Abstract

The rates of mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), progression to AIDS following HIV-1 infection, and AIDS-associated mortality are all inversely correlated with serum vitamin A levels (R. D. Semba, W. T. Caiaffa, N. M. H. Graham, S. Cohn, and D. Vlahov, J. Infect. Dis. 171:1196–1202, 1995; R. D. Semba, N. M. H. Graham, W. T. Caiaffa, J. B. Margolik, L. Clement, and D. Vlahov, Arch. Intern. Med. 153:2149–2154, 1993; R. D. Semba, P. G. Miotti, J. D. Chiphangwi, A. J. Saah, J. K. Canner, G. A. Dallabetta, and D. R. Hoover, Lancet 343:1593–1596, 1994). Here we show that physiological concentrations of vitamin A, as retinol or as its metabolite, all-trans retinoic acid, repressed HIV-1Ba-L replication in monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs). Repression required retinoid treatment of peripheral monocytes during their in vitro differentiation into MDMs. Retinoids had no repressive effect if they were added after virus infection. Retinol, as well as all-trans retinoic acid and 9-cis retinoic acid, also repressed HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR)-directed expression up to 200-fold in transfected THP-1 monocytes. Analysis of HIV-1 LTR deletion mutants demonstrated that retinoids were able to repress activation of HIV-1 expression by both NF-κB and Tat. A cis-acting sequence required for retinoid-mediated repression of HIV-1 transcription was localized between nucleotides −51 and +12 of the HIV-1 LTR within the core promoter. Protein-DNA cross-linking experiments identified four proteins specific to retinoid-treated cells that bound to the core promoter. We conclude that retinoids render macrophages resistant to virus replication by modulating the interaction of cellular transcription factors with the viral core promoter.

Vitamin A is involved in a wide variety of normal processes, including immunity, differentiation, growth, reproduction, and vision (19, 32). The main dietary sources of vitamin A, retinol and the provitamin β-carotene, are converted to a number of bioactive derivatives, including, among others, all-trans retinoic acid (RA) and 9-cis RA (9cRA). Cellular effects of these metabolites are mediated by nuclear receptors, which are ligand-dependent transcription factors (17–19, 37). Two families of retinoid receptors have been identified. The RA receptors (RARα, RARβ, and RARγ) bind to and are activated by both RA and 9cRA. The retinoid X receptors (RXRα, RXRβ, and RXRγ) bind only 9cRA. Recent experiments have shown that RAR binds DNA as a heterodimer with RXR and activates transcription following ligand binding (18). Ligand-associated RXRs are thought to bind DNA either as homodimers or as heterodimers in association with RARs and other members of the steroid-thyroid hormone receptor family.

Several properties of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-induced disease are inversely correlated with a person’s serum vitamin A level. Semba et al. (35) found that the rates of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 were increased over fourfold in women who were vitamin A deficient and that vitamin A deficiency was associated with a fourfold increase in risk of death in HIV-1-positive individuals (33, 34). Moreover, levels of dietary vitamin A have been shown to influence progression to AIDS (39), and supplementation can decrease HIV-1-associated morbidity in children (7). The association between vitamin A and HIV-1 disease progression cannot be attributed simply to overall malnutrition. In a study correcting for other factors, including energy intake, Tang et al. (39) still found that vitamin A deficiency held an elevated risk for AIDS mortality. Underscoring the complex nature of the relationship between vitamin A status and disease, these authors also found that a vitamin A intake of >20,000 IU/day increased the relative risk of AIDS mortality (39). This relationship between vitamin A status and disease is further complicated by the observation that AIDS patients are compromised in their ability to maintain vitamin A homeostasis (6, 12, 28).

The effect of vitamin A on HIV-1 disease could reflect either a direct effect of retinoids on virus gene expression or a general effect on immune function (32). Vitamin A has profound effects on hematopoeisis and is required for differentiation of cells of the myeloid lineage (24, 40, 42). Retinoids have also been shown to regulate HIV-1 gene expression in myeloid cells. We and others have shown that vitamin A directly modulates HIV-1 replication in myeloid cells (20, 30, 41, 43, 44). Pretreatment of the promonocytic cell line U937 with RA activated both HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus from rhesus macaques (SIVmac) long terminal repeat (LTR)-directed transcription approximately threefold by itself and up to 300-fold in synergy with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (20). The cis-acting sequences required for this synergistic activation were localized between nucleotides −50 and +1 of the SIVmac promoter and −83 and +80 of the HIV-1 promoter. Activation required greater than 4 days of RA pretreatment. This lag, along with the demonstration that RA altered the pattern of proteins bound to −50 through +1 of the SIVmac LTR, indicated that RA was modulating the expression of cellular factors.

Poli et al. (30) have shown that RA treatment stimulated HIV-1 replication in acutely infected U937 cells. Paradoxically, RA treatment of chronically infected U937 cells repressed PMA, interleukin-6, or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor activation of HIV-1 (30, 44). The opposite responses of acutely versus chronically infected cells to RA might reflect the differentiation state of these cells. HIV-1 infection induces U937 promonocytic cells to differentiate to a more mature monocyte-like state (27, 29). If the response to RA proved to depend on the differentiation state of the infected cell, then in vivo, vitamin A should have therapeutic potential, since macrophages are the predominant myeloid cell type infected by HIV-1. Consistent with this prediction, RA inhibited HIV-1 replication in alveolar macrophages (44), and in monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) (30). In the latter case the RA effects were donor dependent.

In an effort to resolve these discrepancies and establish the anti-HIV-1 therapeutic potential of vitamin A, we have started to delineate the molecular mechanisms responsible for retinoid-mediated effects on HIV-1 gene expression. We show that physiological concentrations of either retinol, RA, or 9cRA repress HIV-1 LTR-directed expression in the THP-1 monocytic cell line. These retinoids prevented transactivation of the HIV-1 LTR by both NF-κB and the viral protein Tat, reducing LTR-directed expression up to 200-fold. The cis-acting sequences required for repression are contained within the viral core promoter. Repression required retinoid pretreatment of the cells and was associated with a change in the pattern of cellular factors which bound to the core promoter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Monocyte isolation and culture.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were purified from healthy volunteers by Ficoll gradient centrifugation. PBMCs were suspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 0.29 mg of l-glutamine/ml, 50 U of penicillin/ml, 50 μg of streptomycin/ml, 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 10% pooled human AB serum. The serum stocks contained less than 0.3 endotoxin units per ml. All other reagents were endotoxin free. The cells were cultured overnight, after which nonadherent cells were removed, and adherent cells were cultured for an additional 4 days before virus infection. The cultures were infected with HIV-1Ba-L (3,000 ng of p24/5 × 105 cells) and maintained in medium without human serum. Virus replication was quantified either by measuring extracellular reverse transcriptase activity (9) or by p24 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Coulter). When indicated, retinoids were added from concentrated stocks (in ethanol) daily, beginning at the time of isolation of adherent PBMCs and continuing throughout the experiment. Cells not treated with retinoids received 0.01% ethanol to control for solvent effects.

THP-1 monocytes were grown in RPMI 1640 containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 0.29 mg of l-glutamine/ml, 50 U of penicillin/ml, 50 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 10% FBS. They were treated with retinoids as described above.

Plasmids.

PCR was used to isolate different regions of the HIV-1 LTR from HIV-1LAV-1. These fragments were inserted upstream from the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene and simian virus 40 polyadenylation sequences and cloned into pSP72 (Promega). p(−139/+84)CAT includes the binding sites for the cellular transcription factors NF-κB and Sp1 as well as the general transcription factor, TFIID. It also encodes TAR, the binding site for Tat. p(−86/+84)CAT includes the binding sites for Sp1 and TFIID and encodes TAR. p(−51/+84)CAT includes the binding site for TFIID and encodes TAR. p(−86/+12)CAT includes the binding sites for Sp1 and TFIID but does not encode TAR.

pCMVCAT was constructed by inserting the CAT gene downstream from the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early promoter in the vector pCMV5 (2). pCMVcTat contains a cDNA including both coding exons of HIV-1 Tat under the transcriptional control of the CMV immediate-early promoter (36).

Transfections and CAT assays.

Mid-log-phase THP-1 monocytes were washed, suspended in RPMI 1640 (room temperature), and transfected by electroporation at settings of 300 V and 1,160 μF. Transfections included 8 μg of either an LTR-CAT or CMV-CAT reporter per 107 cells. Some transfections also included 4 μg of pCMVcTat. Those transfections not including pCMVcTat contained pCMV5 instead in order to maintain a constant amount of DNA in each transfection. In some experiments, one-half of the transfected cells were treated with 50 nM PMA. Retinoid treatments were continued in those cultures that were initially pretreated with retinoids. Cellular extracts were prepared from the transfected cells after 20 h and assayed for CAT activity as previously described (20).

Flow cytometric analysis.

THP-1 monocytes were washed two times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS (107 cells/ml). MDMs were detached from tissue culture plates by incubating them in RPMI 1640 containing 5% FBS and 10 mM EDTA. The detached MDMs were washed two times with PBS and resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS (5 × 106 cells/ml.) The washed cells were stained by incubation for 30 min at 4°C with either anti-CD11b (fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]), anti-CD11c (FITC), anti-CD14 (FITC), or anti-CD33 (phycoerythrin). The cells were washed two times with PBS and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde. A minimum of 10,000 cells were analyzed for each sample with a Becton Dickinson fluorescence-activated cell sorter. The percentage of positive cells was calculated in comparison to isotype control stained cells.

Electrophoretic mobility shift and protein-DNA cross-linking assays.

Cellular extracts and radiolabeled probes were prepared as described previously (20). Mobility shifts were performed with 15 μg of cellular extract and 0.35 ng of probe (approximately 30,000 cpm).

Radiolabeled, bromodeoxyuridine-substituted probes were synthesized by PCR with Taq polymerase and the HIV-1LAV-1 LTR as a template. The amplifications were performed in Taq buffer containing 250 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP, 50 μM bromodeoxyuridine, 50 μM dATP, 50 μM dGTP, and 5 μM dCTP. The labeled probe (105 cpm; ∼0.25 ng) was incubated with 10 μg of cellular extract under standard gel shift conditions (20), and the reactions mixtures were spotted onto plastic wrap over an UV light transilluminator (312 nm) at 4°C. The samples were cross-linked for 3 min, and then CaCl2 and MgCl2 were added to 5 mM each. The samples were digested with DNase I (10 U; 37°C, 20 min). The resultant radiolabeled proteins were resolved on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-containing 6% polyacrylamide gels.

RESULTS

Retinoic acid represses HIV-1 expression in THP-1 monocytes.

We previously reported that all-trans retinoic acid and PMA synergistically activated HIV-1 expression in the promonocytic cell line U937. In agreement with these results, Poli et al. (30) reported that RA activated HIV-1 in acutely infected U937 cells but repressed HIV-1 replication in chronically infected U937 cells. Because HIV-1 induces U937 cells to differentiate to a more monocyte-like phenotype (27, 29) we reasoned that the different effects of RA might be related to the differentiation state of the cell. To test this, we transfected either untreated or RA-pretreated THP-1 monocytes (10−7 M; 4 days) with a biologically active provirus clone, pHIV-1NL4-3 (1). Untreated, transfected cells transiently produced HIV-1, as determined by p24 antigen capture ELISA. After 3 days cell-free supernatants contained over 300 pg of p24/ml. Treatment of THP-1 cells with RA for 4 days prior to transfection repressed virus expression to the extent that no p24 was detected (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Repression of HIV-1 p24 antigen production in all-trans retinoic acid-pretreated THP-1 cellsa

| Treatment | p24 antigen expression (pg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Untransfected control | 24 h posttransfection | 72 h posttransfection | |

| Untreated | Below detection | 293 | 346 |

| Retinoic acid | Below detection | Below detection | |

Both untreated and RA-treated (10−7 M; 4 days) THP-1 monocytes were transfected with pHIV-1NL4-3, a plasmid containing a full-length biologically active HIV-1 provirus. Transient expression of HIV-1 p24 antigen was measured by ELISA (Coulter) in cell-free supernatants collected either 24 or 72 h after transfection. The limit of detection in this assay is 7.5 pg/ml. The data shown are the averages of two independent transfections.

Physiological concentrations of retinoids repress HIV-1 replication in MDMs.

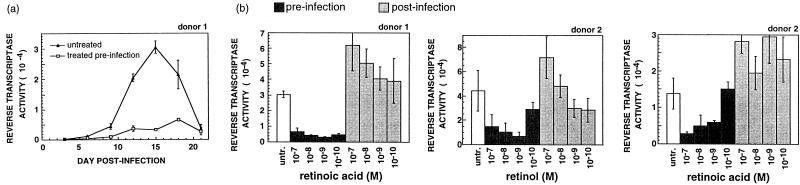

We next determined whether retinoids could repress HIV-1 replication in primary MDMs. MDMs were prepared from PBMCs by overnight adherence to plastic and were grown either with or without RA for four additional days prior to infection with HIV-1Ba-L. At 3-day intervals virus levels were quantified by assaying reverse transcriptase activity in the culture medium. In untreated cultures, reverse transcriptase was detected after 3 days, increased to peak levels at 15 days, and thereafter decreased. The decrease was associated with extensive cell death. RA pretreatment delayed the appearance of virus typically until days 6 to 9 and repressed total virus production at all time points (Fig. 1a). Moreover, there were no signs of cell death in the RA-treated cultures. In additional experiments we found that both RA and its precursor, retinol, showed antiviral activity over a wide range of concentrations, including those expected to correspond to plasma levels found in healthy individuals (Fig. 1b). However, in all cases retinoids had antiviral effects only when cells were pretreated. When added postinfection, retinoids failed to repress virus replication and in some instances slightly augmented replication.

FIG. 1.

Retinol and RA repress HIV-1 replication in MDMs. MDMs were grown either with or without retinoids for 5 days and then infected with HIV-1Ba-L, a macrophage-tropic virus isolate. After infection, retinoid treatments were continued in those cultures that were pretreated and begun in other cultures that were previously untreated (post-infection). Some cultures were left untreated and served as controls. (a) Virus production in untreated and RA-pretreated (10−9 M) MDMs was measured as cell-free reverse transcriptase activity. Each time point represents the average (± standard deviation) of three independent infections. (b) Levels of virus production 15 days after infection. Each sample represents the average (± standard deviation) of three independent infections. untr., untreated.

Retinoids repress HIV-1 LTR-directed expression in THP-1 monocytes.

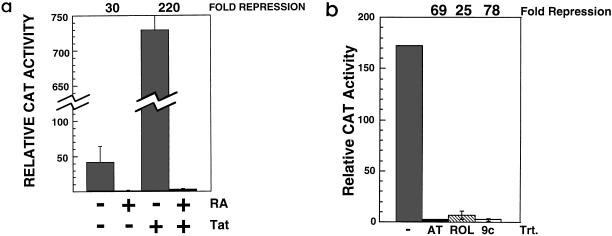

To determine if the antiviral activity of retinoids resulted from repressed transcription from the HIV-1 LTR, we examined the transient expression of HIV-1 LTR-CAT reporter plasmids in transfected THP-1 cells. When THP-1 cells were pretreated with RA for 4 days prior to transfection, Tat-activated expression was repressed more than 200-fold (Fig. 2a). Repression of LTR-directed expression was also seen when cells were pretreated for 4 days with either retinol or 9cRA (Fig. 2b).

FIG. 2.

Retinol and its metabolic derivatives RA and 9cRA repress HIV-1 LTR-directed expression in THP-1 monocytes. (a) Untreated or RA-treated (10−7 M; 4 days) THP-1 monocytes were transfected with p(−139/+84)CAT, a plasmid containing a portion of the HIV-1 LTR (nucleotides −139 through +84) directing the expression of CAT. Some transfections also contained pCMVcTat (Tat), a plasmid expressing Tat. Levels of CAT activity were measured 16 to 18 h after transfection. The data are the averages (± standard deviations) of four independent transfections. Fold repression was calculated as the ratio of CAT activities measured from untreated cells to those in retinoid-treated cells. +, treated; −, untreated. (b) Untreated (−) or retinoid-treated (retinol [ROL], 10−6 M, 4 days; RA [AT], 10−7 M, 4 days; 9cRA [9c], 10−7 M, 4 days) THP-1 cells were cotransfected with p(−139/+84)CAT and pCMVcTat. Levels of CAT activity were measured 16 to 18 h after transfection. The data are the averages (± standard deviations) of three independent transfections. trt, treatment.

RA repressed expression from both a CAT reporter containing the entire U3 region and extending to nucleotide +84 of the HIV-1 LTR (data not shown) and a reporter [p(−139/+84)CAT] containing LTR nucleotides −139 through +84 (Fig. 2a). The −139-to-+84 construct includes the HIV-1 core enhancer and promoter as well as the Tat-responsive TAR element. In the case of cotransfection of p(−139/+84)CAT with pCMVcTat, RA treatment resulted in an average CAT activity 13-fold below that seen in untreated THP-1 cells transfected with p(−139/+84)CAT alone. The HIV-1 LTR is constitutively active in THP-1 cells because of high endogenous levels of active nuclear NF-κB (10). RA, therefore, repressed both cellular (NF-κB-dependent) and viral (Tat-dependent) transactivation of the HIV-1 LTR.

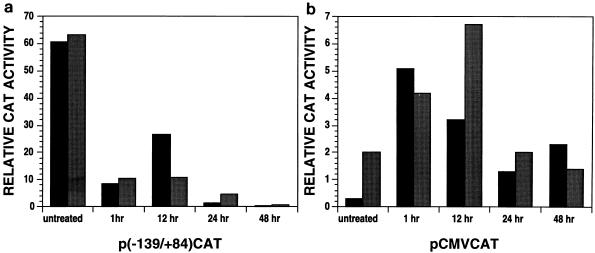

RA pretreatment of THP-1 monocytes for 24 to 48 h repressed HIV-1 LTR-directed expression 20- to 80-fold (Fig. 3a). In contrast, with these pretreatment times CMV immediate-early-promoter-directed expression was slightly activated (Fig. 3b). Shorter pretreatment times had no significant effect on LTR-directed expression (data not shown). In some experiments, RA treatment for greater than 24 h repressed the CMV immediate-early promoter by at most fivefold (data not shown). These results indicate that RA pretreatment did not generally reduce expression of transfected promoters or reduce the transfection efficiency of THP-1 cells.

FIG. 3.

Time course of RA-mediated repression. (a) THP-1 monocytic cells were treated for the indicated times with 10−7 M RA. Both treated and untreated cells were then cotransfected with p(−139/+84)CAT and pCMVcTat. Levels of CAT activity were measured 16 to 18 h after transfection. The data obtained from two independent experiments are shown. (b) THP-1 monocytes were treated as described above and then transfected with pCMVCAT containing the CMV immediate-early promoter directing CAT expression. Levels of CAT activity were measured 16 to 18 h after transfection. The data obtained from two independent experiments are shown.

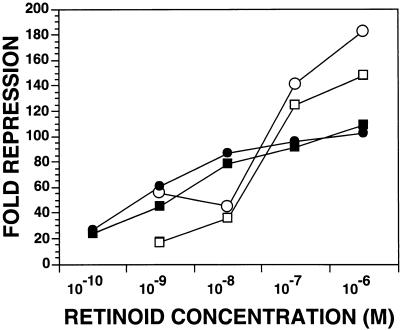

As expected, based on the repression of HIV-1 replication in MDMs (Fig. 1b), retinoids repressed LTR-driven CAT expression over a wide range of concentrations, including concentrations normally found in human plasma (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Concentration dependence of retinoid-mediated repression. THP-1 monocytic cells were treated for 4 days with the indicated concentration of either RA (solid symbols) or retinol (open symbols) and then cotransfected with p(−139/+84)CAT and pCMVcTat. Levels of CAT activity were measured 16 to 18 h after transfection. The data obtained from two independent experiments are shown. Circles, experiment 1; squares, experiment 2.

Repression of HIV-1 gene expression is not obligatorily coupled with cellular differentiation.

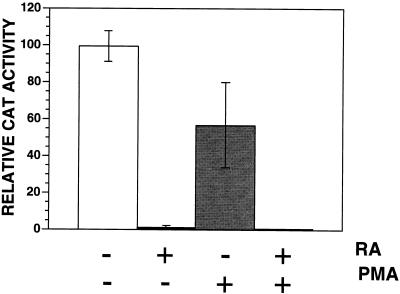

Retinoids have been shown to modulate the differentiation of myeloid cells (24, 40, 42). Thus, the repressive effects of retinoids on HIV-1 gene expression might be due to changes in cellular differentiation that could be induced by other agents. We therefore examined whether PMA, which induces macrophage differentiation of THP-1 monocytes, would also repress HIV-1 gene expression. Both untreated and RA-treated (4 days; 10−7 M) THP-1 monocytes were cotransfected with p(−139/+84)CAT and pCMVcTat. After transfection, one-half of the cells were treated for 24 h with 50 nM PMA. RA treatment repressed HIV-1 LTR-directed CAT activity 90-fold (Fig. 5). In contrast, PMA, which induced these cells to become adherent (data not shown), repressed HIV-1 LTR-CAT activity 1.7-fold (Fig. 5). Combined treatment with RA and PMA repressed HIV-1 LTR expression to the same extent as RA treatment alone. These results indicate that repression is not a general property of differentiation but rather is associated with retinoid-specific changes in the cell. Because RA increased the expression of some macrophage markers on THP-1 monocytes, including CD11b and CD14, but decreased the expression of others, including CD11c and CD33 (Table 2), it is possible that repression was associated with a distinct retinoid-differentiated macrophage phenotype.

FIG. 5.

RA-mediated repression and THP-1 differentiation are not synonymous. Untreated or RA-treated (10−7 M; 4 days) THP-1 monocytes were cotransfected with p(−139/+84)CAT and pCMVcTat. One-half of the transfected cells were also treated with 50 nM PMA. Levels of CAT activity were measured 24 h after transfection. The data are the averages (± standard deviations) of four independent experiments. +, treated; −, untreated.

TABLE 2.

Effects of retinoic acid on the expression of cell surface antigensa

| Cell type and treatment | % Positive for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD33 | CD11b | CD11c | CD14 | |

| THP-1 | ||||

| Untreated | 94 | 31 | 88 | 3.8 |

| Retinoic acid | 79 | 52 | 68 | 17 |

| MDM | ||||

| Untreated | 98 | 92 | 91 | NDb |

| Retinoic acid | 97 | 97 | 94 | ND |

Both untreated and RA-treated (10−7 M; 4 days) THP-1 monocytes or MDMs were stained with fluorescently labeled monoclonal antibodies against CD33, CD11b, CD11c, or CD14. A minimum of 10,000 cells were analyzed for the expression of these markers a Becton Dickinson fluorescence-activated cell sorter. The percentage of positive cells was calculated in comparison to isotype control stained cells.

ND, not determined.

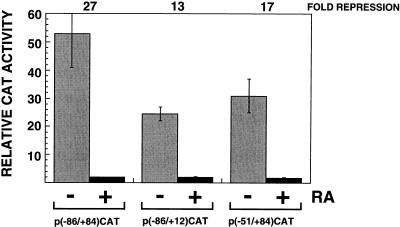

Retinoid repression requires sequences contained within the HIV-1 core promoter.

As a first step in identifying monocyte/macrophage factors responsible for retinoid-mediated repression of HIV-1 gene expression, we constructed LTR-CAT reporter constructs containing various portions of the HIV-1 LTR. These included p(−86/+84)CAT (including Sp1 binding sites and the Tat-responsive element, TAR), p(−51/+84)CAT (Tat responsive but lacking Sp1 binding sites), and p(−86/+12)CAT (including Sp1 binding sites but lacking TAR). RA repressed Tat-induced expression from both p(−86/+84)CAT and p(−51/+84)CAT and basal expression from p(−86/+12)CAT (Fig. 6). RA repression of p(−51/+84)CAT and p(−86/+12)CAT indicates that the RA-sensitive element(s) lies between nucleotides −51 and +12 and that RA repressed activation by both upstream cellular (NF-κB and Sp1) and downstream viral (Tat) activators.

FIG. 6.

RA represses HIV-1 expression from the core promoter. Untreated (−; shaded bars) or RA-treated (10−7 M; 4 days) (+; solid bars) THP-1 cells were transfected with HIV-1 LTR-CAT reporter plasmids containing different portions of the HIV-1 promoter. p(−86/+84)CAT includes the binding sites for Sp1 and TFIID and encodes TAR, the binding site for Tat. p(−51/+84)CAT includes the binding site for TFIID and encodes TAR. p(−86/+12)CAT includes the binding sites for Sp1 and TFIID but does not encode TAR. All transfections also contained pCMVcTat. Levels of CAT activity were measured 16 to 18 h after transfection. The data are the averages (± standard deviations) of at least three to four independent transfections.

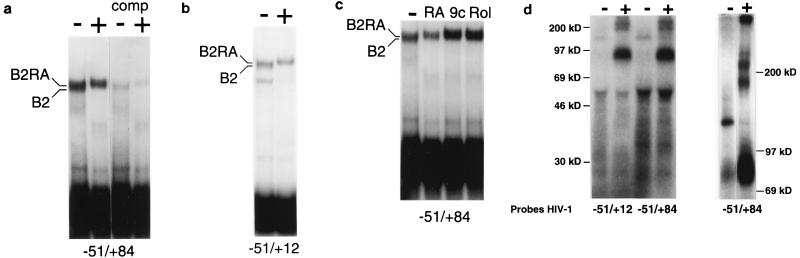

Retinoid treatment is associated with a change in cellular factors which bind to the HIV-1 core promoter.

Based on the above results, we predicted that RA modulated the binding of cellular factors to sequences between −51 and +12 of the LTR. To test this prediction, we compared protein-DNA complexes formed between THP-1 and RA-treated THP-1 extracts with end-labeled DNA fragments corresponding to either −51 to +84 or −51 to +12 of the HIV-1 LTR (Fig. 7a and b). With THP-1 extracts, a specific complex, B2, was detected following nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. When we used RA-differentiated THP-1 cell extracts, an additional complex, B2RA, was seen, which migrated more slowly and replaced the B2 complex seen with untreated extracts. Slower-migrating B2RA complexes were also seen with extracts prepared from either retinol (10−6 M; 4 days)- or 9cRA (10−7 M; 4 days)-differentiated THP-1 cells (Fig. 7c). Therefore, the three retinoids we tested which repress HIV-1 LTR-directed expression induce similar changes in the binding of cellular factors to the LTR.

FIG. 7.

Retinoid treatment of THP-1 monocytes alters the pattern of factors which bind to the HIV-1 promoter. (a and b) Cellular extracts were prepared from both untreated THP-1 monocytes (−) and cells that were treated for 4 days with 10−7 M RA (+). Extracts were incubated with radioactive DNA probes corresponding to either nucleotides −51 through +84 (a) or −51 through +12 (b) of the HIV-1 promoter. Protein-DNA complexes were resolved on a nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. Extracts from untreated cells formed a complex, B2, with the −51-through-+84 probe. A complex with a slower electrophoretic mobility, B2RA, was formed with extracts from RA-treated cells. Both complexes were specifically competed for by a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled self DNA (comp) but not by a fragment containing the CMV immediate-early promoter (data not shown). Similar complexes were formed when the −51-through-+12 probe was used. (c) Cellular extracts were prepared from either untreated THP-1 monocytes (−) or cells treated for 4 days with either 10−7 M RA, 10−7 M 9cRA (9c), or 10−6 M retinol (Rol). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed with a radioactive DNA probe corresponding to nucleotides −51 through +84 of the HIV-1 LTR. (d) Cellular extracts from either untreated (−) or RA-treated (10−7 M; 4 days) (+) cells were incubated with radioactive, bromodeoxyuridine-substituted DNA probes corresponding to either nucleotides −51 through +84 or −51 through +12 of the HIV-1 promoter. Bound proteins were cross-linked to DNA by UV light and then separated on either 10% (left) or 6% (right) SDS polyacrylamide gels.

B2RA could represent either a novel DNA-protein complex formed instead of B2 or an additional RA-induced component that increased the apparent size of B2. To confirm that RA-induced differentiation altered the protein composition of B2, resulting in the formation of B2RA, we covalently cross-linked “body labeled” DNA to proteins in both types of extracts (Fig. 7d). Cellular extracts from both RA-treated and untreated THP-1 cells were incubated with a radiolabeled, bromodeoxyuridine-substituted DNA probe and then cross-linked under UV light. Following DNase I digestion and SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, bound proteins that were specific either to untreated or RA-differentiated cells were identified. We found that a protein migrating at a relative molecular weight of 124,000 (Mr, 124K) was down-regulated by RA and replaced with proteins of Mr 180K, 210K, and 230K. RA-differentiated cells also contained a protein(s) that migrated as a broad band ranging in size from approximately Mr 73K to 90K. The specific association of these proteins with the B2 and B2RA complexes was confirmed by excising the complexes from a first-dimension nondenaturing gel and resolving their associated proteins in a second-dimension SDS-containing gel (data not shown). Therefore, RA treatment of THP-1 cells altered the pattern of cellular factors that bound to the −51-through-+12 region of the HIV-1 core promoter.

DISCUSSION

Freshly isolated PBMCs are refractory to HIV-1 infection but become permissive after in vitro differentiation into macrophages. Addition of physiological concentrations of retinoids, either retinol or retinoic acid, during differentiation results in MDMs that are nonpermissive for HIV-1 replication. However, retinoid treatment after this critical period has no effect on virus replication. Therefore, the presence of retinoids during differentiation induces or maintains expression of cellular factors that inhibit the replication of HIV-1. The inability of retinoids to block virus replication after this critical period argues against a direct effect of retinoids on HIV-1 gene expression.

This indirect effect of retinoids does not result from altered differentiation of either primary monocytes/macrophages or THP-1 cells per se. RA had no effect on differentiation marker expression on primary macrophages and activated some but repressed other differentiation markers on THP-1 cells (Table 2). Moreover, treating THP-1 cells with PMA, a potent inducer of macrophage differentiation, reduced HIV-1 gene expression only modestly (less than twofold, compared to 100- to 300-fold reduction by RA). Although both RA and PMA can induce THP-1 differentiation, the inductions do not result in equivalent macrophage phenotypes. For example, whereas PMA strongly induces THP-1 adherence, RA does so only weakly (data not shown) (22). Moreover, PMA induces interleukin-1β mRNA expression while RA does not (23). In contrast, RA induces lyn mRNA expression while PMA does not (22). It is therefore likely that RA affects macrophage differentiation in subtle ways not revealed by changes in traditional cell surface markers. Although RA is unable to induce complete differentiation of THP-1 cells, RA treatment does increase a number of properties typically associated with macrophages. In vitro, RA treatment of promonocytic cells favors granulocyte differentiation at the expense of macrophage differentiation (40, 42). However, RA does enhance monocyte/macrophage formation induced by other agents, including PMA and vitamin D3 (24, 31, 38), raising the possibility that macrophages that differentiate and/or mature in the presence of retinoids have properties distinct from those of macrophages that differentiate in the absence of vitamin A. One consequence of these proposed effects of retinoids would be inhibition of HIV-1 gene expression and replication.

These conclusions are supported by the results of experiments utilizing the THP-1 monocytic cell line. Transient expression from the HIV-1 LTR is repressed in retinoid-pretreated THP-1 cells. High basal (Tat-independent) HIV-1 expression in THP-1 cells results from constitutively active NF-κB (10). In the presence of retinoids, this high basal expression was reduced to levels below those seen in untreated THP-1 cells transfected with mutant LTRs lacking NF-κB sites [p(−86/+84)CAT)] (data not shown). In addition to reducing basal expression, retinoids also prevented transactivation of the LTR by the viral protein Tat. Therefore, retinoids repress both NF-κB- and Tat-activated expression from the HIV-1 LTR, an effect relatively specific for the viral LTR, since similar repression of either the CMV immediate-early promoter or an NF-κB–collagen promoter was not seen in control experiments (data not shown).

Three properties of retinoid-mediated repression of HIV-1 implicate the general transcription machinery as a primary target. First, the cis-acting sequences required for repression are located within the region of the LTR that includes the binding sites for components of the general transcription machinery. Retinoid-mediated repression mapped to sequences between −51 and +12. This region does not contain a sequence that is similar to the consensus for known retinoic acid response elements (PuGGTCA), nor do RARs and RXRs bind to this region in vitro (data not shown). Therefore, it is unlikely that repression results from the binding of ligand-bound retinoid receptors to the HIV-1 promoter. Second, retinoids block activation by multiple independent factors, including Sp1, NF-κB, and Tat. Finally, retinoids virtually shut down HIV-1 expression. The magnitude of this repression (>200-fold) is consistent with retinoids interfering with the general transcription machinery.

Our data are most consistent with two models of repression. In one model, retinoids induce the expression of a negative factor that binds the HIV-1 core promoter. The binding of such a factor to the HIV-1 LTR should be detectable in biochemical assays. Consistent with this mechanism, we found that retinoid treatment altered the mobility of protein-DNA complexes and led to the presence of four new proteins that formed covalent protein-DNA structures following UV cross-linking. The identities and functions of these proteins remain to be determined. Several candidate proteins that bind to the HIV-1 core promoter and repress transcription have been described, but in most cases the magnitude of the repression of Tat activation by these factors was small or ineffective (8, 13, 21, 26, 45). One exception to this is the factor AP-4. By binding to E boxes that flank the HIV-1 TATA element, AP-4 can prevent TATA element binding protein from binding DNA (25). However, since no similar E boxes are present in the SIVmac LTR, which is repressed by retinoids in an analogous fashion (20a), it is unlikely that AP-4 is responsible for the phenomena we describe here.

Alternatively, the retinoid-induced repressor could interfere with functional interactions between TFIID and transactivators, such as NF-κB and Tat, without directly binding to the core promoter. These interactions are likely to be mediated by gene-specific TBP-associated factors (TAFs) and coactivator proteins. Evidence is accumulating that different promoters are bound by particular combinations of TBP and TAFs. In the case of HIV-1, switching the normal TATA element for one resembling that of the simian virus 40 early promoter inhibits Tat transactivation without affecting basal transcription levels (4). Therefore, RA might modulate the pattern of gene-specific TAFs or coactivator proteins that couple the HIV-1 core promoter to transactivators, such as Tat. Alterations in the functions of these factors could result from their altered expression, physical competition between them and the RARs, or interference with their functions by altered posttranslational modifications. There is precedence for retinoids modulating the expression of coactivator proteins which interact directly with both gene-specific activators and components of the basal transcription machinery, such as TFIID. Retinoic acid stimulates the expression of a protein in embryonal carcinoma cells which can complement the activity of the adenovirus coactivator, E1a (16). This protein, E1a-LA, is required for RA-regulated transcription from the RARβ2 promoter and functionally interacts with both RAR and TFIID (3, 14). In addition, retinoic acid-mediated repression of AP-1 activity is thought to result in part from competition between RARs and AP-1 for the limiting coactivator CBP (11). Retinoids might also exert their effects through changes in the expression of extracellular signal-responsive protein kinases, including members of the protein kinase C family (5, 15). It is conceivable that the retinoid-mediated repression reported here involves altered phosphorylation of coactivators. Further experiments are needed to distinguish between these models.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants to D.A.T. from the American Cancer Society and the American Institute for Cancer Research and by grants to G.A.V. from the NIAID (AI31355) and NHLBI (HL57882).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi A, Gendelman H E, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin M A. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol. 1986;59:284–291. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.284-291.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson S, Davis D N, Dahlback H, Jornvall H, Russell D W. Cloning, structure, and expression of the mitochondrial cytochrome P-450 sterol 26-hydroxylase, a bile acid biosynthetic enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8222–8229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkenstam A, Ruiz M M, Barettino D, Horikoshi M, Stunnenberg H G. Cooperativity in transactivation between retinoic acid receptor and TFIID requires an activity analogous to E1A. Cell. 1992;69:401–412. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90443-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkhout B, Jeang K T. Functional role for the TATA promoter and enhancers in basal and Tat-induced expression of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat. J Virol. 1992;66:139–149. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.139-149.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho Y, Tighe A P, Talmage D A. Retinoic acid induced growth arrest of human breast carcinoma cells requires protein kinase C alpha expression and activity. J Cell Physiol. 1997;172:306–313. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199709)172:3<306::AID-JCP4>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coodley G O, Coodley M K, Nelson H D, Loveless M O. Micronutrient concentrations in the HIV wasting syndrome. AIDS. 1993;7:1595–1600. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199312000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coutsoudis A, Bobat R A, Coovadia H M, Kuhn L, Tsai W Y, Stein Z A. The effects of vitamin A supplementation on the morbidity of children born to HIV-infected women. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1076–1081. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.8_pt_1.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duan L, Ozaki I, Oakes J W, Taylor J P, Khalili K, Pomerantz R J. The tumor suppressor protein p53 strongly alters human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Virol. 1994;68:4302–4313. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4302-4313.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goff S, Traktman P, Baltimore D. Isolation and properties of Moloney murine leukemia virus mutants: use of a rapid assay for release of virion reverse transcriptase. J Virol. 1981;38:239–248. doi: 10.1128/jvi.38.1.239-248.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffin G E, Leung K, Folks T M, Kunkel S, Nabel G J. Activation of HIV expression during monocyte differentiation by induction of NF-κB. Nature. 1989;339:70–73. doi: 10.1038/339070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamei Y, Xu L, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Kurokawa R, Gloss B, Lin S C, Heyman R A, Rose D W, Glass C K, Rosenfeld M G. A CBP integrator complex mediates transcriptional activation and AP-1 inhibition by nuclear receptors. Cell. 1996;85:403–414. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karter D L, Karter A J, Yarrish R, Patterson C, Kass P H, Nord J, Kislak J W. Vitamin A deficiency in non-vitamin-supplemented patients with AIDS: a cross-sectional study. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;8:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato H, Horikoshi M, Roeder R G. Repression of HIV-1 transcription by a cellular protein. Science. 1991;251:1476–1479. doi: 10.1126/science.2006421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keaveney M, Berkenstam A, Feigenbutz M, Vriend G, Stunnenberg H G. Residues in the TATA-binding protein required to mediate a transcriptional response to retinoic acid in EC cells. Nature. 1993;365:562–566. doi: 10.1038/365562a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khuri F R, Cho Y, Talmage D A. Retinoic acid-induced transition from protein kinase C beta to protein kinase C alpha in differentiated F9 cells: correlation with altered regulation of proto-oncogene expression by phorbol esters. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:595–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.La Thangue N B, Rigby P W. An adenovirus E1A-like transcription factor is regulated during the differentiation of murine embryonal carcinoma stem cells. Cell. 1987;49:507–513. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90453-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laudet V, Stehelin D. Flexible friends. Curr Biol. 1992;2:293–295. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leblanc B P, Stunnenberg H G. 9-cis retinoic acid signaling: changing partners causes some excitement. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1811–1816. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.15.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linney E. Retinoic acid receptors: transcription factors modulating gene regulation, development, and differentiation. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1992;27:309–350. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60538-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maciaszek J W, Talmage D A, Viglianti G A. Synergistic activation of simian immunodeficiency virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transcription by retinoic acid and phorbol ester through an NF-κB-independent mechanism. J Virol. 1994;68:6598–6604. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6598-6604.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a.Maciaszek, J. W., et al. Unpublished data.

- 21.Margolis D M, Somasundaran M, Green M R. Human transcription factor YY1 represses human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transcription and virion production. J Virol. 1994;68:905–910. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.905-910.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matikainen S, Hurme M. Comparison of retinoic acid and phorbol myristate acetate as inducers of monocytic differentiation. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:98–103. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matikainen S, Serkkola E, Hurme M. Retinoic acid enhances IL-1 beta expression in myeloid leukemia cells and in human monocytes. J Immunol. 1991;147:162–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakajima H, Kizaki M, Ueno H, Muto A, Takayama N, Matsushita H, Sonoda A, Ikeda Y. All-trans and 9-cis retinoic acid enhance 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced monocytic differentiation of U937 cells. Leuk Res. 1996;20:665–676. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(96)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ou S H, Garcia-Martinez L F, Paulssen E J, Gaynor R B. Role of flanking E box motifs in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 TATA element function. J Virol. 1994;68:7188–7199. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7188-7199.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ou S H, Wu F, Harrich D, Garcia-Martinez L F, Gaynor R B. Cloning and characterization of a novel cellular protein, TDP-43, that binds to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 TAR DNA sequence motifs. J Virol. 1995;69:3584–3596. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3584-3596.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pautrat G, Suzan M, Salaun D, Corbeau P, Allasia C, Morel G, Filippi P. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of U937 cells promotes cell differentiation and a new pathway of virus assembly. Virology. 1990;179:749–758. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90142-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Periquet B A, Jammes N M, Lambert W E, Tricoire J, Moussa M M, Garcia J, Ghisolfi J, Thouvenot J. Micronutrient levels in HIV-1-infected children. AIDS. 1995;9:887–893. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199508000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petit A J C, Terpstra F G, Miedema F. Human immunodeficiency virus infection down-regulates HLA class II expression and induces differentiation in promonocytic U937 cells. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:1883–1889. doi: 10.1172/JCI113032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poli G, Kinter A L, Justement J S, Bressler P, Kehrl J H, Fauci A S. Retinoic acid mimics transforming growth factor B in the regulation of human immunodeficiency virus expression in monocytic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2689–2693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sellmayer A, Obermeier H, Weber C. Intrinsic cyclooxygenase activity is not required for monocytic differentiation of U937 cells. Cell Signalling. 1997;9:91–96. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(96)00109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Semba R D. Vitamin A, immunity, and infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:489–499. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Semba R D, Caiaffa W T, Graham N M H, Cohn S, Vlahov D. Vitamin A deficiency and wasting as predictors of mortality in human immunodeficiency virus-infected injection drug users. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1196–1202. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Semba R D, Graham N M H, Caiaffa W T, Margolik J B, Clement L, Vlahov D. Increased mortality associated with vitamin A deficiency during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2149–2154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Semba R D, Miotti P G, Chiphangwi J D, Saah A J, Canner J K, Dallabetta G A, Hoover D R. Maternal vitamin A deficiency and mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. Lancet. 1994;343:1593–1596. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)93056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Southgate C D, Green M R. The HIV-1 Tat protein activates transcription from an upstream DNA-binding site: implications for Tat function. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2496–2507. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12b.2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stunnenberg H G. Mechanisms of transactivation by retinoic acid receptors. Bioessays. 1993;15:309–314. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taipale J, Matikainen S, Hurme M, Keski-Oja J. Induction of transforming growth factor beta 1 and its receptor expression during myeloid leukemia cell differentiation. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:1309–1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang A M, Graham N M H, Kirby A J, McCall L D, Willett W C, Saah A J. Dietary micronutrient intake and risk of progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected homosexual men. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:937–951. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tocci A, Parolini I, Gabbianelli M, Testa U, Luchetti L, Samoggia P, Masella B, Russo G, Valtieri M, Peschle C. Dual action of retinoic acid on human embryonic/fetal hematopoiesis: blockade of primitive progenitor proliferation and shift from multipotent/erythroid/monocytic to granulocytic differentiation program. Blood. 1996;88:2878–2888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Towers G, Harris J, Lang G, Collins M K, Latchman D S. Retinoic acid inhibits both the basal activity and phorbol ester-mediated activation of the HIV long terminal repeat promoter. AIDS. 1995;9:129–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsai S, Bartelmez S, Sitnicka E, Collins S. Lymphohematopoietic progenitors immortalized by a retroviral vector harboring a dominant-negative retinoic acid receptor can recapitulate lymphoid, myeloid, and erythroid development. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2831–2841. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.23.2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turpin J A, Vargo M, Meltzer M S. Enhanced HIV-1 replication in retinoid-treated monocytes. J Immunol. 1992;148:2539–2546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamaguchi K, Groopman J E, Byrn R A. The regulation of HIV by retinoic acid correlates with cellular expression of the retinoic acid receptors. AIDS. 1994;8:1675–1682. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoon J B, Li G, Roeder R G. Characterization of a family of related cellular transcription factors which can modulate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transcription in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1776–1785. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]