Abstract

Doxorubicin is a commonly used cytotoxic drug for effective treatment of both solid tumors and leukemias, which may cause severe cardiac adverse effects leading to heart failure. In certain tumor cells, doxorubicin-induced cell death is mediated by death receptors such as CD95/Apo-1/Fas. Here we studied the role of death receptors for doxorubicin-induced cell death in primary neonatal rat cardiomyocytes and the embryonic cardiomyocytic cell line H9c2.1. Doxorubicin-induced cell death of cardiomyocytes was associated with cleavage of caspases 3 and 8, a drop in mitochondrial transmembrane potential, and release of cytochrome c. Doxorubicin-treated cardiomyocytes secreted death-inducing ligands into the culture supernatant, but remained resistant toward cell death induction by death receptor triggering. In contrast to the chelator dexrazoxane, blockade of death receptor signaling by stable overexpression of transdominant negative adapter molecule FADD did not inhibit doxorubicin-induced cell death. Our data suggest that cultured cardiomyocytes secrete death-inducing ligands, but undergo death receptor–independent cell death upon exposure to doxorubicin.

Keywords: Cardiomyocytes, CD95/Apo-1/Fas, Death receptors, Doxorubicin, FADD-DN

Introduction

For some decades now, the anthracyclin doxorubicin has been a key element in chemotherapy protocols for both solid tumors and leukemias due to its high antitumor efficiency. However, its use is limited by cardiac adverse effects mostly leading to dose-dependent irreversible dilative cardiomyopathy with consequent organ failure [19]. The mechanisms responsible for doxorubicin-induced heart disease are not yet completely understood and involve cell death by apoptosis [26] mediated by calcium overload and iron-catalyzed formation of free radicals among others [1]. Dexrazoxane (Zinecard) is an intensively studied adjuvant which protects cells from doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity preventing free radical formation through chelation of iron in the Fe3+-(anthracyclin)3 complex [12, 31]. Key executioner of doxorubicin-induced cell death of cardiomyocytes are mitochondria which, upon stimulation with doxorubicin, release cytochrome c [5], generate highly reactive free radical intermediates [34], and present long-lasting respiratory chain defects [21]. Doxorubicin treatment leads to regulation of different members of the Bcl-2 family in cardiac cells, although conflicting data exist [5, 20, 35]. In a cell free system, doxorubicin derivates were shown to directly activate the apoptogenic function of mitochondria [7], but delayed kinetics in cell culture experiments and animal trials suggest an indirect activation of cardiomyocytic mitochondria by doxorubicin in vivo mediated by yet-undefined signaling proteins.

Important factors which indirectly lead to depolarization of mitochondria are the death-inducing ligands (DILs) CD95/Apo-1/Fas-ligand (CD95L), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) [33]. DILs are membrane-bound proteins whose expression is induced or up-regulated upon different stimuli of cellular stress [13]; e.g., by cytotoxic drugs [9]. DILs can be cleaved into a soluble form by metalloproteinases [18], TACE, or cysteinproteinases in the case of CD95-L, TNF-α, or TRAIL, and bind to their respective death receptors CD95 (Apo-1, Fas), TNF-RI, and TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 to initiate apoptosis. Upon ligand-induced multimerization, death receptors recruit the adapter molecule FADD to their death domain which enables activation of caspase-8 [6]. FLIP which lacks caspase activity can also bind to FADD and disable activation of caspase-8. During the process of apoptosis signaling by DILs, reactive oxygen radicals are formed [32] which induce up-regulation of DILs [10]. Direct activation of downstream caspases by caspase-8 is characteristic for type I cells, while type II cells require amplification of the death signal by mitochondria and the apoptosome [29].

In certain, but not all, tumor cells, the CD95 pathway contributes to doxorubicin-induced cell death—e.g., in leukemia cells [9] and neuroblastoma cells [11, 28], while in other tumor cells, doxorubicin-induced cell death is independent from the CD95 system [23]. Therefore, and as DILs strongly activate mitochondria and form radicals during execution of apoptosis, we asked whether death receptors might mediate doxorubicin-induced cell death in cultured cardiomyocytes.

Materials and methods

Materials

For Western blot, anti-CD95L antibody was purchased from PharMingen (Heidelberg, Germany); TRAIL antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz (Heidelberg, Germany); TNF-α antibody was purchased from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany); anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody from Cell Signaling Technologies (Frankfurt/Main, Germany); anti-αTubulin antibody from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA); anti-FLIP antibody from ProSci (Poway, CA, USA); and anti-caspase-8 antibody was a kind gift by M. Peter. Agonistic anti-CD95 antibody Jo-2 and inhibitory anti-CD95L antibody NOK-1 (added daily at 1 μg/ml) were purchased from PharMingen (Heidelberg, Germany). Cytochrome c was stained using monoclonal mouse antibody from PharMingen (Heidelberg, Germany); DiOC6 was purchased from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany). TNF-α was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA); TRAIL was produced in Pichia pastoris [16]; recombinant CD95L was from Alexis (Gruenberg, Germany). Dexrazoxane (Zinecard) was obtained from Pfizer (New York, NY, USA); collagenase type II was from Biochrom (Berlin, Germany); laminin from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany) and zVAD from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Cell culture reagents were obtained from Gibco/Life Technologies (Karlsruhe, Germany), and all further agents were obtained from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany).

Cell culture

Primary neonatal rat cardiac cells were prepared as described previously [30]. Cells were seeded on laminin-pretreated dishes in DMEM for 2–5 days before experiments were performed. Neonatal rat cardiac cells consisted of >80% solely beating myocytes and were therefore called cardiomyocytes. Nonbeating cells might represent cardiac endothelial cells or fibroblasts. H9c2.1 were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS.

Cell death experiments

Cell death experiments were performed in the absence of FCS. When cells were stimulated with two substances, both agents were added at the same time; NOK-1 was added at 0.5 μg/ml every 24 h, and zVAD was added at 40 μM every 8 h. Cell death was assessed according to Nicoletti by flow cytometric measurement of hypodiploid nuclei indicating nuclear loss of DNA by DNA fragmentation upon apoptosis induction [24]. Specific cell death was calculated as (absolute cell death of stimulated cells minus absolute cell death of control cells) divided by (100 minus absolute cell death of control cells) times 100. Results are presented as mean of duplicates ± standard error (SE) if SE was over 5%. Experiments were performed at least three times independently.

Sensitization for, or inhibition of, cell death was calculated using the fractional inhibition product [36]. In brief, specific survival was calculated as 1 − specific cell death. Expected survival by, e.g., coincubation of DIL together with doxorubicin was calculated as (specific survival by DIL alone) × (specific survival by doxorubicin alone). Antagonism or synergism was accepted, when expected survival minus measured survival was <−0.1 or >0.1, respectively.

Stable transfection

FADD-DN expression vector was cloned by Chinnaiyan et al. [6]. H9c2.1 cells were transfected using Effectene (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations which yielded a 30% transfection efficacy as measured using gfp-expressing control vector and FACscan (data not shown). After overnight incubation, cells were washed and left 3 days to recover. Geneticin was added at 100 μg/ml, and surviving cells were cultured for 8 weeks before Western blot and cell death experiments were performed.

Western blot analysis

Supernatants were centrifuged to remove cells and concentrated using membrane exclusion centrifugation (Greiner, Tuttlingen, Germany; exclusion of proteins smaller than 5,000 kDa) to a total volume of 60 μl/10 ml. Total cellular protein was obtained lysing cells as described previously [16]. Aliquots of 10 μl, or 20 μg total cellular protein, were subjected to Western blot analysis, respectively, which was performed as described previously [16]. Briefly, total cellular protein was isolated, run on a 12% polyacrylamide gel, blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and incubated with specific primary antibody and HRP-labeled secondary antibody, which was visualized by luminescence.

Measurement of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and cytoplasmic cytochrome c

For measurement of mitochondrial transmembrane potential, cells were stained with DiOC6 and analyzed by FACscan. Flow cytometric measurement of mitochondrial cytochrome c release was performed by permeabilization using saponin and staining with a conformation-specific mouse anti-cytochrome c antibody, followed by a FITC-labeled goat antimouse antibody, and measurement in fluorescence-1 in FACscan. The anti-cytochrome c antibody shows a reduced binding for cytoplasmic cytochrome c [15]; maintenance of a high cytochrome c signal is observed in cells with reduced mitochondrial activation upon apoptosis induction, such as Bcl-2 overexpressing cells (data not shown).

Results

Cell death induction

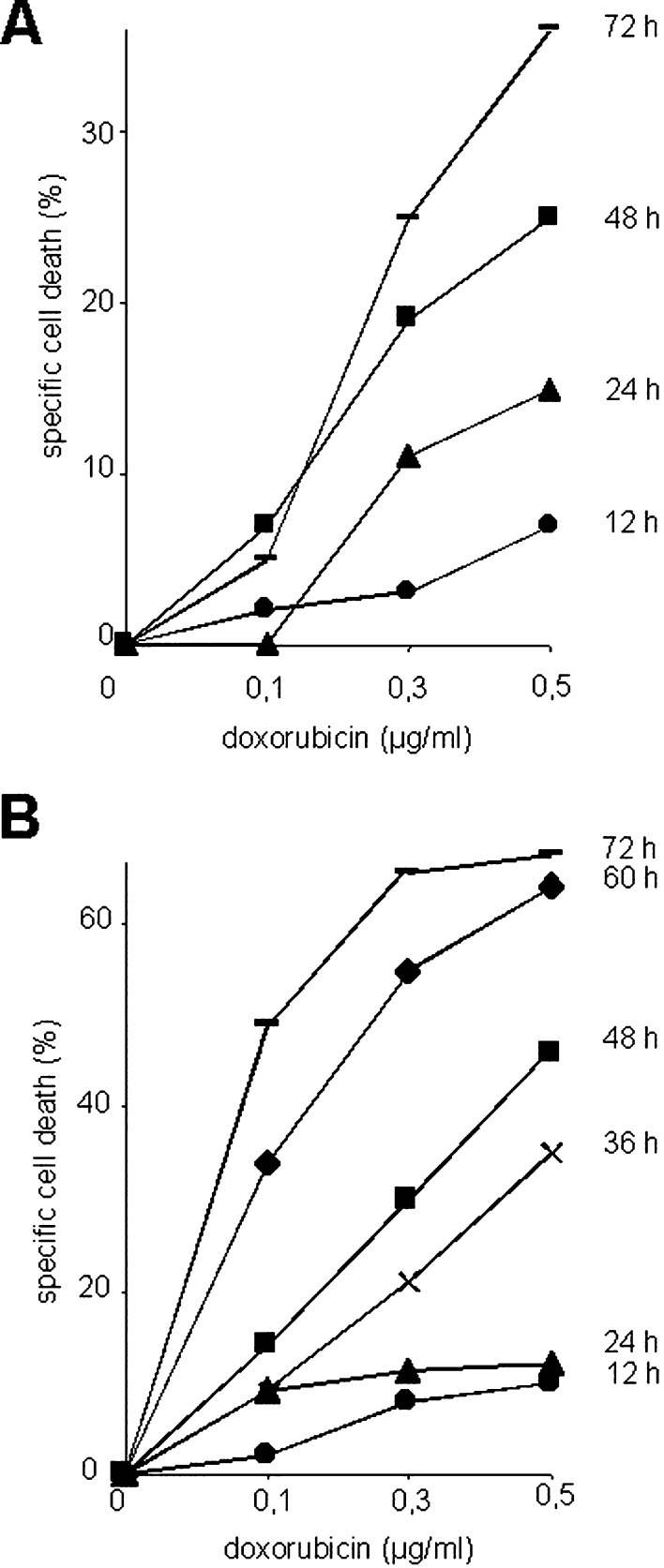

Doxorubicin-induced cell death is mediated by death receptor signaling in certain tumor cells. To study the role of death-inducing ligands (DILs) and their receptors, in doxorubicin-induced cell death in cardiomyocytes, we cultured the embryonic cardiomyocytic cell line H9c2.1 and primary neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Only the latter cells beat spontaneously. Doxorubicin was used up to peak concentrations measured in plasma of patients during anticancer treatment (0.5 μg/ml=0.9 μM) [8] and induced time- and dose-dependent cell death in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1a, b). The embryonic cell line H9c2.1 displayed higher sensitivity toward doxorubicin-induced cell death than did primary rat neonatal cardiomyocytes.

Fig. 1.

Cell death induction by doxorubicin. Primary neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (a) or H9c2.1 cells (b) were incubated with doxorubicin for time periods indicated. Cell death was assessed by flow cytometric measurement of hypodiploid nuclei, and specific cell death was calculated as described in “Methods.”

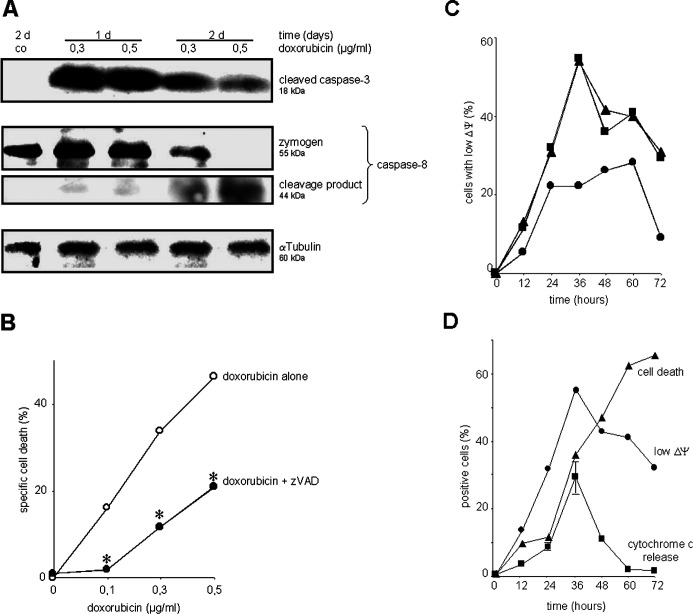

For intracellular cell death signaling, cardiomyocytes activated caspase-3 and caspase-8 upon triggering with doxorubicin (Fig. 2a). The cleavage product of caspase-3 appeared most prominent after 1 day of incubation with doxorubicin, while the cleavage product of caspase-8 peaked a little later. The broad-spectrum caspase-inhibitor zVAD attenuated doxorubicin-induced cell death (Fig. 2b). Mitochondrial transmembrane potential was diminished by doxorubicin in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 2c), and cytochrome c was released. Both loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and release of cytochrome c peaked at 36 h, declining thereafter and preceding cell death (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Doxorubicin-mediated cell death involves activation of caspases and mitochondria. H9c2.1 cells were stimulated with doxorubicin as indicated. a Total cellular protein was analyzed by Western blot for caspase-8 zymogen and cleavage product as well as cleaved caspase-3. αTubulin served as loading control. One representative experiment out of three is shown. b Cells were stimulated with doxorubicin for 48 h either in the absence (open circles) or presence (closed circles) of broad-spectrum caspase-inhibitor zVAD applied at 40 μM every 8 h; *p<0.05 comparing equal concentration of doxorubicin with and without zVAD. c Cells were stimulated with doxorubicin 0.1 μg/ml (circles), 0.3 μg/ml (squares), or 0.5 μg/ml (triangles), then stained with DiOC6, and mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔP) was measured in FACscan. d Cells were stimulated with doxorubicin 0.5 μg/ml, cell death was measured as in Fig. 1, and mitochondrial transmembrane potential as in (c). Cytoplasmic cytochrome c was stained using an conformation-specific antibody and visualized using FACscan (see “Methods”); shown is mean ± SE. Data are mean of duplicates with a standard deviation less than 5%, one representative experiment out of three is shown.

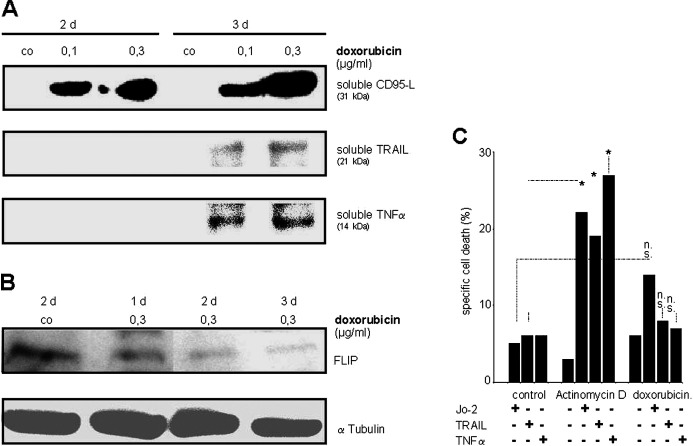

Secretion of DILs, but lack of sensitization for DIL-induced cell death

Supernatants of primary neonatal rat cardiomyocytes exposed to doxorubicin were concentrated and analyzed by Western blot. Soluble forms of CD95-L, TRAIL, and TNF-α were released into the culture supernatant upon doxorubicin treatment (Fig. 3a). Cellular FLIP was decreased by stimulation of cells with doxorubicin, but was still present after 3 days (Fig. 3b). DILs did not induce cell death in unstimulated primary neonatal rat cardiomyocytes or H9c2.1 cells, indicating that both cells types are constitutively resistant toward cell death induction by death receptor engagement (Fig. 3c). Since treatment with actinomycin D (Fig. 3c) or cycloheximide (data not shown) sensitized both cells for cell death induction by DILs, death receptor systems are present and functional in cultured cardiomyocytes. In contrast, doxorubicin did not sensitize either primary rat cardiomyocytes (data not shown) or H9c2.1 cells for DIL-induced cell death in a panel of different experimental procedures including pretreatment and extension of incubation periods for up to 72 h (Fig. 3c; and data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Cardiomyocytes secrete DILs upon doxorubicin treatment, but are not sensitized for cell death induction by DILs. a Confluent beating primary neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (65 cm2) in 10 ml medium were exposed to doxorubicin as indicated. Cell supernatant (10 ml) was concentrated to 60 μl, 10 μl was analyzed in Western blot for presence of DILs. One representative experiment out of three is shown. b H9c2.1 cells were treated with doxorubicin 0.3 μg/ml as indicated. Total cellular protein was subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-FLIP antibody. αTubulin served as loading control. c H9c2.1 cells were stimulated with Jo-2 1 μg/ml, TRAIL 3 μg/ml, and TNF-α 300 ng/ml in the presence or absence actinomycin D (1 μg/ml) or doxorubicin (0.3 μg/ml) for 24 h. Cell death was measured as in Fig. 1. co Control, *sensitisation as calculated by the fractional inhibition method (see “Methods”) for the two parameters connected by each bar, n.s no sensitization.

Independence of doxorubicin-induced cell death from DILs

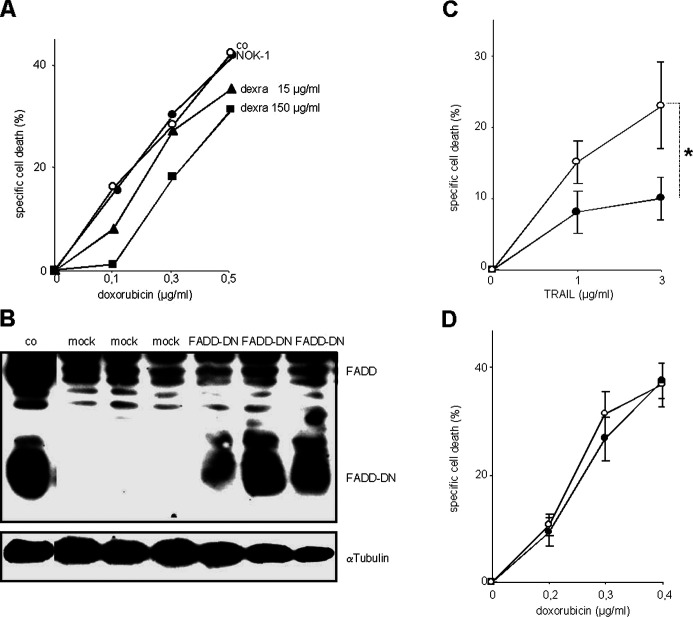

Cell death signaling by DILs can be blocked at different steps of the signaling cascade. The inhibitory antibody NOK-1 disables binding of CD95L to CD95 and did not alter doxorubicin-induced cell death of primary cardiomyocytes (data not shown) or H9c2.1 cells, while dexrazoxane did so to a certain, statistically nonsignificant extend (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Doxorubicin-induced cell death in cardiomyocytes is not mediated by death receptors. a H9c2.1 cells were incubated with doxorubicin for 2 days without (open circles) or with (closed circles) NOK-1 antibody which inhibits interaction of CD95L with CD95, or the chelator dexrazoxane (dexra, triangles and squares). Cell death was measured as in Fig. 1. co Control. b H9c2.1 cells were stably transfected either with empty vector (mock) or with vector containing the expression plasmid for FADD-DN (FADD-DN) in three independent transfections. Transfected cells were selected by incubation with Geneticin for 8 weeks. Total cellular protein of cells of each transfection was subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-FADD antibody. αTubulin served as loading control. co Control proteins of Jurkat cells stably transfected with FADD-DN expression vector. c, d Mock-transfected H9c2.1 cells (open circles) or H9c2.1 cells expressing FADD-DN (filled circles) were stimulated with TRAIL, as indicated, in the presence of cycloheximide 2 μg/ml (c) or with doxorubicin (d) in concentrations indicated, for 48 h. Cell death was measured as in Fig. 1. Shown is mean of five independent experiments each from the three independent transfections. *p<0.05, compared with equally stimulated, mock-transfected cells.

To block signaling at a level immediately downstream of all death receptors, the adapter molecule FADD was addressed which directly binds to death receptors and is indispensable for death receptor signaling. A dominant negative form of FADD (FADD-DN) at high levels competitively dislocates endogenous FADD from death receptors and diminishes cell death signaling by all DILs. As high levels of FADD-DN are needed to effectively compete with endogenous FADD, stable transfection was performed followed by several weeks of selection of high FADD-DN–expressing cells. Primary neonatal rat cardiomyocytes do not allow prolonged cell culture, therefore these experiments were performed in H9c2.1 cells. Stable transfection of FADD-DN DNA containing vector into H9c2.1 cells leads to marked expression of the dominant negative FADD protein (Fig. 4b) and significantly decreased cell death induction by the DIL TRAIL (in the presence of cycloheximide, Fig. 4c). In contrast, FADD-DN did not alter doxorubicin-induced cell death in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4d), suggesting that doxorubicin-induced cell death in cultured H9c2.1 cardiomyocytes is independent from signaling by death receptors.

Discussion

Our data show that doxorubicin-induced cell death in cultured cardiomyocytes activated intracellular cell death signaling molecules such as caspases, cytochrome c, and DILs, but occurred independently from death receptors. Despite the use of identical experimental conditions and in contrast to results obtained by others [25, 38], pretreatment with doxorubicin did not overcome the resistance of cultured cardiomyocytes toward cell death induction by DILs in our hands, and inhibition of death receptor signaling did not alter doxorubicin-induced cell death in these cells. The role of death receptors for doxorubicin-induced cell death thus depended on the target cell: While death receptors mediated doxorubicin-induced cell death, at least in certain tumor cells [9, 11, 28], death receptors were dispensable for doxorubicin-induced cell death of cultured cardiomyocytes.

H9c2.1 cells were found resistant toward apoptosis induction by DILs (Fig. 3c). Various stimuli activate the intrinsic apoptosis-signaling pathway in H9c2.1 cells leading to alteration of mitochondrial transmembrane potential, release of cytochrome c, and activation of caspases which is regulated by members of the Bcl-2 family [3]. In contrast, the signaling pathway upstream of activation of mitochondria remains still unknown for any stimulus including DILs. Resistance toward DIL-induced cell death by cultured cardiomyocytes might rely on the presence of inhibitory FLIP which is down-regulated, but still present after stimulation with doxorubicin. H9c2.1 cells are sensitized for apoptosis induction by DILs using inhibitors of activation of nuclear factor kappaB (NFκB) [2] or inhibitors of protein neosynthesis such as actinomycin D and cycloheximide (Fig. 3c). Thus, presence of antiapoptotic proteins including FLIP (Fig. 3b) might be responsible for apoptosis resistance of H9c2.1 cells toward DILs.

We demonstrated involvement of mitochondrial apoptosis-signaling by measurement of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential ΔΨM by the potential sensitive cationic dye DiOC6 [3] and the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c. Loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential indicating permeabilization of the inner mitochondrial membrane was paralleled by cytochrome c release, which marked permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane and preceded cell death in doxorubicin-treated cardiomyocytes. Doxorubicin-induced alteration of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and cytochrome c release as well as cell death could not be detected in all cells. Thus, the decline in the percentage of cells with low mitochondrial transmembrane potential at later time points may indicate surviving or unaffected cells. In addition, we showed involvement of caspases in this process as the broad caspase inhibitor zVAD attenuated doxorubicin-induced cell death. Interestingly, we found activation of caspase-3 peaked before that of caspase-8, mitochondrial depolarization and cytochrome c release suggesting that caspase-3 was activated prior to caspase-8 and mitochondrial depolarization. In contrast, in death receptor–mediated signaling, activation of caspase-8 preceded activation of caspase-3 and mitochondria, at least in type I cells [29]. Thus, cardiomyocytes stimulated with doxorubicin did not behave like type I cells stimulated with CD95.

Apart from doxorubicin, secretion of soluble DILs by cardiomyocytes was found upon other forms of cellular stress, e.g. ischemia/reperfusion injury [17]. However, and in contrast to doxorubicin, postischemic reperfusion was further mediated at least in part by death receptors [4, 17]. Thus, secretion of DILs seemed an unspecific reaction to cellular stress of cultured cardiomyocytes nonpredictive for a causative role of death receptors.

In an in vivo study of doxorubicin-treated rats, the CD95-inhibitory antibody NOK-2 reduced the number of TUNEL-positive myocardial nuclei and preserved heart function [22]. Efficiency of doxorubicin for the treatment of solid tumors might at least in part rely on cell death induction in endothelial cells [27]. Additionally, the CD95 system induced marked cell death in cardiac endothelial cells [14]; however, endothelial cell death by doxorubicin was shown to occur independently from the CD95 system [37].

In line with published results, our experiments showed certain inhibition of doxorubicin-induced cell death of cardiomyocytes by dexrazoxane [12], underlining the importance of iron-catalyzed radical formation for doxorubicin-induced cell death signaling in cardiomyocytes. As DILs were dispensable in this process, it remains to be determined which intracellular signaling proteins mediate formation of free radicals and depolarization of mitochondrial transmembrane potential in doxorubicin-induced cell death of cultured cardiomyocytes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Renata Zucic, Petra Berger, and Ursula Nägele for excellent technical help.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Wilhelm Sander Stiftung and Bettina-Bräu-Stiftung.

References

- 1.Arola OJ, Saraste A, Pulkki K, Kallajoki M, Parvinen M, Voipio-Pulkki LM. Acute doxorubicin cardiotoxicity involves cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergmann MW, Loser P, Dietz R, von Harsdorf R. Effect of NF-kappa B inhibition on TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis and downstream pathways in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1223. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonavita F, Stefanelli C, Giordano E, Columbaro M, Facchini A, Bonafe F, Caldera CM, Guaneri C. H9c2 cardiac myoblasts undergo apoptosis in a model of ischemia consisting of serum deprivation and hypoxia: inhibition by PMA. FEBS Lett. 2003;536:85. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chao W, Shen Y, Li L, Rosenzweig A. Importance of FADD signaling in serum-deprivation- and hypoxia-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Childs AC, Phaneuf SL, Dirks AJ, Phillips T, Leeuwenburgh C. Doxorubicin treatment in vivo causes cytochrome C release and cardiomyocyte apoptosis, as well as increased mitochondrial efficiency, superoxide dismutase activity, and Bcl-2:Bax ratio. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chinnaiyan AM, O’Rourke K, Tewari M, Dixit VM. FADD, a novel death domain-containing protein, interacts with the death domain of Fas and initiates apoptosis. Cell. 1995;81:505. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clementi ME, Giardina B, Di Stasio E, Mordente A, Misiti F. Doxorubicin-derived metabolites induce release of cytochrome C and inhibition of respiration on cardiac isolated mitochondria. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:2445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cusack BJ, Young SP, Driskell J, Olson RD. Doxorubicin and doxorubicinol pharmacokinetics and tissue concentrations following bolus injection and continuous infusion of doxorubicin in the rabbit. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1993;32:53. doi: 10.1007/BF00685876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friesen C, Herr I, Krammer PH, Debatin KM. Involvement of the CD95 (APO-1/Fas) receptor/ligand system in drug-induced apoptosis in leukemia cells. Nat Med. 1996;2:574. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friesen C, Fulda S, Debatin KM. Induction of CD95 ligand and apoptosis by doxorubicin is modulated by the redox state in chemosensitive- and drug-resistant tumor cells. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:471. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fulda S, Sieverts H, Friesen C, Herr I, Debatin KM. The CD95 (APO-1/Fas) system mediates drug-induced apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasinoff BB. The interaction of the cardioprotective agent ICRF-187 [+)-1,2- bis(3,5-dioxopiperazinyl-1-yL)propane); its hydrolysis product (ICRF-198); and other chelating agents with the Fe(III) and Cu(II) complexes of adriamycin. Agents Actions. 1989;26:378. doi: 10.1007/BF01967305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herr I, Debatin KM. Cellular stress response and apoptosis in cancer therapy. Blood. 2001;98:2603. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.9.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janin A, Deschaumes C, Daneshpouy M, Estaquier J, Micic-Polianski J, Rajagopalan-Levasseur P, Akarid K, Mounier N, Gluckman E, Socie G, Ameisen JC. CD95 engagement induces disseminated endothelial cell apoptosis in vivo: immunopathologic implications. Blood. 2002;99:2940. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.8.2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jemmerson R, Liu J, Hausauer D, Lam KP, Mondino A, Nelson RD. A conformational change in cytochrome c of apoptotic and necrotic cells is detected by monoclonal antibody binding and mimicked by association of the native antigen with synthetic phospholipid vesicles. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3599. doi: 10.1021/bi9809268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeremias I, Herr I, Boehler T, Debatin KM. TRAIL/Apo-2-Ligand induced apoptosis in T-cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:143. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199801)28:01<143::AID-IMMU143>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeremias I, Kupatt C, Martin-Villalba A, Habazettl H, Schenkel J, Boekstegers P, Debatin KM. Involvement of CD95/Apo1/Fas in cell death after myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2000;102:915. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.8.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kayagaki N, Kawasaki A, Ebata T, Ohmoto H, Ikeda S, Inoue S, Yoshino K, Okumura K, Yagita H. Metalloproteinase-mediated release of human Fas ligand. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1777. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keefe DL. Anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:2. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2001.26431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar D, Kirshenbaum LA, Li T, Danelisen I, Singal PK. Apoptosis in adriamycin cardiomyopathy and its modulation by probucol. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2001;3:135. doi: 10.1089/152308601750100641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lebrecht D, Setzer B, Ketelsen UP, Haberstroh J, Walker UA. Time-dependent and tissue-specific accumulation of mtDNA and respiratory chain defects in chronic doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2003;108:2423. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093196.59829.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura T, Ueda Y, Juan Y, Katsuda S, Takahashi H, Koh E. Fas-mediated apoptosis in adriamycin-induced cardiomyopathy in rats: in vivo study. Circulation. 2000;102:572. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newton K, Strasser A. Ionizing radiation and chemotherapeutic drugs induce apoptosis in lymphocytes in the absence of Fas or FADD/MORT1 signaling: implications for cancer therapy. J Exp Med. 2000;191:195. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicoletti I, Migliorati G, Pagliacci MC, Grignani F, Riccardi C. A rapid and simple method for measuring thymocyte apoptosis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1991;139:271. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90198-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nitobe J, Yamaguchi S, Okuyama M, Nozaki N, Sata M, Miyamoto T, Takeishi Y, Kubota I, Tomoike H. Reactive oxygen species regulate FLICE inhibitory protein (FLIP) and susceptibility to Fas-mediated apoptosis in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:119. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00646-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olson RD, Mushlin PS. Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity: analysis of prevailing hypotheses. FASEB J. 1990;4:3076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pastorino F, Brignole C, Marimpietri D, Cilli M, Gambini C, Ribatti D, Longhi R, Allen TM, Corti A, Ponzoni M. Vascular damage and anti-angiogenic effects of tumor vessel-targeted liposomal chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petak I, Houghton JA. Shared pathways: death receptors and cytotoxic drugs in cancer therapy. Pathol Oncol Res. 2001;7:95. doi: 10.1007/BF03032574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scaffidi C, Fulda S, Srinivasan A, Friesen C, Li F, Tomaselli KJ, Debatin KM, Krammer PH, Peter ME. Two CD95 (APO-1/Fas) signaling pathways. EMBO J. 1998;17:1675. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Springhorn JP, Claycomb WC. Preproenkephalin mRNA expression in developing rat heart and in cultured ventricular cardiac muscle cells. Biochem J. 1989;258:73. doi: 10.1042/bj2580073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swain SM, Vici P. The current and future role of dexrazoxane as a cardioprotectant in anthracycline treatment: expert panel review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:1. doi: 10.1007/s00432-003-0498-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Um HD, Orenstein JM, Wahl SM. Fas mediates apoptosis in human monocytes by a reactive oxygen intermediate dependent pathway. J Immunol. 1996;156:3469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walczak H, Krammer PH. The CD95 (APO-1/Fas) and the TRAIL (APO-2L) apoptosis systems. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256:58. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace KB. Doxorubicin-induced cardiac mitochondrionopathy. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;93:105. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2003.930301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L, Ma W, Markovich R, Lee WL, Wang PH. Insulin-like growth factor I modulates induction of apoptotic signaling in H9C2 cardiac muscle cells. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1354. doi: 10.1210/en.139.3.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webb J. Enzyme and metabolic inhibitors. New York: Academic; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu S, Ko YS, Teng MS, Ko YL, Hsu LA, Hsueh C, Chou YY, Liew CC, Lee YS. Adriamycin-induced cardiomyocyte and endothelial cell apoptosis: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:1595. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamaoka M, Yamaguchi S, Suzuki T, Okuyama M, Nitobe J, Nakamura N, Mitsui Y, Tomoike H. Apoptosis in rat cardiac myocytes induced by Fas ligand: priming for Fas-mediated apoptosis with doxorubicin. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:881. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]