Abstract

Background and Aims

In the subfamily Poöideae (Poaceae), certain grass species possess anti-herbivore alkaloids synthesized by fungal endophytes that belong to the genus Epichloë (Clavicipitaceae). The protective role of these symbiotic endophytes can vary, depending on alkaloid concentrations within specific plant–endophyte associations and plant parts.

Methods

We conducted a literature review to identify articles containing alkaloid concentration data for various plant parts in six important pasture species, Lolium arundinaceum, Lolium perenne, Lolium pratense, Lolium multiflorum|Lolium rigidum and Festuca rubra, associated with their common endophytes. We considered the alkaloids lolines (1-aminopyrrolizidines), peramine (pyrrolopyrazines), ergovaline (ergot alkaloids) and lolitrem B (indole-diterpenes). While all these alkaloids have shown bioactivity against insect herbivores, ergovaline and lolitrem B are harmful for mammals.

Key Results

Loline alkaloid levels were higher in the perennial grasses L. pratense and L. arundinaceum compared to the annual species L. multiflorum and L. rigidum, and higher in reproductive tissues than in vegetative structures. This is probably due to the greater biomass accumulation in perennial species that can result in higher endophyte mycelial biomass. Peramine concentrations were higher in L. perenne than in L. arundinaceum and not affected by plant part. This can be attributed to the high within-plant mobility of peramine. Ergovaline and lolitrem B, both hydrophobic compounds, were associated with plant parts where fungal mycelium is usually present, and their concentrations were higher in plant reproductive tissues. Only loline alkaloid data were sufficient for below-ground tissue analyses and concentrations were lower than in above-ground parts.

Conclusions

Our study provides a comprehensive synthesis of fungal alkaloid variation across host grasses and plant parts, essential for understanding the endophyte-conferred defence extent. The patterns can be understood by considering endophyte growth within the plant and alkaloid mobility. Our study identifies research gaps, including the limited documentation of alkaloid presence in roots and the need to investigate the influence of different environmental conditions.

Keywords: Symbiosis, defensive mutualism, herbivory resistance, grass, secondary metabolites, plant–endophyte interaction, plant–herbivore interaction

INTRODUCTION

Plant phenotypes are shaped through evolution in response to selection pressures imposed by biotic and abiotic factors, and herbivory is one of the most relevant forces (Agrawal et al., 2012). The selected defensive traits in plant phenotypes under herbivory may not necessarily be encoded in plant genomes but in their symbiotic microorganisms (Ellers et al., 2012; Panaccione et al., 2014). Certain grass species within the subfamily Poöideae (family Poaceae) are endowed with anti-herbivore alkaloids that are synthesized by fungal endophytes of the genus Epichloë (family Clavicipitaceae) (Schardl et al., 2004; Leuchtmann et al., 2014). Within the plant–Epichloë symbiosis, some are considered defensive mutualisms (Clay, 1988; Wilkinson et al., 2000; Schardl et al., 2012, 2013a; Panaccione et al., 2014; Bastias et al., 2017a). Still, the effectiveness of the endophyte-mediated defensive mechanism varies across plant–endophyte associations and shows a significant context-dependency (Saikkonen et al., 2010; Ueno et al., 2016; Bastias et al., 2017b; Bastías and Gundel, 2023). This variation may be attributed, in part, to differences in alkaloid contents among plant species, and among plant organs or parts.

Epichloë species differ in ploidy levels, reproductive systems, transmission modes and symptoms on plants. These endophytes grow hyphae in the intercellular spaces of aerial plant parts closely associated with meristematic buds (Christensen et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2017). Most – but not all (e.g. Epichloë festucae var. lolii in Lolium perenne) – haploid species can reproduce sexually by developing fruiting bodies (stromata) that release meiotic spores as a mode of horizontal transmission, and cause abortion of host reproductive structures (choke disease) (e.g. Epichloë typhina in L. perenne) (Schardl et al., 2013a, 2023; Tadych et al., 2014). Alternatively, Epichloë species are interspecific hybrids of two or three haploid species which are, in consequence, diploid and triploid, respectively. These hybrid endophytes reproduce asexually by growing hyphae in developing seeds (vertical transmission), and cause no symptoms on plant hosts (e.g. Epichloë coenophiala in Lolium arundinaceum) (Gundel et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017). Some haploid species of Epichloë combine both sexual and asexual reproduction systems, and vertical and horizontal transmission modes (e.g. Epichloë festucae in Festuca rubra) (Schardl, 2010). While there have been some exceptions reported (e.g. Mc Cargo et al., 2014; Soto-Barajas et al., 2019), these symbiotic associations are generally specific, with plant species commonly hosting one or a few fungal species (Schardl et al., 2008; Leuchtmann et al., 2014). The Epichloë-based plant protection against herbivores is largely attributable to alkaloids (Wilkinson et al., 2000; Potter et al., 2008), but it may also involve other endophyte factors, as well as the endophyte-mediated induction of the plant’s immune defence system (Ambrose et al., 2014; Bastias et al., 2017a; Fuchs et al., 2017a; Cibils-Stewart et al., 2022). Though not as well elucidated at the mechanistic level, resistance to pathogens and tolerance to abiotic stress factors (e.g. drought, salinity, ozone) have also been ascribed to the symbiosis with Epichloë species (Nagabhyru et al., 2013; Buckley et al., 2019; Card et al., 2021; Decunta et al., 2021; Ueno et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022; Bastías et al., 2023).

Four major chemical classes of Epichloë-derived alkaloids have been described: (1) 1-aminopyrrolizidines include lolines that, depending on substituents at the C-1 amine, yield different loline alkaloids; (2) pyrrolopyrazines which include the insect feeding deterrent peramine; (3) ergot alkaloids which include ergovaline, a potent toxin in mammalian systems; and (4) indole-diterpenes which include the potent tremorgen lolitrem B (Berry et al., 2019; Schardl et al., 2023). Although other alkaloids have been identified within these major classes (Moore et al., 2015; Finch et al., 2020), we here focus on these four main alkaloids because they are well characterized genetically and functionally (Schardl et al., 2012, 2013b, 2023). The loline alkaloids [N-formylloline (NFL), N-acetylloline (NAL), N-acetylnorloline (NANL) and N-methylloline (NML)] are well known to act as plant chemical defences against herbivorous insects and nematodes through both deterrent and insecticidal effects (Wilkinson et al., 2000; Schardl et al., 2007; Bacetty et al., 2009). Peramine is also known for its anti-feedant effects on insects (Rowan, 1993; Schardl et al., 2012). Ergovaline and lolitrem B are mostly known for their toxic effects on mammals (Gallagher et al., 1981; Young et al., 2005; Guerre, 2015; Caradus et al., 2022). The variation in alkaloid profiles among fungal strains has led to the development of a forage breeding strategy aimed at improving cultivars with endophytes that produce alkaloids with insecticidal effects but not those that are harmful to mammals (Bouton et al., 2002; Gundel et al., 2013). This practice has been mostly performed on the economically important grass species L. arundinaceum (syn. Festuca arundinacea = Schedonorus arundinaceus; common name: tall fescue) and L. perenne (perennial ryegrass) since the common endophytes in earlier cultivars produce ergovaline and/or lolitrem B (Johnson et al., 2013). This is not necessary for other commercially used species such as Lolium pratense (syn. Festuca pratensis; meadow fescue) and the annual ryegrasses Lolium multiflorum and Lolium rigidum (hereafter L. multiflorum|L. rigidum), since their endophytes do not produce alkaloids toxic for mammals or, if they do, as in F. rubra, grasses are mainly used as turf (Pennell et al., 2010; Bylin et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2015).

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the variation in the endophyte-mediated defence in host plants, we reviewed the literature looking for articles that have reported data on alkaloid concentration in six of the most significant temperate pasture and forage grass species: L. arundinaceum, L. perenne, L. pratense, L. multiflorum|L. rigidum and F. rubra, in association with their common endophytes only. The annual ryegrasses L. multiflorum and L. rigidum (L. multiflorum|L. rigidum) are considered together as they both host the same endophyte species (Epichloë occultans) (Moon et al., 2000). Given that the effectiveness of alkaloids as defences against herbivores depends on their levels in the host plant organ when attacked, we were particularly interested in evaluating their variation among plant parts. Since alkaloid concentrations can be altered by either biotic or abiotic environmental conditions (e.g. herbivory, drought) (Bultman et al., 2004; Nagabhyru et al., 2013; Fuchs et al., 2017c; Bubica Bustos et al., 2022), we only included data from plants that grew in the absence of treatments (control condition). We analysed data of the most studied alkaloids (lolines, peramine, ergovaline, and lolitrem B) to address the following questions: (1) How does the concentration of the different alkaloids vary among plant species? (2) How do alkaloid concentrations vary among plant parts? Improving our understanding of the distribution and abundance of Epichloë-derived alkaloids within and among host plants contributes to predicting how endophytes mediate plant interactions with herbivores.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To survey the literature on the main fungal alkaloids produced by Epichloë species (fungal endophytes) in grasses, we conducted a search in the ScopusTM database (www.scopus.com) on 1 December, 2023. The search criterion was organized by combining the following key words and conditionals: epichloë, OR acremonium, OR neotyphodium, AND acetamidopyrrolizidine, OR chanoclavine, OR ergot, OR ergonovine, OR ergovaline, OR lolitrem, OR n-acetylnorloline, OR n-acetylloline, OR n-formylloline, OR paxilline, OR peramine, OR terpendoles, OR terpenes, OR lolines, OR indole-diterpenes. Acremonium was included because, in early works, it was thought to be the genus of the fungal endophytes that were later classified as Epichloë/Neotyphodium. Neotyphodium was included because it was until recently used to classify the anamorphs of Epichloë species, but today all members of this clade are within the genus Epichloë (Leuchtmann et al., 2014). We also screened the reference list of the selected papers to identify other relevant publications that were not detected in the first search. A total of 588 articles were obtained and reviewed to assess their suitability. Another five studies were incorporated due to knowledge of the literature in the line of this work.

To be included in the analysis, studies had to inform measurements of alkaloid concentration in plant tissues of L. arundinaceum, L. pratense, L. perenne, L. multiflorum|L. rigidum or F. rubra. We limited our work to those plant species because they are among the most studied worldwide in relation to Epichloë endophytes (Semmartin et al., 2015). The scientific names of the grasses used in the present study were determined by consulting the Plants of the World Online database (POWO, 2023). Because the fungal endophyte species in the studies were often unspecified, we regarded the plant species as being associated with those endophyte species and strains most commonly identified in the respective host species. In the literature these are denoted as ‘common’, ‘wild-type’ or ‘standard’ strains of E. coenophiala in L. arundinaceum, E. uncinata in L. pratense, E. festucae in F. rubra, E. festucae var. lolii in L. perenne and E. occultans in L. multiflorum|L. rigidum (Leuchtmann et al., 2014). We focused solely on symbiotic associations at the species level, excluding studies that utilized artificial inoculation to establish non-natural symbioses for scientific purposes. Studies presenting values in units that could not be converted to µg g plant DW–1 were discarded. When alkaloid data were presented in figures, they were extracted using the software Graph Grabber (Quintessa Ltd, 2022). Differences in alkaloid levels due to varied analytical methods contribute to the between-study variability. The final database used in the analysis included 623 studies from 104 publications (Table 1). We utilized data from experiments conducted either in pots or in the field. In the latter case, the extant plants could have been either seeded or natural. However, we ensured that the sampled tissue had been pure from the specified plant species and its common endophyte, and had not come from mixtures with different species or endophyte-free plants. In cases of manipulative experiments, we utilized data from control treatments or from endophyte-symbiotic plants that remained untreated.

Table 1.

List of articles that provided data for analysis of variation patterns in the concentrations of the four main fungal alkaloids lolines, peramine, ergovaline and lolitrem B across different plant–Epichloë symbioses. The entire list of references is provided in the Supporting Data Table S1.

| Plant species | Endophyte species | Alkaloid | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Festuca pratensis | Epichloë uncinata | Lolines | Adhikari et al., 2016; Bryant et al., 2010; Bylin et al., 2014; Cagnano et al., 2019; Justus et al., 1997; Popay et al., 2020; Vikuk et al., 2019. |

| Festuca rubra | Epichloë festucae | Ergovaline | Gundel et al., 2018; Jensen et al., 2007; Leuchtmann et al., 2000; Pereira et al., 2021; Tanentzap et al., 2014; Vázquez de Aldana et al., 2004, 2007, 2010, 2020; Yue et al., 1997. |

| Peramine | Leuchtmann et al., 2000; Vázquez de Aldana et al., 2004, 2010, 2020; Yue et al., 1997. | ||

| Lolium multiflorum|Lolium rigidum | Epichloë occultans | Lolines | Bastías et al., 2018, 2019; Gundel et al., 2018; Moore et al., 2015; TePaske et al., 1993; Ueno et al., 2016, 2020. |

| Lolium perenne | Epichloë festucae var. lolii | Lolitrem B | Ball et al., 1997b; Berny et al., 1997; Bluett et al., 1999; Combs et al., 2014; Do Valle Ribeiro et al., 1996; Eerens et al., 1998; Finch et al., 2018; Hahn et al., 2008; Hesse et al., 1999; Hewitt et al., 2020; Hovermale et al., 2001; Keogh et al., 1996; König et al., 2018; Krauss et al., 2020; Lewis et al., 1986; Lowe et al., 2008; Oldenburg et al., 1997; Reddy et al., 2019; Reed et al., 2000; Reed et al., 2011a, b; Repussard et al., 2014b; Soto-Barajas et al., 2017, 2019; Tian et al., 2013; Vassiliadis et al., 2023; van Zijll de Jong et al., 2008. |

| Ergovaline | Bluett et al., 1999; Bultman et al., 2004; Combs et al., 2014; Easton et al., 2002; Eerens et al., 1998; Finch et al., 2018; Hanh et al., 2008; Hesse et al., 1999; Hewitt et al., 2020; Hovermale et al., 2001; Hudson et al., 2021; Krauss et al., 2020; Lane et al., 1997; Leuchtmann et al., 2000; Lowe et al., 2008; Mace et al., 2014; Reed et al., 2000, 2011, 2016a, b; Repussard et al., 2014a; Soto-Barajas et al., 2017, 2019; Spiering et al., 2002; Sutherland et al., 1999; TePaske et al., 1993; Tian et al., 2013; Vassiliadis et al., 2023; van Zijll de Jong et al., 2008. | ||

| Peramine | Ball et al., 1997a; Bluett et al., 1999; Breen et al., 1992; Easton et al., 2002; Eerens et al., 1998; Fuchs et al., 2013; Hesse et al., 1999; Hewitt et al., 2020; Hudson et al., 2021; Keogh et al., 1996; Krauss et al., 2007, 2020; König et al., 2018; Leuchtmann et al., 2000; Lowe et al., 2008; Moore et al., 2015; Reed et al., 2000, 2016; Soto-Barajas et al., 2017, 2019; Spiering et al., 2002; Sutherland et al., 1999; Tian et al., 2013, 2019; Vassiliadis et al., 2023; van Zijll de Jong et al., 2008. | ||

| Lolium arundinaceum | Epichloë coenophiala | Lolines | Baldauf et al., 2011; Belesky et al., 1989, 2009; Brosi et al., 2011; Cibils-Stewart et al., 2023; Dinkins et al., 2023; Helander et al., 2016; Jokela et al., 2016; Leuchtmann et al., 2000; Malinowski et al., 1999; McCulley et al., 2014; Pennell et al., 2010; Petroski et al., 1989; Piano et al., 2005; Popay et al., 2020; Siegrist et al., 2010; Simeone et al., 1998; Simons et al., 2008, TePaske et al., 1993. |

| Ergovaline | Agee et al., 1994; Arechavaleta et al., 1992; Baldauf et al., 2011; Belesky et al., 1989, 2009; Brown et al., 2009; Christensen et al., 1998; Dillard et al., 2019; Garner et al., 1993; Goff et al., 2012; Grote et al., 2023; Jackson et al., 2015; Jensen et al., 2007; Ji et al., 2014; Jokela et al., 2016; Kenyon et al., 2018; Lane et al., 1999; Lea et al., 2014; Leuchtmann et al., 2000; Lyons et al., 1986; McCulley et al., 2014; Najafabadi et al., 2010; Pennell et al., 2010; Petigrosso et al., 2020; Piano et al., 2005; Repussard et al., 2014; Roylance et al., 1994; Salvat et al., 2001; Shelby et al., 1997; Siegrist et al., 2010; Simeone et al., 1998; TePaske et al., 1993; Vazquez de Aldana et al., 2001; Walker et al., 2015; White et al., 2001; Yates et al., 1988; Yue et al., 1997; Zbib et al., 2014. | ||

| Peramine | Baldauf et al., 2011; Cibils-Stewart et al., 2023; Krauss et al., 2020; Leuchtmann et al., 2000; Moore et al., 2015; Roylance et al., 1994; White et al., 2001. |

We considered the alkaloids that are linked to the four main chemical classes: (1) lolines (1-aminopyrrolizidines), (2) peramine (pyrrolopyrazines), (3) ergovaline (ergot alkaloids) and (4) lolitrem B (indole-diterpenes) (Schardl et al., 2023). The biosynthesis of these alkaloids is well characterized at the gene level, and it is likely that intermediate molecules in the pathways to the end products also exhibit bioactive effects on herbivores (Vikuk et al., 2019). In light of this observation, our study focuses on the four thoroughly characterized alkaloids. For the analysis of lolines, we used the sum of the different derivatives (NANL, NFL, NAL) since, in most cases, they were evaluated and/or reported together, and all are responsible for the anti-herbivory effects (Riedell et al., 1991; Jensen et al., 2009). For the analysis of the ergot alkaloids, we found two alternatives, to analyse total ergot alkaloids and/or to analyse the alkaloid ergovaline. Although a substantial number of papers report total ergot alkaloids with no clarification on the specific alkaloids included, we preferred to work with ergovaline to gain precision and because it is well known to have effects on vertebrate and invertebrate herbivores (Potter et al., 2008; Schardl et al., 2023). Therefore, we report the results for ergovaline here. In the case of indole-diterpenes, we considered lolitrem B because it is associated with mammalian toxicosis from Epichloë-infected grasses and is the most commonly measured indole-diterpene in the grasses (Young et al., 2009).

The data were separated by alkaloid class and alkaloid compound and organized into four categories: work code, host species, endophyte species and plant part (Supplementary Dataset ). The host species column includes the most common scientific names for each plant species based on POWO (2023). The fungal species column includes the scientific names of the endophyte species. Based on specialized literature (e.g. Leuchtmann et al., 2014), we used the scientific name of the common endophyte associated with each plant species. The combination of plant and endophyte species determined the grass–Epichloë symbiosis factor. The plant parts in which alkaloids were measured were classified into four distinct categories. The first two categories were below-ground biomass (roots) and above-ground biomass. When possible this category was further divided into vegetative or reproductive. In cases where there was no indication of whether the structures were vegetative or reproductive, we categorized it simply as above-ground biomass. As vegetative structures, we considered tillers, pseudostems and leaves (sheath and blade), while in reproductive structures, we included panicles (or spikes) or seeds. If explicitly indicated, leaves could have been associated with reproductive structures if they were part of a reproductive tiller (as in Ball et al., 1997a). Therefore, our classification does not necessarily mean planta phenological stage. Alkaloid data reported for different species, populations or ecotypes from various locations within the same publication were treated as distinct case studies (sensuKoricheva et al., 2013).

To assess the differences across grass–Epichloë symbioses and plant parts for each alkaloid type, we performed independent linear mixed models (LMMs) with symbiosis and plant part as crossed fixed factors and study case as a random factor by using the lmer function from the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova et al., 2017) in R v.4.0.2 (R Development Core Team, 2022). Relevant model assumptions were analysed for each model using the check_models function from the performance R package (Lüdecke et al., 2021); subsequently, we evaluated significant effects through Wald chi-squared tests. Furthermore, we carried out post-hoc analyses based on multiple pairwise comparisons of least-squares means using the lsmeans function from the emmeans package and cld function from the multcomp package. Data on the alkaloids ergovaline, lolitrem B and peramine were transformed using the function log10(1 + x) to meet model assumptions. This transformation emphasizes variations in smaller values while mitigating variations in larger values and ensures that the result is always greater than or equal to zero. All results are presented with untransformed data.

RESULTS

Overall, concentrations of Epichloë-derived alkaloids differed among plant–endophyte symbioses and/or plant parts (Table 2). Concentrations of lolines varied across symbioses depending on the plant part (Fig. 1), whereas that of peramine varied among symbioses regardless of the plant part (Fig. 2; Table 2). Concentrations of ergovaline varied among symbioses and depended on the plant part (Fig. 3). The concentration of lolitrem B, which was associated only with L. perenne, differed between plant parts (Fig. 4; Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of linear mixed models evaluating the effects of plant–Epichloë symbiosis, plant part and their interaction on the concentrations of the alkaloids lolines, peramine, ergovaline, and lolitrem B. Chi-square statistic values (χ2), degree of freedom (DF) and P-values are shown. Significant P-values are in bold.

| Source | Epichloë-derived alkaloid | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lolines | Peramine | Ergovaline | Lolitrem B | |||||||||

| χ2 | DF | P | χ2 | DF | P | χ2 | DF | P | χ2 | DF | P | |

| Symbiosis (S) | 7.257 | 2 | 0.027 | 8.379 | 2 | 0.015 | 16.835 | 2 | <0.001 | – | – | – |

| Plant part (P) | 19.621 | 3 | <0.001 | 3.141 | 2 | 0.208 | 30.245 | 2 | <0.001 | 15.794 | 2 | <0.001 |

| S × P | 10.071 | 3 | 0.018 | 1.529 | 2 | 0.466 | 22.668 | 3 | <0.001 | – | – | – |

Fig. 1.

Concentration of Epichloë-derived loline alkaloids in different plant–endophyte symbioses (indicated through host species name) and plant parts. The category ‘above-ground’ is used to aggregate all data from studies that did not define the tissue type, either vegetative or reproductive. Points around the boxplots are independent studies (N = 132). Loline alkaloids correspond to the sum of N-acetylnorloline (NANL), N-formylloline (NFL) and N-acetylloline (NAL). Asterisks denote significant effects of symbioses (S), plant part (P) or their interaction (S × P) as shown in Table 2. For vegetative and reproductive plant parts, distinct letters on boxplots indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) based on post-hoc multiple comparisons of means. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. DW, dry weight.

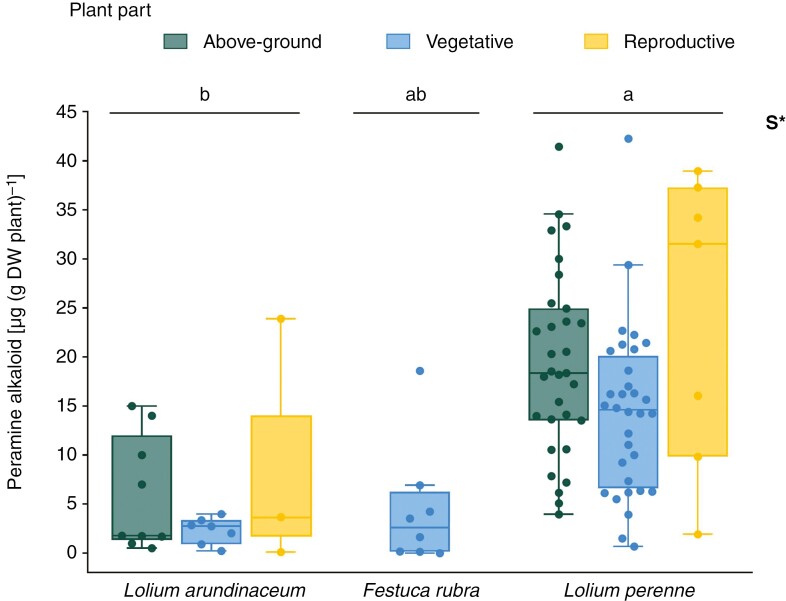

Fig. 2.

Concentration of Epichloë-derived peramine alkaloid in different plant–endophyte symbioses (indicated through host species name) and plant parts. The category ‘above-ground’ is used to aggregate all data from studies that did not define the tissue type, either vegetative or reproductive. Points around the boxplots are independent studies (N = 97). Asterisks denote significant effects of symbiosis (S) only, as shown in Table 2. Distinct letters on boxplots indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) among symbioses based on post-hoc multiple comparisons of means. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. DW, dry weight.

Fig. 3.

Concentration of Epichloë-derived ergovaline alkaloid in different plant–endophyte symbioses (indicated through host species name) and plant parts. The category ‘above-ground’ is used to aggregate all data from studies that did not define the tissue type, either vegetative or reproductive. Points around the boxplots are independent studies (N = 246). Asterisks denote significant effects of symbioses (S), plant part (P) or their interaction (S × P) as shown in Table 2. For vegetative and reproductive plant parts, distinct letters on boxplots indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) based on post-hoc multiple comparisons of means. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. DW, dry weight.

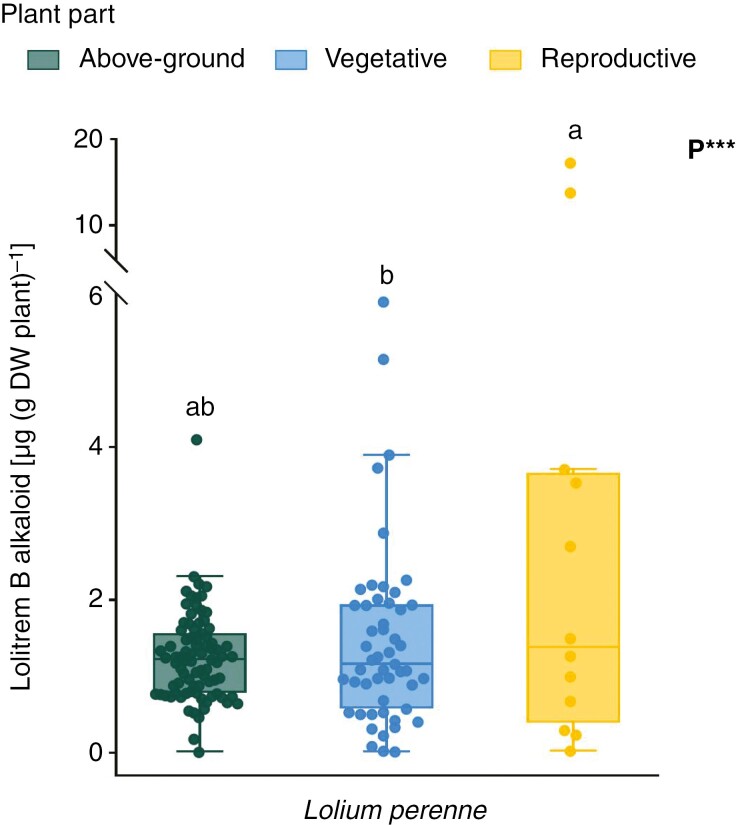

Fig. 4.

Concentration of Epichloë-derived lolitrem B alkaloid in the symbiosis between Lolium perenne and the common strain of the endophyte fungus Epichloë festucae var. lolii. The category ‘above-ground’ is used to aggregate all data from studies that did not define the tissue type, either vegetative or reproductive. Points around the boxplots are independent studies (N = 146). Asterisks denote significant effects of plant part (P) only, as shown in Table 2. Distinct letters on boxplots indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) among plant parts based on post-hoc multiple comparisons of means. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. DW, dry weight.

Data on loline alkaloid concentrations in above-ground vegetative and reproductive tissues were retrieved for L. arundinaceum, L. pratense and L. multiflorum|L. rigidum symbioses, whereas in above-ground unclassified tissues were only available for L. arundinaceum. Loline alkaloid concentration data in below-ground tissues were retrieved for L. arundinaceum and L. pratense but not for L. multiflorum|L. rigidum (Fig. 1). In reproductive tissues, loline alkaloid concentrations were 13.4- and 7.5-fold higher in L. pratense and L. arundinaceum than in L. multiflorum|L. rigidum (Fig. 1) (t(37.3) = 4.470, P < 0.001 and t(9.28) = 3.819, P = 0.025, respectively). Conversely, the concentration of lolines in vegetative tissues did not differ among these symbioses. (Fig. 1). In below-ground tissues, loline alkaloid concentrations showed no significant differences between symbioses (Fig. 1). Additionally, loline alkaloid concentrations in above-ground tissues were similar to those in other plant parts for L. arundinaceum, but were 4.4-fold lower than in reproductive tissue (t(26.0) = −3.853, P = 0.026).

Data on peramine concentration in above-ground vegetative, reproductive and unclassified tissues were retrieved for L. arundinaceum and L. perenne, whereas in above-ground vegetative tissues, data were also available for F. rubra (Fig. 2). Retrieved data on peramine concentration in below-ground tissues were insufficient for quantitative analysis. As the concentration of peramine varies among symbioses, rather than among plant parts or their interaction (see above), the post-hoc contrasts were explicitly directed at differences among symbioses. The concentration of peramine averaged 3.5-fold higher in L. perenne than in L. arundinaceum (t(85.8) = 3.47, P < 0.005) and peramine concentration in F. rubra showed intermediate levels (Fig. 2).

Data on ergovaline concentration in above-ground vegetative and reproductive tissues were retrieved for L. arundinaceum, F. rubra and L. perenne whereas data on unclassified above-ground tissues were only available for L. arundinaceum and L. perenne (Fig. 3). Retrieved data on ergovaline concentration in below-ground tissues were insufficient for quantitative comparisons. In reproductive tissues, the concentration of ergovaline was about 3.8- and 13.5-fold higher in L. perenne than in L. arundinaceum (t(229.6) = 3.539, P = 0.014) and F. rubra plants (t(217) = 4.524, P < 0.001) respectively (Fig. 3). Conversely, the ergovaline concentration in unclassified above-ground tissues was not different among L. arundinaceum and L. perenne (Fig. 3). In vegetative tissue, the concentration of ergovaline was about 5.7-fold higher in L. arundinaceum than in F. rubra plants (t(211.8) = 3.901, P = 0.004), whereas it showed an intermediate level in L. perenne (Fig. 3).

Data on lolitrem B concentration were retrieved only for the L. perenne – E. festucae symbiosis occurring in above-ground vegetative, reproductive and unclassified above-ground tissues (Fig. 4). Data on lolitrem B concentration in below-ground tissues were insufficient for quantitative analysis. The concentration of lolitrem B was 1.6-fold higher in reproductive than in vegetative tissues (t(142.6) = 3.918, P < 0.001). The concentration of this alkaloid in unclassified above-ground tissues was not different than in reproductive and vegetative tissues (Fig. 4).

DISCUSSION

Through the compilation and analysis of published data, we present a synthesis of the variation in the four major alkaloids derived from Epichloë fungal endophytes across different hosts and plant parts. The concentrations of most alkaloids varied among plant species and between plant parts. These variations may stem from differences in fungal species-specific growth and/or alkaloid biosynthesis rates within plants, the regulation of alkaloid production by the plant, and the ability of alkaloids to mobilize between plant tissues.

The concentrations of loline alkaloids in reproductive and vegetive tissues were higher in both L. pratense and L. arundinaceum than in L. multiflorum|L. rigidum. The difference in alkaloid concentrations may result from the variations in size between these plant species. Whereas L. pratense and L. arundinaceum are perennial plants, L. multiflorum and L. rigidum are annuals. Although initially the sizes can be comparable, perennial grasses tend to accumulate more biomass than annual grasses. As the plant size increases at the crown level (i.e. the plant base that connects roots and shoots, containing apical and axillary meristematic buds that will give rise to tillers and inflorescences, respectively), it is possible that the mycelium of the endophytic fungus also increases. All this together may explain the observed positive association between the concentration of Epichloë-derived alkaloids and plant size (Ball et al., 1997a). In the leaves, endophyte hyphae are generally more abundant in sheaths than in blades but in L. multiflorum|L. rigidum, hyphae are mostly located at the base of leaf sheaths (Moon et al., 2000; Christensen et al., 2002). Considering that most of the vegetative tiller (rolled leaf sheaths and their corresponding blades) is free of endophytic mycelia in L. multiflorum|L. rigidum, it is reasonable to expect lower alkaloid contents per unit of plant biomass in this plant species compared to L. pratense and certain L. arundinaceum, in which Epichloë hyphae are usually distributed throughout the whole leaf (Justus et al., 1997; Christensen et al., 2002). Although the localized distribution of the endophyte mycelia in annual hosts could eventually compromise the resistance to herbivores, there is evidence demonstrating a superior resistance in plants with endophytic symbiosis in comparison to their non-symbiotic counterparts (e.g. Ueno et al., 2016; Bastias et al., 2017b). Dissimilarities in the alkaloid synthesis rate between Epichloë species might have also contributed to the variations in loline alkaloid concentration among plant species. While no studies have compared loline alkaloid biosynthesis rates between the fungal species associated with L. pratense, L. arundinaceum or L. multiflorum|L. rigidum, it has been documented that differences exist in the production of lolines among plant–endophyte associations (Freitas et al., 2020). Further studies are needed to investigate whether there are differences in the rates of loline alkaloid biosynthesis associated with distinct host plant species.

Peramine concentrations were higher in L. perenne than in L. arundinaceum independently of the plant part. According to this, the relative contribution of peramine to the level of plant resistance to insects might be higher in L. perenne than in L. arundinaceum. Peramine stands as the only characterized alkaloid that exclusively provides protection against insects within the L. perenne–common endophyte associations. However, in the context of the L. arundinaceum–wild type endophyte association, this protective activity can be supplemented by loline alkaloids, which also exhibit exclusive bioactivity against insects (Wilkinson et al., 2000; Schardl et al., 2007). Due to the relevance of peramine for herbivorous insect resistance in L. perenne, it is likely that insect herbivory has selected associations within this plant species with traits that result in elevated alkaloid concentrations. In agreement with this, it was shown that the same Epichloë strain produced higher levels of peramine per unit of plant biomass in L. perenne than in L. arundinaceum (Freitas et al., 2020). As in the case of lolines, the amount of Epichloë mycelial biomass could also have contributed to the plant species differences in peramine concentrations, since certain plant genotypes of L. arundinaceum have been described with absence of Epichloë hyphae within leaf blades (the in planta correlation between peramine concentration and Epichloë mycelial biomass is generally positive) (Hinton and Bacon, 1985; Christensen et al., 1998; Popay et al., 2003a; Takach et al., 2012). Peramine was the only alkaloid whose concentration did not vary between plant parts. This finding agrees with previous evidence showing the systemic distribution of peramine in plants (Schardl et al., 2004). The explanation has been associated with the hydrophilic nature of peramine, which allows the alkaloid to be transported via leaf fluids to plant sections that are not colonized by fungal hyphae (Keogh et al., 1996; Ball et al., 1997a; Koulman et al., 2007; Hewitt et al., 2020). As with loline alkaloids, the widespread presence of peramine in different plant parts probably explains the effectiveness of this alkaloid in controlling different insect herbivores (Bastias et al., 2017a).

Ergovaline and lolitrem B are known to be responsible for causing severe disorders in mammals (Bouton et al., 2002; Gundel et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2013). There is also evidence for these two alkaloids to be involved in plant resistance to herbivorous insects (Rowan, 1993; Ball et al., 1997b; Potter et al., 2008; Graff et al., 2020). Our results showed that both alkaloids were more concentrated in reproductive than vegetative parts in some plant hosts. As they both are hydrophobic compounds, they are primarily associated with plant parts where the fungal mycelium is present (Ball et al., 1997a; Spiering et al., 2005). In accordance with previous studies (Ball et al., 1995; Keogh et al., 1996; Repussard et al., 2014), their concentrations increase with the plant passage from vegetative to reproductive stages. Given their relatively low mobility, the accumulation of these alkaloids may result from both a high mycelial biomass and/or a high rate of alkaloid synthesis within reproductive tissues. In alignment with the biomass-associated prediction, there exists a general trend of elevated endophyte mycelial biomass as plants transition into the reproductive ontogenetic phase (e.g. di Menna and Waller, 1986; Puentes et al., 2007; Rogers et al., 2011; Fuchs et al., 2017c). Regarding the biosynthesis-associated prediction, the high lolitrem B concentration in reproductive tissues is supported from genetic results showing that the endophyte gene ltmM encoding an enzyme in the alkaloid synthesis pathway was highly expressed in floral organs of L. perenne (May et al., 2008). An approach that holds potential for elucidating the underlying mechanisms behind the observed elevated alkaloid concentrations in reproductive plant parts would be comparing the relationship between alkaloid concentration and endophyte mycelium in seeds for both relatively immobile alkaloids (e.g. ergovaline) and relatively mobile alkaloids (e.g. peramine). If alkaloid mobility plays a significant role in plant part accumulation, it follows that the alkaloid-to-mycelium ratio would be greater for more mobile alkaloids compared to less mobile ones – at least in those plant parts where endophyte hyphae are virtually absent (e.g. in roots). This is because the former compounds are not solely generated in situ (within the seed) but are also transported from the plant’s green tissues, as discussed by Ueno et al. (2020).

The occurrence of alkaloids in below-ground tissues has not been as well documented as in above-ground tissues. Only data on loline alkaloid concentration in below-ground tissues were sufficient to perform comparative and quantitative analyses. However, it is worth mentioning that individual studies have reported the occurrence of ergovaline, lolitrem B and peramine in roots (Azevedo and Welty, 1995; Ball et al., 1997a; Justus et al., 1997; Vassiliadis et al., 2023). In agreement with our results, alkaloids in below-ground tissues normally reach lower concentrations than in above-ground tissues, but the magnitude of reduction depends on the alkaloid type and association (Vassiliadis et al., 2023). Since endophyte mycelia are practically absent in roots (Hinton and Bacon, 1985; Azevedo and Welty, 1995), the alkaloid presence in these tissues relies mainly on the translocation from above-ground tissues and not on in situ production. Despite the reduced concentrations of Epichloë-derived alkaloids in below-ground tissues, the levels may be high enough to be effective in controlling root insect herbivores (Caradus and Johnson, 2020; but see Bastías et al., 2021). For instance, the presence of common endophytes in L. perenne and F. pratensis plants reduced the population sizes of the root aphid Aploneura lentisci and the larval growth of the root-feeding scarab Costelytra giveni (Popay et al., 2003b; Popay and Cox, 2016). It would be interesting to investigate how herbivory, whether exerted on roots or on leaves, can alter the translocation patterns of alkaloids between below-ground and above-ground structures. Subsequently, such alterations may influence the levels of endophyte-conferred resistance in host plants.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Our work provides a general picture of variation patterns in the concentration of the main fungal alkaloids among different hosts and plant parts. These patterns can be understood by taking into account factors such as the growth dynamics of endophytic fungi within the host plant, the particular mobility characteristics of the alkaloid compounds and the regulatory mechanisms employed by the plants in relation to endophytes. However, there are several open questions to be addressed.

First, our study focused on plant parts that are not necessarily associated with specific plant phenological stages. Recent transcriptomic analyses have revealed variations in the plant’s regulation of endophyte growth and functions based on gene expression profiles across different plant organs and stages (Dinkins et al., 2017; Schmid et al., 2017; Nagabhyru et al., 2019). Therefore, as the regulation of hyphae proliferation and endophyte metabolic activity can vary between vegetative tillers depending on the plant stage (e.g. if the plant is at tillering or at anthesis), a similar variation can be expected in alkaloid concentration (e.g. Ball et al., 1997a). Moreover, these variations are likely to be associated with the environmental conditions that plants experience during winter and spring–summer seasons, strongly determining the described seasonal changes in endophyte mycelia contraction and alkaloid production (di Menna & Waller, 1986; Puentes et al., 2007; Fuchs et al., 2017c).

Second, accumulating evidence shows that alkaloid concentration can be influenced by environmental conditions of plant growth such as level of resources, soil water availability, salinity, temperature and herbivory (Bultman et al., 2004; Rasmussen et al., 2007; Repussard et al., 2014; Hennessy et al., 2016; Graff et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2022). Besides examining how general and consistent are those effects, it is essential to investigate the underlying mechanisms of the induction of alkaloids by the action of herbivores that differ in feeding habits (e.g. defoliation by mammals, chewing insects and sap-sucking insects) (Bultman et al., 2004; Sullivan et al., 2007; Fuchs et al., 2017b; Bubica Bustos et al., 2022).

Finally, the degree of protection against herbivores conferred by Epichloë may not only vary based on the growth patterns of the endophyte that influence alkaloid distributions within the plant but also due to the specific array of alkaloids present in the plant. Endophytes producing more than one alkaloid are expected to broaden the spectrum of herbivores under control conditions compared to those producing a single alkaloid (Bastias et al., 2017a). Under this premise, endophytes producing more than one alkaloid should be more prevalent in natural populations, provided their presence does not entail greater production costs for the host plants (Semmartin et al., 2015). However, these individual-based characteristics become not only more complex but also more eco-evolutionarily relevant when scaled up to include diversity at the population level (Vikuk et al., 2019). To enhance our understanding of the role of Epichloë-derived alkaloids in plant resistance to herbivores, it is crucial to further explore the diversity of endophytes associated with each plant species and the chemical diversity of these fungal endophytes, and to extend this type of study to other plant species.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Annals of Botany online and consist of the following.

Table S1: Reference list from articles reported in Table 1.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was part of the postdoctoral research by F.M.R. supported by the Agencia Nacional de Investigaciones Argentina (ANPCyT) PICT-2018-01593 (Principal Investigator: P.E.G.). P.E.G. also acknowledges support by the Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico of Chile (FONDECYT-2021-1210908). D.A.B. acknowledges the research support provided by the Strategic Science Investment Fund (SSIF) from the New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. Finally, we would like to express our gratitude for the insightful comments provided by the two reviewers, which significantly improved the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Florencia M Realini, IFEVA, Facultad de Agronomía, Universidad de Buenos Aires, CONICET, Buenos Aires, Argentina; Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Departamento de Ecología, Genética y Evolución, Laboratorio de Citogenética y Evolución (LaCyE), Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina; Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Instituto de Ecología, Genética y Evolución (IEGEBA), Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Víctor M Escobedo, Instituto de Investigación Interdisciplinaria (I3), Universidad de Talca, Campus Talca, Chile; Centro de Ecología Integrativa, Instituto de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad de Talca, Talca, Chile.

Andrea C Ueno, IFEVA, Facultad de Agronomía, Universidad de Buenos Aires, CONICET, Buenos Aires, Argentina; Instituto de Investigación Interdisciplinaria (I3), Universidad de Talca, Campus Talca, Chile; Centro de Ecología Integrativa, Instituto de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad de Talca, Talca, Chile.

Daniel A Bastías, AgResearch Limited, Grasslands Research Centre, Palmerston North 4442, New Zealand.

Christopher L Schardl, Department of Plant Pathology, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40546, USA.

Fernando Biganzoli, Departamento de Métodos Cuantitativos y Sistemas de Información, Facultad de Agronomía, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Pedro E Gundel, IFEVA, Facultad de Agronomía, Universidad de Buenos Aires, CONICET, Buenos Aires, Argentina; Centro de Ecología Integrativa, Instituto de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad de Talca, Talca, Chile.

FUNDING

This work was supported by Agencia Nacional de Investigaciones of Argentina [PICT-2018-01593] and the Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico of Chile [FONDECYT-2021-1210908].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

LITERATURE CITED

- Agrawal AA, Hastings AP, Johnson MTJ, Maron JL, Salminen J-P.. 2012. Insect herbivores drive real-time ecological and evolutionary change in plant populations. Science 338: 113–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose KV, Koppenhöfer AM, Belanger FC.. 2014. Horizontal gene transfer of a bacterial insect toxin gene into the Epichloë fungal symbionts of grasses. Scientific Reports 4: 5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo MD, Welty RE.. 1995. A study of the fungal endophyte Acremonium coenophialum in the roots of tall fescue seedlings. Mycologia 87: 289–297. [Google Scholar]

- Bacetty AA, Snook ME, Glenn AE, et al. 2009. Toxicity of endophyte-infected tall fescue alkaloids and grass metabolites on Pratylenchus scribneri. Phytopathology 99: 1336–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball OJ, Prestidge RA, Sprosen JM.. 1995. Interrelationships between Acremonium lolii, peramine, and lolitrem b in perennial ryegrass. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 61: 1527–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball OJP, Barker GM, Prestidge RA, Lauren DR.. 1997a. Distribution and accumulation of the alkaloid peramine in Neotyphodium lolii-infected perennial ryegrass. Journal of Chemical Ecology 23: 1419–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Ball OJP, Miles CO, Prestidge RA.. 1997b. Ergopeptine alkaloids and Neotyphodium lolii-mediated resistance in perennial ryegrass against adult Heteronychus arator (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Journal of Economic Entomology 90: 1382–1391. [Google Scholar]

- Bastías DA, Gundel PE.. 2023. Plant stress responses compromise mutualisms with Epichloë endophytes. Journal of Experimental Botany 74: 19–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastias DA, Martínez-Ghersa MA, Ballaré CL, Gundel PE.. 2017a. Epichloë fungal endophytes and plant defenses: Not just alkaloids. Trends in Plant Science 22: 939–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastias DA, Ueno AC, Machado Assefh CR, Alvarez AE, Young CA, Gundel PE.. 2017b. Metabolism or behavior: explaining the performance of aphids on alkaloid-producing fungal endophytes in annual ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum). Oecologia 185: 245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastías DA, Gianoli E, Gundel PE.. 2021. Fungal endophytes can eliminate the plant growth–defence trade-off. New Phytologist 230: 2105–2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastías DA, Ueno AC, Gundel PE.. 2023. Global change factors influence plant–Epichloë associations. Journal of Fungi 9: 446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D, Mace W, Grage K, et al. 2019. Efficient nonenzymatic cyclization and domain shuffling drive pyrrolopyrazine diversity from truncated variants of a fungal NRPS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116: 25614–25623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton JH, Latch GCM, Hill NS, et al. 2002. Reinfection of tall fescue cultivars with non-ergot alkaloid–producing endophytes. Agronomy Journal 94: 567–574. [Google Scholar]

- Bubica Bustos LM, Ueno AC, Biganzoli F, et al. 2022. Can aphid herbivory induce intergenerational effects of endophyte-conferred resistance in grasses? Journal of Chemical Ecology 48: 867–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley H, Young CA, Charlton ND, et al. 2019. Leaf endophytes mediate fertilizer effects on plant yield and traits in northern oat grass (Trisetum spicatum). Plant and Soil 434: 425–440. [Google Scholar]

- Bultman TL, Bell G, Martin WD.. 2004. A fungal endophyte mediates reversal of wound-induced resistance and constrains tolerance in a grass. Ecology 85: 679–685. [Google Scholar]

- Bylin AG, Hume DE, Card SD, Mace WJ, Lloyd-West CM, Huss-Danell K.. 2014. Influence of nitrogen fertilization on growth and loline alkaloid production of meadow fescue (Festuca pratensis) associated with the fungal symbiont Neotyphodium uncinatum. Botany 92: 370–376. [Google Scholar]

- Caradus JR, Johnson LJ.. 2020. Epichloë fungal endophytes—from a biological curiosity in wild grasses to an essential component of resilient high performing ryegrass and fescue pastures. Journal of Fungi (Basel, Switzerland) 6: 322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caradus JR, Card SD, Finch SC, et al. 2022. Ergot alkaloids in New Zealand pastures and their impact. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research 65: 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Card SD, Bastías DA, Caradus JR.. 2021. Antagonism to plant pathogens by Epichloë fungal endophytes—a review. Plants 10: 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Simpson WR, Nan Z, Li C.. 2022. NaCl stress modifies the concentrations of endophytic fungal hyphal and peramine in Hordeum brevisubulatum seedlings. Crop and Pasture Science 73: 214–221. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen MJ, Easton HS, Simpson WR, Tapper BA.. 1998. Occurrence of the fungal endophyte Neotyphodium coenophialum in leaf blades of tall fescue and implications for stock health. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research 41: 595–602. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen MJ, Bennett RJ, Schmid J.. 2002. Growth of Epichloë/Neotyphodium and p-endophytes in leaves of Lolium and Festuca grasses. Mycological Research 106: 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen MJ, Bennett RJ, Ansari HA, et al. 2008. Epichloë endophytes grow by intercalary hyphal extension in elongating grass leaves. Fungal Genetics and Biology 45: 84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cibils-Stewart X, Mace WJ, Popay AJ, et al. 2022. Interactions between silicon and alkaloid defences in endophyte-infected grasses and the consequences for a folivore. Functional Ecology 36: 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Clay K. 1988. Fungal endophytes of grasses: A defensive mutualism between plants and fungi. Ecology 69: 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Decunta FA, Pérez LI, Malinowski DP, Molina-Montenegro MA, Gundel PE.. 2021. A systematic review on the effects of Epichloë fungal endophytes on drought tolerance in cool-season grasses. Frontiers in Plant Science 12: 644731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Menna ME, Waller JE.. 1986. Visual assessment of seasonal changes in amount of mycelium of Acremonium loliae in leaf sheaths of perennial ryegrass. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research 29: 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Dinkins RD, Nagabhyru P, Graham MA, Boykin D, Schardl CL.. 2017. Transcriptome response of Lolium arundinaceum to its fungal endophyte Epichloë coenophiala. New Phytologist 213: 324–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellers J, Toby Kiers E, Currie CR, McDonald BR, Visser B.. 2012. Ecological interactions drive evolutionary loss of traits. Ecology Letters 15: 1071–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch SC, Prinsep MR, Popay AJ, et al. 2020. Identification and structure elucidation of epoxyjanthitrems from Lolium perenne infected with the endophytic fungus Epichloë festucae var. Lolii and determination of the tremorgenic and anti-insect activity of epoxyjanthitrem I. Toxins 12: 526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas PP, Hampton JG, Rolston MP, Glare TR, Miller PP, Card SD.. 2020. A tale of two grass species: Temperature affects the symbiosis of a mutualistic Epichloë endophyte in both tall fescue and perennial ryegrass. Frontiers in Plant Science 11: 00530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs B, Breuer T, Findling S, et al. 2017a. Enhanced aphid abundance in spring desynchronizes predator–prey and plant–microorganism interactions. Oecologia 183: 469–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs B, Krischke M, Mueller MJ, Krauss J.. 2017b. Herbivore-specific induction of defence metabolites in a grass–endophyte association. Functional Ecology 31: 318–324. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs B, Krischke M, Mueller MJ, Krauss J.. 2017c. Plant age and seasonal timing determine endophyte growth and alkaloid biosynthesis. Fungal Ecology 29: 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher RT, White EP, Mortimer PH.. 1981. Ryegrass staggers: isolation of potent neurotoxins lolitrem A and lolitrem B from staggers-producing pastures. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 29: 189–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff P, Gundel PE, Salvat A, Cristos D, Chaneton EJ.. 2020. Protection offered by leaf fungal endophytes to an invasive species against native herbivores depends on soil nutrients. Journal of Ecology 108: 1592–1604. [Google Scholar]

- Guerre P. 2015. Ergot alkaloids produced by endophytic fungi of the genus Epichloë. Toxins 7: 773–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundel PE, Rudgers JA, Ghersa CM.. 2011. Incorporating the process of vertical transmission into understanding of host–symbiont dynamics. Oikos 120: 1121–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Gundel PE, Pérez LI, Helander M, Saikkonen K.. 2013. Symbiotically modified organisms: nontoxic fungal endophytes in grasses. Trends in Plant Science 18: 420–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy LM, Popay AJ, Finch SC, Clearwater MJ, Cave VM.. 2016. Temperature and plant genotype alter alkaloid concentrations in ryegrass infected with an Epichloë endophyte and this affects an insect herbivore. Frontiers in Plant Science 7: 1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt KG, Mace WJ, McKenzie CM, Matthew C, Popay AJ.. 2020. Fungal alkaloid occurrence in endophyte-infected perennial ryegrass during seedling establishment. Journal of Chemical Ecology 46: 410–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DM, Bacon CW.. 1985. The distribution and ultrastructure of the endophyte of toxic tall fescue. Canadian Journal of Botany 63: 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen JG, Popay AJ, Tapper BA.. 2009. Argentine stem weevil adults are affected by meadow fescue endophyte and its loline alkaloids. New Zealand Plant Protection 62: 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LJ, de Bonth ACM, Briggs LR, et al. 2013. The exploitation of epichloae endophytes for agricultural benefit. Fungal Diversity 60: 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- Justus M, Witte L, Hartmann T.. 1997. Levels and tissue distribution of loline alkaloids in endophyte-infected Festuca pratensis. Phytochemistry 44: 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Keogh RG, Tapper BA, Fletcher RH.. 1996. Distributions of the fungal endophyte Acremonium lolii, and of the alkaloids lolitrem B and peramine, within perennial ryegrass. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research 39: 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Koricheva J, Gurevitch J, Mengersen K.. 2013. Handbook of metaanalysis in ecology and evolution. Woodstock: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koulman A, Lane GA, Christensen MJ, Fraser K, Tapper BA.. 2007. Peramine and other fungal alkaloids are exuded in the guttation fluid of endophyte-infected grasses. Phytochemistry 68: 355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB.. 2017. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software 82: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Leuchtmann A, Bacon CW, Schardl CL, White Jr JF, Tadych M.. 2014. Nomenclatural realignment of Neotyphodium species with genus Epichloë. Mycologia 106: 202–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Nagabhyru P, Schardl CL.. 2017. Epichloë festucae endophytic growth in florets, seeds, and seedlings of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne). Mycologia 109: 691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüdecke D, Ben-Shachar MS, Patil I, Waggoner P, Makowski D.. 2021. performance: An R package for assessment, comparison and testing of statistical models. Journal of Open Source Software 6: 3139. [Google Scholar]

- May K, Bryant MK, Zhang X, Ambrose B, Scott B.. 2008. Patterns of expression of a lolitrem biosynthetic gene in the Epichloë festucae–perennial ryegrass symbiosis. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions 21: 188–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mc Cargo PD, Iannone LJ, Vignale MV, Schardl CL, Rossi MS.. 2014. Species diversity of Epichloë symbiotic with two grasses from southern Argentinean Patagonia. Mycologia 106: 339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon CD, Scott B, Schardl CL, Christensen MJ.. 2000. The evolutionary origins of Epichloë endophytes from annual ryegrasses. Mycologia 92: 1103–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Moore JR, Pratley JE, Mace WJ, Weston LA.. 2015. Variation in alkaloid production from genetically diverse Lolium accessions infected with Epichloë species. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 63: 10355–10365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagabhyru P, Dinkins RD, Wood CL, Bacon CW, Schardl CL.. 2013. Tall fescue endophyte effects on tolerance to water-deficit stress. BMC Plant Biology 13: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagabhyru P, Dinkins RD, Schardl CL.. 2019. Transcriptomics of Epichloë-grass symbioses in host vegetative and reproductive stages. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions 32: 194–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaccione DG, Beaulieu WT, Cook D.. 2014. Bioactive alkaloids in vertically transmitted fungal endophytes. Functional Ecology 28: 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Pennell CGL, Rolston MP, De Bonth A, Simpson WR, Hume DE.. 2010. Development of a bird-deterrent fungal endophyte in turf tall fescue. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research 53: 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Popay AJ, Cox NR.. 2016. Aploneura lentisci (homoptera: Aphididae) and its interactions with fungal endophytes in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne). Frontiers in Plant Science 7: 1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay AJ, Hume DE, Davis KL, Tapper BA.. 2003a. Interactions between endophyte (Neotyphodium spp.) and ploidy in hybrid and perennial ryegrass cultivars and their effects on Argentine stem weevil (Listronotus bonariensis). New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research 46: 311–319. [Google Scholar]

- Popay AJ, Townsend RJ, Fletcher LR.. 2003b. The effect of endophyte Neotyphodium uncinatum in meadow fescue on grass grub larvae. New Zealand Plant Protection 56: 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Potter DA, Tyler Stokes J, Redmond CT, Schardl CL, Panaccione DG.. 2008. Contribution of ergot alkaloids to suppression of a grass-feeding caterpillar assessed with gene knockout endophytes in perennial ryegrass. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 126: 138–147. [Google Scholar]

- POWO. 2023. Plants of the World online. In: Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, ed. Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens. [Google Scholar]

- Puentes A, Bazely D, Huss-Danell K.. 2007. Endophytic fungi in Festuca pratensis grown in Swedish agricultural grasslands with different managements. Symbiosis 44: 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Quintessa Ltd. 2022. Graph Grabber. 2.0.2 edn. Henley-on-Thames: Quintessa Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. 2022. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 4.2.1 edn. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen S, Parsons AJ, Bassett S, et al. 2007. High nitrogen supply and carbohydrate content reduce fungal endophyte and alkaloid concentration in Lolium perenne. The New Phytologist 173: 787–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repussard C, Zbib N, Tardieu D, Guerre P.. 2014. Ergovaline and lolitrem B concentrations in perennial ryegrass in field culture in southern France: Distribution in the plant and impact of climatic factors. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 62: 12707–12712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedell WE, Kieckhefer RE, Petroski RJ, Powell RG.. 1991. Naturally-occurring and synthetic loline alkaloid derivatives insect feeding behavior modification and toxicity. Journal of Entomological Science 26: 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers WM, Roberts CA, Andrae JG, et al. 2011. Seasonal fluctuation of ergovaline and total ergot alkaloid concentrations in tall fescue regrowth. Crop Science 51: 1291–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Rowan DD. 1993. Lolitrems, peramine and paxilline: Mycotoxins of the ryegrass/endophyte interaction. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 44: 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Saikkonen K, Saari S, Helander M.. 2010. Defensive mutualism between plants and endophytic fungi? Fungal Diversity 41: 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Schardl CL. 2010. The epichloae, symbionts of the grass subfamily Poöideae. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 97: 646–665. [Google Scholar]

- Schardl CL, Leuchtmann A, Spiering MJ.. 2004. Symbioses of grasses with seedborne fungal endophytes. Annual Review of Plant Biology 55: 315–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schardl CL, Grossman RB, Nagabhyru P, Faulkner JR, Mallik UP.. 2007. Loline alkaloids: Currencies of mutualism. Phytochemistry 68: 980–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schardl CL, Craven KD, Speakman S, Stromberg A, Lindstrom A, Yoshida R.. 2008. A novel test for host–symbiont codivergence indicates ancient origin of fungal endophytes in grasses. Systematic Biology 57: 483–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schardl CL, Young CA, Faulkner JR, Florea S, Pan J.. 2012. Chemotypic diversity of epichloae, fungal symbionts of grasses. Fungal Ecology 5: 331–344. [Google Scholar]

- Schardl CL, Florea S, Pan J, Nagabhyru P, Bec S, Calie PJ.. 2013a. The epichloae: Alkaloid diversity and roles in symbiosis with grasses. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 16: 480–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schardl CL, Young CA, Pan J, et al. 2013b. Currencies of mutualisms: sources of alkaloid genes in vertically transmitted epichloae. Toxins 5: 1064–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schardl CL, Afkhami ME, Gundel PE, et al. 2023. Diversity of seed endophytes: Causes and implications. In: Scott B, Mesarich C. eds. Plant relationships. The Mycota. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid J, Day R, Zhang N, et al. 2017. Host tissue environment directs activities of an Epichloë endophyte, while it induces systemic hormone and defense responses in its native perennial ryegrass host. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions 30: 138–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semmartin M, Omacini M, Gundel PE, Hernández-Agramonte IM.. 2015. Broad-scale variation of fungal-endophyte incidence in temperate grasses. Journal of Ecology 103: 184–190. [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Barajas MC, Vázquez-de-Aldana BR, Álvarez A, Zabalgogeazcoa I.. 2019. Sympatric Epichloë species and chemotypic profiles in natural populations of Lolium perenne. Fungal Ecology 39: 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Spiering MJ, Lane GA, Christensen MJ, Schmid J.. 2005. Distribution of the fungal endophyte Neotyphodium lolii is not a major determinant of the distribution of fungal alkaloids in Lolium perenne plants. Phytochemistry 66: 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TJ, Rodstrom J, Vandop J, et al. 2007. Symbiont-mediated changes in Lolium arundinaceum inducible defenses: Evidence from changes in gene expression and leaf composition. The New Phytologist 176: 673–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadych M, Bergen MS, White JF.. 2014. Epichloë spp. associated with grasses: new insights on life cycles, dissemination and evolution. Mycologia 106: 181–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takach JE, Mittal S, Swoboda GA, et al. 2012. Genotypic and chemotypic diversity of Neotyphodium endophytes in tall fescue from Greece. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 78: 5501–5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno AC, Gundel PE, Omacini M, Ghersa CM, Bush LP, Martínez-Ghersa MA.. 2016. Mutualism effectiveness of a fungal endophyte in an annual grass is impaired by ozone. Functional Ecology 30: 226–234. [Google Scholar]

- Ueno AC, Gundel PE, Ghersa CM, et al. 2020. Ontogenetic and trans-generational dynamics of a vertically transmitted fungal symbiont in an annual host plant in ozone-polluted settings. Plant, Cell & Environment 43: 2540–2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno AC, Gundel PE, Molina-Montenegro MA, Ramos P, Ghersa CM, Martínez-Ghersa MA.. 2021. Getting ready for the ozone battle: Vertically transmitted fungal endophytes have transgenerational positive effects in plants. Plant, Cell & Environment 44: 2716–2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassiliadis S, Reddy P, Hemsworth J, Spangenberg GC, Guthridge KM, Rochfort SJ.. 2023. Quantitation and distribution of Epichloë-derived alkaloids in perennial ryegrass tissues. Metabolites 13: 205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikuk V, Young CA, Lee ST, et al. 2019. Infection rates and alkaloid patterns of different grass species with systemic Epichloë endophytes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 85: e00465-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson HH, Siegel MR, Blankenship JD, Mallory AC, Bush LP, Schardl CL.. 2000. Contribution of fungal loline alkaloids to protection from aphids in a grass-endophyte mutualism. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions 13: 1027–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young CA, Bryant MK, Christensen MJ, Tapper BA, Bryan GT, Scott B.. 2005. Molecular cloning and genetic analysis of a symbiosis-expressed gene cluster for lolitrem biosynthesis from a mutualistic endophyte of perennial ryegrass. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 274: 13–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young CA, Tapper BA, May K, Moon CD, Schardl CL, Scott B.. 2009. Indole-diterpene biosynthetic capability of Epichloë endophytes as predicted by ltm gene analysis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 75: 2200–2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Card SD, Mace WJ, Christensen MJ, McGill CR, Matthew C.. 2017. Defining the pathways of symbiotic Epichloë colonization in grass embryos with confocal microscopy. Mycologia 109: 153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.