Abstract

Concerns over reports of suicidal ideation associated with semaglutide treatment, a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP1R) agonist medication for type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and obesity, has led to investigations by European regulatory agencies. In this retrospective cohort study of electronic health records from the TriNetX Analytics Network, we aimed to assess the associations of semaglutide with suicidal ideation compared to non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity or anti-diabetes medications. The hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of incident and recurrent suicidal ideation were calculated for the 6-month follow-up by comparing propensity score-matched patient groups. The study population included 240,618 patients with overweight or obesity who were prescribed semaglutide or non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medications, with the findings replicated in 1,589,855 patients with T2DM. In patients with overweight or obesity (mean age 50.1 years, 72.6% female), semaglutide compared with non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medications was associated with lower risk for incident (HR = 0.27, 95% CI = 0.200.32–0.600.36) and recurrent (HR = 0.44, 95% CI = 0.32–0.60) suicidal ideation, consistent across sex, age and ethnicity stratification. Similar findings were replicated in patients with T2DM (mean age 57.5 years, 49.2% female). Our findings do not support higher risks of suicidal ideation with semaglutide compared with non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity or anti-diabetes medications.

Suicide is a serious and preventable public health concern with 759,028 people reported worldwide to have died from suicide in 2019 (ref. 1). Suicide is among the top 10 leading causes of death and the fourth among people aged 15–29 years2. Suicide death rates vary according to demographics, with males having 2–3 times higher rates than females and people older than 85 years having some of the highest rates globally3. In the United States, provisional data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calculated that in 2022 over 49,449 individuals died by suicide, with suicide rates among the highest in people aged between 25 and 34 years of age and over 75 years of age4.

Thus, a concern for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other regulatory agencies that approve medications for human use is to minimize the risks that these medications increase suicidal ideation. Although preapproval trials are required to show a lack of suicidal ideation, their predictive accuracy for safety is constrained by the relatively limited number of patients included5. To address this, regulatory agencies have established several post-marketing surveillance methods that can lead to ‘black box’ labels for the highest safety-related warning or potential drug removal. However, the sensitivity and accuracy of these methods have been questioned6. A study that used the MarketScan database to review 922 drugs prescribed between 2003 and 2014 identified ten drugs associated with increased risk of suicidal ideations and 44 drugs associated with decreased risk, including many that required a ‘black box’ label by the FDA warning of their association with suicide rates6.

Reported associations with increased risk for depression and suicide has led to post-marketing removal of the weight-loss drug rimonabat by the European Medicines Agency (EMA)7. Another example is Qnexa (Vivus) containing two active ingredients, phentermine and topiramate, which despite demonstrating more than 9% body weight loss, was rejected by the FDA partly because of concerns regarding the potential risk of increased suicidal ideation7.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP1R) agonists initially developed as anti-diabetes medications are highly effective for weight loss8,9. Currently, both liraglutide and semaglutide are approved by the FDA and the EMA for weight loss10,11. In July 2023, the EMA12 and the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency in the United Kingdom initiated an investigation of Novo Nordisk’s diabetes drug Ozempic (semaglutide) and weight-loss treatment Wegovy (semaglutide) after reported cases of suicidal ideation associated with their use12. In the United States, the FDA through its Event Reporting System also received reports of suicidal ideation associated with semaglutide13, although these reports have not been verified. Suicidal ideation has been linked to other weight-loss drugs14 and the clinical trial that led to the FDA’s approval of semaglutide excluded participants with a recent history of suicidal ideation15. Instructions for Wegovy include recommended monitoring for suicidal ideation16. However, the association of semaglutide with suicidal ideation compared with non-GLP1R agonist medications has not been investigated.

In this study, we used a large electronic health record (EHR) database to conduct a nationwide retrospective cohort study to assess the association of semaglutide with the incidence and recurrence of suicidal ideation compared with non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medications in individuals with overweight or obesity. We replicated the same analyses in a separate cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) by comparing semaglutide with non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medications.

Results

Suicidal ideation in patients with overweight or obesity

For the analysis of incident suicidal ideation in patients with overweight or obesity, the study population included 232,771 patients who had no previous history of suicidal ideation. The semaglutide group compared with the non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication (bupropion, naltrexone, orlistat, topiramate, phentermine, setmelanotide) group was older, included more males, had a lower prevalence of adverse socioeconomic determinants, mental health disorders, substance use disorders and higher prevalence of T2DM. After propensity score matching, the two groups (52,783 in each group, mean age 50.1 years, 72.6% female, 7.4% Hispanic, 16.0% Black) were balanced (Table 1).

Table 1 |.

Characteristics of the semaglutide and non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication groups for the study population with overweight or obesity and no history of suicidal ideation before the index event (first prescription of semaglutide or non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medications from 1 June 2021 through to 31 December 2022), before and after propensity score matching for the listed variables

| Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semaglutide group | Non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication group | SMD | Semaglutide group | Non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication group | SMD | |

| Total number | 67,804 | 164,967 | 52,783 | 52,783 | ||

| Age at the index event, years, mean±s.d. | 51.6±13.5 | 47.5±15.3 | 0.29a | 50.0±13.4 | 50.3±15.1 | 0.03 |

| Sex (%) | ||||||

| Female | 67.7 | 75.2 | 0.17a | 72.6 | 72.5 | 0.002 |

| Male | 31.8 | 24.3 | 0.17a | 26.9 | 27.0 | 0.002 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 7.5 | 7.9 | 0.01 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 0.008 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 69.9 | 76.9 | 0.16a | 70.9 | 71.4 | 0.01 |

| Unknown | 22.6 | 15.3 | 0.19a | 21.6 | 21.3 | 0.008 |

| Ethnic group (%) | ||||||

| Asian | 2.6 | 0.9 | 0.13a | 1.6 | 1.7 | 0.004 |

| Black | 16.0 | 14.9 | 0.03 | 15.9 | 16.1 | 0.007 |

| White | 68.1 | 71.7 | 0.08 | 69.6 | 69.5 | 0.002 |

| Unknown | 12.0 | 11.9 | 0.003 | 12.0 | 11.7 | 0.008 |

| Marital status (%) | ||||||

| Never married | 12.5 | 17.3 | 0.14a | 13.4 | 13.1 | 0.009 |

| Divorced | 5.5 | 6.0 | 0.02 | 5.6 | 5.6 | <0.001 |

| Widowed | 3.6 | 3.6 | 0.003 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 0.006 |

| Adverse socioeconomic determinants of health (%) | 4.1 | 6.2 | 0.10a | 4.4 | 4.6 | 0.01 |

| Personal history of psychological trauma (%) | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.005 |

| Family history of mental and behavioral disorders (%) | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.06 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.005 |

| Lifestyle-related problems (%) | 7.9 | 10.7 | 0.09 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 0.01 |

| Pre-existing medical conditions (%) | ||||||

| Depression | 26.9 | 40.7 | 0.30a | 30.2 | 31.9 | 0.04 |

| Mood disorders, including bipolar disorder | 32.0 | 48.0 | 0.33a | 35.9 | 37.6 | 0.04 |

| Anxiety, dissociative, somatoform and other nonpsychotic mental disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder | 37.2 | 48.7 | 0.23a | 40.3 | 41.4 | 0.02 |

| Schizophrenia, schizotypal, delusional and other non-mood psychotic disorders | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.08 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.004 |

| Behavioral disorders, including sleep disorders | 9.2 | 10.9 | 0.06 | 9.7 | 10.0 | 0.009 |

| Disorders of adult personality and behavior, including impulse and gender identity disorders | 1.1 | 2.3 | 0.09 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.01 |

| Symptoms and signs involving an emotional state | 4.0 | 5.4 | 0.07 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 0.01 |

| Sleeping disorders including insomnia | 39.5 | 37.0 | 0.05 | 38.0 | 38.8 | 0.02 |

| Chronic pain | 25.3 | 26.9 | 0.04 | 25.2 | 26.0 | 0.02 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 2.4 | 5.2 | 0.15a | 2.7 | 3.0 | 0.02 |

| Tobacco use disorder | 11.7 | 17.9 | 0.18a | 12.4 | 13.0 | 0.02 |

| Opioid use disorder | 1.5 | 3.0 | 0.10a | 1.7 | 1.9 | 0.01 |

| Cannabis use disorder | 1.1 | 2.4 | 0.10a | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.02 |

| Cocaine use disorder | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.08 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.01 |

| Other stimulant-related disorders | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.01 |

| Other psychoactive substance-related disorders | 1.0 | 2.4 | 0.11a | 1.1 | 1.3 | 0.02 |

| T2DM | 44.8 | 15.6 | 0.67a | 30.6 | 31.7 | 0.02 |

| Cancer | 32.6 | 29.5 | 0.07 | 30.7 | 31.1 | 0.008 |

| Traumatic brain injury | 2.1 | 3.1 | 0.06 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 0.009 |

| Previous medication prescription or procedures (%) | ||||||

| Bariatric surgery | 4.4 | 5.4 | 0.05 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 0.007 |

| Antidepressants | 44.0 | 60.4 | 0.33a | 48.1 | 49.7 | 0.03 |

| Antipsychotics | 16.2 | 22.7 | 0.17a | 17.4 | 18.0 | 0.02 |

| Antiepileptics | 32.1 | 40.8 | 0.18a | 33.4 | 34.7 | 0.03 |

| Benzodiazepine-derivative sedatives or hypnotics | 44.0 | 47.0 | 0.06 | 43.5 | 44.2 | 0.01 |

| Esketamine | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.006 |

| Ketamine | 5.2 | 6.4 | 0.05 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 0.004 |

| Lithium | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.005 |

| Bupropion | 15.2 | 30.5 | 0.37a | 18.6 | 20.8 | 0.05 |

| Naltrexone | 3.6 | 3.7 | 0.006 | 4.1 | 4.1 | <0.001 |

| Phentermine | 10.4 | 13.3 | 0.09 | 12.2 | 12.6 | 0.01 |

| Orlistat | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.02 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.006 |

| Topiramate | 9.5 | 17.7 | 0.24a | 11.6 | 12.4 | 0.03 |

| Insulin | 21.5 | 9.8 | 0.33a | 15.0 | 15.8 | 0.02 |

| Metformin | 39.1 | 13.0 | 0.62a | 25.6 | 27.3 | 0.04 |

| Alpha glucosidase inhibitors | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.005 |

| DPP-4 inhibitors | 8.2 | 1.5 | 0.32a | 3.4 | 3.8 | 0.02 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 10.3 | 1.5 | 0.38a | 3.5 | 4.0 | 0.03 |

| Sulfonylureas | 11.6 | 2.6 | 0.36a | 5.5 | 6.2 | 0.03 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 2.7 | 0.7 | 0.16a | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.01 |

The status of variables was based on the presence of related clinical codes any time to 1 day before the index event.

SMD greater than 0.1, a threshold indicating group imbalance.

SMD, standardized mean difference.

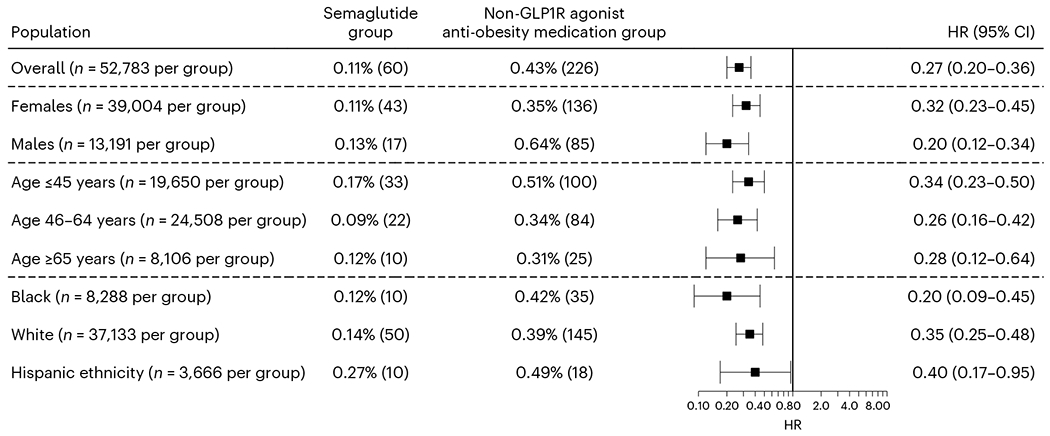

The matched semaglutide and non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication groups were followed during the 6-month time window after the index event (first prescription of semaglutide versus non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medications occurred from June 2021 through to December 2022). The mean follow-up time was 160.5 ± 18.4 days for the semaglutide group and 150.2 ± 26.8 days for the non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication group. The semaglutide group had a significantly lower risk for incident suicidal ideation than the matched non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication group (0.11% versus 0.43%; hazard ratio (HR) = 0.27, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.20–0.36). Consistent lower risks were observed in patients stratified according to sex, age group, ethnicity and ethnic grouping (Fig. 1). Among 52,783 patients in the semaglutide group, no patient reported suicide attempts during the 6-month follow-up after semaglutide prescription, whereas 14 of 52,783 patients reported suicidal attempts in the matched non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication group during the 6-month follow-up after medication prescription (P < 0.001)

Fig. 1|. Incident suicidal ideations in the study population with overweight or obesity.

Comparison of the incident (first-time experience of) suicidal ideation in the study population with overweight or obesity and no previous history of suicidal ideation (before the index event of the first prescription of semaglutide or non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medications that occurred from 1 June 2021 through to 31 December 2022) between the propensity score-matched semaglutide and non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication groups within a 6-month time window after the index event. For each group, the overall risk (number of cases) is shown, where overall risk is defined as the number of patients with outcomes during the 6-month time window divided by the number of patients in the group at the beginning of the time window. HRs were calculated using Kaplan–Meier analysis to estimate the probability of outcome at daily time intervals with censoring applied.

For the analysis of recurrent suicidal ideation in patients with overweight or obesity, the study population included 7,847 patients who had a previous history of suicidal ideation. The semaglutide group compared to the non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication group was older, included more females, had a lower prevalence of adverse socioeconomic determinants of health, substance use disorders, suicide attempts and intentional self-harm, and higher prevalence of T2DM, cancer and chronic pain. After propensity score matching, the two groups (865 in each group, mean age 44.4 years, 72.1% female, 6.8% Hispanic, 13.8% Black) were balanced (Extended Data Table 1).

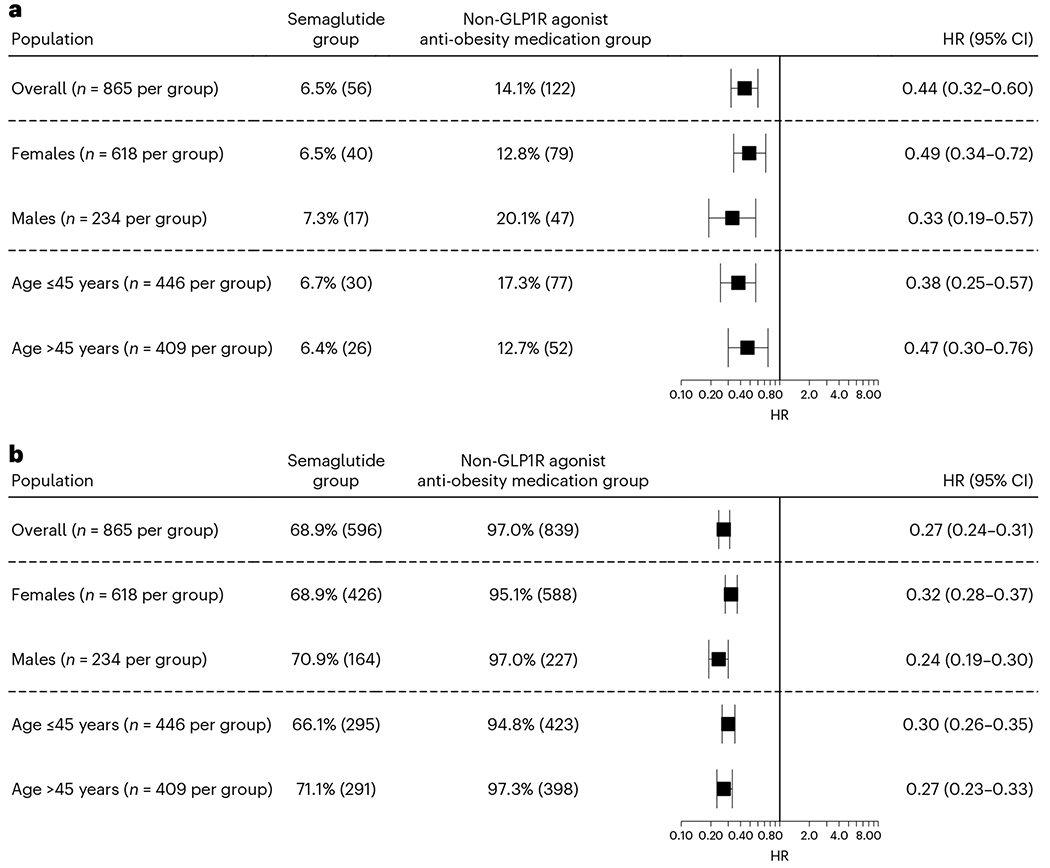

The mean follow-up time for the study population with overweight or obesity and a previous history of suicidal ideations was 160.4 ± 18.2 days for the semaglutide group and 161.4 ± 17.7 days for the non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication group. The semaglutide group was associated with a significantly lower risk for recurrent experience of suicidal ideation (6.5% versus 14.1%; HR = 0.44, 95% CI = 0.32–0.60) and had lower rates of medication prescriptions related to the treatment for suicidal ideation compared to the matched non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication group (69.3% versus 96.6%, HR = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.25–0.32), which was consistent with patient subgroups stratified according to sex and age (Fig. 2). Stratification according to older adults, ethnic grouping and ethnicity was not performed because of limited sample sizes. The number of patients who had suicide attempt during the 6-month follow-up in both groups was between 1 and 9, but the actual number was not reported because of privacy concerns.

Fig. 2|. Recurrent experience of suicidal ideation and medication prescription for suicidal ideation treatment in the study population with overweight or obesity.

a,b, Comparison of recurrent experience of suicidal ideation (a) and medication prescription for suicidal ideation treatment (b) in the study population with overweight or obesity and a previous history of suicidal ideation (before the index event of the first prescription of semaglutide versus non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medications that occurred from 1 June 2021 through to 31 December 2022) between the propensity score-matched semaglutide and non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication groups within a 6-month time window after the index event. For each group, the overall risk (number of cases) is shown, where overall risk is defined as the number of patients with outcomes during the 6-month time window divided by the number of patients in the group at the beginning of the time window. HRs were calculated using Kaplan–Meier analysis to estimate the probability of outcome at daily time intervals with censoring applied.

Suicidal ideation in patients with T2DM

For the analysis of incident suicidal ideation in patients with T2DM, the study population consisted of 1,572,885 patients with no previous history of suicidal ideation. The semaglutide group compared to the non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication group (insulin, metformin, sulfonylureas, alpha glucosidase inhibitors, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, sodium/glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors) was younger, included fewer individuals of Hispanic ethnicity, had a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity, cancer, chronic pain and mental disorders, and higher prevalence of previous non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication prescriptions. After propensity score matching, the two groups (27,726 in each group, mean age 57.5 years, 49.2% female, 5.8% Hispanic, 15.4% Black) were balanced (Table 2).

Table 2 |.

Characteristics of the semaglutide group and non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication group for the study population with T2DM and no history of suicidal ideation before the index event (first prescription of semaglutide or other non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medications from 1 December 2017 to 31 May 2021), before and after propensity score matching for the listed variables

| Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semaglutide group | Non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication group | SMD | Semaglutide group | Non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication group | SMD | |

| Total number | 27,282 | 1,545,603 | 27,276 | 27,726 | ||

| Age at the index event, years, mean±s.d. | 57.5±12.5 | 62.0±15.2 | 0.32a | 57.5±12.5 | 57.4±14.4 | 0.006 |

| Sex (%) | ||||||

| Female | 48.8 | 47.6 | 0.02 | 48.8 | 49.5 | 0.006 |

| Male | 50.3 | 52.1 | 0.04 | 50.3 | 49.7 | 0.01 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 5.8 | 9.6 | 0.14a | 5.8 | 5.8 | 0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 66.1 | 62.6 | 0.08 | 66.1 | 68.0 | 0.04 |

| Unknown | 28.1 | 27.9 | 0.005 | 28.1 | 26.2 | 0.04 |

| Ethnic grouping (%) | ||||||

| Asian | 4.6 | 4.5 | 0.003 | 4.6 | 4.0 | 0.03 |

| Black | 15.5 | 17.8 | 0.06 | 15.5 | 15.3 | 0.007 |

| White | 64.5 | 61.6 | 0.06 | 64.5 | 66.0 | 0.03 |

| Unknown | 13.7 | 15.0 | 0.04 | 13.7 | 13.1 | 0.02 |

| Marital status (%) | ||||||

| Never married | 9.4 | 10.1 | 0.03 | 9.4 | 9.5 | 0.005 |

| Divorced | 4.8 | 4.4 | 0.02 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 0.02 |

| Widowed | 5.0 | 6.5 | 0.07 | 5.0 | 5.8 | 0.04 |

| Adverse socioeconomic determinants of health, personal and family history, lifestyle factors (%) | 2.4 | 2.1 | 0.02 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 0.009 |

| Personal history of psychological trauma | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.002 |

| Family history of mental and behavioral disorders | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.001 |

| Lifestyle-related problems | 5.8 | 4.4 | 0.06 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 0.01 |

| Pre-existing medical conditions (%) | ||||||

| Depression | 17.9 | 12.8 | 0.14a | 17.9 | 17.9 | <0.001 |

| Mood disorders, including bipolar disorders | 21.1 | 15.1 | 0.16a | 21.1 | 21.0 | 0.001 |

| Anxiety, dissociative, somatoform and other nonpsychotic mental disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder | 21.9 | 14.4 | 0.19a | 21.9 | 21.6 | 0.007 |

| Schizophrenia, schizotypal, delusional and other non-mood psychotic disorders | 1.1 | 1.8 | 0.06 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.02 |

| Behavioral disorders, including sleep disorders | 4.7 | 2.5 | 0.12a | 4.7 | 4.6 | 0.007 |

| Disorders of adult personality and behavior, including impulse and gender identity disorders | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.003 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.002 |

| Symptoms and signs involving an emotional state | 2.4 | 2.1 | 0.02 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 0.007 |

| Sleeping disorders including insomnia | 29.4 | 16.8 | 0.30a | 29.4 | 29.1 | 0.006 |

| Chronic pain | 17.1 | 11.2 | 0.17a | 17.1 | 16.9 | 0.007 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 2.2 | 3.1 | 0.06 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 0.009 |

| Tobacco use disorder | 12.1 | 11.4 | 0.02 | 12.1 | 11.4 | 0.02 |

| Opioid use disorder | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.005 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.01 |

| Cannabis use disorder | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.03 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.01 |

| Cocaine use disorder | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.02 |

| Other stimulant-related disorders | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.004 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.003 |

| Other psychoactive substance-related disorders | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.02 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.01 |

| Overweight and obesity | 46.3 | 23.5 | 0.49a | 46.3 | 47.0 | 0.01 |

| Cancer | 28.4 | 23.5 | 0.11a | 28.4 | 28.0 | 0.007 |

| Traumatic brain injury | 1.5 | 1.6 | 0.01 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.008 |

| Previous medication prescription or procedures (%) | ||||||

| Bariatric surgery | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.09 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 0.002 |

| Antidepressants | 29.8 | 20.7 | 0.21a | 29.8 | 29.6 | 0.005 |

| Antipsychotics | 10.8 | 9.1 | 0.06 | 10.8 | 10.1 | 0.02 |

| Antiepileptics | 26.6 | 19.5 | 0.17a | 25.7 | 25.6 | 0.001 |

| Benzodiazepine-derivative sedatives or hypnotics | 36.2 | 28.5 | 0.17a | 36.2 | 35.4 | 0.02 |

| Esketamine | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.002 |

| Ketamine | 2.8 | 2.1 | 0.05 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 0.007 |

| Lithium | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.005 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.01 |

| Bupropion | 6.3 | 3.1 | 0.15a | 6.3 | 6.4 | 0.001 |

| Naltrexone | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.08 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.002 |

| Phentermine | 2.0 | 0.4 | 0.15a | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.004 |

| Orlistat | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.009 |

| Topiramate | 3.2 | 1.3 | 0.12a | 3.0 | 3.2 | 0.009 |

| Insulin | 43.0 | 22.1 | 0.46a | 43.0 | 43.6 | 0.01 |

| Metformin | 60.0 | 27.3 | 0.70a | 60.0 | 61.5 | 0.03 |

| Alpha glucosidase inhibitors | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.04 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.005 |

| DPP-4 inhibitors | 21.6 | 6.4 | 0.45a | 21.6 | 21.6 | <0.001 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 17.9 | 1.5 | 0.56a | 17.9 | 16.6 | 0.04 |

| Sulfonylureas | 28.0 | 13.1 | 0.38 | 27.9 | 28.3 | 0.008 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 6.6 | 2.9 | 0.17a | 6.6 | 6.7 | 0.003 |

The status of variables was based on the presence of related clinical codes any time to 1 day before the index event.

SMD greater than 0.1, a threshold indicating group imbalance.

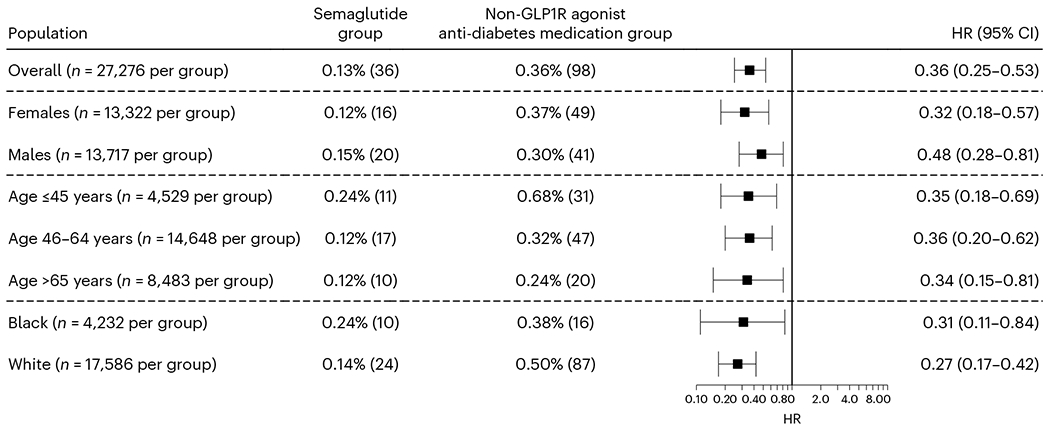

The mean follow-up time for patients with T2DM and no previous history of suicidal ideation was 172.9 ± 7.8 days for the semaglutide group and 167.2 ± 13.0 days for the non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication group. The semaglutide group had a significantly lower risk for incident suicidal ideation than the matched non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication group (0.13% versus 0.36%; HR = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.25–0.53). Consistent lower risks were seen in patients stratified according to sex, age subgroup and ethnic grouping (Fig. 3). The number of patients who had a suicide attempt during the 6-month follow-up in both groups was between 1 and 9, but the actual number was not reported because of privacy concerns.

Fig. 3|. Incident suicidal ideations in the study population with T2DM.

Comparison of incident (first-time experience) suicidal ideation In the study population with T2DM and no history of suicidal ideation before the index event of the first prescription of semaglutide or other non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medications that occurred from 1 December 2017 through to 31 May 2021 between the propensity score-matched semaglutide and non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication groups within the 6-month time window after the index event. For each group, the overall risk (number of cases) is shown, where overall risk is defined as the number of patients with outcomes during the 6-month time window divided by number of patients in the group at the beginning of the time window. HRs were calculated using Kaplan–Meier analysis to estimate the probability of outcome at daily time intervals with censoring applied.

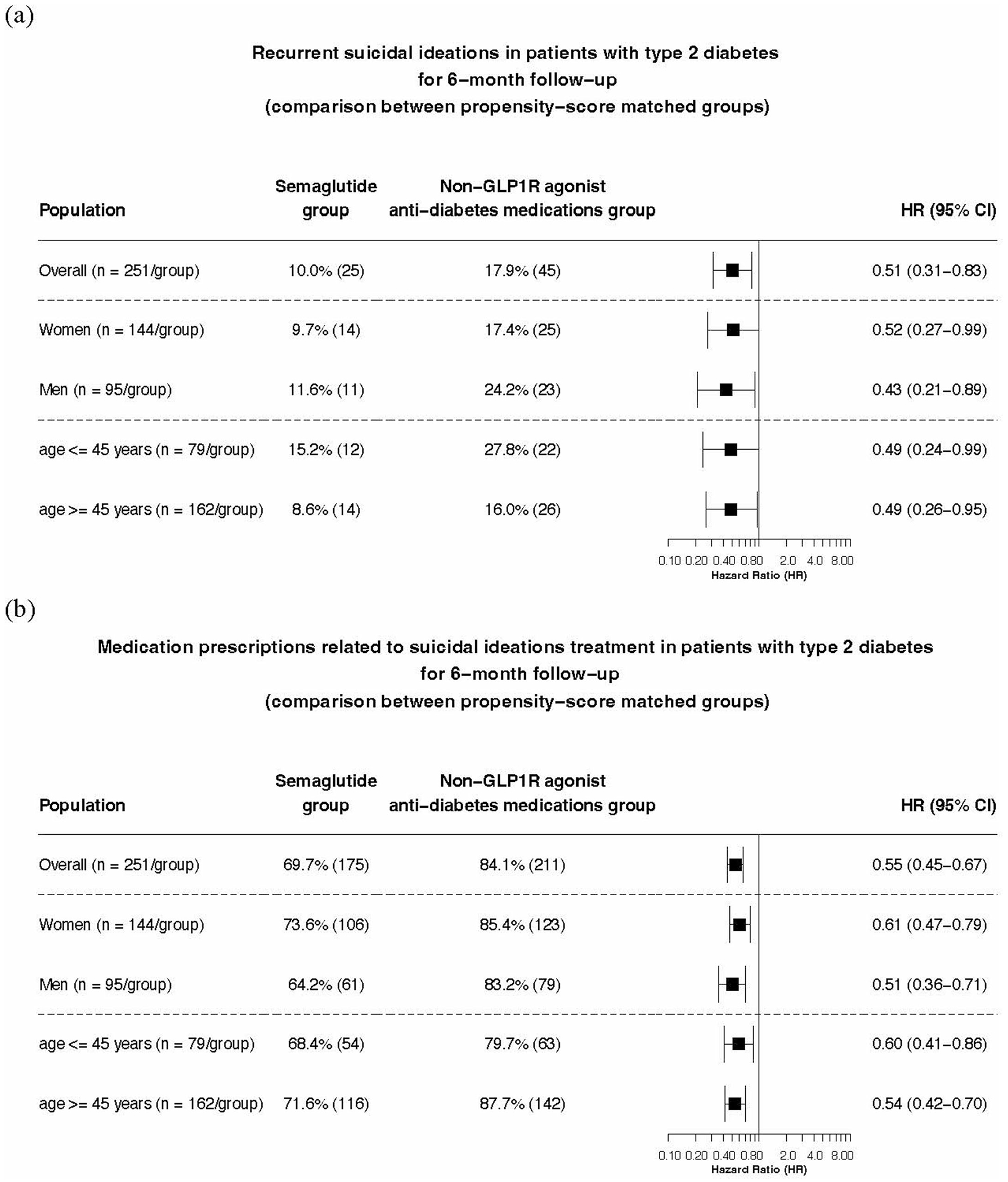

For the analysis of recurrent suicidal ideation in patients with T2DM, the study population consisted of 16,970 patients with T2DM who had a previous history of suicidal ideation. The semaglutide group compared to the non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication group had a similar age, included more females and White individuals, had a higher prevalence of obesity, cancer, chronic pain, mental, behavioral and sleep disorders, a previous history of suicide attempts and intentional self-harm, lower prevalence of substance use disorders and higher prevalence of previous prescriptions of non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medications. After propensity score matching, the two groups (251 in each group, mean age 50.0 years, 62.0% females, 8.4% Hispanic, 11.6% Black) were balanced (Extended Data Table 2).

The mean follow-up time for patients with T2DM and a previous history of suicidal ideation was 165.9 ± 14.1 days for the semaglutide group and 144.6 ± 31.6 days for the non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication group. The semaglutide group was associated with a significantly lower risk for recurrent suicidal ideation compared to the matched non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication group (10.0% versus 17.9%; HR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.31–0.83). Consistent lower risk was seen in patients stratified according to sex and age group (Extended Data Fig. 1). The semaglutide group had lower medication prescriptions related to suicidal ideation treatment compared to the matched non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication group (69.7% versus 84.1%, HR = 0.55, 95% CI = 0.45–0.67), which was consistent in patients stratified according to sex and age subgroup (Extended Data Fig. 1). The number of patients who had a suicide attempt during the 6-month follow-up in both groups was between 1 and 9, but the actual number was not reported because of privacy concerns.

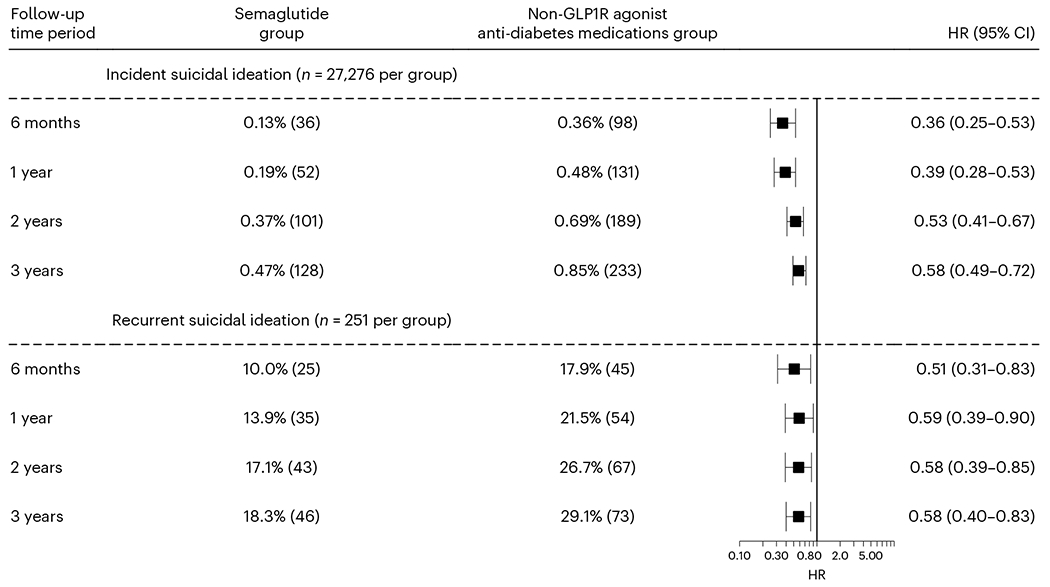

We then examined the association of semaglutide prescription with both incident and recurrent suicidal ideation in patients with T2DM for longer follow-ups (1, 2 and 3 years). Compared with non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medications, semaglutide was associated with a lower risk of incident suicidal ideation at longer follow-ups. Similar associations were observed at the 1-year follow-up (HR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.28–0.53) compared to the 6-month follow-up. At the 3-year follow-up (mean 804.7 ± 156.6 and 859.7 ± 181.0 follow-up days for the semaglutide group and non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication group, respectively), the associations were attenuated but remained significant, with CIs overlapping with those for the 6-month follow-up (HR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.49–0.72). The association for the 2-year follow-up was similar to that for the 3-year follow-up (HR = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.41–0.67). The associations of semaglutide with recurrent suicidal ideation at the 2-and 3-year follow-ups (mean 769.5 ± 213.5 and 683.6 ± 279.7 follow-up days for the semaglutide group and non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication group, respectively) were similar to that at the 6-month follow-up (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4|. Incident and recurrent suicidal ideations in the study population with T2DM at different follow-up time periods.

Comparison of incident and recurrent suicidal ideation in the study population with T2DM between the propensity score-matched semaglutide and non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication groups at different follow-up time windows (up to 3 years). For each group, the overall risk (number of cases) is shown, where overall risk is defined as the number of patients with outcomes during the 6-month time window divided by the number of patients in the group at the beginning of the time window. HRs were calculated using Kaplan–Meier analysis to estimate the probability of outcome at daily time intervals with censoring applied.

Discussion

Contrary to reports of increases in suicidal ideation with semaglutide, our analyses revealed a lower risk for both incidence and recurrence of suicidal ideation in patients prescribed semaglutide compared with non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity and anti-diabetes medications. We performed analyses in two separate groups involving patients with overweight and obesity, and in patients with T2DM, from two nonoverlapping periods (from June 2021 through to December 2022 for patients with overweight or obesity and from December 2017 through to May 2021 for patients with T2DM). The characteristics of the group with T2DM (mean age 57.5 years, 49.2% female, 5.8% Hispanic, 15.4% Black) were different from those of the patients in the group with overweight or obesity (mean age 50.1 years, 72.6% female, 7.4% Hispanic, 16.0% Black); however, the semaglutide-associated lower risk of incident and recurrent suicidal ideation compared to non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity or anti-diabetes medications were similar. Thus, our results do not support the concerns of increased suicidal risk associated with semaglutide raised by the EMA and Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency in the United Kingdom12. This highlights the need for a more detailed evaluation of the previously reported cases.

The association between obesity and suicidality is not clear. A recent systematic review reported that while six of eight studies reported a lower risk for suicide in individuals with obesity than those without, one study reported increased risk while another study did not report a relationship17. This same systematic review reported that for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, the risk differed according to sex such that females with obesity had a higher risk than males with obesity. Studies on obesity treatments reported an increased risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, particularly after bariatric surgery18,19; one study reported an association for some anti-obesity medications20. Mental health disorders, including depression and suicidal ideation, are more prevalent in individuals with T2DM than in the general population21, emphasizing the importance of disease management through informed anti-diabetes medication choices.

Our study has several limitations: this was a retrospective observational study, so no causal inferences can be drawn. Furthermore, patients in the TriNetX database (https://trinetx.com/) represented those who had medical encounters with healthcare systems contributing to the TriNetX platform. Even though this platform includes over 100 million patients in the United States, it does not necessarily represent the entire US population. Therefore, results from the TriNetX platform need to be validated in other populations.

There are limitations inherent to observational studies and studies based on patient EHRs, including overdiagnosis, misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis, unmeasured or uncontrolled confounders, self-selection and reverse causality. For example, when initiating semaglutide, some healthcare providers are more closely involved in the early stages to ensure proper injection techniques. It is possible that the increased interactions might have led to better outcomes, thus influencing the rates of suicidal ideation. Alternatively, they might have strengthened trust and facilitated the willingness of a patient to report suicidal ideation. Future controlled trials are necessary to assess any causal relationships between semaglutide with suicidal ideation.

In our study, the follow-up time for the main analyses was 6 months. Semaglutide was approved as a weight management medication in June 2021. The study period for the study population of patients with overweight or obesity ran from 1 June 2021 through to 31 December 2022; this provided us with large-enough cohort and a sufficient sample size, while allowing us to have a 6-month follow-up for all patients for data analyses on 1 September 2023. However, a major issue with short follow-up time windows is reverse causality22 whereby undiagnosed suicidal ideation and related medical conditions might have impacted the choice of semaglutide versus non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity and anti-diabetes medications. In the study population with T2DM in whom we conducted a longer follow-up to 3 years, we observed consistently lower risks in both incident and recurrent suicidal ideation. Although this longer time frame might have mitigated the likelihood of reverse causality, biases may have remained; future studies should evaluate longer-term associations of semaglutide with suicidal ideation in the study population with overweight or obesity and in patients with T2DM.

EHR data had limited information on semaglutide brand names and dosage information: 57.1% had unknown dosage and 70.8% had unknown brand name information. Because of limited sample sizes at the time of our study, we could not directly compare dosage effects and the association of semaglutide with suicidal ideation in the same study population. The higher-dose format of semaglutide as Wegovy was approved for weight management (recommended dose of 2.4 mg administered subcutaneously once a week); the lower-dose format of semaglutide as Ozempic was approved for the treatment of T2DM (recommended dose for the subcutaneous formulation = 0.5–1 mg once a week). We observed stronger associations of semaglutide with suicidal ideation in the population with overweight or obesity than in the population with T2DM, which could suggest a potential dose effect. However, the characteristics of the study populations, comparators and study periods were different.

We were unable to assess patients’ medication adherence based on their EHRs. Patients may discontinue using the drug for reasons such as financial burden, drug side effects or lack of efficacy. One study showed that adherence with semaglutide was greater than other GLP1R agonists in patients with T2DM23. However, adherence to semaglutide compared to non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes or anti-obesity medications is unknown. In our study, both study populations included patients who had recent medical encounters when the diagnosis of obesity or overweight, or T2DM, was made and were subsequently prescribed semaglutide or non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity or anti-diabetes medications, suggesting that patients with active obesity or overweight or T2DM needed medical attention and treatment. However, we could not directly control for patient adherence to medications in this study. In addition, we could not directly control for disease severity and how well medical conditions were managed, including diabetes duration, glycemic control, body mass index and lipid profile, which could have confounded the findings.

Finally, this study was focused on suicidal ideation as an analysis outcome. While we also assessed the associations of semaglutide with suicide attempt, sample sizes were too small for statistical evaluation. Because suicide attempt is critically different from suicidal ideation24, future studies should continue to evaluate the associations between semaglutide and suicide attempt and non-suicidal self-injury.

In conclusion, our analyses do not support concerns of increased risk of suicidal ideation with semaglutide and instead show a lower risk association of semaglutide with both incident and recurrent suicidal ideation compared to non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity and anti-diabetes medications. Further studies should evaluate the association of semaglutide and other GLP1R agonist medications with the incidence and recurrence of suicidality in other at-risk populations.

Methods

Data

The data used in this study were collected and analyzed on 1 September 2023 within the TriNetX Analytics platform based on the Research US Collaborative Network. We used the TriNetX platform to access the aggregated, de-identified EHRs of 100.8 million patients from 59 healthcare organizations in the United States across 50 states, covering diverse geographical regions, age, ethnicity, income and insurance groups, and clinical setting. The geographical distribution of patients from the TriNetX platform is 25% in the Northeast, 17% in the Midwest, 41% in the South and 12% in the West, with 5% unknown.

TriNetX is a platform that de-identifies and aggregates EHR data from contributing healthcare systems, most of which are large academic medical institutions with both inpatient and outpatient facilities at multiple locations across all 50 states in the United States. TriNetX Analytics provides Web-based and secure access to patient EHR data from hospitals, primary care and specialty treatment providers, covering diverse geographical locations, age groups, ethnic groups, income levels and insurance types, including several commercial insurances, governmental insurance (Medicare and Medicaid), self-pay and uninsured, worker compensation insurance, and military and Veterans Affairs insurance, among others.

Self-reported sex (female, male), ethnic grouping and ethnicity data in TriNetX comes from the underlying clinical EHR systems of the contributing healthcare systems. TriNetX maps race and ethnicity data from the contributing healthcare systems to the following categories: (1) race: Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other, White, unknown; and (2) ethnicity: Hispanic or Latino, non-Hispanic or Latino, unknown ethnicity.

TriNetX carries out an intensive data preprocessing stage to minimize missing values. TriNetX maps the data to a consistent clinical data model with a consistent semantic meaning so that the data can be queried consistently regardless of the underlying data source(s). All covariates are either binary, categorical, which is expanded to a set of binary columns, or continuous but essentially guaranteed to exist. Age is guaranteed to exist. Missing sex values are represented using ‘unknown sex’. The missing data for ethnic grouping and ethnicity are presented as ‘unknown race’ or ‘unknown ethnicity’. For other variables, including medical conditions, procedures, laboratory tests and socioeconomic determinant health, the value is either present or absent, so ‘missing’ is not pertinent.

Ethics statement

TriNetX is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Any data displayed on the TriNetX platform in aggregate form, or any patient-level data provided in a dataset generated by the TriNetX platform, only contains de-identified data as per the de-identification standard defined in Section 164.514(a) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. TriNetX built-in analytical functions (for example, incidence, prevalence, outcomes analysis, survival analysis, propensity score matching) allow for patient-level analyses, while only reporting population-level data. The MetroHealth System institutional review board-determined research using de-identified aggregated data on the TriNetX platform, in the ways described in this article, is not human subject research. The TriNetX platform has been successfully used in retrospective cohort studies25–35, including evaluating the risks and benefits of FDA-approved medications in real-world populations33,36–39. This study fully complies with the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology statement.

Statistical analysis

Study population with overweight or obesity.

To assess the incidence of suicidal ideation in patients with overweight or obesity, the study population consisted of 232,771 patients with overweight or obesity who were prescribed semaglutide (Wegovy) or non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medications (bupropion, naltrexone, orlistat, topiramate, phentermine, setmelanotide)40 from 1 June 2021 through to 31 December 2022 and who had medical encounters for the diagnosis of overweight or obesity within 1 month before being prescribed anti-obesity medication, had no history of suicidal ideation before being prescribed the medication and were never prescribed other GLP1R agonist medications. The start date of June 2021 was chosen because semaglutide was approved in the United States for weight management in June 2021. The ending date of 31 December 2022 was chosen to allow for a 6-month follow-up by the time of data collection and analysis in September 2023. This study population was then divided into two groups: (1) a semaglutide group, 67,804 patients prescribed semaglutide; and (2) a non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication group, 164,967 patients prescribed non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medications but not semaglutide.

To assess the recurrence of suicidal ideation in patients with overweight or obesity, the study population consisted of 7,847 patients with overweight or obesity who were prescribed semaglutide (Wegovy) or non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medications from 1 June 2021 through to 31 December 2022, had medical encounters for overweight or obesity diagnosis within 1 month before being prescribed the medication, had a history of suicidal ideation before being prescribed anti-obesity medication and were never prescribed other GLP1R agonist medications. This study population was divided into two groups: (1) a semaglutide group, 893 patients prescribed semaglutide; and (2) a non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medication group, 6,954 patients prescribed non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity medications but not semaglutide.

Study population with T2DM.

To assess the incidence of suicidal ideation in patients with T2DM, the study population consisted of 1,572,885 patients with T2DM who were prescribed semaglutide (Ozempic) or non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medications from 1 December 2017 through to 31 May 2021, had medical encounters for T2DM within 1 month before being prescribed the medication, had no history of suicidal ideation before being prescribed anti-diabetes medication and were never prescribed other GLP1R agonist medications. The status of non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medications was determined according to the ATC code A10 ‘Drugs used in diabetes’ with GLP1R agonists (ATC code A10BJ ‘Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogues’) excluded. The list of non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medications included insulin (ATC code A10A ‘Insulins and analogues’), metformin (ATC code A10BA ‘Biguanides’), sulfonylureas (ATC code A10BB ‘Sulfonylureas’), alpha glucosidase inhibitors (ATC code A10BF ‘Alpha glucosidase inhibitors’), thiazolidinediones (ATC code A10BG ‘Thiazolidinediones’), DPP-4 inhibitors (ATC code A10BH ‘Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors’) and SGLT2 inhibitors (ATC code A10BK ‘Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors’) (Extended Data Table 3). The study starting date of December 2017 was chosen because semaglutide was approved in the United States as Ozempic for T2DM in December 2017, earlier than its approval for weight management as Wegovy in June 2021. The ending date of May 2021 was chosen to allow us to separately examine the associations of semaglutide with suicidal ideation as Ozempic from those in the study population with overweight or obesity prescribed Wegovy. This study population was divided into two groups: (1) a semaglutide group, 27,282 patients prescribed semaglutide; and (2) a non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medications group, 1,545,603 patients prescribed non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medications but not semaglutide.

To assess the recurrence of suicidal ideation in patients with T2DM, the study population consisted of 16,970 patients with T2DM who were prescribed Ozempic or non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medications from 1 December 2017 through to 31 May 2021, had medical encounters for T2DM within 1 month before being prescribed the medication, had a history of suicidal ideation before being prescribed the medication and were never prescribed other GLP1R agonist medications. This study population was divided into two groups: (1) a semaglutide group, 253 patients prescribed semaglutide; and (2) a non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medication group, 16,717 patients prescribed non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medications but not semaglutide.

For each study population, the semaglutide and the non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity or anti-diabetes medication groups were propensity score-matched (1:1 using nearest neighbor greedy matching with a caliper of 0.25 times the s.d.) on covariates that are potential risk factors for suicidal ideation41,42, including demographics (age, sex, ethnic grouping/ethnicity, marriage status); adverse socioeconomic determinants of health (for example, education, unemployment, upbringing, social and psychosocial environment, and housing); lifestyle problems (for example, smoking, gambling and betting, exercise, diet); substance use disorders (for example, alcohol, tobacco or other nicotine products, cannabis, cocaine, stimulants); psychiatric comorbidities (for example, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders); behavior disorders (for example, eating or sleep disorders); chronic pain, cancers, traumatic brain injury and bariatric surgery; previous medication prescriptions for obesity and T2DM for all groups; previous suicide attempt and intentional self-harm; and pharmacotherapies for suicidal ideation for the groups to evaluate the recurrence of suicidal ideation (Extended Data Table 3).

The outcome–first or recurrent suicidal ideation–that occurred in the 6-month time window after the index event (prescription of semaglutide versus non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity or anti-diabetes medications) were compared between the matched semaglutide and non-GLP1R agonist anti-obesity or anti-diabetes medication groups. The status of suicidal ideation was based on the presence or absence of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code R45.851 ‘Suicidal ideations’ recorded in patient EHRs. For ICD-10 code R45.852 suicidal ideation is diagnosed if a patient expresses thoughts about suicide (fleeting or sustained), including planning how to proceed with a suicide or acting on it but surviving because of failure of the method chosen or because of early discovery. To evaluate the associations of semaglutide with the recurrence of suicidal ideation, an additional outcome—prescription of medication related to suicidal ideation pharmacotherapy (esketamine, ketamine, lithium, antidepressants, antipsychotics, antiepileptics, benzodiazepines and hypnotics)43—was examined.

An additional outcome–first experience of suicide attempt (ICD-10 code T14.91 ‘Suicide attempt’)–was examined for the study population with overweight or obesity who had no previous history of suicidal ideations or suicide attempt, but not in other groups because of small sample sizes. Because of privacy concerns, groups of 1–9 cases were rounded up to 10 to protect patient information. For groups other than the study population with overweight or obesity who had no previous history of suicidal ideation or suicide attempt, the number of patients whose outcome was suicide attempt was 10,; this could be any number from 1 to 10.

For the study population with T2DM, the index event was the first prescription of semaglutide versus non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medications, occurring from 1 December 2017 through to 31 May 2021. To examine longer-term associations of semaglutide prescription with suicidal ideation, the outcome, that is, first and recurrent experience of suicidal ideation, in patients with T2DM was further followed for 1, 2 and 3 years starting from the index event.

Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to estimate the probability of outcome at daily time intervals with censoring applied. When the last fact (outcomes of interest or other medical encounters) in the patient’s record was in the time window for analysis, the patient was censored on the day after the last fact in their record. HRs and 95% CIs were used to describe the relative hazard of the outcomes based on a comparison of time-to-event rates. Separate analyses were performed in patients stratified according to sex (female, male), age subgroups (≤45, 46–64, ≥65 years), ethnic grouping and ethnicity (Black, White, Hispanic). Data were collected and analyzed on 1 September 2023 within the TriNetX Analytics platform.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1|. Comparison of (a) recurrent suicidal ideations and (b) medication prescriptions for suicidal ideations treatments in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) who had a prior history of suicidal ideations between propensity-score matched semaglutide and non-GLP1R agonist anti-diabetes medications groups for 6-month follow-up period.

For each group, overall risk (# of cases) is also shown, where overall risk is defined as the number of patients with outcomes during the 6-month follow-up period/number of patients in the cohort at the beginning of the follow-up time period.

Extended Data Table 1|.

Characteristics of the semaglutide and non-GLP1R agonists anti-obesity medications groups for patients with overweight or obesity who had a prior history of suicidal ideations

| Before Propensity-Score Matching | After Propensity-Score Matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semaglutide | Non-GLP1R agonists anti-obesity medications | SMD | Semaglutide | Non-GLP1R agonists anti-obesity medications | SMD | |

| Total number | 893 | 6,954 | 865 | 865 | ||

| Age at index event (years, mean±standard deviation) | 44.7 ± 14.1 | 41.8 ± 15.5 | 0.20* | 44.3 ± 14.0 | 44.6 ± 15.7 | 0.02 |

| Sex (%) | ||||||

| Female | 71.7 | 67.0 | 0.10* | 71.7 | 72.5 | 0.02 |

| Male | 28.3 | 32.8 | 0.10* | 28.3 | 27.3 | 0.02 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 6.9 | 8.3 | 0.05 | 6.7 | 6.8 | 0.005 |

| Not Hispanic/Latinx | 82.9 | 82.8 | 0.003 | 83.0 | 80.5 | 0.07 |

| Unknown | 10.2 | 9.0 | 0.04 | 10.3 | 12.7 | 0.08 |

| Race (%) | ||||||

| Asian | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.07 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.01 |

| Black | 13.4 | 15.0 | 0.04 | 13.8 | 13.8 | <.001 |

| white | 74.4 | 72.7 | 0.04 | 74.3 | 74..1 | 0.005 |

| Unknown | 10.1 | 10.2 | 0.005 | 10.2 | 11.1 | 0.03 |

| Marital status (%) | ||||||

| Never Married | 19.6 | 24.3 | 0.11* | 19.7 | 16.9 | 0.07 |

| Divorced | 8.3 | 7.4 | 0.03 | 8.4 | 9.5 | 0.04 |

| Widowed | 2.9 | 1.8 | 0.07 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 0.007 |

| Adverse socioeconomic determinants of health (%) | 34.2 | 39.4 | 0.11* | 34.1 | 33.2 | 0.02 |

| Personal history of psychological trauma (%) | 8.5 | 8.9 | 0.02 | 8.6 | 8.4 | 0.004 |

| Family history of mental and behavioral disorders (%) | 15.3 | 17.7 | 0.06 | 15.4 | 14.3 | 0.03 |

| Problems related to lifestyle (%) | 30.1 | 32.0 | 0.04 | 29.9 | 29.7 | 0.005 |

| Pre-existing medical conditions (%) | ||||||

| Depression | 88.7 | 87.7 | 0.03 | 88.3 | 89.2 | 0.03 |

| Mood disorders including bipolar disorders | 96.0 | 96.3 | 0.02 | 95.8 | 96.3 | 0.02 |

| Anxiety | 89.7 | 90.1 | 0.01 | 89.6 | 90.6 | 0.04 |

| psychotic disorders | 21.7 | 24.8 | 0.07 | 21.8 | 22.2 | 0.008 |

| Behavioral disorders including sleep disorders | 30.8 | 25.2 | 0.13* | 30.6 | 29.7 | 0.02 |

| Disorders of adult personality and behavior | 27.9 | 27.7 | 0.005 | 27.7 | 27.3 | 0.01 |

| Sleeping disorders including insomnia | 71.3 | 61.6 | 0.21* | 70.5 | 72.4 | 0.04 |

| Suicide attempt | 6.2 | 7.4 | 0.05 | 6.4 | 5.0 | 0.06 |

| Intentional self-harm | 4.8 | 8.4 | 0.15* | 4.7 | 3.7 | 0.05 |

| Personal history of self-harm | 20.0 | 27.6 | 0.18* | 20.5 | 19.1 | 0.04 |

| Chronic pain | 53.2 | 46.6 | 0.13* | 52.4 | 54.5 | 0.04 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 20.5 | 32.8 | 0.26* | 20.8 | 21.5 | 0.02 |

| Tobacco use disorder | 38.9 | 46.7 | 0.16* | 39.0 | 37.0 | 0.04 |

| Opioid use disorder | 11.3 | 17.6 | 0.18* | 11.6 | 12.5 | 0.03 |

| Cannabis use disorder | 16.9 | 22.6 | 0.14* | 17.2 | 17.7 | 0.01 |

| Cocaine use disorder | 6.7 | 12.2 | 0.19* | 6.8 | 7.3 | 0.02 |

| Other stimulant disorders | 8.0 | 11.7 | 0.13* | 8.0 | 7.2 | 0.03 |

| Other psychoactive substance related disorders | 16.0 | 23.4 | 0.19* | 16.3 | 17.6 | 0.03 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 56.2 | 25.6 | 0.66* | 54.8 | 55.4 | 0.01 |

| Cancer | 42.2 | 32.7 | 0.20* | 41.3 | 43.6 | 0.05 |

| Traumatic brain injury | 11.0 | 10.4 | 0.02 | 10.8 | 10.6 | 0.004 |

| Prior medication prescription or procedures (%) | ||||||

| Bariatric surgery | 7.7 | 6.5 | 0.05 | 7.9 | 7.1 | 0.03 |

| Antidepressants | 91.7 | 91.0 | 0.03 | 91.4 | 92.0 | 0.02 |

| Antipsychotics | 72.2 | 75.0 | 0.06 | 72.8 | 75.5 | 0.06 |

| Antiepileptics | 77.9 | 73.0 | 0.11* | 77.6 | 78.3 | 0.02 |

| Bezodiazepine derivative sedatives/hypnotics | 83.3 | 79.0 | 0.11* | 83.0 | 83.9 | 0.03 |

| Esketamine | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.04 | 1.2 | 1.2 | <.001 |

| Ketamine | 13.8 | 12.1 | 0.05 | 13.3 | 14.3 | 0.03 |

| Lithium | 2.4 | 3.0 | 0.04 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 0.02 |

| Bupropion | 41.7 | 45.1 | 0.07 | 42.4 | 45.4 | 0.07 |

| Naltrexone | 8.8 | 10.5 | 0.06 | 9.0 | 8.2 | 0.03 |

| Phentermine | 10.4 | 6.1 | 0.16* | 10.4 | 10.8 | 0.01 |

| Orlistat | 1.9 | 0.7 | 0.11* | 1.6 | 1.7 | 0.009 |

| Topiramate | 26.2 | 27.6 | 0.03 | 26.7 | 25.7 | 0.02 |

| Insulins | 36.4 | 17.8 | 0.43* | 34.6 | 34.8 | 0.005 |

| Metformin | 54.4 | 20.1 | 0.76* | 53.1 | 50.8 | 0.05 |

| Alpha glucosidase inhibitors | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.11* | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.07 |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors | 10.5 | 2.2 | 0.35* | 9.0 | 9.2 | 0.008 |

| Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors | 9.9 | 1.8 | 0.35* | 8.7 | 8.6 | 0.004 |

| Sulfonylureas | 16.6 | 4.3 | 0.41* | 15.3 | 16.2 | 0.03 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 2.7 | 1.0 | 0.13* | 2.7 | 2.2 | 0.03 |

SMD – standardized mean differences.

SMD greater than 0.1, indicating cohort imbalance.

Extended Data Table 2|.

Characteristics of the semaglutide and non-GLP1R agonists anti-diabetes medications groups for the study population of patients with T2DM who had a prior history of suicidal ideations

| Before Propensity-Score Matching | After Propensity-Score Matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semaglutide | Non-GLP1R agonists anti-diabetes medications | SMD | Semaglutide | Non-GLP1R agonists anti-diabetes medications | SMD | |

| Total number | 253 | 16,717 | 251 | 251 | ||

| Age at index event (years, mean±standard deviation) | 50.0 ± 13.2 | 51.23± 15.1 | 0.09 | 50.0 ± 13.3 | 49.9 ± 14.5 | 0.01 |

| Sex (%) | ||||||

| Female | 60.1 | 48.1 | 0.24* | 59.8 | 62.2 | 0.05 |

| Male | 39.9 | 51.8 | 0.24* | 40.2 | 37.8 | 0.05 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 9.1 | 10.1 | 0.03 | 9.2 | 7.6 | 0.06 |

| Not Hispanic/Latinx | 75.1 | 72.0 | 0.07 | 75.3 | 74.1 | 0.03 |

| Unknown | 15.8 | 17.9 | 0.06 | 15.5 | 18.3 | 0.07 |

| Race (%) | ||||||

| Asian | 6.3 | 2.3 | 0.20* | 6.0 | 6.8 | 0.03 |

| Black | 11.9 | 23.8 | 0.32* | 12.0 | 11.2 | 0.03 |

| white | 64.8 | 59.4 | 0.11* | 65.3 | 64.9 | 0.008 |

| Unknown | 14.2 | 12.8 | 0.04 | 13.9 | 13.9 | <.001 |

| Marital status (%) | ||||||

| Never Married | 19.4 | 20.1 | 0.02 | 19.5 | 17.1 | 0.06 |

| Divorced | 7.5 | 8.4 | 0.03 | 7.6 | 11.2 | 0.12* |

| Widowed | 4.0 | 4.0 | 0.001 | 4.0 | 4.0 | <.001 |

| Adverse socioeconomic determinants of health (%) | 27.7 | 27.6 | 0.002 | 27.9 | 25.1 | 0.06 |

| Personal history of psychological trauma (%) | 4.0 | 4.4 | 0.02 | 4.0 | 4.0 | <.001 |

| Family history of mental/behavioral disorders (%) | 8.7 | 8.1 | 0.02 | 8.8 | 8.0 | 0.03 |

| Problems related to lifestyle (%) | 24.9 | 19.7 | 0.13* | 24.7 | 21.1 | 0.09 |

| Pre-existing medical conditions (%) | ||||||

| Depression | 84.6 | 75.4 | 0.23* | 84.5 | 80.5 | 0.11* |

| Mood disorders including bipolar disorders | 94.1 | 87.7 | 0.22* | 94.0 | 92.4 | 0.06 |

| Anxiety | 78.7 | 70.4 | 0.19* | 78.9 | 79.3 | 0.01 |

| Schizophrenia, schizotypal, delusional, and other non-mood psychotic disorders | 26.1 | 32.5 | 0.14* | 25.9 | 27.1 | 0.03 |

| Behavioral disorders | 23.7 | 10.7 | 0.35* | 23.5 | 20.7 | 0.07 |

| Disorders of adult personality and behavior | 25.3 | 19.8 | 0.13* | 25.1 | 23.5 | 0.04 |

| Sleeping disorders including insomnia | 668 | 42.6 | 0.50* | 66.9 | 66.5 | 0.008 |

| Suicide attempt | 7.9 | 3.6 | 0.19* | 8.0 | 5.2 | 0.11* |

| Intentional self-harm | 8.3 | 5.2 | 0.12* | 8.4 | 5.6 | 0.11* |

| Personal history of self-harm | 17.9 | 12.9 | 0.14* | 17.9 | 17.9 | 0.02 |

| Chronic pain | 45.8 | 36.2 | 0.20* | 46.2 | 51.4 | 0.10* |

| Alcohol use disorder | 24.9 | 29.6 | 0.11* | 25.1 | 26.7 | 0.04 |

| Tobacco use disorder | 40.7 | 47.8 | 0.14* | 41.0 | 40.2 | 0.02 |

| Opioid use disorder | 12.3 | 14.2 | 0.06 | 12.4 | 15.9 | 0.10* |

| Cannabis use disorder | 12.3 | 17.6 | 0.15* | 12.4 | 14.7 | 0.07 |

| Cocaine use disorder | 11.9 | 16.9 | 0.15* | 12.0 | 11.2 | 0.03 |

| Other stimulant disorders | 7.5 | 8.2 | 0.03 | 7.6 | 7.6 | <.001 |

| Other psychoactive substance related disorders | 19.0 | 21.3 | 0.06 | 19.1 | 21.1 | 0.05 |

| Overweight and obesity | 75.1 | 43.1 | 0.69* | 74.9 | 79.7 | 0.11* |

| Cancer | 41.9 | 27.3 | 0.31* | 41.4 | 44.2 | 0.06 |

| Traumatic brain injury | 8.7 | 7.7 | 0.04 | 8.8 | 6.4 | 0.09 |

| Prior medication prescription or procedures (%) | ||||||

| Bariatric surgery | 4.0 | 1.8 | 0.13* | 4.0 | 4.0 | <.001 |

| Antidepressants | 87.4 | 72.6 | 0.37* | 87.3 | 87.3 | <.001 |

| Antipsy chotics | 67.6 | 62.4 | 0.11* | 67.7 | 66.5 | 0.03 |

| Antiepileptics | 76.7 | 60.7 | 0.35* | 76.5 | 76.1 | 0.009 |

| Bezodiazepine derivative sedatives/hypnotics | 83.4 | 70.6 | 0.31* | 83.7 | 84.5 | 0.02 |

| Esketamine | 4.0 | 0.7 | 0.22* | 4.0 | 4.0 | <.001 |

| Ketamine | 11.1 | 6.2 | 0.18* | 11.2 | 10.4 | 0.03 |

| Lithium | 4.0 | 1.9 | 0.12* | 4.0 | 4.0 | <.001 |

| Bupropion | 25.7 | 16.2 | 0.24* | 25.5 | 24.3 | 0.03 |

| Naltrexone | 4.0 | 2.4 | 0.26* | 4.0 | 4.0 | <.001 |

| Phentermine | 4.0 | 0.6 | 0.23* | 4.0 | 4.0 | <.001 |

| Orlistat | 4.0 | 0.3 | 0.26* | 4.0 | 4.0 | <.001 |

| Topiramate | 17.4 | 8.3 | 0.27* | 17.1 | 19.1 | 0.05 |

| Insulins | 74.3 | 45.2 | 0.62* | 74.1 | 75.3 | 0.03 |

| Metformin | 72.3 | 39.6 | 0.70* | 72.1 | 72.1 | <.001 |

| Alpha glucosidase inhibitors | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.06 | 0.0 | 0.0 | <.001 |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors | 23.7 | 6.6 | 0.49* | 23.5 | 23.5 | <.001 |

| Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors | 9.1 | 1.2 | 0.37* | 8.4 | 9.2 | 0.03 |

| Sulfonylureas | 31.6 | 15.9 | 0.38* | 31.5 | 33.1 | 0.03 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 7.5 | 3.3 | 0.19* | 7.2 | 6.0 | 0.05 |

SMD – standardized mean differences.

SMD greater than 0.1, indicating cohort imbalance.

Extended Data Table 3|.

Clinical diagnosis, medications, procedures, and other codes

| Suicidal ideations | Suicidal ideations (ICD-10 code: R45.851) |

|---|---|

| Overweight or obesity | Overweight and obesity (ICD-10 code: E66) Body mass index [BMI] 40 or greater, adult (ICD-10 code: Z68.4) Body mass index [BMI] 30-39, adult (ICD-10 code: Z68.3) Body mass index [BMI] 25.0-25.9, adult (ICD-10 code: Z68.25) Body mass index [BMI] 26.0-26.9, adult (ICD-10 code: Z68.26) Body mass index [BMI] 27.0-27.9, adult (ICD-10 code: Z68.27) Body mass index [BMI] 28.0-28.9, adult (ICD-10 code: Z68.28) Body mass index [BMI] 29.0-29.9, adult (ICD-10 code: Z68.29) |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus (ICD-10 code: E11) |

| Other GLP1R agonists medications | lixisenatide (RxNorm code: 1440051), albiglutide (RxNorm code: 1534763), dulaglutide (RxNorm code: 1551291) liraglutide (RxNorm code: 475968), exenatide (RxNorm code: 60548), tirzepatide (RxNorm code: 2601723) |

| Semaglutide | Semaglutide (RxNorm code: 1991302) |

| non-GLP1R agonists anti-obesity medications | Orlistat (RxNorm code: 37925), Phentermine (RxNorm code 8152), Topiramate (RxNorm code 38404), bupropion (RxNorm code 42347), naltrexone (RxNorm code 7243) |

| Non-GLP1R agonists anti-diabetes medications | Drugs used in diabetes (ATC code: A10) with GLP1R agonists excluded |

| Suicidal ideations | Suicidal ideations (ICD-10 code: R45.851) |

| Medications related to suicidal ideation pharmacotherapy | Antidepressants (ATC code: N06A), Antipsychotics (ATC code: N05A), Antiepileptics (ATC code: N03), Benzodiazepine derivative sedatives/hypnotics (VA code: CN302), Esketamine (RxNorm code: 2119365), Ketamine (RxNorm code: 6130), Lithium (RxNorm code:6448) |

| Age at the index event | Age |

| Female | F |

| Male | M |

| Asian | Asian (Demographics: 2028-9) |

| Black or African American | Black or African American (Demographics: 2054-5) |

| white | white (Demographics: 2106-3) |

| Hispanic/Latino | Hispanic or Latino (Demographics: 2135-2) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | Not Hispanic or Latino (Demographics: 2186-5) |

| Unknown race | Unknown Race (Demographics: 2131-1) |

| Unknown ethnicity | Unknown Ethnicity (Demographics: UN) |

| Divorced | Divorced (Demographics: D) |

| Widowed | Widowed (Demographics: W) |

| Never married | Never Married (Demographics: S) |

| Adverse socioeconomic and psychosocial circumstances | Persons with potential health hazards related to socioeconomic and psychosocial circumstances (ICD-10 code: Z55-Z65), including Problems related to education (Z55), employment/unemployment (Z56), housing and economic circumstances (Z59), social environment (Z60), upbringing (Z62), family circumstances (Z63), psychosocial circumstances (Z64, Z65) |

| Personal history of psychological trauma | Personal history of psychological trauma, not elsewhere classified (ICD-10 code: Z91.4) |

| Family history of mental disorders | Family history of mental and behavioral disorders (ICD-10 code: Z81) |

| Problems related to lifestyle | Problems related to lifestyle (ICD-10 code: Z72) |

| Depression | Depressive episode (ICD-10 code: F32) |

| Mood disorders | Mood [affective] disorders (ICD-10 code: F30-F39) |

| Anxiety | Anxiety, dissociative, stress-related, somatoform and other nonpsychotic mental disorders (ICD-10 code: F40-F48) |

| Psychotic disorders | Schizophrenia, schizotypal, delusional, and other non-mood psychotic disorders (ICD-10 code: F20-F29) |

| Behavioral disorders | Behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors (ICD-10 code: F50-F59) |

| Disorders of adult personality and behavior | Disorders of adult personality and behavior (ICD-10 code: F60-F69) |

| Sleeping disorders including insomnia | Sleeping disorders (ICD-10 code: G47) |

| Suicide attempt | Suicide attempt (ICD-10 code: T14.91) |

| Intentional self-harm | Intentional self-harm (ICD-10 code: X71-X83) |

| Personal history of self-harm | Personal history of self-harm (ICD-10 code: Z91.5) |

| Chronic pain | Chronic pain, not elsewhere classified (ICD-10 code: G89.2) |

| Alcohol use disorder | Alcohol use disorders (ICD-10 code: F10) |

| Tobacco use disorder | Nicotine dependence (ICD-10 code: F17) |

| Opioid use disorder | Opioid use disorders (ICD-10 code: F11 |

| Cannabis use disorder | Cannabis use disorders (ICD-10 code: F12) |

| Cocaine use disorder | Cocaine use disorders (ICD-10 code: F14) |

| Other stimulant disorders | Other stimulant disorders (ICD-10 code: F15) |

| Other psychoactive substance use disorders | Other psychoactive substance related disorders (ICD-10 code: F19) |

| Cancer | Neoplasms (ICD-10 code: C00-D49) |

| Traumatic brain injury | Intracranial injury (ICD-10 code: S06) |

| Bariatric surgery | Bariatric surgery (ICD-10 code: Z98.84) |

| Insulins | Insulins and analogues (ATC code: A10A |

| Metformin | Metformin (RxNorm code: 6809) |

| Sulfonylureas | Sulfonylureas (ATC code: A10BB) |

| Alpha glucosidase inhibitors | Alpha glucosidase inhibitors (ATC code: A10BF) |

| Thiazolidinedione | Thiazolidinediones (ATC code: A10BG) |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (dpp-4) inhibitors | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (dpp-4) inhibitors (ATC code: A10BH) |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (sglt2) inhibitors (ATC code: A10BK) |

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (no. AA029831), the National Institute on Aging (nos. AG057557, AG061388, AG062272 and AG07664) and the National Cancer Institute Case Comprehensive Cancer Center (nos. CA221718, CA043703 and CA2332216). The funding sources had no role in the design, execution, analysis, data interpretation or decision to submit the results of this study.

Footnotes

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02672-2.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Code availability

All the statistical analyses in this study, including propensity score matching and Kaplan–Meier survival analyses were conducted using the TriNetX platform with its built-in functions. The data and code needed to reproduce the analyses can be accessed at https://github.com/bill-pipi/semaglutide_suicide.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Extended data is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02672-2.

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02672-2.

Data availability

This study used population-level aggregate and de-identified data collected by the TriNetX Platform, which are available from TriNetX (https://trinetx.com/); however, third-party restrictions apply to the availability of these data. The data were used under license for this study with restrictions that do not allow for data to be redistributed or made publicly available. To gain access to the data, a request can be made to TriNetX (join@trinetx.com), but costs might be incurred and a data-sharing agreement would be necessary. Data specific to this study, including diagnosis codes and group characteristics in aggregated format, are included in the paper as tables, figures and supplementary files.

References

- 1.Ilic M & Ilic I Worldwide suicide mortality trends (2000–2019): a joinpoint regression analysis. World J. Psychiatry 12, 1044–1060 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suicide (WHO, 2023); www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suicide in the World: Global Health Estimates (WHO, 2019); apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326948/WHO-MSD-MER-19.3-eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suicide Data and Statistics (CDC, 2023); www.cdc.gov/suicide/suicide-data-statistics.html [Google Scholar]

- 5.Findlay S. Health policy brief: the FDA’s sentinel initiative. Health Affairs; 10.1377/hpb20150604.936915 (2015). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibbons R, Hur K, Lavigne J, Wang J & Mann JJ Medications and suicide: high dimensional empirical Bayes screening (iDEAS). Harvard Data Sci. Rev 10.1162/99608f92.6fdaa9de (2019). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sam AH, Salem V & Ghatei MA Rimonabant: from RIO to Ban. J. Obes 2011, 432607 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meier JJ GLP-1 receptor agonists for individualized treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 8, 728–742 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vilsbøll T, Christensen M, Junker AE, Knop FK & Gluud LL Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on weight loss: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 344, d7771 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh G, Krauthamer M & Bjalme-Evans M Wegovy (semaglutide): a new weight loss drug for chronic weight management. J. Investig. Med 70, 5–13 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haddad F, Dokmak G, Bader M & Karaman R A comprehensive review on weight loss associated with anti-diabetic medications. Life 13, 1012 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.EMA Statement on Ongoing Review of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists (EMA, 2023); www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-statement-ongoing-review-glp-1-receptor-agonists [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiappini S. et al. Is there a risk for semaglutide misuse? Focus on the Food and Drug Administration’s FDA Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) pharmacovigilance dataset. Pharmaceuticals 16, 994 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christensen R, Kristensen PK, Bartels EM, Bliddal H & Astrup A Efficacy and safety of the weight-loss drug rimonabant: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 370, 1706–1713 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilding JPH et al. Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. N. Engl. J. Med 384, 989–1002 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wegovy Pen Instructions (Wegovy, 2023); www.wegovy.com/taking-wegovy/how-to-use-the-wegovy-pen.html?gclid=Cj0KCQjw2eilBhCCARIsAG0Pf8tI7X1_NL8ZY2I7KFOkn2YrR24Og2sQBN_rB1jc1lXzCRwnLamdWLIaAu0OEALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klinitzke G, Steinig J, Blüher M, Kersting A & Wagner B Obesity and suicide risk in adults—a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord 145, 277–284 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castaneda D, Popov VB, Wander P & Thompson CC Risk of suicide and self-harm is increased after bariatric surgery—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Surg 29, 322–333 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hung A. et al. Bariatric surgery and suicide risk in patients with obesity. Ann. Surg 278, e760–e765 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheung BMY, Cheung TT & Samaranayake NR Safety of antiobesity drugs. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf 4, 171–181 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.AbdElmageed RM & Mohammed Hussein SM Risk of depression and suicide in diabetic patients. Cureus 14, e20860 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strain T. et al. Impact of follow-up time and analytical approaches to account for reverse causality on the association between physical activity and health outcomes in UK Biobank. Int. J. Epidemiol 49, 162–172 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uzoigwe C, Liang Y, Whitmire S & Paprocki Y Semaglutide once-weekly persistence and adherence versus other GLP-1 RAs in patients with type 2 diabetes in a US real-world setting. Diabetes Ther. 12, 1475–1489 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klonsky ED, Dixon-Luinenburg T & May AM The critical distinction between suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. World Psychiatry 20, 439–441 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Wang Q, Davis PB, Volkow ND & Xu R Increased risk for COVID-19 breakthrough infection in fully vaccinated patients with substance use disorders in the United States between December 2020 and August 2021. World Psychiatry 21, 124–132 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L. et al. Incidence rates and clinical outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection with the Omicron and Delta variants in children younger than 5 years in the US. JAMA Pediatr. 176, 811–813 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L, Davis PB, Kaelber DC, Volkow ND & Xu R Comparison of mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 vaccines on breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infections, hospitalizations, and death during the Delta-predominant period. JAMA 327, 678–680 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L, Davis PB, Kaelber DC & Xu R COVID-19 breakthrough infections and hospitalizations among vaccinated patients with dementia in the United States between December 2020 and August 2021. Alzheimers Dement. 19, 421–432 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang W, Kaelber DC, Xu R & Berger NA Breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infections, hospitalizations, and mortality in vaccinated patients with cancer in the US between December 2020 and November 2021. JAMA Oncol. 8, 1027–1034 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang L, Kaelber DC, Xu R & Berger NA COVID-19 breakthrough infections, hospitalizations and mortality in fully vaccinated patients with hematologic malignancies: a clarion call for maintaining mitigation and ramping-up research. Blood Rev. 54, 100931 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Berger NA & Xu R Risks of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and hospitalization in fully vaccinated patients with multiple myeloma. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2137575 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang L et al. Association of COVID-19 with endocarditis in patients with cocaine or opioid use disorders in the US. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 543–552 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao Z et al. Repurposing ketamine to treat cocaine use disorder: integration of artificial intelligence-based prediction, expert evaluation, clinical corroboration and mechanism of action analyses. Addiction 118, 1307–1319 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olaker VR et al. Association of recent SARS-CoV-2 infection with new-onset alcohol use disorder, January 2020 through January 2022. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2255496 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kendall EK, Olaker VR, Kaelber DC, Xu R & Davis PB Association of SARS-CoV-2 infection with new-onset type 1 diabetes among pediatric patients from 2020 to 2021. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2233014 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan Y, Davis PB, Kaebler DC, Blankfield RP & Xu R Cardiovascular risk of gabapentin and pregabalin in patients with diabetic neuropathy. Cardiovasc. Diabetol 21, 170 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ding P, Pan Y, Wang Q & Xu R Prediction and evaluation of combination pharmacotherapy using natural language processing, machine learning and patient electronic health records. J. Biomed. Inform 133, 104164 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorenflo MP et al. Association of aspirin use with reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease in elderly ischemic stroke patients: a retrospective cohort study. J. Alzheimers Dis 91, 697–704 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang L et al. Cardiac and mortality outcome differences between methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone prescriptions in patients with an opioid use disorder. J. Clin. Psychol 10.1002/jclp.23582 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prescription Medications to Treat Overweight & Obesity (NIDDK, 2023); www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/prescription-medications-treat-overweight-obesity [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schreiber J & Culpepper L Suicidal ideation and behavior in adults. In UpToDate (eds. Roy-Byrne PP & Solomon D) (UpToDate, 2023); https://www.uptodate.com/contents/suicidal-ideation-and-behavior-in-adults [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suicide Prevention. Risk and Protective Factors (CDC, 2023); https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/factors/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 43.John Mann J & Currier D Insights from Neurobiology of Suicidal Behavior (CRC Press, 2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This study used population-level aggregate and de-identified data collected by the TriNetX Platform, which are available from TriNetX (https://trinetx.com/); however, third-party restrictions apply to the availability of these data. The data were used under license for this study with restrictions that do not allow for data to be redistributed or made publicly available. To gain access to the data, a request can be made to TriNetX (join@trinetx.com), but costs might be incurred and a data-sharing agreement would be necessary. Data specific to this study, including diagnosis codes and group characteristics in aggregated format, are included in the paper as tables, figures and supplementary files.