Abstract

Study design

Randomised controlled trial with computerised allocation, assessor blinding and intention-to-treat analysis.

Objective

This study wanted to prove that cervicocranial flexion exercise (CCFE) and superficial neck flexor endurance training combined with common pulmonary rehabilitation is feasible for improving spinal cord injury people’s pulmonary function.

Setting

Taoyuan General Hospital, Ministry of Health and Welfare: Department of Physiotherapy, Taiwan.

Method

Thirteen individuals who had sustained spinal cord injury for less than a year were recruited and randomised assigned into two groups. The experimental group was assigned CCFEs and neck flexor endurance training plus normal cardiopulmonary rehabilitation. The control group was assigned general neck stretching exercises plus cardiopulmonary rehabilitation. Lung function parameters such as forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), FEV1/FVC, peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR), inspiratory capacity (IC), dyspnoea, pain, and neck stiffness were recorded once a week as short-term outcome measure.

Result

The experimental group showed significant time effects for FVC (pre-therapy: 80.4 ± 21.4, post-therapy: 86.9 ± 16.9, p = 0.021, 95% CI: 0.00–0.26) and PEFR (pre-therapy: 67.0 ± 33.4; post-therapy: 78.4 ± 26.9, p = 0.042, 95% CI: 0.00–0.22) after the therapy course. Furthermore, the experimental group showed significant time effects for BDI (experimental group: 6.3 ± 3.0; control group: 10.8 ± 1.6, p = 0.012, 95% CI: 0.00–0.21).

Conclusion

The exercise regime for the experimental group could efficiently increase lung function due to the following three reasons: first, respiratory accessory muscle endurance increases through training. Second, posture becomes less kyphosis resulting increasing lung volume. Third, the ratio between superficial and deep neck flexor is more synchronised.

IRB trial registration

TYGH108045.

Clinical trial registration

Subject terms: Rehabilitation, Spinal cord diseases

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a central nervous system (CNS) disease caused by various accidents such as falls. It might lead to extremities disability and even respiratory damage [1–3]. Respiratory dysfunction might result in an elevated risk of pulmonary complications such as pneumonia, secretion retention and atelectasis [4, 5], and might further cause other morbidities, mortality and an economic burden [6]. The degree of respiratory function impairment is determined by the level of injury, completeness of injury and onset time from injury [7]. Acute SCI is defined by an onset within 12–18 months [8]. Respiratory challenges tend to occur during this period. According to a previous published articles, people with high-level spinal cord injury might suffer from severe lung capacity loss [9]. This can be attributed to the paralysis of other muscles of inspiration (inspiratory intercostals and scalenes) [10, 11]. People with lower level spinal cord injury might also suffer certain level of lung capacity loss [9]. It has been speculated that the major expiratory muscles (abdominals and expiratory intercostals) and inspiratory intercostals will be damaged [10, 11]. The residual volume (RV) relatively increases because of an undermined expiratory musculature and subsequent reduced expiratory reserve volume [12]. Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) also declines owing to increase in expiratory and inspiratory muscle dysfunctions and respiratory tract resistance [13]. A recent study also reported that plasma CRP and IL-6 levels in individuals with chronic SCI were inversely associated with FEV1, thereby indicating that a worse pulmonary function is associated with a higher inflammation [14]. Furthermore, some patients experienced dyspnoea during their daily activities [15]. Some studies reported the imbalance between capacity of and demand for respiratory function enhances the risk of respiratory muscle fatigue, dyspnoea and exercise intolerance [16, 17]. Hence, the treatment goals for SCI people are to train their residual respiratory function to an optimal level and prevent further respiratory complications and dyspnoea.

Pulmonary rehabilitation comprises respiratory muscle and cough ability training, and has been proven to be necessary and effective for patients with SCI. Based on previous studies, respiratory muscle training including the diaphragm and intercostal muscles can enhance respiratory muscle strength and endurance, pulmonary function such as vital capacity (VC), TLC and FEV1 and ameliorate respiratory complications [18, 19]. Furthermore, cough ability training is also important because it can assist patients in sputum clearance and air tract hygiene maintenance [20, 21]. According to Reid et al., studies examining insufflation combined with manually assisted cough provided the most consistent, high-level evidence of secretion removal [21].

Besides pulmonary rehabilitation, respiratory accessory muscle courses are also essential for some patients with SCI who are either in the acute stage or with high-level lesions (above C3) [22]. Accessory muscles such as the anterior scalene(AS), sternocleidomastoid (SCM), pectoralis and trapezius, can compensate for the lost diaphragm and intercostal muscle functions [23, 24]. Nevertheless, one tends to experience fatigue from an excessive use of accessory muscles. Moreover, an overuse of the neck accessory muscle may cause neck pain and discomfort [25, 26]. Therefore, augmentation of the endurance and strength of these muscles can be regarded as a treatment goal for patients with acute SCI.

Cervicocranial flexion exercise (CCFE) and superficial neck flexor endurance training have been widely implemented in clinical practice for treating chronic neck pain [27]. By means of CCFE, the muscle balance between the deep and superficial neck flexors would become optimal during neck movement. In other words, the superficial neck flexor (scalenes, SCM and trapezius) would not be overactive, and the fatigue threshold might increase [28–30]. Superficial neck flexor endurance training has been proven to be efficient in reducing superficial cervical flexor muscle fatigue and increasing cervical flexion strength [25].

CCFE and superficial neck flexor endurance training are also beneficial for pulmonary function due to the training of the respiratory accessory muscles (scalenes and SCM). Hence, this study hypothesised that CCFE and superficial neck flexor endurance training combined with common pulmonary rehabilitation will show better outcomes (in terms of pulmonary function, dyspnoea, pain and neck stiffness) than pulmonary rehabilitation alone.

The research questions were as follows:

Does CCFE and superficial neck flexor endurance training combined with common pulmonary rehabilitation manifest better lung function than pulmonary rehabilitation alone?

Does CCFE and superficial neck flexor endurance training combined with common pulmonary rehabilitation result in less dyspnoea than pulmonary rehabilitation alone?

Does CCFE and superficial neck flexor endurance training combined with common pulmonary rehabilitation lead to less pain and stiffness than pulmonary rehabilitation alone?

Method

Design

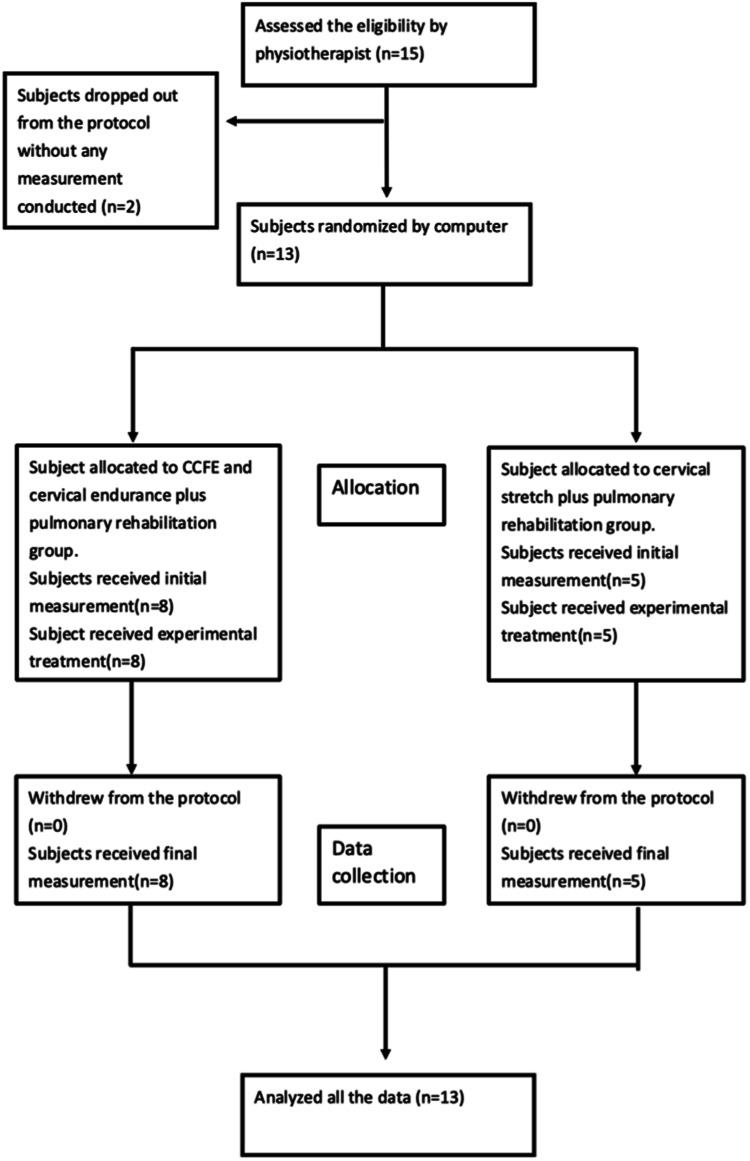

The participants included in this study were randomly assigned to the experimental and control groups. The randomisation orders were processed computationally, and all contents were concealed into a dark-coloured envelope. Before the first treatment, initial measurements were performed, including lung capacity test, level of dyspnoea, level of pain and level of neck stiffness. Lung functions, such as forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1, FVC/FEV1, peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) and inspiratory capacity (IC), were recorded. Subsequently, the envelopes were opened to reveal the treatment protocol. The experimental group received CCFE and neck flexor endurance training plus routine cardiopulmonary rehabilitation. The control group received general neck stretching exercises plus routine cardiopulmonary rehabilitation. The respective treatment protocols lasted for 30 min, 10 times a month. Upon completion, final measurements were performed as same process as the initial treatment (Fig. 1). The study protocol was registered on Clinical Trial.gov (NCT04500223).

Fig. 1. CONSORT flow diagram.

Flow chart of the experiment process.

Participants, therapists

Thirteen participants (Table 1) were recruited between March 2020 and February 2021 for this study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) SCI onset within a year; (2) motor level above T12 and American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) grades A, B, C or D; (3) age from 20 to 70 years; and (4) FEV1 ≤ 85% of prediction value. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) ventilation dependence; (2) tracheostomy; (3) psychiatric conditions; (4) progressive diseases; (5) infections; (6) cancer; and (7) inability to speak Mandarin or English.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

| Participant | Group | Sex | Neurological level | AIS class | Age (years) | Height (cm) | FVC Pred (l) | FEV1 Pred (l) | FEV1/FVC Pred (%) | PEFR (l/second) | IC (l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Exp | M | C5 | D | 70 | 166 | 3.09 | 2.42 | 77 | 6.37 | 3.18 |

| 2 | Exp | F | C2 | C | 75 | 145 | 1.63 | 1.17 | 79 | 4.57 | 1.65 |

| 3 | Exp | M | C5 | D | 33 | 176 | 4.40 | 3.84 | 85 | 10.02 | 3.87 |

| 4 | Exp | M | C4 | C | 52 | 168 | 3.66 | 3.05 | 81 | 8.06 | 3.08 |

| 5 | Exp | F | C3 | C | 73 | 158 | 1.96 | 1.48 | 79 | 4.9 | 2.10 |

| 6 | Exp | F | C4 | C | 60 | 155 | 2.29 | 1.86 | 82 | 5.22 | 1.88 |

| 7 | Exp | M | C4 | D | 56 | 170 | 3.56 | 2.92 | 80 | 7.69 | 3.29 |

| 8 | Exp | M | C4 | D | 38 | 179 | 4.44 | 3.82 | 84 | 9.82 | 3.89 |

| 9 | Con | M | C3 | D | 65 | 170 | 3.37 | 2.69 | 78 | 7.02 | 3.21 |

| 10 | Con | M | C4 | C | 58 | 180 | 4.07 | 3.35 | 80 | 8.37 | 3.52 |

| 11 | Con | M | C3 | D | 60 | 172 | 3.60 | 2.93 | 79 | 7.6 | 3.54 |

| 12 | Con | M | C5 | C | 70 | 160 | 2.73 | 2.12 | 77 | 5.9 | 2.73 |

| 13 | Con | F | C7 | D | 69 | 149 | 1.88 | 1.43 | 80 | 4.86 | 1.56 |

AIS Abbreviated Injury Scale, Con control, Exp experimental, F female, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, FVC forced vital capacity, IC inspiratory capacity, M male, F female, PEFR peak expiratory flow rate, Pred predicted, l litre.

The therapist who administered all the treatment protocols had 3 years of experience in treating neck conditions and ~1.5 years of experience in managing cardiopulmonary conditions. The therapist responsible for measuring outcomes had 1 year of experience in managing neck and cardiopulmonary conditions; the therapist was also blinded to the allocation process until the experiment was completed.

Intervention

The experimental group (Table 2) received CCFE and neck flexor endurance training plus routine cardiopulmonary rehabilitation. Participants were instructed to perform upper cervical spine retraction without excessive SCM contraction. CCFE was performed in a supine position. Participants were asked to hold their chin in proper position for 10 s per repetition, 10 repetitions per set, and 3 sets per treatment session [30]. The CCFE-experienced physiotherapist supervised all treatment processes to ensure the quality of execution. If participants did not show any uncomfortable or pain symptoms, neck endurance exercise is included in the treatment sessions. Neck endurance exercise was also conducted in a supine position. Participants were first taught to lift their head from a neutral upper cervical spine position. Afterwards, participants performed isometric exercise for 5–10 s depending on their ability of lifting their head off the bed about 0.5 cm. In the next stage, they were required to gradually move their head and neck as much as possible without inducing discomfort or neck-related symptoms. This exercise was performed for 12–15 repetitions depending on the participants’ condition [31]. If the participants were unable to reach the required training level, the bed was inclined upward from the horizontal position. Hence, the demands for lifting the neck and head declines, and participants are able to perform the assigned programme.

Table 2.

Training protocol for the experimental group.

| Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

CCFE Neck endurance exercise |

CCFE |

CCFE Neck endurance exercise (isometric) |

CCFE Neck endurance exercise (through range) |

| Dosage | 10 s × 10 reps × 3 sets |

10 s × 10 reps × 3 sets/ 5–10 s × 10 reps × 3 sets |

10 s × 10 reps × 3 sets/ 5–10 s × 10 reps × 3 sets |

| Pulmonary rehabilitation |

Diaphragm exercise Pursed-lip breathing Lateral costal breathing Cough training Rib mobilisation |

Coach Coach (breathing control) Upper extremity exercise with breathing |

Upper extremity exercise with Coach |

| Dosage | Dependent on the patients’ condition | 15 reps × 3 sets | 15 reps × 3 sets |

CCFE craniocervical flexion exercise, reps repetitions.

The pulmonary rehabilitation protocol was divided into three stages. In the first stage, participants lay in a supine position, and were instructed to perform diaphragmatic breathing, pursed-lip breathing, lateral costal breathing, cough training and rib mobilisation. The dosage and type of therapy depended daily on the participant’s condition. The total pulmonary training was fixed at 20 min. In the second stage, an incentive spirometer was integrated into the therapy. Participants were asked to inhale the air slowly while looking at the chamber of the spirometer to control the airflow velocity. Participants were also asked to inhale as much volumes as possible. The back support was inclined to hold the participant in a semi-sitting position. Participants performed 15 repetitions, with 20 s of rest in between each repetition. In addition, some upper extremity training combined with breathing exercise was also performed after the incentive spirometer training. Participants performed 3 sets of 15 repetitions were performed by the participants. In the third stage, upper extremity exercise was combined with spirometer training. Participants performed 3 sets of 15 repetitions. The experienced physiotherapist decided the stages depending on the patient’s capability; that is, the stages were not the same for each participant.

The control group was assigned neck stretch exercises plus pulmonary rehabilitation. The neck stretch exercises were performed by a physiotherapist before the cardiopulmonary training. Neck flexion, neck extension, left and right neck rotations and left and right neck sidebending were performed five times in each direction with the neck maintained at the end position for 30 s on each repetition.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

Lung capacity was evaluated by a doctor at the lung function examination centre of Taoyuan General Hospital using a lung spirometer. Parameters such as FVC, FEV1, IC and PEFR were recorded. A bronchodilator was not used prior to the examination to avoid interference with the measurement outcomes.

Secondary outcome

Dyspnoea was evaluated using the baseline dyspnoea index (BDI) and transition dyspnoea index (TDI) questionnaires. The BDI measures the severity of dyspnoea at baseline while the TDI measures the changes from baseline. Both questionnaires comprise three parts: functional impairment, magnitude of task and magnitude of effort required to evoke dyspnoea. Each part of the BDI has a score from 0 (very severe) to 4 (no impairment); a total score from 0 to 12 (the lower the score, the more severe the dyspnoea) was recorded [32]. The numeric pain rating scale (NRPS) was used to define the level of neck pain and stiffness. The minimum clinical important difference (MCID) of neck pain NRPS is 1 [33].

Data analysis

The primary variables of the study are vital capacity, respiratory complications and dyspnoea. The secondary variables of the study are FEV1, pain and neck stiffness. Descriptive statistics for categorical variables are presented as frequency counts and percentages. Continuous variables are reported as mean + SD, and all lung capacity values were normalised by their normal predicted values.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was adopted to analyse the scores before and after the treatment sessions (time effect). The Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyse the difference in scores before and after treatment between the two treatment groups (group effect). The baseline measurements of the two groups were also analysed using the Mann–Whitney U test. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.

Results

Basic demographic factors such as sex (p = 0.523), age (p = 0.578), height (p = 0.608) and American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) level (p = 0.529) were not significantly different between the two groups.

Lung function parameters

All the lung function parameters were normalised with its normal prediction value, and they would be presented as percentage of its normal prediction value. In line with the data on lung function including FVC, FEV1/FVC, FEV1, IC and PEFR, the experimental group showed better outcomes than the control group for most categories. While time effect was evidently significant in the experimental group after the therapy course for FVC (pre: 80.4% ± 21.5%, post: 86.9% ± 18.0%, p = 0.021, 95% CI: 0.00–0.26), no significant group difference was found. However, looking through the mean difference of FVC, the experimental group (6.5%) showed a larger change in treatment effect than the control group (2.4%) (p = 0.093, 95% CI: 0.00–0.35). Additionally, the experimental group revealed a significant time effect for PEFR (pre: 67.0% ± 33.4%, post: 78.4% ± 26.9%, p = 0.042, 95% CI:0.00–0.22), but no significant group effect was presented. From the raw PEFR mean difference, the experimental group (11.3%) showed a larger change in treatment effect than the control group (4.0%) (p = 0.171, 95% CI: 0.01–0.46) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Lung function parameters.

| Unit: % | Exp | Con | Time effect | Group effect | 95% CI interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FVC_pre (%) | 80.4 ± 21.5 | 77.2 ± 18.0 |

Exp: p = 0.021* Con: p = 0.500 |

p = 0.093 |

Exp: 0.00–0.26 Con: 0.35–0.88 Group: 0.00–0.35 |

| FVC_post (%) | 86.9 ± 18.0 | 79.6 ± 9.5 | |||

| FEV1_pre (%) | 81.0 ± 20.5 | 80.2 ± 17.0 |

Exp: p = 0.233 Con: p = 0.715 |

p = 0.435 |

Exp: 0.27–0.81 Con: 0.44–0.95 Group: 0.27–0.81 |

| FEV1_post (%) | 85.4 ± 15.2 | 82.2 ± 13.6 | |||

| FEV1/FVC_pre (%) | 100.1 ± 7.5 | 105.6 ± 10.5 |

Exp: p = 0.344 Con: p = 0.588 |

p = 0.833 |

Exp: 0.06–0.56 Con: 0.27–0.81 Group: 0.54–0.99 |

| FEV1/FVC_post (%) | 98.8 ± 11.3 | 103.6 ± 7.1 | |||

| PEFR_pre (%) | 67.0 ± 33.4 | 69.8 ± 16.4 |

Exp: p = 0.042* Con: p = 0.343 |

p = 0.171 |

Exp: 0.00–0.22 Con: 0.06–0.56 Group: 0.00–0.46 |

| PEFR_post (%) | 78.4 ± 26.9 | 73.8 ± 14.5 | |||

| IC_pre (%) | 57.3 ± 17.7 | 48.8 ± 12.4 |

Exp: p = 0.484 Con: p = 0.074 |

p = 0.833 |

Exp: 0.12–0.69 Con: 0.00–0.22 Group: 0.78–1.00 |

| IC_post (%) | 59.9 ± 21.5 | 52.0 ± 11.9 |

All lung function data were normalised to their predicted values.

Con control group, Exp experimental group, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, FVC forced vital capacity, Group group effect, IC inspiratory capacity, PEFR peak expiratory flow rate, pre pre-therapy, post post-therapy, CI confidence interval.

*Statistically significant.

Questionnaire

According to the BDI, NRPS stiffness, NRPS pain and the experiment data, the experimental group exhibited better outcomes than the control group among all the parameters. The experimental group showed significant time effect for BDI (pre: 6.3 ± 3.0; post: 10.8 ± 1.6, p = 0.012, 95% CI: 0.00–0.21) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Questionnaire of baseline dyspnoea index and numeric pain rating scale.

| Exp | Con | Time effect | Group effect | 95% CI interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI_pre | 6.1 ± 3.0 | 6.2 ± 1.6 |

Exp: p = 0.012 Con: p = 0.066 |

p = 0.119 |

Exp: 0.00–0.21 Con: 0.00–0.35 Group: 0.01–0.46 |

| BDI_post | 10.8 ± 1.6 | 8.4 ± 3.2 | |||

| NRPS_pain_pre | 1.9 ± 2.4 | 1.0 ± 2.2 |

Exp: p = 0.139 Con: p = 0.180 |

p = 0.763 |

Exp: 0.00–0.35 Con: 0.12–0.65 Group: 0.35–0.88 |

| NRPS_pain_post | 0.5 ± 1.1 | 0.6 ± 1.3 | |||

| NRPS_stiffness_pre | 1.5 ± 1.4 | 3.0 ± 4.1 |

Exp: p = 0.056 Con: p = 0.655 |

p = 0.313 |

Exp: 0.00–0.46 Con: 0.794–1.00 Group: 0.35–0.88 |

| NRPS_stiffness_post | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.6 ± 1.3 |

BDI baseline dyspnoea index, NRPS numeric pain rating scale, Con control group, Exp experimental group, Group group effect, pre pre-therapy, post post-therapy, CI confidence interval.

Discussion

Lung function loss, a common phenomenon among people with SCI, might cause lung complications and changes in an individual’s way of life [1–3]. Accessory muscles such as the SCM and AS might become more active to compensate for the loss of respiratory muscle function [23, 24].

The lung function results showed that CCFE and superficial neck flexor endurance training combined with routine pulmonary rehabilitation yielded better outcomes than only pulmonary rehabilitation for parameters such as FVC and PEFR. This finding is similar to that of a previous study targeting lung function maximal voluntary ventilation (MVV) in a chronic stroke group [34]. MVV can be predicted by multiplying FEV1 by 40 [35]. Although the experimental group did not show significant time and group effects in this study, a slightly better outcome was apparent in the experimental group than in the control group based on the difference value. The experimental group showed better FVC values than the control group because accessory muscles such as the scalene and SCM are not prone to fatigue. This result was similar to that of previous studies that reported that neck superficial muscle endurance increases in chronic neck pain groups. First, this indicates a reduction in myoelectric manifestations of the SCM and AS muscle fatigue in patients with neck pain [25, 26] and a change in the SCM and AS muscle types from type II to type I [36]. Second, studies on chronic neck pain reported that the posture of the upper body becomes less kyphotic [37], resulting in an increase in lung capacity [38]. Third, the EMG firing between the deep neck flexors and superficial neck muscles becomes more optimal; that is, more firing is observed in the deep neck flexors overactivity of the superficial neck muscles is inhibited; hence, the use of the neck muscles becomes more efficient [28–30].

The PEFR results can be considered as a criterion for airway obstruction and cough ability. Furthermore, the study participants had no history of obstructive lung disease. In order to achieve an effective cough, 85–90% lung insufflation is necessary to obtain the maximum expiratory flow [39]. Thus, the experimental group which manifested a significant time effect could be insinuating an improvement in the airway clearance function of the participant. This might be attributed to the strengthening of the inspiratory and expiratory accessory muscles [2]. According to previous studies, secretion removal ability could be enhanced by pulmonary function training due to the achievement of higher pre-cough volumes and a more effective cough for secretion clearance; thus, inspiratory muscle strength is also essential for patients with SCI. The improvement in SCM and AS endurance in the experimental group could explain the larger improvement in PEFR [40].

Regarding daily respiratory challenges, the BDI in the experimental group showed a significant time effect; thus, it is easier to perform daily functions without dyspnoea. Possible reasons for the improvement could be summarised as improvement in general lung function [18, 19] and anxiety relief due to breathing exercise [41].

The limitations of the study are as follows: first, the sample size was small and insufficient to observe a normal distribution. Second, the homogeneity of the SCI AIS class is difficult to control. Third, the treatment dosage may not be sufficient to obtain more significant parameters. Only 10 sessions of exercise could be performed in this study because the upper limit for the length of hospital stay in Taiwan is 30 days; this is less than that in similar studies (6–8 weeks). Finally, the participants also received other forms of neurophysiotherapy, and it was difficult to normalise and exclude their influences. More accurate and evidence-based tools such as the use of EMG on the inspiratory muscle and ultrasound for the diaphragm should be included in future studies.

In summary, the proposed exercise regime in this study might be effective in improving lung function and decreasing dyspnoea due to the following: first, endurance exercise training enhances the endurance of neck accessory muscles; second, the posture of SCI people becomes less kyphotic, thereby increasing the lung capacity; and third, muscle activation between the deep neck flexors and superficial neck muscles is more synchronised at an optimal ratio, thereby leading to more efficient use of the accessory muscles. In addition, CCFE and superficial neck flexor endurance training combined with common pulmonary rehabilitation might be appropriate for all levels of SCI because neck accessory muscles are almost innervated by cranial nerves, and the exercise protocol can easily be administered.

Author contributions

CS was involved in study design; collected the data; performed the data analysis; wrote and revised the article. HT help data collection; wrote and revised the article. WL and YT were involved in experiment preparation; wrote and revised the article. All authors approved and read the final version of the article.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due the hospital’s policy but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

All the research process was supervised and approved by the institutional board of Taoyuan General Hospital (Trial number: TYGH108045). We followed all the institutional and government regulation about ethic of human volunteers during the process of the experiment.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Burns AS, Marino RJ, Flanders AE, Flett H. Clinical diagnosis and prognosis following spinal cord injury. Handb Clin Neurol. 2012;109:47–62. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52137-8.00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown R, DiMarco AF, Hoit JD, Garshick E. Respiratory dysfunction and management in spinal cord injury. Respir Care. 2006;51:853–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller G, de Groot S, van der Woude L, Hopman MTE. Time-courses of lung function and respiratory muscle pressure generating capacity after spinal cord injury: a prospective cohort study. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:269–76. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fishburn MJ, Marino RJ, Ditunno Jr JF. Atelectasis and pneumonia in acute spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reines HD, Harris RC. Pulmonary complications of acute spinal cord injuries. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:193–6. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198708000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van den Berg MEL, Castellote JM, de Pedro-Cuesta J, Mahillo-Fernandez I. Survival after spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1517–28. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schilero GJ, Spungen AM, Bauman WA, Radulovic M, Lesser M. Pulmonary function and spinal cord injury. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;166:129–41. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fawcett JW, Curt A, Steeves JD, Coleman WP, Tuszynski MH, Lammertse D, et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury and statistical power needed for therapeutic clinical trials. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:190–205. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stepp EL, Brown R, Tun CG, Gagnon DR, Jain NB, Garshick E. Determinants of lung volumes in chronic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:1499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopman MT, van der Woude LH, Dallmeijer AJ, Snoek G, Folgering HT. Respiratory muscle strength and endurance in individuals with tetraplegia. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:104–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mateus SRM, Beraldo PS, Horan TA. Maximal static mouth respiratory pressure in spinal cord injured patients: correlation with motor level. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:569–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liaw MY, Lin MC, Cheng PT, Wong MK, Tang FT. Resistive inspiratory muscle training: its effectiveness in patients with acute complete cervical cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:752–6. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(00)90106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berlowitz DJ, Tamplin J. Respiratory muscle training for cervical spinal cord injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD008507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Hart JE, Goldstein R, Walia P, Merilee T, Antonio L, Carlos GT, et al. FEV1 and FVC and systemic inflammation in a spinal cord injury cohort. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17:113. doi: 10.1186/s12890-017-0459-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garshick E, Mulroy S, Graves D, Greenwald K, Horton JA, Morse LR. Active lifestyle is associated with reduced dyspnea and greater life satisfaction in spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:1721–7. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinderby C, Ingvarsson P, Sullivan L, Wickstrom I, Lindstrom L. Electromyographic registration of diaphragmatic fatigue during sustained trunk flexion in cervical cord injured patients. Paraplegia. 1992;30:669–77. doi: 10.1038/sc.1992.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor BJ, West CR, Romer LM. No effect of arm-crank exercise on diaphragmatic fatigue or ventilatory constraint in Paralympic athletes with cervical spinal cord injury. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:358–66. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00227.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Houtte S, Vanlandewijck Y, Gosselink R. Respiratory muscle training in persons with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Respir Med. 2006;100:1886–95. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin JC, Han EY, Cho KH, Im SH. Improvement in pulmonary function with short-term rehabilitation treatment in spinal cord injury patients. Sci Rep. 2019;9:17091. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52526-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin KH, Lai YL, Wu HD, Wang TQ, Wang YH. Cough threshold in people with spinal cord injuries. Phys Ther. 1999;79:1026–31. doi: 10.1093/ptj/79.11.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reid WD, Brown JA, Konnyu KJ, Rurak JME, Sakakibara BM. Physiotherapy secretion removal techniques in people with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:353–70. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2010.11689714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viroslav J, Rosenblatt R, Tomazevic SM. Respiratory management, survival, and quality of life for high-level traumatic tetraplegics. Respir Care Clin N Am. 1996;2:313–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.James WS, III, Minh VD, Minteer MA, Moser KM. Cervical accessory respiratory muscle function in a patient with a high cervical cord lesion. Chest. 1977;71:59–64. doi: 10.1378/chest.71.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Paleville DT, Lorenz D. Compensatory muscle activation during forced respiratory tasks in individuals with chronic spinal cord injury. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2015;217:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falla D, Jull G, Hodges P, Vicenzino B. An endurance-strength training regime is effective in reducing myoelectric manifestations of cervical flexor muscle fatigue in females with chronic neck pain. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:828–37. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falla D, Jull G, Rainoldi A, Merletti R. Neck flexor muscle fatigue is side specific in patients with unilateral neck pain. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:71–7. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(03)00075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borisut S, Vongsirinavarat M, Vachalathiti R, Sakulsriprasert P. Effects of strength and endurance training of superficial and deep neck muscles on muscle activities and pain levels of females with chronic neck pain. J Phys Ther Sci. 2013;25:1157–62. doi: 10.1589/jpts.25.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghaderi F, Jafarabadi MA, Javanshir K. The clinical and EMG assessment of the effects of stabilization exercise on nonspecific chronic neck pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2017;30:211–9. doi: 10.3233/BMR-160735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jull G, Falla D. Does increased superficial neck flexor activity in the craniocervical flexion test reflect reduced deep flexor activity in people with neck pain? Man Ther. 2016;25:43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2016.05.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jull GA, Falla D, Vicenzino B, Hodges PW. The effect of therapeutic exercise on activation of the deep cervical flexor muscles in people with chronic neck pain. Man Ther. 2009;14:696–701. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McArdle WD, Katch VL, Katch FI. Exercise physiology: Energy, nutrition, and human performance (2nd ed., Vol. 468–474). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins (1996).

- 32.Witek TJ, Jr, Mahler DA. Minimal important difference of the transition dyspnoea index in a multinational clinical trial. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:267–72. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00068503a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salaffi F, Stancati A, Silvestri CA, Ciapetti A, Grassi W. Minimal clinically important changes in chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity measured on a numerical rating scale. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:283–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee MH, Jang SH. The effects of the neck stabilization exercise on the muscle activity of trunk respiratory muscles and maximum voluntary ventilation of chronic stroke patients. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2019;32:863–8. doi: 10.3233/BMR-170839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell SC. A comparison of the maximum voluntary ventilation with the forced expiratory volume in one second: an assessment of subject cooperation. J Occup Med. 1982;24:531–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Falla D, Farina D. Neuromuscular adaptation in experimental and clinical neck pain. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2008;18:255–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suvarnnato T, Puntumetakul R, Uthaikhup S, Boucaut R. Effect of specific deep cervical muscle exercises on functional disability, pain intensity, craniovertebral angle, and neck-muscle strength in chronic mechanical neck pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Res. 2019;12:915–25. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S190125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zafar H, Albarrati A, Alghadir AH, Iqbal ZA. Effect of different head-neck postures on the respiratory function in healthy males. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:4518269. doi: 10.1155/2018/4518269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bach JR. Mechanical insufflation-exsufflation. Comparison of peak expiratory flows with manually assisted and unassisted coughing techniques. Chest. 1993;104:1553–62. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.5.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang SW, Shin JC, Park CI, Moon JH, Rha DW, Cho DH. Relationship between inspiratory muscle strength and cough capacity in cervical spinal cord injured patients. Spinal Cord. 2006;44:242–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deng G, Feinstein MB, Benusis L, Tin AL, Stover DE. Pilot study of self-care breath training exercise for reduction of chronic dyspnea. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2019;39:56–9. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due the hospital’s policy but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.