Abstract

Cloning and sequencing of segment 9 of Bombyx mori cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus (BmCPV) strains H and I were performed. The segment consisted of 1,186 bp harboring 5′ and 3′ noncoding regions and an open reading frame from positions 75 to 1037, encoding a protein with 320 amino acids, termed NS5. Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of NS5 for the two strains indicated 37 point differences resulting in only six amino acid replacements. Homology search showed that NS5 has localized similarities to human poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and human rotavirus NS26. By Western blot analysis, NS5 was found in BmCPV-infected midgut cells, but not in polyhedra or virus virions, and was mainly detectable in the nucleus in BmCPV-infected BmN4 cells. Immunoblot analysis with anti-NS5 and antipolyhedrin antibodies displayed marked differences in the period of expression of NS5 and polyhedrin: the polyhedrin molecule was first detected 2 or 3 days after infection with BmCPV, whereas the expression of NS5 was initiated within a few hours. In addition, the level of polyhedrin increased as the infection developed, whereas the amount of NS5 remained essentially constant. When segment 9 was expressed with a baculovirus expression system, the resulting NS5 protein possessed the ability to bind to the double-stranded RNA genome. These results suggest that NS5 is expressed in early stages of infection and contributes to regulation of genomic RNA function.

BmCPV, a member of the Reoviridae family, is known to produce water-insoluble inclusion bodies with strain-dependent shapes in the cytoplasm of midgut cells of the silkworm. BmCPVs are classified into nine strains (I, H, P, A, B, B1, B2, C1, and C2) on the basis of the shape and intracellular localization of the inclusion bodies as determined by light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (8). One typical example is a regular hexahedron (H strain), and another is a regular icosahedron (I strain). Each virus harbors dsRNA in a genome comprising 10 segments. It has been reported that segments 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 encode viral core proteins, while segments 5, 7, and 9 are responsible for production of nonstructural proteins and the smallest segment, 10, termed the polyhedrin gene, encodes a major constituent of the polyhedra (18). So far, nucleotide and amino acid sequences for only segment 10 have been reported (1, 19, 21, 23), and no systematic analysis of the BmCPV genome has been carried out. The proteins encoded by segments other than segment 10 have not been analyzed, and the mechanisms of regulation of gene expression remain to be elucidated.

To address these problems, in the present study we determined the complete nucleotide sequences of segment 9 of BmCPV strains H and I and showed that both consist of 1,186 bp encoding a protein (NS5) with 320 amino acids. We also showed by immunoblot analysis that segment 9 is expressed immediately after virus infection in BmN4 cells, suggesting that it contributes to the regulation of gene expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Abbreviations.

The abbreviations used in this report are as follows: BmCPV, Bombyx mori cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus; dsRNA, double-stranded RNA; PBS, 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 0.15 M NaCl; DTT, dithiothreitol; BmNPV, B. mori nuclear polyhedrosis virus; SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; and TE, 10 mM Tris-HCl containing 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0).

Purification of polyhedra.

The H and I strains of BmCPV were propagated by infecting fifth-instar and 2-day-old larvae, respectively. Twenty-gram samples of midgut from silkworm infected with either strain H or I were suspended in 100 ml of PBS and homogenized with a whirling blender on ice. The homogenates were centrifuged at 3,500 × g for 10 min, and then the pellets containing polyhedra were further purified by Percoll density gradient centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 20 min. A nine-to-one ratio of Percoll to PBS was employed for this purpose. The purified polyhedra were washed several times with PBS and finally suspended in 10 ml of TE. The shapes of the purified polyhedra were determined under a light microscope and in some cases under a scanning electron microscope for detailed examination. The purity of each polyhedron preparation from BmCPV strains H and I was more than 95%.

Purification of virions.

A 10-ml solution of 0.2 M NaHCO3-Na2CO3 (pH 10.8) was added to 5 × 1010 polyhedra, and each mixture was vortexed at 4°C for 10 min. After 60 min, the mixtures were centrifuged at 1,580 × g for 10 min, the resulting supernatants were centrifuged at 111,000 × g for 60 min, and the pellets in TE were again centrifuged at 86,000 × g for 90 min in a 10 to 40% (wt/vol) sucrose density gradient. Then, virions were recovered with syringes, washed with PBS, and collected by centrifugation at 111,000 × g for 60 min.

Isolation of dsRNA.

First, 2 × 109 polyhedra in 5 ml of TE were treated with 500 μl of 10% SDS–500 μl of 20-mg/ml proteinase K, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 16 h. Then, various dsRNA segments in the sample were extracted with phenol-chloroform, precipitated with ethanol, and separated by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. Each dsRNA segment was obtained by excision from the gel, and segment 9 was finally recovered with a UFC30GV column (Millipore).

Synthesis of single-stranded cDNA.

For the synthesis of cDNA, the primers 9F (5′-GGAGTAAATCCCAGGCGTAAACCGA-3′; forward primer) and 9R (5′-CCGGCTAACGACCCGAGTGCCC-3′; reverse primer) were constructed on the basis of the terminal RNA sequence of BmCPV segment 9 (13). Purified dsRNA segment 9 (200 ng in 5.3 μl of diethylpyrocarbonate water) was denatured at 100°C for 5 min, quickly chilled on ice, and treated in a typical reaction mixture containing 300 ng of forward and reverse primers, 20 U of RNase inhibitor, 40 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase, 10 mM DTT, and 1.8 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates in 20 μl of first-strand buffer (Gibco). After incubation at 37°C for 60 min, the reaction mixture was again heated to 100°C for 10 min to inactivate the reverse transcriptase activity.

PCR.

PCR was performed by addition of 300 ng of forward and reverse primers, 2 U of Taq DNA polymerase, and 0.8 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates to a 20-μl solution of single-stranded cDNA obtained as described above in PCR buffer (Wako). Thirty cycles of PCR were carried out with periods of 30 s at 94°C, 1 min at 56°C, and 5 min at 72°C. After the amplified cDNA was blunt ended with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I, it was cloned into the SmaI site of pBluescript KS(−). Recombinant pBluescript/BmCPV-S9 was then transfected into Escherichia coli X-L1 blue.

Determination of nucleotide sequence.

The nucleotide sequence of cDNA for segment 9 was determined with a Taq DyeDeoxy Terminator Cycle Sequence Kit (ABI). M13, M13Rev, 9F, and 9R were used as primers.

Expression of segment 9 in E. coli.

The cDNA of segment 9 of the BmCPV I strain was expressed in a bacterial system (pTrc-His) which produces fusion proteins with six His residues attached to the NH2 terminus. The cDNA of segment 9 was linearized with BamHI and EcoRI and separated by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. After being cut out of the gel, it was ligated to a BamHI- and EcoRI-digested pTrc-His-C expression vector (Invitrogen). Recombinant pTrc-His-C/BmCPV-S9 was then transfected into E. coli X-L1 blue. A single recombinant E. coli colony was cultivated in SOB containing ampicillin (50 μg/ml) at 37°C overnight. To increase the expression level of fusion protein, isopropylthio-β-d-galactoside at a final concentration of 1 mM was added to the culture medium, followed by further incubation at 37°C for 5 h with shaking.

Purification of polyhistidine-linked protein.

The purification of polyhistidine-tagged NS5 was carried out by using the Ni column of an Xpress System protein purification kit (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Immunization.

Two BALB/c mice were immunized with purified His-tagged NS5 fusion protein. One hundred micrograms of NS5 mixed with complete Freund’s adjuvant was employed as the first booster. The subsequent immunizations were carried out on successive weeks with 50, 30, and 30 μg of NS5 mixed with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant.

Construction of recombinant baculovirus.

cDNA of segment 9 of the I strain cloned in pBluescript KS(−) was excised with BamHI and EcoRI and ligated into the transfer vector pBM030, which was digested with BglII and EcoRI in advance. Restriction enzyme analysis and DNA sequencing were performed to confirm that the coding sequence of the segment 9 gene was correctly oriented with the baculovirus polyhedrin promoter. The resulting transfer plasmid and DNA of BmNPV T3 were cotransfected into BmN4 cells by lipofection (9). Six days thereafter, the culture medium was collected and recombinant viruses showing cytopathic effects but not polyhedral inclusion body production were isolated by the plaque assay method (16). For the expression of NS5, BmN4 cells infected with recombinant baculovirus were cultured in the presence of 2.5 μM benzamidine to inhibit serine protease activity.

Binding assay for NS5 using poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose.

Poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose (200 μl) (Pharmacia) was washed three times with buffer A, which was composed of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) containing 150 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM benzamidine, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40. Whole-cell extracts (107 cells) infected with recombinant baculovirus were added to the washed poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose, and the mixtures were incubated for 60 min at 4°C with occasional gentle mixing. Then, the poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose resin was pelleted by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min and washed three times with buffer A. The proteins bound to poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose were recovered by adding an equal volume of SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiling at 100°C for 5 min. For competition assays, the cell extracts were preincubated with 5 or 50 μg of BmCPV dsRNA for 60 min before being mixed with the poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose.

Fractionation of BmN4 cell lysates.

BmCPV-infected BmN4 cells (total of 107) were centrifuged at 600 × g for 1 min, washed twice with PBS, and suspended in 200 μl of 10 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.8) containing 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 2 μg of aprotinin per ml, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40. They were disrupted completely by being pipetted many times and then centrifuged at 600 × g for 1 min, and the supernatant (cytosolic fraction) and pellet (nuclear fraction) were collected as described by Dignam et al. (5).

SDS-PAGE.

Protein components in the cell homogenates of silkworm midgut and the BmN4 cell lysates (5 × 105 cells) were separated by SDS–12% PAGE under reducing conditions as described by Laemmli (14) and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. In some cases, purified polyhedra and virions were used instead of cell homogenates or cell lysates.

Western blotting.

After separation by SDS-PAGE, each protein was transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes as described by Towbin et al. (24). For blocking, the membranes were soaked in 1% gelatin in PBS overnight at room temperature. After three washings with PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100, incubation with antiserum for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation, and a further washing, a 1/5,000 dilution of goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (TAGO) was added, and the incubation was continued for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the membrane was washed five times with washing buffer and analyzed with a POD Immunostain SET (Wako).

Prediction of secondary structure.

The secondary structure of the NS5 molecule was predicted by the method of Chou and Fasman (3, 4).

Determination of protein concentration.

The protein concentration was determined as described by Lowry et al. (15) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Nucleotide sequence accession number. The nucleotide sequence data reported here for segment 9 of BmCPV strains I and H will appear in the GenBank database with accession no. AF061199 and AF061200.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of BmCPV segment 9.

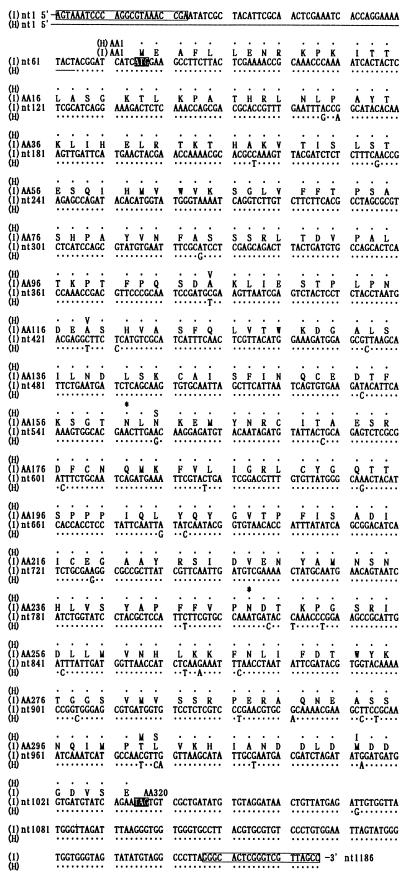

Figure 1 shows the strategy for sequencing segment 9 of BmCPV strains H and I. To minimize the sequencing errors for each clone, we carefully determined each nucleotide sequence by repetition in both the forward and reverse directions. As a result, the segment 9 viral gene was found to harbor 1,186 bp in both strains, encoding a protein of 320 amino acids with a deduced molecular mass of 36 kDa (Fig. 2). Here we term the protein encoded by segment 9 NS5, in line with the nomenclature used by McCrae and Mertens (18). The complete nucleotide sequences of segment 9 of the H and I strains were found to demonstrate 37 point differences, resulting, however, in only six amino acid replacements. The most marked variation was found in the N glycosylation sites: two putative N glycosylation sites were present at Asn 160 and Asn 247 in the H strain, whereas only one site was conserved at Asn 247 in the I strain, due to a single amino acid replacement, Ser 162 with Asn 162. Three point mutations resided in the COOH-terminal region between positions 301 and 313. Six Cys residues were found in the central region of the NS5 molecule at positions 143 to 217 in both strains.

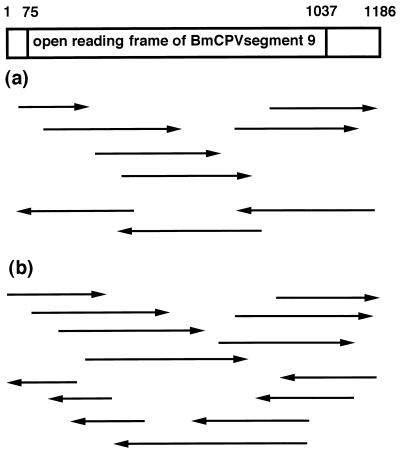

FIG. 1.

Strategy for sequencing segment 9 of BmCPV strain H (a) and strain I (b). Arrows pointing to the right indicate the plus strand of segment 9 of the viral genome, and those pointing to the left indicate the minus strand. Single clones from the H and I strains were sequenced.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of segment 9 from BmCPV strains H and I. Closed boxes show the initiation and termination codons, and open boxes indicate the 5′ and 3′ primer sequences. Asterisks indicate the putative N glycosylation sites. Single dots represent identical nucleotides (nt) and amino acids (AA) in the two strains.

Homology search and prediction of the secondary structure of NS5.

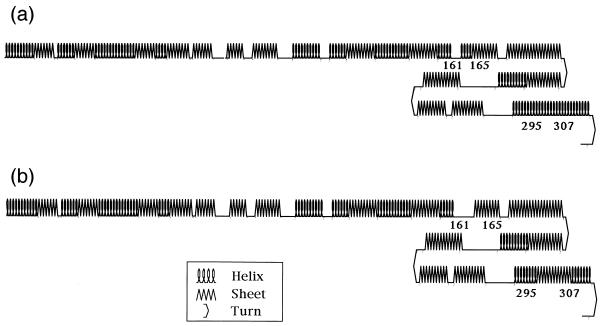

Results of a search for homology to NS5, encoded by BmCPV segment 9, are shown in Table 1. Localized homology with human poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase was noted. In particular, one of five motifs of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (10), YVKDELRS, was relatively well conserved in this protein molecule. The NH2-terminal region of NS5 encompassed three different basic amino acid domains: Arg-Lys-X-Lys, Lys-X-X-Lys, and Arg-X-Lys, appearing at residues 9 to 12, 20 to 23, and 42 to 44, respectively. The NS5 molecule also displayed similarity, up to 46%, to the carboxy-terminal region of rotavirus NS26, which is repeated in the 3′ untranslated region of bovine rotavirus VMRI (17). Figure 3 shows the results of prediction of the secondary structures of the two NS5 forms. Essentially, there was no fundamental discrepancy between the proteins in the H and I strains. However, the regions between residues 161 and 165 and between residues 295 and 307 were rich in α-helical structures in the H strain but rich in β-sheets in the I strain. These differences are presumably due to alteration in the amino acid residues at positions 162, 301, and 302.

TABLE 1.

Results of search for homology to NS5

| Comparison | Sequencea | Identity (%) | Similarity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BmCPV NS5 vs poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | 6 LENRKPKITTIASGKTLKP 24 | 42 | 57 |

| : :.:: . :: . : : | |||

| 93 LPNKKPNVPTIRTAKVQGP 111 | |||

| 26 THRLNLPAYTKLIHELRTKTHAKVTISLSTESQIHMDWVKSGLVF 70 | 33 | 48 | |

| :. .::: : . :::.:: . : :. : : . : | |||

| 438 TYGINLPLVTYVKDELRSKTKVEQGKSRLIEASSLNDSVAMRMAF 482 | |||

| 108 IESTPLPNDEASHVASFQLVTWKDG 132 | 36 | 48 | |

| : : : . :: : :. : .: | |||

| 692 IRWTKDPRNTQDHVRSLCLLAWHNG 716 | |||

| 118 ASHVASFQLVTWKD 131 | 42 | 71 | |

| : :.:. :::.. | |||

| 648 ADKSATFETVTWEN 661 | |||

| BmCPV NS5 vs human rotavirus NS26 | 249 TKPGSRIDLLMVNHLKKFNLIFDTWYKTGGSVMVSSRPERAQNEASAN | 21 | 46 |

| ..: : .. . :: . :. .:. :...:. | |||

| 97 SRPSSDIGYDQMDFSLNKGIKFDATVDSSISISTTSKKEKSKNKNKYK | |||

| QIMPTLVKHIANDDLDMDDGD 317 | |||

| . : . .:: .:: : | |||

| KCYPKIEAESDSDDYILDDSD 165 | |||

| 18 SGKTLKPATHRLNLPAYTKLIHELRTKTHAKVTISLSTESQ 58 | 24 | 46 | |

| : . . :. : : . : ::.: .:…: | |||

| 56 SPEDIGPSDSASNDPLTSFSIRSNAVKTNADAGVSMDSSAQ 96 |

In each set of sequences, the top sequence is that of NS5 and the bottom is that of the compared protein. Double and single dots indicate identical and similar amino acids, respectively. The underlined material is one of the five motifs of RNA polymerase.

FIG. 3.

Secondary structures of NS5 of BmCPV strain H (a) and strain I (b), predicted according to the method of Chou and Fasman (3, 4). The numbers represent boundary amino acid residues at a position where the secondary structure of the protein differs between the two strains.

Immunoblot analysis of NS5 molecules in host and BmN4 cells.

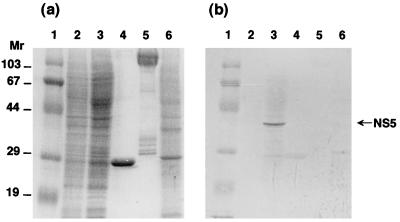

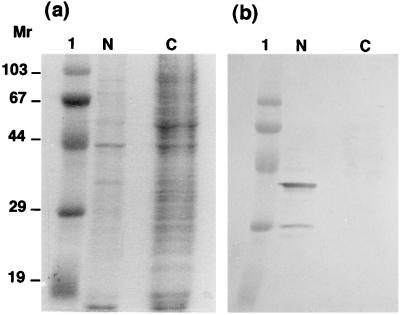

First, the location of NS5 in BmCPV strain I-infected midgut cells was examined. As shown in Fig. 4, the NS5 molecules were detected only in the homogenates of BmCPV strain I-infected midgut cells and not in purified virions (virus particles) or in polyhedra (inclusion bodies), which are known to include thousands of virions, indicating that NS5 is not a member of virions or inclusion bodies. Therefore, further analyses were performed with cultured BmN4 cells. BmN4 cells were infected with BmCPV, separated into cytosolic and nuclear fractions, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 5, NS5 was located predominantly in the nucleus. The smaller, 28-kDa component in Fig. 5 seemed to be a degradation product because it almost disappeared when 2.5 μM benzamidine, a potent serine protease inhibitor, was added to the culture medium.

FIG. 4.

Immunoblot analysis of NS5 with anti-NS5 antibody. Fifth-instar and 2-day-old larvae were infected with BmCPV strain I, and the infected midguts were collected 5 days after infection. They were homogenized with PBS, and the supernatant was collected after sedimenting cell debris by centrifugation. Uninfected midguts were prepared by the same procedure. BmNPV-infected BmN4 cells were also collected 5 days after infection, and the homogenates of 5 × 105 cells were used for further analysis. BmCPV polyhedra and virions were purified as described in Materials and Methods. Each sample was applied to an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel and subjected to electrophoresis, and protein was detected by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (a) and Western blot analysis (b). Lanes 1, molecular weight markers; lanes 2, uninfected midgut (control); lanes 3, BmCPV strain I-infected midgut; lanes 4, BmCPV strain I polyhedra (2.5 μg); lanes 5, BmCPV strain I virion (2.5 μg); lanes 6, BmNPV-infected BmN4 cells. Molecular weights are in thousands.

FIG. 5.

Localization of NS5 in BmN4 cells. BmCPV strain I-infected BmN4 cells were collected 5 days after infection, separated into cytosolic and nuclear fractions as described in Materials and Methods, and subjected to SDS-PAGE and detection by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (a) and Western blot analysis with anti-NS5 antibody (b). Lanes 1, N, and C show molecular weight markers and the nuclear and cytosolic fractions, respectively. Molecular weights are in thousands.

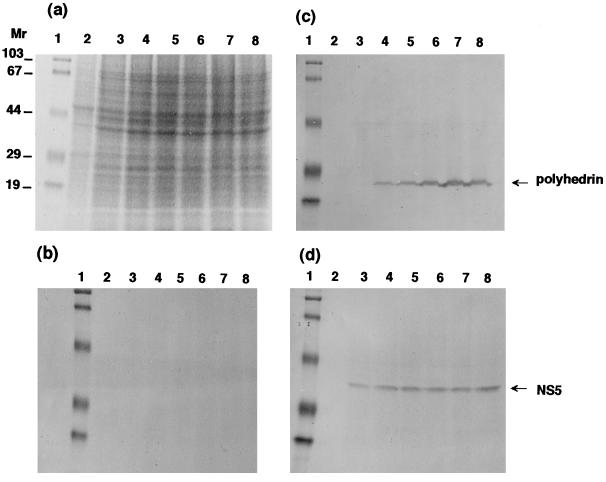

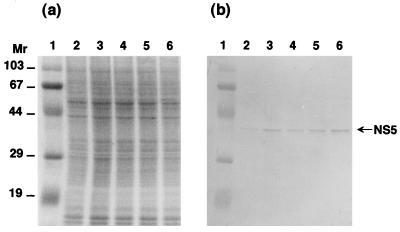

As shown in Fig. 6, marked differences in the expression period and level of NS5 and polyhedrin were established by analysis with anti-NS5 and antipolyhedrin antibodies. The polyhedral protein was first detected in BmN4 cells 2 or 3 days after virus infection, and the expression level increased as the infection progressed. In contrast, NS5 expression was almost constant until 6 days after infection: its synthesis started within a few hours of virus inoculation (Fig. 7). These results suggest that polyhedrin and NS5 are under completely separate regulatory control. The very early nature of NS5 expression is in line with the finding of homology with RNA binding protein motifs.

FIG. 6.

Time course of expression of NS5 and polyhedrin in BmCPV strain I-infected BmN4 cells. Infected BmN4 cells were collected 1 to 6 days after infection and subjected to SDS-PAGE and detection by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (a) and Western blot analysis with normal mouse serum (b), antipolyhedrin (c), and anti-NS5 (d) antibodies. Lanes 1 show molecular weight markers. Lanes 2 illustrate the results for uninfected control BmN4 cells. Lanes 3 to 8 show results obtained 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 days after infection, respectively. Homogenates of 5 × 105 cells were used for analysis. Molecular weights are in thousands.

FIG. 7.

Time course of expression of NS5 in BmCPV strain I-infected BmN4 cells. Infected BmN4 cells were collected at 1 to 18 h after infection and subjected to SDS-PAGE and detection by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (a) and Western blot analysis with anti-NS5 antibody (b). Lanes 1 show molecular weight markers. Lanes 2 to 6 show results obtained 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 h after infection, respectively. Homogenates of 5 × 105 cells were used for analysis. Molecular weights are in thousands.

Binding assay for NS5 expressed in BmN4 cells by using poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose.

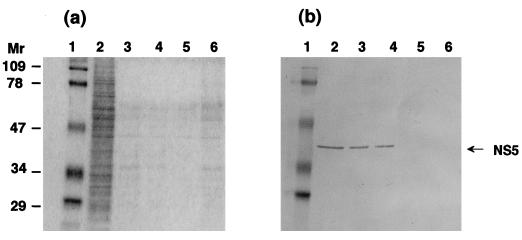

As NS5 had localized similarities to human poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, its binding to dsRNA was examined. For this, a baculovirus expression system was used, because no specific proteins cross-reacted with anti-NS5 antibody in BmNPV-infected BmN4 cells even 5 days after infection (Fig. 4b). NS5 was expressed by using this system in the presence of 2.5 μM benzamidine, and whole-cell extracts containing NS5 were added to poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose. As shown in Fig. 8, NS5 specifically bound to poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose and the addition of the BmCPV dsRNA genome competed for the binding of NS5 to poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose. These results suggest that NS5 has an ability to bind to viral dsRNA.

FIG. 8.

Assay for binding of NS5 to poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose. BmN4 cells were infected with recombinant BmNPV in the presence of benzamidine and collected 5 days after infection. Then the whole-cell extracts (107 cells) were mixed with poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose, and the proteins bound to the poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose were analyzed by Coomassie brilliant blue staining (a) and Western blotting (b) after SDS-PAGE. For competition assays, cell extracts were pretreated for 60 min at 4°C with 5 or 50 μg of viral dsRNA before being mixed with poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose. Lanes 1 show molecular weight markers. Lanes 2 show the whole-cell extracts infected by recombinant BmNPV. Lanes 4 and 5 show proteins bound to the poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose in the presence of 5 and 50 μg of viral dsRNA, respectively, and lanes 3 show protein binding in its absence. Lanes 6 show the proteins bound to agarose without poly(rI) · poly(rC) ligand.

DISCUSSION

The present study clarified the complete nucleotide sequences of segment 9, 1 of 10 discrete segments in the BmCPV dsRNA genome, and demonstrated high similarity between strains H and I. The open reading frame in each case was assumed to begin at nucleotide 75. The AXXATGG Kozak consensus sequence (11, 12) was noted at the sequence around nucleotide 75, consistent with the polyhedrin gene of segment 10 of BmCPV, which also demonstrates the same consensus sequence for the initiation codon (1). Only six differences in amino acid residues were noted for the proteins produced in the two strains. In strain I, the replacement of Ser 162 with Asn 162 resulted in the disappearance of one of two putative N glycosylation sites, but this did not affect the apparent molecular mass of NS5 or immunological recognition by anti-NS5 antibodies (data not shown).

It is of interest that NS5 has four regions highly homologous with human poliovirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. In particular, the sequence from residues 36 to 43 of NS5 showed 63% similarity to the motif of the enzyme and was conserved in the protein of both the H and I strains. The NS5 molecule did not contain GDD, a sequence of the NTP-binding site (6) which is highly conserved in most RNA-dependent RNA polymerases, especially in single-stranded RNA and dsRNA viruses (2). Instead, the NDD and IDD sequences were found in the carboxy-terminal region of the H strain NS5 protein and NDD and MDD sequences were found in the I strain NS5 protein. The MDD motif, occasionally replaced with IDD, is reported to be conserved in retrovirus reverse transcriptases (22). Other areas of homology of NS5 with NS26 of human rotavirus, which harbors the same dsRNA as a genome, were found, with 46% similarity of the carboxy-terminal region at positions 249 to 317. This sequence is repeated in the 3′ untranslated region of bovine rotavirus VMRI (17).

The present finding that there are marked differences in the expression of polyhedrin and NS5 in BmN4 cells with regard to both the expression period and cellular localization suggests that they are under separate regulatory control. The polyhedrin molecule is a major constituent of water-insoluble polyhedra which exists in the cytoplasm (8), whereas the NS5 molecule was established to be located mainly in the nucleus. In addition, segment 9 has 74 nucleotides in the 5′ noncoding region, whereas the polyhedrin gene has only 41 (1, 23). A computer program, PSORT (20), indicated that there is a possible nuclear localization signal at positions 9 to 12 in the NS5 molecule (7). This localization could be related to the early expression and a role in regulation of the BmCPV genome.

When the NS5 molecule was expressed with a baculovirus expression system, it bound to poly(rI) · poly(rC)-agarose, and the dsRNA genome of BmCPV was a competitor for this, suggesting that NS5 has the ability to bind to viral dsRNA.

In conclusion, the present study showed that NS5 is expressed at an early stage after viral infection and binds to the dsRNA genome. Its homology with known regulatory elements, nuclear location, and constant expression level suggest that it could contribute to regulation of gene expression in BmCPV and enhance its multiplication in host cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Malcolm Moore for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arella M, Lavallee C, Belloncik S, Furuichi Y. Molecular cloning and characterization of cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus polyhedrin and a viable deletion mutant gene. J Virol. 1988;62:211–217. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.1.211-217.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruenn J A. Relationships among the positive strand and double-strand RNA viruses as viewed through their RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:217–226. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.2.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou P Y, Fasman G D. Prediction of protein conformation. Biochemistry. 1974;13:222–245. doi: 10.1021/bi00699a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou P Y, Fasman G D. Empirical predictions of protein conformation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1978;47:251–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.47.070178.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dignam J D, Lebovitz R M, Roeder R G. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dolja V V, Carrington J C. Evolution of positive-strand RNA viruses. Semin Virol. 1992;3:315–326. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hicks G R, Raikhel N V. Protein import into the nucleus: an integrated view. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:155. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.001103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hukuhara T, Midorikawa M. Pathogenesis of cytoplasmic polyhedrosis in the silkworm. In: Compans R W, Bishop D H L, editors. Double-stranded RNA viruses. New York, N.Y: Elsevier Science; 1983. pp. 405–414. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi J, Belloncik S. Efficient lipofection method for transfection of silkworm cell line, NISES-BoMo-15AIIc, with the DNA genome of the Bombyx mori nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J Seric Sci Jpn. 1993;62:523–526. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koonin E V. Evolution of double-stranded RNA viruses: a case for polyphyletic origin from different groups of positive-stranded RNA viruses. Semin Virol. 1992;3:327–339. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kozak M. Possible role of flanking nucleotides in recognition of the ATG initiator codon by eukaryotic ribosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:5233–5252. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.20.5233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozak M. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell. 1986;44:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuchino Y, Nishimura S, Smith R E, Furuichi Y. Homologous terminal sequences in the double-stranded RNA genome segments of cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus of the silkworm Bombyx mori. J Virol. 1982;44:538–543. doi: 10.1128/jvi.44.2.538-543.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maeda S. Gene transfer vectors of a baculovirus, Bombyx mori nuclear polyhedrosis virus, and their use for expression of foreign genes in insect cells. In: Mitsuhashi J, editor. Invertebrate cell system applications. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1989. pp. 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsui S M, Mackow E R, Matsuno S, Paul P S, Greenberg H B. Sequence analysis of gene 11 equivalents from “short” and “super short” strains of rotavirus. J Virol. 1990;64:120–124. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.1.120-124.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCrae M A, Mertens P P C. In vitro translation studies on and RNA coding assignments for cytoplasmic polyhedrosis viruses. In: Compans R W, Bishop D H L, editors. Double-stranded RNA viruses. New York, N.Y: Elsevier Science; 1983. pp. 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mori H, Minobe Y, Sasaki T, Kawase S. Nucleotide sequence of the polyhedrin gene of Bombyx mori cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus A strain with nuclear localization of polyhedra. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:1885–1888. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-7-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakai K, Kanehisa M. A knowledge base for predicting protein localization sites in eukaryotic cells. Genomics. 1992;14:897–911. doi: 10.1016/S0888-7543(05)80111-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakazawa H, Kendirgi F, Belloncik S, Ito R, Takagi S, Minobe Y, Higo K, Sumida M, Matsubara F, Mori H. Effect of mutation on the intracellar localization of Bombyx mori cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus polyhedrin. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:147–153. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-1-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poch O, Sauvaget I, Delarue M, Tordo N. Identification of four conserved motifs among the RNA-dependent polymerase encoding elements. EMBO J. 1989;8:3867–3874. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomita M, Kobayashi J, Mori A, Hagiwara K, Nakai K, Suzuki Y, Miyajima S. Genetic analysis on morphological differences in the occlusion body of Bombyx mori cytoplasmic-polyhedrosis virus. Protein Eng. 1994;7:1156. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]