Abstract

The ɛ stem-loop at the 5′ end of the pregenomic RNA of the hepatitis B viruses is both the primary element of the RNA packaging signal and the origin of reverse transcription. We have previously presented evidence for a third essential role for ɛ, that of an essential cofactor in the maturation of the viral polymerase (J. E. Tavis and D. Ganem, J. Virol. 70:5741–5750, 1996). In this case, binding of ɛ to the polymerase is proposed to induce a physical alteration to the polymerase that is needed for it to develop enzymatic activity. Three lines of evidence employing duck hepatitis B virus supporting this hypothesis are presented here. First, an unusual DNA polymerase activity employing exogenous RNAs (the trans reaction) that was originally discovered with recombinant duck hepatitis B virus polymerase expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts was shown to be an authentic property of the viral polymerase. The trans reaction was found to be template-dependent reverse transcription of the exogenous RNA. The trans reaction occurred independently of the hepadnavirus protein-priming mechanism, yet it was still strongly stimulated by ɛ. This directly demonstrates a role for ɛ in activation of the polymerase. Second, the reverse transcriptase domain of the polymerase was shown to be physically altered following binding to ɛ, as would be expected if the alteration was required for maturation of the polymerase to an enzymatically active form. Finally, analysis of 15 mutations throughout the duck hepatitis B virus polymerase demonstrated that the ɛ-dependent alteration to the polymerase was a prerequisite for DNA priming, reverse transcription, and the trans reaction.

The hepatitis B viruses (hepadnaviruses) are small DNA-containing viruses that replicate by reverse transcription (reviewed in reference 3). The interaction between the hepadnavirus polymerase and a stem-loop (ɛ) at the 5′ end of the viral pregenomic RNA is a key event early in reverse transcription. ɛ is the primary element of the hepadnaviral RNA packaging signal (6, 7, 11) and is the origin of reverse transcription (10, 14, 19, 21). Binding between the polymerase and ɛ is required for RNA packaging. If the complex does not form, neither the polymerase nor the pregenomic RNA is incorporated into viral cores (1, 5). The polymerase initiates reverse transcription within a bulge in ɛ and synthesizes a 3- to 4-nucleotide (nt) minus-strand DNA which is covalently linked to the polymerase by virtue of the protein-priming mechanism of the hepadnaviruses (4, 20). This nascent minus-strand DNA is then transferred from ɛ at the 5′ end of the RNA pregenome to a short region of homology near the 3′ end of the RNA prior to further chain elongation (10, 14, 19, 21).

Using recombinant duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV) polymerase expressed both in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (TYDP [16]) and translated in rabbit reticulocyte lysates (DP [20]), we have presented two lines of evidence implying that the interaction between the polymerase and ɛ has another key role early in hepadnavirus reverse transcription; this interaction also appears to be needed for the polymerase to mature to an enzymatically active form (18).

The first evidence for a role of ɛ in the maturation of the polymerase is genetic and was obtained with TYDP expressed in S. cerevisiae. The key observation was made with a newly discovered activity of TYDP that synthesizes DNA at the 3′ end of exogenously added RNAs independently of the hepadnavirus protein priming reaction (the trans activity). TYDP could perform the trans reaction only when it had been translated in the presence of ɛ sequences competent to support protein-primed reverse transcription, despite the fact that the trans reaction does not employ protein-primed initiation (18). This indicated that ɛ has an additional role in DNA synthesis beyond being the origin of reverse transcription. The second line of evidence for a role for ɛ in the maturation of the polymerase is structural. Translation of DP in the presence of ɛ sequences competent to support RNA packaging and DNA synthesis resulted in significantly increased resistance to proteolysis relative to DP translated in the absence of a biologically functional ɛ (18). This demonstrated that the interaction with ɛ induces a structural alteration to the polymerase prior to its development of enzymatic activity.

These data led to a model in which the polymerase binds to ɛ, undergoes a reversible alteration, and then becomes active (18). Here, we present three additional lines of evidence supporting this maturation model. First, we show that the trans activity is reverse transcription of the exogenous RNA and is an authentic property of the DHBV polymerase. Second, the maturation model predicts that the ɛ-dependent alteration to the polymerase would somehow affect the reverse transcriptase domain to activate it. This prediction is fulfilled by mapping the region of the polymerase that is altered following binding of ɛ to the reverse transcriptase domain itself. Finally, the correlation between adoption of the ɛ-dependent altered state and the development of enzymatic activity of the polymerase is expanded through analysis of 15 mutant polymerases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA constructs and in vitro transcription.

RNAs were transcribed with Megascript kits (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. mRNAs for DHBV polymerase lacking ɛ were transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase from AflII-linearized pT7DPol. pT7DPol contains DHBV3 (nt 170 to 3021) within pBluescript (Stratagene Cloning Systems); the allele employed contains a 33-nt insertion at nt 901 encoding the influenza virus hemagglutinin epitope (8). The mRNAs for the carboxy-terminal truncations of the polymerase containing 567, 652, 679, or 728 amino acids were produced from pT7DPol truncated at the BspHI, AseI, SgrAI, and NcoI sites, respectively.

The plasmid pdɛ contains the DHBV ɛ coding sequences within pBluescript (12). ɛ-containing RNAs were transcribed with T3 RNA polymerase from EcoRV- linearized pdɛ to produce 172-nt transcripts.

The plasmid pDRF contains DHBV (nt 2401 to 2605) within pBluescript. Linearization of pDRF with EcoRI followed by transcription with T3 RNA polymerase produces a 265-nt positive-polarity RNA (DRF+) that does not contain the complete ɛ and cannot bind to the DHBV polymerase. Linearization of pDRF with PstI followed by transcription with T7 RNA polymerase produces a 253-nt minus-polarity RNA (DRF−).

D1.5G contains 1.5 copies of DHBV3 (duplication of nt 1658 to 3021) in pBluescript and produces wild-type DHBV following transfection into avian cells. The YMHA (D513H/D514A) polymerase-active site missense mutations were inserted into the 3′ copy of the duplication to produce the plasmid D1.5G-YMHA.

The plasmid pTYBDP for expression of recombinant DHBV3 polymerase in S. cerevisiae has been described previously (17, 19). The mutant polymerases listed in Table 1 were produced from mutant derivatives of pTYBDP and pT7DPol.

TABLE 1.

Correlation between ɛ-dependent alteration and enzymatic activity for mutant DHBV polymerasesa

| Mutation(s) | Domain | ɛ bindingb | Protease resistanceb | DNA primingb | DNA synthesisc | trans reactionb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | None | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Y96F | Terminal protein | +++ | +++ | − | −d | +++ |

| F103Y and N104D | Terminal protein | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| K153E | Terminal protein | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| Y156H and D158L | Terminal protein | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | +++ |

| K182E and R183E | Terminal protein | − | − | − | − | − |

| F391H and L392D | Reverse transcriptase | − | − | − | − | − |

| K394L and K395I | Reverse transcriptase | ++ | + | − | − | − |

| N399D and T400A | Reverse transcriptase | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| R404E | Reverse transcriptase | +++ | +++ | − | − | − |

| D513H and D514A (“YMHA”) | Reverse transcriptase | +++ | +++ | − | − | − |

| D666N | RNase H | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| T668V and T670V | RNase H | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| H693Y | RNase H | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| E696R and L698T | RNase H | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| D715V | RNase H | NDe | +++ | ++ | + | ++ |

Activities relative to the wild-type polymerase are indicated as follows: +++, 70 to 100%; ++, 10 to 70%; +, 1 to 10%; and −, no detectable activity.

Determined relative to in vitro-translated DP.

Determined relative to TYDP expressed in S. cerevisiae.

Determined relative to the wild-type polymerase within intracellular viral cores.

ND, not determined. However, binding must occur because polymerases containing the D715V mutation can package pregenomic RNA into viral cores (24).

Transfection of LMH cells and isolation of viral cores.

LMH cells (a chicken hepatoma cell line) were transfected by calcium phosphate coprecipitation as described previously (19). Three days posttransfection, the cells were lysed by the addition of 1 ml of lysis buffer (1 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 0.25% Nonidet P-40, 50 mM NaCl, and 8% sucrose). The lysate was brought to 10 mM CaCl2 and clarified at 13,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was treated with 100 U of micrococcal nuclease (Boehringer Mannheim) at 37°C for 45 min, and digestion was stopped by the addition of EDTA to 15 mM. The sample was clarified at 13,000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was layered over a 30% sucrose cushion and centrifuged at 245,000 × g for 2 h. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was dissolved in 50 μl of B/EDTA (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.8], 15 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA) containing 5% sucrose per 100-mm-plate of cells.

Isolation of recombinant virus-like particles.

Virus-like particles were isolated as described earlier (16), with a minor modification. S. cerevisiae cultures containing TYDP expression plasmids were induced by the addition of galactose, and 20 h later cells were lysed. The clarified lysate was layered onto a two-layer sucrose step gradient (30 and 20%) and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 3 h. The pellet was suspended in buffer B/EDTA containing 5% sucrose.

In vitro translation.

35S-labeled DHBV polymerase was translated in vitro by employing the Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate System (Promega) and [35S]methionine (>1,000 Ci/mMol; Amersham) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Reverse transcription on exogenous templates (the trans reaction).

DNA polymerase activity employing exogenous RNA substrates was detected with recombinant TYDP by treating 5 μg of protein with 5 U of micrococcal nuclease (Boehringer Mannheim) and 5 mM CaCl2 at 37°C for 20 min to destroy the endogenous nucleic acids and then terminating the digestion by the addition of EGTA to 7.5 mM. The mixture was adjusted to 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0)–100 mM NaCl–0.1% Nonidet P-40–10 mM MgCl2–2.5% 2-mercaptoethanol–4 U of RNasin (Promega)–100 μM each dATP, dCTP, and dTTP. A total of 2 μCi of [α-32P]dGTP and 1.5 μg of RNA substrate was added, and the reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h. To detect the trans activity within viral cores, the cores were permeabilized by brief treatment at low pH (13) prior to the micrococcal nuclease treatment, and DNA synthesis was measured as described for TYDP. To detect the trans reaction with in vitro-translated polymerase, DP translation mixtures were diluted twofold to a final concentration of 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0)–30 mM NaCl–10 mM MgCl2–100 μM each dATP, dCTP, and dTTP. A total of 2 μCi of [α-32P]dGTP and 1.5 μg of RNA substrate was added, and the reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. In all cases, the nucleic acid products of the trans reactions were purified by phenol and chloroform extraction, precipitated with ethanol, and resolved by electrophoresis on denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gels. For Fig. 2C, RNA in the trans product was hydrolyzed in 250 mM NaOH at 100°C for 15 min and neutralized with HCl prior to loading on the gel; the NaCl concentration of the untreated sample was balanced with that of the hydrolyzed sample to correct for potential electrophoretic effects.

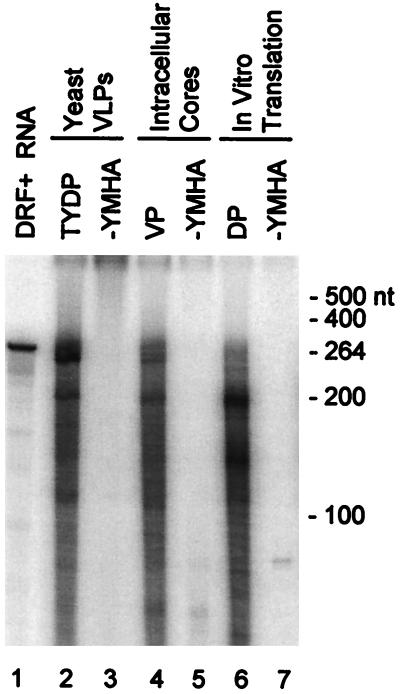

FIG. 2.

trans products contain RNA-DNA chimeras produced by reverse transcription of the input RNA. (A) trans reaction requires all four dNTPs. Permeabilized DHBV cytoplasmic cores and DRF+ RNA were employed in the trans reaction in the presence of dATP, dCTP, dTTP, and [α-32P]dGTP (lanes 1 and 2) or with [α-32P]dGTP alone (lanes 3 and 4). VP, wild-type DHBV polymerase; −YMHA, polymerase active-site missense mutant. The mobilities of the single-stranded RNA markers are indicated to the left. (B) trans reaction products hybridize specifically to DRF+ and DRF− RNAs. A trans reaction was performed with permeabilized DHBV viral cores and DRF+ RNA, and the products were purified with phenol and chloroform extraction and were subjected to alkaline hydrolysis to remove any RNA. The RNAs indicated to the left were bound to filters with a slot blot apparatus. The purified trans product was used to probe to filter 1, and internally labeled DRF+ and DRF− RNAs were used to probe filters 2 and 3, respectively. The filters were washed at high stringency. (C) The products of the trans reaction include RNA-DNA chimeras. A trans reaction was performed with permeabilized DHBV viral cores and DRF+ RNA, and the products were purified with phenol and chloroform extraction. Half of the sample was subjected to alkaline hydrolysis, and half was mock hydrolyzed. The samples were then resolved by electrophoresis on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The mobilities of the single-stranded RNA size markers are indicated to the left.

Slot blot analysis of the trans reaction.

Target RNAs (0.1 μg) were transferred to Hybond N (Amersham) membranes and were cross-linked with UV light. The membranes were blocked at 65°C in Church buffer (2) for 2 h and then hybridized overnight at 65°C in the same buffer. Control probes were internally labeled DRF+ or DRF− RNAs. The trans product probe was prepared with intracellular DHBV cores and DRF+ RNA. Following the trans reaction, the products were purified and the RNA in the sample was hydrolyzed as described above. The DNA was used as a hybridization probe overnight at 65°C in Church buffer. All filters were washed at high stringency: twice in 2× SSC (0.3 M NaCl, 0.03 M sodium citrate [pH 7.0])–0.1% sodium docecyl sulfate (SDS) for 20 min at 65°C and then twice in 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS for 20 min at 65°C.

DNA synthesis by recombinant TYDP.

Reverse transcription by recombinant TYDP within yeast-derived VLPs has been described previously (18).

Partial proteolysis of ɛ-polymerase complexes.

Partial proteolysis of in vitro-translated DP was performed as described earlier (18).

DNA priming.

DNA priming was detected by a modification of the conditions described by Wang and Seeger (20). DP was translated in the presence of ɛ, and then 5 μCi of [α-32P]dGTP and MgCl2 (to 4 mM) was added. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, the reactions were terminated by addition of Laemmli loading buffer, and the products were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

ɛ-polymerase binding.

Binding assays were performed as described by Pollack and Ganem (12).

RESULTS

The trans reaction is an authentic property of the DHBV polymerase.

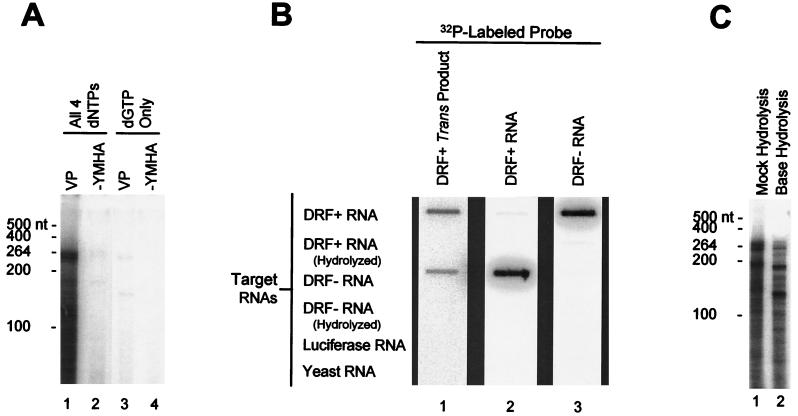

The key observation implying a functional role for ɛ in the maturation of the polymerase was that recombinant TYDP expressed in yeast cells needed to be translated in the presence of ɛ to be able to synthesize DNA on exogenous RNAs in the trans reaction, even though ɛ itself was not the substrate (18). We compared the ability of TYDP with that of native DHBV polymerase within permeabilized viral cores (VP) and of DP translated in vitro in the presence of ɛ to perform the trans reaction (Fig. 1). The nucleic acids within the viral cores and translation mixtures were removed with micrococcal nuclease, and a trans reaction was performed with DRF+ RNA. The products were purified by phenol and chloroform extraction and resolved on denaturing polyacrylamide gels. DHBV polymerase could perform the trans reaction regardless of the source of the enzyme (Fig. 1, lanes 2, 4, and 6). In all cases, the YMHA polymerase-active site missense mutations eliminated DNA synthesis (lanes 3, 5, and 7). The products ranged in size from a few nucleotides to approximately the size of the 264-nt substrate RNA. The three polymerases produced very similar sets of products, but with various size distributions. Omission of the permeabilization step with native viral cores precluded formation of the trans product (data not shown). These data indicate that the ability to perform the trans reaction is an authentic property of the DHBV polymerase.

FIG. 1.

trans activity is an authentic property of the DHBV polymerase. DHBV polymerase (expressed in yeast VLPs [TYDP], in permeabilized native viral cores [VP], or translated in vitro [DP]) was treated with micrococcal nuclease to degrade the endogenous nucleic acids and was employed in a trans assay with DRF+ RNA. The products were purified by phenol and chloroform extraction prior to resolution on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. DRF+ RNA, internally labeled DRF+ (264 nt); −YMHA, the polymerase active-site missense mutant. The mobilities of single-stranded RNA markers are indicated to the right.

The trans reaction is reverse transcription of the input RNA.

To determine if the trans product was synthesized in a template-dependent manner, a trans reaction was performed with the native polymerase, DRF+ RNA, and dATP, dCTP, dTTP, and [α-32P]dGTP (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 2) or with [α-32P]dGTP alone (lanes 3 and 4). The trans product was observed with the native polymerase when all four dNTPs were present but was nearly undetectable in reaction mixtures containing only [α-32P]dGTP. There was also a faint signal in reaction mixtures containing the YMHA polymerase active-site mutant (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 4); this product is also occasionally observed in extracts from mock-transfected cells and hence is produced by a cellular polymerase (data not shown). These data indicate that the trans product was probably made by a template-dependent reaction and not by a terminal-transferase-like reaction. If this were so, the products should have contained sequences derived from the input RNA. Therefore, a trans reaction was performed with native viral cores and DRF+ RNA, and the products were purified and hydrolyzed with NaOH to remove the input RNA. This DNA was used to probe filter-bound RNAs (Fig. 2B). The trans product annealed under highly stringent conditions to the DRF+ and DRF− target RNAs with roughly equal efficiencies but not to the negative-control luciferase or whole-cell yeast RNAs. This indicates that the trans product contains specific sequences derived from the input RNA and that these sequences are of both polarities. Consistent with the ability of the trans product to anneal to both positive- and negative-polarity DRF RNAs, the majority of the trans products were resistant to digestion with S1 nuclease, indicating that the products are largely double stranded (data not shown).

Other RNAs (DHBV sequences or heterologous sequences) could replace DRF+ in the trans reaction. As before, the products ranged in size from a few nucleotides in length to approximately the size of the input RNA (data not shown). However, the trans reaction yielded no products when the exogenous RNA was omitted from the reaction or when DNA oligonucleotides were substituted for the RNA substrate (18; data not shown).

A trans reaction was performed with native viral cores and DRF+ RNA, and the purified products were subjected to alkaline hydrolysis to remove the RNA. Alkaline hydrolysis reduced the size distribution of the products. Although it is impossible in this experiment to determine the size reduction of an individual molecule, the most prominent bands in the hydrolyzed samples are 7 to 35 nt shorter than are the most prominent bands in the untreated sample (Fig. 2C). Similar results were observed with the trans products produced by TYDP and DP (data not shown). This confirms the previous observation that a significant proportion of the trans product was an RNA-DNA chimera (18).

The trans reaction does not involve protein-primed initiation.

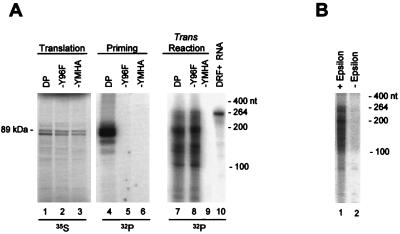

DP, DP-Y96F, and DP-YMHA were translated in vitro in the presence of ɛ and were employed in DNA priming and trans reactions. The Y96F mutation removes the tyrosine hydroxyl that primes DHBV DNA synthesis and hence eliminates protein-primed initiation and subsequent reverse transcription (23, 25). DP was active in both the DNA priming and the trans reactions (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 7), whereas Y96F was active only in the trans reaction (Fig. 3A, lanes 5 and 8). The active-site missense mutant YMHA was inactive in both assays (lanes 6 and 10). This indicates that the trans reaction can occur without protein-primed initiation of reverse transcription.

FIG. 3.

The priming-deficient mutant DP-Y96F is active in the trans reaction. (A) 35S-labeled DP and DP-Y96F were translated in vitro in the presence of ɛ (lanes 1 to 3) and were employed in the priming reaction (lanes 4 to 6) or in a trans reaction with DRF+ (lanes 7 to 9). (B) The trans reaction is dependent on ɛ. DP was translated in vitro in the presence (lane 1) or absence (lane 2) of ɛ prior to use in the trans reaction. The translation and priming samples were resolved directly by SDS-PAGE, and the products of the trans reaction were purified and resolved on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The mobilities of the 89-kDa DP protein and the single-stranded RNA markers are indicated. Lane 10 contains 32P internally labeled DRF+ RNA.

DP was then translated in vitro in the presence or absence of ɛ and was used in a trans reaction (Fig. 3B). DP was active in the trans reaction when translated in the presence of ɛ, but was 7- to 11-fold less active when translated without ɛ. Therefore, the trans activity of the in vitro-translated DP was strongly stimulated by ɛ. The residual trans activity of DP in the absence of ɛ is reminiscent of the residual activity occasionally observed with DP in the priming assay (see Discussion).

The reverse transcriptase domain of the polymerase is altered upon binding to ɛ.

Binding to ɛ induces an alteration to the polymerase that is detected as increased resistance to proteolysis (18). Our model for the maturation of the polymerase predicts that this alteration would affect the reverse transcriptase domain of the polymerase in order to activate it. Therefore, the boundaries of the fragments of the polymerase protected from proteolysis were mapped. Figure 4 shows a diagram of the domains of the polymerase and the sites used to map the protected region.

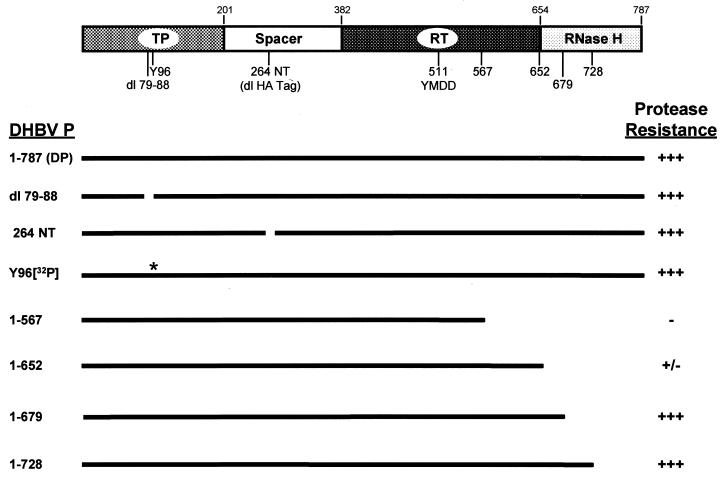

FIG. 4.

The ɛ-dependent protease-resistant fragments lie between amino acids 265 and approximately 652. A schematic diagram of the DHBV polymerase at the top shows the terminal protein (TP), spacer, reverse transcriptase (RT), and RNase H domains. The amino acid positions of the boundaries between the domains are indicated above the diagram, and the locations of the deletions and truncations are indicated below the diagram. The YMDD polymerase active-site motif is also shown. The identities of the DP derivatives are indicated to the left, and the black lines indicate sequences retained within the DP derivatives. The asterisk indicates the tyrosine-dGMP moiety in DP following the priming reaction. The degrees of protease resistance relative to that of the wild-type DP are indicated as follows: +++, 70 to 100%; ++, 10 to 70%; +, 1 to 10%; and −, no detectable activity.

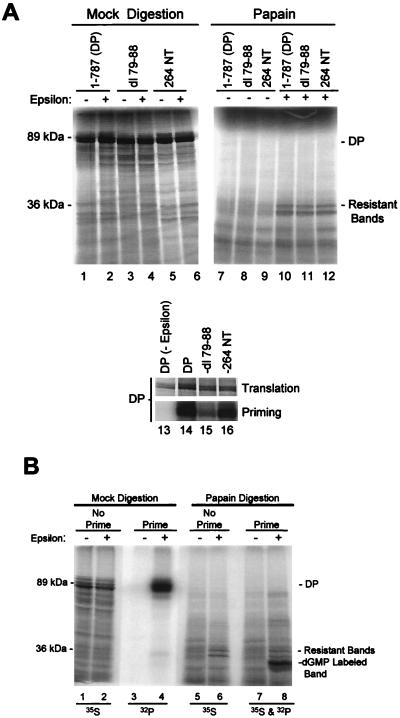

To determine the amino-terminal boundary of the fragment resistant to papain digestion, two in-frame deletions were introduced to DP. dl79-88 removed 10 amino acids within the terminal protein domain, and 264 NT removed the 11-amino-acid influenza virus hemagglutinin epitope tag found after amino acid 264 (within the spacer domain) in our standard DP construct. The deletion derivatives were translated in vitro with and without ɛ and were partially digested with papain, and the ɛ-dependent resistant fragments were compared to those from wild-type DP (Fig. 5A). ɛ protected a doublet of 36 and 34 kDa from digestion with papain instead of the single 36-kDa fragment observed previously (18). This doublet is observed with newer lots of reticulocyte lysate. The two resistant fragments come from the same region of the polymerase because the 36-kDa fragment is converted to the 34-kDa fragment upon further digestion (data not shown). Neither internal deletion of DP affected the mobilities of the resistant fragments (lanes 10 to 12), although the mobilities of the undigested proteins were altered (lanes 2, 4, and 6). Both deletion derivatives were enzymatically active in the priming assay (lanes 13 to 16). These data eliminate amino acids 1 to 264 from being within the resistant fragments, because the largest possible proteolytic fragment of DP in this region that would be unaffected by the two deletions is approximately 19 kDa.

FIG. 5.

Amino acids 1 to 264 are not within the ɛ-dependent papain-resistant fragments of DP. (A) 35S-labeled DP and the internal deletion derivatives dl79-88 and 264 NT were translated in vitro with or without ɛ (lanes 1 to 6) and were subjected to partial proteolysis with papain (lanes 7 to 12). The mobilities of the 89-kDa full-length DP and the 36-kDa resistant fragment are indicated. The DP proteins were also employed in a priming assay (lanes 13 to 16); translation samples detect the 35S-labeled DP, and priming samples detect 32P-dGMP incorporated during the priming reaction. (B) Tyrosine 96 is not within the papain- resistant fragments. DP was translated as described for panel A and employed in a priming assay. The samples were then split in half and subjected to mock digestion (lanes 1 to 4) or to partial proteolysis with papain (lanes 5 to 8). The mobilities of the 89-kDa full-length DP and the 36-kDa protected fragment are indicated, as is the mobility of the 32P-dGMP-labeled fragment in lane 8 containing Y96. The isotope detected in each lane is indicated at bottom.

The exclusion of the amino terminus of the polymerase from the resistant fragments was confirmed by using the priming assay to label tyrosine 96 with [32P]dGMP prior to partial proteolysis with papain. DP was translated in vitro, was allowed to prime DNA synthesis with [α-32P]dGTP, and was partially digested with papain prior to resolution of the products by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5B). The residual 32P-labeled fragment containing Y96 migrated more rapidly than did the 35S-labeled protected DP fragments, eliminating the possibility that amino acids 1 to 96 are within the protected fragments.

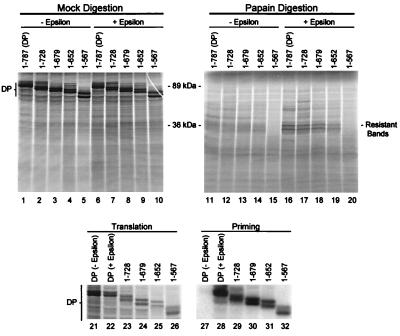

To map the carboxy-terminal boundary of protease resistant fragments, DP was translated from truncated mRNAs to produce derivatives terminating at amino acid 728, 679, 652, or 567. These truncated proteins were translated in the presence of ɛ and subjected to partial proteolysis with papain (Fig. 6). All of the truncated enzymes were active in the priming assays (lanes 21 to 32). Truncation of DP at amino acid 728 had no effect on the resistant fragments (lane 17). Truncation further to amino acid 679 did not affect the mobility of the resistant fragments but did slightly reduce the amount of the protected fragments (lane 18). Truncation to amino acid 652 nearly abolished protection of the fragments and may have slightly increased the mobility of the residual protected fragments (lane 19). Truncation further to amino acid 657 abolished the protected fragments (lane 20). These data indicate that amino acids 679 to 787 are not within the protected fragments and that the carboxy terminal boundary of the protected region is likely to be near amino acid 652.

FIG. 6.

The carboxy-terminal boundary of the ɛ-dependent papain-resistant fragment lies near amino acid 652. 35S-labeled DP and DP truncated at amino acid 728, 679, 652, or 657 were translated in vitro with or without ɛ (lanes 1 to 10) and were subjected to partial proteolysis with papain (lanes 11 to 20). The mobilities of the 89-kDa full-length DP and the 36-kDa protected fragment are indicated. DP derivatives were also employed in a priming assay (lanes 21 to 32) as described in the legend to Fig. 5.

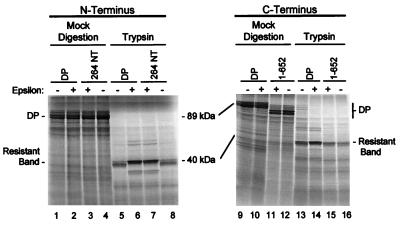

The mapping experiments were repeated with trypsin instead of papain to probe the structure of DP. Figure 7 shows partial proteolysis with trypsin of DP, DP-264 NT, and DP 1-652 (the derivatives that define the innermost boundaries of the protected fragment). The 40-kDa fragment of DP protected from trypsin digestion was affected in exactly the same manner by the modifications to the polymerase as was the 36-kDa fragment produced by papain digestion.

FIG. 7.

ɛ protects the same region of DP from digestion with trypsin as it does with papain. 35S-labeled DP, DP 264 NT, and DP truncated at amino acid 652 were translated in vitro with or without ɛ (lanes 1 to 4 and 9 to 12) and were subjected to partial proteolysis with trypsin (lanes 5 to 8 and 13 to 16). The mobilities of the 89-kDa full-length DP and the 40-kDa protected fragment are indicated.

Together, the mapping data summarized in Fig. 4 indicate that the region of the polymerase protected from partial proteolysis by papain and trypsin is essentially the same and that it lies between amino acids 265 and approximately 652. This leaves the carboxy-terminal half of the spacer domain and the reverse transcriptase domain as the potential constituents of the protected fragments.

Mutations to the polymerase support a role for ɛ in the maturation mechanism.

The correlation between the ability of the polymerase to adopt the ɛ-dependent protease resistant state and its development of enzymatic activity was originally established with wild-type polymerase and mutant ɛ RNAs. To expand this correlation, 15 mutations were introduced throughout the polymerase (Table 1). Following in vitro translation, the mutant polymerases were assayed for ɛ binding, adoption of the protease-resistant state, DNA priming, and the trans reaction (priming-independent DNA synthesis). The effects of these mutations on protein-primed reverse transcription by TYDP expressed in S. cerevisiae were also determined. Five patterns of activity were apparent from these experiments. In the first pattern, the polymerases possessed all activities (wild-type, F103Y/N104D, K153E, Y156H/D158L, N399D/T400A, D666N, T668V/T670V, H693Y, E696R/L698T, and D715V). In the second pattern, Y96F possessed ɛ-binding activity, protease resistance, and priming-independent DNA synthesis but could not perform DNA priming or priming-dependent DNA synthesis. In the third pattern, mutants R404E and YMHA (D513H/D514A) possessed ɛ-binding activity and protease resistance but showed no DNA priming or DNA synthesis activity. In the fourth pattern, K394L/K395I possessed ɛ-binding activity but exhibited reduced protease resistance and no DNA priming or DNA synthesis. In the final pattern, the mutants K182E/R183E and F391H/L392D exhibited no activity in any of the assays. These results support a role for ɛ in the maturation of the polymerase because the ability to adopt the ɛ-dependent protease-resistant state was a prerequisite for DNA priming and DNA synthesis in all cases.

DISCUSSION

The ɛ stem loop at the 5′ end of the hepadnavirus pregenomic RNA was first described as the primary element of the RNA packaging signal (6, 7, 11). It was subsequently found to be the origin of reverse transcription (10, 14, 19, 21). In the present paper, a third fundamental role for ɛ is demonstrated, i.e., that of an essential cofactor for the maturation of the polymerase to an enzymatically active form.

We had previously found that TYDP expressed in yeast could synthesize small amounts of DNA from exogenously added RNAs (the trans reaction [18] [Fig. 3B]). However, TYDP could perform this reaction only if it had been translated in the presence of ɛ. This was unexpected because ɛ was not a substrate in the reaction and ɛ was destroyed prior to the trans reaction.

The trans reaction has now been shown to be an authentic property of the DHBV polymerase. The trans reaction itself is template-dependent reverse transcription of the input RNA producing DNAs of heterogeneous lengths. Many of these products contain a small amount of RNA at their 5′ ends (Fig. 1 to 3) (18). This RNA is likely to result from RNA priming of the reaction, either through transient hybridization of two RNA molecules or by snap-back priming of a single RNA substrate molecule. The short length of the RNA portion of the chimera may imply that the RNA is degraded by an RNase following DNA synthesis. The putative RNase is likely to be of cellular origin, because a mutant DHBV polymerase lacking RNase H activity (D715V [24]) produces the same spectrum of trans products as does the wild-type polymerase (data not shown). Intriguingly, the products of the trans reaction with DRF+ RNA appear to be of both positive and negative polarity. Because the trans reaction is eliminated when the DHBV polymerase active site is mutated (Fig. 1, lanes 3, 5, and 7), synthesis of the first strand in the trans reaction must be by the viral polymerase. However, the mechanism of synthesis of the second strand is unknown. Because the second strand would be made by DNA-dependent DNA polymerization, it could be produced either by the viral polymerase or by the cellular DNA polymerases that are also present in the yeast VLP extracts, viral core preparations, and rabbit reticulocyte lysates.

This analysis of the trans reaction differs from the previous analysis (18) in two ways. First, the trans product was found to contain much more DNA than had been observed earlier. This discrepancy is due at least in part to improvements in the purification of the polymerases which have reduced the degradation of the substrate RNA during the reaction and have increased the efficiency of the trans reaction (unpublished observations). Second, the speculation that the trans reaction was a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-like reaction proved to be inaccurate because the reaction requires all four dNTPs and because the products hybridize specifically to substrate RNA sequences. This new evidence does not alter the earlier conclusions based on the trans reaction.

The importance of the trans reaction for the experiments reported here is that it allows us to measure DNA synthesis by the polymerase in the absence of protein-primed initiation of reverse transcription. This independence was first shown by the resistance of the trans product to extraction by phenol (18) (Fig. 1) and then genetically with the Y96F mutant (Fig. 3). Importantly, both wild-type DP and DP-Y96F (Fig. 3B and data not shown) show a strong dependence on a functional ɛ in the trans reaction. This directly demonstrates that the hepadnavirus polymerase can synthesize DNA without protein priming and yet still be strongly influenced by ɛ.

DHBV polymerase amino acids 265 to approximately 652 (essentially the reverse transcriptase domain) were shown to contain the polymerase fragments that are protected from proteolysis by papain and trypsin after binding to ɛ. This region is only slightly bigger than are the papain and trypsin fragments themselves (about 65 and 30 amino acids larger, respectively). Therefore, the fragments protected from both proteases must contain the YMDD polymerase active-site motif at amino acids 511 to 514. These data do not exclude ɛ-dependent alterations to other regions of the polymerase; however, there are no data for such changes at present.

The necessity for formation of the ɛ-dependent structural alteration to the polymerase prior to its development of DNA priming activity has now been shown by two independent approaches. Previously, we had demonstrated that the alteration was a prerequisite for the enzymatic activity of the wild-type polymerase by employing 14 mutant ɛ sequences (18). Here, this requirement is shown with 15 mutant polymerases and wild-type ɛ (Table 1). Consistent with the order of events in the proposed maturation mechanism, a mutant polymerase that bound to ɛ but was deficient in the subsequent stages of the mechanism (F391H/L392D) was found, and other mutants that were wild type for ɛ binding and adoption of the protease-resistant state but that could not progress further to synthesize DNA (R404E and D513H/D514A [YMHA]) were found. Truncation of the polymerase to amino acid 567 abolished the protease resistance of the polymerase, and yet the polymerase retained significant DNA priming activity (Fig. 6). This discrepancy is likely due to truncation of the polymerase far enough to expose papain and trypsin sites within the reverse transcriptase domain that are normally blocked by the deleted portion of the protein.

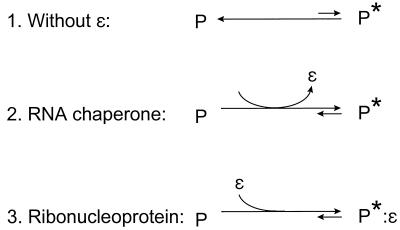

The data in the present article and its predecessor (18) support the hypothesis that the DHBV polymerase is translated in an inactive form (P) and that it must undergo a posttranslational structural alteration to become active (P*). The alteration to the polymerase is the essential feature of its maturation from P to P*, and under physiological conditions the alteration is induced by binding to ɛ. However, there may be other conditions under which the polymerase may progress to P* (18), because limited DNA synthesis has been observed by recombinant hepadnavirus polymerases in the absence of ɛ (9, 15, 22). P and P* are interconvertible, because the protease resistance that is the hallmark of P* is reversible upon removal of ɛ (18). Perhaps the two forms of the polymerase are in an equilibrium, with ɛ binding favoring the active form (Fig. 8, line 1). If there is an equilibrium between P and P*, the various recombinant systems may vary in their abilities to synthesize DNA in the absence of ɛ because their equilibrium points between the active and the inactive forms may differ slightly.

FIG. 8.

Posttranslational maturation of the DHBV polymerase. The polymerase is translated in an inactive state, P, and must undergo an alteration to reach its active state, P*.

The role of ɛ in the maturation of the polymerase to P* may be viewed in two ways. First, ɛ could be required transiently as an RNA chaperone that helps the polymerase mature properly and then dissociates from P* (Fig. 8, line 2). Alternatively, the interaction between the polymerase and ɛ could be required at all times to maintain P*. In this case, P* would be a ribonucleoprotein complex (Fig. 8, line 3). If the hepadnavirus polymerase proves to be a ribonucleoprotein complex, it would imply that there are two RNA binding sites on the protein, i.e., one for the template and one for ɛ as a structural element of the enzyme. A second copy of ɛ may be required in this case. If so, it would have to be provided either by a second copy of the pregenomic RNA within the viral cores or by the 3′ copy of ɛ in the pregenomic RNA. Further studies will be required to establish the full extent of the ɛ-polymerase interaction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Chaomei Liu, Melissa Stevens, and Babatunde Adeyemo for technical assistance and to Michael Green for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH grant AI38447, American Cancer Society grant JFRA-616, and a Young Investigator Matching Grant from the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartenschlager R, Junker-Niepmann M, Schaller H. The P gene product of hepatitis B virus is required as a structural component for genomic RNA encapsidation. J Virol. 1990;64:5324–5332. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5324-5332.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Church G M, Gilbert W. Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1991–1995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganem D. Hepadnaviridae and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, Chanock R M, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, Straus S E, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2703–2737. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerlich W H, Robinson W S. Hepatitis B virus contains protein attached to the 5′ terminus of its complete DNA strand. Cell. 1980;21:801–809. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90443-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch R C, Lavine J E, Chang L J, Varmus H E, Ganem D. Polymerase gene products of hepatitis B viruses are required for genomic RNA packaging as well as for reverse transcription. Nature. 1990;344:552–555. doi: 10.1038/344552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch R C, Loeb D D, Pollack J R, Ganem D. cis-acting sequences required for encapsidation of duck hepatitis B virus pregenomic RNA. J Virol. 1991;65:3309–3316. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3309-3316.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Junker-Niepmann M, Bartenschlager R, Schaller H. A short cis-acting sequence is required for hepatitis B virus pregenome encapsidation and sufficient for packaging of foreign RNA. EMBO J. 1990;9:3389–3396. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolodziej P A, Young R A. Epitope tagging and protein surveillance. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:508–519. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94038-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanford R E, Notvall L, Lee H, Beams B. Transcomplementation of nucleotide priming and reverse transcription between independently expressed TP and RT domains of the hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase. J Virol. 1997;71:2996–3004. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2996-3004.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nassal M, Rieger A. A bulged region of the hepatitis B virus RNA encapsidation signal contains the replication origin for discontinuous first-strand DNA synthesis. J Virol. 1996;70:2764–2773. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2764-2773.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollack J R, Ganem D. An RNA stem-loop structure directs hepatitis B virus genomic RNA encapsidation. J Virol. 1993;67:3254–3263. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3254-3263.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollack J R, Ganem D. Site-specific RNA binding by a hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase initiates two distinct reactions: RNA packaging and DNA synthesis. J Virol. 1994;68:5579–5587. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5579-5587.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radziwill G, Zentgraf H, Schaller H, Bosch V. The duck hepatitis B virus DNA polymerase is tightly associated with the viral core structure and unable to switch to an exogenous template. Virology. 1988;163:123–132. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rieger A, Nassal M. Specific hepatitis B virus minus-strand DNA synthesis requires only the 5′ encapsidation signal and the 3′-proximal direct repeat DR1*. J Virol. 1996;70:585–589. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.585-589.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seifer M, Standring D N. Recombinant human hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase is active in the absence of the nucleocapsid or the viral replication origin, DR1. J Virol. 1993;67:4513–4520. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4513-4520.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tavis J E, Ganem D. Expression of functional hepatitis B virus polymerase in yeast reveals it to be the sole viral protein required for correct initiation of reverse transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4107–4111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tavis J E, Ganem D. RNA sequences controlling the initiation and transfer of duck hepatitis B virus minus-strand DNA. J Virol. 1995;69:4283–4291. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4283-4291.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tavis J E, Ganem D. Evidence for the activation of the hepatitis B virus polymerase by binding of its RNA template. J Virol. 1996;70:5741–5750. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5741-5750.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tavis J E, Perri S, Ganem D. Hepadnavirus reverse transcription initiates within the stem-loop of the RNA packaging signal and employs a novel strand transfer. J Virol. 1994;68:3536–3543. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3536-3543.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang G-H, Seeger C. The reverse transcriptase of hepatitis B virus acts as a protein primer for viral DNA synthesis. Cell. 1992;71:663–670. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90599-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang G-H, Seeger C. Novel mechanism for reverse transcription in hepatitis B viruses. J Virol. 1993;67:6507–6512. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6507-6512.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang G-H, Zoulim F, Leber E H, Kitson J, Seeger C. Role of RNA in enzymatic activity of the reverse transcriptase of hepatitis B viruses. J Virol. 1994;68:8437–8442. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8437-8442.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weber M, Bronsema V, Bartos H, Bosserhoff A, Bartenschlager R, Schaller H. Hepadnavirus P protein utilizes a tyrosine residue in the TP domain to prime reverse transcription. J Virol. 1994;68:2994–2999. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2994-2999.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei Y, Tavis J E, Ganem D. Relationship between viral DNA synthesis and virion envelopment in hepatitis B viruses. J Virol. 1996;70:6455–6458. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6455-6458.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zoulim F, Seeger C. Reverse transcription in hepatitis B viruses is primed by a tyrosine residue of the polymerase. J Virol. 1994;68:6–13. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.6-13.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]