Abstract

Background

Preterm birth is a major complication of pregnancy associated with perinatal mortality and morbidity. Progesterone for the prevention of preterm labour has been advocated.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth for women considered to be at increased risk of preterm birth and their infants.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (14 January 2013) and reviewed the reference list of all articles.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials, in which progesterone was given for preventing preterm birth.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently evaluated trials for methodological quality and extracted data.

Main results

Thirty‐six randomised controlled trials (8523 women and 12,515 infants) were included.

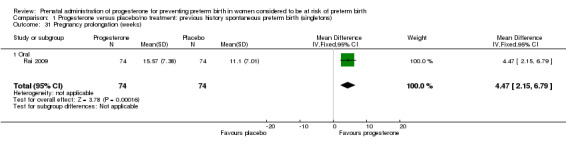

Progesterone versus placebo for women with a past history of spontaneous preterm birth Progesterone was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the risk of perinatal mortality (six studies; 1453 women; risk ratio (RR) 0.50, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.33 to 0.75), preterm birth less than 34 weeks (five studies; 602 women; average RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.69), infant birthweight less than 2500 g (four studies; 692 infants; RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.79), use of assisted ventilation (three studies; 633 women; RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.90), necrotising enterocolitis (three studies; 1170 women; RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.89), neonatal death (six studies; 1453 women; RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.76), admission to neonatal intensive care unit (three studies; 389 women; RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.40), preterm birth less than 37 weeks (10 studies; 1750 women; average RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.74) and a statistically significant increase in pregnancy prolongation in weeks (one study; 148 women; mean difference (MD) 4.47, 95% CI 2.15 to 6.79). No differential effects in terms of route of administration, time of commencing therapy and dose of progesterone were observed for the majority of outcomes examined.

Progesterone versus placebo for women with a short cervix identified on ultrasound Progesterone was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the risk of preterm birth less than 34 weeks (two studies; 438 women; RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.90), preterm birth at less than 28 weeks' gestation (two studies; 1115 women; RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.93) and increased risk of urticaria in women when compared with placebo (one study; 654 women; RR 5.03, 95% CI 1.11 to 22.78). It was not possible to assess the effect of route of progesterone administration, gestational age at commencing therapy, or total cumulative dose of medication.

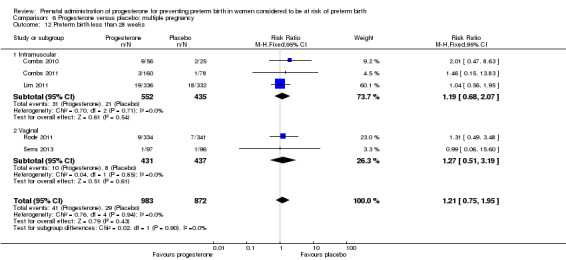

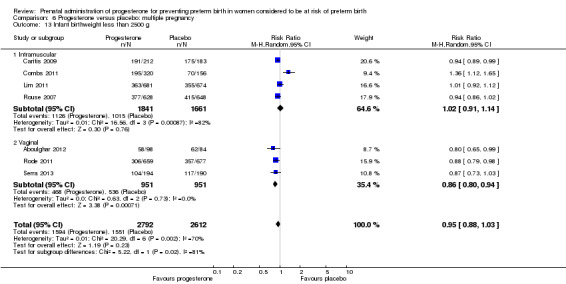

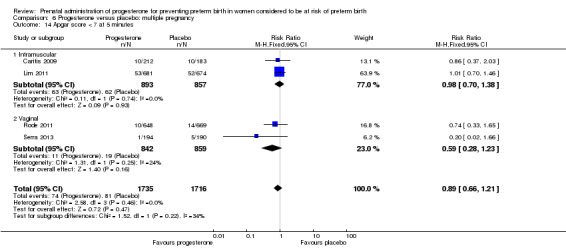

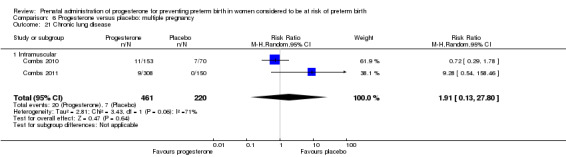

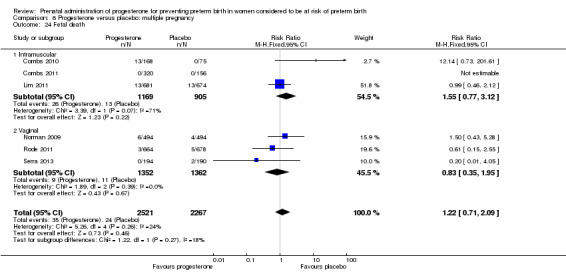

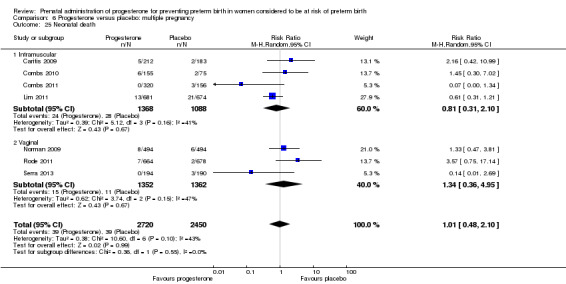

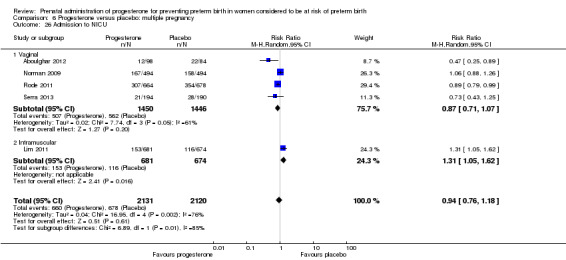

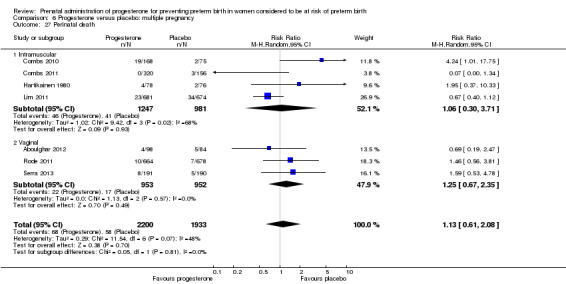

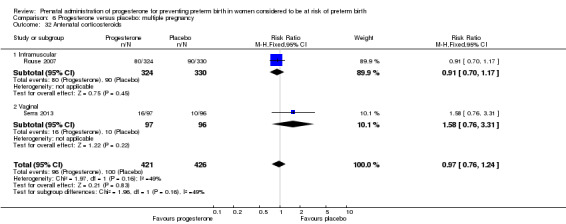

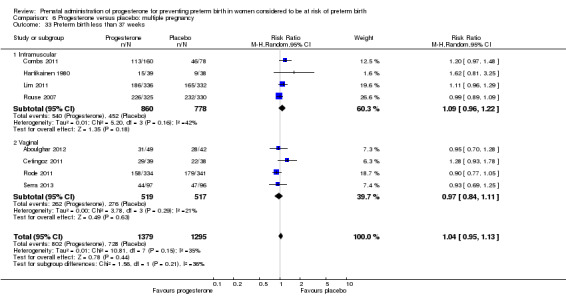

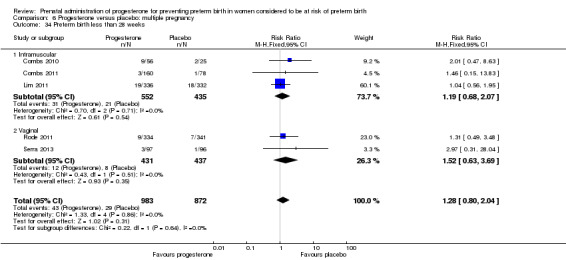

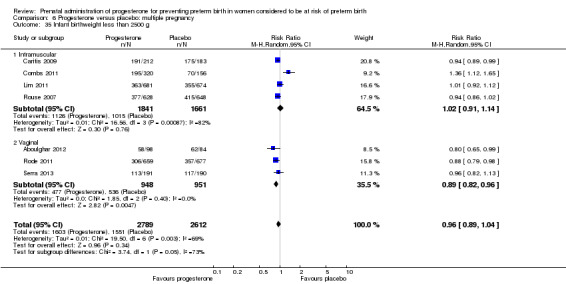

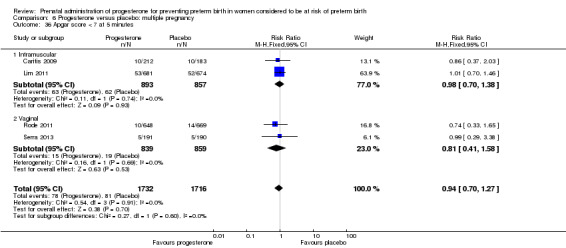

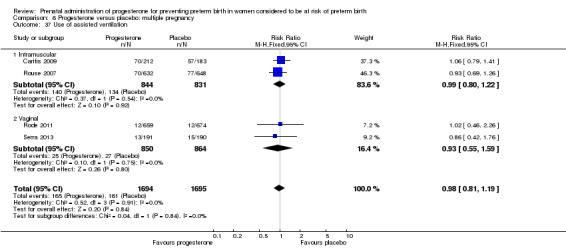

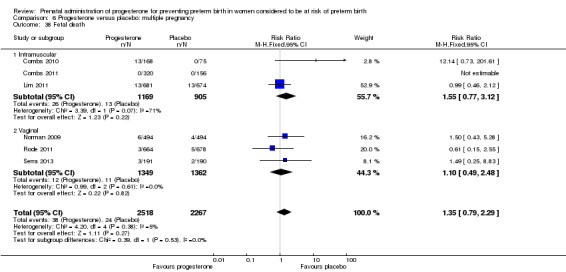

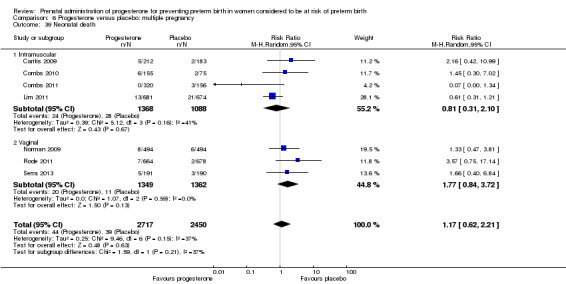

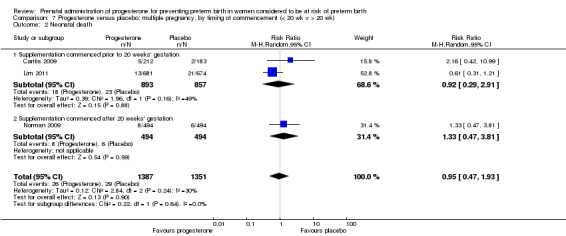

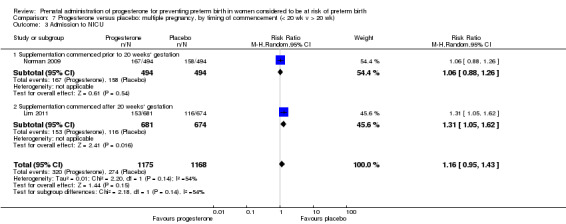

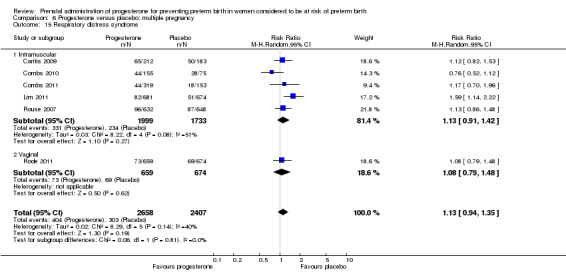

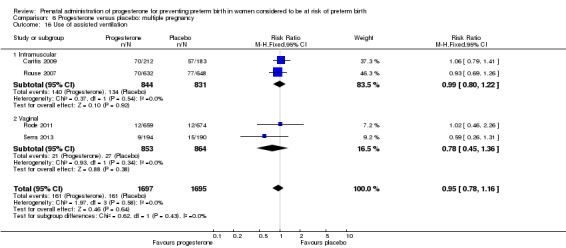

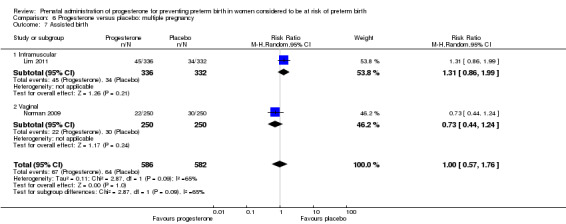

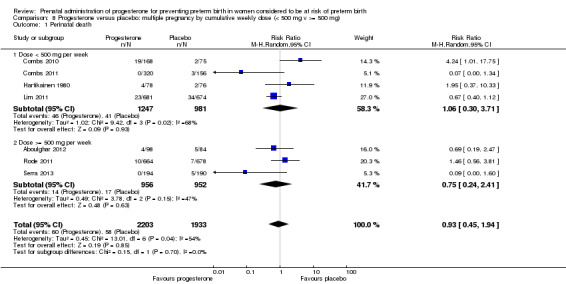

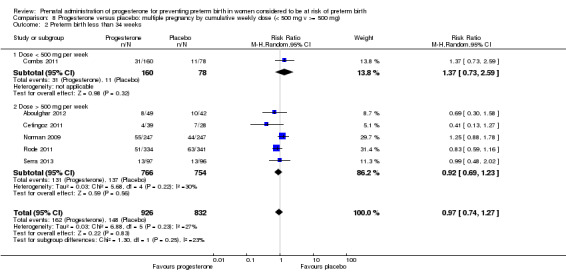

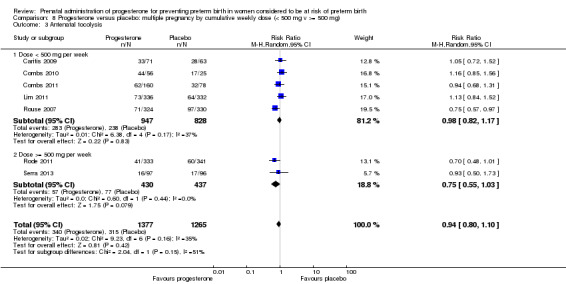

Progesterone versus placebo for women with a multiple pregnancy Progesterone was associated with no statistically significant differences for the reported outcomes.

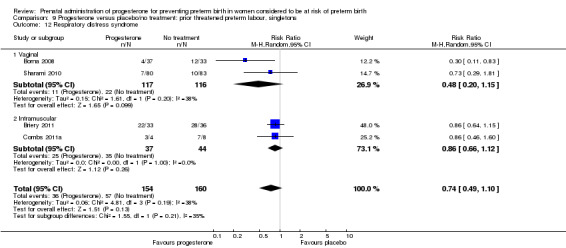

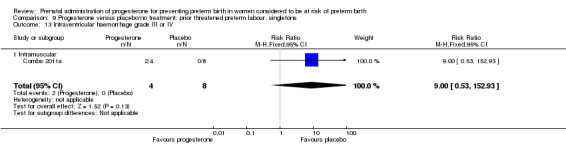

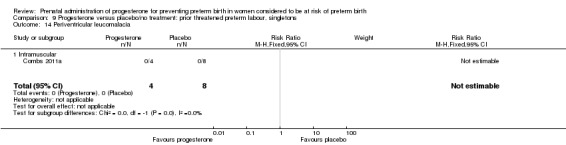

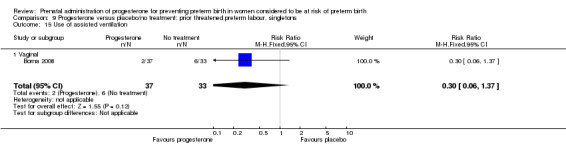

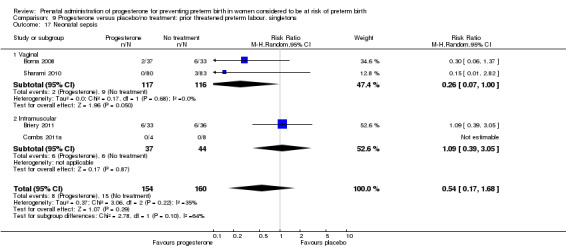

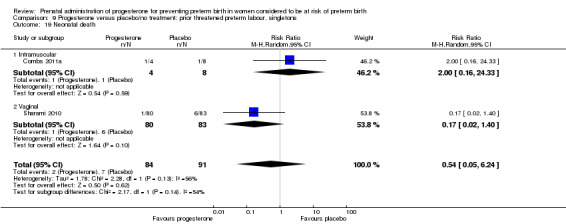

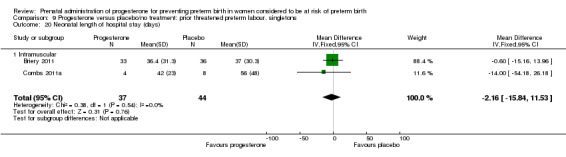

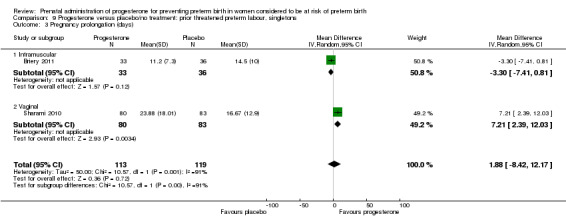

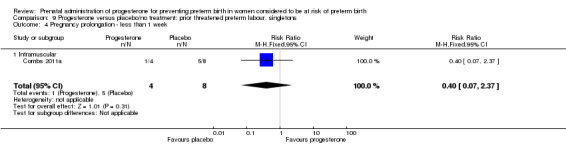

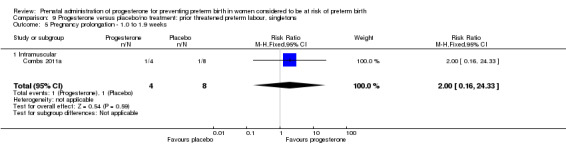

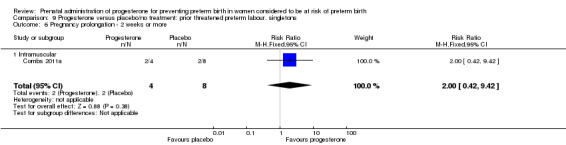

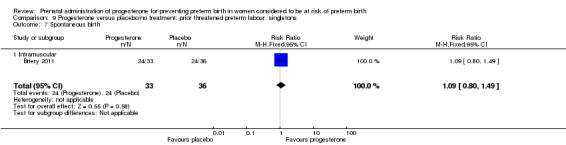

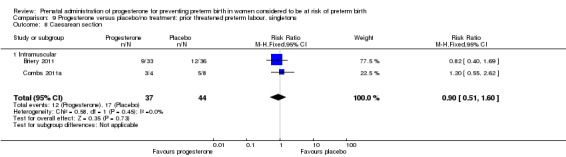

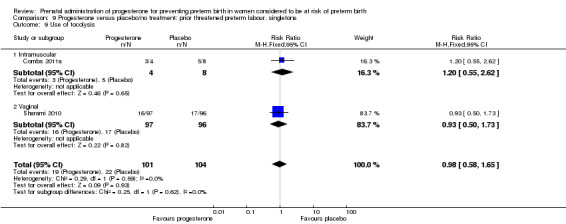

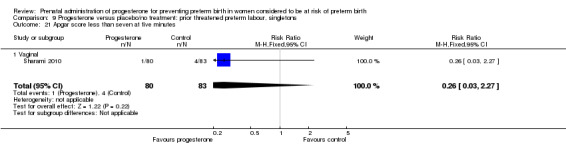

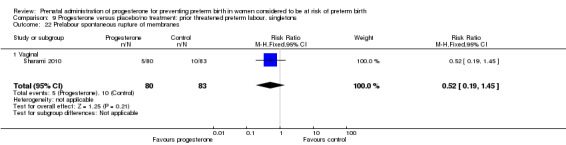

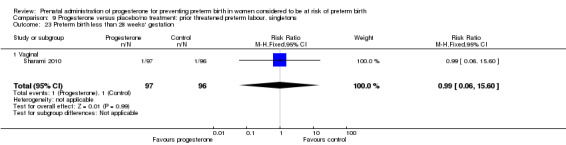

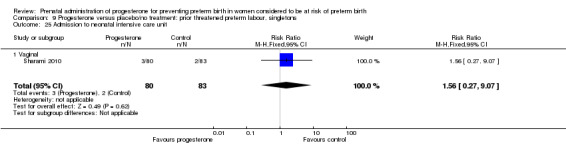

Progesterone versus no treatment/placebo for women following presentation with threatened preterm labour Progesterone, was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the risk of infant birthweight less than 2500 g (one study; 70 infants; RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.98).

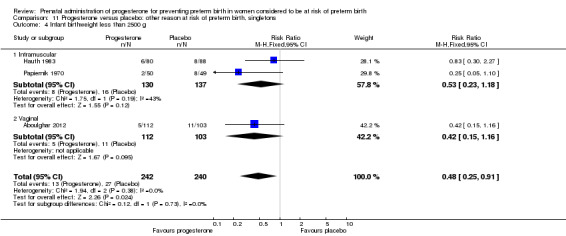

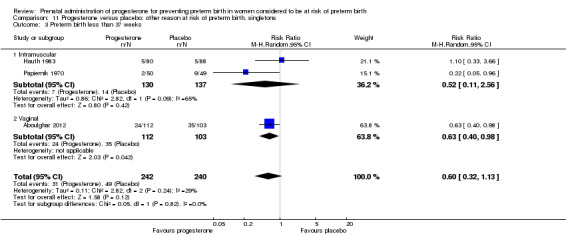

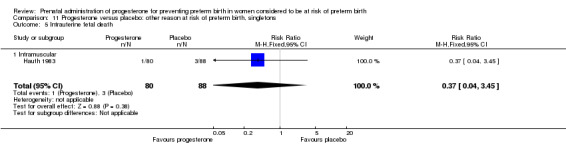

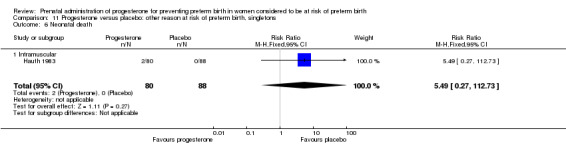

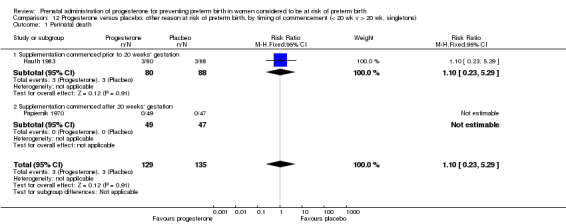

Progesterone versus placebo for women with 'other' risk factors for preterm birth Progesterone, was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the risk of infant birthweight less than 2500 g (three studies; 482 infants; RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.91).

Authors' conclusions

The use of progesterone is associated with benefits in infant health following administration in women considered to be at increased risk of preterm birth due either to a prior preterm birth or where a short cervix has been identified on ultrasound examination. However, there is limited information available relating to longer‐term infant and childhood outcomes, the assessment of which remains a priority.

Further trials are required to assess the optimal timing, mode of administration and dose of administration of progesterone therapy when given to women considered to be at increased risk of early birth.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; 17‐alpha‐Hydroxyprogesterone; 17‐alpha‐Hydroxyprogesterone/administration & dosage; 17‐alpha‐Hydroxyprogesterone/adverse effects; Pregnancy, High‐Risk; Premature Birth; Premature Birth/prevention & control; Prenatal Care; Prenatal Care/methods; Progesterone; Progesterone/administration & dosage; Progesterone/adverse effects; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Prenatal administration of progesterone to prevent preterm birth in women considered to be at risk of having their baby early

Babies who are born before 37 weeks, and particularly those born before 34 weeks, are at greater risk of having problems at birth and complications in infancy. Infants who are born preterm are at greater risk of dying in their first year of life, and of those infants who survive, there is an increased risk of repeated admission to hospital and adverse outcomes including cerebral palsy and long‐term disability. Progesterone is a hormone that reduces contractions of the uterus and has an important role in maintaining pregnancy and is suggested for the prevention of preterm labour. Maternal side‐effects from progesterone therapy include headache, breast tenderness, nausea, cough and local irritation if administered intramuscularly. At present, there is little information available regarding the optimal dose of progesterone, mode of administration, gestation to commence therapy, or duration of therapy.

The review of 36 randomised controlled trials, involving a total of 8523 women considered to be at increased risk of preterm birth, and 12,515 infants, found that where progesterone was given (by injection into the muscle in some studies and as a pessary into the vagina in others), it had beneficial effects, including reducing the risk of the baby dying after birth, suffering complications such as requiring assisted ventilation, necrotising enterocolitis or requiring admission to neonatal intensive care, prolonging the pregnancy, and reducing the chance of neonatal intensive care admission.

Information related to longer‐term infant and childhood outcomes was limited. Overall, the trials included in this review were considered to be of good to fair quality. Further trials are required to assess the optimal timing, mode of administration and dose of administration of progesterone therapy.

Background

Description of the condition

Preterm birth before 37 weeks' gestation is a common problem in obstetric care, with estimates ranging from 5% in several European countries to 18% in some African countries (Blencowe 2012). In Australia, approximately 8% of all infants were born preterm in 2000, with 2.7% of these births occurring prior to 34 weeks' gestation (AIHW 2003). Figures are similar for the United States, with a preterm birth rate of 12.0% (Blencowe 2012). While less than 2% of these infants were born prior to 32 weeks' gestation (Martin 2003), they are at increased risk of complications in infancy, and contribute in excess of 50% of the overall perinatal mortality (AIHW 2003). Infants who are born preterm are at greater risk of dying in their first year of life (Martin 2003), and of those infants who survive, there is an increased risk of repeated admission to hospital (Elder 1999) and adverse outcomes including cerebral palsy and long‐term disability (Hack 1999; Stanley 1992), creating a significant burden upon the community (Kramer 2000).

The 'cause' of preterm labour is multifactorial in origin, and it is important to consider the role of any identifiable risk factors in a woman's pregnancy.

The most significant and consistently identified risk factor for preterm birth, is a woman's history of previous preterm birth (Adams 2000; Bakketeig 1979; Berkowitz 1993; Bloom 2001; Goldenberg 1998; Kaminski 1973; Kistka 2007; Papiernik 1974; Petrini 2005; Robinson 2001). Estimates suggest the rate of recurrent preterm birth in this group of women to be 22.5% (Petrini 2005), a 2.5 times increased risk ratio when compared with women with no previous spontaneous preterm birth (Mercer 1999). For women with a history of a single preterm birth, the recurrence risk in a subsequent pregnancy is approximately 15%, increasing to 32% where there have been two previous preterm births (Carr‐Hill 1985). Information derived from population‐based cohort data suggests that for women who give birth between 20 and 31 weeks' gestation in one pregnancy, 29.3% will give birth prior to 37 weeks in a subsequent pregnancy (Adams 2000). For approximately 10% of these women, the preterm birth will occur at a similar gestational age (Adams 2000; Kistka 2007). In up to 50% of cases of preterm birth, the cause is spontaneous onset of labour or preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) (Hewitt 1988; Mattison 2001; McLaughlin 2002).

Other characteristics in a woman's current pregnancy may place her at increased risk of preterm birth, including women with a short cervix identified by ultrasound assessment, the presence of fetal fibronectin in the vaginal secretions, and presentation with symptoms or signs of threatened preterm labour.

The identification of a short cervix (considered to be less than 2.5cm) on ultrasound examination has been associated with an increased likelihood of preterm birth before 34 weeks’ gestation (Smith 2007). Identification of fetal fibronectin present in cervico‐vaginal secretions has also been proposed as a means of identifying women at risk of preterm birth. Overall, the value of fetal fibronectin in women presenting with symptoms of threatened preterm labour, is a negative test, where women are unlikely to proceed to preterm birth before 34 weeks’ gestation or within seven days of testing (Smith 2007).

Multiple pregnancy is a strong risk factor for preterm birth though the mechanisms may be different to those operating in women with a singleton pregnancy. Up to 50% of women with a twin pregnancy will give birth prior to 37 weeks' gestation (AIHW 2003). The preterm birth risk of early birth before 37 weeks for women with a singleton pregnancy is 6.3% compared with 97% for women with a triplet pregnancy (AIHW 2003).

Description of the intervention

Progesterone may be administered in various forms and by various routes. These different formulations and modes of administration will have different absorption patterns and potentially have differing bio effects. Whilst no teratogenic effects have been described with most progesterones, there is little in the way of long‐term safety data. Maternal side‐effects from progesterone therapy include headache, breast tenderness, nausea, cough and local irritation if administered intramuscularly. At present, there is little information available regarding the optimal dose of progesterone, mode of administration, gestation to commence therapy, or duration of therapy (Greene 2003; Iams 2003).

How the intervention might work

Progesterone has a role in maintaining pregnancy (Haluska 1997; Pepe 1995; Pieber 2001) and is thought to act by suppressing smooth muscle activity in the uterus (Astle 2003; Grazzini 1998). In many animal species, there is a reduction in the amount of circulating progesterone before the onset of labour. While these changes have not been shown to occur in women (Astle 2003; Block 1984; Lopez‐Bernal 2003; Pieber 2001; Smit 1984), it has been suggested that there is a 'functional' withdrawal of progesterone related to changes in the expression of progesterone receptors in the uterus (Astle 2003; Condon 2003; Haluska 2002; Pieber 2001). There have been recent reports in the literature advocating the use of progesterone to reduce the risk of preterm birth (da Fonseca 2003; Meis 2003), rekindling interest that dates back to the 1960s (Le Vine 1964).

This review was modified in 2006, from the original protocol published in The Cochrane Library in Issue 4, 2004, in order to clarify the scope of the review. The title and objectives changed, and the description of participants expanded to include the reason the women were considered to be at increased risk of preterm birth. The primary outcome measure of preterm birth less than 32 weeks' gestation has been changed to preterm birth less than 34 weeks' gestation to be consistent with World Health Organization definitions of preterm birth. Secondary outcome measures reflecting childhood developmental assessment have been added, reflecting the need for ongoing evaluation of children participating in randomised trials.

Why it is important to do this review

Preterm birth and its consequences for women and their babies is a significant health problem in pregnancy and childbirth. While the suppression or prevention of preterm labour should lead to improved survival through a lower incidence of premature delivery, there are theoretical reasons why a fetus may not survive without disability. It is possible that an intrauterine mechanism that would trigger preterm labour could also cause neurological injury to the fetus and that progesterone may prevent labour but not fetal injury. The purpose of this review is to assess the benefits and harms of progesterone administration for the prevention of preterm birth for both women and their infants, when considering the risk factors present for preterm birth.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of progesterone administration for the prevention of preterm birth in women and their infants.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published and unpublished randomised controlled trials, in which progesterone was administered for the prevention of preterm birth, subdivided by the reason women were considered to be at risk for preterm birth.

Trials were excluded if:

they utilised quasi‐randomised methodology; cross‐over design;

progesterone was administered for the acute treatment of actual or threatened preterm labour (that is, where progesterone was administered as an acute tocolytic medication); or

progesterone was administered in the first trimester only for preventing miscarriage.

Types of participants

Pregnant women considered to be at increased risk of preterm birth. These reasons include:

past history of spontaneous preterm birth (including preterm prelabour rupture of membranes);

multiple pregnancy;

ultrasound identified short cervical length;

fetal fibronectin testing;

following acute presentation with symptoms or signs of threatened preterm labour (where a tocolytic medication may have been administered);

other reason considered to be at increased risk of preterm birth.

Types of interventions

Administration of progesterone by any route for the prevention of preterm birth.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Perinatal mortality

Preterm birth (less than 34 weeks' gestation)

Major neurodevelopmental handicap at childhood follow‐up

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

Threatened preterm labour (as defined by trial authors)

Prelabour spontaneous rupture of membranes

Adverse drug reaction

Pregnancy prolongation (interval between randomisation and birth)

Mode of birth

Number of antenatal hospital admissions

Satisfaction with the therapy

Use of tocolysis

Antenatal corticosteroids (not a prespecified outcome)

Maternal quality of life (not a prespecified outcome)

Infant

Birth before 37 completed weeks

Birth before 28 completed weeks

Birthweight less than the third centile for gestational age

Birthweight less than 2500 g

Apgar score of less than seven at five minutes

Respiratory distress syndrome

Use of mechanical ventilation

Duration of mechanical ventilation

Intraventricular haemorrhage ‐ grades III or IV

Periventricular leucomalacia

Retinopathy of prematurity

Retinopathy of prematurity ‐ grades III or IV

Chronic lung disease

Necrotising enterocolitis

Neonatal sepsis

Fetal death

Neonatal death

Admission to neonatal intensive care unit

Neonatal length of hospital stay

Teratogenic effects (including virilisation in female infants)

Patent ductus arteriosis (not a prespecified outcome)

Child

Major sensorineural disability (defined as any of legal blindness, sensorineural deafness requiring hearing aids, moderate or severe cerebral palsy, or developmental delay or intellectual impairment (defined as developmental quotient or intelligence quotient less than ‐2 standard deviations below mean))

Developmental delay (however defined by the authors)

Intellectual impairment

Motor impairment

Visual impairment

Blindness

Deafness

Hearing impairment

Cerebral palsy

Child behaviour

Child temperament

Learning difficulties

Growth assessments at childhood follow‐up (weight, head circumference, length, skin fold thickness)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (14 January 2013).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of Embase;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

For details of searching carried out for the initial version of the review, please see Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We also manually cross‐referenced key publications.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, see Appendix 2.

For this update we used the following methods when assessing the reports identified by the updated search.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted third author. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2012) and checked for accuracy. When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we contacted authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving the third author.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We planned to assess blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We planned to assess blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups; or less than 20% losses to follow‐up);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found. We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other sources of bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether studies that included multiple pregnancies accounted appropriately for non‐independence of babies from the same pregnancy in the analysis. There are several ways this can be done, and these studies should present something like an odds ratio adjusted for non‐independence. If adjustment was not done, we assessed the potential for bias i.e. if multiples only made up a small proportion of the total then there is probably not much potential for bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it likely to impact on the findings. We planned to explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We planned to use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods, if required.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not identify any cluster‐randomised trials for inclusion in this review, but we may include trials of this type in future updates. If we do, we plan to include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. Their sample sizes will be adjusted using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011) using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), or from another source. If ICCs from other sources are used, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we planned to synthesise the relevant information. We consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely. We also planned to acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials were not included.

Other unit of analysis issues

The analysis in this review involves multiple pregnancies, therefore, wherever possible, analyses should be adjusted for clustering to take into account the non‐independence of babies from the same pregnancy (Gates 2004). Treating babies from multiple pregnancies as if they are independent, when they are more likely to have similar outcomes than babies from different pregnancies, will overestimate the sample size and give confidence intervals that are too narrow. Each woman can be considered a cluster in multiple pregnancy, with the number of individuals in the cluster being equal to the number of fetuses in her pregnancy. Analysis using cluster trial methods allows calculation of relative risk and adjustment of confidence intervals. Usually this will mean that the confidence intervals get wider. Although this may make little difference to the conclusion of a trial, it avoids misleading results in those trials where the difference may be substantial.

We planned to adjust for clustering in the analyses, wherever possible, and to use the inverse variance method for adjusted analyses, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). However, due to insufficient information in the included trials, we were not able to adjust our analyses. In future updates, if possible, we will adjust for clustering in the analyses.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We explored the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis. For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if an I² was greater than 30% and either the T² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If 10 or more studies contributed data to meta‐analysis for any particular outcome, we investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We assessed possible asymmetry visually. If asymmetry was suggested by a visual assessment, we planned to perform exploratory analyses to investigate it. In this version of the review insufficient data were available to allow us to carry out this planned analysis.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the RevMan software (RevMan 2012). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials examined the same intervention, and where we judged the trials’ populations and methods to be sufficiently similar. If we suspected clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect the underlying treatment effects to differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary provided that we considered an average treatment effect across trials was clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials is discussed. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful we did not combine trials.

Where we used random‐effects analyses, the results were presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of T² and I².

Results were analysed according to the reason women were considered to be at risk of preterm birth, including:

past history of spontaneous preterm birth (including preterm prelabour rupture of membranes);

multiple pregnancy;

ultrasound identified short cervical length;

fetal fibronectin testing;

presentation with symptoms or signs of threatened preterm labour;

other reason for risk of preterm birth.

For analyses where there are high levels of heterogeneity we have provided an estimate of the 95% range of underlying intervention effects (prediction interval).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, we used random‐effects analysis to produce it. We planned, where possible, to carry out the following subgroup analyses:

time of treatment commencing (before 20 weeks' gestation versus after 20 weeks' gestation);

route of administration (intramuscular, intravaginal, oral, intravenous);

different dosage regimens (divided arbitrarily into a cumulative dose of less than 500 mg per week and a dose of greater than or equal to 500 mg per week).

All outcomes were considered in subgroup analyses.

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2012).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates (greater than 20%), or both, with poor‐quality studies being excluded from the analyses in order to assess whether this made any difference to the overall result.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

In the 2006 update, our search strategy identified 22 studies for consideration. Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria stated (Borna 2008; da Fonseca 2003; Facchinetti 2007; Fonseca 2007; Hartikainen 1980; Hauth 1983; Johnson 1975; Meis 2003; O'Brien 2007; Papiernik 1970; Rouse 2007) involving a total of 2714 women and 3452 infants. The study by Northern (Northen 2007) reports the follow‐up of children involved in the Meis study (Meis 2003).

Sixty‐four reports from an updated search in January 2013 have been assessed for this update. Of these 64 reports, an additional 25 studies (33 reports) to the original 11 studies, were included (Aboulghar 2012; Akbari 2009; Briery 2011; Caritis 2009; Cetingoz 2011; Combs 2010; Combs 2011; Combs 2011a; Elsheikhah 2010; Glover 2011; Grobman 2012; Hassan 2011; Ibrahim 2010; Lim 2011; Majhi 2009; Moghtadaei 2008; Ndoni 2010; Norman 2009; Rai 2009; Rode 2011; Rozenberg 2012; Saghafi 2011a; Senat 2012; Serra 2013; Sharami 2010); seven studies (seven reports) were excluded (Abbott 2012; Arikan 2011; Berghella 2010; Chandiramani 2012; Ionescu 2012; Keeler 2009; Rust 2006); two studies (two reports) are ongoing studies (Coomarasamy 2012; van Os 2011); one is an additional report of an ongoing study (Crowther 2007); one additional report was added to each of the following included studies (Combs 2010; Combs 2011; Facchinetti 2007; Lim 2011; Nassar 2007). Two additional reports were identified for the Norman 2009; O'Brien 2007; Rode 2011 and Rouse 2007 included studies. Three additional reports were identified for the Meis 2003 included study.

A total of 36 studies are included in this update.

Included studies

Refer to table Characteristics of included studies for further details.

Use of progesterone in women with a history of prior spontaneous preterm birth

Description of studies

Eleven studies were included involving a total of 1936 women with a past history of spontaneous preterm birth (Akbari 2009; Cetingoz 2011; da Fonseca 2003; Glover 2011; Johnson 1975; Ibrahim 2010; Majhi 2009; Meis 2003; O'Brien 2007; Rai 2009; Saghafi 2011a). Four studies compared weekly intramuscular injection with placebo (Ibrahim 2010; Johnson 1975; Meis 2003) or routine care (Saghafi 2011a); five studies compared daily vaginal progesterone, three with placebo (Cetingoz 2011; da Fonseca 2003; O'Brien 2007) and two with routine care (Akbari 2009; Majhi 2009); and two studies compared daily oral progesterone with placebo (Glover 2011; Rai 2009). Dose of progesterone administered varied from 90 mg daily (O'Brien 2007), to 100 mg daily (Akbari 2009; Cetingoz 2011; da Fonseca 2003; Majhi 2009), to 200 mg daily (Rai 2009), to 400 mg daily (Glover 2011), to 200 mg weekly (Rai 2009), to 250 mg weekly (Johnson 1975; Meis 2003; Saghafi 2011a). Supplementation commenced prior to 20 weeks' gestation in four trials (Glover 2011; Johnson 1975; Meis 2003; O'Brien 2007), and continued up to a gestational age varying from 24 weeks (Johnson 1975; Majhi 2009; Rai 2009), to 28 weeks (da Fonseca 2003), to 34 weeks (Akbari 2009; Cetingoz 2011), to 36 weeks (Ibrahim 2010; Meis 2003), and to 37 weeks (O'Brien 2007; Saghafi 2011a) gestation.

The primary outcomes reported by the trials related to the occurrence of preterm birth prior to 28 weeks' gestation (Rai 2009), 32 weeks' gestation (O'Brien 2007), 34 weeks' gestation (Akbari 2009; Majhi 2009), and 37 weeks' gestation (Akbari 2009; Cetingoz 2011; da Fonseca 2003; Ibrahim 2010; Johnson 1975; Majhi 2009; Meis 2003; Saghafi 2011a). Eight trials involved single centres (Akbari 2009; da Fonseca 2003; Glover 2011; Ibrahim 2010; Johnson 1975; Majhi 2009; Rai 2009; Saghafi 2011a), and two were multicentre trials (Meis 2003; O'Brien 2007), conducted principally from the United States of America (Glover 2011; Johnson 1975; Meis 2003; O'Brien 2007), India (Majhi 2009; Rai 2009), Iran (Akbari 2009; Saghafi 2011a), Egypt (Ibrahim 2010), Istanbul (Cetingoz 2011), and Brazil (da Fonseca 2003). The report by Northen 2007 reports childhood follow‐up of 348 participants in the Meis randomised trial (Meis 2003).

One study (Cetingoz 2011) included a mix of women with a history of prior preterm birth (n = 71) and women with a multiple pregnancy (n = 67) and the results for this study have been analysed separately for the two risk groups.

Use of progesterone in women with a short cervix identified on transvaginal ultrasound examination

Description of studies

Four studies were included involving 1560 women who were identified with a short cervix (various definitions: less than 15 mm (Fonseca 2007); less than 30 mm (Grobman 2012); between 10 and 20mm (Hassan 2011); and less than 25 mm (Rozenberg 2012)) at the time of transvaginal ultrasound examination. One study compared weekly intramuscular injection with placebo (Grobman 2012); one study compared twice weekly intramuscular injection with no treatment (Rozenberg 2012) and two studies compared daily intravaginal progesterone with placebo (Fonseca 2007; Hassan 2011). Dose of progesterone administered varied from 90 mg daily in the morning (Hassan 2011), to 200 mg nightly (Fonseca 2007), to 250 mg weekly (Grobman 2012), to 500 mg twice weekly (Rozenberg 2012). Supplementation commenced from 16 to 22 weeks' gestation in one study (Grobman 2012), from 19 to 23 weeks in another study (Hassan 2011), from 24 to 31 weeks in another study (Rozenberg 2012), and from 24 to 33 completed weeks of gestation in another study (Fonseca 2007).

The primary outcomes reported by the trials related to the occurrence of preterm birth prior to 33 weeks' gestation (Hassan 2011), 34 weeks' gestation (Fonseca 2007), 35 weeks' gestation (Grobman 2012), or 37 weeks' gestation (Grobman 2012) and time from randomisation to delivery in one study (Rozenberg 2012). All trials were multicentre conducted in centres worldwide, including the United Kingdom, USA, France, Greece, Chile and Brazil.

One study (Fonseca 2007) included a mix of singleton and twin pregnancies (226 singleton and 24 twin pregnancies), but due to the small proportion of twin pregnancies in this study, we have analysed all of this data within the short cervix subgroup.

Use of progesterone in women with a multiple pregnancy

Description of studies

Fourteen studies were included involving 3792 women; 11 trials with a twin pregnancy (Aboulghar 2012; Cetingoz 2011; Combs 2011; Elsheikhah 2010; Fonseca 2007; Hartikainen 1980; Norman 2009; Rode 2011; Rouse 2007; Senat 2012; Serra 2013), two trials with a triplet pregnancy (Caritis 2009; Combs 2010) or one trial with any multiple pregnancy, e.g. twins, triplets or quadruplets (Lim 2011). Six studies compared 250 mg weekly intramuscular progesterone injections with placebo (Caritis 2009; Combs 2010; Combs 2011; Hartikainen 1980; Lim 2011; Rouse 2007); one study compared 1000 mg weekly intramuscular progesterone injections with no treatment (Senat 2012); three studies compared intravaginal progesterone with placebo (Aboulghar 2012; Cetingoz 2011; Elsheikhah 2010), one at a daily dose of 100 mg (Cetingoz 2011), one at a daily dose of 200 mg (Elsheikhah 2010) and one at a daily dose of 400 mg Aboulghar 2012); one study compared 90 mg daily intravaginal gel with placebo (Norman 2009); and one study compared 100 mg daily oral progesterone with placebo (Rode 2011). One trial (Serra 2013) consisted of three groups and compared 200 mg daily intravaginal progesterone with 400 mg daily intravaginal progesterone with placebo. Supplementation commenced from 16 to 20 weeks' gestation in three studies (Caritis 2009; Lim 2011; Rouse 2007), from 16 to 22 weeks in one study (Combs 2010), from 16 to 24 weeks in one study (Combs 2011), from 18 to 24 weeks in one study (Aboulghar 2012; Rode 2011), from 24 to 34 weeks in two studies (Cetingoz 2011; Elsheikhah 2010), from 24 weeks' gestation in one study (Norman 2009), and from 28 completed weeks' of gestation in one study (Hartikainen 1980).

The primary outcomes reported by the trials related to the occurrence of preterm birth prior to 34 weeks' gestation (Aboulghar 2012; Cetingoz 2011; Rode 2011; Senat 2012) or 37 weeks' gestation (Aboulghar 2012; Cetingoz 2011; Serra 2013), delivery or fetal loss before 34 weeks' gestation (Norman 2009), delivery or fetal loss before 35 weeks' gestation (Caritis 2009), mean cervical length and mean gestational age at delivery (Elsheikhah 2010), perinatal death (Hartikainen 1980) or composite neonatal morbidity (Combs 2010; Combs 2011; Lim 2011; Senat 2012). Five trials were multicentre conducted in centres worldwide, including the United Kingdom, USA, the Netherlands, Denmark, Austria and France (Caritis 2009; Combs 2010; Combs 2011; Lim 2011; Norman 2009; Rode 2011; Rouse 2007) and four were single‐centre trials conducted in Istanbul, Egypt and Finland (Aboulghar 2012; Cetingoz 2011; Elsheikhah 2010; Hartikainen 1980).

Two studies included a mix of women with multiple and singleton pregnancies (Aboulghar 2012; Cetingoz 2011). One study (Aboulghar 2012) included a mix of women with singleton pregnancies (n = 215) and women with a multiple pregnancy (n = 91) all conceived by IVF/ICSI (in vitro fertilisation/intracytoplasmic sperm injection) and the results for this study have been analysed separately for the two risk groups: women at risk of preterm birth for 'other' reasons; and women with a multiple pregnancy. One study (Cetingoz 2011) included a mix of women with a history of prior preterm birth (n = 71) and women with a multiple pregnancy (n = 67) and the results for this study have been analysed separately for the two risk groups.

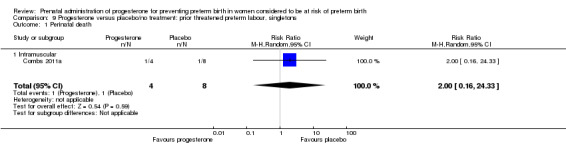

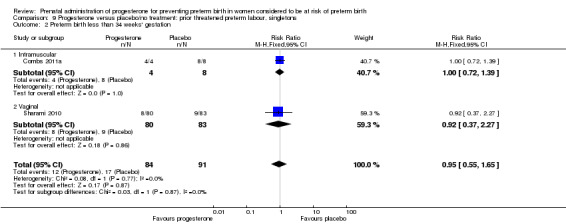

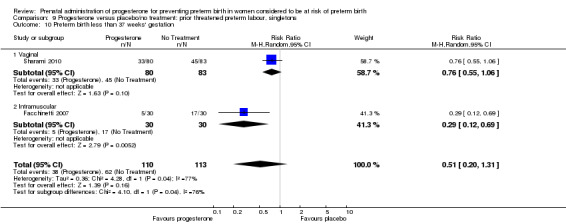

Use of progesterone in women following symptoms or signs of threatened preterm labour

Description of studies

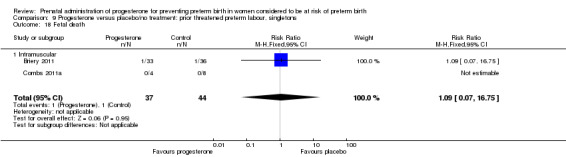

Six small studies were included involving a total of 505 women presenting with symptoms or signs of threatened preterm labour (Borna 2008; Briery 2011; Combs 2011a; Facchinetti 2007; Ndoni 2010; Sharami 2010). Two studies compared 250 mg weekly progesterone injections with placebo (Briery 2011; Combs 2011a), one study compared vaginal progesterone pessaries on a daily basis (400 mg) with no treatment (Borna 2008), one study compared 341 mg intramuscular progesterone injection every four days with no treatment (Facchinetti 2007), one study had three arms and compared intramuscular progesterone with oral progesterone with placebo (Ndoni 2010) and one study compared vaginal pessaries on a daily basis (200 mg) with placebo pessaries (Sharami 2010). Women presented with symptoms and signs between 24 and 34 weeks' gestation (Borna 2008), between 25 and 33 weeks' gestation (Facchinetti 2007), between 20 and 30 weeks' gestation (Briery 2011), between 23 and 31.9 weeks' gestation (Combs 2011a), between 15 and 22 weeks' gestation (Ndoni 2010) and between 28 and 36 weeks' gestation (Sharami 2010). The primary outcomes reported included the interval from randomisation to birth in one study (Borna 2008), transvaginal ultrasound assessment of cervical length in one study (Facchinetti 2007), gestational age at birth in one study (Briery 2011), prolongation of pregnancy and composite neonatal morbidity in one study (Combs 2011a) and time until delivery and birth before 34 or 37 completed weeks in one study (Sharami 2010). In one study, reported only in abstract form, data relating to outcomes was not reported (Ndoni 2010). One study was a multicentre study conducted in the USA (Combs 2011a) and the remaining five studies were single‐centre studies conducted in Iran, the USA, Italy, and Albania (Borna 2008; Briery 2011; Facchinetti 2007; Ndoni 2010; Sharami 2010).

Use of progesterone in women at risk of preterm birth for 'other' reasons

Description of studies

Papiernik 1970 recruited 99 women from Paris, France, in a single centred trial, with a 'high preterm risk score'. Women were allocated to receive intramuscular progesterone three times per week or placebo, from 28 to 32 weeks' gestation.

Hauth 1983 involved 168 women from the United States of America who were considered to be at risk of preterm birth due to active military service. Women received 1000 mg of progesterone weekly or placebo, from 16 to 20 weeks' gestation, up until 36 weeks' gestation. The primary outcome for the study related to the incidence of preterm birth at less than 37 weeks' gestation.

Moghtadaei 2008 involved 260 women from Iran, in a single centre trial, who were considered to be at risk of preterm birth due to advanced maternal age (greater than 35 years). Women received weekly injections of 17P (250 mg) starting at 16 to 20 weeks' gestation until 34 weeks or matching placebo. The main outcomes for the study included delivery before 37, 35 or 32 weeks' gestation, hypertension, diabetes, intrauterine growth restriction or side effects at the injection site. Data from this study could not be included in a meta‐analysis because the number of women randomised to each group was not reported in the brief abstract report of the study.

Aboulghar 2012 recruited 313 women from Egypt who were considered to be at high risk of preterm birth because all the pregnancies were conceived by IVF or ICSI. Women received vaginal progesterone 200 mg twice daily from randomisation until delivery or 37 weeks’ gestation or matching placebo. The primary outcomes included preterm birth of singleton and twin pregnancies before 37 completed weeks and before 34 completed weeks. This study contains a mix of singleton pregnancies (n = 215) and twin pregnancies (n = 91) and presented some outcome data separately, as well as for the whole group. The results for this study have been analysed separately for the two risk groups: multiple pregnancies and women at risk for 'other' reasons.

Excluded studies

In total, 16 studies were excluded (Abbott 2012; Arikan 2011; Berghella 2010; Breart 1979; Brenner 1962; Chandiramani 2012; Corrado 2002; Hobel 1986; Ionescu 2012; Keeler 2009; Le Vine 1964; Rust 2006; Suvonnakote 1986; Turner 1966; Walch 2005; Yemini 1985). Three studies were excluded as they used a quasi‐randomised method of treatment allocation (Le Vine 1964; Suvonnakote 1986; Yemini 1985). One study (Hobel 1986) compared an oral progestogen with placebo, but presented outcomes only as percentages. Five studies were excluded as progesterone was administered in the first trimester to prevent miscarriage (Breart 1979; Brenner 1962; Corrado 2002; Turner 1966; Walch 2005), and are covered by the Cochrane review relating to the use of progesterone for prevention of miscarriage (Haas 2008). One study was excluded because progesterone was administered as an acute tocolytic medication (Arikan 2011). A further six studies were excluded because they compared progesterone with cerclage (Abbott 2012; Chandiramani 2012; Ionescu 2012; Keeler 2009; Rust 2006) or compared cerclage with no cerclage (Berghella 2010), and are covered by other Cochrane reviews (Alfirevic 2012; Rafael 2011).

Refer to table Characteristics of excluded studies for further details.

Studies awaiting assessment

There are 11 ongoing studies awaiting assessment (Coomarasamy 2012; Creasy 2008; Crowther 2007; Martinez 2007; Nassar 2007; Norman 2012; Perlitz 2007; Starkey 2008; Swaby 2007; van Os 2011; Wood 2007).

Risk of bias in included studies

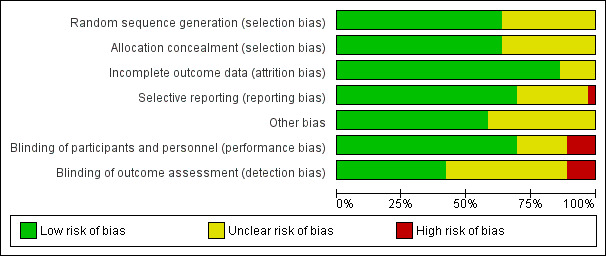

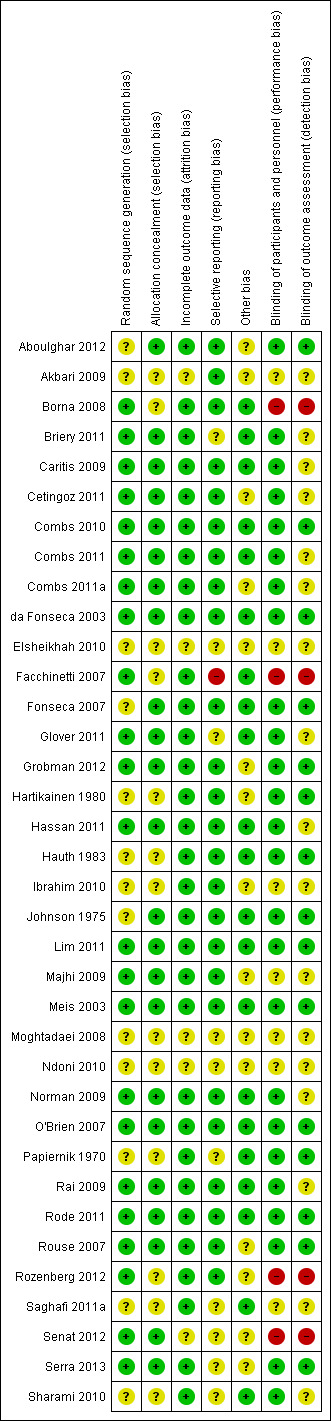

The overall quality of the included trials varied from good to fair. Refer to table Characteristics of included studies for further details and to Figure 1; Figure 2, for a summary of 'Risk of bias' assessments.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

While all trials were stated to be randomised and placebo controlled, the method of randomisation was only described in 23 trials (Borna 2008; Briery 2011; Caritis 2009; Cetingoz 2011; Combs 2010; Combs 2011; Combs 2011a; da Fonseca 2003; Facchinetti 2007; Glover 2011; Grobman 2012; Hassan 2011; Lim 2011; Majhi 2009; Meis 2003; Norman 2009; O'Brien 2007; Rai 2009; Rode 2011; Rouse 2007; Rozenberg 2012; Senat 2012; Serra 2013). Allocation concealment was assessed as low risk of bias in 23 trials (Aboulghar 2012; Briery 2011; Caritis 2009; Cetingoz 2011; Combs 2010; Combs 2011; Combs 2011a; da Fonseca 2003; Fonseca 2007; Glover 2011; Grobman 2012; Hassan 2011; Johnson 1975; Lim 2011; Majhi 2009; Meis 2003; Norman 2009; O'Brien 2007; Rai 2009; Rode 2011; Rouse 2007; Senat 2012; Serra 2013); and unclear in 13 trials (Akbari 2009; Borna 2008; Elsheikhah 2010; Facchinetti 2007; Hartikainen 1980; Hauth 1983; Ibrahim 2010; Moghtadaei 2008; Ndoni 2010; Papiernik 1970; Rozenberg 2012; Saghafi 2011a; Sharami 2010).

Blinding

Twenty‐five of the 32 included trials were placebo controlled, with blinding of caregivers and participants (Aboulghar 2012; Briery 2011; Caritis 2009; Cetingoz 2011; Combs 2010; Combs 2011; Combs 2011a; da Fonseca 2003; Fonseca 2007; Glover 2011; Grobman 2012; Hartikainen 1980; Hassan 2011; Hauth 1983; Johnson 1975; Lim 2011; Meis 2003; Norman 2009; O'Brien 2007; Papiernik 1970; Rai 2009; Rode 2011; Rouse 2007; Serra 2013; Sharami 2010).

Blinding of outcome assessment was evident in 15 of the trials (Aboulghar 2012; Combs 2010; da Fonseca 2003; Fonseca 2007; Grobman 2012; Hartikainen 1980; Hauth 1983; Johnson 1975; Lim 2011; Meis 2003; O'Brien 2007; Papiernik 1970; Rode 2011; Rouse 2007; Serra 2013).

Four trials were assessed as high risk of bias for both blinding of caregivers and participants and outcome assessment as no blinding was attempted (Borna 2008; Facchinetti 2007; Rozenberg 2012; Senat 2012).

Incomplete outcome data

Thirty‐one studies were assessed as being at low risk of bias for attrition bias. Thirteen studies reported no losses to follow‐up (Borna 2008; Caritis 2009; Combs 2010; Combs 2011a; Facchinetti 2007; Fonseca 2007; Hartikainen 1980; Hauth 1983; Ibrahim 2010; Majhi 2009; Meis 2003; Papiernik 1970; Saghafi 2011a) and 18 studies reported less than 20% loss to follow‐up (Aboulghar 2012; Briery 2011; Cetingoz 2011; Combs 2011; da Fonseca 2003; Glover 2011; Grobman 2012; Hassan 2011; Johnson 1975; Lim 2011; Norman 2009; O'Brien 2007; Rai 2009; Rode 2011; Rouse 2007; Rozenberg 2012; Serra 2013; Sharami 2010). In five studies reported only in abstract form, it was unclear whether attrition bias was present (Elsheikhah 2010; Grobman 2012; Moghtadaei 2008; Ndoni 2010; Senat 2012) and in one study details were insufficient to make a judgement (Akbari 2009).

Selective reporting

Twenty‐five studies were assessed as being at low risk of bias for selective reporting (Aboulghar 2012; Akbari 2009; Borna 2008; Caritis 2009; Cetingoz 2011; Combs 2010; Combs 2011; Combs 2011a; da Fonseca 2003; Fonseca 2007; Grobman 2012; Hartikainen 1980; Hassan 2011; Hauth 1983; Ibrahim 2010; Johnson 1975; Lim 2011; Majhi 2009; Meis 2003; Norman 2009; O'Brien 2007; Rai 2009; Rode 2011; Rouse 2007; Rozenberg 2012) as all expected outcomes were reported. One study was assessed as being at high risk of bias, because one of the outcomes was incompletely reported on (Facchinetti 2007) and in one study it was difficult to assess selective reporting based on a translation of the original report (Papiernik 1970). In all the other study reports, it was not possible to determine whether or not selection bias was present (Briery 2011; Elsheikhah 2010; Glover 2011; Moghtadaei 2008; Ndoni 2010; Rozenberg 2012; Saghafi 2011a; Senat 2012; Serra 2013; Sharami 2010).

Other potential sources of bias

Twenty‐one studies were assessed as being at low risk of bias for other potential sources of bias based on baseline characteristics being similar between groups and no other bias apparent (Borna 2008; Briery 2011; Caritis 2009; Combs 2010; Combs 2011; da Fonseca 2003; Facchinetti 2007; Fonseca 2007; Glover 2011; Hassan 2011; Hauth 1983; Johnson 1975; Lim 2011; Meis 2003; Norman 2009; O'Brien 2007; Papiernik 1970; Rai 2009; Rode 2011; Saghafi 2011a; Sharami 2010). In the remaining studies, it was not possible to determine whether or not other sources of bias were present (Aboulghar 2012; Akbari 2009; Cetingoz 2011; Combs 2011a; Elsheikhah 2010; Grobman 2012; Hartikainen 1980; Ibrahim 2010; Majhi 2009; Moghtadaei 2008; Ndoni 2010; Rouse 2007; Rozenberg 2012; Senat 2012; Serra 2013).

Assessment of studies that included multiple pregnancies

We assessed whether studies that included multiple pregnancies accounted appropriately for non‐independence of babies from the same pregnancy in the analysis. There were 14 studies that included a multiple pregnancy (Aboulghar 2012; Caritis 2009; Cetingoz 2011; Combs 2010; Combs 2011; Elsheikhah 2010; Fonseca 2007; Hartikainen 1980; Lim 2011; Norman 2009; Rode 2011; Rouse 2007; Senat 2012; Serra 2013) and in seven studies adjustment appears to have been made in the analysis (Caritis 2009; Combs 2010; Combs 2011; Fonseca 2007; Lim 2011; Norman 2009; Rode 2011). In the remaining seven studies (Aboulghar 2012; Cetingoz 2011; Elsheikhah 2010; Hartikainen 1980; Rouse 2007; Senat 2012; Serra 2013), it is not clear that any adjustment was made.

There were insufficient data presented in the trial reports to allow us to carry out necessary adjustment for cluster design effect ourselves and, although in several trials results had already been adjusted, we were not able to present these data in our data and analyses tables because they were not reported in a consistent way.

Effects of interventions

Thirty‐six randomised controlled trials (8523 women and 12,515 infants) in total were included in this review.

Data were only available in a suitable format from 30 randomised controlled trials involving a total of 7561 women and 10,114 infants. Data from these 30 trials contributed data that were included in meta‐analyses. As the aetiology of preterm birth is multifactorial, results are presented according to the reason considered to be at risk for preterm birth (past history of spontaneous preterm birth (including preterm premature rupture of membranes), ultrasound identified short cervical length, multiple pregnancy, prior presentation with threatened preterm labour, and other reason for risk of preterm birth).

Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment for women with a past history of spontaneous preterm birth

Eleven randomised controlled trials involving a total of 1899 women and infants were included in the meta‐analysis.

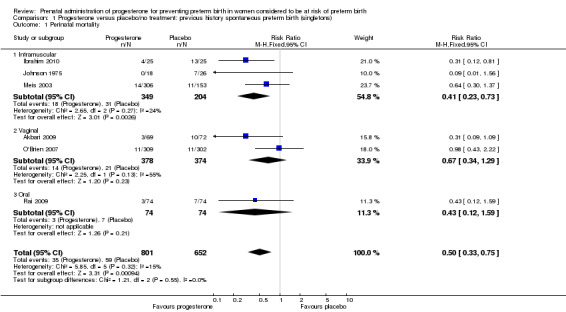

Primary outcomes

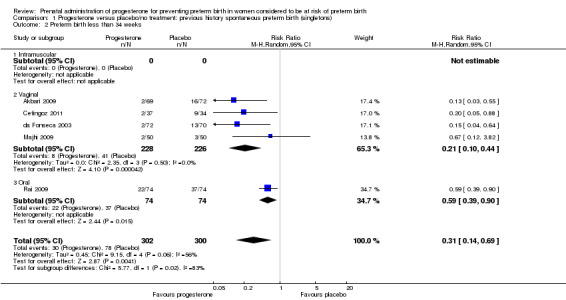

For women administered progesterone during pregnancy, there was a statistically significant reduction in perinatal mortality overall (six studies; 1453 women; risk ratio (RR) 0.50, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.33 to 0.75), Analysis 1.1. For the primary outcome preterm birth less than 34 weeks' gestation, there was also a statistically significant difference between progesterone when compared with placebo (five studies; 602 women; average RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.69), Analysis 1.2. Substantial heterogeneity was evident for Analysis 1.2 (heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.45, Chi² = 9.15, df = 4 (P = 0.06), I² = 56%) and so a random‐effects model was used. Major neurodevelopmental handicap in childhood was not reported.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 1 Perinatal mortality.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 2 Preterm birth less than 34 weeks.

Secondary infant outcomes

For women administered progesterone during pregnancy, when compared with placebo, the results showed:

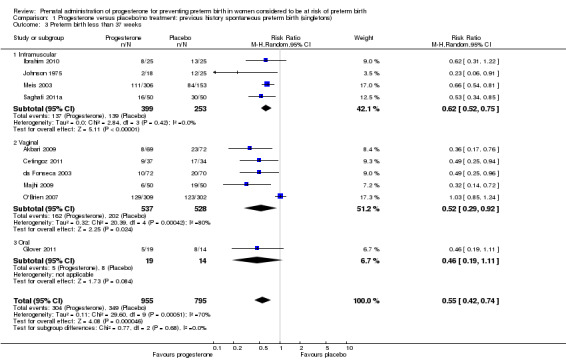

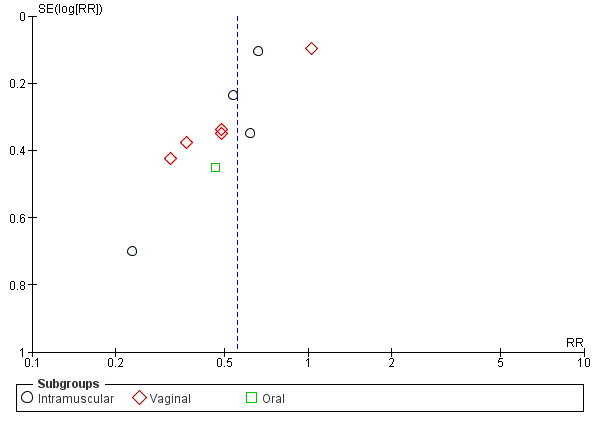

preterm birth less than 37 weeks' gestation (10 studies; 1750 women; average RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.74); considerable heterogeneity was identified, and a random‐effects model was used (heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.11; Chi² = 29.60, df = 9 (P = 0.0005); I² = 70%), Analysis 1.3. This was also evident for the intramuscular subgroup (four studies; 652 women; average RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.75), Analysis 1.3.1. However, for the oral subgroup, no statistically significant differences were observed, Analysis 1.3.3. A funnel plot for this analysis (Figure 3), including the 10 studies was very asymmetrical. This suggests that there may be some important biases or small‐study effects in the set of studies in this analysis and so these results should be viewed with caution.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 3 Preterm birth less than 37 weeks.

3.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth, outcome: 1.3 Preterm birth less than 37 weeks.

There was also a statistically significant reduction in the risk of:

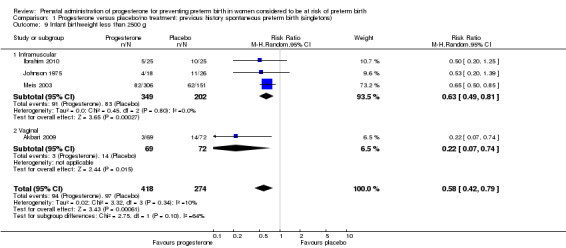

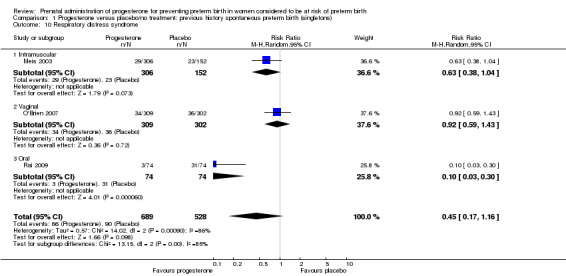

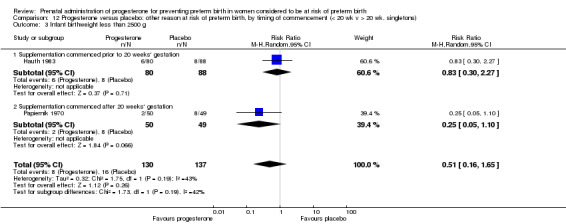

infant birthweight less than 2500 g (four studies; 692 infants; RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.79), Analysis 1.9;

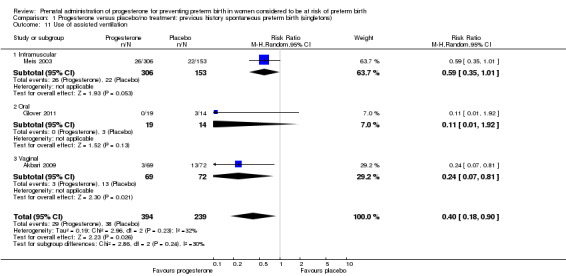

use of assisted ventilation (three studies; 633 women; RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.90), Analysis 1.11;

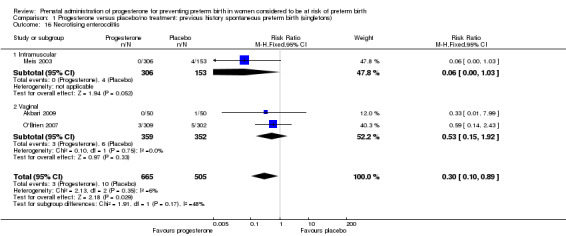

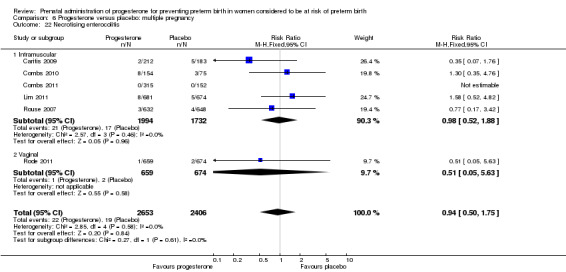

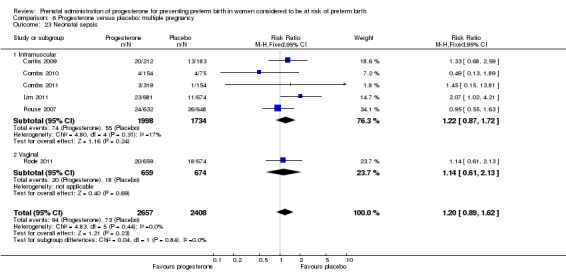

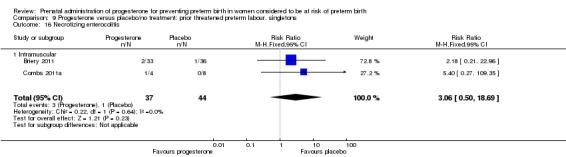

necrotising enterocolitis (three studies; 1170 infants; RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.89), Analysis 1.16;

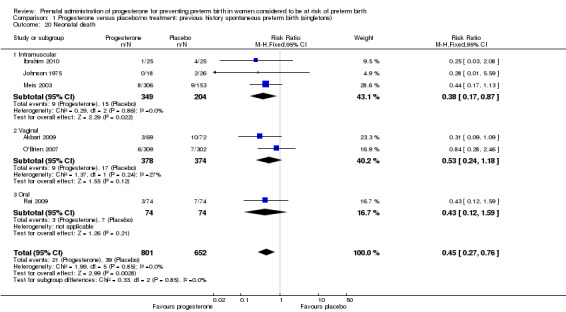

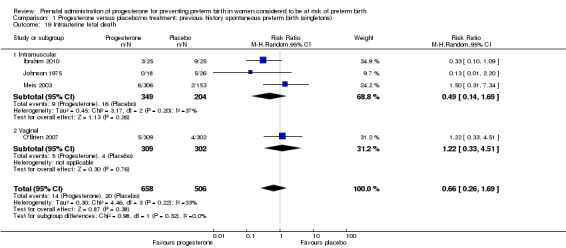

neonatal death (six studies; 1453 women; RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.76), Analysis 1.20;

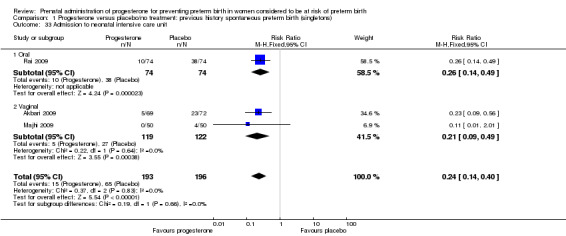

admission to neonatal intensive care unit (three studies; 389 women; RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.40), Analysis 1.33.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 9 Infant birthweight less than 2500 g.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 11 Use of assisted ventilation.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 16 Necrotising enterocolitis.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 20 Neonatal death.

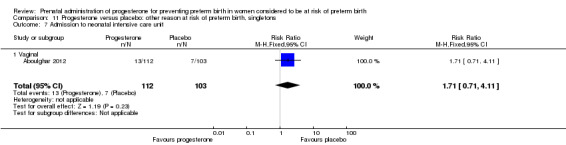

1.33. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 33 Admission to neonatal intensive care unit.

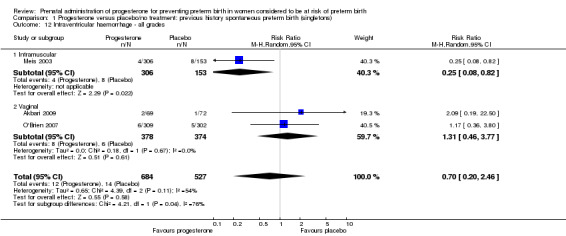

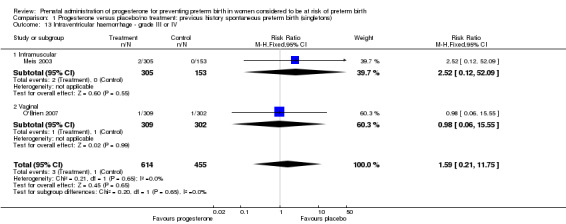

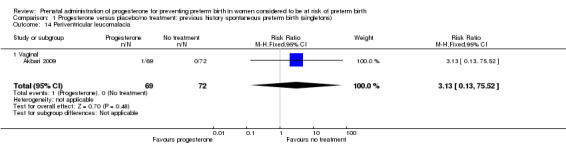

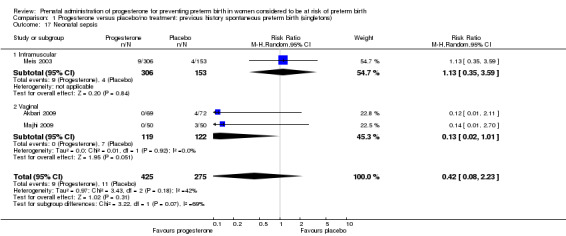

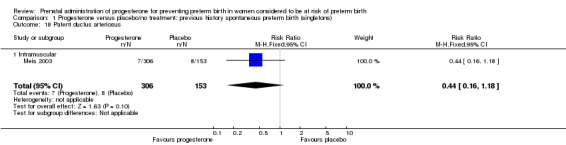

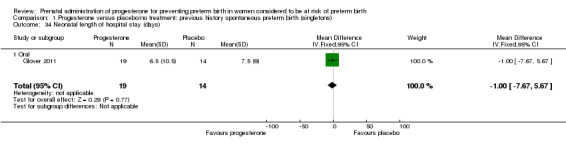

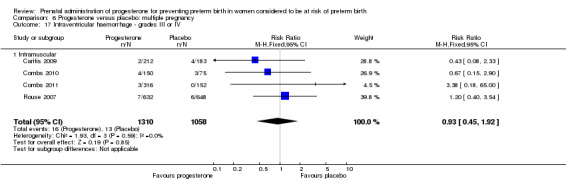

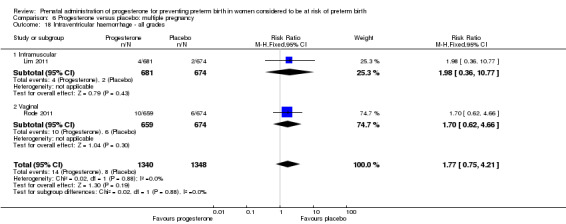

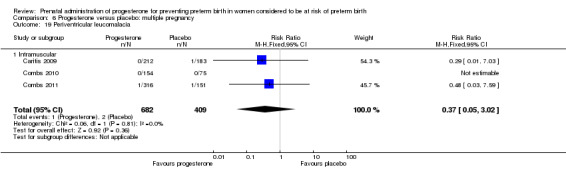

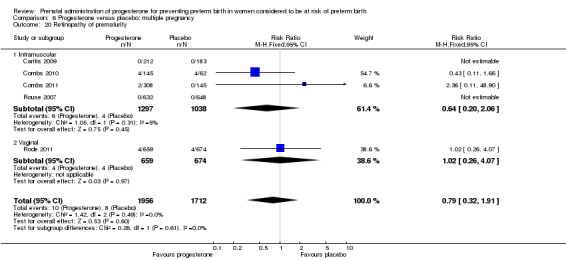

For infant outcomes Apgar score less than seven at five minutes Analysis 1.32, respiratory distress syndrome Analysis 1.10, intrauterine fetal death Analysis 1.19, intraventricular haemorrhage (all grades) Analysis 1.12, intraventricular haemorrhage (grade III or IV) Analysis 1.13, periventricular leucomalacia Analysis 1.14, retinopathy of prematurity Analysis 1.15, neonatal sepsis Analysis 1.17, patent ductus arteriosus Analysis 1.18, intrauterine fetal death Analysis 1.19, or neonatal length of hospital stay Analysis 1.34, there were no statistically significant differences identified.

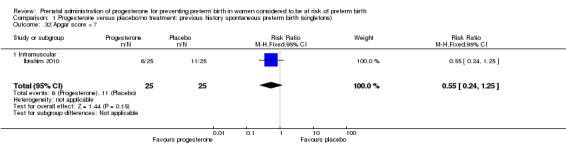

1.32. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 32 Apgar score < 7.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 10 Respiratory distress syndrome.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 19 Intrauterine fetal death.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 12 Intraventricular haemorrhage ‐ all grades.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 13 Intraventricular haemorrhage ‐ grade III or IV.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 14 Periventricular leucomalacia.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 15 Retinopathy of prematurity.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 17 Neonatal sepsis.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 18 Patent ductus arteriosus.

1.34. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 34 Neonatal length of hospital stay (days).

Secondary maternal outcomes

For women administered progesterone during pregnancy, when compared with placebo, there was a statistically significant increase in:

pregnancy prolongation in weeks (one study; 148 women; mean difference (MD) 4.47, 95% CI 2.15 to 6.79), Analysis 1.31.

1.31. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 31 Pregnancy prolongation (weeks).

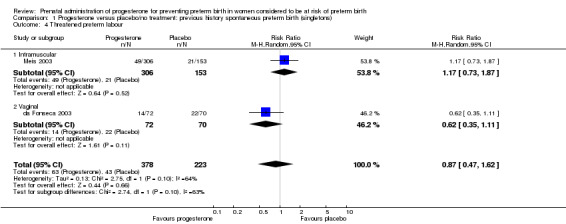

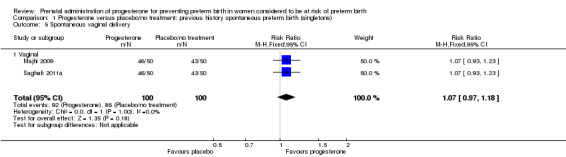

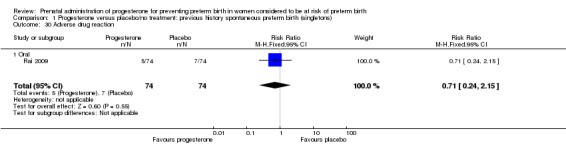

There were no statistically significant differences for the outcomes threatened preterm labour Analysis 1.4, spontaneous vaginal birth Analysis 1.5, adverse drug reaction Analysis 1.30, caesarean birth Analysis 1.6, use of antenatal corticosteroids Analysis 1.7, or the use of antenatal tocolysis Analysis 1.8.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 4 Threatened preterm labour.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 5 Spontaneous vaginal delivery.

1.30. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 30 Adverse drug reaction.

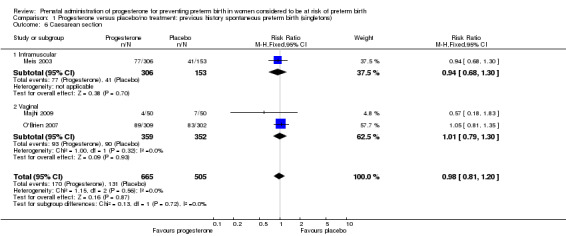

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 6 Caesarean section.

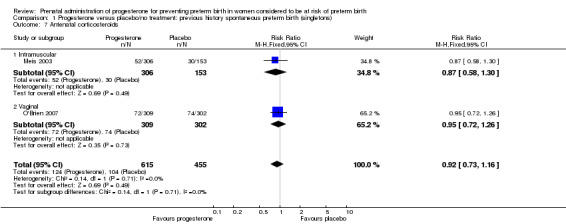

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 7 Antenatal corticosteroids.

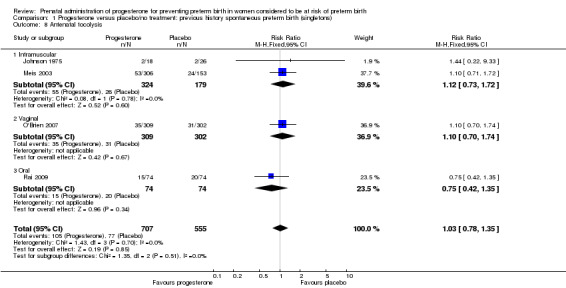

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 8 Antenatal tocolysis.

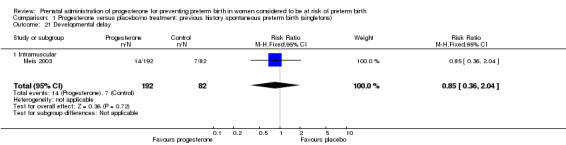

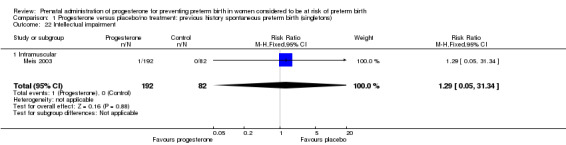

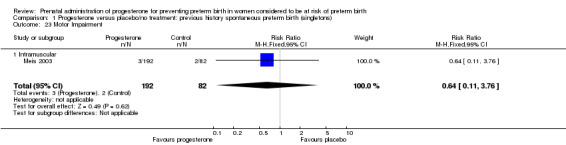

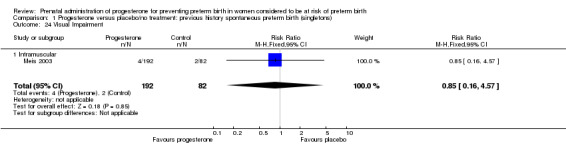

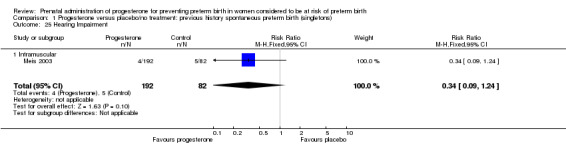

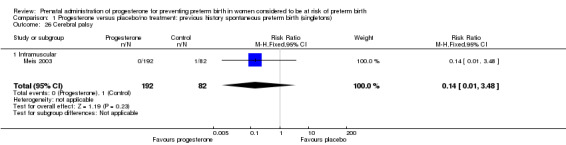

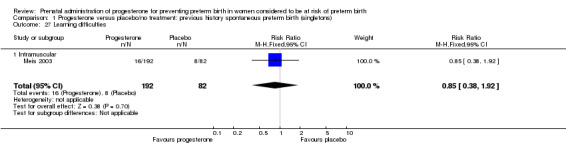

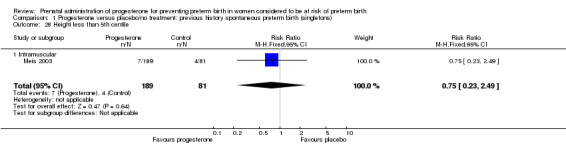

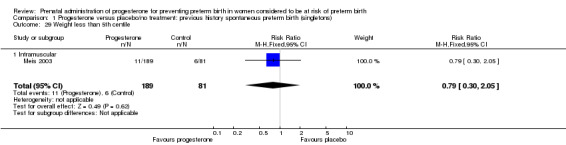

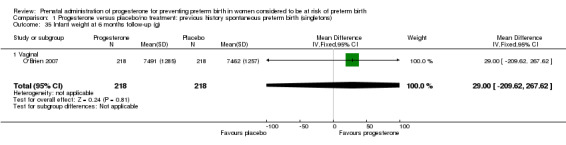

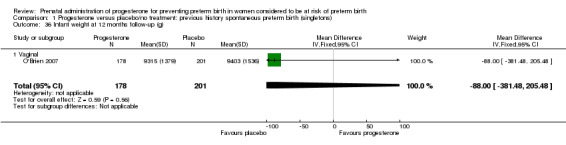

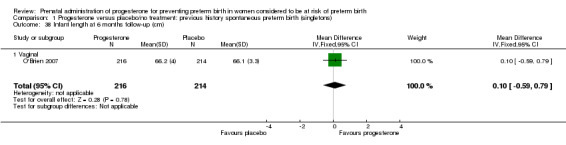

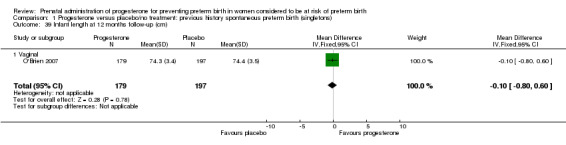

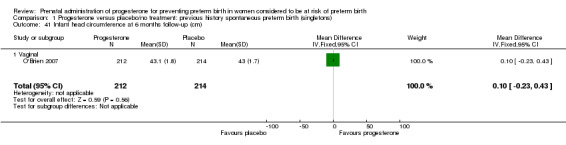

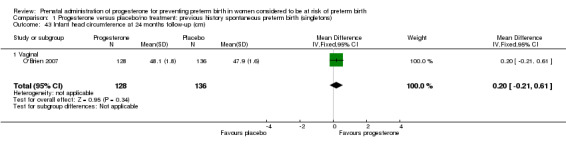

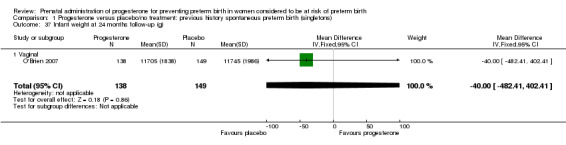

Secondary childhood outcomes

There were no statistically significant differences identified for the outcomes developmental delay Analysis 1.21, intellectual impairment Analysis 1.22, motor impairment Analysis 1.23, visual impairment Analysis 1.24, hearing impairment Analysis 1.25, cerebral palsy Analysis 1.26, learning difficulties Analysis 1.27, height less than fifth centile Analysis 1.28 , weight less than the fifth centile Analysis 1.29, infant weight at six, 12 and 24 months' follow‐up Analysis 1.34; Analysis 1.35; Analysis 1.36, infant length (cm) at six, 12 and 24 months' follow‐up Analysis 1.38; Analysis 1.39; Analysis 1.40, and infant head circumference (cm) at six, 12 and 24 months' follow‐up Analysis 1.41; Analysis 1.42; Analysis 1.43.

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 21 Developmental delay.

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 22 Intellectual impairment.

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 23 Motor Impairment.

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 24 Visual Impairment.

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 25 Hearing Impairment.

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 26 Cerebral palsy.

1.27. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 27 Learning difficulties.

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 28 Height less than 5th centile.

1.29. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 29 Weight less than 5th centile.

1.35. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 35 Infant weight at 6 months follow‐up (g).

1.36. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 36 Infant weight at 12 months follow‐up (g).

1.38. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 38 Infant length at 6 months follow‐up (cm).

1.39. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 39 Infant length at 12 months follow‐up (cm).

1.40. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 40 Infant length at 24 months follow‐up (cm).

1.41. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 41 Infant head circumference at 6 months follow‐up (cm).

1.42. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 42 Infant head circumference at 12 months follow‐up (cm).

1.43. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth (singletons), Outcome 43 Infant head circumference at 24 months follow‐up (cm).

Effect of route of administration, time of commencing therapy, and dose of progesterone

We investigated statistical heterogeneity (I² > 30%) by performing subgroup analyses where possible for all outcomes and found no differential effect on the majority of outcomes examined when considering route of administration of progesterone (intramuscular versus vaginal versus oral). However, for respiratory distress syndrome, the subgroup analysis indicated a differential effect between the different routes of administration (test for subgroup differences: P = 0.001, I² = 84.8%, Analysis 1.10), although only one trial was included in each subgroup of intramuscular versus vaginal versus oral, Analysis 1.10.

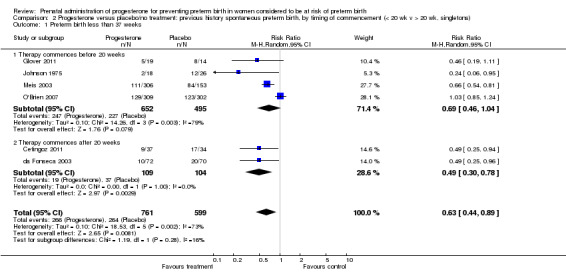

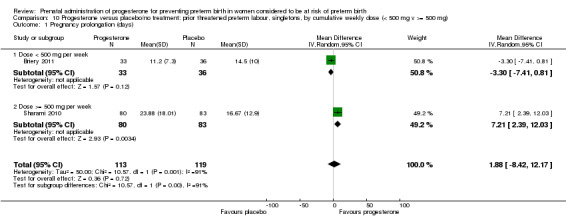

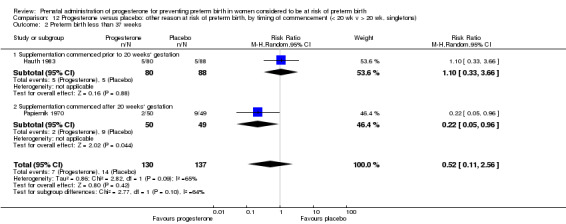

We performed subgroup analysis to investigate the differential effect of time of commencement of supplementation (prior to 20 weeks' gestation versus after 20 weeks' gestation) where outcome data allowed, and found no subgroup differences (test for subgroup differences: P = 0.28, I² = 15.9%, Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth, by timing of commencement (< 20 wk v > 20 wk, singletons), Outcome 1 Preterm birth less than 37 weeks.

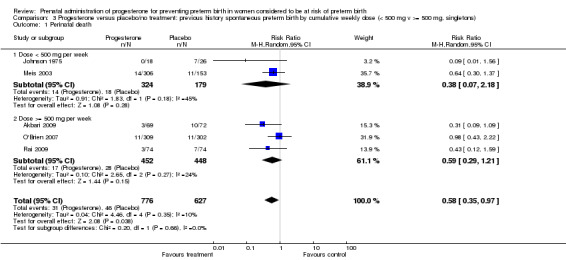

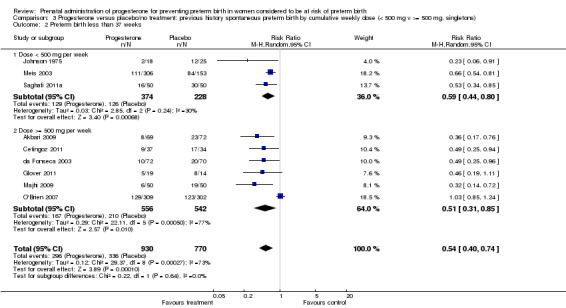

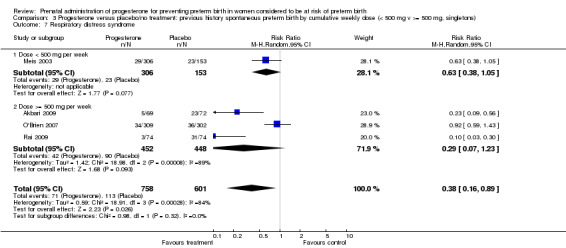

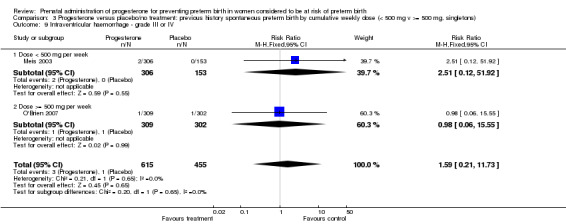

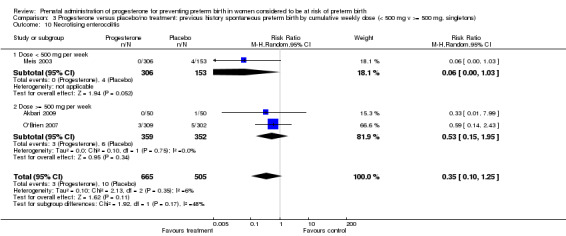

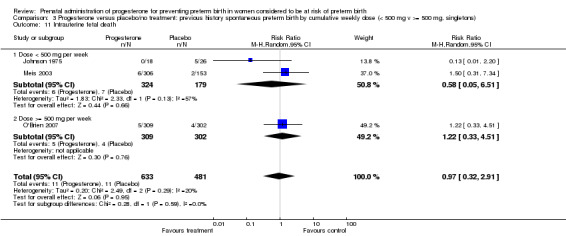

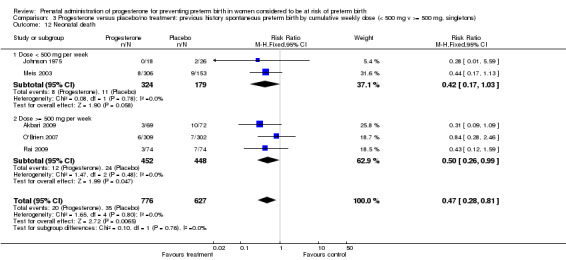

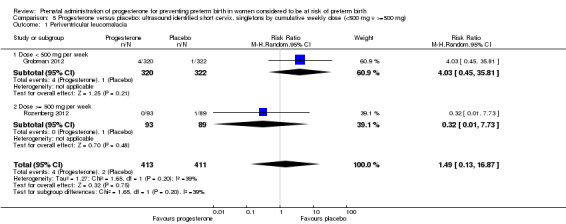

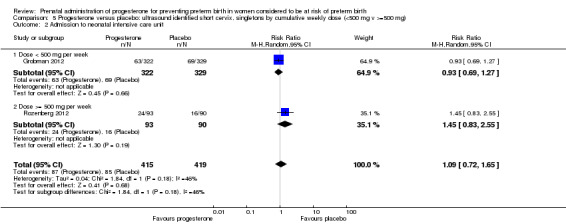

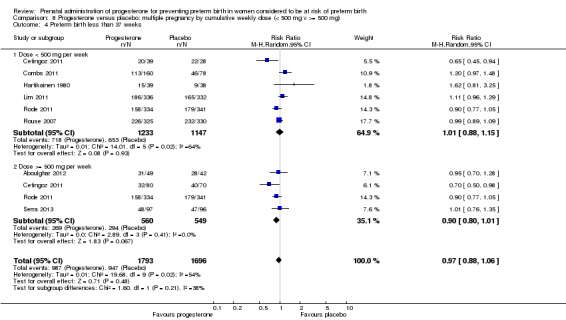

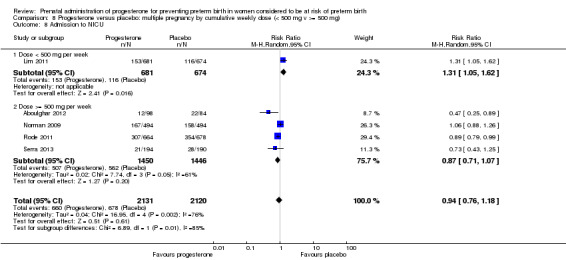

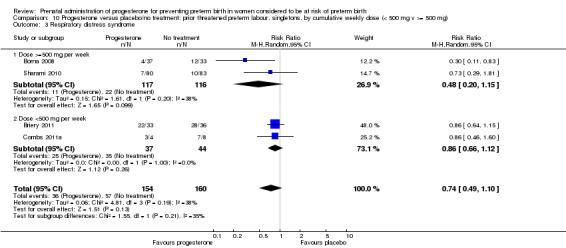

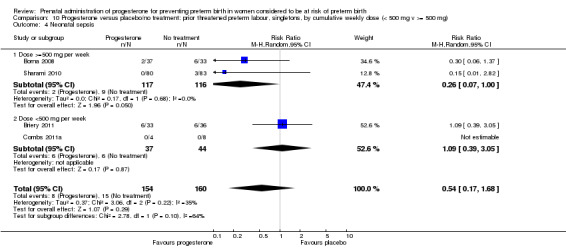

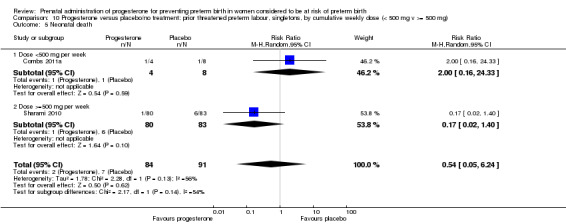

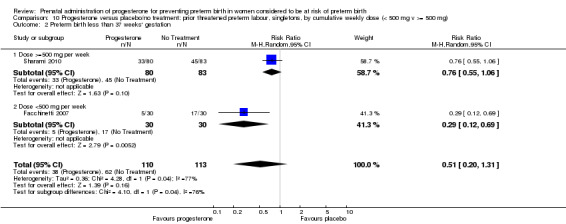

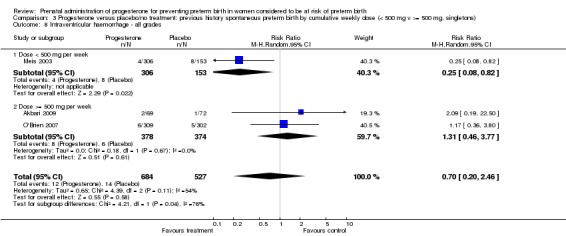

We also performed subgroup analysis by total weekly cumulative dose of progesterone (less than 500 mg versus greater than 500 mg) and found no differential effect for the majority of outcomes examined: Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2; Analysis 3.3; Analysis 3.4; Analysis 3.5; Analysis 3.6; Analysis 3.7; Analysis 3.9; Analysis 3.10; Analysis 3.11; Analysis 3.12. However, for intraventricular haemorrhage (all grades), the subgroup analysis indicated a differential effect between the different doses of progesterone (test for subgroup differences: P = 0.04, I² = 76.2%, Analysis 1.38), although only one trial was included in each subgroup of intramuscular versus vaginal versus oral, Analysis 1.10.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth by cumulative weekly dose (< 500 mg v >= 500 mg, singletons), Outcome 1 Perinatal death.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth by cumulative weekly dose (< 500 mg v >= 500 mg, singletons), Outcome 2 Preterm birth less than 37 weeks.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth by cumulative weekly dose (< 500 mg v >= 500 mg, singletons), Outcome 3 Threatened preterm labour.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth by cumulative weekly dose (< 500 mg v >= 500 mg, singletons), Outcome 4 Caesarean section.

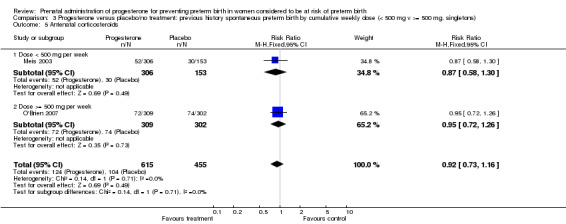

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth by cumulative weekly dose (< 500 mg v >= 500 mg, singletons), Outcome 5 Antenatal corticosteroids.

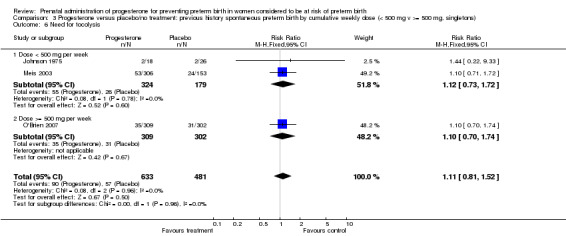

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth by cumulative weekly dose (< 500 mg v >= 500 mg, singletons), Outcome 6 Need for tocolysis.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth by cumulative weekly dose (< 500 mg v >= 500 mg, singletons), Outcome 7 Respiratory distress syndrome.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth by cumulative weekly dose (< 500 mg v >= 500 mg, singletons), Outcome 9 Intraventricular haemorrhage ‐ grade III or IV.

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth by cumulative weekly dose (< 500 mg v >= 500 mg, singletons), Outcome 10 Necrotising enterocolitis.

3.11. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth by cumulative weekly dose (< 500 mg v >= 500 mg, singletons), Outcome 11 Intrauterine fetal death.

3.12. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Progesterone versus placebo/no treatment: previous history spontaneous preterm birth by cumulative weekly dose (< 500 mg v >= 500 mg, singletons), Outcome 12 Neonatal death.

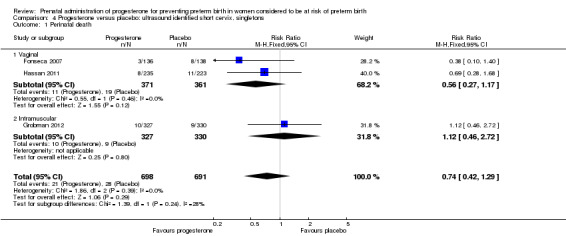

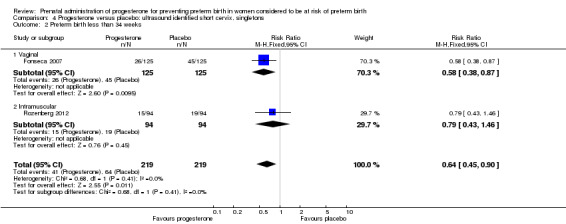

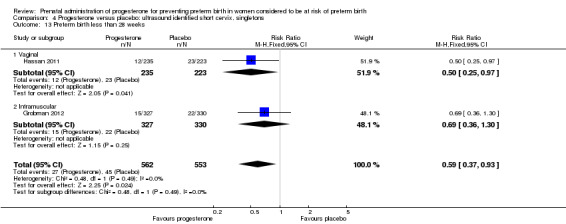

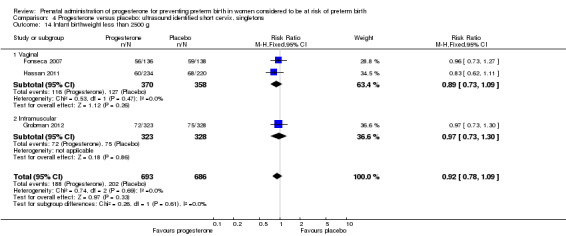

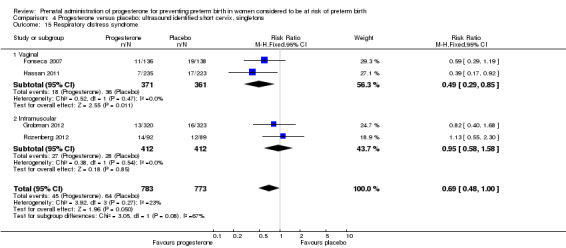

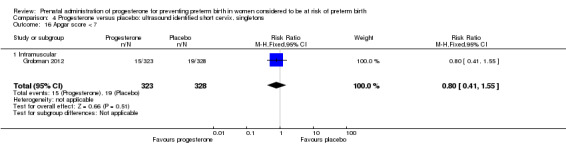

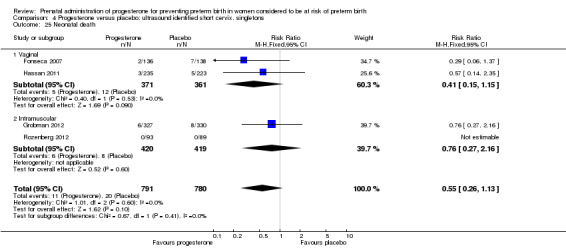

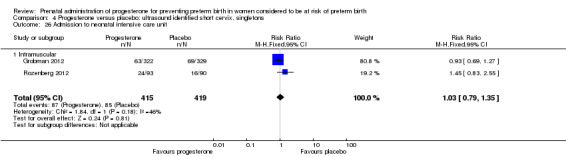

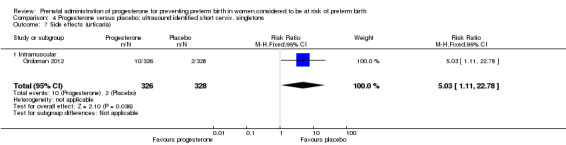

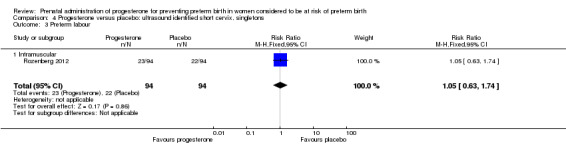

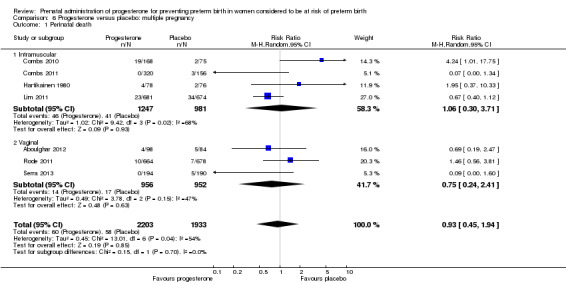

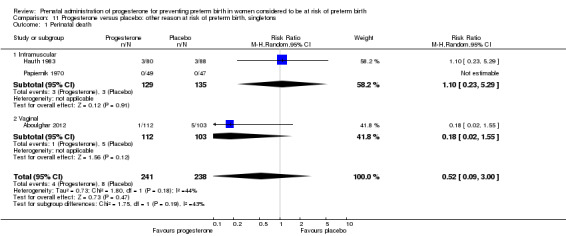

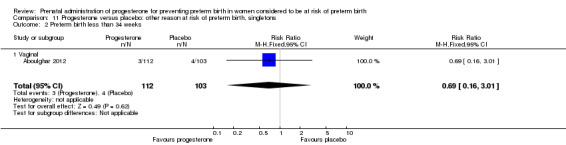

Progesterone versus placebo for women with a short cervix identified on ultrasound

Four randomised controlled trials involving a total of 1556 women and infants were included in the meta‐analysis.

Primary outcomes

For women administered progesterone during pregnancy, for the primary outcome perinatal death, there were no statistically significant differences identified when compared with placebo, Analysis 4.1. Women administered progesterone were significantly less likely to have a preterm birth at less than 34 weeks' gestation (two studies; 438 women; RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.90), Analysis 4.2. Major neurodevelopmental handicap in childhood was not reported.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 1 Perinatal death.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 2 Preterm birth less than 34 weeks.

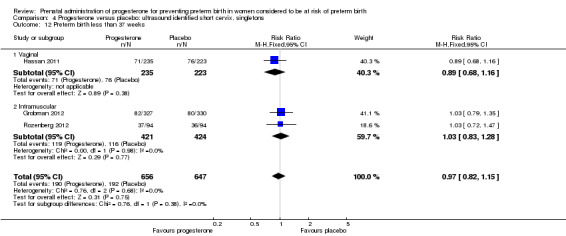

Secondary infant outcomes

For women administered progesterone during pregnancy, for the outcome preterm birth at less than 37 weeks' gestation, there were no statistically significant differences identified when compared with placebo, Analysis 4.12. However, women administered progesterone were significantly less likely to have a preterm birth at less than 28 weeks' gestation (two studies; 1115 women; RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.93), Analysis 4.13.

4.12. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 12 Preterm birth less than 37 weeks.

4.13. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 13 Preterm birth less than 28 weeks.

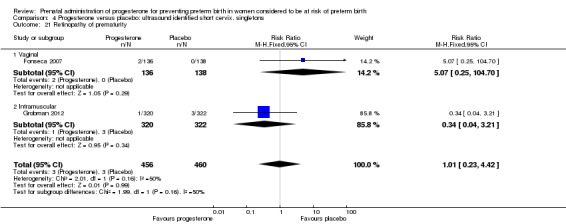

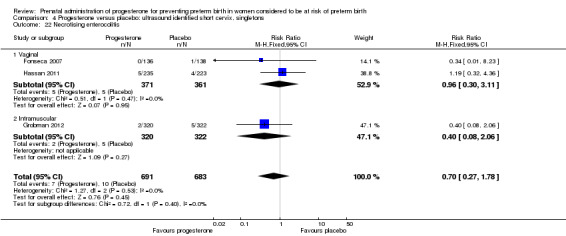

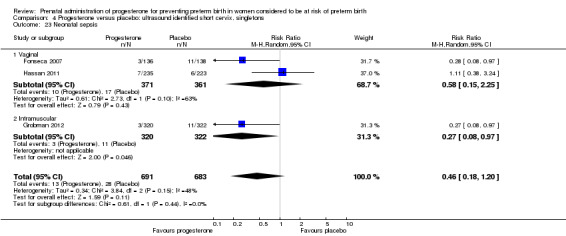

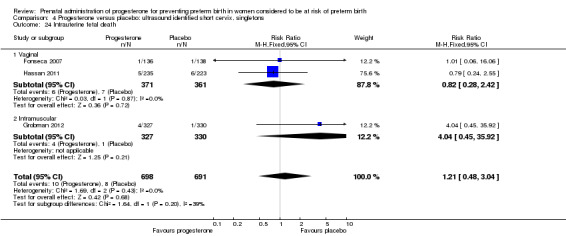

For infant outcomes infant birthweight less than 2500 g Analysis 4.14, respiratory distress syndrome Analysis 4.15, Apgar score less than seven at five minutes Analysis 4.16, need for assisted ventilation Analysis 4.17, intraventricular haemorrhage (all grades) Analysis 4.18, intraventricular haemorrhage (grades III or IV) Analysis 4.19, periventricular leucomalacia Analysis 4.20, retinopathy of prematurity Analysis 4.21, necrotising enterocolitis Analysis 4.22, neonatal sepsis Analysis 4.23, intrauterine fetal death Analysis 4.24, neonatal death Analysis 4.25 or admission to neonatal intensive care unit Analysis 4.26, there were no statistically significant differences identified.

4.14. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 14 Infant birthweight less than 2500 g.

4.15. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 15 Respiratory distress syndrome.

4.16. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 16 Apgar score < 7.

4.17. Analysis.

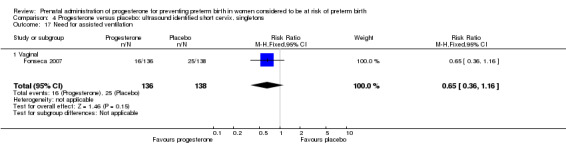

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 17 Need for assisted ventilation.

4.18. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 18 Intraventricular haemorrhage ‐ all grades.

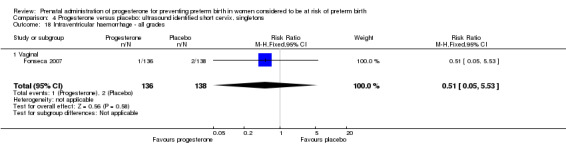

4.19. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 19 Intraventricular haemorrhage ‐ grades III or IV.

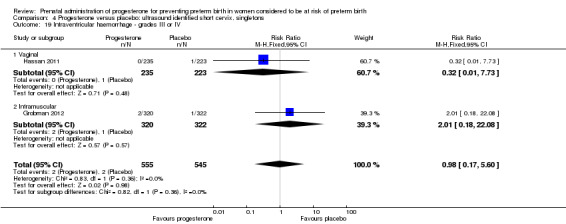

4.20. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 20 Periventricular leucomalacia.

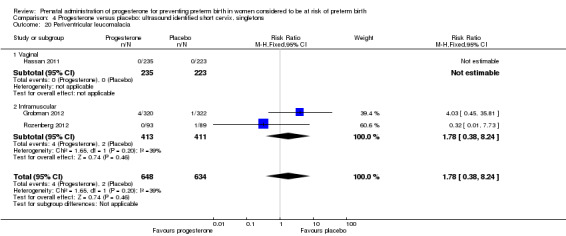

4.21. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 21 Retinopathy of prematurity.

4.22. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 22 Necrotising enterocolitis.

4.23. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 23 Neonatal sepsis.

4.24. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 24 Intrauterine fetal death.

4.25. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 25 Neonatal death.

4.26. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 26 Admission to neonatal intensive care unit.

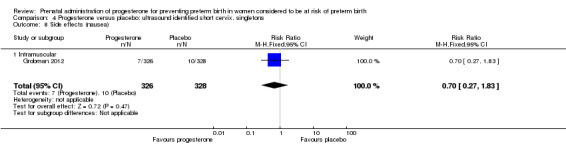

Secondary maternal outcomes

Women administered progesterone were significantly more likely to experience the adverse drug reaction urticaria (one study; 654 women; RR 5.03, 95% CI 1.11 to 22.78), Analysis 4.7. For all other maternal outcomes, threatened preterm labour Analysis 4.3, prelabour spontaneous rupture of membranes Analysis 4.4, adverse drug reactions (any, injection site, nausea) Analysis 4.5; Analysis 4.6; Analysis 4.8, pregnancy prolongation Analysis 4.9, caesarean section Analysis 4.10, or antenatal tocolysis Analysis 4.11, there were no statistically significant differences identified.

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 7 Side effects (urticaria).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 3 Preterm labour.

4.4. Analysis.

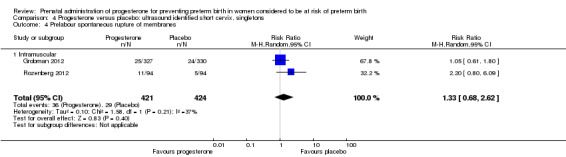

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 4 Prelabour spontaneous rupture of membranes.

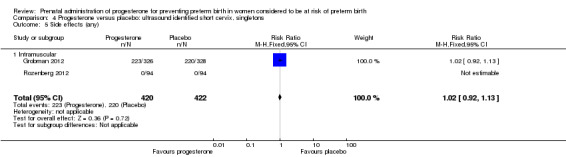

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 5 Side effects (any).

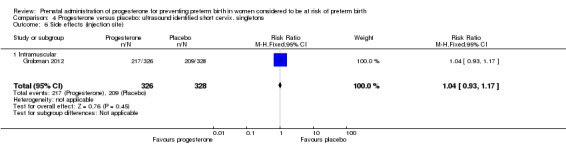

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 6 Side effects (injection site).

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 8 Side effects (nausea).

4.9. Analysis.

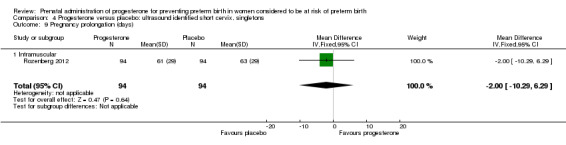

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 9 Pregnancy prolongation (days).

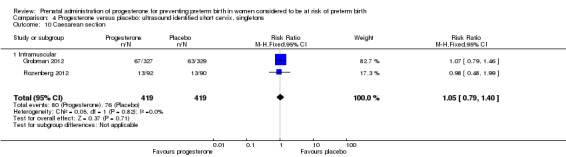

4.10. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 10 Caesarean section.

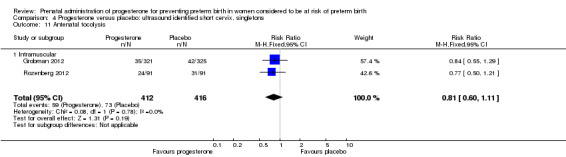

4.11. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Progesterone versus placebo: ultrasound identified short cervix, singletons, Outcome 11 Antenatal tocolysis.

Secondary childhood outcomes

None of the secondary childhood outcomes were reported.

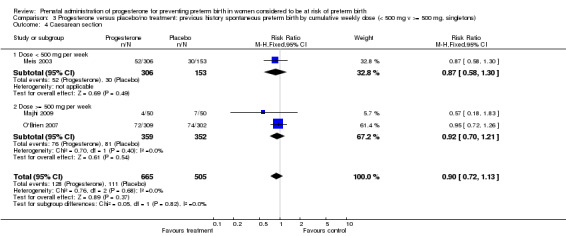

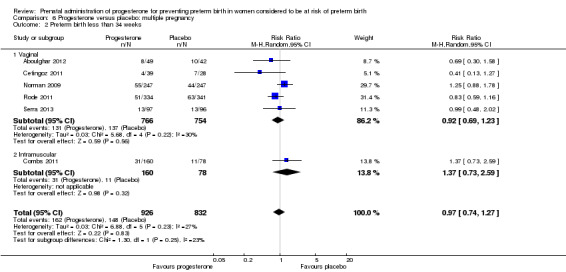

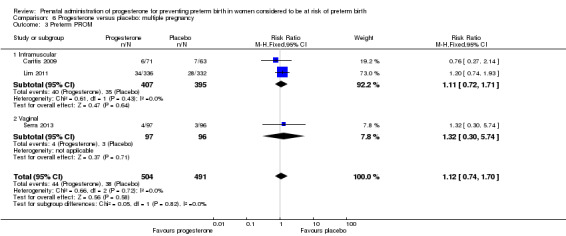

Effect of route of administration, time of commencing therapy, and dose of progesterone

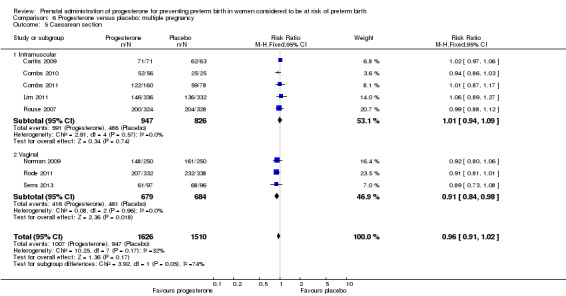

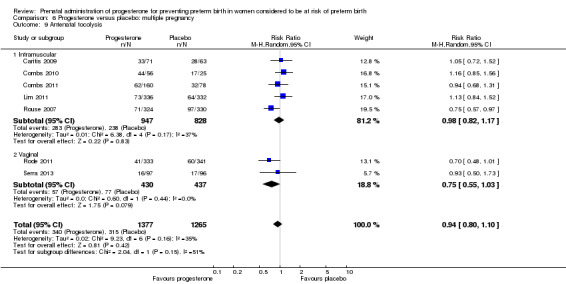

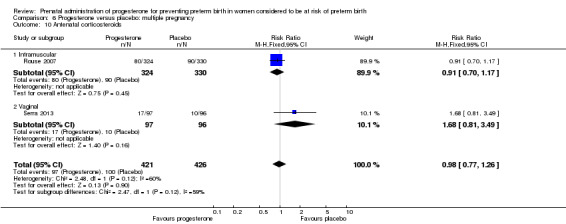

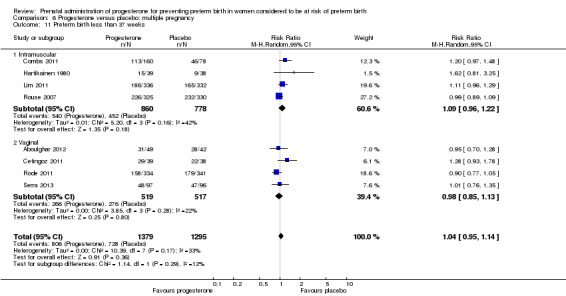

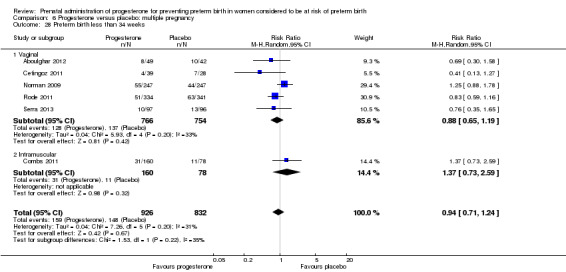

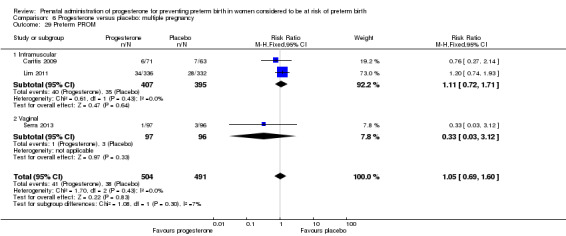

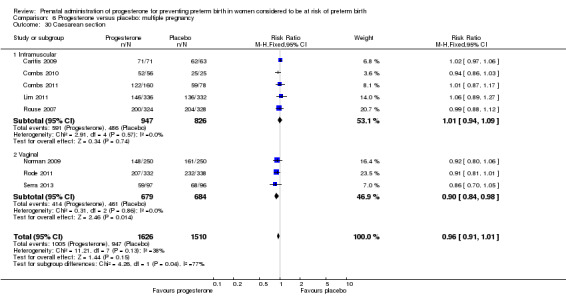

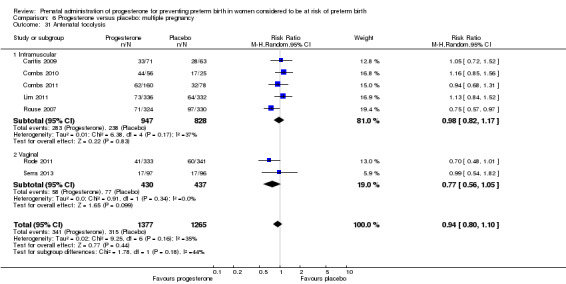

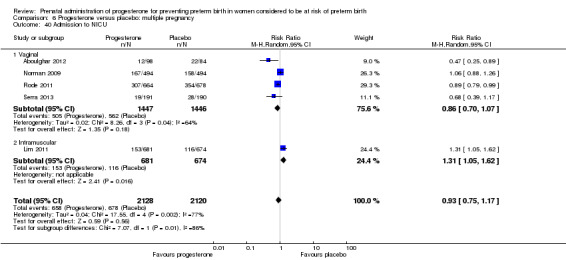

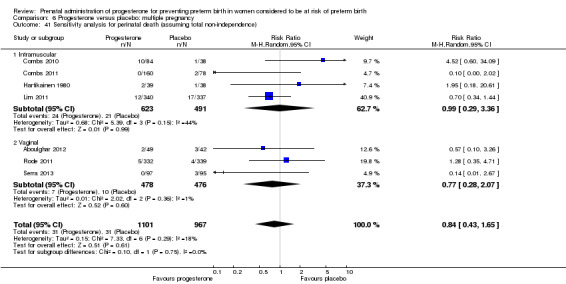

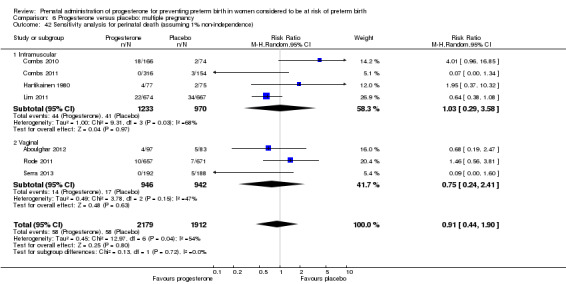

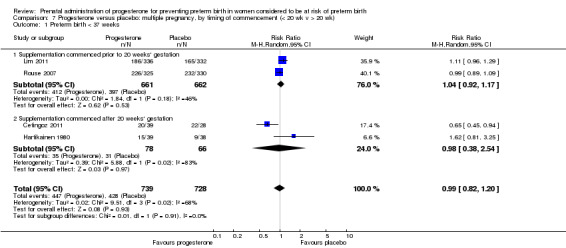

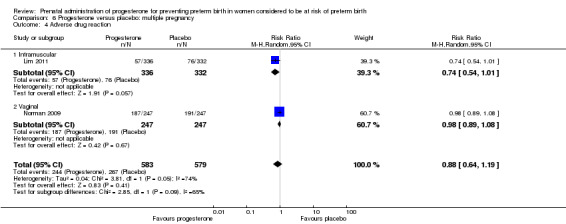

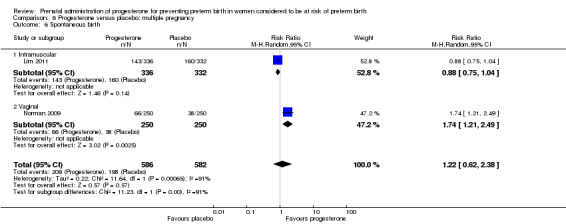

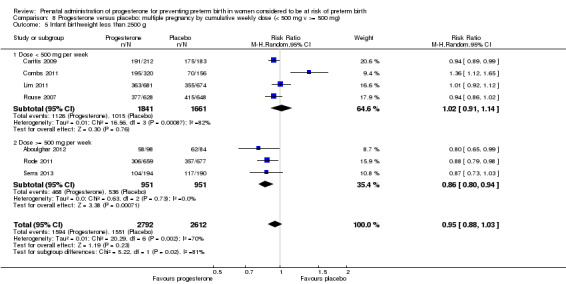

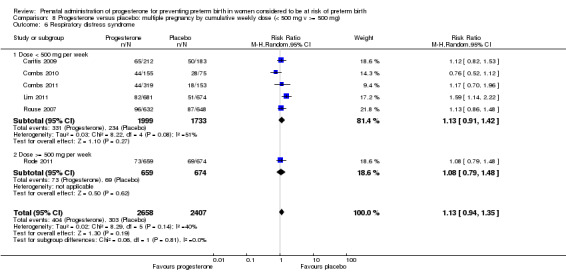

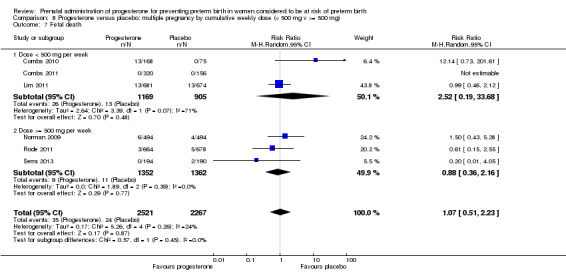

We investigated statistical heterogeneity (I² > 30%) by performing subgroup analyses where possible for all outcomes and found no differential effect on the outcomes examined when considering route of administration of progesterone (intramuscular versus vaginal), Analysis 4.20; Analysis 4.21; Analysis 4.23. It was not possible to assess the effect of gestational age at commencing therapy.