Abstract

An ideal vaccine not only attenuates virus growth and disease in infected individuals but also reduces the spread of infections in the population, thereby generating herd immunity. While this strategy has proven successful by generating humoral immunity to measles, yellow fever and polio, many respiratory viruses evolve to evade pre-existing antibodies 1. One approach for improving the breadth of antiviral immunity against escape variants is through the generation of memory T cells in the respiratory tract, which are positioned to rapidly respond to respiratory virus infections 2–6. However, it is unknown whether memory T cells alone can effectively surveil the respiratory tract to an extent that they eliminate or greatly reduce viral transmission following exposure of an individual to infection. Here, we use a mouse model of natural parainfluenza virus transmission to quantify the extent to which memory CD8 T cells resident in the respiratory tract can provide herd immunity by reducing both the susceptibility of acquiring infection and the extent of transmission, even in the absence of virus-specific antibodies. We demonstrate that protection by resident memory CD8 T cells requires the antiviral cytokine IFN-γ and leads to altered transcriptional programming of epithelial cells within the respiratory tract. These results suggest that tissue-resident CD8 T cells in the respiratory tract can play important roles in both protecting the host against viral disease and in limiting viral spread throughout the population.

Current vaccines against respiratory viruses such as influenza and SARS-CoV-2 typically focus on the generation of antibody responses to viral proteins. However, as is well known from these and other viruses, viral evolution can give rise to variants that escape pre-existing antibodies, and this results in continued circulation in the population by infecting both naïve and previously immune hosts 7,8. T cell-based vaccines have been proposed to counter the problem of viral immune-escape 9–11. In contrast to antibody epitopes, viral epitopes recognized by memory T cells are often conserved across respiratory virus strains and show limited historical evidence of acquiring escape mutations due to T cell-mediated immune pressure 12–14. Animal models and human studies have suggested that memory T cells can protect against pathology following infection with respiratory viruses 15,16. In particular, tissue-resident memory CD8 T cells (TRM) localized in the respiratory tract are critical for optimal T cell-mediated protection against respiratory viruses due to their positioning at the site of viral entry and replication 17. Following intranasal infection or vaccination, TRM are established throughout the respiratory tract, including in the nasal cavity, trachea, airways, and lung parenchyma 18,19. In addition to limiting viral replication and immunopathology, TRM can prevent the spread of an established infection from the upper respiratory tract to the lung, averting severe disease that can result from viral pneumonia 19. However, while the phenotype, developmental programs, and protective capacities of respiratory tract TRM have been delineated over the last decade, their ability to protect against natural virus infection, i.e. a virus spread by transmission from an infected host, remains unknown largely due to limitations in our current model systems, particularly for respiratory infections. These limitations include: (i) laboratory infections are typically performed by direct inoculation with high doses of virus, which does not mimic natural transmission that is initiated by a small number of virions through direct contact, droplets, or aerosols; (ii) the lack of a model system that combines detailed immunological measurements (e.g. mice) and robust transmission in a laboratory setting (e.g. influenza in ferrets and guinea pigs) 20; and (iii) infection status and viral load measurements typically require destructive sampling which precludes longitudinal measurements of viral load over time. We overcome these limitations using well-characterized Sendai virus infections of laboratory mice. Sendai virus is a natural mouse parainfluenza virus which transmits through both aerosols and direct contact in a laboratory setting 21. Incorporation of a gene for Luciferase in the virus allows longitudinal measurements of both infection status and viral load. We show that intranasal immunization with vectors containing the immunodominant Sendai virus CD8 T cell epitope results in the robust generation of a durable Sendai-specific respiratory tract TRM population which dramatically reduces viral transmission, both by limiting the window of transmission from an infected host as well as by reducing the susceptibility of mice to acquiring infection following exposure. These findings suggest that in contrast with the conventional view, CD8 TRM may not only attenuate virus replication and disease but could also play an important role in generating herd immunity and reducing the spread of respiratory viruses in populations.

CD8 TRM limit the window of transmission

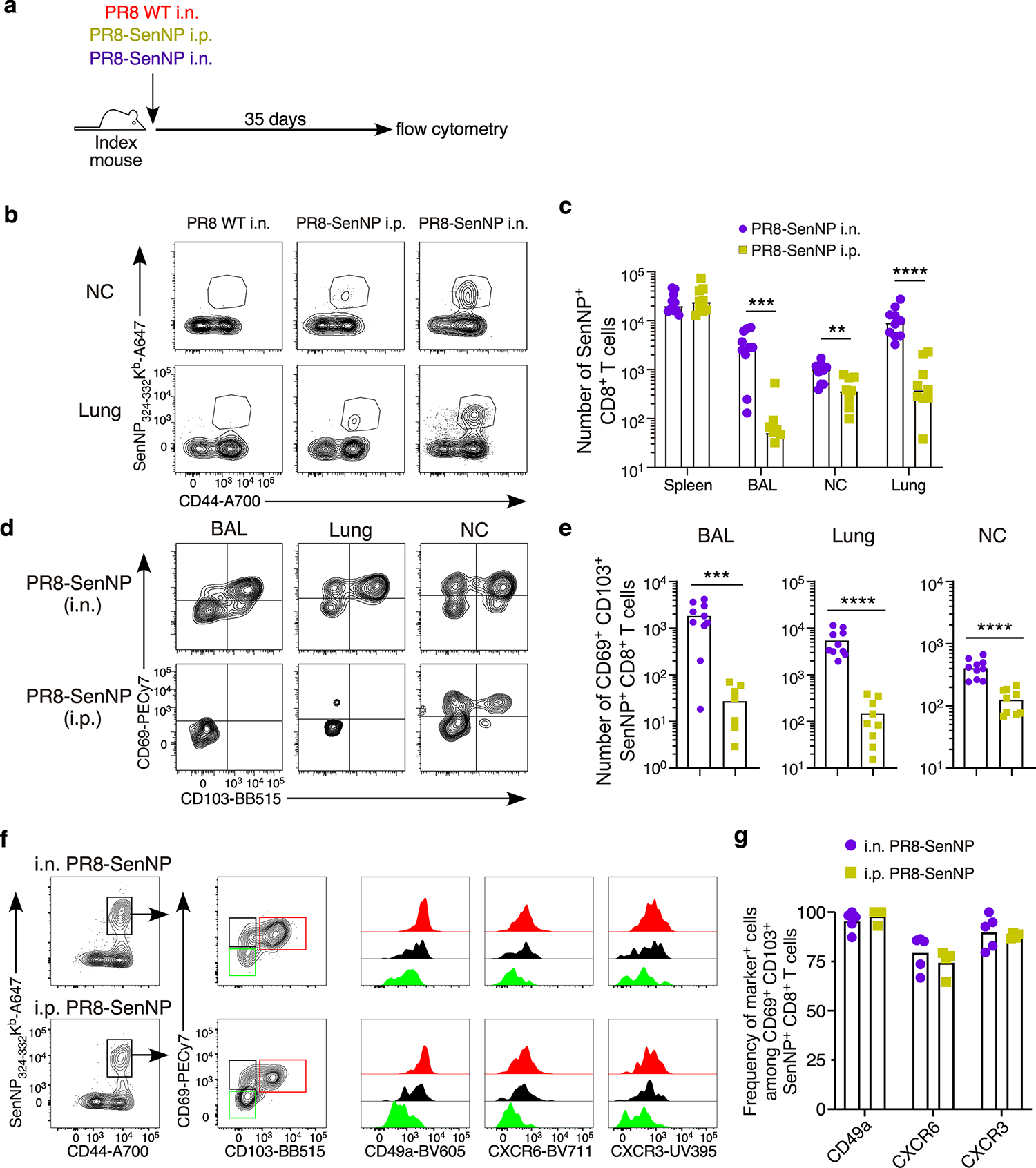

To study the effect of cellular immunity on transmission, we used a genetically modified influenza A virus encoding the immunodominant H-2Kd CD8 T cell epitope (FAPGNYPAL) from Sendai virus nucleoprotein (PR8-SenNP) (Extended data Fig. 1a). By immunizing mice intranasally (i.n.), we induced both Sendai-specific effector memory T cells (TEM) in the circulation and TRM in the respiratory tract without inducing Sendai-specific memory CD4 T cells or Sendai-specific antibodies. When mice were immunized intraperitoneally (i.p), similar numbers of Sendai-specific TEM were generated in the spleen but significantly fewer Sendai-specific CD8 TRM in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), lung and nasal cavity (NC) were observed, as defined by their expression of CD69 and CD103 and the absence of intravital staining (Extended data Fig. 1b–e). Additional TRM-associated markers such as CD49a, CXCR6, and CXCR3 were expressed at similar frequencies on Sendai-specific nasal cavity CD8 TRM established by i.p. on i.n. immunization (Extended data Fig. 1f and 1g).

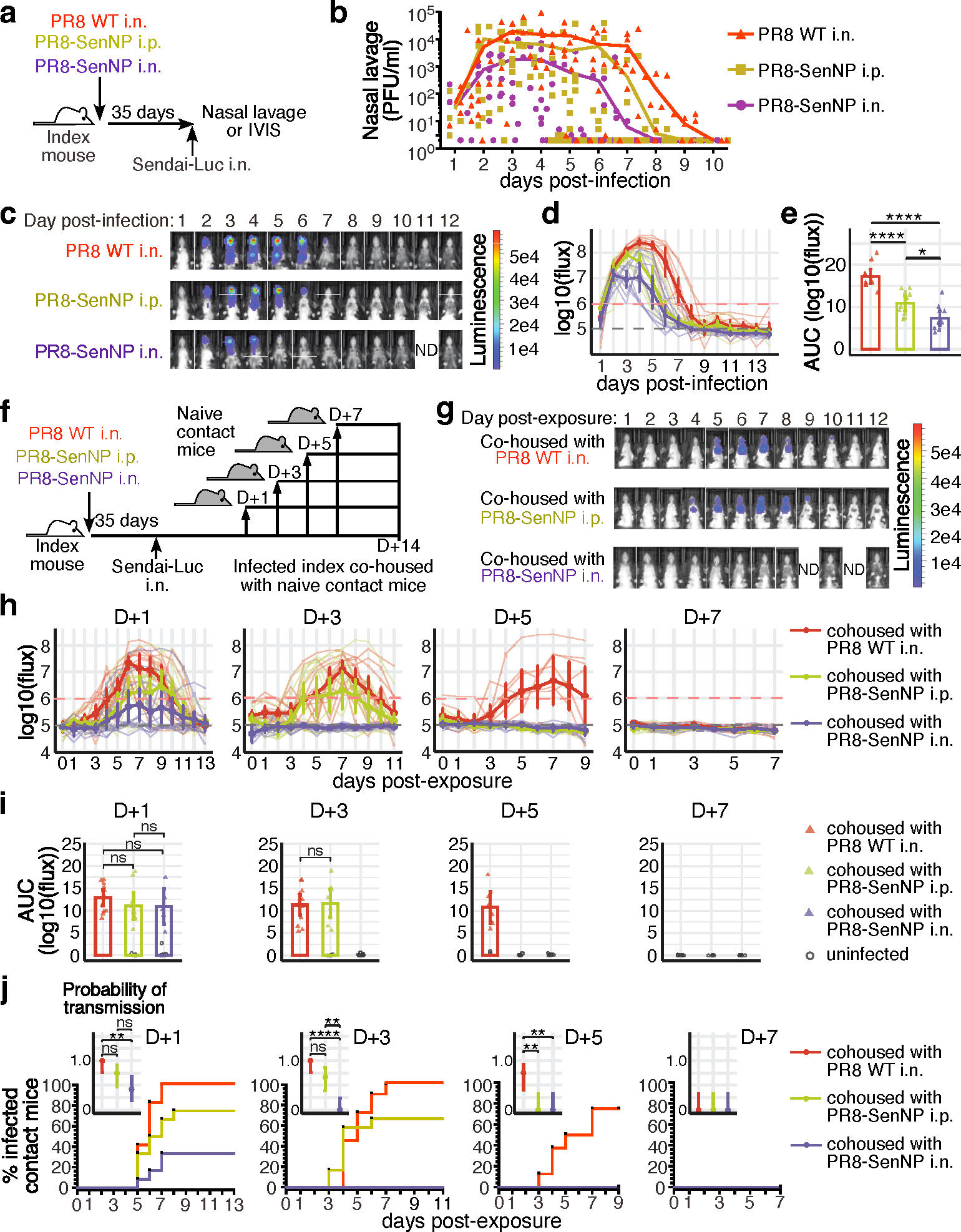

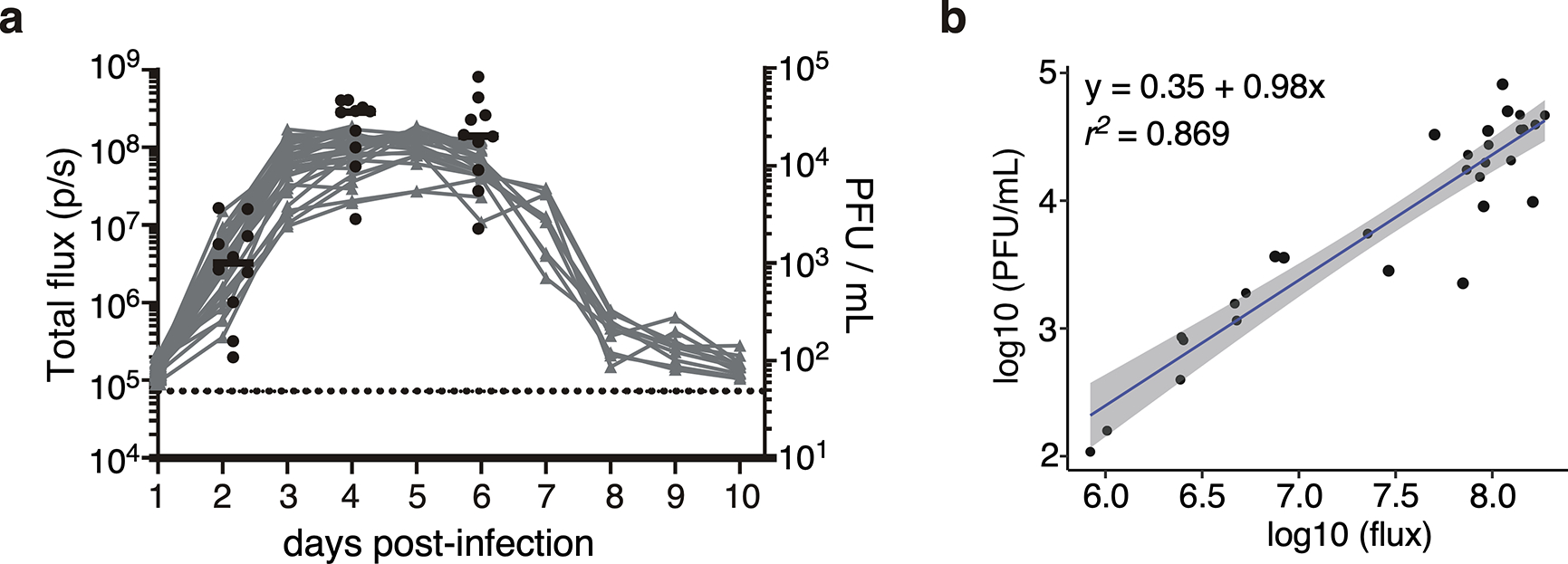

Using the model system described above, we determined how immunization 35 days prior to challenge with Sendai-Luc virus affected viral load as well as transmission (Fig. 1a). To control for potential activation of innate immune cells and any effects of localized inflammation in the respiratory tract following i.n. infection, an additional cohort was primed i.n. with wild-type PR8 virus lacking the SenNP epitope (PR8 WT). Directly challenging mice with a luciferase-encoding Sendai virus (Sendai-Luc) and using bioluminescence as a surrogate for viral replication as previously described 22, we collected longitudinal data on the dynamics of viral replication in mice with Sendai-specific TRM and TEM (PR8-SenNP i.n.), circulating Sendai-specific TEM only (PR8-SenNP i.p.), or no Sendai-specific memory CD8 T cells (WT PR8). As bioluminescence correlated strongly with viral titers, we use it as a surrogate for viral titer throughout the manuscript (Extended data Fig. 2a and 2b). As seen in Fig. 1b, mice immunized with PR8-SenNP exhibited the greatest reduction in both viral load in nasal lavage samples and duration of infection following direct infection with Sendai virus. Intraperitoneal immunization resulted in a more modest reduction in nasal lavage viral load and duration of infection. Similar results were observed with bioluminescence imaging, where mice immunized with PR8-SenNP i.n. showed significantly lower total viral burden (as measured by area under the curve (AUC)) compared with mice immunized with PR8-SenNP i.p. or WT PR8 i.n. (Fig. 1c–e). These results confirm what previous studies have shown at singular time points using viral titers 16,23,24.

Fig. 1. Respiratory tract CD8 TRM can limit transmission of respiratory viruses.

(a) Schematic of experiment to assess Sendai viral titers in the nasal cavity of immunized mice and investigate immunization route on protection from direct infection. (b) Sendai virus titers in the nasal cavity of immunized mice (n=10 for PR8 WT n=10 for PR8-SenNP i.p., n=9 for PR8-SenNP i.n.). c) Representative in vivo imaging (IVIS) images of immunized mice following direct infection with Sendai-Luc. (d) Bioluminescence curves over the course of infection (n=10 per group). (e) Area under curve (AUC) of bioluminescence signal over the course of infection (n=10 for each experimental group). (f) Schematic of experiment to investigate transmission from immunized index mice to naïve contact mice at indicated time points. (g) Example images of contact mice where index mice were added 3 days post infection. (h) Bioluminescence curves of contact mice following co-housing on day 1 (n=12 per group), day 3 (n=12 per group), day 5 (n=8 per group), and day 7 (n=8 per group) post infection of index mice. (i) AUC of bioluminescence of contact mice that become infected following co-housing with an infected index mouse. Grey circles represent uninfected mice. (j) Percent infected contact mice following co-housing with an infected index mouse and the probability of transmission (inset). Dots represent proportion of contact mice that become infected and error bars represent 95% binomial confidence intervals. All data are representative of 2 combined experiments with similar results. For bioluminescence curves (d, h), solid dark lines represent means, solid pale lines represent individual mice, dashed grey line represents background bioluminescence, and dashed red line represents the limit of infection. Solid lines (b, e, i, j) and error bars (d, e, h, i) represent mean with 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance was determined using a two-sided Mann Whitney test. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001, ns: non-significant.

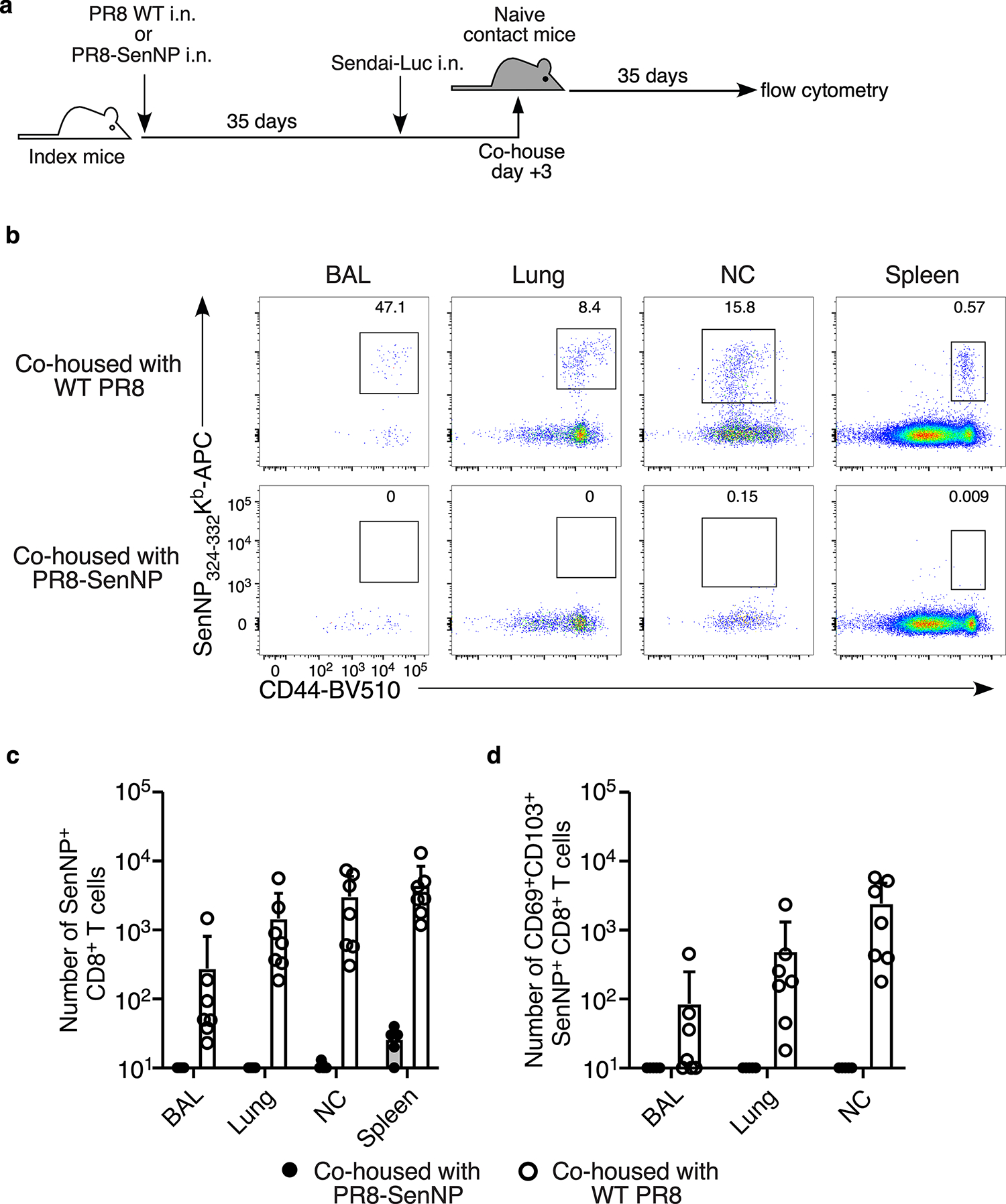

Although immunized mice, and particularly those with pre-existing TRM, showed lower total viral burden, we still detected virus in all mice for at least 5 days following direct infection. Thus, it was unclear whether the presence of TRM could limit or prevent Sendai virus transmission to naïve hosts. To investigate this, mice primed one month prior with PR8-SenNP i.n., i.p., or WT PR8 i.n. (referred to as index mice) were directly infected with Sendai-Luc, cohoused with naïve mice (referred to as contact mice) on days 1, 3, 5, or 7 after challenge, and transmission to naïve contacts was assessed daily by bioluminescence imaging for up to 14 days. The experimental design is shown in Fig. 1f and representative bioluminescence of contact mice is shown in Fig. 1g. As shown in Fig. 1h–j, when index mice were cohoused with naïve contact mice 1 day after direct infection, transmission was observed in all three groups, albeit at different levels. All contact mice became infected when cohoused with an index mouse immunized with WT PR8 i.n., 75% of contact mice became infected when cohoused with an index mouse immunized with PR8-SenNP i.p., and only 33% of contact mice became infected with cohoused with an index mouse immunized with PR8-SenNP i.n. When mice were cohoused on day 3 post-challenge, no transmission was observed in naïve contact mice cohoused with an index mouse immunized with PR8-SenNP i.n., whereas transmission was observed in 66% and 92% of naïve contact mice cohoused with index mice immunized with PR8-SenNP i.p. or WT PR8 i.n., respectively. When cohousing on day 5 post-challenge, there was no transmission to naïve contact mice cohoused with index mice immunized with PR8-SenNP i.p., while transmission was still observed in 75% of naïve contact mice cohoused with index mice immunized with WT PR8 i.n., demonstrating a less immediate role for circulating TEM in shortening the window of transmission. By day 7 post-challenge, no transmission was observed to any naïve contact mice regardless of the cohoused index mouse. Immunization status of the index mice did not affect the dynamics of infection of virus burden in the contact mice that became infected (Fig. 1i). In contrast, i.n. immunization with PR8-SenNP significantly decreased the probability of transmission compared to WT PR8 i.n. immunization when co-housed on day 1 post-challenge and compared to both WT PR8 i.n. and PR8-SenNP i.p. when co-housed on day 3 post-challenge (Fig. 1j). To confirm that a lack of bioluminescence signal in naïve contact mice following cohousing was consistent with a lack of Sendai virus transmission, naïve contact mice cohoused with index mice immunized with PR8-SenNP i.n. on day 3 post-challenge did not develop a Sendai-specific CD8 T cell response in the respiratory tract or spleen (Extended data Fig. 3). Together, these data demonstrate that TRM generated by immunization can significantly reduce both the magnitude of virus transmission and shorten the window of respiratory virus transmission following infection.

IFNγ is required to limit transmission

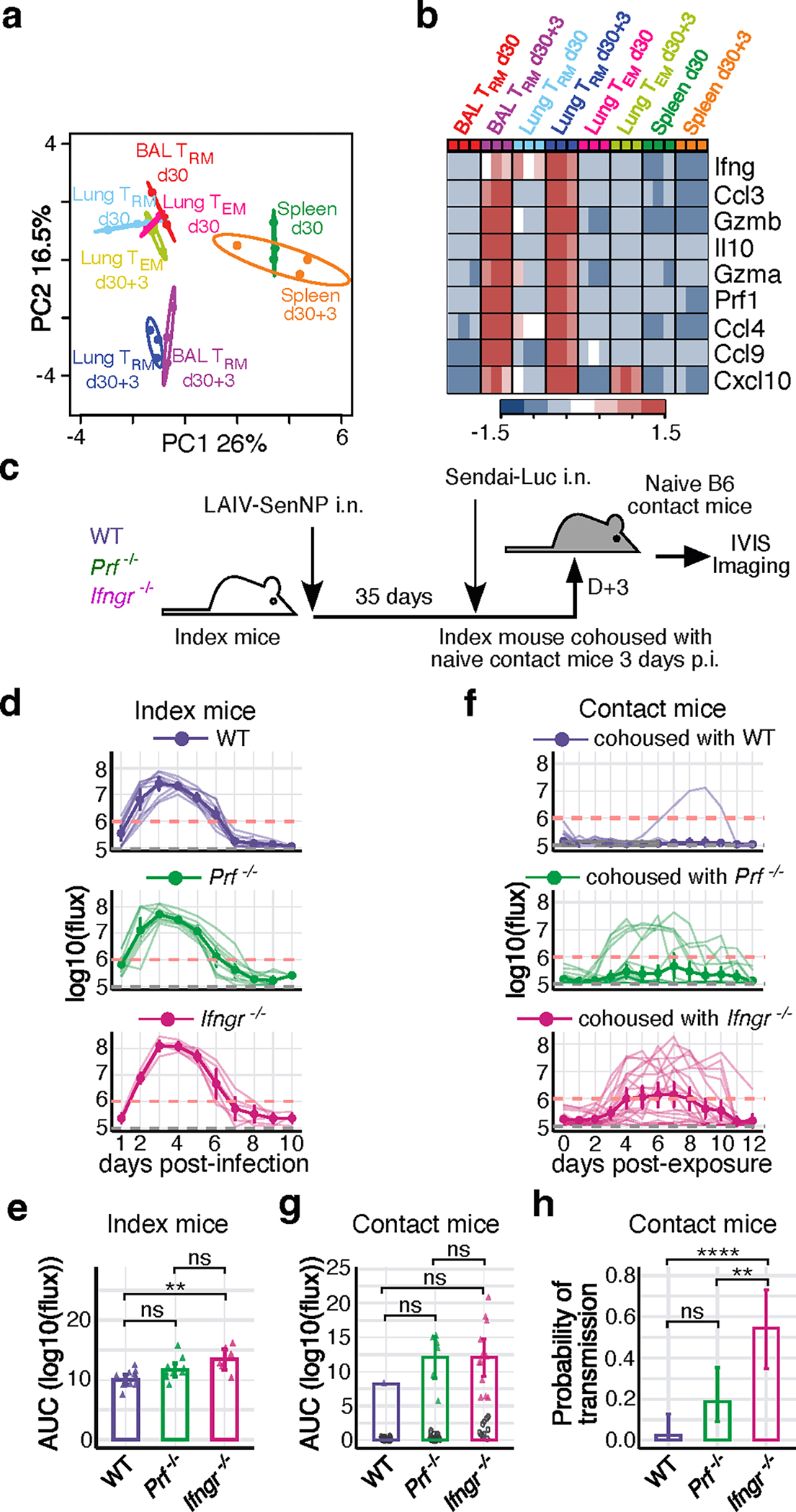

To identify potential mechanisms by which respiratory tract TRM may limit respiratory virus transmission, we performed RNA sequencing of antigen-specific TRM and TEM sorted from the lung and airways prior to and 3 days after direct infection. Principle component analysis of lung and airway TRM after challenge clearly distinguished these cells from resting lung and airway TRM, from TEM in the lung both prior to and 3 days post-challenge, and from antigen-specific TEM in the spleen. Unsurprisingly, there was an upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine genes and genes associated with cytolytic activity, including Ifng, Ccl4, Gzma, Gzmb, Prf1 (Fig. 2a and 2b). As IFNγ and perforin were induced in TRM on day 3 post-challenge and both are key mediators of CD8 T cell effector functions 17,25–27, we investigated their importance for limiting the window of respiratory virus transmission (Fig. 2c). WT, Prf−/−, or Ifngr−/− mice were primed with a live attenuated PR8-SenNP (LAIV-SenNP) to control for potential differences in immunization due to the increased pathogenesis of WT PR8 virus in knockout mice. Similar numbers of Sendai-specific TRM, NK cells, and inflammatory monocytes were observed in the respiratory tract of WT and knockout mice on day 35 post-immunization with LAIV-SenNP (Extended data Fig. 4). It should be noted that total viral burden (AUC) was significantly higher in Ifngr−/− index mice compared to WT index mice, but there was no difference between Ifngr−/− and Prf−/− index mice (Fig. 2d and 2e). Upon cohousing on day 3 post-challenge, robust transmission was observed in naïve contact mice cohoused with Ifngr−/− index mice (12/22, 55%), with limited transmission observed in naïve contact mice cohoused with Prf−/− (6/32, 19%) or WT (1/40, 2.5%) index mice (Fig. 2f–h). Co-housing with Ifngr−/− index mice resulted in significantly higher probability of transmission compared to Prf−/− or WT index mice (Fig. 2h), indicating that IFNγ-IFNγR signaling is a critical mechanism by which TRM limit the window of respiratory virus transmission.

Fig. 2. IFNγ signaling plays an essential role in preventing transmission of respiratory viruses.

(a) PCA plot of sorted virus-specific CD8 TRM and TEM from BAL, lung and spleen of influenza primed mice at resting memory (d30, n=3 per group) and 3 days post challenge (d30+3, n=3 per group), pooled over 3 independent experiments. (b) Heat map of RNA transcript expression for the listed differentially expressed genes. (c) Schematic of experiment to investigate the importance of IFNγR or perforin for limiting transmission to naïve contact mice. (d) Bioluminescence of WT (n=11), Prf−/− (n=10), and Ifngr−/− (n=6) index mice following direct infection with Sendai-Luc. (e) AUC of bioluminescence in index mice. (f) Bioluminescence in B6 contact mice (WT, n=40 contacts; Prf−/−, n=32 contacts; Ifngr−/−, n=22 contacts) following co-housing with infected index mice on day 3 post infection. (g) AUC of bioluminescence in contact mice that become infected following co-housing with an infected index mouse. (h) Probability of transmission to naïve contact mice for each genotype of immunized index mouse, calculated as the proportion of contact mice that became infected. Error bars represent 95% binomial confidence interval. Data are combined from 3 independent experiments (d-h). For bioluminescence curves (d, f), solid dark lines represent means, solid pale lines represent individual mice, dashed grey line represents background bioluminescence, and dashed red line represents the limit of infection. Solid lines (e, g, h) and error bars (d-g) represent mean with 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance was determined using two-sided Mann Whitney test. * p<0.05, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001, ns: non-significant.

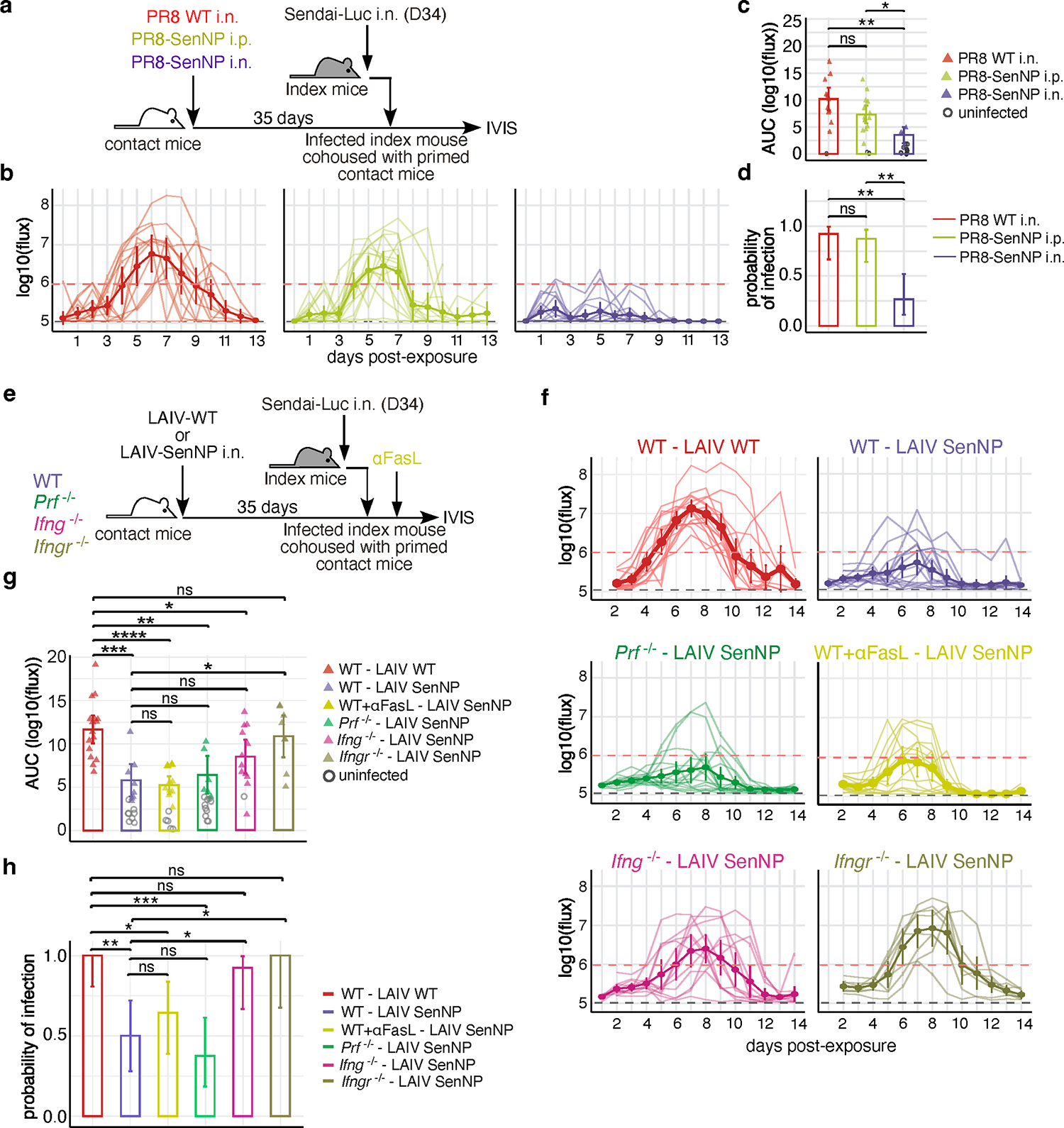

TRM limit susceptibility to infection

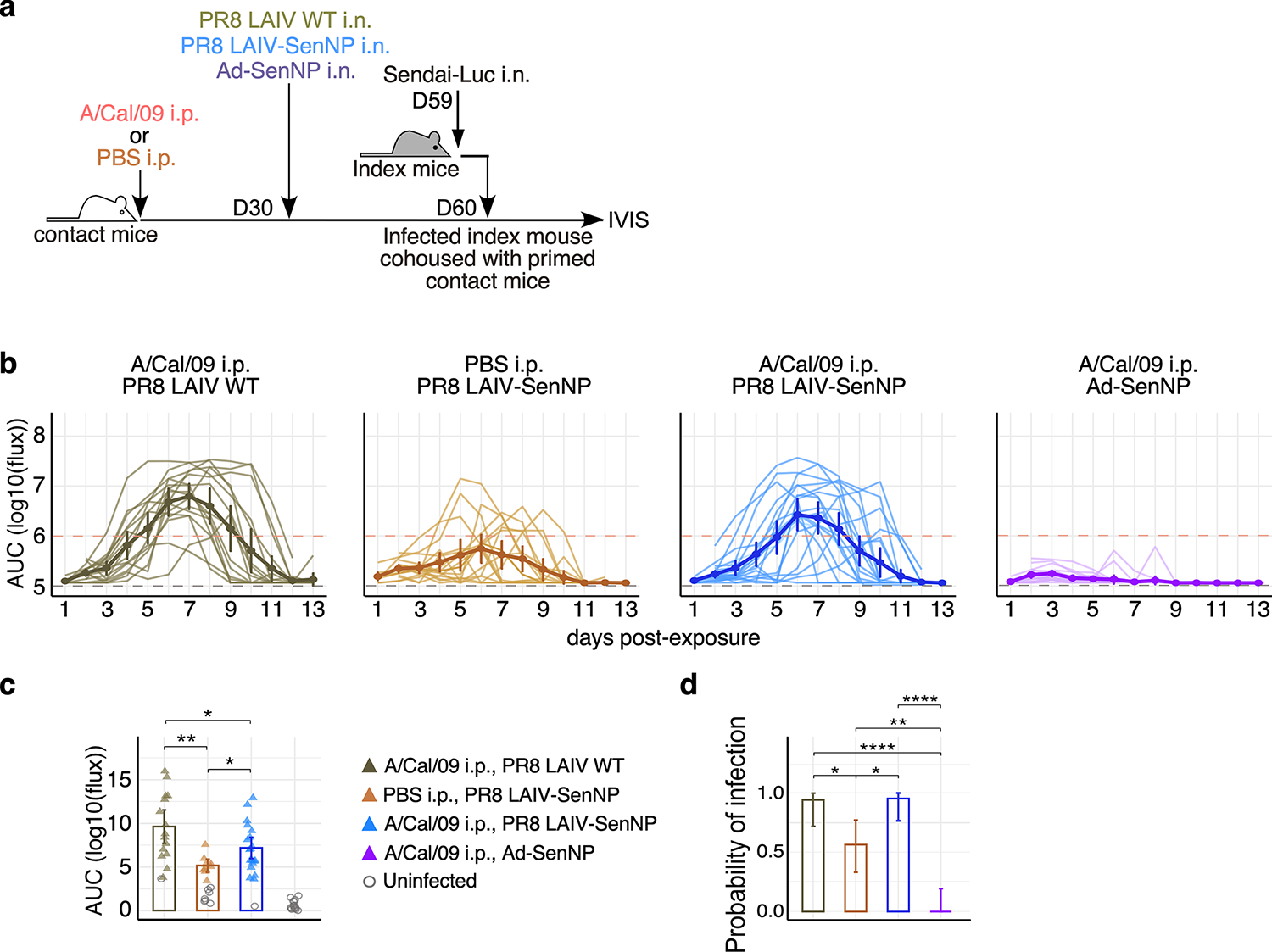

The prior data demonstrate that immunization which results in the generation of CD8 TRM can drastically limit virus transmission to susceptible hosts. We next asked whether pre-existing CD8 TRM could effectively surveil the respiratory tract to affect both the susceptibility of mice to infection as well as attenuate the subsequent virus burden. To address this question, we immunized contact mice with PR8-SenNP i.n., PR8-SenNP i.p., or WT PR8 i.n. (to generate mice with both Sendai-specific TRM and TEM, only circulating Sendai-specific TEM, or no Sendai-specific memory CD8 T cells, respectively) and assessed Sendai-Luc transmission from infected index mice to contact mice 35 days after immunization (Fig. 3a). Mice immunized with PR8-SenNP i.n. showed significant reductions in total viral burden and in the probability of infection, with only 4/15 (27%) of the contact mice getting infected compared with 12/13 (92%) of WT PR8 i.n. or 14/16 (88%) of PR8-SenNP i.p. immunized mice (Fig. 3b–d). These data demonstrate that TRM can reduce the susceptibility of mice to infection and the subsequent virus burden in the mice that do become infected. To assess whether similar antiviral mechanisms were important for TRM to prevent viral propagation following transmission, we immunized WT, Ifng−/−, Ifngr−/−, or Prf−/− mice with LAIV-SenNP and measured transmission after cohousing with an acutely infected index mouse (Fig. 3e). We also tested the importance of Fas-FasL interactions in TRM-mediated protection by administering anti-FasL blocking antibody to WT mice immunized i.n. with LAIV-SenNP. WT, Prf−/−, and WT+anti-FasL treated mice showed similar levels of protection, with breakthrough infections detected in 8/16 (50%) of WT, 6/16 (38%) of Prf−/−, and 8/14 (57%) WT+anti-FasL treated mice (Fig. 3g–i). In contrast, immunized Ifngr−/− mice showed significantly higher viral burdens (AUC, Fig. 3h), and immunized Ifng−/− (12/13, 92%) and Ifngr−/− (8/8, 100%) mice both showed significantly increased probability of infection (Fig. 3i), demonstrating that IFNγ signaling is a key mechanism for TRM-mediated protection against propagation of infection following viral transmission.

Fig. 3. Respiratory tract CD8 TRM protect against viral propagation following transmission through IFNγ.

(a) Schematic of experimental setup where immunized contact mice were cohoused with a Sendai-Luc infected index mouse. (b) Bioluminescence curves of contact mice immunized with PR8 WT i.n. (n=13), PR8 SenNP i.p. (n=16), or PR8-SenNP i.n. (n=15). (c) AUC of bioluminescence in immunized contact mice that become infected following co-housing with an infected index mouse. (d) Probability of infection for immunized contact mice, calculated as the proportion of contact mice that became infected. (e) Schematic of experiment to investigate protection from transmission in immunized WT, Prf−/− Ifng−/−, and Ifngr−/− contact mice and WT mice treated with anti-FasL antibody. (f) Bioluminescence curves of immunized WT (n=16 for LAIV WT and LAIV-SenNP immunization), Prf−/− (n=16), Ifng−/−, (n=13), Ifngr−/− (n=8), and WT+anti-FasL (n=14) contact mice after co-housing with an infected index mouse. (g) AUC of bioluminescence in contact mice that become infected following co-housing with an infected index mouse. (h) Probability of infection for immunized contact mice. Error bars represent 95% binomial confidence intervals (d, h). All data are combined from 2 independent replicates. For bioluminescence curves (b, f), solid dark lines represent means, solid pale lines represent individual mice, dashed grey line represents background bioluminescence, and dashed red line represents the limit of infection. Solid lines (c, d, g, h) and error bars (b, c, f, g) represent mean with 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance was determined using two-sided Mann Whitney test. * p<0.05, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001, ns: non-significant.

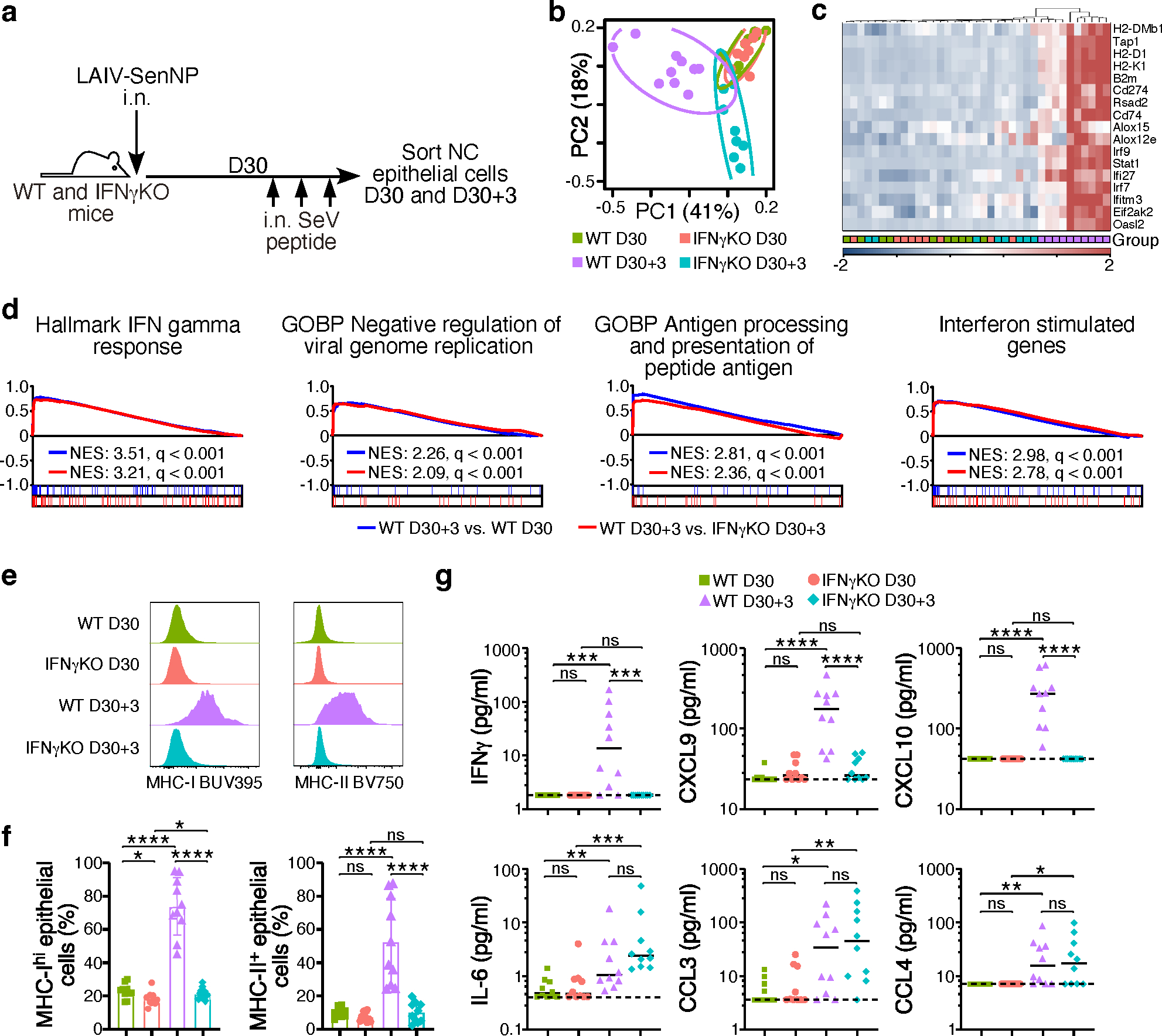

IFNγ alters epithelial cell programming

Previous studies have shown that TRM are capable of rapid sensing and alarm functions, resulting in local inflammation and the recruitment of innate immune cells into the tissue 28. We hypothesized that respiratory tract TRM could enable rapid control of viral replication by increased recruitment of innate immune cells into the tissue. However, regardless of the immunization route or the presence of TRM, there was no difference in the number of NK cells or inflammatory monocytes recruited into the tissues of respiratory tract on day 2 post-transmission (Extended data Fig. 5a–c). We also considered that TRM-mediated effector functions, such as IFNγ, could alter the programming of epithelial cells, the primary target of many respiratory viruses. To discern between inflammatory cytokines and chemokines induced by TRM following antigen recognition versus those induced by innate recognition of an invading pathogen, we used a reductionist approach and directly administered SenNP peptide i.n. to WT and Ifng−/− mice that had been immunized i.n. with LAIV-SenNP one month earlier (Fig. 4a). Epithelial cells were sorted from the nasal cavity prior to (D30) or 3 days after (D30+3) peptide administration for RNA sequencing. Principal component analysis and hierarchical clustering of selected differentially expressed genes showed that nasal cavity epithelial cells from WT D30+3 mice had a distinct transcriptional signature compared to both WT D30 and Ifng−/− D30+3 mice and showed significant upregulation of genes associated with antiviral responses and antigen presentation (Fig 4b, 4c). Pathway analysis showed that processes associated with limiting viral replication, interferon stimulated genes, and antigen processing and presentation were enriched in WT D30+3 mice compared to both WT D30 and Ifng−/− D30+3 mice (Fig 4d). Changes in gene expression associated with antigen presentation were confirmed by flow cytometry, as nasal cavity epithelial cells from WT D30+3 mice showed a significant increase in MHC-I and MCH-II protein expression (Fig. 4e). As expected, cytokine analysis of nasal cavity tissue showed significant increases in IFNγ and IFNγ-associated chemokines in WT D30+3 mice (Fig. 4f). However, levels of IL-6, CCL3, and CCL4 were similar between WT and Ifng−/− D30+3 mice, demonstrating that TRM in Ifng−/− mice could drive localized inflammation following antigen encounter but failed to upregulate genes associated with antiviral immunity in epithelial cells. Together, these data demonstrate that respiratory tract TRM can act on local epithelial cells via IFNγ to rapidly induce an antiviral program.

Fig. 4. IFNγ signaling induces antiviral gene expression and increases antigen presentation in nasal cavity epithelial cells.

(a) Schematic of experiment to evaluate the impact of TRM-derived IFNγ on nasal cavity epithelial cells. (b) PCA plot of sorted nasal cavity epithelial cells from LAIV-SenNP immunized WT and Ifng−/− mice at resting memory (d30) (WT n=10, Ifng−/− n=9) and 3 days post peptide administration (d30+3) (WT n=10, Ifng−/− n=8). (c) Hierarchical clustering of RNA transcript expression for the listed differentially expressed genes. (d) GSEA plots of listed immune pathways. (e) Representative histograms of MHC-I and MHC-II expression on nasal cavity epithelial cells. (f) Frequency of MHC-Ihi and MHC-II+ nasal cavity epithelial cells (n=10 per group). Bars represent mean and standard deviation. (g) Cytokine and chemokine concentrations in the nasal cavity of immunized WT (n=10 per timepoint) and Ifng−/− (n=10 per timepoint) mice at resting memory and 3 days following peptide administration. Bars represent median. The data shown are combined from 2 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using two-sided Mann Whitney test. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001, ns: non-significant.

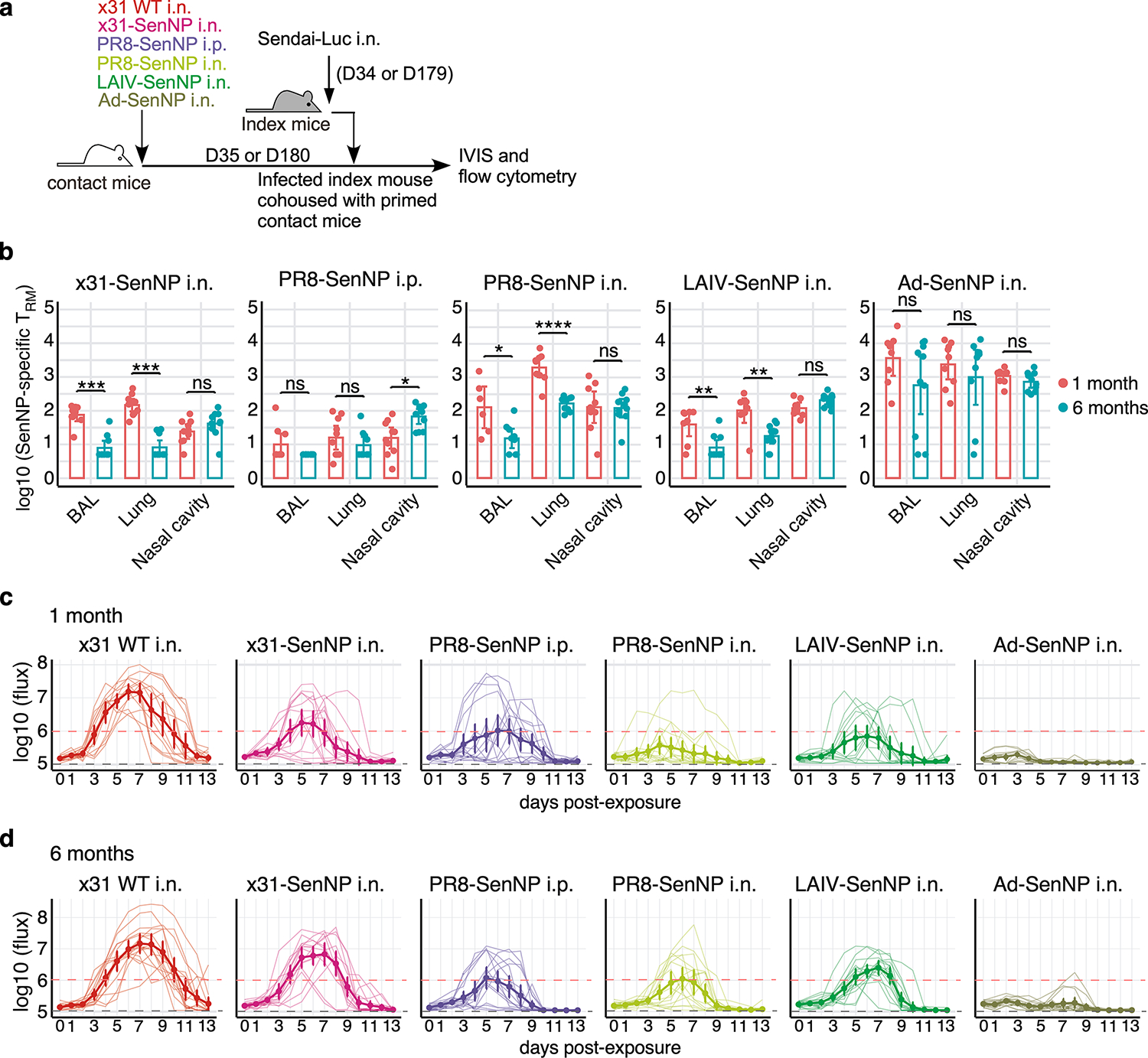

CD8 TRM can provide durable protection

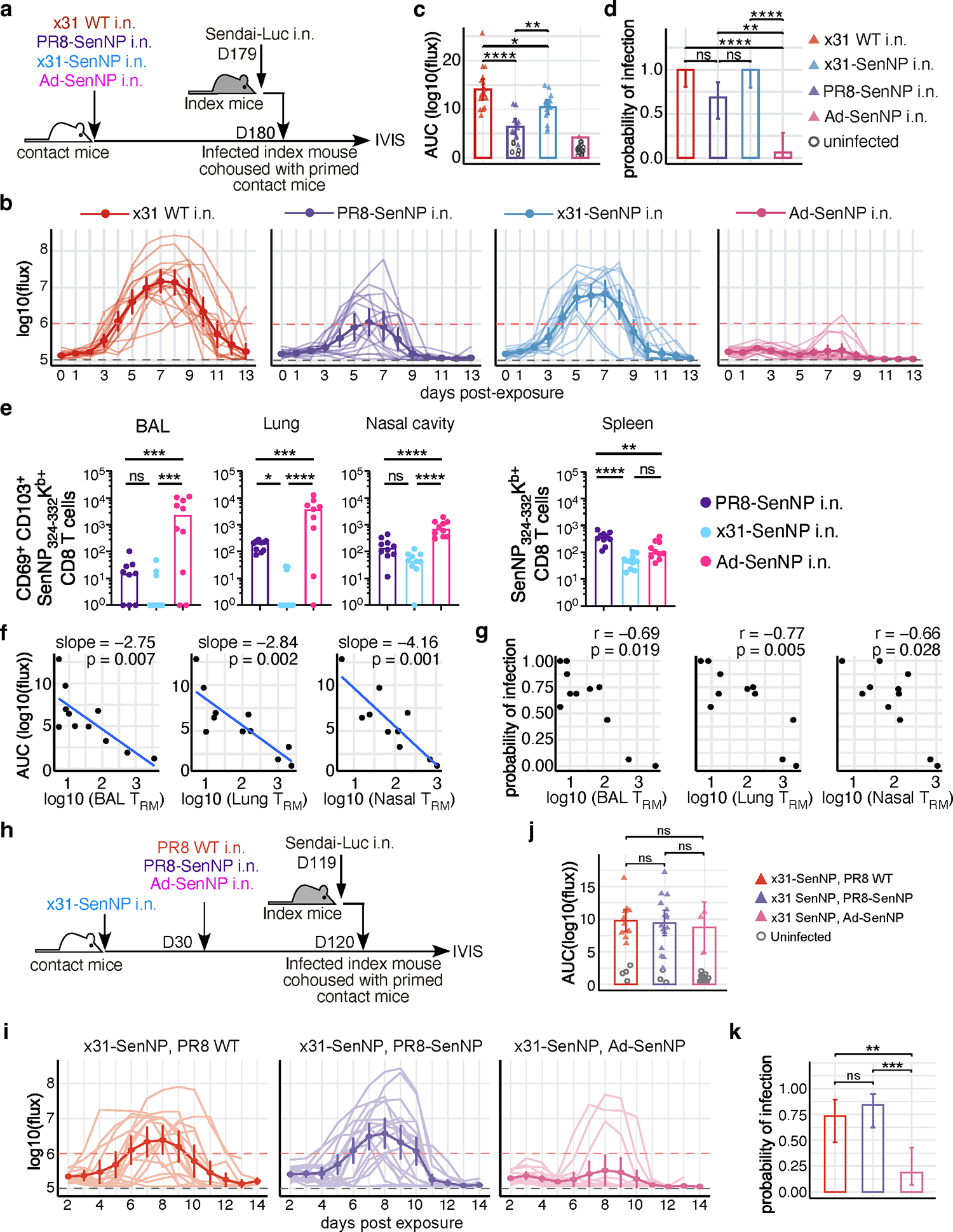

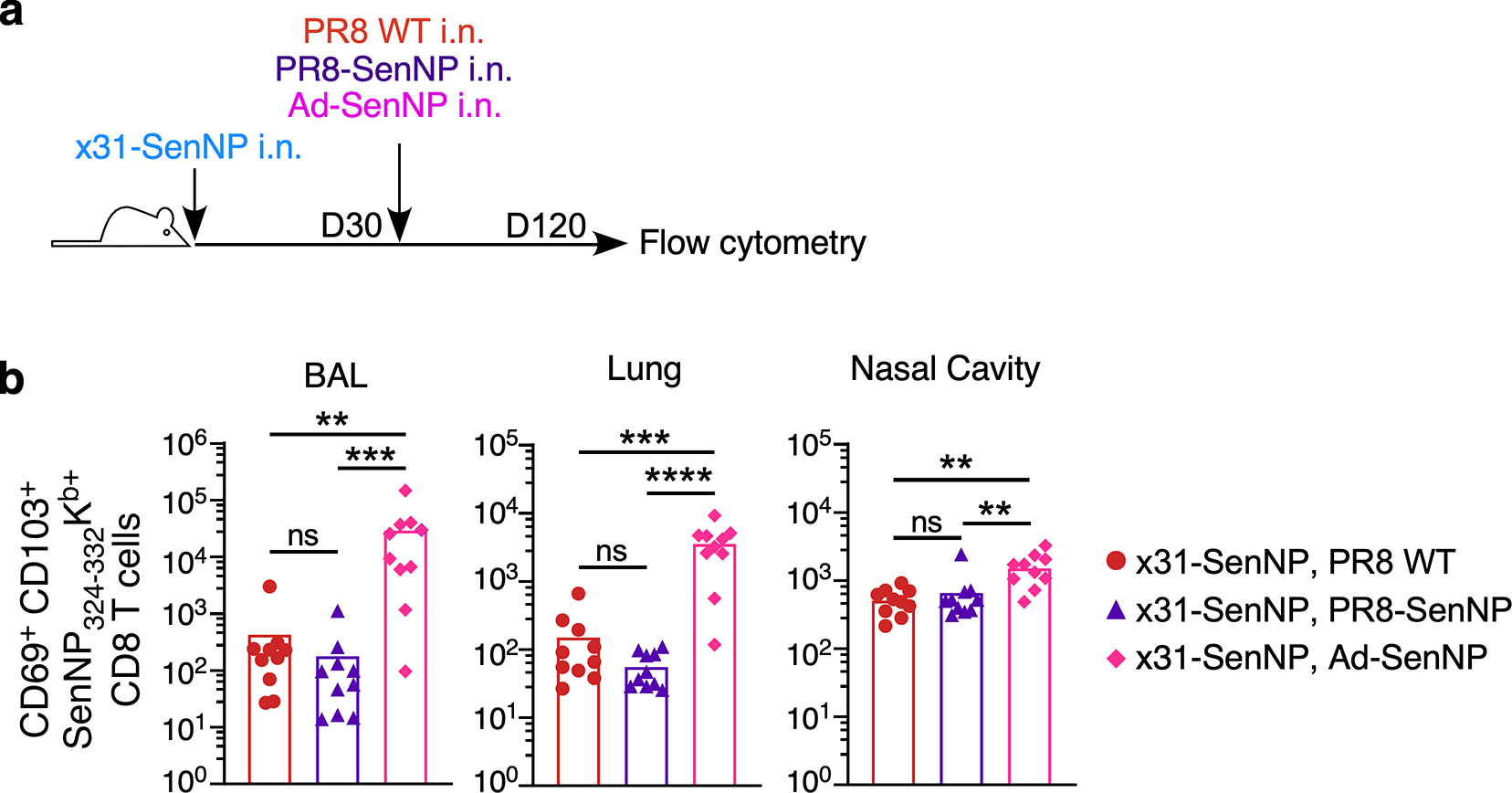

As it has been previously shown that respiratory tract TRM can decline over time 5, we investigated the durability of TRM-mediated protection against infection under several priming scenarios that differ in their ability to maintain TRM 29 (Fig. 5a). Six months post-immunization, contact mice immunized with influenza x31-SenNP i.n. showed no protection against infection compared to control mice immunized with WT x31, although total viral burdens following infection were significantly reduced (Fig. 5b and 5c). Mice immunized with PR8-SenNP i.n. still showed significantly lower total viral burden when infected compared to i.n. immunization with WT x31 or x31-SenNP, but there was no longer any difference in the protection from acquiring infection, in contrast to PR8-SenNP i.n. immunized mice one-month post-immunization (Fig. 3b–d). In contrast, i.n. immunization with a replication-deficient adenovirus vector encoding the Sendai virus nucleoprotein (Ad-SenNP) showed significant protection from infection and less total viral burden compared to all other groups at 6 months (Fig. 5b–d). The increased protection against infection in Ad-SenNP immunized mice corresponded to increased numbers CD69+CD103+ Sendai-specific TRM in the lung, BAL, and nasal cavity, despite lower numbers of Sendai-specific TEM in the spleen (Fig. 5e).

Fig. 5. The number of respiratory tract CD8 TRM is strongly linked to protection from transmission.

(a) Schematic of experiment to investigate the durability of TRM-mediated protection and ability to limit viral transmission. (b) Bioluminescence curves of contact mice immunized with x31 WT (n=16), PR8-SenNP (n=16), x31-SenNP (n=15), and Ad-SenNP (n=16) after co-housing with an infected index mouse. (c) AUC of bioluminescence in contact mice that become infected following co-housing with an infected index mouse. (d) Probability of infection for immunized contact mice, calculated as proportion of contact mice that become infected. (e) Number of CD69+CD103+ Sendai NP324–332/Kb+ CD8 TRM in the BAL (n=9 for PR8-SenNP, n=10 for x31-SenNP and Ad-SenNP), lung (n=9 for Ad-SenNP, n=10 for PR8-SenNP and x31-SenNP), and nasal cavity (n=10 per group), and Sendai NP324–332/Kb+ CD8 TEM in the spleen (n=10 per group), on D180 post-immunization. (f) Correlation between AUC of bioluminescence and the number of CD69+CD103+ Sendai NP324–332/Kb+ TRM in the BAL, lung, and nasal cavity. (g) Correlation between the probability of infection and number of CD69+CD103+ Sendai NP324–332/Kb+ TRM in the BAL, lung, and nasal cavity. (h) Schematic of experiment to investigate the impact of multiple immunizations on the durability of TRM-mediated protection against Sendai virus transmission. (i) Bioluminescence curves of immunized contact mice after co-housing with an infected index mouse (n=15 for PR8 WT boosted contacts, n=19 for PR8-SenNP boosted contacts, and n=16 for Ad-SenNP boosted contacts). (j) AUC of bioluminescence in primed and boosted contact mice that become infected following co-housing with an infected index mouse. (k) Probability of infection for immunized contact mice. Error bars represent 95% binomial proportion confidence intervals (d, k). All data are combined from 2 independent experiments. For bioluminescence curves (b, i), solid dark lines represent means, solid pale lines represent individual mice, dashed grey line represents background bioluminescence, and dashed red line represents the limit of infection. Solid lines (c, d, e, j, k) and error bars (b, c, i, j) represent mean with 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance was determined using two-sided Mann Whitney test * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001, ns: non-significant.

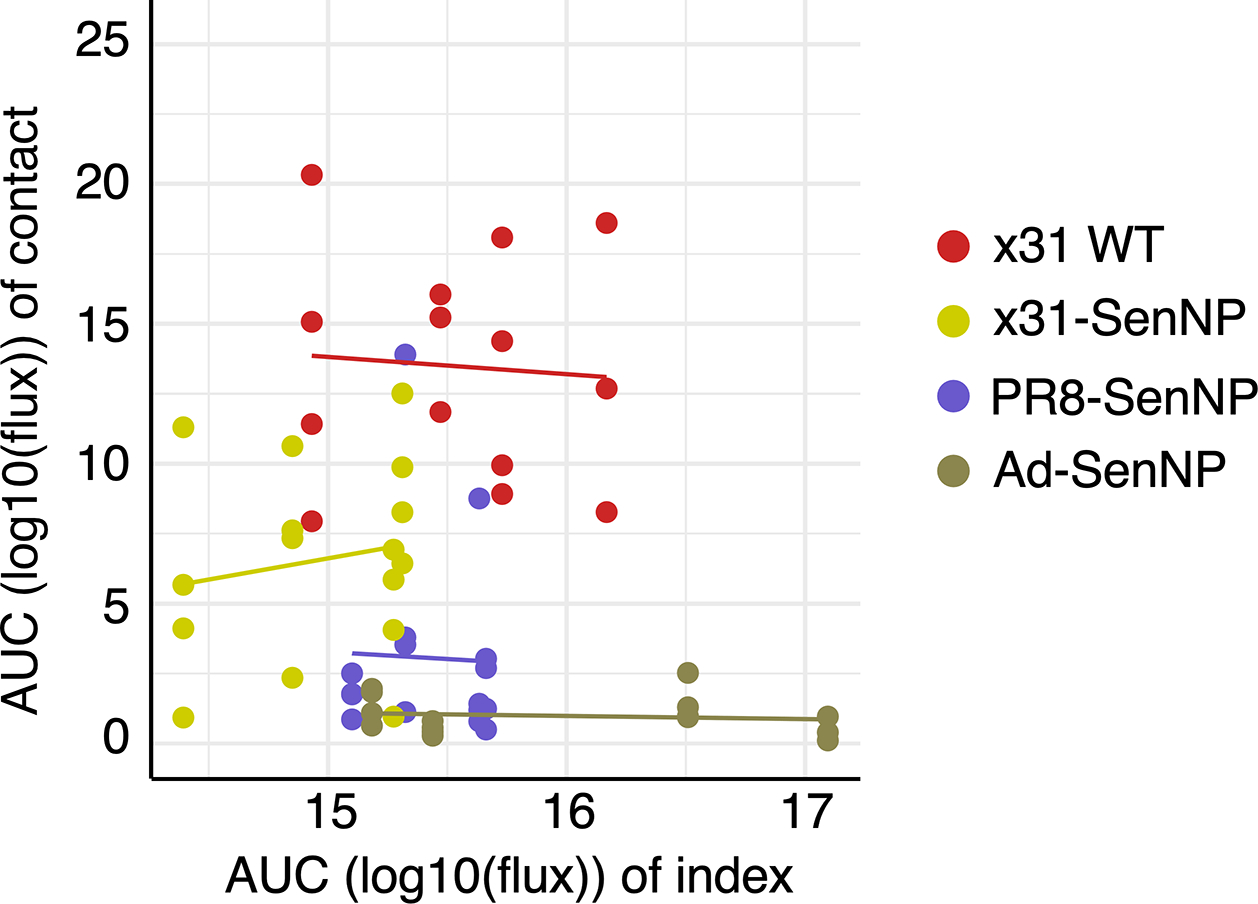

To better quantify the impact of TRM on infection, we compiled data from different immunization regimens and different times post-immunization to determine the correlation between the number of TRM in different areas of respiratory tract, total viral burden (AUC), and the probability of infection (Extended data Fig. 6a–d). There was a significant negative correlation between total viral burden and the number of TRM in the BAL, lung, and nasal cavity, with the strongest correlation in the nasal cavity (Fig 5f). Similarly, there was a significant negative correlation between the number of TRM in the BAL, lung, and nasal cavity and the probability of infection, with the strongest correlation in this case in the lung (Fig. 5g). However, there was no correlation between the total viral burden of the directly-infected index mice with the total viral burden of the contact mice regardless of immunization status (Extended data Fig. 7).

For many pathogens, multiple vaccine doses are utilized in a “prime-boost” immunization strategy to achieve maximal immune responses. However, pre-existing immunity may limit the ability of vaccines to generate robust T cell responses by rapidly clearing vaccine antigens. To investigate whether pre-existing immunity limited TRM-mediated protection against infection, mice were first immunized with influenza A/Cal/09 (H1N1) or mock-immunized prior to i.n. LAIV-SenNP (also H1N1) or Ad-SenNP immunization (Extended data Fig. 8a). Mice with pre-existing H1N1 immunity were not protected against Sendai virus infection after LAIV-SenNP immunization but did show decreased viral burden following infection compared to mice immunized with WT LAIV. In contrast, Ad-SenNP immunization of A/Cal/09 immune mice resulted in significant protection from infection (Extended data Fig. 8b–d). To evaluate whether a heterologous prime-boost regimen could enhance the longevity of CD8 TRM in the respiratory tract and improve the durability of protection against infection, mice were primed with x31-SenNP followed by boosting with PR8-SenNP or Ad-SenNP (Fig. 5h). Three months after the second immunization, contact mice boosted with PR8-SenNP did not show increased protection against infection compared to mice that received priming only (Fig. 5i–k). However, secondary immunization with Ad-SenNP showed significantly decreased probability of infection, (Fig. 5i–k). These results aligned with the increased number of CD69+CD103+ Sendai-specific CD8 TRM in the respiratory tract of Ad-SenNP boosted mice compared to PR8-SenNP boosted mice (Extended data Fig. 9). Together, these data show that the number of virus-specific TRM in the respiratory tract dictate the ability of cell-mediated immunity to protect against respiratory virus infection.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate that pre-existing CD8 TRM in the respiratory tract can drastically limit viral transmission. It has been well documented that CD8 TRM can reduce viral loads and limit immunopathology in models of direct infection 16,30–32, but for the first time, we show that CD8 TRM are sufficient to significantly reduce both the susceptibility of immunized hosts from becoming infected and their ability to transmit virus if they do become infected. It is important to note that protective immunity provided by respiratory tract CD8 TRM is likely not sterilizing, as these cells must first encounter their specific antigen presented by a virus-infected cell to perform their effector functions. Numerous studies have made the case for development of T cell vaccines against respiratory pathogens, with an emphasis on the potential for mucosal resident memory T cells to provide rapid and robust immunity due to their localization at the site of viral entry 10,33,34. Our data demonstrate that several different immunization regimens, including live attenuated and replication-deficient vectors, can generate mucosal TRM in sufficient numbers to effectively surveil the respiratory tract to limit the susceptibility of becoming infected as well as transmission. Notably, these findings were observed in a stringent transmission model of direct, continuous contact, whereas most opportunities for transmission are brief interactions. Moreover, Sendai virus infection does not visibly alter the activity of infected mice, and thus does not affect their interaction with cage mates. While antibody-mediated neutralization capable of preventing infection is an ideal outcome of vaccination against respiratory viruses, engaging the cellular arm of the immune response to also generate virus-specific TRM can provide a secondary method of protection for the host by severely limiting viral replication, and for the population by preventing virus transmission. This is especially important for highly mutable viruses, where variants that partially or fully escape pre-existing antibody responses can persist in circulation. However, T cell-based vaccine platforms that encode a single immunodominant antigen are not practical for humans due to HLA diversity in the population. Rather, an optimal approach would be to encode entire viral proteins, rather than individual epitopes, as vaccine antigens. This strategy would enable delivery of multiple epitopes with the potential to induce virus-specific T cell responses without the need to tailor vaccines to specific HLA types. In addition, including more than one viral protein in the vaccine could increase the likelihood of generating virus-specific T cell responses directed against an immunodominant epitope. For example, immunodominant epitopes for different HLA types have been identified across several influenza proteins such as nucleoprotein, matrix, and polymerase basic protein 35–37, and a vaccine approach combining these antigens could provide broad coverage of T cell epitopes despite HLA diversity in the population.

The respiratory epithelium, particularly in the upper respiratory tract, is the primary target for initial seeding of respiratory infections such as influenza or SARS-CoV-2. In addition, studies in ferrets have shown that transmitted influenza viruses primarily come from the upper respiratory tract, specifically the nasal turbinates 38. This raises interesting questions regarding the relative importance of TRM in different locations throughout the respiratory tract for limiting viral transmission. While this study does not address the contributions of upper respiratory tract (URT) versus lower respiratory tract (LRT) TRM, it is likely that URT TRM play an outsized role in this process as initial transmission events are more likely to occur at this site. In this scenario, it is possible that LRT TRM serve primarily to protect against severe disease by responding to virus that might spread to the lung after propagating in the URT. Statistical analysis of these transmission data also shows that the number of TRM in the respiratory tract negatively correlate with both susceptibility to infection and viral load in the infected mice. The extent to which TRM attenuate transmission will likely vary among different viruses based on properties such as transmission efficiency, replication rates, and viral mechanisms for evading the immune response 39, and these factors must be considered in the development of cell-mediated vaccines against respiratory viruses.

Although CD8 TRM have a broad array of effector functions, our findings show a critical role for IFN-γ in limiting virus transmission. IFN-γ can act directly on epithelial and immune cells to induce an antiviral state, and previous studies have shown that IFN-γ produced by respiratory tract TRM can limit viral replication 17,40. In both transmission models, deletion of IFN-γ or the IFN-γ receptor abrogated the protection from virus-specific TRM. Notably, deletion of perforin and blockade of FasL, primary mediators of cytolytic activity, had minimal effect on TRM-mediated protection. While other mediators may partially compensate for the loss of any single cytolytic pathway, these data suggest that promoting a local antiviral state via cytokine production, rather than direct lysis of infected epithelial cells, is the primary mechanism by which CD8 TRM limit transmission. This also suggests that TRM may not require direct contact with an infected epithelial cell and could potentially mediate their protective effects through release of IFN-γ into the local environment after encountering antigen presented by tissue macrophages or dendritic cells.

Overall, this study demonstrates that TRM can not only reduce pathology in infected individuals but also significantly reduce viral transmission. We show that this reduction in transmission by TRM accrues in two ways. First, TRM can reduce susceptibility to infection, particularly when their numbers are high. Second, by reducing the virus burden in individuals that do get infected, TRM reduce the magnitude and duration of infectivity. These effects are mediated by TRM even in the absence of virus-specific antibody. Immunization strategies that maintained high TRM numbers in the respiratory tract provided durable protection for at least six months, and optimal protection was IFN-γ dependent. These data support a critical and underappreciated role for TRM in limiting respiratory virus transmission. Therefore, they support the continued development of cell-mediated vaccines that can complement current antibody-directed strategies to provide broad protection against evolving viral variants.

Materials and Methods

Mice and viruses

6–8-week-old female C57BL/6 (WT), IFNγR−/−, IFNγ−/−, or Prf−/− mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory and housed under SPF conditions at Emory University. All mice were rested for one week upon arrival. Mice were housed on a 12 hour by 12 hour light/dark cycle with lights turned on from 7:00AM to 7:00PM. The room temperature set point was 72°F and relative humidity was maintained at 40–50%. All experiments were completed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines of Emory University, PROTO201700581. Sample sizes for animal experiments were determined based on previously published work in the field with similar experimental models to provide sufficient statistical power for evaluating the relevant biological effects. Age matched mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups for all experiments. For intranasal priming, 30 PFU Influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (WT PR8), 50 PFU Influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/34 expressing Sendai nucleoprotein FAPGNYPAL epitope (PR8-SenNP), 30,000 50% Egg infectious dose (EID50) A/HKx31 (WT x31), 30,000 PFU A/HKx31 expressing Sendai nucleoprotein FAPGNYPAL peptide (x31-SenNP), 50,000 PFU Live attenuated A/Puerto Rico/8/34 expressing Sendai nucleoprotein FAPGNYPAL peptide (LAIV-SenNP), and 2×107 PFU Adenovirus serotype 5 expressing Sendai nucleoprotein (Ad-SenNP) were administered in a 30μL volume under isoflurane anesthesia 29,41 (Patterson Veterinary). For intraperitoneal priming mice were administered 300,000 PFU in 300μl. Sendai virus encoding Luciferase (Sendai-Luc) was generated and grown as previously described 22. For direct Sendai-Luc infection, 1500 PFU in 30μl was administered intranasally under isoflurane anesthesia. FasL blockade was performed by an initial loading dose of 500 μg i.p. and 400 μg i.n. on the day prior to co-housing, followed by i.p. injection of 250 μg of InVivoMab anti-mouse FasL (BioXCell) per mouse every 3 days 42.

In vivo imaging

Chest hair was removed from mice two days prior to the start of each experiment through shaving and application of depilation cream. All in vivo images were obtained using an In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS) Lumina LT Series III (Perkin Elmer) with an XFOV-24 lens. Ten minutes prior to image acquisition, mice were injected with 3 mg of XenoLIght D-Luciferase (Perkin Elmer) intraperitoneally (i.p.) and anesthetized with isoflurane. A series of images was captured for each cage using a binning of 8, F/stop of 1, and exposure times of 5, 30, and 120 seconds within the Living Image 4.7.3 Software (Perkin Elmer). Background bioluminescence was determined by imaging two uninfected mice daily throughout the course of each experiment. Image analysis was performed using the Living Image 4.7.2 Software (Perkin Elmer). Bioluminescent signal was quantified by manually drawing regions of interest (ROI) around the respiratory tract using known anatomical markers. Data were exported to Microsoft Excel, and the logarithm of total flux (photons/second) was graphed over time for each mouse and area under the curve (AUC) was calculated using GraphPad Prism or R software. If total flux levels decreased by greater than 10-fold or reached background level only to return to previous or higher levels the subsequent day, luciferin injection was considered ineffective, and this time point was excluded from analysis.

Sendai virus plaque assay

For longitudinal detection of viral titers from the nasal cavity of infected mice, virus was collected by dipping the nose of each mouse into 1% BSA in PBS 20 times in a 12 well plate under isoflurane anesthesia. To determine viral titers in the nasal cavity and lung, respective tissues were collected and homogenized in 1% BSA in PBS and kept at −80°C until titration. 4×105 Vero cells (CCL-81, ATCC) were seeded in a 12-well plate and grown to >98% confluency. Tissue homogenates were serially diluted in DMEM and added to cells. All samples were assayed in duplicate. The samples were incubated with the cells at 34°C, 5% CO2, for 1 hour. After incubation, overlay containing 1×MEM, Hepes Buffer, 0.5% Gelatin, 0.5% Agarose (Oxoid), 0.4% BSA, 1×GlutaMAX, 0.02mg/ml PenStrep, 0.3% Sodium Bicarbonate, 5 Units/ml TPCK Trypsin was added to cells and incubated for 4 days at 34°C, 5% CO2. Overlay was then removed, and cells were fixed using 10% Formaldehyde and stained using 1% Crystal violet. Plaques were counted using the following formula: PFU/mL= (Average number of plaques) × (Dilution fold).

Single cell isolation, staining, and flow cytometry

All animals were intravenously labeled via tail vein injection with a fluorescent antibody, either 2mg CD45.2-PE clone 104 or 1.5mg CD3e-PECF594 clone 145-2C11, in 200 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Five minutes following injection, mice were euthanized by i.p. injection of Avertin (2,2,2-tribromoethanol) and brachial exsanguination. Spleen, lungs, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), and nasal cavity were then harvested. Nasal cavity was isolated by first removing skin, the lower jaw, tongue, incisors, zygomatic bones, eyes, hard palette, and remaining soft tissue from the skull. A transverse cut was then made distal to the first molars to minimize capture of olfactory epithelium, and the nasal cavity was placed in ice cold HBSS. To process the nasal cavity, it was cut into small pieces and enzymatically digested in 5 mL of warm HBSS containing 1×106U/L DNAse (Sigma), 5g/L Collagenase D (Roche) and 15U/mL Dispase (Thermo Fisher) at 37°C for 30 min with vortexing every 10 minutes. Spleens were processed by mechanical disruption through a 70mM filter. Lungs were isolated into ice cold HBSS and processed in gentleMACS™ C Tubes using Miltenyi gentleMACS Octo dissociators with heaters (program m_LDK_1) in 2.5 mL warm HBSS containing 1×106U/ml DNase (Sigma) and 5g/ml Collagenase (Roche). After digestion, lymphocytes were isolated using a 40%/80% percoll gradient. BAL was isolated using 5 mL of ice cold R10 (RPMI, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin, streptomycin). Single cell suspensions were strained through 70μM filters and RBC lysed with ACK lysis buffer prior to staining. Cell counts were determined manually using a hemocytometer or LUNA-II automatic cell counter (Logos Biosystems). For flow cytometry, samples were first incubated with Fc block using murine αCD16/32 2.4G2 for 10 minutes on ice. Suspensions were then surface stained with Sendai NP (Kb324–332) tetramer conjugated to APC or PE at a 1:100 dilution for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark, followed by 30 minutes of extracellular staining with fluorescently conjugated antibodies at a 1:100 dilution: CD8α, CD44, CD45.2, CD49a, CD69, CD103, CD19, CD11c, CD11b, Ly6G, SigLecF, Ly6C, CCR2, NK1.1, CD4, EpCAM, CD31, and CD62L. Cell viability was determined using a 1:200 dilution of Zombie NIR (Biolegend) or 7-AAD. Specific details of the antibodies used can be found in Supplementary Information Table 1. Samples were acquired on a Fortessa X20 or FACSymphony A3 (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer or sorted on a FACSAriaII (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry data analysis was conducted using FlowJo v.10 software. All antibodies were purchased from Biolegend, and relevant tetramers were kindly provided by the NIH tetramer core facility in Atlanta, USA or Søren Buus at the Department of Immunology and Microbiology and University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Cytokine analysis

Supernatants from nasal cavity tissue were assayed using the LEGENDplex Mouse Cytokine Release Syndrome Panel Multi-Analyte Flow Assay Kit (BioLegend) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Data were acquired on an Fortessa X20 (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer. Analysis was performed using the Qognit LEGENDplex Data Analysis Software Suite Version 2023-02-15 (BioLegend) and data were graphed in GraphPad Prism v9.

RNA-seq

For each replicate, 2,000 virus-specific CD8 T cells or epithelial cells were sorted into RLT lysis buffer (Qiagen) containing 1% BME and total RNA purified using the Quick-RNA Microprep kit (Zymo Research). All resulting RNA was used as an input for complementary DNA synthesis using the SMART-Seq v4 kit (Takara Bio) and 12 cycles of PCR amplification. Next, 200pg cDNA was converted to a sequencing library using the NexteraXT DNA Library Prep Kit and NexteraXT indexing primers (Illumina) with 12 additional cycles of PCR. Final libraries were pooled at equimolar ratios and sequenced on a HiSeq2500 using 50-bp paired-end sequencing or a NextSeq500 using 75-bp paired-end sequencing. Raw fastq files were mapped to the mm10 build of the mouse genome using STAR 43 with the GENCODE v17 reference transcriptome. The overlap of reads with exons was computed and summarized using the GenomicRanges package 44 and data normalized to fragments per kilobase per million (FPKM). Genes that were expressed at a minimum of three reads per million (RPM) in all samples were considered expressed. DEGs were determined using the glm function in DESeq2 45 using the mouse from which each cell type originated as a covariate. Genes with an FDR of less than 0.05 were considered significant. For GSEA 46, all detected genes were ranked by multiplying the sign of the fold change by the −log10 of the P value between two comparisons. The resulting list was used in a GSEA pre-ranked analysis. All data display was performed in in R v3.6.3.

Data analysis and statistics

Analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v9 or R. We calculated the AUC of the log10(flux) using the trapz function in R and the background AUC was subtracted. The mean background bioluminescence level (arithmetic mean of log10(flux)) was calculated by analyzing longitudinal bioluminescence data from 2 uninfected mice (2 measurements/mouse, total 4 replicate data points per day). The infection limit used in the main analysis was set as the mean+2.5*SD of the background log10(flux). Before calculating AUC, any log10(flux) value below the mean background log10(flux) was replaced by the mean background log10(flux). AUC between groups were compared by Mann-Whitney test using the wilcox_test function in R.

For probabilities of infection and transmission, infected mice were defined as mice with log10(flux) greater than the infection limit. The probability of infection / transmission equals the fraction of contact mice in each group that became infected. Confidence intervals were estimated assuming a binomial probability distribution using the binconf R function. Probability of infection and transmission were compared between groups by proportion test using the prop_test R function.

For correlation of AUC and probability of infection with resident memory CD8+ T cell numbers, the mean log10(TRM) at different locations were correlated with the probability of infection using spearman’s correlation. A line was fitted between AUC and mean log10(TRM) using the glm R function with gaussian family function.

Extended Data

Extended data Fig. 1. Distribution and characterization of tissue-resident Sendai-specific CD8+ T cells limit following intranasal and intraperitoneal infection with recombinant influenza virus.

(a) Schematic of experiment for investigating immunization route on protection from direct infection. (b) Representative plots of tetramer staining at day 35 in immunized mice. (c) Absolute numbers of Sendai NP324–332/Kb+ CD8 T cells in spleen, BAL, lung, and nasal cavity of immunized mice (n=9 for PR8 SenNP i.p. and PR8 SenNP i.n.). (d) Representative plots of staining for TRM markers CD69 and CD103 on antigen-specific cells. (e) Absolute numbers of CD69+CD103+ Sendai NP324–332/Kb+ CD8+ T cells in BAL (n=9 for PR8-SenNP i.n. and n=8 for PR8-SenNP i.p.), lung and nasal cavity (n=10 for PR8-SenNP i.n. and n=9 for PR8-SenNP i.p.). (f) Representative histograms of CD49a, CXCR6, and CXCR3 expression gated on nasal cavity Sendai NP324–332/Kb+ CD8+ T cells following i.n. or i.p. immunization based on TRM marker expression (CD69+CD103+, red; CD69+CD103−, black; CD69−CD103−, green). (g) Frequency of CD49a, CXCR6, and CXCR3 expression on Sendai NP324–332/Kb+ CD69+CD103+ CD8+ T cells in the nasal cavity (n=5 per group) following i.n. or i.p. immunization. Data are representative of two individual experiments. Lines represent mean values (c, e, g). Statistical significance was determined using two-sided Mann Whitney test. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001, ns: non-significant.

Extended data Fig. 2. Sendai-luciferase bioluminescence strongly correlates with viral titer.

(a) Bioluminescence in Sendai-Luc infected mice combined with viral titer from the total respiratory tract (nasal cavity, trachea, and lungs) on days 2, 4 and 6 post-infection. Black dots represent viral titer, grey curves represent bioluminescence of individual mice, and dotted black line represents background bioluminescence. (b) Correlation of bioluminescence with viral titers. Data shown are from two independent pooled experiments with 10 mice per timepoint.

Extended data Fig. 3. Contact mice that show no indication of transmission by bioluminescence also fail to develop a Sendai-specific T cell response.

(a) Schematic of experiment investigating the cellular immune response in bioluminescence-positive versus bioluminescence-negative contact mice. (b) Representative flow cytometry plots of Sendai NP324–332Kb+ tetramer staining gated on CD8+ T cells in the BAL, lung, nasal cavity, and spleen. (c) Number of total Sendai NP324–332Kb+ CD8 T cells in the BAL, lung, nasal cavity, and spleen in contact mice 35 after co-housing with PR8-SenNP or WT PR8 immunized index mice. (d) Number of CD69+CD103+ Sendai NP324–332Kb+ CD8 TRM in the BAL, lung, and nasal cavity in contact mice 35 days after co-housing with PR8-SenNP or WT PR8 immunized index mice. Data are representative of two individual experiments with n = 7 mice per group. Lines represent mean values and error bars represent standard deviation (c, d).

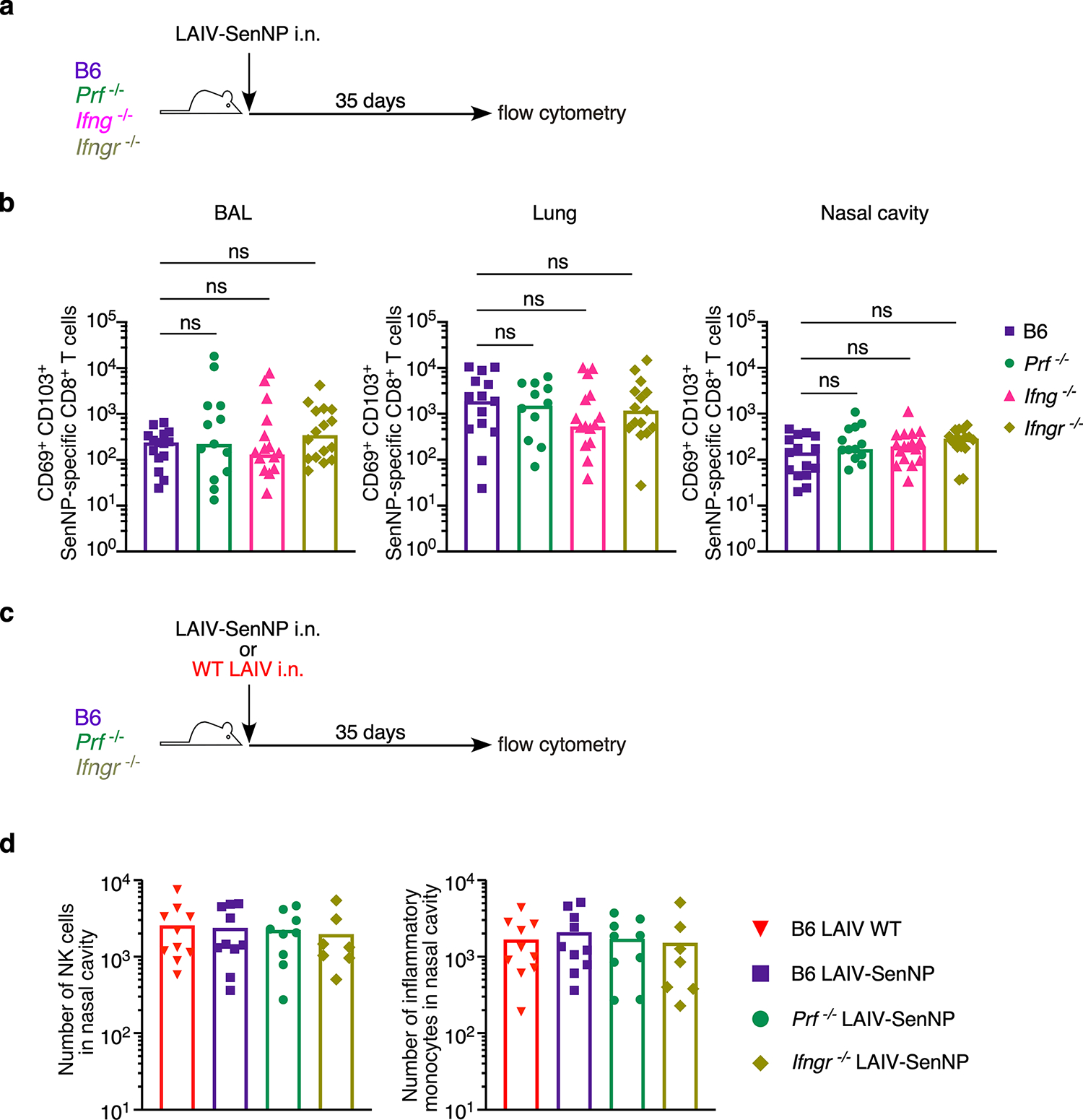

Extended data Fig. 4. Number of SenNP-specific CD8+ TRM in knockout mouse strains following immunization.

(a) Experimental schematic for immunizing WT and knockout mouse strains. (b) Number of CD69+ CD103+ Sendai NP324–332/Kb+ CD8 TRM in the BAL, lung, and nasal cavity 35 days after immunization with LAIV-SenNP for WT (n=15), Prf−/− (n=12 for BAL, n=13 for lungs and nasal cavity), Ifng−/− (n=18), and Ifngr−/− (n=16 for lungs and nasal cavity, n=15 for BAL). Data shown are from 3 independent pooled experiments. (c) Experimental schematic for immunizing WT and knockout mouse strains. (d) Number of NK cells (left graph) and inflammatory monocytes (right graph) in the nasal cavity 35 days after immunization with LAIV WT (n=10) or LAIV-SenNP (n=10 for WT, n=9 for Prf−/−, n=7 for Ifngr−/−). Data shown are from 2 pooled independent experiments. Lines represent means (b, d). Statistical significance was determined using two-sided Mann Whitney test. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001, ns: non-significant.

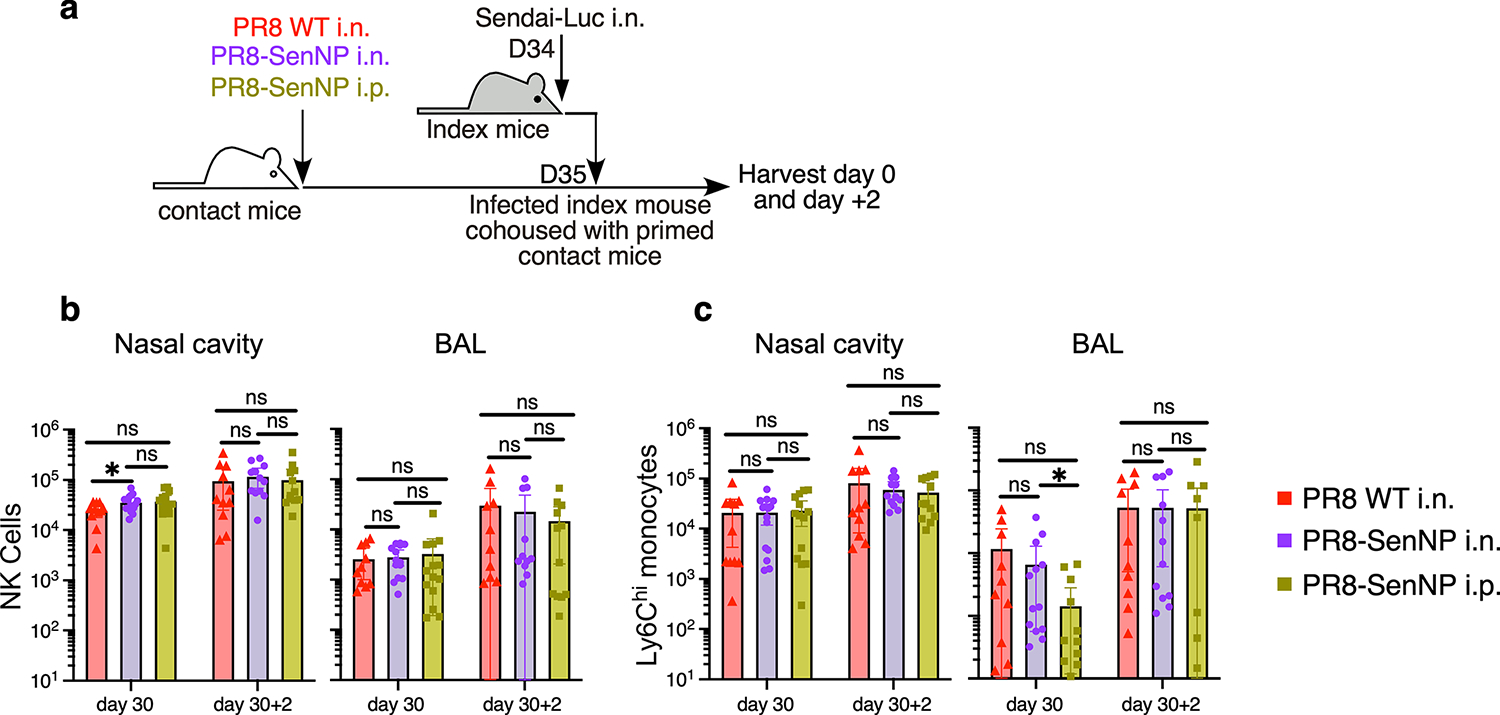

Extended data Fig. 5. Immunization does not alter influx of NK cells and monocytes following Sendai virus transmission.

(a) Experimental schematic where immunized contact mice were cohoused with a Sendai-Luc infected index mouse and tissues analyzed for innate immune populations at the time of cohousing (D30) and two days after cohousing (D30+2). (b) Number of NK cells in nasal cavity (D30: n=11 for PR8 WT i.n., n=15 for PR8-SenNP i.n., n=14 for PR8-SenNP i.p.) (D30+2: n= 11 for PR8 WT i.n., n=12 for PR8-SenNP i.n., n=12 for PR8-SenNP i.p.) and BAL (D30: n=10 for PR8 WT i.n., n=14 for PR8-SenNP i.n., n=14 for PR8-SenNP i.p.) (D30+2: n=11 for PR8 WT i.n., n=11 for PR8-SenNP i.n., n=12 for PR8-SenNP i.p.). (c) Number of inflammatory monocytes in nasal cavity and BAL (same n as (b), except n=12 for D30+2 PR8-SenNP i.n. in BAL). Data shown are from 3 independent experiments. Lines represent means and error bars represent 95% confidence interval (b, c). Statistical significance was determined using two-sided Mann Whitney test. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001, ns: non-significant.

Extended data Fig. 6. Sendai-specific TRM numbers and assessment of transmission under different immunization strategies at 1- and 6-months post-immunization.

(a) Experimental schematic where contact mice, immunized as indicated, were cohoused with a Sendai-Luc infected index mouse at 35- or 180-days post-immunization. (b) Number of CD69+CD103+ Sendai NP324–332/Kb+ CD8 TRM in the BAL, lung, and nasal cavity at 1 month or six months post-immunization with x31-SenNP i.n. (n=10 per timepoint except n=9 for 1 month BAL), PR8-SenNP i.p. (n=10 per timepoint except n=9 for 1 month BAL), PR8-SenNP i.n. (1 month n=9 for lung and nasal cavity and n=6 for BAL, 6 month n=10 for lung and nasal cavity and n=9 for BAL), LAIV-SenNP i.n. (1 month n=8, 6 month n=10), and Ad-SenNP i.n. (1 month n=9 for lung and nasal cavity and n=8 for BAL, 6 month n=10 for nasal cavity and BAL, n=9 for lung). (c and d) Bioluminescence curves of immunized contact mice following exposure to an infected index mouse at 1 month (c) or 6 months (d) post-immunization with x31 WT (1 month n=14, 6 month n=16), x31-SenNP (1 month n=16, 6 month n=15), PR8-SenNP i.p. (1 month n=16, 6 month n=16), PR8-SenNP i.n. (1 month n=16, 6 month n=16), LAIV-SenNP i.n. (1 month n=15, 6 month n=16), and Ad-SenNP i.n. (1 month n=15, 6 month n=16). Solid dark lines represent means, solid pale lines represent individual mice, dashed grey line represents background bioluminescence, and dashed red line represents the limit of infection (c, d). Solid lines (b) and error bars (b-d) represent mean with 95% confidence interval. Statistical significance was determined using two-sided Mann Whitney test. Data are combined from two independent experiments. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001, ns: non-significant.

Extended data Fig. 7. High viral burden in index mice does not correlate with increased viral burden in contact mice.

Contact mice were infected intranasally with WT x31 (n=14), x31-SenNP (n=16), PR8-SenNP (n=16), or Ad-SenNP (n=15) and cohoused with a Sendai-Luc infected index mouse at day 35 post-immunization. n= 4 index mice per immunization group are plotted. Total viral burden (AUC) of the co-housed index and contact mice were plotted for each cage. Data were fitted to a generalized linear model with gaussian family for each immunization group to investigate the relationship between AUCs of the index mice and contact mice. Data are combined from two independent experiments.

Extended data Fig. 8. Pre-existing immunity to related influenza strains limits the efficacy of protective T cell immunity induced by LAIV-SenNP immunization but can be overcome by Ad-SenNP immunization.

(a) Experimental schematic for testing the impact of pre-existing influenza immunity on the ability of LAIV-SenNP to protect against transmission. (b) Bioluminescence curves of A/Cal/09 i.p. & PR8 LAIV WT (n=16), PBS i.p. & PR8 LAIV-SenNP (n=16), A/Cal/09 i.p. & PR8 LAIV-SenNP (n=20), and A/Cal/09 i.p. & Ad-SenNP (n=16) immunized contact mice following exposure to an infected index mouse 30 days after the second immunization. Solid dark lines represent means, solid pale lines represent individual mice, dashed grey line represents background bioluminescence, and dashed red line represents the limit of infection. (c) AUC of bioluminescence in immunized contact mice that become infected following co-housing with an infected index mouse. (d) Probability of infection for immunized contact mice calculated as the proportion of contact mice that became infected. Bars represent 95% binomial confidence intervals (d). Lines represent means (b-d) and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals (b, c). Data are combined from two independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using two-sided Mann Whitney test. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001, ns: non-significant.

Extended data Figure 9. Heterologous influenza prime-boost does not improve the durability of respiratory tract TRM.

(a) Experimental schematic to assess the durability of respiratory tract TRM following heterologous PR8-SenNP or Ad-SenNP boosting. (b) Number of CD69+CD103+ Sendai NP324–332Kb+ CD8 TRM in the BAL, lung, and nasal cavity at day 120. Data are combined from two independent experiments with n= 10 mice for PR8 WT i.n., PR8-SenNP i.n., and Ad-SenNP i.n. secondary immunization groups. Lines represent means. Statistical significance was determined using two-sided Mann Whitney test. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001, ns: non-significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the NIH tetramer core facility at Emory University for Sendai NP324–332, influenza NP366–374, and influenza PA224–233 tetramers (NIAID contract 75N93020D00005). We thank the Emory+Children’s Flow Cytometry Core for cell sorting and the Emory Integrated Genomics Core for assistance with preparation of RNA sequencing libraries. This work was supported by NIH grants R35 HL150803 and U01 HL139483 (J.E.K.). I.U. was supported by Lundbeck Foundation and Carlsberg Foundation. C.M. was supported by F31 HL164049. S.E.M. was supported by F31 HL168914.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Materials & Correspondence

Materials and data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The Sendai-Luciferase virus is available from C.J.R. under a materials transfer agreement.

Data Availability

All RNA-sequencing data is available from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession GSE247464 (Figure 2) and GSE247376 (Figure 4). All other source data are provided with this paper.

References

- 1.Viana R et al. Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in southern Africa. Nature 603, 679–686 (2022). 10.1038/s41586-022-04411-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng MZM & Wakim LM Tissue resident memory T cells in the respiratory tract. Mucosal Immunol 15, 379–388 (2022). 10.1038/s41385-021-00461-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson SA & Sant AJ Potentiating Lung Mucosal Immunity Through Intranasal Vaccination. Front Immunol 12, 808527 (2021). 10.3389/fimmu.2021.808527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mettelman RC, Allen EK & Thomas PG Mucosal immune responses to infection and vaccination in the respiratory tract. Immunity 55, 749–780 (2022). 10.1016/j.immuni.2022.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayward SL et al. Environmental cues regulate epigenetic reprogramming of airway-resident memory CD8(+) T cells. Nat Immunol 21, 309–320 (2020). 10.1038/s41590-019-0584-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grau-Exposito J et al. Peripheral and lung resident memory T cell responses against SARS-CoV-2. Nat Commun 12, 3010 (2021). 10.1038/s41467-021-23333-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dejnirattisai W et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron-B.1.1.529 leads to widespread escape from neutralizing antibody responses. Cell 185, 467–484 e415 (2022). 10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith DJ et al. Mapping the antigenic and genetic evolution of influenza virus. Science 305, 371–376 (2004). 10.1126/science.1097211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valkenburg SA et al. The Hurdles From Bench to Bedside in the Realization and Implementation of a Universal Influenza Vaccine. Front Immunol 9, 1479 (2018). 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auladell M et al. Recalling the Future: Immunological Memory Toward Unpredictable Influenza Viruses. Front Immunol 10, 1400 (2019). 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassert M & Harty JT Tissue resident memory T cells-A new benchmark for the induction of vaccine-induced mucosal immunity. Front Immunol 13, 1039194 (2022). 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1039194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rimmelzwaan GF, Kreijtz JH, Bodewes R, Fouchier RA & Osterhaus AD Influenza virus CTL epitopes, remarkably conserved and remarkably variable. Vaccine 27, 6363–6365 (2009). 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li ZT et al. Why Are CD8 T Cell Epitopes of Human Influenza A Virus Conserved? J Virol 93 (2019). 10.1128/JVI.01534-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhatt S, Holmes EC & Pybus OG The genomic rate of molecular adaptation of the human influenza A virus. Mol Biol Evol 28, 2443–2451 (2011). 10.1093/molbev/msr044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zens KD, Chen JK & Farber DL Vaccine-generated lung tissue-resident memory T cells provide heterosubtypic protection to influenza infection. JCI Insight 1 (2016). 10.1172/jci.insight.85832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu T et al. Lung-resident memory CD8 T cells (TRM) are indispensable for optimal cross-protection against pulmonary virus infection. J Leukoc Biol 95, 215–224 (2014). 10.1189/jlb.0313180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMaster SR, Wilson JJ, Wang H & Kohlmeier JE Airway-Resident Memory CD8 T Cells Provide Antigen-Specific Protection against Respiratory Virus Challenge through Rapid IFN-gamma Production. J Immunol 195, 203–209 (2015). 10.4049/jimmunol.1402975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang J et al. Respiratory mucosal immunity against SARS-CoV-2 following mRNA vaccination. Sci Immunol, eadd4853 (2022). 10.1126/sciimmunol.add4853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pizzolla A et al. Resident memory CD8(+) T cells in the upper respiratory tract prevent pulmonary influenza virus infection. Sci Immunol 2 (2017). 10.1126/sciimmunol.aam6970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowen AC, Bouvier NM & Steel J Transmission in the guinea pig model. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 385, 157–183 (2014). 10.1007/82_2014_390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burke CW, Bridges O, Brown S, Rahija R & Russell CJ Mode of parainfluenza virus transmission determines the dynamics of primary infection and protection from reinfection. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003786 (2013). 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burke CW et al. Illumination of parainfluenza virus infection and transmission in living animals reveals a tissue-specific dichotomy. PLoS Pathog 7, e1002134 (2011). 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang S, Mozdzanowska K, Palladino G & Gerhard W Heterosubtypic immunity to influenza type A virus in mice. Effector mechanisms and their longevity. J Immunol 152, 1653–1661 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMaster SR et al. Pulmonary antigen encounter regulates the establishment of tissue-resident CD8 memory T cells in the lung airways and parenchyma. Mucosal Immunol 11, 1071–1078 (2018). 10.1038/s41385-018-0003-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gooch KE et al. Heterosubtypic cross-protection correlates with cross-reactive interferon-gamma-secreting lymphocytes in the ferret model of influenza. Sci Rep 9, 2617 (2019). 10.1038/s41598-019-38885-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piet B et al. CD8(+) T cells with an intraepithelial phenotype upregulate cytotoxic function upon influenza infection in human lung. J Clin Invest 121, 2254–2263 (2011). 10.1172/JCI44675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Topham DJ, Tripp RA & Doherty PC CD8+ T cells clear influenza virus by perforin or Fas-dependent processes. J Immunol 159, 5197–5200 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schenkel JM, Fraser KA, Vezys V & Masopust D Sensing and alarm function of resident memory CD8(+) T cells. Nat Immunol 14, 509–513 (2013). 10.1038/ni.2568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uddback I et al. Long-term maintenance of lung resident memory T cells is mediated by persistent antigen. Mucosal Immunol 14, 92–99 (2021). 10.1038/s41385-020-0309-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slutter B, Pewe LL, Kaech SM & Harty JT Lung airway-surveilling CXCR3(hi) memory CD8(+) T cells are critical for protection against influenza A virus. Immunity 39, 939–948 (2013). 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilchuk P et al. A Distinct Lung-Interstitium-Resident Memory CD8(+) T Cell Subset Confers Enhanced Protection to Lower Respiratory Tract Infection. Cell Rep 16, 1800–1809 (2016). 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMahan K et al. Correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques. Nature 590, 630–634 (2021). 10.1038/s41586-020-03041-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bertoletti A, Le Bert N & Tan AT SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells in the changing landscape of the COVID-19 pandemic. Immunity (2022). 10.1016/j.immuni.2022.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clemens EB, van de Sandt C, Wong SS, Wakim LM & Valkenburg SA Harnessing the Power of T Cells: The Promising Hope for a Universal Influenza Vaccine. Vaccines (Basel) 6 (2018). 10.3390/vaccines6020018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gotch F, McMichael A, Smith G & Moss B Identification of viral molecules recognized by influenza-specific human cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med 165, 408–416 (1987). 10.1084/jem.165.2.408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boon AC et al. The magnitude and specificity of influenza A virus-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in humans is related to HLA-A and -B phenotype. J Virol 76, 582–590 (2002). 10.1128/jvi.76.2.582-590.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koutsakos M et al. Human CD8(+) T cell cross-reactivity across influenza A, B and C viruses. Nat Immunol 20, 613–625 (2019). 10.1038/s41590-019-0320-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richard M et al. Influenza A viruses are transmitted via the air from the nasal respiratory epithelium of ferrets. Nat Commun 11, 766 (2020). 10.1038/s41467-020-14626-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang W & Shaman J Viral replication dynamics could critically modulate vaccine effectiveness and should be accounted for when assessing new SARS-CoV-2 variants. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 16, 366–367 (2022). 10.1111/irv.12961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacobs S, Zeippen C, Wavreil F, Gillet L & Michiels T IFN-lambda Decreases Murid Herpesvirus-4 Infection of the Olfactory Epithelium but Fails to Prevent Virus Reactivation in the Vaginal Mucosa. Viruses 11 (2019). 10.3390/v11080757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Methods references

- 41.Lobby JL, Uddbäck I, Scharer CD, Mi T, Boss JM, Thomsen AR, Christensen JP, Kohlmeier JE. Persistent Antigen Harbored by Alveolar Macrophages Enhances the Maintenance of Lung-Resident Memory CD8+ T Cells. J Immunol. 2022. Nov 1;209(9):1778–1787. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2200082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Upadhyay R, Boiarsky JA, Pantsulaia G, Svensson-Arvelund J, Lin MJ, Wroblewska A, Bhalla S, Scholler N, Bot A, Rossi JM, Sadek N, Parekh S, Lagana A, Baccarini A, Merad M, Brown BD, Brody JD. A Critical Role for Fas-Mediated Off-Target Tumor Killing in T-cell Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2021. Mar;11(3):599–613. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dobin A et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawrence M et al. Software for computing and annotating genomic ranges. PLoS Comput Biol 9, e1003118 (2013). 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Love MI, Huber W & Anders S Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550 (2014). 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Subramanian A et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 15545–15550 (2005). 10.1073/pnas.0506580102S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All RNA-sequencing data is available from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession GSE247464 (Figure 2) and GSE247376 (Figure 4). All other source data are provided with this paper.