Abstract

Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders (SSRDs) are commonly encountered in pediatric hospital settings. There is however a lack of standardization of care across institutions for youth with these disorders. These patients are diagnostically and psychosocially complex, posing significant challenges for medical and behavioral healthcare providers. SSRDs are associated with significant healthcare utilization, cost to families and hospitals, and risk for iatrogenic interventions and missed diagnoses. With sponsorship from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and input from multidisciplinary stakeholders, this paper describes the first attempt to develop a clinical pathway (CP) and standardize the care of patients with SSRD in pediatric hospital settings, by a workgroup of pediatric consultation-liaison psychiatrists from multiple institutions across North America. The SSRD CP outlines five key steps from admission to discharge and includes practical, evidence-informed approaches to the assessment and management of medically hospitalized children and adolescents with SSRD.

Introduction

Somatization is the process of experiencing emotions as physical symptoms (e.g. headaches, stomachaches, nausea, fatigue) and is a common experience of children and adolescents.1 When these symptoms are persistent and markedly interfere with functioning, the group of conditions known as Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders (SSRDs) should be considered. SSRDs are characterized by impairing physical symptoms that are influenced by psychological factors, although they may co-occur with a medical condition, especially when symptoms are severe enough to warrant hospitalization.2,3 SSRDs in youth are associated with disruptions to education, peer relationships, recreation, and family functioning and can negatively affect their developmental trajectory.2,4 Families affected by SSRDs tend to distrust emotional or psychological explanations for the symptoms, fear that a medical condition has been missed, and perceive stigma from a mental health diagnosis.5 Often this results in late or declined mental health treatment, medication over reliance, and family frustration.6,7

Primary and specialty pediatric care services, such as pediatric hospital medicine, neurology and gastroenterology, are often extensively utilized by children with SSRDs.3,8–11 Children with SSRD account for 10 – 15% of medical visits in primary care,12,13 and somatization is the second leading reason for consultation requests received by child and adolescent psychiatrists in pediatric hospitals.14 Healthcare professionals often feel unprepared to care for these patients due to insufficient training in the diagnostic and management processes,15 the lack of common terminology for the illness phenomenon, the absence of standard treatment guidelines, and the time-consuming nature of the care.16 Literature demonstrates that management of youth with SSRDs is associated with a high level of provider and family frustration and poor treatment outcomes despite the often extensive level of resources used.12,17,18 Other related challenges include heightened risk of iatrogenic injury, prolonged medical hospitalization, diagnostic errors (involving both medical and mental health diagnoses), increased morbidity, high healthcare costs and high levels of economic and emotional burden to families.

Given these challenges, and the lack of standardization of care in the pediatric SSRD population, there is a clear need to develop evidence-informed, integrated, SSRD care models through the use of a clinical pathway (CP). CPs bridge the gap between research findings and daily practice19 by bringing available evidence to healthcare professionals and outlining essential steps in patient care that can be adapted to local context.19–24 CPs aim to reduce practice variations and improve efficiency and effectiveness of healthcare.25 Multiple studies show that CPs improve clinical outcomes,26–28 while decreasing length of stay and hospital costs.29 The use of CPs is increasing worldwide and they are commonly used in North America for medical conditions such as asthma and diabetes25–28. There is however a lack of published clinical pathways for the management of psychiatric disorders in pediatric hospital settings.

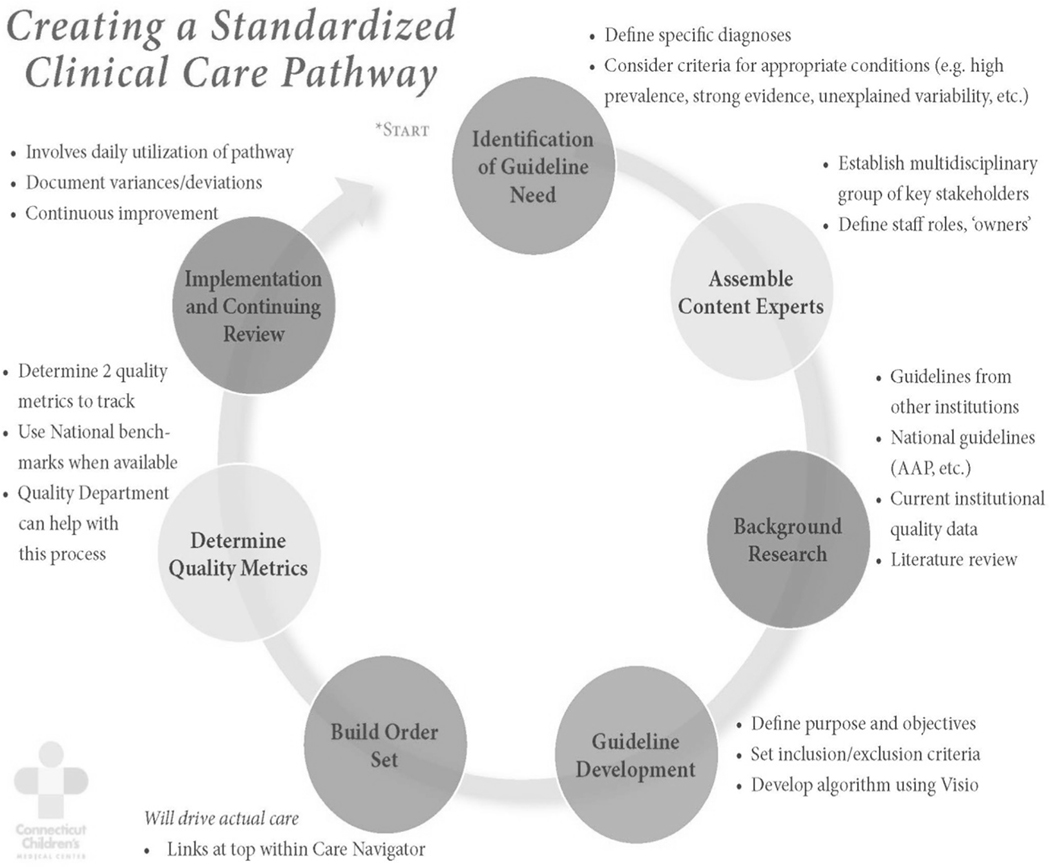

Sekaran and Waynik30 describe a model for developing and implementing CPs (Figure 1). Factors that predict successful development and implementation of CPs include high disease prevalence and high practice variability,25 which are both prominent features of pediatric SSRDs14–16. While there is some evidence about psychotherapeutic interventions to address SSRD in primary care,7 there is limited published data on best practices for SSRD management in pediatric hospitals. The current paper describes the process and content of a CP developed by an expert group of pediatric consultation-liaison psychiatrists in the United States (US) and Canada to guide the care of patients with SSRD in pediatric hospital settings.

Figure 1:

Steps in creating a Clinical Pathway

Created by Anand Sekaran, MD and Ilana Waynik, MD

Methods

The SSRD workgroup utilized a standardized model for “Creating a Clinical CP”.30 Each of the steps is described below:

1). Identifying the need for a CP:

As described previously, SSRDs are prevalent in the pediatric population, have high medical and psychiatric comorbidities, result in considerable healthcare utilization, with providers having little guidance or coordination in the care for patients with SSRD in pediatric hospitals. A CP was adopted to standardize fundamental elements of care and to facilitate best practices.

2). Assembling a team of experts:

The SSRD workgroup consisted of 12 pediatric consultation-liaison psychiatrists who have an established expertise, clinical experience, and interest in SSRD evaluation and management in pediatric hospitals. These psychiatrists practice in a wide variety of settings/contexts, from eight US states and three Canadian provinces. A pediatrician with expertise in CP development provided guidance and feedback during the process.

3). Compiling and reviewing existing research:

The literature on SSRD is evolving. The current evidence base was reviewed by workgroup members and informed the pathway development. Local SSRD pathways and protocols from 7 institutions of participating workgroup members were reviewed to identify common and essential elements/themes, as well as important lessons learned from developing and implementing local pathways, which also informed the current CP.

4). Developing the CP:

a. Initial Draft:

The SSRD workgroup held monthly teleconference calls for two years starting in April 2016. After the first few months of review and discussion of literature, as well as lessons learned from developing and implementing local pathways, key steps in the SSRD pathway were outlined. Achieving interdisciplinary consensus on SSRD evaluation, diagnosis, symptom management, and discharge planning were considered important aspects of the pathway. The vital role of communicating with families and ensuring linkages to outpatient care providers was highlighted.

b. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Abramson Fund Grant:

A full weekend workshop for the Pathways in Clinical Care (PaCC) workgroup, consisting of the SSRD workgroup and two other workgroups, was sponsored by the AACAP Abramson Fund grant. The initial draft of the CP generated by the SSRD workgroup was shared with the whole PaCC workgroup for feedback. The pediatrician with CP expertise provided substantive input regarding development, content, language and visual representation of information. Reflections and responses received during this workshop were incorporated into a second draft of the SSRD CP.

c. Stakeholder Feedback:

Stakeholder feedback was obtained from six North American pediatric clinical institutions. These stakeholders came from twelve disciplines involved in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with SSRDs in the pediatric hospital setting. This included providers from pediatric hospital medicine, adolescent medicine, psychology, child psychiatry, social work, physical and occupational therapy, case management, neurology, surgery, nursing, and nursing education. The stakeholders reviewed the second draft of CP materials (flowchart and text documents) and provided specific feedback on each section of the pathway. Written transcripts of the stakeholder feedback statements were systematically analyzed for emerging themes (Table 1). Through a consensus workgroup process, each feedback element was reviewed and modifications were made to further strengthen the structure and content of the pathway

Table 1.

Stakeholder Feedback

| Stakeholder Disciplines |

|---|

| 1) Pediatrics/Pediatric Hospital Medicine |

| 2) Adolescent Medicine |

| 3) Psychology |

| 4) Child Psychiatry |

| 5) Social work |

| 6) Physical Therapy |

| 7) Occupational Therapy |

| 8) Case Management |

| 9) Neurology |

| 10) Surgery |

| 11) Nurses |

| 12) Nurse Educators |

|

|

| Overall Feedback |

|

|

| • “An important topic, for which a pathway and guide are needed.” |

| • “I think this generally looks very good. I like the organized, multidisciplinary approach. I’ve shown it to a few other members of my team who agree.” |

| • “Like the idea of making things consistent”. |

| • “This will be a very helpful document. It is well laid out and very clear.” |

|

|

| Emergent Themes |

|

|

| • Streamlining and formatting suggestions for the flowchart and documents |

| • Clarify timing of psychiatry involvement |

| • Clarify terminology and language |

| • Clarify roles and responsibilities of interdisciplinary providers. |

| • Goal discordance: medical and psychiatry teams |

| • Clarify communication with patients and families |

| • Clarify communication processes with external healthcare providers • Provide resources for physicians and other healthcare providers |

| • Customization of care versus standardization • Anticipated process challenges |

| • Create a new model of care |

d. Final Draft:

The SSRD CP was presented at a member services forum at the AACAP 2017 annual conference in Washington, DC. The feedback generated from the forum participants consisting of a diverse national audience was incorporated into the final version of the SSRD CP.

Results

The CP development resulted in the creation of four components of an SSRD CP, which will be described in further detail below:

An introduction for the suite of CP documents

A flowchart to serve as a graphic illustration of the steps in the approach to caring for hospitalized youth with SSRDs

A detailed text guide providing narrative explanation of each step outlined in the CP with supporting literature

Sample scripts and handouts to standardize and aide with communication within the steps of the CP.

CP Introduction

The introductory document describes the need for a hospital based SSRD CP, outlines the potential clinical, financial and administrative benefits of addressing the challenges faced with caring for this patient population and provides an overview of the proposed CP (Appendix A). The information presented in the introductory document is relevant to both healthcare providers and hospital administrators in order to address the whole range of hospital stakeholders involved in facilitating SSRD CP adoption and implementation at the local level.

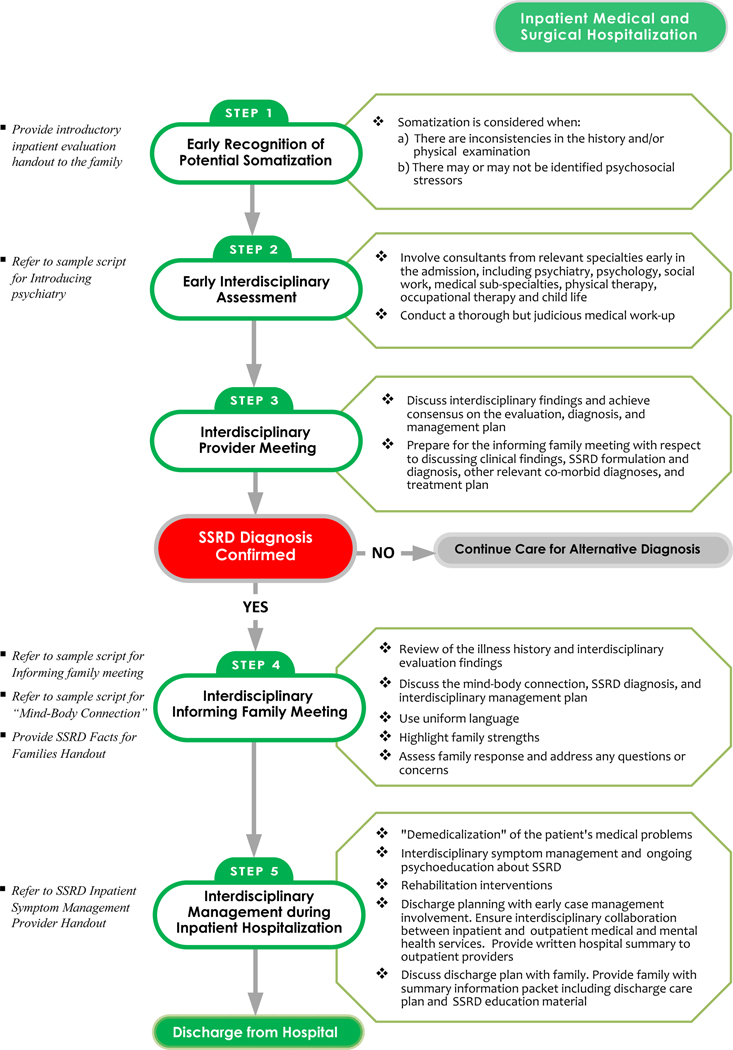

CP Flowchart

The flowchart serves as a visual reference highlighting the five critical steps of the SSRD CP from admission to discharge, including screening, evaluation and management (Figure 2).

CLINICAL PATHWAY FOR SOMATIC SYMPTOM AND RELATED DISORDERS (SSRD).

Sponsored by AACAP’s Abramson Grant. Created by PaCC workgroup of Physically Ill Child Committee.

CP Text Guide

The comprehensive companion text document for the SSRD CP provides specific, detailed information for each step of the pathway and serves as an explanatory guide for the graphic flowchart (Appendix B). The SSRD CP text guide offers pertinent background information on somatization and SSRD in youth, describes how interdisciplinary inpatient pediatric care teams can implement each step, and provides recommendations for screening, and integrated medical and psychiatric evaluation and management. The guide includes the existing literature that informed each step of the pathway.

CP Scripts and Handouts

The scripts and handouts developed as part of the SSRD CP are summarized in Table 2. These materials guide the interdisciplinary providers on how to present the SSRD CP approach to patients and their families, including how to introduce psychiatry and other consultants as part of the interdisciplinary team, how to describe the evaluation process to the patient and family, and how to share input from interdisciplinary findings with families. The handouts summarize patient/family-centered facts about SSRDs and provide consistent language to anchor providers in the communication of aspects of SSRD care. Since these patients rarely present first to behavioral health providers, a goal of these scripts is to help increase comfort and skill among healthcare providers from various disciplines in managing SSRDs and to mitigate the challenges experienced by families in receiving and accepting the SSRD diagnoses.

Table 2.

SSRD Clinical Pathway Scripts and Handout

| FAMILY INTRODUCTORY HANDOUT | Your child currently has physical symptoms that are causing great worry and may leave you with questions and concerns. Your family is attempting to understand your child’s symptoms, and get an explanation for why your child continues to have physical symptoms. These symptoms are impairing and get in the way of your child’s health and success. We understand that your child’s illness has been difficult for your child and everyone in your family. |

| At this time, your child will be admitted to the hospital for a brief stay to conduct an evaluation with the goals of: | |

| • Understanding your child’s symptoms and their impact on functioning | |

| • Providing a diagnosis or diagnoses | |

| • Providing an explanation for your child’s symptoms | |

| • Providing some symptomatic relief for your child | |

| • Developing a plan for continued care to improve your child’s functioning | |

| Your child’s evaluation will include: | |

| • A careful review of previous medical records and information about your child | |

| • Completion of previous medical records and information about your child | |

| • Completion of any further evaluations as needed | |

| • Working together with a team that may include pediatricians, pediatric subspecialists, psychiatry, psychology, social work, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, child life. | |

| At the end of your child’s stay, your child will have a completed evaluation, discussion of results, review of diagnoses and explanations for symptoms, as well as a plan for future symptom care. Your child’s symptoms may not be gone when your child is ready to leave the hospital. We will work to establish goals to improve your child’s health and help your child return to normal activities, including a plan to collaborate with your child’s school, primary care doctor and other providers in the community to promote your child’s functioning and improvement upon discharge. | |

|

| |

| SAMPLE SCRIPT FOR INTRODUCING PSYCHIATRY AND OTHER CONSULTATIONS TO THE FAMILY | “We are going to review all the tests and treatments you’ve done so far to determine what has been helpful, what needs to be repeated and what new tests and consultations are needed. We see many children with symptoms similar to what your child has and have a standard multidisciplinary approach to care that includes different consultants from medical specialties, surgical specialties, physical/occupational therapy, social work, psychiatry/psychology, etc. This comprehensive approach will help us better understand the nature of your child’s symptoms and the impact on all areas of his/her life, and will also help us develop an effective management plan.” (You may include this last sentence here or only in the context below.) |

| If family is resistant to psychiatry consultation or asks for more information regarding this, clarify that psychiatry helps with: | |

| • Understanding the child’s symptoms | |

| • Assessing the impact of the symptoms on the child and on the family | |

| • Helping the child and family cope with the symptoms and get their lives back | |

|

| |

| SAMPLE SCRIPT FOR INTRODUCING THE USE OF MEASURES | “As part of our evaluation we have some measures for you/your child to complete that will help us in our assessment. These measures take approximately X minutes to complete and helps us standardize our evaluation process while being as thorough as possible. The measures assess (insert based on measures being administered). Please be assured that completing these measures is voluntary and if you do not wish to do so this would not change the care that you receive while in the hospital.” |

|

| |

| SAMPLE SCRIPT FOR THE INFORMING FAMILY MEETING | “As we said at the beginning of your son/daughter’s hospital stay, after completing your child’s evaluation we come together as a multidisciplinary team to discuss what we think is contributing to your child’s symptoms and what we think the treatment should be. We want to give you a chance to ask questions and to be sure that you feel comfortable about our assessment and treatment plan. We understand how debilitating these symptoms have been and want to take our time to be sure we address your questions or concerns. |

| “We want to share with you a summary of your child’s symptoms, why we consulted with the specialists we did, what diagnoses we were considering, and what our findings did or did not support. Please tell us along the way if we have any part of the history wrong, or if there is anything you do not understand. And please let us know if there is any particular medical condition or diagnosis that you feel we have not adequately addressed. | |

| “[PATIENT NAME HERE] first presented with: Prior work-up included: Our team performed the following tests/evaluations: We found: |

|

| “Given these findings and with the input from our specialists, we think your child’s symptoms are best understood as*: In our experience, symptoms due to_______________respond best to the following treatment approach:” |

|

| *If a somatic symptom or related disorder (SSRD) is being considered or the diagnosis has been made, the attending physician leading the meeting should use the actual diagnosis rather than a symptom or general language (e.g., conversion rather than “stress”). Ask psychiatry to give their assessment of potential contributors that have been determined from the psychiatric evaluation performed. Additional explanatory handouts can be used as needed, including the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Facts for Families on SSRD. https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Physical_Symptoms_of_Emotional_Distress-Somatic_Symptoms_and_Related_Disorders.aspx |

|

|

| |

| SAMPLE SCRIPT FOR DISCUSSING THE MIND-BODY CONNECTION | “The brain and body are connected and communicate through nerves, hormones, and chemicals. We call this the mind-body connection. Sometimes it’s hard to understand how the mind body connection contributes to symptoms, so we want to explain that. The body automatically sends information to the brain and at the same time, the brain automatically sends information to the body to communicate feelings such as fear and pain. |

| “You may have heard of the “fight/flight/freeze” response. When we sense danger, the brain tells the body to stay on alert using electrical and chemical signals. The body starts doing things to help us survive; for example, lungs breathe faster and shallower and heart beats faster and harder to get more oxygen to the brain and muscles. Muscles tense up getting ready to fight or run. All of these reactions happen quickly and automatically, without us even thinking about it. Later when the danger is gone, the brain tells the body to calm down but the experience can leave a physical toll on the body. This is our body’s response to stress, also known as the physiology of stress. | |

| “Stress can be positive or negative, and although we may not consider something ‘dangerous’ or stressful, our bodies can experience the effects of stress through physical symptoms. In this way, we can view the physical symptoms as the body telling us it is feeling distressed or that we are feeling the emotion or stress in our bodies. | |

Discussion

This is the first clinical pathway developed by a group of expert child psychiatrists, with pediatric stakeholder input, from multiple institutions in North America, to standardize pediatric SSRD care in the inpatient hospital setting. The efforts of the workgroup resulted in a pathway for SSRD that meets the operational definition of CPs, based on the following four criteria: (1) is a structured multidisciplinary plan of care; (2) is used to translate guidelines or evidence into local processes; (3) details the steps in a course of treatment or care in a plan, pathway, algorithm, guideline, protocol; and (4) aims to standardize care for a specific population.25

Key Themes in the SSRD CP

The first and second steps of the SSRD CP emphasize early identification of somatization with a process of simultaneous physical and mental health diagnostic evaluations. Studies show that early mental health consultation reduces the length of admissions for medically ill pediatric patients with comorbid mental health diagnoses, including patients with SSRDs.31 It is critical to ensure that patients and families understand the interdisciplinary nature of evaluation and the multifactorial nature of SSRDs, in order to normalize the involvement of mental health professionals. 6,11,32 Delayed mental health involvement results in patients and families perceiving that their care is being “handed off” to mental health and further stigmatizes the condition.10 The presence of inconsistent physical symptoms and/or psychosocial stressors, while raising the concern for possible somatization, is insufficient to make a diagnosis of SSRD. The importance of an interdisciplinary evaluation that includes a comprehensive and judicious medical work-up is also emphasized, to ensure that existing medical conditions are not overlooked in the context of the concerns for somatization and SSRD evaluation. With the use of the SSRD CP, patient and family expectations are set early in the course of the inpatient hospitalization to align them with the role of the interdisciplinary care team. These expectations include interdisciplinary evaluation and management targeting symptom reduction (as feasible) through the use of behavioral interventions, rehabilitation therapies and parent training, and establishing an interdisciplinary outpatient treatment plan.33,6

For the third and fourth steps of the SSRD CP, it is recommended that an interdisciplinary provider meeting and an informing family meeting be held once diagnostic assessment is completed. SSRD care is often characterized by disjointed evaluations and mixed message delivery to patients and families.7 Ensuring effective, interdisciplinary communication with the family has been found to be associated with improved treatment adherence, participation in outpatient follow up, and improved patient outcomes.32 A coordinated approach by interdisciplinary providers reaffirms the multifactorial nature of SSRDs, facilitates a consistent communication strategy and reduces the likelihood of misunderstandings or miscommunication about the diagnoses. The informing meeting provides families with a shared conceptual framework for somatic symptom development. It also provides an opportunity to educate the family about SSRDs and review the diagnostic formulation using DSM-5 consistent language. Involving primary care and other key outpatient providers in the informing meeting offers a natural transition point in the SSRD care from completion of the diagnostic evaluation to focusing on multidisciplinary management and disposition planning, including outpatient care.32,7 Using consistent, understandable, DSM-5 based terminology and providing explanation regarding the biopsychosocial model is critical to effective symptom evaluation and management.7 Therefore, practical scripts are included in the CP to guide clinicians at all levels of training to effectively discuss the conceptual framework of symptom development, diagnosis, and treatment in pediatric SSRD. This fosters operationalization of the CP by offering tools and resources for providers to enact the core steps of the pathway.

Early management and disposition planning is the focus of the fifth and final step of the pathway. Treatment for SSRDs can be initiated within the hospital setting with the goal of improving functionality and successfully transitioning to outpatient care.34 Children with more profound and pervasive functional impairment, with or without other comorbid conditions, may need more intensive treatments, including admission to medical-psychiatric programs or physical rehabilitation units.6 Disposition planning is multidisciplinary, with a focus on promoting active engagement with the primary care provider (PCP), establishing follow-up care with outpatient mental health providers familiar with SSRDs, ongoing monitoring by subspecialty pediatric providers as indicated, utilizing continued outpatient rehabilitative services if needed, and providing guidance to families and schools.10,32–35 Scheduled and frequent follow-up visits with a PCP are important to maintain alliance and investment in treatment, and provide ongoing medical education and reassurance.33

Limitations and Future Directions

The SSRD CP workgroup consisted primarily of experts in child and adolescent consultation-liaison psychiatry. Other disciplines, including psychology, were involved in the stakeholder feedback but were not part of the primary workgroup. Interdisciplinary and patient/family involvement in the operationalization of the SSRD CP and care expansion to outpatient settings will be helpful in capturing a broader perspective on SSRD care.

Compared to other clinical diagnoses in child and adolescent psychiatry, such as depression, anxiety, and suicide, there is a relative dearth of literature on SSRD evaluation and management, particularly in inpatient pediatric settings. Available evidence supported the development of this pathway, however, randomized controlled trials for evaluation and treatment of SSRDs are still lacking. The workgroup was faced with a wide diversity of practices, expectations, systems, and resources that currently exists in SSRD care throughout the represented geography. This was obviated by sharing current practices and resources, developing a consensus set of principles and fundamental practices, as well as accounting for the known limitations in mental health consultation and access that often exists in many parts of North America. As the SSRD workgroup relied on expert consensus and experience to inform CP and resource development, there is a potential for introduction of bias in the CP development by relying more on the members of the group with greater experience in SSRD care. For this initial effort at standardization of care, the consensus was developed using discussions and verbal communications amongst the workgroup members, no formal method of consensus gathering, such as Delphi procedure, was utilized.

Specific recommendations for inpatient assessment and management of SSRDs have been made in this CP. We recognize that the pathway implementation may be influenced by resource availability in local hospital settings, including a psychiatry consultation-liaison service. The diversity of practice locations of the workgroup was intended to mitigate this limitation and consideration of resource limitations was a guiding principle in this CP development. The SSRD CP is a flexible guide allowing clinicians to adapt it to local resources and realities, while preserving the core features, central themes and principles of the CP.

With significant changes in the diagnostic language and criteria of SSRDs within the DSM 5, as well as the overlap of a variety of other clinical and non-clinical terms commonly used in describing symptoms and presentations of SSRDs, the working group spent a considerable amount of time clarifying, reviewing and discussing the use of language and terms. Ultimately, the decision was made to focus on DSM 5 language for consistency and clarity, given the audience utilizing the SSRD CP. Local practices and language that is familiar and well-accepted by patients, families and providers can be accommodated within the CP, so long as they generally adhere to the principles, current evidence, and the DSM-5. Although the scope of the SSRD CP was to focus on the inpatient pediatric setting, the CP and its associated resources contain significant language prompts to engage and communicate with providers within the outpatient setting so as to allow for smooth transition of care and cross talk between the two systems. Since these patients often present to emergency departments, future efforts addressing SSRD care in this setting will also be important.

Finally, the implementation and efficacy of this SSRD CP has not yet been established empirically. Future directions for the CP implementation point toward developing partnerships with pediatric hospitalists and sub-specialists, hospital administrators, nursing, consultation-liaison psychiatry and psychology and support staff. It is important to identify local champions to lead implementation by providing education and support for clinical application of the pathway. Research studies on the feasibility and outcomes of the SSRD CP are needed to investigate if the SSRD CP has the potential to standardize pediatric SSRD care in hospital settings across medical institutions in North America. The members of the North American PaCC SSRD workgroup plan to implement the SSRD CP in individual institutions and empirically study the implementation process and anticipated outcomes, including improvements in clinical care, cost savings, and the impact of early interdisciplinary collaboration.

In summary, this CP is the first attempt to develop a standardized approach to SSRD care across multiple pediatric institutions in North America. Given the existing gap in guidelines for the care of these patients in many hospitals, this CP will be a helpful resource for healthcare providers of various disciplines in the assessment and management of medically hospitalized youth with SSRD.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1 ).American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (2018). Physical Symptoms of Emotional Distress: Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders Facts For Families. https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Physical_Symptoms_of_Emotional_Distress-Somatic_Symptoms_and_Related_Disorders.aspx Accessed 8/27/18 [Google Scholar]

- 2 ).American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5. Vol 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. doi: 10.1007/SpringerReference_69770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3 ).Bujoreanu S, Randall E, Thomson K, Ibeziako P. Characteristics of medically hospitalized pediatric patients with somatoform diagnoses. Hosp Pediatr. 2014. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2014-0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4 ).Thomson K, Randall E, Ibeziako P, Bujoreanu IS. Somatoform Disorders and Trauma in Medically-Admitted Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults: Prevalence Rates and Psychosocial Characteristics. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6). doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5 ).Looper KJ, Kirmayer LJ. (2004) Perceived stigma in functional somatic syndromes and comparable medical conditions. J Psychosom Res, 57(4):373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6 ).Ibeziako P, Bujoreanu S. Approach to psychosomatic illness in adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283483f1c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7 ).Malas N, Ortiz-Aguayo R, Giles L, Ibeziako P. Pediatric Somatic Symptom Disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0760-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8 ).Geist R, Weinstein M, Walker L, Campo JV. Medically Unexplained Symptoms in Young People: The Doctor’s Dilemma. Vol 13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9 ).Lindley KJ, Glaser D, Milla PJ. Consumerism in healthcare can be detrimental to child health: Lessons from children with functional abdominal pain. Arch Dis Child. 2005. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.032524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10 ).Campo J V, Fritz G. A Management Model for Pediatric Somatization. Psychosomatics. 2001. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.42.6.467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11 ).Campo J V. Annual research review: Functional somatic symptoms and associated anxiety and depression - Developmental psychopathology in pediatric practice. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02535.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12 ).Rask CU, Ornbol E, Fink PK, Skogaard AM. (2013) Functional Somatic Symptoms and Consultation Patterns in 5 to 7 Year Olds. Pediatrics, 132:e459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13 ).Gieteling MJ, Lisman-van Leeuwen Y, van der Wouden JC, Schellevis FG, Berger MY. Childhood nonspecifi c abdominal pain in family practice: Incidence, associated factors, and management. Ann Fam Med. 2011. doi: 10.1370/afm.1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14 ).Shaw RJ, Pao M, Holland JE, DeMaso DR. Practice Patterns Revisited in Pediatric Psychosomatic Medicine. Psychosomatics. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15 ).Miresco MJ, Kirmayer LJ. The persistence of mind-brain dualism in psychiatric reasoning about clinical scenarios. Am J Psychiatry. 2006. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16 ).Wileman L, May C, Chew-Graham CA. Medically Unexplained Symptoms and the Problem of Power in the Primary Care Consultation: A Qualitative Study. Vol 19.; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17 ).Dell ML, et al. (2011) Somatoform Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Psychiatr Clin N Am., 34:643–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18 ).Ring A, Dowrick C, Humphris G, Salmon P. (2004) Do patients with unexplained medical symptoms pressurize general practitioners for somatic treatment? A qualitative study. BMJ, 328:1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19 ).Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge Translation of Research Findings; 2012. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20 ).Rotter T, Plishka C, Hansia MR, et al. The development, implementation and evaluation of clinical pathways for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Saskatchewan: Protocol for an interrupted times series evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2750-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21 ).Francke AL, Smit MC, Je De Veer A, Mistiaen P. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: A systematic meta-review. 2008. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-8-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22 ).Hakkennes S, Dodd K. Guideline implementation in allied health professions: A systematic review of the literature. Qual Saf Heal Care. 2008. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.023804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23 ).Kitson A. Knowledge translation and guidelines: A transfer, translation or transformation process? Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2009.00130.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24 ).Richens Y, Rycroft-Malone J, & Morrell C. (2004). Getting guidelines into practice: A literature review. Nursing Standard, 18(50), 33–40. doi: 10.7748/ns2004.08.18.50.33.c3677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25 ).Lawal AK, Rotter T, Kinsman L, Machotta A, Ronellenfitsch U, Scott SD, Goodridge D, Plishka C, Groot G. What is a clinical pathway? Refinement of an operational definition to identify clinical pathway studies for a Cochrane systematic review. BMC Med. 2016. Feb 23;14:35. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0580-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26 ).Ban A, Ismail A, Harun R, Abdul Rahman A, Sulung S, Syed Mohamed A. Impact of clinical pathway on clinical outcomes in the management of COPD exacerbation. BMC Pulm Med. 2012. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-12-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27 ).Casas A, Troosters T, Garcia-Aymerich J, et al. Integrated care prevents hospitalisations for exacerbations in COPD patients. Eur Respir J. 2006. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00063205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28 ).Rotter T, et al. , Clinical pathways: effects on professional practice, patient outcomes, length of stay and hospital costs. The Cochrane Library, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29 ).Kaiser SV, Rodean J, Bekmezian A, Hall M, Shah SS, Mahant S, Parikh K, Auerbach AD, Morse R, Puls HT, McCulloch CE, Cabana MD. Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network. Effectiveness of Pediatric Asthma Pathways for Hospitalized Children: A Multicenter, National Analysis. J Pediatr. 2018. Mar 20. pii: S0022–3476(18)30176–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30 ).Waynik I, Sekaran A, Bode R, Engel R, A Path to Successful Pathway Development. [lecture] Pediatric Hospital Medicine Annual Conference. Chicago, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 31 ).Bujoreanu S, White MT, Gerber B, Ibeziako P. Effect of Timing of Psychiatry Consultation on Length of Pediatric Hospitalization and Hospital Charges. Hosp Pediatr. 2015. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2014-0079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32 ).Plioplys S, Asato MR, Bursch B, et al. Multidisciplinary management of pediatric non-epileptic seizures. Journal of The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2007; 46(11): 1491–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33 ).Burton C, Weller D, Marsden W, Worth A, Sharpe M. A primary care Symptoms Clinic for patients with medically unexplained symptoms: Pilot randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2012. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34 ).Ibeziako P, Rohan JM, Bujoreanu S, Choi C, Hanrahan M, Freizinger M. Medically Hospitalized Patients With Eating Disorders and Somatoform Disorders in Pediatrics: What Are Their Similarities and Differences and How Can We Improve Their Care? 2016:2154–1671. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35 ).Kroenke K. Efficacy of Treatment for Somatoform Disorders: A Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. 2007. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815b00c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.