Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the sensitivity to change of daily ratings of the comfort (COMF) and behavioral/emotional health (BEH) domains of the Infants with Clefts Observation Outcomes Instrument (iCOO) at three time points; and assess the association of post-surgical interventions on iCOO ratings.

Design:

The COMF and BEH domains were completed by Caregivers before (T0), immediately after (T1), and 2-months after (T2) cleft lip (CL) surgery. Analyses included descriptive statistics, correlations, t-tests, and generalized estimating equations.

Participants:

Caregivers (N=140) of infants with cleft lip with/without cleft palate.

Main Outcome Measures:

The COMF and BEH domain scores of the iCOO: Scale (SCALE), a summary of observable signs; and Global Impression (IMPR), a single item measuring caregivers’ overall impression.

Results:

Daily COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR scores changed significantly during T1 (p’s<.001) but not T0 or T2. Day 1 and 7 T0 scores were significantly higher than Day 1 and 7 T1 scores (p’s <.001 to <.012) but similar at T2 (p’s>0.05). After CL surgery, combined use of immobilizers and nasal stents; and use of multiple feeding methods with treatment for gastroesophageal reflux were associated with lower daily scores in COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR (p’s .040-<.001).

Conclusions:

COMF and BEH iCOO scores were sensitive to daily changes in infant well-being following CL surgery. Future studies should further investigate impact of post-surgical treatments on infant well-being.

Keywords: cleft, infant well-being, iCOO, Observer-Reported Outcome, Patient Reported Outcomes

Caregiver Observations and Impressions of Infant Well-Being

Infant well-being is critical to healthy development because it builds emotional expression and regulation, nurtures the infant-caregiver relationship, and creates a foundation for the exploration and understanding of the family, community and cultural norms.1 Almost from birth, infants are able to express their emotional and behavioral well-being through facial expressions, motor movements, and vocalizations.2 An infant’s facial expressions are the means by which they signal social intentions and provide information about their current state. Caregivers' observations and consideration of the infant's expressions are essential to the infant’s evolving emotional and social functioning.3 Caregivers are acutely attuned to their infant’s emotional expressions and behaviors and therefore are best qualified to observe and interpret these behavioral cues to make judgments about their infant’s well-being4,2 and physical needs (e.g., sleep, food, diaper change).

Cleft Lip and Palate

Cleft lip with or without palate (CL±P) is one of the most common birth conditions in the United States, estimated as one in approximately 970-1,029 live births.5 Cleft care is ongoing from infancy to young adulthood and requires an interdisciplinary team approach and multiple interventions for physical functioning as well as associated psychosocial aspects and quality of life.6 Having a CL±P impacts a number of physical areas of functioning in infancy, including breathing, vocalization, hearing, sleeping, and feeding.7 Surgical repair of cleft lip (CL) generally occurs when the infant is 3 to 6 months of age. Other treatments for CL±P during the first year can include pre-surgical molding to bring lip segments in closer alignment using a nasoalveolar molding appliance (NAM) or taping, pressure equalization tubes to treat chronic middle ear fluid, and surgical repair of the cleft palate (CP).6 The primary goal of CL surgery is to restore the anatomical shape of the lip and nose, allowing for normal movements for eating, speaking, and smiling. In order to achieve optimal outcomes, clinicians have developed surgical protocols that include a variety of post-surgical treatments including use of nasal stents to maintain nose shape after surgery, arm/hand immobilizers to prevent infant from reopening lip stitches, and post-surgical feeding methods that decrease pressure on the lip. However, the treatment to improve one area of function (e.g., nasal stents to shape the nose) may adversely impact another aspect of health (e.g., comfort).7 Therefore, development of an instrument to obtain objective information on how interventions such as surgery or post-surgical treatments affect infants’ comfort or psychological well-being is warranted.

Observer Reported Outcomes (ObsROs) for Infant with CL±P

Due to their age, infants are not able to report their own experiences and perceptions so measurement of clinical outcomes must rely on other reporters. Most caregivers of infants with CL±P develop strong emotional connections with their infants and are able to interpret their infant’s emotional and behavioral expressions, despite the presence of unique stressors that can impact caregiver-infant interactions when the child has CL±P.8 Caregivers are therefore best qualified to observe and interpret these behavioral cues to make judgments about their infant’s well-being.4,2 The literature supports the use of daily observational diaries to obtain observer reported outcomes (ObsROs).9,10 ObsROs are considered best practice to provide information about the impact of a medical condition or procedure when patient-reported outcomes are not feasible as in the case of infants.11

Most ObsROs that focus on infants assess pain reactions.12,13,14 Disease specific ObsROs for infants are less common; however, the few studies that exist have found that caregivers were able to reliably report symptoms of their child with various medical conditions, including respiratory syncytial virus9 and cystic fibrosis.15 Most other outcomes studies that examined the impact of various medical conditions on emotional or behavioral outcomes focused on older children, not infants (e.g., Uhl et al.16, Feragen et al.17) To our knowledge, no studies have examined infant well-being from the perspective of the infant’s caregiver and we were unable to identify any existing instrument that met criteria of an ObsRO that could be used to assess infant comfort (beyond pain) or infant emotional and behavioral responses to medical interventions. This type of ObsRO could be useful to improve clinical care of children with CLP.

Aims and Objectives

The present project examined the sensitivity to change of daily caregiver ObsRO reports of comfort and psychological well-being of infants before CL surgery (T0), within the first week after CL surgery (T1) and 2-months after CL surgery (T2).

The first aim was to establish the reliability of the daily ObsRO reports of infant comfort and psychological well-being. We hypothesized that daily reports would be consistent at T0 and T2 when no medical interventions were present. We anticipated variability in reports at T1, the week after lip surgery.

The second aim examined the relationship of scores reported at T0 to scores reported at T1 and T2. To determine the sensitivity of the ObsRO to medical interventions, it was hypothesized that T1 scores would initially be lower than T0 scores but would increase to T0 levels by the end of the seven-day reporting period. T2 scores were expected to be similar to or higher than T0 scores.

The third aim was to assess the association between postoperative interventions and daily ObsRO ratings of infant comfort and psychological well-being at T1. We hypothesized that post-surgical interventions, such as use of multiple feeding methods, treatment for airway issues, or use of nasal stents would be associated with ObsRO reports of decreased comfort and psychological well-being while choice of pain medication would be associated with increased comfort and psychological well-being.

Materials and Methods

All study procedures were approved by each site’s local Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Caregivers of infants with CL±P were recruited from 3 cleft/craniofacial centers and from advertisements posted to cleft-related advocacy online support groups. Caregivers were eligible if they: (1) were at least 18 years of age (2) were fluent in either English or Spanish, and (3) had an infant who was less than 18 months of age with an unrepaired cleft lip that was not associated with other major medical conditions (e.g., cardiac problems, major malformations) and the primary lip surgery was scheduled within a year of enrollment.

Procedures

Primary caregivers were instructed to complete the daily iCOO instrument at three time points: seven consecutive days beginning 2 to 3 weeks prior to CL surgery (T0), seven consecutive days beginning the second day post CL surgery (T1), and for three consecutive days beginning approximately two months post CL surgery (T2). Day 2 after surgery was chosen as the start point for the immediate post-surgery administration to allow most patients to be discharged from the hospital and in their home environment. Data collection instruments were available in English and Spanish (Mexican) and had to be completed within the 24-hour period of the specified day or data from that day was not included in the analysis. Most caregivers completed the iCOO online (79%) and there were no significant differences in mean scores on the COMF or BEH items between online and paper formats.18 Caregivers could opt to receive daily text reminders for online administration. On the last day of T1 data collection, caregivers were also asked to complete an optional questionnaire about the treatments their child had received during the previous 7 days. All data were entered into REDCap19 either directly by online participants or, for paper versions, by study staff. Caregiver participants received $5 for each day of iCOO completion and received an additional $25 bonus if they completed the iCOO for all days for the time point, for a potential total of $160.

Measures

Infant with Clefts Observation Outcomes Instrument (iCOO).

The iCOO is a caregiver report of child (ages 0-3 years) health and well-being related to areas likely to be impacted by the presence of cleft lip, cleft palate, or both and ensuing treatment interventions. The iCOO was assessed for readability and has a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of 4.6. Development of the iCOO followed a strict methodology for ObsRO development.11 Further details about development are available in Heike et al.20 Two of 9 domains, COMF (5 items) and BEH (7 items), were examined in this study. Through observable signs and behaviors, the COMF domain assesses child discontent and/or distress while the BEH domain measures the infant’s psychological health including mood, self-regulation, and interactions with caregivers and others. Each domain yields two scores: a scale (SCALE) and an impression (IMPR) score. The SCALE score is the mean of item responses based on observable signs that focused on frequency [e.g., “In the last 24 hours did you observe: Your child being easy to soothe (for example, stopped crying quickly when you picked them up?”): 0 (None of the time), 1 (Some of the Time), or 2 (All of the Time)] (See Supplemental Table 1 for a list of individual SCALE items and mean item scores by observation period). The IMPR score is a single item that asks caregivers, “overall how would you rate your child’s comfort (behavior) during the past 24 hours?” The IMPR items have a 5-point response scale: (5) excellent (4) very good (3) good (2) fair (1) poor. SCALE and IMPR scores were scaled from 0-100 to facilitate comparison. T0 test-retest ICC reliabilities were .79 and .78 respectively for the COMF and BEH SCALE scores and .82 and .76 for the COMF and BEH IMPR. Correlations between the COMF SCALE and IMPR and BEH SCALE and IMPR were each 0.65. Cronbach Alphas internal consistency were and .67 and .76 for the COMF and BEF SCALES. Construct validity was established by demonstrating that the iCOO COMF and BEH mean SCALE and IMPR scores responded to change following lip surgery (effect sizes were large and ranged from d = −.83 to −1.29).18

Cleft-Related Treatment Questionnaire.

Caregivers were also asked to complete an optional questionnaire to document the types of treatments infants received during seven days of diary completion at T1. For this paper we were interested in whether an infant received treatments in any of the following categories: 1) airway treatments, 2) interventions directly related to protecting the surgical site (i.e., immobilizers to prevent infant from touching surgically repaired lip and nasal stents to help maintain nasal shape), 3) number of feeding methods used during immediate post-surgery week, 4) treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and 5) pain medication usage. Responses were coded yes/no for airway and GERD treatments, nasal stents, and immobilizers to indicate: 0 (treatment was not received), 1 (treatment was received). Feeding treatments were coded: 1, 2, or 3 to indicate the number of different feeding methods used during the week following surgery. Post-surgical medication use was coded as: 0 (No reported medications) 1 [Over the Counter (OTC, e.g., Tylenol, Ibuprofen), and Opioids], and 2 (OTC only).

Treatments with aim of directly improving aesthetic results such immobilizers and nasal stents may have a cumulative effect on outcomes. To assess this possibility, we created a combined variable: 1) no use of immobilization or nasal stents; 2) use of immobilization only; 3) use of nasal stents only; and 4) use of both immobilization and nasal stents. Typically, a recommendation to change the feeding method immediately post-surgery to a cup or syringe is made to prevent lip dehiscence. Therefore, we were interested in knowing if this change in feeding method had a deleterious effect on infant comfort and well-being when infants were also being treated for GERD. The combined feeding/GERD variable was labeled: one feeding method, no GERD treatment (1 Method, No GERD); one feeding method with GERD treatment (1 Method + GERD); two or three feeding methods with no GERD (2-3 Methods, No GERD); and two or three feeding methods with GERD (2-3 Methods + GERD).

Socio-Economic Status (SES). SES was measured as household income and highest education of reporting caregiver.

Analysis Plan

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percent) were generated for demographic, COMF, and BEH variables and treatment predictor variables. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to assess: 1) the association of participant location (site and region), SES, caregiver and infant characteristics with COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR Scores at baseline (T0); 2) daily changes in COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR scores at T0, T1, and T2; and 3) the association of post-surgical interventions on daily changes in COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR scores at T1. GEE analyses were chosen because they allow for parameter estimation while accounting for the correlated daily outcome data.21

We planned to retain any significant SES, caregiver, or child variables in subsequent GEE analyses. It was determined a priori that day post-surgery and child age would be used as covariates for the treatment analyses. Post-surgery interventions included airway treatment, interventions to increase likelihood of surgical success including use of arm/hand immobilization devices to minimize contact with healing lip and nasal stents to help hold nasal shape, number of feeding methods used during the seven reporting days; treatment for GERD; and type of pain medication used. We also conducted secondary GEE analyses to assess the differential association of the combined variables of number of feeding methods and GERD and use of nasal stents and immobilizers with T1 COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR scores.

To document differences among scores at T0, T1, and T2, paired t-tests were used to examine mean differences (MD) between T0 and T1 COMF and BEH IMPR and SCALE scores on Day 1 and Day 7 and MD between COMF and BEH IMPR and SCALE scores T0 and T2 scores on Day 1. We used Days 1 and 7 to compare T0 and T1 COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR scores to capture changes from the beginning and end of the T1 period while avoiding multiple t-tests. We used only Day 1 as a comparison between T0 and T2 because caregivers completed only 3 days at T2 and daily scores did not differ significantly across T0 or T2. For t-tests, effect sizes using Cohen’s d were interpreted as: small, 0.20; medium, 0.50; large, ≥ 0.80.22

All analyses were completed with SPSS Version 28.0 (IBM).

Results

Primary caregivers of 140 participants completed at least one day of the iCOO across the three reporting periods (95% of caregivers completing at least three days of T0 observations): There were 856 separate observations at T0, 755 at T1, and 318 at T2 (there were fewer observations at T2 because diaries were completed across 3 rather than 7 days), for a total of 1929 observations. Most caregivers were female (96%), married/partnered (89%), white (79%) and not Hispanic/Latinx (88%) and the primary or an equal caregiver for the infant (99%). Eighty percent of caregivers had completed at least some college and the caregiver’s income was evenly distributed among the categories. Most infants were male (67%), had a cleft of the lip and palate (73%); and had a unilateral (71%) (versus bilateral) cleft lip. The mean age of the infants at the T0 iCOO completion was 5.12 months (range from 1.12 to 11.67). Sixty-three percent of the caregivers were recruited directly from one of the 3 participating sites; the remaining 37% of participants were cared for by cleft teams from 29 different states in the US (Table 1). Socioeconomic status, caregiver and child characteristics were not significantly associated with T0 COMF or BEH SCALE or IMPR scores.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| CAREGIVER CHARACTERISTICS | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Respondent | ||

| Female | 135 | 96 |

| Male | 5 | 4 |

| Relationship to Child | ||

| Primary or Sole Caregiver | 99 | 71 |

| Equal Caregiver | 40 | 28 |

| Secondary Caregiver | 1 | 1 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married/Partnered | 124 | 89 |

| Single/Divorced/Separated | 15 | 11 |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 |

| Education | ||

| HS/GED or less | 28 | 20 |

| Some College | 41 | 29 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 47 | 34 |

| Graduate/Professional | 21 | 15 |

| Unknown | 3 | 2 |

| Household Income | ||

| <$35,000 | 33 | 24 |

| $35,000-$74,999 | 37 | 26 |

| $75,000-$114,999 | 34 | 24 |

| >=$115,000 | 27 | 19 |

| Unknown | 9 | 6 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | ||

| Yes | 17 | 12 |

| No | 123 | 88 |

| Race | ||

| White | 110 | 79 |

| Black/African American | 3 | 2 |

| Asian | 7 | 5 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 7 | 5 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 1 |

| Multiracial | 8 | 6 |

| Other Race | 2 | 1 |

| Unknown | 2 | 1 |

| CHILD CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 94 | 67 |

| Female | 46 | 33 |

| Cleft Diagnosis | ||

| Cleft lip only | 38 | 27 |

| Cleft lip and palate | 102 | 73 |

| Cleft Lip Type | ||

| Bilateral | 40 | 29 |

| Unilateral | 100 | 71 |

| Recruitment Sites | ||

| Northwest Clinic | 61 | 44 |

| Midwest Clinics | 27 | 19 |

| Online | 41 | 37 |

| Age in Months at Baseline | Mean | SD |

| Male | 5.34 | 2.0 |

| Female | 4.68 | 1.8 |

Daily Changes in COMF and BEH Outcomes Across Time Periods

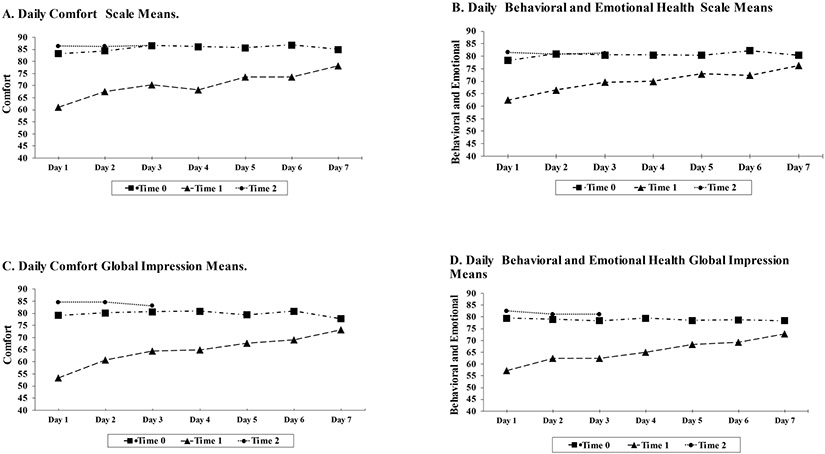

Figure 1 demonstrates the trajectory of COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR scores at each measurement point. There were no significant differences in COMF or BEH SCALE or IMPR scores by day at T0 or T2 (p’s ranged from .121 to .980) based on GEE analysis. There was a significant change in scores by day for COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR at T1 (all p’s <.001).

Figure 1.

Comparison of Comfort (COMF) and Behavioral and Emotional Health (BEH) Scale and Global Impression daily mean scores across observation periods.

Note: All scores were scaled 0-100 such that higher scores represent better functioning. Diaries were completed for 7 days at T1 and T2 and 3 days at T3. Data at T0 was based on 856 observations from 140 caregivers; at T1 data was based on 755 observations from 122 caregivers; and at T2 data was based on 318 observations from 119 caregivers. Rates of daily changes were not significant for any of the COMF or BEH variables at T0 or T2 (all p’s > .491). At T1 daily changes were significant for each COMF and BEH outcome (all p’s < .001).

Comparison of T0 to T1 and T2 COMF and BEH Outcomes

Correlations between T0 and T1 COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR scores were low and ranged from .05 to .32 on Day 1 and ranged from .23 to .55 on Day 7. Mean differences for the COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR scores between T0 and T1 on Day 1 ranged from 16.81 to 27.77 [all p’s <.001, with large effect sizes (d’s ranged from .82 to 1.28)]; Mean differences on Day 7 ranged from 5.1 to 7.6 [p’s from .012 to <.001 with small effect sizes (d’s ranged from .27 to .40)]. Correlations on Day 1 between T0 and T2 COMF and BEH Scale and IMPR scores ranged from .27 to .40. Mean differences between T0 and T2 for COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR scores ranged from −.99 to −3.4 [p’s > .05 with small effect sizes (d’s ranged from −.05 to −.18)] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Paired T-Tests Examining BEH and COMF Scores by Time

| T0 - T1 | N | R | Mean Difference |

Standard Error |

CI | t | df | P | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | ||||||||||

| COMF SCALE | 103 | .32*** | 22.788 | 2.101 | 18.621 | 26.956 | 10.846 | 103 | <.001 | 1.064 |

| BEH SCALE | 102 | .25** | 16.807 | 2.027 | 12.787 | 20.827 | 8.293 | 101 | <.001 | .821 |

| COMF IMPR | 103 | .32*** | 27.767 | 2.142 | 23.519 | 32.015 | 12.965 | 102 | <.001 | 1.278 |

| BEH IMPR | 102 | .05 | 24.118 | 2.403 | 19.351 | 28.884 | 10.038 | 101 | <.001 | .994 |

| Day 7 | ||||||||||

| COMF SCALE | 98 | .42*** | 7.551 | 1.930 | 3.720 | 11.382 | 3.912 | 97 | <.001 | .395 |

| BEH SCALE | 97 | .55*** | 5.081 | 1.632 | 1.842 | 8.320 | 3.114 | 96 | .001 | .316 |

| COMF IMPR | 98 | .37*** | 5.510 | 2.147 | 1.249 | 9.772 | 2.566 | 97 | .012 | .259 |

| BEH IMPR | 98 | .23* | 6.122 | 2.255 | 1.647 | 10.597 | 2.715 | 97 | .008 | .274 |

| T0 - T2 | ||||||||||

| Day 1 | ||||||||||

| COMF SCALE | 102 | .27** | −1.961 | 1.890 | −5.710 | 1.789 | −1.037 | 101 | .302 | −.103 |

| BEH SCALE | 101 | .40*** | −2.122 | 1.698 | −5.491 | 1.24812 | −1.249 | 100 | .215 | −.124 |

| COMF IMPR | 102 | .32*** | −3.725 | 2.024 | −7.740 | .289 | −1.841 | 101 | .069 | −.182 |

| BEH IMPR | 101 | .39*** | −.990 | 1.875 | −4.710 | 2.729 | −.528 | 100 | .599 | −.053 |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Note: COMF = Comfort, BEH = Behavioral and Emotional Health, IMPR = Global Impression Score, T0 = Baseline, T1 = Immediate post-surgery, T2= 2-months post-surgery.

Association Between Post-Surgical Interventions on Time 1 COMF and BEH Score

Ninety-four participants completed a portion of the cleft-related treatments questionnaire. The primary analyses included 498 daily diaries from 76 participants during the seven reporting days of T1. Based on these diaries, 42% received an airway treatment, 58% were using immobilizers, 49% used nasal stents, 26% of the infants used more than one feeding method, and 32% were being treated for GERD. Caregivers indicated that 56% of infants received both opioids and OTC medication during the post-operative week and 6% of infants received no medication during the reporting period.

GEE analyses of the associations of post-surgical interventions with caregiver reports of infant COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR scores are found in Table 3. With the exception of a trend for immobilizer use, which was associated with daily changes in COMF SCALE scores (p = .052), post-surgical interventions were not significantly associated with daily changes in COMF and BEH SCALE scores (all p’s > .05). Use of an immobilizer, nasal stents, and more than one feeding method (Feed) in the week after surgery were each associated with lower daily COMF IMPR scores (p’s ranged from .021 to .026). Treatment for GERD and use of an immobilizer were associated with poorer daily BEH IMPR scores (p’s = .032 and .007) and we observed a similar trend for use of nasal stents (p = .063). Time after surgery was a significant covariate in the effects of these interventions for all COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR scores (p’s <.001). With few exceptions, when the intervention was present, caregivers reported lower scores across the reporting period for each of the outcome variables. Daily changes when intervention was present were typically parallel to, but lower than, when the intervention was not present.

Table 3.

Results of Generalized Estimating Equations Assessing Association of Immediate Post-Surgical Treatments on Daily Scale and Global Impression Reports.

| Outcome | Variables | Beta | Standard Error |

Confidence Intervals |

Wald Chi- Square |

df |

P Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort Scale | Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Days After Surgery | 2.516 | .3302 | 1.868 | 3.163 | 58.043 | 1 | <.001 | |

| Child Age | −.388 | 1.1804 | −2.701 | 1.926 | .108 | 1 | .743 | |

| Feeding Methods | 3.532 | 2 | .171 | |||||

| 1 Method | 9.772 | 5.3049 | −.625 | 20.170 | 3.393 | 1 | .065 | |

| 2 Methods | 6.704 | 6.1705 | −5.390 | 18.798 | 1.181 | 1 | .277 | |

| 3 Methods (REF) | 2.793 | 2 | .248 | |||||

| GERD Treatment | 2.889 | 4.0154 | −4.981 | 10.759 | .518 | 1 | .472 | |

| Airway Treatment | 5.850 | 4.2631 | −2.506 | 14.205 | 1.883 | 1 | .170 | |

| Immobilizer Use | 8.787 | 4.5272 | −.086 | 17.660 | 3.767 | 1 | .052 | |

| Nasal Stents | 5.332 | 4.2221 | −2.943 | 13.607 | 1.595 | 1 | .207 | |

| Medication Use | .398 | 2 | .820 | |||||

| None Reported | −4.378 | 11.5879 | −27.090 | 18.333 | .143 | 1 | .706 | |

| Opioid ± OTC | −2.583 | 4.3266 | −11.063 | 5.897 | .356 | 1 | .551 | |

| OTC (Ref.) | ||||||||

| Behavioral and Emotional Health Scale | Days After Surgery | 2.240 | .3378 | 1.578 | 2.902 | 43.949 | 1 | <.001 |

| Child Age | .841 | .9905 | −1.101 | 2.782 | .720 | 1 | .396 | |

| Feeding Methods | 2.396 | 2 | .302 | |||||

| 1 Method | 7.928 | 5.7388 | −3.320 | 19.176 | 1.909 | 1 | .167 | |

| 2 Methods | 4.415 | 6.0324 | −7.408 | 16.239 | .536 | 1 | .464 | |

| 3 Methods (REF) | ||||||||

| GERD Treatment | 4.415 | 6.0324 | −7.408 | 16.239 | .536 | 1 | .464 | |

| Airway Treatment | 4.741 | 3.9517 | −3.004 | 12.487 | 1.440 | 1 | .230 | |

| Immobilizer Use | 4.630 | 3.9241 | −3.062 | 12.321 | 1.392 | 1 | .238 | |

| Nasal Stents | 2.148 | 3.7594 | −5.220 | 9.517 | .327 | 1 | .568 | |

| Medication Use | 1.576 | 2 | .455 | |||||

| None Reported | −2.252 | 9.8273 | −21.514 | 17.009 | .053 | 1 | .819 | |

| Opioid ± OTC | −4.575 | 3.6748 | −11.777 | 2.628 | 1.550 | 1 | .213 | |

| OTC (Ref.) | ||||||||

| Comfort Global Impressions | Days After Surgery | 3.024 | .3957 | 2.248 | 3.800 | 58.391 | 1 | <.001 |

| Child Age | −.239 | .9202 | −2.043 | 1.564 | .068 | 1 | .795 | |

| Feeding Methods | 7.338 | 2 | .026 | |||||

| 1 Method | 11.794 | 4.5967 | 2.785 | 20.804 | 6.583 | 1 | .010 | |

| 2 Methods | 6.024 | 5.0815 | −3.935 | 15.984 | 1.406 | 1 | .236 | |

| 3 Methods (REF) | ||||||||

| GERD Treatment | 5.060 | 3.2796 | −1.368 | 11.488 | 2.380 | 1 | .123 | |

| Airway Treatment | 2.840 | 3.1239 | −3.283 | 8.963 | .827 | 1 | .363 | |

| Immobilizer Use | 7.924 | 3.4648 | 1.133 | 14.715 | 5.230 | 1 | .022 | |

| Nasal Stents | 7.583 | 3.2815 | 1.151 | 14.014 | 5.339 | 1 | .021 | |

| Medication Use | 1.816 | 2 | .403 | |||||

| None Reported | −1.239 | 6.1614 | −13.315 | 10.837 | .040 | 1 | .841 | |

| Opioid ± OTC | −4.647 | 3.4950 | −11.497 | 2.203 | 1.768 | 1 | .184 | |

| OTC (Ref.) | ||||||||

| Behavioral and Emotional Global Impressions | Days After Surgery | 2.691 | .3976 | 1.912 | 3.470 | 45.825 | 1 | <.001 |

| Child Age | −.065 | .8818 | −1.794 | 1.663 | .005 | 1 | .941 | |

| Feeding Methods | 2.420 | 2 | .298 | |||||

| 1 Method | 4.347 | 3.4260 | −2.367 | 11.062 | 1.610 | 1 | .204 | |

| 2 Methods | −.212 | 4.3218 | −8.683 | 8.258 | .002 | 1 | .961 | |

| 3 Methods (REF) | ||||||||

| GERD Treatment | 6.507 | 3.0375 | .553 | 12.460 | 4.589 | 1 | .032 | |

| Airway Treatment | 3.900 | 3.0429 | −2.064 | 9.864 | 1.643 | 1 | .200 | |

| Immobilizer Use | 8.428 | 3.1297 | 2.294 | 14.562 | 7.251 | 1 | .007 | |

| Nasal Stents | 5.357 | 2.8787 | −.285 | 10.999 | 3.463 | 1 | .063 | |

| Medication Use | 2.253 | 2 | .324 | |||||

| None Reported | −1.201 | 5.8742 | −12.715 | 10.312 | .042 | 1 | .838 | |

| Opioid ± OTC | −5.030 | 3.4157 | −11.725 | 1.664 | 2.169 | 1 | .141 | |

| OTC (Ref.) | ||||||||

Note: Results based on 498 observations across seven days from 76 subjects with a minimum of three measurements per subject. GI = Global Impressions. BEH = Behavioral and emotional health. GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease. REF. = Reference Group. OTC = Over the Counter (e.g., Tylenol, Ibuprofen).

The four interventions that were associated with one or more of the COMF and BEH variables included: number of feeding methods, treatment for GERD, use of immobilizers, and use of nasal stents. Combining reports on feeding methods and GERD (Feed/GERD), 53% were in the 1 Method, no GERD group; 21% in the 1 Method & GERD group; 15% in the 2-3 Methods, No GERD group; and 11% in the 2-3 Methods & GERD group. Combining reports on immobilizers and nasal stents (Immob/Stents), 15% stated that the infant used neither immobilizers nor nasal stents; 35% used only immobilizers; 29% used only nasal stents; and 21% used both immobilizers and nasal stents.

The secondary GEE analysis investigating the association of Feed/GERD and Immob/Stents was completed based on 545 reports from 84 caregivers with results presented in Table 4. Feed/GERD was significantly associated with daily changes in all COMF and BEH outcome variables (all p’s <.001) and Immob/Stents was significantly associated with daily changes in COMF and BEH IMPs (p’s = .014 and .049) with a trend for COMF SCALE (p = .098). As illustrated in Figure 2 A-D, infants in the 2-3 Methods & GERD group did more poorly than children in the other three groups on each of the four scales across the seven reporting days and in each case the differences were significant (BETA’s = 8.02 to 16.38, p’s = .04 to < .001). Infants in the 1 Method, No GERD group generally had the highest outcomes across the 7 days, though all four groups showed improvement.

Table 4.

Results of Generalized Estimating Equations assessing the Association of the Combined Interventions Related to Feeding and Interventions to Support Surgical Outcomes.

| Outcome | Variables | Beta | Standard Error |

Confidence Intervals |

Wald Chi- Square |

df |

P Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort Scale | Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Days After Surgery | 2.475 | .3203 | 1.847 | 3.103 | 59.684 | 1 | <.001 | |

| Child Age | −.692 | 1.1393 | −2.925 | 1.541 | .369 | 1 | .543 | |

| Feeding Methods ± GERD Treatment | 44.036 | 3 | <.001 | |||||

| One Method, No GERD | 16.197 | 3.3072 | 9.715 | 22.679 | 23.984 | 1 | <.001 | |

| One Method with GERD | 18.032 | 3.7559 | 10.670 | 25.393 | 23.049 | 1 | <.001 | |

| Two or Three Methods, no GERD | 18.993 | 4.2365 | 10.690 | 27.296 | 20.099 | 1 | <.001 | |

| Two or Three Methods with GERD (REF) | ||||||||

| Immobilizers ± Nasal Stents | 6.294 | 3 | .098 | |||||

| No Immobilizers or Nasal Stents | 16.227 | 6.6545 | 3.184 | 29.270 | 5.946 | 1 | .015 | |

| Immobilizers only | 5.249 | 4.8602 | −4.276 | 14.775 | 1.167 | 1 | .280 | |

| Nasal Stents only | 5.488 | 4.9705 | −4.254 | 15.230 | 1.219 | 1 | .270 | |

| Immobilizers and Stents | ||||||||

| Behavioral and Emotional Health Scale | Days After Surgery | 2.136 | .3193 | 1.511 | 2.762 | 44.774 | 1 | <.001 |

| Child Age | .007 | .9072 | −1.771 | 1.786 | .000 | 1 | .993 | |

| Feeding Methods ± GERD Treatment | 34.053 | 3 | <.001 | |||||

| One Method, No GERD | 13.971 | 3.0759 | 7.943 | 20.000 | 20.632 | 1 | <.001 | |

| One Method with GERD | 15.728 | 3.6150 | 8.642 | 22.813 | 18.928 | 1 | <.001 | |

| Two or Three Methods, no GERD | 16.382 | 3.7584 | 9.016 | 23.749 | 19.000 | 1 | <.001 | |

| Two or Three Methods with GERD (REF) | ||||||||

| Immobilizers/Nasal Stents | 2.032 | 3 | .566 | |||||

| No Immobilizers or Nasal Stents | 7.880 | 6.2680 | −4.405 | 20.165 | 1.580 | 1 | .209 | |

| Immobilizers only | 1.894 | 4.0177 | −5.980 | 9.769 | .222 | 1 | .637 | |

| Nasal Stents only | 4.527 | 4.0409 | −3.393 | 12.447 | 1.255 | 1 | .263 | |

| Immobilizers and Stents (REF) | ||||||||

| Comfort Global Impressions | Days After Surgery | 3.061 | .3767 | 2.323 | 3.799 | 66.049 | 1 | <.001 |

| Child Age | −.688 | .8470 | −2.349 | .972 | .660 | 1 | .416 | |

| Feeding Methods ± GERD Treatment | 35.706 | 3 | <.001 | |||||

| One Method, No GERD | 16.018 | 3.0048 | 10.129 | 21.908 | 28.419 | 1 | <.001 | |

| One Method with GERD | 13.780 | 3.4694 | 6.980 | 20.580 | 15.776 | 1 | <.001 | |

| Two or Three Methods, no GERD | 12.726 | 4.4627 | 3.979 | 21.473 | 8.132 | 1 | .004 | |

| Two or Three Methods with GERD (REF) | ||||||||

| Immobilizers/Nasal Stents | 10.582 | 3 | .014 | |||||

| No Immobilizers or Nasal Stents | 14.702 | 4.7341 | 5.423 | 23.980 | 9.644 | 1 | .002 | |

| Immobilizers only | 6.244 | 4.3130 | −2.209 | 14.698 | 2.096 | 1 | .148 | |

| Nasal Stents only | 5.746 | 4.3080 | −2.697 | 14.190 | 1.779 | 1 | .182 | |

| Immobilizers and Stents (REF) | ||||||||

| Behavioral and Emotional Global Impressions | Days After Surgery | 2.673 | .3708 | 1.946 | 3.399 | 51.955 | 1 | <.001 |

| Child Age | −.534 | .7723 | −2.048 | .980 | .478 | 1 | .489 | |

| Feeding Methods ± GERD Treatment | 16.368 | 3 | <.001 | |||||

| One Method, No GERD | 13.323 | 3.3061 | 6.843 | 19.803 | 16.240 | 1 | <.001 | |

| One Method with GERD | 8.018 | 3.7011 | .764 | 15.272 | 4.693 | 1 | .030 | |

| Two or Three Methods, no GERD | 9.784 | 4.7674 | .440 | 19.128 | 4.212 | 1 | .040 | |

| Two or Three Methods with GERD (REF) | ||||||||

| Immobilizers/Nasal Stents | 7.858 | 3 | .049 | |||||

| No Immobilizers or Nasal Stents | 12.375 | 4.4520 | 3.649 | 21.101 | 7.726 | 1 | .005 | |

| Immobilizers only | 6.390 | 3.9899 | −1.430 | 14.210 | 2.565 | 1 | .109 | |

| Nasal Stents only | 7.523 | 4.0660 | −.446 | 15.493 | 3.424 | 1 | .064 | |

| Immobilizers and Stents (REF) | ||||||||

Note: Results based on 545 observations across seven days from 84 subjects. GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease. REF = Reference Group.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Daily Comfort and Behavioral and Emotional Health Scale and Global Impression estimated mean scores across T1 reporting days by number of feeding methods (Method) and treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (A-D) and across T1 reporting days by use of immobilizers and nasal stents (E-H).

Note: All scores were scaled 0-100 such that higher scores represent better functioning. Diaries providing data for these graphs were completed on at least one day by 84 different caregivers for a total of 545 observations. Differences in daily changes by Method and GERD across time were significant for Comfort and Behavioral and Emotional Health Scale and Global Impression scores (all p’s <.001). Differences in daily scores by use of immobilizers and/or stents were significant for the COMF and BEH IMPR scores (p’s = .014 and .049) with a trend for the COMF SCALE (p = .098) (See Table 4 for details).

Figure 2 E-H illustrates changes across time based on use of immobilizers and nasal stents. In each case, caregivers of infants who did not use immobilizers or have nasal stents in place reported the highest daily COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR scores while infants who used both immobilizers and nasal stents had the lowest scores across the seven-day reporting period and, except for the BEH SCALE (BETA = 7.88, p = .209), these differences were significant (BETA’s =12.36 to 16.23, p’s = .015 to .004) (Table 4 for details).

Discussion

This study evaluated the sensitivity to change of daily ratings of the comfort, behavioral, and emotional well-being of the iCOO while centering around a stressful event, such as surgery. In addition, the association of post-surgical interventions on iCOO ratings was assessed. Previous studies have primarily focused on the impact of intervention on parent QoL and emotional stress. This study’s unique contribution is the focus on the child’s experience of these intervention based on parent’s perspective. This information could help providers and caregivers understand the typical trajectory of comfort and psychological well-being after cleft lip repair as well as identify infants who may need additional care.

To accomplish these goals, it was necessary to first determine if the iCOO COMF and BEH scales reliably tracked daily comfort and psychological health when infants were not experiencing a stressful event. Once reliability was established, the next step was to compare the daily post-operative COMF and BEH scores to pre-operative and 2-month post-operative scores and determine if there were specific post-surgical interventions that were associated with lower COMF and BEH scores. Two types of scores, were utilized in this study, SCALE provided information about observable signs and IMPR about caregivers’ judgments of infant comfort and well-being.

Aim 1. Comparison of COMF and BEH Outcomes Across Time Periods

The iCOO COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR measures proved to be reliable as evidenced by the consistency in daily ratings just prior to lip surgery and as well as two months after surgery where there was no intervening event, such as surgery. As anticipated, the lower iCOO ratings immediately after surgery reflected the changes in both the infant’s comfort and psychological health. The sharp drop in SCALE and IMPR scores immediately post-surgery along with the steady increase in scores during the subsequent post-surgery days illustrates the sensitivity of these measures in detecting changes in the infants’ levels of comfort and psychological well-being. However, our hypothesis that infants would return to their pre-surgery level of BEH and COMF by a week after surgery was not upheld. Although the BEH and COMF scores steadily improved across the post-surgical week, both scores were still significantly lower than pre-surgical scores on the eighth day after surgery. It is not clear from the data when the infants actually returned to pre-surgical levels of behavior and comfort, though the scores at two-months post-surgery were similar to pre-surgical scores.

Aim 2. Comparison of T0 to T1 and T2 COMF and BEH Outcomes

Caregivers reported higher levels of infant distress, poorer self-regulation and impaired interactions with others during the week post-surgery compared to baseline and two-months post-surgery. The immediate post-surgery COMF and BEH IMPR scores were sharply decreased from those at baseline while caregiver reports at two-months post-surgery were comparable to those at baseline.

It was expected that caregivers would report increased discomfort and more behavioral and emotional distress for their infants immediately after surgery, with a return to pre-surgical levels by one week after surgery (see acpa-cpf.org and https://myhealth.alberta.ca). However, while COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR scores demonstrated steady improvement, they did not reach baseline levels 8 days after surgery. This is important information for providers to use when informing and reassuring caregivers. There is a lack of literature examining the length of time it takes for a baby’s comfort and behavior and emotional health to return to baseline after surgery. Rosenberg RE, et al.23 assessed infant pain after various craniofacial surgeries, including cleft lip surgery, but only for the first 24 hours. Studies involving infants undergoing cleft lip surgery have typically focused on parental anxiety or coping but have not examined the infant’s well-being (e.g., Yilmaz & Abuhan24). Despite the lack of objective data, there is information about infant recovery from cleft lip surgery generally from craniofacial team websites, national organizations, and caregiver support groups. Some sites described a range of 2 days to one week for pain to subside and for the baby to return to their pre-surgical behavior (e.g., ACPA Family Services25; myhealthalberta.com) while other sites described length of time needed for pain medication, use of restraints, and healing, which could take up to 5 weeks (see www.clapa.com; https://www.verywellhealth.com). Infant comfort or behavior was seldom mentioned. Since caregivers frequently rely on these types of online resources, it is critical that accurate information about infant recovery from surgery from the caregiver’s perspective is obtained.

By two-months post-surgery, caregiver ratings on the iCOO COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR measures indicated that the infant’s levels of comfort and emotional and behavioral well-being met or exceeded baseline levels. In addition, the daily reporting during the 2-month time point was consistent over time. Due to the large interval between Day 7 of the immediate post-surgery data reports and the two-month post-surgery reports, the exact time point of the return to T0 levels is unclear. Scores were near baseline levels on Day 7 of T1 but still significantly lower. However, by two-months after surgery, infants appear to have made a full recovery from surgery and its attendant interventions based on both caregiver observations and impressions. Further research is needed to determine how long full recovery takes, to identify individuals at risk of slower recovery, and to assess effective interventions associated with faster recovery. However, it appears that infants who undergo CL surgery take time to exhibit full emotional, behavioral and comfort recovery. Using this knowledge, providers can inform caregivers of infants with CL that behavioral and emotional recovery after surgery may take longer than a week, but that most infants will fully recover by 2 months after surgery.

Aim 3. Impact of Post-Surgery Interventions on Time 1 COMF and BEH Outcomes

Post-surgical interventions, when examined individually, had a higher association with caregiver impressions (IMPR) than ratings of observable signs (SCALE) of infant COMF and BEH. Specifically, based on caregiver impressions, a greater number of feeding methods utilized, the use of immobilizers, and the presence of nasal stents post-surgery were associated with decreased COMF and BEH IMPR scores. In addition, caregiver impressions of infants who required treatment for GERD were associated with decreased BEH IMPR scores. The pattern of responses was similar for the COMF and BEH SCALE scores, but these responses did not reach statistical significance. In contrast, there was little evidence that airway treatments or type of post-operative pain medication choices were associated with COM or BEH SCALE or IMPR scores.

Surgery is a significant stressor due to pain, effects of anesthesia, and physical trauma.26 The use of interventions post-surgery to improve aesthetic results of surgery (e.g., nasal molding, immobilizers, change in feeding methods) and to manage other existing medical issues (e.g., treatment for GERD), were associated with increased post-surgery distress. This outcome is not surprising as common post-surgical treatments such as immobilizers limit the child’s movement and ability to play, which can lead to discomfort, increased frustration, and behavioral challenges. Furthermore, children who have treatment for GERD are at greater risk for experiencing irritability, pain, vomiting, and challenges with sleeping (e.g., wedge, sleep in certain position). They often need additional medication and may not have an appetite. Finally, a change in feeding method, generally to a syringe or open cup, during the immediate post-surgery period is often recommended to prevent wound dehiscence, though there is little objective evidence to support the need for this change.27,28 Of the infants using more than one feeding method post-surgery in this study, 76% used a syringe, some type of open cup or a spoon as one of the methods. The review by Matsunaka et al.28 suggests that use of these alternative methods results in longer feeding times and poorer weight gain.

Having a combination of two interventions, specifically an increased number of changes in feeding methods and treatment for GERD or combining the use of nasal stents and immobilizers, were associated with lower scores for COMF and BEH SCALE and IMPR scores. It is possible that the presence of GERD was associated with greater discomfort during feedings as well as behavioral challenges with feeding, which may have also prompted more frequent changes in feeding methods. Nasal stents and immobilizers both impose physical limitations upon the infant. Although nasal stents alone and use of immobilizers only each had an impact on COMF and BEH IMPR and SCALE, having the combination of these two interventions leads to greater physical limitations, hence greater distress.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Because the study was not randomized and lacked a control group, conclusions about associations between surgical treatments and outcomes cannot be interpreted as causal effects. All data is based on caregiver report, including reports of post-surgical treatments received by the infants. The infants were treated by many different cleft teams and surgeons, resulting in a wide variation in treatment protocols. While this increased the richness of the data set, it also allowed for potential errors and missing data because caregivers either were not told or did not remember what treatments their children received. The impact of the missing data was not measurable in this study.

The subjects in this study were recruited widely and are representative of the US population in some respects. However, our subject pool was primarily White and of higher socio-economic status with 84% of respondents have at least some college. There was no difference in reports of infant comfort or psychological well-being that were associated with race, income, or caregiver education in this study. Larger samples may be necessary to determine if differences exist.

This study focused on caregiver perceptions of their child’s comfort and behavioral and emotional health following lip surgery. We did not assess how caregiver’s own emotional health might affect their responses on the iCOO COMF and BEH scales. For example, we did not collect information on caregiver stress, which can affect a caregiver’s relationship with their child29 and has even been shown to be related to infant and toddler expressions of pain after surgery.23 Emotional distress has also, anecdotally, been associated with the change in the infant’s facial appearance post-surgery. While there is often an expectation that caregivers will experience relief when the cleft is closed, many caregivers initially report sadness that their infant’s original smile is lost.

Future Studies

Infant emotional well-being and comfort was negatively associated with the use of arm/hand immobilization after surgery. Since more than a third of caregivers reported that they did not use any type of immobilization device to prevent the infant from touching the healing lip, it would be beneficial to do a prospective, randomized trial of the impact of immobilization devices on both infant comfort/well-being and the outcome of lip surgery. In addition, future studies should examine other possible causes and modifiable risk factors that create post-operative discomfort and psychological distress.

Although the iCOO’s COMF and BEH scales were originally utilized to assess behavior and comfort of infants with CL±P, the BEF and COMF scales do not specify CL±P as their only focus. Therefore, these iCOO scales may be useful to assess well-being and comfort of infants who present with a variety of medical conditions that require invasive treatments or surgery. Studies to evaluate the iCOO in other settings could inform providers and caregivers of the infant’s response to interventions and identify the need for additional care.

In order to get a better understanding as to what time point the infants’ levels of emotional and behavioral well-being returned to pre-surgical levels, a longer post-surgery period of observation would be needed.

Conclusion

This study investigated longitudinal changes in comfort, behavioral and emotional health in infants after cleft lip repair based on caregiver observations and evaluated the relationships between these domains and post-surgical treatments. Overall, the iCOO COMF and BEH global impression scales and individual scale items demonstrated consistency when no intervention was present (T0 and T2) and acceptable sensitivity to change after cleft lip surgery. Caregivers reported a significant drop in scores immediately after surgery with a gradual increase across the post-surgery week. While mean scores of the infants had not returned to baseline levels in the week immediately post-surgery, they were on track to do so. Further research is needed to determine those infants who are at risk for challenging recoveries as well as the time needed for full psychological recovery. Findings demonstrate that caregivers are reliable reporters and ObsROs such as the iCOO may provide a meaningful way to assess infant response to treatments. Clinicians and researchers interested in obtaining a copy of the iCOO can find additional information here: https://redcap.link/icoo.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (R01DE024986).

Abbreviations

- BEH

Behavioral and Emotional Health Domain

- CL

Cleft Lip

- CL±P

Cleft Lip with or without Cleft Palate

- CP

Cleft Palate

- COMF

Comfort Domain

- FEED

Number of Feeding Methods Used

- GEE

General Estimating Equation

- GERD

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

- iCOO

Infants with Clefts Observation Outcomes Instrument

- IMMOB

Immobolizers

- IMPR

Impression item

- NAM

Nasoalveolar Molding Appliance

- ObsRO

Observer Reported Outcomes

- SCALE

Scale items

- T0

Before CL Surgery

- T1

Day 2 After CL Surgery

- T2

2-months after CL surgery

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None of the authors have conflicts of interest to report with this study.

The findings presented in this paper have not been previously disseminated. However, the process of development of the instrument used and the data on the validity and reliability of the scales used in this paper have been published or submitted for publication (Heike et al., 2020; Edwards et al., under review; See reference page for full citations)

Contributor Information

Janine M. Rosenberg, University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System, Craniofacial, Chicago, Illinois.

Claudia Crilly Bellucci, Shriners Hospitals for Children, Chicago Cleft/Craniofacial, Chicago, Illinois.

Todd C. Edwards, University of Washington, Health Services, Seattle, Washington.

Carrie L. Heike, Seattle Children's Hospital, Craniofacial Center, Seattle, Washington.

Brian G. Leroux, University of Washington, Dentistry, Seattle, Washington.

Salene M. Jones, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Public Health Sciences, Seattle, Washington.

Laura P. Stueckle, Seattle Children's Hospital, Craniofacial, Seattle, Washington.

Donald L. Patrick, University of Washington, School of Public Health, Seattle, Washington.

Meredith Albert, Shriners Hospitals for Children Chicago, Cleft/Craniofacial, Chicago, Illinois.

Cassandra L. Aspinall, Children's Hospital and Regional Medical Center, Social Work, Seattle, Washington.

Kathleen A. Kapp-Simon, Shriners Hospitals for Children, Cleft/Craniofacial Chicago, Illinois and University of Illinois at Chicago, Surgery Chicago, Illinois.

References

- 1.Clinton J, Feller AF, Williams RC. The importance of infant mental health. Paediatr Child Heal. 2016;21(5):239–241. doi: 10.1093/pch/21.5.239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tronick E. The Neurobehavioral and Social-Emotional Development of Infants and Children. WW Norton & Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan MW, Lewis M. Emotional expressions of young infants and children: A practitioner’s primer. Infants Young Child. 2003;16(2):120–142. doi: 10.1097/00001163-200304000-00005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heatherington MM. Understanding infant eating behaviour - Lessons learned from observation. Physiol Behav. 2017;176:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mai CT, Isenburg JL, Canfield MA, et al. National population-based estimates for major birth defects, 2010 -2014. Birth Defects Res. 2019;111(18):14200–1435. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ACPA-CPF. Parameters for the Evaluation and Treatment of Patients with Cleft Lip/Palate or Other Craniofacial Anomalies. American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal 1993; 30 (Suppl 1); Revised 2018. https://acpa-cpf.org/team-care/standardscat/parameters-of-care/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg J, Albert M, Aspinall C, et al. Parent observations of the health status of infants with clefts of the lip: Results from qualitative interviews. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J. 2019;56(5):646–657. doi: 10.1177/1055665618793062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray L, De Pascalis L, Bozicevic L, Hawkins L, Sclafani V, Ferrari PF. The functional architecture of mother-infant communication, and the development of infant social expressiveness in the first two months. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):39019. doi: 10.1038/srep39019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams V, DeMuro C, Lewis S, et al. Psychometric evaluation of a caregiver diary for the assessment of symptoms of respiratory syncytial virus. J Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2018;2(10):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s41687-018-0036-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Popp L, Fuths S, Schneider S. The relevance of infant outcome measures : A pilot-RCT comparing baby triple p positive parenting program with care as usual. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2425. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walton MK, Powers JH 3rd, Hobard J, et al. Clinical outcome assessments: Conceptual foundation - report of the ISPOR clinical outcomes assessment - emerging good practices for outcomes research task force. Value Heal. 2015;18(6):741–742. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merkel S, Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S. Pain assessment in infants and young children: The FLACC Scale: A behavioral tool to measure pain in young children. Am J Nurs. 2002;102(10):55. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200210000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beltramini A, Milojevic K, Pateron D. Pain assessment in newborns, infants, and children. Pediatr Ann. 2017;46(10):e387–e395. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20170921-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crellin DJ, Harrison D, Santamaria N, Huque H, Babl FE. The psychometric properties of the FLACC scale used to assess procedural pain. J Pain. 2018;19(8):862–872. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards TC, Emerson J, Genatossio A, et al. Initial development and pilot testing of observer-reported outcomes (ObsROs) for children with cystic fibrosis ages 0-11 years. J Cyst Fibros. 2018;17(5):680–686. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uhl K, Litvinova A, Sriswasdi P, Zurakowski D, Logan D, Cravero JP. The effect of pediatric patient temperament on postoperative outcomes. Pediatr Anaesth. 2019;29(7):721–729. doi: 10.1111/pan.13646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feragen KB, Semb G, Heliovaara A, et al. Scandcleft randomised trials of primary surgery for unilateral cleft lip and palate: 10. Parental perceptions of appearance and treatment outcomes in their 5-year-old child. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2017;51(1):81–87. doi: 10.1080/2000656X.2016.1254642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards TC, Heike CL, Kapp-Simon KA, et al. Infant with Clefts Observation Outcomes Instrument (iCOO): A new outcome for infants and young children with orofacial clefts. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 2021;Sept. doi: 10.1177/10556656211040307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heike CL, Albert M, Aspinall CL, et al. Development of an outcome measure of observable signs of health and well-being in infants with orofacial clefts. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J. 2020;57(11):1266–1279. doi: 10.1177/1055665620922105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. doi: 10.1093/biomet/73.1.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. doi: 10.4324/9780203771587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberg RE, Clark RA, Chibbaro P, et al. Factors predicting parent anxiety around infant and toddler postoperative and pain. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(6):313–319. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yilmaz HN, Abuhan E. Maternal and paternal anxiety levels through primary lip surgery. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;121(5):478–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2020.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ACPA Family Services. Preparing for Surgery. Published online 2019. https://acpa-cpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Preparing-for-Surgery.pdf

- 26.McGrath PJ. Science is not enough: The modern history of pediatric pain. Pain. 2011;152(11):2457–2459. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bessell A, Hooper L, Shaw WC, Reilly S, Reid J, Glenny AM. Feeding interventions for growth and development in infants with cleft lip, cleft palate or cleft lip and palate. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011(2). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003315.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsunaka E, Ueki S, Makimoto K. Impact of breastfeeding and/or bottle-feeding on surgical wound dehiscence after cleft lip repair in infants: A systematic review. J Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg. 2019;47(4):570–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2019.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pope AW, Tillman K, Snyder HT. Parenting stress in infancy and psychosocial adjustment in toddlerhood: a longitudinal study of children with craniofacial anomalies. Cleft Palate - Craniofacial J. 2005;42(5):556–559. doi: 10.1597/04-066r.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.