Abstract

Purpose:

Present a method to use change in phase in repeated Cartesian k-space measurements to monitor the change in magnetic field for dynamic MR temperature imaging.

Methods:

The method is applied to focused ultrasound heating experiments in a gelatin phantom and an ex vivo salt pork sample, without and with simulated respiratory motion.

Results:

In each experiment, phase variations due to field drift and respiration were readily apparent in the measured phase difference. With correction, the SD of the temperature over time was reduced from 0.18°C to 0.14°C (no breathing) and from 0.81°C to 0.22°C (with breathing) for the gelatin phantom, and from 0.68°C to 0.13°C (no breathing) and from 1.06°C to 0.17°C (with breathing) for the pork sample. The accuracy in nonheated regions, assessed as the RMS error deviation from 0°C, improved from 1.70°C to 1.11°C (no breathing) and from 4.73°C to 1.47°C (with breathing) for the gelatin phantom, and from 5.95°C to 0.88°C (no breathing) and from 13.40°C to 1.73°C (with breathing) for the pork sample. The correction did not affect the temperature measurement accuracy in the heated regions.

Conclusion:

This work demonstrates that phase changes resulting from variations in due to drift and respiration, commonly seen in MR thermometry applications, can be measured directly from 3D Cartesian acquisition methods. The correction of temporal field variations using the presented technique improved temperature accuracy, reduced variability in nonheated regions, and did not reduce accuracy in heated regions.

Keywords: MRI field drift monitoring, PRF temperature phase correction, respiration monitoring

1 |. INTRODUCTION

A number of dynamic MRI applications, such as proton resonant frequency (PRF) MR temperature imaging,1–5 MR velocity imaging,6–9 and spectroscopic imaging10 are based on accurate image phase measurements and are subject to error in the presence of field drift and susceptibility variations due to respiration and other body motions. Gradient and shim heating during imaging cause a susceptibility change in the metal and a change or drift in the magnetic field.11 Abdomen and lung motion with respiration can also cause change in the magnetic field, even when the motion itself is outside of the imaged volume such as for breast,12–16 brain, and spinal cord.17–21 Phase errors due to field changes can cause ghosting and other artifacts in all types of images and image-acquisition methods and errors in measured temperatures in PRF image acquisitions.13,16,17,21–24

For slow field variations it may be sufficient to correct the phase of each image in the sequence. Drifts in , the main magnetic field, can be corrected by updating the resonance frequency in real time.25,26 Variations due to respiration have been corrected by measuring the field variations at end inspiration and end expiration and then monitoring the respiratory motion in real time optically or with respiratory bellows.18,19 Complicated variations have been estimated from phase difference measurements27 and physical models and corrected in real time with high-order shim arrays.28 Dynamic 3D field maps have been interleaved with functional MRI and other dynamic sequences to provide more accurate spatially variant corrections.11,20 For MR temperature imaging, in which baseline image subtraction is needed in the presence of field changes due to cyclic physiological motion, the problem can be addressed by acquiring multiple baselines before heating and then matching each acquired dynamic frame to the geometrically registered baseline for subtraction.13,23,29,30 Field drift and variations due to respiration can also be measured and corrected using referenceless subtraction of temperature measurements in an unheated region.14,31 In MR temperature imaging in the breast, multi-echo image acquisitions have been used to obtain local variation in in fat and then extrapolating these field variations into glandular tissue.16

Several types of navigator echo measurements have been developed to measure phase variations during imaging.17,32–35 Some navigator methods acquire very short FID signals before36 and/or after each set of k-space measurements.15,37,38 These FID navigators have been combined with coil sensitivity profiles to obtain spatial variation in the measured drift.39

In Cartesian sequences, a central line has periodically been acquired to measure a respiratory-induced phase change,40,41 as is done in radial sequences in which the center of k-space from each view can be used for very high temporal resolution corrections, as all views typically sample the center of k-space.42

All these methods of monitoring and correcting k-space require some form of additional information or measurements that must be obtained in addition to the image data. To eliminate that need, Manduca et al proposed an autofocusing method that explores possible motion adjustments to k-space to find the set of motions that minimize image artifact and ghosting.43 For a sequence of fast low angle shot images in a functional MRI study of stimulation of the visual cortex, Wowk et al proposed to simply monitor the phase variation of each point in k-space over time.44 With the assumption that field drift and physiological motion causes a time-varying change in the phase of each k-space point from the true phase of that point, they demonstrated that phase changes due to respiration and cardiac motion could be measured directly from the k-space measurements in a sequence of images. In the absence of field drift or respiration, the phase of each point in k-space will be the same from one image to the next. The technique was applied to a 2D fast low angle shot acquisition, and signals < 1% of the k-spacemaximum were not measured. Apparent respiration and cardiac pulsation signals were separated using appropriate bandpass filters.

In this work, we extend the concept proposed by Wowk to 3D Cartesian imaging and provide a justification for an improved implementation and form of analysis. We provide a demonstration using MR thermometry data that the presented method can be used to track phase changes due to respiration and other physiological motions, as well as magnetic field drift. We also demonstrate that corrections based on the measured field drift can improve measurement precision and accuracy.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. THEORY

In MR, the magnetization components in the plane perpendicular to the magnetic field are often expressed as real and imaginary components in the complex plane to conveniently describe their precession. In MRI, the received signal is typically expressed as the integral over all space in terms of the product of the complex sensitivity of the receiver coil, , with the complex magnetization in the transverse plane at the time of signal sampling. Here we assume that the phase of the complex coil sensitivity is constant in time and slowly varying in space. We consider just one receive coil initially and generalize to multiple coilslater. For convenience, we express separately the magnitude and phase of the magnetization, and , respectively. The signal becomes15

| (1) |

where is the actual time of the signal measurement, and is the phase of the magnetization at the time,. For the image in a dynamic sequence, the tissue phase at the time after the excitation can be written as

| (2) |

where is the phase induced by the imaging gradients for the k-space sample of the excitation, and is the phase of the magnetization as a function of position due to everything else:

| (3a) |

where the negative signs indicate a clockwise rotation due to the magnetic field, and is therefore the phase of the magnetization contributing to the measured signal in the absence of imaging gradients at the time after the excitation in the image (see Figure 1). We assume that (1) the RF pulse induces a phase distribution that is the same for every excitation and will be removed on subtraction; (2) the magnetic field can be separated into a constant part, , and one that changes or drifts with respiration and time,; (3) the field variation in time is small between excitations and changes little over the time, , from RF excitation to signal measurement; and (4) the effects of relaxation will not affect our phase measurement.

FIGURE 1.

Segmented EPI sequence and definition of , , and

The phase due to field drift can then be written as

| (3b) |

Note that depends on both the absolute time of the excitation, , and the time after the RF pulse to the sample,.

The existence of the time-varying term can be a source of ghosting and other artifacts in the MR images and can cause systematic errors in PRF temperature measurements. The primary purpose of this paper is to assess the extent to which this temporal variation in the field can be determined from the k-space measurements themselves. It has long been known that estimates of the magnetic field and changes due to respiration and drift can be measured from points acquired at the center of k-space, where the signal is strong relative to noise and where the measurement is not affected by phase encoding. In many 2D and 3D non-Cartesian sequences, the center of k-space is sampled with every RF excitation, allowing nearly continuous measurement of the drift. In hybrid 2D radial/1D Cartesian sequences, the center of k-space is sampled less often. The 3D Cartesian sequences typically sample the center of k-space only once per image volume. The work of this paper was intended to assess the extent to which the field drift could be measured from noncentral points in Cartesian sequences.

Where noise can be neglected, we assume that the k-space phase for the k-space measurement of the excitation is the same for the corresponding measurement in each image in the dynamic acquisition. The k-space measurement for the RF excitation in the dynamic image is then

| (4) |

where, for convenience, we omit the temporal variation in the magnetization magnitude. When noise is considered, the effect of signal decay is also implicitly treated. Note that the actual order of k-space encoding is not important, but only the requirement that the same order be used for each image in the sequence. Consider first the simple case when is not a function of position. In this case it can be taken out of the integral as follows:

| (5) |

In this case, none of the terms in the integral is a function of the absolute time . If the first image does not experience significant field drift, it could serve as a baseline image from which the proposed phase difference measurements could be made. This baseline signal would be

| (6) |

Each k-space measurement, in turn, has a phase and magnitude, and if there are no terms that vary with absolute time, then the repeated scans of a dynamic acquisition will have the same phase and magnitude. When field drift occurs, but is not too large (baseline phase drift ), it is possible to average corresponding points of the k-spaces from multiple images in a sequence to obtain an effective baseline k-space and an effective baseline field that varies with the excitation indices of a single image acquisition. Note that, after averaging, the effective field drift in the baseline image will be about the same as the field drift during the k-space acquisition of a single image. The baseline k-space becomes

| (7) |

The field drift can be measured from the complex phase difference of each k-space measurement with a corresponding baseline k-space measurement

| (8a) |

where extracts the phase from the complex argument. Although the baseline k-space is obtained from averaging corresponding k-space points over multiple acquisitions, the phase range of will always average to the phase range of the field variation in a single image acquisition. If needed, that phase range can be estimated and corrected. In an ideal world, the baseline k-space could simply be the k-space of the first image acquired. However, it is likely that all images in a sequence will have some corruption due to thermal noise and patient motion during acquisition. To reduce the possibility of phase wraparound, Equation (8a) is implemented as follows:

| (8b) |

Because the phase difference is small between adjacent points in time, the phase wrap-around effects discussed by Wowk are rarely a problem.

Thermal noise in the signal of Equation (1) results in an additive variance in the measured k-space phase. In the presence of noise, the noisy signal measured, , can be written as follows:

| (9) |

The term, , represents thermal noise from all sources that affect the complex signal measurements. The noise in the background image can be reduced by averaging the complex signal over multiple time frames. The net effect will be a baseline phase that may be different from the first k-space phase, but the variation due to noise will be greatly reduced. For high SNRs , the SD in the phase of the signal, is proportional to 1/SNR, as follows:

| (10) |

For smaller SNR values , the random variations overlap zero and the variance approaches or , as shown in Figure 2. Note that the linear relationship is valid down to an SNR of about 5. In regions of k-space where the signal is very close to zero (much lower than ), the measured signal is just noise and the phase measurement, itself, is meaningless. For those points in k-space where the measured signal, , in Equation (9) is sufficiently strong relative to measurement noise, the field drift estimate obtained in Equation (8) will be related to the true field drift with some added error due to the thermal noise. We assume that the expected noise power is the same for all points in k-space and that the k-space magnitude is independent of image number ( for all ), as follows:

| (11a) |

Or

| (11b) |

FIGURE 2.

Standard deviation in phase versus 1/SNR. The deviation from linear and saturation occurs at about an and below

Where the signal is large relative to the noise, the phase measured from Equation (11b) will equal the desired phase. When the signal is not large, the noise will corrupt the phase measurement. However, we assume the thermal noise is zero mean and all the terms containing noise will reduce with averaging.

The equations to this point provide a basis for a method, such as that of Wowk et al, to measure field drift from k-space measurements. For fast imaging methods, the SNR may be very low for individual k-space measurements. Because the magnetic field will likely change very little, if at all, during readout of a single k-space line, a single measurement of can be obtained as a weighted average of the complex phase difference values obtained from that k-space line. For simplicity, we redefine as the time from RF excitation to the center of the echo in the segmented EPI echo train, and as the readout sample index. We define , and to avoid aliasing, we perform the weighted average over . We perform a least squares analysis to find the weights, , for each readout point,. The averaged normalized complex phase difference, , becomes

| (12) |

The subscript on the complex phase difference term reflects the fact that the phase due to evolves with the readout time and, in principle, should be corrected for this evolution:

| (13) |

The field is obtained from the phase angle of

| (14) |

The weights, , are then chosen to give a minimum variance in the measured field:

| (15) |

Using Equation (12), the variance for each point, , in time can be written as

| (16) |

where is the “expectation” operation, and the dummy index is used to differentiate from when the summations are combined in the next step. Recognizing that the noise is zero mean, independent of time, and uncorrelated between different samples in time, this reduces to

| (17) |

where the approximation holds when the SNR for the point is greater than about 4 or 5.

| (18) |

Minimizing the ratio gives

| (19) |

| (20) |

Thus, the minimum variance average is obtained by simply averaging the complex phase difference measurements as follows:

| (21) |

And the minimum variance becomes

| (22) |

2.2 |. Data acquisition

Data were obtained using a gelatin phantom45 and a salt pork meat sample (obtained from a local grocery store) containing both fat and aqueous tissues,15 in conjunction with heating in a breast-specific MRI-guided focused ultrasound system (see Figure 3). All experiments were performed in a 3T MRI scanner (TIM Trio; Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) using a breast-specific MRgFUS system with an integrated eight-channel RF coil and an MRI-compatible phased array transducer (256 elements; 0.94-MHz frequency, 10 cm radius of curvature [Imasonic, Besançon, France] and Image Guided Therapy [Pessac, France]).46 The transducer was coupled with the phantom and salt pork with a bath of deionized, degassed water. Respiration effects were simulated with a male volunteer breathing freely while lying prone above the device on top of the suspended phantom and salt pork. During heating with the MRgFUS system, dynamic temperature imaging was performed to test temperature measurements without and with the volunteer on top of the setup. The 3D imaging volume was prescribed in a coronal orientation using a 3D gradient-recalled echo segmented EPI pulse sequence with monopolar (ie, flyback) readout and no fat saturation (voxel resolution = 1.0×1.0×2.4mm, FOV = 224×154×24mm, matrix = 224×154×10, TR/TE = 32/15ms, flip angle = 20°, EPI factor = 7, 8 slices with 25% oversampling, readout bandwidth = 744Hz/Px, expressed as echo in echo train within within . With EPI factor = 7, is divided into seven segments, with one segment sampled by each echo in the echo train. The same set of encodings is used while all encodings are acquired. After all encodings are acquired, the encodings are incremented and the process continued until all are acquired. With 7 echoes in each echo train, each experiment has 154 encodings (7 echoes/echo train×22 echo trains), 10 encodings, and 20 or 25 dynamic images in the gelatin phantom or salt pork sample, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Coronal -weighted views of the gelatin phantom (A) ex vivo salt pork sample (B) in the breast-specific MR-guided focused system. The position of the focused ultrasound transducer is shown with white, dashed lines indicating the acoustic beam path. The volunteer is positioned on top of the system (ie, out of the plane)

Two sets of data were acquired and analyzed for both the gelatin phantom and the salt pork sample. The first image sets provided a baseline of the MRgFUS heating (25 acoustic W,60s) without the breathing artifact. The second image sets repeated the imaging with the volunteer above freely breathing, simulating respiration effects. The PRF temperatures were determined using the average phase of five baseline images obtained with no ultrasound heating as the reference phase and assuming a PRF coefficient .

2.3 |. Data analysis

For this study, the phase drift was determined in a logical sequence of steps. First, a baseline k-space was created by averaging the k-space measurements over the acquisition index. Averaging both over the first five baseline acquisitions (ie, before ultrasound was applied) and overall acquisitions were tested. Both methods gave similar results, and, except for Figure 4C where all 20 were used, only the averaging over the first five acquisitions with no heating is shown in this paper, as it provides a more realistic case for real-time applications. A complex phase-difference k-space sequence was obtained as the pointwise complex phase difference of each k-space volume with the baseline:

| (23) |

where the coil index is again used. Note that . Furthermore, assuming that the field changes little over the time of a single readout and is the same for each RF coil used, was averaged over all readout points, , in each line of k-space and over all coils, , as follows:

| (24) |

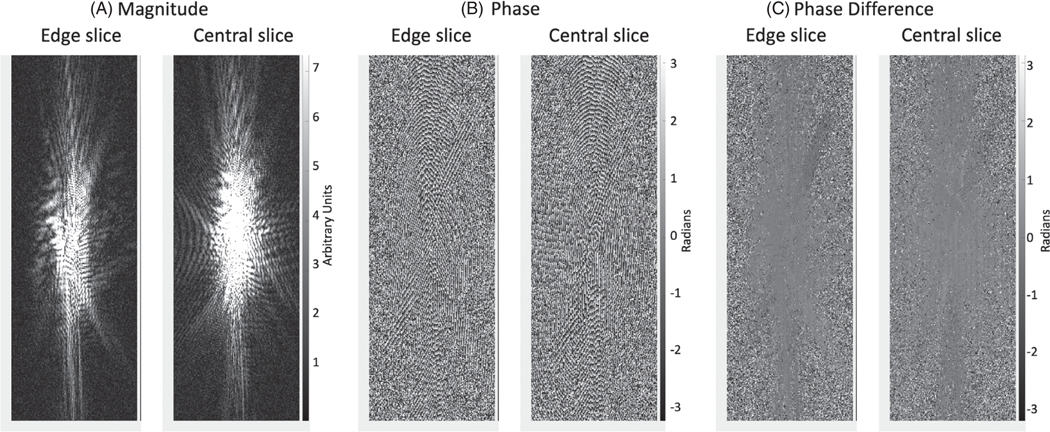

FIGURE 4.

Data from the edge and central planes of k-space from a 10-slice 3D segmented EPI phantom study. A, k-Space magnitude scaled to show signal at edges. B, k-Space phase. C, Phase of complex phase difference between current time frame and time average of 20 time frames in the dynamic sequence

Note that has magnitude equal to the original magnitude of squared, ensuring that points with the strongest magnitude are preferentially (and optimally, according to Equation [20]) weighted in the average. For drift correction, the phase drifts obtained from these averaged values were subtracted from the corresponding dynamic k-space measurements as follows:

| (25) |

Finally, the assumption that the field drift, , changes very little between excitations, suggests determining the field drift from a fit to the phase difference of the echoes in the echo train. We therefore compare obtaining the phase estimate from a least-squares fit to the phase differences of the echoes in the echo train, and compare the central value of the fitted phase to the value of the phase at the central echo.

2.4 |. Evaluation

The effectiveness of correction was measured in terms of the SD and RMS error (RMSE) of the calculated temperature over time in regions of no temperature change. The effect of the correction on temperature measurement was evaluated by directly comparing the temperature of the hottest point with and without correction.

To further verify the phase information, the estimates of phase drift were sorted in the order of acquisition (increasing ) and plotted. Two methods were used to obtain the estimate of phase drift for plotting: (1) Phase was measured directly at the TE at the middle echo of each echo train, and (2) the multiple echoes in each echo train were fitted to a line, and the phase value at the time of the central echo was taken. We tested a third method in which phase was obtained from the slope of the fitted line, but this was less precise then method (2), and for clarity we have not included it in these results. Field drift was derived from phase drift as in Equation (8).

3 |. RESULTS

Results are provided to illustrate the various stages of the measurement and correction methods. Figure 4 shows the magnitude and phase of k-space data from the edge and central slices of the k-space from the gelatin phantom with volunteer positioned above. In Figure 4A, the magnitude is shown with scaling to illustrate the extension of the k-space signal above the noise floor. In Figure 4B, the phase is shown to vary rapidly with position in k-space, as expected for a typical object. In Figure 4C, the phase after taking the complex phase difference with the time-average k-space from the baseline measurements is shown, and demonstrates that for regions with strong signal, the phase shows very little change with k-space position.

Figure 5 shows the phase obtained from the complex phase difference between the current k-space points and the corresponding baseline k-space points. This complex phase-difference k-space (Equation [8]) is averaged over and coil before taking the phase of the result. The phase is shown in the order of vertically and horizontally, as indicated. The phase from the field drift and respiration for each image is the narrow rectangle, as indicated. This rectangular display of phase is repeated for each k-space set acquired in the image sequence. This is shown for the four experiments analyzed. Figure 5A,B is from the gelatin phantom, and Figure 5C,D is from the salt pork. Figure 5B,D is with the volunteer lying above, breathing.

FIGURE 5.

The phase of the complex phase difference k-space after averaging over the readout samples and over all coils as described in Equations (21) and (23). Each rectangle shows the phase evolution over the time of a complete image volume. This image volume is replicated over time. (Note: A column of zeros is inserted between every block of measurements to assist in visualization.) A,B, The gelatin phantom. C,D, The ex vivo salt pork sample. B,D, A breathing volunteer lying above the phantom. The volunteer is outside of the image FOV but contributes a respiratory phase

To provide a view of the phase in time order, Figure 6 shows the phase from the 7 echoes of each of the 22 echo trains in each time frame, with 20 time frames for the gelatin phantom and 25 time frames for the salt pork sample. The phase due to respiration in Figure 6B,D is clearly seen. Only the central measurements are shown.

FIGURE 6.

The phase measurements due to field drift and respiration sorted in time order from the four experiments. In each rectangle, the measurements vertically are from the echo train, showing the phase evolution during the 7 encodings of each echo train in these studies, and the measurements horizontally are the 22 sets of echo trains. For these images, phase evolution with is not shown

The actual field measurements for all points in time order, after averaging the phase difference over readout and coil, are given in Supporting Information Figures S1–S3. Supporting Information Figure S1 gives a detailed description of the order of acquisition for the first five frames. Supporting Information Figure S2 gives the complete set of field drift measurements for all four experiments, averaging over the first 5 frames to obtain the baseline. Supporting Information Figure S3 gives the corresponding complete set of field drift measurements, averaging over all time frames to obtain the baseline. With the improvement in baseline SNR, there is a visible reduction in error for the outer regions of ky and kz. Supporting Information Figure S4 repeats Figure 5, averaging over all images for the baseline.

The measured field obtained from the phase measurements at the center of each echo train as a function of k-space measurement number through time is shown in Figure 7. Clear phase drifts over time can be seen in the salt pork experiments, and the respiratory cycle is clearly seen in Figure 7B,D when the volunteer was on top of the setup. For ease of comparison, the same scale is used for each plot.

FIGURE 7.

Change in (in Tesla) as a function of time for the four experiments. A,B, The gelatin phantom heating study. C,D, The heating of the ex vivo salt pork sample. A,C, With no breathing human. B,D, A breathing human above the phantom/sample. Measurements are shown for the central plane

The SD and RMSE of the measured temperatures, without and with the corrections of Equations (11) and (12) for the four experiments, are shown in Figure 8. For the cases shown in Figure 8B,D, which include a breathing volunteer, there is a substantial reduction in the observed ghosting artifact. The improved accuracy and precision of the temperature measurements is indicated by the SD and RMSE measurements in Figure 9. Note that the method reduces RMSE substantially, but does not completely remove the offset or bias, which remains as a systematic error.

FIGURE 8.

The SD and RMS error (RMSE; in °C) over time for each image voxel for the four experiments. A,B, The gelatin phantom heating study. C,D, The heating of the ex vivo salt pork sample. A,C, No breathing human. B,D, A breathing human above the phantom. In each row, the first and second image are the SD of the uncorrected and corrected temperature images, respectively, and the third and fourth images are the RMSE of the temperature images without and with correction. The yellow rectangle in the first image shows the region of interest used for obtaining the average and SD of the SD and RMSE measurements

FIGURE 9.

Bar chart of average SD and RMSE in time of the temperature measurements without and with corrections shown in Figure 8 for the four experiments. The measurements are averaged over the regions indicated in Figure 8. The SD of the measurements over the rectangle are plotted as the error bars

Finally, plots of the temperature at the hottest point and at a point away from the heating are shown in Figure 10A–D, and in a 3×3 region of interest around those points in Figure 10E–H. This illustrates that these correction methods correct for the field drift but do not remove the heating at the focus.

FIGURE 10.

Temperature measurements versus time for the four experiments. A–D, top row: The temperature at the hottest point (solid lines) and a background point (dashed lines), with and without correction for the four experiments. E–H, bottom row: The average temperature in a 3×3 region of interest (ROI) around the hottest and background points

4 |. DISCUSSION

This study has demonstrated a method to obtain direct measurement of variation in the magnetic field due to field drift, respiration, and other motions from the k-space measurements themselves. The method can achieve measurements synchronous with each RF excitation pulse, as was done with the navigator echo method presented previously.15 In our initial experience, it is easily applied to any MRI acquisition, and can be applied retrospectively to retrieve respiratory signal and field drift measurements.

The method that we present extends the k-space phase-difference method proposed initially by Wowk et al.44 They developed the method for sequential 2D fast low angle shot images, and measured the phase changes for corresponding k-space points as a function of time during image acquisition. Areas of low signal magnitude (<1% of the maximum k-space signal) were not measured. We extend the method to dynamic 3D Cartesian gradient-echo acquisitions, in which phase is used for temperature measurements. The complex phase-difference method used here, as detailed in Equation (8), is much less sensitive to wrap-around than the direct phase subtraction method of Wowk. Furthermore, we derive weights for optimally combining the complex phase-difference measurements to ensure that adequate measurements are obtained with the desired temporal frequency. Finally, we evaluate the method in a new application, MR thermometry.

The phase-difference measurements of Figure 5 show an artifact for the edges of kz for low values of ky. This artifact does not occur for the first five images, which were used in determining the baseline, nor does the artifact show when all images were averaged to form the baseline (see Supporting Information Figures S3 and S4).

Because this method is applied directly to the acquired k-space data, no change is required in acquisition method. On the other hand, if desired, it can be applied in conjunction with navigator echoes or any other field-monitoring method.

There are a number of limitations in the current method. As is the case with other field-monitoring methods, this method cannot eliminate all artifacts due to motion or field drift and will likely fail when substantial motion occurs within the acquisition of a single image volume. As configured at this time, the drift is assumed to be uniform across the image, when in fact the field variations can be highly localized and nonuniform spatially. Because of the placement of the passive shims in the gradients circumferentially around the scanner bore, the heating and change in the susceptibility is relatively uniform around the bore, and the field change due to heating of the shims is very uniform throughout the imaging volume. Although it is likely that the field variations due to respiration are less spatially uniform, the experiments that we performed showed that artifacts due to such variations, when the motion is outside of the imaging volume, can be greatly reduced. When applied to temperature measurements for MRI-guided focused ultrasound systems that use water as a coupling medium, as was done in this work, it is likely that water motion may produce phase variations that are unrelated to respiration and body motions. Second, the method will only work for k-space points with sufficient signal strength relative to the measurement noise. It would appear that averaging k-space measurements that have an SNR greater than 5 will result in normal SNR improvement, whereas points with lower SNR will provide less useful phase information. Thus, although it is technically feasible to find the field offset at the time of each measured signal, points at the edges of k-space in any direction may not provide any useful phase information. Furthermore, this method assumes that the average over time will provide the least artifactual set of k-space measurements, which can then be used to find the relative drift.

There are a number of enhancements that can be investigated to overcome some of the limitations as well as investigate new potential. Because field variations are often spatially nonuniform, methods to obtain estimates of the spatial variation should be investigated. Instead of averaging over coil channels, it would be possible to determine the field offset for each channel and combine these offsets in a manner using the spatial distribution of the sensitivity volumes.39

This work was intended to define the method, demonstrate the measurements that can be obtained, and determine the effects of correction. We have limited the application to the phantom studies with and without breathing to illustrate the ability to detect the variations due to respiration and to test the effect of the correction on the accuracy of temperature measurements. Although it might be expected that this type of phase correction could adversely affect point heating measurements, such an adverse effect was not observed.

Further studies are warranted to investigate the application in other situations and other pulse sequences. It is likely that the proposed method could improve the performance of other applications that require dynamic sequences of images, such as functional MRI and dynamic flow measurements, using phase-contrast methods. This method also remains to be tested in applications that simply experience ghosting in magnitude images due to respiration and other motions. It would be interesting to compare these field variation measurements with navigator echoes and other methods used to monitor field drift. It will be important to test this method for many other types of acquisition, including non-Cartesian methods. Because of the generalized weighting developed, it is likely that this method could be applied to many other types of acquisitions and applications.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

The generalized method presented in this work has demonstrated a very robust ability to monitor phase changes due to field variations caused by respiration, motion, and other forms of field drift. The correction based on these field drift measurements was shown to greatly reduce phase measurement error and to increase measurement precision. For the phantom models studied in this work, the presented correction method does not adversely affect temperature measurement accuracy.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. The phase-difference measurements for the first five images of the phantom with breathing, sorted in acquisition time order (top to bottom then left to right)

Figure S2. The field drift, , measurements for the four studies in this paper sorted in acquisition time order (top to bottom, then left to right). The baseline image is obtained from the complex average over the first five frames before application of focused ultrasound

Figure S3. The phase of the averaged complex phase difference k-space as described in Figure 5. A,B, Gelatin phantom. C,D, Ex vivo salt pork sample. B,D, Volunteer lying above the phantom. The volunteer is outside of the image FOV but contributes a respiratory phase

Figure S4. The field drift, , measurements for the four studies in this paper sorted in acquisition time order (top to bottom, then left to right). The baseline image is obtained from the complex average over all 20 or 25 frames in the dynamic sequence

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge contributions from John Roberts and other members of the University of Utah Focused Ultrasound Laboratory.

Funding information

National Institutes of Health (R01EB028316, R37CA224141, and R03EB029204) and the Mark H. Huntsman Endowed Chair. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of the article at the publisher’s website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geiger J, Markl M, Herzer L, et al. Aortic flow patterns in patients with Marfan syndrome assessed by flow-sensitive four-dimensional MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;35:594–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kecskemeti S, Johnson K, Wu Y, Mistretta C, Turski P, Wieben O. High resolution three-dimensional cine phase contrast MRI of small intracranial aneurysms using a stack of stars k-space trajectory. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;35:518–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim D, Dyvorne HA, Otazo R, Feng L, Sodickson DK, Lee VS. Accelerated phase-contrast cine MRI using k-t SPARSE-SENSE. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:1054–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markl M, Frydrychowicz A, Kozerke S, Hope M, Wieben O. 4D flow MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;36:1015–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zwart NR, Pipe JG. Multidirectional high-moment encoding in phase contrast MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:1553–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Senneville BD, Roujol S, Jais P, Moonen CT, Herigault G, Quesson B. Feasibility of fast MR-thermometry during cardiac radiofrequency ablation. NMR Biomed. 2012;25: 556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diakite M, Payne A, Todd N, Parker DL. Irreversible change in the T1 temperature dependence with thermal dose using the proton resonance frequency-T1 technique. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:1122–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Todd N, Diakite M, Payne A, Parker DL. Hybrid proton resonance frequency/T1 technique for simultaneous temperature monitoring in adipose and aqueous tissues. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogl TJ, Huebner F, Naguib NN, et al. MR-based thermometry of laser induced thermotherapy: temperature accuracy and temporal resolution in vitro at 0.2 and 1.5 T magnetic field strengths. Lasers Surg Med. 2012;44:257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tal A, Gonen O. Localization errors in MR spectroscopic imaging due to the drift of the main magnetic field and their correction. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70:895–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lange T, Zaitsev M, Buechert M. Correction of frequency drifts induced by gradient heating in 1H spectra using interleaved reference spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011; 33:748–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolan PJ, Henry PG, Baker EH, Meisamy S, Garwood M. Measurement and correction of respiration-induced B0 variations in breast 1H MRS at 4 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52: 1239–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hey S, Maclair G, de Senneville BD, et al. Online correction of respiratory-induced field disturbances for continuous MR-thermometry in the breast. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:1494–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kickhefel A, Rosenberg C, Roland J, et al. A pilot study for clinical feasibility of the near-harmonic 2D referenceless PRFS thermometry in liver under free breathing using MR-guided LITT ablation data. Int J Hyperthermia. 2012;28:250–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svedin BT, Payne A, Parker DL. Respiration artifact correction in three-dimensional proton resonance frequency MR thermometry using phase navigators. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76:206–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wyatt CR, Soher BJ, MacFall JR. Correction of breathing-induced errors in magnetic resonance thermometry of hyperthermia using multiecho field fitting techniques. Med Phys. 2010;37:6300–6309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van de Moortele PF, Pfeuffer J, Glover GH, Ugurbil K, Hu X. Respiration-induced B0 fluctuations and their spatial distribution in the human brain at 7 tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:888–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Gelderen P, de Zwart JA, Starewicz P, Hinks RS, Duyn JH. Real-time shimming to compensate for respiration-induced B0 fluctuations. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:362–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verma T, Cohen-Adad J. Effect of respiration on the B0 field in the human spinal cord at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72:1629–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zahneisen B, Asslander J, LeVan P, et al. Quantification and correction of respiration induced dynamic field map changes in fMRI using 3D single shot techniques. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71:1093–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters K, Weiss K, Maintz D, Giese D. Influence of respiration-induced B0 variations in real-time phase-contrast echo planar imaging of the cervical cerebrospinal fluid. Magn Reson Med. 2019;82:647–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raj D, Paley DP, Anderson AW, Kennan RP, Gore JC. A model for susceptibility artefacts from respiration in functional echo-planar magnetic resonance imaging. Phys Med Biol. 2000;45:3809–3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shmatukha AV, Bakker CJ. Correction of proton resonance frequency shift temperature maps for magnetic field disturbances caused by breathing. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51:4689–4705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vigen KK, Daniel BL, Pauly JM, Butts K. Triggered, navigated, multi-baseline method for proton resonance frequency temperature mapping with respiratory motion. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:1003–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J, Santos JM, Conolly SM, Miller KL, Hargreaves BA, Pauly JM. Respiration-induced B0 field fluctuation compensation in balanced SSFP: real-time approach for transition-band SSFP fMRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:1197–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bing C, Staruch RM, Tillander M, et al. Drift correction for accurate PRF-shift MR thermometry during mild hyperthermia treatments with MR-HIFU. Int J Hyperthermia. 2016;32:673–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu M, Mulder HT, Baron P, et al. Correction of motion-induced susceptibility artifacts and B0 drift during proton resonance frequency shift-based MR thermometry in the pelvis with background field removal methods. Magn Reson Med. 2020;84:2495–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Topfer R, Foias A, Stikov N, Cohen-Adad J. Real-time correction of respiration-induced distortions in the human spinal cord using a 24-channel shim array. Magn Reson Med. 2018;80:935–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deckers R, Merckel LG, Denis de Senneville B, et al. Performance analysis of a dedicated breast MR-HIFU system for tumor ablation in breast cancer patients. Phys Med Biol. 2015;60:5527–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grissom WA, Rieke V, Holbrook AB, et al. Hybrid referenceless and multibaseline subtraction MR thermometry for monitoring thermal therapies in moving organs. Med Phys. 2010; 37: 5014–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zou C, Tie C, Pan M, et al. Referenceless MR thermometry—a comparison of five methods. Phys Med Biol. 2017;62:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ordidge RJ, Helpern JA, Qing ZX, Knight RA, Nagesh V. Correction of motional artifacts in diffusion-weighted MR images using navigator echoes. Magn Reson Imaging. 1994;12:455–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu HL, Kochunov P, Lancaster JL, Fox PT, Gao JH. Comparison of navigator echo and centroid corrections of image displacement induced by static magnetic field drift on echo planar functional MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13: 308–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, Rossman PJ, Grimm RC, Riederer SJ, Ehman RL. Navigator-echo-based real-time respiratory gating and triggering for reduction of respiration effects in three-dimensional coronary MR angiography. Radiology. 1996;198:55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Wang Y, Jiang Y, Xie H, Li G. Image correction during large and rapid B(0) variations in an open MRI system with permanent magnets using navigator echoes and phase compensation. Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;27:988–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu X, Kim SG. Reduction of signal fluctuation in functional MRI using navigator echoes. Magn Reson Med. 1994;31:495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crowe ME, Larson AC, Zhang Q, et al. Automated rectilinear self-gated cardiac cine imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:782–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le TH, Hu X. Retrospective estimation and correction of physiological artifacts in fMRI by direct extraction of physiological activity from MR data. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:290–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrer CJ, Bartels LW, van der Velden TA, et al. Field drift correction of proton resonance frequency shift temperature mapping with multichannel fast alternating nonselective free induction decay readouts. Magn Reson Med. 2020;83:962–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kustner T, Wurslin C, Schwartz M, et al. Self-navigated 4D Cartesian imaging of periodic motion in the body trunk using partial k-space compressed sensing. Magn Reson Med. 2017;78:632–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Durand E, van de Moortele PF, Pachot-Clouard M, Le Bihan D. Artifact due to B(0) fluctuations in fMRI: correction using the k-space central line. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:198–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Svedin BT, Payne A, Bolster BD Jr, Parker DL. Multiecho pseudo-golden angle stack of stars thermometry with high spatial and temporal resolution using k-space weighted image contrast. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79:1407–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manduca A, McGee KP, Welch EB, Felmlee JP, Grimm RC, Ehman RL. Autocorrection in MR imaging: adaptive motion correction without navigator echoes. Radiology. 2000; 215:904–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wowk B, McIntyre MC, Saunders JK. k-Space detection and correction of physiological artifacts in fMRI. Magn Reson Med. 1997;38:1029–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farrer AI, de Odéen H, de Bever J, et al. Characterization and evaluation of tissue-mimicking gelatin phantoms for use with MRgFUS. J Ther Ultrasound. 2015;3:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Payne A, Merrill R, Minalga E, et al. A breast-specific MR guided focused ultrasound platform and treatment protocol: first-in-human technical evaluation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2021;68:893–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. The phase-difference measurements for the first five images of the phantom with breathing, sorted in acquisition time order (top to bottom then left to right)

Figure S2. The field drift, , measurements for the four studies in this paper sorted in acquisition time order (top to bottom, then left to right). The baseline image is obtained from the complex average over the first five frames before application of focused ultrasound

Figure S3. The phase of the averaged complex phase difference k-space as described in Figure 5. A,B, Gelatin phantom. C,D, Ex vivo salt pork sample. B,D, Volunteer lying above the phantom. The volunteer is outside of the image FOV but contributes a respiratory phase

Figure S4. The field drift, , measurements for the four studies in this paper sorted in acquisition time order (top to bottom, then left to right). The baseline image is obtained from the complex average over all 20 or 25 frames in the dynamic sequence