Summary

Objective

To investigate the potential association between prenatal opioid exposure and the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in children.

Design

Nationwide birth cohort study.

Setting

From 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2020, birth cohort data of pregnant women in South Korea linked to their liveborn infants from the National Health Insurance Service of South Korea were collected.

Participants

All 3 251 594 infants (paired mothers, n=2 369 322; age 32.1 years (standard deviation 4.2)) in South Korea from the start of 2010 to the end of 2017, with follow-up from the date of birth until the date of death or 31 December 2020, were included.

Main outcome measures

Diagnosis of neuropsychiatric disorders in liveborn infants with mental and behaviour disorders (International Classification of Diseases 10th edition codes F00-99). Follow-up continued until the first diagnosis of neuropsychiatric disorder, 31 December 2020 (end of the study period), or the date of death, whichever occurred first. Eight cohorts were created: three cohorts (full unmatched, propensity score matched, and child screening cohorts) were formed, all of which were paired with sibling comparison cohorts, in addition to two more propensity score groups. Multiple subgroup analyses were performed.

Results

Of the 3 128 571 infants included (from 2 299 664 mothers), we identified 2 912 559 (51.3% male, 48.7% female) infants with no prenatal opioid exposure and 216 012 (51.2% male, 48.8% female) infants with prenatal opioid exposure. The risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in the child with prenatal opioid exposure was 1.07 (95% confidence interval 1.05 to 1.10) for fully adjusted hazard ratio in the matched cohort, but no significant association was noted in the sibling comparison cohort (hazard ratio 1.00 (0.93 to 1.07)). Prenatal opioid exposure during the first trimester (1.11 (1.07 to 1.15)), higher opioid doses (1.15 (1.09 to 1.21)), and long term opioid use of 60 days or more (1.95 (1.24 to 3.06)) were associated with an increased risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in the child. Prenatal opioid exposure modestly increased the risk of severe neuropsychiatric disorders (1.30 (1.15 to 1.46)), mood disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and intellectual disability in the child.

Conclusions

Opioid use during pregnancy was not associated with a substantial increase in the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in the offspring. A slightly increased risk of neuropsychiatric disorders was observed, but this should not be considered clinically meaningful given the observational nature of the study, and limited to high opioid dose, more than one opioid used, longer duration of exposure, opioid exposure during early pregnancy, and only to some neuropsychiatric disorders.

Introduction

The global opioid crisis has generated widespread attention because of its extensive effect on public health. While many women are generally cautious about medication intake during pregnancy,1 the need for pain management in some instances has led to an observable reliance on analgesics, including opioids.2 3 Besides analgesic treatment, pregnant women mainly used opioid as an antitussive treatment for coughs during pregnancy.4 The prevalence of opioid use during pregnancy in cohort studies of Medicaid beneficiaries in the United States and pregnancy cohort studies in Quebec is approximately 5%.5 6 Pregnant women often encounter specific physiological changes, such as increased ligamentous laxity, abnormal pain, and weight gain.7 These changes can induce or exacerbate various painful conditions, often necessitating the guidance of opioids as analgesics.8

While considerable attention has been directed towards the direct effect of opioid use on individuals using the drug, an increasing concern arises regarding the indirect effects on their offspring. Prenatal and early life exposure to various substances has been associated with long term neuropsychiatric and developmental outcomes in the child. For instance, prenatal exposure to alcohol, tobacco, and some medications has been associated with an array of developmental, cognitive, and behavioural deficits in the child.9 10 The effect of opioid exposure during the prenatal period is a topic of substantial importance but requires more in-depth examination.

Various neuropsychiatric disorders begin in childhood and result in established neuropsychiatric disorders later in life.11 Opioid exposure during the prenatal and infancy periods might be an emerging risk factor for neuropsychiatric outcomes. While previous studies reported that exposure to opioids during the prenatal period is associated with neuropsychiatric disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, alcohol misuse, and depression,12 13 others suggest that exposure to opioids during pregnancy may not be deleterious to early childhood neurobehavioural development.14 15 Given the potential confounding factors and limited cohort size in earlier research,16 a more precise investigation with a large scale birth cohort is warranted. Thus, we aimed to examine the association between maternal opioid exposure and the subsequent risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in children using a nationwide, population based, large scale birth cohort in South Korea. We also aimed to investigate the specific neuropsychiatric disorders potentially associated with fetal exposure to opioids.

Methods

Data source

This large scale nationwide cohort study was conducted using data from the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) of South Korea,17 which covers 98% of the South Korean population. Data, including baseline demographic details of individuals, outpatient and inpatient medical records, general health screening, and mortality information were collected through a universal health coverage system that provides comprehensive insurance services.18 This study followed The Reporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement (table S1).

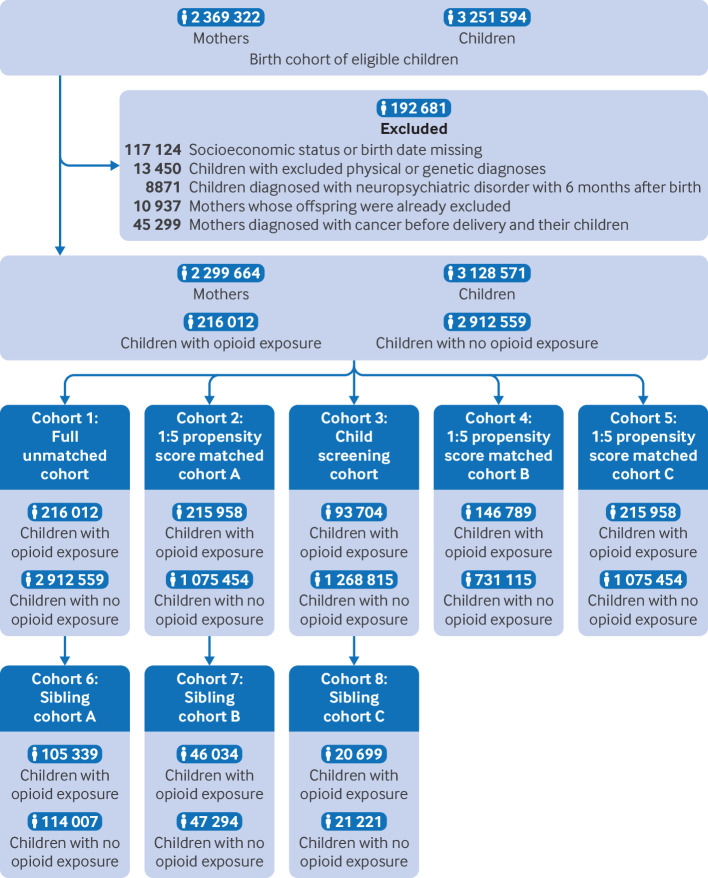

In this study, we focused on children born between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2017. These children were subsequently paired with their mothers using the unique family insurance identification numbers allocated to every individual in the NHIS data (fig 1, figure S1-S4).17 19 The Korean government anonymised all patient related data, including personal identification numbers, to enhance confidentiality. While direct identification of individuals was not possible due to the removal of names, all other pertinent data remained intact and accessible for our analyses. The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Kyung Hee University (KHUH 2022-06-042) and the NHIS (NHIS-2023-1-168). We conducted this study using de-identified administrative data. No consent was required for this type of study.20

Fig 1.

Disposition and study subjects (full version). Cohort 1 involved infants born between 2010 and 2017. Cohort 2 paired the exposed and unexposed groups in a 1:5 ratio using propensity score. Cohort 3 included children from the National Health Screening Program for Infants and Children at six months after birth. Cohort 4 included infants born between 2010 and 2015 with the exposed and unexposed groups matched in a 1:5 ratio. Cohort 5 was where children who received at least one diagnosis based on the outcome criteria were matched in a 1:5 ratio between exposed and unexposed groups. Cohort 6 was a sibling comparison cohort derived from the full unmatched cohort. Cohort 7 was sibling comparison cohort derived from the 1:5 matched cohort A. Cohort 8 was sibling comparison cohort derived from the child screening cohort

Study design and participants

All infants born in South Korean during the study period were included. The cohort comprised 3 251 594 children and 2 369 322 paired mothers. Using unique identification numbers, we paired children with their corresponding mothers (figure S4).21 The data from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2020 were included to ensure follow-up of all medical records within this timeframe. The exclusion criteria applied to the initial cohort are as follows (tables S2 and S3): participants with inadequate information on socioeconomic status (excluded n=66); missing birth dates (excluded n=76 028); children diagnosed with immune mechanism disorders (excluded n=936), cystic fibrosis (excluded n=18), chronic kidney disease (excluded n=388), β thalassemia or sickle cell disorders (excluded n=27), malignancy (excluded n=4116), teratogenic/genetic syndromes, microdeletions, chromosomal abnormalities, and malformation syndromes (excluded n=8015), or neuropsychiatric disorders within six months after birth (excluded n=6871); children of mothers diagnosed with cancer before delivery (excluded n=26 620); and mothers whose offspring were already excluded (excluded n=69 646). The final cohort comprised 3 128 571 children and 2 299 664 mothers.

Exposures

Opioid exposure was defined on the basis of mothers receiving two or more opioid prescriptions within each trimester, following the exposure criteria as per previous studies.5 22 23 Table S4 and figure S5 list the specific opioids included. Based on this definition, the extent of prenatal opioid exposure was classified into three categories. Firstly, based on trimesters of pregnancy, the four groups were defined as opioid use in the first, second, and third trimesters, and more than one trimester. Secondly, total opioid intake was calculated based on morphine milligram equivalents,5 23 and mothers were categorised into non-user, user of low dose, and user of high dose by using the 75th percentile as the cutoff (25.5 morphine milligram equivalents). Thirdly, mothers were grouped according to the number of opioid prescriptions received (0-1, 2, or ≥3) and exposure duration (<30, 30-59, or ≥60 days) over the whole pregnancy. Additionally, we listed maternal health conditions among pregnant women with opioid prescriptions (table S5).

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was the onset of neuropsychiatric disorders in children, defined as having received at least two diagnoses of F00-99 codes as per the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10) (table S2 and S6). In the context of psychiatric diagnoses in South Korea, predominantly psychiatrists, and to a lesser extent, paediatricians, are authorised to diagnose psychiatric conditions and assign the F-code in ICD-10 codes (table S6). Among the identified cases, infants with psychotic features were categorised as having severe neuropsychiatric disorders, whereas the other cases were classified as common neuropsychiatric disorders (table S2).24 The specific diagnoses for children with neuropsychiatric disorders were categorised as follows (table S7): alcohol or drug misuse; mood disorders, excluding those with psychotic symptoms; anxiety and stress-related disorders; eating disorders; compulsive disorders; attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; autism spectrum disorder; and intellectual disability.

Covariates

We considered these covariates related to mothers: maternal age at delivery (<20, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, or ≥35 years), region of residence (rural or urban),25 household income level (first to fourth quartiles), parity (one or ≥two children), maternal mental illness (no mental illness, common, or severe), severe maternal morbidity score (0, 1, or ≥2),26 delivery type (vaginal delivery or caesarean section), opioid prescription history, hospital admission (0, 1, or ≥2), and outpatient visit (0, 1, or ≥2) in the year before pregnancy, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen during pregnancy, and history of maternal neuropsychiatric conditions (alcohol or drug misuse, mood disorders except those with psychotic symptoms, anxiety and stress-related disorders, sleep disorders, epilepsy, and other neuropsychiatry disorders). We considered the following covariates for infants: sex, birth season (spring (March to May), summer (June to August), autumn (September to November), and winter (December to February)), year of delivery (2010-12, 2013-15, or 2016-17), preterm birth (≤36 weeks), low birth weight (≤2499 g), and breastfeeding history. All variables were obtained from eligibility data, claim codes, and child health examination data provided by the NHIS.

Cohorts

We used eight cohorts to comprehensively understand the association between maternal opioid prescriptions and risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in their child as follows: (1) a full unmatched cohort involving infants born between 2010 and 2017 (cohort 1 in fig 1 and table S8); (2) propensity score matched cohort A, derived from the full unmatched cohort, pairing the exposed and unexposed groups in a 1:5 ratio using propensity score (cohort 2 in fig 1 and table S8); (3) the child screening cohort, based on the full unmatched cohort, consisted of children from the National Health Screening Program for Infants and Children at six months after birth (cohort 3 in fig 1 and table S8); (4) propensity score matched cohort B consisting of infants born between 2010 and 2015, with the exposed and unexposed groups matched in a 1:5 ratio (cohort 4 in fig 1 and table S8); (5) propensity score matched cohort C including infants born between 2010 and 2017, forming a cohort where children who received at least one diagnosis based on the outcome criteria are matched in a 1:5 ratio between exposed and unexposed groups (cohort 5 in fig 1 and table S8); and (6) three sibling cohorts each specifically including sibling pairs with differing exposure statuses: sibling cohort A is formed from the full unmatched cohort (cohort 6 in fig 1 and table S8), sibling cohort B is derived from the propensity score matched cohort A (cohort 7 in fig 1 and table S8), and sibling cohort C is based on the child screening cohort (cohort 8 in fig1 and table S8).

Propensity score matched cohort

To mitigate potential confounding and to balance demographic covariates between the groups exposed to opioids and groups not exposed, we created a propensity score matched cohort informed by opioid exposure.27 Propensity score was derived using a univariate logistic regression model, incorporating variables such as maternal age at delivery, region of residence, household income level, parity, maternal mental illness, severe maternal morbidity score, hospital admission, and outpatient visit in the year before pregnancy and history of maternal neuropsychiatric conditions (alcohol or drug misuse, mood disorders except those with psychotic symptoms, anxiety and stress related disorders, sleep disorders, epilepsy, and other neuropsychiatry disorders). Individuals were matched in 1:5 ratio matching between the opioid exposed (matched n=215 958) and unexposed (matched n=1 075 454) groups within the entire cohort. Using the greedy nearest-neighbor algorithm, we randomly matched the two groups based on propensity score values within the specified caliper (0.001), ensuring minimal differences. The appropriateness of propensity score matched was evaluated using standardised mean differences. We considered no substantial imbalance between the two groups when the standardised mean difference was less than 0.1 (figure S6 and S7).27

Child screening cohort

A previous birth cohort study reported significant benefits of breastfeeding on subsequent hospital admissions for infection, gastrointestinal tract, respiratory, genitourinary tract, and oral cavity in children.28 To minimise unmeasured confounding factors, we formed a cohort of children who received the National Health Screening Program for infants and children at six months after birth, enabling us to obtain information on their breastfeeding history (table S9). Individuals with missing breastfeeding data despite having undergone screening were excluded from this cohort. A total of 1 377 246 children were included in the screening cohort (table S10).

Sibling comparison cohort

Sibling comparison analysis provides a suitable approach to counter potential biases arising from unmeasured confounding factors, such as genetics, lifestyle, and environmental influences.29 In all cohorts (full unmatched, propensity score matched, and child screening cohorts), we established sibling comparison cohorts for sibling pairs with different exposure statuses. Pairs of only children or siblings sharing uniform opioid exposure or no exposure were systematically excluded.

Other analyses

To enhance our findings, we conducted additional analyses using different follow-up duration and criteria for outcome. We first further investigated the prolonged effects of maternal opioid prescriptions by utilising 1:5 propensity score matched cohort B of children, born between 2010 and 2015 (figure S3, S7, and table S11). Then, to ascertain the robustness of our findings, we reanalysed using a 1:5 propensity score matched cohort C, defining the outcome by at least one diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Across all cohort analyses, the primary exposure was prenatal opioid exposure, and the primary outcome was the onset of neuropsychiatric disorders in children. We designated each childbirth date as the index date. Follow-up continued until the first diagnosis of neuropsychiatric disorder, 31 December 2020 (end of the study period), or the date of death, whichever occurred first.

Hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using Cox proportional hazards model for estimation. Additionally, to control for the influence of potential confounders and to strengthen the validity of the results, two adjusted models were developed using the following variables. Firstly, for the adjusted model, maternal age at delivery years, infant’s sex, region of residence, household income level, birth season, parity, maternal mental illness, severe maternal morbidity score, and hospital outpatient visit as well as hospital admission contact in a year before pregnancy were used. And secondly, for the fully adjusted model, covariates of the adjusted model were used in addition to history of maternal neuropsychiatric conditions (alcohol or drug misuse, mood disorders except those with psychotic symptoms, anxiety and stress related disorders, sleep disorders, epilepsy, and other neuropsychiatry disorders), and use of NSAIDs as well as acetaminophen during pregnancy. We further adjusted for breastfeeding history in the child screening cohort. To reduce unpredictable biases and reverse causality, we conducted a stratification analysis using variables. A dose dependent analysis was conducted to elucidate the association between opioid use and onset of neuropsychiatric disorders. Furthermore, we explored a potential association between specific factors (maternal health condition, opioid prescription a year before pregnancy, and delivery type) and opioid prescriptions during pregnancy by a multiplicative interaction analysis. We used Cox models that included multiplicative interaction terms between opioid prescriptions during pregnancy and each factor (tables S12-14).30 All statistical inferences were considered significant at a two sided Pvalue of less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Patient and public involvement

The Korean government anonymised all patient related data, including personal identification numbers, to enhance confidentiality. While direct identification of individuals was rendered impossible due to the removal of names, all other pertinent data remained intact and accessible for our analyses. Due to the database containing data for the national population, access was limited to participating researchers only for security and confidentiality purposes. The research questions and outcome measures were independently determined without the involvement of the children or their parents. The study design and implementation were conducted without consultation. In South Korea, no framework for the management of patient and public involvement has been established. However, the results of the study will be officially registered and released to NHIS (the official institutions of the Korean government) and we plan to disseminate the results of this study to all study participants and wider relevant communities on request.

Results

Of 2 299 664 mothers included in the study, 3 128 571 infants were linked and we identified 93.1% (n=2 912 559) infants with no prenatal opioid exposure (51.3% male, 48.7% female) and 6.9% (n=216 012) infants with prenatal opioid exposure (51.2% male, 48.8% female) in the full matched cohort within follow-up periods from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2020 (fig 1; table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study subjects from 2010 to 2017

| Characteristics | Full unmatched cohort (n=3 128 571)* | Propensity score matched cohort A (n=1 291 412)† | Standardised mean difference‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children with prenatal opioid exposure | Children without prenatal exposure | Children with prenatal opioid exposure | Children without prenatal exposure | |||

| Total, no | 216 012 | 2 912 559 | 215 958 | 1 075 454 | — | |

| Matching variables | ||||||

| Maternal characteristics: | ||||||

| Maternal age at delivery year, mean (SD) | 32.3 (4.2) | 31.9 (4.2) | 32.3 (4.2) | 32.3 (4.1) | 0.01 | |

| Maternal age at delivery year, no (%) | <0.01 | |||||

| ≤19 | 545 (0.3) | 7330 (0.3) | 545 (0.3) | 2558 (0.2) | ||

| 20-24 | 7992 (3.7) | 128 697 (4.4) | 7991 (3.7) | 39 487 (3.7) | ||

| 25-29 | 41 094 (19.0) | 633 948 (21.8) | 41 090 (19.0) | 204 847 (19.1) | ||

| 30-34 | 102 874 (47.6) | 1 393 988 (47.9) | 102 855 (47.6) | 512 850 (47.7) | ||

| ≥35 | 63 507 (29.4) | 748 596 (25.7) | 63 477 (29.4) | 315 712 (29.4) | ||

| Region of residence, no (%) | <0.01 | |||||

| Rural | 90 163 (41.7) | 1 262 028 (43.3) | 90 146 (41.7) | 449 082 (41.8) | ||

| Urban | 125 849 (58.3) | 1 650 531 (56.7) | 125 812 (58.3) | 626 372 (58.2) | ||

| Income level, no (%) | <0.01 | |||||

| 1st quartile | 50 684 (23.5) | 649 207 (22.3) | 50 664 (23.5) | 251 255 (23.4) | ||

| 2nd quartile | 55 788 (25.8) | 750 159 (25.8) | 55 775 (25.8) | 277 762 (25.8) | ||

| 3rd quartile | 54 441 (25.2) | 733 069 (25.2) | 54 428 (25.2) | 271 342 (25.2) | ||

| 4th quartile | 55 099 (25.5) | 780 124 (26.8) | 55 091 (25.5) | 275 095 (25.6) | ||

| Parity, no (%) | <0.01 | |||||

| 1 | 181 261 (83.9) | 2 217 878 (76.2) | 181 212 (83.9) | 902 974 (84.0) | ||

| ≥2 | 34 751 (16.1) | 694 681 (23.9) | 34 746 (16.1) | 172 480 (16.0) | ||

| Maternal medical conditions, no (%) | 0.01 | |||||

| No mental illness | 168 482 (78.0) | 2 473 110 (84.9) | 168 481 (78.0) | 842 539 (78.3) | ||

| Common | 42 533 (19.7) | 398 371 (13.7) | 42 513 (19.7) | 210 059 (19.5) | ||

| Severe | 4997 (2.3) | 41 078 (1.4) | 4964 (2.3) | 22 856 (2.1) | ||

| Severe maternal morbidity, no (%) | <0.01 | |||||

| 0 | 198 017 (91.7) | 2 731 862 (93.8) | 198 009 (91.7) | 988 081 (91.9) | ||

| 1 | 17 332 (8.0) | 175 983 (6.0) | 17 306 (8.0) | 84 666 (7.9) | ||

| ≥2 | 663 (0.3) | 4714 (0.2) | 643 (0.3) | 2707 (0.3) | ||

| No of hospital admissions in a year before pregnancy, no (%) | <0.01 | |||||

| 0 | 171 976 (79.6) | 2 468 433 (84.8) | 171 966 (79.6) | 859 082 (79.9) | ||

| 1 | 35 213 (16.3) | 370 988 (12.7) | 35 203 (16.3) | 174 627 (16.2) | ||

| ≥2 | 8823 (4.1) | 73 138 (2.5) | 8789 (4.1) | 41 745 (3.9) | ||

| No of outpatient contacts in a year before pregnancy, no (%) | <0.01 | |||||

| 0 | 4619 (2.1) | 188 625 (6.5) | 4616 (2.1) | 23 009 (2.1) | ||

| 1 | 4890 (2.3) | 162 503 (5.6) | 4890 (2.3) | 24 369 (2.3) | ||

| ≥2 | 206 503 (95.6) | 2 561 431 (87.9) | 206 452 (95.6) | 1 028 076 (95.6) | ||

| Alcohol or drug misuse, no (%) | 558 (0.3) | 3920 (0.1) | 540 (0.3) | 1980 (0.2) | 0.01 | |

| Mood disorders except those with psychotic symptoms, no (%) | 9699 (4.5) | 74 053 (2.5) | 9658 (4.5) | 45 415 (4.2) | 0.01 | |

| Anxiety and stress-related disorders, no (%) | 16 195 (7.5) | 129 873 (4.5) | 16 150 (7.5) | 77 673 (7.2) | 0.01 | |

| Sleep disorders, no (%) | 8392 (3.9) | 59 394 (2.0) | 8347 (3.9) | 38 962 (3.6) | 0.01 | |

| Epilepsy, no (%) | 884 (0.4) | 8696 (0.3) | 870 (0.4) | 3691 (0.3) | 0.01 | |

| Other neuropsychiatry disorders, no (%) | 814 (0.4) | 6713 (0.2) | 805 (0.4) | 3369 (0.3) | 0.01 | |

| Unmatching variables | ||||||

| Delivery type, no (%): | 0.16 | |||||

| Vaginal delivery | 115 193 (53.3) | 1 693 716 (58.2) | 115 174 (53.3) | 659 523 (61.3) | ||

| Caesarean section | 100 819 (46.7) | 1 218 843 (41.9) | 100 784 (46.7) | 415 931 (38.7) | ||

| Use of NSAIDs during pregnancy, no (%) | 103 912 (48.1) | 482 329 (16.6) | 103 877 (48.1) | 204 829 (19.1) | 0.65 | |

| Use of acetaminophen during pregnancy, no (%) | 148 024 (68.5) | 789 528 (27.1) | 147 981 (68.5) | 328 716 (30.6) | 0.82 | |

| Infant characteristics: | ||||||

| Infant sex, no (%) | <0.01 | |||||

| Male | 110 511 (51.2) | 1 495 374 (51.3) | 110 487 (51.2) | 551 281 (51.3) | ||

| Female | 105 501 (48.8) | 1 417 185 (48.7) | 105 471 (48.8) | 524 173 (48.7) | ||

| Birth season, no (%) | 0.07 | |||||

| Spring | 53 228 (24.6) | 756 304 (26.0) | 53 214 (24.6) | 279 000 (25.9) | ||

| Summer | 58 458 (27.1) | 708 808 (24.3) | 58 434 (27.1) | 261 523 (24.3) | ||

| Autumn | 51 697 (23.9) | 718 496 (24.7) | 51 687 (23.9) | 268 571 (25.0) | ||

| Winter | 52 629 (24.4) | 728 951 (25.0) | 52 623 (24.4) | 266 360 (24.8) | ||

| Year of delivery, no (%) | 0.11 | |||||

| 2010 to 2012 | 69 885 (32.4) | 1 119 845 (38.5) | 69 874 (32.4) | 400 367 (37.2) | ||

| 2013 to 2015 | 76 973 (35.6) | 997 353 (34.2) | 76 952 (35.6) | 378 610 (35.2) | ||

| 2016 to 2017 | 69 154 (32.0) | 795 361 (27.3) | 69 132 (32.0) | 296 477 (27.6) | ||

| At-risk newborn, no (%) | 0.07 |

|||||

| Preterm birth | 10 817 (5.0) | 103 949 (3.6) | 203 182 (94.1) | 1 028 054 (95.6) | ||

| Low birth weight | 7860 (3.6) | 83 354 (2.9) | 12 776 (5.9) | 47 400 (4.4) | ||

NSAIDs=non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SD=standard deviation.

Full unmatched cohort involves infants born between 2010 and 2017 (cohort 1 in fig 1 and table S8).

Propensity score matched cohort A, derived from the full unmatched cohort, involves a 1:5 matching ratio and pairs the exposed and unexposed groups in a 1:5 ratio using propensity score (cohort 2 in fig 1 and table S8).

Standardised mean difference of <0.1 corresponds to no major imbalance.

After 1:5 propensity score matching, the standardised mean difference values were less than 0.1, indicating no major imbalances in the general characteristics. The association between maternal exposure to opioids and neuropsychiatric outcomes in the offspring from the subgroup analysis is indicated as crude and adjusted hazard ratio in table 2 and table S15. Prenatal exposure to opioids was associated with an increased risk of neuropsychiatric disorders (fully adjusted hazard ratio 1.07 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.10), table 2). In particular, exposure to opioids during the first trimester showed an increased risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in the offspring compared with the offspring who was not exposed (1.11 (1.07 to 1.15)). Risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in the offspring increased in a dose-dependent manner with opioid doses (low dose 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09); high dose, 1.15 (1.09 to 1.21)). Compared with infants who were not exposed, the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in infants who were exposed showed increasing trends depending on the days of opioid prescriptions (1-29 days of opioid prescriptions, 1.07 (1.04 to 1.10); 30-59 days, 1.34 (1.12 to 1.62); ≥60 days, 1.95 (1.24 to 3.06)). In addition, similar trends were reported in further analysis by using different timeframes of infants born between 2010 to 2015 and different outcome criteria with one or more instances of diagnosis (tables S16 and S17). We performed stratification analysis in the 1:5 propensity score matched cohort A (table 3). The subsequent risk of neuropsychiatric disorders with maternal opioid use was significantly associated with caesarean sections in comparison to vaginal deliveries (P value for interaction=0.009; ratio of hazard ratio 1.08 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.14); table S14).

Table 2.

Hazard ratio models of the association between prenatal opioid exposure during pregnancy and neuropsychiatric disorders in children with the 1:5 propensity score matched cohort A from 2010 to 2017

| Outcome | No (%) | Neuropsychiatric disorder events (%) | Person years | Neuropsychiatric incidence rate, per 1000 years | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted† | Fully adjusted‡ | |||||

| Opioid exposure during pregnancy: | |||||||

| No | 1 075 454 (83.3) | 36 648 (3.4) | 6 650 015 | 5.5 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 215 958 (16.7) | 7398 (3.4) | 1 271 953 | 5.8 | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.10)* | 1.08 (1.05 to 1.11)* | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.10)* |

| Timing of opioid exposure: | |||||||

| No opioid exposure | 1 075 454 (83.3) | 36 648 (3.4) | 6 650 015 | 5.5 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| First trimester only | 87 567 (6.8) | 3327 (3.8) | 532 956 | 6.2 | 1.15 (1.11 to 1.19)* | 1.12 (1.08 to 1.16)* | 1.11 (1.07 to 1.15)* |

| Second trimester only | 50 765 (3.9) | 1599 (3.2) | 290 988 | 5.5 | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.07) | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.09) | 1.04 (0.98 to 1.09) |

| Third trimester only | 61 122 (4.7) | 1863 (3.1) | 354 590 | 5.3 | 0.96 (0.92 to 1.01) | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.05) | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.06) |

| More than one trimester | 16 504 (1.3) | 609 (3.7) | 93 419 | 6.5 | 1.21 (1.12 to 1.31)* | 1.25 (1.15 to 1.35)* | 1.21 (1.11 to 1.31)* |

| Dose-dependent association, MME: | |||||||

| None | 1 075 454 (83.3) | 36 648 (3.4) | 6 650 015 | 5.5 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Low dose user | 161 695 (12.5) | 5732 (3.5) | 1 000 524 | 5.7 | 1.04 (1.01 to 1.07)* | 1.05 (1.02 to 1.08)* | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09)* |

| High dose user | 54 263 (4.2) | 1666 (3.1) | 271 429 | 6.1 | 1.18 (1.12 to 1.24)* | 1.18 (1.12 to 1.24)* | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.21)* |

| Opioid prescriptions, days: | |||||||

| 0 | 1 075 454 (83.3) | 36 648 (3.4) | 6 650 015 | 5.5 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 1-29 | 212 839 (16.5) | 7267 (3.4) | 1 255 284 | 5.8 | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.09)* | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.10)* | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.10)* |

| 30-59 | 2824 (0.2) | 112 (4.0) | 15 196 | 7.4 | 1.39 (1.15 to 1.67)* | 1.44 (1.20 to 1.73)* | 1.34 (1.12 to 1.62)* |

| ≥60 | 295 (0.0) | 19 (6.4) | 1,473 | 12.9 | 2.54 (1.62 to 3.97)* | 2.53 (1.62 to 3.96)* | 1.95 (1.24 to 3.06)* |

| No of opioid prescriptions: | |||||||

| 0-1 | 1 075 454 (83.3) | 36 648 (3.4) | 6 650 015 | 5.5 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 2 | 104 991 (8.1) | 3508 (3.3) | 626 586 | 5.6 | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.06) | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.06) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.07) |

| ≥3 | 110 967 (8.6) | 3890 (3.5) | 645 367 | 6.0 | 1.11 (1.08 to 1.15)* | 1.13 (1.09 to 1.17)* | 1.12 (1.08 to 1.16)* |

CI=confidence interval; MME=morphine milligram equivalent.

Propensity score matched cohort A, derived from the full unmatched cohort, involves a 1:5 matching ratio and pairs the exposed and unexposed groups in a 1:5 ratio using propensity score (cohort 2 in fig 1 and table S8).

Significant differences (P<0.05).

The adjusted model was adjusted for the following variables: maternal age at delivery years (≤19, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, and ≥35 years), infant sex, region of residence (urban and rural), household income level (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartiles), birth season (spring, summer, autumn, and winter), parity (1 and ≥2), maternal mental illness, severe maternal morbidity score (0, 1, and ≥2), and hospital outpatient visit (0, 1, and ≥2), and admission contact (0, 1, and ≥2) in a year before pregnancy.

The fully adjusted model was adjusted for the following variables: covariates as in the adjusted model, history of maternal neuropsychiatric conditions (alcohol or drug misuse, mood disorders except those with psychotic symptoms, anxiety and stress-related disorders, sleep disorders, epilepsy, and other neuropsychiatry disorders), and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen during pregnancy.

Table 3.

Stratification analysis for hazard ratio models of the association between opioid exposure during pregnancy and neuropsychiatric disorders in children with the 1:5 propensity score matched cohort A from 2010 to 2017

| Variables | No (%) | Neuropsychiatric disorder events (%) | Person years | Neuropsychiatric incidence rate, per 1000 years | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted† | Fully adjusted‡ | |||||

| Infant’s sex: | |||||||

| Male | 110 487 (51.2) | 5139 (4.7) | 647 771 | 7.9 | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09)* | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09)* | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09)* |

| Female | 105 471 (48.8) | 2259 (2.1) | 624 182 | 3.6 | 1.11 (1.06 to 1.16)* | 1.11 (1.06 to 1.17)* | 1.11 (1.06 to 1.16)* |

| Season of birth: | |||||||

| Spring | 53 214 (24.6) | 1731 (3.3) | 308 294 | 5.6 | 1.10 (1.04 to 1.15)* | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.17)* | 1.10 (1.05 to 1.16)* |

| Summer | 58 434 (27.1) | 2061 (3.5) | 345 916 | 6.0 | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.14)* | 1.10 (1.04 to 1.15)* | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.15)* |

| Autumn | 51 687 (23.9) | 1838 (3.6) | 307 232 | 6.0 | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.08) | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.09) | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.08) |

| Winter | 52 623 (24.4) | 1768 (3.4) | 310 511 | 5.7 | 1.07 (1.02 to 1.13)* | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.13)* | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.13)* |

| Year of delivery: | |||||||

| 2010-12 | 69 874 (32.4) | 4315 (6.2) | 604 966 | 7.1 | 1.11 (1.07 to 1.15)* | 1.11 (1.07 to 1.14)* | 1.10 (1.07 to 1.14)* |

| 2013-15 | 76 952 (35.6) | 2300 (3.0) | 455 484 | 5.0 | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.09) | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.09) | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.09) |

| 2016-17 | 69 132 (32.0) | 783 (1.1) | 211 503 | 3.7 | 1.02 (0.94 to 1.10) | 1.03 (0.95 to 1.11) | 1.03 (0.95 to 1.11) |

| Maternal medical conditions: | |||||||

| No mental illness | 168 481 (78.0) | 4437 (2.6) | 989 756 | 4.5 | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.10)* | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.10)* | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.10)* |

| Mental illness | 47 477 (22.0) | 2961 (6.2) | 282 197 | 10.5 | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.11)* | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.11)* | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.11)* |

| Delivery type: | |||||||

| Vaginal delivery | 115 174 (53.3) | 3722 (3.2) | 695 745 | 5.3 | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.07) | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.08) | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.08) |

| Caesarean section | 100 784 (46.7) | 3676 (3.7) | 576 208 | 6.4 | 1.09 (1.05 to 1.13)* | 1.13 (1.09 to 1.17)* | 1.12 (1.08 to 1.17)* |

| Medical condition of infant: | |||||||

| None | 203 182 (94.1) | 6690 (3.3) | 1 202 303 | 5.6 | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.08)* | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09)* | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09)* |

| At risk newborn | 12 776 (5.9) | 708 (5.5) | 69 650 | 10.2 | 1.11 (1.02 to 1.21)* | 1.12 (1.03 to 1.22)* | 1.11 (1.02 to 1.20)* |

| History of maternal neuropsychiatric conditions: | |||||||

| Alcohol or drug misuse: | |||||||

| No | 215 418 (99.8) | 7342 (3.4) | 1 269 466 | 5.8 | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.09)* | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.10)* | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.10)* |

| Yes | 540 (0.3) | 56 (10.4) | 2487 | 22.5 | 2.07 (1.50 to 2.86)* | 2.06 (1.49 to 2.85)* | 2.07 (1.50 to 2.86)* |

| Mood disorders except those with psychotic symptoms: | |||||||

| No | 206 300 (95.5) | 6859 (3.3) | 1 224 738 | 5.6 | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09)* | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.10)* | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.10)* |

| Yes | 9658 (4.5) | 539 (5.6) | 47 215 | 11.4 | 1.17 (1.06 to 1.28)* | 1.18 (1.07 to 1.29)* | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.28)* |

| Anxiety and stress related disorders: | |||||||

| No | 199 808 (92.5) | 6646 (3.3) | 1 190 172 | 5.6 | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09)* | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.10)* | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.10)* |

| Yes | 16 150 (7.5) | 752 (4.7) | 81 781 | 9.2 | 1.14 (1.05 to 1.23)* | 1.14 (1.05 to 1.24)* | 1.13 (1.04 to 1.22)* |

| Sleep disorders: | |||||||

| No | 207 611 (96.1) | 6967 (3.4) | 1 231 480 | 5.7 | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09)* | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.09)* | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.09)* |

| Yes | 8347 (3.9) | 431 (5.2) | 40 473 | 10.6 | 1.26 (1.14 to 1.40)* | 1.26 (1.13 to 1.40)* | 1.24 (1.12 to 1.38)* |

| Epilepsy: | |||||||

| No | 215 088 (99.6) | 7333 (3.4) | 1 267 586 | 5.8 | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.10)* | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.10)* | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.10)* |

| Yes | 870 (0.4) | 65 (7.5) | 4,367 | 14.9 | 1.52 (1.15 to 2.01)* | 1.58 (1.19 to 2.09)* | 1.53 (1.15 to 2.02)* |

| Other neuropsychiatry disorders: | |||||||

| No | 215 153 (99.6) | 7331 (3.4) | 1 268 373 | 5.8 | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.10)* | 1.08 (1.05 to 1.10)* | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.10)* |

| Yes | 805 (0.4) | 67 (8.3) | 3,580 | 18.7 | 1.39 (1.06 to 1.83)* | 1.45 (1.10 to 1.91)* | 1.43 (1.08 to 1.88)* |

| Use of NSAIDs during pregnancy: | |||||||

| No | 112 081 (51.9) | 3419 (3.1) | 651 988 | 5.2 | 1.00 (0.97 to 1.04) | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.06) | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.06) |

| Yes | 103 877 (48.1) | 3979 (3.8) | 619 965 | 6.4 | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.07) | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.07) | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.08) |

| Use of acetaminophen during pregnancy: | |||||||

| No | 67 977 (31.5) | 1443 (2.1) | 295 299 | 4.9 | 1.02 (0.97 to 1.08) | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.11) | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.11) |

| Yes | 147 981 (68.5) | 5955 (4.0) | 976 654 | 6.1 | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.06) | 1.04 (1.01 to 1.07)* |

CI=confidence interval; NSAIDs=non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Propensity score matched cohort A, derived from the full unmatched cohort, involves a 1:5 matching ratio and pairs the exposed and unexposed groups in a 1:5 ratio using propensity score (cohort 2 in fig 1 and table S8).

Significant differences (P<0.05).

The adjusted model was adjusted for the following variables: maternal age at delivery years (≤19, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, and ≥35 years), infant sex, region of residence (urban and rural), household income level (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartiles), birth season (spring, summer, autumn, and winter), parity (1 and ≥2), maternal mental illness, severe maternal morbidity score (0, 1, and ≥2), and hospital outpatient visit (0, 1, and ≥2), and admission contact (0, 1, and ≥2) in a year before pregnancy.

The fully adjusted model was adjusted for the following variables: covariates as in the adjusted model, history of maternal neuropsychiatric conditions (alcohol or drug misuse, mood disorders except those with psychotic symptoms, anxiety and stress related disorders, sleep disorders, epilepsy, and other neuropsychiatry disorders), and use of NSAIDs and acetaminophen during pregnancy.

Table 4 and table S18 present the results of a dose-dependent subgroup analysis of the association between maternal opioid use during pregnancy and the risk of specific neuropsychiatric disorders in children from the full and 1:5 propensity score matched cohorts. Compared with infants who were not exposed to opioids, maternal opioid use significantly increased the risk of several neuropsychiatric diseases, including mood disorder (adjusted hazard ratio 1.15 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.26)), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (1.12 (1.07 to 1.17)), and intellectual disability (1.30 (1.21 to 1.40)), but not risk of alcohol or drug misuse, anxiety and stress related disorders, eating disorders, compulsive disorders, and autism spectrum disorder. In particular, the risk of severe neuropsychiatric disorder in the infant (1.30 (1.15 to 1.46)) was higher than that of common neuropsychiatric disorders (1.07 (1.04 to 1.09)) among those who had maternal exposure to opioids.

Table 4.

Adjusted hazard ratio models of the dose-dependence between prenatal opioid exposure during pregnancy and specific neuropsychiatric disorders in children within the 1:5 propensity score matched cohort A from 2010 to 2017

| Outcome | Overall | Low dose users (<25.5 MME) | High dose users (≥25.5 MME) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events, no (%) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)† |

Fully adjusted HR (95% CI)‡ |

Events, n (%) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)† |

Fully adjusted HR (95% CI)‡ |

Events, n (%) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)† |

Fully adjusted HR (95% CI)‡ |

|||

| Alcohol or drug misuse: | |||||||||||

| No opioid exposure | 94/1 075 454 (0.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 94/1 075 454 (0.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 94/1 075 454 (0.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Opioid exposure | 15/215 958 (0.0) | 0.81 (0.47 to 1.40) | 0.81 (0.47 to 1.40) | 14/161 695 (0.0) | 0.98 (0.56 to 1.72) | 0.98 (0.56 to 1.73) | 1/54 263 (0.0) | 0.24 (0.03 to 1.72) | 0.24 (0.03 to 1.71) | ||

| Mood disorders, excluding those with psychotic symptoms: | |||||||||||

| No opioid exposure | 2594/1 075 454 (0.2) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 2594/1 075 454 (0.2) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 2594/1 075 454 (0.2) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Opioid exposure | 535/215 958 (0.3) | 1.15 (1.05 to 1.27)* | 1.15 (1.04 to 1.26)* | 418/161 695 (0.3) | 1.12 (1.01 to 1.24)* | 1.12 (1.01 to 1.24)* | 117/54 263 (0.2) | 1.29 (1.07 to 1.55)* | 1.24 (1.03 to 1.50)* | ||

| Anxiety and stress-related disorders: | |||||||||||

| No opioid exposure | 4772/1 075 454 (0.4) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 4772/1 075 454 (0.4) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 4772/1 075 454 (0.4) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Opioid exposure | 932/215 958 (0.4) | 1.07 (0.99 to 1.14) | 1.06 (0.99 to 1.14) | 733/161 695 (0.5) | 1.05 (0.97 to 1.13) | 1.05 (0.97 to 1.14) | 199/54 263 (0.4) | 1.14 (0.99 to 1.31) | 1.10 (0.95 to 1.27) | ||

| Eating disorders: | |||||||||||

| No opioid exposure | 157/1 075 454 (0.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 157/1 075 454 (0.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 157/1 075 454 (0.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Opioid exposure | 21/215 958 (0.0) | 0.70 (0.44 to 1.10) | 0.70 (0.44 to 1.10) | 16/161 695 (0.0) | 0.68 (0.40 to 1.13) | 0.68 (0.41 to 1.13) | 5/54 263 (0.0) | 0.80 (0.33 to 1.96) | 0.78 (0.32 to 1.91) | ||

| Compulsive disorders: | |||||||||||

| No opioid exposure | 379/1 075 454 (0.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 379/1 075 454 (0.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 379/1 075 454 (0.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Opioid exposure | 56/215 958 (0.0) | 0.84 (0.63 to 1.11) | 0.83 (0.63 to 1.10) | 42/161 695 (0.0) | 0.78 (0.56 to 1.07) | 0.78 (0.57 to 1.07) | 14/54 263 (0.0) | 1.09 (0.64 to 1.86) | 1.06 (0.62 to 1.81) | ||

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: | |||||||||||

| No opioid exposure | 12 170/1 075 454 (1.1) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 12 170/1 075 454 (1.1) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 12 170/1 075 454 (1.1) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Opioid exposure | 2452/215 958 (1.1) | 1.12 (1.07 to 1.17)* | 1.12 (1.07 to 1.16)* | 1953/161 695 (1.2) | 1.11 (1.06 to 1.16)* | 1.11 (1.06 to 1.16)* | 499/54 263 (0.9) | 1.18 (1.08 to 1.29)* | 1.14 (1.04 to 1.25)* | ||

| Autism spectrum disorder: | |||||||||||

| No opioid exposure | 5533/1 075 454 (0.5) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 5533/1 075 454 (0.5) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 5533/1 075 454 (0.5) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Opioid exposure | 1072/215 958 (0.5) | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.07) | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.07) | 817/161 695 (0.5) | 0.97 (0.90 to 1.05) | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.05) | 255/54 263 (0.5) | 1.10 (0.97 to 1.25) | 1.09 (0.96 to 1.23) | ||

| Intellectual disability: | |||||||||||

| No opioid exposure | 3554/1 075 454 (0.3) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 3554/1 075 454 (0.3) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 3554/1 075 454 (0.3) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Opioid exposure | 864/215 958 (0.4) | 1.31 (1.21 to 1.41)* | 1.30 (1.21 to 1.40)* | 651/161 695 (0.4) | 1.23 (1.13 to 1.34)* | 1.23 (1.13 to 1.34)* | 213/54 263 (0.4) | 1.63 (1.42 to 1.87)* | 1.59 (1.39 to 1.83)* | ||

| Common neuropsychiatric disorder: | |||||||||||

| No opioid exposure | 35 294/1 074 100 (3.3) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 35 294/1 074 100 (3.3) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 35 294/1 074 100 (3.3) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Opioid exposure | 7080/215 640 (3.3) | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.10)* | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.09)* | 5479/161 442 (3.4) | 1.04 (1.01 to 1.07)* | 1.05 (1.02 to 1.08)* | 1601/54 198 (3.0) | 1.17 (1.11 to 1.23)* | 1.14 (1.09 to 1.20)* | ||

| Severe neuropsychiatric disorder: | |||||||||||

| No opioid exposure | 1354/1 040 160 (0.1) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1354/1 040 160 (0.1) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1354/1 040 160 (0.1) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Opioid exposure | 318/208 878 (0.2) | 1.30 (1.15 to 1.47)* | 1.30 (1.15 to 1.46)* | 253/156 216 (0.2) | 1.29 (1.13 to 1.47)* | 1.29 (1.13 to 1.48)* | 65/52 662 (0.1) | 1.36 (1.06 to 1.74)* | 1.31 (1.02 to 1.68)* | ||

CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio; MME=morphine milligram equivalents.

Propensity score matched cohort A, derived from the full unmatched cohort, involves a 1:5 matching ratio and pairs the exposed and unexposed groups in a 1:5 ratio using propensity score (cohort 2 in fig 1 and table S8).

Significant differences (P<0.05).

The adjusted model was adjusted for the following variables: maternal age at delivery years (≤19, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, and ≥35 years), infant sex, region of residence (urban and rural), household income level (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartiles), birth season (spring, summer, autumn, and winter), parity (1 and ≥2), maternal mental illness, severe maternal morbidity score (0, 1, and ≥2), and hospital outpatient visit (0, 1, and ≥2), and admission contact (0, 1, and ≥2) in a year before pregnancy.

The fully adjusted model was adjusted for the following variables: covariates as in the adjusted model, history of maternal neuropsychiatric conditions (alcohol or drug misuse, mood disorders except those with psychotic symptoms, anxiety and stress-related disorders, sleep disorders, epilepsy, and other neuropsychiatry disorders), and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen during pregnancy.

Sibling analysis, which was performed to control for unmeasured familial confounders, showed no association between prenatal exposure to opioids and the risk of childhood neuropsychiatric disorders in the full unmatched, propensity score matched, and child screening cohorts (table 5). Similar associations were observed when performing the same analysis in the full unmatched (tables S19-22) and child screening cohorts stratified by breastfeeding history (table S23-26). No significant associations were noted between breastfeeding and subsequent risk for neuropsychiatric disorders (table S24).

Table 5.

Crude and adjusted hazard ratio models of the association between opioid exposure during pregnancy and neuropsychiatric disorders in children with the sibling comparison cohort from full unmatched cohort, propensity score matched cohort A, and child screening cohort from 2010 to 2017

| Opioid exposure during pregnancy | No (%) | Neuropsychiatric disorder events (%) | Person years | Neuropsychiatric incidence rate, per 1000 person years | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude* | Adjusted† | Fully adjusted‡ | |||||

| Sibling cohort A from the full unmatched cohort: | |||||||

| No exposure | 114 007 (52.0) | 5008 (4.4) | 760 040 | 6.6 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Exposure | 105 339 (48.0) | 2754 (2.6) | 566 329 | 4.9 | 0.78 (0.73 to 0.82)* | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.07) | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.07) |

| Sibling cohort B from the propensity score matched cohort A: | |||||||

| No exposure | 47 294 (50.7) | 2049 (4.3) | 303 650 | 6.9 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Exposure | 46 034 (49.3) | 1391 (3.0) | 255 035 | 5.7 | 0.89 (0.82 to 0.97)* | 1.04 (0.93 to 1.16) | 1.03 (0.92 to 1.16) |

| Sibling cohort C from the child screening cohort: | |||||||

| No exposure | 21 221 (50.6) | 1066 (5.0) | 152 981 | 7.0 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Exposure | 20 699 (49.4) | 585 (2.8) | 121 848 | 4.8 | 0.72 (0.63 to 0.80)* | 0.95 (0.82 to 1.12) | 0.95 (0.81 to 1.11) |

CI=confidence interval; MME= morphine milligram equivalents.

Significant differences (P<0.05).

The adjusted model was adjusted for the following variables: maternal age at delivery years (≤19, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, and ≥35 years), infant sex, region of residence (urban and rural), household income level (1st, 2nd, 3rd, or 4th quartiles), birth season (spring, summer, autumn, or winter), parity (1 or ≥2), maternal mental illness, severe maternal morbidity score (0, 1, or ≥2), and hospital outpatient visit (0, 1, or ≥2), and admission contact (0, 1, or ≥2) in a year before pregnancy.

The fully adjusted model was adjusted for the following variables: covariates as in the adjusted model, history of maternal neuropsychiatric conditions (alcohol or drug misuse, mood disorders except those with psychotic symptoms, anxiety and stress related disorders, sleep disorders, epilepsy, and other neuropsychiatry disorders), and use of NSAIDs and acetaminophen during pregnancy.

Discussion

Findings and explanation

We investigated the effect of prenatal exposure to opioids on neuropsychiatric disorders in the child and obtained several key findings. Firstly, in this large scale nationwide cohort study that included 216 012 pregnancies that were exposed to opioids among 3 128 571 pregnancies overall, maternal opioid use was not associated with a substantially increased risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in the offspring. Although a statistically significant association (adjusted hazard ratio 1.06 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.09)) was observed between maternal opioid use and neuropsychiatric disorders in the offspring, the clinical significance of this finding is potentially limited due to the observational nature of the study. Similarly, the attenuated and null estimates observed in the sibling controlled analyses support the finding that prenatal opioid exposure was not associated with an increased risk of neuropsychiatric outcomes. Secondly, the timing of opioid exposure may have resulted in different outcomes. Using opioids during the first trimester showed a 11% increased risk of psychiatric disorders compared with no exposure. This specific effect of the first trimester suggests that the effect of opioid use on the fetus during the early neurodevelopmental phase is critical.31 32 Thirdly, the risk of childhood neuropsychiatric disorders showed a dose-dependent association with maternal opioid dose and duration of opioid intake. The risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in the child increased with the number of opioid prescriptions and days of opioid prescriptions. In particular, long term prescriptions (≥60 days) were associated with a nearly doubled risk. Fourthly, offspring delivered via caesarean section had a significant risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in stratification analysis compared with vaginal delivery. Finally, compared with children who were not exposed to opioids, those who were exposed to prenatal opioids had a modestly increased risk of several neuropsychiatric disorders, including mood disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and intellectual disability. However, no associated risk was found for alcohol or drug misuse, anxiety and stress related disorders, eating disorders, compulsive disorders, or autism spectrum disorder. Furthermore, prenatal opioid exposure was associated with a 16% increased risk of severe neuropsychiatric disorders, significantly higher than the 3% increased risk of common neuropsychiatric disorders.

Comparison with other studies

Previous studies explored the association between maternal opioid use and various health outcomes in the offspring5 23 33; however, investigations specifically focusing on neuropsychiatric disorders are limited. A few studies reported no association between maternal opioid use and the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in the offspring. However, these studies had limited cohort sizes (n=24 910) to generalise the results.16 Furthermore, they did not account for potential confounders, including maternal and childbirth related factors (eg, breastfeeding history). By contrast, our large scale nationwide cohort study, encompassing over 3.12 million pregnancies, offers a more sophisticated understanding supported by statistical analyses, thereby highlighting the nuanced association between prenatal opioid exposure and neuropsychiatric outcomes in the child.

Possible mechanisms

In this cohort study, prenatal opioid exposure was not associated with a substantial increase in the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders. The benefits of short term use of prescription opioids in attenuating acute pain without additional risk factors during pregnancy may surpass the potential risk of neuropsychiatric disorders because short term use of opioids during pregnancy seems to have a relatively low risk of neuropsychiatric outcomes. Previous studies showed that untreated pain during pregnancy may lead to a lower quality of life and limited productivity.34 When considering the risk to benefit ratio balance of prescribing opioids during pregnancy, relief of pain is crucial during pregnancy to manage maternal health and life; however, clinicians should consider avoiding opioid use under certain conditions, such as in the first trimester, for long term use, and at high dose use.

The increased risk of psychiatric disorders associated with first trimester opioid exposure suggests potential risk during the early neurodevelopmental phases. The early trimester is characterised by critical stages of neurogenesis, neuronal migration, and differentiation.31 32 Opioids, acting on the central nervous system, might interfere with these processes and disrupt normal brain developmental patterns.35 In addition, the observed dose-response association between maternal opioid dosage and the incidence of neuropsychiatric disorders in the offspring indicates that prolonged and intense exposure might have cumulative heightened effects that are detrimental on fetal brain development. Higher doses and longer durations of opioid use could lead to more significant alterations in the neurochemical environment of the developing fetus, potentially altering neural pathways and synaptic functions.36

Children born via caesarean section display an increased risk of neuropsychiatric disorders.37 The increased risk might be attributed to several associated factors: the underlying maternal conditions necessitating a caesarean section that could influence fetal brain development; the absence of natural microbial exposure from the birth canal, affecting the gut microbiome of infants and potential brain interactions; altered hormonal responses compared with vaginal delivery, which can affect neonatal brain maturation; and differences in the immediate postnatal environment, such as exposure to anaesthetics, that could affect early neural patterns.37 38 Therefore, combining the two adverse effects of caesarean section and maternal opioid use may synergistically increase the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in offspring.38

Children with prenatal opioid exposure display an increased risk of specific neuropsychiatric disorders, suggesting that opioids may interfere with certain developmental processes in the fetal brain. Opioids can cross the placenta and blood–brain barrier and may influence the balance of neurotransmitters, which is crucial for developing and maintaining neural circuits.39 The increased risk of mood disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and intellectual disabilities may result from opioids affecting the serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine pathways, which are primary neurotransmitters for mood regulation, attention, and cognition.39 The elucidated mechanisms presented in this study are speculative and require further validation. However, the significantly higher risk of severe neuropsychiatric disorders than that of common neuropsychiatric disorders implies the potential for opioids to disturb critical periods of neurodevelopment, leading to more critical neurobehavioural outcomes. Therefore, our findings suggest that clinicians should consider these potential risks when prescribing opioids during the first trimester, which is a crucial neurodevelopmental phase.

However, the overall population in our cohort study suggests no considerable association between maternal opioid use and neuropsychiatric disorders in the offspring. However, clinicians and patients should pay attention to opioid use in the first trimester or caesarean section, high dose, or long term intake.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This nationwide longitudinal study used validated diagnostic records and a large generalisable sample size, which minimised the risk of selection and recall biases (table S27). In addition, substantial individual-level healthcare data allowed us to characterise numerous potential confounders, including inpatient and outpatient medication exposure and medical conditions. The use of various study designs, including the full unmatched population based, propensity score matched, child screening, sibling comparison cohorts from the full unmatched, propensity score matched, and child screening cohorts, and multiple subgroup analyses, enhanced the results of our findings. Moreover, because opioids are available only as prescriptions in South Korea, exposure misclassification due to over-the-counter availability was unlikely.

Our study has several limitations. While prescriptions are recorded, they may not always reflect the actual consumption of the medication, leading to potential exposure misclassification. We can suggest an association but not explain the causal association owing to the observational nature of our study. Additionally, even with our sibling controlled analyses, potential confounding by unobserved non-shared familial factors exists.40 The method used to estimate the start of pregnancy, despite being previously validated, may retain the potential misclassification of the exposure window.40 We could not account for other potential risk factors for neuropsychiatric disorders, such as infection, epilepsy, fever, and vaccination. Because NSAIDs are not categorised as prescription drugs, an underestimation regarding their consumption is possible. However, considering the typically cautious approach of pregnant women towards medication intake without prescriptions, we decided to incorporate analyses related to NSAIDs as milder analgesics.1 41 Finally, the cohort was restricted to pregnancies that resulted in live births and excluded terminated pregnancies due to the absence of gestational age data for non-live births.

Conclusion

In this nationwide birth cohort study, opioid use during pregnancy was not associated with a substantial increase in the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in the child. Although a slightly increased risk was observed for neuropsychiatric disorders, given the observational nature of the study, these results should not be considered clinically meaningful. However, through several statistical analyses, we found that prenatal opioid exposure during the first trimester, higher doses, and long term opioid use were associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders in the child. Prenatal opioid exposure modestly increased the risk of severe neuropsychiatric disorders, mood disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and intellectual disability in the child. However, in the context of opioids, excessive exposure, exposure during early pregnancy, and caesarean section may warrant caution owing to their potential associations with some brain developmental disorders in offspring.

What is already known on this topic

Previous studies have shown mixed findings on the association between maternal opioid use and various health outcomes in the offspring, with a limited focus on neuropsychiatric disorders

Large scale, population based birth cohort studies are needed to clarify the potential effect of prenatal opioid exposure on the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in children

What this study adds

Opioid use during pregnancy was not associated with a substantial increase in the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in the offspring, particularly in sibling controlled analyses

An increased risk of neuropsychiatric disorders was observed and limited to high opioid doses, more than one opioid, longer duration of exposure, opioid exposure during early pregnancy, and only to certain specific neuropsychiatric disorders

These results support cautious opioid prescribing during pregnancy, highlighting the importance of further research for more definitive guidelines

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Extra material supplied by authors

Contributors: JK and HJK contributed equally to this work as first authors. JIS and DKY contributed equally. MS and DKY are senior authors. DKY is a principal investigator. HJK is a co-principal investigator. JK, HJK, JIS, and DKY developed the study concept and drafted analyses plan. HJK and DKY collected data. JK, HJK, and DKY conducted analysis and prepared results. JK and HJK wrote the first draft of the paper. JIS, DKY, and MS provided critical review. All authors provided input into interpretation of results and contents of the paper. DKY had full access to all of the data in the study and verified the data. HJK and DKY are responsible for the integrity of the data, accuracy of the data analysis, and decision to submit the manuscript, and act as guarantors. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet the authorship criteria and that no one meeting the criteria has been omitted.

Funding: This research was supported by a grant of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korea government (MSIT; RS-2023-00248157), the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI; HE23C002800), and Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2024 (21153MFDS601). Samuele Cortese, NIHR Research Professor (NIHR303122) is funded by the NIHR for this research project. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, NHS, or the UK Department of Health and Social Care. SC is also supported by NIHR grants NIHR203684, NIHR203035, NIHR130077, NIHR128472, RP-PG-0618-20003, and by grant 101095568-HORIZONHLTH- 2022-DISEASE-07-03 from the European Research Executive Agency. SC has declared reimbursement for travel and accommodation expenses from the Association for Child and Adolescent Central Health in relation to lectures delivered, the Canadian AADHD Alliance Resource, the British Association of Psychopharmacology, and from Medicine and Healthcare Convention for educational activity on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: funding for this research was provided by the National Research Foundation of Korea, the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, and the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety of the Republic of Korea; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. MS has received honoraria/been a consultant for Angelini, AbbVie, Lundbeck, Otsuka, unrelated to this work.

Transparency: The corresponding authors (JIS and DKY), senior author (MS), lead author (JK), and co-principal investigator (HJK) affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: The results of the study will be officially registered and released to National Health Insurance Service of Korea and we plan to disseminate the results of this study to all study participants and wider relevant communities upon request.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Ethical approval

The Korean government anonymised all patient related data, including personal identification numbers, to enhance confidentiality. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyung Hee University (KHUH 2022-06-042) and the NHIS (NHIS-2023-1-168). We conducted this study using de-identified administrative data that were obtained without prior consent.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The study protocol and statistical code are available from DKY (yonkkang@gmail.com). The dataset is available from the National Health Insurance Service of Korea through a data use agreement.

References

- 1. Twigg MJ, Lupattelli A, Nordeng H. Women’s beliefs about medication use during their pregnancy: a UK perspective. Int J Clin Pharm 2016;38:968-76. 10.1007/s11096-016-0322-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wilton J, Abdia Y, Chong M, et al. Prescription opioid treatment for non-cancer pain and initiation of injection drug use: large retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2021;375:e066965. 10.1136/bmj-2021-066965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boutib A, Chergaoui S, Azizi A, et al. Health-related quality of life during three trimesters of pregnancy in Morocco: cross-sectional pilot study. EClinicalMedicine 2023;57:101837. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang X, Wang Y, Tang B, Feng X. Opioid exposure during pregnancy and the risk of congenital malformation: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022;22:401. 10.1186/s12884-022-04733-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bateman BT, Hernandez-Diaz S, Straub L, et al. Association of first trimester prescription opioid use with congenital malformations in the offspring: population based cohort study. BMJ 2021;372:n102. 10.1136/bmj.n102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Esposito DB, Huybrechts KF, Werler MM, et al. Characteristics of prescription opioid analgesics in pregnancy and risk of neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome in newborns. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2228588. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.28588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kanakaris NK, Roberts CS, Giannoudis PV. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain: an update. BMC Med 2011;9:15. 10.1186/1741-7015-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zafeiri A, Raja EA, Mitchell RT, Hay DC, Bhattacharya S, Fowler PA. Maternal over-the-counter analgesics use during pregnancy and adverse perinatal outcomes: cohort study of 151 141 singleton pregnancies. BMJ Open 2022;12:e048092. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zou R, Boer OD, Felix JF, et al. Association of maternal tobacco use during pregnancy with preadolescent brain morphology among offspring. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2224701. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.24701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brannigan R, Tanskanen A, Huttunen MO, Cannon M, Leacy FP, Clarke MC. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring psychiatric disorder: a longitudinal birth cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2022;57:595-600. 10.1007/s00127-021-02094-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Collaborators GBDMD, GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators . Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022;9:137-50. 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nygaard E, Slinning K, Moe V, Fjell A, Walhovd KB. Mental health in youth prenatally exposed to opioids and poly-drugs and raised in permanent foster/adoptive homes: A prospective longitudinal study. Early Hum Dev 2020;140:104910. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2019.104910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sarfi M, Eikemo M, Welle-Strand GK, Muller AE, Lehmann S. Mental health and use of health care services in opioid-exposed school-aged children compared to foster children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2022;31:495-509. 10.1007/s00787-021-01728-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reddy UM, Davis JM, Ren Z, Greene MF, Opioid Use in Pregnancy, Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, and Childhood Outcomes Workshop Invited Speakers . Opioid use in pregnancy, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and childhood outcomes: executive summary of a Joint Workshop by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Academy of Pediatrics, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the March of Dimes Foundation. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:10-28. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Skovlund E, Handal M, Selmer R, Brandlistuen RE, Skurtveit S. Language competence and communication skills in 3-year-old children after prenatal exposure to analgesic opioids. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2017;26:625-34. 10.1002/pds.4170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wen X, Lawal OD, Belviso N, et al. Association between prenatal opioid exposure and neurodevelopmental outcomes in early childhood: a retrospective cohort study. Drug Saf 2021;44:863-75. 10.1007/s40264-021-01080-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Noh Y, Jeong HE, Choi A, et al. Prenatal and infant exposure to acid-suppressive medications and risk of allergic diseases in children. JAMA Pediatr 2023;177:267-77. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.5193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Park S, Kim MS, Yon DK, et al. GBD 2019 South Korea BoD Collaborators . Population health outcomes in South Korea 1990-2019, and projections up to 2040: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2023;8:e639-50. 10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00122-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee SW, Shin YH, Shin JI, et al. Fracture incidence in children after developing atopic dermatitis: A Korean nationwide birth cohort study. Allergy 2023;78:871-5. 10.1111/all.15577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee SW, Lee J, Moon SY, et al. Physical activity and the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, severe COVID-19 illness and COVID-19 related mortality in South Korea: a nationwide cohort study. Br J Sports Med 2022;56:901-12. 10.1136/bjsports-2021-104203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Noh Y, Lee H, Choi A, et al. First-trimester exposure to benzodiazepines and risk of congenital malformations in offspring: A population-based cohort study in South Korea. PLoS Med 2022;19:e1003945. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davis CS, Lieberman AJ. Laws limiting prescribing and dispensing of opioids in the United States, 1989-2019. Addiction 2021;116:1817-27. 10.1111/add.15359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Desai RJ, Huybrechts KF, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Exposure to prescription opioid analgesics in utero and risk of neonatal abstinence syndrome: population based cohort study. BMJ 2015;350:h2102. 10.1136/bmj.h2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee SW, Yang JM, Moon SY, et al. Association between mental illness and COVID-19 susceptibility and clinical outcomes in South Korea: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:1025-31. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30421-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yoo IK, Marshall DC, Cho JY, et al. N-Nitrosodimethylamine-contaminated ranitidine and risk of cancer in South Korea: a nationwide cohort study. Life Cycle 2021;1:e1. 10.54724/lc.2021.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Snowden JM, Lyndon A, Kan P, El Ayadi A, Main E, Carmichael SL. Severe Maternal Morbidity: A Comparison of Definitions and Data Sources. Am J Epidemiol 2021;190:1890-7. 10.1093/aje/kwab077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Woo A, Lee SW, Koh HY, Kim MA, Han MY, Yon DK. Incidence of cancer after asthma development: 2 independent population-based cohort studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021;147:135-43. 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee JS, Shin JI, Kim S, et al. Breastfeeding and impact on childhood hospital admissions: a nationwide birth cohort in South Korea. Nat Commun 2023;14:5819. 10.1038/s41467-023-41516-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Frisell T. Invited commentary: sibling-comparison designs, are they worth the effort? Am J Epidemiol 2021;190:738-41. 10.1093/aje/kwaa183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Timpka S, Stuart JJ, Tanz LJ, Rimm EB, Franks PW, Rich-Edwards JW. Lifestyle in progression from hypertensive disorders of pregnancy to chronic hypertension in Nurses’ Health Study II: observational cohort study. BMJ 2017;358:j3024. 10.1136/bmj.j3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Antoun S, Ellul P, Peyre H, et al. Fever during pregnancy as a risk factor for neurodevelopmental disorders: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Autism 2021;12:60. 10.1186/s13229-021-00464-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Selemon LD, Zecevic N. Schizophrenia: a tale of two critical periods for prefrontal cortical development. Transl Psychiatry 2015;5:e623. 10.1038/tp.2015.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nygaard E, Moe V, Slinning K, Walhovd KB. Longitudinal cognitive development of children born to mothers with opioid and polysubstance use. Pediatr Res 2015;78:330-5. 10.1038/pr.2015.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Persson M, Winkvist A, Dahlgren L, Mogren I. “Struggling with daily life and enduring pain”: a qualitative study of the experiences of pregnant women living with pelvic girdle pain. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:111. 10.1186/1471-2393-13-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peterson BS, Rosen T, Dingman S, et al. Associations of maternal prenatal drug abuse with measures of newborn brain structure, tissue organization, and metabolite concentrations. JAMA Pediatr 2020;174:831-42. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Trønnes JN, Lupattelli A, Handal M, Skurtveit S, Ystrom E, Nordeng H. Association of timing and duration of prenatal analgesic opioid exposure with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2124324. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang T, Sidorchuk A, Sevilla-Cermeño L, et al. Association of cesarean delivery with risk of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders in the offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1910236. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jašarević E, Hill EM, Kane PJ, et al. The composition of human vaginal microbiota transferred at birth affects offspring health in a mouse model. Nat Commun 2021;12:6289. 10.1038/s41467-021-26634-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lind JN, Interrante JD, Ailes EC, et al. Maternal use of opioids during pregnancy and congenital malformations: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20164131. 10.1542/peds.2016-4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Choi A, Noh Y, Jeong HE, et al. Association between proton pump inhibitor use during early pregnancy and risk of congenital malformations. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e2250366. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.50366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Choi EY, Jeong HE, Noh Y, et al. Neonatal and maternal adverse outcomes and exposure to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs during early pregnancy in South Korea: A nationwide cohort study. PLoS Med 2023;20:e1004183. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Extra material supplied by authors

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The study protocol and statistical code are available from DKY (yonkkang@gmail.com). The dataset is available from the National Health Insurance Service of Korea through a data use agreement.