Abstract

Small molecule inhibitors are a key resource in the cell signaling toolbox. However, because of their global distribution in the cell, they cannot provide a refined understanding of signaling at distinct subcellular locations. Bucko and colleagues have designed a novel tool to localize inhibitors to specific protein scaffolds, opening a new avenue to study localized kinase activity.

Keywords: Protein kinases, kinase inhibitors, mitosis, SNAP-tag

A wide array of small molecule drugs has been developed to inhibit protein kinases, enzymes that play a profound role in the regulation of cellular pathways via their phosphorylation of diverse substrates. Because deregulated phosphorylation drives a variety of different diseases such as cancer [1] and diabetes [2], there is considerable interest in using inhibitors to understand kinase function in a cellular context. However, these enzymes often exert distinct functions at discrete cellular locations [3], and pharmacological inhibition of kinases with small-molecule compounds generally occurs in a global manner, thus prohibiting studies on localized kinase action. As a solution to this problem, Bucko and colleagues created a novel tool, local kinase inhibition (LoKI), that directs kinase inhibitors to discrete cellular scaffolds, such as A-Kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs), thus providing localized kinase inhibition [4]. Using this tool, they were able to probe the mechanism by which localized kinase signaling affects mitotic progression.

LoKI utilizes SNAP-tag self-labelling technology to direct pharmacological inhibitors to kinases anchored at specific cellular locations. The SNAP-tag consists of human O6-alkylguanine DNA-alkyltransferase (an enzyme) fused to a protein of interest, creating a ‘loading dock’ that can then be used to recruit a variety of molecules [5]. Cells expressing this genetically-encoded loading dock are treated with an O6-benzylguanine (BG) derivative that forms a covalent thioester bond with a Cys in the SNAP-tag; the BG derivative can be modified by the conjugation of a variety of molecules ranging from dyes [6] to oligonucleotides [7] to beads [8]. Bucko and colleagues took advantage of SNAP-tag labeling to direct small molecule kinase inhibitors, conjugated to the BG derivative chloropyrimidine, to specific protein scaffolds [4]. Specifically, they fused the SNAP-tag moiety to the centrosome-targeting PACT (pericentrin-AKAP450-centrosomal targeting) domain, thus affording localized inhibition of the relevant kinases in the vicinity of this scaffold.

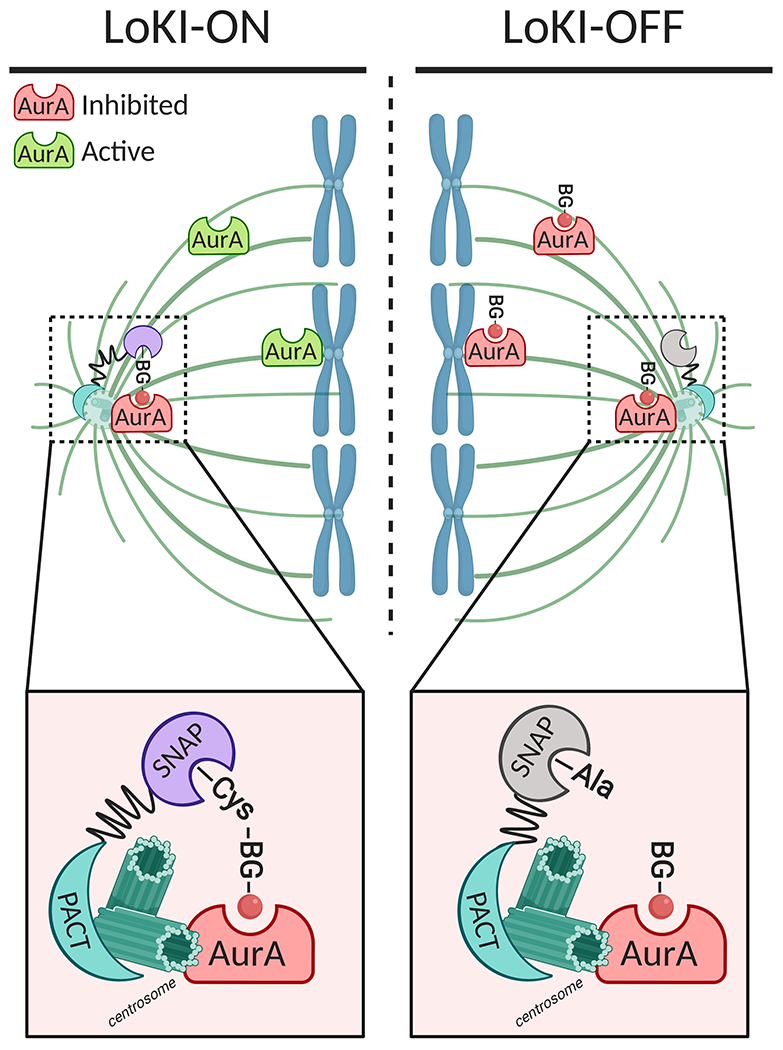

As a proof of concept, the authors used the LoKI tool to analyze the impact of polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) and aurora kinase A (AurA) signaling at the centrosome during mitosis. This is a particularly relevant system for exploiting this tool because these mitotic kinases have distinct functions depending on their cellular localization. For example, centrosomal AurA plays a crucial role in regulating centrosomal maturation and microtubule spindle formation during early mitosis, but AurA also has a separate function in regulating the proper attachment of microtubules to the kinetochore [9]. To parse out these diverse functions, Bucko et al. SNAP-tagged a centrosome-targeting PACT domain and synthesized BG derivatives conjugated to well-characterized AurA and Plk1 active-site inhibitors [10,11], thus allowing direct targeting of these drugs to the centrosome (Figure 1). They then expressed the LoKI construct in a variety of cell types, including U2OS osteosarcoma cells, retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells and HeLa cells. In addition to this tool (called LoKI-ON), they also mutated the reactive Cys residue in the SNAP-tag to an Ala to prohibit formation of a covalent bond with the BG-conjugated inhibitor (LoKI-OFF, Figure 1), thus providing a useful control to demonstrate the difference between local and global inhibition. The authors demonstrated that local inhibition of AurA and Plk1 using the LoKI-ON system resulted in reduced phosphorylation of AurA and Plk1 at key residues (Thr288 and Thr210, respectively), a readout for kinase activity. Moreover, a greater reduction in phosphorylation was observed in LoKI-ON inhibitor-treated cells than in LoKI-OFF cells relative to the dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle control, suggesting that local kinase inhibition is useful for the study of discrete cellular functions that may be masked by global inhibition.

Figure 1:

The LoKI-ON/OFF system informs on centrosomal AurA signaling.

The LoKI-ON platform consists of a genetically-encoded centrosome-targeting pericentrin/AKAP450/centrosomal targeting (PACT) domain connected to a SNAP-tag in which Cys144 will form a covalent thioester bond with a benzylguanine (BG) derivative conjugated to the AurA inhibitor MLN8237 (red circle). Mutation of Cys144 to Ala blocks this reaction, forming the basis of the LoKI-OFF platform. In LoKI-ON cells, the centrosome is labelled with the BG-conjugated AurA inhibitor, providing local kinase inhibition. Conversely, the inhibitor is homogenously distributed throughout the cell in LoKI-OFF cells, resulting in global AurA inhibition. This system therefore allows direct comparison of local versus global kinase inhibition. Figure created with Biorender.

To demonstrate the versatility of the LoKI technology, the authors created an additional LoKI tool that localizes to the kinetochore rather than the centrosome by replacing the centrosome-targeting PACT domain by the kinetochore-targeting domain of the protein Mis12. After treating cells expressing Mis12-LoKI-ON with the BG-conjugated AurA inhibitor, they probed for the phosphorylation of Hec1, a kinetochore-localized substrate of AurA [12]. They observed a reduction in phosphorylated Hec1 at kinetochores of Mis12-LoKI-ON cells after addition of the BG-conjugated AurA inhibitor. Conversely, they observed no significant changes in Hec1 phosphorylation at the kinetochore in cells expressing PACT-LoKI-ON. These experiments show specific targeting of AurA signaling at discrete complexes. and elegantly demonstrate the specificity that can be achieved with LoKI tools.

Furthermore, the authors used their novel LoKI tool to demonstrate that shutting off centrosomal Plk1 or AurA, either alone or in combination, causes defects in centrosome maturation and delays mitotic progression. During late G2 phase, AurA and Plk1 signaling plays an essential role in the accumulation of γ-tubulin and other pericentriolar material at the centrosome, leading to the eventual formation of bipolar mitotic spindles [9]. Deregulation of these signaling pathways results in abnormal bipolar or monopolar spindle structures that can lead to improper chromosomal segregation and aneuploidy. Using PACT-LoKI-ON-expressing cells, the authors asked if direct inhibition of centrosomal Plk1 resulted in mitotic spindle defects. They observed an increase in the formation of monopolar and abnormal bipolar spindles in LoKI-ON cells versus LoKI-OFF cells. In addition, γ-tubulin accumulation at centrosomes was decreased in LoKI-ON cells treated with the BG-conjugated Plk1 inhibitor. On a more global scale, they found that expressing a dual SNAP-tagged LoKI, and co-treating with both the BG-conjugated Plk1 and AurA inhibitors, tripled the time cells spent in mitosis, an indirect measure of mitotic defects. Interestingly, although there was a twofold difference in the duration of mitosis between LoKI-ON and LoKI-OFF cells treated with the AurA inhibitor alone, there was no difference in cells treated with the Plk1 inhibitor alone. This result indicates that there is a synergistic effect of inhibiting both enzymes.

Finally, the authors took one more step to demonstrate the versatility of LoKI by using it in zebrafish embryos, an ideal model for imaging analysis owing to their transparency. By microinjecting either mCherry-PACT-LoKI-ON or mCherry-PACT-LoKI-OFF mRNA into zebrafish embryos, they were able to directly visualize localization of the LoKI tool at centrosomes. Microinjection of the Plk1 inhibitor into the LoKI-ON expressing embryos resulted in an increased mitotic index (percent of cells actively in mitosis) compared with the LoKI-OFF expressing embryos, thus providing another example of how local inhibition of Plk1 at centrosomes has a profound effect on mitotic progression compared with global inhibition.

With this work [4], the authors have described a novel way to inhibit kinase activity locally at specific protein scaffolds and have used this technology to directly probe how centrosomal pools of the mitotic kinases AurA and Plk1 affect centrosome maturation and mitotic progression. However, this tool has some limitations that should be taken into account. Importantly, conjugation of inhibitors to the BG derivative and the SNAP-tagged protein can have an impact on inhibitor function. For example, the authors state that the addition of the BG derivative can sterically hinder the ability of the inhibitor to access the active site of the kinase. In addition, they showed that, in the case of the Plk1 inhibitor BI2536, conjugation to the BG derivative increased the IC50 by 10-fold, and binding of this conjugated inhibitor to the SNAP-tag protein complex resulted in an even greater IC50 increase. Interestingly, this reduction in potency upon conjugation was not observed with the AurA inhibitor. Furthermore, the authors showed that prolonged incubation (4 h) with the inhibitors was necessary to label the SNAP-tag, attributing this delay to most likely a decrease in cell permeability of the conjugated inhibitors. For these reasons the concentration required to label the SNAP-tag must be carefully determined because excess inhibitor can result in saturation of the SNAP-tag and inhibition of the kinase at other locations. Therefore, rigorous validation and application of newly synthesized LoKI inhibitors must be performed. One suggestion made by the authors to address some of these limitations is to use photocaged inhibitors wherein the LoKI inhibitor is conjugated to a photolabile group that is cleaved following irradiation with UV light [13]: the function of the inhibitor is therefore blocked until cleavage occurs, allowing the LoKI platform to be turned on at a precise time.

LoKI technology is an exciting new approach to study localized kinase activity. By applying this tool to the study of mitotic signaling, where several key kinases have specific downstream effects depending on their location, the authors have provided insight into how Plk1 and AurA activity affect mitotic progression via signaling at either the kinetochore or centrosome. One can envision several next steps for this technology. The authors suggested using various other self-labeling systems, such as the CLIP-tag or Halo-tag, to inhibit multiple kinases at the same location. Furthermore, this system could be applied to study other signaling enzymes such as phosphatases and E3-ubiquitin ligases that also play distinct and critical roles during the cell cycle. Lastly, the use of CRISPR/Cas9 technology to direct inhibitors to endogenous scaffolds would provide minimal perturbation of the signaling hub. The potential versatility of this tool puts it in prime position to study signaling at a multitude of other subcellular regions such as the plasma membrane or the mitochondria, thus refining our understanding of localized signaling and ushering in a new phase of targeted pharmacology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

The authors thank members of the laboratory of A.C.N. for helpful discussions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R35 GM122523 (to A.C.N.). A.T.K. was supported in part by a University of California San Diego Graduate Training Grant in Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology through the NIH Institutional Training Grant T32 GM007752 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest with the contents of this article.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Bhullar KS et al. (2018) Kinase-targeted cancer therapies: progress, challenges and future directions. Mol. Cancer 17, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fountas A. et al. (2015) Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and Diabetes: A Novel Treatment Paradigm? Trends Endocrinol. Metab 26, 643–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott JD and Pawson T (2009) Cell signaling in space and time: where proteins come together and when they’re apart. Science 326, 1220–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bucko PJ et al. (2019) Subcellular drug targeting illuminates local kinase action. Elife 8, e52220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keppler A. et al. (2003) A general method for the covalent labeling of fusion proteins with small molecules in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol 21, 86–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodor DL et al. (2102) Analysis of protein turnover by quantitative SNAP-based pulse-chase imaging. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol Chapter 8, Unit 8.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu GJ et al. (2013) Protein tag-mediated conjugation of oligonucleotides to recombinant affinity binders for proximity ligation. Nat. Biotechnol 30, 144–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Recker T. et al. (2011) Directed covalent immobilization of fluorescently labeled cytokines. Bioconjug. Chem 22, 1210–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joukov V and De Nicolo A (2018) Aurora-PLK1 cascades as key signaling modules in the regulation of mitosis. Sci. Signal 11, eaar4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maris JM et al. (2010) Initial testing of the aurora kinase A inhibitor MLN8237 by the Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program (PPTP). Pediatr. Blood Cancer 55, 26–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steegmaier M. et al. (2007) BI 2536, a potent and selective inhibitor of polo-like kinase 1, inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Curr. Biol 17, 316–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeLuca KF et al. (2018) Aurora A kinase phosphorylates Hec1 to regulate metaphase kinetochore-microtubule dynamics. J. Cell Biol 217, 163–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis-Davies GC (2007) Caged compounds: photorelease technology for control of cellular chemistry and physiology. Nat. Methods 4, 619–628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]