Abstract

Purpose: Infection with oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV-16 in particular is a leading cause of anogenital neoplasia. High-grade intraepithelial lesions require treatment because of their potential to progress to invasive cancer. Numerous preclinical studies have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of E7-directed vaccination strategies in mice tumour models. In the present study, we tested the immunogenicity of a fusion protein (PD-E7) comprising a mutated HPV-16 E7 linked to the first 108 amino acids of Haemophilus influenzae protein D, formulated in the GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals adjuvant AS02B, in patients bearing oncogenic HPV-positive cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). Methods: Seven patients, five with a CIN3 and two with a CIN1, received three intramuscular injections of adjuvanted PD-E7 at 2-week intervals. Three additional CIN1 patients received a placebo. CIN3 patients underwent conization 8 weeks postvaccination. Cytokine flow cytometry and ELISA were used to monitor antigen-specific cellular and antibody responses from blood taken before and after vaccine or placebo injection. Results: Some patients had preexisting systemic IFN-γ CD4+ (1/10) and CD8+ (5/10) responses to PD-E7. Vaccination, not placebo injection, elicited systemic specific immune responses in the majority of the patients. Five vaccinated patients (71%) showed significantly increased IFN-γ CD8+ cell responses upon PD-E7 stimulation. Two responding patients generated long-term T-cell immunity toward the vaccine antigen and E7 as well as a weak H. influenzae protein D (PD)–directed CD4+ response. All the vaccinated patients, but not the placebo, made significant E7- and PD-specific IgG. Conclusions: The encouraging results obtained from this study performed on a limited number of subjects justify further analysis of the efficacy of the PD-E7/AS02B vaccine in CIN patients.

Keywords: CD4, CD8, Human papillomavirus, IFN-γ, Immunotherapy

Introduction

Persisting infection with oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) is a significant risk factor for the development of anogenital intraepithelial lesions that may progress to cancer [12]. DNA from these high-risk HPVs is detected in more than 99% of cervical cancers, 50% of anal, penile, vulvar and vaginal cancers, but also in more than 20% of oral, laryngeal and nasal cancers [38]. Although infection, even with high-risk HPV and low-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN1), are frequently cleared spontaneously [25], women who harbour oncogenic HPV are more likely to develop high-grade lesions (CIN2/3) than women who do not [18]. Currently, high-grade lesions (CIN2/3) detected by screening are treated because it is impossible to predict which CIN will progress to invasive tumours. However, conventional ablative physical or chemical therapeutic approaches are not optimal as they might lead both to recurrence and adverse events [26, 29, 31].

An HPV-directed vaccine capable of eradicating infected cells and protecting against new infections would represent a great medical benefit for patients. Much research is presently focused on setting up such vaccines and HPV-16–directed vaccine in particular because this viral type is the most frequently encountered HPV in CIN lesions and cancer [8, 21]. The main targets of immunotherapeutic strategies are the E6 and E7 viral oncoproteins, as they are expressed at all stages of the virus life cycle and particularly in cancer cells [24, 28]. These proteins have been reported to contain both MHC class I– and II–restricted epitopes recognized by human and mouse T cells [16, 35]. Numerous preclinical studies have demonstrated the ability of HPV-16 E7–based vaccinations to generate protective as well as therapeutic antitumour immunity, at least in some mice tumour models [4, 14, 21, 22].

These promising results have justified the evaluation of the safety and immunogenicity of some HPV-16/18 E6/E7–directed vaccines in patients bearing either anogenital cancer or high-grade intraepithelial lesions: recombinant vaccinia viruses, peptides or proteins mixed or not with adjuvant, dendritic cells pulsed with tumour lysate and plasmidic DNA encapsulated in microparticles [5, 8, 10, 17, 19, 27, 32, 34, 36]. The clinical efficacy of these treatments remains to be demonstrated.

In the present multicentre study, we investigated the immunogenicity of a HPV-16 E7 fusion protein (PD-E7) formulated in an adjuvant system containing MPL, QS-21 and oil-in-water emulsion (GSK AS02B) in patients with oncogenic HPV-positive CIN. Preclinical studies performed in C57BL6 mice have shown that this antigenic formulation induces regression of preestablished TC1 and C3 tumours [9]. The cellular immune response to vaccination was monitored from PBMCs briefly stimulated in vitro with antigenic proteins, using cytokine flow cytometry (CFC). Our data show that vaccination with PD-E7/GSKAS02B induces both cellular and humoral immune responses, characterized by a PD-E7–specific production of IFN-γ from CD8+ T cells and low titres of E7- and PD-specific IgG.

Materials and methods

Subjects

CIN1 and CIN3 patients were recruited from different centres (University Hospital of Liege and Erasme Hospital, respectively). The eligibility criteria for CIN1 patients were the persistence of a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion as diagnosed by cytological examination and biopsy-proven CIN1 for a minimum of 3 months with detection of oncogenic HPV (detected by Hybrid Capture II System, Digene, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). The eligibility criteria for CIN3 patients have been previously described [33]. Briefly, they had high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion as diagnosed by single-layer cytology and biopsy-proven CIN3. Colposcopy demonstrated exocervical lesions with less than 3-mm involvement of the endocervical canal. For CIN3 lesions, the PCR products obtained following DNA amplification with MY09/MY11 primers were typed HPV-16 by the DEIA method [3, 6, 30]. A total of eleven patients, ages 20–51, were enrolled after providing signed informed consent. One patient was withdrawn before the end of the study [33].

Vaccination protocol

Patients were injected intramuscularly in the buttock at 0, 2 and 4 weeks with 200 μg of an HPV-16 E7–derived fusion protein (PD-E7, C24G/E26Q mutated E7 protein fused at its amino-terminal end to the first 108 amino acids of Haemophilus influenzae protein D and tagged at its carboxy-terminal end with six histidines) formulated with 500 μl of the GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Adjuvant System AS02B (100-μg MPL, 100-μg QS-21 and 250-μl oil-in-water emulsion) [9]. Controls were injected with 500 μl of a NaCl 0.9% solution (placebo). The adjuvant known to induce local adverse reactions was not used as placebo because of ethical concerns. The vaccination protocol was single blind. The study vaccine has been kindly provided by GSK Biologicals, Belgium. Patients were followed up at the hospital 2 h after each vaccination for observation.

Specimen collection

Calparinated blood (25 ml) was obtained at each vaccination/placebo injection date, 4 weeks after the last injection (conization date for CIN3 patients) and at the end of the study (between weeks 35 and 60). An additional blood sample was obtained 2 years postvaccination for two CIN3 patients.

Clinical follow-up

Patients were clinically monitored at weeks 0, 2, 4, 8±1, 20±1, 32±3 and 44±6. Briefly, disease status was monitored at each visit using colposcopy, cervical cytology and detection of cervical HPV DNA. The safety of the treatment was assessed by recording vital signs, local and systemic symptoms, serious adverse events as well as haematological and biochemistry parameters. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of each study centre.

Cytokine production

Cell preparation and antigenic stimulation

PBMCs were separated from 25 ml of fresh calparinated blood diluted with one volume of Hank’s solution pH 7.4, using a Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient. Autologous plasma, removed from the top of the gradient, was stored at –70°C for serology. Fresh PBMCs, 2×106/ml in X-Vivo 20 medium (BioWhittaker) supplemented with 20 U/ml IL-2 in 14-ml round-bottom polypropylene tubes, were cultured overnight at 37°C with or without equimolar amount of activators: 5 μg/ml PD-E7, 3 μg/ml His6-E7 [11], 7.5 μg/ml full-length recombinant H. influenzae protein D (PD, GSK Biologicals, Belgium), 0.4 μg/ml PHA (Innogenetics). Brefeldin A (10 μg/ml, Sigma) was added during the last 3 h of culture. In the blocking experiment, 10 μg/ml of dialyzed W6/32 monoclonal antibody (DAKO) was added 30 min before the antigen.

Cytokine flow cytometry (CFC) assay

For each culture condition, two to three separate staining experiments were performed (1.5×106 cells/staining). Cells, concentrated in 100 μl of the culture medium, were stained for cell surface molecules at 4°C during 20 min with: (i) anti-CD4-PE (5 μl) and anti-CD8-PerCP (10 μl), (ii) anti-CD3-PE (5 μl) and anti-CD8-PerCP (10 μl), (iii) anti-CD3-PerCP (10 μl), anti-CD16-PE (5 μl) and anti-CD56-PE (5 μl) (Becton Dickinson). After washing with PBS, cells were fixed for 20 min at 20°C with 70 μl of solution A (kit FIX and PERM, An der Grub). After an additional washing with PBS, they were simultaneously permeabilized with 70 μl of solution B (kit FIX and PERM) and stained with 7 μl of anti-IFN-γ-FITC (Becton Dickinson) for 20 min at 20°C. After a final wash, cells were resuspended in 400 μl of 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS and acquisition was performed within 24 h on 250,000 events per tube with a flow cytometer. Analysis was performed using Cell-Quest on an SSC/FSC gate on viable lymphocytes. According to the fluorescence markers, the following regions were defined using dot plots and analysed for cytokine producing cells: (1) CD4+CD8− and (2) CD4−CD8+ (staining i), (3) CD3+CD8+ (staining ii) and (4) CD3−CD16/CD56+ (staining iii). Results were expressed as the percentage of cytokine-positive cells in the defined region. Where indicated, background (no activator) was subtracted. A PBMC sample was considered to respond to an antigen when the percentage of T cells producing IFN-γ after stimulation with that antigen was >0.1 and ≥fivefold its background value.

ELISA

Overnight supernatants from PBMC cultures, supplemented with 0.5% BSA and stored at –70°C, were analysed for IFN-γ content in a specific capture ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems).

Serology

HPV-16 E7– and H. influenzae protein D–specific antibodies were measured from the patient’s plasma using ELISA. Microtiter Maxisorp Nunc immunoplates were coated with His6-E7 (5 μg/ml) or PD (2.5 μg/ml) proteins in 0.1-M carbonate buffer pH 9.6, overnight at 4°C. Wells were blocked with PBS 3% BSA for 2 h at 20°C. Test plasma were serially diluted in PBS 1% BSA 0.1% Tween 20 and added to the plate wells in duplicate. After 2-h incubation at 37°C, Ag-specific antibodies were detected by incubating the plates for 2 h at 37°C with sheep antibodies directed against human IgGs, linked to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham) (1:2,000 in PBS 1% BSA 0.1% Tween 20). After a last wash, plates were developed with OPD at 20°C, stopped with 2-N H2SO4 and absorbance read at 490 nm. Specific IgG titres were recorded as the reciprocal of plasma dilution at an absorbance of 0.6.

Statistical analysis of the data

Where indicated, statistical analyses were performed using either paired Wilcoxon signed rank tests or Student’s paired t-tests.

Results

Ten patients, with CIN1 or CIN3 being typed either HPV-16 or positive for oncogenic HPV, have completed the study protocol (Table 1). Seven of those patients received three intramuscular injections of PD-E7 fusion protein mixed to the GSK adjuvant AS02B at 2-week intervals and three were injected with the placebo (Table 1). CIN3 patients underwent conization 4 weeks after the last vaccination and CIN1 patients were followed up at close intervals, except for two women with persistent cytological atypia who were treated either by laser or by conization 6 months after vaccination. The vaccine was well tolerated by all the patients with no serious adverse events either reported or detected ([33] and data not shown).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study patients

| Patient number | Age at enrolment | Lesion | HPV type |

|---|---|---|---|

| V1a | 20 | CIN3 | 16 |

| V2 | 42 | CIN3 | 16 |

| V4 | 40 | CIN3 | 16 |

| V5 | 37 | CIN3 | 16 |

| V6 | 29 | CIN3 | 16 |

| V7 | 27 | CIN1 | 16 |

| V8 | 28 | CIN1 | Oncogenicb |

| P1c | 35 | CIN1 | 16 |

| P2 | 24 | CIN1 | Oncogenic |

| P3 | 29 | CIN1 | Oncogenic |

aV patients received the PD-E7/GSK AS02B vaccine

bOncogenic HPV types (HPV-16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 69) detected by Hybrid Capture II Assay (Digene)

cP patients received the placebo

Systemic cellular immune responses to vaccination

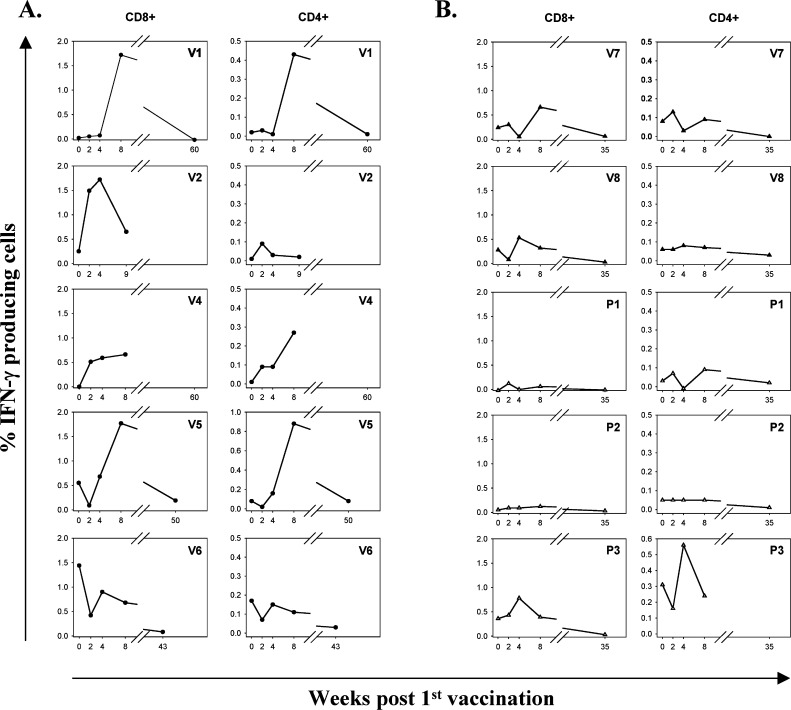

For vaccinated (V1–V8) as well as for placebo-injected (P1–P3) patients, the intracellular IFN-γ production in response to PD-E7 stimulation was analysed at weeks 0 (pretreatment), 2 (post first injection), 4 (post second injection), 8 (post third injection) and between weeks 35 and 60, except for V2 and V4. In the absence of antigen stimulation, very low percentages of cytokine-producing CD4+ (0.029±0.034) and CD8+ (0.033±0.029) cells were enumerated (data not shown). As depicted in Fig. 1, a preexisting CD8+ response to PD-E7 was detected in five (50%) patients (V2, V5–6, V8, P3), with only one also showing a CD4+ response (V6). Vaccination increased the frequency of CD8+ cells producing IFN-γ in response to the vaccine antigen in five out of seven patients (V1–2, V4–5, V7; P<0.05). A single vaccine injection increased the PD-E7–directed IFN-γ T-cell responses in V2 and V4. In contrast, V1, V5 and V7 generated a detectable response to vaccination only after three injections. Four weeks after the third vaccine injection, the PD-E7–specific CD8+ IFN-γ response was the highest for V1 and V5, and 2.5 to 2.7 times lower for V2, V4 and V7. Lower and more variable levels of CD4+ cells responses were detected, with the highest in V5. IFN-γ response to vaccination appeared transient, as shown by an undetectable (V1) or low (V5, V7) reactivity to PD-E7 at weeks 56, 46 and 35 postvaccination, respectively. The kinetics of PD-E7–specific T-cell responses were similar for nonresponding vaccinated patients compared with placebo-injected ones.

Fig. 1A, B.

Kinetics of intracellular IFN-γ production following injection with PD-E7/GSK AS02B or placebo. For all patients, PBMCs prepared at each time point were incubated overnight in vitro with or without PD-E7. Cells were subsequently stained with antibodies to CD4, CD8 and IFN-γ (CFC assay). From 250,000 events gated on viable lymphocytes, CD4−CD8+ and CD4+CD8− cells were analysed for IFN-γ production. Results are expressed as the percentage of IFN-γ-positive CD8+ and CD4+ cells from PD-E7–stimulated PBMCs, with the basal percentage in the absence of antigen subtracted, relative to time postvaccination. For CIN3 patients, background values were 0.014±0.008% for CD4+ cells and 0.018±0.013% for CD8+ cells, whereas for CIN1 patients, values were 0.040±0.030% and 0.049±0.034%, respectively. A V1–V6: CIN3, vaccinated; B V7–8: CIN1, vaccinated and P1–3: placebo-injected

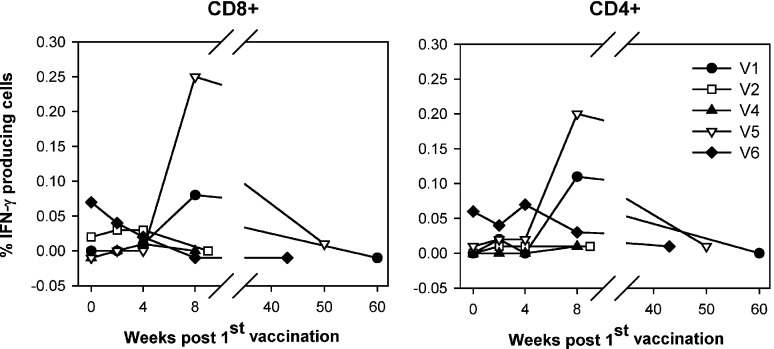

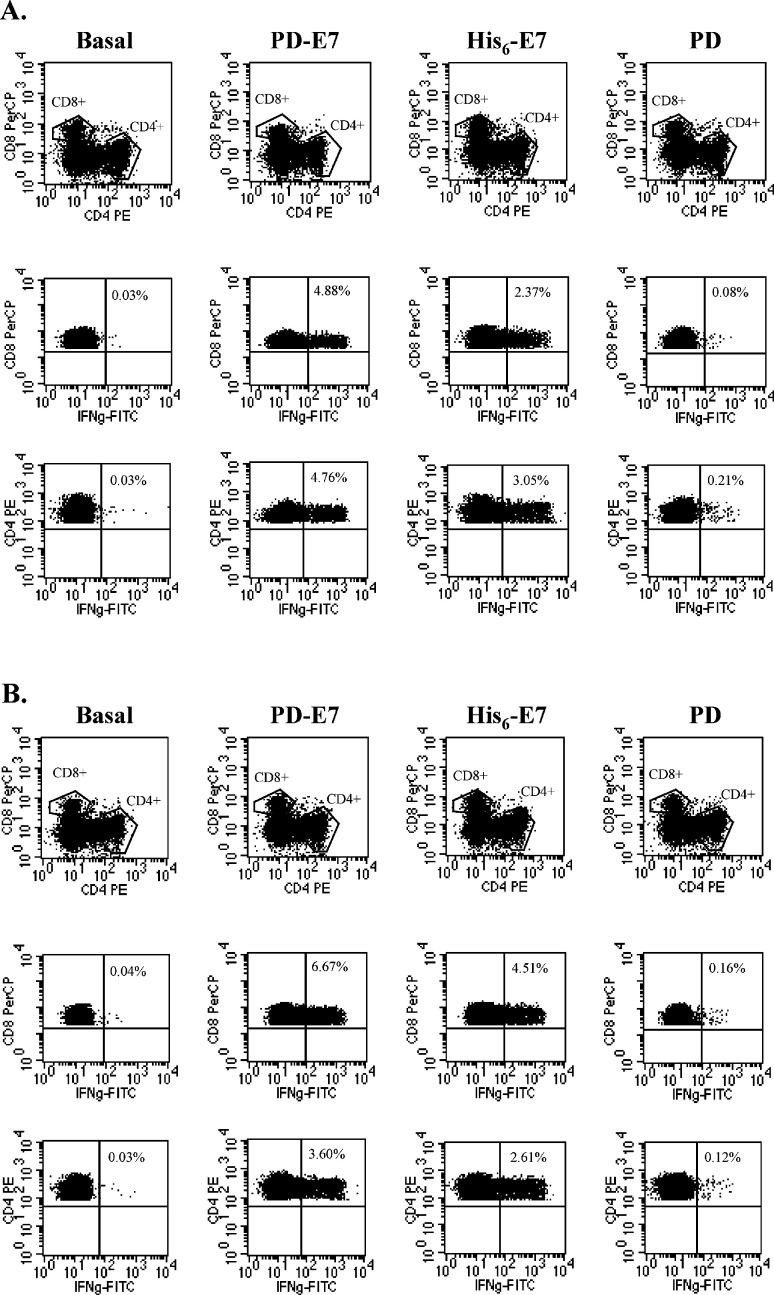

To assess the E7-specificity of the vaccine-induced responses, IFN-γ–producing cells were also counted after stimulation with the His6-E7 protein. From the five tested patients, only V1 and V5 developed a significant CD4+ and CD8+ cell response to His6-E7 and with the same kinetics as those to PD-E7 (peak at week 8) (Fig. 2; P<0.05). When tested 2 years postvaccination, V1 and V5 were revealed by CFC analysis to still generate strong IFN-γ CD4+ and CD8+ cell responses to both PD-E7 (P<0.01) and His6-E7 (P<0.01), and a weak CD4+ cell response to full length PD (P<0.05) (Fig. 3). These data suggest the establishment of a long-term IFN-γ T-cell response to the vaccine antigen and most probably to E7 in at least 28% of the vaccinated patients.

Fig. 2.

Kinetics of His6-E7–specific intracellular IFN-γ production in vaccinated CIN3 patients. PBMCs prepared at each time point were stimulated overnight in vitro with no antigen or with His6-E7. Cells were subsequently stained with antibodies to CD4, CD8 and IFN-γ (CFC assay). From 250,000 events gated on viable lymphocytes, IFN-γ-positive CD4−CD8+ and CD4+CD8− cells were enumerated. Results are expressed as the percentage of IFN-γ-positive CD8+ and CD4+ cells from His6-E7–stimulated PBMCs, with the basal percentage in the absence of antigen subtracted relative to time postvaccination. The background values were 0.014±0.008% for CD4+ cells and 0.018±0.013% for CD8+ cells

Fig. 3A, B.

Typical CFC analysis performed with PBMCs from patients V1 and V5, 2 years postvaccination, showing reactivity to PD-E7 and His6-E7, but not to H. influenzae protein D. PBMCs were stimulated overnight in vitro with no antigen or with PD-E7, His6-E7 or PD. Cells were subsequently stained with antibodies to CD4, CD8 and IFN-γ and analysed by flow cytometry (CFC assay). For each stimulation condition, dot plots show the CD8+CD4− and CD8−CD4+ regions renamed CD8+ and CD4+ cells, respectively (top graphs) and the percentage of IFN-γ-positive CD8+ cells (middle graphs) and CD4+ cells (bottom graphs). Results from V1 (A) and V5 (B) are presented

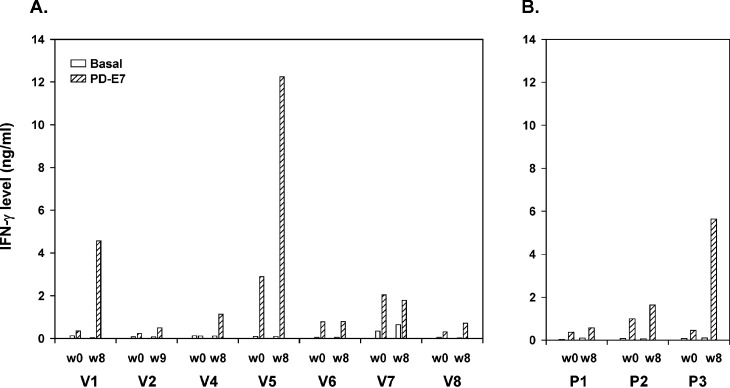

Cytokine responses in prevaccine and postvaccine PBMCs were further confirmed by performing a specific ELISA on week 0 and week 8 PBMC supernatants. ELISA and CFC results were mostly concordant, with three among seven patients recorded as responding to vaccination with ELISA versus five with CFC. In agreement with our CFC data, the highest IFN-γ levels were found in V1 and V5 PD-E7–stimulated postvaccine PBMC supernatants (Fig. 4A). The weak CFC responses of patients V2 (CIN3) and V7 (CIN1) were not detectable by ELISA. All the supernatants from the PD-E7–stimulated CIN1 PBMCs contain detectable levels of IFN-γ, whereas one placebo patient (P3) showed a higher amount of cytokine production in week 8 supernatant than in week 0 sample (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4A, B.

Monitoring of IFN-γ response to E7 proteins using ELISA. PBMCs prepared before and after vaccination/placebo injection were stimulated overnight in vitro with no antigen or with PD-E7, and their supernatants were tested for IFN-γ content using ELISA. Results from vaccinated (A) and placebo-injected (B) patients are presented

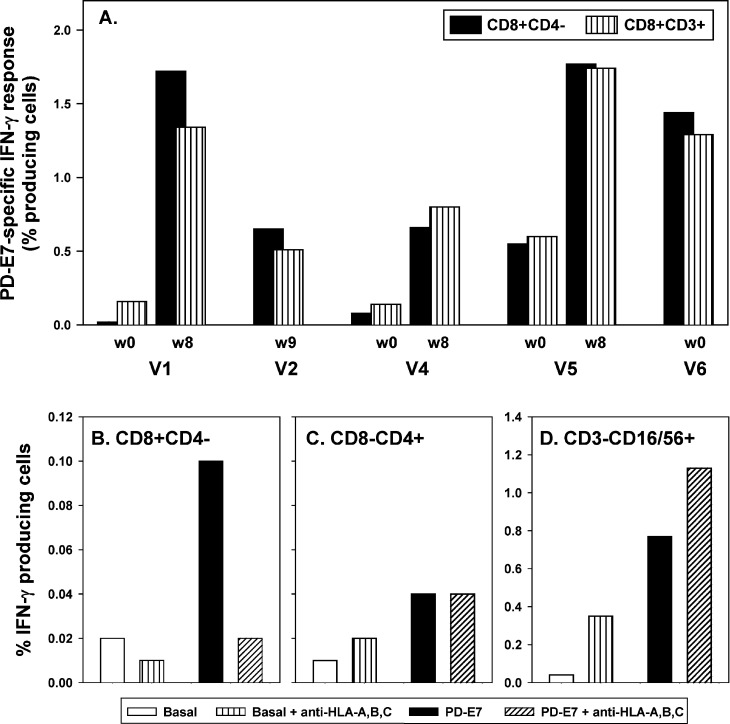

Characterization of the CD8+ cells producing IFN-γ in response to PD-E7 stimulation

We sought to further confirm that the IFN-γ response to PD-E7, measured by CFC, was actually a T-cell response. Firstly, we compared the percentage of cytokine-producing cells within the CD8+CD4− and CD8+CD3+ PD-E7–stimulated populations that were of comparable size (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 5A, similar percentages of IFN-γ–producing cells were detected in both PBMC populations, at each time point and for all the tested patients. The good correlation between these two cells populations for IFN-γ response (r 2=0.85) further suggests their identity. Secondly, using a blocking antibody against HLA-A, HLA-B and HLA-C, we showed that the reactivity of CD8+CD4− cells to PD-E7 was MHC class I–restricted (Fig. 5B), whereas that of CD8−CD4+ cells was not modified (Fig. 5C) and that of CD3−CD16/56+ cells was slightly increased (Fig. 5D). The small percentages of CD8+CD4− (Fig. 5B) and CD8−CD4+ (Fig. 5C) cells that spontaneously produced IFN-γ were not affected by MHC class I blocking whereas that of CD3−CD16/56+ cells was increased (Fig. 5D). These data suggest that IFN-γ–producing CD8+CD4− cells assessment reflects PD-E7–specific MHC class I–restricted T-cell responses.

Fig. 5A–D.

CD8+CD4− IFN-γ response to PD-E7 as measured by CFC is a MHC class I–restricted T-cell response. A PBMCs prepared before and after vaccination were stimulated overnight in vitro with no antigen or with PD-E7 and subsequently stained with antibodies directed either to CD8, CD4 and IFN-γ, or CD8, CD3 and IFN-γ. The net PD-E7–specific response is expressed as the percentage of IFN-γ–producing CD8+CD4− and CD8+CD3+ cells (basal production was subtracted). B-D V6’s PBMCs (week 43), preincubated or not with W6/32 monoclonal antibody, were stimulated overnight in vitro with no antigen or with PD-E7. Cells were then stained with antibodies directed either to CD4, CD8 and IFN-γ, or CD3, CD16/56 and IFN-γ. For each stimulation condition the CD8+CD4−, CD8−CD4+ and CD3−CD16/56+ cells producing IFN-γ were enumerated and results are displayed in B, C and D, respectively

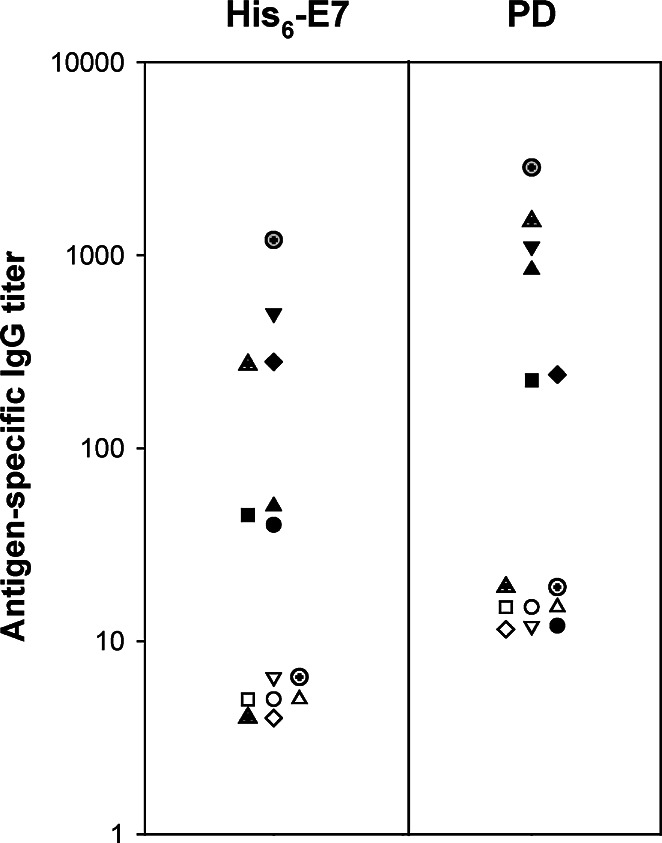

Humoral responses before and after vaccination

The titres of His6-E7- and PD-specific IgG in plasma are shown in Fig. 6. All the study patients had undetectable plasma IgG responses to either His6-E7 or PD before treatment (Fig. 6; and data not shown). At 4 weeks after the final injection, all the vaccinated patients generated weak (V1–2, V4) or moderate (V5–8) anti–His6-E7 antibody responses (P<0.05) whereas placebo-injected ones did not. Knowing that an IgG response is a surrogate marker for CD4+ T-cell response, it is interesting to note that V5 is one out of the two patients who had a detectable CD4+ IFN-γ response to His6-E7 at week 8 (Fig. 2). The reactivity of postvaccination plasma to His6-E7 was confirmed in a Western blot (data not shown). Six out of the seven vaccinated patients also developed a PD-specific IgG response (P<0.05). The anti-PD IgG titres were low for V2 and V6 and moderate for V4–5, V7–8. The average anti–His6-E7 antibody titres postvaccination were 2.8-fold lower than their average anti-PD titres (341 vs 971).

Fig. 6.

Prevaccination and postvaccination humoral responses to E7 and H. influenzae protein D. For each of the vaccinated patients, antibodies to His6-E7 and PD were detected from plasma taken at weeks 0 (open symbol) and 8 (closed symbol) by ELISA. The mean specific IgG titres are expressed as the reciprocal plasma dilution at an absorbance of 0.6 (V1: circle, V2: square, V4: triangle up, V5: triangle down, V6: diamond, V7: hatched triangle, and V8: hatched circle)

Discussion

PD-E7, a fusion protein comprising a mutated HPV-16 E7 and the amino-terminal third of H. influenzae protein D, has been shown to effectively cure mice from HPV-16-positive growing tumour, when administrated with the GSK adjuvant AS02B [9]. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the immunogenicity of this vaccine in CIN patients. Women harbouring oncogenic HPV, and not only HPV-16, were enrolled because T-cell cross-reactivity between HPV types has been previously described [7, 10, 37]. Seven patients, five HPV-16-positive CIN3 and two CIN1, received three intramuscular injections of PD-E7 with adjuvant, whereas three CIN1 patients were injected with a placebo. Within the 8 weeks after vaccination, the majority of the patients developed significant systemic vaccine antigen-specific IFN-γ (5/7) and antibody (7/7) responses. No antibody response was detected in the placebo patients and only one of them showed an IFN-γ response. Interestingly, this patient showed the highest viral load (data not shown).

Although this clinical trial has been performed on a relatively small number of patients, some interesting findings were made. First, we demonstrated that CFC is a valid method for the monitoring of T-cell responses after vaccination against HPV-16 E7. HPV-directed cellular immune responses, which are known to play a crucial role in the eradication of HPV-infected cells, are usually weak and difficult to measure. Consequently, most of the studies described memory T-cell responses analysed after several steps of antigenic stimulation [2]. To characterize ongoing E7-specific cellular immune response, we used the sensitive and qualitative CFC technique which had already proven to be useful to monitor T-cell responses after antitumour vaccination [15, 23]. We showed that an overnight in vitro stimulation with the recombinant PD-E7 protein induces a significant percentage of PBMC-derived CD8+ T cells to produce IFN-γ. We further demonstrated that the specific CD8+ IFN-γ responses are indeed MHC class I–restricted T-cell responses. IFN-γ production was detectable before vaccination both in CIN1 and CIN3 patients. The percentage of IFN-γ–producing cells determined by CFC was positively correlated with the cytokine level in PBMC supernatant assessed by using a specific ELISA. Second, PD-E7/GSK AS02B was immunogenic in patients harbouring CIN lesions. The majority of the patients (four out of five CIN3 and one out of two CIN1) developed systemic PD-E7–directed T-cell responses after vaccination, characterized by a predominant CD8+ IFN-γ response. This phenotypic pattern suggests that vaccination has induced the expected type 1–specific T-cell response. Moreover, the responses that we observed might be immunologically effective; indeed, their levels are in the same range as many antiviral T-cell responses measured with CFC assays [23]. In spite of a transient decrease in anti–PD-E7 T-cell responses detected between weeks 50 to 60, three vaccine injections generated memory T cells, at least in 40% of the responding patients. PD-E7–directed IFN-γ response was not significantly modified following placebo injection. All the vaccinated patients (7/7), not the placebo-injected ones (0/3), made significant levels of E7-specific plasmatic IgG with six of them having also produced anti-PD IgG. Accordingly, none of the study patients was positive before treatment (0/10). The presence of anti-E7 IgG indirectly proves that vaccination has activated E7-specific CD4+ T cells. In addition to these systemic immune responses, the vaccination resulted in the infiltration of the CIN3 stroma with CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as previously described [33]. A similar T-cell infiltration was also observed in one vaccinated CIN1 patient (data not shown) and could not be documented in the other one because no lesion was detected at the time of biopsy. Third, the cervical lesion disappeared in two vaccinated CIN1 patients whereas one progressed to CIN2 during the protocol (data not shown). Among the placebo CIN1 patients, two spontaneously eliminated their lesion but it must be noticed that these patients had, at the beginning of the clinical protocol, a very low viral load which has been shown to be negatively correlated with viral persistence (data not shown) [13]. These data confirm the frequent spontaneous regression of CIN1 with a low amount of HPV DNA, making this category of patients inappropriate for the evaluation of vaccine efficacy. For that purpose, CIN1 with a high and persistent viral load and CIN3 patients whose lesions regress at a lower rate and progress rather slowly should be more suitable. In CIN3 patients, no viral clearance or lesion regression was observed after vaccination [33]. This lack of clinical response might be related to both the histological evaluation date (too early after the last vaccine injection) and the induction of a too weak immunization. Future studies are planned to determine whether an increase of the clinical assessment window to 5 months, a short period compared with the natural history of CIN [25], is required to observe HPV clearance and histological response after vaccination. On the other hand, our data showed that three vaccine injections generate low antibody responses in all the patients and do not increase specific T-cell responses in all of them. These findings suggest that a further validation of this vaccine should be performed to determine whether increasing the number of vaccinations could increase the percentage of responding patients and generate a stronger immunity.

It must be noted that we have not definitively proven that all the PD-E7–activated IFN-γ+ T cells are actually E7-specific. Their relatively high frequencies (ranging between 0.25% to 1.77% of blood CD8+ T cells) measured using CFC, are probably related to the global immune response to PD-E7. However, others have reported similar or even higher amounts of virus- or tumour-specific T cells [1]. Presently, the best tools for assessing CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell specificity are tetrameric MHC class I or class II molecules loaded with specific antigenic peptides, but they only allow for the analysis of single specificities and are not predictive of T-cell function [20]. Stimulating PBMCs with pools of Ag-derived synthetic peptides might test a larger range of specificities.

Although the small sample size of this study precludes us from formulating definitive conclusions, our data highlight the potential interest of the PD-E7/GSK AS02B vaccine. The efficacy of this treatment has to be studied, however, in a larger group of CIN patients with a high and persistent load of oncogenic HPV.

Acknowledgements

We thank GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Belgium, for providing the study vaccine. Sonia Pisvin and Renee Gathy provided excellent technical assistance. P.D. and N.J. are supported by the Belgian National Fund for Scientific Research. This work was supported by the Yvonne Boël Foundation, the Belgian National Fund for Scientific Research and the Region Wallonne.

References

- 1.Baurain J Immunol. 2000;164:6057. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.6057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bontkes Int J Cancer. 2000;88:92. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001001)88:1<92::AID-IJC15>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bory Int J Cancer. 2002;102:519. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;121:216. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson Cancer Res. 2003;63:6032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;15:677. doi: 10.1053/beog.2001.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Cancer Res. 2002;62:472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galloway Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:469. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00720-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerard Vaccine. 2001;19:2583. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstone Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:502. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6229-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallez Int J Cancer. 1999;81:428. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990505)81:3<428::AID-IJC17>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1365. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.18.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho Int J Cancer. 1998;78:594. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19981123)78:5<594::AID-IJC11>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jochmus Arch Med Res. 1999;30:269. doi: 10.1016/S0188-0128(99)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karanikas Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kast Semin Virology. 1996;7:117. doi: 10.1006/smvy.1996.0015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaufmann Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3676. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kjaer BMJ. 2002;325:572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7364.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klencke Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1028. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klenerman Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:263. doi: 10.1038/nri777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ling J Biomed Sci. 2000;7:341. doi: 10.1159/000025470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu J Virol. 2000;74:2888. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.6.2888-2894.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maecker Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:902s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mantovani Oncogene. 2001;20:7874. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melnikow Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:727. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(98)00245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milojkovic Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;76:49. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muderspach Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munger Oncogene. 2001;20:7888. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagai Gynecol Oncol. 2000;79:294. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noel Hum Pathol. 2001;32:135. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.20901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reich Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:193. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(01)01683-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santin N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1752. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200205303462219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;109:219. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(03)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steller Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Int J Cancer. 2001;91:612. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200002)9999:9999<::AID-IJC1119>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:946. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams J Virol. 2002;76:7418. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.15.7418-7429.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.zur Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:342. doi: 10.1038/nrc798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]