Abstract

Tortricidae is one of the largest families in Lepidoptera, including subfamilies of Tortricinae, Olethreutinae, and Chlidanotinae. Here, we assembled the gap-free genome for the subfamily Chlidanotinae using Illumina, Nanopore, and Hi-C sequencing from Polylopha cassiicola, a pest of camphor trees in southern China. The nuclear genome is 302.03 Mb in size, with 36.82% of repeats and 98.4% of BUCSO completeness. The karyotype is 2n = 44 for males. We identified 15412 protein-coding genes, 1052 tRNAs, and 67 rRNAs. We also determined the mitochondrial genome of this species and annotated 13 protein-coding genes, 22 tRNAs, and one rRNA. These high-quality genomes provide valuable information for studying phylogeny, karyotypic evolution, and adaptive evolution of tortricid moths.

Subject terms: Genome, Sequence annotation

Background & Summary

Tortricidae, the leafroller moths, is one of the largest families of Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths)1, including numerous notorious economic pests such as the spruce budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana2, oriental fruit moth Grapholita molesta3 and codling moth, Cydia pomonella4. The two main subfamilies are Tortricinae and Olethreutinae, which are relatively young5, comprising over 95% of tortricid species. Genomes of many species in these two subfamilies have been determined6, revealing an ancestral sex chromosome-autosome fusion and two subsequent autosome fusions relative to the ancestral karyotype of Lepidoptera7. Compared to the two successful subfamilies, the relict subfamily Chlidanotinae is much more limited in distribution range, host range, species richness, and population size. Species of this subfamily are mainly distributed in tropical regions, indicating varied climatic adaptability compared to species of the other subfamilies. Thus, this group can provide valuable insights into the phylogeny and pest adaptation and evolution of Tortricidae. However, no genome has been assembled for species of Chlidanotinae.

Here, we present the first chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation in the Olethreutinae using high-coverage long-read and Hi-C sequencing from Polylopha cassiicola8. This species is mainly distributed in the southern coastal regions of China and Southeast Asia. It is a pest of trees Cinnamomum cassia and C. camphora. We also assembled the mitochondrial genome of this species from the Illumina short sequencing reads. These genomes are expected to provide information for understanding the phylogeny, karyotypic, and adaptive evolution of Tortricidae.

Methods

Sample collection and sequencing

P. cassiicola larvae were collected from the tops of C. camphora in Guangxi, China. The larvae were reared in the laboratory to pupae and adults for genomic and transcriptome sequencing. Three individuals were used for three types of genome sequencing: one male pupae for Nanopore long-read sequencing, one male pupae for Illumina short-read sequencing, and one female adult for Hi-C sequencing. In addition, four larvae were used for RNA sequencing. Nucleic acid extraction and sequencing libraries was contracted by BerryGenomic (Beijing, China). Methods for nucleic acid extraction, platforms for sequencing, and sequencing outputs are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Methods and outputs for sequencing experiments.

| Experiment | Method/Platform | Manufacturer | Insertion size | Output | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA extraction | Magnetic bead method | Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA | NA | NA | NA |

| RNA extraction | TRIzol reagent | Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA | NA | NA | NA |

| Short-read seq | NovaSeq 6000; paired-end | Illumina, USA | 350 bp | 68.7 Gb | 115× |

| Long-read seq | PromethION | Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK | N50 = 16.7 Kb | 117.6 Gb | 196× |

| Hi-C seq | NovaSeq 6000; paired-end; digested by MboI | Illumina, USA | 350 bp | 178.1 Gb | 297× |

| RNA seq | NovaSeq 6000; paired-end | Illumina, USA | 350 bp | 16.3 Gb | NA |

NA, not available.

Genome assembly

The Nanopore long reads were assembled into 76 contigs using NextDenovo 2.5.2 (https://github.com/Nextomics/NextDenovo) with parameters: “read_cutoff = 4k, genome_ size = 400 m, nextgraph_options = -a 1”. Redundant sequences in contigs were removed using Purge_dups9. The cleaned contigs containing 65 sequences were then assembled to chromosome-level using Hi-C information. In this analysis, we mapped the Hi-C reads to cleaned contigs using BWA10 with options: “mem -SP5”, anchored contigs using YaHS 1.2a.111 with option: “-e GATC”, and manually adjusted using Juicerbox 1.22.0112. We removed the contigs that did not have any contact information with the chromosomes, which could be from potential contamination, such as symbiotic microbes. At last, the chromosomal-level genomic sequences were subjected to two rounds of long-read polishing and two rounds of short-read polishing using Nextpolish 1.4.113. The obtained P. cassiicola genome is 302.03 Mb in size and contains 21 autosomes and one Z sex-chromosome (Fig. 1a).

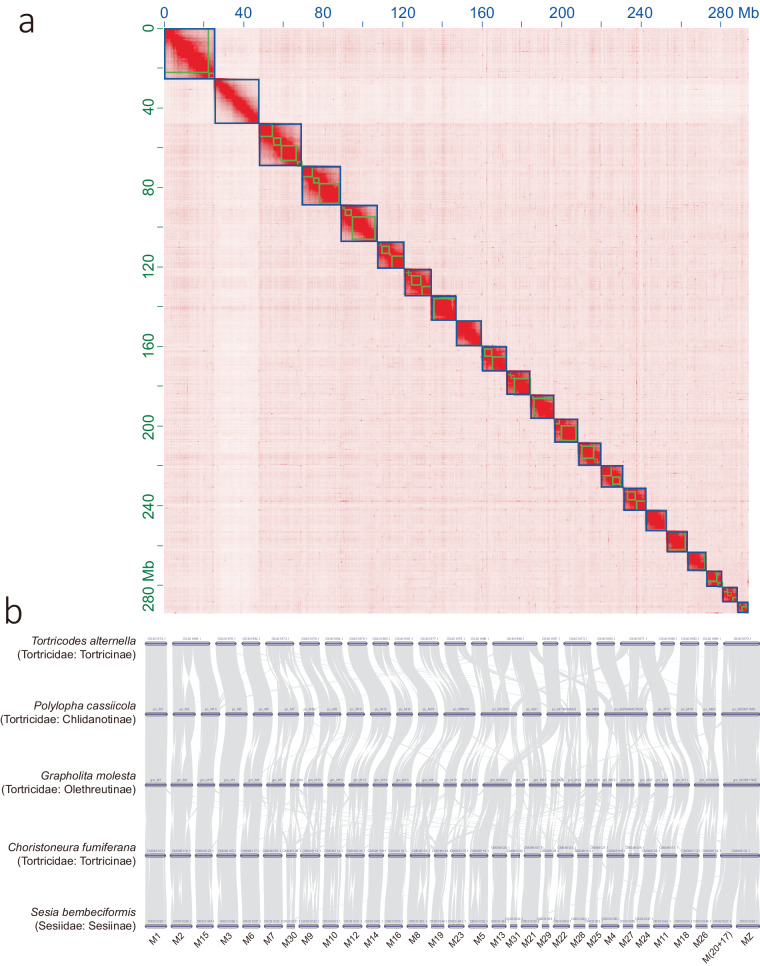

Fig. 1.

Genomic feature of nuclear genome of Polylopha cassiicola. (a) Hi-C contact matrix of 22 putative chromosomes. (b) Synteny among four tortricid species from four subfamilies and an outgroup. The labels at the bottom marked the ancestral linkage groups of Lepidoptera6.

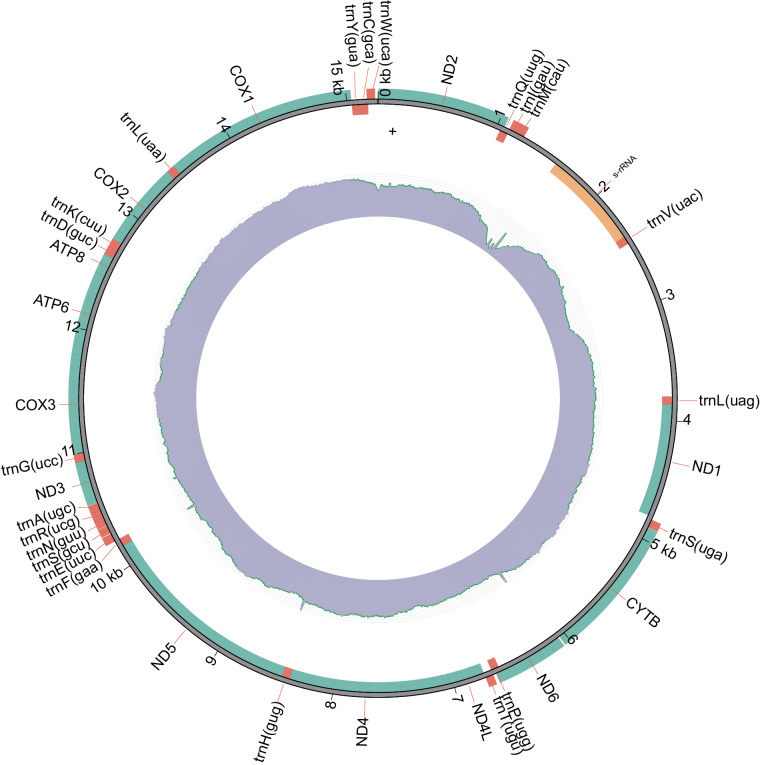

We also assembled mitochondrial genome using MitoZ 3.614 based on the short-reads. In the mitochondrial genome, we identified 13 protein-coding genes, 22 tRNAs, and 1 rRNA (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of annotated genes on mitochondrial genome. The inner ring shows the relative read coverage.

Genome synteny

We analysed the chromosomal synteny between P. cassiicola and three other species from Tortricidae and one from Sesiidae: Choristoneura fumiferana (Tortricidae: Tortricinae)2, Grapholita molesta (Tortricidae: Olethreutinae)3, Tortricodes alternella (Tortricidae: Tortricinae; NCBI GenBank assembly: GCA_947859335.115), and Sesia bembeciformis (Sesiidae: Sesiinae)16. Synteny analysis was conducted using MSCANX pipeline in JCVI utility libraries17. We assigned names of the ancestral linkage group in Lepidoptera6 (Merian elements, M1-31 and MZ) based on chromosomal homology. The results show different patterns of chromosomal fusion in species T. alternella and P. cassiicola (Fig. 1b).

Repeat element and non-coding RNA annotation

Repeat elements were detected using RepeatMasker 4.1.518 with options “-no_is -norna -xsmall -q”. This analysis was conducted against three databases: Repbase (http://www.girinst.org), Dfam database1 specific to Arthropoda, and a species-specific repeat library constructed using RepeatModeler219. Transfer RNA (tRNA) was predicted by tRNAscanSE 2.0.1220 with default parameters, and ribosome RNA (rRNA) was predicted using Barrnap 0.9 (https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap). In the P. cassiicola genome, 36.82% of bases were annotated as repeat elements (Table 2). We identified 67 rRNAs, and 1052 tRNAs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistics of repeat elements and non-coding RNAs in Polylopha cassiicola genome.

| Item | Number | Length (bp) | Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SINEs | 5219 | 354577 | 0.12 |

| LINEs | 143490 | 16636355 | 5.51 |

| LTR elements | 35392 | 11777710 | 3.9 |

| DNA transposons | 23636 | 4498331 | 1.49 |

| Rolling-circles | 315217 | 39695809 | 13.14 |

| Unclassified repeats | 235177 | 34162427 | 11.31 |

| Satellites | 17 | 2222 | 0 |

| Simple repeats | 72367 | 3737369 | 1.24 |

| Low complexity repeats | 7520 | 355233 | 0.12 |

| rRNAs | 67 | 46500 | 0.015 |

| tRNAs | 1052 | 78802 | 0.026 |

SINEs, short interspersed nuclear elements; LINEs, long interspersed nuclear elements; LTR, long terminal repeat.

Gene prediction and functional annotation

Gene structure was predicted using an ab initio method, Helixer21, with options: “–subsequence-length 320760–batch-size 6”, and with a pre-trained model for invertebrate “invertebrate_v0.3_m_0200”. Gene function, Gene Ontology (GO), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) items for predicted genes were annotated using eggNOG-Mapper22 web tools, against the eggNOG Database 5. A total of 15412 protein-coding genes were predicted, in which 12671 genes were functionally annotated.

Data Records

The Nanopore reads, Illumina reads, Hi-C reads, and RNA reads for P. cassiicola genome assembly were deposited at NCBI under Sequence Read Archive under accession number SRP47975923. The nuclear and mitochondrial genome assemblies were deposited in Genbank under accession number GCA_038024825.124. The genome annotation files are available in Figshare25 at 10.6084/m9.figshare.24902046.

Technical Validation

To validate the accuracy of the final genome assembly, we mapped the Illumina short reads and Nanopore long reads to the P. cassiicola genome using Minimap226 with option “-ax sr” for short reads and option “-ax map-ont” for long reads. The mapping rates for the short reads and long reads were calculated using Samtools27. Analysis revealed 96.38% and 98.73% mapping rates for the short and long reads, respectively. We examined the coverage of short reads along the mitochondrial genome and showed 100% coverage (Fig. 1b).

Completeness of the assembly and gene prediction were evaluated using BUSCO 5.4.728 with lepidoptera_odb10 database. In this analysis, BUSCO examined the states and proportions of 5,286 single-copy orthologous of Lepidoptera in our genome assembly: single-copy (S), duplication (D), fragment (F), and missing (M). The analyses showed completeness ranging 95.1%–98.4% for each assembly stage (Table 3), and 97.8% for predicted gene set: “C: 97.8% [S: 97.2%, D: 0.6%], F: 0.9%, M: 1.3%”. Quality of gene prediction was manually evaluated using RNA-seq data. Specifically, RNA-seq reads were mapped to the genome using Hisat29 and Samtools27. We imported the obtained BAM file and annotation file into the IGV browser30. Based on manual examination, we found that the machine learning-based annotation method has predicted a near-complete gene structure. These results indicate that we have obtained a high-quality assembly and annotation for P. cassiicola genome.

Table 3.

Statistics of Polylopha cassiicola assemblies.

| Item | Contig | Purged contig | Hi-C raised scaffold | Polished scaffold |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of contigs | 76 | 65 | 22 | 22 |

| Size (Mb) | 297.20 | 294.45 | 294.46 | 302.03 |

| N50 (Mb) | 8.54 | 8.54 | 12.96 | 13.19 |

| GC content | 35.16% | 35.12% | 35.12% | 35.14% |

| Single-copy BUSCOs | 94.7% | 94.8% | 94.9% | 98.1% |

| Duplicated BUSCOs | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Fragmented BUSCOs | 2.2% | 2.2% | 2.2% | 0.3% |

| Missing BUSCOs | 2.6% | 2.7% | 2.6% | 1.3% |

Acknowledgements

We thank Ming-Liang Li for his help in sample collection. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (32070464 and 32272543), Program of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences (JKZX202208), and Beijing Key Laboratory of Environmentally Friendly Management on Pests of North China Fruits (BZ0432).

Author contributions

S.W. designed the study. L.C., Y.Y. and J.C. contribute to the materials of this study. F.Y. and W.S. analysed the data. F.Y. wrote the manuscript. S.W. revised the manuscript.

Code availability

No custom scripts or code were used in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.van der Geest, L. P. S. & Evenhuis, H. H. Tortricid Pests: Their Biology, Natural Enemies, and Control. vol. 5 (Elsevier, 1991).

- 2.Béliveau C, et al. The spruce budworm genome: reconstructing the evolutionary history of antifreeze proteins. Genome Biol. Evol. 2022;14:evac087. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evac087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao L-J, et al. Population genomic signatures of the oriental fruit moth related to the Pleistocene climates. Communciations Biol. 2022;5:142. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-03097-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wan F, et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of Cydia pomonella provides insights into chemical ecology and insecticide resistance. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4237. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12175-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagua G, Condamine FL, Horak M, Zwick A, Sperling FAH. Diversification shifts in leafroller moths linked to continental colonization and the rise of angiosperms. Cladistics. 2017;33:449–466. doi: 10.1111/cla.12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright, C. J., Stevens, L., Mackintosh, A., Lawniczak, M. & Blaxter, M. Comparative genomics reveals the dynamics of chromosome evolution in Lepidoptera. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1–14 10.1038/s41559-024-02329-4 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Šíchová J, Nguyen P, Dalíková M, Marec F. Chromosomal evolution in tortricid moths: conserved karyotypes with diverged features. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e64520. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nasu Y. Lopharcha moriutii, sp. nov. and Polylopha cassiicola Liu & Kawabe (Lepidoptera, Tortricidae, Chlidanotinae, Polyorthini) from Thailand and Hong Kong. Zootaxa. 2006;1369:55–61. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.1369.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guan D, et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:2896–2898. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou C, McCarthy SA, Durbin R. YaHS: yet another Hi-C scaffolding tool. Bioinformatics. 2023;39:btac808. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durand NC, et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 2016;3:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu J, Fan J, Sun Z, Liu S. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:2253–2255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meng G, Li Y, Yang C, Liu S. MitoZ: a toolkit for animal mitochondrial genome assembly, annotation and visualization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:e63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wellcome Sanger Institute. 2023. Genbank. GCA_947859335.1

- 16.Boyes, D. & Langdon, W. B. V. The genome sequence of the Lunar Hornet, Sesia bembeciformis (Hübner 1806). Wellcome Open Res8, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Tang H, et al. Synteny and Collinearity in Plant Genomes. Science. 2008;320:486–488. doi: 10.1126/science.1153917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 2009;25:4.10.1–4.10.14. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flynn JM, et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117:9451–9457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1921046117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan PP, Lin BY, Mak AJ, Lowe TM. tRNAscan-SE 2.0: improved detection and functional classification of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:9077–9096. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stiehler F, et al. Helixer: cross-species gene annotation of large eukaryotic genomes using deep learning. Bioinformatics. 2021;36:5291–5298. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantalapiedra CP, Hernández-Plaza A, Letunic I, Bork P, Huerta-Cepas J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021;38:5825–5829. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP479759

- 24.2024. Genbank. GCA_038024825.1

- 25.Yang F, Wei S-J. 2023. Genome annotation of Polylopha cassiicola. figshare. [DOI]

- 26.Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:3094–3100. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danecek P, et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience. 2021;10:giab008. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giab008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manni M, Berkeley MR, Seppey M, Simão FA, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO update: Novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021;38:4647–4654. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, Salzberg SL. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:907–915. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson JT, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Wellcome Sanger Institute. 2023. Genbank. GCA_947859335.1

- 2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP479759

- 2024. Genbank. GCA_038024825.1

- Yang F, Wei S-J. 2023. Genome annotation of Polylopha cassiicola. figshare. [DOI]

Data Availability Statement

No custom scripts or code were used in this study.