Abstract

Introduction/objective

Suppression of the SOS response in combination with drugs damaging DNA has been proposed as a potential target to tackle antimicrobial resistance. The SOS response is the pathway used to repair bacterial DNA damage induced by antimicrobials such as quinolones. The extent of lexA-regulated protein expression and other associated systems under pressure of agents that damage bacterial DNA in clinical isolates remains unclear. The aim of this study was to assess the impact of this strategy consisting on suppression of the SOS response in combination with quinolones on the proteome profile of Escherichia coli clinical strains.

Materials and methods

Five clinical isolates of E. coli carrying different chromosomally- and/or plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance mechanisms with different phenotypes were selected, with E. coli ATCC 25922 as control strain. In addition, from each clinical isolate and control, a second strain was created, in which the SOS response was suppressed by deletion of the recA gene. Bacterial inocula from all 12 strains were then exposed to 1xMIC ciprofloxacin treatment (relative to the wild-type phenotype for each isogenic pair) for 1 h. Cell pellets were collected, and proteins were digested into peptides using trypsin. Protein identification and label-free quantification were done by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC–MS) in order to identify proteins that were differentially expressed upon deletion of recA in each strain. Data analysis and statistical analysis were performed using the MaxQuant and Perseus software.

Results

The proteins with the lowest expression levels were: RecA (as control), AphA, CysP, DinG, DinI, GarL, PriS, PsuG, PsuK, RpsQ, UgpB and YebG; those with the highest expression levels were: Hpf, IbpB, TufB and RpmH. Most of these expression alterations were strain-dependent and involved DNA repair processes and nucleotide, protein and carbohydrate metabolism, and transport. In isolates with suppressed SOS response, the number of underexpressed proteins was higher than overexpressed proteins.

Conclusion

High genomic and proteomic variability was observed among clinical isolates and was not associated with a specific resistant phenotype. This study provides an interesting approach to identify new potential targets to combat antimicrobial resistance.

Keywords: SOS response, Escherichia coli, proteome profile, antimicrobial resistance, Enterobacteriaceae

Introduction

The SOS response is a conserved bacterial stress response triggered primarily by agents causing DNA damage, which includes specific antimicrobials such as fluoroquinolones. The SOS response is induced by activation of RecA protein, which binds to single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) fragments and triggers autoproteolysis of the SOS repressor, LexA, leading to the expression of genes under its control. Suppression of the SOS response by targeting RecA has been proposed as a promising strategic target to tackle antimicrobial resistance due to the multifunctional role of RecA protein involvement in DNA repair, recombination, induction of the SOS response, mutagenesis pathways, horizontal gene transfer, motility, and biofilm formation (Baharoglu and Mazel, 2014).

Previous studies, using in vitro and in vivo models, have demonstrated suppression of the SOS response as a strategy for sensitization and reversal of resistance to fluoroquinolones in laboratory strains and clinical isolates [including susceptible, low-level quinolone resistance (LLQR) and resistance phenotypes; Recacha et al., 2017, 2019; Machuca et al., 2021]. RecA inactivation resulted in up to 16-fold reductions in fluoroquinolone MICs and changes of clinical category, even in isolates belonging to the high-risk clone ST131 (Pitout and DeVinney, 2017), as well as a marked decrease in the development of resistance to these antimicrobials. These data provide further support for RecA inactivation as a promising strategy for increasing the efficacy of fluoroquinolones against susceptible and resistant clinical isolates, including high-risk clone isolates (Woodford et al., 2011; Mathers et al., 2015).

In addition, our group has shown that LLQR phenotypes significantly altered gene expression patterns in systems critical to bacterial survival and mutant development at clinically relevant concentrations of ciprofloxacin. Multiple genes involved in ROS modulation (the TCA cycle, aerobic respiration, and detoxification systems) were upregulated in LLQR mutants, and components of the SOS system were downregulated (Machuca et al., 2017).

Further studies are needed to comprehensively address the cellular and metabolic changes associated with bacterial sensitization when the SOS response is suppressed. It is also crucial to determine the extent of underexpression or overexpression of proteins from various pathways during treatment with inhibitory concentrations of fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin using clinical isolates, which will provide a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms of resistance and tolerance. To address this question, we used a large-scale proteomics approach to determine the relative protein expression levels using a set of well-characterized clinical isolates with different levels of resistance to ciprofloxacin (from susceptible to high levels of resistance). All isolates were compared with their isogenic mutants in which the SOS response was suppressed by disrupting recA gene expression (Machuca et al., 2021).

Materials and methods

Strains, growth conditions, and antimicrobial agents

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was the bacterial model for all experiments. Five E. coli clinical isolates, including two belonging to the high-risk clone ST131, harboring different combinations of chromosomally- and/or plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance mechanisms with susceptible, LLQR and resistance phenotypes were selected (Table 1; Briales et al., 2012; López-Cerero et al., 2013; Rodríguez-Martínez et al., 2016; Machuca et al., 2021). The SOS response was suppressed by recA gene knockout resistant to kanamycin, using a modified version of the method described by Datsenko and Wanner (2000) and Machuca et al. (2021). Liquid or solid lysogeny broth (LB; Invitrogen™, Madrid, Spain) medium and Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB; Oxoid, Madrid, Spain) were used. Strains were grown at 37°C. The antimicrobials used for the various assays were ciprofloxacin and kanamycin (Sigma–Aldrich, Madrid, Spain).

Table 1.

Genotype and susceptibility to ciprofloxacin of clinical isolates and their ∆recA mutants.

| Quinolone resistance genotypea | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | gyrA1 | gyrA2 | parC1 | parC2 | PMQR | STb | SOS response | CIPROFLOXACIN MICc | EUCAST clinical category | Fold change CIPROFLOXACINd | Source of reference |

| ATCC | - | - | - | - | - | ST73 | WT | 0.004 | S | ||

| ATCC ∆recA | - | - | - | - | - | ST73 | ∆recA | 0.001 | S | 4 | Recacha et al. (2017) |

| FI 4 | - | - | - | - | qnrB | ST73 | WT | 0.5 | ATU | ||

| FI 4 ∆recA | - | - | - | - | qnrB | ST73 | ∆recA | 0.06 | S | 8 | Machuca et al. (2021) |

| FI 10 | - | - | - | - | qnrB | ST93 | WT | 0.25 | S | ||

| FI 10 ∆recA | - | - | - | - | qnrB | ST93 | ∆recA | 0.016 | S | 15 | Machuca et al. (2021) |

| FI 19 | S83L | D87N | S80I | - | qnrS | ST1421 | WT | 4 | R | ||

| FI 19 ∆recA | S83L | D87N | S80I | - | qnrS | ST1421 | ∆recA | 2 | R | 2 | Machuca et al. (2021) |

| FI 20 | S83L | - | S80R | - | - | ST131 | WT | 0.5 | ATU | ||

| FI 20 ∆recA | S83L | - | S80R | - | - | ST131 | ∆recA | 0.125 | S | 4 | Machuca et al. (2021) |

| FI 24 | S83L | D87N | S80I | E84V | - | ST131 | WT | 32 | R | ||

| FI 24 ∆recA | S83L | D87N | S80I | E84V | - | ST131 | ∆recA | 4 | R | 8 | Machuca et al. (2021) |

aMechanisms of quinolone resistance. Resistance-associated mutations located in the GyrA and ParC proteins are defined as resistance mechanisms that alter the target site. PMQR, Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes. bSequence-type according to the MLST scheme of the University of Warwick (https://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/). cMIC (mg/L) of agents by microdilution broth. dFold reduction in MIC compared with the MIC of clinical isolates (wild-type SOS response). ATU, Area of Technical Uncertainty. S, susceptible. R, resistant.

Ciprofloxacin susceptibility testing

The susceptibility of each bacterial strain was determined in triplicate for each bacterial strain using the broth microdilution method, according to EUCAST guidelines. 1 Briefly, an inoculum of 5 × 105 CFU/mL of bacteria diluted in Mueller Hinton-Broth was exposed to twofold dilutions of ciprofloxacin. EUCAST 2023 (v13.0) clinical breakpoints were used for interpretation. Any change in MIC of at least two dilutions was considered significant. Clinical categories were established according to EUCAST breakpoints (Table 1; Machuca et al., 2021).

Whole genome sequencing

Whole-genome sequencing was performed to analyze the genomes of the 5 clinical isolates selected (FI 4, FI 10, FI 19, FI 20, and FI 24). Genomic DNA was extracted and sequenced on the MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States), and the library was prepared using the Nextera XT DNA library preparation kit (Illumina). Raw reads were quality filtered and assembled into contigs with CLC Genomics Workbench v.10.0 (Qiagen, Madrid, Spain). The average coverage was 50x. The resulting contigs were annotated with Prokka v. 1.14.5 (Seemann, 2014) using known proteins of E. coli ATCC 25922 from the UniProt release 2020_02 (The UniProt Consortium, 2018) as a reference database (“-proteins”), without removing the original annotation in case of conserved hypothetical proteins (“-rawproduct”), formatted according to NCBI standards (“-compliant -addgenes”) and annotating ncRNA elements using Rfam v. 14.1 (Kalvari et al., 2021; “-rfam”). ResFinder v.4.1 (Camacho et al., 2009; Zankari et al., 2017; Bortolaia et al., 2020) and MLST v.2. tools (Lemee et al., 2004; Bartual et al., 2005; Griffiths et al., 2010; Larsen et al., 2012) 2 were used to identify acquired resistance genes [using an identity threshold of 90% (Zankari et al., 2012)] and determine the sequence type of each isolate, respectively. The genome assemblies were analyzed with OrthoFinder v.2.5.2 software (Emms and Kelly, 2019) to classify gene sequences into conserved gene families. Proteomic data obtained from the annotated genomes of the clinical isolates and reference strain were used as input data for OrthoFinder to find all clusters of orthologous groups (“-M msa -oa”; Emms and Kelly, 2015, 2019). All strain sequences were deposited in a public repository under accession number PRJNA1015411.

Proteomics sample preparation

Escherichia coli strain ATCC 25922 and clinical isolates were grown at 37°C in LB medium to an OD600 of 0.5 (exponential phase). Cultures were diluted 10-fold in fresh LB. Ciprofloxacin was added to tubes at a final concentration of 1xMIC (relative to the wild-type MIC for each isogenic pair; Table 1). This concentration was sufficient to induce the relevant stress conditions without high lethality (Machuca et al., 2021) and allowed us at the same time to compare the cellular response to ciprofloxacin at identical absolute concentrations for each isogenic pair. All tubes were incubated at 37°C for 1 h with shaking. The remaining ciprofloxacin was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 2 min. After removal of the supernatant, an equivalent amount of fresh LB was added. Each experimental condition consisted of six independent replicates. One milliliter per sample was pelleted by centrifugation at 10.000 x g for 2 min. Cells were resuspended in 50 μL of TE (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA) containing chicken lysozyme (0.1 mg/mL, Sigma Aldrich, Germany) and incubated for 5 min at room temperature with occasional swirling. A 250 μL volume of denaturation buffer (6 M urea/2 M thiourea in 10 mM HEPES pH 8.0) was added to each sample, and 25 μL (corresponding to approximately 50 μg of total protein) of the resulting lysate was used for in-solution protein digestion, as described previously (Rappsilber et al., 2007). Briefly, the proteins were re-suspended in denaturation buffer and reduced by the addition of 1 μL of 10 mM DTT dissolved in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABC) and incubated for 30 min, followed by a 20-min alkylation reaction in the dark by the addition of 1 μL of iodoacetamide at a stock concentration of 55 mM. As a first digestion step, 0.5 μg of Lysyl endopeptidase (LysC, Wako, Japan), resuspended in 50 mM ABC, was added and incubated for 3 h. After pre-digestion with LysC, the protein samples were diluted by a factor of 4 with 50 mM ABC (to reduce the concentration of urea) and subjected to overnight trypsin digestion at room temperature using 1 μg of sequencing grade modified trypsin (Promega, United States), also diluted in 50 mM ABC. The digestion was stopped by acidification by adding 5% acetonitrile and 0.3% trifluoroacetic acid (final concentrations). Samples were micro-purified and concentrated using the Stage-tip protocol, described elsewhere (Rappsilber et al., 2007), and eluates were dried under vacuum.

Nano liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

Peptides were reconstituted in 20 μL of 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), 4% acetonitrile, and 5 μL were analyzed by an Ultimate 3,000 reversed-phase capillary nano liquid chromatography system connected to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were injected and concentrated on a trap column (PepMap100 C18, 3 μm, 100 Å, 75 μm i.d. × 2 cm, Thermo Fisher Scientific) equilibrated with 0.05% TFA in water. After switching the trap column inline, LC separations were performed on a capillary column (Acclaim PepMap100 C18, 2 μm, 100 Å, 75 μm i.d. × 25 cm, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at an eluent flow rate of 300 nL/min. Mobile phase A contained 0.1% formic acid in water, and mobile phase B contained 0.1% formic acid in 80% acetonitrile/20% water. The column was pre-equilibrated with 5% mobile phase B followed by an increase of 5%–44% mobile phase B in 100 min. Mass spectra were acquired in a data-dependent mode using a single MS survey scan (m/z 350–1,650) with a resolution of 60,000, and MS/MS scans of the 15 most intense precursor ions with a resolution of 15,000. The dynamic exclusion time was set to 20 s and automatic gain control was set to 3 × 106 and 1 × 105 for MS and MS/MS scans, respectively.

Data analysis

MS and MS/MS raw data were analyzed using the MaxQuant software package (version 2.0.3.0) with implemented Andromeda peptide search engine (Tyanova et al., 2016a). Data of the samples from strain ATCC 25922 were searched against the E. coli reference proteome downloaded from Uniprot (4,857 proteins, taxonomy 83,333, last modified 1 December 2019), while data of the samples from the 5 clinical isolates (FI 4, FI 10, FI 19, FI 20, and FI 24) were searched against individual databases generated from whole-genome sequencing as described above. The default parameters were used for MaxQuant except for enabling the options label-free quantification (LFQ) and match between runs. Filtering and statistical analysis was carried out for each strain individually using the software Perseus version 1.6.14 (Tyanova et al., 2016b). First, contaminants, reverse hits and ‘proteins only identified by site’ were removed from the dataset and protein LFQ intensities were log2 transformed. Next, two experimental groups (wild-type and recA mutant) were defined. Only proteins which were identified and quantified with LFQ intensity values in at least 3 (out of 6) experimental replicates (in at least 1/2 experimental groups) were included for downstream analysis. Missing protein intensity values were replaced from normal distribution (imputation) using the default settings in Perseus (width 0.3, down shift 1.8). Mean log2 fold protein LFQ intensity differences between experimental groups (recA mutant—wild-type) were calculated in Perseus using a student’s t-test with permutation-based FDR of 0.05 to generate the adjusted p-values (=q-values). Proteins with a minimum 2-fold change in their relative intensity (log2-fold change > 1 for recA or log2-fold change < −1 for wild-type) and a q-value < 0.05 were considered significantly changed. Heatmaps and volcano plots were used to represent the results, using GraphPad Prism 8 software (Boston, Massachusetts United States).3

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository (Perez-Riverol et al., 2022)4 with the dataset identifier PXD050358.

Results

Validation of ciprofloxacin susceptibility profiles

The phenotypic and genetic characteristics of the isolates are shown in Table 1 (Machuca et al., 2021).

Analysis of genomic profile of clinical isolates

In total, 5,569 genes were found among the five selected clinical isolates and reference strain ATCC 25922: 3376 of these were present in all genomes, and 3,311 genes in a single copy. The total number of genes encoded by each isolate was 4,834, 4,811, 4,683, 4,701, 4,853, and 4,842 for ATCC, FI 4, FI 10, FI 19, FI 20, and FI 24, respectively. Between each isolate and ATCC 25922, the total number of genes in common was 4,482 (93.2%), 3,705 (79.1%), 3,647 (77.6%), 4,035 (83.1%), 4,043 (83.5%) for FI 4, FI 10, FI 19, FI 20, and FI 24, respectively.

Known and potential SOS-regulated genes described previously by Fernández De Henestrosa et al. (2000) and Courcelle et al. (2001) were found in the genomes of the selected isolates. Twenty-six of the 32 genes known to be LexA-regulated genes were present in all isolates, including ATCC 25922: umuC, umuD, sbmC, recN, urvB, dinI, recA, sulA, uvrA, uvrB, ssb, yebG, lexA, dinF, ydjQ, ruvA, ruvB, molR, uvrD, dinG, yigN, ydjM, ftsK, dinB, ybfE, polB. In addition, six of the 20 genes were identified as potential LexA-regulated genes: ymgF, ydeO, yoaA, yoaB, glvB, ibpA (Courcelle et al., 2001). Consequently, most of the SOS-regulated genes in E. coli were represented in our collection.

Analysis of proteomic profile after treatment with ciprofloxacin

The protein expression of E. coli clinical isolates was compared with their isogenic pairs with suppressed SOS response under ciprofloxacin treatment at concentrations of 1xMIC relative to wild-type for 1 h.

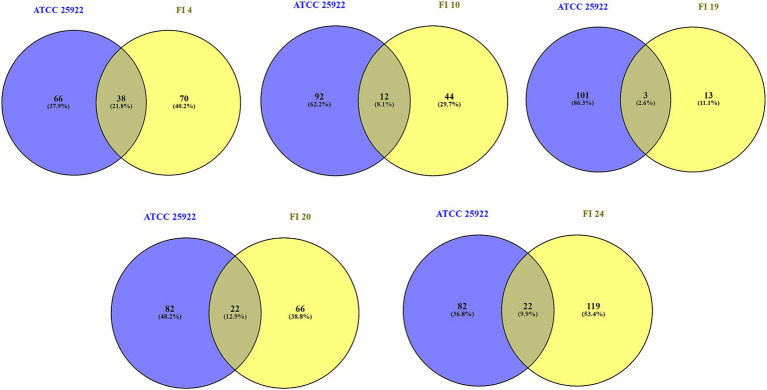

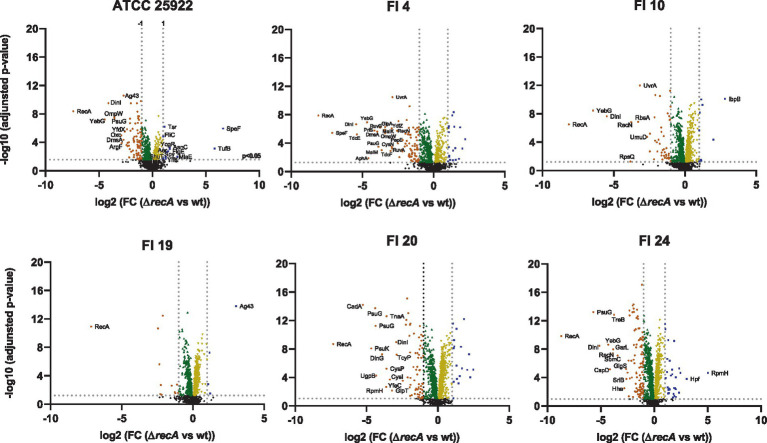

Significant changes in protein expression were found for 460/1,702 proteins (27%) in ATCC, 664/1,509 (44%) in FI 4, 831/1,637 (51%) in FI 10, 904/1,726 (52%) in FI 19, 1,210/1,786 (68%) in FI 20, and 1,227/1,706 (72%) in FI 24 (see Supplementary Tables 1–6). The number of proteins that exhibited at least a significant 2-fold increase or decrease of their relative abundance upon recA deletion are highlighted in Figure 1. The number of proteins decreased upon recA deletion are: 93 for ATCC, 89 for FI 4, 46 for FI 10, 12 for FI 19, 74 for FI 20, and 111 for FI 24. The number of proteins increased upon recA deletion are: 12 for ATCC, 20 for FI 4, 10 for FI 10, 4 for FI 19, 18 for FI 20, and 32 for FI 24. Proteins with significant expression changes were plotted for each isolate and compared to the ATCC 25922 control strain (Figure 2), showing a similarity ranging between 4 and 22%. Regarding significant protein expression after suppression of the SOS system, 10 (DinG, DinI, RecA, RecN, RuvA, RuvB, SbmC, UmuD, UvrA, YebG) out of 32 proteins known whose genes are regulated by LexA were underexpressed in at least one isolate, and no potential protein regulated by LexA was affected.

Figure 1.

Number of significantly over- and underexpressed proteins upon deletion of recA for ATCC 25922 and the five clinical isolates, with at least a 2-fold change in their relative abundance (log2 fold change >1 for increased and <−1 for decreased). Proteins were considered significantly changed with an adjusted p-value (=q-value) < 0.05. All experiments were done using 1xMIC concentration of ciprofloxacin.

Figure 2.

Overlap between differentially expressed proteins (log2 fold change >1 and <−1, p-value < 0.05) following exposure to ciprofloxacin (1xMIC relative to each wild-type) between isolates with suppressed SOS response relative to wild-type and the control strain in the same conditions. Venn diagrams show the overlap. Numbers on the diagram refer to the number of proteins with significantly altered expression levels. Susceptible phenotype: FI 10; LLQR phenotypes: FI 4 and FI 20; Resistant phenotype: FI 19 and FI 24.

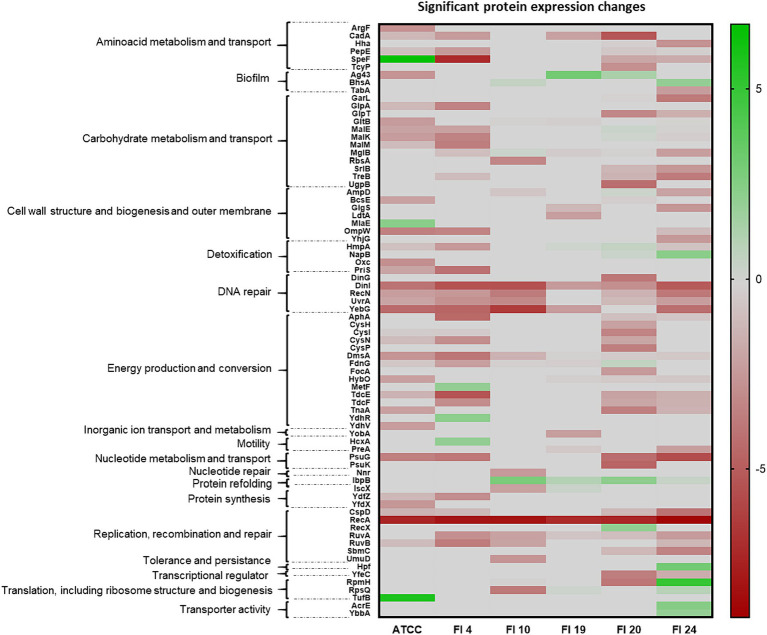

The relative protein intensity between the recA mutant and wild-type are shown in Figure 3 for ATCC 25922 and the five clinical isolates and proteins that exhibit a very strong change in their abundance upon recA deletion are labeled. Underexpressed proteins (log2 FC < −2.5) were: RecA (as control), YebG, DinI, OmpW, PsuG, Oxc, ArgF, Ag43, DmsA, YfdX (for strain ATCC); RecA, SpeF, DinI, TdcE, YebG, AphA, PriS, DmsA, PsuG, RuvB, MalM, MalK, OmpW, GlpA, TdcF, CysN, YdfZ, RuvA, UvrA, RecN, PepE (strain FI 4); RecA, YebG, DinI, RpsQ, RecN, RbsA, UvrA, UmuD (for strain FI 10); RecA (strain FI 19); RecA, CadA, PsuK, PsuG, UgpB, RpmH, DinG, YfeC, CysP, TnaA, CysI, GlpT, DinI, TcyP (strain FI 20) and RecA, PsuG, DinI, YebG, CspD, RecN, GarL, TreB, SbmC, Hha, GlgS, SrlB (strain FI 24). Overexpressed proteins (log2 FC > 2.5) were: SpeF, TufB (for the ATCC strain); IbpB (strain FI 10); Ag43 (strain FI 19), RpmH, Hpf (strain FI 24; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Proteome profile by strain. Orange: Proteins with log2 fold change (FC) < −1; Blue: Proteins with a log2 FC > 1; Green: Proteins with log2 FC = 0 to −1; Yellow: Proteins with log2 FC = 0 to 1. Black: no significant proteins (p > 0.05). Labeled proteins with log2 FC between >2.5 and < −2.5. wt, wild-type.

Protein expression under ciprofloxacin pressure was highly variable both among isolates and between isolates and the reference strain. No relationship was observed between protein expression and the quinolone resistance phenotype displayed by the different isolates. At the ciprofloxacin concentration used, underexpressed proteins were more numerous than overexpressed ones, and were mainly associated with processes of DNA repair (RecA, YebG, DinI, DinG, RuvA, RuvB, UvrA, RecN, UmuD, CspD, SbmC) and energy production and conversion (DmsA, TdcE, AphA, TdcF, CysI, CysN, CysP, TnaA). Overexpressed proteins were few and were involved in different cellular processes, such as amino acid metabolism (SpeF), translation (TufB, RpmH), protein refolding (IbpB) and biofilm formation (Ag43). Taken together, these results indicate that the treatment had a serious impact on cellular physiology.

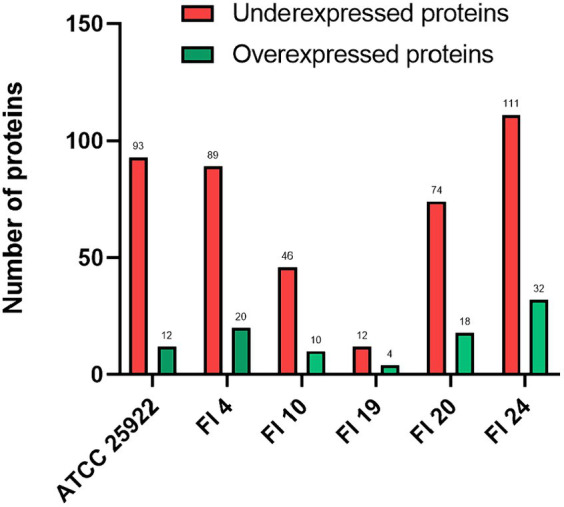

Functional analysis of the impact of the SOS suppression at the proteomic level

All proteins that showed as significant increase or decrease in their relative expression level upon recA deletion (log2 FC >2 or < −2) were analyzed in depth and classified by their function4 (Figure 4). Protein expression variations after treatment with ciprofloxacin most affected the following cellular functions: 15/76 (19.7%) proteins were involved in processes of energy production and conversion; 11/76 (14.5%) affected carbohydrate metabolism and transport; 7/76 (9.2%) were involved in replication, recombination and repair, cell wall and outer membrane structure and biogenesis; 6/76 (7.9%) proteins were involved in amino acid metabolism and transport, and 5/76 (6.6%) in DNA repair.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of relative protein expression based on label-free quantification by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC-MS). The main function associated with each protein is shown.

The following cellular processes were most affected and involved changes in expression of different proteins: energy production and conversion (AphA, CysH, CysI, CysN, CysP, DmsA, FdnG, FocA, HybO, MetF, TdcE, TdcF, TnaA, YdhR, YdhV); carbohydrate metabolism and transport (GarL, GlpA, GlpT, GltB, MalE, MalK, MalM, MglB, RbsA, SrlB, TreB, UgpB); replication, recombination and repair (CspD, RecA, RecX, RuvA, RuvB, SbmC, UmuD); cell wall and outer membrane structure and biogenesis (AmpD, BcsE, GlgS, LdtA, MlaE, OmpW, YhjG); amino acid metabolism and transport (ArgF, CadA, Hha, PepE, SpeF, TcyP) and DNA repair (DinG, DinI, RecN, UvrA, YebG; Figure 4).

Once again, the data indicate that the cellular abundance of a large number of proteins decreases under ciprofloxacin pressure in the absence of a functional SOS response.

Discussion

The SOS response is a conserved bacterial pathway mainly associated with DNA damage repair mechanisms. In this study, using a proteomic approach to study the expression levels of SOS response genes under treatment with a DNA damage-causing agent (ciprofloxacin), we showed significant changes in protein abundance at the cellular level and a correspondingly high variability in protein expression when the clinical isolates were each compared with their isogenic RecA-deficient partner.

The number of genes detected in the collection of selected isolates with different quinolone-resistant phenotypes and the ATCC 25922 reference strain was similar. However, the number of genes shared by each isolate with ATCC 25922 showed high intergenomic variability because clinical isolates were used instead of isogenic strains (as expected, strains ATCC 25922 and FI4, belonging to the same sequence type ST73, conserved the highest percentage of gene identity). High proteomic variability between isolates was also observed when the SOS response was suppressed after treatment with ciprofloxacin. In general, the result of this suppression was a large number of proteins with decreased cellular abundance under ciprofloxacin-induced pressure.

Sequential timing of promoter activation in the SOS response could impact bacterial physiology. Many changes in protein expression levels were probably not detected because exposure to ciprofloxacin in our assays was brief. An striking feature of the LexA/RecA regulatory circuit is that the timing, duration, and the induction level can vary for each LexA-regulated gene, depending on the location and binding affinity of the LexA box relative to the strength of the promoter. As a result, some genes may be partially induced in response to even endogenous levels of DNA damage, while others appear to be induced only when DNA damage to the cell is high or persistent (Courcelle et al., 2001; Culyba et al., 2018).

Despite the genomic and proteomic variability between isolates, the SOS response remained stable and conserved in all of them. In fact, most of the known genes regulated by the SOS system were identified in all isolates. As a result, the impact of suppression of the SOS response in the clinical isolates on sensitization and lethality was similar to that observed in laboratory strains (Recacha et al., 2017; Machuca et al., 2021). In previous studies, the impact of suppression of the SOS response in the presence of ciprofloxacin was analyzed in the clinical isolates that were selected for this study (Machuca et al., 2021). RecA inactivation resulted in 2 to 16-fold reductions in fluoroquinolone MICs, and a change in EUCAST clinical category for FI 4 (LLQR) and FI 20 (LLQR). In addition, a bactericidal effect (a > 3 log10 decrease in CFU/mL) was observed after short time intervals (2–8 h) against clinical isolates and their recA mutants. After 8 h, no viable bacteria were recovered for FI4 ΔrecA, FI20 ΔrecA, and FI24 ΔrecA. The results clearly showed that suppression of the SOS response in clinical isolates with LLQR, susceptible and resistance phenotypes to quinolones was detrimental to bacterial survival. The data in the present study indicate that, in addition to the proteins involved in the SOS response, the cellular abundance of a large number of proteins generally decreases under ciprofloxacin-induced pressure in the absence of a functional SOS response (Figure 1), and could contribute to an increased susceptibility and a decreased evolution of the E. coli isolates toward ciprofloxacin resistance mediated by suppression of the SOS response.

In another previous study by our group, which aimed to better understand the underlying molecular systems responsible for the reduction of bactericidal effect during antimicrobial therapy and to define new antimicrobial targets, the transcriptome profile of isogenic E. coli isolates harboring quinolone resistance mechanisms (LLQR phenotype) was evaluated in the presence of a clinically relevant concentration of ciprofloxacin (1 mg/L). In LLQR strains, a marked differential response to ciprofloxacin of either upregulation or downregulation was observed. Multiple genes involved in ROS modulation (related to the TCA cycle, aerobic respiration, and detoxification systems) were upregulated, and components of the SOS system were downregulated (Machuca et al., 2017).

In the present study, the number and type of proteins with significant differential expression in isolates with suppression of the SOS response varied among the isolates. Most of the significant proteins (p < 0.05) were underexpressed (Figure 3) and, of these, the most frequently underexpressed in the majority of the isolates (log2 FC < −3) were associated with replication, recombination, and DNA repair processes (DinI, YebG, RecN, UvrA, RuvA, RuvB, CspD; Yamanaka et al., 2001; Kreuzer, 2005); energy production and conversion (AphA, CysI, CysN, DmsA, HybO, TdcE, TdcF, TnaA) and amino acid (CadA, PepE, SpeF) carbohydrate (MglB, TreB) and nucleotide (PsuG) metabolism and transport processes (Karp et al., 2018). Notably, CadA (log2 FC to −5; inducible lysine decarboxylase) plays a role in pH homeostasis by consuming protons and neutralizing the acidic by-products of carbohydrate fermentation (Kanjee and Houry, 2013); DinI (log2 FC to −5; DNA damage-inducible protein I), involved in SOS regulation, inhibits RecA by preventing RecA from binding to ssDNA (Yasuda et al., 1998); YebG (log2 FC to −6; DNA damage-inducible protein) is involved in DNA repair (Lomba et al., 1997); TdcE (log2 FC to −5; 2-ketobutyrate formate-lyase/pyruvate formate-lyase 4) is responsible for transforming pyruvate into fumarate; PsuG (log2 FC to −6; pseudouridine-5′-phosphate glycosidase) is involved in the catabolism of pseudouridine (Preumont et al., 2008). Of note among the overexpressed proteins is IbpB (small heat shock protein), which was upregulated in most strains and associated with misfolded protein repair (Piróg et al., 2021). Other relevant proteins that were overproduced in individual isolates were Ag43 (log2 FC = 3), which favors biofilm formation and fights phage infection (van der Woude and Henderson, 2008); Hpf (log2 FC = 3; ribosome hibernation promoting factor), linked to increased persistence (Song and Wood, 2020); RpmH (log2 FC = 5; 50S ribosomal subunit protein L34), an inhibitor of biosynthetic ornithine and arginine decarboxylases (Panagiotidis and Canellakis, 1984), which are involved in the biosynthesis of polyamines; TufB (log2 FC = 5.8; translation elongation factor Tu 2), where EF-Tu binds aminoacyl tRNAs enabling protein synthesis (Weijland et al., 1992).

Our data indicate that quinolone sensitization as a result of suppression of the SOS response produces changes at the cellular level that involve genes other than those controlled by that stress response system (recombination and DNA repair processes), and it is observed despite the proteomic variability of response in clinical isolates. In other words, our study shows that a coordinated response is needed to enable the cell to combat quinolone-induced genotoxic damage. This involves the significant participation of multiple processes of the central metabolism of the bacteria, among which, in our study, the production and conversion of energy, amino acid, carbohydrate and nucleotide metabolism and transport processes stand out.

The data from our study validate previous studies that used Gram-positive and other Gram-negative bacteria as a model. Using P. aeruginosa after treatment with sub-MIC and MIC levels of ciprofloxacin demonstrated the involvement of the SOS response in the downregulation of genes encoding proteins involved in general metabolism and DNA replication/repair, as well as downregulation of genes involved in cell division, motility, quorum sensing, and cell permeability. These changes may contribute to pathogen survival during therapy (Cirz et al., 2006). With respect to S. aureus, overall, ciprofloxacin also appeared to induce the downregulation of its metabolism, but with a concomitant increase in TCA cycle activity and error-prone DNA replication. Induction of the TCA cycle appeared to be unique to S. aureus. Interestingly, increased utilization of the TCA cycle in this pathogen has been associated with virulence (Cirz et al., 2007). In our study, overexpressed proteins were mainly associated with persistence (Hpf) and biofilm formation (Ag43); however, other proteins were involved in protein synthesis (EF-Tu, TufB, RpmH) and protein refolding (IbpB).

In conclusion, the present study highlights the close relationship between the survival mechanisms of cellular stress response and bacterial metabolism (Lopatkin et al., 2021; York, 2021; Zampieri, 2021). This proteomic approach could contribute to the search for new therapeutic targets against resistant bacteria under genotoxic antimicrobial agents such as quinolones.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, PRJNA1015411.

Author contributions

ER: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BK: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SD-D: Writing – review & editing. AG-M: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. EG-T: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. FD-P: Writing – review & editing. AR-R: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JR-M: Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

For mass spectrometry, we would like to acknowledge the assistance of the Core Facility BioSupraMol (Freie Universität Berlin) supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). We also would like to acknowledge to Sociedad de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología clínica (SEIMC) for the grant awarded to ER for her stay at the Freie Universität Berlin, which has made possible the development of this work.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Plan Nacional de I+D+i 2013–2016 and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (project PI20/00239). ER was supported by a Juan Rodés fellowship from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (JR21/00030), co-funded by ESF “Investing in your future” and SEIMC mobility grant. SD-D was supported by a PFIS fellowship from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FI18/00086), co-funded by ESF “Investing in your future.”

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1379534/full#supplementary-material

References

- Baharoglu Z., Mazel D. (2014). SOS, the formidable strategy of bacteria against aggressions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 38, 1126–1145. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12077, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartual S. G., Seifert H., Hippler C., Luzon M. A. D., Wisplinghoff H., and Rodríguez-Valera F. (2005). Development of a multilocus sequence typing scheme for characterization of clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 4382–90. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4382-4390.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolaia V., Kaas R. S., Ruppe E., Roberts M. C., Schwarz S., Cattoir V., et al. (2020). ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75, 3491–3500. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa345, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briales A., Rodríguez-Martínez J. M., Velasco C., de Alba P. D., Rodríguez-Baño J., Martínez-Martínez L., et al. (2012). Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants qnr and aac(6′)-Ib-cr in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Spain. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 39, 431–434. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.12.009, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C., Coulouris G., Avagyan V., Ma N., Papadopoulos J., Bealer K., et al. (2009). BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirz R. T., Jones M. B., Gingles N. A., Minogue T. D., Jarrahi B., Peterson S. N., et al. (2007). Complete and SOS-mediated response of Staphylococcus aureus to the antibiotic ciprofloxacin. J. Bacteriol. 189, 531–539. doi: 10.1128/JB.01464-06, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirz R. T., O’Neill B. M., Hammond J. A., Head S. R., Romesberg F. E. (2006). Defining the Pseudomonas aeruginosa SOS response and its role in the global response to the antibiotic ciprofloxacin. J. Bacteriol. 188, 7101–7110. doi: 10.1128/JB.00807-06, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courcelle J., Khodursky A., Peter B., Brown P. O., Hanawalt P. C. (2001). Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient Escherichia coli. Genetics 158, 41–64. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.1.41, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culyba M. J., Kubiak J. M., Mo C. Y., Goulian M., Kohli R. M. (2018). Non-equilibrium repressor binding kinetics link DNA damage dose to transcriptional timing within the SOS gene network. PLoS Genet. 14:e1007405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007405, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. (2000). One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emms D. M., Kelly S. (2015). OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 16:157. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0721-2, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emms D. M., Kelly S. (2019). OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20:238. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1832-y, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández De Henestrosa A. R., Ogi T., Aoyagi S., Chafin D., Hayes J. J., Ohmori H., et al. (2000). Identification of additional genes belonging to the LexA regulon in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 35, 1560–1572. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01826.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths D., Fawley W., Kachrimanidou M., Bowden R., Crook D. W., Fung R., et al. (2010). Multilocus sequence typing of Clostridium difficile. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 770–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01796-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalvari I., Nawrocki E. P., Ontiveros-Palacios N., Argasinska J., Lamkiewicz K., Marz M., et al. (2021). Rfam 14: expanded coverage of metagenomic, viral and microRNA families. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D192–D200. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanjee U., Houry W. A. (2013). Mechanisms of acid resistance in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 67, 65–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp P. D., Ong W. K., Paley S., Billington R., Caspi R., Fulcher C., et al. (2018). The EcoCyc database. EcoSal Plus 8:2018. doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0006-2018, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzer K. N. (2005). Interplay between DNA replication and recombination in prokaryotes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59, 43–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121255, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen M. V., Cosentino S., Rasmussen S., Friis C., Hasman H., Marvig R. L., et al. (2012). Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J Clin Microbiol 50, 1355–61. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06094-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemee L., Dhalluin A., Pestel-Caron M., Lemeland J. -F., Pons J. -L. (2004). Multilocus sequence typing analysis of human and animal Clostridium difficile isolates of various toxigenic types. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 2609–17. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2609-2617.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomba M. R., Vasconcelos A. T., Pacheco A. B., de Almeida D. F. (1997). Identification of yebG as a DNA damage-inducible Escherichia coli gene. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 156, 119–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12715.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopatkin A. J., Bening S. C., Manson A. L., Stokes J. M., Kohanski M. A., Badran A. H., et al. (2021). Clinically relevant mutations in core metabolic genes confer antibiotic resistance. Science 371:862. doi: 10.1126/science.aba0862, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Cerero L., Bellido M. D. M., Serrano L., Liró J., Cisneros J. M., Rodríguez-Baño J., et al. (2013). Escherichia coli O25b:H4/ST131 are prevalent in Spain and are often not associated with ESBL or quinolone resistance. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 31, 385–388. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2012.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machuca J., Recacha E., Briales A., Díaz-de-Alba P., Blazquez J., Pascual Á., et al. (2017). Cellular response to ciprofloxacin in low-level quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 8:1370. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01370, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machuca J., Recacha E., Gallego-Mesa B., Diaz-Diaz S., Rojas-Granado G., García-Duque A., et al. (2021). Effect of RecA inactivation on quinolone susceptibility and the evolution of resistance in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 76, 338–344. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa448, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers A. J., Peirano G., Pitout J. D. D. (2015). The role of epidemic resistance plasmids and international high-risk clones in the spread of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 565–591. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00116-14, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotidis C. A., Canellakis E. S. (1984). Comparison of the basic Escherichia coli antizyme 1 and antizyme 2 with the ribosomal proteins S20/L26 and L34. J. Biol. Chem. 259, 15025–15027. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)42508-7, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Riverol Y., Bai J., Bandla C., García-Seisdedos D., Hewapathirana S., Kamatchinathan S., et al. (2022). The PRIDE database resources in 2022: a hub for mass spectrometry-based proteomics evidences. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D543–D552. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1038, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piróg A., Cantini F., Nierzwicki Ł., Obuchowski I., Tomiczek B., Czub J., et al. (2021). Two bacterial small heat shock proteins, IbpA and IbpB, form a functional heterodimer. J. Mol. Biol. 433:167054. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167054, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitout J. D. D., DeVinney R. (2017). Escherichia coli ST131: a multidrug-resistant clone primed for global domination. F1000Res 6:195. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.10609.1, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preumont A., Snoussi K., Stroobant V., Collet J.-F., Van Schaftingen E. (2008). Molecular identification of pseudouridine-metabolizing enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25238–25246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804122200, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappsilber J., Mann M., Ishihama Y. (2007). Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1896–1906. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.261, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recacha E., Machuca J., Díaz de Alba P., Ramos-Güelfo M., Docobo-Pérez F., Rodriguez-Beltrán J., et al. (2017). Quinolone resistance reversion by targeting the SOS response. MBio 8:17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00971-17, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recacha E., Machuca J., Díaz-Díaz S., García-Duque A., Ramos-Guelfo M., Docobo-Pérez F., et al. (2019). Suppression of the SOS response modifies spatiotemporal evolution, post-antibiotic effect, bacterial fitness and biofilm formation in quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 74, 66–73. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky407, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Martínez J.-M., López-Cerero L., Díaz-de-Alba P., Chamizo-López F. J., Polo-Padillo J., Pascual Á. (2016). Assessment of a phenotypic algorithm to detect plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71, 845–847. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv392, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T. (2014). Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 30, 2068–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S., Wood T. K. (2020). ppGpp ribosome dimerization model for bacterial persister formation and resuscitation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 523, 281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.01.102, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyanova S., Temu T., Cox J. (2016a). The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nat. Protoc. 11, 2301–2319. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.136, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyanova S., Temu T., Sinitcyn P., Carlson A., Hein M. Y., Geiger T., et al. (2016b). The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat. Methods 13, 731–740. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3901, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UniProt Consortium T. (2018). UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res, 46, 2699. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Woude M. W., Henderson I. R. (2008). Regulation and function of Ag43 (flu). Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 62, 153–169. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162938, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weijland A., Harmark K., Cool R. H., Anborgh P. H., Parmeggiani A. (1992). Elongation factor Tu: a molecular switch in protein biosynthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 6, 683–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01516.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodford N., Turton J. F., Livermore D. M. (2011). Multiresistant gram-negative bacteria: the role of high-risk clones in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35, 736–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00268.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka K., Zheng W., Crooke E., Wang Y. H., Inouye M. (2001). CspD, a novel DNA replication inhibitor induced during the stationary phase in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 39, 1572–1584. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02345.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda T., Morimatsu K., Horii T., Nagata T., Ohmori H. (1998). Inhibition of Escherichia coli RecA coprotease activities by DinI. EMBO J. 17, 3207–3216. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3207, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York A. (2021). A new general mechanism of AMR. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19:283. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00539-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampieri M. (2021). The genetic underground of antibiotic resistance. Science 371, 783–784. doi: 10.1126/science.abf7922, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zankari E., Allesøe R., Joensen K. G., Cavaco L. M., Lund O., Aarestrup F. M. (2017). PointFinder: a novel web tool for WGS-based detection of antimicrobial resistance associated with chromosomal point mutations in bacterial pathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72, 2764–2768. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx217, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zankari E., Hasman H., Cosentino S., Vestergaard M., Rasmussen S., Lund O., et al. (2012). Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, PRJNA1015411.