Abstract

This paper investigates fairness and bias in Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA), a widely used statistical technique for examining the relationship between two sets of variables. We present a framework that alleviates unfairness by minimizing the correlation disparity error associated with protected attributes. Our approach enables CCA to learn global projection matrices from all data points while ensuring that these matrices yield comparable correlation levels to group-specific projection matrices. Experimental evaluation on both synthetic and real-world datasets demonstrates the efficacy of our method in reducing correlation disparity error without compromising CCA accuracy.

1. Introduction

Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) is a multivariate statistical technique that explores the relationship between two sets of variables [30]. Given two datasets and on the same set of N observations,1 CCA seeks the R–dimensional subspaces where the projections of and are maximally correlated, i.e. finds and such that

| (CCA) |

CCA finds applications in various fields, including biology [51], neuroscience [2], medicine [79], and engineering [14], for unsupervised or semi-supervised learning. It improves tasks like clustering, classification, and manifold learning by creating meaningful dimensionality-reduced representations [70]. However, CCA can exhibit unfair behavior when analyzing data with protected attributes, like sex or race. For instance, in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) analysis, CCA can establish correlations between brain imaging and cognitive decline. Yet, if it does not consider the influence of sex, it may result in disparate correlations among different groups because AD affects males and females differently, particularly in cognitive decline [36, 81].

The influence of machine learning on individuals and society has sparked a growing interest in the topic of fairness [42]. While fairness techniques are well-studied in supervised learning [5, 18, 20], attention is shifting to equitable methods in unsupervised learning [11, 12, 15, 34, 49, 55, 64]. Despite extensive work on fairness in machine learning, fair CCA (F-CCA) remains unexplored. This paper investigates F-CCA and introduces new approaches to mitigate bias in (CCA).

For further discussion, we compare CCA with our proposed F-CCA in sample projection, as illustrated in Figure 1. In Figure 1(a), we have samples and from matrix , and in Figure 1(b), their corresponding samples and are from matrix . CCA learns and to maximize correlation, inversely related to the angle between the sample vectors. Figure 1(c) demonstrates the proximity within the projected sample pairs and . In Figure 1(d)–(i), we compare the results of different learning strategies. There are five pairs of samples, with female pairs highlighted in red and male pairs shown in blue. Random projection (Figure 1(e)) leads to randomly large angles between corresponding sample vectors. CCA reduces angles compared to random projection (Figure 1(f)), but significant angle differences between male and female pairs indicate bias. Using sex-based projection matrices heavily biases the final projection, favoring one sex over the other (Figures 1(g) and 1(h)). To address this bias, our F-CCA maximizes correlation within pairs and ensures equal correlations across different groups, such as males and females (Figure 1(i)). Note that while this illustration represents individual fairness, the desired outcome in practice is achieving similar average angles for different groups.

Figure 1:

Illustration of CCA and F-CCA, with the sensitive attribute being sex (female and male). Figures (a)–(c) demonstrate the general framework of CCA, while Figures (d)–(i) provide a comparison of the projected results using various strategies. It is important to note that the correlation between two corresponding samples is inversely associated with the angle formed by their projected vectors. F-CCA aims to equalize the angles among all pairs .

Contributions.

This paper makes the following key contributions:

We introduce fair CCA (F-CCA), a model that addresses fairness issues in (CCA) by considering multiple groups and minimizing the correlation disparity error of protected attributes. F-CCA aims to learn global projection matrices from all data points while ensuring that these projection matrices produce a similar amount of correlation as group-specific projection matrices.

We propose two optimization frameworks for F-CCA: multi-objective and single-objective. The multi-objective framework provides an automatic trade-off between global correlation and equality in group-specific correlation disparity errors. The single-objective framework offers a simple approach to approximate fairness in CCA while maintaining a strong global correlation, requiring a tuning parameter to balance these objectives.

We develop a gradient descent algorithm on a generalized Stiefel manifold to solve the multi-objective problem, with convergence guarantees to a Pareto stationary point. This approach extends Riemannian gradient descent [8, 9] to multi-objective optimization, accommodating a broader range of retraction maps than exponential retraction [23, 6]. Furthermore, we provide a similar algorithm for single-objective problems, also with convergence guarantees to a stationary point.

We provide extensive empirical results showcasing the efficacy of the proposed algorithms. Comparison against the CCA method on synthetic and real datasets highlights the benefits of the F-CCA approach, validating the theoretical findings2.

Organization:

Section 2 covers related work. Our proposed approach is detailed in Section 3, along with its theoretical guarantees. Section 4 showcases numerical experiments, while Section 5 discusses implications and future research directions.

2. Related work

Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA).

CCA was first introduced by [28, 29]. Since then, it has been utilized to explore relations between variables in various fields of science, including economics [72], psychology [19, 27], geography [45], medicine [39], physics [76], chemistry [69], biology [62], time-series modeling [26], and signal processing [57]. Recently, CCA has demonstrated its applicability in modern fields of science such as neuroscience, machine learning, and bioinformatics [59, 60]. CCA has been used to explore relations for developing brain-computer interfaces [10, 46] and in the field of imaging genetics [22]. CCA has also been applied for feature selection [47], feature extraction and fusion [61], and dimension reduction [71]. Additionally, numerous studies have applied CCA in bioinformatics and computational biology, such as [54, 56, 58]. The broad range of application domains highlights the versatility of CCA in extracting relations between variables, making it a valuable tool in scientific research.

Fairness.

Fairness in machine learning has been a growing area of research, with much of the work focusing on fair supervised methods [5, 16, 18, 20, 67, 78]. However, there has also been increasing attention on fair methods for unsupervised learning tasks [11, 12, 15, 34, 33, 49, 55, 64, 50, 66]. In particular, Samadi et al. [55] proposed a semi-definite programming approach to ensure fairness in PCA. Kleindessner et al. [33, 34] focused on fair PCA formulation for multiple groups and proposed a kernel-based fair PCA. Kamani et al. [32] introduced an efficient gradient method for fair PCA, addressing multi-objective optimization. In this paper, we propose a novel multi-objective framework for F-CCA, converting constrained F-CCA problems to unconstrained ones on a generalized Riemannian manifold. This framework enables the adaptation of efficient gradient techniques for numerical optimization on Riemannian manifolds.

Riemannian Optimization.

Riemannian optimization extends Euclidean optimization to smooth manifolds, enabling the minimization of on a Riemannian manifold and converting constrained problems into unconstrained ones [1, 8]. It finds applications in various domains such as matrix/tensor factorization [31, 63], PCA [21], and CCA [77]. Specifically, CCA can be formulated as Riemannian optimization on the Stiefel manifold [13, 43]. In our work, we utilize Riemannian optimization to develop a multi-objective framework for F-CCAs on generalized Stiefel manifolds.

3. Fair Canonical Correlation Analysis

This section introduces the formulation and optimization algorithms for F-CCA.

3.1. Preliminary

Real numbers are represented as , with for nonnegative values and for positives. Vectors and matrices use bold lowercase and uppercase letters (e.g., a, A) with elements and . For and mean and , respectively. For a symmetric matrix and denote positive definiteness and positive semidefiniteness (PSD), respectively. , and are D × D identity, all-ones, and all-zeros matrices. stands for the i-th singular values of . Matrix norms are defined as , and . We introduce some preliminaries on manifold optimization [1, 6, 8]. Given a PSD matrix , the generalized Stiefel manifold is defined as

| (1) |

The tangent space of the manifold at is given by

| (2) |

The tangent bundle of a smooth manifold , which consists of at all , is defined as

| (3) |

Definition 1. A retraction on a differentiable manifold is a smooth mapping from its tangent bundle to that satisfies the following conditions, with being the retraction of to :

, for all , where denotes the zero element of .

For any , it holds that .

In the numerical experiments, this work employs a generalized polar decomposition-based retraction. Given a PSD matrix , for any with , it is defined as:

| (4) |

where is the singular value decomposition of , and are obtained from the eigen-value decomposition . Further details on retraction choices are in Appendix A.1.

3.2. Correlation Disparity Error

As previously mentioned, applying CCA to the entire dataset could lead to a biased result, as some groups might dominate the analysis while others are overlooked. To avoid this, we can perform CCA separately on each group and compare the results. Indeed, we can compare the performance of CCA on each group’s data with the performance of CCA on the whole dataset, which includes all groups’ data. The goal is to find a balance between the benefits and sacrifices of different groups so that each group’s contribution to the CCA analysis is treated fairly. In particular, suppose the datasets and on the same set of N observations, belong to K different groups with and , based on demographics or some other semantically meaningful clustering. These groups need not be mutually exclusive; each group can be defined as a different weighting of the data.

To determine how each group is affected by F-CCA, we can compare the structure learned from each group’s data with the structure learned from all groups’ data combined . A fair CCA approach seeks to balance the benefits and drawbacks of each group’s contribution to the analysis. Specifically, if we train global subspaces and on k-th group dataset , we can identify the group-specific (local) weights represented by that has the best performance on that dataset. Thus, F-CCA algorithm should be able to learn global weights on all data points while ensuring that each group’s correlation on the CCA learned by the whole dataset is equivalent to the group-specific subspaces learned only by its own data.

To define these fairness criteria, we introduce correlation disparity error as follows:

Definition 2 (Correlation Disparity Error). Consider a pair of datasets with sensitive groups with data matrix representing each sensitive group’s data samples. Then, for any , the correlation disparity error for each sensitive group is defined as:

| (5) |

Here, is the maximizer of the following group-specific CCA problem:

| (6) |

This measure shows how much correlation we are suffering for any global , with respect to the loss of optimal local that we can learn based on data points . Using Definition 2, we can define F-CCA as follows:

Definition 3 (Fair CCA). A CCA pair is called fair if the correlation disparity error among different groups is equal, i.e.,

| (7) |

A CCA pair that achieves the same disparity error for all groups is called a fair CCA.

Next, we introduce the concept of pairwise correlation disparity error for CCA, which measures the variation in correlation disparity among different groups.

Definition 4 (Pairwise Correlation Disparity Error). The pairwise correlation disparity error for any global and group-specific subspaces , is defined as

| (8) |

Here, is a penalty function such as , or .

The motivation for incorporating disparity error regularization in our approach can be attributed to the work by [40, 55] in the context of PCA. To facilitate convergence analysis, we will primarily consider smooth penalization functions, such as squared or exponential penalties.

3.3. A Multi-Objective Framework for Fair CCA

In this section, we introduce an optimization framework for balancing correlation and disparity errors. Let . The optimization problem of finding an optimal Pareto point of is denoted by

| (9) |

where and .

A point satisfying is called critical Pareto. Here, Im denotes the image of Jacobian of . An optimum Pareto point of is a point such that there exists no other with . Moreover, a point is a weak optimal Pareto of if there is no with . The multi-objective framework (9) addresses the challenge of handling conflicting objectives and achieving optimal trade-offs between them.

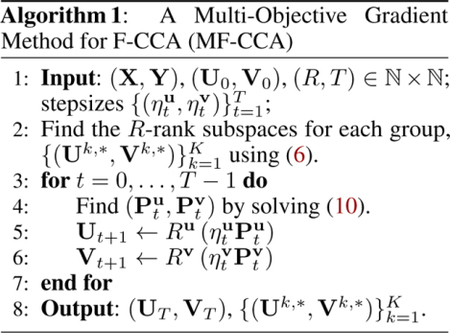

To effectively solve Problem (9), we propose utilizing a gradient descent method on the Riemannian manifold that ensures convergence to a Pareto stationary point. The proposed gradient descent algorithm for solving (9) is provided in Algorithm 1. For each , let with and . The iterates in Step 4 are obtained by solving the following subproblem in the joint tangent plane :

| (10) |

If is not a Pareto stationary point, Problem (10) has a unique nonzero solution (see Lemma 7), known as the steepest descent direction for at . In Steps 5 and 6, and denote the retractions onto the tangent spaces and , respectively; refer to Definition 1.

Assumption A. For a given subset of the tangent bundle , there exists a constant such that, for all , we have , where , and is the retraction.

The above assumption extends [8, A 4.3] to multi-objective optimization, and it always holds for the exponential map (exponential retraction) if the gradient of is -Lipschitz continuous [23, 6].

Theorem 5. Suppose Assumption A holds. Let be the sequence generated by MF-CCA. Let , for all and define . If for all , then

Proof Sketch. We employ Lemma 7 to establish the unique solution for subproblem (10). Lemmas 9 and 10 provide estimates for the decrease of function along : For any , we have . Summing this inequality over and applying our step size condition yields the desired result. □

Theorem 5 provides a generalization of [8, Corollary 4.9] to the multi-objective optimization, showing that the norm of Pareto descent directions converges to zero. Consequently, the solutions produced by the algorithm converge to a stationary fair subspace. It is worth mentioning that multi-objective optimization in [23, 6] relies on the Riemannian exponential map, whereas the above theorem covers broader (and practical) retraction maps.

3.4. A Single-Objective Framework for Fair CCA

In this section, we introduce a straightforward and effective single-objective framework. This approach simplifies F-CCA optimization, lowers computational requirements, and allows for fine-tuning fairness-accuracy trade-offs using the hyperparameter . Specifically, by employing a regularization parameter , our proposed fairness model for F-CCA is expressed as follows:

| (11) |

where ; see Definiton 4.

The choice of in the model determines the emphasis placed on different objectives. When is large, the model prioritizes fairness over minimizing subgroup errors. Conversely, if is small, the focus shifts towards minimizing subgroup correlation errors rather than achieving perfect fairness. In other words, it is possible to obtain perfectly F-CCA subspaces; however, this may come at the expense of larger errors within the subgroups. The constant in the model allows for a flexible trade-off between fairness and minimizing subgroup correlation errors, enabling us to find a balance based on the specific requirements and priorities of the problem at hand.

The proposed gradient descent algorithm for solving (11) is provided as Algorithm 2. For each , let with and . The iterates are obtained by solving the following problem in the joint tangent plane :

| (12) |

The solutions are maintained on the manifolds using the retraction operations and .

Assumption B. For a subset , there exists a constant such that for all , with as the retraction.

Theorem 6. Suppose Assumption B holds. Let be the sequence generated by SF-CCA. Let . If for all , then

Comparison between MF-CCA and SF-CCA:

MF-CCA addresses conflicting objectives and achieves optimal trade-offs automatically, but it necessitates the inclusion of additional objectives. SF-CCA, on the other hand, provides a simpler approach but requires tuning an extra hyperparameter . When choosing between the two methods, it is crucial to consider the trade-off between complexity and simplicity, as well as the number of objectives and the need for hyperparameter tuning.

4. Experiments

In this section, we provide empirical results showcasing the efficacy of the proposed algorithms.

4.1. Evaluation Criteria and Selection of Tuning Parameter

F-CCA’s performance is evaluated on correlation and fairness for each dimension of subspaces. Let and . The r-th canonical correlation is defined as follows:

| (13a) |

Next, in terms of fairness, we establish the following two key measures:

| (13b) |

| (13c) |

Here, measures maximum disparity error, while represents aggregate disparity error. The aim is to reach and of 0 without sacrificing correlation compared to CCA. We conduct a detailed analysis using component-wise measurements (13) instead of matrix versions; for more discussions, see Appendix C.2.

The canoncorr function from MATLAB and [35] is used to solve (CCA). For MF-CCA and SF-CCA, the learning rate is searched on a grid in , and for SF-CCA, is searched on a grid in . Sensitivity analysis of is provided in Appendix B.2. The learning rate decreases with the square root of the iteration number. Termination of algorithms occurs when the descent direction norm is below .

4.2. Dataset

4.2.1. Synthetic Data

Following [4, 44], our synthetic data are generated using the Gaussian distribution

Here, and are the means of data matrices and , respectively; covariance matrices and the cross-covariance matrix are constructed as follows. Given ground truth projection matrices and canonical correlations defined in (13a). Let and be the QR decomposition of and , then we have

| (14a) |

| (14b) |

| (14c) |

Here, and are randomly generated by normal distributions, and and are scaling hyperparameters. For subgroup distinction, we added noise to canonical vectors and adjusted sample sizes: 300, 350, 400, 450, and 500 observations each. In the numerical experiment, different canonical correlations are assigned to each subgroup alongside two global canonical vectors and to generate five distinct subgroups.

4.2.2. Real Data

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

We utilized the 2005–2006 subset of the NHANES database https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes, including physical measurements and self-reported questionnaires from participants. We partitioned the data into two distinct subsets: one with 96 phenotypic measures and the other with 55 environmental measures. Our objective was to apply F-CCA to explore the interplay between phenotypic and environmental factors in contributing to health outcomes, considering the impact of education. Thus, we segmented the dataset into three subgroups based on educational attainment (i.e., lower than high school, high school, higher than high school), with 2,495, 2,203, and 4,145 observations in each subgroup.

Mental Health and Academic Performance Survey (MHAAPS).

This dataset is available at https://github.com/marks/convert_to_csv/tree/master/sample_data. It consists of three psychological variables, four academic variables, as well as sex information for a cohort of 600 college freshmen (327 females and 273 males). The primary objective of this investigation revolves around examining the interrelationship between the psychological variables and academic indicators, with careful consideration given to the potential influence exerted by sex.

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI).

We utilized AV45 (amyloid) and AV1451 (tau) positron emission tomography (PET) data from the ADNI database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu) [73, 74]. ADNI data are analyzed for fairness in medical imaging classification [41, 53, 81], and sex disparities in ADNI’s CCA study can harm generalizability, validity, and intervention tailoring. We utilized F-CCA to account for sex differences. Our experiment links 52 AV45 and 52 AV1451 features in 496 subjects (255 females, 241 males).

4.3. Results and Discussion

In the simulation experiment, we follow the methodology described in Section 4.2.1 to generate two sets of variables, each containing two subgroups of equal size. Canonical weights are trained and used to project the two sets of variables into a 2-dimensional space using CCA, SF-CCA, and MF-CCA. From Figure 2, it is clear that the angle between the distributions of the two subgroups, as projected by SF-CCA and MF-CCA, is smaller in comparison. This result indicates that F-CCA has the ability to reduce the disparity between distinct subgroups.

Figure 2:

Scatter plot of the synthetic data points after projected to the 2-dimensional space. The distributions of the two groups after projection by CCA are orthogonal to each other. Our SF-CCA and MF-CCA can make the distributions of the two groups close to each other.

Table 1 shows the quantitative performance of the three models: CCA, MF-CCA, and SF-CCA. They are evaluated based on , and defined in (13) across five experimental sets. Table 2 displays the mean runtime of each model. Several key observations emerge from the analysis. Firstly, MF-CCA and SF-CCA demonstrate substantial improvements in fairness compared to CCA. However, it is important to note that F-CCA, employed in both MF-CCA and SF-CCA, compromises some degree of correlation due to its focus on fairness considerations during computations. Secondly, SF-CCA outperforms MF-CCA in terms of fairness improvement, although it sacrifices correlation. This highlights the effectiveness of the single-objective optimization approach in SF-CCA. Moreover, the datasets consist of varying subgroup quantities (5, 3, 2, and 2) and an imbalanced number of samples in distinct subgroups. F-CCA consistently performs well across these datasets, confirming its inherent scalability. Lastly, although SF-CCA requires more effort to tune hyperparameters, SF-CCA still exhibits a notable advantage in terms of time complexity compared to MF-CCA, demonstrating computational efficiency. Disparities among various CCA methods are visually represented in Figure 3. Notably, the conventional CCA consistently demonstrates the highest disparity error. Conversely, SF-CCA and MF-CCA consistently outperform CCA across all datasets, underscoring their efficacy in promoting fairness within analytical frameworks.

Table 1:

Numerical results in terms of Correlation , Maximum Disparity , and Aggregate Disparity metrics.

| Dataset | Dim. (r) | ρr ↑ | Δmax, r ↓ | Δsum, r ↓ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCA | MF-CCA | SF-CCA | CCA | MF-CCA | SF-CCA | CCA | MF-CCA | SF-CCA | ||

| Synthetic Data | 2 | 0.7533 | 0.7475 | 0.7309 | 0.3555 | 0.2866 | 0.2241 | 3.3802 | 2.8119 | 2.2722 |

| 5 | 0.4717 | 0.4681 | 0.4581 | 0.4385 | 0.3313 | 0.2424 | 4.1649 | 3.1628 | 2.2304 | |

| NHANES | 2 | 0.6392 | 0.6360 | 0.6334 | 0.0485 | 0.0359 | 0.0245 | 0.1941 | 0.1435 | 0.0980 |

| 5 | 0.4416 | 0.4393 | 0.4392 | 0.1001 | 0.0818 | 0.0824 | 0.4003 | 0.3272 | 0.3297 | |

| MHAAPS | 1 | 0.4464 | 0.4451 | 0.4455 | 0.0093 | 0.0076 | 0.0044 | 0.0187 | 0.0152 | 0.0088 |

| 2 | 0.1534 | 0.1529 | 0.1526 | 0.0061 | 0.0038 | 0.0019 | 0.0122 | 0.0075 | 0.0039 | |

| ADNI | 2 | 0.7778 | 0.7776 | 0.7753 | 0.0131 | 0.0119 | 0.0064 | 0.0263 | 0.0238 | 0.0127 |

| 5 | 0.6810 | 0.6798 | 0.6770 | 0.0477 | 0.0399 | 0.0324 | 0.0954 | 0.0799 | 0.0648 | |

Best values are in bold, and second-best are underlined. We focus on the initial five projection dimensions, but present only two dimensions here; results for other dimensions are in the supplementary material. We put the results of other projection dimensions in the supplementary material. “↑” means the larger the better and “↓” means the smaller the better. Note that MHAAPS has only 3 features, so we report results for its 1 and 2 dimensions.

Table 2:

Mean computation time in seconds (±std) of 10 repeated experiments for on the real dataset and on the synthetic dataset. Experiments are run on Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5–2660.

| Dataset | CCA | MF-CCA | SF-CCA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Data | 0.0239±0.0026 | 109.0693±5.5418 | 29.1387±2.0828 |

| NHANES | 0.0483±0.0059 | 42.3186±1.9045 | 14.9156±1.8941 |

| MHAAPS | 0.0021±0.0047 | 3.5235±2.0945 | 0.8238±0.8155 |

| ADNI | 0.0039±0.0032 | 2.7297±0.5136 | 1.8489±1.0519 |

Figure 3:

Aggregate disparity of CCA, MF-CCA, and SF-CCA (results from Table 1).

In Table 1, we define the percentage change of correlation , maximum disparity gap , and aggregate disparity , respectively, as follows: of CCA)/ of CCA) × 100, of F-CCA – of CCA)/ of CCA) × 100, and of F-CCA – of CCA)/ of CCA) × 100. Here, F-CCA is replaced with either MF-CCA or SF-CCA to obtain the percentage change for MF-CCA or SF-CCA. Figure 4 illustrates the percentage changes of each dataset. is slight, while and changes are substantial, signifying fairness improvement without significant accuracy sacrifice.

Figure 4:

Percentage change from CCA to F-CCA (results from Table 1). Each dataset panel shows two cases with projection dimensions . is slight, while and changes are substantial, signifying fairness improvement without significant accuracy sacrifice.

5. Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

We propose F-CCA, a novel framework to mitigate unfairness in CCA. F-CCA aims to rectify the bias of CCA by learning global projection matrices from the entire dataset, concurrently guaranteeing that these matrices generate correlation levels akin to group-specific projection matrices. Experiments show that F-CCA is effective in reducing correlation disparity error without sacrificing much correlation. We discuss potential extensions and future problems stemming from our work.

While F-CCA effectively reduces unfairness while maintaining CCA model accuracy, its potential to achieve a minimum achievable disparity correlation remains unexplored. A theoretical exploration of this aspect could provide valuable insights.

F-CCA holds promise for extensions to diverse domains, including multiple modalities [80], deep CCA [3], tensor CCA [44], and sparse CCA [25]. However, these extensions necessitate novel formulations and in-depth analysis.

Our approach of multi-objective optimization on smooth manifolds may find relevance in other problems, such as fair PCA [55]. Further, bilevel optimization approaches [37, 68, 65] can be designed on a smooth manifold to learn a single Pareto-efficient solution and provide an automatic trade-off between accuracy and fairness.

With applications encompassing clustering, classification, and manifold learning, F-CCA ensures fairness when employing CCA techniques for these downstream tasks. It can also be jointly analyzed with fair clustering [15, 66,34] and fair classification [78, 18].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the NIH grants U01 AG066833, U01 AG068057, RF1 AG063481, R01 LM013463, P30 AG073105, and U01 CA274576, and the NSF grant IIS 1837964. The ADNI data were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative database (https://adni.loni.usc.edu), funded by NIH U01 AG024904. Moreover, the NHANES data were sourced from the NHANES database (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes).

We appreciate the reviewers’ valuable feedback, which significantly improved this paper.

Footnotes

The columns of and have been standardized.

Code is available at https://github.com/PennShenLab/Fair_CCA.

References

- [1].Absil P-A. Optimization algorithms on matrix manifolds. Princeton University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Al-Shargie Fares, Tang Tong Boon, and Kiguchi Masashi. Assessment of mental stress effects on prefrontal cortical activities using canonical correlation analysis: an fnirs-eeg study. Biomedical optics express, 8(5):2583–2598, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Andrew Galen, Arora Raman, Bilmes Jeff, and Livescu Karen. Deep canonical correlation analysis. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 1247–1255, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bach Francis R. and Jordan Michael I.. A probabilistic interpretation of canonical correlation analysis. 2005.

- [5].Barocas Solon, Hardt Moritz, and Narayanan Arvind. Fairness and machine learning: Limitations and opportunities. MIT Press, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bento GC, Ferreira Orizon Pereira, and Oliveira P Roberto. Unconstrained steepest descent method for multicriteria optimization on riemannian manifolds. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications, 154:88–107, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bento Glaydston C, Ferreira Orizon P, and Melo Jefferson G. Iteration-complexity of gradient, subgradient and proximal point methods on riemannian manifolds. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications, 173(2):548–562, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Boumal Nicolas. An introduction to optimization on smooth manifolds. Cambridge University Press, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Boumal Nicolas, Absil Pierre-Antoine, and Cartis Coralia. Global rates of convergence for nonconvex optimization on manifolds. IMA Journal of Numerical Analysis, 39(1):1–33, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cao L, Ju Z, Li J, Jian R, and Jiang C. Sequence detection analysis based on canonical correlation for steady-state visual evoked potential brain computer interfaces. Journal of neuroscience methods, 253:10–17, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Caton Simon and Haas Christian. Fairness in machine learning: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.04053, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Celis L Elisa, Straszak Damian, and Vishnoi Nisheeth K. Ranking with fairness constraints. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.06840, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chen Shixiang, Ma Shiqian, Xue Lingzhou, and Zou Hui. An alternating manifold proximal gradient method for sparse principal component analysis and sparse canonical correlation analysis. INFORMS Journal on Optimization, 2(3):192–208, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chen Zhiwen, Ding Steven X, Peng Tao, Yang Chunhua, and Gui Weihua. Fault detection for non-gaussian processes using generalized canonical correlation analysis and randomized algorithms. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 65(2):1559–1567, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chierichetti Flavio, Kumar Ravi, Lattanzi Silvio, and Vassilvitskii Sergei. Fair clustering through fairlets. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chouldechova Alexandra and Roth Aaron. The frontiers of fairness in machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.08810, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dang Vien Ngoc, Cascarano Anna, Mulder Rosa H., Cecil Charlotte, Zuluaga Maria A., Hernández-González Jerónimo, and Lekadir Karim. Fairness and bias correction in machine learning for depression prediction: results from four different study populations, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [18].Donini Michele, Oneto Luca, Ben-David Shai, Shawe-Taylor John, and Pontil Massimiliano. Empirical risk minimization under fairness constraints. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.08626, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dunham Ralph B and Kravetz David J. Canonical correlation analysis in a predictive system. The Journal of Experimental Education, 43(4):35–42, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dwork Cynthia, Hardt Moritz, Pitassi Toniann, Reingold Omer, and Zemel Richard. Fairness through awareness. In Proceedings of the 3rd innovations in theoretical computer science conference, pages 214–226, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Edelman Alan, Arias Tomás A, and Smith Steven T. The geometry of algorithms with orthogonality constraints. SIAM journal on Matrix Analysis and Applications, 20(2):303–353, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fang J, Lin D, Schulz SC, Xu Z, Calhoun VD, and Wang Y-P. Joint sparse canonical correlation analysis for detecting differential imaging genetics modules. Bioinformatics, 32(22):3480–3488, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ferreira Orizon P, Louzeiro Mauricio S, and Prudente Leandro F. Iteration-complexity and asymptotic analysis of steepest descent method for multiobjective optimization on riemannian manifolds. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications, 184:507–533, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gembicki F and Haimes Y. Approach to performance and sensitivity multiobjective optimization: The goal attainment method. IEEE Transactions on Automatic control, 20(6):769–771, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hardoon David R and Shawe-Taylor John. Sparse canonical correlation analysis. Machine Learning, 83(3):331–353, June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Heij C and Roorda B. A modified canonical correlation approach to approximate state space modelling. In Decision and Control, 1991., Proceedings of the 30th IEEE Conference on, pages 1343–1348. IEEE, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hopkins CE. Statistical analysis by canonical correlation: a computer application. Health services research, 4(4):304, 1969. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hotelling H. Relations between two sets of variates. Biometrika, 28(3/4):321–377, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hotelling Harold. The most predictable criterion. Journal of educational Psychology, 26(2):139, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hotelling Harold. Relations between two sets of variates. Breakthroughs in statistics: methodology and distribution, pages 162–190, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ishteva Mariya, Absil P-A, Van Huffel Sabine, and De Lathauwer Lieven. Best low multilinear rank approximation of higher-order tensors, based on the riemannian trust-region scheme. SIAM Journal on Matrix Analysis and Applications, 32(1):115–135, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kamani Mohammad Mahdi, Haddadpour Farzin, Forsati Rana, and Mahdavi Mehrdad. Efficient fair principal component analysis. Machine Learning, pages 1–32, 2022.35668720 [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kleindessner Matthäus, Donini Michele, Russell Chris, and Zafar Muhammad Bilal. Efficient fair pca for fair representation learning. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, pages 5250–5270. PMLR, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kleindessner Matthäus, Samadi Samira, Awasthi Pranjal, and Morgenstern Jamie. Guarantees for spectral clustering with fairness constraints. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 3458–3467. PMLR, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Krzanowski Wojtek J. Principles of multivariate analysis. Oxford University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Laws Keith R, Irvine Karen, and Gale Tim M. Sex differences in cognitive impairment in alzheimer’s disease. World J Psychiatry, 6(1):54–65, March 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Li Mingchen, Zhang Xuechen, Thrampoulidis Christos, Chen Jiasi, and Oymak Samet. Autobalance: Optimized loss functions for imbalanced data. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34:3163–3177, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lin Tianyi, Fan Chenyou, Ho Nhat, Cuturi Marco, and Jordan Michael. Projection robust wasserstein distance and riemannian optimization. Advances in neural information processing systems, 33:9383–9397, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lindsey H, Webster JT, and Halpern S. Canonical correlation as a discriminant tool in a periodontal problem. Biometrical journal, 27(3):257–264, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kamani Mohammad Mahdi, Haddadpour Farzin, Forsati Rana, and Mahdavi Mehrdad. Efficient fair principal component analysis. arXiv e-prints, pages arXiv-1911, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Mazure Carolyn M and Swendsen Joel. Sex differences in alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. The Lancet Neurology, 15(5):451–452, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mehrabi Ninareh, Morstatter Fred, Saxena Nripsuta, Lerman Kristina, and Galstyan Aram. A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 54(6):1–35, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Meng Zihang, Chakraborty Rudrasis, and Singh Vikas. An online riemannian pca for stochastic canonical correlation analysis. Advances in neural information processing systems, 34:14056–14068, 2021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Min Eun Jeong, Chi Eric C, and Zhou Hua. Tensor canonical correlation analysis. Stat, 8(1):e253, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Monmonier Mark S and Finn Fay Evanko. Improving the interpretation of geographical canonical correlation models. The Professional Geographer, 25(2):140–142, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Nakanishi Masaki, Wang Yijun, Wang Yu-Te, and Jung Tzyy-Ping. A comparison study of canonical correlation analysis based methods for detecting steady-state visual evoked potentials. PloS one, 10(10):e0140703, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ogura Toru, Fujikoshi Yasunori, and Sugiyama Takakazu. A variable selection criterion for two sets of principal component scores in principal canonical correlation analysis. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods, 42(12):2118–2135, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Omogbai Aileme. Application of multiview techniques to NHANES dataset. CoRR, abs/1608.04783, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Oneto Luca and Chiappa Silvia. Fairness in machine learning. In Recent Trends in Learning From Data, pages 155–196. Springer, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Peltonen Jaakko, Xu Wen, Nummenmaa Timo, and Nummenmaa Jyrki. Fair neighbor embedding. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Pimentel Harold, Hu Zhiyue, and Huang Haiyan. Biclustering by sparse canonical correlation analysis. Quantitative Biology, 6(1):56–67, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Qi Miao, Cahan Owen, Foreman Morgan A, Gruen Daniel M, Das Amar K, and Bennett Kristin P. Quantifying representativeness in randomized clinical trials using machine learning fairness metrics. JAMIA Open, 4(3):ooab077, 092021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Reeves Mathew J, Bushnell Cheryl D, Howard George, Gargano Julia Warner, Duncan Pamela W, Lynch Gwen, Khatiwoda Arya, and Lisabeth Lynda. Sex differences in stroke: epidemiology, clinical presentation, medical care, and outcomes. The Lancet Neurology, 7(10):915–926, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Rousu Juho, Agranoff David D, Sodeinde Olugbemiro, Shawe-Taylor John, and Fernandez-Reyes Delmiro. Biomarker discovery by sparse canonical correlation analysis of complex clinical phenotypes of tuberculosis and malaria. PLoS Comput Biol, 9(4):e1003018, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Samadi Samira, Tantipongpipat Uthaipon, Morgenstern Jamie H, Singh Mohit and Vempala Santosh. The price of fair pca: One extra dimension. Advances in neural information processing systems, 31, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sarkar Biplab K and Chakraborty Chiranjib. Dna pattern recognition using canonical correlation algorithm. Journal of biosciences, 40(4):709–719, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Schell Steven V and Gardner William A. Programmable canonical correlation analysis: A flexible framework for blind adaptive spatial filtering. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, 43(12):2898–2908, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Seoane Jose A, Campbell Colin, Day Ian NM, Casas Juan P, and Gaunt Tom R. Canonical correlation analysis for gene-based pleiotropy discovery. PLoS Comput Biol, 10(10):e1003876, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Sha J, Bao J, Liu K, Yang S, Wen Z, Wen J, Cui Y, Tong B, Moore JH, Saykin AJ, Davatzikos C, Long Q, Shen L, and Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Preference matrix guided sparse canonical correlation analysis for mining brain imaging genetic associations in alzheimer’s disease. Methods, 218:27–38, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Shen Li and Thompson Paul M.. Brain imaging genomics: Integrated analysis and machine learning. Proceedings of the IEEE, 108(1):125–162, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Shen Xiao-Bo, Sun Qi-Song, and Yuan Yuan-Hai. Orthogonal canonical correlation analysis and its application in feature fusion. In Information Fusion (FUSION), 2013 16th International Conference on, pages 151–157. IEEE, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Sullivan Michael J. Distribution of edaphic diatoms in a missisippi salt marsh: A canonical correlation analysis. Journal of Phycology, 18(1):130–133, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- [63].Tan Mingkui, Tsang Ivor W, Wang Li, Vandereycken Bart, and Pan Sinno Jialin. Riemannian pursuit for big matrix recovery. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 1539–1547. PMLR, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [64].Tantipongpipat Uthaipon, Samadi Samira, Singh Mohit, Morgenstern Jamie H, and Vempala Santosh S. Multi-criteria dimensionality reduction with applications to fairness. Advances in neural information processing systems, (32), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Tarzanagh Davoud Ataee and Balzano Laura. Online bilevel optimization: Regret analysis of online alternating gradient methods. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.02829, 2022. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Tarzanagh Davoud Ataee, Balzano Laura, and Hero Alfred O. Fair structure learning in heterogeneous graphical models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.05128, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [67].Tarzanagh Davoud Ataee, Hou Bojian, Tong Boning, Long Qi, and Shen Li. Fairness-aware class imbalanced learning on multiple subgroups. In Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence, pages 2123–2133. PMLR, 2023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Tarzanagh Davoud Ataee, Li Mingchen, Thrampoulidis Christos, and Oymak Samet. Fednest: Federated bilevel, minimax, and compositional optimization. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 21146–21179. PMLR, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [69].Tu Xin M, Burdick Donald S, Millican Debra W, and McGown L Bruce. Canonical correlation technique for rank estimation of excitation-emission matrixes. Analytical chemistry, 61(19):2219–2224, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Uurtio Viivi, Monteiro João M, Kandola Jaz, Shawe-Taylor John, Fernandez-Reyes Delmiro, and Rousu Juho. A tutorial on canonical correlation methods. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 50(6):1–33, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [71].Wang GC, Lin N, and Zhang B. Dimension reduction in functional regression using mixed data canonical correlation analysis. Stat Interface, 6:187–196, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [72].Waugh FV. Regressions between sets of variables. Econometrica, Journal of the Econometric Society, pages 290–310, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- [73].Weiner MW, Veitch DP, Aisen PS, et al. The alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative: a review of papers published since its inception. Alzheimers Dement, 9(5):e111–94, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Weiner Michael W, Veitch Dallas P, Aisen Paul S, et al. Recent publications from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: Reviewing progress toward improved AD clinical trials. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 13(4):e1–e85, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Wen Zaiwen and Yin Wotao. A feasible method for optimization with orthogonality constraints. Mathematical Programming, 142(1–2):397–434, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [76].Wong KW, Fung PCW, and Lau CC. Study of the mathematical approximations made in the basis-correlation method and those made in the canonical-transformation method for an interacting bose gas. Physical Review A, 22(3):1272, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- [77].Yger Florian, Berar Maxime, Gasso Gilles, and Rakotomamonjy Alain. Adaptive canonical correlation analysis based on matrix manifolds. arXiv preprint arXiv:1206. 6453, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [78].Zafar Muhammad Bilal, Valera Isabel, Rogriguez Manuel Gomez, and Gummadi Krishna P. Fairness constraints: Mechanisms for fair classification. In Artificial intelligence and statistics, pages 962–970. PMLR, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [79].Zhang Yu, Zhou Guoxu, Jin Jing, Zhang Yangsong, Wang Xingyu, and Cichocki Andrzej. Sparse bayesian multiway canonical correlation analysis for eeg pattern recognition. Neurocomputing, 225:103–110, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [80].Zhuang Xiaowei, Yang Zhengshi, and Cordes Dietmar. A technical review of canonical correlation analysis for neuroscience applications. Human Brain Mapping, 41(13):3807–3833, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Zong Yongshuo, Yang Yongxin, and Hospedales Timothy. Medfair: Benchmarking fairness for medical imaging. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.01725, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.