Abstract

Board certified behavior analysts are ethically required to first address destructive behavior using reinforcement-based and other less intrusive procedures before considering the use of restrictive or punishment-based procedures (ethics standard 2.15; Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2020). However, the inclusion of punishment in reinforcement-based treatments may be warranted in some cases of severe forms of destructive behavior that poses risk of harm to the client or others. In these cases, behavior analysts are required to base the selection of treatment components on empirical assessment results (ethics standard 2.14; Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2020). One such preintervention assessment is the stimulus avoidance assessment (SAA), which allows clinicians to identify a procedure that is likely to function as a punisher. Since the inception of this assessment approach, no studies have conducted a systematic literature review of published SAA cases. These data may be pertinent to examine the efficacy, generality, and best practices for the SAA. The current review sought to address this gap by synthesizing findings from peer-reviewed published literature including (1) the phenomenology and epidemiology of the population partaking in the SAA; (2) procedural variations of the SAA across studies (e.g., number of series, session length); (3) important quality indicators of the SAA (i.e., procedural integrity, social validity); and (4) how the SAA informed final treatment efficacy. We discuss findings in the context of the clinical use of the SAA and suggest several avenues for future research.

Keywords: Stimulus avoidance assessment, Punishment, Destructive behavior, Punisher assessment, Quality indicators

Severe destructive behavior such as aggression, self-injurious behavior (SIB), property destruction, elopement, or pica are often exhibited by individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (Cooper et al., 2009; Crocker et al., 2006; Dekker et al., 2002; Emerson et al., 2001). The negative effects of severe destructive behavior, such as bruising, bleeding, blindness, tissue damage, and even death (Anderson et al., 2012; Kuhn et al., 2008; Rooker et al., 2020; Woods et al., 2001) warrant effective treatment of these behaviors. Consistent with our ethics code (ethics standard 2.15; Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB), 2020), behavior analysts prioritize the use of reinforcement-based procedures when treating severe destructive behavior. These treatments are often highly efficacious at reducing destructive behavior and increasing socially appropriate behavior (Brosnan & Healy, 2011; Campbell, 2003; Heyvaert et al., 2014; Horner et al., 2002).

However, reinforcement-based procedures alone are sometimes insufficient at reducing severe destructive behavior and additional treatment options are needed. In some cases, the inclusion of punishment (i.e., an environmental change contingent on a response that decreases that response over time, defined broadly; Cooper et al., 2019; Michael, 1993) to an existing reinforcement-based treatment to reduce severe destructive behavior to acceptable levels may be necessary (Lerman & Vorndran, 2002). There are a few situations described by the BACB’s Ethics Code in which incorporating a punishment procedure within a reinforcement-based treatment may be warranted to reduce severe destructive behavior after scrupulous consideration. First, the inclusion of punishment may be considered when reinforcement-only and less intrusive procedures are insufficient at producing clinically meaningful reductions in destructive behavior (ethics standard 2.15; BACB, 2020). For example, Kurtz et al. (2003) conducted a retrospective consecutive controlled case series (CCCS) on treatment of automatically maintained SIB and found a third of cases (10 of 30) required the inclusion of punishment to reduce destructive behavior by at least 80% after reinforcement-only procedures were insufficient. Other studies have found similar outcomes (e.g., Falcomata et al., 2004; Watkins & Rapp, 2014). In these situations, clinicians may need to carefully consider incorporating punishment if destructive behavior is so dangerous that the risk associated with punishment procedures is lower compared to the risk of harm if the client’s destructive behavior is left untreated (ethics standard 2.15; BACB, 2020). For example, Doughty et al. (2005) implemented punishment in the form of a 20-s baskethold (i.e., the researcher held the client’s arms folded across their chest) to decrease severe destructive behavior for a 21-month-old child whose SIB resulted in tissue damage (i.e., bleeding) when reinforcement-based procedures alone were insufficient. The addition of punishment to the existing reinforcement-based treatment decreased rates of destructive behavior across all phases when compared to reinforcement-based procedures alone.

Given the inclusion of a punishment procedure is sometimes warranted, careful consideration of how behavior analysts develop treatments that include punishment is necessary to ensure it is done in an ethical manner. Although the BACB ethics code of conduct provides some guidance regarding the situations in which punishment or restrictive procedures could be included, it does not provide specific guidance on how clinicians should select punishment components to be added to the treatment. Behavior analysts are ethically bound to ensure their clients receive the least restrictive, yet effective treatment (Van Houten et al., 1988) and that the development of this treatment is informed by an assessment (ethics standard 2.14; BACB, 2020). In the case of punishment, a preintervention assessment may entail briefly assessing several different procedures with the purpose of identifying one that is likely to function as a punisher during a subsequent treatment analysis. These punisher assessments are akin to preference assessments conducted to identify potential reinforcers for treatment (e.g., Pace et al., 1985). By conducting a punisher assessment, behavior analysts may be able to avoid prolonged and unnecessary exposure to ineffective punishers and reduce time to effective treatment (Fisher et al., 1994a).

To date, only two punisher assessments have been disseminated in our peer-reviewed published literature. The most recent assessment, described by Verriden and Roscoe (2019), assessed a total of four or five procedures with individuals for whom reinforcement-based procedures alone (e.g., noncontingent reinforcement, differential reinforcement of alternative behavior) were insufficient in reducing target behavior. During the assessment, contingent on each occurrence of target behavior (i.e., object mouthing, motor stereotypy, or hair manipulation), researchers implemented one of the procedures (e.g., demands, response cost, timeout) within the individual’s existing reinforcement-based treatment. Researchers measured target behavior, appropriate behavior (e.g., engagement with toys), and emotional responding (i.e., crying, whining, screaming, self-injury, aggression, and physical resistance or attempts to escape the procedure) that occurred during each procedure. Results of their assessment indicated almost all procedures were effective as a punisher for target behavior across all participants, and the procedure that was most effective differed across individuals. Despite these promising results, no studies have replicated these procedures, particularly with more severe forms of destructive behavior for which punishment procedures should be considered after a cost-benefit analysis (e.g., SIB, pica; Brown et al., 2023; Hagopian et al., 1998; Hanley et al., 2005). Given these current limitations, the generality of this assessment remains largely unknown (Brown et al., 2021).

Another published punisher assessment is the stimulus avoidance assessment (SAA; Fisher et al., 1994a, 1994b). This assessment consists of noncontingently implementing procedures (e.g., baskethold, timeout, demands) one at a time on a fixed-time (FT) 30-s schedule and measuring negative vocalizations (e.g., crying), avoidant movements (e.g., moving body away from the therapist), and positive vocalizations (e.g., laughing). Procedures are implemented during the SAA noncontingently to avoid a mixed scheduled of punishment and reinforcement of severe destructive behavior, inadvertent reinforcement of severe destructive behavior, and minimal applications of the potentially aversive stimuli (for further discussion, see Fisher et al., 1994b). An avoidance index is calculated for each procedure by adding negative vocalizations and avoidant movements then subtracting positive vocalizations. Procedures with high avoidance indices are suggested to be more likely to function as a punisher when implemented contingent on destructive behavior. For example, the seminal SAA studies conducted by Fisher et al. included five participants diagnosed with intellectual and developmental disabilities with histories of insufficient reductions in destructive behavior using reinforcement-based procedures and medications. All participants engaged in behavior topographies (e.g., SIB, pica, climbing) that resulted in self-injury. Researchers conducted an SAA with each participant, and then compared procedures with low, moderate, and high avoidance indices during a subsequent assessment to determine which procedure(s) functioned as a punisher. The assessment indicated the procedure with the highest avoidance index was most effective at reducing destructive behavior relative to the low- and moderate-index procedures for all five participants, providing evidence for the predictive validity of the SAA to identify potential punishers that could be included in reinforcement-based treatments.

Although punisher assessments have been published in the literature for several decades, a systematic literature review on these assessments is surprisingly absent. Systematic literature reviews are scientifically valuable in that they quantify and summarize results of published studies which allows for the refinement of best-practice recommendations (e.g., Hagopian et al., 2011; Hurd et al., 2023; Kranak & Brown, 2023) and provide clear directions for future research (e.g., Beavers et al., 2013; Hanley et al., 2003; Melanson & Fahmie, 2023). Given the value of systematic literature reviews, it is perhaps unsurprising they have been employed to analyze the outcomes of many behavior-analytic assessments such as functional analysis (e.g., Beavers et al., 2013; Hanley et al., 2003; Hurd et al., 2023; Jessel et al., 2020; Melanson & Fahmie, 2023), preference assessments (e.g., Hagopian et al., 2004; Kang et al., 2013), and competing stimulus assessments (e.g., Haddock & Hagopian, 2020). It is surprising that no systematic literature reviews have ever been conducted on punisher assessments. This type of synthesis of the literature is particularly relevant for the SAA given more than one study has been published using this assessment methodology. Filling this gap could help identify the overall efficacy and generality of the SAA, and add to a growing body of literature to inform the identification and selection of punishment procedures in clinical practice.

The purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic literature review of published SAA cases between 1994 and 2022. We sought to synthesize the findings in these cases, including (1) the phenomenology and epidemiology (e.g., diagnoses, ages, topographies of behavior, function of behavior) of the population exposed to the SAA; (2) variations in procedural details of the SAA across studies (e.g., session duration, number of series); (3) important quality indicators (i.e., social validity, procedural integrity) of the SAA; and (4) how the SAA informed the final treatment.

Method

Literature Review and Article Inclusion

We searched PsycINFO and ProQuest for empirical studies published between 1994 and 2022 using the key phrases: “stimulus avoidance assessment” or “empirically derived consequences.” In addition, we searched Google Scholar for articles with these phrases and reviewed the reference section of each included article to ensure identification of all relevant articles. To be included in our search, the study had to target destructive behavior (i.e., aggression, SIB, disruptive behavior, elopement, inappropriate sexual behavior, injury-risk behavior, property destruction, pica, or rumination) and conduct an SAA using a FT schedule for procedure implementation.

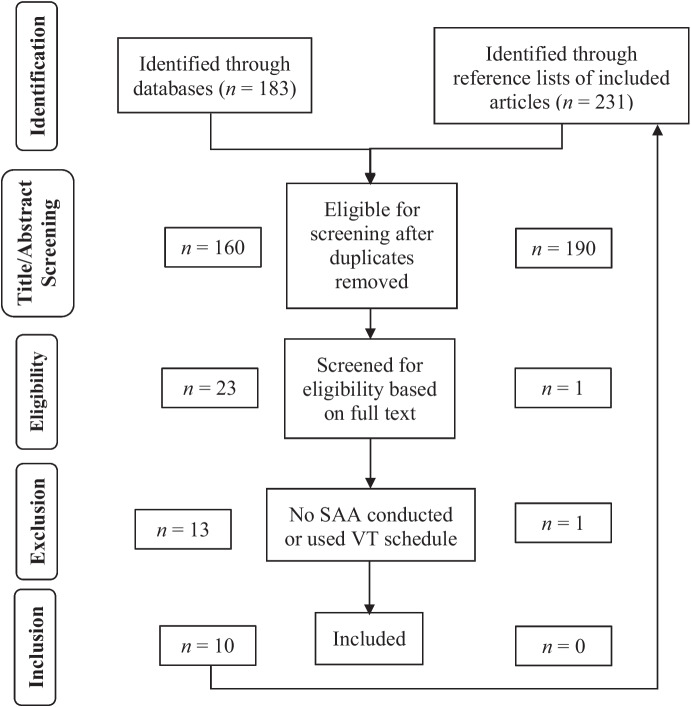

Our initial search criteria returned 183 articles (165 [Google Scholar], 9 [PsycINFO], 9 [ProQuest]). We removed duplicate articles and screened the title and abstract of 160 articles for eligibility. After excluding articles based on title and abstract that did not meet inclusion criteria, we reviewed the full text of 23 articles. We excluded 12 of these studies because they did not conduct an SAA and 1 study because they implemented procedures on a variable-time (VT) schedule during the SAA. We considered the use of an FT schedule necessary to be included in our sample as the seminal articles (Fisher et al., 1994a, 1994b) used an FT interval between each implementation of a procedure coupled with the sound of a buzzer to minimize superstitious conditioning. In addition, the use of a VT schedule during the SAA has not been empirically examined in comparison to an FT schedule, and changing one of the foundational parameters of the assessment could have unknown effects on its predictive validity. Thus, we identified 10 articles meeting our inclusion criteria. We reviewed the reference lists of these 10 articles, which resulted in researchers using the same screening process detailed above for 231 references. This search resulted in no additional articles identified for possible inclusion. Figure 1 is a flow chart depicting the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guideline process used to conduct this review (PRISMA; Liberati et al., 2009).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of Studies

Interobserver Agreement

The third author independently reviewed 57.4% of all returned articles to assess interobserver agreement of article inclusion. We calculated exact agreement by summing the number of articles for which authors agreed on inclusion or exclusion and divided by the number of articles assessed (n = 238) then multiplied by 100 to obtain a percentage. Agreement of article inclusion was 100%.

The third author independently coded dependent variables for 34.4% of cases included in the review. We calculated exact agreement by summing the number of variables for which the authors agreed and divided this number by the sum of opportunities for agreements and disagreements for each case. We multiplied the resulting quotient by 100. The grand mean agreement coefficient across variables was 95.7% (range: 89.6%–100%). In cases of disagreement, the data collectors reviewed the data and used consensus scoring.

Response Measurement and Data Analysis

We only coded variables explicitly stated in the article. For example, if a published article did not report participant’s sex (e.g., only provided a pseudonym), we coded this variable as not reported.

Phenomenology and Epidemiology

We collected demographic data on the participant’s (1) age; (2) sex; (3) developmental and/or behavioral diagnoses; (4) topographies of destructive behavior; (5) function(s) of destructive behavior as reported by the authors; (6) behavioral medications prescribed for behavioral/mood stability; (7) contextual information specifying why an SAA was conducted; and (8) other treatments conducted prior to the SAA. We categorized contextual information that indicated why an SAA was conducted as severity of destructive behavior if researchers reported that an SAA was initiated because destructive behavior posed risk of harm and/or previous treatments were ineffective if researchers reported using at least one treatment that did not produce sufficient reductions in destructive behavior.

Stimulus Avoidance Assessment Procedures and Outcomes

Data collectors scored the following procedural and outcome variables of the SAA: (1) type and number of procedures assessed (see Appendix Table 6 for operational definitions of each procedure); (2) total number of series; (3) session duration; (4) session termination criteria; (5) avoidance index formula used; and (6) average and individual avoidance index per procedure. We scored avoidance indices for each procedure by recording reported raw values or via an extraction tool (i.e., WebPlotDigitizer; Rohatgi, 2022) if data were only displayed visually.

Stimulus Avoidance Assessment Quality Indicators

For quality indicators, we scored procedural integrity and social validity data. Consistent with the seminal SAA articles (Fisher et al., 1994a, 1994b), we scored procedural integrity as frequency of escape from the procedure (e.g., the participant moving in a manner in which the therapist could no longer hold both arms in a baskethold procedure). We scored that social validity measures were collected if researchers reported using a formal data collection method (e.g., Likert scale) from at least one caregiver prior to conducting the SAA. We did not score reports of informal methods (e.g., interviews) or those that occurred after the SAA.

Final Treatment

Data collectors scored if researchers reported including an SAA procedure in the final treatment for each case. Of the cases researchers reported the use of an SAA procedure, we also scored the type of procedure used. Data collectors scored how the SAA informed the selection of a punishment procedure by categorizing cases as included (1) the procedure with the highest avoidance index during the SAA; (2) an SAA procedure that did not have the highest avoidance index but still had a positive index; or (3) a procedure with a zero or negative avoidance index. Finally, we recorded the efficacy of the final treatment with an SAA-informed punishment procedure as reported by researchers.

Results

Phenomenology and Epidemiology

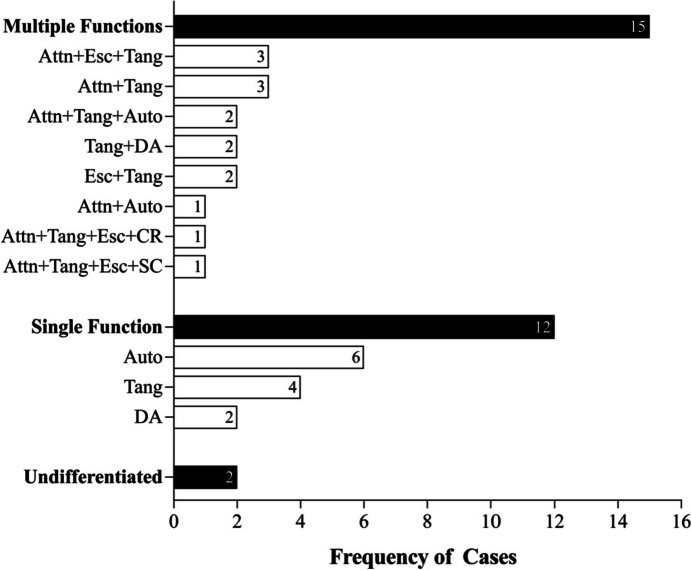

There were 32 cases that conducted an SAA across 10 articles. Table 1 displays demographic information. The majority of participants for whom sex was reported (59.3%; n = 19/32) were male (78.9%; n = 15/19) with a median age of 6.5 years (range: 2–28). Diagnoses were reported for all cases, and the most commonly reported were intellectual delay (43.7%; n = 14/32) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD; 21.8%; n = 7/32). Topographies of destructive behavior were reported for all cases, and the most common were SIB (78.1%; n = 25/32), aggression (40.6%; n = 13/32), and property destruction (18.7%; n = 6/32). Figure 2 displays reported function of destructive behavior, which was available for 29 of 32 cases (90.6%). Destructive behavior was most commonly reported to be maintained by multiple isolated sources of social reinforcement (37.5%; n = 12/32), followed by automatic reinforcement (18.7%; n = 6/32), access to tangibles (12.5%; n = 4/32), and social reinforcement plus automatic reinforcement (9.3%; n = 3/32). In only a third of all cases (31.8%; n = 7/32) did researchers report medication management.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| First Author, Year | Participant | Age | Sex | Diagnosis | Topography | Function | Medication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fisher, 1994a | Hatti | 9 | F | ID | SIB, Agg, Dis, DA | Undiff | None |

| Milt | 5 | M | ID | SIB, Pica, Dis | Auto | None | |

| Fisher, 1994b | Ava | 3 | NS | ID | Pica | - | None |

| Jeff | 5 | NS | ID, GDD | Pica, Dis | - | None | |

| Tom | 3 | NS | ID, GDD | Pica, IT | - | None | |

| Toole et al., 2004 | Mitchell | 16 | M | ASD w/ ID | SIB | Auto | None |

| Nancy | 12 | F | ID | SIB | Auto | None | |

| DeRosa et al., 2016 | Darnell | 18 | M | ASD | Rumination | Auto | None |

| Manente & LaRue, 2017 | Tony | 28 | M | ASD w/ ID | SIB | Auto | None |

| Mitteer et al., 2015 | Callie | 6 | F | ASD | Pica, Dis | Auto | None |

| Kurtz et al., 2003 | Case 1 | 3 | NS | ID | SIB | Attn, Tang | None |

| Case 2 | 3 | NS | GDD | SIB | Tang | None | |

| Case 4 | 2 | NS | GDD | SIB | Undiff | None | |

| Case 5 | 2 | NS | None | SIB | Attn, Tang | None | |

| Case 7 | 2 | NS | GDD | SIB | Tang, Div Attn | None | |

| Case 11 | 4 | NS | ID | SIB | Div Attn, Undiff | None | |

| Case 19 | 4 | NS | ID | SIB | Tang | None | |

| Case 21 | 2 | NS | ID | SIB | Tang, Div Attn | None | |

| Case 26 | 2 | NS | ID | SIB | Attn, Tang | None | |

| Case 29 | 2 | NS | ID | SIB | Attn, Esc Tang, CR | None | |

| Kurtz et al., 2015 | Andrew | 6 | M | ODD, ID | SIB, Agg, Dis | Esc, Tang | None |

| Ben | 7 | M | ID | SIB, Agg, Dis, NC | SC, Esc, Tang, Attn | None | |

| Simmons et al., 2021 | Norbert | 13 | M | ASD w/ ID | Agg, PD | Att, Tang, Auto | None |

| Jordan | 8 | M | ASD w/ ID | Agg, SIB, PD | Tang | None | |

| Brown et al., 2021 | 1 | 9 | F | UDICCD, SMD | Agg, SIB | Div Attn | Poly |

| 2 | 7 | M | ASD, SMD | Agg, SIB, PD, Flop | Attn, Esc, Tang | None | |

| 3 | 13 | M | UDICCD | Agg, Flop | Attn, Tang, Auto | Poly | |

| 4 | 14 | M | DMDD, SMD | Agg, SIB, PD | Attn, Esc, Tang | Poly | |

| 5 | 7 | M | ASD, UDICCD, P, SMD | Agg, SIB, Flop, ISB | Attn, Auto | Poly | |

| 6 | 8 | M | ASD, UDICCD, SMD | Agg, SIB, Flop | Tang | Poly | |

| 7 | 9 | M | ASD, UDICCD, SMD | Agg, SIB, PD | Esc, Tang | Single | |

| 8 | 10 | M | ASD, UD, P, SMD | Agg, SIB, PD | Attn, Esc, Tang | Single |

F = female; M = male; ID = Intellectual Delay; GDD = Global Developmental Delay; ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder; ODD = Oppositional Defiant Disorder; UD = Unspecified Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorder; SMD = Stereotypic Movement Disorder; DMDD = Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder; P = Pica; SIB = self-injurious behavior; Agg = aggression; Dis = disruptive behavior; DA = dangerous acts; IT = inappropriate touching; NC = noncompliance; PD = property destruction; Flop = flopping; ISB = inappropriate sexual behavior; Undiff = undifferentiated; Auto = automatic reinforcement; - = functional analysis not conducted; Attn = attention; Tang = tangible; Div Attn = diverted attention; CR = caregiver return; SC = social control; Esc = escape; Poly = two or more prescribed medications; Single = one prescribed medication

a Fisher et al. (1994a)

b Fisher et al. (1994b)

Fig. 2.

Distribution of Function across Cases. Note. Attn = attention; Esc = escape; Tang = tangible; Auto = automatic reinforcement; Div Attn = diverted attention; CR = caregiver return; SC = social control. Function information was not reported for three cases

Contextual information specified an SAA was conducted after previously attempted treatments did not produce significant reductions in destructive behavior for all cases (100%; n = 32/32). In addition, about half of these cases (53.1%; n = 17/32) also specified an SAA was initiated due to the severity of destructive behavior. Table 2 lists previously attempted treatments as reported by researchers for cases in which they were listed or described (62.5%; n = 20/32). Of the cases that listed or described previously attempted treatments, clinicians conducted an average of 3.0 (range: 1–5) different treatments per case prior to considering adding an empirically identified punisher via the SAA. Previous treatments included medication, protective equipment (e.g., foam helmet), antecedent-based preventative treatments (e.g., noncontingent reinforcement), reinforcement-based treatments (e.g., differential reinforcement of other behavior), and punishers (e.g., time-out) selected without the SAA.

Table 2.

Treatments Attempted Prior to SAA as Reported by Researchers

| First Author, Year | Participant | Treatments |

|---|---|---|

| Fisher, 1994a | Hatti | Medication, DRA+EXT |

| Milt | Foam helmet, posey vest | |

| Fisher, 1994b | Ava | DRO, training alternative behavior, response blocking, redirection to appropriate activity, TO |

| Jeff | Constant supervision, frequent handwashing, praise for appropriate toy play, verbal reprimands | |

| Tom | FCT, DRC, DRO, ignoring | |

| DeRosa et al., 2016 | Darnell | NCR |

| Manente & LaRue, 2017 | Tony | NCR, contingent and noncontingent helmet, competing items, competing activities, DRI, DRO, DRL, DRA, response blocking |

| Mitteer et al., 2015 | Callie | DRA |

| Kurtz et al., 2015 | Andrew | FCT+EXT |

| Ben | FCT+EXT | |

| Simmons et al., 2021 | Norbert | Multiple schedule |

| Jordan | Multiple schedule | |

| Brown et al., 2021 | 1 | FCT, mixed schedule, multiple schedule, competing activities |

| 2 | FCT, multiple schedule, competing activities, DRC | |

| 3 | FCT, multiple schedule, competing activities, NCR | |

| 4 | FCT, multiple schedule, NCR | |

| 5 | NCR, competing items, response blocking | |

| 6 | FCT, multiple schedule, response blocking, DRO | |

| 7 | FCT, competing activities, NCR, response blocking token economy | |

| 8 | FCT, multiple schedule, chained schedule, NCR |

DRA = differential reinforcement of alternative behavior; EXT = extinction; DRO = differential reinforcement of other behavior; TO = time-out; FCT = functional communication training; DRC = differential reinforcement of compliance; NCR = noncontingent reinforcement; DRI = differential reinforcement of incompatible behavior; DRL = differential reinforcement of low-rate responding

Stimulus Avoidance Assessment Procedures and Outcomes

Table 3 displays SAA procedural information. Of the cases that reported session length (n = 18), the most common session length was 10 min (61.1%; n = 11/18) and 20 min (27.7%; n = 5/18), followed by 5 min (5.5%; n = 1/18) and 11 min (5.5%; n = 1/18). Session termination criteria were specified by researchers for only 5 of 32 cases (15.6%). Of the cases that reported number of series conducted (n = 17), researchers most commonly conducted one (41.1%; n = 7/17) or two (35.2%; n = 6/17) series, followed by three (17.6%; n = 3/17) and five (5.8%; n = 1/17) series. The schedule at which a procedure was implemented during each session was available for 7 of 32 cases (21.8%), all of which used an FT 30-s schedule (100%). The duration that researchers implemented each procedure for was available for 10 of 32 cases (31.2%). Of these cases, researchers most commonly implemented the procedure for 30 s at a time (50.0%; n = 5/10), with remaining cases implementing the procedure for 15–180 s (50.0%; n = 5/10). The avoidance index formula was reported for over half of cases (56.2%; n = 18/32). Of these cases, most used the formula described by Fisher et al.’s (1994a) seminal study (83.3%; n = 15/18; avoidance movements plus negative vocalizations minus positive vocalizations). The remaining three cases (16.6%) either used avoidance movements plus negative vocalizations (11.1%; n = 2/18) or avoidance movements only (5.5%; n = 1/18).

Table 3.

Availability of SAA Procedural Details

| Study | # of Cases | Session Length (Min) | ITI | Procedure Duration | AI Formula Consistent with Fisher et al. (1994a) | # of Series Conducted | AI Available |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fisher et al. (1994a) | 2 | 20 | NS | 15, 30, 60, 120, 180 s2 | Yes | 1 | Yes |

| Fisher et al. (1994b) | 3 | 20 | FT 30 s | 15, 30, 60, 120, 180 s | No3 | 1 | Yes |

| Toole et al. (2004) | 2 | 10 | FT 30 s | 30 s | Yes | 1 | Yes |

| DeRosa et al. (2016) | 1 | NS | NS | 30 s | NS | NS | No |

| Manente & LaRue (2017) | 1 | NS | NS | NS | No | NS | No |

| Mitteer et al. (2015) | 1 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | No |

| Kurtz et al. (2003) | 10 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | No |

| Kurtz et al. (2015) | 2 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | No |

| Simmons et al. (2021) | 2 | 10 | FT 30 s | 30 s | Yes | 2 or 3 | Yes |

| Brown et al. (2021) | 8 | 101 | NS | NS | Yes | 2, 3, or 5 | Yes |

NS = not specified; FT = fixed-time; AI = avoidance indices

1Brown et al. (2021) implemented 5-min sessions for one participant

2Fisher et al. (1994a) reported using this schedule for all procedures except water mist, which was implemented for 1 s

3Fisher et al. (1994b) reported using a different formula for each participant, one of which was consistent with Fisher et al. (1994a)

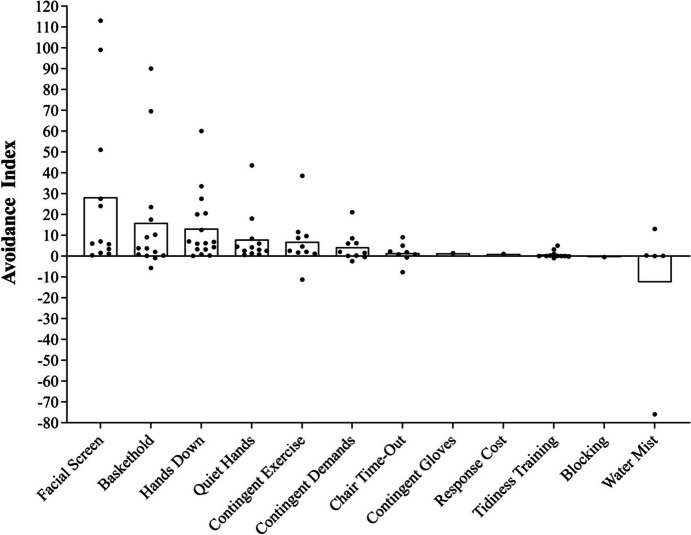

Researchers reported procedures assessed in the SAA in just over half of cases (59.3%; n = 19/32). Table 4 shows type and frequency of procedures assessed. Clinicians assessed an average of 6.1 procedures (range: 4–9). The most commonly assessed procedures were hands down (53.1%; n = 17/32), baskethold (50.0%; n = 16/32), and facial screen (50.0%; n = 16/32). Avoidance indices were only provided for 17 of 32 cases (53.1%). Figure 3 depicts the average avoidance index across cases (bar graph) and individual avoidance index (closed circles) for each implementation of the procedure. Procedures with the highest avoidance indices were facial screen (M = 28.2; range: 0.3–113.0), baskethold (M = 15.9; range: -5.7–90.0), and hands down (M = 13.2; range: 0.1–60.0), although there was marked variability in the avoidance index across cases.

Table 4.

Procedures Assessed during SAA

| Procedure | # of Cases Assessed | % of Cases Assessed |

|---|---|---|

| Hands Down | 17 | 53.1 |

| Baskethold | 16 | 50.0 |

| Facial Screen | 16 | 50.0 |

| Quiet Hands | 15 | 46.8 |

| Tidiness Training | 12 | 37.5 |

| Contingent Exercise | 11 | 34.3 |

| Contingent Demands | 10 | 31.2 |

| Chair Time-Out | 9 | 28.1 |

| Water Mist | 5 | 15.6 |

| Response Cost | 1 | 3.1 |

| Blocking | 1 | 3.1 |

| Contingent Gloves | 1 | 3.1 |

| Verbal Reprimand | 1 | 3.1 |

| Air Puff | 1 | 3.1 |

| Nonpreferred Taste | 1 | 3.1 |

| Nonpreferred Smell | 1 | 3.1 |

| Vibration | 1 | 3.1 |

| Ice Pack | 1 | 3.1 |

Fig. 3.

Avoidance Index across Procedures. Note. Average avoidance index (bar graph) across cases for each procedure and the individual avoidance index (closed circle). A high avoidance index indicates a more aversive procedure whereas a low avoidance index indicates a less aversive procedure

Stimulus Avoidance Assessment Quality Indicators

Just under one-third of cases reported collecting escape from procedure as a procedural integrity measure (28.1%; n = 9/32); however, no cases reported these data. About the same number of cases (31.2%; n = 10/32) reported formally collecting social validity ratings from caregivers prior to conducting the SAA using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 7 with 1 being the least favorable and 7 being the most favorable. All of these cases were from recently published studies (Brown et al., 2021; Simmons et al., 2021). In eight of these cases, researchers reported clinicians did not assess procedures with a social validity rating of less than 4; however, social validity values were not reported. In the remaining two cases, average social validity was 5.8 across all procedures. Of the cases that did not formally assess social validity prior to conducting the SAA (n = 22), a handful of these cases (36.3%; n = 8/22) reported informally consulting with caregivers prior to incorporating a procedure into treatment.

Final Treatment

Table 5 displays final treatment information. Out of 32 cases, 22 (68.7%) reported they included an SAA-informed punishment procedure in the individual’s final treatment. The remaining 10 cases (31.2%) did not provide any information regarding the final treatment. Researchers specified which SAA procedure was included in the final treatment in 12 of the 22 cases (54.5%) with final treatment information. Of these cases, the most commonly used procedure was facial screen (58.3%; n = 7/12). Avoidance indices of the selected SAA procedure were available in 7 of the 22 cases (31.8%). Of these cases, a handful (71.4%; n = 5/7) included the SAA procedure with the highest avoidance index and a few (28.5%; n = 2) included an SAA procedure that did not have the highest avoidance index but was still positive. Efficacy of the final treatment with an SAA-informed punishment procedure was reported in 18 of the 22 cases (81.8%) with final treatment information. Of these cases, all reported a reduction in destructive behavior by 74.5% or greater from baseline when the SAA-informed punisher was implemented.

Table 5.

Final Treatment Outcomes

| Study | Participant ID | Procedure Selected for Treatment | Avoidance Index and Rank of Selected Procedure | Final Treatment Efficacy Reported by Authors (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fisher et al. (1994a) | Hatti | Contingent Demands | 8.5 (1/8) | 90.6 |

| Milt | Facial Screen | 5.7 (1/4) | 91.2 | |

| Fisher et al. (1994b) | Ava | Facial Screen | 3.4 (1/9) | NS |

| Jeff | Facial Screen | 24.0 (1/7) | NS | |

| Tom | Facial Screen | 113.0 (1/6) | NS | |

| Toole et al. (2004) | Mitchell | NS | NS | NS |

| Nancy | NS | NS | NS | |

| DeRosa et al. (2016) | Darnell | Facial Screen | NS | 96.5 |

| Manente & LaRue (2017) | Tony | Reprimand | NS | 85.7 |

| Mitteer et al. (2015) | Callie | Facial Screen | NS | NS |

| Kurtz et al. (2003) | Case 1 | NS | NS |

100 (SIB) 99.7 (Combined) |

| Case 2 | NS | NS |

94.0 (SIB) 29.6 (Combined) |

|

| Case 4 | NS | NS |

100 (SIB) 95.9 (Combined) |

|

| Case 5 | NS | NS |

77.0 (SIB) 76.8 (Combined) |

|

| Case 7 | NS | NS |

100 (SIB) 89.4 (Combined) |

|

| Case 11 | NS | NS |

100 (SIB) 94.0 (Combined) |

|

| Case 19 | NS | NS |

89.0 (SIB) 62.8 (Combined) |

|

| Case 21 | NS | NS |

74.5 (SIB) 82.2 (Combined) |

|

| Case 26 | NS | NS |

100 (SIB) 99.7 (Combined) |

|

| Case 29 | NS | NS | 89.7 (SIB) | |

| Kurtz et al. (2015) | Andrew | Baskethold | NS | 93.3; 98.3 |

| Ben | Facial Screen | NS | 94.9 | |

| Simmons et al. (2021) | Norbert | Baskethold | 2.0 (3/4) | 86.4 |

| Jordan | Baskethold | 3.7 (2/4) | 90.2 | |

| Brown et al. (2021) | Case 1 | NS | NS | NS |

| Case 2 | NS | NS | NS | |

| Case 3 | NS | NS | NS | |

| Case 4 | NS | NS | NS | |

| Case 5 | NS | NS | NS | |

| Case 6 | NS | NS | NS | |

| Case 7 | NS | NS | NS | |

| Case 8 | NS | NS | NS |

NS = not specified; Combined = combined destructive behavior

Discussion

The current study is the first to conduct a literature review on the SAA, the most commonly published punisher assessment. We summarized the results of 32 published cases of the SAA across 10 studies and found that SAA procedures with high avoidance indices appeared to inform efficacious final treatments. In addition, we discovered several findings that aligned with previous research outcomes, as well as some differences such as a greater prevalence of destructive behavior maintained by multiple sources of reinforcement correlated with the implementation of the SAA. Before discussing each of our findings in more depth below, it is important to emphasize that the use of restrictive and punishment procedures cannot be the first approach when treating severe destructive behavior as stipulated in the Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (ethics standard 2.15; BACB, 2020). Behavior analysts should first attempt reinforcement-based and less intrusive procedures and only scrupulously consider the inclusion of punishment to an existing reinforcement-based treatment in situations described by ethics standard 2.15. In addition, clinicians should consider obtaining medical consultation and clearance from a client’s medical provider to rule out alternative medical explanations for destructive behavior, and to ensure that none of the potential punishers assessed in the SAA are medically contraindicated prior to initiating an SAA.

In the current study, similar to previous research, we found the SAA was conducted almost exclusively with children and adolescents diagnosed with an intellectual and/or developmental disorder (Lerman & Vorndran, 2002; Pokorski & Barton, 2021). We found that information regarding medication management was only reported for about one third of cases. Future research may investigate best practice regarding medication use and punishment (e.g., if medication should be attempted as a treatment option prior to incorporating punishment, and if certain classes of medications facilitate quicker fading of punishment). Regarding function of destructive behavior, we found behavior was most frequently reported to be maintained by multiple sources of social reinforcement, which is a deviation from other published studies that have primarily found punishment is most frequently used in cases with automatically maintained destructive behavior (Lydon et al., 2015; Rooker et al., 2018). A few exceptions are Brown et al. (2021, 2023), who also found a higher prevalence of multiply maintained destructive behavior in their retrospective CCCS of the SAA. Brown et al. (2021, 2023) found that destructive behavior was maintained by multiple sources of social reinforcement in 35.2% and 53.8% of cases, respectively. Higher prevalence of multiple sources of social reinforcement in these two reviews could be due to sampling given both studies originated from the same site with five overlapping cases, three of which had destructive behavior maintained by multiple sources of social reinforcement. However, even without the Brown et al. (2021) cases in our sample, the prevalence of destructive behavior maintained by multiple sources of social reinforcement was still 33.3% (8 of 24 cases), which reflects a 4.2% difference. Another potential explanation for a higher prevalence of multiple sources of social reinforcement related to punisher use is that during treatment, extinction of destructive behavior maintained by one reinforcement contingency might result in the reinforcement of destructive behavior maintained by another reinforcement contingency. For example, in a case with destructive behavior maintained by both reinforcement contingencies of attention and escape, withholding attention for destructive behavior without continuing to issue demands could reinforce escape-maintained destructive behavior. Further research should examine the prevalence of function of destructive behavior for cases that warrant inclusion of a punishment procedure to determine the prevalence of this outcome in a wider sample.

In addition to examining the phenomenology and epidemiology of the population undergoing an SAA, we compared procedural variations of the SAA across studies. The seminal Fisher et al. (1994a, 1994b) studies established the predictive validity of the SAA using one series of 20-min sessions per procedure1 with an FT 30-s implementation schedule, which was selected for practicality reasons. It should be noted that we found several studies since the publication of the Fisher et al. studies that modified the SAA, such as session duration and number of series. Based on the current review, it is unclear why clinicians modified the session length or series in some SAA cases. This seems a particularly relevant question given the lack of published research to support that modifying session duration or number of series improves the predictive validity of the SAA (i.e., the likelihood of identifying a potential punisher). To our knowledge, no studies have explicitly examined how variations in session duration or number of series conducted influence the predictive validity of the SAA. Although Brown et al. (2021) examined cases that conducted multiple series of the SAA to examine the reliability of SAA outcomes across multiple series, they did not examine the predictive validity of one versus multiple series of the SAA. This line of research is critical to demonstrate that any potential benefits from these modifications outweigh their potential costs (e.g., greater time in assessment with noncontingent application of potential punishers). It is possible clinicians have adapted procedural aspects of the SAA without evaluation due to variables not adequately captured in the published literature (e.g., the noncontingent application of potentially aversive stimuli prompting them to conduct shorter sessions, concerns of within-subject variability prompting them to conduct more than one series). This finding of moving outside established boundary conditions set by the seminal SAA predictive validity studies is likely also a by-product of the challenge researchers might face in ethically conducting predictive validity studies on punisher preassessments. Notwithstanding, progressing toward unknown procedural boundaries in clinical practice without empirical evidence could result in costly outcomes such as unnecessary exposure to potentially aversive stimuli and delays to effective treatment if the assessment does not yield meaningful results for the client and stakeholders.

We found that researchers specified session termination criteria for only a handful of cases. All cases for which session termination criteria were specified were from the seminal studies conducted by Fisher et al. (1994a, 1994b). For example, Fisher et al. (1994a) monitored participants for “excessive or unexpected emotional responses during or following any of the procedures (e.g., crying for more than 5 min following the session)” and consulted with the supervising psychologist to terminate a session (p. 138). Fisher et al. noted this did not occur with either of their participants in their study. It is possible that researchers put session termination criteria in place for more cases, but it was not reported in the published studies. However, given the SAA applies potentially aversive stimuli noncontingently, it would be imperative that researchers and clinicians develop and describe individualized session termination criteria to ensure participant safety during the SAA.

It is worth briefly noting we observed a high degree of variability in the avoidance index across subjects. All three of the procedures we found to have the highest avoidance index on average (i.e., facial screen, baskethold, and hands down) had near-zero minimum values when examining the range. At least two other studies have found similar across-subject variability in the avoidance index, as well as a high amount of within-subject variability (Brown et al., 2021, 2023). Overall, these data suggest the avoidance index may be a highly individualized measure sensitive to changing establishing operations or other environmental events. Future research might consider further examining the variability of avoidance indices within- and across-subjects.

We found that complete procedural details for the SAA were often absent across studies. This may, in part, be due to the fact that many studies that met our inclusion criteria reported conducting an SAA, but the primary purpose of the study was not to examine this assessment (e.g., Kurtz et al. (2003) summarizing the assessment and treatment of 30 SIB cases). Researchers have recently begun highlighting the importance of reporting assessment information (e.g., Hurd et al. (2023) for functional analysis of noncompliance; Rajaraman & Hanley (2021) for functional analysis of mand compliance). As such, we encourage future researchers to be diligent in reporting complete procedural details for punisher assessments to aid in the synthesis of the literature, which can determine areas for future research.

Perhaps of particular concern, we found formal social validity measures were largely absent in published cases with formal social validity measures collected in more recently published studies (Brown et al., 2021; Simmons et al., 2021). It is possible more researchers collected these data but did not report them. Of the cases that reported social validity outcomes, caregivers provided relatively high ratings across procedures, regardless of varying degrees of perceived procedural restrictiveness (e.g., response cost relative to facial screen). Further, if all procedures were reported with similar social validity ratings, one may question whether this method of assessing social validity is conducive to useful ratings given the lack of differentiation between procedures despite disparate forms of punishment procedures. It is possible caregivers attended to other procedural features, such as a history of failed use or response effort (see Simmons et al., 2021) when rating procedures. We urge future punisher preassessment research to make these data available to allow examination of how social validity affects the development of final treatments that incorporate punishment. In addition, given single measures of social validity may not provide a comprehensive measure of acceptability (Finn & Sladeczek, 2001), we encourage future research to examine caregiver and client preference for punishment procedures throughout the service relationship using a wider range of methods. For example, Simmons et al. (2021) collected procedural integrity at two different points in service delivery: before and after caregiver implementation of the SAA. Results showed social validity ratings decreased for most procedures between pre- and post-implementation of the SAA, highlighting the importance of collecting multiple social validity measures. Of equal importance is assessing the social acceptability of the procedure for the client; however, this can prove challenging for punishment procedures. Although not an SAA, Verriden and Roscoe’s (2019) punisher preassessment used the absence of emotional responding to assess client preference of different procedures. This approach is challenging to adopt for the SAA, which uses emotional responding (i.e., negative vocalizations) as an indicator of potential punishment or lack thereof (i.e., positive vocalizations). More research is needed to understand to what extent emotional responding is correlated with punisher efficacy (Brown et al., 2021). To further this line of research, researchers across sites may form collaborative alliances to conduct retrospective CCCS as suggested by Brown et al. (2023) or explore these questions in translational contexts (e.g., point loss during a computer game).

Of the studies that reported the efficacy of the final reinforcement-based treatment with the SAA-informed punisher, researchers reported reductions in destructive behavior by 74.5% or greater from baseline. It should be noted that behavior analysts should fade out punishment procedures as soon as possible while maintaining meaningful reductions in destructive behavior. Given this, it may be possible that behavior analysts incorporated punishment into the final treatment following the SAA but later faded it out during maintenance or generalization phases that were not published. Results should be interpreted in light of this. These results are consistent with Brown et al. (2023), who conducted a retrospective CCCS of 17 cases that conducted an SAA and examined the relationship between the SAA and final treatment efficacy. They found in most cases, clinicians incorporated an SAA procedure with a positive avoidance index into the final treatment and almost all of these cases resulted in reductions of destructive behavior by 70% or greater relative to baseline. The majority of cases in the current review reported selecting a procedure with a positive avoidance index, with only two selecting the procedure with the highest positive avoidance index. This finding also replicates Brown et al. who found only 23.5% of cases incorporated the SAA procedure with the highest positive avoidance index. Brown et al. conducted a correlational analysis between SAA avoidance index and efficacy of the SAA-informed final treatment and found a moderate, positive relationship between these variables. Said differently, the higher the avoidance index of a given procedure, the more effective the final treatment was at reducing destructive behavior. Although our sample did not contain enough data to replicate the correlational analysis conducted by Brown et al., the current literature suggests it may not be critical for the selected procedure to have the highest avoidance index, but rather a positive avoidance index (Fisher et al., 1994b; Toole et al., 2004). This finding may be pertinent as clinicians balance the importance of identifying an effective punisher to reduce severe forms of destructive behavior, without unnecessarily evoking or eliciting negative emotional responding (see Verriden & Roscoe, 2019, for discussion).

For cases in which researchers did not select the SAA procedure with the highest avoidance index for final treatment, it is unclear how these decisions were made. Simmons et al., (2021) was the only study to report clinician decision making for selecting an SAA procedure with a positive avoidance index, that did not have the highest index. For one case (Norbert), clinicians reported the procedure with the highest avoidance index was not ranked highest for social validity and that Norbert was still able to engage in the target behavior during implementation of the procedure. For the second case (Jordan), the procedure with the highest avoidance index was ranked lowest for social validity, so researchers selected another positive-index SAA procedure that was ranked highest for social validity and could be implemented with high levels of procedural integrity. It should be noted that procedural integrity is likely to be highly variable based on individual parameters (e.g., physical stature of participant or therapist, topography of behaviors), but the absence of these data in the majority of published studies precludes any potential identification of boundary conditions or mediating variables. Overall, these results demonstrate that clinicians may be attending to quality indicators, such as social validity and procedural integrity, in addition to avoidance indices. However, the lack of reported rationale in most cases raises concerns related to training clinicians to conduct and interpret SAAs. A clinician who is not extensively trained to conduct SAAs and interpret its results according to the most recent literature may be inclined to choose the procedure with the highest avoidance index, similar to choosing the stimulus selected and consumed most often during a preference assessment (Fisher et al., 1992). This could be problematic because clinicians should be taking into account other variables such as social validity and procedural integrity. In leaving the decision-making process up to the acumen of the therapist, it is difficult to develop recommendations for training clinicians to conduct punisher assessments when they are warranted. As such, we encourage future studies to report the rationale for selecting punisher procedures as well as important quality indicator data (e.g., social validity, procedural integrity).

Perhaps of the utmost importance to discuss regarding the SAA is how it fits within today’s landscape of assessment and treatment of severe destructive behavior, which is shifting from an expert model to one that places the behavior analyst within a team of professionals and stakeholders that work with the client to continuously conduct social validity analyses and cost-benefit analyses for all treatment components. That is, certain punishment procedures used extremely infrequently in the past, now lack social acceptability even under the most severe cases of destructive behavior (e.g., contingent electric skin shock; Association for Behavior Analysis International, 2022). The noncontingent application of potentially aversive stimuli and some of the procedures (e.g., water mist) that have been assessed in SAAs likely raise concerns of intrusiveness and acceptability. As it currently stands, our field lacks alternatives to the SAA for empirically identifying potential punishers outside of the assessment described by Verriden and Roscoe (2019). Given the inclusion of punishment is warranted in some cases for which only reinforcement-only procedures are insufficient at reducing severe destructive behavior (ethics standard 2.15; BACB, 2020), alternatives to the SAA and specific guidance on how to safely and ethically incorporate punishment into a reinforcement-based treatment is needed. Until alternatives are empirically developed and validated, we think it is important to pose several considerations regarding the SAA. First, the SAA is likely a necessary assessment to identify potential punishers for only a small population of clients with whom clinicians first exhaust reinforcement-based treatments with insufficient reductions in severe destructive behavior that poses risk of harm to the client and others. The small number of published cases identified for the current review provides some support for this consideration. Second, the frequency of punishers implemented will likely be lower near the end of the treatment analysis. For example, in the final treatment phase of Mitteer et al. (2015), the punisher was not implemented during the last three sessions due to the complete absence of destructive behavior. Similar results of zero or near-zero rates of destructive behavior at the end of treatment were observed for several other cases in the current sample (e.g., Migan-Gandonou & Leon, 2020; Simmons et al., 2021; Toole et al., 2004). Third, identification of additional stimuli to assess in the SAA is critical due to the intrusiveness and likelihood of low social acceptability of some procedures that have been included (e.g., water mist, which has not been assessed since 1994 with the exception of one case). We strongly recommend clinicians work closely with stakeholders to identify socially and ecologically valid procedures to assess in the SAA, especially for populations who have limited skills required to self-advocate.

The present study adds to a growing number of studies that seeks to fill a gap in the literature related to punisher preassessments. Although we found the SAA largely informed efficacious treatments for individuals with developmental and intellectual disabilities, many questions remain as to how procedural modifications and quality indicators may affect these outcomes. At this time of limited published research, we do not feel that it is premature to provide practice guidelines for conducting SAAs (e.g., ideal procedures to assess). However, clinicians should follow ethical guidelines including: (1) ensuring reinforcement-based treatments are attempted before assessing the inclusion of punishment (ethics standards 2.14 & 2.15; BACB, 2020); (2) only including punishers in cases in which severe destructive behavior poses an immediate risk of harm (ethics standard 2.15); (3) collaborating with qualified medical professionals to rule out biological causes of destructive behavior prior to conducting an SAA (ethics standards 2.10 & 2.12); and (4) operating within their scope of competence consistent with their training (ethics standard 1.05). When considering the implementation of an SAA, clinicians should conduct thorough and diligent risk-benefit analyses that carefully consider the noncontingent application of potentially aversive stimuli in the SAA with the potential costs to the client or others if severe destructive behavior is left untreated with regards to meaningful reductions in the target behavior. Clinicians should develop session termination criteria that prioritize client safety prior to conducting an SAA and fade punishment procedures as soon as possible. Future research should continue to safely and ethically examine the efficacy and generality of the SAA and other punisher assessments in a way that maintains client safety and solely focuses on producing the best possible outcomes for clients.

Appendix 1

Table 6.

Operational Definitions of Stimulus Avoidance Procedures

| Procedure | Definition |

|---|---|

| Hands Down | The therapist held the participant’s hands to their sides. |

| Baskethold | The therapist held the participant above their wrists with their arms folded across their chest. |

| Facial Screen | The therapist stood behind the participant and placed one arm around the participant’s arms while placing the other hand over their eyes. |

| Quiet Hands | The therapist used the minimum amount of physical prompting necessary to guide the participant’s hands on to their lap for 5 s at a time and repeated this procedure with 5 s between each implementation. |

| Chair Time-Out | The therapist instructed the participant to go to time-out. If the participant did not comply with the instruction within 5 s, the therapist used the minimum amount of physical prompting necessary to guide the participant to sit in the designated time-out chair that was positioned in a corner. |

| Contingent Demands | The therapist stood behind the participant and said: “Touch your head, touch your shoulders, touch your waist, touch your shoulders, touch you” head," while using the minimum amount of physical prompting necessary to guide the participant to complete demands. |

| Contingent Exercise | The therapist stood behind the participant and said: “Touch you” toes," while using the minimum amount of physical prompting necessary to guide the participant to complete the exercise. |

| Tidiness Training | Toys and crumpled paper were strewn around the room, and the therapist instructed the participant to put the paper in the garbage and the toys in a toy crate. If the participant did not begin the task after 5 s, the therapist used the minimum amount of physical prompting necessary to guide the participant to complete the task. |

| Reprimands | The therapist issued verbal disapproving statement (e.g., “There is no hitting your head”) in an authoritative tone above normal conversational level. |

| Water Mist | Therapist activated a plant mister from approximately 6 in away from the participant’s nose and pointed away from the participant’s eyes. |

Authors did not provide response definitions for response cost, blocking, contingent gloves, air puff, non-preferred taste, non-preferred smell, vibration, or ice pack in the reviewed studies

Data Availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no original datasets were generated during the current study.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Fisher et al. (1994a) conducted 10-min sessions for water mist.

The authors thank Juliana Aguilar for her comments on an earlier version of the article.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

* Asterisk indicates studies analyzed in the current review

- Anderson C, Law JK, Daniels A, Rice C, Mandell DS, Hagopian L, Law PA. Occurrence and family impact of elopement in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):870–877. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association for Behavior Analysis International. (2022). Position statement on the use of CESS. https://www.abainternational.org/about-us/policies-and-positions/position-statement-on-the-use-of-cess-2022.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beavers GA, Iwata BA, Lerman DC. Thirty years of research on the functional analysis of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46(1):1–21. doi: 10.1002/jaba.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020). Ethics code for behavior analysts. https://bacb.com/wp-content/ethics-code-for-behavior-analysts/

- Brosnan J, Healy O. A review of behavioral interventions for the treatment of aggression in individuals with developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2011;32(2):437–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KR, Sodawasser AJ, Hardee AM, Retzlaff BJ. Examining the reliability of the stimulus avoidance assessment. Behavioral Development. 2021;26(2):95–109. doi: 10.1037/bdb0000105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KR, Hurd AM, Layman LN, Peart A, Randall K. On stimulus avoidance assessment to inform treatment efficacy: A retrospective consecutive case series. Behavior Analysis: Research & Practice. 2023;23(4):275–289. doi: 10.1037/bar0000278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JM. Efficacy of behavioral interventions for reducing problem behavior in persons with autism: A quantitative synthesis of single-subject research. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2003;24(2):120–138. doi: 10.1016/S0891-4222(03)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper SA, Smiley E, Jackson A, Finlayson J, Allan L, Mantry D, Morrison J. Adults with intellectual disabilities: prevalence, incidence and remission of aggressive behaviour and related factors. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2009;53(3):217–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL. Applied behavior analysis. 3. Pearson Education; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker AG, Mercier C, Lachapelle Y, Brunet A, Morin D, Roy ME. Prevalence and types of aggressive behaviour among adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006;50(9):652–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker MC, Koot HM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, & Allied Disciplines. 2002;43(8):1087–1098. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *DeRosa, N. M., Roane, H. S., Bishop, J. R., & Silkowski, E. L. (2016). The combined effects if noncontingent reinforcement and punishment on the reduction of rumination. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 49(3), 680–685. 10.1002/jaba.304 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Doughty SS, Poe SG, Anderson CM. Effects of punishment and response-independent attention on severe problem behavior and appropriate toy play. Journal of Early & Intensive Behavior Intervention. 2005;2(2):91–98. doi: 10.1037/h0100303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson E, Kiernan C, Alborz A, Reeves D, Mason H, Swarbrick R, Mason L, Hatton C. The prevalence of challenging behaviors: A total population study. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2001;22(1):77–93. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(00)00061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcomata TS, Roane HS, Hovanetz AN, Kettering TL, Keeney KM. An evaluation of response cost in the treatment of inappropriate vocalizations maintained by automatic reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37(1):83–87. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn CA, Sladeczek IE. Assessing the social validity of behavioral interventions: A review of treatment acceptability measures. School Psychology Quarterly. 2001;16(2):176–206. doi: 10.1521/scpq.16.2.176.18703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza CC, Bowman LG, Hagopian LP, Owens JC, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25(2):491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Fisher, W., Piazza, C. C., Bowman, L. G., Hagopian, L. P., & Langdon, N. A. (1994a). Empirically derived consequences: A data-based method for prescribing treatments for destructive behavior. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 15(2), 133–149. 10.1016/0891-4222(94)90018-3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- *Fisher, W. W., Piazza, C. C., Bowman, L. G., Kurtz, P. F., Sherer, M. R., & Lachman, S. R. (1994b). A preliminary evaluation of empirically derived consequences for the treatment of pica. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27(3), 447–457. 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Haddock JN, Hagopian LP. Competing stimulus assessments: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(4):1982–2001. doi: 10.1002/jaba.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian LP, Fisher WW, Sullivan MT, Acquisto J, LeBlanc LA. Effectiveness of functional communication training with and without extinction and punishment: A summary of 21 inpatient cases. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31(2):211–235. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian LP, Long ES, Rush KS. Preference assessment procedures for individuals with developmental disabilities. Behavior Modification. 2004;28(5):668–677. doi: 10.1177/0145445503259836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian LP, Boelter EW, Jarmolowicz DP. Reinforcement schedule thinning following functional communication training: Review and recommendations. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2011;4:4–16. doi: 10.1007/BF03391770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP, Iwata BA, McCord BE. Functional analysis of problem behavior: A review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36(2):147–185. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP, Piazza CC, Fisher WW, Maglieri KA. On the effectiveness of and preference for punishment and extinction components of function-based interventions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38(1):51–65. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.6-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyvaert M, Saenen L, Campbell JM, Maes B, Onghena P. Efficacy of behavioral interventions for reducing problem behavior in persons with autism: An updated quantitative synthesis of single-subject research. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014;35(10):2463–2476. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner RH, Carr EG, Strain PS, Todd AW, Reed HK. Problem behavior interventions for young children with autism: A research synthesis. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2002;32:423–446. doi: 10.1023/A:1020593922901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd AM, Nercesian SJ, Brown KR, Visser EJ. A systematic review on functional analysis of noncompliance. Education & Treatment of Children. 2023;46:45–58. doi: 10.1007/s43494-023-00091-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jessel J, Metras R, Hanley GP, Jessel C, Ingvarsson ET. Evaluating the boundaries of analytic efficiency and control: A consecutive controlled case series of 26 functional analyses. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(1):25–43. doi: 10.1002/jaba.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, O’Reilly M, Lancioni G, Falcomata TS, Sigafoos J, Xu Z. Comparison of the predictive validity and consistency among preference assessment procedures: A review of the literature. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2013;34(4):1125–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranak, M. P., & Brown, K. R. (2023). Updated recommendations for reinforcement schedule thinning following functional communication training. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 1–20. 10.1007/s40617-023-00863-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kuhn D, Hagopian L, Terlonge C. Treatment of life-threatening self-injurious behavior secondary to hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type II: A controlled case study. Journal of Child Neurology. 2008;23(4):381–388. doi: 10.1177/0883073807309236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kurtz, P. F., Chin, M. D., Huete, J. M., Tarbox, R. S., O’Connor, J. T., Paclawskyj, T. R., & Rush, K. S. (2003). Functional analysis and treatment of self-injurious behavior in young children: A summary of 30 cases. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36(2), 205–219. 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- *Kurtz, P. F., Chin, M. D., Robinson, A. N., O’Connor, J. T., & Hagopian, L. P. (2015). Functional analysis and treatment of problem behavior exhibited by children with fragile X syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 43-44, 150–166. 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lerman DC, Vorndran CM. On the status of knowledge for using punishment: Implications for treating behavior disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35(4):431–464. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analysis of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151(4):23–65. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydon S, Healy O, Moran L, Foody C. A quantitative examination of punishment research. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2015;36:470–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Manente, C. J., & LaRue, R. H. (2017). Treatment of self-injurious behavior using differential punishment of high rates of behavior (DPH). Behavioral Interventions, 32(3), 262–271. 10.1002/bin.1477

- Melanson, I. J., & Fahmie, T. A. (2023). Functional analysis of problem behavior: A 40‐year review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 10.1002/jaba.983 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Michael, J. L. (1993). Concepts and principles of behavior analysis. Society for the Advancement of Behavior Analysis.

- *Migan-Gandonou, J. A., & Leon, Y. (2020). Empirically derived consequences to treatment rumination. Behavioral Interventions, 35(1), 166–177. 10.1002/bin.1698

- *Mitteer, D. R., Romani, P. W., Greer, B. D., & Fisher W. W. (2015). Assessment and treatment of pica and destruction of holiday decorations. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 48(4), 912—917. 10.1002/jaba.255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pace GM, Ivancic MT, Edwards GL, Iwata BA, Page TJ. Assessment of stimulus preference and reinforcer value with profoundly retarded individuals. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1985;18(3):249–255. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1985.18-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorski EA, Barton EE. A systematic review of the ethics of punishment-based procedures for young children with disabilities. Remedial & Special Education. 2021;42(4):262–275. doi: 10.1177/0741932520918859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaraman A, Hanley GP. Mand compliance as a contingency controlling problem behavior: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2021;54(1):103–121. doi: 10.1002/jaba.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatgi, A. (2022). WebPlotDigitizer (Version 4.6) [Computer software]. https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer/

- Rooker GW, Bonner AC, Dillon CM, Zarcone JR. Behavioral treatment of automatically reinforced SIB: 1982–2015. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2018;51(4):974–997. doi: 10.1002/jaba.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooker GW, Hagopian LP, Becraft JL, Javed N, Fisher AB, Finney KS. Injury characteristics across functional classes of self-injurious behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(2):1042–1057. doi: 10.1002/jaba.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Simmons, C. A., Zangrillo, A. N., Fisher, W. W., & Zemantic, P. K. (2021).An evaluation of a caregiver-implemented stimulus avoidance assessment and corresponding treatment package. Behavioral Development, 27(1–2), 1–20. 10.1037/bdb0000107

- *Toole, L. M., DeLeon, I. G., Kahng, S., Ruffin, G. E., Pletcher, C. A., & Bowman, L. G. (2004). Re-evaluation of constant versus varied punishers using empirically derived consequences. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 25(6), 577–586. 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Van Houten R, Axelrod S, Bailey JS, Favell JE, Foxx RM, Iwata BA, Lovaas OI. The right to effective behavioral treatment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1988;21(4):381–384. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1988.21-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verriden AL, Roscoe EM. An evaluation of a punisher assessment for decreasing automatically reinforced problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2019;52(1):205–226. doi: 10.1002/jaba.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins N, Rapp JT. Environmental enrichment and response cost: Immediate and subsequent effects on stereotypy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2014;47(1):186–191. doi: 10.1002/jaba.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DW, Friman PC, Teng EJ. Tic disorders, trichotillomania, and other repetitive behavior disorders. Springer; 2001. Physical and social impairment in persons with repetitive behavior disorders; pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no original datasets were generated during the current study.