Abstract

This study used the most recent national data from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) to provide updated estimates of the prevalence of active epilepsy (self-reported doctor-diagnosed epilepsy, currently under treatment with antiseizure medicines or had at least 1 seizure in the past 12 months, or both) and inactive epilepsy (self-reported doctor-diagnosed history of epilepsy, not under treatment with antiseizure medicines and with no seizures in the past 12 months) overall and by sex, age groups, race/ethnicity, education level, and health insurance status. In 2021, 1.1% of U. S. adults, (approximately 2,865,000 adults) reported active epilepsy; 0.6% (approximately 1,637,000 adults) reported inactive epilepsy. The prevalence of active epilepsy and inactive epilepsy did not differ by age or sex. Active and inactive epilepsy prevalence differed by educational level. Weighted population estimates are reported for each subgroup (e.g., women; non-Hispanic Blacks) for program or policy development. Although active epilepsy prevalence has remained relatively stable over the past decade, this study shows that more than half of U.S. adults with active epilepsy have ≤high school diploma/GED, which can inform the development and implementation of interventions. Additional monitoring is necessary to examine population trends in active prevalence overall and in subgroups.

Keywords: Epilepsy prevalence, Educational attainment, Education, National Health Interview Survey, Population survey

1. Introduction

Previous studies based on 2010, 2013, 2015, and 2017 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data indicated that the median active epilepsy prevalence among community-dwelling U.S. adults is 1.1% [1–5]. Active epilepsy prevalence among U.S. community-dwelling adults significantly increased in 2015 compared with 2013 (1.2% vs. 0.9%)—an increase of about 724,000 adults—likely associated with factors such as the aging of the population or increased awareness, diagnosis, and reporting of epilepsy [2]. In 2017, CDC published national and state estimates of the numbers of adults and children with active epilepsy, reporting that in 2015, 1.2% of the U.S. population reported active epilepsy, representing about 470,000 children 0–17 years of age and 2.9 million adults [3]. Studies have used aggregated NHIS data to examine epilepsy burden in subgroups such as older adults, men, and women, racial/ethnic subgroups, by poverty status, and region [2,6]. This brief report provides updated national estimates of active epilepsy prevalence among U.S. adults overall and among select subgroups, along with weighted population estimates to guide program planning and policy development to improve epilepsy care and outcomes.

2. Methods

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is an annual, nationally representative cross-sectional household survey, which collects health-related data on civilian noninstitutionalized US residents [7] Interviews are typically conducted in respondents’ homes, but follow-ups to complete interviews may be conducted over the telephone. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, interviewing procedures were disrupted, and during 2021, 62.8% of the Sample Adult interviews were conducted at least partially by telephone [7]. Information about epilepsy status was compiled in the 2021 NHIS Sample Adult module, where one adult aged ≥18 years is randomly selected from a randomly selected household. The Sample Adult respondent answers survey questions for themselves unless a physical or mental impairment necessitates the assistance of a knowledgeable proxy. In 2021, 29,482 sample adults (50.9% final response rate) responded to the survey [7].

Three validated questions on epilepsy, included as CDC Epilepsy Program sponsored content, from the NHIS Sample Adult questionnaire were used [3,7]. Adults were classified with a history of epilepsy if they reported ever being told by a doctor or a health professional that they have epilepsy or a seizure disorder. Adults were classified with active epilepsy if they reported both a history of doctor-diagnosed epilepsy or seizure disorder and either taking epilepsy medications, having at least one seizure in the past 12 months or both. Inactive epilepsy was defined as adults who reported a history of epilepsy but were not taking medication for epilepsy and had not had a seizure in the past year [3].

Select demographic characteristics included age group (18–44, 45–64, or ≥65), sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic other), level of education (<high school graduate, high school graduate, some college or higher), and health insurance status. The latter was defined as insured (adults who had any health insurance at the time of the interview, including private health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, State Children’s Health Insurance Program [includes coverage for some adults], a state-sponsored health plan, other government programs, or military health plan [includes TRICARE, VA, CHAMP-VA]) or not insured.

All analyses were performed using SAS-callable SUDAAN, version 11.0.1 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) to account for the complex sample design and response sampling weights [7]. Prevalence estimates (except for age group) were age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. population using three age groups [8]. For assessment of differences, nonoverlapping 95% confidence intervals were considered statistically significant at the 0.05 level. Estimates met previous NHIS standards of reliability (i.e., relative standard error <30.0%; denominator sample size ≥50 persons) unless otherwise noted [9].

3. Results

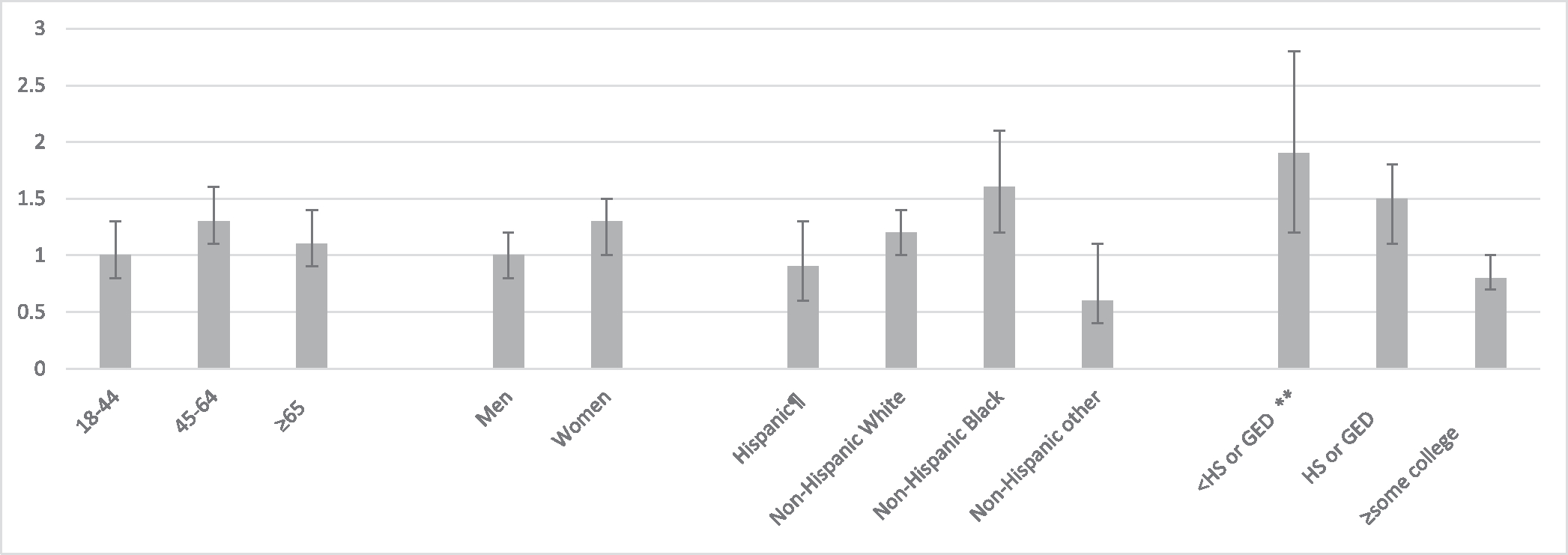

Among U.S. adults in 2021, active epilepsy prevalence was 1.1% (approximately 2,865,000 adults), and inactive epilepsy prevalence was 0.6% (approximately 1,637,000 adults) (Table 1.). Active epilepsy prevalence did not differ by age group or sex (Fig. 1). By race/ethnicity, active epilepsy prevalence ranged from 0.6% among non-Hispanic adults who identify with more than one race to 1.6% among non-Hispanic Black adults. Active epilepsy prevalence was significantly higher among those with less than a high school diploma or GED (1.9%) compared with adults with at least some college education (0.8%). About 2.7 million adults with active epilepsy had health insurance in 2021.

Table 1.

Number and age-adjusted* prevalence of active epilepsy, inactive epilepsy, and epilepsy history, by selected characteristics among adults—United States, 2021 National Health Interview Survey.

| Epilepsy Status† | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Active |

Inactive |

No history |

||||||

| Sample No. | Population estimate§ | % (95% CI) | Sample No. | Population estimate§ | % (95% CI) | Sample No. | Population estimate§ | % (95% CI) | |

|

| |||||||||

| Overall Total | 317 | 2,865,000 | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 192 | 1,637,000 | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 28,953 | 248,495,000 | 98.2 (98.0–98.4) |

| Age group (years) | |||||||||

| 18–44 | 98 | 1,161,000 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 67 | 716,000 | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 10,759 | 113,440,000 | 98.4 (98.1–98.6) |

| 45–64 | 126 | 1,061,000 | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 75 | 585,000 | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | 9,383 | 79,478,000 | 98.0 (97.6–98.3) |

| ≥65 | 93 | 643,000 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 50 | 336,000 | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | 8,811 | 55,578,000 | 98.3 (97.9–98.6) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Men | 131 | 1,214,000 | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 77 | 728,000 | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 13,162 | 120,252,000 | 98.4 (98.1–98.7) |

| Women | 186 | 1,651,000 | 1.3 (1.0–1.5) | 115 | 909,000 | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 15,789 | 128,227,000 | 98.1 (97.8–98.3) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Hispanic¶ | 41 | 382,000 | 0.9 (0.6–1.3)§§ | 18 | 168,000 | 0.4 (0.2–0.7)§§ | 4,020 | 42,263,000 | 98.7 (98.2–99.0)§§ |

| Non-Hispanic White | 203 | 1,870,000 | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 153 | 1,319,000 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 19,287 | 155,619,000 | 97.9 (97.7–98.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 56 | 473,000 | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) | 11†† | – | – | 3,092 | 29,020,000 | 98.1 (97.6–98.6) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 17 | 140,000 | 0.6 (0.4–1.1) | 10†† | – | – | 2,554 | 21,593,000 | 99.1 (98.6–99.4) |

| Educational level | |||||||||

| <HS or GED | 49 | 448,000 | 1.9 (1.2–2.8)§§ | 24 | 192,000 | 0.8 (0.5–1.2)§§ | 2,459 | 23,152,000 | 97.3 (96.3–98.1)§§ |

| HS or GED | 97 | 1,020,000 | 1.5 (1.1–1.8) | 65 | 671,000 | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 7,084 | 69,628,000 | 97.6 (97.1–98.0) |

| ≥some college | 168 | 1,366,000 | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 102 | 764,000 | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 19,263 | 154,174,000 | 98.7 (98.5–98.8) |

| Did not answer or Unknown | 3†† | – | – | 1†† | – | – | 147†† | – | – |

| Health insurance ** | |||||||||

| Yes | 305 | 2,735,000 | 1.2 (1.0–1.4)§§ | 181 | 1,534,000 | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 26,568 | 222,576,000 | 98.1 (97.9–98.3)§§ |

| No | 12†† | – | – | 11†† | – | – | 2,290 | 24,850,000 | 99.2 (98.8–99.5) |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; GED = General Educational Development; HS = high school.

Age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. projected population, aged ≥18 years, using three age groups: 18–44, 45–64, and ≥65 years. All prevalence estimates are age-adjusted except those for age groups, and overall (crude).

Doctor-diagnosed active epilepsy was defined as having a diagnosis of epilepsy and either taking medication, having had one or more seizures in the past year, or both; and inactive epilepsy was defined as having a diagnosis of epilepsy but not taking medication and having no seizures in the past year.

Number of respondents is unweighted; population estimate (rounded to 1,000 s) and percentage estimates are weighted.

Persons identified as Hispanic might be of any race. The four racial/ethnic categories are mutually exclusive.

Adults were considered uninsured if they did not have private health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), a state-sponsored health plan, other government programs, or a military health plan (includes TRICARE, VA, and CHAMP-VA) at the time of interview.

Estimates did not meet standards of reliability (i.e., relative standard error ≥30%).

P < 0.05, P-values were obtained using the Wald F test. Non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals were used to assess statistically significant differences between subgroups.

Fig. 1.

Age-adjusted* active epilepsy† prevalence by age group, sex, race/ethnicity, and educational status among adults—United States, 2021 National Health Interview Survey§ Abbreviations: GED = General Educational Development; HS = high school. *Age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. projected population aged ≥18 years using three age groups: 18–44, 45–64, and ≥65 years. All prevalence estimates are age-adjusted except those for age groups. †Active epilepsy was defined as self-reported doctor-diagnosed epilepsy and either taking medication, having had one or more seizures in the past year, or both. §Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. ¶Persons identified as Hispanic might be of any race. The four racial/ethnic categories are mutually exclusive. **Non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals were used to assess statistically significant differences between subgroups. Age-adjusted prevalence of active epilepsy was lower among adults with at least some college education compared with those with less education.

4. Discussion

Using the latest national data available from 2021, active epilepsy prevalence remained relatively stable at 1.1%. The overall weighted population estimate of active epilepsy prevalence was slightly less (2,865,000) than previously reported based on 2015 NHIS data (2,967,700). Differences might be accounted for by the revised 2019 NHIS methodology and additional methodological changes implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic [7,10]. Overall, findings suggest these survey changes had minimal impact on epilepsy estimates.

A previous study that examined annualized active epilepsy prevalence using 2013 and 2015 NHIS data by selected characteristics reported similar patterns by sex, age groups, race/ethnicity, and educational level [2]. Notably, however, our study reports that more than one-third million U.S. Hispanic adults and close to a half million U.S. non-Hispanic Black adults are estimated to have active epilepsy. Although active epilepsy prevalence among non-Hispanic adults who identify with more than one race met reliability standards, this finding should be interpreted with caution because of the small numerator and inclusion of multiple racial groups in this category limiting the generalizability of estimates to any non-Hispanic racial subgroup.

Our findings indicate that approximately half, or about 1.5 million, of U.S. adults with active epilepsy, have a high school diploma, or GED, or did not complete high school, indicating potential corresponding challenges associated with lower levels of education that underlie health inequities [11]. Some factors associated with academic underachievement among people with epilepsy include epilepsy etiology, cognitive functioning, comorbidity, parental educational level, and social status [12]. This underscores the need for interventions that incorporate personal health literacy and organizational health literacy tools to facilitate access to resources for people with epilepsy and their providers to improve health literacy equitably [13,14]. Consistent with previous reports, most adults with active epilepsy had health insurance [4].

Patterns for inactive epilepsy generally parallel those with active epilepsy and might reflect the educational and social challenges and limitations associated with specific epilepsy diagnoses and comorbidities relative to remission earlier in life [15].

This study has several limitations. First, active epilepsy prevalence may be underreported due to recall or reporting biases among survey respondents. Second, active epilepsy prevalence may be underreported due to the exclusion of adults in institutionalized settings (e.g., nursing homes, active military housing, prisons) not captured in the NHIS sample. Third, the relatively small sample size for some subgroups with active or inactive epilepsy (e.g., non-Hispanic Black adults with inactive epilepsy) yielded unreliable estimates. Fourth, the data are cross-sectional so no causal attributions on associations can be made. Future studies can compare estimates of epilepsy burden before and after the 2019 NHIS redesign to determine the appropriateness of aggregating data for subgroup analysis. Fifth, our estimate for active epilepsy prevalence differs from those of other high-income countries, but these differences may be accounted for by important differences in study methodologies and study assessment periods [16].

Although active epilepsy prevalence has remained relatively stable over the past decade, this study found differences in active epilepsy prevalence by educational status that can inform interventions. Additional studies with larger sample sizes may help to further assess disparities between as well as patterns within racial and ethnic populations or other sociodemographic groups that can inform public health and healthcare interventions. Continued monitoring is necessary to examine population trends in epilepsy prevalence overall and in subgroups.

Funding

This research was conducted by federal government employees and a federal government contractor. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- [1].Kobau R, Luo YH, Zack MM, Helmers S, Thurman DJ. Epilepsy in adults and access to care—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:909–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tian N, Boring M, Kobau R, Zack MM, Croft JB. Active epilepsy and seizure control in adults—United States, 2013 and 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:437–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zack MM, Kobau R. National and state estimates of the numbers of adults and children with active epilepsy—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:821–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tian N, Kobau R, Zack MM, Greenlund KJ. Barriers to and disparities in access to health care among adults aged ≥18 years with epilepsy — United States, 2015 and 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:697–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kobau R What have we learned from CDC-supported population surveillance and epidemiologic studies of epilepsy burden related to the IOM Epilepsy Across the Spectrum recommendations on surveillance. American Epilepsy Society Annual Conference; 2022. Dec 4; Nashville, TN. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sapkota S, Kobau R, Pastula DM, Zack MM. Close to 1 million US adults aged 55 years or older have active epilepsy-National Health Interview Survey, 2010, 2013, and 2015. Epilepsy Behav 2018;87:233–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey. 2021 Survey Description. Available from: https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2021/srvydesc-508.pdf [Accessed 30 January 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Age adjustment using the 2000 projected US population. Healthy People 2010 Stat Notes 2001;(20):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Klein RJ, Proctor SE, Boudreault MA, Turczyn KM. Healthy People 2010 criteria for data suppression. Healthy People 2020 Stat Notes 2002;(24):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey 2019 Questionnaire Redesign. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/2019_quest_redesign.htm [Accessed 9 January 2023].

- [11].Cohen AK, Syme SL. Education: a missed opportunity for public health intervention. Am J Public Health 2013;103:997–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jennum P, Debes NMM, Ibsen R, Kjellberg J. Long-term employment, education, and healthcare costs of childhood and adolescent onset of epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2021;114(Pt A):107256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hahn RA, Truman BI. Education improves public health and promotes health equity. Int J Health Serv 2015;45:657–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Health Resources & Services Administration. Health Literacy. Available from: https://www.hrsa.gov/about/organization/bureaus/ohe/health-literacy [Accessed 17 November 2022].

- [15].Geerts A, Brouwer O, van Donselaar C, Stroink H, Peters B, Peeters E, et al. Health perception and socioeconomic status following childhood-onset epilepsy: the Dutch study of epilepsy in childhood. Epilepsia 2011;52:2192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Epilepsy: a public health imperative. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/epilepsy-a-public-health-imperative [Accessed 3 March 2023]. [Google Scholar]