Abstract

The ability of human immunodeficiency virus types 1 (HIV-1) and 2 (HIV-2) to cross-package each other’s RNA was investigated by cotransfecting helper virus constructs with vectors derived from both viruses from which the gag and pol sequences had been removed. HIV-1 was able to package both HIV-1 and HIV-2 vector RNA. The unspliced HIV-1 vector RNA was packaged preferentially over spliced RNA; however, unspliced and spliced HIV-2 vector RNA were packaged in proportion to their cytoplasmic concentrations. The HIV-2 helper virus was unable to package the HIV-1 vector RNA, indicating a nonreciprocal RNA packaging relationship between these two lentiviruses. Chimeric proviruses based on HIV-2 were constructed to identify the regions of the HIV-1 Gag protein conferring RNA-packaging specificity for the HIV-1 packaging signal. Two chimeric viruses were constructed in which domains within the HIV-2 gag gene were replaced by the corresponding domains in HIV-1, and the ability of the chimeric proviruses to encapsidate an HIV-1-based vector was studied. Wild-type HIV-2 was unable to package the HIV-1-based vector; however, replacement of the HIV-2 nucleocapsid by that of HIV-1 generated a virus with normal protein processing which could package the HIV-1-based vector. The chimeric viruses retained the ability to package HIV-2 genomic RNA, providing further evidence for a lack of reciprocity in RNA-packaging ability between the HIV-1 and HIV-2 nucleocapsid proteins. Inclusion of the p2 domain of HIV-1 Gag in the chimera significantly enhanced packaging.

Human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 (HIV-1 and HIV-2) both cause AIDS. Both are members of the lentivirus subfamily of retroviruses, and they have a similar genomic organization with virtually identical open reading frames. At the nucleotide and amino acid levels, there is limited homology (21), with HIV-2 being more closely related to simian immunodeficiency virus than it is to HIV-1.

An essential step in the retroviral life cycle is encapsidation of the genomic RNA. This process is highly specific and results in the selection of the unspliced viral mRNA for packaging into progeny virions against a high background of cellular mRNAs and subgenomic viral RNAs. The viral genomic RNA is reported to represent approximately 1% of the mRNA in the cytoplasm of an infected cell yet constitutes the vast majority of the mRNA in the virion. The basis for the specificity of RNA packaging has two components: (i) the cis-acting RNA packaging signals, known as Ψ (PSI) or E (encapsidation) signals, and (ii) the trans-acting factors, namely, the Gag polyprotein, which specifically binds and sequesters the genomic viral RNA for encapsidation (24).

The cis-acting sequences required for encapsidation of HIV-1 RNA have been mapped by deletion and mutational analysis (1, 10, 23, 29). Initial studies indicated that the region between the major splice donor and the start of gag were important for encapsidation; however, subsequent studies have suggested that other sequences also play an important role (6, 7, 11, 25, 26, 31, 41). Of these regions, a stem-loop upstream of the major splice donor which contains the putative dimerization initiation signal and a stem-loop at the 5′ end of the gag gene have been shown to be important for Gag protein binding in vitro (6, 7, 11, 43) and RNA packaging in vivo (31, 33). The sequences required for encapsidation of HIV-2 RNA have been less intensively studied (19, 35). Deletion analyses have shown that sequences upstream of the major splice donor have a more marked effect on encapsidation of HIV-2 RNA than do sequences between the major splice donor and the start of gag (35).

Mutational analyses of the nucleocapsid (NC) domain of HIV-1 Gag have demonstrated the importance of the NC domain for encapsidation of viral genomic RNA (12, 14, 20, 45). The NC domain lies toward the C-terminal end of the Gag polyprotein. The NC proteins of all retroviruses, with the exception of spumaviruses, contain one or two copies of the sequence Cys-X2-Cys-X4-His-X4-Cys, termed Cys-His motifs, which chelate zinc ions (36). NC proteins are highly basic, often containing contiguous doublets or triplets of basic residues flanking the Cys-His motifs. Mutations disrupting the zinc fingers or the flanking basic residues result in defects in viral RNA packaging. In vitro RNA-protein binding studies have shown that the Gag polyprotein and the NC domain bind specifically to RNA containing the HIV-1 packaging sequences (6, 7, 11, 12, 43).

The role of the NC domain of HIV-1 in determining RNA packaging specificity has been investigated by using chimeric constructs between HIV-1 and Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MuLV) (8, 47). The presence of the HIV-1 NC domain in the context of M-MuLV Gag conferred on the M-MuLV chimera an enhanced ability to specifically package HIV-1 genomic RNA. The present study was designed to further investigate the role of the NC domain of Gag in this process. We constructed vectors based on HIV-1 and HIV-2 so that we could observe cross-packaging by both helper viruses and chimeric constructs of HIV-1 and HIV-2 in which domains within the Gag polyprotein, including NC, of HIV-1 were introduced into HIV-2, and investigated the effect of the domain swaps on RNA encapsidation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

pSVC21 is an infectious proviral clone of the HTLV-IIIB isolate that was originally derived from a plasmid (HXBc2) (17) containing a simian virus 40 origin of replication. The HIV-1 packaging construct, pBCCX-CSF, and HIV-1-based vector, HVPΔEC, have been described previously (22, 41). pSVR is an infectious proviral clone of HIV-2 ROD containing a simian virus 40 origin of replication (35). Restriction sites, where given, refer to positions in the retroviral genome (Los Alamos database numbering, where position 1 is the first base of the 5′ long terminal repeat for HIV-1 and the first nucleotide in the viral RNA for HIV-2). pSVRΔX was created by introducing an XbaI site at nucleotide 553 by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis (28) with the mutagenic oligonucleotide 5′ CGGAGTTTCTAGAGCCCATCTCC 3′. The sequences between XbaI sites at 553 and 5067 were deleted, removing gag and pol coding sequences. pSVRΔAX was created by deleting the sequences between AccI (position 912) and XbaI (position 5067).

The chimeric proviral constructs, pSVRM1 and pSVRM2, were made as follows. An AatII-XhoI (nucleotide [nt] 2032) fragment containing the HIV-2 5′ long terminal repeat, the untranslated region, and gag was cloned from pSVR into pGEM7Zf+ (Promega), creating pGRAXS. Chimeric constructs, pSVRM1 and pSVRM2, were generated by a modification of the “sticky-feet directed mutagenesis” method (9). The PCR primers used for the mutagenesis are shown in Table 1. Primers A1 and B were used to generate a PCR fragment containing the HIV-1 HXBc2 p2 and NC domain with 15 bp of HIV-2 sequence at the 5′ and 3′ ends. A second PCR was performed on the purified PCR product with primers SFA1 and SFB to generate a PCR product with 30 bp of HIV-2 sequence at each end. Primers A2 and B, followed by SFA2 and SFB, were used similarly to generate a PCR product containing the HIV-1 HXBc2 NC domain flanked by 30 bp of HIV-2 sequence. The reverse primer, SFB, was biotinylated at the 5′ end to facilitate the removal of this strand with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads (Dynal) as specified by the manufacturer. The single-stranded PCR products were used to mutate the HIV-2 sequence in pGRAXS (28). The chimeric gag sequences were cloned back into pSVR by the using AatII and XhoI restriction sites. All constructs were subjected to nucleotide sequencing to confirm that the mutated sequences were as expected. All HIV-2 based plasmids were grown in TOP10F′ (Invitrogen) at 30°C to minimize recombination. All other plasmids were grown in DH5α.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in sticky feet-directed mutagenesis

| Primer | Mutant | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | pSVRM1 | 5′-AGATTAATGGCTGAAGCAATGAGCCAAGTA-3′ |

| A2 | pSVRM2 | 5′-TTCGCAGCAGCCCAGAGAGGCAATTTTAGGAAC-3′ |

| B | pSVRM1 and pSVRM2 | 5′-TAAAAAACCAGCCTGTCTCTCAGTACA-3′ |

| SFA1 | pSVRM1 | 5′-GGTGGGCCAGGCCAGAAAGCTAGATTAATGGCTGAAGCAATGAGCCCA-3′ |

| SFA2 | pSVRM2 | 5′-GGACCTGCCCCTATCCCATTCGCAGCAGCCCAGAGAGGCAATTTTAGG-3′ |

| SFB | pSVRM1 and pSVRM2 | 5′-CTTTCCCCAAGGGCCCAGTCCTAAAAAACCAGCCTGTCTCTCAGTACA-3′ |

Plasmids used as templates for the production of riboprobes were constructed as follows. Plasmid KSIIΨCS, used to detect HIV-1 RNA, has been described previously (24). Plasmid KS1SB, used to detect HIV-1 RNA, was created by amplification of HIV-1 sequences from positions 403 to 909 with the primers 5′ TAATGGATCCAGTGGCGAGCCCTCAGATCCTGCAT 3′ and 5′ CTTAGTCGACGCTCCCTGCTTGCCCATACTATATG 3′. The PCR product was then cloned into the SalI and BamHI sites of Bluescript KSII (Stratagene). Plasmid KSIIΨ2KE, used to detect HIV-2 RNA, was constructed by cloning the EheI (nt 306)-KpnI (nt 751) fragment from pSVR into the PstI and KpnI sites of Bluescript KSII (Stratagene). Plasmid KS2ES, used to detect HIV-2 RNA, was created by amplification of HIV-2 sequences from 4915 to 5284 with the primers 5′ CATGGAATTCCAGGGAGGATGGAGAAATGG 3′ and 5′ CTTATAGTCGACTCGGGGATAATTGCAGCAGG 3′. The PCR product was then cloned into the EcoRI and SalI sites of Bluescript KSII (Stratagene).

Cell culture and transfections.

COS-1 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin, and streptomycin. Transient transfection of COS-1 cells was performed by the DEAE-dextran method (46). Cells and supernatants were harvested 48 to 72 h later. Viral particle production was measured by the reverse transcriptase assay (40).

Protein analysis.

COS-1 cells were metabolically labelled with [35S]methionine (>1,000 Ci/mmol) from 44 to 48 h after transfection. Labelled cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (140 mM NaCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.05% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]). Virions released into the supernatant were pelleted by centrifugation for 15 min at 4°C and 80,000 rpm in a Beckman TLA-100 rotor. Pelleted virions were lysed in RIPA buffer, and cell and virion lysates were immunoprecipitated with serum from a panel of HIV-2-infected individuals (Medical Research Council AIDS reagent project) before being analyzed in 5 to 20% acrylamide–SDS gradient gels (Bio-Rad).

RNA isolation.

Cytoplasmic RNA was obtained by rapid lysis at 4°C in Nonidet P-40 buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% [vol/vol] Nonidet P-40). Cell debris and nuclei were removed by a 2-min centrifugation step in a microcentrifuge. The supernatant was adjusted to 0.2% SDS and 125 μg of proteinase K per ml, incubated at 37°C for 15 min, and extracted twice with acid-buffered phenol-chloroform (pH 4.7) and once with chloroform. Nucleic acids were collected by ethanol precipitation, and RNA was stored at −80°C. For RNA extraction from virions, particles released from the cell culture supernatant were pelleted by polyethylene glycol precipitation by the addition of 0.5 volume of 30% polyethylene glycol 8000 in 0.4 M NaCl for 16 h at 4°C. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 2,000 rpm in an MSE 43124-129 rotor at 4°C for 45 min and resuspended in 0.5 ml of TNE (10 mM Tris-Cl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.5]). This material was layered over an equal volume of TNE containing 20% sucrose and centrifuged at 98,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C. Virus particles were lysed in proteinase K buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 100 μg of proteinase K per ml, 100 μg of tRNA per ml) for 30 min at 37°C. After two extractions with acid-buffered phenol-chloroform and one extraction with chloroform, the RNA was precipitated with ethanol and stored at −80°C. The isolated RNA was resuspended in 100 μl of a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 5 U of RNase-free DNase 1 (Promega), and 4 U of RNase inhibitor (Promega) and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 25 μl of a solution containing 50 mM EDTA, 1.5 M sodium acetate, and 1% SDS, and the samples were extracted once with acid-buffered phenol-chloroform and once with chloroform. The RNA was precipitated with ethanol.

RNase protection assay.

32P-labelled riboprobes were synthesized by in vitro transcription of linearized plasmids, KSIIΨCS or KS1SB (HIV-1-specific probes, nt 313 to 830 and 403 to 909, respectively) or KSIIΨ2KE or KS2ES (HIV-2-specific probes, nt 306 to 751 and 4915 to 5284, respectively), with T3 RNA polymerase (Promega). The riboprobes were purified from 5% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gels before being used in RNase protection assays.

Reagents for RNase protection assays were obtained from a commercially available kit (Ambion, Austin, Tex.). Cytoplasmic RNA or RNA extracted from pelleted particles representing one-third of the transfected cells was incubated with 2 × 105 cpm of 32P-labelled probe in 10 μl of hybridization buffer (Ambion) for 10 min at 68°C. Unhybridized regions of the probe were then degraded by the addition of 0.5 U of RNase A and 20 U of RNase T1 in 100 μl of RNase digestion buffer (Ambion). Protected fragments were precipitated in ethanol, resuspended in RNA loading buffer, and separated on 5% polyacrylamide–8 M urea gels. For size determination, 32P-labelled RNA markers synthesized with the RNA Century Marker template set (Ambion) were run in parallel. The gels were subjected to autoradiography, and the relative RNA levels were quantified by densitometry with National Institutes of Health Image software.

RESULTS

Nonreciprocal RNA packaging of HIV-1 and HIV-2.

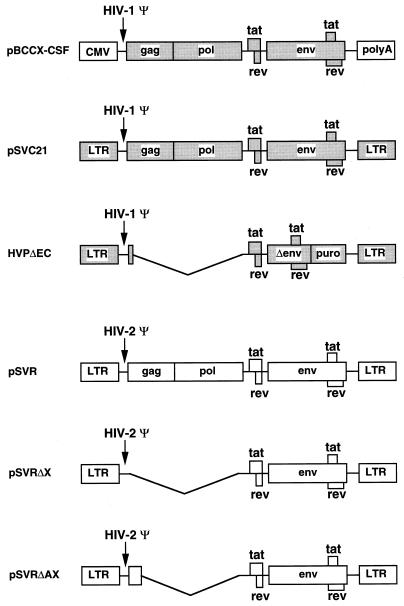

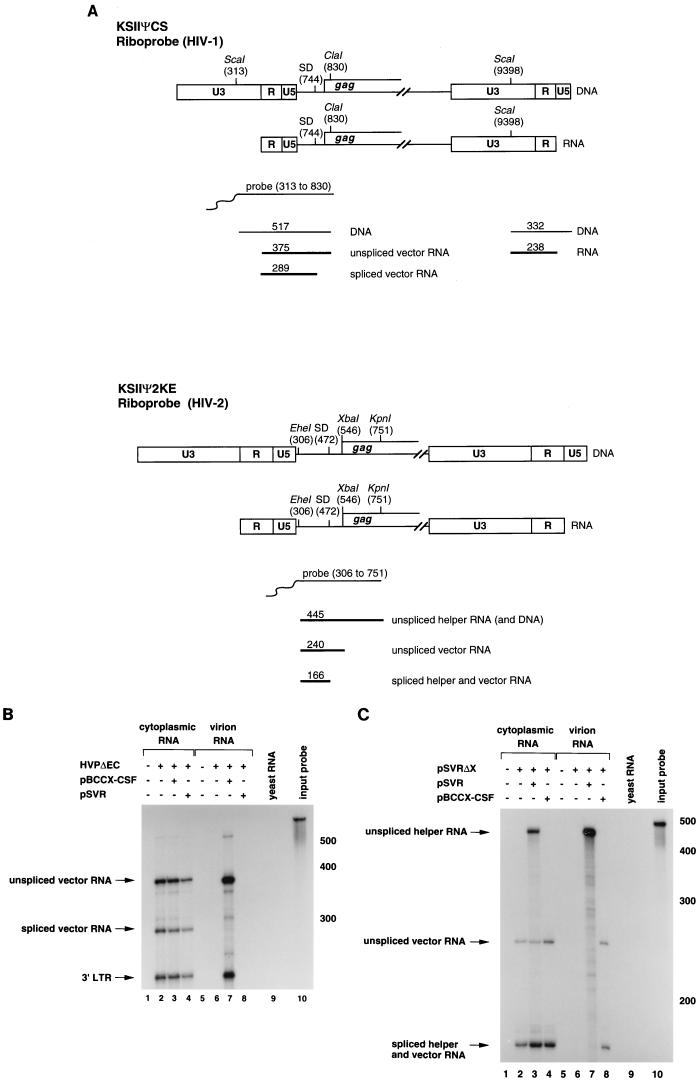

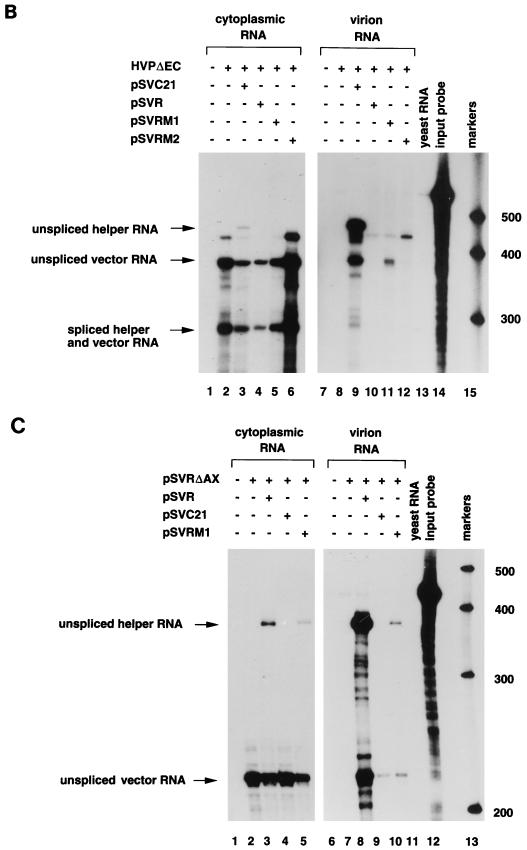

To investigate the ability of HIV-1 and HIV-2 helper viruses to package HIV-1 and HIV-2 RNA, vectors were constructed in which gag and pol sequences were deleted. This allowed us to determine the ability of the helper viruses to package the vector RNA in trans. The vector and helper virus constructs are shown in Fig. 1 and described in Materials and Methods. The HIV-1-based vector, HVPΔEC, has previously been shown to be packageable by HIV-1 (41). The HIV-2-based vector, pSVRΔX, was constructed similarly by deleting gag and pol sequences, leaving the 5′ untranslated region intact (see Materials and Methods for details). HVPΔEC and pSVRΔX were cotransfected into COS-1 cells with either HIV-1 or HIV-2 helper virus constructs (pBCCX-CSF or pSVR respectively) and the ability of the vector RNA to be packaged by the helper viruses was analyzed by an RNase protection assay. The results are shown in Fig. 2. As expected, the HIV-1 vector, HVPΔEC, was packaged by the HIV-1 helper virus (Fig. 2B, lane 7). Full-length vector RNA was packaged preferentially compared to spliced RNA. The HIV-2 helper virus failed to encapsidate the HIV-1 vector. We were unable to detect HIV-1 vector RNA in virions released from cells cotransfected with HIV-2 helper virus (lane 8) despite good levels of expression of vector RNA in the cytoplasm of these cells (lane 4). In contrast, the HIV-2 vector, pSVRΔX, was not packaged by the parental HIV-2 helper virus (Fig. 2C, lane 7) but was packaged by the HIV-1 helper virus (lane 8). We were surprised at the failure of the HIV-2 helper virus to package the HIV-2 vector RNA, because only gag and pol sequences had been removed from the vector and the 5′ untranslated region, containing sequences previously shown to be important for packaging (19, 35), was intact. Full-length helper virus RNA was packaged efficiently and preferentially compared to spliced RNA (Fig. 2C, lane 7). The HIV-2 vector was packaged by the HIV-1 helper virus (lane 8); however, the specificity for full-length RNA was lost: the ratio of full-length to spliced RNA in the virions reflected the ratio of unspliced to spliced RNA present in the cytoplasm of the transfected cells. Thus, the HIV-1 helper virus was able to package both HIV-1 and HIV-2 RNAs, although it did not discriminate between unspliced and spliced HIV-2 RNAs.

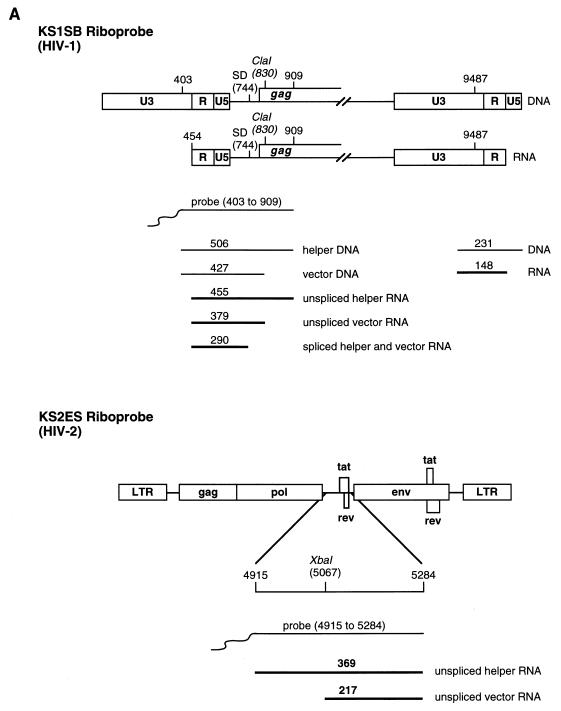

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of helper virus and vector constructs. HIV-1 sequences are shaded. pBCCX-CSF is an HIV-1 particle producer which uses the human cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early promoter to drive the expression of HIV-1 genes. pSVC21 is an HIV-1 proviral construct. HVPΔEC is an HIV-1-based vector with the sequences between ClaI (nt 830) and BalI (nt 2689) deleted and a puromycin resistance gene (puro) inserted in the nef position. pSVR is an HIV-2 proviral construct. pSVRΔX was derived from pSVR by deletion of sequences between an introduced XbaI site at nt 553 and XbaI at nt 5067. pSVRΔAX was derived from pSVR by deletion of sequences between AccI (nt 912) and XbaI (nt 5067). polyA, polyadenylation sequences; Ψ, encapsidation sequences; LTR, long terminal repeat.

FIG. 2.

Nonreciprocal RNA packaging by HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1- and HIV-2-based vectors, HVPΔEC and pSVRΔX, were cotransfected into COS-1 cells with the HIV-1 or HIV-2 helper virus constructs pBCCX-CSF or pSVR, respectively, or alone. RNA isolated from the cytoplasm of the transfected cells or from virions was subjected to RNase protection analysis. (A) Predicted sizes of the protected fragments for the HIV-1- and HIV-2-specific riboprobes, KSIIΨCS and KSIIΨ2KE, respectively. SD, splice donor. (B) RNase protection analysis with the HIV-1-specific riboprobe, KSIIΨCS. Diagnostic bands for HIV-1 vector RNA are 375 nt (unspliced RNA), 289 nt (spliced vector RNA), and 238 nt (3′ LTR). The relative levels of unspliced and spliced vector RNA are 1.9 in lane 3 and is 65.6 in lane 7. (C) RNase protection analysis with the HIV-2 specific riboprobe, KSIIΨ2KE. Diagnostic bands for unspliced HIV-2 helper virus and vector RNA are 445 and 240 nt, respectively, and a band of 166 nt is protected for spliced RNA from both constructs. The relative levels of unspliced and spliced helper RNA are 0.7 in lane 3 and 19.8 in lane 7. The relative levels of unspliced and spliced vector are 0.4 in lane 4 and 0.4 in lane 8. Protection with control RNA (yeast RNA) and with the riboprobe without RNase treatment (input probe) is shown. The positions of RNA size markers are shown in nucleotides to the right of the panels B and C.

Construction of chimeric proviruses.

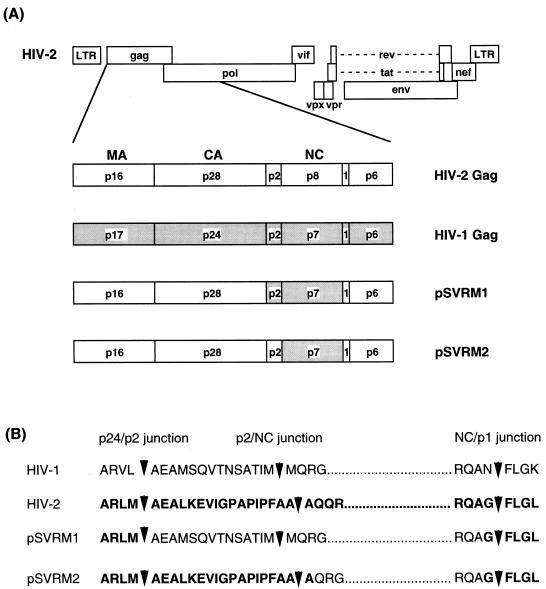

The NC domain of the Gag polyprotein has been strongly implicated in RNA recognition. The nucleocapsid domains of HIV-1 and HIV-2 are fairly well conserved, with about 60% amino acid identity. In contrast, the 5′ untranslated regions of the viruses have little sequence homology and there are no similar structural motifs (4). We therefore designed two chimeras: the first contained the p2 and NC domains of HIV-1 in place of the corresponding domains in HIV-2, and the second contained only the NC domain of HIV-1 in place of the NC domain of HIV-2. The constructs are shown in Fig. 3. Sticky feet-directed mutagenesis was used to swap the domains precisely (see Materials and Methods for details). We aimed to retain consensus protease cleavage sites at the junctions between the HIV-1 and HIV-2 sequences (Fig. 3B), although we have previously shown that cleavage of the Gag polyprotein is not a prerequisite for HIV-1 RNA recognition and encapsidation (24).

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of chimeric constructs used in this study. (A) Gag region of wild-type HIV-1 and HIV-2 and chimeric constructs, pSVRM1 and pSVRM2, showing the subdomains. HIV-1 sequences are shaded. MA, matrix; CA, capsid. (B) Junctions between the HIV-1 and HIV-2 sequences in the chimeric constructs. Amino acid residues derived from HIV-2 sequences are shown in boldface type. The dotted regions indicate NC residues. The predicted protease cleavage sites are indicated by arrowheads.

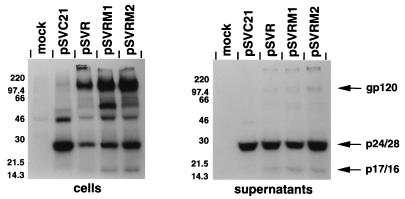

The protein expression, processing, and particle release from the chimeric proviruses was compared to those of the parental HIV-2 provirus. COS-1 cells were transfected with wild-type or chimeric proviral constructs, and cellular and virion proteins were analyzed by an immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 4). Both chimeric constructs expressed similar levels of viral proteins to those of the parental HIV-2 provirus. Viral antigen was released into the supernatant in pelletable virus particles. The chimeras produced similar levels of reverse transcriptase activity to those of the wild-type virus (data not shown). Thus, protein expression and particle release had not been affected by the domain swaps.

FIG. 4.

Immunoprecipitation analysis of chimeric constructs. Wild-type proviral constructs pSVC21 (HIV-1) and pSVR (HIV-2) and chimeric constructs pSVRM1 and pSVRM2 were transfected into COS-1 cells. The cells were labelled with [35S]methionine from 44 to 48 h after transfection, and cell and virion lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation analysis with pooled human sera from a panel of HIV-2-infected individuals. The molecular mass markers are shown to the left in kilodaltons. The predicted positions of viral proteins gp120, p24/28, and p17/16 are indicated.

RNA packaging by the chimeric proviruses.

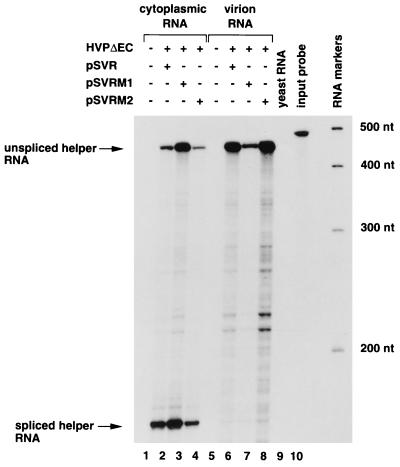

The ability of the chimeras to package HIV-1 RNA was assessed by cotransfection of each with HVPΔEC followed by an RNase protection assay. As expected, the HIV-1 vector was packaged by the HIV-1 helper virus (Fig. 5B, lane 9) and not by the HIV-2 helper virus (lane 10). The HIV-1 vector RNA was packaged by both chimeras, but at a reduced level compared to wild-type HIV-1 (compare lanes 11 and 12 to lane 9). pSVRM1 reproducibly packaged the HIV-1 vector better than pSVRM2 did, suggesting a role for the HIV-1 p2 domain in enhancing packaging. We constructed a second HIV-2 vector in which the sequences between AccI (nt 912) and XbaI (nt 5067) were deleted (Fig. 1). The ability of this vector to be packaged by wild-type HIV-1 and HIV-2 and by the chimeras was assessed by cotransfection followed by an RNase protection assay. The HIV-2 vector, pSVRΔAX, was packaged by the parental HIV-2 helper virus (Fig. 5C, lane 8). It was also packaged by wild-type HIV-1 and by the chimera pSVRM1 (lanes 9 and 10, respectively), indicating that the combined HIV-1 p2 and NC domains of Gag are able to encapsidate an RNA containing the appropriate HIV-2-packaging signals.

FIG. 5.

RNase protection analysis of chimeric proviruses. (A) Predicted sizes of the protected fragments for the HIV-1- and HIV-2-specific riboprobes, KS1SB and KS2ES, respectively. SD, splice donor. (B) COS-1 cells were transfected with the HIV-1 vector HVPΔEC alone (lanes 2 and 8) or with pSVC21 (lanes 3 and 9), pSVR (lanes 4 and 10), pSVRM1 (lanes 5 and 11), or pSVRM2 (lanes 6 and 12) or mock transfected (lanes 1 and 7). Cytoplasmic RNA (lanes 1 to 6) and virion RNA (lanes 7 to 12) were subjected to RNase protection analysis with an HIV-1 specific riboprobe, KS1SB. The positions of unspliced helper virus RNA (455 nt), unspliced vector RNA (379 nt), and spliced helper and vector RNA (290 nt) are indicated by arrows. The relative levels of unspliced vector packaged by the various helper constructs compared to HIV-1 helper virus (given an arbitrary value of 1) are 0.31 in lane 11 and 0.03 in lane 12. Protection with yeast RNA (lane 13) and the riboprobe without RNase treatment (lane 14) is shown. The RNA molecular size markers (in nucleotides) are shown (lane 15). (C) COS-1 cells were transfected with the HIV-2 vector pSVRΔAX alone (lanes 2 and 7), or with pSVR (lanes 3 and 8), pSVC21 (lanes 4 and 9), or pSVRM1 (lanes 5 and 10) or mock transfected (lanes 1 and 6). Cytoplasmic RNA (lanes 1 to 5) and virion RNA (lanes 6 to 10) were subjected to RNase protection analysis with an HIV-2-specific riboprobe, KS2ES. The positions of unspliced HIV-2 helper virus RNA (369 nt) and unspliced vector RNA (217 nt) are indicated by arrows. The relative levels of unspliced vector and unspliced helper RNA are 3.2 in lane 3, 17.4 in lane 5, 0.9 in lane 8, and 1.1 in lane 10. Protection with yeast RNA (lane 11) and the riboprobe without RNase treatment (lane 12) are shown. The RNA molecular size markers (in nucleotides) are shown (lane 13).

The ability of the chimeras to package their own genomic RNA (i.e., containing the HIV-2 5′ untranslated region) in cis was examined and found to be similar to that of the parental HIV-2 construct (Fig. 6, compare lanes 7 and 8 to lane 6). Unspliced RNA was packaged preferentially compared to spliced RNA. The NC domain of HIV-1, in the context of HIV-2 Gag polyprotein, is thus able to package both HIV-1 and HIV-2 RNAs.

FIG. 6.

RNA encapsidation in cis by chimeric proviruses. COS-1 cells were cotransfected with the HIV-1 vector HVPΔEC and pSVR (lanes 2 and 6), pSVRM1 (lanes 3 and 7), or pSVRM2 (lanes 4 and 8) or mock transfected (lanes 1 and 5). Cytoplasmic RNA (lanes 1 to 4) and virion RNA (lanes 5 to 8) was subjected to RNase protection analysis with an HIV-2-specific riboprobe, KSIIΨ2KE. The positions of unspliced HIV-2 helper virus RNA (445 nt) and spliced RNA (240 nt) are indicated by arrows. The relative levels of unspliced helper RNA and spliced RNA are 0.6 in lane 2, 1.0 in lane 3, 0.6 in lane 4, 47.0 in lane 6, 57.2 in lane 7, and 23.4 in lane 8. The relative levels of packaging of unspliced helper RNA compared to wild-type HIV-2 (given an arbitrary value of 1) are 0.26 for pSVRM1 and 1.57 for pSVRM2. Protection with yeast RNA (lane 9) and with the riboprobe without RNase treatment (lane 10) is shown. RNA size markers are shown to the right (sizes in nucleotides are indicated).

DISCUSSION

Although similar in genomic organization, HIV-1 and HIV-2 are dissimilar in many ways. Previous studies on the transactivator proteins Tat and Rev of the two viruses have shown a lack of reciprocity (3, 5, 13, 15, 16, 18, 30, 32, 44). This is the first study to formally cross-complement cis- and trans-acting factors involved in packaging. HIV-1 has been reported to package HIV-2 RNA (2, 39) and simian immunodeficiency virus RNA (42); however, the ability of HIV-2 to package HIV-1 RNA was not investigated. In this report, we demonstrate that while HIV-1 is able to package both HIV-1 and HIV-2 RNA, HIV-2 is not able to package HIV-1 RNA. The HIV-1 helper virus packaged the HIV-2 vector RNA with a lack of preference for unspliced RNA over spliced RNA. In contrast, the HIV-1 p2 and NC domains, in the context of HIV-2 Gag polyprotein, showed a preference for unspliced RNA.

The HIV-2 helper virus did not package an HIV-1 vector, nor did it package an HIV-2-based vector. The failure of HIV-2 helper virus to package pSVRΔX was surprising since the vector contained the entire 5′ untranslated region of the HIV-2 genome. Arya and Gallo (2) showed that an HIV-2 construct in which gag and pol sequences had been deleted was packaged by HIV-1, but they did not test the ability of HIV-2 helper virus to package the HIV-2 vector, nor did they report on the relative levels of unspliced to spliced vector RNA that were packaged by HIV-1. Poeschla et al. reported the packaging of an HIV-2-based vector by an HIV-2 packaging cell line by measuring vector transduction efficiencies (39). Their HIV-2 vector had its gag and pol sequences deleted; however, some of the p17 (matrix) domain of Gag remained, but the extent of the deletion was not documented. There are several possible explanations for the failure of HIV-2 helper virus to package pSVRΔX: first, there may be cis-acting sequences in the gag or pol genes, absent from pSVRΔX, that are required for RNA packaging; second, the packaging capacity of HIV-2 could be saturated by packaging of wild-type HIV-2 RNA; or third, RNA packaging in HIV-2 could be linked to translation of Gag. Previous studies of HIV-2-packaging signals have been restricted to the 5′ untranslated region of the genome, where deletion of sequences upstream of the major splice donor caused a reduction in genomic RNA encapsidation (19, 35); however, neither study addressed the question of which sequences are sufficient for encapsidation in HIV-2. The packaging capacity of HIV-2 was not saturated, since a second vector, pSVRΔAX, was packaged by HIV-2 helper virus. A link between packaging and translation in HIV-2 is possible, although for HIV-1 it has previously been shown by several groups that HIV-1-based vectors lacking gag and pol sequences can be efficiently packaged by HIV-1 (34, 37, 41). A second HIV-2-based vector, pSVRΔAX, which contained an additional 366 nt of Gag-coding sequences, was packaged by HIV-2 helper virus. The role of HIV-2 gag sequences in packaging of HIV-2-based vectors is currently being investigated.

The HIV-1 and HIV-2 NC proteins are very similar, with 60% identical amino acid residues and with conservative substitutions in much of the rest of the proteins. We attempted to identify the residues within NC that are responsible for the ability to recognize HIV-1 RNA. The chimeric proviruses we constructed expressed and processed viral proteins and released virus particles normally, indicating that the domain swaps had not affected protease mediated cleavage, virus assembly, or budding. The ability of the chimeras to package an HIV-1 vector was assessed in comparison to wild-type HIV-1 and HIV-2 helper viruses. The presence of the HIV-1 p2 and NC domains conferred on the HIV-2 chimeric construct the ability to package an HIV-1 vector. The level of encapsidation of the HIV-1 vector was lower than that observed for wild-type HIV-1, suggesting that other domains of the HIV-1 Gag polyprotein are required for optimal encapsidation of HIV-1 RNA. A chimera in which only the NC domain had been exchanged also encapsidated the HIV-1 vector, although the level of packaging was reproducibly lower than that seen for the chimera containing both the p2 and NC domains of HIV-1, suggesting that there are residues within the HIV-1 p2 domain that contribute to the specific recognition of the HIV-1 packaging signal. In contrast to NC, the p2 domains of HIV-1 and HIV-2 are quite different, with only 35% amino acid homology. This study suggests a further important role for the HIV-1 p2 domain, which has previously been shown to be essential for virion assembly and viral infectivity (27, 38).

Recognition of the cis-acting packaging signals on the viral genomic RNA is carried out by the Gag polyprotein. Proteolytic cleavage of Gag polyprotein to its cleavage products occurs during or after budding of the progeny virions. Thus, although NC, with its nucleic acid binding capacity, probably constitutes the major high-affinity interaction involved in packaging, the discrimination of genomic RNA might be conferred by other regions within Gag either by directly interacting with the RNA-packaging signal or by influencing the three-dimensional array of RNA binding motifs in NC such that they are optimized for binding the genome in its monomeric or dimeric state. The effect of p2 in this study was striking and reproducible, and further studies are under way to analyze its function in RNA encapsidation. Chimeras with groups of amino acid residues within HIV-2 NC exchanged for the corresponding residues from HIV-1 did not package HIV-1 RNA to a measurable level (data not shown). The low level of packaging of HIV-1 RNA by the chimera containing just the HIV-1 NC domain made it difficult to assess the role in viral RNA recognition and encapsidation of individual residues of HIV-1 NC. It may be necessary to use in vitro RNA-protein binding assays to address the question of which residues within HIV-1 Gag convert HIV-2 Gag into a polyprotein capable of packaging HIV-1 RNA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Royal Society and the Medical Research Council (United Kingdom) and supported by grant 960675 (Biomed II). J.F.K. is funded by a Royal Society Dorothy Hodgkin Research Fellowship.

We thank John Sinclair for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aldovini A, Young R A. Mutations of RNA and protein sequences involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 packaging result in production of noninfectious virus. J Virol. 1990;64:1920–1926. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.1920-1926.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arya S K, Gallo R C. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 2-mediated inhibition of HIV type 1: a new approach to gene therapy of HIV-infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4486–4491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arya S K, Gallo R C. Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 long terminal repeat: analysis of regulatory elements. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9753–9757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkhout B. Structure and function of the human immunodeficiency virus leader RNA. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1996;54:1–34. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60359-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkhout B, Gatignol A, Silver J, Jeang K T. Efficient trans-activation by the HIV-2 Tat protein requires a duplicated TAR RNA structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1839–1846. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.7.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkowitz R D, Goff S P. Analysis of binding elements in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomic RNA and nucleocapsid protein. Virology. 1994;202:233–246. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkowitz R D, Luban J, Goff S P. Specific binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag polyprotein and nucleocapsid protein to viral RNAs detected by RNA mobility shift assays. J Virol. 1993;67:7190–7200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7190-7200.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkowitz R D, Ohagen A, Hoglund S, Goff S P. Retroviral nucleocapsid domains mediate the specific recognition of genomic viral RNAs by chimeric gag polyproteins during RNA packaging in vivo. J Virol. 1995;69:6445–6456. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6445-6456.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clackson T, Gussow D, Jones P T. General application of PCR to gene cloning and manipulation. In: McPherson M J, Quirke P, Taylor G R, editors. PCR: a practical approach. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1991. pp. 204–207. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clavel F, Orenstein J M. A mutant of human immunodeficiency virus with reduced RNA packaging and abnormal particle morphology. J Virol. 1990;64:5230–5234. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.5230-5234.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clever J, Sassetti C, Parslow T G. RNA secondary structure and binding sites for gag gene products in the 5′ packaging signal of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1995;69:2101–2109. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2101-2109.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dannull J, Surovoy A, Jung G, Moelling K. Specific binding of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein to PSI RNA in vitro requires N-terminal zinc finger and flanking basic amino acid residues. EMBO J. 1994;13:1525–1533. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dillon P J, Nelbock P, Perkins A, Rosen C A. Function of the human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 Rev proteins is dependent on their ability to interact with a structured region present in env gene mRNA. J Virol. 1990;64:4428–4437. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4428-4437.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorfman T, Luban J, Goff S P, Haseltine W A, Gottlinger H G. Mapping of functionally important residues of a cysteine-histidine box in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein. J Virol. 1993;67:6159–6169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6159-6169.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emerman M, Guyader M, Montagnier L, Baltimore D, Muesing M A. The specificity of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2 transactivator is different from that of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. EMBO J. 1987;6:3755–3760. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fenrick R, Malim M H, Hauber J, Le S Y, Maizel J, Cullen B R. Functional analysis of the Tat trans activator of human immunodeficiency virus type 2. J Virol. 1989;63:5006–5012. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.12.5006-5012.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher A G, Collalti E, Ratner L, Gallo R C, Wong Staal F. A molecular clone of HTLV-III with biological activity. Nature. 1985;316:262–265. doi: 10.1038/316262a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garrett E D, Cullen B R. Comparative analysis of Rev function in human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2. J Virol. 1992;66:4288–4294. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4288-4294.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garzino Demo A, Gallo R C, Arya S K. Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2): packaging signal and associated negative regulatory element. Hum Gene Ther. 1995;6:177–184. doi: 10.1089/hum.1995.6.2-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorelick R J, Chabot D J, Rein A, Henderson L E, Arthur L O. The two zinc fingers in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein are not functionally equivalent. J Virol. 1993;67:4027–4036. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4027-4036.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guyader M, Emerman M, Sonigo P, Clavel F, Montagnier L, Alizon M. Genome organization and transactivation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2. Nature. 1987;326:662–669. doi: 10.1038/326662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haddrick M, Han Liu Z, Lau A, Heaphy S, Cann A J. Production of non-infectious human immunodeficiency virus-like particles which package specifically viral RNA. J Virol Methods. 1996;61:89–93. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(96)02073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayashi T, Shioda T, Iwakura Y, Shibuta H. RNA packaging signal of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Virology. 1992;188:590–599. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90513-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaye J F, Lever A M. trans-acting proteins involved in RNA encapsidation and viral assembly in human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1996;70:880–886. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.880-886.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaye J F, Richardson J H, Lever A M. cis-acting sequences involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA packaging. J Virol. 1995;69:6588–6592. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6588-6592.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim H J, Lee K, O’Rear J J. A short sequence upstream of the 5′ major splice site is important for encapsidation of HIV-1 genomic RNA. Virology. 1994;198:336–340. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krausslich H G, Facke M, Heuser A M, Konvalinka J, Zentgraf H. The spacer peptide between human immunodeficiency virus capsid and nucleocapsid proteins is essential for ordered assembly and viral infectivity. J Virol. 1995;69:3407–3419. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3407-3419.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunkel T A, Roberts J D, Zakour R A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lever A, Gottlinger H, Haseltine W, Sodroski J. Identification of a sequence required for efficient packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA into virions. J Virol. 1989;63:4085–4087. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.4085-4087.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis N, Williams J, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold M L. Identification of a cis-acting element in human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) that is responsive to the HIV-1 rev and human T-cell leukemia virus types I and II rex proteins. J Virol. 1990;64:1690–1697. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1690-1697.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luban J, Goff S P. Mutational analysis of cis-acting packaging signals in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA. J Virol. 1994;68:3784–3793. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3784-3793.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malim M H, Bohnlein S, Fenrick R, Le S Y, Maizel J V, Cullen B R. Functional comparison of the Rev trans-activators encoded by different primate immunodeficiency virus species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8222–8226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McBride M S, Panganiban A T. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 encapsidation site is a multipartite RNA element composed of functional hairpin structures. J Virol. 1996;70:2963–2973. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2963-2973.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McBride M S, Schwartz M D, Panganiban A T. Efficient encapsidation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vectors and further characterization of cis elements required for encapsidation. J Virol. 1997;71:4544–4554. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4544-4554.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCann E M, Lever A M. Location of cis-acting signals important for RNA encapsidation in the leader sequence of human immunodeficiency virus type 2. J Virol. 1997;71:4133–4137. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.4133-4137.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morellet N, de Rocquigny H, Mely Y, Jullian N, Demene H, Ottmann M, Gerard D, Darlix J L, Fournie Zaluski M C, Roques B P. Conformational behaviour of the active and inactive forms of the nucleocapsid NCp7 of HIV-1 studied by 1H NMR. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:287–301. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parolin C, Dorfman T, Palu G, Gottlinger H, Sodroski J. Analysis in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vectors of cis-acting sequences that affect gene transfer into human lymphocytes. J Virol. 1994;68:3888–3895. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3888-3895.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pettit S C, Moody M D, Wehbie R S, Kaplan A H, Nantermet P V, Klein C A, Swanstrom R. The p2 domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag regulates sequential proteolytic processing and is required to produce fully infectious virions. J Virol. 1994;68:8017–8027. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8017-8027.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poeschla E, Corbeau P, Wong Staal F. Development of HIV vectors for anti-HIV gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11395–11399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Potts B J. ’Mini’ reverse transcriptase (RT) assay. In: Aldovini A, Walker B D, editors. Techniques in HIV research. New York, N.Y: Stockton Press; 1990. pp. 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richardson J H, Child L A, Lever A M. Packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA requires cis-acting sequences outside the 5′ leader region. J Virol. 1993;67:3997–4005. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3997-4005.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rizvi T A, Panganiban A T. Simian immunodeficiency virus RNA is efficiently encapsidated by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J Virol. 1993;67:2681–2688. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2681-2688.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sakaguchi K, Zambrano N, Baldwin E T, Shapiro B A, Erickson J W, Omichinski J G, Clore G M, Gronenborn A M, Appella E. Identification of a binding site for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5219–5223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakai H, Siomi H, Shida H, Shibata R, Kiyomasu T, Adachi A. Functional comparison of transactivation by human retrovirus rev and rex genes. J Virol. 1990;64:5833–5839. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.5833-5839.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmalzbauer E, Strack B, Dannull J, Guehmann S, Moelling K. Mutations of basic amino acids of NCp7 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 affect RNA binding in vitro. J Virol. 1996;70:771–777. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.771-777.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Selden R F. Transfection using DEAE-dextran. In: Ausubel R, Brent R E, Kingston D D, Moore J G, Seidman J A, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Wiley Interscience; 1987. pp. 9.21–9.22. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y, Barklis E. Nucleocapsid protein effects on the specificity of retrovirus RNA encapsidation. J Virol. 1995;69:5716–5722. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5716-5722.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]