Introduction

Suprachoroidal haemorrhage (SCH) denotes a pathological entity characterised by the pathologic accumulation of blood within the suprachoroidal space, a virtual compartment between the choroid and the sclera. SCH occurrence, while relatively infrequent, carries substantial clinical significance, and it may develop spontaneously, during or after ophthalmic surgical procedures, or as a sequel to ocular trauma. In the event that postoperative SCH remains undetected and untreated, it can lead to profound visual impairment, potentially culminating in complete vision loss or blindness 1 , 2 , 3 . It occurs when the vortical veins or the long and/or short ciliary arteries rupture, and its most significant risk factor is hypotony, or the sudden intraocular pressure drops during or after ophthalmic surgery 4 , 5 . SCH has also been reported subsequent to ocular trauma, or spontaneously in patients harbouring specific ocular or systemic predisposing risk factors, such as advanced age, atherosclerosis, vascular disease, arterial hypertension, anticoagulation therapy, chronic kidney disease, aphakia, age-related macular degeneration, myopia, and glaucoma 6 7 8 9 10 11 .

In the majority of spontaneous cases documented in the literature, patients exhibited a predisposition to haemorrhagic events due to underlying inherited blood dyscrasia or a history of systemic antithrombotic therapy usage, including antiplatelet, anticoagulation, or thrombolytic agents 3 , 12 , 13 .

The aim of this report is to present the case of a patient who developed bilateral spontaneous suprachoroidal haemorrhage (SSCH) following a Valsalva manoeuvre, without a preexisting inherited bleeding disorder or the use of an antithrombotic agent, and no other known ocular condition predisposing to choroidal bleeding. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that a bilateral SSCH following a Valsalva manoeuvre has been reported.

This report followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Case Presentation

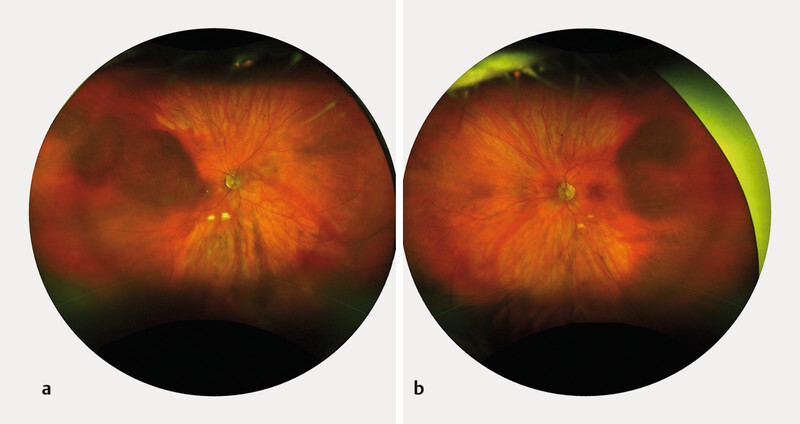

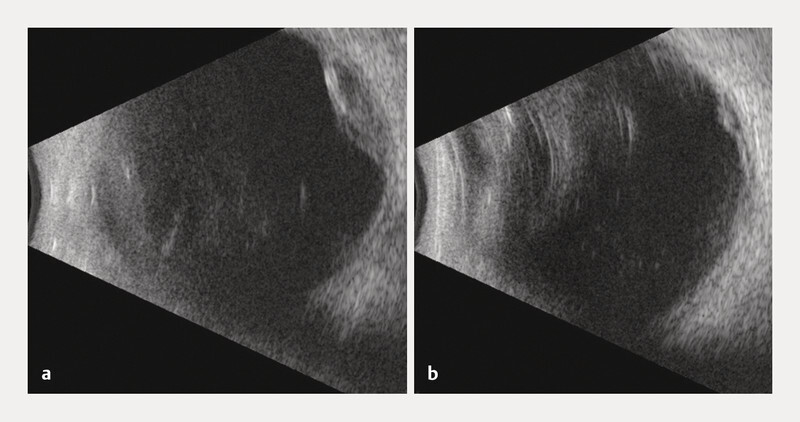

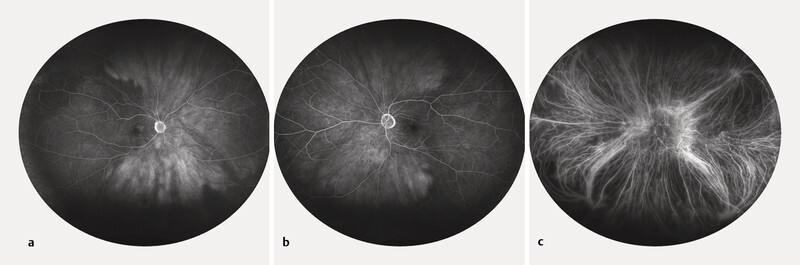

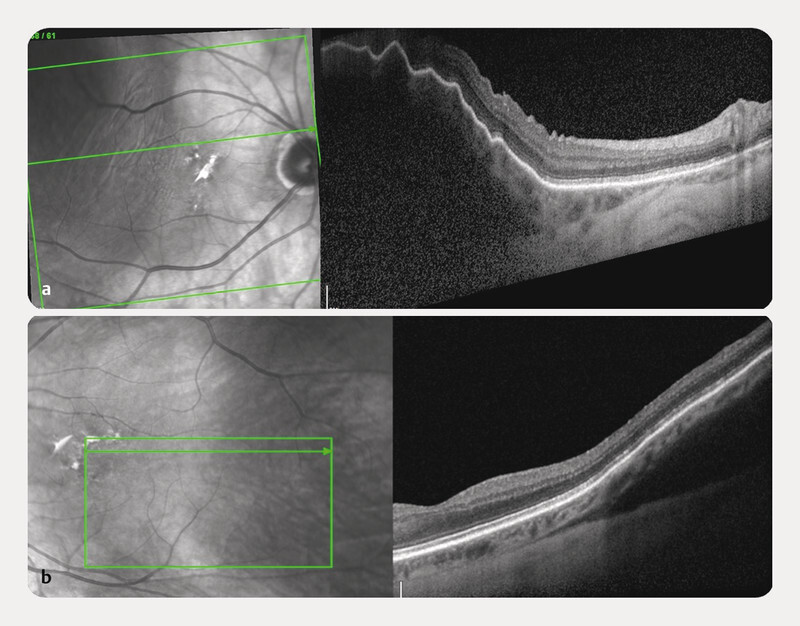

A 75-year-old Caucasian female was referred to our ophthalmology department because a bilateral hyperdense mass in both eyeballs was revealed on a head CT scan. The patient reported blurred vision in the right eye since the previous night, following a Valsalva manoeuvre because of intense vomiting due to alcohol consumption. She was known to be mildly myopic for both eyes, with no relevant ophthalmic history, except for bilateral cataract surgery several years before. General history revealed treated and well-controlled hypertension. There was no history of clotting disorders, nor anticoagulation medication. Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 for both eyes. The slit lamp examination of the anterior segment was unremarkable. However, the dilated fundoscopy revealed a bilateral posterior red-brown mass in the upper-temporal quadrant ( Fig. 1 ). The B-scan ultrasonography examination revealed those masses to be isoechogenic and into the choroid structure, with a thickness of 3.5 mm for the right eye and 1.5 for the left eye without any sign of choroidal excavation ( Fig. 2 ). Those lesions remained unrevealed through fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography ( Fig. 3 ). Thanks to enhanced depth imaging spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) scans, the lesions were located in the suprachoroidal space. Even if not involving the macular region, the right eye lesion showed retinal folds in the foveal region ( Fig. 4 ). The clinical presentation, the aspect of the B-scan ultrasonography, and SD-OCT, as well as the absence of any identifiable systemic aetiology led to the diagnosis of Valsalva-induced bilateral SSCH. Given the fact that visual acuity was preserved in both eyes, we closely followed up with the patient without any intervention. The workup for blood clotting disorders returned negative. One week after the first evaluation, the patient was asymptomatic and the suprachoroidal haemorrhages in both eyes were diminishing.

Fig. 1.

Fundus photography of the RE ( a ) and LE ( b ) revealing a bilateral posterior red-brown choroidal mass in the upper temporal quadrant.

Fig. 2.

B-scan ultrasonography showing an isoechogenic mass of 3.5 mm thickness of the RE ( a ) and 1.5 mm for the LE ( b ).

Fig. 3.

Fluorescein angiography of the RE ( a ) and LE ( b ) showing an attenuated visualisation of the choroidal perfusion; indocyanine green angiography of the LE ( c ) within normal limits.

Fig. 4.

SD-OCT of the RE ( a ) and LE ( b ). The lesions are located in the suprachoroidal space.

Discussion

SSCH is an infrequent condition, characterised by an unfavourable visual prognosis 8 , 11 . Literature is scarce of reports presenting SSCH development in patients with no predisposing systemic or ocular conditions, and very few of them with bilateral involvement 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 .

The Valsalva manoeuvre is an established cause of intraretinal and preretinal haemorrhage, but the association with SCH has been rarely reported, and never bilateral 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 . It induces a rapid increase in intrathoracic or intra-abdominal pressure while the glottis remains closed. Due to the absence of valves within the venous system, this elevated pressure is transferred to the eye, leading to the rupture of vessel walls, probably due to an excessive pressure gradient acting across the vessel wall 18 , 25 . The causal relationship between the Valsalva manoeuvre subsequent to emesis resulting from alcohol ingestion and the onset of bilateral SSCH in our patient remains uncertain. We postulate that our patient might have harboured preexisting choroidal anomalies associated with her advanced age and/or vascular pathology, which could have contributed to the development of bilateral SSCH subsequent to emesis. However, our patientʼs presentation is particularly unusual due to the absence of ocular risk factors or recent previous ophthalmic surgery.

SCH after a Valsalva manoeuvre has been previously reported in patients either on systemic anti-coagulants, or in eyes with previous ocular surgery, such as scleral buckling 19 , 21 , 23 , 26 . Valsalva-induced SSCH has also been reported to be associated with certain ophthalmic risk factors such as high myopia and age-related macular degeneration 20 , 22 .

Very few cases have been described in association with Valsalva manoeuvres with no underlying or associated systemic or ophthalmological conditions. In 2003, Hammam and Madhavan described the case of a 65-year-old man who suffered from a unilateral small choroidal haemorrhage caused by the Valsalva manoeuvre that resulted in a sudden increase in intraocular pressure and subsequent corneal oedema. The patient had no history of ocular or bleeding disorder, and a routine coagulation screening test was within normal limits. The correct diagnosis was revelled thanks to ultrasound, and a total resolution of the SCH was detected at 2 weeks 18 . Similar to our case, Castro Flórez and colleagues recently published the case of a 70-year-old woman with a unilateral SCH after a Valsalva manoeuvre during defecation. The patient had no ophthalmological or personal history of interest except for arterial hypertension under treatment, and the lesions completely resolved in 12 weeks 24 .

Our findings demonstrate that the enhanced depth imaging SD-OCT improves the visualisation of the choroid due to its greater penetrance. Also, it offers adequate axial resolution to discern tissue layers on the inner boundary of the haemorrhage, as well as sufficient penetration capability through the blood collection for imaging the inner aspect of the sclera and definitively localising the haemorrhage within the suprachoroidal space. However, when it came to our patientʼs left eye, where the SCH was located in the peripheral fundus, SD-OCT images proved less effective for localising the lesion. In such situations, ultrasound emerged as a more versatile diagnostic tool.

The differential diagnosis of SCH presents a significant challenge in numerous cases, frequently leading to confusion with choroidal tumours. An analysis of 12 000 patients referred to an eye oncology unit over a 25-year period with an initial diagnosis of choroidal melanoma revealed that 29 cases (0.24%) were ultimately found to be choroidal haemorrhages 27 . There are certain clinical characteristics that can help to differentiate a haemorrhage from a choroidal tumour, such as the presence of choroidal folds, absence of drusen, absence of lipofuscin, and a more reddish colour 24 . The images acquired through EDI-OCT play a crucial role in the process of distinguishing between SCH and potential tumours, such as small choroidal melanomas or metastases, in the differential diagnosis 28 , 29 . In the case of SCH, the choroidal tissue shows an anterior displacement but retains its normal thickness and appearance, which contrasts with the situation in a choroidal tumour, where the choriocapillaris is compressed and challenging to visualise. Moreover, the elevated surface of SCH has an irregular appearance, which could be due to the retraction of the clot 28 . On the other side, choroidal melanomas typically exhibit a smooth and uniform surface, whereas in the case of choroidal metastases, the anterior contour can sometimes appear irregular, manifesting as a bumpy or lumpy texture 24 . Other important differential diagnoses are choroidal detachment and peripheral exudative haemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR), where the presence of a choroidal neovascular membrane typical of the PEHCR.

In conclusion, this case report shows a rare finding of bilateral SSCH induced by the Valsalva manoeuvre. This atypical presentation, and the fact that it was bilateral, has an important clinical relevance in order to make clinicians aware of the possibility of these findings, with the goal to prevent erroneous diagnosis and unnecessary treatments. Ultimately, employing multimodal retinal imaging proves to be a valuable instrument for steering toward an accurate diagnosis.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mohan S, Sadeghi E, Mohan M et al. Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage. Ophthalmologica. 2023 doi: 10.1159/000533937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sukpen I, Stewart J M. Acute Intraoperative Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage During Small-Gauge Pars Plana Vitrectomy. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2018;12 1:S9–S11. doi: 10.1097/icb.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu T G, Green R L. Suprachoroidal hemorrhage. Surv Ophthalmol. 1999;43:471–486. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(99)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang H, Gao Y, Fu W et al. Risk Factors and Treatments of Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:6.539917E6. doi: 10.1155/2022/6539917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 5.Oliver-Gutierrez D, Martin Nalda S, Segura-Duch G et al. Delayed suprachoroidal hemorrhage after Descemet Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSAEK) Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol (Engl Ed) 2023;98:355–359. doi: 10.1016/j.oftale.2023.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shan H, Wu X, Guo H. Spontaneous suprachoroidal and orbital hemorrhage in an older woman associated with prophylactic antiplatelet therapy: A case report and literature review. Heliyon. 2022;8:e11511. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azimi A, Abdollahi F, Sadeghi E et al. Epidemiological and Clinical Features of Pediatric Open Globe Injuries: A Report from Southern Iran. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2023;18:88–96. doi: 10.18502/jovr.v18i1.12729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akkan Aydoğmuş F S, Serdar K, Kalayci D et al. Spontaneous Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage Associated with Iatrogenic Coagulopathy. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2019;13:174–175. doi: 10.1097/icb.0000000000000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandra A, Barsam A, Hugkulstone C. A spontaneous suprachoroidal haemorrhage: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:185. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y Y, Chen Y Y, Sheu S J. Spontaneous suprachoroidal hemorrhage associated with age-related macular degeneration and anticoagulation therapy. J Chin Med Assoc. 2009;72:385–387. doi: 10.1016/s1726-4901(09)70393-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srikanth K, Kumar M A. Spontaneous expulsive suprachoroidal hemorrhage caused by decompensated liver disease. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61:78–79. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.107201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saatci A O, Kuvaki B, Oner F H et al. Bilateral massive choroidal hemorrhage secondary to Glanzmannʼs syndrome. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2002;33:148–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang S S, Fu A D, McDonald H R et al. Massive spontaneous choroidal hemorrhage. Retina. 2003;23:139–144. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200304000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collon S, Teske M, Simonett J. Bilateral Spontaneous Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage after Systemic Tissue Plasminogen Activator. Ophthalmol Retina. 2022;6:519. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2022.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvá-Palomeque T, Ruiz-Casas D, Alonso-Formento N. Bilateral spontaneous suprachoroidal hemorrhage in a patient taking a low-molecular-weight-heparin. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol (Engl Ed) 2021;96:615–617. doi: 10.1016/j.oftale.2020.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haridas A, Litwin A S, Coker T. Perioperative spontaneous bilateral suprachoroidal hemorrhage. Digit J Ophthalmol. 2011;17:9–11. doi: 10.5693/djo.02.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheung A Y, David J A, Ober M D. Spontaneous Bilateral Hemorrhagic Choroidal Detachments Associated with Malignant Hypertension. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2017;11:175–179. doi: 10.1097/icb.0000000000000322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammam T, Madhavan C. Spontaneous suprachoroidal haemorrhage following a valsalva manoeuvre. Eye (Lond) 2003;17:261–262. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Meurs J C, van den Bosch W A. Suprachoroidal hemorrhage following a Valsalva maneuver. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:1025–1026. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090080021008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zahid S, Dansingani K K, Fisher Y. Optical Coherence Tomography Evaluation of Valsalva-Induced Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2016;47:674–676. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20160707-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollack A L, McDonald H R, Ai E et al. Massive suprachoroidal hemorrhage during pars plana vitrectomy associated with Valsalva maneuver. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:383–387. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsiao S F, Shih M H, Huang F C. Spontaneous suprachoroidal hemorrhage: Case report and review of the literature. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2016;6:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tjo.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bijon J, Schalenbourg A. Valsalva-Induced Spontaneous Suprachoroidal Hemorrhage: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2022;239:559–564. doi: 10.1055/a-1785-4912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castro Flórez R, Azpitarte C, Arcos Villegas G et al. Suprachoroidal hemorrhage due to Valsalva maneuver, importance of enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography in differential diagnosis. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol (Engl Ed) 2021;96:442–445. doi: 10.1016/j.oftale.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers S M, Foster R E. Choroidal hemorrhage after Valsalvaʼs maneuver in eyes with a previous scleral buckle. Ophthalmic Surg. 1995;26:216–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexandrakis G, Chaudhry N A, Liggett P E et al. Spontaneous suprachoroidal hemorrhage in age-related macular degeneration presenting as angle-closure glaucoma. Retina. 1998;18:485–486. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199805000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shields J A, Mashayekhi A, Ra S et al. Pseudomelanomas of the posterior uveal tract: the 2006 Taylor R. Smith Lecture. Retina. 2005;25:767–771. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200509000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fung A T, Fulco E M, Shields C L et al. Choroidal hemorrhage simulating choroidal melanoma. Retina. 2013;33:1726–1728. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31828dac9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shields C L, Pellegrini M, Ferenczy S R et al. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography of intraocular tumors: from placid to seasick to rock and rolling topography–the 2013 Francesco Orzalesi Lecture. Retina. 2014;34:1495–1512. doi: 10.1097/iae.0000000000000288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]