Abstract

Photovoltaic technology has been widely recognized as a means to advance green energy solutions in the sub-Saharan region. In the real-time operation of solar modules, temperature plays a crucial role, making it necessary to evaluate the thermal impact on the performance of the solar devices, especially in high-insolation environments. Hence, this paper investigates the effect of operating temperature on the performance of two types of organometallic halide perovskites (OHP) - formamidinium tin iodide (FASnI3) and methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3). The solar cells were evaluated under a typical Nigerian climate in two different cities before and after graphene passivation. Using a one-dimensional solar capacitance simulation software (SCAPS-1D) program, the simulation results show that graphene passivation improved the conversion efficiency of the solar cells by 0.51 % (FASnI3 device) and 3.11 % (MAPbI3 device). The presence of graphene played a vital role in resisting charge recombination and metal diffusion, which are responsible for the losses in OHP. Thermal analysis revealed that the MAPbI3 device exhibited an increased fill factor (FF) in the temperature range of 20–64 °C, increasing the power conversion efficiency (PCE). This ensured that the MAPbI3 solar cell performed better in the city and the season with harsher thermal conditions (Kaduna, dry season). Thus, MAPbI3 solar cells can thrive excellently in environments where the operating temperature is below 65 °C. Overall, this study shows that the application of OHP devices in sub-Saharan climatic conditions is empirically possible with the right material modification.

Keywords: OHP, SCAPS-1D, Perovskites, Temperature, Graphene, Sub-sahara

1. Introduction

The global shift towards renewable energy as a means of reducing the total reliance on fossil fuels is gaining momentum. Despite the abundance of solar energy, sub-Saharan Africa is known for its harsh climate, which can affect the overall performance of solar cells [1]. Nigeria, located in sub-Saharan Africa, has typical sub-Saharan climatic conditions with seasonal variations. The rainy season brings heavy rainfall, while the dry season is characterized by high seasonal temperatures. The northern region has a Sahel climate with low rainfall and long, dry, and hot periods. The average temperature in this region is over 27 °C. Conversely, the southern equatorial region has a rainforest climate with heavy rainfall and a consistent temperature range between 24 and 27 °C [2].

With unrestricted access to solar energy, this part of the world is ripe for a comprehensive transition to solar power industrialization, thereby providing a practical solution to the unstable power generation and transmission that is hampering economic growth in this region [3]. However, to adopt a solar power-driven economy, the impact of the local climatic conditions on the solar technology used in this environment must be considered. The performance of a photovoltaic device is significantly affected by its operating temperature. Since solar panels are usually installed outdoors, they often operate at temperatures above 27 °C. Studies have shown that elevated temperatures can lead to increased strain and stress on structures, which in turn leads to increased interfacial defects, disorder, and impaired layer interconnectivity [4]. A study by Ogbomo et al. [5] indicates that in a typical Nigerian climate, the cell temperature of a solar module, together with other module performance factors, can reach up to 90 °C, adversely affecting the power output (PO) and power conversion efficiency. In other words, the high operating temperatures can be expected to evaluate the performance and stability of solar modules deployed in these climate conditions.

Organometallic halide perovskites (OHP) have emerged as a promising material for highly efficient and cost-effective solar cells, leading to affordable and optimizable photovoltaic technologies. With these advantages, it seems likely that this technology will soon be widely used, especially in energy-deprived areas. However, the performance and stability of these solar cells are still thermally challenged under conventional operating conditions, which has limited their commercial viability [6]. The photoactive layer of a typical OHP is overly sensitive to the heat generated by the partial conversion of absorbed photon energy, affecting the charge generation, transport, and carrier transport, which ultimately impacts the power output of the solar cell [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]].

The use of structurally stable materials is one way to overcome challenges in the design and optimization of different layers in an OHP. Pb-based as well as Pb-free methyl ammonium (MA) and formamidinium (FA) solar cells continue to be extensively studied as the ideal OHP absorber materials [13]. This is because, with proper material modification and optimization, these types of OHP can potentially overcome their current stability and efficiency limitations in the bid to achieve commercialization [14]. In addition to the absorber layer, the presence of an electron transport layer (ETL) is just as important as that of a hole transport layer (HTL) for efficient charge extraction from the valence band. Therefore, several factors need to be considered when choosing the material for electron and hole transport, such as mobility, functional lifespan, and appropriate band gap energy levels. Depending on the materials used, the OHP can exhibit thermal instability, defects, recombination, and inhibition of charge collection [4]. This has led to various techniques being utilized to enhance the efficiency and durability of OHP. This includes the modifications to the electrodes and perovskite layer surfaces, as well as the incorporation of graphene interlayer into the device layers. Among these approaches, the integration of graphene materials has attracted great interest due to their advantageous mechanical and optoelectronic properties [15]. Consequently, graphene and its derivatives have been utilized to serve as transparent conducting oxide, ETL, HTL, back contact, and interlayer in various OHP interfaces. These graphene-modified OHP are expected to improve in performance and durability under real-time practical conditions [16].

Therefore, in this paper, a thermal analysis of the electrical performance of OHP, before and after interface modification, is performed under typical sub-Saharan climate conditions. The performance of lead-free and lead-based OHP solar cells, namely formamidinium tin triiodide (FASnI3) and methylammonium lead triiodide (MAPbI3), before and after the introduction of a graphene interlayer at different operating temperatures is systematically compared. The FASnI3 solar cell consists of an all-organic charge transport layers (CTL) with a planar n-i-p configuration with phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester (PCBM) and 2,2′,7,7′-Tetrakis[N,N-di(4-methoxyphenyl)amino]-9,9′-spirobifluorene (Spiro-OMeTAD) as ETL and HTL, respectively. In the MAPbI3 solar cell, which has a similar configuration, PCBM is replaced with TiO2. The modification of the two OHP solar cells at the HTL/absorber interlayer was necessary to limit the factors contributing to the defects in the overall performance of the OHP. The graphene interlayer serves as a passivate-charge transport layer (p-CTL), improving charge extraction and reducing recombination [16,17]. The analysis was performed using SCAPS-1D software. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, most thermal analyses of solar cells on SCAPS-1D reported in the literature are based on the assumption of a temperature range. However, in this study, a transient thermal model was used to determine the varying operating temperatures of the solar cells under two different seasonal conditions in Nigeria. The performance of the two OHP under these thermal conditions is compared and discussed. This provides valuable insights and recommendations for their application in a typical sub-Saharan climate setting.

2. Simulation parameters

The following tables (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4) show the parameter values used in the OHP simulation performed with SCAPS-1D, under a 1.5G A.M. sunlight beam. The parameters include the layer thickness (d), electron affinity (χ), band gap energy (Eg), donor impurity concentration (ND), acceptor impurity concentration (NA), permittivity coefficient (Ɛr), hole mobility (μp), electron mobility (μn), electron thermal velocity (Vn), hole thermal velocity (Vp), effective density of conduction band (NC), effective density of valence band (NV), and the defect density (Nt). The front electrode work function is 4.1 eV for the FASnI3 device and 4.4 eV for the MAPbI3 device, while the back electrode work function is 5.1 eV for both solar cells. The simulation was performed under A.M. 1.5G spectrum (1000 W/m2) illumination. Temperature, frequency, and scanning voltage were set to 300 K, 1 × 1016 Hz, and 0–1.30 V, respectively. Without the separation of photo-generated electron-hole pairs (excitons), recombination and energy dissipation occur. Consequently, the overall efficiency of the solar cell is impaired [18]. The modeling defects for SCAPS-1D can be configured as bulk or interface defects. In this modeling, both the bulk defects in each of the solar cell layers and the interface defects between active and buffer layers were used. This helps to create a more realistic device. The interface defects introduced in the simulation are shown in Table 2, Table 4

Table 1.

| Parameters | FTO | ETL | FASnI3 | Graphene | HTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d (μm) | 0.3 | 0.03 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Eg (eV) | 3.5 | 2.1 | 1.41 | 2.48 | 2.91 |

| χ (eV) | 4.1 | 3.9 | 3.52 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| Ɛr | 9.5 | 3.9 | 8.2 | 7.1 | 3.0 |

| NC (cm−3) | 2.20 × 1018 | 2.20 × 1019 | 1.0 × 1018 | 2.2 × 1018 | 2.2 × 1018 |

| NV (cm−3) | 1.80 × 1019 | 2.2 × 1019 | 1.0 × 1018 | 1.0 × 1019 | 1.9 × 1019 |

| Vn (cm s−1) | 1 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 | 5.2 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 |

| Vp (cm s−1) | 1 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 | 5.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 |

| μn (cm2 V−1s−1) | 50 | 1.0 × 10−3 | 22 | 10 | 2.0 × 10−4 |

| μp (cm2 V−1s−1) | 70 | 2.0 × 10−3 | 22 | 10 | 2.0 × 10−4 |

| ND (cm−3) | 1.0 × 1019 | 1.0 × 1018 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NA (cm−3) | 0 | 0 | 7.0 × 1016 | 9.0 × 1021 | 1.0 × 1019 |

| Nt (cm−3) | 1.0 × 1015 | 1.0 × 1015 | 2.0 × 1015 | 1.0 × 1015 | 1.0 × 1015 |

Table 2.

The interface defects parameters for FASnI3 device simulation.

| Parameters | ETL/FASnI3 | FASnI3/Graphene | Graphene/HTL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of defect | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral |

| Total density (cm−3) | 2.30 × 1010 | 1.0 × 109 | 2.30 × 1010 |

| Capture cross-section of electrons (cm2) | 3.20 × 10−18 | 1.0 × 10−19 | 3.20 × 10−18 |

| Capture cross-section of holes (cm2) | 3.20 × 10−18 | 1.0 × 10−19 | 3.20 × 10−18 |

| Reference energy (eV) | 1.30 | 0.6 | 1.30 |

Table 3.

The input parameters for the MAPbI3 device simulation [21].

| Parameters | FTO | ETL | MAPbI3 | Graphene | HTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d (μm) | 0.4 | 0.05 | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.12 |

| Eg (eV) | 3.5 | 3.2 | 1.55 | 1.80 | 3.0 |

| χ (eV) | 4.0 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 3.92 | 2.45 |

| Ɛr | 9.0 | 10.0 | 6.5 | 10 | 3.0 |

| NC (cm−3) | 2.2 × 1018 | 2.20 × 1018 | 2.2 × 1018 | 1.0 × 1021 | 2.25 × 1018 |

| NV (cm−3) | 2.2 × 1018 | 2.2 × 1018 | 2.2 × 1018 | 1.0 × 1021 | 1.8 × 1019 |

| Ve (cm s−1) | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 |

| Vh (cm s−1) | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 |

| μn (cm2 V−1s−1) | 20 | 20 | 2 | 1.0 × 109 | 2.0 × 10−4 |

| μp (cm2 V−1s−1) | 10 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 2.0 × 10−4 |

| ND (cm−3) | 1.0 × 1019 | 1.0 × 1017 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NA (cm−3) | 0 | 0 | 1.0 × 1015 | 9.0 × 1021 | 1.0 × 1018 |

| Nt (cm−3) | 1.0 × 1015 | 1.0 × 1015 | 1.0 × 1014 | 1.0 × 1015 | 1.0 × 1015 |

Table 4.

The interface defects parameters for MAPbI3 device simulation.

| Parameters | ETL/MAPbI3 | MAPbI3/Graphene | Graphene/HTL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of defect | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral |

| Total density (cm−3) | 1.0 × 10−10 | 1.0 × 10−10 | 1.0 × 10−10 |

| Capture cross-section of electrons (cm2) | 1.0 × 10−19 | 1.0 × 10−19 | 1.0 × 10−19 |

| Capture cross-section of holes (cm2) | 1.0 × 10−18 | 1.0 × 10−18 | 1.0 × 10−18 |

| Reference energy (eV) | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

3. Method and models

The solar cells investigated are simulated in the SCAPS-1D software (version 3.3.10). SCAPS-1D is based on the fundamental theory for solving the basic semiconductor equations that characterize gradation defects, recombination, and generation in solar cells [22]. These equations are partial differential equations that are difficult to solve directly using conventional methods. The numerical solutions of these equations are determined with the help of numerical calculations by simulation. SCAPS-1D was chosen to emulate the OHP devices because it has an easy-to-use operating window and, once all parameters are set, operates exactly like the real-life solar cell counterpart. With this method, the energy band gap and other performance parameters of a solar cell, such as the power conversion efficiency (PCE), fill factor (FF), short-circuit current density (Jsc), and open-circuit voltage (Voc), can be easily predicted by solving these three basic semiconductor equations (Equations (1), (2), (3))) [23]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where and are the ionized donor/acceptor doping concentrations, respectively. The hole and electron mobility are denoted as μp and μn respectively. represents the trapped holes, are the free holes, and are the free electrons with respect to the direction of the charges, x. Others are the electron charge, q, permittivity, ε, the electron diffusion coefficient, D, the rate of generation, G, the electric force field, E, and the electrostatic potential, ψ.

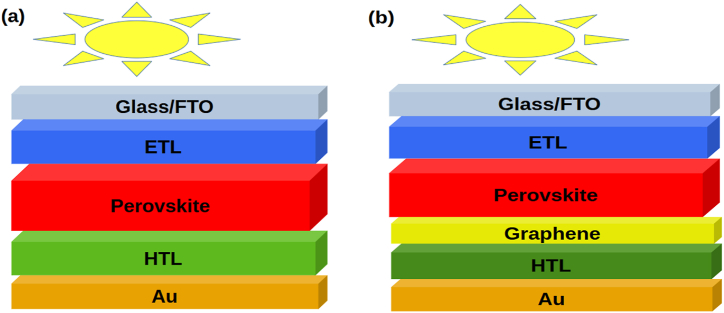

This procedure was used to simulate two solar cells, namely FASnI3 and MAPbI3 solar cells with the design structure presented in previous works [19,21] as shown in Fig. 1a. The FASnI3 solar cell is a planar n-i-p structure comprising a glass + SnO2:F/PC61BM/HC(NH2)2SnI3/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au architecture. A similar configuration was used for the MAPbI3 solar cell, which consists of glass + SnO2:F/TiO2/CH3NH3PbI3/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au. Although Spiro-OMeTAD is commonly used as HTL in OHP devices, the photodoping mechanisms of Spiro-OMeTAD can lead to photo-oxidation and degradation in solar cells [24]. Moreover, ion diffusion at the absorber/spiro-OMeTAD interface at elevated temperatures favors the reduction of hole conductivity of the HTL and the deterioration of the solar cell performance [25]. To address this concern, graphene derivatives, especially graphene oxides (GOs), have been used as both passivation surfaces and charge transport layers in this type of solar cells [[26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]]. These graphene-based materials are well suited for passivation and charge transport applications due to their unique electronic and optical properties, tunable band gap, and high conductivity [16]. In this work, the graphene derivative, graphene oxide (GO) was used as an intermediate passivation interlayer between the absorber and HTL as shown in Fig. 1b.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the OHP showing the n-i-p (planar) structure (a) without a graphene interlayer and (b) with a graphene interlayer.

The thermal analysis is necessary to demonstrate both the durability of the device and the practicality of OHP devices in the real world. The excellent long-term stability observed under different conditions is important information for researchers and engineers working on the further development of solar energy technologies. The operating temperatures of the FASnI3 and MAPbI3 solar cells were estimated using a thermal analysis method as reported previously [19]. In this method, a non-steady state thermal modeling based on an appropriate energy balance was used to determine the thermal response of the solar cells to the varying meteorological conditions of the cities under consideration. The data considered are (a) the meteorological data (ambient temperature, solar irradiance, and wind speed) of two cities (Kaduna and Owerri) in northern and southern Nigeria in the wet and dry seasons, and (b) the parameters (dimension, efficiency, and heat capacity) of FASnI3 and MAPbI3 solar cells. The meteorological data used were accessed from the solar radiation satellite-based database, the Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS) [36]. The hourly operating temperature of the solar cells in the northern (Kaduna) and southern (Owerri) cities of Nigeria is estimated for one day in the 2020 climate season. The results of this analysis are used to compare the effects of the operating temperatures on the electrical yields of the two solar cells. The thermal model for this study has been published by Ozurumba et al. [19].

4. Results and discussion

In this section, the complete investigation and analysis of the reference OHP devices before and after their optimization with graphene was presented. The performance of both devices was also simulated under varying operating temperatures measured in two cities in Nigeria, Kaduna and Owerri. Kaduna, located in the north of Nigeria, has higher temperatures than Owerri, which is located in the south. Additionally, the performance of the devices was measured during the dry and rainy seasons when temperatures and solar radiation vary.

4.1. Comparison between graphene and graphene-free devices

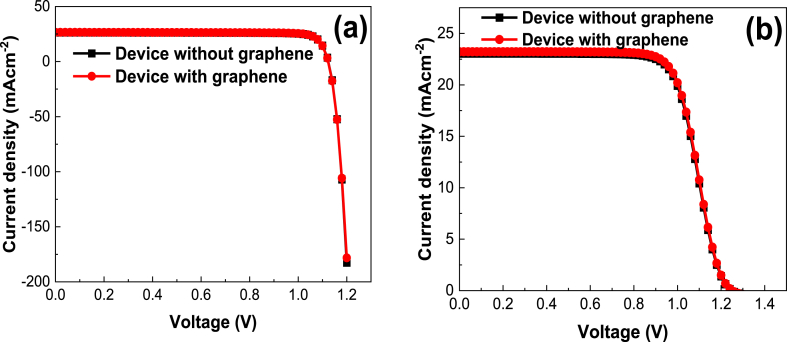

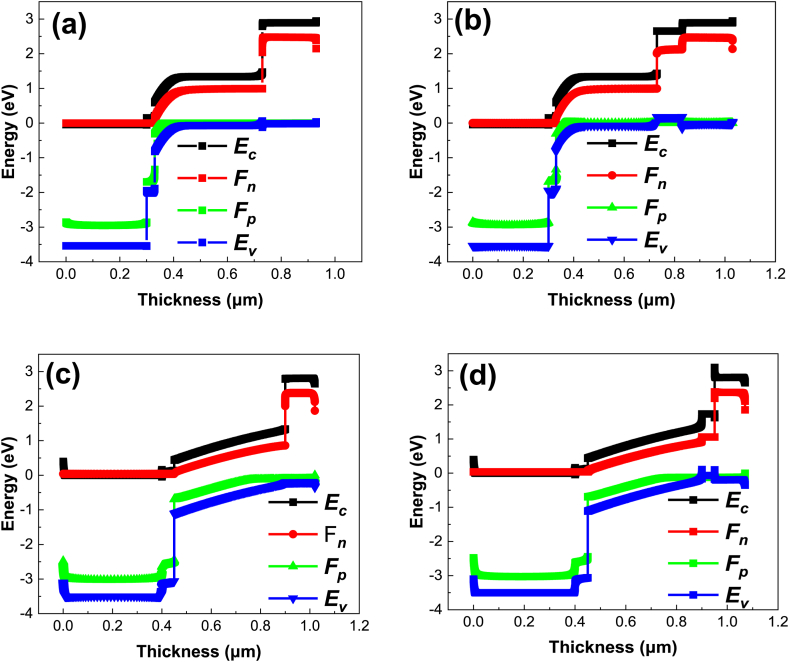

Using the parameters and techniques described above, the impact of graphene passivation on OHP solar cells was investigated. The analyses include the J-V curves, QE curves, and the energy profile of the devices both with and without the graphene layer, as illustrated in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4. Fig. 2a and b shows the response of the FASnI3 and MAPbI3 devices with and without the graphene passivation layer at A.M 1.5 G illumination. In both illustrations, a significant improvement in the performance of the devices with graphene can be seen, resulting in a Jsc of 26.58 mAcm−2, Voc of 1.12 V, FF of 85.91 %, and PCE of 25.65 % for the FASnI3 device, and Jsc of 23.22 mAcm−2, Voc of 1.25 V, FF of 72.01 %, and PCE of 20.91 % for the MAPbI3 device. Compared to the initial graphene-free devices, the FASnI3 solar cell recorded a Jsc, Voc, FF, and PCE of 26.41 mAcm−2, 1.11 V, 85.95 %, and 25.52 % respectively, while the MAPbI3 device recorded a Jsc, Voc, FF, and PCE of 23.03 mAcm−2, 1.23 V, 71.36 %, and 20.28 % respectively. The improved performance of the graphene-embedded devices can be attributed to the effective extraction of holes and the improved device performance resulting from matching the Fermi level of the graphene oxide to those of the two OHP devices. This excellent match enabled a significant fraction of photogenerated charge carriers to diffuse smoothly into the graphene layer. As a result, the probability of the carriers encountering a recombination event during their passage to the graphene was minimal. Consequently, the electron flow advanced towards the graphene upon excitation. The energy band arrangement of the solar cells (shown in Fig. 4a–d) highlights the positions or energy levels of the conduction band (Ec), and valence band (Ev), in relation to the fermi levels (Fp & Fn) at a steady-state. Observation reveals that the absorber/graphene interface exhibits a shift in the conduction band, whereas this shift is absent in the graphene-free device. Consequently, the resistance at the interface is lower than in the graphene-based devices. Furthermore, the conductivity of the graphene-based device is expected to be better than that of the graphene-free device, resulting in a significantly lower resistance.

Fig. 2.

J-V curves of (a) FASnI3 device with and without a graphene interlayer, and (b) MAPbI3 device with and without a graphene interlayer.

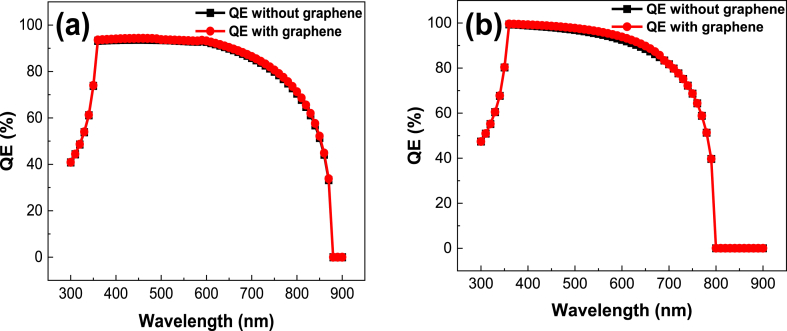

Fig. 3.

QE with respect to wavelength for (a) FASnI3 device with and without a graphene interlayer, and (b) MAPbI3 device with and without a graphene interlayer.

Fig. 4.

Energy profile of (a) FASnI3 device with a graphene interlayer (b) FASnI3 device without a graphene interlayer, (c) MAPbI3 device with a graphene interlayer, and (d) MAPbI3 device without a graphene interlayer.

By analyzing the quantum efficiency (QE) of the solar cell, it is possible to derive the current generated by the solar cell when it is irradiated with photons of specific wavelengths. Fig. 3a and b shows that the conversion efficiency of photons into electrons is optimal in the wavelength range from 300 to 800 nm (880 nm for FASnI3 device) under 1 sun, AM1.5G spectrum. Outside these ranges, light absorption is only of minor relevance for the solar cells investigated. Between 300 nm and 360 nm, the quantum efficiency (QE) rose from 40 % to 95 % (FASnI3 device) and 46 %–100 % (MAPbI3 device), followed by a steady decrease to 0 %. From the observation, the photo-response of the graphene-based device shows a larger QE curve. The response of the solar cells to the incident solar radiation is an indication that photons in the ultraviolet and visible spectrum are absorbed and successfully converted into electrons, which is a critical feature of high-performance OHP devices [23,[37], [38], [39]]. The tables with the comprehensive results, including Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE, for the simulated cells are included in the Supplementary Data.

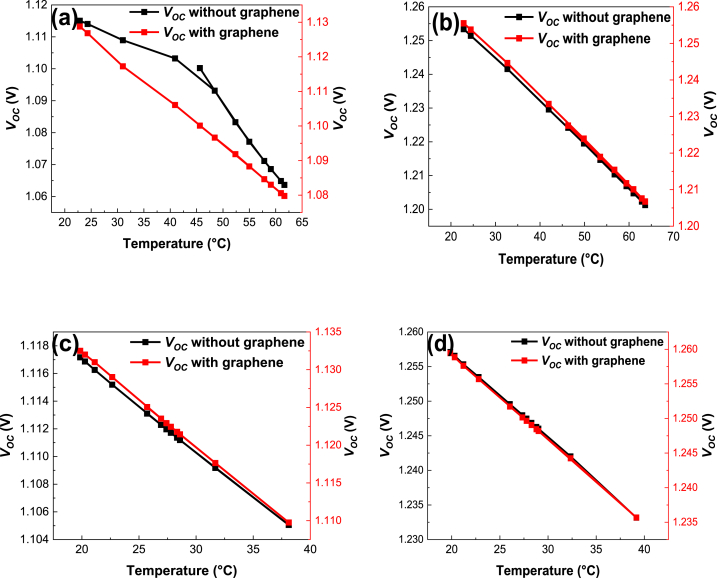

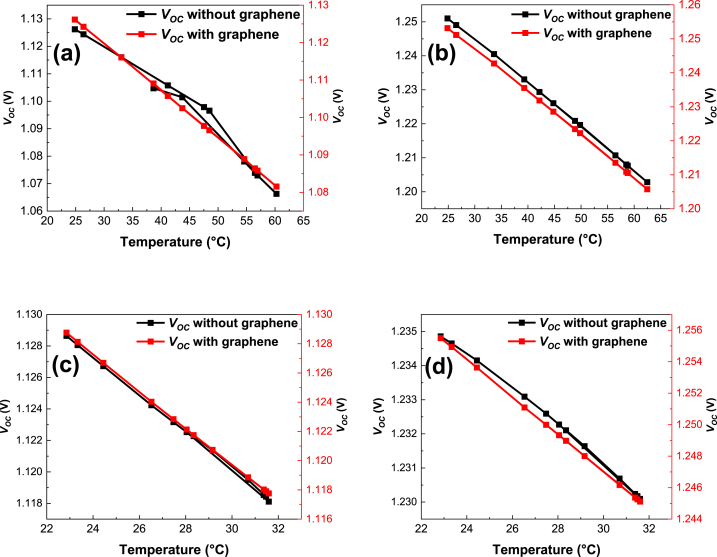

4.2. Effect of operating temperature on Voc

The thermal instability of perovskites cannot be overlooked since continuous exposure to solar radiation during operation leads to thermal stress in OHP [4]. When perovskites come into contact with charge transport materials, injection barriers can limit the Voc of the OHP due to thermionic loss for holes [40]. Fig. 5, Fig. 6a–d show the Voc response of FASnI3 and MAPbI3 solar cells (before and after the introduction of graphene) at different operating temperatures in different seasons. The Voc values of both solar cells maintained a steady decline as the operating temperature increased, regardless of time and location. During the dry season, the OHP devices in Kaduna lost the most Voc, as the operating temperature reached ∼64 °C (see Fig. 5a and b). However, the graphene-passivated devices improved the Voc slightly, reducing charge recombination and facilitating charge collection. The response of Voc to temperature is related to the balance between charge carrier generation and recombination as temperatures vary [41,42]. The additional energy that the photogenerated charges gain by increasing the operating temperature ensures the randomization of the mobility of the electrons. Therefore, they are more likely to recombine with the holes before reaching the electrode contacts. These observations are consistent with the conclusion of Devi et al. [43] that the Voc at high temperatures is influenced by changes in the electron and hole mobility, carrier concentration, the bandgap of a solar cell, and reverse saturation current density [44].

Fig. 5.

Variations in Voc of the OHP devices (with and without graphene) with operating temperature as recorded in Kaduna. (a) FASnI3 device, and (b) MAPbI3 device in the dry season (c) FASnI3 device, and (d) MAPbI3 device in the wet season.

Fig. 6.

Variations in Voc of the OHP devices (with and without graphene) with operating temperature as recorded in Owerri. (a) FASnI3 device, and (b) MAPbI3 device in the dry season (c) FASnI3 device, and (d) MAPbI3 device in the wet season.

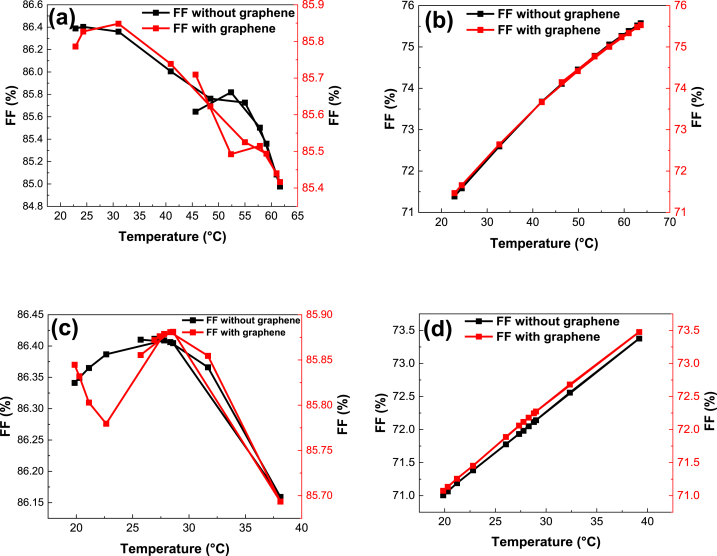

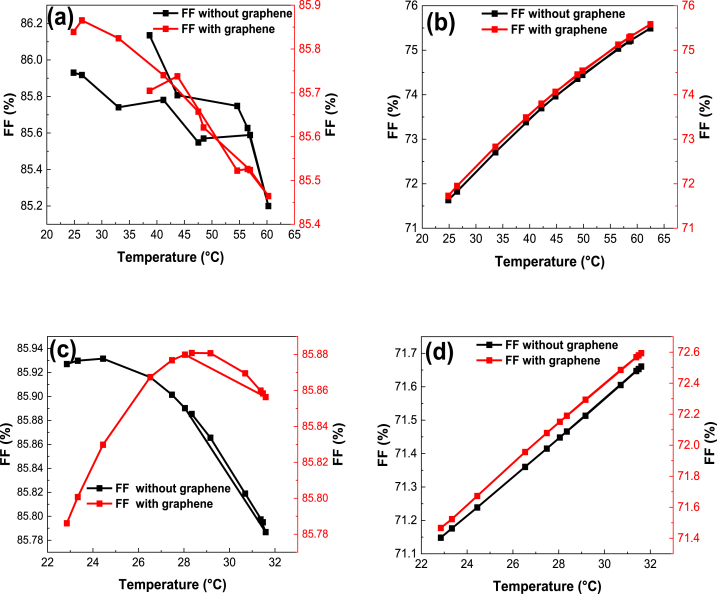

4.3. Effect of operating temperature on FF

The effect of operating temperature on the FF of FASnI3 and MAPbI3 solar cells was observed within the temperature range of 19–64 °C during both the dry and wet seasons. As can be seen in Fig. 7, Fig. 8a–d, the FF of the FASnI3 devices decreased with an increase in temperature and vice versa. Initially, an upward trend in the fill factor was observed at lower temperatures before it began to decrease as the temperature increased (as seen in Fig. 7, Fig. 8a and c). This is attributed to a decrease in Voc and an increase in series resistance as well as the dominance of the recombination process and the extraction barrier at the CTL [40,44]. The introduction of graphene proved to be particularly beneficial for the FASnI3 device as it maintained a high FF in a temperature range of 23–28 °C, as can be seen in Fig. 8c.

Fig. 7.

Variations in FF of the OHP devices (with and without graphene) with operating temperature as recorded in Kaduna. (a) FASnI3 device, and (b) MAPbI3 device in the dry season (c) FASnI3 device, and (d) MAPbI3 device in the wet season.

Fig. 8.

Variations in FF of the OHP devices (with and without graphene) with operating temperature as recorded in Owerri. (a) FASnI3 device, and (b) MAPbI3 device in the dry season (c) FASnI3 device, and (d) MAPbI3 device in the wet season.

In contrast to FASnI3 devices, the progression of FF in MAPbI3 devices appears to follow a similar pattern to temperature, as can be seen in Fig. 7, Fig. 8b and d. The FF increased within the temperature range of 20–64 °C. Studies have shown that the FF of MAPbI3 and FASnI3 solar cells increases at temperatures up to 65 °C before finally decreasing [39,45]. The different trends between MAPbI3 and FASnI3 devices can be attributed to several factors, including bandgap and band alignment of solar cells with their CTLs [44]. Additionally, the integration of a graphene-blocking layer into the HTL has been shown to increase FF by counteracting the formation of diffuse metal-induced shunts and improving heat dissipation across the solar cell [46], which reduces grain boundaries and sites of electron-hole recombination.

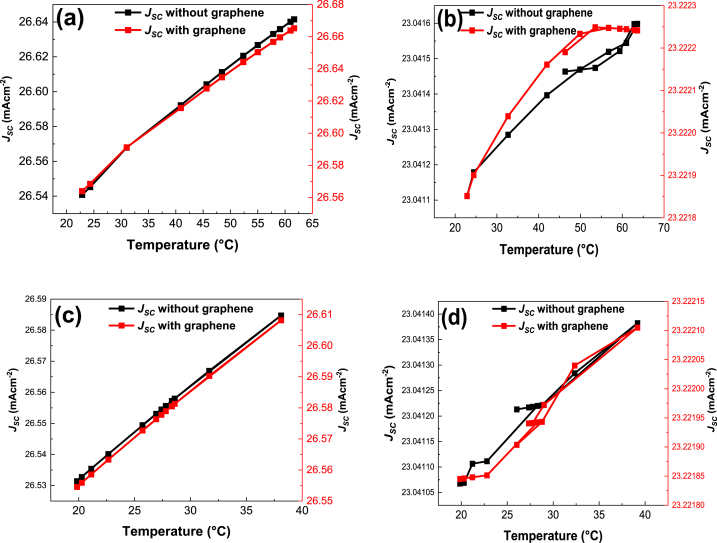

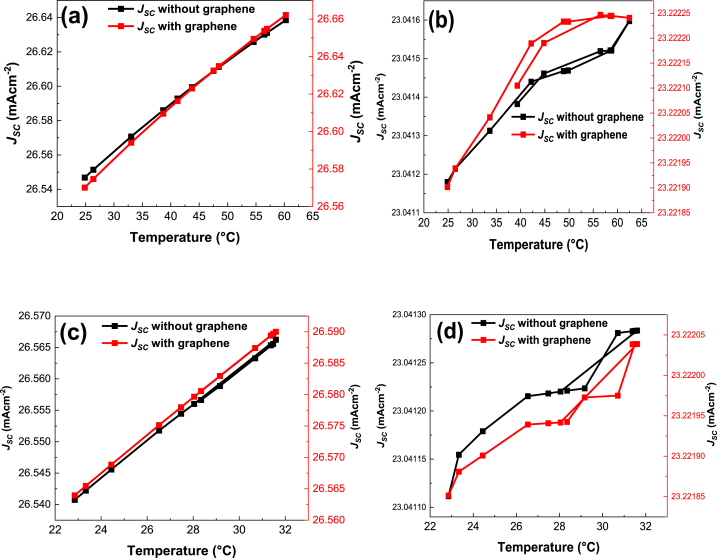

4.4. Effect of operating temperature on Jsc

The relationship between the Jsc and the operating temperature of the OHP (organic-inorganic hybrid perovskite) solar cell has been studied. The results presented in Fig. 9a–d and 10a–d show that there is a progressive linear relationship between the Jsc and the operating temperature, meaning that the Jsc steadily increases as the temperature rises, and vice versa. This is because the Jsc of solar cells is mainly determined by the optical absorption of the photoactive material and the efficiency of the charge extraction [47]. According to Green [42], the increase in Jsc with temperature can be attributed to the decrease in the band gap and increase in the spectral band-to-band absorption coefficient of the solar cell. In other words, an increase in temperature allows for the movement of more electron-hole pairs in the conduction band, resulting in an increase in the efficiency of the generation and collection of photogenerated carriers in the transport layers. The incremental Jsc values of the MAPbI3 solar cells with (without) graphene are relatively low compared to the FASnI3 solar cells (see Fig. 10).

Fig. 9.

Variations in Jsc of the OHP devices (with and without graphene) with operating temperature as recorded in Kaduna. (a) FASnI3 device, and (b) MAPbI3 device in the dry season (c) FASnI3 device, and (d) MAPbI3 device in the wet season.

Fig. 10.

Variations in Jsc of the OHP devices (with and without graphene) with operating temperature as recorded in Owerri. (a) FASnI3 device, and (b) MAPbI3 device in the dry season (c) FASnI3 device, and (d) MAPbI3 device in the wet season.

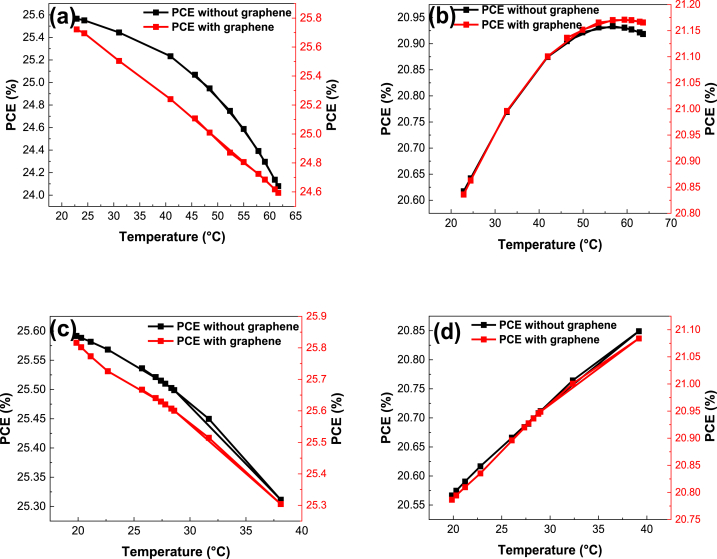

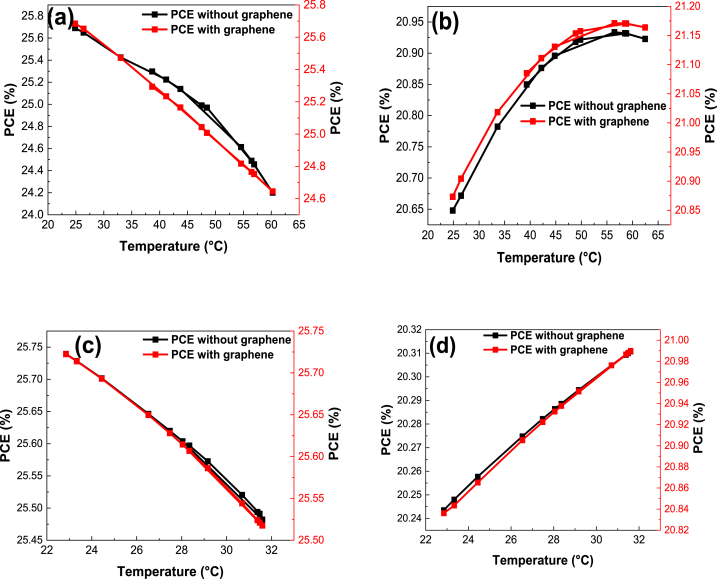

4.5. Effect of operating temperature on PCE

The diagrams in Fig. 11, Fig. 12, show that the efficiency of the FASnI3 decreases exponentially with increasing temperature, while that of the MAPbI3 increases. The thermally induced decrease in the PCE of the FASnI3 solar cell is mainly attributed to the presence of defect states that create an additional pathway for recombination without emitting photons, which increases the overall recombination rate and may decrease the contribution of radiative recombination. In other words, increasing the rate of recombination has a substantial impact on the carrier concentration, mobility of electrons and holes, and the ability of the electron to reach the depletion region [48,49]. Ultimately, the decrease in Voc and FF facilitates the decrease in the PCE of the device (see Fig. 11, Fig. 12a and c).

Fig. 11.

Variations in PCE of the OHP devices (with and without graphene) with operating temperature as recorded in Kaduna. (a) FASnI3 device, and (b) MAPbI3 device in the dry season (c) FASnI3 device, and (d) MAPbI3 device in the wet season.

Fig. 12.

Variations in PCE of the OHP devices (with and without graphene) with operating temperature as recorded in Owerri. (a) FASnI3 device, and (b) MAPbI3 device in the dry season (c) FASnI3 device, and (d) MAPbI3 device in the wet season.

On the contrary, when the operating temperature varies between 20 and 64 °C, the MAPbI3 solar cell shows an increase in efficiency due to the influence of the FF on the solar cell. Since the PCE of OHP devices depends on their Voc and FF [20,47,50,51], the factors that contribute to a favorable response of the fill factor to temperature are observed to be a crucial factor for the PCE of the MAPbI3 solar cell (see Fig. 11, Fig. 12b and d). It was also observed that the incorporation of a graphene layer improved the PCE of the FASnI3 solar cell by 0.51 % and that of the MPbI3 solar cell by 3.11 %. From these results, it can be concluded that a graphene-based interlayer is necessary to stabilize temperature fluctuations in OHP devices and minimize their effects on Voc, Jsc, and FF [[52], [53], [54]]. Therefore, the combination of the interfacial properties of the Spiro-OMeTAD/graphene layer attenuates the temperature-induced interfacial defects and disorder, while improving the low thermal conductivity characteristic of OHP devices [55,56]. These results highlight the significant influence of temperature on the overall electrical performance and efficiency of OHP devices.

5. Conclusion

The thermally induced variations in the performance of FASnI3 and MAPbI3 devices, with or without graphene, show that the operating temperature can affect the ability of OHP to efficiently convert absorbed solar radiation into electrical energy. As high temperatures are common in sub-Saharan Africa, this can affect the performance and stability of solar cells operating in these conditions. The study suggests that optimizing OHP with graphene can result in better performance within a certain range of operating temperatures, leading to a significant increase in efficiency. While FASnI3 devices showed high efficiencies, MAPbI3 solar cells were found to perform better at the measured operating temperatures in the studied cities (20–64 °C). Overall, the application of OHP devices in sub-Saharan regions is shown to be practical. This study, therefore, hopes to have provided the necessary insight into the performance and application of OHP devices in sub-Saharan Africa.

Funding

This article did not receive any funding support.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Anthony C. Ozurumba: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Nnamdi V. Ogueke: Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization. Chinyere A. Madu: Validation, Supervision. Eli Danladi: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Chisom P. Mbachu: Visualization, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation. Abubakar S. Yusuf: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Philibus M. Gyuk: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Ismail Hossain: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Formal analysis.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their gratitude to Professor Marc Burgelman and his team from the Department of Electronics and Information Systems, University of Ghent, Belgium, for the permission to use the SCAPS-1D software package in this study. They are also grateful for the access to the meteorological data of PVGIS©.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29599.

Contributor Information

Anthony C. Ozurumba, Email: ozurumba.anthony@acefuels-futo.org.

Eli Danladi, Email: danladielibako@gmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Ukoba K., Eloka-Eboka A.C., Inambao F.L. ISES Solar World Congress 2017 - IEA SHC International Conference on Solar Heating and Cooling for Buildings and Industry 2017, Proceedings. International Solar Energy Society; 2017. Review of solar energy inclusion in Africa: case study of Nigeria; pp. 962–973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mobolade T.D., Pourvahidi P. Bioclimatic approach for climate classification of Nigeria. Sustainability. 2020;12(10) doi: 10.3390/su12104192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akuru U.B., Onukwube I.E., Okoro O.I., Obe E.S. Towards 100% renewable energy in Nigeria. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017;71:943–953. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.12.123. December. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elangovan N.K., Kannadasan R., Beenarani B.B., Alsharif M.H., Kim M.-K., Hasan Inamul Z. Recent developments in perovskite materials, fabrication techniques, band gap engineering, and the stability of perovskite solar cells. Energy Rep. Jun. 2024;11:1171–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.egyr.2023.12.068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogbomo O.O., Amalu E.H., Ekere N.N., Olagbegi P.O. A review of photovoltaic module technologies for increased performance in tropical climate. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017;75:1225–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.11.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim B.J., Lee S., Jung H.S. Recent progressive efforts in perovskite solar cells toward commercialization. J Mater Chem A Mater. 2018;6(26):12215–12236. doi: 10.1039/C8TA02159G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Browne M.C., Norton B., McCormack S.J. Phase change materials for photovoltaic thermal management. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015;47:762–782. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2015.03.050. March. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattei M., Notton G., Cristofari C., Muselli M., Poggi P. Calculation of the polycrystalline PV module temperature using a simple method of energy balance. Renew. Energy. 2006;31(4):553–567. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2005.03.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang W., Luo Z., Sun R., Guo J., Wang T., Wu Y., Wang W., Guo J., Wu Q., Shi M., Li H., Yang C., Min J. Simultaneous enhanced efficiency and thermal stability in organic solar cells from a polymer acceptor additive. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):1218. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14926-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dupré O., Vaillon R., Green M.A. Physics of the temperature coefficients of solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cell. 2015;140:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.solmat.2015.03.025. September. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wetzelaer G.J.A.H., Scheepers M., Sempere A.M., Momblona C., Ávila J., Bolink H.J. Trap-assisted non-radiative recombination in organic-inorganic perovskite solar cells. Adv. Mater. 2015;27(11):1837–1841. doi: 10.1002/adma.201405372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixit H., Punetha D., Pandey S.K. Improvement in performance of lead free inverted perovskite solar cell by optimization of solar parameters. Optik. 2019;179:969–976. doi: 10.1016/j.ijleo.2018.11.028. February. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu Y., Yan D., Peng J., Duong T., Wan Y., Phang S.P., Shen H., Wu N., Barugkin C., Fu X., Surve S., Grant D., Walter D., White T.P., Catchpolea K.R., Weber K.J. Monolithic perovskite/silicon-homojunction tandem solar cell with over 22% efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017;10(11):2472–2479. doi: 10.1039/c7ee02288c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Attique S., Ali N., Ali S., Khatoon R., Li N., Khesro A., Rauf S., Yang S., Wu H. A potential checkmate to lead: bismuth in organometal halide perovskites, structure, properties, and applications. Adv. Sci. 2020;7(13) doi: 10.1002/advs.201903143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nandi R., Sinha S., Heo J., Kim S.H., Nandi D.K. Recent progress in graphene research for the solar cell application. Carbon Nanostructures. 2019 doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-30207-8_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kafle B.P. Application of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) for stability of perovskite solar cells. Carbon Nanostructures. 2019 doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-30207-8_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seo J., Song T., Rasool S., Park S., Kim J.Y. An overview of lead, tin, and mixed tin–lead-based ABI3 perovskite solar cells. Advanced Energy and Sustainability Research. 2023;4(5) doi: 10.1002/aesr.202200160. John Wiley and Sons Inc, May 01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li S., Liu P., Pan L., Li W., Yang S., Shi Z., Guo H., Xia T., Zhang S., Chen Y. The investigation of inverted p-i-n planar perovskite solar cells based on FASnI3 films. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cell. 2019;199:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.solmat.2019.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozurumba A.C., Ogueke N.V., Madu C.A. Thermal and electrical analyses of organometallic halide solar cells. J. Sol. Energy Eng. Jun. 2024;146(3) doi: 10.1115/1.4063808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhattarai S., Hossain M.K., Pandey R., Madan J., Samajdar D.P., Chowdhury M., Rahman M.F., Ansari M.Z., Albaqami M.D. Enhancement of efficiency in CsSnI3 based perovskite solar cell by numerical modeling of graphene oxide as HTL and ZnMgO as ETL. Heliyon. Jan. 2024;10(1) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danladi E., Egbugha A.C., Obasi R.C., Tasie N.N., Achem C.U., Haruna I.S., Ezeh L.O. Defect and doping concentration study with series and shunt resistance influence on graphene modified perovskite solar cell: a numerical investigation in SCAPS-1D framework. J. Indian Chem. Soc. May 2023;100(5) doi: 10.1016/j.jics.2023.101001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basyoni M.S.S., Salah M.M., Mousa M., Shaker A., Zekry A., Abouelatta M., Alshammari M.T., Al-Dhlan K.A., Gontrand C. On the investigation of interface defects of solar cells: lead-based vs lead-free perovskite. IEEE Access. 2021;9:130221–130232. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3114383. September. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danladi E., Gyuk P.M., Tasie N.N., Egbugha A.C., Behera D., Hossain I., Bagudo I.M., Madugu M.L., Ikyumbur J.T. Impact of hole transport material on perovskite solar cells with different metal electrode: a SCAPS-1D simulation insight. Heliyon. 2023;9(6) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y., Hu J., Wu Y., Qing R., Zhang C., Xu X., Jiang M. Review on methods for improving the thermal and ambient stability of perovskite solar cells. J. Photon. Energy. Dec. 2019;9(4):1. doi: 10.1117/1.jpe.9.040901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jena A.K., Ikegami M., Miyasaka T. Severe morphological deformation of spiro-OMeTAD in (CH3NH3)PbI3 solar cells at high temperature. ACS Energy Lett. 2017;2(8) doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahmoudi T., Rho W.Y., Kohan M., Im Y.H., Mathur S., Hahn Y.B. Suppression of Sn2+/Sn4+ oxidation in tin-based perovskite solar cells with graphene-tin quantum dots composites in active layer. Nano Energy. 2021;90(Dec) doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2021.106495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biccari F., Gabelloni F., Burzi E., Gurioli M., Pescetelli S., Agresti A., Castillo A.E.D.R., Ansaldo A., Kymakis E., Bonaccorso F., Carlo A.D., Vinattieri A. Graphene-based electron transport layers in perovskite solar cells: a step-up for an efficient carrier collection. Adv. Energy Mater. Nov. 2017;7(22) doi: 10.1002/aenm.201701349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahmoudi T., Wang Y., Hahn Y.B. Graphene and its derivatives for solar cells application. Nano Energy. May 01, 2018;47:51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.02.047. Elsevier Ltd. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su H., Wu T., Cui D., Lin X., Luo X., Wang Y., Han L. The application of graphene derivatives in perovskite solar cells. Small Methods. Oct. 01, 2020;4(10) doi: 10.1002/smtd.202000507. John Wiley and Sons Inc. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daraie A., Fattah A. Performance improvement of perovskite heterojunction solar cell using graphene. Opt. Mater. 2020;109(Nov) doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2020.110254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acik M., Darling S.B. Graphene in perovskite solar cells: device design, characterization and implementation. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2016;4(17):6185–6235. doi: 10.1039/c5ta09911k. Royal Society of Chemistry. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun X., Li X., Zeng Y., Meng L. Improving the stability of perovskite by covering graphene on FAPbI3 surface. Int. J. Energy Res. Jun. 2021;45(7):10808–10820. doi: 10.1002/er.6564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gagandeep G., Singh M., Kumar R., Singh V. Graphene as charge transport layers in lead free perovskite solar cell. Mater. Res. Express. Oct. 2019;6(11) doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/ab4b02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y., Leung W.W.F. Introduction of graphene nanofibers into the perovskite layer of perovskite solar cells. ChemSusChem. Sep. 2018;11(17):2921–2929. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201800758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan F., Khan M.T., Rehman S., Al-Sulaiman F. Analysis of electrical parameters of p-i-n perovskites solar cells during passivation via N-doped graphene quantum dots. Surface. Interfac. Jul. 2022;31 doi: 10.1016/J.SURFIN.2022.102066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huld T., Müller R., Gambardella A. A new solar radiation database for estimating PV performance in Europe and Africa. Sol. Energy. Jun. 2012;86(6):1803–1815. doi: 10.1016/j.solener.2012.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ke W., Stoumpos C.C., Zhu M., Mao L., Spanopoulos I., Liu J., Kontsevoi O.Y., Chen M., Sarma D., Zhang Y., Wasielewski M.R., Kanatzidis M.G. Enhanced photovoltaic performance and stability with a new type of hollow 3D perovskite {en}FASnI3. Sci. Adv. 2017;3(8) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1701293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meng X., Lin J., Liu X., He X., Wang Y., Noda T., Wu T., Yang X., Han L. Highly stable and efficient FASnI3-based perovskite solar cells by introducing hydrogen bonding. Adv. Mater. 2019;31(42) doi: 10.1002/adma.201903721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy P., Tiwari S., Khare A. An investigation on the influence of temperature variation on the performance of tin (Sn) based perovskite solar cells using various transport layers and absorber layers. Results in Optics. 2021;4(August) doi: 10.1016/j.rio.2021.100083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang J.M., Luo Y., Bao Q., Li Y.Q., Tang J.X. Recent advances in energetics and stability of metal halide perovskites for optoelectronic applications. Adv. Mater. Interfac. 2019;6(3) doi: 10.1002/admi.201801351. Wiley-VCH Verlag, Feb. 08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dupré O., Vaillon R., Green M.A. first ed. Springer International Publishing; Cham, Switzerland: 2017. Thermal Behavior of Photovoltaic Devices. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Green M.A. General temperature dependence of solar cell performance and implications for device modelling. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 2003;11(5):333–340. doi: 10.1002/pip.496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Devi N., Parrey K.A., Aziz A., Datta S. Numerical simulations of perovskite thin-film solar cells using a CdS hole blocking layer. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B. 2018;36(4):4G105. doi: 10.1116/1.5026163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gholami-Milani A., Ahmadi-Kandjani S., Olyaeefar B., Kermani M.H. Performance analyses of highly efficient inverted all-perovskite bilayer solar cell. Sci. Rep. Dec. 2023;13(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-35504-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benami A., Ouslimane T., Et-taya L., Sohani A. Comparison of the effects of ZnO and TiO2 on the performance of perovskite solar cells via SCAPS-1D software package. J. Nano- Electron. Phys. 2022;14(1):1–5. doi: 10.21272/jnep.14(1).01033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu X., Jiang H., Li J., Ma J., Yang D., Liu Z., Gao F., Liu S. Air and thermally stable perovskite solar cells with CVD-graphene as the blocking layer. Nanoscale. 2017;9(24):8274–8280. doi: 10.1039/c7nr01186e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanchez-Diaz J., Sanchez R.S., Masi S., Krecmarova M., Alvarez A.O., Barea E.M., Rodriguez-Romero J., Chirvony V.S., Sanchez-Royo J.F., Martinez-Pastor J.P., Mora-Sero I. Tin perovskite solar cells with >1,300 h of operational stability in N2 through a synergistic chemical engineering approach a synergistic chemical engineering approach. Joule. 2022;6(4):861–883. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2022.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Danladi E., Kashif M., Daniel T.O., Achem C.U., Alpha M., Gyan M. 7.379 % power conversion efficiency of a numerically simulated solid state dye sensitized solar cell with copper (I) thiocyanate as a hole conductor. East European Journal of Physics. 2022;2022(3):19–31. doi: 10.26565/2312-4334-2022-3-03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Danladi E., Kashif M., Ichoja A., Ayiya B.B. Modeling of a Sn-based HTM-free perovskite solar cell using a one-dimensional solar cell capacitance simulator tool. Trans. Tianjin Univ. 2023;29(1):62–72. doi: 10.1007/s12209-022-00343-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bristow N., Kettle J. Outdoor performance of organic photovoltaics: diurnal analysis, dependence on temperature, irradiance, and degradation. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy. 2015;7(1) doi: 10.1063/1.4906915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qu H., Li X. Temperature dependency of the fill factor in PV modules between 6 and 40 °C. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. Apr. 2019;33(4):1981–1986. doi: 10.1007/s12206-019-0348-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Han G.S., Yoo J.S., Yu F., Duff M.L., Kang B.K., Lee J.K. Highly stable perovskite solar cells in humid and hot environment. J Mater Chem A Mater. 2017;5(28):14733–14740. doi: 10.1039/c7ta03881j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roy P., Tiwari S., Khare A. An investigation on the influence of temperature variation on the performance of tin (Sn) based perovskite solar cells using various transport layers and absorber layers. Results in Optics. 2021;4(August) doi: 10.1016/j.rio.2021.100083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu X., Jiang H., Li J., Ma J., Yang D., Liu Z., Gao F., Liu S. Air and thermally stable perovskite solar cells with CVD-graphene as the blocking layer. Nanoscale. 2017;9(24):8274–8280. doi: 10.1039/c7nr01186e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haeger T., Heiderhoff R., Riedl T. Thermal properties of metal-halide perovskites. J Mater Chem C Mater. 2020;8(41):14289–14311. doi: 10.1039/d0tc03754k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ouslimane T., Et-taya L., Elmaimouni L., Benami A. Impact of absorber layer thickness, defect density, and operating temperature on the performance of MAPbI3 solar cells based on ZnO electron transporting material. Heliyon. Mar. 2021;7(3) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.