Abstract

Background: Neuroblastoma is the most common solid extracranial tumor in childhood, still with poor survival rates for metastatic disease. Neuroblastoma cells are of neuroectodermal origin and express a number of cancer germline (CG) antigens. These CG antigens may represent a potential target for immunotherapy such as peptide-based vaccination strategies. Objective: The purpose of this study was to analyze the presence of MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3/A6, and NY-ESO-1 on an mRNA and protein level and to determine the expression of MHC class I and MHC class II antigens within the same tumor specimens. Methods: A total of 68 tumors were available for RT-PCR, and 19/68 tumors were available for immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3/A6, and NY-ESO-1. In parallel, the same tumors were stained with a panel of antibodies for MHC class I and MHC class II molecules. Results: Screening of 68 tumor specimens by RT-PCR revealed expression of MAGE-A1 in 44%, MAGE-A3/A6 in 21%, and NY-ESO-1 in 28% of cases. Immunohistochemistry for CG antigens of selected tumors showed good agreement between protein and gene expression. However, staining revealed a heterogeneous expression of CG antigens. None of the selected tumors showed MHC class I or MHC class II expression. Conclusions: mRNA expression of MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3/A6, and NY-ESO-1 is congruent with the protein expression as determined by immunohistochemistry. The heterogeneous CG-antigen expression and the lack of MHC class I and II molecules may have implications for T-cell–mediated immunotherapy in neuroblastoma.

Keywords: Cancer germline antigens, Immunotherapy, MAGE, MHC expression, Neuroblastoma, NY-ESO-1

Introduction

The presence of tumor-associated antigens is critical for tumor-specific T-cell–mediated immunotherapy [11]. While inducing an epitope-specific T-cell response is feasible due to improved vaccination strategies like peptide-based or dendritic cell–based protocols, the clinical efficiency of such protocols so far has been limited in most studies [18, 28, 34]. Moreover, in children suffering from cancer, there is very little experience with vaccination strategies as a form of immunotherapy [14, 31].

Neuroblastoma, a tumor of neuroectodermal origin, is one of the most common solid tumor entities in childhood. Its clinical picture is heterogeneous even in metastatic disease. While stage 4S tumors usually undergo spontaneous regression and have an excellent prognosis, stage 4 tumors remain mostly resistant to therapy and are therefore correlated with a poor prognosis (overall survival of about 44%) [2, 13]. On an mRNA level, it has been demonstrated that neuroblastoma expresses several cancer germline (CG) antigens such as those of the MAGE gene family [8, 17, 36]. The expression of CG antigens would allow a protein- or peptide-specific immunotherapy. Therefore neuroblastoma might be a candidate for vaccination trials. Recruitment of patients undergoing peptide-based immunotherapy is mostly based on the mRNA expression of the appropriate CG antigen. However, expression of tumor-associated antigens on an mRNA level may differ from their expression on a protein level [19, 21, 22]. In the present study, we parallel-analyzed antigen presence on a protein and an mRNA level to identify possible candidates for immunotherapy.

In vitro data are controversial regarding the susceptibility of neuroblastoma cells to T-cell–mediated lysis [27, 33], which may be explained by differences in the characteristics of T-cell lines, such as the avidity of the CTLs. Varying degrees of MHC class I expression of neuroblastoma cells or even lack of MHC class I expression can also result in a failure of T cells to lyse their targets. Therefore, assessment of MHC class I and MHC class II expression has a direct impact on the evaluation of cancer patients undergoing vaccination trials [12].

The present comprehensive analysis of CG-antigen gene and protein expression and MHC class I expression within the same tumor specimen may be helpful for the understanding of the potential success of clinical vaccination studies.

Methods

Study population

Snap-frozen tissue specimens were obtained from patients undergoing surgery for confirmation of the initial diagnosis of neuroblastoma. A total of 68 tumor specimens were examined for mRNA expression of CG-antigens. In 19/68 tumors, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks were also available for immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis. 17 of 19 FFPE specimens were analyzed by IHC for presence of MHC class I and MHC class II expression using corresponding snap-frozen specimens (two samples could not be evaluated due to extensive necrosis of the tumor sample). The neuroblastoma stage of the 68 tumors was as follows: stages 1–3: 22 patients, stage 4: 44 patients, stage 4S: 2 patients.

RT-PCR for MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3/A6, and NY-ESO-1

For molecular analysis, only tissue blocks containing >60% vital tumor tissue as determined by an H&E stained section were chosen. Frozen sections of 25–50 mg tumor were added to Trisol reagent or lysis buffer (Qiagen RNeasy kit) immediately, and RNA was extracted using a modified manufacturer’s protocol. RT-PCR was performed as published previously with minor modifications [10, 36]. Briefly, reverse transcription was performed at 37° for 1 h with oligo(dT) 18 primers, superscript II (Gibco/BRL) using 2 μg sample RNA under standard conditions. Amplification of MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3/A6, and NY-ESO-1 was carried out with 3 μl cDNA each in a mixture of 10 mM Tris/HCl buffer, pH 9.0, 50 mM KCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTPs, 1.2 U TAQ, and 12.5 pmol of each primer and water to an end volume of 25 μl.

As reference and positive control, RNA from SK-MEL-37 melanoma cells (for NY-ESO-1) and MZ-2-MEL melanoma cells (MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3/A6) was used. β-Actin was used to assess the integrity of the RNA and as control for the RT-PCR procedure.

The primers and PCR product lengths were as follows: MAGE-A1: 5′-CGG-CCG-AAG-GAA-CCT-GAC-CCA-G-3′; 5′-GCT-GGA-ACC-CTC-ACT-GGG-TTG-CC-3′ (sense, antisense), product 421 bp; MAGE-A3/A6: forward: 5′-TGG-AGG-ACC-AGA-GGC-CCC-C-3′; reverse: 5′-GGA-CGA-TTA-TCA-GGA-GGC-CTG-C-3′; product: 725 bp; NY-ESO-1: forward: 5′-GGC-TGA-ATG-GAT-GCT-GCA-GAT-3′; reverse: 5′-CAT-GTA-AGC-CGT-CCT-CCT-CCA-G-3′; product: 451 bp; β-actin: forward: 5′-GTC-CTC-TCC-CAA-GTC-CAC-ACA-3′; reverse: 5′-CTG-GTC-TCA-AGT-CAG-TGT-ACA-GGT-AA-3′. Amplification was performed in a Primus thermo block (MWG Biotech) after an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 3 min and followed by a final extension period of 7 min at 72°C as follows: MAGE-A1: 1 min at 94°C, 3 min at 72°C, 40 cycles; MAGE-A3/A6: 1 min at 94°C, 4 min at 72°C, 40 cycles; NY-ESO-1: 1 min at 94°C, 90 s at 64°C, 2 min at 72°C, 40 cycles; β-actin: 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 62°C, 1 min at 72°C, 20 cycles. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis in an agarose gel containing ethidium bromide as a stain. Bands of the corresponding size visible under UV light were interpreted as positive.

Immunhistochemistry for CG-antigens

The following monoclonal antibodies were used for the IHC detection of CG antigens: mAb MA454 to MAGE-A1 [19], mAb M3H67 to MAGE-A3/6 [24] (A.A. Jungbluth, in preparation), mAb 57B to MAGE-A4 [19, 26], mAb CT7-33 to CT7/MAGE-C1 [22] and mAb ES121 to NY-ESO-1 [21]. Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously [21]. Briefly, slides were deparaffinized and primary antibodies were applied overnight at 4°C after application of heat-induced antigen retrieval (AGR) technique. DAKO hipH-solution and EDTA (1 mmol, pH 8.0) was used as the AGR solution for mAbs MA454 and ES121, respectively, and citrate (10 mmol, pH 6.0) was used for mAbs CT7-33 and 57B. A biotinylated horse antimouse antibody (1:200; Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA) was used as secondary reagent followed by an avidin–biotin system (ABC-elite kit; Vector) for mAbs MA454, M3H67, CT7-33, and 57B. DAKO Envision plus was employed for the detection of mAb ES121. As chromogen, 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB, Biogenex, San Ramon, CA, USA) was used. The following antibody concentrations were used: MA454 1.0 μg/ml, M3H67 1.0 μg/ml, ES121 2.5 μg/ml, 57B 0.25 μg/ml, CT7-33 0.5 μg/ml. Testis with intact spermatogenesis served as positive control tissue. The extent of tumor staining was estimated on the basis of tumor cells stained and graded as follows: focal, approximately <5%; +, 5–25%; ++, >25–50%; +++, >50–75%; and ++++, >75%. The tumor specimens were rated by two independent pathologists without knowledge of the PCR data.

Immunhistochemistry for MHC class I and MHC class II expression

For the IHC analysis of MHC class I and class II molecules, snap-frozen tumor specimens corresponding to the FFPE tumor samples employed for examination of CG protein expression, the following mAbs were used [3]: mAb GRH1 recognizing free and HLA class I heavy chain–associated β2-microglobulin (β2-m) chain; mAb W6/32 to the HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C heavy chain/β2-m complex and mAb HC-10 reactive with the free heavy chain of HLA-B and HLA-C molecules, mAbs 1082C5 and A131 to the HLA-A locus, mAbs Q6/64 and H-2-89.1 to the HLA-B-locus and mAb GRB1 to HLA-DR. Analysis was performed without knowledge of CG-antigen expression.

Statistics

To determine the degree of agreement between the results of PCR and IHC, κ statistics were calculated [6].

Results

mRNA expression of MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3, and NY-ESO-1 in neuroblastoma

Samples from 68 different neuroblastoma patients were analyzed by RT-PCR. The PCR products produced gel bands with varying intensities. In cases with faint amplicon bands, the RT-PCR reaction including the preceding RNA extraction was repeated. These cases were scored positive, if the second reaction also generated a faint band. Expression of MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3/A6, and NY-ESO-1 was seen in 30/68 (44%), 14/68 (21%), and 19/68 (28%), respectively. Coexpression of MAGE-A1 and MAGE-A3/A6 was seen in 11/68 (16%) specimens. Coexpression of NY-ESO-1 with MAGE-A1 or MAGE-A3/A6 was present in 12/68 (18%) and 8/68 (12%) of specimens, respectively. Five cases (7%) were positive for all three antigens.

Immunhistochemical staining of CG antigens

Paraffin blocks of 19 tumors were available for the IHC analysis of CG antigens with mAbs MA454, M3H67, CT7-33, 57B, and ES121. The result of the IHC analysis is listed in Table 1. The staining of all five antibodies was restricted to tumor cells and no immunoreactivity was present in nontumorous tissue components such as surrounding Schwannian-stroma cells or blood vessels. Immunostaining was almost exclusively cytoplasmic with mAbs MA454, 57B, and ES121, while additional nuclear staining was present to varying degrees with mAbs M3H67 and CT7-33. The staining pattern was mostly heterogeneous, i.e., immunoreactivity was observed solely in single tumor cells or smaller tumor areas while few tumors showed immunolabelling of almost all tumor cells (Fig. 1). Interestingly, staining with the mAb CT7-33 was positive in 15 of the 19 tumor specimens.

Table 1.

Tumor characteristics, gene and protein expression of CG antigens, and MHC class I and MHC class II expression of selected tumors. N-MYC copies: all tumors showed one copy except for tumor no. 12 with 20 copies and tumor no. 13 with 50 copies. Grading according to Hughes et al. [16]. ND Not determined, fc focal

| Patient no. | Stage | Grade | MAGE-A1 | MAGE-A3 | NY-ESO-1 | MAGE-A4 | CT7/MAGE-C1 | HLA class I | HLA class II | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | MA454 | PCR | M3H67 | PCR | ES121 | 57B | CT7-33 | |||||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | + | 4+ | − | 4+ | − | − | fc | − | − | − |

| 2 | 3 | 1a | + | Fc | − | fc | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3 | 3 | 1a | + | + | + | 3+ | + | +/fc | + | Fc | − | − |

| 4 | 4 | 2 | + | 4+ | + | 4+ | + | Fc | 2+ | 2+ | ND | ND |

| 5 | 1 | 2 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 6 | 1 | 2 | + | 2+ | + | 2+ | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 7 | 4 | 3 | + | Fc | + | 2+ | + | Fc | − | Fc | − | − |

| 8 | 1 | 2 | + | 3+ | + | Fc | − | − | − | Fc | ND | ND |

| 9 | 1 | 2 | + | 2+ | + | + | + | − | fc | Fc | − | − |

| 10 | 3 | 2 | + | 3+ | − | 4+ | + | 3+ | 4+ | 2+ | − | − |

| 11 | 3 | 3 | + | 4+ | + | 4+ | + | 4+ | 4+ | + | − | − |

| 12 | 4 | 3 | − | +/fc | + | +/fc | + | Fc | fc | + | − | − |

| 13 | 3 | 3 | + | 2+ | + | 2+ | − | − | fc | fc | − | − |

| 14 | 3 | 3 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | fc | − | − |

| 15 | 4 | 3 | + | Fc | + | 4+ | − | − | 2+ | fc | − | − |

| 16 | 4 | 2 | + | +/fc | − | 3+ | − | − | + | 2+ | − | − |

| 17 | 4 | 1b | − | − | − | 3+ | − | 4± (mixed) | + | + | − | − |

| 18 | 4 | 1b | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 19 | 1 | 3 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

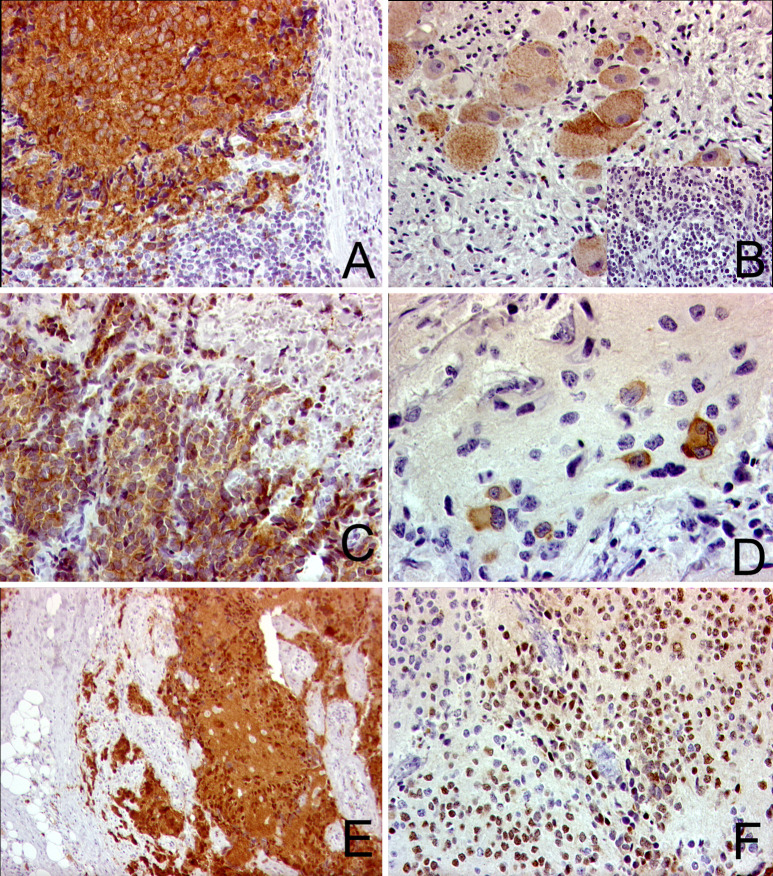

Fig. 1.

IHC for CG antigens. a, b Staining with mAb ES121 for NY-ESO-1: a patient no. 11, poorly differentiated neuroblastoma, 250-fold; b patient no. 17, ganglioneuroblastoma, immunoreactivity of mature and immature ganglion cells and no staining of the neuroblasts in the poorly differentiated areas (inlet), 400-fold. c, d Reactivity against mAbM454 for MAGE-A1: c patient no. 11, neuroblasts showing a strong staining intensity (4+), 250-fold; d patient no. 2, focal staining in differentiating neuroblasts, 400-fold. e, f Reactivity against mAb for M3H67 for MAGE-A3/A6: e patient no. 11, 4+, 250-fold; f patient no. 13, 2+, 250-fold.

The RT-PCR and IHC were mostly congruent (77% of all cases) (Table 2). The coefficient of agreement κ showed moderate agreement for MAGE-A1 (κ=0.477) and MAGE-A3 (κ=0.433), and good agreement for NY-ESO-1 (κ=0.774). Some discrepancies between RT-PCR and IHC data were observed: for MAGE-A1, 1/3 mRNA-negative tumors showed some immunoreactivity (+/focal). For NY-ESO-1, 1 of 12 mRNA-negative tumors showed positive tumor cells by IHC. Interestingly, this tumor showed a heterogeneous staining pattern confined to the differentiation stage of the neuroblasts with discrete areas of neuroblastic, clearly NY-ESO-1–negative cells, surrounded by more differentiated, strongly NY-ESO-1–positive cells (Fig. 1b). Since the number of positive cells in these samples was low, these discrepancies may be attributed to sample bias or the dilution of the specific mRNA below the threshold detectable by the RT-PCR.

Table 2.

Congruency between gene and protein expression of CG antigens (n=19)

| Immunhistochemistry | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Focal/+ | ++ | +++ | ++++ | |

| MAGE-A1 mRNA | |||||

| Positive (16) | 2 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Negative (3) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MAGE-A3/A6 mRNA | |||||

| Positive (11) | 0 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Negative (8) | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| NY-ESO-1 mRNA | |||||

| Positive (7) | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Negative (12) | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

For MAGE-A3/A6, 5/8 RT-PCR–negative cases were immunoreactive with mAb M3H67.

In a few cases, IHC-negative tumors were positive for mRNA expression (MAGE-A1, 2/16; NY-ESO-1, 2/7).

MHC class I and MHC class II expression in neuroblastoma

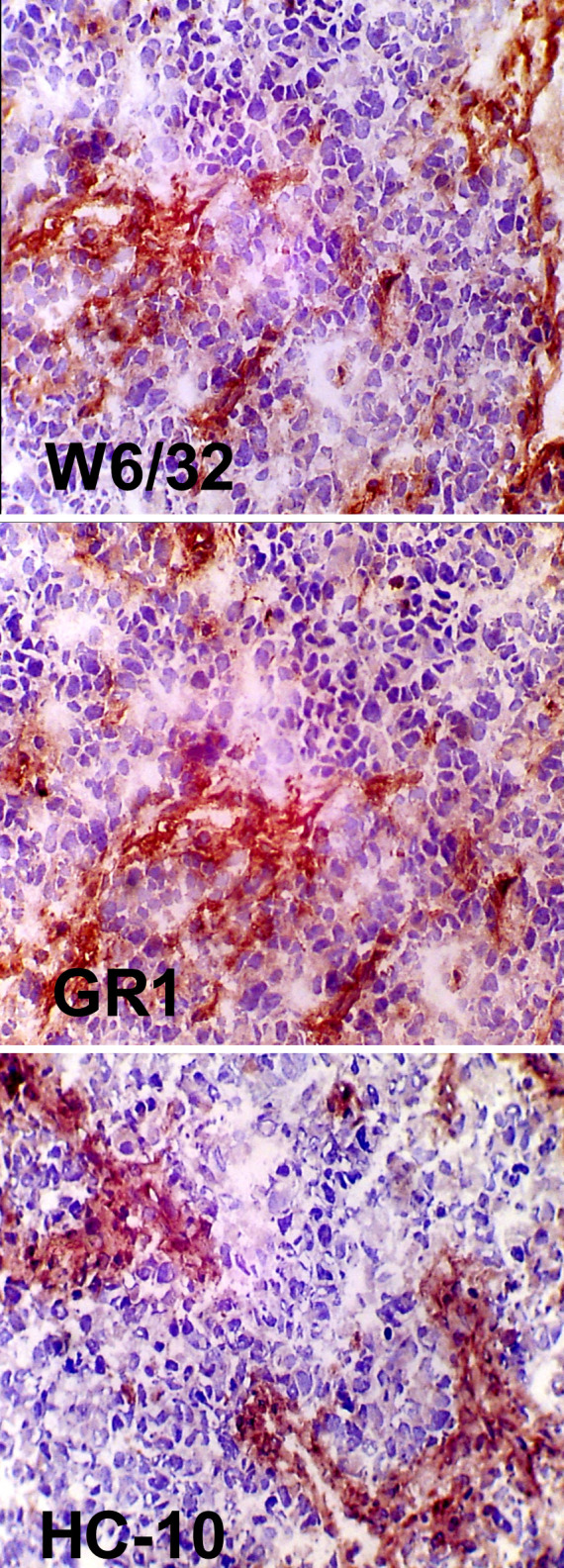

A total of 17 tumors were available for IHC analysis of MHC class I and MHC class II expression using the methodology and a panel of different monoclonal antibodies as described recently [3]. Our panel comprised mAbs to HLA-ABC loci, β2-m, and HLA-DR. The surrounding stromal cells served as internal positive control. None of the 17 tumors was immunopositive with any of our antibodies to MHC class I or MHC class II molecules (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Staining for MHC class I expression in neuroblastoma (patient no. 15). Top staining with mAbW6/32 for HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C expression; center mAb GRH1 against β2-m; bottom mAb HC-10 against the MHC heavy chain.

Discussion

Neuroblastoma is one of the most common solid tumors in childhood. Patients with stage 4 tumors have a poor prognosis with an overall survival rate of about 40% [2]. Immunotherapy employing tumor-associated antigens has been demonstrated to be immunologically effective in adult cancer patients. In some of these patients, clinical improvement or stabilization could be achieved [18, 28, 34].

Neuroblastoma cells express certain CG antigens that can serve as targets for a T-cell–mediated immunotherapy. In our study, the mRNA expression of MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3/A6, and NY-ESO-1 was detected in 44%, 21%, and 28% of the cases, respectively. Similar data were described previously: in a series of 98 tumors, Soling et al. [36] described the expression of MAGE-A1, MAGE-A3, and NY-ESO-1 in 66%, 33%, and 36%, respectively. Ishida et al. [17] demonstrated the expression of MAGE-A1 in 49% and MAGE-A3/A6 in 59% of a total of 41 neuroblastoma specimens. Corrias et al. [8] described the expression of MAGE-A1 in 16% and MAGE-A3/6 in 56% of 73 tumor samples. This variation between studies may be explained by different patient groups, but also by slightly different PCR conditions. However, the data confirm that CG antigens are expressed in about one third of the neuroblastoma specimens.

The selection of the tumor specimens was done with regard to the availability of the material and does not represent the general distribution of neuroblastoma according to stage. Consequently, a statistical correlation analysis with the stage or other pathological or clinical characteristics was not done.

Recruitment of patients undergoing peptide-based vaccination therapy is often based on the expression of the genes encoding a specific tumor-associated antigen as detected by RT-PCR. The immunodominant epitopes for these tumor-associated antigens are known for a variety of the most common HLA types, and the database is constantly growing, making a peptide-based approach feasible for a major group of patients. (B. Van den Eynde and P. van der Bruggen, T-cell–defined tumor antigens. Peptide database. http://CancerImmunity.org). However, mRNA expression data do not reveal the actual presence of the protein within a tumor. Heterogeneity of CG-antigen protein expression has been described for most tumors, while homogeneous antigen expression appears to be the exception [19–22]. This is also reflected in our series, where a broad variation of CG expression with focal staining of single cells in some, and homogeneous strong staining in other, tumor samples was present.

In a recent study of neuroblastoma patients, Rodolfo et al. [30] demonstrated naturally occurring humoral and T-cell responses against NY-ESO-1, while mRNA expression of NY-ESO-1 could be detected in 11 of 20 tumors, whereas in 18 of 22 tumors, IHC showed a homogeneous staining pattern. However, in our series the staining pattern was mostly heterogeneous, and homogeneously stained areas were only occasionally found. Rodolfo et al. [30] also demonstrated the immunogenicity of NY-ESO-1 expression in neuroblastoma, suggesting cross-priming by professional APCs as a way to induce an immune response in HLA-negative tumors. Furthermore, they showed T-cell–mediated NY-ESO-1–specific killing of a neuroblastoma cell line in a MHC class I–restricted manner. These findings might encourage further investigations concerning neuroblastoma as an immunogenic target.

The degree of MHC class I expression is crucial for specific lysis by CD8+ T cells [12, 29, 32]. Early work on neuroblastoma cell lines and primary tumor specimens revealed a low or undetectable expression of MHC class I and MHC class II molecules and/or β2-m, but expression can be induced by IFN-γ [25, 37, 41]. An inverse correlation between MHC class I expression and amplification or over-expression of the MYC-N protooncogene has been suggested [1, 39]. However, other authors did not see this inverse correlation between MYC-N amplification or expression with MHC class I expression [15] and suggest that low MHC class I expression is due to the differentiation stage from the neural crest [7]. Additional factors possibly influencing MHC class I regulation in neuroblastoma are 1p deletion, DNA hypomethylation, and alterations of the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) [4, 9]. In this study, a subset of tumors was coanalyzed for CG expression and for expression of MHC class I, MHC class II, and β2-m using a broad panel of antibodies. Neither of these MHC molecules could be detected in any of the tumor samples. Interestingly, only 2 of the 17 tumors examined for MHC expression showed MYC-N amplification, which does not support a direct correlation of MYC-N amplification with the loss of MHC class I expression. Further assays are underway to characterize the missing MHC class I expression in our series on a molecular level.

Due to the sensitivity of IHC-staining techniques, absence of MHC class I expression by IHC does not necessarily exclude T- cell recognition of a particular antigen via limited numbers of MHC class I molecules, below the detection level of IHC. It has been shown that very few MHC class I molecules per cell (between 1 and 200) can be sufficient for tumor cell lysis by specific T cells under ideal conditions [5, 23, 38]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated, that neuroblastoma cell lines can be lysed by MYC-N–specific T cells, even without prior IFN-γ treatment to induce MHC class I up-regulation [33]. Strategies to up-regulate the MHC class I expression in neuroblastoma using modulating chemotherapeutic reagents have been described in vitro [35, 40], and the combination with vaccination strategies should be considered to improve the vaccination efficacy.

In conclusion, analysis of MHC class I, MHC class II, and CG expression by immunohistochemistry can help to select suitable candidates for immunotherapy and is useful for the design and the evaluation of vaccination trials. The comparison of different aspects that are crucial for immunotherapy, in the same tumor specimens, provides new insights into the immunogenicity of neuroblastoma.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ulla Schlütter for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported in part by the Kinderkrebs-Neuroblastomforschung e.V, Germany.

References

- 1.Bernards R, Dessain SK, Weinberg RA. N-myc amplification causes down-modulation of MHC class I antigen expression in neuroblastoma. Cell. 1986;47:667–674. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90509-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berthold F, Hero B, Kremens B, Handgretinger R, Henze G, Schilling FH, Schrappe M, Simon T, Spix C. Long-term results and risk profiles of patients in five consecutive trials (1979–1997) with stage 4 neuroblastoma over 1 year of age. Cancer Lett. 2003;197:11–17. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(03)00076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabrera T, Lopez-Nevot MA, Gaforio JJ, Ruiz-Cabello F, Garrido F. Analysis of HLA expression in human tumor tissues. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2003;52:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0332-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng NC, Beitsma M, Chan A, Op den Camp I, Westerveld A, Pronk J, Versteeg R. Lack of class I HLA expression in neuroblastoma is associated with high N-myc expression and hypomethylation due to loss of the MEMO-1 locus. Oncogene. 1996;13:1737–1744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christinck ER, Luscher MA, Barber BH, Williams DB. Peptide binding to class I MHC on living cells and quantitation of complexes required for CTL lysis. Nature. 1991;352:67–70. doi: 10.1038/352067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper MJ, Hutchins GM, Mennie RJ, Israel MA. Beta 2-microglobulin expression in human embryonal neuroblastoma reflects its developmental regulation. Cancer Res. 1990;50:3694–3700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corrias MV, Scaruffi P, Occhino M, De Bernardi B, Tonini GP, Pistoia V. Expression of MAGE-1, MAGE-3 and MART-1 genes in neuroblastoma. Int J Cancer. 1996;69:403–407. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961021)69:5<403::AID-IJC9>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corrias MV, Occhino M, Croce M, De Ambrosis A, Pistillo MP, Bocca P, Pistoia V, Ferrini S. Lack of HLA-class I antigens in human neuroblastoma cells: analysis of its relationship to TAP and tapasin expression. Tissue Antigens. 2001;57:110–117. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.057002110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Plaen E, Arden K, Traversari C, Gaforio JJ, Szikora JP, De Smet C, Brasseur F, van der Bruggen P, Lethe B, Lurquin C, et al. Structure, chromosomal localization, and expression of 12 genes of the MAGE family. Immunogenetics. 1994;40:360–369. doi: 10.1007/BF01246677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foss FM. Immunologic mechanisms of antitumor activity. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:5–11. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.34070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrido F, Algarra I. MHC antigens and tumor escape from immune surveillance. Adv Cancer Res. 2001;83:117–158. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(01)83005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Coleman MP, Ries LA, Berrino F. Childhood cancer survival in Europe and the United States. Cancer. 2002;95:1767–1772. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geiger JD, Hutchinson RJ, Hohenkirk LF, McKenna EA, Yanik GA, Levine JE, Chang AE, Braun TM, Mule JJ. Vaccination of pediatric solid tumor patients with tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells can expand specific T cells and mediate tumor regression. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8513–8519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross N, Beck D, Favre S. In vitro modulation and relationship between N-myc and HLA class I RNA steady-state levels in human neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7532–7536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes M, Marsden HB, Palmer MK. Histologic patterns of neuroblastoma related to prognosis and clinical staging. Cancer. 1974;34:1706–1711. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197411)34:5<1706::aid-cncr2820340519>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishida H, Matsumura T, Salgaller ML, Ohmizono Y, Kadono Y, Sawada T. MAGE-1 and MAGE-3 or −6 expression in neuroblastoma-related pediatric solid tumors. Int J Cancer. 1996;69:375–380. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961021)69:5<375::AID-IJC4>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jager E, Hohn H, Necker A, Forster R, Karbach J, Freitag K, Neukirch C, Castelli C, Salter RD, Knuth A, et al. Peptide-specific CD8+ T-cell evolution in vivo: response to peptide vaccination with Melan-A/MART-1. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:376–388. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jungbluth AA, Busam KJ, Kolb D, Iversen K, Coplan K, Chen YT, Spagnoli GC, Old LJ. Expression of MAGE-antigens in normal tissues and cancer. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:460–465. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000215)85:4<460::AID-IJC3>3.3.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jungbluth AA, Antonescu CR, Busam KJ, Iversen K, Kolb D, Coplan K, Chen YT, Stockert E, Ladanyi M, Old LJ. Monophasic and biphasic synovial sarcomas abundantly express cancer/testis antigen NY-ESO-1 but not MAGE-A1 or CT7. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:252–256. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jungbluth AA, Chen YT, Stockert E, Busam KJ, Kolb D, Iversen K, Coplan K, Williamson B, Altorki N, Old LJ. Immunohistochemical analysis of NY-ESO-1 antigen expression in normal and malignant human tissues. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:856–860. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jungbluth AA, Chen YT, Busam KJ, Coplan K, Kolb D, Iversen K, Williamson B, Van Landeghem FK, Stockert E, Old LJ. CT7 (MAGE-C1) antigen expression in normal and neoplastic tissues. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:839–845. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kageyama S, Tsomides TJ, Sykulev Y, Eisen HN. Variations in the number of peptide-MHC class I complexes required to activate cytotoxic T cell responses. J Immunol. 1995;154:567–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kocher T, Schultz-Thater E, Gudat F, Schaefer C, Casorati G, Juretic A, Willimann T, Harder F, Heberer M, Spagnoli GC. Identification and intracellular location of MAGE-3 gene product. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2236–2239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lampson LA, Whelan JP, Fisher CA. HLA-A,B,C and beta 2-microglobulin are expressed weakly by human cells of neuronal origin, but can be induced in neuroblastoma cell lines by interferon. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1985;175:379–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landry C, Brasseur F, Spagnoli GC, Marbaix E, Boon T, Coulie P, Godelaine D. Monoclonal antibody 57B stains tumor tissues that express gene MAGE-A4. Int J Cancer. 2000;86:835–841. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000615)86:6<835::AID-IJC12>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Main EK, Monos DS, Lampson LA. IFN-treated neuroblastoma cell lines remain resistant to T cell-mediated allo-killing, and susceptible to non-MHC-restricted cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 1988;141:2943–2950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paczesny S, Banchereau J, Wittkowski KM, Saracino G, Fay J, Palucka AK. Expansion of melanoma-specific cytolytic CD8+ T cell precursors in patients with metastatic melanoma vaccinated with CD34+ progenitor-derived dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1503–1511. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rivoltini L, Barracchini KC, Viggiano V, Kawakami Y, Smith A, Mixon A, Restifo NP, Topalian SL, Simonis TB, Rosenberg SA, et al. Quantitative correlation between HLA class I allele expression and recognition of melanoma cells by antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3149–3157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodolfo M, Luksch R, Stockert E, Chen YT, Collini P, Ranzani T, Lombardo C, Dalerba P, Rivoltini L, Arienti F, et al. Antigen-specific immunity in neuroblastoma patients: antibody and T-cell recognition of NY-ESO-1 tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6948–6955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rousseau RF, Haight AE, Hirschmann-Jax C, Yvon ES, Rill DR, Mei Z, Smith SC, Inman S, Cooper K, Alcoser P, et al. Local and systemic effects of an allogeneic tumor cell vaccine combining transgenic human lymphotactin with interleukin-2 in patients with advanced or refractory neuroblastoma. Blood. 2003;101:1718–1726. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruiz-Cabello F, Cabrera T, Lopez-Nevot MA, Garrido F. Impaired surface antigen presentation in tumors: implications for T cell-based immunotherapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:15–24. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarkar AK, Nuchtern JG. Lysis of MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma cells by MYCN peptide-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1908–1913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuler-Thurner B, Dieckmann D, Keikavoussi P, Bender A, Maczek C, Jonuleit H, Roder C, Haendle I, Leisgang W, Dunbar R, et al. Mage-3 and influenza-matrix peptide-specific cytotoxic T cells are inducible in terminal stage HLA-A2.1+ melanoma patients by mature monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:3492–3496. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slingluff CL. Targeting unique tumor antigens and modulating the cytokine environment may improve immunotherapy for tumors with immune escape mechanisms. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1999;48:371–373. doi: 10.1007/s002620050588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soling A, Schurr P, Berthold F. Expression and clinical relevance of NY-ESO-1, MAGE-1 and MAGE-3 in neuroblastoma. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:2205–2209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sugimoto T, Horii Y, Hino T, Kemshead JT, Kuroda H, Sawada T, Morioka H, Imanishi J, Inoko H. Differential susceptibility of HLA class II antigens induced by gamma-interferon in human neuroblastoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1989;49:1824–1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sykulev Y, Joo M, Vturina I, Tsomides TJ, Eisen HN. Evidence that a single peptide-MHC complex on a target cell can elicit a cytolytic T cell response. Immunity. 1996;4:565–571. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van’t Veer LJ, Beijersbergen RL, Bernards R. N-myc suppresses major histocompatibility complex class I gene expression through down-regulation of the p50 subunit of NF-kappa B. Embo J. 1993;12:195–200. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05645.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Voigt A, Hartmann P, Zintl F. Differentiation, proliferation and adhesion of human neuroblastoma cells after treatment with retinoic acid. Cell Adhes Commun. 2000;7:423–440. doi: 10.3109/15419060009109023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whelan JP, Chatten J, Lampson LA. HLA class I and beta 2-microglobulin expression in frozen and formaldehyde-fixed paraffin sections of neuroblastoma tumors. Cancer Res. 1985;45:5976–5983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]