Abstract

The vaccinia virus A32 open reading frame was predicted to encode a protein with a nucleoside triphosphate-binding motif and a mass of 34 kDa. To investigate the role of this protein, we constructed a mutant in which the original A32 gene was replaced by an inducible copy. The recombinant virus, vA32i, has a conditional lethal phenotype: infectious virus formation was dependent on isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Under nonpermissive conditions, the mutant synthesized early- and late-stage viral proteins, as well as viral DNA that was processed into unit-length genomes. Electron microscopy of cells infected in the absence of IPTG revealed normal-appearing crescents and immature virus particles but very few with nucleoids. Instead of brick-shaped mature particles with defined core structures, there were numerous electron-dense, spherical particles. Some of these spherical particles were wrapped with cisternal membranes, analogous to intracellular and extracellular enveloped virions. Mutant viral particles, purified by sucrose density gradient centrifugation, had low infectivity and transcriptional activity, and the majority were spherical and lacked DNA. Nevertheless, the particle preparation contained representative membrane proteins, cleaved and uncleaved core proteins, the viral RNA polymerase, the early transcription factor and several enzymes, suggesting that incorporation of these components is not strictly coupled to DNA packaging.

Vaccinia virus (VV), the prototype poxvirus, replicates within the cytoplasm and has a linear double-stranded DNA genome of 185 kbp with inverted terminal repeats (16, 50) and covalently linked ends (2, 17). Approximately 185 open reading frames (ORFs) are likely to encode proteins, though the functions of less than half of these are known (21, 36). Some insights into protein function have come from comparative sequence analysis. Eight VV ORFs (A18, A32, A48, D5, D6, D11, I8, and J2) have predicted purine nucleoside triphosphate binding motifs (18, 27, 28), and there is evidence that most of the corresponding proteins have roles in transcription, replication, alteration of DNA topology, or nucleotide metabolism. Of these proteins, least is known about the A32 gene product. Based on limited sequence similarity to the products of gene I of filamentous, single-stranded DNA bacteriophages and to the Iva2 gene of adenovirus, Koonin et al. (28) suggested that the A32 gene product may be an ATPase involved in DNA packaging. In addition, a highly conserved function was predicted from the degree of similarity of the deduced amino acid sequences of the VV A32 protein to its homolog in the distantly related molluscum contagiosum virus (43, 44).

In the absence of any experimental data regarding the expression or role of the VV A32 gene, we have taken an in vivo genetic approach to the subject. Here we describe the construction and properties of a conditional lethal mutant of VV with an inducible A32 gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

BS-C-1 (ATCC CCL6) and HeLa S3 cells (ATCC CCL2.2) were grown in Eagle’s minimal essential medium (Quality Biologicals) and in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (Quality Biologicals), respectively, each supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Wild-type and recombinant VV (rVV) were derived from the WR strain (ATTC Vr119). To prepare stocks of vA32i, monolayers of HeLa S3 cells were infected with 3 PFU of virus per cell in the presence of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and 2% FBS. Originally, 50 μM IPTG was used but subsequently 15 μM was found to produce higher yields of virus. Virus seed stocks were prepared by freeze-thawing infected cells at 72 h after infection. Partially purified virus, prepared by centrifugation through a 36% sucrose cushion (12), was routinely used to infect cells for experiments.

Plasmid construction.

A copy of the A32 ORF was amplified by PCR with cosmid pWR 120-150 (47) as the template and oligonucleotide primers 5′-GGGGGGATCCTTATGATGATACATTTTTTGACG (BamHI site underlined) and 5′-GGGGCATATGAATTGTTTCCAAGAAAAAC (NdeI restriction site underlined; initiation codon in boldface). The PCR product was digested with BamHI and NdeI and inserted into plasmids pVOTE.2 (49) and pET-14b (Novagen), generating pVOTE/A32 and pET-14/A32, respectively.

A 410-bp copy of the region preceding the A32 gene (right flank) was generated by PCR by using cosmid pWR 120-150 and oligonucleotide primers 5′-GGGGAAGCTTTCTTTGTGATCATATTGTGTAGTG and 5′-GGGGGTCGA CTTACAGTTACTAAATTAATTTGATA containing HindIII and SalI restriction sites (underlined), respectively. The PCR product was digested with HindIII and SalI and inserted into the plasmid pZippy-neo/gus (gift of T. Shors) upstream of the neomycin gene to generate pA32RF-neo/gus. A 400-bp copy of the region following the A32 gene (left flank) was generated by PCR by using cosmid pWR 120-150 and oligonucleotide primers 5′-GGGGAGATCTGGACATTTTTAACATGGCATCTATT and 5′-GGGGGAGCTCGTGCAATAGCGATCAATCATCGTCG containing BglII and SstI restriction sites (underlined), respectively. The PCR product was digested with HindIII and SalI and inserted into the plasmid pA32RF-neo/gus downstream of the gus gene to generate pA32RF-neo/gus-LF.

Generation of rVV.

vA32i was constructed in two steps. First, an intermediate vA32/A32i was generated by homologous recombination between vT7lacOI (1) and pVOTE/A32. Approximately 106 BS-C-1 cells were infected with 5 × 104 PFU of vT7lacOI. After 1 h at 37°C, the cells were washed twice with Opti-Mem (Life Technologies) and transfected with 2 μg of pVOTE/A32 mixed with Lipofectin (Life Technologies). After 4 h the transfection mixture was removed and regular medium was added. The cells were harvested after 48 h, frozen and thawed thrice, and sonicated for 30 sec. rVV were then selected by three rounds of plaque purification in the presence of mycophenolic acid, xanthine, and hypoxanthine (12). Small virus stocks were prepared, and the recombinational changes were confirmed by PCR and gel electrophoresis.

The inducible vA32i was generated by homologous recombination between vA32/A32i and pA32RF-neo/gus-LF. The procedure was the same one used to make vA32/A32i except that the selection of the rVV was carried out in the presence of 50 μM IPTG, G418 (0.64 mg/ml; Life Technologies), and 4 mM HEPES (pH 7.4; Life Technologies). The rVV plaques were identified by staining with X-Glu (0.2 mg/ml; Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, Calif.) (6). Small virus stocks were prepared, and the DNA was analyzed by PCR and gel electrophoresis.

Plaque assay.

BS-C-1 cell monolayers, in six-well plates, were infected with 10-fold serial dilutions of VV. After a 1-h adsorption, the cells were incubated at 37°C for 2 days in Eagle’s minimal essential medium supplemented with 2% FBS and 50 or 15 μM IPTG as specified. The cells were then stained with crystal violet, and the plaques were counted.

One-step virus growth.

BS-C-1 cells were infected with 10 PFU of virus per cell for 1 h at 37°C. The incubation was continued with or without 50 μM IPTG, and the cells were harvested at various times, frozen and thawed three times, sonicated, and stored at −80°C. Virus titers were determined by plaque assay in the presence of 50 μM IPTG.

Antibody preparation.

Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLysS (Novagen) was transformed with pET-14/A32; synthesis of the recombinant 6-histidine fusion protein was induced with IPTG as described above (Novagen). The lysate was heated with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and mercaptoethanol, and the A32 protein band was resolved by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The band containing the induced protein was excised from the gel, crushed, mixed with Ribi adjuvant (Ribi Immunochemical Research, Inc.) and injected into New Zealand White rabbits. Boosts of antigen with adjuvant were given every 21 days. Serum obtained at 8 weeks was reactive with the A32 protein as determined by Western blotting of lysates of cells infected with vA32i in the presence of 50 μM IPTG.

Immunoprecipitation and SDS-PAGE analysis of [35S]methionine-labeled polypeptides.

BS-C-1 cells were infected with 15 PFU of virus per cell in the presence or absence of 50 μM IPTG. At the indicated times after infection, the cells were incubated with methionine-free medium for 15 min, pulse-labeled for 30 min with 100 μCi of [35S]methionine per ml, harvested in 1% SDS–50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), and incubated at 85°C for 3 min. One portion was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and another portion was diluted with 10 volumes of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–150 mM NaCl–1% Nonidet P-40 and incubated for 12 h with 15 μl of polyclonal antiserum raised against the A32 protein. The antigen-antibody complex was then bound to protein A beads as previously described (7).

For pulse-chase analysis, BS-C-1 cells were infected with 10 PFU of virus per cell. IPTG (15 μM) or rifampin (100 μg/ml) was used as specified. After 9 h of infection, the cells were starved with methionine-free medium for 15 min, pulse-labeled for 30 min with 100 μCi of [35S]methionine per ml, and then incubated in medium containing unlabeled methionine for 12 h.

Analysis of viral DNA.

Monolayers of BS-C-1 cells were infected with 10 PFU of VV per cell in the presence or absence of 50 μM IPTG. At various times after infection, the cells were harvested, sedimented, rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline, resuspended in 50 μl of 0.15 M NaCl–0.02 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–0.01 M EDTA, and added to 250 μl of 0.02 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–0.01 M EDTA–0.75% SDS–0.4 mg of proteinase K per ml. After 6 h at 37°C, the samples were phenol extracted and then ethanol precipitated. The precipitates were suspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–1 mM EDTA, passed through a 25-gauge needle, and digested with BstEII at 37°C. The digests were electrophoresed through agarose, transferred to nitrocellulose, probed with a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide complementary to a fragment of the 70-bp tandem repeats, and autoradiographed.

To analyze full-length DNA, monolayers of BS-C-1 cells were infected with 1 PFU of VV per cell. After 24 h, the cells were harvested and resuspended in cell suspension buffer (Bio-Rad Genomic DNA Plug Kit) at 107 cells/ml. An equal volume of 2% CleanCut agarose (Bio-Rad) preincubated at 50°C was added, and the cell suspension was formed into 100-μl plugs. After solidification at 4°C, the plugs were treated with proteinase K as previously described (33). The equilibrated agarose plugs were subjected to electrophoresis on a Bio-Rad CHEF DRII apparatus for 22 h at 6 V/cm with a switching time of 70 s. The agarose gel was transferred onto a Nytran membrane (Schleicher and Schuell), and DNA was detected by hybridization with an ECL kit with VV genomic DNA labeled by random priming as suggested by the manufacturer (Amersham).

Purification of viral particles and DNA analysis.

Monolayers of HeLa S3 cells were infected with 3 PFU of VV per cell. Cells were harvested 72 h after infection, and the cell-associated viral particles were purified through a 36% sucrose cushion and two consecutive bandings on a 24 to 40% sucrose gradient as previously described (11). A volume of 2 μl of every other fraction of the second sucrose gradient was diluted in 50 μl of H2O and applied to a nylon membrane (Hybond-N+; Amersham) in a vacuum manifold. The membrane was blotted three times on filter paper saturated with 0.5 M NaOH, then three times on paper saturated with 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–1.5 M NaCl, and then three times on paper saturated with 2× SSC (0.3 M NaCl, 0.03 M sodium citrate). The DNA was UV cross-linked to the membrane with a Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene). The probe was prepared by 5′-end 32P labeling five 30-mer oligonucleotides complementary to representative regions of the VV genome. Hybridization was carried out by using the QuikHyb protocol (Stratagene).

Western blot analysis.

Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore) and probed with the specified antibody. The membranes were then incubated with 125I-labeled protein A and autoradiographed. Radioactivity was quantified with a PhosphorImager (Storm 860; Molecular Dynamics).

In vitro transcription.

Purified viral particles were incubated in 60 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.05% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40, 5 mM ATP, 1 mM GTP, 1 mM CTP, 0.02 mM UTP, and 5 μCi of [α-32P]UTP. The amount of incorporation of [α-32P]UMP into RNA retained on DE-81 paper was determined (4).

Indirect immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy.

Viral particles were bound to coverslips and prepared for confocal microscopy essentially as described previously (48) except that 0.05% saponin in phosphate-buffered saline was used to permeabilize the viral particles and as diluent for the antibody. The primary antibody was rabbit polyclonal anti-VV antiserum 8191 (provided by L. Potash), and the second antibody was rhodamine-conjugated swine anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Dako Corp., Carpinteria, Calif.). Samples were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Labs, Inc., Burlingame, Calif.) containing 1 μg of DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) per ml. Samples were analyzed with a Zeiss LSM 410 confocal microscope.

Electron microscopy.

BS-C-1 cells were infected with mutant or wild-type VV at a multiplicity of infection of 10. After 24 h, the cells were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Na cacodylate (pH 7.4) buffer. Purified viral particles were incubated with an equal volume of 4% glutaraldehyde in 0.2 M Na cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) and collected by centrifugation at 14,000 × g in a microcentrifuge. Samples were embedded in Embed-812 (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, Pa.) as previously described (51). Ultrathin sections of infected cells and virions were viewed with a Philips CM100 electron microscope.

RESULTS

Construction of an rVV with the A32 gene regulated by the E. coli lac repressor.

The A32 gene contains a typical late promoter consensus sequence and an ORF that predicts a nonmembrane protein of 34.4 kDa. Our attempts to ablate the A32 gene by insertion of antibiotic selection and color markers into the ORF were unsuccessful (data not shown), suggesting that the encoded protein is essential for replication in BS-C-1 cells. The E. coli lac repressor system was previously used to regulate expression of VV late genes (15, 41, 53). In an improved version of the system (49, 51), the rVV contains (i) the lacI gene under control of a constitutive VV promoter, (ii) the bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase gene regulated by a VV late-stage promoter with a lacO, and (iii) the target gene regulated by a T7 promoter with a lacO. High stringency is achieved because lac repressor molecules simultaneously inhibit the synthesis of T7 RNA polymerase and the transcription of the target gene by T7 RNA polymerase.

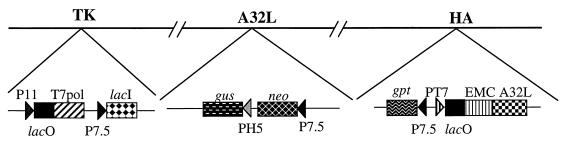

To regulate the A32 gene, an rVV was constructed in two steps, starting with a parental virus (vlacOI) that contains the lacI and T7 RNA polymerase genes. First, a cassette composed of a copy of the A32 gene and the E. coli gpt gene (for mycophenolic acid selection) was inserted into the VV hemagglutinin locus by homologous recombination. The resulting virus, vA32/A32i, contains the original A32 gene plus an inducible copy. In the second step, the original A32 ORF (except for the last 46 bp) of vA32/A32i was deleted by homologous recombination by using a plasmid that contains the neo and gus genes (for antibiotic selection and color screening, respectively) between sequences preceding and following the A32 gene. The resulting virus, vA32i, retained only the inducible copy of the A32 gene (Fig. 1). The genomic alterations of both viruses were confirmed by PCR and gel electrophoresis (data not shown). The ability to delete the A32 gene from the vA32/A32i indicated that our failure to delete this gene from wild-type virus when using the same neo-gus plasmid was due to the essential nature of the gene and not to other factors.

FIG. 1.

Repression of the A32 gene. Portions of the genome of the VV mutant vA32i are represented. DNA insertions have been made into the VV thymidine kinase (TK), A32L, and hemagglutinin (HA) genes. Abbreviations: P7.5, P11, and PH5 are VV promoters; PT7 and T7pol are a bacteriophage T7 promoter and the RNA polymerase gene, respectively; EMC is a cDNA copy of the untranslated RNA leader of encephalomyocarditis virus which provides cap-independent translation; lacI and lacO are the E. coli lac repressor gene and the lac operator, respectively; gus is a color marker gene; neo and gpt are antibiotic selection genes.

Replication of mutant viruses.

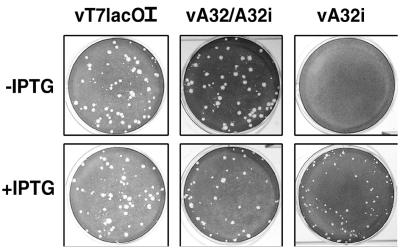

Virus replication and cell-to-cell spread in the presence or absence of IPTG were determined by plaque assay. Both vT7lacOI and vA32/A32i, each containing an unregulated A32 gene, formed plaques in the presence or absence of 50 μM IPTG. In contrast, vA32i, with only an inducible copy of the A32 gene, required IPTG for plaque formation (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Inducer dependence of plaque formation. BS-C-1 monolayers were infected with the mutant VVs vT7LacOI, vA32/A32i, or vA32i in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 50 μM IPTG. After 2 days, the cells were stained with crystal violet and photographed.

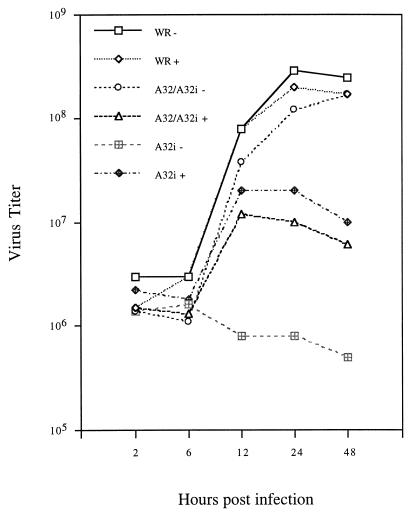

Virus yields in the presence or absence of IPTG were determined under one-step virus growth conditions. Wild-type VV strain WR, henceforth called WR, and vA32/A32i replicated in the presence or absence of 50 μM IPTG, whereas vA32i replicated only in the presence of inducer (Fig. 3). Subsequent experiments showed that the A32 gene is overexpressed at 50 μM IPTG and that severalfold-higher yields of vA32i were obtained with 10 to 15 μM IPTG. Because 50 μM IPTG also decreased the yield of vA32/A32i but not WR (Fig. 3), the effect was caused by overexpression of the A32 gene and not by nonspecific effects of the inducer.

FIG. 3.

Inducer-dependent formation of infectious virus. BS-C-1 monolayers were infected with the viruses indicated at a multiplicity of 5 PFU per cell in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 50 μM IPTG. At intervals of up to 48 h, the cells were harvested and the virus titers were determined by plaque assay. For A32i, 50 μM IPTG was included in the plaque medium.

Synthesis and processing of viral proteins.

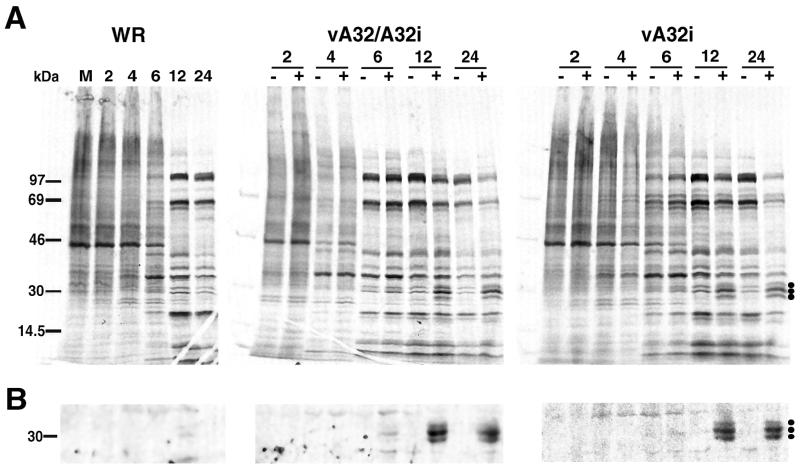

The pattern and timing of viral protein synthesis were investigated by SDS-PAGE analysis of infected cells that were pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine. Although VV early-stage proteins are difficult to resolve from the cellular background bands, VV late-stage proteins are clearly discerned because host protein synthesis is inhibited late in infection. In the absence of IPTG, the pattern of protein synthesis was similar in cells infected with WR, vA32/A32i, or vA32i (Fig. 4A). Consequently, the defect in replication of vA32i was not due to a general reduction in viral gene expression. On the contrary, in the presence of 50 μM IPTG, there was an overall decrease in [35S]methionine incorporation at 12 and 24 h after infection of cells with vA32/A32i or vA32i. The reduction in protein synthesis may account for the decreased virus yield at this IPTG concentration (Fig. 3). The only exceptions to the decrease in [35S]methionine labeling at high IPTG concentrations were the bands of approximately 30 kDa marked by dots in Fig. 4A. The proteins comprising these bands were identified as A32 gene products by their binding to rabbit antiserum raised against the recombinant protein synthesized in E. coli (Fig. 4B). The A32 protein was not present in sufficient amounts to detect in cells infected with vA32i or vA32/A32i in the absence of inducer or in cells infected with WR.

FIG. 4.

Protein synthesis in cells infected with wild-type and mutant viruses. BS-C-1 cells were infected with WR, vA32/A32i, or vA32i at a multiplicity of 15 PFU per cell in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 50 μM IPTG. At the indicated hours after infection, the cells were labeled for 30 min with [35S]methionine. (A) Cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The dots on the right indicate the bands of approximately 30 kDa that were increased in the presence of IPTG. (B) The labeled proteins that bound to beads containing antibody to the A32 protein were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Only the portion of the autoradiograph containing proteins of approximately 30 kDa is shown.

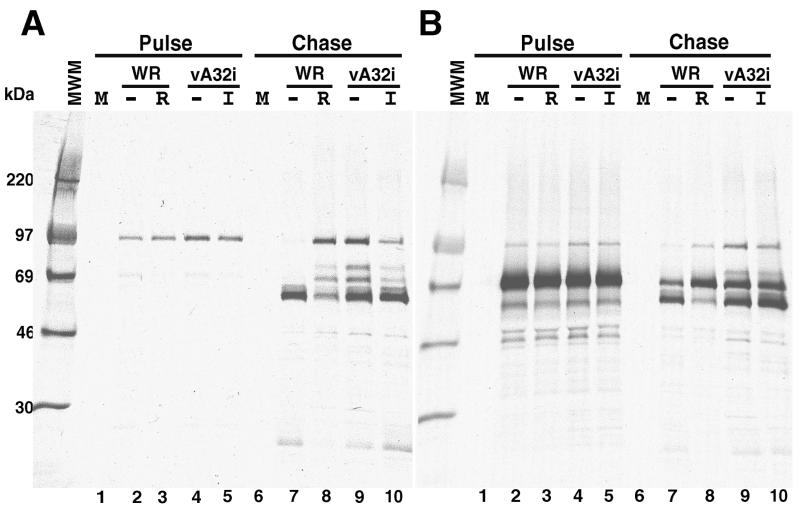

The synthesis and proteolytic processing of the 102-kDa P4A (ORF A10) and the 73-kDa P4B (ORF A3) precursors to form the core proteins 4A and 4B were examined by pulse-chase analysis and immunoprecipitation with specific antisera. Cells were infected with vA32i in the presence or absence of IPTG. As a control, other cells were infected with WR in the presence or absence of the drug rifampin, which blocks assembly-related proteolytic processing events (26, 37). The proteins were labeled with [35S]methionine for 30 min at 9 h postinfection and then chased for 12 h with excess methionine. Pulse-labeling indicated that P4A (Fig. 5A, lanes 2 to 5) and P4B (Fig. 5B, lanes 2 to 5) were synthesized in similar amounts by both viruses under permissive or nonpermissive conditions. Rifampin largely prevented the processing of P4A (Fig. 5A, lanes 7 and 8) and P4B (Fig. 5B, lanes 7 and 8). In cells infected with vA32i, processing of P4A was more efficient in the presence of IPTG than in its absence (Fig. 5A, lanes 9 and 10). IPTG also enhanced the processing of P4B, although the effect was small (Fig. 5B, lanes 9 and 10). These results suggested that inhibition of A32 gene expression delayed or partially blocked proteolytic processing of core protein precursors.

FIG. 5.

Proteolytic processing of core precursors. BS-C-1 cells were infected with WR in the presence or absence of 100 μg of rifampin per ml or with vA32i in the presence or absence of 15 μM IPTG. At 9 h after infection, the cells were labeled with [35S]methionine for 30 min, washed, and incubated with medium containing excess methionine for 12 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibody to 4A (panel A) or 4B (panel B) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Autoradiographs are shown. MWM, molecular weight markers; M, mock-infected cells; WR, wild-type VV-infected cells in the absence (−) or presence (R) of rifampin; vA32i, mutant VV-infected cells in the absence (−) or presence (I) of IPTG.

Synthesis and processing of viral DNA.

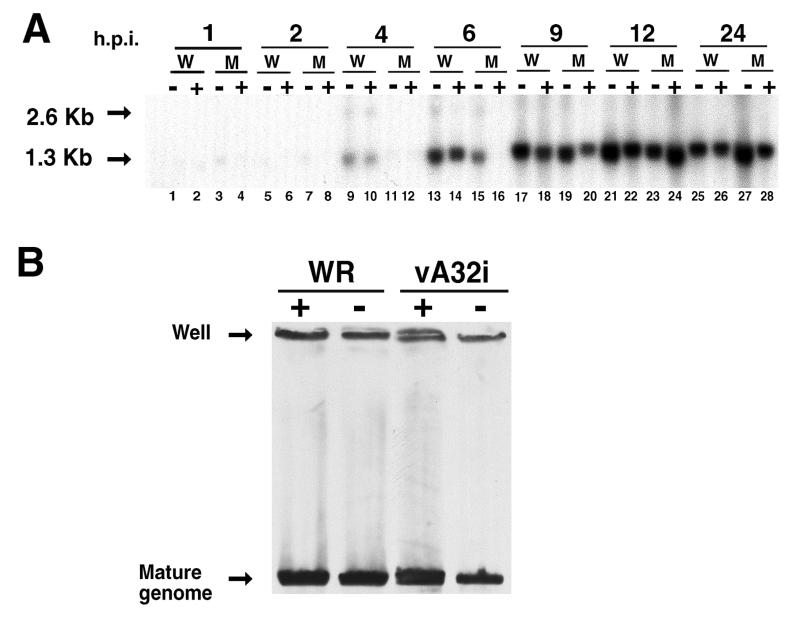

The synthesis of viral DNA was determined by blotting of restriction digests of total DNA from cells infected with wild-type or mutant virus in the presence or absence of IPTG and probing with a radiolabeled oligonucleotide complementary to the repeat sequence near the ends of the VV genome. Because the BstEII restriction endonuclease cleaves 1.3 kbp from each end of the unit-length mature genome, fragments of 2.6 kbp are formed by cleavage of concatemeric molecules (3). Viral DNA accumulated primarily from 6 to 12 h after infection (Fig. 6A). At all times, the predominant band was 1.3 kbp, indicating efficient formation of unit-length genomes even when expression of the A32 gene was repressed. Only trace amounts of the 2.6-kbp fragment were detected, a finding consistent with normal rapid processing of DNA concatemers.

FIG. 6.

Synthesis and processing of VV DNA. (A) At the indicated hours postinfection (h.p.i.) in the presence (+) or absence (−) of IPTG, total DNA was purified, digested with the restriction endonuclease BstEII, electrophoresed through agarose, transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond-N+; Amersham), and probed with a radiolabeled oligonucleotide corresponding to the repeat sequence near the ends of the genome. W and M, wild-type and mutant vA32i, respectively. The arrows at 1.3 and 2.6 kb point to the fragments corresponding to the ends of mature genomes and the bridge between units of concatemeric DNA molecules, respectively. (B) Total DNA from cells infected with WR or vA32i was resolved by pulse-field gel electrophoresis and analyzed by Southern blotting. + and −, presence or absence of IPTG during infection.

The formation of unit-length VV genomes in cells infected with wild-type or mutant virus in the presence or absence of IPTG was directly demonstrated by pulse-field gel electrophoresis and Southern blotting (33) (Fig. 6B). Material remaining at the site of DNA application has been previously noted and may represent branched or concatameric forms. We concluded that expression of the A32 gene was not required for replication or processing of VV DNA.

Morphogenesis of VV.

The partial inhibition of processing of the core protein precursors in cells infected with vA32i in the absence of IPTG suggested a defect in morphogenesis. Several stages of VV assembly have been defined by electron microscopy (10, 46). The first discrete viral structures are crescents which evolve into round (actually spherical) immature virions (IV), some of which contain eccentrically positioned small dense nucleoids. The IV condense to become brick-shaped intracellular mature virions (IMV) with defined dumbbell-shaped cores which are infectious if released from cells by lysis. Subsequently, some IMV are wrapped by membrane cisternae to form intracellular enveloped virions. Extracellular enveloped virions are released by fusion of the intracellular enveloped virions with the plasma membrane.

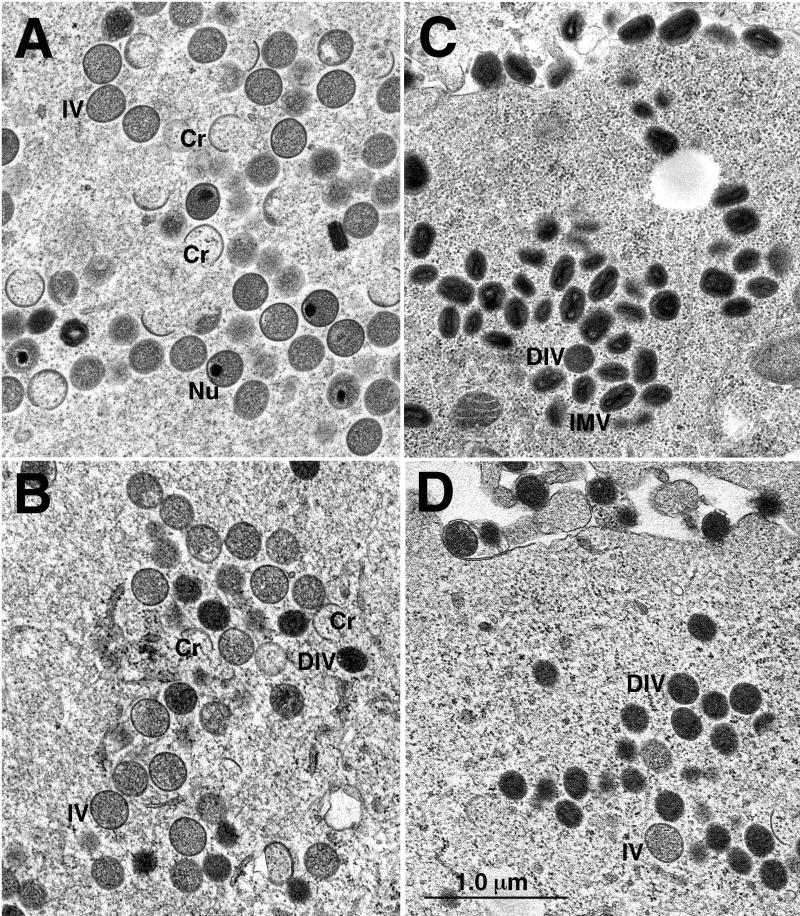

Electron microscopic images suggested that morphogenesis through the stage of IV was similar in cells infected productively with vA32/A32i or abortively with vA32i in the absence of IPTG. Differences were noted, however, in later stages of virus development. In cells abortively infected with vA32i for 24 h (Fig. 7B), IV with nucleoids were infrequent (3 nucleoids per 462 IV) compared to the number in cells productively infected with vA32/A32i (89 nucleoids per 510 IV) (Fig. 7A). Because IV are approximately 300 to 350 nm in diameter and ultrathin sections are 80 to 100 nm thick, the number of nucleoids is underrepresented. Serial sectioning suggests that the true number is three or more times higher (35). Therefore, we suspect that the actual proportion of IV with nucleoids is about 52% and less than 2% in cells infected in the absence of IPTG with vA32/A32i and vA32i, respectively. Since nucleoids contain viral DNA, this result suggested either that the DNA was not packaged in IV or that the packaged DNA did not have a nucleoid structure. In contrast to the deficiency of IV-associated nucleoids, many large cytoplasmic DNA crystalloids which have a nucleoid-like structure (19) were found in cells infected with vA32i.

FIG. 7.

Morphogenesis of mutant viruses. BS-C-1 cells were infected with vA32/A32i (A and C) or vA32i (B and D) in the absence of IPTG. After 24 h, the cells were fixed in glutaraldehyde and embedded in Epon, and then ultrathin sections were prepared for electron microscopy. Cr, crescents; Nu, nucleoids; IMV, intracellular mature virions; IV, immature virions; DIV, dense immature virions.

In addition to IV, there were numerous electron-dense, spherical or ovoid particles in cells infected with vA32i under nonpermissive conditions (Fig. 7D). We refer to these particles as dense, immature virions (DIV). The DIV appeared more compact than the IV (Fig. 7B and D) but lacked the brick shape and core structure of IMV, which were rare in cells infected with vA32i in the absence of IPTG. Remarkably, some DIV were wrapped with cisternal membranes in the cytoplasm and others appeared as extracellular enveloped particles (Fig. 7D). Occasional DIV were found in cells infected with vA32/A32i or wild-type virus (45), but the predominant particles in productively infected cells were IMV (Fig. 7C).

In summary, the electron microscopic studies suggested that repression of the A32 gene leads to a block in nucleoid formation and subsequent steps in morphogenesis of the core.

Infectivity, transcriptional activity, and morphology of purified particles.

Viral particles were purified, by sucrose density gradient centrifugation, from lysates of HeLa cells infected with WR or vA32i for 72 h in the absence of inducer. A cloudy band was visible at a similar position in each tube, but the WR band was more opaque. Protein determinations suggested that about five times more particles were recovered from cells infected with WR than from cells infected with vA32i. The infectivity of the purified particles, as determined by plaque assay in the presence of IPTG, was normalized to match the protein concentration. This analysis indicated that the particles purified from vA32i-infected cells had 6% of the infectivity of WR.

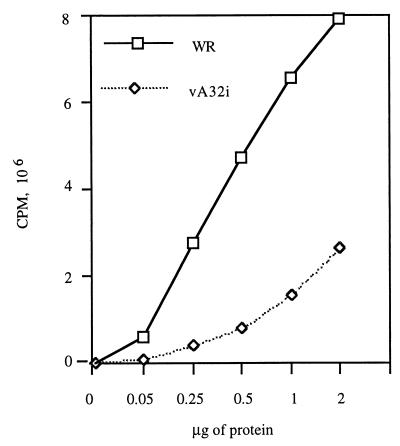

Infectious VV particles contain a complete transcriptional system that can be activated in vitro to transcribe the endogenous DNA genome (25, 38). The ability of the mutant virus particles to synthesize RNA in the absence of exogenous DNA was determined. The incorporation of [α-32P]UTP was measured as a function of protein concentration (Fig. 8). This analysis indicated that the particles from cells infected with vA32i in the absence of IPTG had 16% of the transcriptional activity of the WR particles.

FIG. 8.

Transcriptional activity of purified VV particles. Sucrose gradient-purified particles from HeLa cells infected with WR or vA32i in the absence of IPTG were adjusted to equal protein concentrations and used for in vitro transcription. The incorporation of [α-32P]UMP was measured. The same sucrose gradient-purified preparation was used for the experiments depicted in Fig. 8 through 12.

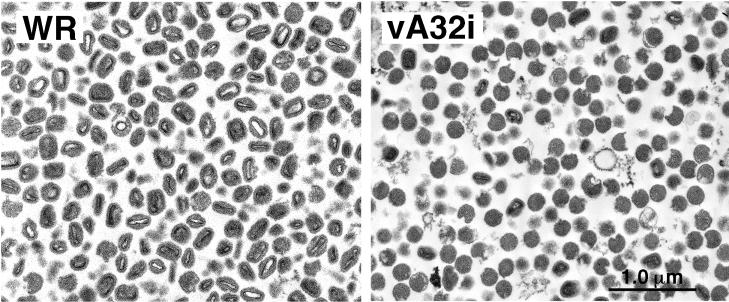

The purified virus particles were sedimented, and ultrathin sections of the pellets were examined by electron microscopy. The WR particles were typically brick-shaped IMV with dumbbell-shaped cores, whereas the vA32i particles were mostly round with no discernible core structures, resembling the DIV seen in infected cell sections (Fig. 9). Many of the DIV had an irregular, damaged appearance that was presumably due either to the purification procedure or to the preparation for electron microscopy. Approximately 12% of the vA32i particles had oval or brick shapes resembling IMV. The latter, which may account for both the infectivity and the transcriptional activity of the purified preparations of vA32i particles, were more numerous than expected from the previous cell sections, possibly because the infections were allowed to continue for an additional 48 h.

FIG. 9.

Electron microscopy of purified virus particles. Particles purified by sucrose gradient centrifugation from HeLa cells infected with WR or vA32i in the absence of IPTG were diluted, collected by high-speed centrifugation, fixed in glutaraldehyde, and embedded in Epon. Ultrathin sections were examined by electron microscopy.

Protein and DNA content of mutant virus particles.

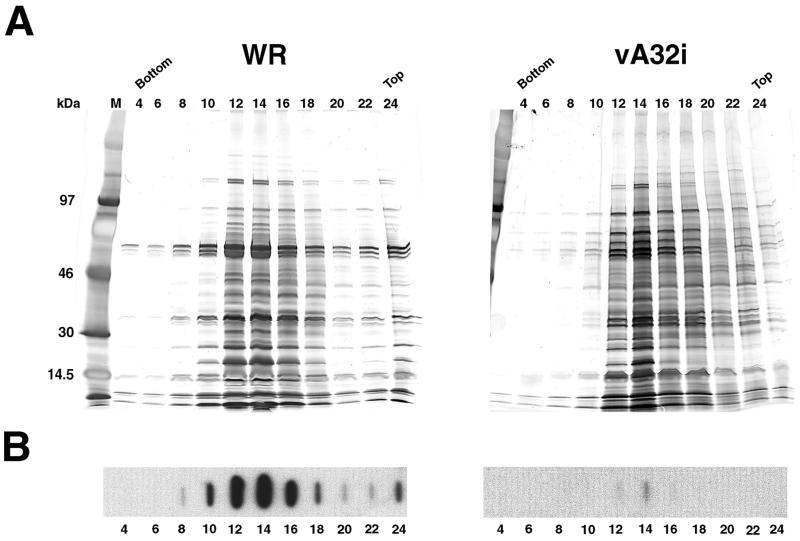

To determine the basis for the defects in infectivity and transcriptional activity, aliquots of the individual sucrose gradient fractions were analyzed for protein by SDS-PAGE. In this analysis, no adjustment was made for protein concentration. Silver-stained gels revealed the largest amounts of protein in fractions 12 to 16 (Fig. 10A), corresponding to the virus particles shown in Fig. 9. The overall protein pattern of the mutant virus particles, produced in the absence of IPTG, was similar to that of wild-type virus although several additional bands were present in the former. As will be shown, at least some of these bands represent uncleaved precursors of structural proteins.

FIG. 10.

Protein and DNA content of purified virus particles. Particles were purified from HeLa cells infected with WR or vA32i in the absence of IPTG. Aliquots of alternate numbered fractions of the sucrose gradients were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining (A) or by slot blot hybridization with a VV DNA probe (B). M, markers with masses shown on left. Bottom and Top refer to the sucrose gradient tube.

We then analyzed the sucrose gradient fractions for viral DNA by dot blot hybridization, again without correcting for protein concentration. The largest amount of viral DNA was present in fractions 12 to 16 of the gradient containing WR virus (Fig. 10B). Very little DNA was detected in the fractions from the gradient containing vA32i produced in the absence of IPTG (Fig. 10B). To correct for differences in the amount of viral particles, aliquots of fractions 12 to 16 of each gradient were pooled and adjusted to the same protein concentration. Serial dilutions of the pooled fractions were applied to a nylon membrane and hybridized to viral DNA. Quantification with a PhosphorImager indicated that the particle preparation from mutant virus contained approximately 18% of the viral DNA present in wild-type virus particles.

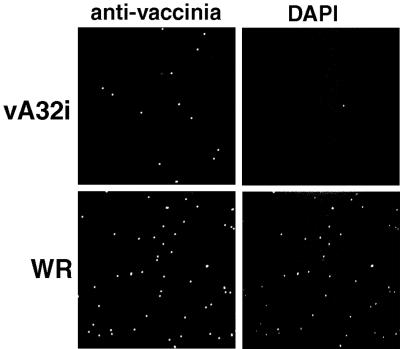

Determination of DNA in individual virus particles.

Laser scanning confocal microscopy was used to investigate the presence of DNA in individual virus particles purified by sucrose gradient centrifugation. Viral proteins were detected with an anti-VV polyclonal antibody, and DNA was stained with DAPI (Fig. 11). Most wild-type virions contained DNA, but DNA was present in only a minority of the mutant particles produced in the absence of IPTG. Quantification indicated that 2 to 3% of the wild-type virus particles failed to colocalize with the DNA stain, whereas 89% of the mutant particles lacked detectable DNA. The 11% of DNA-containing particles correlated with the 12% of brick-shaped particles determined by electron microscopy of the same preparation, suggesting that the DIV were devoid of DNA.

FIG. 11.

Laser scanning confocal microscopy of purified viral particles. Sucrose gradient-purified particles from HeLa cells infected with WR or vA32i in the absence of IPTG were mounted on fibronectin-coated coverslips and stained with DAPI and polyclonal antibody to VV.

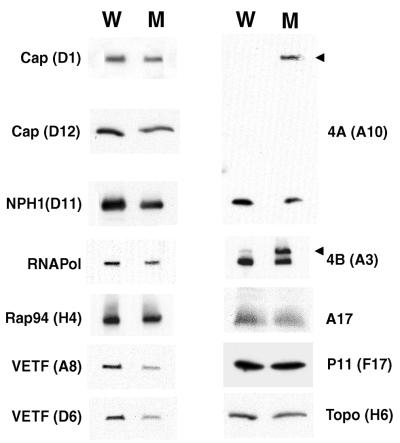

Analysis of specific proteins in mutant virus particles.

The protein components of the sucrose gradient-purified viral particles were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Since the vA32i particles produced in the absence of IPTG contained 12% IMV, we did not expect any proteins to be totally absent. Therefore, similar amounts of total protein from wild-type and mutant preparations were analyzed side by side for comparison. An autoradiographic collage of results obtained with 12 different antisera is shown in Fig. 12. The most dramatic difference was the presence of the precursors of 4A and 4B (represented by arrowheads) in mutant particles. To quantitate the relative amounts of the proteins, serial dilutions were made and the radioactivity in each band was measured with a PhosphorImager. The membrane protein-encoded by the A17 gene, the core protein encoded by the F17 gene, the large subunits of RNA polymerase, the RNA polymerase-associated protein RAP94 (ORF H4), and the topoisomerase were present in similar amounts in the preparations of wild-type and mutant particles. The two subunits of the capping enzyme encoded by D1 and D12 ORFs, the DNA-dependent ATPase (NPH1, ORF D11), and the two subunits of the early transcription factor encoded by the A8 and D6 ORFs were present in the preparation of mutant particles at 60 to 70% of the amount in wild-type virus particles.

FIG. 12.

Western blot analysis of purified viral particles. Purified viral particles from HeLa cells infected with WR or vA32i in the absence of IPTG were adjusted to similar protein concentrations and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore) and probed with antiserum to the indicated viral proteins followed by 125I-labeled protein A. W, wild-type virus particles; M, vA32i particles; arrowheads, uncleaved precursor proteins. Autoradiographs are shown.

DISCUSSION

The present study provides initial experimental data regarding the role of the VV A32 gene, which was predicted to encode a 34.4-kDa protein with a P-loop ATP binding motif. Our inability to delete the A32 gene suggested that it has an essential role for virus replication, even in tissue culture cells. Therefore, we constructed vA32i, a mutant with an inducible A32 gene, and demonstrated that it has a conditional lethal phenotype. The stringency of repression of A32 gene expression could be inferred from the inhibition of virus replication but not directly determined because the amount of A32 protein synthesized during infection with wild-type virus or vA32i in the absence of inducer was below the level of detection with antibody. The A32 gene product was readily detected as three closely spaced bands of approximately 30 kDa when cells were infected with vA32i in the presence of IPTG, a finding consistent with the 3- to 4-log induction achieved with this system (49). Detection problems also made it difficult to determine whether the A32 protein is associated with purified virions (data not shown). The development of more sensitive detection reagents is a priority of future research.

Metabolic labeling experiments were carried out to determine the stage at which vA32i replication was blocked under nonpermissive conditions. Viral protein synthesis appeared normal except that the precursor proteins P4A and P4B were inefficiently cleaved. Moreover, viral DNA was made and processed into unit-length genomes in the absence of inducer. Therefore, de novo synthesis of the A32 protein seems not to be required for viral macromolecular synthesis. These results, however, do not rule out a role for the A32 protein in viral early gene expression, since stocks of vA32i must be made in the presence of inducer and we do not know whether the A32 protein is a virion component.

Electron microscopic analysis of cells abortively infected with vA32i revealed the usual early stages in morphogenesis, with numerous crescents and IV. However, IV with nucleoids were rare compared to the numbers in cells productively infected with vA32/A32i. Previous studies have suggested that during infection with wild-type virus, the nucleoids enter IV just before the membrane is sealed (13, 19, 31, 34). Evidence that such nucleoids contain DNA has been obtained by using [3H]thymidine labeling (19) and immunoelectron microscopy (13). In the absence of IPTG, the low number of IV with nucleoids suggested that the A32 protein is needed for DNA packaging. Large cytoplasmic DNA crystalloids, similar to those present when VV assembly is blocked with rifampin (19, 39), were present in cells abortively infected with vA32i, indicating that the A32 protein is not needed for DNA condensation outside of virus particles.

Brick-shaped IMV with dumbbell-shaped cores were rare in cells infected with vA32i in the absence of IPTG, a finding consistent with their usual development from nucleoid-containing IV particles. Nevertheless, a further stage in IV maturation occurred: large numbers of compact, spherical, electron-dense particles called DIV were present in the cytoplasm of cells infected with vA32i under abortive conditions. Small numbers of particles with a similar appearance were previously noted during infections with wild-type VV (45) or other mutants (5, 10, 20). Evidently, the protein composition of the DIV membrane was relatively normal, since some were wrapped with cisternal membranes and enveloped forms were present on the cell surface. In this context, Sodeik et al. (45) reported that the p14 protein encoded by the A27L gene becomes viral membrane-associated at an intermediate stage between IV and IMV.

To further investigate the block in vA32i morphogenesis, the intracellular virus particles formed in the absence of inducer were purified by sucrose gradient centrifugation and then characterized. Electron microscopic images revealed that the majority of the purified particles were DIV. However, about 12% of the particles resembled IMV. The apparent leakiness may have occurred because the cells were harvested at 72 h after infection in order to obtain high particle yields. When normalized to the same protein concentration, the mutant particle preparations had 6% of the infectivity, 16% of the transcriptional activity, and 18% of the DNA content of the wild-type virus preparations. It seems likely that the IMV accounted for the infectivity and transcriptional activity and that the purified DIV lack DNA. We used confocal microscopy to confirm the latter interpretation. Of the purified virus particles from cells infected with wild-type virus, 97% contained DNA that stained intensely with DAPI, whereas only 11% of the mutant particles were stained. The latter number correlated well with the percentage of IMV determined by electron microscopy, suggesting that the DIV are devoid of DNA. The electron microscopic images suggested that many of the DIV were damaged. Although we do not know whether this occurred during purification or preparation for electron microscopy, it raised the possibility that DNA may have been released from the particles. However, since few nucleoids were seen in the sections of cytoplasmic IV, a packaging defect seems a more likely explanation for the absence of DNA.

It was of particular interest to determine the protein content of the DIV. The most striking feature of the mutant particles was the presence of precursors of the major core proteins 4A and 4B. The relative amounts of the precursor and mature cleaved forms were similar in the vA32i particles, whereas only trace amounts of the precursors were detected in wild-type virus particles. Proteolytic processing is, therefore, at least partially dependent on A32 expression. Relatively normal amounts of the 11K core protein were found even though it is a DNA binding protein thought to play a role in condensation of the DNA in the virion (23, 24). Similarly, the early transcription factor, VETF, binds stably to early promoters and it would seem likely that this association exists in virus particles. However, the A8 and D6 subunits of VETF were present in mutant particles at 60 to 70% of the amount found in wild-type viral particles. Similar values were obtained for the two subunits of capping enzyme and the DNA-dependent ATPase (NPH1). Even if corrected for the 12% contamination with IMV, there would still be more than half of the usual amount of these proteins, indicating that DNA is not absolutely needed for packaging or retention of VETF, capping enzyme, or NPH1 in virus particles. DNA does not seem to be required for the packaging of VV RNA polymerase, since the large subunits of that enzyme and the RNA polymerase-associated protein RAP94 were present in similar amounts in both wild-type and vA32i particle preparations. It is possible that the majority of internal proteins are present within the electron-dense material that is nonspecifically engulfed by the crescents. However, this cannot be the entire story since Zhang et al. (52) reported that RAP94 expression is needed for packaging the RNA polymerase as well as other enzymes including capping enzyme, topoisomerase and NPH1. Based on this finding, Zhang et al. (52) proposed the existence of a multicomponent enzyme complex that is incorporated into particles through RAP94 interactions with other proteins such as VETF. Further experiments indicated that VETF is required for morphogenesis (20), but an interaction with RAP94 remains to be shown. An attractive feature of the proposed model was that VETF is targeted through interactions with early promoter sequences within the genome. However, the present evidence for some VETF in DNA-deficient particles indicates that promoter binding cannot be the only mechanism by which the transcription factor is packaged. Though most core proteins appear to be packaged in the absence of nucleoid formation, analysis of additional viral proteins may reveal some for which virion association and DNA packaging are stringently related.

Conditional lethal mutations of several other VV genes have been shown to affect morphogenesis of the virus core. The one with the phenotype closest to vA32 is I7. The I7 ORF encodes a structural protein with some sequence similarity to the type II topoisomerase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (22). At nonpermissive temperatures, morphogenesis of an I7 ts mutant was interrupted at a stage between IV and IMV, with the accumulation of dense, spherical particles (9, 13, 22). The I7 mutant particles, however, contain nucleoids and DNA, indicating that morphogenesis was arrested at a slightly later stage than that which occurred with vA32i. The morphogenesis of the genetically unmapped J class of mutants described by Dales et al. (10) also appears to be similar to that of vA32i.

Virtually nothing is known regarding the mechanism of packaging VV DNA. Unlike the situation with bacteriophage lambda (8) and herpesviruses (29, 30, 54), the processing of VV DNA to unit-length genomes is not linked to particle formation since it occurs even when assembly is blocked with rifampin (33). As morphogenesis was interrupted at an even later stage when A32 expression was repressed, the finding of normal DNA processing was not surprising. The low frequency of IV with nucleoids and the absence of DNA in purified DIV suggest that the A32 protein is directly or indirectly involved in DNA packaging. One intriguing hypothesis, currently under investigation, is that the A32 protein interacts with putative packaging signals near the terminal regions of the VV genome and uses energy derived from ATP hydrolysis to translocate the DNA into viral particles. Such a mechanism was suggested by Koonin et al. (28) based on the presence of a conserved P-loop nucleoside triphosphate binding motif and additional sequence motifs shared with two other predicted viral ATPases: the gene I product of filamentous single-stranded DNA bacteriophages and the Iva2 gene product of adenoviruses. However, the roles for the phage and adenovirus proteins in DNA packaging have not been well established. Certain mutations of the phage protein, a component of the bacterial inner membrane, compensate for a defective DNA packaging signal, and there is an ATP requirement for assembly (14, 42). The adenovirus Iva2 protein has been detected in assembly intermediates but not in mature particles (40); recent studies indicate that it is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein involved in late-phase transcription (32). The A32 protein is not predicted to be a membrane protein, as is the phage gene I protein, nor is it an activator of late transcription, as is the adenovirus Iva2 protein. Therefore, there may be only limited functional analogies between these viral proteins.

In summary, the product of the A32 gene is required for VV morphogenesis and is directly or indirectly involved in DNA packaging. We are presently trying to develop methods to determine whether the A32 protein is virion associated and has ATPase and specific DNA binding activities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Carroll for advice regarding construction of recombinant viruses, T. Shors for pZippy-neo/gus, N. Cooper for cells, N. Dwyer for assistance with confocal microscopy, and E. Koonin for comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander W A, Moss B, Fuerst T R. Regulated expression of foreign genes in vaccinia virus under the control of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase and the Escherichia coli lac repressor. J Virol. 1992;66:2934–2942. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2934-2942.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baroudy B M, Venkatesan S, Moss B. Incompletely base-paired flip-flop terminal loops link the two DNA strands of the vaccinia virus genome into one uninterrupted polynucleotide chain. Cell. 1982;28:315–324. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baroudy B M, Venkatesan S, Moss B. Structure and replication of vaccinia virus telomeres. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1982;47:723–729. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1983.047.01.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broyles S S, Yuen L, Shuman S, Moss B. Purification of a factor required for transcription of vaccinia virus early genes. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:10754–10760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll M, Moss B. Host range and cytopathogenicity of the highly attenuated MVA strain of vaccinia virus: propagation and generation of recombinant viruses in a nonhuman mammalian cell line. Virology. 1997;238:198–211. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll M W, Moss B. E. coli β-glucuronidase (GUS) as a marker for recombinant vaccinia viruses. BioTechniques. 1995;19:352–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassetti M C, Moss B. Interaction of the 82-kDa subunit of the vaccinia virus early transcription factor heterodimer with the promoter core sequence directs downstream DNA binding of the 70-kDa subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7540–7545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catalano C E, Cue D, Feiss M. Virus DNA packaging: the strategy used by phage lambda. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:1075–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Condit R C, Motyczka A, Spizz G. Isolation, characterization, and physical mapping of temperature-sensitive mutants of vaccinia virus. Virology. 1983;128:429–443. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dales S, Milovanovitch V, Pogo B G T, Weintraub S B, Huima T, Wilton S, McFadden G. Biogenesis of vaccinia: isolation of conditional lethal mutants and electron microscopic characterization of their phenotypically expressed defects. Virology. 1978;84:403–428. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Earl P L, Cooper N, Moss B. Preparation of cell cultures and vaccinia virus stocks. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates & Wiley Interscience; 1991. pp. 16.16.1–16.16.7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Earl P L, Moss B. Generation of recombinant vaccinia viruses. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates & Wiley Interscience; 1991. pp. 16.17.1–16.17.16. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ericsson M, Cudmore S, Shuman S, Condit R C, Griffiths G, Locker J K. Characterization of ts16, a temperature-sensitive mutant of vaccinia virus. J Virol. 1995;69:7072–7086. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7072-7086.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng J-N, Russel M, Model P. A permeabilized system that assembles filamentous bacteriophage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4068–4073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuerst T R, Fernandez M P, Moss B. Transfer of the inducible lac repressor/operator system from Escherichia coli to a vaccinia virus expression vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2549–2553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garon C F, Barbosa E, Moss B. Visualization of an inverted terminal repetition in vaccinia virus DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:4863–4867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.4863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geshelin P, Berns K I. Characterization and localization of the naturally occurring cross-links in vaccinia virus DNA. J Mol Biol. 1974;88:785–796. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90399-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorbalenya A E, Koonin E V. Viral proteins containing the purine NTP-binding sequence pattern. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:8413–8440. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.21.8413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grimley P M, Rosenblum E N, Mims S J, Moss B. Interruption by rifampin of an early stage in vaccinia virus morphogenesis: accumulation of membranes which are precursors of virus envelopes. J Virol. 1970;6:519–533. doi: 10.1128/jvi.6.4.519-533.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu X, Carroll L J, Wolffe E J, Moss B. De novo synthesis of the early transcription factor 70-kDa subunit is required for morphogenesis of vaccinia virions. J Virol. 1996;70:7669–7677. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7669-7677.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson G P, Goebel S J, Paoletti E. An update on the vaccinia virus genome. Virology. 1993;196:381–401. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kane E M, Shuman S. Vaccinia virus morphogenesis is blocked by a temperature-sensitive mutation in the I7 gene that encodes a virion component. J Virol. 1993;67:2689–2698. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2689-2698.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kao S-Y, Ressner E, Kates J, Bauer W R. Purification and characterization of a superhelix binding protein from vaccinia virus. Virology. 1981;111:500–508. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90352-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kao S Y, Bauer W R. Biosynthesis and phosphorylation of vaccinia virus structural protein VP11. Virology. 1987;159:399–407. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90479-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kates J R, McAuslan B R. Poxvirus DNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;58:134–141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.1.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz E, Moss B. Formation of a vaccinia virus structural polypeptide from a higher molecular weight precursor: inhibition by rifampicin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1970;6:677–684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.66.3.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koonin E V, Senkevich T G. Vaccinia virus encodes four putative DNA and/or RNA helicases distantly related to each other. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:989–993. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-4-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koonin E V, Senkevich T G, Chernos V I. Gene A32 protein product of vaccinia virus may be an ATPase involved in viral DNA packaging as indicated by sequence comparisons with other putative viral ATPases. Virus Genes. 1993;7:89–94. doi: 10.1007/BF01702351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ladin B F, Blankenship M L, Ben-Porat T. Replication of herpesvirus DNA. V. Maturation of concatemeric DNA of pseudorabies virus to genome length is related to capsid formation. J Virol. 1980;33:1151–1164. doi: 10.1128/jvi.33.3.1151-1164.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ladin B F, Ihara S, Hampl H, Ben-Porat T. Pathway of assembly of herpesvirus capsids: an analysis using DNA+ temperature-sensitive mutants of pseudorabies virus. Virology. 1982;116:544–561. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leduc E H, Bernhard W. Electron microscopic study of mouse liver infected by ectromelia virus. J Ultrastruct Res. 1962;6:466–488. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(62)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lutz P, Kedinger C. Properties of the adenovirus IVa2 gene product, an effector of late-phase-dependent activation of the major late promoter. J Virol. 1996;70:1396–1405. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1396-1405.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merchlinsky M, Moss B. Resolution of vaccinia virus DNA concatemer junctions requires late gene expression. J Virol. 1989;63:1595–1603. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.4.1595-1603.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan C. The insertion of DNA into vaccinia virus. Science. 1976;193:591–592. doi: 10.1126/science.959819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan C, Ellison S A, Rose H M, Moore D H. Serial sections of vaccinia virus examined at one stage of development in the electron microscope. Exp Cell Res. 1955;9:572–578. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(55)90086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moss B. Poxviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 2637–2671. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moss B, Rosenblum E N. Protein cleavage and poxvirus morphogenesis: tryptic peptide analysis of core precursors accumulated by blocking assembly with rifampicin. J Mol Biol. 1973;81:267–269. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munyon W E, Paoletti E, Grace J T., Jr RNA polymerase activity in purified infectious vaccinia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;58:2280–2288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.6.2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagayama A, Pogo B G T, Dales S. Biogenesis of vaccinia: separation of early stages from maturation by means of rifampicin. Virology. 1970;40:1039–1051. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(70)90150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Persson H, Mathisen B, Philipson L, Pettersson U. A maturation protein in adenovirus morphogenesis. Virology. 1979;93:198–208. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(79)90287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez J F, Smith G L. IPTG-dependent vaccinia virus: identification of a virus protein enabling virion envelopment by Golgi membrane and egress. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5347–5351. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.18.5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russel M. Filamentous phage assembly. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1607–1613. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Senkevich T G, Bugert J J, Sisler J R, Koonin E V, Darai G, Moss B. Genome sequence of a human tumorigenic poxvirus: prediction of specific host response-evasion genes. Science. 1996;273:813–816. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Senkevich T G, Koonin E V, Bugert J J, Darai G, Moss B. The genome of molluscum contagiosum virus: analysis and comparison with other poxviruses. Virology. 1997;233:19–42. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sodeik B, Cudmore S, Ericsson M, Esteban M, Niles E G, Griffiths G. Assembly of vaccinia virus: incorporation of p14 and p32 into the membrane of the intracellular mature virus. J Virol. 1995;69:3560–3574. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3560-3574.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sodeik B, Doms R W, Ericsson M, Hiller G, Machamer C E, van’t Hof W, van Meer G, Moss B, Griffiths G. Assembly of vaccinia virus: role of the intermediate compartment between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi stacks. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:521–541. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.3.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson C L, Condit R C. Marker rescue mapping of vaccinia virus temperature-sensitive mutants using overlapping cosmid clones representing the entire virus genome. Virology. 1986;150:10–20. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vanderplasschen A, Smith G L. A novel virus binding assay using confocal microscopy: demonstration that intracellular and extracellular vaccinia virions bind to different cellular receptors. J Virol. 1997;71:4032–4041. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.4032-4041.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ward G A, Stover C K, Moss B, Fuerst T R. Stringent chemical and thermal regulation of recombinant gene expression by vaccinia virus vectors in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6773–6777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wittek R, Menna A, Muller K, Schumperli D, Bosley P G, Wyler R. Inverted terminal repeats in rabbit poxvirus and vaccinia virus DNA. J Virol. 1978;28:171–181. doi: 10.1128/jvi.28.1.171-181.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolffe E J, Moore D M, Peters P J, Moss B. Vaccinia virus A17L open reading frame encodes an essential component of nascent viral membranes that is required to initiate morphogenesis. J Virol. 1996;70:2797–2808. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2797-2808.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Y, Ahn B-Y, Moss B. Targeting of a multicomponent transcription apparatus into assembling vaccinia virus particles requires RAP94, an RNA polymerase-associated protein. J Virol. 1994;68:1360–1370. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1360-1370.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, Moss B. Inducer-dependent conditional-lethal mutant animal viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1511–1515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zimmermann J, Hammerschmidt W. Structure and role of the terminal repeats of Epstein-Barr virus in processing and packaging of virion DNA. J Virol. 1995;69:3147–3155. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.3147-3155.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]