Abstract

Background:

Convergent preclinical and clinical evidence has linked the anterior insula to impulsivity and alcohol-associated compulsivity. The anterior insula is functionally connected to the anterior cingulate cortex, together comprising the major nodes of the salience network, which serves to signal salient events, including negative consequences. Clinical studies have found structural and functional alterations in the anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortices of alcohol dependent individuals. No studies have yet investigated the association between morphometric abnormalities in salience network regions and the phenotype of high levels of impulsivity and compulsivity seen in alcohol dependent individuals.

Methods:

In the current study, we compared self-report impulsivity, decisional impulsivity, self-report compulsivity, and structural neuroimaging measures in a sample of alcohol dependent individuals (n = 60) and a comparison group of healthy controls (n = 49). From the structural magnetic resonance images, we calculated volume and cortical thickness for 6 regions of interest: left and right anterior insula, posterior insula, and anterior cingulate.

Results:

We found that alcohol dependent individuals had smaller anterior insula and anterior cingulate volumes, as well as thinner anterior insula cortices. There were no group differences in posterior insula morphometry. Anterior insula and anterior cingulate structural measures were negatively associated with self-report impulsivity, decisional impulsivity, and compulsivity measures.

Conclusions:

Our results suggest that addiction endophenotypes are associated with salience network morphometry in alcohol addiction. These relationships indicate that salience network hubs represent potential treatment targets for impulse control disorders, including alcohol addiction.

Keywords: Salience network, Morphometry, Alcohol dependence, Impulsivity, Compulsivity

1. Introduction

Problematic alcohol use is a serious public health issue. In the United States, alcohol misuse contributes to 88,000 deaths per year and is estimated to cost $245 billion each year due to lost productivity, health care costs, law enforcement, and associated criminal justice expenses (General, 2016). An estimated 6% of people (15.7 million) in the United States meet criteria for a current alcohol use disorder (Quality, 2016). A hallmark of alcohol use disorders, as well as other drug addictions, is compulsive drug use (NIDA, 2012). Compulsive drug use is behaviorally manifested by the tendency to continue seeking and taking a drug, despite negative or aversive consequences.

Impulsivity is a multi-dimensional construct that has been linked to addiction. Broadly defined, impulsive actions are premature, unplanned or poorly planned, and often conducted in inappropriate contexts (Moeller et al., 2001). Self-report trait impulsivity, behavioral impulsivity, and decisional impulsivity scores are higher in addicted individuals than non-addicted controls (MacKillop et al., 2011; Verdejo-Garcia et al., 2008). Impulsivity is also thought to contribute to the development of addictive disorders. Children with a family history of substance use disorders are more impulsive than lower risk children prior to drug and alcohol exposure (Verdejo-Garcia et al., 2008). Trait impulsivity is also higher in non-drug using siblings pairs of stimulant dependent individuals (Ersche et al., 2010). Further, impulsive behavior can predict alcohol-related problems, comorbid alcohol and drug use, and the number of illicit drugs used independently of parental alcohol dependence (Nigg et al., 2006). Together, these data provide evidence for the hypothesis that impulsivity is an endophenotype for addiction, where impulsivity is both a vulnerability factor for and impacts the severity of addiction (Ersche et al., 2012b).

The insula has been identified as a key region in addiction. Smokers with insula damage were more likely to experience a complete disruption of addiction, described by an ability to stop smoking immediately after an insular brain lesion, without relapse, and a loss of craving, than individuals with a non-insular brain lesion (Naqvi et al., 2007). Animal models have also implicated the insula as a critical region for impulsivity and compulsivity. Seif and colleagues found that the glutamatergic inputs from the anterior insula to the nucleus accumbens were necessary for compulsive alcohol seeking (Seif et al., 2013). When these anterior insula inputs were optogenetically inhibited, rats reduced their consumption of alcohol paired with an aversive consequence, but did not reduce their consumption of unpaired alcohol (Seif et al., 2013). Belin-Rauscent and colleagues found that motor impulsivity was inversely related to anterior insula cortical thickness in rats and that anterior insula lesions resulted in a decrease in motor impulsivity specifically in high impulsive rats (Belin-Rauscent et al., 2016). Moreover, they found that bilateral anterior insula lesions both prevented the development of schedule-induced polydipsia, a measure of compulsive behavior, and reduced the level of schedule-induced polydipsia in high compulsive rats (Belin-Rauscent et al., 2016). Together, these studies indicate that the anterior insula may be a core neural substrate for maladaptive impulse control disorders, including alcohol addiction.

The anterior insula (AI) is functionally connected to the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), together representing the key nodes of the salience network (Menon and Uddin, 2010). In the salience network, the AI facilitates a bottom-up signal to the ACC to signal salient events. This process often involves task-switching, where one’s attention is “switched” through the Salience Network (SN) to other large scale networks. EEG studies evaluating the detection of deviant stimuli have provided the temporal resolution to measure this bottom-up salience signal. Initially, sensory areas are activated during the detection of novel stimuli. Next, this signal is transmitted to the AI and then the ACC, where top-down control signals are generated and sent to further neocortical regions. Finally, the ACC facilitates the response to the salient stimuli through connections to motor areas (Menon and Uddin, 2010). In addictive disorders, the detection of salient events including negative consequences may be disrupted. Preclinical studies have also implicated the ACC in impulsive responding. Lesions of the ACC result in increases in motor impulsivity in rats (Muir et al., 1996).

Previous studies have identified volume reductions in the insula and ACC in alcohol dependent individuals (Demirakca et al., 2011; Durazzo et al., 2014; Durazzo et al., 2011). Alcohol dependent individuals have decreases in right AI volume (Makris et al., 2008), and bilateral AI volume (Senatorov et al., 2015). Alcohol dependent individuals also had smaller volume of the right caudal and left rostral ACC compared to controls (Durazzo et al., 2011). Further morphometric damage has also been described in alcohol dependent individuals. Previous studies have also identified reductions in insula and ACC cortical thickness (Durazzo et al., 2011; Momenan et al., 2012). Durazzo and colleagues identified alcohol-associated decreases in the cortical thickness of the right caudal and left rostral ACC (Durazzo et al., 2011).

Despite the importance of the insula in addiction, and the indication that it is a critical region for compulsive and impulsive behavior, there have been no studies investigating the relationship between insula morphometry, impulsivity, and compulsivity in addiction. Here we investigate the volume and cortical thickness of the AI, posterior insula (PI), and ACC in alcohol dependent individuals (ALC) and light-drinking healthy controls (HC). We also investigated self-report impulsivity, decisional impulsivity, and self-report compulsivity in the same group. We hypothesized that there would be lower volumes and thinner cortices in the anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex in the ALC group. We further hypothesized that there would be a negative association between impulsivity/compulsivity measures and AI morphometric measures.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were selected from individuals enrolled in inpatient and outpatient screening protocols at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) from 2014 to 2016, who underwent a structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The screening protocols were approved by an NIH Institutional Review Board. Participants provided written informed consent. Participants were all right-handed individuals, ages 21–60. Exclusion criteria included significant medical illness (including diabetes and untreated hypertension), neurological disorders, history of psychotic symptoms, history of head trauma, ferrous metal in the body, pregnancy, and positive urine drug tests. Individuals with high levels of alcohol withdrawal symptoms (scores ≥ 8 on the Clinical Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised (CIWA-Ar)) were also excluded.

As part of the screening visit, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID IV-TR; (First et al., 1997)) was administered to all participants. Participants were divided into two groups based on their current drinking behavior and DSM-IV SCID alcohol diagnosis: HC and ALC. Diagnoses of psychotic disorders were exclusionary, other Axis I diagnoses were not exclusionary (see Table S1 for breakdown of Axis I diagnoses). The presence or absence of Axis I disorders beyond alcohol dependence was coded as 1 or 0 and included as a covariate. HC (n = 49) were individuals who drank at or below NIAAA recommendations for low risk drinking (maximum 7 drinks/week and no more than 3 drinks/day for women and 14 drinks/week and no more than 4 drinks/day for men; https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking). ALC (n = 60) were individuals who were undergoing inpatient treatment for their alcohol use and met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence. ALC were in early abstinence (< 1 month since date of last drink) at the time of the study (see Table 1 for demographic information).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| HC | ALC | t-stat/ Chi- Squarea |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 49) | (n = 60) | |||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 38.77 ± 10.93 | 42.32 ± 11.91 | 1.61 | 0.11 |

| Gender (m/f) | 23/26 | 46/14 | 10.36 | 0.001 |

| Years of Education | 16.70 ± 3.58 | 13.72 ± 2.38 | 5.01 | < 0.001 |

| Axis I (%) | 2 | 40 | 27.38 | < 0.001 |

| Smokers (%) | 0 | 55 | 51.09 | < 0.001 |

| Trait Anxiety | 29.71 ± 8.25 | 40.48 ± 11.74 | 5.42 | < 0.001 |

| Drinking Measures | ||||

| AUDIT Score | 2.53 ± 1.70 | 25.45 ± 7.26 | 14.05 | < 0.001 |

| ADS Score | 0.9 ± 1.91 | 18.17 ± 8.14 | 9.01 | < 0.001 |

| Total Drinks (90 days) | 26.42 ± 25.36 | 963.02 ± 644.76 | 6.36 | < 0.001 |

| Drinks/Day | 1.52 ± 0.75 | 13.69 ± 8.34 | 5.93 | < 0.001 |

| Compulsive Drinking score | 1.71 ± 1.67 | 10.53 ± 4.68 | 9.51 | < 0.001 |

| Abstinence Duration (days) | – | 17.85 ± 9.73 | – | – |

| Impulsivity | ||||

| BIS Total | 53.02 ± 8.08 | 65.67 ± 12.50 | 2.81 | 0.006 |

| Attentional | 12.29 ± 3.32 | 15.62 ± 4.12 | 2.03 | 0.04 |

| Motor | 20.65 ± 3.13 | 24.43 ± 4.91 | 2.40 | 0.02 |

| Non-planning | 20.08 ± 4.12 | 25.62 ± 5.45 | 2.57 | 0.01 |

| Delay Discounting (ln(k)) | −4.70 ± 1.12 | −3.40 ± 1.93 | 2.39 | 0.02 |

Independent t-tests were conducted to compare continuous variables and Chi-square tests were conducted to compare categorical variables.

2.2. Alcohol and smoking measures

Participants completed several alcohol-related questionnaires: Timeline Followback (TLFB), Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), and Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS). The TLFB is a self-report measure of alcohol consumption over the past 90 days (Sobell et al., 1996). The AUDIT was designed as a screening tool for hazardous alcohol use; it assesses alcohol consumption, drinking behaviors, and alcohol-related problems (Saunders et al., 1993). The ADS measures elements of alcohol dependence including loss of control over alcohol use, salience of alcohol-seeking behaviors, tolerance, and withdrawal, and produces a composite score that describes an individual’s level of alcohol dependence (Skinner and Horn, 1984). To determine smoking status, participants completed the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (Heatherton et al., 1991). Participants also completed the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Form Y-2, which measured their trait anxiety levels (Spielberger, 1983)

2.3. Impulsivity and compulsivity measures

Participants completed the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11; (Patton et al., 1995)), a self-report measure, which evaluates 3 dimensions of impulsivity: attentional impulsiveness, motor impulsiveness, and non-planning impulsiveness. They also completed a delay-discounting task, which measures decisional impulsivity (Mitchell, 1999). This task presents a series of choices to participants, where the participant must choose between a smaller, immediate monetary reward ($10-$90) or a fixed, larger reward ($100) that is delayed in time (0–30 days). The rate of discounting, or devaluing, the delayed outcome is represented by k, the delay discounting factor. For analysis purposes, we applied a logarithmic transformation (ln) to k to normalize the data. Values of ln (k) closer to 0 (i.e., k = 1) indicate a higher discounting rate.

Participants also completed the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (OCDS), a self-report assessment of obsessive thoughts about alcohol and compulsive drinking behaviors (Anton et al., 1995). We used the compulsive drinking subscale score to assess compulsivity, which reflects the participants’ current drinking (HC) or drinking pretreatment (ALC), the amount of interference drinking causes in functioning, and the participants’ control over drinking.

2.4. MRI acquisition and MR segmentation

Whole brain anatomical images were collected using a 3T Siemens Skyra scanner with a 20-channel head coil. High resolution T1-weighted 3-D structural scans were acquired for each participant using an MPRAGE sequence (128 axial slices, TR = 1200 ms TE = 30 ms, 256 × 256 matrix, 0.938 × 0.938 × 1.0 mm3). Head motion was minimized using padding and images were inspected prior to automated analysis.

T1-weighted structural images were processed using FreeSurfer version 5.3 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu), an automated parcellation program. The FreeSurfer processing pipeline was followed to obtain morphometric measures. Briefly, the processing pipeline consists of motion correction, removal of non-brain tissue, automated Talairach transformation, segmentation of subcortical structures, intensity normalization, tessellation of the gray matter/white matter boundary, topology correction, and surface deformation. The images were then automatically parcellated based on cortical gyral and sulcal structure (for further details see (Fischl and Dale, 2000; Fischl et al., 2004)).

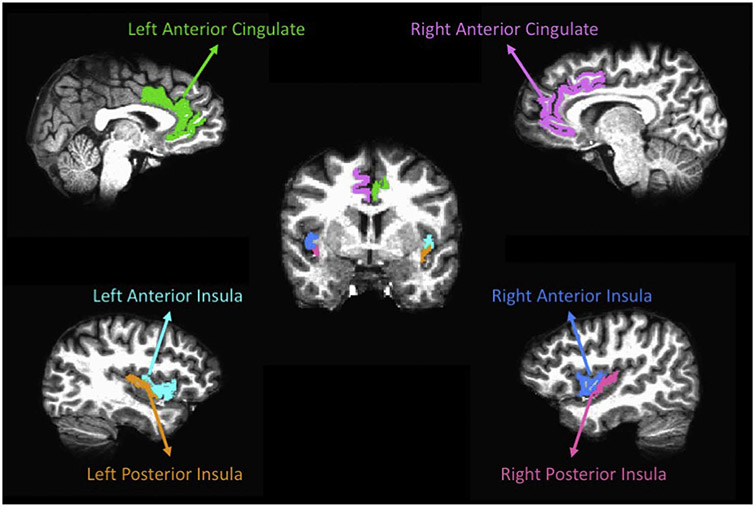

We obtained regional volume and cortical thickness estimates from the Destrieux Atlas (Destrieux et al., 2010) provided in the Freesurfer software. In the Destrieux Atlas, the insula is limited by the circular sulcus, which is divided into three segments: superior, which limits the insula from the inferior frontal gyri, anterior, which limits the insula from the orbital gyri, and inferior, which limits the insula from the superior temporal gyrus. The insula is also divided by the central sulcus into the short insular gyri (anterior) and the long insular gyrus (posterior). The Destrieux Atlas divides the cingulate gyrus into 5 segments: anterior, middle-anterior, middle-posterior, posterior-dorsal, and posterior-ventral. The anterior and middle anterior regions were combined to create the anterior cingulate cortex ROIs. Gray matter volume and cortical thickness estimates were obtained for the anterior and posterior insula and anterior cingulate ROIs (see Fig. 1 for an example ROI segmentation). We also obtained intracranial volume (ICV) measurements from Freesurfer for each subject. Insula and ACC ROIs were normalized by intracranial volume (ICV) using the following equation to account for differences in brain sizes:

Fig. 1.

ROI parcellation from a representative participant.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted with JMP software (version 10.0.0; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Group comparisons were separately analyzed with multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) for volume and cortical thickness for the left and right AI, PI, and ACC ROIs. For all comparisons, age, gender, years of education, and the presence of a current Axis I disorder (beyond alcohol dependence) were added as nuisance covariates. For the cortical thickness comparisons, ICV was included as an additional nuisance covariate. ICV was included as a covariate for the cortical thickness analysis but not for the volume analysis as the gray matter volumes were already ICV normalized prior to analysis. Because two group comparisons were run (one assessing volume and one assessing cortical thickness), the overall model was considered significant at p < 0.025. Significant univariate tests were followed up with t-tests to localize group differences. Bonferroni correction was applied to the post-hoc tests correct for multiple comparisons. Cohen’s d was calculated to measure effect sizes for pairwise comparisons (Cohen, 1998). Partial correlations, controlling for age, years of education, anxiety, and ICV for cortical thickness, were conducted to assess associations between significant morphometric measures and impulsivity and compulsivity scales. Additional partial correlations, controlling for the above variables, were conducted to assess associations between alcohol abstinence, alcohol dependence severity, and morphometric measures. Correlations were conducted in each group separately. Because there were a total of 12 comparisons per model, we considered correlations with a p-value of < 0.004 significant.

A post-hoc analysis of smoking status on morphometry and the association between morphometry and impulsivity and compulsivity measures was conducted in the ALC group only. This analysis followed the same methods as above (see Supplementary data for details).

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

The HC and ALC groups did not differ on age. There were more males in the ALC group. HC had a higher level of education. There were more individuals with current Axis I diagnoses (excluding current alcohol dependence) and more smokers in the ALC group. ALC individuals had higher scores on all alcohol measures – the AUDIT, ADS, total drinks over 90 days, drinks per drinking day, and the compulsive drinking sub-score. ALC individuals also had higher scores on self-report impulsivity and had higher discounting rates on the delay discounting task. ALC individuals had higher trait anxiety scores than HC (see Table 1).

3.2. Morphometry

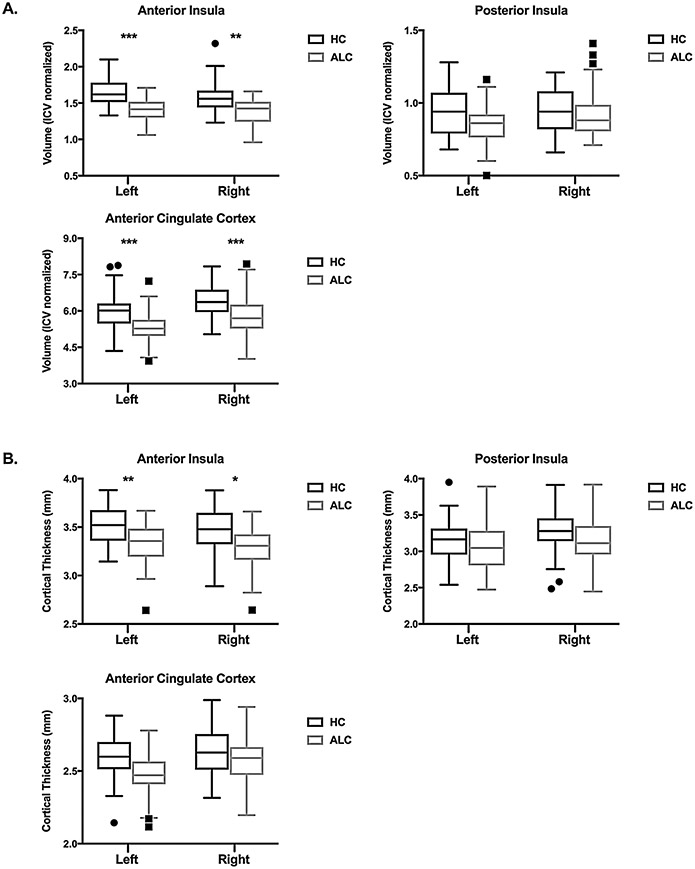

The MANCOVA model for volume was significant: F6,89 = 3.05, p < 0.001 (Wilks’ Lambda), with a significant effect of group: F6,89 = 5.95, p < 0.001. The nuisance covariates (age, gender, years of education, and current Axis I disorder) were not significant. There was a main effect of group for left and right AI volume, with ALC having smaller volumes. There was no effect of group on left or right PI volume. There was also a main effect of group for left and ACC volume, where ALC had smaller volumes than HC (see Table 2 and Fig. 2 for details).

Table 2.

Morphometry results.

| HC | ALC | t-stat | Effect Size | p-value corrected |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 49) | (n = 60) | (Cohen’s d) | |||

| Volume | |||||

| Left AI | 1.65 ± 0.18 | 1.40 ± 0.15 | 5.14 | 1.51 | < 0.001 |

| Right AI | 1.57 ± 0.21 | 1.39 ± 0.17 | 3.52 | 0.94 | 0.004 |

| Left PI | 0.94 ± 0.16 | 0.86 ± 0.13 | 2.26 | 0.55 | 0.18 |

| Right PI | 0.93 ± 0.16 | 0.92 ± 0.15 | 0.69 | 0.06 | 0.35 |

| Left ACC | 5.97 ± 0.76 | 5.31 ± 0.63 | 4.12 | 0.95 | < 0.001 |

| Right ACC | 6.42 ± 0.78 | 5.77 ± 0.77 | 4.11 | 0.84 | < 0.001 |

| Thickness | |||||

| Left AI | 3.52 ± 0.19 | 3.33 ± 0.20 | 3.43 | 0.97 | 0.005 |

| Right AI | 3.47 ± 0.23 | 3.29 ± 0.30 | 3.12 | 0.67 | 0.01 |

| Left PI | 3.16 ± 0.28 | 3.06 ± 0.30 | 2.08 | 0.34 | 0.24 |

| Right PI | 3.28 ± 0.28 | 3.13 ± 0.32 | 1.07 | 0.50 | 0.29 |

| Left ACC | 2.63 ± 0.15 | 2.57 ± 0.16 | 1.43 | 0.39 | 0.16 |

| Right ACC | 2.65 ± 0.16 | 2.57 ± 0.16 | 2.01 | 0.50 | 0.24 |

HC = healthy controls; ALC = alcohol dependent individuals; AI = anterior insula; PI = posterior insula; ACC = anterior cingulate cortex.

Values shown for each group are mean and standard deviation.

Bold typeface indicates significant group differences.

Fig. 2.

Box and whisker plot of group differences in (A) volume and (B) cortical thickness for anterior insula, posterior insula, and anterior cingulate cortex regions of interest. Individual values outside the whiskers are plotted as outliers. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, corrected.

The MANCOVA model for cortical thickness was also significant: F6,88 = 2.68, p < 0.001 (Wilks’ Lambda) and there was a significant effect of group: F6,88 = 3.52, p = 0.004, age: F6,88 = 3.02, p = 0.01, and ICV: F6,88 = 2.85, p = 0.02. There were no significant effects of gender, years of education, or current Axis I disorder diagnosis on cortical thickness. There was a main effect of group for left and right AI cortical thickness, with ALC individuals having thinner cortices. There were no group differences in cortical thickness for left or right PI. There was also no effect of group on ACC thickness (see Table 2 and Fig. 2 for details). There was a main effect of age on left and right ACC thickness (left ACC: t = −3.73, p = 0.002; right ACC: t = −4.15, p < 0.001), where age was negatively associated with thickness. There were no significant group by age interactions on cortical thickness.

3.3. Impulsivity and compulsivity

Self-report trait impulsivity, decisional impulsivity, and compulsivity scores were associated with AI, and ACC morphometric measures in ALC. BIS-11 total score was negatively correlated with left AI volume (r = −0.53, p < 0.001), right AI volume (r = −0.37 p < 0.001), left ACC volume (r = −0.29, p = 0.003), and right ACC volume (r = −0.27, p = 0.004). BIS-11 scores were also negatively correlated with left AI cortical thickness (r = −0.49, p < 0.001) and right AI cortical thickness (r = − 0.35, p = 0.001). Delay discounting also negatively correlated with left AI volume (r = −0.51, p < 0.001) and right AI volume (r = −0.44, p < 0.001), but was not correlated with left or right ACC volume. Delay discounting was negatively associated with left AI cortical thickness (r = −0.36, p = 0.003) and right AI cortical thickness (r = −0.38, p = 0.002), but was not correlated with left or right ACC thickness after correction for multiple comparisons.

OCDS compulsive subscale scores were negatively associated with left AI volume (r = −0.54, p < 0.001), right AI volume (r = −0.58, p < 0.001), left ACC volume (r = −0.42, p < 0.001), and right ACC volume (r = −0.38, p = 0.001). OCDS compulsive subscale scores were also negatively associated with left AI cortical thickness (r = −0.53, p < 0.001), right AI cortical thickness (r = −0.47, p < 0.001), left ACC thickness (r = −0.40, p = 0.002), and right ACC thickness (r = −0.43, p < 0.001; see Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation matrix.

| BIS | DD | Compulsivity | L AI Volume | R AI Volume | L ACC Volume | R ACC Volume | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIS | 1 | ||||||

| DD | 0.52 | 1 | |||||

| Compulsivity | 0.43 | 0.30 | 1 | ||||

| L AI | −0.53 | −0.51 | −0.54 | 1 | |||

| R AI | −0.37 | −0.44 | −0.58 | 0.67 | 1 | ||

| L ACC | −0.29 | −0.05 | −0.42 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 1 | |

| R ACC | −0.27 | −0.07 | −0.38 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.75 | 1 |

| BIS | DD | Compulsivity | L AI Thickness | R AI Thickness | L ACC Thickness | R ACC Thickness | |

| BIS | 1 | ||||||

| DD | 0.52 | 1 | |||||

| Compulsivity | 0.43 | 0.30 | 1 | ||||

| L AI | −0.49 | −0.36 | −0.53 | 1 | |||

| R AI | −0.35 | −0.38 | −0.47 | 0.32 | 1 | ||

| L ACC | −0.11 | −0.22 | −0.40 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 1 | |

| R ACC | −0.13 | −0.20 | −0.43 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.95 | 1 |

BIS = Barratt’s Impulsivity Scale; DD = delay discounting (ln(k)); AI = anterior insula; ACC = anterior cingulate cortex.

Bold typeface indicates significant correlations. All correlations are in ALC group only.

In HC only self-report trait impulsivity was associated with ACC morphometric measures. BIS-11 total score was negatively correlated with left ACC volume (r = −0.34, p = 0.003), but not right ACC, left AI, or right AI volume. BIS-11 total score was also negatively correlated with left ACC thickness (r = −0.33, p = 0.003) and right ACC thickness (r = −0.31, p = 0.004), but not left AI or right AI thickness. There were no significant associations between decisional impulsivity or compulsivity scores and morphometric measures in HC.

3.4. Alcohol measures

There were no significant correlations between abstinence duration, impulsivity, compulsivity, or morphometric measures (all p’s > 0.05). Alcohol dependence severity was significantly associated with self-report impulsivity (r = 0.48, p < 0.001), decisional impulsivity (r = 0.36, p < 0.001) and compulsivity (r = 0.58, p < 0.001). Alcohol dependence severity was also negatively correlated with left AI volume (r = −0.39, p < 0.001) right AI volume (r = −0.42, p < 0.001), left ACC volume (r = −0.32, p = 0.003), but was not significantly associated with right ACC volume after correction for multiple comparisons. ADS was also negatively associated with left AI cortical thickness (r = −0.33, p = 0.001) and right AI cortical thickness (r = −0.30, p = 0.002).

4. Discussion

This study sought to elucidate morphometric differences in salience network regions in alcohol dependent individuals and controls, and to evaluate if these differences were associated with measures of impulsivity and compulsivity. We confirmed our previous finding of anterior insula volume decreases in alcohol dependent individuals and found additional volume decreases in the anterior cingulate cortex. We also found that alcohol dependent individuals had thinner anterior insula cortices than controls. Further, in alcohol dependent individuals, anterior insula and anterior cingulate cortex morphometry was negatively correlated with trait impulsivity, decisional impulsivity, and compulsivity scores, indicating that the higher levels of impulsivity and compulsivity were associated with smaller volumes and thinner cortices.

4.1. Alcohol dependence and morphometry of salience network regions

ALC had smaller AI volume, but equivalent PI volume, compared to HC. This finding replicates our earlier work where manually traced AI volume differed between ALC and HC individuals (Senatorov et al., 2015), with a new sample of ALC and HC. ALC individuals also had smaller ACC volumes than HC. Further, we found between-group cortical thickness differences in the AI that were not present in the PI or ACC. Further, SN morphometry was associated with the alcohol dependence scale, indicating that those with more severe alcohol dependence symptoms had smaller volumes and thinner cortices. The AI appears to be more impacted by alcohol dependence than the ACC, as there were larger effect sizes for group differences and there were no cortical thickness group differences in the ACC (see Table 2). The lack of apparent group differences in ACC cortical thickness but significant differences in volume may be attributable to surface area, which was not examined in the current study. Cortical thickness is related to the number of neurons in a cortical column, while surface area reflects the number of cortical columns (Durazzo et al., 2011; Rakic, 1988). Cortical volume is the product of cortical thickness and surface area; therefore, the smaller volume in ALC in ACC may be due to decreases in surface area rather than cortical thickness. SN morphometry was not associated with abstinence duration, likely because of the very short abstinence duration present in the current ALC population (on average 2.5 weeks abstinent). Previous studies have reported increases in the volume of the insula and cingulate gyrus in abstinent ALCs after a period of 3 months (Demirakca et al., 2011).

One explanation for the localization of the morphological differences to the AI and ACC is the presence of von Economo neurons (VENs) in the AI and ACC. VENs are specialized neurons, located in the AI and limbic ACC, found only in some species of whales, great apes, and humans (Allman et al., 2010). VENs have been suggested to comprise the neuronal basis for the task-switching role of the SN (Sridharan et al., 2008). VENs have also been linked to several psychiatric disorders involving deficits in emotion regulation and social conduct, including autism, the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia, and schizophrenia (Butti et al., 2013). Emotion regulation is also deficient in ALC, particularly those in early abstinence (Fox et al., 2008), and the SN has been implicated in emotion regulation (Lindquist and Barrett, 2012). Our own work has shown a 60% reduction of VENs in the AI of ALC relative to HC (Senatorov et al., 2015). While the current study was unable to investigate VENs, our findings provide further support for the deleterious relationship between alcohol dependence and SN morphometry.

4.2. Impulsivity and morphometry of salience network regions

Consistent with previous literature, ALC scored higher on self-report trait impulsivity and demonstrated higher levels of discounting (decisional impulsivity), where they chose smaller, immediate reward over larger, delayed rewards at a greater rate (MacKillop et al., 2011; Mitchell et al., 2005). In ALC, both trait and decisional impulsivity were negatively correlated with AI volume and cortical thickness, and trait impulsivity was negatively correlated with ACC volume, indicating that higher levels of impulsivity were associated with smaller and thinner AI cortices and smaller ACC volumes. In HC, trait impulsivity was negatively associated with ACC volume and thickness, similarly indicating that higher trait impulsivity was associated with smaller and thinner ACC cortices. These findings are in line with preclinical work, where AI cortical thinness predicted higher levels of motor impulsivity (Belin-Rauscent et al., 2016). Other human studies have also reported an association between insula morphometry and impulsivity in individuals with addictive disorders. Previous studies have found negative associations between behavioral impulsivity and bilateral insula volume and trait impulsivity and right insula volume in cocaine dependent individuals (Ersche et al., 2011; Moreno-Lopez et al., 2012). Further, right AI volume was found to negatively correlate with behavioral impulsivity in ADHD individuals, a disorder where impulsivity is a core symptom (Lopez-Larson et al., 2012).

4.3. Compulsivity and morphometry of salience network regions

Consistent with previous studies, ALC also had higher compulsive drinking scores than HC (Myrick et al., 2004; Vollstadt-Klein et al., 2010). In ALC, compulsivity was negatively correlated with AI and ACC morphometry, indicating that higher compulsive drinking scores were associated with smaller AI and ACC volumes and thinner AI and ACC cortices. Our AI findings are supported by recent preclinical work, implicating the AI in compulsive drinking behaviors (Belin-Rauscent et al., 2016; Seif et al., 2013). Insular lesions are associated with a failure to adjust decisions based on potential aversive consequences, resulting in poor decision-making (Clark et al., 2008). Further, decreases in ACC and AI volume have also been reported in individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (de Wit et al., 2014). There were no associations between morphometry and compulsivity in HC, likely because of the low variability in scores in this group.

There is recent evidence that the AI plays a bidirectional role in compulsive drug intake. After drug taking is established AI lesions result in a long-lasting decrease in drug consumption. However, AI lesions occurring prior to drug intake result in a facilitation of loss of control over drug intake; animals with insula lesions prior to drug exposure experience an exacerbated escalation of drug taking (Rotge et al., 2017). It is possible that the abnormal AI morphometry seen in ALC may be a premorbid condition that resulted in an increased propensity to develop compulsive alcohol problems. Further, these results, as well as clinical lesion studies, indicate that the AI is a possible treatment target. Deep repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) of the insula has shown some promise as a treatment for nicotine addiction. Deep-TMS treatment significantly reduced cigarette consumption and nicotine dependence in heavy smokers (Dinur-Klein et al., 2014).

Both trait and decisional impulsivity were positively correlated with compulsive drinking scores. Belin and colleagues have suggested that there is a transition from impulsivity to compulsivity that occurs during the development of addictive disorders (Belin et al., 2008). In this continuum, high reactivity to novelty-seeking predicts the initiation of drug self-administration, while high levels of impulsivity predict escalation of drug use and the development of addiction-behavior, including compulsive (aversion-resistant) drug use (Belin et al., 2008). Drug use behavior itself may influence the transition from impulsivity to compulsivity through neurotoxic effects on “top-down” control regions, including cortical regions such as the ACC, resulting in worsened executive control over subcortical regions (Dalley et al., 2011). Further, impulsivity and compulsivity have been identified as potential endophenotypes for addictive disorders (Robbins et al., 2012). Biological non-drug using siblings of stimulant drug users show higher levels of self-report impulsivity (Ersche et al., 2010) and self-report compulsivity (Ersche et al., 2012b) compared to unrelated HC. Biological non-dependent siblings also show similar abnormalities in brain structure as their drug using siblings, which are related to deficits in inhibitory control (Ersche et al., 2012a). Higher scores on an impulsivity/compulsivity domain predicted escalated drinking patterns in young adult drinkers (Worhunsky et al., 2016). Future studies, investigating the causal relationship between impulsivity and compulsivity, structural alterations, and functional alterations of SN regions would provide valuable information and potential treatment targets for impulse control disorders.

4.4. Functional role of the salience network in impulsivity and compulsivity

While the current study did not evaluate the function of SN regions in impulsivity and compulsivity, it is important to consider this network’s function in ALC. Several studies have reported a hyperactive functional response to alcohol cues in the AI and ACC of ALC and problematic drinkers. ALC show increased activation in insular and anterior cingulate cortices in response to alcohol cues (Grusser et al., 2004; Myrick et al., 2004; Tapert et al., 2004). Further, alcohol cue-induced left AI hyperactivation predicted the transition from moderate to heavy drinking in young adults (Dager et al., 2014), while alcohol cue associated ACC hyperactivation was shown to predict treatment response (Grusser et al., 2004).

The AI and ACC have also been associated with impulsivity associated functional activation. In individuals with alcohol use disorder, risky decision making, a behavioral index of impulsivity and reward seeking, was associated with bilateral anterior insula activation (Claus and Hutchison, 2012). Individuals with high-risk alcoholism genotypes displayed increased insula activation to the anticipation of reward and loss, which was positively correlated with trait impulsivity (Villafuerte et al., 2012). Individuals with family history of alcohol dependence displayed increased ACC activation during risky decision making compared to family history negative individuals (Acheson et al., 2009). Furthermore, SN functional connectivity during rest predicted increased discounting of delayed rewards in healthy individuals (Li et al., 2013).

The AI and ACC have also been shown to be functionally altered in fMRI paradigms measuring aspects of compulsivity. Arcurio and colleagues investigated decision-making in the context of low and high risk decisions to drink and drive in ALC women (Arcurio et al., 2015). ALC women hyperactivated the AI when making compulsive, high-risk decisions, compared to low-risk decisions relative to HC women (Arcurio et al., 2015). In heavy drinkers, viewing alcohol cues activated the AI, and failures in control over drinking were positively correlated with bilateral insula and ACC activation (Claus et al., 2011).

4.5. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be noted. First, this study was cross-sectional in design, and cannot determine causality. It is possible that morphometric abnormalities exist prior to the onset of alcohol dependence and reflect a premorbid vulnerability to the development of alcohol misuse. Additionally, the ALC group was more heterogeneous than the HC group, particularly in their use of nicotine and the presence of Axis I diagnoses. While we did control for Axis I diagnoses, we were unable to control for smoking, as no HC were smokers. We did conduct a follow-up analysis to assess the effect of smoking in the ALC group alone, however larger studies will be required to fully disentangle the influence of smoking and comorbid Axis I disorders on brain structure, impulsivity and compulsivity measures, and the relationship between structure, impulsivity, and compulsivity. Future studies should also include a HC smoking group to better understand the role of nicotine dependence on these measures. Furthermore, impulsivity is a multi-faceted construct, which was not fully explored in this study. We evaluated one measure of self-report trait impulsivity using the BIS and one form of decisional impulsivity through the delay discounting task. There are many other measures of impulsivity, both trait and behavioral, and future studies will be required to investigate how these measures are associated with brain structure. Relatedly, compulsivity was only measured using a sub-scale from the OCDS, which is a self-report measure. Behavioral or task measures of compulsivity will be needed to further validate the relationship between SN structure and compulsivity. Finally, this study employed an ROI approach. It is highly unlikely that the AI and ACC are the only regions associated with impulsivity and compulsivity in alcohol addiction. Future studies should investigate these relationships with whole-brain approaches, such as voxel-based morphometry, to uncover these relationships.

Supplementary Material

Role of funding source

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest and have nothing to declare.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.06.014.

References

- Acheson A, Robinson JL, Glahn DC, Lovallo WR, Fox PT, 2009. Differential activation of the anterior cingulate cortex and caudate nucleus during a gambling simulation in persons with a family history of alcoholism: studies from the Oklahoma Family Health Patterns Project. Drug Alcohol Depend. 100, 17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman JM, Tetreault NA, Hakeem AY, Manaye KF, Semendeferi K, Erwin JM, Park S, Goubert V, Hof PR, 2010. The von Economo neurons in frontoinsular and anterior cingulate cortex in great apes and humans. Brain Struct. Funct. 214, 495–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham P, 1995. The Obsessive-Compulsive Drinking Scale – A self-rated instrument for the quantification of thoughts about alcohol and drinking behavior. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 19, 92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcurio LR, Finn PR, James TW, 2015. Neural mechanisms of high-risk decisions-to-drink in alcohol-dependent women. Addict. Biol 20, 390–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin D, Mar AC, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ, 2008. High impulsivity predicts the switch to compulsive cocaine-taking. Science 320, 1352–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin-Rauscent A, Daniel ML, Puaud M, Jupp B, Sawiak S, Howett D, McKenzie C, Caprioli D, Besson M, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ, Dalley JW, Belin D, 2016. From impulses to maladaptive actions: the insula is a neurobiological gate for the development of compulsive behavior. Mol. Psychiatry 21, 491–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butti C, Santos M, Uppal N, Hof PR, 2013. Von Economo neurons: Clinical and evolutionary perspectives. Cortex 49, 312–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Bechara A, Damasio H, Aitken MR, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW, 2008. Differential effects of insular and ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions on risky decision-making. Brain 131, 1311–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claus ED, Hutchison KE, 2012. Neural mechanisms of risk taking and relationships with hazardous drinking. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 36, 932–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claus ED, Ewing SW, Filbey FM, Sabbineni A, Hutchison KE, 2011. Identifying neurobiological phenotypes associated with alcohol use disorder severity. Neuropsychopharmacology 36, 2086–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J., 1998. Statiscal Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, N.J. [Google Scholar]

- Dager AD, Anderson BM, Rosen R, Khadka S, Sawyer B, Jiantonio-Kelly RE, Austad CS, Raskin SA, Tennen H, Wood RM, Fallahi CR, Pearlson GD, 2014. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) response to alcohol pictures predicts subsequent transition to heavy drinking in college students. Addiction 109, 585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW, 2011. Impulsivity, compulsivity, and top-down cognitive control. Neuron 69, 680–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirakca T, Ende G, Kammerer N, Welzel-Marquez H, Hermann D, Heinz A, Mann K, 2011. Effects of alcoholism and continued abstinence on brain volumes in both genders. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 35, 1678–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destrieux C, Fischl B, Dale A, Halgren E, 2010. Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. Neuroimage 53, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinur-Klein L, Dannon P, Hadar A, Rosenberg O, Roth Y, Kotler M, Zangen A, 2014. Smoking cessation induced by deep repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the prefrontal and insular cortices: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Biol. Psychiatry 76, 742–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Tosun D, Buckley S, Gazdzinski S, Mon A, Fryer SL, Meyerhoff DJ, 2011. Cortical thickness, surface area, and volume of the brain reward system in alcohol dependence: relationships to relapse and extended abstinence. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 35, 1187–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Mon A, Pennington D, Abe C, Gazdzinski S, Meyerhoff DJ, 2014. Interactive effects of chronic cigarette smoking and age on brain volumes in controls and alcohol-dependent individuals in early abstinence. Addict. Biol 19, 132–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersche KD, Turton AJ, Pradhan S, Bullmore ET, Robbins TW, 2010. Drug addiction endophenotypes: impulsive versus sensation-seeking personality traits. Biol. Psychiatry 68, 770–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersche KD, Barnes A, Jones PS, Morein-Zamir S, Robbins TW, Bullmore ET, 2011. Abnormal structure of frontostriatal brain systems is associated with aspects of impulsivity and compulsivity in cocaine dependence. Brain 134, 2013–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersche KD, Jones PS, Williams GB, Turton AJ, Robbins TW, Bullmore ET, 2012a. Abnormal brain structure implicated in stimulant drug addiction. Science 335, 601–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersche KD, Turton AJ, Chamberlain SR, Muller U, Bullmore ET, Robbins TW, 2012b. Cognitive dysfunction and anxious-impulsive personality traits are endophenotypes for drug dependence. Am. J. Psychiatry 169, 926–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams J, 1997. Structural Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-IV). Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Dale AM, 2000. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 97, 11050–11055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, van der Kouwe A, Destrieux C, Halgren E, Segonne F, Salat DH, Busa E, Seidman LJ, Goldstein J, Kennedy D, Caviness V, Makris N, Rosen B, Dale AM, 2004. Automatically parcellating the human cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex 14, 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Hong KA, Sinha R, 2008. Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control in recently abstinent alcoholics compared with social drinkers. Addict. Behav 33, 388–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General, O.o.t.S., 2016. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General's Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusser SM, Wrase J, Klein S, Hermann D, Smolka MN, Ruf M, Weber-Fahr W, Flor H, Mann K, Braus DF, Heinz A, 2004. Cue-induced activation of the striatum and medial prefrontal cortex is associated with subsequent relapse in abstinent alcoholics. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 175, 296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO, 1991. The fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the fagerstrom tolerance questionnaire. Br. J. Addict 86, 1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Ma N, Liu Y, He XS, Sun DL, Fu XM, Zhang X, Han S, Zhang DR, 2013. Resting-state functional connectivity predicts impulsivity in economic decision-making. J. Neurosci. 33, 4886–4895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist KA, Barrett LF, 2012. A functional architecture of the human brain: emerging insights from the science of emotion. Trends Cogn. Sci 16, 533–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Larson MP, King JB, Terry J, McGlade EC, Yurgelun-Todd D, 2012. Reduced insular volume in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Res. 204, 32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Amlung MT, Few LR, Ray LA, Sweet LH, Munafo MR, 2011. Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 216, 305–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris N, Oscar-Berman M, Jaffin SK, Hodge SM, Kennedy DN, Caviness VS, Marinkovic K, Breiter HC, Gasic GP, Harris GJ, 2008. Decreased volume of the brain reward system in alcoholism. Biol. Psychiatry 64, 192–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V, Uddin LQ, 2010. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct. Funct 214, 655–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, Fields HL, D'Esposito M, Boettiger CA, 2005. Impulsive responding in alcoholics. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 29, 2158–2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SH, 1999. Measures of impulsivity in cigarette smokers and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 146, 455–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller FG, Barratt ES, Dougherty DM, Schmitz JM, Swann AC, 2001. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. Am. J. Psychiatry 158, 1783–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momenan R, Steckler LE, Saad ZS, van Rafelghem S, Kerich MJ, Hommer DW, 2012. Effects of alcohol dependence on cortical thickness as determined by magnetic resonance imaging. Psychiatry Res. 204, 101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Lopez L, Catena A, Fernandez-Serrano MJ, Delgado-Rico E, Stamatakis EA, Perez-Garcia M, Verdejo-Garcia A, 2012. Trait impulsivity and prefrontal gray matter reductions in cocaine dependent individuals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 125, 208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir JL, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW, 1996. The cerebral cortex of the rat and visual attentional function: dissociable effects of mediofrontal, cingulate, anterior dorsolateral, and parietal cortex lesions on a five-choice serial reaction time task. Cereb. Cortex 6, 470–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrick H, Anton RF, Li X, Henderson S, Drobes D, Voronin K, George MS, 2004. Differential brain activity in alcoholics and social drinkers to alcohol cues: relationship to craving. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIDA, 2012. Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi NH, Rudrauf D, Damasio H, Bechara A, 2007. Damage to the insula disrupts addiction to cigarette smoking. Science 315, 531–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Wong MM, Martel MM, Jester JM, Puttler LI, Glass JM, Adams KM, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA, 2006. Poor response inhibition as a predictor of problem drinking and illicit drug use in adolescents at risk for alcoholism and other substance use disorders. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 45, 468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES, 1995. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J. Clin. Psychol 51, 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality C f.B.H.S.a., 2016. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Series H-51. [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P., 1988. Specification of cerebral cortical areas. Science 241, 170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Gillan CM, Smith DG, de Wit S, Ersche KD, 2012. Neurocognitive endophenotypes of impulsivity and compulsivity: towards dimensional psychiatry. Trends Cogn. Sci 16, 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotge J-Y, Cocker PJ, Daniel M-L, Belin-Rauscent A, Everitt BJ, Belin D, 2017. Bidirectional regulation over the development and expression of loss of control over cocaine intake by the anterior insula. Psychopharmacology 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M, 1993. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol Consumption-II. Addiction 88, 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seif T, Chang SJ, Simms JA, Gibb SL, Dadgar J, Chen BT, Harvey BK, Ron D, Messing RO, Bonci A, Hopf FW, 2013. Cortical activation of accumbens hyperpolarization-active NMDARs mediates aversion-resistant alcohol intake. Nat. Neurosci 16, 1094–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senatorov VV, Damadzic R, Mann CL, Schwandt ML, George DT, Hommer DW, Heilig M, Momenan R, 2015. Reduced anterior insula, enlarged amygdala in alcoholism and associated depleted von Economo neurons. Brain 138, 69–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Horn JL, 1984. Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS): User's Guide. Addiction Research Foundation, Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Brown J, Leo GI, Sobell MB, 1996. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug Alcohol Depend. 42, 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, 1983. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory STAI (form Y). [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan D, Levitin DJ, Menon V, 2008. A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 12569–12574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Brown GG, Baratta MV, Brown SA, 2004. fMRI BOLD response to alcohol stimuli in alcohol dependent young women. Addict. Behav 29, 33–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-Garcia A, Lawrence AJ, Clark L, 2008. Impulsivity as a vulnerability marker for substance-use disorders Review of findings from high-risk research, problem gamblers and genetic association studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 32, 777–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villafuerte S, Heitzeg MM, Foley S, Yau WY, Majczenko K, Zubieta JK, Zucker RA, Burmeister M, 2012. Impulsiveness and insula activation during reward anticipation are associated with genetic variants in GABRA2 in a family sample enriched for alcoholism. Mol. Psychiatry 17, 511–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollstadt-Klein S, Wichert S, Rabinstein J, Buhler M, Klein O, Ende G, Hermann D, Mann K, 2010. Initial, habitual and compulsive alcohol use is characterized by a shift of cue processing from ventral to dorsal striatum. Addiction 105, 1741–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worhunsky PD, Dager AD, Meda SA, Khadka S, Stevens MC, Austad CS, Raskin SA, Tennen H, Wood RM, Fallahi CR, Potenza MN, Pearlson GD, 2016. A preliminary prospective study of an escalation in ‘maximum daily drinks', fronto-parietal circuitry and impulsivity-related domains in young adult drinkers. Neuropsychopharmacology 41, 1637–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit SJ, Alonso P, Schweren L, Mataix-Cols D, Lochner C, Menchon JM, Stein DJ, Fouche JP, Soriano-Mas C, Sato JR, Hoexter MQ, Denys D, Nakamae T, Nishida S, Kwon JS, Jang JH, Busatto GF, Cardoner N, Cath DC, Fukui K, Jung WH, Kim SN, Miguel EC, Narumoto J, Phillips ML, Pujol J, Remijnse PL, Sakai Y, Shin NY, Yamada K, Veltman DJ, van den Heuvel OA, 2014. Multicenter voxel-based morphometry mega-analysis of structural brain scans in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 171, 340–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.