3.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]