Abstract

Objective

The aim was to describe barriers to patient and family advisory council (PFAC) member engagement in research and strategies to support engagement in this context.

Methods

We formed a study team comprising patient advisors, researchers, physicians, and nurses. We then undertook a qualitative study using focus groups and interviews. We invited PFAC members, PFAC leaders, hospital leaders, and researchers from nine academic medical centers that are part of a hospital medicine research network to participate. All participants were asked a standard set of questions exploring the study question. We used content analysis to analyze data.

Results

Eighty PFAC members and other stakeholders (45 patient/caregiver members of PFACs, 12 PFAC leaders, 12 hospital leaders, 11 researchers) participated in eight focus and 19 individual interviews. We identified ten barriers to PFAC member engagement in research. Codes were organized into three categories: (1) individual PFAC member reluctance; (2) lack of skills and training; and (3) problems connecting with the right person at the right time. We identified ten strategies to support engagement. These were organized into four categories: (1) creating an environment where the PFAC members are making a genuine and unique contribution; (2) building community between PFAC members and researchers; (3) best practice activities for researchers to facilitate engagement; and (4) tools and training.

Conclusion

Barriers to engaging PFAC members in research include patients’ negative perceptions of research and researchers’ lack of training. Building community between PFAC members and researchers is a foundation for partnerships. There are shared training opportunities for PFAC members and researchers to build skills about research and research engagement.

1. Introduction

The evolution of patient-centered care and shared decision-making models has resulted in increasing efforts to partner with patients, family members, and caregivers to obtain their input and perspectives on healthcare [1]. One approach for healthcare organizations to form partnerships with patients and hear directly from them is through patient and family advisory councils (PFACs). PFACs are groups of patient partners (patients, family members, or caregivers) who meet regularly and share their experiences of care, or collective perspectives on a specific topic, with health service lines and hospital leaders [2]. A guiding principle of this engagement is that patient partners are ideally positioned to share their perspectives given that their perspectives are unique and given their lived experience through all stages of suffering, treatment, and healthcare delivery processes [3]. This direct and uncensored feedback is then used to inform health system improvement and guide organizational patient-centered care efforts.

A 2013 survey of 1457 acute care hospitals in the United States found that 38% had PFACs, with a more recent report by the Beryl Institute noting that the prevalence of PFACs has increased to 55% [4, 5]. PFACs are operationalized depending on the healthcare organization needs—they can be organization-wide, site specific (e.g., for multi-site hospital systems), disease specific (e.g., diabetes), service line specific (e.g., internal medicine), or subgroup specific (e.g., LGBTQ) [6-8]. Examples of activities PFAC members are requested to be involved with include quality improvement, patient safety, and operational initiatives such as fall prevention, hospital signage redesign, assessing patient furniture for patient rooms, clinician–patient communication, assessment of patient-facing educational materials, development of patient portals, and redesigning bedside rounds [2, 6, 8-10].

PFACs also provide a potential opportunity for research engagement, although this process is not well described. Patient partner engagement in research has gained momentum due to mandates by funding agencies and journal editors as well as an acknowledgement of the moral imperative to place patients at the center of all research activities [11-13]. A recent commentary, co-authored by a patient, described the process of patient engagement in research as ensuring that a human face of the research topic is represented within all research activities [14]. The benefits of patient–researcher partnerships are numerous and include greater relevance of research questions and outcome measures, more patient-centered and culturally appropriate methods, increased recruitment and retention, and increased translation, dissemination, and uptake of results [12, 14]. There is increasing acceptance that engaging and collaborating with patient partners leads to better quality research [12, 14].

Patient partner engagement in research is feasible, and awareness is growing [15]. A number of publications describe when in a research study’s timeline patients can successfully contributed their perspectives [16, 17]. General frameworks that describe overarching research engagement principles have also been developed to help guide this process [15, 18]. This includes one framework that focuses specifically on patient partners who are members of PFACs [19]. However, as PFACs’ primary function is not typically related to research, the feasibility of this approach to engaging PFAC members is unclear. Understanding how researchers can effectively partner with PFAC members to harness their experiences and expertise and to inform research continues to evolve. Therefore, the aims of this study were to describe the challenges and barriers to PFAC member engagement in research and to explore opportunities to support the research engagement process in this setting.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Oversight

We conducted a qualitative study using focus groups and interviews between February and April 2017. This study was reviewed and approved by the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), Brigham & Women’s Hospital (BWH), and Christiana Care Health System (CCHS) Committees on Human Research.

2.2. Patient Stakeholder Engagement

Patient partners (CH, GS, JB, and MC) are collaborators and part of the research team for this study. They have been involved in all stages of the study, including development, implementation, data analysis, and dissemination.

2.3. Setting and Participants

The study took place within the Hospital Medicine Re-Engineering Network (HOMERuN), a research collaborative that facilitates and conducts multi-center research to improve the outcomes of patients with acute illnesses [20]. HOMERuN represents 14 academic and community-based medical centers across nine states in the USA and includes an inter-professional team of clinicians and researchers. All sites have access to patient partners through existing institutional PFACs. Using purposive sampling [21], we asked site leads at each HOMERuN medical center to identify and invite via email PFAC leaders, hospital leaders, and researchers who all had previous experience in patient engagement to participate. We then invited PFAC members (patients, family members, or caregivers) from four HOMERuN sites (UCSF, BWH, CCHS, and the University of Pennsylvania) to participate in a focus group. These four sites were chosen because of the feasibility of being able to conduct in-person focus groups. We provided a $25 gift card to PFAC members who participated in focus groups.

2.4. Data Collection

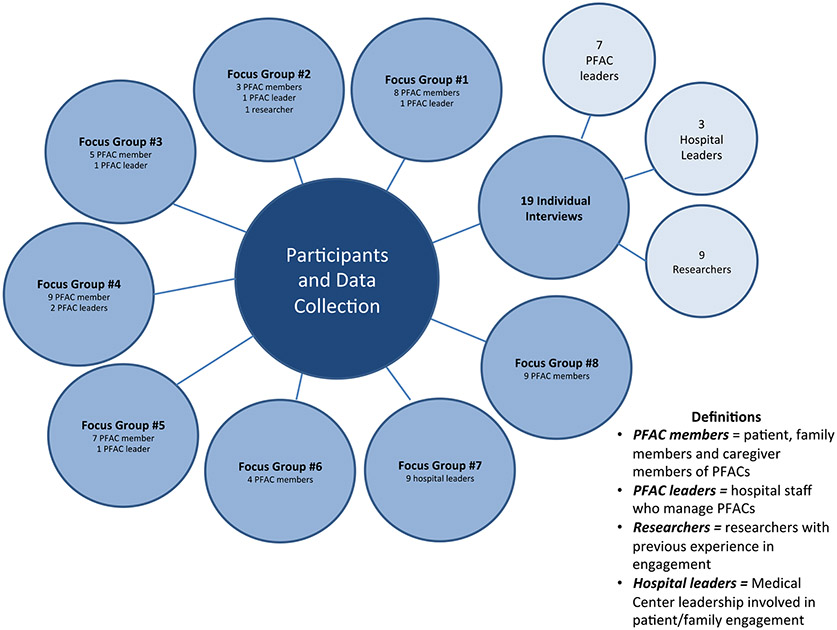

We held structured interviews with participants in-person or over the telephone. Focus groups with PFAC members and PFAC leaders were all held in-person. An additional focus group with hospital leaders and researchers at CCHS was also conducted. Participation by participant type and method of data collection is shown in Fig. 1. We developed a study-specific interview and focus group guide that was informed by previous work related to general patient engagement in research, but that did not specifically relate to PFAC member engagement in research [3, 13, 22, 23]. Questions focused on exploring participants’ experiences and challenges of engaging PFAC members in research and on potential solutions to overcome these challenges (see the online appendix; electronic supplementary material). Further probes were used as necessary to elicit greater detail dependent on participants’ responses. All interviews and focus groups were led by an experienced qualitative researcher (JDH) and audio-recorded.

Fig. 1.

Participants and data collection approach. PFAC = patient and family advisory council

2.5. Data Analysis

We de-identified the transcripts of focus groups and interviews to ensure confidentiality and limit analytic bias [24]. We organized data analysis around the study questions: barriers to PFAC member engagement in research and support for PFAC member engagement in research. We used content analysis to systematically examine the transcripts in order to obtain a condensed understanding and description of content [25]. We hypothesized that previously reported general patient engagement in research principles might also translate to PFAC member research engagement; therefore, we conducted theory-driven (deductive) [25] open coding using categories identified from previous studies [3, 13, 22, 23]. Reviewers determined whether these categories could be identified within our study’s dataset. In parallel, we also undertook a data-driven (inductive) [25] open coding approach to identify codes from our data set that had not been previously described in the literature and that were unique, or of elevated importance, for PFAC member engagement in research. Two trained reviewers (JD and SC), supervised by JH, independently performed open coding using both a theory-driven and data-driven approach to identify coding categories. To ensure methodological rigor, throughout analysis, reviewers (JD, SC, and JH) met to refine and define coding categories, and coding disparities were discussed and resolved by negotiated consensus [26]. Coding categories were then grouped into higher-order categories. Patient partners on the study team (see Sect. 2.2) were asked to participate in data analysis and to help choose the nomenclature for codes and categories to ensure these remained relevant and meaningful from their perspective.

3. Results

3.1. Participants and Data Collection Methods

We conducted eight focus groups and 19 individual interviews with 80 participants including 45 PFAC members, 12 PFAC leaders, and 11 researchers with experience in patient engagement in research and 12 hospital leaders. Study participants represented nine sites from the research network HOMERuN. Participation in focus groups or interviews is summarized in Fig. 1. In total, 48 women and 32 men took part in the study. The average length of focus groups was 52 min (range 19–82 min), and for interviews it was 29 min (range 17–43 min). Thematic saturation appears to have been reached given the same codes and concepts were reported in the final focus groups and interviews.

3.2. Barriers and Challenges to PFAC Member Engagement in Research

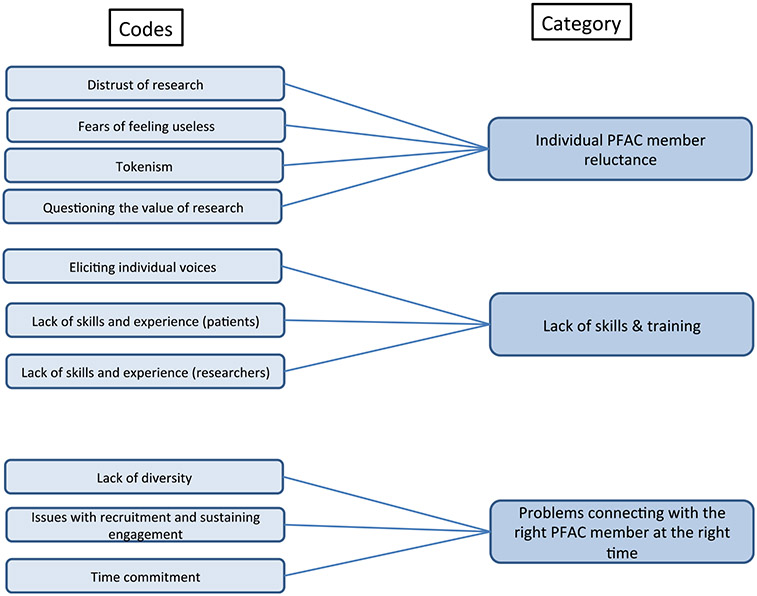

We identified ten codes describing barriers and challenges to PFAC member engagement in research. Of these codes, seven were identified during theory-driven coding and are based on factors identified in prior studies describing barriers to patient engagement in research outside of PFACs: “distrust of research,” “tokenism,” “patients’ lack of skills and experience,” “researcher lack of skills and experience,” “eliciting individual voices,” “lack of diversity,” and “time commitment.” Three new codes emerged from our data-driven approach to analysis: “questioning the value of research,” “fears of feeling useless,” and “issues with recruitment and sustaining engagement.” All codes were then organized into three higher order categories. The first category, “individual PFAC member reluctance,” describes the negative perceptions of research held by PFAC members that limit their willingness to participate and engage in research. The second category, “lack of skills and training,” highlights that PFAC members and researchers often do not have the necessary expertise to meaningfully collaborate and form research partnerships. The third category, “problems connecting with the right person at the right time,” reflects the challenges associated with recruitment, retention and sustainability of PFAC member engagement in research. Codes, code descriptions, and representative quotes are shown in Table 1. A summary of the relationship between codes and categories is shown in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Barriers and challenges to PFAC member engagement in research

| Code and code definition | Representative quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Individual PFAC member reluctance | ||

| 1.1 Distrust of researcha: Patient stakeholders having a distrust of research process, and the institutions | “There is a great deal of suspicion amongst groups that have been disenfranchised when they hear the word research” (PFAC member) | “Reading levels and language that they cannot understand raises a level of suspicion…” (PFAC member) |

| 1.2. Questioning the value of research: A need to show patients why patient involvement in research is important | “The challenging part for me was … to help them to understand that this was an important project … for them because it would have great implications … specifically because it was designed for their population”(PFAC leader) | |

| 1.3. Fears of feeling useless: Patients do not participate as they feel too uncomfortable to share their views because they might be perceived as not informed | “You feel stupid asking questions, and you don’t want to slow down the process. You tend to hold back” (PFAC member) | “They’re intimidated. When they sit and they see all these wonderful, educated faces around the table, they get a little nervous. They’re like – there are six doctors and me” (Hospital leader) |

| 1.4. Tokenisma: Participants feel like they are just there to satisfy a condition “checking off a box” | “One of the greatest challenges for me was I felt that my engagement wasn’t appreciated, that the information that I brought to the table wasn’t viewed in a way that it was going to be able to be incorporated into the research to really help people. The bottom line was I just didn’t feel like I was there to make a difference. I was just there to be on the committee, not to really provide input” (PFAC member) | |

| Theme 2: Lack of skills and training | ||

| 2.1. Lack of skills and experience (patients)a: Patients are reluctant to engage in research because they feel they do not have the skills | “The patients have a huge learning curve ahead of them. Some of our panelists had some form of science background … but many of them, in fact most of them, don’t. So coming into to research was a whole new thing for a lot of these people” (Researcher) | “I think the lack of knowledge of the Institutional Review Board (IRB), research methods and processes is a barrier” (Researcher) |

| 2.2. Lack of skills and experience (researchers): Researchers not trained/skilled in patient engagement in research | “I think the challenge is knowing how to do it [engagement], I mean … I don’t think I was ever trained on how to do it” (Researcher) | “We’re not trained in how to engage… I think it goes back to how we educate researchers on how to engage and why it’s important” (Researcher) |

| 2.3. Eliciting individual voicesa: In big PFAC groups, it is difficult to make each voice important | “When I get everybody in a room together … people tend to agree with each other a lot, but also … you have to really know and have experience in doing group meetings. You have to really understand group dynamics and be able to make sure everybody has a voice and everybody feels free to give their opinions…”(PFAC leader) | |

| Theme 3: Problems connecting with the right person at the right time | ||

| 3.1 Lack of diversitya: Difficulties representing diversity in engagement efforts | “We have so many different cultures represented in our hospital, but we don’t really have enough cultures represented” (PFAC member) | “I think you also need those that are non-English-speaking or different cultures. I think often there is also a cultural aspect that isn’t integrated as much…” (Researcher) |

| 3.2. Issues with recruitment and sustaining engagement: Finding the appropriate time to recruit patients and maintain engagement | “We’ve had it where it’s not a perfect fit. They’re too angry. They’re too upset. They’re still grieving. It doesn’t mean you’re never going to participate. It just might be kind of hard right now” (PFAC leader) | “I think life gets in their way, just like it does ours … I’m asking them to volunteer this time when they’re just getting their lives back together” (Hospital leader) |

| 3.3. Time Commitmenta: Does it fit in the participant’s schedule? Are participants willing to continually engage despite the potentially long research period? | “I think time is a barrier. Sometimes we try to fit it into an 8:00-to-4:30, Monday-through-Friday thing, when many of the researchers are available, as opposed to the patient…We’re doing it on our time clock, not their time clock” (Hospital leader) | “I would say to be mindful of the limitations that people have and how that affects their ability to engage in research – so in terms of what someone’s work schedule is and what responsibilities they have outside of that work schedule influences how available they are to contribute” (PFAC member) |

PFAC = patient and family advisory council

Codes are similar to those previously identified regarding general patient engagement in research

Fig. 2.

Codes and themes describing barriers and challenges to PFAC member engagement in research. PFAC = patient and family advisory council

3.3. Tools, Practices, and Activities to Support PFAC Member Engagement in Research

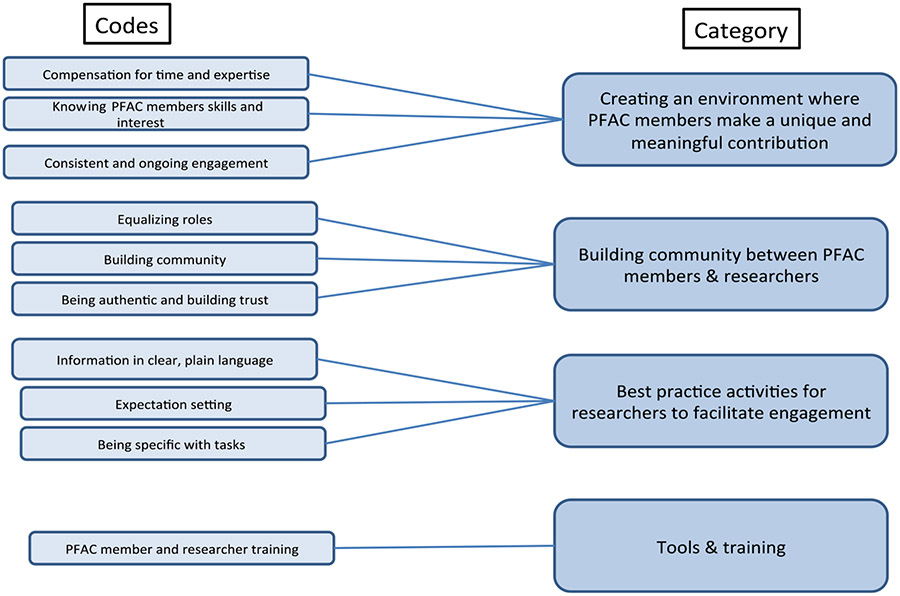

We identified ten codes describing practical steps to support and operationalize PFAC member engagement in research. Of these, two codes were from our theory-driven approach to analysis and had been noted in previous literature around more general approaches to supporting patient engagement: “compensation for time and expertise” and “PFAC member and researcher training.” The remaining eight codes emerged from our data during data-driven coding: “consistent and ongoing engagement,” “knowing PFAC members’ skill sets and interests,” “building community,” “equalizing roles,” “expectation setting,” “information in clear, plain language,” “being specific with tasks,” and “being authentic to build trust.” Codes were organized into four categories: “creating an environment where PFAC members make a genuine and unique contribution”, “building a sense of community between PFAC members and researchers”, “best practice activities for researchers to facilitate engagement” and “tools and training.” Codes, code descriptions, and representative quotes are shown in Table 2, and a summary of the relationship between codes and themes is shown in Fig. 3.

Table 2.

Opportunities and strategies to support PFAC member engagement in research

| Code and code definition | Representative quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 4: Creating an environment where PFAC members make a genuine and unique contribution | ||

| 4.1. Compensation for time and expertisea Monetary and non-monetary support for time engaged in research activities | “Your time is worth something to us, and we want to reimburse you for that” (Researcher) | “If researchers consult with an outside organization, they always get paid. They don’t volunteer their time in that way. So it’s appropriate to provide compensation” (Hospital leader) |

| 4.2. Consistent and ongoing engagement: Regular timing of engagement so that patients do not lose interest in project | “The one thing you don’t want them to feel is that they’re giving all this feedback but we’re not doing anything with it, because then they disengage … it’s keeping them engaged in a meaningful way” (Researcher) | “We recognize that sometimes it’s hard for the patients to come to the hospital for a one hour research meeting … so we’ve made an effort to make all of the meetings web-accessible, it’s helpful, in terms of relationship building” (Researcher) |

| 4.3. Knowing PFAC members’ skill sets and interests: PFAC leaders should understand the skills and interests of members they are working with and match research projects to members accordingly | “One thing we have tried very hard to do is know their areas of expertise. Having people who can help guide the PFAC, knowing people’s areas of interest, so when a researcher comes … I’m not going to ask somebody whose interests are A-B-C to do work on X-Y-Z” (PFAC leader) | |

| Theme 5: Building community between PFAC members and researchers | ||

| 5.1. Building community: PFAC members feel more engaged if they know there are other members and can interact with them | “They’ve asked if we could create a biosketch … with each of their pictures and a little background about them and contact information. Everyone agreed that they want to be in touch with each other” (PFAC leader) | “We are given the opportunity to provide updates on what is going on in our lives in our study newsletter. Then anybody who wants to say, ‘I just had my first grandchild,’ or, ‘I’m going off to college,’ shares this personal information. Because everybody is interested in everybody in the group” (PFAC leader) |

| 5.2. Equalizing roles: PFAC members must feel part of the team, and not feel inferior to the researchers or healthcare team | “A PhD researcher comes into a room, the non-researchers are going to look at that person as an expert and say ‘they’re smarter than I am.’ We change the dynamics where everyone’s on a first name basis. We all sit down at the same table. After the researcher makes the presentation, their job primarily is to listen because they are not the expert in the room – the patients are” (Researcher) | “I really do coach the healthcare team to sit at a table versus doing presentations – because it’s intimidating. You know, I don’t wear a suit jacket when I’m presenting or I’m with my PFACs. I want us to blend … I don’t want it to come across that, ‘I’m in charge of this!’” (PFAC leader) |

| 5.3. Being authentic and building trust | “I think you [researchers] just need to really make sure that they’re authentic, and that they (patients) believe that you’re not just doing this because somebody told you to do it, but that you really embrace the concept. Don’t fake believe it” (PFAC leader) | “We have a little informal ‘get to know each other.’ It’s taking the professional role you have with them, but also showing them that you have another side. So I think transparency and honesty are just so important, and building trust” (Researcher) |

| Theme 6: Best practice activities for researchers to facilitate engagement | ||

| 6.1. Expectation setting: Setting expectations about time commitment and activities | “Clearly stating what’s involved, what it takes and so forth is very critical” (PFAC member) | “If you ask for the time commitment and lay out the parameters, those who can will” (PFAC member) |

| 6.2. Information in clear plain language: Researchers should be cognizant to transfer information in a way that patients understand during all stages of engagement | “It’s been our experience that, when you’re engaging community members they don’t really want these formal slide presentations … you want to be as simple as possible in explaining the study” (Hospital leader) | “He came to one of our meetings … he was throwing out some terms, and we were all looking around at each other, ‘What the heck is he talking about?’ He was talking in his lingo” (PFAC member) |

| 6.3. Being specific with tasks: After patients are recruited, researchers should provide patients specific tasks/goals to work on and achieve | “I think that it’s important to have specific tasks, like things that you’re asking … I think having certain asks of them so that they understand what it is that they’re doing, because this is new for a lot of patients” (Researcher) | “It can be really challenging if what you’re asking them to do is too nebulous or too unformulated. We found to get more concrete and specific is to start them off focusing on something much more specific and concrete…” (Researcher) |

| Theme 7: Tools and training | ||

| 7.1. PFAC member and researcher traininga: Suggestions for training and education activities | “Researchers need to approach with what I would call a sense of cultural humility…it’s a mutual learning relationship, where they need to recognize the gaps in their knowledge.” (PFAC member) | “We have a little section on different types of study designs, pros and cons or what thought process goes into… A little bit about how the IRB works, HIPAA laws, things like that” (PFAC member) |

PFAC = patient and family advisory council

Codes are similar to those previously identified regarding facilitators of general patient engagement in research

Fig. 3.

Codes and themes describing opportunities and strategies to support PFAC member engagement in research. PFAC = patient and family advisory council

4. Discussion

Engaging patients and families as collaborators is increasingly expected and valued in research [12, 14]. PFACs, which are highly prevalent across US hospitals and health systems, provide a potential opportunity to access patients for research engagement [4, 5]. However, the nuances of engaging PFAC members in research have not been well defined. This study identifies a number of barriers to engagement of this specific patient stakeholder population, but more importantly also describes a number of solutions to support the engagement process. Practical activities that facilitate PFAC member engagement are sorely needed given much of the focus to date has been on efforts to describe the value of engagement or the development of frameworks that only outline overarching engagement principles.

PFAC members in our study highly endorsed a partnership role where they and the research team were equal partners, with all voices and perspectives valued [1]. Despite this, PFAC members did describe a number of sub-optimal experiences where their preferences for engagement were not met. Some felt that their presence was merely to fulfill a quota or was just a symbol of engagement rather than an authentic partnership. The concept of tokenism in patient engagement in research has been reported previously by Supple et al., who warn against this practice [27]. Our study confirms that the perception of tokenism is a real barrier to patients’ willingness to become involved in research.

In our study, other barriers to engagement were of a more personal nature. Some expressed fears of being useless or appearing not informed, and many had misunderstandings of the role of scientific research in improving health and outcomes. These individual barriers are new factors to be considered during the engagement of these specific stakeholders. Ultimately, the underlying cause of many of these beliefs may be a result of PFAC members’ lack of direct experience with research. This has been noted elsewhere by Cottrell et al. in a review of barriers to stakeholder engagement in systematic reviews [28]. Many PFAC leaders and researchers in our study noted that while there is a learning curve for patients as they engage in research, this barrier is not insurmountable. Importantly, our study also acknowledges that researchers also lack the skills and expertise to effectively engage with patient stakeholders. Principal investigators of 47 research studies where patient engagement was mandated also support this finding [22]. Research investigators noted that one of the main challenges they faced was a lack of training and skills to effectively partner and engage with patient stakeholders [22].

Our study reports a series of recommendations and activities that can be translated into practice to facilitate PFAC member engagement in research. Financial and other non-monetary support to acknowledge PFAC members’ time and expertise was noted by almost all participants in our study. Compensating patient stakeholders for their involvement in research is endorsed by some funding agencies; however, this practice is not widespread [11]. This is a fundamental change in how researchers plan and prepare budgets for their studies.

Creating comradery and a sense of community between PFAC members and researchers was believed to be an essential foundation for effective engagement. It may be beneficial to move beyond research project activities to also include activities that allow teams to get to know one other on a personal level; including summaries of life events in study newsletters, or using independent facilitators to lead ‘ice-breaker’ sessions between PFAC members and researchers. Similarly, using first names, sitting down when presenting, and dressing casually are all simple but highly effective strategies for researchers to help remove the power differential between ‘experts’ and patient stakeholders. These engagement activities highlight areas where researchers likely need additional communication skills training. They also highlight that building trust and collaborative partnerships between PFAC members and researchers takes time that should be taken into account in research timelines.

Our study has a number of limitations. The PFAC members who took part are highly engaged and many have previous experience in engaging in research; therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to other patient stakeholder groups. While HOMERuN includes some community-based medical centers, participants in this study were from academic medical centers, potentially limiting our findings to other clinical environments. The feasibility of how to implement some of the strategies to support patient engagement in research was not always clearly defined by participants and will require further work to determine.

5. Conclusion

Barriers to engaging PFAC members in research relate to negative perceptions of research and researchers’ lack of training in engagement. Creating supportive environments to build community between PFAC members and researchers is a foundation to effective partnerships.

6. Practice Implications

Our study has identified a number of shared training opportunities and activities for PFAC members and researchers to build skills about research and research engagement. Many of the activities described to support PFAC member engagement in research have the potential to overcome the barriers to engagement that we also identified in this study. These findings can inform the content of toolkits and other training to support PFAC member–researcher engagement in research.

Supplementary Material

Key Points for Decision Makers.

Patient and family advisory councils (PFACs) provide an opportunity for research engagement.

Barriers to engaging PFAC members relate to negative patient perceptions of research.

A lack of researcher training in engagement methods is also a barrier.

Creating supportive environments to build community are a foundation to partnerships.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all stakeholders who participated in interviews and focus groups. Special thanks to all the patient partners for their time and for sharing their perspectives. Additional thanks for Tweedie Gaines, Ann-Marie Baker, Karen Anderson, Jason Selinger, Joanna Laffrey, and Teri Rose for assistance in organizing the focus groups. The statements presented in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

Funding

This study was funded by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Eugene Washington Engagement Award (Harrison #3455).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-018-0298-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Ethical approval This study was reviewed and approved by the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), Brigham & Women’s Hospital (BWH), and Christiana Care Health System (CCHS) Committees on Human Research.

Conflict of interest All authors support patient stakeholder engagement in research and patient-centered care. JDH, WGA, MF, ER, JS, GS, CH, MBC, JB, CW, SC, JD and ADA have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Duffett L. Patient engagement: what partnering with patient in research is all about. Thromb Res. 2017;150:113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fagan MB, Wong C, Morrison CRC, Lewis-O’Connor A, Carnie MB. Patients, persistence and partnership: creating and sustaining patient and family advisory councils in a Hospital Setting. JCOM. 2016;23:219–25. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pomey M, Hihat H, Khalifa M, Lebel P, Neron A. Patient partnerships in quality improvement of healthcare services: patients’ input and challenges faced. Patient Exp J. 2015;2:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrin J, Harris KG, Kenward K, Hones S, Joshi MS, Frosch DL. Patient and family engagement: a survey of US hospital practices. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf JA. A report of the Beryl Institute benchmarking study state of patient experience 2015. Southlake Texas: Beryl Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haycock C, Wahl C. Achieving patient and family engagement through the implementation and evaluation of advisory councils across a large health care system. Nurse Adm Q. 2013;37:242–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagan MB, Wong C, Carnie MB. Brigham and Women’s Hospital Patient and Family Advisory Council report. http://www.brighamandwomens.org/Patients_Visitors/patientresources/DPH_Report_Sept_2016.pdf. Accessed 07 Nov 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warren N. Involving patient and family advisors in the patient and family centered care models. MedSurg Nurs. 2012;21:232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Change Foundation. Patient/family advisory councils in Ontario hospitals: at work, in play. Part 1: emerging themes. http://www.changefoundation.ca/patient-family-advisory-councils-report/. Accessed 07 Nov 2017.

- 10.O’Leary KJ, Killarney A, Hanson LO, Jones S, Malladi M, Marks K, Shah HM. Effect of patient centered bedside rounds on hospitalised patients’ decision control, activation and satisfaction with care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). What we mean by engagement. https://www.pcori.org/engagement/what-we-mean-engagement. Accessed 07 Nov 2017.

- 12.Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, Wang Z, Nabhan M, Shippee N, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: moving from theory to practice. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4:133–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheridan S, Schrandt S, Forsythe L, Advisory Panel on Patient Engagement (2013 inaugural panel), Hillard TS, Paez KA. The PCORI Engagement Rubric: promising practices for partnering in research. Annals of Family Medicine. 2017;15:165–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forsythe LP, Frank LB, Workman TA, Borsky A, Hilliard T, Harwell D, Fayish L. Health researcher views on comparative effectiveness research and research engagement. J Comp Eff Res. 2017;6:246–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez Jolles M, Martines M, Garcia SJ, Stein GL, Mentor Parent Group Members, Thomas KC. Involving Latina/o parents in patient-centered outcomes research: contributions to research study design, implementation and outcomes. Health Expect. 2017;00:1–9. 10.1111/nex.12540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holm KE, Casaburi R, Cerreta S, Gussin HA, Husbands J, Porszasz J, et al. Patient involvement in the design of a patient centered clinical trial to promote adherence to supplemental oxygen therapy in COPD. Patient Patient Cent Outcomes Res. 2016;9:271–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Concannon TW, Meissner P, Grunbaum J, McElwee N, Guise J, Santa J, et al. A new taxonomy for stakeholder engagement in patient centered outcomes research. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:985–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fagan MB, Morrison CRC, Wong C, Carnie MB, Gabbai-Saldate P. Implementing a pragmatic framework for authentic patient-researcher partnerships in clinical research. J Comp Eff Res. 2016;5:297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Auerbach A, Patel MS, Metlay JP, Schnipper JL, Williams MV, Robinson EJ, et al. The Hospital Medicine Reengineering Network (HOMERuN): a learning organization focused on improving hospital care. Acad Med. 2014;89:415–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forsythe LP, Ellis L, Edmundson L, Sabharwal R, Rein A, Konopka K, et al. Patient and stakeholder engagement in the PCORI pilot projects: description and lessons learnt. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forsythe LP, Frank L, Walker KO, Wegener N, Weisman H, Hunt G, et al. Patient and clinician views on comparative effectiveness research and engagement in research. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4:11–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schreier M. Qualitative content analysis in practice. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Supple D, Roberts A, Hudson V, Masefield S, Fitch N, Rahmen M, et al. From tokenism to meaningful patient engagement: best practices in patient involvement in a EU project. Res Involv Engagem. 2015;1:5. 10.1186/s40900-015-0004-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cottrell EK, Whitcock EP, Kato E, Uhl S, Belinson S, Chang C, et al. Defining the benefits and challenges of stakeholder engagement in systematic reviews. Comp Eff Res. 2015;5:13–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.