Abstract

We present the first examples of intramolecular aza-Michael cyclizations of sulfamates and sulfamides onto pendant α,β-unsaturated esters, thioesters, amides, and nitriles. Stirring substrate with catalytic quantities of the appropriate base delivers product in good yield and excellent diastereoselectivity. The reactions are operationally simple, can be performed open to air, and are tolerant of a variety of important functional groups. We highlight the utility of this technology by using it in the preparation of a (−)- negamycin derivative.

Graphical Abstract

Reactions which make use of tethers are an important subset of intramolecular cyclizations. In such reactions, it is of prime importance that the tether is easily attached prior to cyclization and then detachable post-reaction. “Versatile” tethers allow for highly predictable regioselectivity and diastereoselectivity during the cyclization event and activate the product for a further transformation. This is important from the perspective of step count. One of the drawbacks of auxiliary based chemistry is the expenditure of two steps- one for attachment and the other for removal. As versatile tethers can be manipulated in a productive manner after cyclization, tether attachment becomes the only additional (“extra”) step in a synthetic sequence. Sulfamate tethers are particularly versatile.1–5 They can be conveniently attached to amines and alcohols in the substrate, are excellent N-nucleophiles, and can be activated and displaced post-cyclization. Our laboratory has a programmatic focus on the development of sulfamate-tethered chemistry,6–12 and, here, we disclose the first sulfamate-tethered aza-Michael reaction (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

A robust sulfamate-tethered aza-Michael cyclization would supply highly valuable synthetic intermediates.

The aza-Michael reaction is a 1,4 addition of nitrogen nucleophiles into α,β-unsaturated electrophiles and is a powerful method for the construction of new C–N bonds.13–15 Intermolecular aza-Michael additions are convenient from the perspective of step counts but, depending on the reaction context, may suffer from difficulties with regioselectivity and stereoselectivity. Intramolecular aza-Michael reactions for the syntheses of pyrrolidine, piperidine, and related heterocycles have been well-explored.16, 17 The use of versatile tethers in intramolecular aza-Michael chemistry has received less attention; such reactions are particularly powerful because they remove the constraint of needing a pre-existing C–N bond in the molecule to forge a new one.18–25

For reaction optimization (Table 1), we chose substrates that could be prepared in three steps from commercially available 3-[(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy]-1-propanal in a sequence of HWE olefination, TBS removal, and sulfamoylation. Treatment of A with 10-CSA, (S)-BINOL phosphoric acid, or quinine resulted in low yields of desired cyclized product B (Table 1, Entries 1–3). Phosphines are strong promoters of Michael reactions.26, 27 Using 1 equivalent of PEt3 with catalytic (S)-BINOL phosphoric acid gave B in an increased yield of 45% (Table 1, Entry 4). Our laboratory has developed biphasic basic conditions for the ring-opening of epoxides and aziridines by sulfamates11; these conditions were only marginally successful here (Table 1, Entry 5). The most successful results came from switching to either TBAF or 1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine (TMG) in CH2Cl2 or PhCl (Table 1, Entries 6–9). The reaction could be made catalytic with respect to TMG, but the time had to be extended to 48 hours for full consumption of starting material (Table 1, Entry 10).

Table 1.

Select Optimization Conditions.

| R | reagent/catalyst (equivalent) | solvent | time (h) | B:Aa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1b | Et | 10-CSAd [0.3] | MeCN | 52 | 10:70 |

| 2b | Et | BINOL PAe (0.3} | MeCN | 52 | 15:70 |

| 3b | Et | Quinine [0.3] | MeCN | 52 | 10:50 |

| 4b | Et | PEts (1.0), BINOL PA (0.3) | MeCN | 23 | 45:0 |

| 5c | Et | Bu4NOH•30H20 (1.0) | H2O/PhC3h | 22 | 28:0 |

| 6c | Et | TBAFf (0.5) | CH2CI2 | 23 | 85:0 |

| 7c | Et | TMGg (1.0) | CH2CI2 | 24 | 67:0 |

| 8c | Bn | TMG (1.0) | CH2CI2 | 24 | 79:0 |

| 9c | Bn | TMG (1.0) | PhCl | 24 | 89:0 |

| 10c | Bn | TMG (0.24) | PhCl | 48 | 98:0 |

yields calculated from 1H NMR of crude reaction mixture with an internal standard,

reaction at 65 “C.

reaction at RT.

camphorsulfonic acid,

(S)-BINOL phosphoric acid,

1 M in THF.

1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine.

1/1 biphasic mixture

We next wished to examine the effect of various sulfamate N-substituents on the efficiency of cyclization (Scheme 2). Our optimized protocol was compatible with a variety of N-alkyl substituents, including methyl, n-hexyl, and cyclohexyl (Scheme 2, Entries 2–4). We were pleased that cyclization was possible even with bulky N-aryl groups. With N-phenyl sulfamate 9, the reaction time had to be extended from 48 h to 60 h for optimal product yield (Scheme 2, Entry 5). In contrast, with N-tolyl and N-p-OMe-phenyl sulfamates 11 and 13, a normal reaction time of 48 h was sufficient (Scheme 2, Entries 6–7) With N-aryl sulfamates, the enhanced nucleophilicity of the attacking nitrogen helps compensate for the increase in steric bulk.

Scheme 2.

Structure-Reactivity Relationship with Diverse Sulfamate Esters.

In our optimization studies, we had focused on reactions with α,β-unsaturated ethyl and benzyl esters. We sought to explore this cyclization reaction with other esters and related Michael acceptors (Scheme 3). We found that our reaction was productive with a variety of esters, including those with sterically bulky groups such as t-Bu and naphthyl (Scheme 3, Entries 1–3 and Entries 5–7). Interestingly, with substrate 19 (Scheme 3, Entry 3), using TBAF/CH2Cl2 in place of TMG/PhCl was essential for a productive reaction; a crystal structure of product 20 (CCDC 2301582) allowed us to unambiguously confirm its identity. This reaction was scaled from 0.2 mmol to 2.7 mmol (13.5-fold increase) without a loss of yield. We were pleased that other Michael acceptors such as α,β-unsaturated thioesters, α,β-unsaturated nitriles, and α,β-unsaturated tertiary amides were compatible with our optimized protocol (Scheme 3, Entries 4, 8, and 9). With an ester derived from menthol, chiral oxathiazinanes could be prepared (Scheme 4).

Scheme 3.

Exploring Reactivity with Diverse Michael Acceptors.

Scheme 4.

Using a menthol ester allows for the synthesis of chiral oxathiazinanes

Sulfamates could be conveniently synthesized from phenols and were compatible with our optimized protocol (Scheme 5, Entry 1). Products with a variety of substituent patterns could be prepared, including [6,4]-spirocycles (Scheme 5, Entry 2). Substrates with cis α,β-unsaturated esters (Scheme 5, Entries 5, 7, 8, 9, and 11) cyclized with efficiencies comparable to related ones bearing trans α,β-unsaturated esters. 7-membered rings could be forced to form, but the efficiency of cyclization dropped (Scheme 5, Entry 6); the bond angle of the sulfamate tether strongly favors the formation of 6-membered rings.1, 6 Overall, the diastereoselectivity of this reaction was excellent, and, in many cases, a single diastereomer of product was furnished within the limits of 1H NMR detection (Scheme 5, Entries 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 11). Our optimized protocol tolerated a variety of functional groups including TBS, methyl, and benzyl ethers (Scheme 5, Entries 8 and 9). In addition to sulfamates, sulfamides were also compatible with the reaction conditions and gave 1,3-diamine products (Scheme 5, Entry 12).

Scheme 5.

Assessing Functional Group Compatibility and Diastereoselectivity.

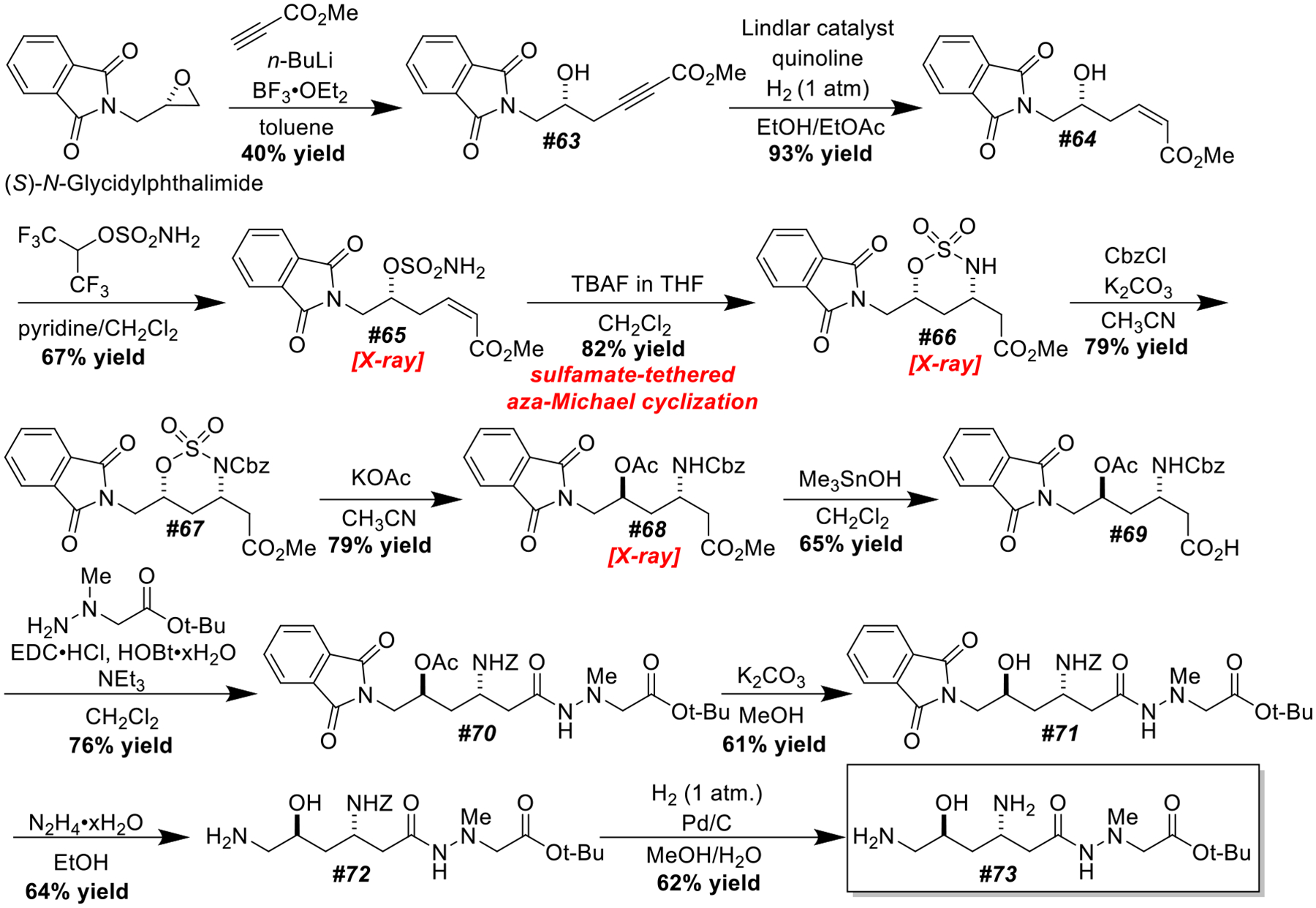

To further highlight the utility of our method, we chose to prepare an ester of the highly polar, heteroatom rich compound (−)-negamycin (Scheme 6). (+)-Negamycin is a natural product antibiotic which has remarkable activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria by interfering with multiple steps of the protein synthesis pathway.28–32 While (+)-negamycin has been the target of numerous synthetic efforts,33, 34 its antipode has only been synthesized once.35 To our knowledge, the biological activity of (−)-negamycin has not been delineated; often, the non-natural enantiomers of natural products and natural-product like compounds have divergent, surprising, and useful activity.36, 37

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of a protected (−)-negamycin.

Our synthesis commenced by deprotonation of methyl propiolate with n-BuLi and regioselective addition into commercial (S)-N-glycidylphthalimide. Lindlar reduction gave α,β-unsaturated ester 64, which was converted into sulfamate 65 (CCDC 2301583) using a Johnson-Magolan sulfamoylation.38 Our sulfamate tethered aza-Michael cyclization converted 65 into oxathiazinane 66 (CCDC 2301584) with good yield and >20:1 diastereoselectivity. To activate oxathiazinane 66 for ring-opening, a Cbz group was appended using K2CO3 and CbzCl in CH3CN. Ring-opening proceeded smoothly by heating with KOAc in CH3CN. The methyl ester was selectively cleaved using Nicolaou’s Me3SnOH protocol.39 Commercially available tert-butyl 2-(1-methylhydrazinyl)acetate was coupled with carboxylic acid 69 using EDC•HCl and HOBt in CH2Cl2. The acetate group was removed using K2CO3, and the phthalimide was cleaved with hydrazine hydrate. Finally, the Cbz group was removed by hydrogenolysis. This completed a synthesis of (−)-negamycin tert-butyl ester.

In summary, we have developed protocols for the intramolecular aza-Michael cyclization of sulfamates and sulfamides onto pendant α,β-unsaturated esters, thioesters, amides, and nitriles. Stirring substrate with catalytic quantities of the appropriate base delivers product in good yield and excellent diastereoselectivity. The reactions are operationally simple, can be performed open to air, and are tolerant of a variety of important functional groups. We have demonstrated the utility of this new reaction by applying it as a key step in the preparation of a (−)-negamycin derivative. Overall, we expect this technology to find much use for the controlled preparation of 1,3-aminoalcohols in both academic and industrial contexts.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R35GM142499 awarded to Shyam Sathyamoorthi. Justin Douglas and Sarah Neuenswander (KU NMR Lab) are acknowledged for help with structural elucidation. Lawrence Seib and Anita Saraf (KU Mass Spectrometry Facility) are acknowledged for help acquiring HRMS data. Joel T. Mague thanks Tulane University for support of the Tulane Crystallography Laboratory.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information contains additional experimental details and NMR spectra.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Espino CG; Wehn PM; Chow J; Du Bois J, Synthesis of 1,3-Difunctionalized Amine Derivatives through Selective C−H Bond Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 6935–6936. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas AA; Nagamalla S; Sathyamoorthi S, Salient features of the aza-Wacker cyclization reaction. Chem. Sci 2020, 11, 8073–8088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams CS; Boralsky LA; Guzei IA; Schomaker JM, Modular Functionalization of Allenes to Aminated Stereotriads. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 10807–10810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paradine SM; Griffin JR; Zhao J; Petronico AL; Miller SM; Christina White M, A manganese catalyst for highly reactive yet chemoselective intramolecular C(sp3)–H amination. Nat. Chem 2015, 7, 987–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanegusuku ALG; Castanheiro T; Ayer SK; Roizen JL, Sulfamyl Radicals Direct Photoredox-Mediated Giese Reactions at Unactivated C(sp3)–H Bonds. Org. Lett 2019, 21, 6089–6095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shinde AH; Sathyamoorthi S, Oxidative Cyclization of Sulfamates onto Pendant Alkenes. Org. Lett 2020, 22, 896–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shinde AH; Sathyamoorthi S, Large Scale Oxidative Cyclization of (E)-hex-3-en-1-yl (4-methoxyphenyl)sulfamate. Org. Synth 2022, 99, 286–304 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shinde AH; Nagamalla S; Sathyamoorthi S, N-arylated oxathiazinane heterocycles are convenient synthons for 1,3-amino ethers and 1,3-amino thioethers. Med. Chem. Res 2020, 29, 1223–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul D; Mague JT; Sathyamoorthi S, Sulfamate-Tethered Aza-Wacker Cyclization Strategy for the Syntheses of 2-Amino2-deoxyhexoses: Preparation of Orthogonally Protected d-Galactosamines. J. Org. Chem 2023, 88, 1445–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagamalla S; Mague JT; Sathyamoorthi S, Progress towards the syntheses of Bactobolin A and C4-epi-Bactobolin A using a sulfamate-tethered aza-Wacker cyclization strategy. Tetrahedron 2022, 133112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagamalla S; Mague JT; Sathyamoorthi S, Covalent Tethers for Precise Amino Alcohol Syntheses: Ring Opening of Epoxides by Pendant Sulfamates and Sulfamides. Org. Lett 2023, 25, 982986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagamalla S; Johnson DK; Sathyamoorthi S, Sulfamate-tethered aza-Wacker approach towards analogs of Bactobolin A. Med. Chem. Res 2021, 30, 1348–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelly NR; Alexander GG; Yurii GB, Michael synthesis of esters of β-amino acids: stereochemical aspects. Russ. Chem. Rev 1996, 65, 1083. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung ME, 1.1 - Stabilized Nucleophiles with Electron Deficient Alkenes and Alkynes. In Comprehensive Organic Synthesis, Trost BM; Fleming I, Eds. Pergamon: Oxford, 1991; pp 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Little RD; Masjedizadeh MR; Wallquist O; McLoughlin JI, The Intramolecular Michael Reaction. In Organic Reactions, 2004; 315–552. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sánchez-Roselló M; Escolano M; Gaviña D; del Pozo C, Two Decades of Progress in the Asymmetric Intramolecular aza-Michael Reaction. Chem. Rec 2022, 22, e202100161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sánchez-Roselló M; Aceña JL; Simón-Fuentes A; del Pozo C, A general overview of the organocatalytic intramolecular aza-Michael reaction. Chem. Soc. Rev 2014, 43, 7430–7453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirama M; Hioki H; Itô S; Kabuto C, Conjugate addition of internal nucleophile to chiral vinyl sulfoxides with stereogenic center at the allylic carbon. “intramolecular” double asymmetric induction. Tetrahedron Lett 1988, 29, 3121–3124. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishikawa T; Nagai K; Senzaki M; Tatsukawa A; Saito S, Hemiaminal generated by hydration of ketone-based nitrone as an N,O-centered nucleophile in organic synthesis. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 2433–2448. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guanti G; Moro A; Narisano E, Asymmetric synthesis of protected α-alkyl-β-amino-δ-hydroxy esters by stereocontrolled elaboration of THYM*. Tetrahedron Lett 2000, 41, 3203–3207. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiroma M; Shigemoto T; Yamozaki Y; Itô S, Diastereoselective synthesis of N-acetyl-D,L-acosamine and N-benzoyl-D,Lristosamine. Tetrahedron Lett 1985, 26, 4133–4136. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirama M; Shigemoto T; Itô S, Reversal of diastereofacial selectivity in the intramolecular michael addition of -α-carbamoyloxy-α,β-unsaturated esters. Synthesis of N-benzoyl-D,L-daunosamine. Tetrahedron Lett 1985, 26, 4137–4140. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fang C; Shanahan CS; Paull DH; Martin SF, Enantioselective Formal Total Syntheses of Didehydrostemofoline and Isodidehydrostemofoline through a Catalytic Dipolar Cycloaddition Cascade. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 10596–10599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gais H-J; Loo R; Roder D; Das P; Raabe G, Asymmetric Synthesis of Protected β-Substituted and β,β-Disubstituted β-Amino Acids Bearing Branched Hydroxyalkyl Side Chains and of Protected 1,3-Amino Alcohols with Three Contiguous Stereogenic Centers from Allylic Sulfoximines and Aldehydes. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2003, 2003, 1500–1526. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirama M; Shigemoto T; Yamazaki Y; Ito S, Carbamate-mediated functionalization of unsaturated alcohols. 3. Intramolecular Michael addition of O-carbamates to .alpha.,.beta.-unsaturated esters. A new diastereoselective amination in an acyclic system. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1985, 107, 1797–1798. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gimbert C; Lumbierres M; Marchi C; Moreno-Mañas M; Sebastián RM; Vallribera A, Michael additions catalyzed by phosphines. An overlooked synthetic method. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 8598–8605. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo H; Fan YC; Sun Z; Wu Y; Kwon O, Phosphine Organocatalysis. Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 10049–10293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizuno S; Nitta K; Umezawa H, Mechanism of action of negamycin in Escherichia coli K12. I. Inhibition of initiation of protein synthesis. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1970, 23, 581–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olivier NB; Altman RB; Noeske J; Basarab GS; Code E; Ferguson AD; Gao N; Huang J; Juette MF; Livchak S; Miller MD; Prince DB; Cate JHD; Buurman ET; Blanchard SC, Negamycin induces translational stalling and miscoding by binding to the small subunit head domain of the Escherichia coli ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 16274–16279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schroeder SJ; Blaha G; Moore PB, Negamycin Binds to the Wall of the Nascent Chain Exit Tunnel of the 50S Ribosomal Subunit. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2007, 51, 4462–4465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taguchi A; Nishiguchi S; Shiozuka M; Nomoto T; Ina M; Nojima S; Matsuda R; Nonomura Y; Kiso Y; Yamazaki Y; Yakushiji F; Hayashi Y, Negamycin Analogue with Readthrough-Promoting Activity as a Potential Drug Candidate for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2012, 3, 118–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taguchi A; Hamada K; Hayashi Y, Chemotherapeutics overcoming nonsense mutation-associated genetic diseases: medicinal chemistry of negamycin. J. Antibiot 2018, 71, 205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu L; Hong R, Pursuing effective Gram-negative antibiotics: The chemical synthesis of negamycin. Tetrahedron Lett 2018, 59, 2112–2127. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Shiju, L. X, Wang Yan, Zheng Yucong, Han Shiqing, Yu Huilei, Huang Shahua, Formal Synthesis of Gram-Negative Antibiotic Negamycin. Chin. J. Org. Chem 2020, 40, 521–527. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin C-K; Tseng P-Y, Total synthesis of (–)-negamycin from a chiral advanced epoxide. Synth. Commun 2023, 53, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liotta DC; Painter GR, Discovery and Development of the Anti-Human Immunodeficiency Virus Drug, Emtricitabine (Emtriva, FTC). Acc. Chem. Res 2016, 49, 2091–2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Logan MM; Toma T; Thomas-Tran R; Du Bois J, Asymmetric synthesis of batrachotoxin: Enantiomeric toxins show functional divergence against NaV. Science 2016, 354, 865–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sguazzin MA; Johnson JW; Magolan J, Hexafluoroisopropyl Sulfamate: A Useful Reagent for the Synthesis of Sulfamates and Sulfamides. Org. Lett 2021, 23, 3373–3378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicolaou KC; Estrada AA; Zak M; Lee SH; Safina BS, A Mild and Selective Method for the Hydrolysis of Esters with Trimethyltin Hydroxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2005, 44, 1378–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.