Abstract

Aims

Pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF) using very high-power short-duration (vHPSD) radiofrequency (RF) ablation proved to be safe and effective. However, vHPSD applications result in shallower lesions that might not be always transmural. Multidetector computed tomography-derived left atrial wall thickness (LAWT) maps could enable a thickness-guided switching from vHPSD to the standard-power ablation mode. The aim of this randomized trial was to compare the safety, the efficacy, and the efficiency of a LAWT-guided vHPSD PVI approach with those of the CLOSE protocol for PAF ablation (NCT04298177).

Methods and results

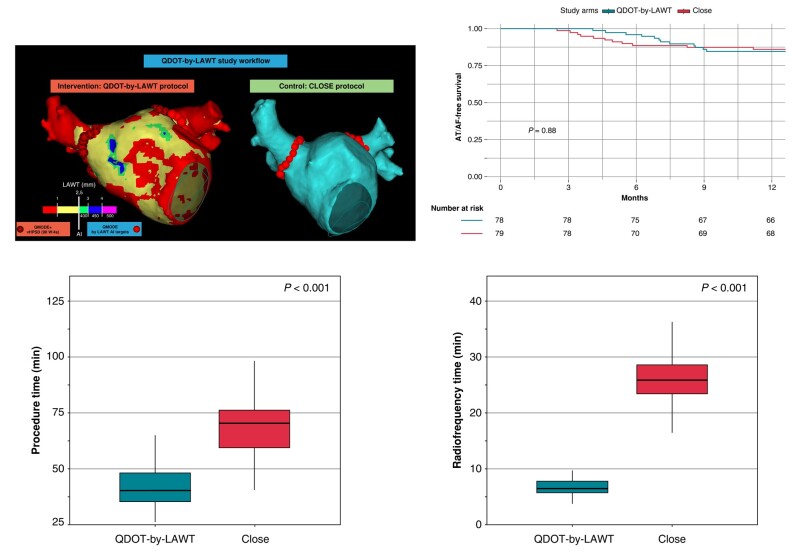

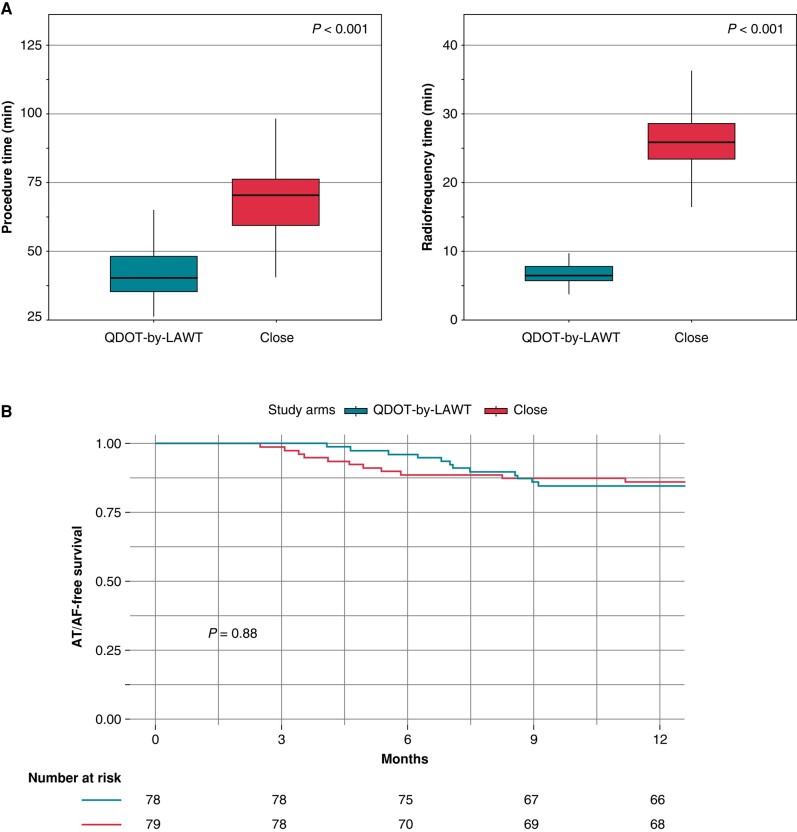

Consecutive patients referred for first-time PAF ablation were randomized on a 1:1 basis. In the QDOT-by-LAWT arm, for LAWT ≤2.5 mm, vHPSD ablation was performed; for points with LAWT > 2.5 mm, standard-power RF ablation titrating ablation index (AI) according to the local LAWT was performed. In the CLOSE arm, LAWT information was not available to the operator; ablation was performed according to the CLOSE study settings: AI ≥400 at the posterior wall and ≥550 at the anterior wall. A total of 162 patients were included. In the QDOT-by-LAWT group, a significant reduction in procedure time (40 vs. 70 min; P < 0.001) and RF time (6.6 vs. 25.7 min; P < 0.001) was observed. No difference was observed between the groups regarding complication rate (P = 0.99) and first-pass isolation (P = 0.99). At 12-month follow-up, no significant differences occurred in atrial arrhythmia-free survival between groups (P = 0.88).

Conclusion

LAWT-guided PVI combining vHPSD and standard-power ablation is not inferior to the CLOSE protocol in terms of 1-year atrial arrhythmia-free survival and demonstrated a reduction in procedural and RF times.

Keywords: Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, Left atrial wall thickness, Catheter ablation, Pulmonary vein isolation, Multidetector cardiac tomography, Very high-power short-duration

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

What’s new?

The QDOT-by-LAWT is the first prospective randomized trial comparing the 1-year outcomes of a very high-power short-duration (vHPSD) ablation protocol with the standard of care. This study is the first reporting the feasibility of a left atrial wall thickness-guided personalized pulmonary vein isolation combining vHPSD and standard-power radiofrequency (RF) lesions for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF) ablation.

The proposed approach permits to alternate in a personalized way between the vHPSD mode and standard power ablation mode, using the first in the areas where the patient’s left atrium is thinner and the second in the thicker areas, permitting to create transmural and durable lesions.

The QDOT-by-LAWT protocol alternating between vHPSD and standard-power ablation modes for PAF ablation is not inferior to the CLOSE protocol in terms of atrial arrhythmia-free survival at 1-year follow-up. This approach demonstrated a relevant reduction in procedural, fluoroscopy, and RF times.

Introduction

Radiofrequency (RF) catheter ablation aiming for pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) is an established strategy for rhythm control in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF).1 Over the years, advances in catheter technologies allowed significant improvements in long-term efficacy outcomes, procedural safety, and efficiency. The ablation index (AI), incorporating contact force (CF), RF duration, and power delivery, demonstrated to accurately predict the depth of the ablation lesions and therefore has been proposed as a novel marker of ablation lesion quality.2 Previous analysis also identified that minimum AI values of 540 at the anterior/superior and 380 at the posterior/inferior segments of pulmonary vein (PV) antrum were predictive of freedom from acute reconnection.3 The CLOSE study used an ablation protocol aimed for an inter-lesion distance (ILD) of ≤6 mm, an AI target of 400 at the posterior/inferior wall, and 550 at the anterior/superior wall, demonstrating a very low recurrence rate of atrial tachyarrhythmias at long-term follow-up in a cohort of patients with PAF.4

The QDOT-FAST provided evidence that very high-power short-duration (vHPSD) ablation using a novel catheter with optimized real-time temperature control was both safe and effective, requiring substantially lower procedure, fluoroscopy, and RF time than the historical standard ablation cohort that utilized point-by-point CF-sensing catheters.5 However, Bourier et al.6 reported that high-power (>50 W) and short-duration RF applications resulted in shallower lesions compared with conventional standard-power ablation, by increasing resistive and reducing conductive heating. Additionally, an experimental model showed that the mean lesion depth achieved with vHPSD (90 W/4 s) RF applications was 3.53 ± 0.6 mm.7 A recent study reported that the left atrial wall thickness (LAWT) of PV antrum in patients with PAF ranges from 0.3 to 4.5 mm;8 therefore, a PVI protocol aimed for only vHPSD lesions may be insufficient to achieve transmural lesions in all PV antrum segments.

In the last few years, the use of pre-procedural cardiac imaging is increasingly supported by scientific evidence for accurate diagnostic classification, prognostic stratification, and peri-procedural support for the ablation of arrhythmias.9–13 It has been recently shown that pre-procedural multidetector computed tomography (MDCT)-derived images can be used to obtain 3D LAWT maps.8,14 Integrating these LAWT maps into the navigation system provides a real-time knowledge of the local LAWT in contact with the ablation catheter tip during the ablation.8 It could permit a LAWT-guided ablation strategy that alternates between the vHPSD mode and the standard-power ablation mode, potentially leading to improved lesion transmurality and enhanced PVI durability.

Currently, there are no randomized trials comparing the 1-year outcomes of vHPSD ablation with the standard CLOSE protocol.

The present study aims to compare the 12-month efficacy, safety, and efficiency outcomes of a LAWT-guided personalized PVI approach using a multichannel RF generator with a vHPSD ablation mode to those of a standard CLOSE protocol PVI strategy for PAF ablation.

Methods

Patient sample

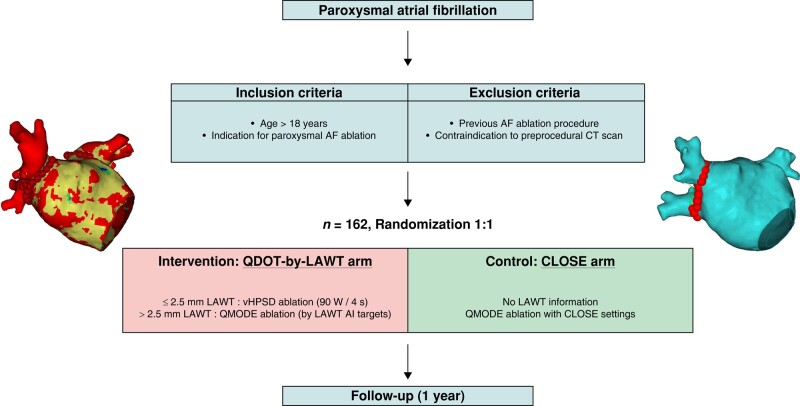

We conducted a single-centre, two-arm, parallel-group, single-blind, non-inferiority, prospective, randomized controlled trial (NCT04298177). Consecutive patients who underwent first-time PAF ablation were prospectively enrolled between March 2022 and January 2023. All patients had documented symptomatic PAF, non-response or intolerance to ≥1 antiarrhythmic drug (Class I or III), and indication for ablation in accordance with ESC guidelines.1 In all patients, an MDCT study was obtained prior to the ablation procedure; post-processing aimed for the reconstruction of MDCT-derived 3D maps with LAWT information was performed, as previously described.14 The exclusion criteria were age <18 years, previous atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation procedure, impossibility to obtain a pre-procedural MDCT, any clinical condition contraindicating general anaesthesia or high-frequency low-tidal volume (HFLTV) ventilation, and inability to provide a signed informed consent. All patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were consecutively enrolled and randomized to either the study arm (‘QDOT-by-LAWT’) or the control arm (‘CLOSE’) in a 1:1 fashion (Figure 1). For participant allocation, a computer-generated list of random numbers was used. A randomization sequence was created using Excel 2020 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) with a 1:1 allocation ratio. The participants were blinded to their assigned randomization group. The electrophysiologists performing the ablation were not blinded due to the technical differences between the two approaches.

Figure 1.

QDOT-by-LAWT randomized trial flowchart. AF, atrial fibrillation; AI, ablation index; CT, computed tomography; LAWT, left atrial wall thickness.

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Pre-procedural cardiac multidetector computed tomography and image post-processing

A pre-procedural cardiac MDCT was obtained with a Revolution™ CT scanner (General Electric Healthcare). The images were acquired during an inspiratory breath-hold using retrospective electrocardiogram (ECG)-gating technique with tube current modulation set between 50 and 100% of the cardiac cycle. Multidetector computed tomography images were analysed with ADAS 3D™ software (ADAS3D Medical, Barcelona, Spain) to obtain 3D LAWT maps; the 3D LAWT map rendering process was previously described.8,14 Briefly, left atrium (LA) endocardial layer was delineated semi-automatically using a threshold-based segmentation, while the epicardial layer was defined in an automatic way by using an artificial intelligence–based segmentation pipeline integrated into the software, which could be then manually re-adjusted by the user. Finally, LAWT was automatically computed at each point as the distance between each endocardial point and its projection onto the epicardial shell. The resulting 3D LAWT map was then imported into the CARTO navigation system (Biosense Webster Inc., Irvine, CA, USA). LAWT maps were colour-coded as follows: red < 1 mm, 1 mm ≤ yellow < 2.5 mm, 2.5 mm ≤ green < 3 mm, 3 mm ≤ blue < 4 mm, and purple ≥ 4 mm. Data on the high reproducibility agreement of the segmentation method of LAWT maps have been reported previously.15 MATLAB customized software was used for maps analysis and LAWT calculation; the circumference of both left PVs (LPVs) and right PVs (RPVs) antra was divided in an eight-segment model,8 as previously described.

Ablation approaches according to the study arm

The randomization was carried out before the ablation procedure and blinded to the LA anatomy. All procedures were performed using CARTO3 mapping system (Biosense Webster, Johnson & Johnson Medical S.p.A., CA, USA) and carried out under general anaesthesia and adopting an HFLTV ventilation protocol.16,17 Transeptal puncture was guided by transoesophageal echocardiography.18 All procedures were performed with a single-catheter technique19 using an open-irrigated tip CF-sensing ablation catheter with six thermocouples able to record the temperature at the catheter–tissue interface (QDOT Micro, Biosense Webster) and a proprietary RF generator capable of delivering power up to 100 W with a rapid ramp-up time while providing real-time temperature feedback (nGEN RF Generator, Biosense Webster). A fast anatomical map (FAM) of the entire LA anatomy and the PVs was acquired and then merged with the imported MDCT-derived map within the spatial reference coordinates of the CARTO system.

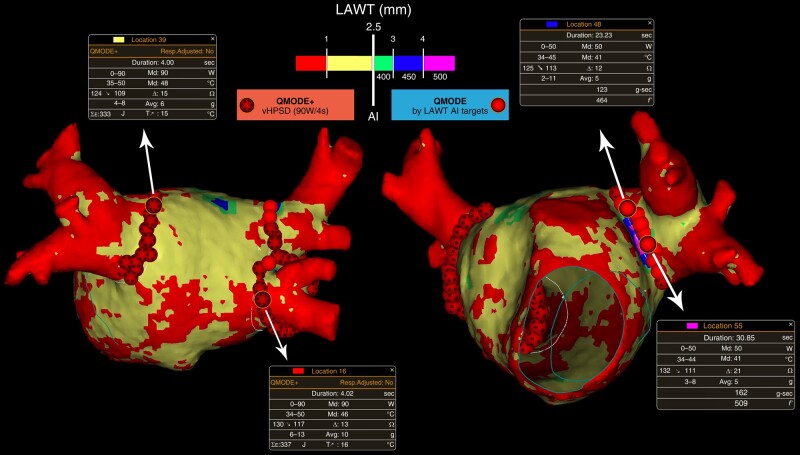

In the ‘QDOT-by-LAWT arm’, PVI was performed following a point-by-point wide antral circumferential ablation (WACA) pattern. A maximal ILD of 6 mm was mandatory for the ablation protocol.20–22 The ablation line was moved inward or outward with respect to the LA–PV junction, aiming to avoid areas with thicker LAWT to perform ablation. For local LAWT ≤2.5 mm (red and yellow colours), vHPSD ablation was performed according to the QDOT-FAST protocol5 settings: a power of 90 W over 4 s in temperature-controlled mode (QMODE+), a temperature target at 60°C, a temperature limit at 65°C based on the hottest surface thermocouple, an irrigation rate of 8 mL/min starting 2 s before each application, and CF >5 g. The choice of the 2.5 mm cut-off was based on the lower range of lesion depth obtained with vHPSD applications in an experimental model.7 For local LAWT >2.5 mm (green, blue, and purple colours), standard-power ablation was performed using the following parameters: 50 W at the anterior wall and 40 W at the posterior wall in temperature-/flow-controlled mode (QMODE, an irrigation flow rate of 4–15 mL/min), a temperature limit 45°C, and CF >5 g. Ablation index targets were titrated according to the local thickness of the 3D LAWT map, as previously described;8 briefly, the following AI targets were used: 400 for green zones of LAWT map, 450 for blue zones, and 500 for purple zones. In the ‘CLOSE arm’, the MDCT-derived LAWT information was not available for the operator. PVI was performed following a point-by-point WACA pattern with a maximal ILD of 6 mm and using a temperature-/flow-controlled mode (QMODE, an irrigation flow rate of 4–15 mL/min), a maximum power of 35 W, a temperature limit of 45°C, and CF >5 g. RF delivery aimed for an AI target of ≥400 at the posterior/inferior wall and ≥550 at the anterior/superior wall. The ablation parameters of the study arms are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Ablation parameters of the study arms

| QDOT-by-LAWT arm | CLOSE arm | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAWT (mm) | Colour code | Ablation mode | Ablation index | RF Energy (W) | Ablation mode | Ablation index | RF energy (W) | ||

| Anterior | Posterior | Anterior | Posterior | ||||||

| <1 | Red | vHPSD | – | – | – | Standard-power | 550 | 400 | 35 |

| 1–2.5 | Yellow | vHPSD | – | – | – | Standard-power | 550 | 400 | 35 |

| 2.5–3 | Green | Standard-power | 400 | 50 | 40 | Standard-power | 550 | 400 | 35 |

| 3–4 | Blue | Standard-power | 450 | 50 | 40 | Standard-power | 550 | 400 | 35 |

| >4 | Purple | Standard-power | 500 | 50 | 40 | Standard-power | 550 | 400 | 35 |

LAWT, left atrial wall thickness; RF, radiofrequency; vHPSD, very high-power short-duration.

For both ablation arms, acute PVI was confirmed by demonstrating bidirectional block: entry block was demonstrated by the absence of PV potentials inside the vein with the ablation catheter placed sequentially in each segment inside the circumferential PV line and exit block by proving the absence of electric capture of the atrium during high-output pacing (10 mA at 2 ms) from inside the circumferential ablation line at multiple locations.19 Additional ‘touch-up’ applications were delivered at the earliest local electrogram in the case of non-first-pass isolation or acute PV reconnection until PVI was achieved. The procedure was not terminated until confirming the absence of visual gaps between VisiTags.

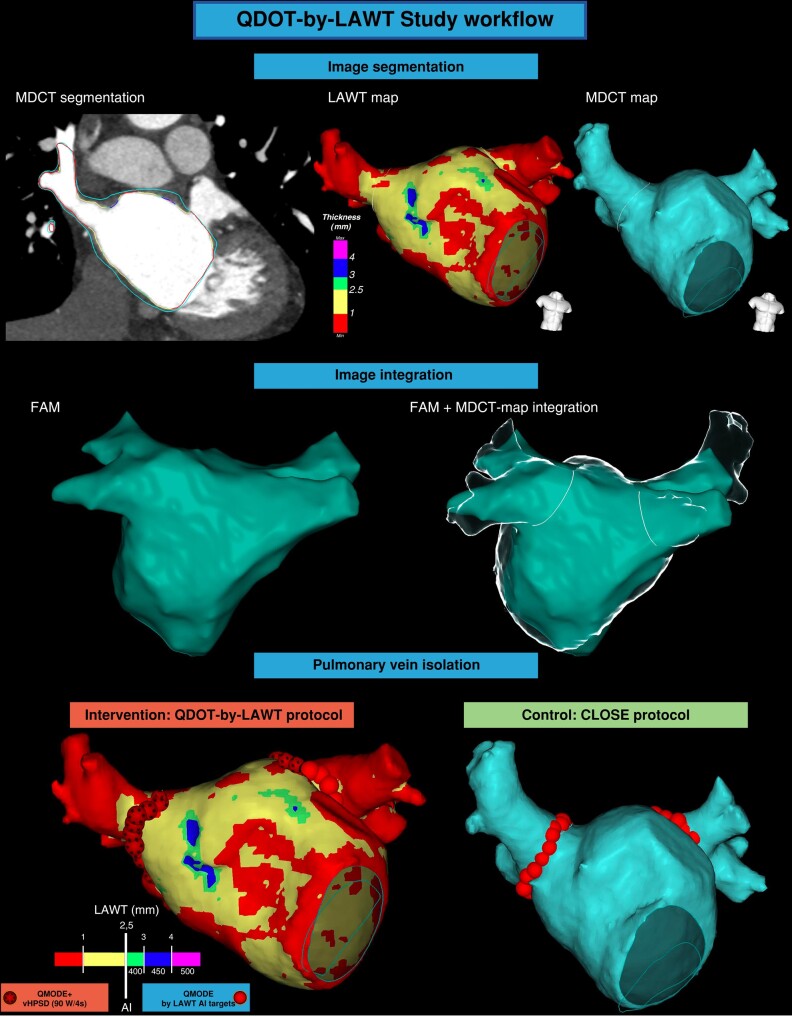

The study workflow and the personalized PVI with LAWT-guided vHPSD lesions are represented in Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

Figure 2.

QDOT-by-LAWT study workflow. The first step is the MDCT-derived image segmentation and the rendering of 3D colour-coded LAWT map (QDOT-by-LAWT arm) or 3D LA anatomical map (CLOSE arm). Image integration into the navigation system after performing LA fast electro-anatomical map. Pulmonary vein isolation with vHPSD lesions and AI targets adapted to LAWT information (QDOT-by-LAWT arm) or with according to CLOSE protocol (CLOSE arm). AI, ablation index; FAM, fast anatomical map; LAWT, left atrial wall thickness; MDCT, multidetector computed tomography; vHPSD, very high-power short-duration.

Figure 3.

Personalized PVI with local LAWT-guided vHPSD lesions. AI, ablation index; LAWT, left atrial wall thickness; vHPSD, very high-power short-duration.

Follow-up and study endpoints

In the absence of other indications, all antiarrhythmic drugs were stopped at the end of the blanking period. Patients were scheduled for follow-up at the outpatient clinic at 1, 3, 6, 12, and every 12 months thereafter or in case of symptoms. Each evaluation included an ECG and 24-h Holter ECG monitoring.

The primary endpoint was freedom from any sustained documented atrial arrhythmia [AF, atrial tachycardia (AT), or atrial flutter lasting more than 30 s] excluding the initial 3-month blanking period, regardless of symptoms, at a minimum of 12-month follow-up after a single ablation procedure.23 The secondary endpoints were procedure time, RF time, fluoroscopy time, and first-pass PVI rate. The safety endpoint was freedom from serious adverse events, defined as a procedure-related event resulting in permanent injury or death, requiring an intervention for treatment, or requiring hospitalization for more than 24 h.

Sample size and statistical analysis

The sample size calculation assumed that the proposed personalized PVI protocol with LAWT-guided vHPSD lesions (QDOT-by-LAWT arm) was an acceptable alternative to the CLOSE protocol (non-inferiority design). A non-inferiority margin of 10% of clinical success (arrhythmia-free survival at 1-year follow-up after the ablation procedure) was the largest difference considered acceptable between both arms. A drop-out rate of 5% was estimated and included in the sample size calculation. Recruiting n = 162 participants (81 patients per arm) was required to confer 90% power to reject the inferiority null hypothesis.

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (inter-quartile range) as appropriate. Categorical variables were reported as total number (percentage). Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon’s test was used to compare continuous variables, as appropriate; χ2 or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables, as appropriate. The Kaplan–Meier curves and the log-rank test were used to assess the recurrence-free survival. A level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analysed with R version 3.6.2 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and MATLAB statistics toolbox (MATLAB R2010a, The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

Results

Baseline population

Between March 2022 and January 2023, a total of 162 consecutive patients were enrolled and randomized. Baseline clinical characteristics were balanced between groups (Table 2). In the whole cohort, the mean age was 62.1 ± 10.9 years and 63.0% were male. The 18.5% of the population had a prior diagnosis of structural heart disease, being hypertensive cardiomyopathy the most prevalent (8.0%); the mean LA diameter was 38.5 ± 5.6 mm.

Table 2.

Patients’ baseline characteristics according to the study arm

| QDOT-by-LAWT (n = 81) | CLOSE (n = 81) | Total patients (n = 162) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.1 ± 10.6 | 63.1 ± 11.1 | 62.1 ± 10.9 | 0.19 |

| Male | 53 (65.4) | 49 (60.5) | 102 (63.0) | 0.62 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.3 ± 4.2 | 27.0 ± 4.2 | 26.6 ± 4.2 | 0.32 |

| Hypertension | 28 (35.6) | 31 (38.3) | 59 (36.4) | 0.51 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 15 (18.5) | 18 (22.2) | 33 (40.7) | 0.56 |

| Smoke history | 11 (13.6) | 9 (11.1) | 20 (12.3) | 0.81 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 5 (6.2) | 5 (6.2) | 10 (6.2) | 0.99 |

| LVEF | 60.8 ± 7.4 | 61.1 ± 5.6 | 61.0 ± 6.6 | 0.68 |

| LA diameter (mm) | 38.5 ± 5.3 | 38.4 ± 5.9 | 38.5 ± 5.6 | 0.89 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–3.0) | 1.0 (1.0–3.0) | 0.13 |

| HAS-BLED score | 1.0 (0.0–1.0) | 1.0 (0.0–1.0) | 1.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.79 |

| Underlying cardiomyopathy | 0.38 | |||

| None | 66 (81.5) | 66 (81.5) | 132 (81.5) | |

| Hypertensive | 4 (4.9) | 9 (11.12) | 13 (8.0) | |

| Ischaemic | 4 (4.9) | 2 (2.5) | 6 (3.7) | |

| Valvular | 3 (3.7) | 1 (1.2) | 4 (2.5) | |

| Hypertrophic | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (1.2) | |

| Other | 3 (3.7) | 2 (2.5) | 5 (3.1) |

Results are reported as n (%) for categorical variables and median (inter-quartile range) or mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables.

BMI, body mass index; LA, left atrium; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; PVs, pulmonary veins.

Procedural characteristics

Procedural results are summarized in Table 3. Total procedural skin-to-skin time was lower in the QDOT-by-LAWT group compared with the CLOSE group [40.0 min (35.0–48.0) vs. 70.0 min (60.0–76.0), P < 0.001]. More in detail, the median time of the ablation phase was significantly lower in the QDOT-by-LAWT group compared with the CLOSE group [26.0 min (23.0–32.0) vs. 53.0 min (46.0–59.0), P < 0.001]. The QDOT-by-LAWT group required a significantly lower total fluoroscopy time [59 s (39–94) vs. 74 s (57–134), P = 0.01], total emitted fluoroscopy dose [3.7 mGy (2.0–5.7) vs. 4.7 mGy (3.1–8.4), P = 0.02], and dose area product [1.0 Gy cm2 (0.6–1.6) vs. 1.4 Gy cm2 (0.9–2.3), P = 0.01]. The median RF time was significantly lower in the QDOT-by-LAWT group with respect to the CLOSE group for the isolation of both LPVs [4.1 min (3.4–5.0) vs. 13.2 min (10.8–15.1), P < 0.001] and RPVs [2.5 min (2.2–3.2) vs. 12.5 min (11.0–14.2), P < 0.001]. The median number of VisiTags was higher in the QDOT-by-LAWT group for both LPVs [26 (23–30) vs. 25 (21–27), P = 0.011] and RPVs [32 (29–36) vs. 22 (20–26), P < 0.001]. Acute PVI was achieved in all procedures. No significant differences were observed in first-pass isolation rate between the two groups for both LPVs (91.4 vs. 91.4%, P = 0.99) and RPVs (92.6 vs. 93.8%, P = 0.99). No significant differences were reported in acute reconnection rate between the two groups (9.9 vs. 4.9%, P = 0.37).

Table 3.

Procedural data according to the study arm

| QDOT-by-LAWT (n = 81) | CLOSE (n = 81) | Total patients (n = 162) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ventilation rate (breaths/min) | 50.0 ± 3.9 | 49.7 ± 4.4 | 49.8 ± 4.1 | 0.78 |

| Tidal volume (mL) | 237.2 ± 46.0 | 237.9 ± 38.2 | 237.6 ± 42.0 | 0.84 |

| Procedure time skin-to-skin (min) | 40.0 (35.0–48.0) | 70.0 (60.0–76.0) | 54.5 (40.0–70.0) | <0.001 |

| Vascular access and TSP (min) | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | 5.0 (5.0–6.0) | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | 0.16 |

| FAM and LAWT map integration (min) | 11.0 (10.0–15.0) | 12.0 (10.0–15.0) | 12.0 (10.0–15.0) | 0.10 |

| Ablation and PVI confirmation (min) | 26.0 (23.0–32.0) | 53.0 (46.0–59.0) | 41.0 (26.0–53.0) | <0.001 |

| Fluoroscopy time (s) | 59 (39–94) | 74 (57–134) | 65.0 (48.0–114.0) | 0.01 |

| Fluoroscopy dose (mGy) | 3.7 (2.0–5.7) | 4.7 (3.1–8.4) | 4.1 (2.3–6.8) | 0.02 |

| Dose area product (Gy cm2) | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) | 1.2 (0.7–2.0) | 0.01 |

| Total RF time (min) | 6.6 (5.9–7.9) | 25.7 (23.2–28.5) | 9.7 (6.6–25.6) | <0.001 |

| Total VisiTags | 60.0 (52.0–66.0) | 46.0 (43.0–51.0) | 52.0 (46.0–62.0) | <0.001 |

| Right pulmonary veins | ||||

| RF time (min) | 2.5 (2.2–3.2) | 12.5 (11.0–14.2) | 7.6 (2.5–12.5) | <0.001 |

| VisiTags | 32 (29–36) | 22 (20–26) | 28 (22–33) | <0.001 |

| First-pass isolation | 75 (92.6) | 76 (93.8) | 151 (93.2) | 0.99 |

| Acute reconnection | 6 (7.4) | 3 (3.7) | 9 (5.6) | 0.50 |

| Anterior right PVs antrum WT (mm) | 1.31 (1.02–1.62) | 1.29 (1.00–1.59) | 1.30 (1.01–1.61) | 0.42 |

| Posterior right PVs antrum WT (mm) | 0.99 (0.74–1.23) | 0.98 (0.72–1.20) | 0.99 (0.73–1.21) | 0.46 |

| Left pulmonary veins | ||||

| RF time (min) | 4.1 (3.4–5.0) | 13.2 (10.8–15.1) | 7.5 (4.1–13.1) | <0.001 |

| VisiTags | 26 (23–30) | 25 (21–27) | 26 (22–29) | 0.01 |

| First-pass isolation | 74 (91.4) | 74 (91.4) | 148 (91.4) | 0.99 |

| Acute reconnection | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.2) | 3 (1.9) | 0.99 |

| Anterior left PV antrum WT (mm) | 1.97 (1.54–2.36) | 1.94 (1.52–2.34) | 1.95 (1.53–2.35) | 0.36 |

| Posterior left PV antrum WT (mm) | 0.97 (0.73–1.24) | 0.95 (0.71–1.21) | 0.96 (0.72–1.23) | 0.43 |

| Overall acute first-pass | 68 (84.0) | 69 (85.2) | 137 (84.6) | 0.99 |

| Overall acute reconnection | 8 (9.9) | 4 (4.9) | 12 (7.4) | 0.37 |

| Acute procedural complication | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.5) | 3 (1.9) | 0.99 |

Results are reported as n (%) for categorical variables and median (inter-quartile range) or mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables. P-values indicative of statistically significant differences are shown in bold.

AI, ablation index; FAM, fast anatomical map; RF, radiofrequency; SR, sinus rhythm; TSP, transseptal puncture; WT, wall thickness.

Serious adverse events occurred in three patients (1.9%) with no significant differences between the groups (1.2 vs. 2.5%, P = 0.99). In the QDOT-by-LAWT group, pseudoaneurysm at femoral puncture site requiring treatment with thrombin injection occurred in one patient. In the CLOSE group, one patient experienced a pseudoaneurysm at femoral puncture site requiring treatment with thrombin injection, while one patient experienced post-procedural segmental pulmonary thromboembolism treated with anticoagulant therapy, first subcutaneously and then oral. No neurological complications were observed, and no patient died. Two patients of the CLOSE group experienced pericarditis within 15 days of the procedure, which did not require hospitalization, even if these events did not fall within the safety endpoint.

Long-term outcomes

All patients discontinued the antiarrhythmic drugs after the 3-month blanking period. Five patients (3.1%), three in the QDOT-by-LAWT group and two in the CLOSE group, did not complete the 12-month follow-up and were excluded from the long-term analysis. At the end of the 12-month follow-up, 12 patients (15.4%) of the QDOT-by-LAWT group and 11 (13.9%) of the CLOSE group experienced AT/AF recurrence (P = 0.88).

Procedural outcomes and atrial arrhythmia-free survival Kaplan–Meier curves according to the study arm are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Procedural outcomes (A) and atrial arrhythmia-free survival Kaplan–Meier curves (B) according to the study arm.

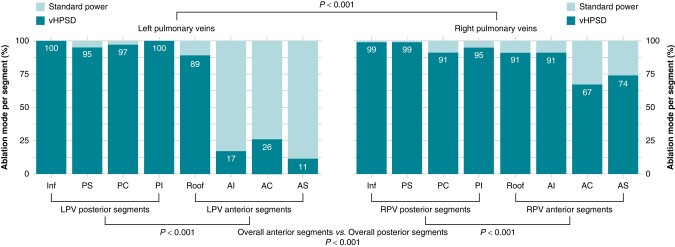

Left atrial wall thickness-guided very high-power short-duration lesion distribution

In the QDOT-by-LAWT group, the percentage of LAWT-guided vHPSD ablation lesions was evaluated across the PV antra segments. The use of vHPSD ablation was found to be significantly less frequent in the LPVs with respect to the RPVs antra (67.0 vs. 88.4%, P < 0.001), while it was significantly more frequently delivered in the posterior segments compared with the anterior segments of both LPVs (98.1 vs. 35.8%, P < 0.001) and RPVs (96.0 vs. 80.9%, P < 0.001). vHPSD ablation was also significantly more frequently used at the PV inferior segments compared with the PV superior segments (83.7 vs. 76.5%, P = 0.01). It is worth noting that only for the inferior and postero-inferior segments of the RPVs, vHPSD-only was used in the 100% of patients. In all other segments whether they concern the anterior or the posterior aspect of LPVs or RPVs antrum, depending on the patient’s LAWT, it was used vHPSD or standard-power RF lesions.

Histogram plots of the ablation mode use for each segment of PV antra in the QDOT-by-LAWT arm are represented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Histogram plots of the ablation mode use for each pulmonary vein segment in the QDOT-by-LAWT arm. AC, anterior carina; AI, antero-inferior; AS, antero-superior; Inf, inferior; LPV, left pulmonary vein; PC, posterior carina; PI, postero-inferior; PS, postero-superior; RPV, right pulmonary vein; vHPSD, very high-power short-duration.

Discussion

Main findings

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective randomized study comparing the 1-year outcomes of a vHPSD ablation protocol with the standard of care CLOSE protocol for PAF ablation. The main findings of the study are: (i) a local LAWT-guided personalized PVI combining vHPSD and standard-power RF lesions is a feasible approach for PAF ablation leading to a high first-pass PVI rate, comparable with the standard of care; (ii) the QDOT-by-LAWT approach is safe, reporting no RF-related adverse events and a low rate of major complications, not statistically different from the control group; (iii) the QDOT-by-LAWT protocol proved to be more efficient with respect to the CLOSE protocol, demonstrating a significant reduction in procedural, fluoroscopy, and RF times; (iv) a LAWT-guided strategy combining vHPSD and standard-power lesions for PAF ablation is associated with a high-rate recurrence-free survival at 12-month follow-up, demonstrating no differences with the standard of care.

Safety outcomes

High-power RF delivery has been proposed as a strategy to improve PVI efficiency; however, the safety window is narrow, especially for the risk of collateral damage. The importance of temperature cut-off was confirmed by an increased incidence of steam pops with ablation at high-power, highlighting the importance of temperature monitoring and automated power regulation during high-power ablation.7 The QDOT catheter allows a temperature-controlled ablation and a real-time monitoring of temperature at the tip–tissue interface. The vHPSD strategy aims to minimize the conductive heating and increase the resistive heating to achieve transmural lesions in thin structures minimizing the risk of collateral tissue damage. Recently published preclinical work has provided confirmation that vHPSD lesions exhibit distinct anatomical profile with a higher ratio of diameter to depth, which may be favourable for linear ablation at thin sites of the atrial wall to decrease the risk of collateral injury.24 The combination of vHPSD lesions with LAWT information allows to locate thick and thin LA wall areas, thereby enhancing a personalized and safe RF energy delivery. Notably, we reported no RF-related adverse events, such as deaths, strokes, atrioesophageal fistulas, or cases of symptomatic PV stenosis, confirming the good safety profile previously described for the QDOT catheter.

Procedural and clinical effectiveness of very high-power short-duration ablation

The objective of PVI is to create a transmural, continuous, and permanent damage. Nakagawa et al.24 reported that the vHPSD applications result in shallower lesions and may not span the full thickness of the anterior aspects of the PV antra. Non-transmural ablation lesion is a major determinant of post-AF ablation recurrence. It has been shown that PV reconnection could be due to insufficient lesion depth.25

Previous clinical studies reported that ablations with 90 W-only lesions with a maximum ILD of 6 mm were associated with a lower rate of first-pass isolation and a higher rate of acute PV reconnection.5,26,27 These data seem to confirm the results reported by Nakagawa et al.24 demonstrating that the smaller depth of vHPSD lesions may well exceed tissue thickness in the thin regions, but not in the thicker regions. For this reason, different ablation protocols have been proposed, in which the maximum ILD was empirically reduced to <4 mm in the supposedly thicker PV antrum regions, like the anterior ones.20,22,28 On the other hand, if the ILD is too small, it can result in overlapping ablation lesions, excessive heating, and potentially increasing the risk of complications. The information of the patient LAWT at the target tissue site gives us the clue to tailor the RF delivery, switching to the standard-power ablation mode or eventually, tailoring ILD. In another recent non-randomized study, an empirical approach combining 90 W lesions posteriorly and 50 W lesions anteriorly for PAF ablation was compared; however, this empirical combined PVI strategy did not improve safety, efficiency, or effectiveness compared with a 50 W-only strategy.29 It is known that even if the posterior wall is thinner than the anterior one, not all posterior segments of the PV antrum have a LAWT <2.5 mm and therefore in some areas, the lesion may be non-transmural.

In the recent POWER PLUS randomized trial,22 a completely vHPSD ablation protocol reported shorter procedure times and similar 6-month follow-up outcomes with respect to a conventional 35/50 W approach. However, a trend towards lower rate of first-pass isolation and the short follow-up duration rise concerns about the lesion durability and long-term efficacy. To address these concerns and achieve an optimal balance of procedural efficiency and outcomes, the authors suggested the potential benefits of a hybrid approach combining vHPSD applications with conventional applications in regions of increased tissue thickness. The RF delivery tailoring in the QDOT-by-LAWT approach effectively addresses the observed limitations.

Efficiency outcomes

A median procedure time of 40 min reported in the QDOT-by-LAWT group means an efficient ablation protocol compared with the CLOSE group (median procedure time of 70 min) but also with single-shot systems. Recent studies utilizing the cryoballoon reported a mean procedure times of 64 ± 22 min.30,31 The low procedural time of the presented study is not solely attributable to the use of the vHPSD ablation mode but also to the contextual use of a single-catheter approach and of the general anaesthesia with HFLTV ventilation, which already proved to increase procedural efficiency.19,32 The single-catheter approach contributes to simplify the workflow and to expedite the procedure, also due to the use of the tip-located microelectrodes which allow an accurate analysis of near-field PV signals. While high-density electro-anatomical mapping can offer additional insights into the electrical substrate, it may not be crucial for first-time PAF ablation, for which the primary strategy would typically focus on PVI alone. With its potential for achieving similar or even faster PVI compared with single-shot ablation, the ability to implement additional ablation strategies in both LA and right atrium, and an excellent safety profile, vHPSD ablation has the potential to become a commonly utilized tool in ablation procedures.

The reported median skin-to-skin procedure time is the result of the combination of technical choices that aim to optimize the procedural efficiency and minimize the LA dwelling time. First of all, the use of a catheter that allows vHPSD lesions made it possible to reduce the ablation time as reported in the FAST and FURIOUS study;21 on the other hand, also the use of a LAWT-guided ablation protocol for the standard-power lesions was reported in a previous single-centre study8 to reduce procedural requirements in terms of RF delivery, procedure, and fluoroscopy time. Simultaneously, the use of a single-catheter technique19 requires a single venous access, the introduction of a single transseptal guiding introducer, a single transseptal puncture, and the movement of a single catheter within the LA, minimizing the number of procedural steps and therefore reducing the possibility of technical complications and possible slowdowns. Finally, the use of HFLTV ventilation allows to increase the stability of the catheter and therefore to further reduce procedural times in the ablation phase,32 but also allows the creation of the FAM in the absence of the use of respiratory gating, in order to take points every heartbeat.

Finally, in the current era that is veering towards high-power short-duration ablation, further randomized controlled trials are needed to compare the results of the proposed QDOT-by-LAWT approach and a high-power ablation protocol for PVI.

Left atrial wall thickness-guided personalized ablation

There is increasing evidence from post-mortem studies and in vivo imaging studies that support the understanding of the complex anatomical structure of the LA and its intra- and inter-patient regional variability of LAWT distribution in both anterior and posterior segments of PV–LA junction.33,34 Accordingly, the duration and the intensity of RF delivery necessary to create full-thickness lesions need to be adjusted. Therefore, fixed AI targets and a dichotomized anterior/posterior ablation approach could be an oversimplification and may not fully reflect the needs, leading to non-transmural lesions in the thicker LA regions and on the other hand excessive RF applications in the thinnest ones.

Multidetector computed tomography-derived LAWT measurements have been reliably validated on a porcine model,33 and integrating 3D LAWT maps into the navigation system allows to be aware of the real-time local LAWT in contact with the ablation catheter tip during the procedure. Our research group has previously described and utilized this tool to assist PAF ablation.8 In the QDOT-by-LAWT trial, the proposed personalized ablation protocol modifies the ablation line to avoid the thicker atrial areas, changes the ablation mode according to the local LAWT, and titrates the AI targets in the thicker segments, therefore likely improving the lesion transmurality and consequently the PVI durability. Different ranges of wall thickness were observed regardless of the anterior/posterior aspect, with a LAWT ranging from 0.3 to 4.5 mm.8 It is worth noting that from the data of our cohort, not 100% of patients have a LAWT <2.5 mm in the posterior segments of the antrum of the PVs, and therefore, a dichotomization with the aim of vHPSD lesions for the posterior segments isolation would not obtain transmural lesions in all patients; on the other hand, the use of vHPSD lesions in the anterior wall especially of the antrum of the LPVs is not appropriate to achieve transmural lesions in a significant percentage of patients. vHPSD ablation was exclusively employed in the 100% of patients only for the inferior and postero-inferior segments of the RPVs. However, in all other segments, including both the anterior and posterior aspects of the LPVs or RPVs antra, a combination of vHPSD and standard-power RF lesions was used based on the patient’s LAWT. This observation indicates not only variability in thickness between different segments of the PVs but also variation between patients within the same segment of the antrum of the PVs. Understanding this variability in LAWT is crucial, as without LAWT maps, predicting the ablation mode in a specific segment becomes challenging.

We acknowledge that conducting a pre-procedural MDCT scan is a necessary part of the QDOT-by-LAWT approach, which can consume both time and resources; however, it is important to note that pre-procedural MDCT scan is the standard practice in many centres, where MDCT scans are routinely performed before every AF catheter ablation to assess PV anatomy.35 In a recent European Survey, 48% of physicians asserted to perform a MDCT and/or magnetic resonance imaging previously to the ablation procedure.36

Limitations

Despite the power setting of 35 W is currently widely used in numerous centres,37 the CLOSE approach has evolved to a faster PVI strategy using 45/50 W, which could also be equally safe; however, concerns about safety remain for high-power settings using catheters not specifically designed for that purpose.22,38–41 A main limitation of the study is the single-centre design which does not allow the generalizability of the results. Secondly, AI targets for each LAWT range were based on empirical data already used in several published studies;8,14,42 further research is needed to evaluate the optimal parameters of AI application according to the LAWT. Thirdly, all procedures were performed under general anaesthesia, mechanical ventilation with HFLTV and with CARTO3 mapping system; thus, the study results may not be the same if other procedural settings are used. Fourthly, we adopted the classical 3-month blanking period, but we cannot exclude that a shorter blanking period, might be preferable.43,44 Fifthly, in the absence of continuous rhythm monitoring by loop recorder implantation or 7-day Holter monitoring, it is possible that brief arrhythmic episodes were missed, thereby overestimating recurrence-free survival rates;45–47 however, both ablation strategy groups would be expected to be similarly affected. Finally, although a follow-up time of 1 year is the most used in trials on the effectiveness of AF ablation, it is still temporally limited; recurrence-free survival rate at long-term follow-up would be better data for comparing the quality and durability of the lesions in the two groups.

Conclusions

The findings from this prospective randomized trial indicate that a LAWT-guided personalized PVI approach, alternating between vHPSD and standard-power ablation modes for PAF ablation, is not inferior to the CLOSE protocol in terms of arrhythmia-free survival at 1-year follow-up. The proposed approach demonstrated a relevant reduction in procedural, fluoroscopy, and RF times.

Authors’ contribution

G.F., D.P., D.S.-I., and An.B.: study concept and design, manuscript drafting, and critical revision. P.F., D.T., D.V., Al.B., J.A., F.Z., P.F-O., M.H., O.C., R.V., J.-T.O.-P., and J.M.-A.: manuscript drafting and critical revision. A.S.: contribution to major revision answers and critical revision.

Contributor Information

Giulio Falasconi, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain; Campus Clínic, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Arrhythmology Department, IRCCS Humanitas Research Hospital, Rozzano, Italy.

Diego Penela, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain; Arrhythmology Department, IRCCS Humanitas Research Hospital, Rozzano, Italy.

David Soto-Iglesias, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain.

Pietro Francia, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain; Division of Cardiology, Department of Clinical and Molecular Medicine, St. Andrea Hospital, Sapienza University, Rome, Italy.

Andrea Saglietto, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain; Department of Medical Sciences, University of Turin, Turin, Italy.

Dario Turturiello, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain; Open Heart Foundation, Barcelona, Spain.

Daniel Viveros, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain; Campus Clínic, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Aldo Bellido, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain.

Jose Alderete, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain; Campus Clínic, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Open Heart Foundation, Barcelona, Spain.

Fatima Zaraket, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain.

Paula Franco-Ocaña, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain.

Marina Huguet, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain.

Óscar Cámara, Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona, Spain.

Radu Vătășescu, Faculty of Medicine, ‘Carol Davila’ University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 050474 Bucharest, Romania.

José-Tomás Ortiz-Pérez, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain.

Julio Martí-Almor, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain.

Antonio Berruezo, Heart Institute, Teknon Medical Centre, Calle Villana 12, 08022 Barcelona, Spain.

Funding

The funding for this study was provided by Biosense Webster, Inc. (Irvine, California, United States) through an IIS grant (IIS-592).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021;42:373–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Das M, Loveday JJ, Wynn GJ, Gomes S, Saeed Y, Bonnett LJ et al. Ablation index, a novel marker of ablation lesion quality: prediction of pulmonary vein reconnection at repeat electrophysiology study and regional differences in target values. Europace 2017;19:775–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taghji P, El Haddad M, Phlips T, Wolf M, Knecht S, Vandekerckhove Y et al. Evaluation of a strategy aiming to enclose the pulmonary veins with contiguous and optimized radiofrequency lesions in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a pilot study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018;4:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Duytschaever M, De Pooter J, Demolder A, El Haddad M, Phlips T, Strisciuglio T et al. Long-term impact of catheter ablation on arrhythmia burden in low-risk patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: the CLOSE to CURE study. Heart Rhythm 2020;17:535–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reddy VY, Grimaldi M, De Potter T, Vijgen JM, Bulava A, Duytschaever MF et al. Pulmonary vein isolation with very high power, short duration, temperature-controlled lesions: the QDOT-FAST trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2019;5:778–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bourier F, Duchateau J, Vlachos K, Lam A, Martin CA, Takigawa M et al. High-power short-duration versus standard radiofrequency ablation: insights on lesion metrics. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2018;29:1570–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leshem E, Zilberman I, Tschabrunn CM, Barkagan M, Contreras-Valdes FM, Govari A et al. High-power and short-duration ablation for pulmonary vein isolation: biophysical characterization. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018;4:467–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Teres C, Soto-Iglesias D, Penela D, Jauregui B, Ordonez A, Chauca A et al. Personalized paroxysmal atrial fibrillation ablation by tailoring ablation index to the left atrial wall thickness: the ‘Ablate by-LAW’ single-centre study—a pilot study. Europace 2022;24:390–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berruezo A, Penela D, Jauregui B, de Asmundis C, Peretto G, Marrouche N et al. Twenty-five years of research in cardiac imaging in electrophysiology procedures for atrial and ventricular arrhythmias. Europace 2023;25:euad183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saglietto A, Falasconi G, Soto-Iglesias D, Francia P, Penela D, Alderete J et al. Assessing left atrial intramyocardial fat infiltration from computerized tomography angiography in patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace 2023;25:euad351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jauregui B, Soto-Iglesias D, Penela D, Acosta J, Fernandez-Armenta J, Linhart M et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance determinants of ventricular arrhythmic events after myocardial infarction. Europace 2022;24:938–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Francia P, Viveros D, Falasconi G, Soto-Iglesias D, Fernandez-Armenta J, Penela D et al. Computed tomography-based identification of ganglionated plexi to guide cardioneuroablation for vasovagal syncope. Europace 2023;25:euad170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Falasconi G, Penela D, Soto-Iglesias D, Marti-Almor J, Berruezo A. Cardiac magnetic resonance and segment of origin identification algorithm streamline post-myocardial infarction ventricular tachycardia ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2022;8:1603–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Falasconi G, Penela D, Soto-Iglesias D, Francia P, Teres C, Saglietto A et al. Personalized pulmonary vein antrum isolation guided by left atrial wall thickness for persistent atrial fibrillation. Europace 2023;25:euad118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Valles-Colomer A, Rubio Forcada B, Soto-Iglesias D, Planes X, Trueba R, Teres C et al. Reproducibility analysis of the computerized tomography angiography-derived left atrial wall thickness maps. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2023;66:1045–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gabriels J, Donnelly J, Khan M, Anca D, Beldner S, Willner J et al. High-frequency, low tidal volume ventilation to improve catheter stability during atrial fibrillation ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2019;5:1224–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garcia R, Waldmann V, Vanduynhoven P, Nesti M, Jansen de Oliveira Figueiredo M, Narayanan K et al. Worldwide sedation strategies for atrial fibrillation ablation: current status and evolution over the last decade. Europace 2021;23:2039–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Falasconi G, Penela D, Soto-Iglesias D, Jauregui B, Chauca A, Antonio RS et al. A standardized stepwise zero-fluoroscopy approach with transesophageal echocardiography guidance for atrial fibrillation ablation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2022;64:629–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pambrun T, Combes S, Sousa P, Bloa ML, El Bouazzaoui R, Grand-Larrieu D et al. Contact-force guided single-catheter approach for pulmonary vein isolation: feasibility, outcomes, and cost-effectiveness. Heart Rhythm 2017;14:331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bortone AA, Ramirez FD, Constantin M, Bortone C, Hebert C, Constantin J et al. Optimal interlesion distance for 90 and 50 watt radiofrequency applications with low ablation index values: experimental findings in a chronic ovine model. Europace 2023;25:euad310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heeger CH, Sano M, Popescu SS, Subin B, Feher M, Phan HL et al. Very high-power short-duration ablation for pulmonary vein isolation utilizing a very-close protocol-the FAST AND FURIOUS PVI study. Europace 2023;25:880–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O’Neill L, El Haddad M, Berte B, Kobza R, Hilfiker G, Scherr D et al. Very high-power ablation for contiguous pulmonary vein isolation: results from the randomized POWER PLUS trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2023;9:511–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kirchhof P, Auricchio A, Bax J, Crijns H, Camm J, Diener HC et al. Outcome parameters for trials in atrial fibrillation: recommendations from a consensus conference organized by the German Atrial Fibrillation Competence NETwork and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace 2007;9:1006–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nakagawa H, Ikeda A, Sharma T, Govari A, Ashton J, Maffre J et al. Comparison of in vivo tissue temperature profile and lesion geometry for radiofrequency ablation with high power-short duration and moderate power-moderate duration: effects of thermal latency and contact force on lesion formation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2021;14:e009899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. El Haddad M, Taghji P, Phlips T, Wolf M, Demolder A, Choudhury R et al. Determinants of acute and late pulmonary vein reconnection in contact force-guided pulmonary vein isolation: identifying the weakest link in the ablation chain. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2017;10:e004867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bortone A, Albenque JP, Ramirez FD, Haissaguerre M, Combes S, Constantin M et al. 90 vs 50-watt radiofrequency applications for pulmonary vein isolation: experimental and clinical findings. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2022;15:e010663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Richard Tilz R, Sano M, Vogler J, Fink T, Saraei R, Sciacca V et al. Very high-power short-duration temperature-controlled ablation versus conventional power-controlled ablation for pulmonary vein isolation: the fast and furious—AF study. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2021;35:100847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Solimene F, Strisciuglio T, Schillaci V, Arestia A, Shopova G, Salito A et al. One-year outcomes in patients undergoing very high-power short-duration ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2023;66:1911–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bortone AA, Ramirez FD, Combes S, Laborie G, Albenque JP, Sebag FA et al. Optimized workflow for pulmonary vein isolation using 90-W radiofrequency applications: a comparative study. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2024;67:353–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Della Rocca DG, Marcon L, Magnocavallo M, Mene R, Pannone L, Mohanty S et al. Pulsed electric field, cryoballoon, and radiofrequency for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation ablation: a propensity score-matched comparison. Europace 2023;26:euae016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tanese N, Almorad A, Pannone L, Defaye P, Jacob S, Kilani MB et al. Outcomes after cryoballoon ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation with the PolarX or the Arctic Front Advance Pro: a prospective multicentre experience. Europace 2023;25:873–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Osorio J, Zei PC, Diaz JC, Varley AL, Morales GX, Silverstein JR et al. High-frequency low-tidal volume ventilation improves long-term outcomes in AF ablation: a multicenter prospective study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2023;9:1543–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bishop M, Rajani R, Plank G, Gaddum N, Carr-White G, Wright M et al. Three-dimensional atrial wall thickness maps to inform catheter ablation procedures for atrial fibrillation. Europace 2016;18:376–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Veinot JP, Harrity PJ, Gentile F, Khandheria BK, Bailey KR, Eickholt JT et al. Anatomy of the normal left atrial appendage: a quantitative study of age-related changes in 500 autopsy hearts: implications for echocardiographic examination. Circulation 1997;96:3112–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dong J, Calkins H, Solomon SB, Lai S, Dalal D, Lardo AC et al. Integrated electroanatomic mapping with three-dimensional computed tomographic images for real-time guided ablations. Circulation 2006;113:186–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Iliodromitis K, Lenarczyk R, Scherr D, Conte G, Farkowski MM, Marin F et al. Patient selection, peri-procedural management, and ablation techniques for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: an EHRA survey. Europace 2023;25:667–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boersma L, Andrade JG, Betts T, Duytschaever M, Purerfellner H, Santoro F et al. Progress in atrial fibrillation ablation during 25 years of Europace journal. Europace 2023;25:euad244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Almorad A, Wielandts JY, El Haddad M, Knecht S, Tavernier R, Kobza R et al. Performance and safety of temperature- and flow-controlled radiofrequency ablation in ablation index-guided pulmonary vein isolation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2021;7:408–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Berte B, Hilfiker G, Russi I, Moccetti F, Cuculi F, Toggweiler S et al. Pulmonary vein isolation using a higher power shorter duration CLOSE protocol with a surround flow ablation catheter. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2019;30:2199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chen S, Schmidt B, Bordignon S, Urbanek L, Tohoku S, Bologna F et al. Ablation index-guided 50 W ablation for pulmonary vein isolation in patients with atrial fibrillation: procedural data, lesion analysis, and initial results from the FAFA AI High Power Study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2019;30:2724–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wielandts JY, Kyriakopoulou M, Almorad A, Hilfiker G, Strisciuglio T, Phlips T et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of high power during CLOSE-guided pulmonary vein isolation: the POWER-AF study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2021;14:e009112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Teres C, Soto-Iglesias D, Penela D, Falasconi G, Viveros D, Meca-Santamaria J et al. Relationship between the posterior atrial wall and the esophagus: esophageal position and temperature measurement during atrial fibrillation ablation (AWESOME-AF). A randomized controlled trial. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2022;65:651–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Saglietto A, Ballatore A, Xhakupi H, Rubat Baleuri F, Magnano M, Gaita F et al. Evidence-based insights on ideal blanking period duration following atrial fibrillation catheter ablation. Europace 2022;24:1899–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bordignon S, Barra S, Providencia R, de Asmundis C, Marijon E, Farkowski MM et al. The blanking period after atrial fibrillation ablation: an European Heart Rhythm Association survey on contemporary definition and management. Europace 2022;24:1684–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kalarus Z, Mairesse GH, Sokal A, Boriani G, Sredniawa B, Casado-Arroyo R et al. Searching for atrial fibrillation: looking harder, looking longer, and in increasingly sophisticated ways. An EHRA position paper. Europace 2023;25:185–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Manninger M, Zweiker D, Svennberg E, Chatzikyriakou S, Pavlovic N, Zaman JAB et al. Current perspectives on wearable rhythm recordings for clinical decision-making: the wEHRAbles 2 survey. Europace 2021;23:1106–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Svennberg E, Tjong F, Goette A, Akoum N, Di Biase L, Bordachar P et al. How to use digital devices to detect and manage arrhythmias: an EHRA practical guide. Europace 2022;24:979–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.