Abstract

Background:

Animal models are used to guide management of periprosthetic implant infections. No adequate model exists for periprosthetic shoulder infections, and clinicians thus have no preclinical tools to assess potential therapeutics. We hypothesize that it is possible to establish a mouse model of shoulder implant infection (SII) that allows non-invasive, longitudinal tracking of biofilm and host response through in-vivo optical imaging. The model may then be employed to validate a targeting-probe (1D9–680) with clinical translation potential for diagnosing infection and image-guided débridement.

Methods:

A surgical implant was press fit into the proximal humerus of c57BL/6J mice and inoculated with 2ul of 1 × 103 (e3), or 1 × 104 (e4), colony forming units (CFUs) of bioluminescent Staphylococcus aureus-Xen-36. The control group received 2ul sterile-saline. Bacterial activity was monitored in-vivo over 42 days, directly (bioluminescence) and indirectly (targeting-probe). Weekly X-rays assessed implant loosening. CFU-harvests, confocal microscopy, and histology were performed.

Results:

Both inoculated groups established chronic infections. CFUs on postoperative day (POD) 42 were increased in the infected groups as compared to the sterile group (p<0.001). By POD 14, osteolysis was visualized in both infected groups. The e4 group developed catastrophic bone destruction by POD 42. The e3 group maintained a congruent shoulder joint. Targeting-probes helped to visualize low-grade infections via fluorescence.

Discussion:

Given bone destruction in the e4 group, a longitudinal, non-invasive mouse model of SII and chronic osteolysis was produced using e3 of S. aureus-Xen-36, mimicking clinical presentations of chronic SII.

Conclusion:

The development of this model provides a foundation to study new therapeutics, interventions, and host modifications.

Level of evidence:

Basic Science Study

Keywords: Shoulder, Implant, Infection, Osteolysis, Osteomyelitis, Arthroplasty

Shoulder implant infections (SII) are devastating for patients, requiring revision surgery, threatening both life and limb. With a 7–13% annual increase in the demand for shoulder arthroplasty,5,15,16,25,28 we have seen a concurrent increase in the incidence of arthroplasty infections.7,28,29 Patients with SII subsequently suffer from hardware loosening/shoulder instability (32%), pathological fracture (6%), revision surgeries (of which 4% become reinfected), severe pain requiring increased opiate consumption (13%), and an overall decreased quality of life.3,5,7,9,15,16,17,25,28,29,34

SII are characterized by unique risk factors, pathogens, and diagnostic challenges. The literature suggests that physically active males, immunosuppressed patients, those with traumatic injuries, and patients undergoing reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) are at higher risk for SII.4,6,20,22,27 Staphylococcus aureus and Propionibacterium acnes are the predominant pathogens implicated in these periprosthetic infections.1,4,20,22,26,27,34 Both of these species are capable of producing a thick biofilm matrix on implants, which insulates them from the host immune system and antibiotics. Without surgical débridement and appropriate antibiotic therapy, these infections will persist and, ultimately, the hardware is at risk of failure.3,8,9,12,23,31,32

Given that periprosthetic SII tend to be slow growing infections associated with biofilm formation, a longitudinal assay is needed to better characterize the nature of such infections, to refine diagnostic approaches and to improve treatment modalities. 8,12,23,32 Few animal models exist that quantify bacterial burden in vivo to facilitate the study of the natural course of infection, with only one shoulder study examining SII.2,10,13,19 However, this model did not measure real-time bacterial activity or allow for longitudinal tracking of infection in living subjects.13 An animal model of periprosthetic SII that relies on single time point histological analysis does not have the sensitivity to adequately identify infections that are surreptitious and low grade, nor assess the long-term sequela of these infections. Consequently, we sought to establish a longitudinal, non-invasive, and reproducible mouse model of SII using bioluminescent S. aureus Xen-36 and optical imaging in an effort to better examine the underlying pathophysiology. A non-invasive and longitudinal model allows a single animal to provide a multitude of data points, which is more efficient, cost effective, and humane than sacrificing animals for single time point histological assays. Technical challenges in genetically transforming slow-growing, anaerobic P. acnes precludes its utilization in this model at present, but this work aims to develop a platform to which P. acnes infections could eventually be studied as well.8,12 Prior work outside of the shoulder has established the accuracy, efficiency and value of noninvasive in vivo imaging, especially optical imaging, to replace euthanasia-based models to study infection.3,9,11,30 The mouse humerus is comparable in diameter to its femur, which has been used previously to model implant infections in the knee joint; increasing the likelihood of success when adapting this model from the hindlimb to the forelimb.3,9,14,18 Importantly, the use of the 1D9–680 fluorescent antibody probe to target S. aureus biofilm infections in this model facilitates the possibility of using optical imaging in the clinic to accurately identify low-grade biofilm-associated SII in real time. The capacity to observe infection over time, and its response to antibiotics, implant coatings, and immune modulation, has led to a better understanding of the pathophysiology of implant infection and the development of new antimicrobial therapies.3,9,11,30

The purpose of this study was to develop a longitudinal and noninvasive model of periprosthetic SII that can be used as a platform to analyze the pathophysiology of these infections, as well as test and guide future diagnostic and treatment strategies. We hypothesized that it is possible to create such a model using mice, following similar non-invasive optical imaging techniques used to establish and visualize implant infections in the knee and spine.3,9 Moreover, we speculated that it would be possible to target and identify S. aureus biofilm on SII using a fluorescently labeled probe previously validated in a spine infection model; thus increasing the potential for this animal model to be surgically translatable.35

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

All animals were handled in accordance with animal practices defined in the federal regulations detailed in the Animal Welfare Act (AWA), the 1996 Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, PHS Policy for the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as well as UCLA’s policies, and procedures as set forth in the UCLA Animal Care and Use Training Manual. The UCLA Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee (ARC) approved all animal work below (ARC# 2008–112-21L).

Xen-36 Bioluminescent Staphylococcus aureus Strain

Mice were inoculated with S. aureus Xen-36 (PerkinElmer, Hopkinton, MA, USA), a bioluminescent derivative of the clinical isolate S. aureus ATCC 49525 (Wright) stably transformed with a modified luxABCDE operon from Photorhabdus luminescens, flanked by a kanamycin resistance cassette.3,9,11,30 Metabolically active Xen-36 produces a blue/green light with emission wavelength of 490nm 9, 11 Strength and consistency of the Xen-36 bioluminescent signal have been confirmed in previous studies and validated. 3,9, 21,30,35

Preparation of S. aureus Xen-36 for Inoculation

Inoculations of S. aureus Xen-36 were prepared as previously described.3,9,11,30 Xen-36 was streaked from a frozen stock onto agar plates (Luria Broth [LB] plus 1.5% bacto agar, Teknova) containing 200 μg/ml kanamycin (Sigma–Aldrich) and cultured at 37° C overnight. Single colonies of S. aureus were then individually grown in TSB containing 200 μg/ml kanamycin, and cultured again overnight at 37°C in a shaking incubator (200 rpm) (MaxQ 4,450, Thermo). After a 2h subculture in TSB of a 1:50 dilution from the overnight culture, mid-logarithmic phase bacteria were obtained. Lastly, using centrifugation, bacterial cells were pelleted, resuspended, and washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Bacterial inoculums (1*103 and 1*104 colony forming units (CFUs) in 2ul PBS) were approximated by measuring the absorbance at 600nm (A600, Biomate 3 [Thermo]).

Subjects

Twelve-week-old male C57BL/six wildtype mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were used in this study.3,9,11,30 Mice were housed in cages, 4 at a time, and stored with a 12-hour light and dark cycle. Standard diet and water were available at all times. Veterinary staff assessed mice daily to ensure the wellbeing of the animals throughout the totality of the experiment.

Experimental Protocol

There were three arms in this study based on prior experience of infection knee arthroplasty dosing in the same host: (1) control, (2) low inoculum, and (3) high inoculum groups.3,9,11,21,30 (1) 6 mice in the sterile control group received 2uL of sterile saline (0.9% NaCl) instead of bacteria. (2) 13 mice in the low inoculum “e3” group received a 2uL inoculation of 1*103 bioluminescent S. aureus Xen-36 bacterial CFUs. (3) 8 mice in the high inoculum “e4” group received a 2uL inoculation of 1*104 of the same bacteria. All mice survived to study completion on POD 42. Power analysis necessitated a minimum of 6 subjects per group. Additional subjects were utilized in groups e3 and e4 for comparative purposes.

Mouse Surgical Procedures

Survival shoulder surgery was performed using a custom 5.0mm steel implant (0.6mm in diameter) with a 15-degree bend at the most proximal end (1mm from cut end), which mimicked the anatomy of the humerus. The steel implant was acquired from Modern Grinding (Port Washington, WI) and implanted into the humerus. Mice were anesthetized via inhalation of isoflurane (2%) in accordance to previously established surgical protocols.3,9,11,21,30 The shoulder joint was approximated by palpating superiorly towards the most proximal aspect of the humerus. An incision was made starting at the sternum and extending laterally across the deltoid, which exposed the deltopectoral groove beneath. Next, the pectoralis musculature was removed from its insertion on the humerus. Once near the humeral head, the joint was exposed by applying anterior directed pressure on the posterior aspect of an extended and externally rotated humerus, which subluxed the joint anteriorly. A 25-gauge needle was used to ream the most proximal aspect of the humeral head, with the needle aimed towards the palpable deltoid tuberosity. The needle was then removed, allowing the placement of the implant, with the implant’s most proximal aspect communicating with the glenoid fossa within the shoulder joint. 5–0 Vicryl was then used to approximate the deep fascial layers. These sutures were placed but not tied to allow for expedient closure after inoculation and to restrict bacteria to the immediate area of the implant.9,11,21,30 Next, a 2ul inoculation of 1*103 (e3 group) or 1*104 (e4 group) CFUs of bioluminescent S. aureus Xen-36 or sterile saline (control group) was pipetted onto the tip of the implant. Deep sutures were tied and a running 5–0 Vicryl was used to approximate the skin. Sustained release buprenorphine (2.5 mg/kg) (Zoo-Pharm, Fort Collins, CO) was then administered subcutaneously every 72h as analgesic for the duration of the experiment. All surgical procedures are detailed in Figure 1.

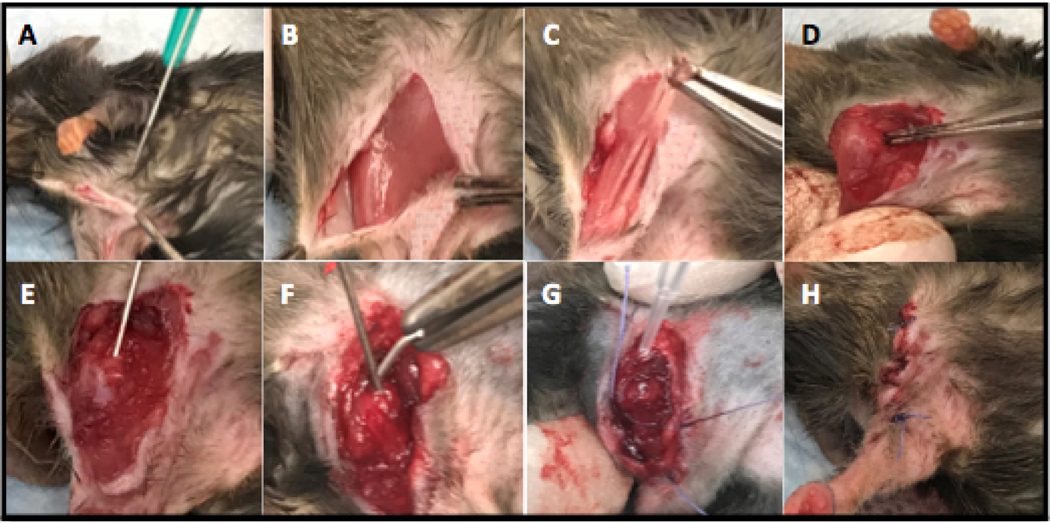

Figure 1. Surgical Procedure (Right Arm).

(A) A midline incision was made extending laterally over the deltoid. (B) The delto-pectoral groove was exposed. (C) The pectoralis muscle was dissected away from the humerus. (D) Posterior pressure was applied to an externally rotated and extended humerus to expose and anteriorly sublux the shoulder joint. (E) Using a 25g needle, the head of the humerus was reamed to make a canal for implant placement. (F) A 0.6mm wide steel implant (5mm in length) with a slight 15-degree bend at the most proximal end (1mm) was implanted into the humerus. (G) Deep sutures were placed prior to inoculation and 2ul of bioluminescent Xen-36 S. aureus was added to the exposed end of the implant. (H) Deep and superficial layers were closed with 5–0 Vicryl sutures.

Implant placement was confirmed via AP and Lateral X-ray on POD 0 (Faxitron LX-60 DC-12 imaging system) as seen in Figure 2. All surgeries performed on the same day utilized the same bacterial stock.

Figure 2. X-ray Confirmation of Implant Placement.

(A) AP view showing implant placement within the humerus. (B) Lateral view confirming implant placement within the shoulder joint space.

Quantification of S. aureus Xen-36 with In Vivo Bioluminescence Imaging

Mice were anesthetized via inhalation isoflurane (2%). In vivo bioluminescence imaging was performed using either the IVIS Lumina II or IVIS Spectrum-CT (PerkinElmer).21 Images were obtained on postoperative days (POD) 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 18, 21, 28, 35, and 42. 3,9,11,30 Bioluminescent data sets were presented via pseudocolor scale overlaid on a grayscale photograph of mice and quantified as mean maximum flux (photons per second (s) per cm2 per steradian (sr) [p/s/cm2/sr]) within a standard circular region of interest (~20,000 pixels) using Living Image software (PerkinElmer).

Validation of the Model with Bacterial CFU Counts

In order to validate the bioluminescence signal, which represents a strong correlate measure of bacterial burden, bacteria adherent to the implants and the surrounding soft tissue were quantified at the conclusion of the experiment (POD 42).3 Bacteria were removed from the implant via sonication in 500uL of 0.3% Tween-80 in TSB for 15 min followed by vortex for 2 min as previously described.8 In addition, bacteria in the surrounding tissue were measured by homogenizing the surrounding muscle and proximal humerus (Pro200H Series homogenizer; Pro Scientific). The number of bacterial CFUs that were adherent to the implant and in the surrounding tissue was determined by counting individual colonies after overnight culture, and were expressed as CFUs/mL.

Weekly X-ray Monitoring for Osteolysis

In order to assess for osteolysis and radiographic loosening, weekly AP X-rays were obtained (POD 0, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42) for all groups. Two mice per group (6 total) were followed throughout the experiment. All radiographs were made using a Quados Faxitron LX-60 Cabinet radiography system with a variable kV point projection x-ray source and digital imaging system (Cross Technologies) as detailed in prior studies.30

Live-Dead Confocal Microscopy

Implants from the infected e3 group and the sterile saline group were assessed on POD 42 with Live-Dead Cell Viability Assays (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Canoga Park, CA, USA), which fluorescently stains for living and dead bacteria based on the integrity of the cell membrane. Green fluorescence represented an intact cell membrane (Live). Red fluorescence represented a ruptured cell membrane (Dead). Orange fluorescence represented an overlap of the two. Specimens were analyzed and photomicrographs were recorded using the Leica DMi8 Confocal Microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA).

Preparation of Histological Sections

In order to assess the microscopic cellular architecture following infection, histology samples were obtained for both e3 and sterile groups on POD 42. The humerus was dislocated at the elbow and dissected away from all connecting tissues. The implant was removed, the sample was placed in a cassette, and suspended in formalin for 24h. The sample was then washed with deionized water for 15 min, and placed in 70% ethanol for 24 additional hours. Samples were then sent to the UCLA Department of Pathology for decalcification and paraffin embedment, per standard protocol. Samples were stained appropriately and received 2 weeks later.

Targeting S. aureus Xen-36 Biofilms on Infected Implants using the Human Monoclonal Antibody 1D9 Fluorescently Labeled with NIR680

Using methods published by our group to better visualize biofilm/chronic infections of spinal hardware, the shoulder model was utilized in efforts to best mimic and visualize SII in the clinical setting via targeted fluorescent imaging using e3 dosing.24,33,35 Mice with established S. aureus Xen-36 SII, as well as sterile control animals, were injected via their tail vein with the fluorescently labeled Staphylococcal targeting probe, 1D9–680. Each mouse received 0.1 μg of the 1D9–680 antibody in 40 μl DMSO. Eight mice with confirmed SII on POD 7 and 4 sterile mice were each injected. 48 hours after injection, FLI was performed using the IVIS Spectrum-CT (PerkinElmer) to detect fluorescence (excitation: 675 nm, emission: 720 nm). Again, we used the Living-Image Software (PerkinElmer) for image and data analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Each experimental group had at least six mice based on previous protocols, which showed that a minimum of six animals per group was necessary to obtain statistical significance at the p<0.05 level.3,9,11,30 Student’s t-test was used to compare data between two groups and ANOVA was used to compare data between three or more groups. Data was represented as mean standard error of the mean (SEM). A mixed effects regression model (random intercept model) was used to determine whether the longitudinal effects seen in both infected groups were statistically significant or not. The model included an interaction between the three groups (Infected Group e3, Infected Group e4, and the Sterile Group) and postoperative time (POD 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 18, 21, 25, 28, 35, 42) with all lower order effects included. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata-14 Statistical Software (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LP).

Results

In Vivo Bioluminescence of a Shoulder Implant Infection

Bioluminescent signal intensities are shown in Figures 3A/B. Both Infected Groups e3 and e4’s signal intensity peaked between POD 5–7, with each infected group emitting signal higher than the Sterile Group throughout the entirety of the experiment.

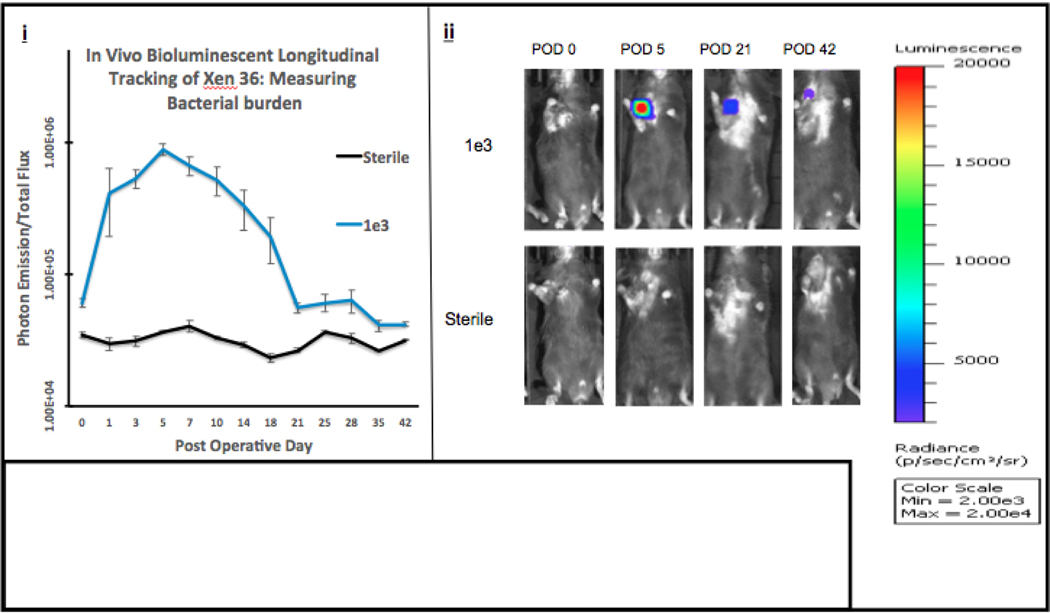

Figure 3A. Quantifying Bacterial Burden.

(i) In Vivo Longitudinal Tracking of Xen 36: Measuring Bacterial Burden Using Photon Emission. Data from the IVIS Lumina was obtained and plotted. Averages of each group with respect to the POD (postoperative day) were used to produce the curve (photons/sec/cm3/sr). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. (ii) Visualizations of peak photon emissions and intensities are shown for each group. Infected Group e3 was inoculated with 1,000 bacterial cells and compared to the Sterile Group which received sterile saline. Images are shown through POD 42, with peak photon emission on POD 5.

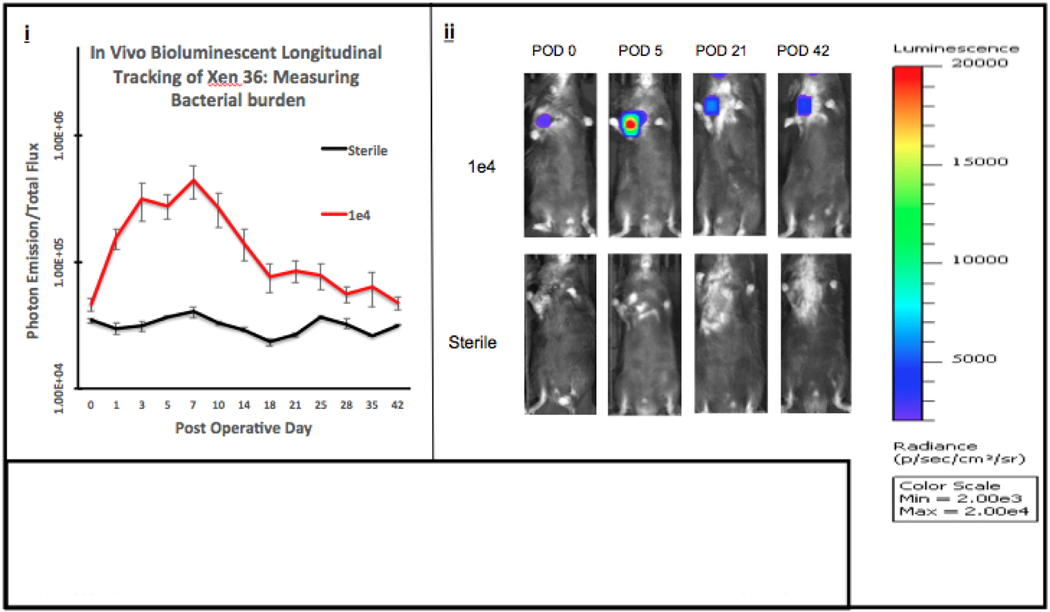

Figure 3B. Quantifying Bacterial Burden.

(i) In Vivo Longitudinal Tracking of Xen 36: Measuring Bacterial Burden Using Photon Emission. Data from the IVIS Lumina was obtained and plotted. Averages of each group with respect to the POD (postoperative day) were used to produce the curve (photons/sec/cm3/sr). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. (ii) Visualizations of peak photon emissions and intensities are shown for each group. Infected Group e4 was inoculated with 10,000 bacterial cells and compared to the Sterile Group which received sterile saline. Images are shown through POD 42, with peak photon emission between POD 7.

These intensities were averaged with respect to the standard error of the mean and plotted to produce the longitudinal curve shown in Figure 3A/B (i). The mixed effects regression model, used to analyze the differences in bacterial burden measured by photon emission between all groups and across all postoperative time points, reached statistical significance from POD 0–42 (p<0.001). Furthermore, when comparing infected groups using the mixed effects regression model, there is no difference between groups e3 and e4 (p = 0.0795). In addition, when comparing Infected Group e3 to the Sterile Group, there is a statistically significant difference between groups with respect to time (p = 0.0012). Similarly, when comparing Infected Group e4 to the Sterile Group, there is also a statistically significant difference between groups with respect to time (p<0.001).

Comparison of Bioluminescence with CFU Harvest

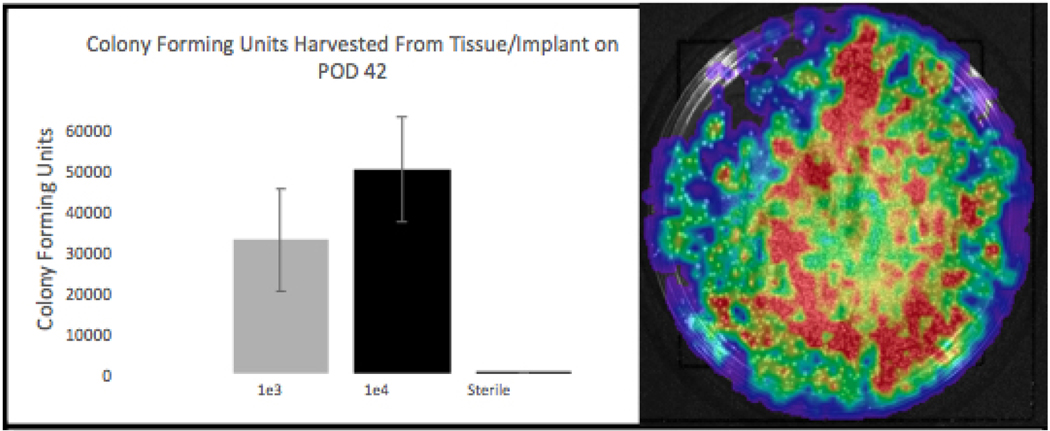

The accuracy of the longitudinal noninvasive imaging was confirmed with CFU counts from the implant and surrounding tissue on POD 42 (Figure 4). Average CFUs of 33000, 50000, and 10 were obtained for the infected e3, e4, and sterile groups, respectively (A). CFUs were confirmed as bioluminescent by repeat IVIS imaging for photon emission (B). T-test analysis comparing the Infected Group e3 to the Sterile Group shows a significant difference (p = 0.0215) between groups. Likewise, t-test analysis comparing the Infected Group e4 to the Sterile Group shows a significant difference (p = 0.0058) between groups. A difference between e3 and e4 infected groups was also seen (p = 0.0002) despite overlapping error bars.

Figure 4. POD 42 Colony Forming Unit (CFU) Harvest from Tissue and Implant.

(A) Shows Infected Groups e3, e4, and the Sterile Group’s respective average CFU data; representing the amount of Xen-36 harvested from these sites 42 days after initial operation. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. (B) IVIS Lumina imaging to confirm growth of Xen-36 from CFU harvest.

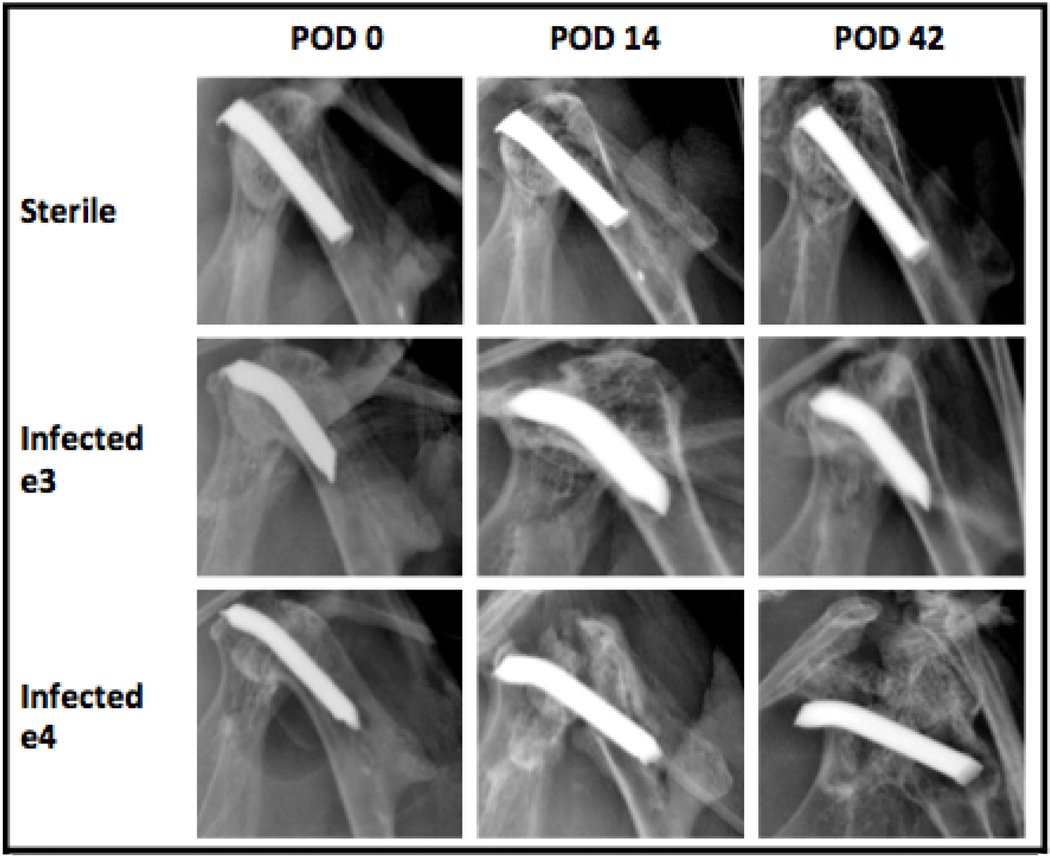

X-ray Analysis to Monitor Onset of Osteolysis

Weekly X-rays were conducted for each respective group in order to monitor for the development of implant loosening as seen in Figure 5. The sterile group showed no evidence of osteolysis throughout the entirety of the experiment. Infected group e3 developed mild osteolysis and evidence of radiographic implant loosening on POD 14, which remained constant through POD 42. Infected group e4 also developed osteolysis on POD 14, which progressed to severe bone loss and complete destruction of the shoulder joint by POD 42. All implants have a proximal bend, with the apparent absence in the sterile mice due to the slight differences in the rotation of the humerus during image acquisition.

Figure 5. Longitudinal Monitoring of Osteolytic Changes.

X-rays taken every week (POD 0, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42) from the AP view. All 3 groups are shown, with osteolytic changes noted in both infected groups on POD 14. Catastrophic osteomyelitis was noted in Infected Group e4 on POD 42.

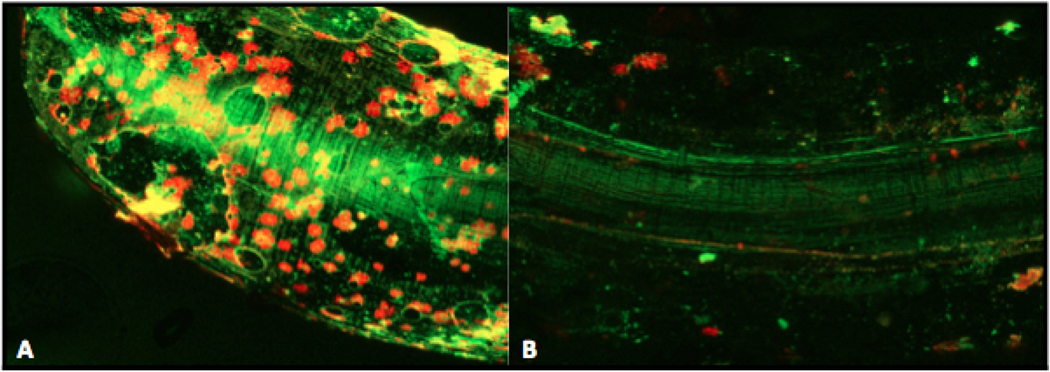

Live-Dead Confocal Microscopy

Fluorescent confocal microscopy revealed extensive green (live) and red (dead) signal around the infected e3 implant, with biofilm surrounding the implant artifact (bright green) as seen in Figure 6. The sterile group showed minimal fluorescence, with the same implant artifact mentioned above.

Figure 6. Live-Dead Imaging Using Confocal Microscopy and Fluorescent Stain.

Implants were removed in sterile fashion from Infected Group e3 and the Sterile Group, then placed in dying solution for 15 min. GREEN represents bacteria with an intact cell membrane (living), whereas RED represents bacteria with a ruptured cell membrane (dead). Orange represents an overlap. Central bright green image represents artifact from the light reflecting off the implant. The surrounding of this artifact represents biofilm formation on an infected implant (A), and lack thereof on a sterile implant (B).

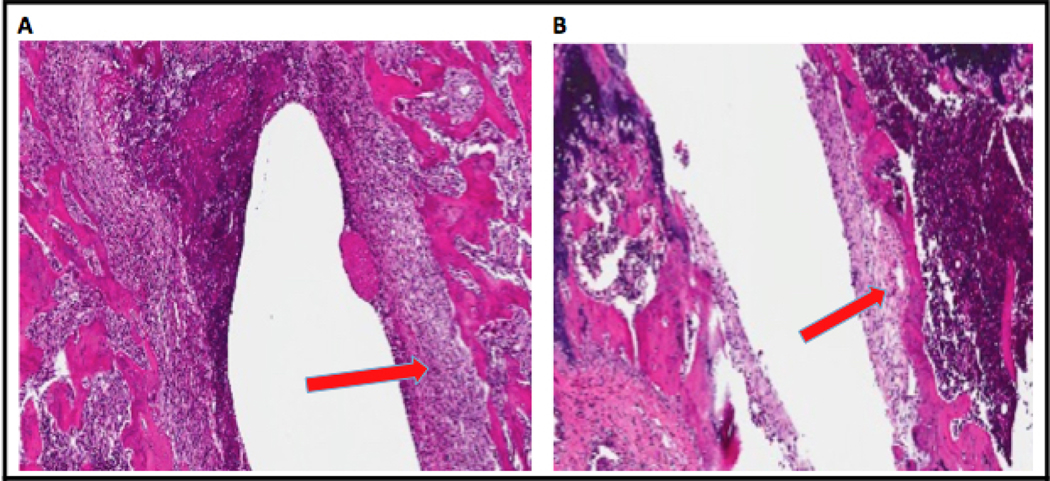

Ex Vivo Histological Evaluation

Histological evaluation was conducted on POD 42 for both the infected e3 and sterile groups (Figure 7). In the infected e3 group, evidence of capsule formation and thickening exists surrounding the canal where the implant was placed. The same magnitude of capsule formation is not seen in the sterile group.

Figure 7. Histology of the Head of the Humerus After Implant Explantation.

(A) Humerus from Infected Group e3 shows formation of thicker capsule surrounding the canal left by the implant after explantation. (B) Humerus from the Sterile Group shows minimal capsule formation after pin explantation.

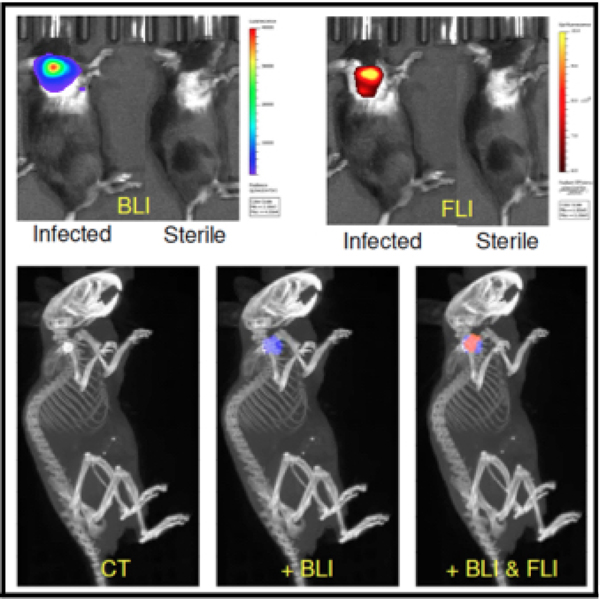

In Vivo Confirmation of Staphylococcal Antibody Probe Targeting Using Combined Bioluminescent & Fluorescent Real-Time Imaging

As shown previously in our spinal implant infection model,35 the fluorescently labeled staphylococcal targeting probe, 1D9–680, specifically targeted S. aureus Xen-36 biofilm infections in our mouse shoulder model (Figure 8). Both 2D and 3D optical imaging, bioluminescence and fluorescence, were performed on the e3 group of animals at POD 9 using an IVIS Spectrum-CT. Due to the high sensitivity and spectral unmixing capabilities of this system, we were able to three-dimensionally reconstruct both bioluminescent and fluorescent signals emanating from within these mice. Moreover, using the CT component of this machine we could accurately visualize the anatomical position of the infected implant and show that both the bioluminescent S. aureus and fluorescent probe were associated/coregistered with this implant.

Figure 8. 2D and 3D optical imaging to confirm fluorescent probe targeting of bioluminescent S. aureus implant infections.

Mice with POD 7 bioluminescent S. aureus infected or sterile shoulder implants were intravenously injected with fluorescently labelled 1D9–680 staphylococcal targeting antibody probe. 48h post-injection of the probe, animals were imaged both two- and three-dimensionally in the IVIS Spectrum-CT, showing that the probe could readily delineate between infected and sterile implants. CT co-registration showed both bioluminescent S. aureus and fluorescent probe to be associated with the implant in the shoulder.

Discussion

Our study sought to establish a longitudinal, non-invasive, and reproducible mouse model of SII using bioluminescent S. aureus Xen-36 through optical imaging technology. Both infected groups (low inoculum e3 and high inoculum e4) demonstrated a statistically significant increase in bacterial burden compared to the sterile group as measured by photon emission/bioluminescence (p<0.001, Figures 3). There was no statistical difference between the bioluminescence of the high inoculum e4 group and the low inoculum e3 group, (p = 0.0795). Both e3 and e4 groups demonstrated peak bioluminescence at POD 5 and 7 respectively, and maintained higher levels of bacterial bioluminescence than the sterile group throughout the experiment to POD 42. Furthermore, with respect to CFU harvest, both infected groups grew significantly more colonies on average when compared to the sterile group (e3 p = 0.0215; e4 p = 0.0058, Figure 4). There were significantly higher average CFUs for the e4 group when compared to the e3 group (p = 0.0002). This data indicates that both the high and low inoculum groups establish true chronic infection through POD 42. Moreover, noninvasive bioluminescent imaging used in this experiment consistently and effectively distinguished between sterile and infected groups, both acutely and chronically. CFU counts further confirm the findings of the IVIS imaging system, while elucidating minor differences between colony counts for the e3 and e4 groups (Figure 4).

It is important to note that the luminescence intensity seen on POD 42 in Figure 3 A/B (i) is explained by the fact that bacterial metabolic activity declines from weeks 2–4 until it achieves chronicity.3,9,11,30 Initially, bacteria are in a highly active state due to the metabolically enriched postoperative environment. The decline from weeks 2–4 is due to a number of factors, including activation of the host’s adaptive immune system, as well as bacterial quiescence. When bacteria produce biofilm, they form a protective barrier, isolating them from the host immune system and antibiotics, all while significantly decreasing their metabolic activity.3 Our bioluminescent animal model is predicated on our ability to measure metabolically active bacteria.3 Thus, as the active bacteria are removed by the immune system, and more bacteria become quiescent, we see a corresponding decline in bioluminescent activity.3 However, since not all of the bacteria are eliminated, a new baseline representing the remaining biofilm-protected bacteria on the implant is established. This baseline is still above sterile levels as seen in Figure 3A/B (i). Distinguishing significant differences in bacterial burden at this indolent level is not possible. Therefore, CFU analysis is used to free bacteria from their protective layers and visualize colonies on growth media. Here, significant differences in bacterial presence can be seen as stated prior (Figure 4).

An interesting and important difference between the low inoculum e3 and the high inoculum e4 groups was found when monitoring for the development of osteolysis and radiographic loosening. The high inoculum e4 group showed catastrophic failure of the bone-implant interface by POD 42 (Figure 5). In contrast, the low inoculum e3 group developed radiographic signs of osteolysis by POD 14, which remained constant throughout the remainder of the experiment. As such, our study is able to model two pathophysiologic phenomena by varying the dose of inoculum: (1) A chronic indolent SII with mild osteolysis and an intact shoulder joint, represented by the infected low inoculum group e3, and (2) A catastrophic failure with severe osteolysis +/− failure of the shoulder implant secondary to immense bacterial burden, represented by the infected high inoculum group e4. This finding is unique, and not yet described in prior models. Given these findings, we argue that the low inoculum e3 group serves as the best model for what is typically seen in the clinical setting; a mildly symptomatic patient presenting ambiguously with indirect evidence of infection, complicating decision making with regard to medical and surgical management.7,20,23 As such, comparisons in subsequent experimental procedures were conducted using only e3 and sterile groups.

Qualitative measures (Live-Dead and Histology) were used to further elucidate characteristics of the model low inoculum e3 group. Live-Dead confocal microscopy demonstrated findings consistent with biofilm formation on the explanted implant for the infected low inoculum e3 group, suggesting the chronic infection was due to persistent bacterial presence on the implant (Figure 6). Furthermore, thick encapsulation of the implant canal seen on histology for the infected e3 group suggests that chronic inflammatory cells were recruited to subdue the infectious burden, which is consistent with findings of osteomyelitis (Figure 7). These histological findings, in addition to the aforementioned radiographic findings, demonstrate a functional and longitudinal model of SII, with progression to findings of chronic osteomyelitis.

Our model can serve as an avenue to study new antimicrobial prevention strategies with respect to SII and osteomyelitis. From antibiotic therapy to preventative polymer coatings, multiple different therapeutic modalities can be tested using this model.3,9,11,30 While similar models study shoulder infections, no other animal model exists where in vivo bacterial burden is longitudinally monitored in real time without subject sacrifice.2,10,13,19 Perhaps most compelling, this model was used to confirm the viability of 1D9–680, a fluorescent S. aureus targeting probe, to accurately identify low-grade biofilm-associated infection (Figure 8). This is of seminal importance as it 1) establishes the viability of the model as a translational system, not reliant on bioluminescent bacteria, but one that could be eventually translated to native strains of infection; and, 2) introduces the capacity for optical imaging of low-grade, residual bacteria after insufficient débridement. Future adaptations of this model will attempt to translate our findings to improve diagnosis and treatment of SII in clinical practice. Furthermore, with ongoing efforts being made to adapt this model to include the primary pathogen in SII, P. acnes, this model will not only serve to strengthen literature regarding implant infection prevention, but also to best mimic periprosthetic SII in clinical settings with respect to pathogenesis.

There are several limitations to our study. We recognize that, clinically, total shoulder arthroplasty involves modifications to both the humerus and glenoid and that our model is a simplification of the steps typically involved in human shoulder implant surgery. Additionally, other metals or materials may be implanted in human shoulder surgery that may have different susceptibilities to bacterial infection. There is also the possibility that the braided Vicryl suture used during wound closure could serve as a nidus for infection (Figure 1). However, in prior studies using three-dimensional optical imaging we have shown that bioluminescence is often away from the incision line and persistent well after suture dissolution making this an unlikely concern.3,9,11,30 We also have not evaluated modalities for monitoring host immunity, noting only swelling and decreased mobility as markers of an inflammatory response. However, given statistically significant differences between infected and sterile groups using multiple experimental modalities, it is safe to assume that the direct measurements of bacterial burden presented above are more than adequate.3 Importantly, we recognize that P. acnes is the most common etiologic agent for SII clinically, despite several articles arguing for S. aureus predominance.1,4,20,22,27,34 The low virulence and replication rate of P. acnes makes it difficult to transform this bacterium genetically to form a bioluminescent operon in the same manner as S. aureus, restricting the ability to study infections longitudinally and noninvasively.8,12 Thus, we developed a model of SII using S. aureus, in accordance with similar studies our lab has produced in prior years.1,3,4,9,11,20,22,27,30,35 Nonetheless, the development of this model will allow us to further our work by expanding to new bacterial species that are more specific to the shoulder (e.g. P. acnes). Additionally, other established models in our lab have found unexpected differences in bacterial activity, implant reactivity, and response to antibiotics. Unfortunately, we cannot offer an explanation whether our findings relate to biomechanics, physiology, joint perfusion, genetics or some combination of all of those factors; however, we hope to use this new model, in conjunction with other models, to provide a more robust comparison of the efficacy of our treatment strategies in implant infection management.

Conclusion

In summary, a chronic indolent SII model was established with an inoculation of 1*103 bioluminescent S. aureus Xen-36. A model of catastrophic failure secondary to severe osteolysis was also established with an inoculation of 1*104. Furthermore, the 1D9–680 fluorescent S. aureus targeting probe accurately identified low-grade biofilm-associated infection, allowing for important clinical translation potential for diagnosing infection and image-guided débridement.

We believe this study successfully demonstrates a new in vivo mouse model of SII, capable of producing real-time, quantifiable data on bacterial burden through bioluminescence and optical imagery. We anticipate this model will be used in the future to evaluate strategies in treating implant related shoulder infection (with future studies focusing on P. acnes), including systemic antibiotic therapy, antibiotic-loaded beads, antibiotic-coated implants, and antibiotic powder. In addition, the establishment of this mouse model may also be used to analyze the mechanisms and pathways of the host immune response to SII in order to better understand how and why shoulder implants behave differently than periprosthetic infections of other joint spaces.

Supplementary Material

VIDEO FILE LEGEND

Adjunct to Figure 8: 3D optical colocalization to confirm fluorescent probe targeting of bioluminescent S. aureus implant infections.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge David McAllister, Vishal Hegde, Amanda Loftin, Daniel Johansen, Molly Sprague, Benjamin Kelly, Gideon Blumstein, Zachary Burke, and Francisco Romero Pastrana for their contributions to the project. We would additionally like to recognize University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) PRIME & CTSI, the David Geffen Medical Scholars program, and the Dean’s Leadership in Health and Science Scholarship committee. Lastly, we would like to thank the laboratory of Dr. Kang Ting at the UCLA School of Dentistry, Section of Orthodontics, to provide the equipment to obtain implant x-ray data. Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Number T32AR059033 and Award Number 5K08AR069112-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Confocal laser scanning microscopy was performed at the CNSI Advanced Light Microscopy/Spectroscopy Shared Resource Facility at UCLA, supported with funding from NIH-NCRR shared resources grant (CJX1-443835-WS-29646) and NSF Major Research Instrumentation grant (CHE-0722519).

Footnotes

Ethics approval received from ARC (Animal Research Committee) at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The UCLA Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee (ARC) approved all animal research submitted below (ARC# 2008–112-21L) with regards to both forelimb/hindlimb murine surgery and research.

N.M.B. has or may receive payments or benefits from the National Institute of Health. J.M.vD. reports that he has the following competing interests relevant to this study: he has filed a patent application on the use of 1D9, which is owned by his employer University Medical Center Groningen. K.P.F. reports that he is an employee of PerkinElmer, Inc., manufacturer of optical and CT imaging equipment. The remaining authors certify that they have no commercial associations that may pose a conflict of interest with this submission. Illustrations must be published in color.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Achermann Y, Sahin F, Schwyzer HK, Kolling C, Wust J, Vogt M. Characteristics and outcome of 16 periprosthetic shoulder joint infections. Infection 2013;41(3):613–20. doi: 10.1007/s15010-012-0360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell R, Taub P, Cagle P, Flatow EL, Andarawis-Puri N. Development of a mouse model of supraspinatus tendon insertion site healing. J Orthop Res 2015;33(1):25–32. doi: 10.1002/jor.22727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernthal NM, Stavrakis AI, Billi F, Cho JS, Kremen TJ, Simon SI, et al. A mouse model of post-arthroplasty Staphylococcus aureus joint infection to evaluate in vivo the efficacy of antimicrobial implant coatings. PloS one 2010;5(9):e12580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohsali KI, Wirth MA, and Rockwood CA Jr. Complications of total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88(10):2279–92. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancienne JM, Brockmeier SF, Gulotta LV, Dines DM, Werner BC. Ambulatory Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Comprehensive Analysis of Current Trends, Complications, Readmissions, and Costs. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017;99(8):629–637. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung EV, Sperling JW, and Cofield RH. Infection associated with hematoma formation after shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008;466(6):1363–7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0226-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coste JS, Reig S, Trojani C, Berg M, Walch G, Boileau P. The management of infection in arthroplasty of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004;86(1):65–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B1.14089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodson CC, Craig EV, Cordasco FA, Dines DM, Dines JS, Dicarlo E, et al. Propionibacterium acnes infection after shoulder arthroplasty: a diagnostic challenge. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010;19(2):303–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dworsky EM, Hedge V, Loftin AH, Richman S, Hu Y, Lord E, et al. Novel in vivo mouse model of implant related spine infection. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 2017;35(1):193–199. doi: 10.1002/jor.23273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehrensberger MT, Tobias ME, Nodzo SR, Hansen LA, Luke-Marshall NR, Cole RF, et al. Cathodic voltage-controlled electrical stimulation of titanium implants as treatment for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus periprosthetic infections. Biomaterials 2015;41:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis KP, Joh D, Bellinger-Kawahara C, Hawkinson MJ, Purchio TF, Contag PR. Monitoring bioluminescent Staphylococcus aureus infections in living mice using a novel luxABCDE construct. Infection and immunity 2000;68(6):3594–3600. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3594-3600.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grosso MJ, Frangiamore SJ, Ricchetti ET, Bauer TW, Iannotti JP. Sensitivity of frozen section histology for identifying Propionibacterium acnes infections in revision shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96(6):442–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo Y, Guo J, Bai D, Wang H, Zheng X, Guo W, et al. Hemiarthroplasty of the shoulder joint using a custom-designed high-density nano-hydroxyapatite/polyamide prosthesis with a polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel humeral head surface in rabbits. Artif Organs 2014;38(7):580–6. doi: 0.1111/aor.12257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooper AC. Skeletal dimensions in senescent laboratory mice. Gerontology 1983;29(4):221–5. doi: 10.1159/000213120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howard DR, Kazemi N, Rubenstein WJ, Hartwell MJ, Poeran J, Chang AL, et al. Cost-benefit analysis of routine pathology examination in primary shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2017;(4):674–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. 2011. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;21;93(24):2249–54. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurtz SM, Lau E, Watson H, Schmier JK, Parvizi J. Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the United States. J Arthroplasty 2012;27(8 Suppl):61–5.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lind PM, Lind L, Larsson S, Orberg J. Torsional testing and peripheral quantitative computed tomography in rat humerus. Bone 2001;29(3):265–70. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(01)00576-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oki S, Shirasawa H, Yoda M, Matsumura M, Tohmonda T, Yuasa K, et al. Generation and characterization of a novel shoulder contracture mouse model. J Orthop Res 2015;33(11):1732–8. doi: 10.1002/jor.22943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pottinger P, Butler-Wu S, Neradilek MD, Merritt A, Bertelsen A, Jette JL, et al. Prognostic factors for bacterial cultures positive for Propionibacterium acnes and other organisms in a large series of revision shoulder arthroplasties performed for stiffness, pain, or loosening. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94(22): p. 2075–83. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pribaz JR, Bernthal NM, Billi F, Cho JS, Ramos RI, Guo Y, et al. Mouse model of chronic post-arthroplasty infection: noninvasive in vivo bioluminescence imaging to monitor bacterial burden for long-term study. Journal of Orthopaedic Research: Official Publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society 2012;30(3):335–340. doi: 10.1002/jor.21519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richards J, Inacio MC, Beckett M, Navarro RA, Singh A, Dillon MT, et al. Patient and Procedure-specific Risk Factors for Deep Infection After Primary Shoulder Arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 2014;472(9):2809–2815. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3696-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romano CL, Borens O, Monti L, Meani E, Stuyck J. What treatment for periprosthetic shoulder infection? Results from a multicentre retrospective series. Int Orthop 2012. 36(5):1011–7. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1467-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Romero PF, Thompson JM, Heuker M, Hoekstra H, Dillen CA, Ortines RV, et al. Noninvasive optical and nuclear imaging of Staphylococcus-specific infection with a human monoclonal antibody-based probe. Virulence. 2018. Jan 1;9(1):262–272. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2017.1403004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schairer WW, Nwachukwu BU, Lyman S, Craig EV, Gulotta LV. National utilization of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015;(1):91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schairer WW, Zhang AL, and Feeley BT. Hospital readmissions after primary shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014;23(9):1349–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh JA, Sperling JW, Schleck C, Harmsen WS, Cofield RH. Periprosthetic infections after total shoulder arthroplasty: a 33-year perspective. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012;21(11):1534–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Somerson JS, Hsu JE, Neradilek MB, Matsen FA 3rd. Analysis of 4063 complications of shoulder arthroplasty reported to the US Food and Drug Administration from 2012 to 2016. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2018;27(11):1978–1986. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sperling JW, Kozak TK, Hanssen AD, Cofield RH. Infection after shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001;382:206–16. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200101000-00028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stavrakis AI, Zhu S, Hedge V, Loftin AH, Ashbaugh AG, Niska JA, et al. In Vivo Efficacy of a “Smart” Antimicrobial Implant Coating. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016;98(14):1183–1189. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.01273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Topolski MS, Chin PY, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Revision shoulder arthroplasty with positive intraoperative cultures: the value of preoperative studies and intraoperative histology. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2006;15(4):402–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2005.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Updegrove GF, Armstrong AD, and Kim HM. Preoperative and intraoperative infection workup in apparently aseptic revision shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015;24(3):491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van den Berg S, Bonarius HP, van Kessel KP, Elsinga GS, Kooi N, Westra H, et al. A human monoclonal antibody targeting the conserved staphylococcal antigen IsaA protects mice against Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Int J Med Microbiol. 2015. Jan;305(1):55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zavala JA, Clark JC, Kissenberth MJ, Tolan SJ, Hawkins RJ. Management of deep infection after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a case series. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012;21(10):1310–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zoller SD, Park HY, Olafsen T, Zamilpa C, Burke ZD, Blumstein G, et al. Multimodal imaging guides surgical management in a preclinical spinal implant infection model. JCI Insight. 2019. Feb 7;4(3). pii: 124813. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.124813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

VIDEO FILE LEGEND

Adjunct to Figure 8: 3D optical colocalization to confirm fluorescent probe targeting of bioluminescent S. aureus implant infections.