Abstract

Introduction

COVID-19 vaccines are generally safe and effective; however, they are associated with various vaccine-induced cutaneous side effects. Several reported cases of primary cutaneous lymphomas (CLs) following the COVID-19 vaccination have raised concerns about a possible association. This systematic review aims to investigate and elucidate the potential link between CLs and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

Methods

We performed a systematic literature search on PubMed, EBSCO and Scopus from January 01, 2019, to March 01, 2023, and analyzed studies based on determined eligibility criteria. The systematic review was performed based on the PRISMA protocol.

Results

A total of 12 articles (encompassing 24 patients) were included in this analysis. The majority of CLs were indolent cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCLs) (66,7%; 16/24), with Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) being the most common type (33,3%; 8/24). Most patients (79,2%; 19/24) developed lesions after receiving the COVID-19 mRNA-based vaccines, and predominantly after the first immunization dose (54,2%; 13/24). The presented CLs cases exhibited a tendency to exacerbate following subsequent COVID-19 vaccinations. Nevertheless, CLs were characterized by a favorable course, leading to remission in most cases.

Conclusion

The available literature suggests an association between the occurrence and exacerbation of CLs with immune stimulation following COVID-19 vaccination. We hypothesize that post-vaccine CLs result from an interplay between cytokines and disrupted signaling pathways triggered by vaccine components, concurrently playing a pivotal role in the pathomechanism of CLs. However, establishing a definitive causal relationship between these events is currently challenging, primarily due to the relatively low rate of reported post-vaccine CLs. Nonetheless, these cases should not be disregarded, and patients with a history of lymphoproliferative disorders require post-COVID-19 vaccination monitoring to control the disease’s course.

Systematic review registrationwww.researchregistry.com, identifier [1723].

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine, COVID-19, cutaneous lymphomas, side effects, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) a global pandemic. According to the WHO COVID-19 dashboard, as of January 2024, over 770 million cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed, including more than 7 million deaths (1). The urgency of the pandemic required rapid development and introduction of vaccines, resulting in a relatively short follow-up period, which raised concerns about their safety. The mRNA-based vaccines (Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna) were the first to be approved by US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for preventing COVID-19 disease (2). Both mRNA vaccines demonstrated very high efficacy with mild to moderate adverse events (AEs) in the phase 3 randomized clinical trials (3, 4). The COVID-19 pandemic led to the development and approval of other vaccine types to control viral transmission. As of 8 April 2022, World Health Organization (WHO) has determined that the following authorized vaccines: inactivated-based vaccines (Sinovac, Covaxin, and Sinopharm), vector-based vaccines (AstraZeneca/Oxford, Johnson and Johnson, CanSino), mRNA-based vaccines (Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna), and a subunit protein-based vaccine (Nuvaxovid and Covovax) against COVID-19 meet the required criteria for both safety and efficacy (5).

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, mass vaccination programs have been implemented worldwide. To date, 67% of total population have been vaccinated with a complete primary series of a COVID-19 vaccine, and 32% with at least one booster dose (1). Consequently, there is a growing body of real-world evidence on AEs linked to the use of the COVID-19 vaccines. All available COVID-19 vaccines seem to be generally effective and safe; however, they are not devoid of side effects. According to data, the majority of side effects of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines are mild to moderate, including fever, fatigue, headache, muscle ache, and cutaneous manifestations at the injection site (3, 4, 6, 7). However, various rare cases of new-onset or flare of immune-mediated diseases, as well as hematologic malignancies and primary cutaneous lymphomas (CLs), have been reported (8–22).

The CLs represent a diverse group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas arising from T- or B-lymphocytes, primarily affecting the skin. They are classified as rare diseases, with estimated incidence rates ranging from 0.64 to 0.87 per 100,000 person-years, according to studies from the United States (23–25). Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCLs) constitute 75–80% of all CLs, while primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas (CBCLs) constitute 20–25% (26, 27). The incidence rates vary geographically, with a slightly higher prevalence of CTCL in Asian and South American countries compared to Europe (28, 29). CLs are categorized into distinct subtypes that vary in terms of clinical presentation, behavior, histological features, and treatment. The clinical course of CLs is also highly variable, ranging from an indolent, slowly progressive course when the immune system controls tumor growth to aggressive forms with extracutaneous involvement and a poor prognosis (26). Mycosis fungoides (MF) and primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders (CD30+ LPDs) account for nearly 80% of all CTCLs and are classified as indolent lymphomas (26, 27). Sézary syndrome (SS) represents the most common subtype among aggressive CTCLs, accounting for approximately 3% of all CTCLs (26, 27). MF and SS predominantly affect adults, with the peak incidence occurring in the sixth and seventh decades of life (26, 27). The male-to-female ratio also shows variability among different subtypes. MF typically presents as skin patches, plaques, and tumors, while SS is characterized by cutaneous involvement and a leukemic component. Other CTCLs are considered rare and collectively account for less than 10% of CTCLs cases (26).

The pathogenesis of CTCL is complex and not fully understood. The role of genetic, immunological, and environmental factors is being emphasized. Environmental mechanisms which may play a role in the evolution of CLs include long-term antigen stimulation by viral/microbial pathogens, drug triggers, geographic and occupational associations (30–33). The molecular and immunological processes lead to the clonal expansion of lymphocytes within the skin. Molecular alterations and immunological dysregulation, including impaired T-cell function, dysregulated cytokine signaling pathways, and altered cytokine profiles, play a pivotal role in driving malignant transformation, and disease progression (34, 35). Moreover, the interaction between malignant lymphocytes and the inflammatory microenvironment of the skin seems to be crucial in evading immune surveillance and sustaining the neoplastic process (35, 36).

In the context of CLs pathogenesis, the immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines appears to have the potential to influence the course of specific subset of the diseases, particularly lymphoproliferative disorders, including lymphomas such as CTCLs. However, there is limited evidence regarding the impact of vaccines on the cancer course in patients, particularly those with altered immunity due to lymphoproliferative malignancies. Therefore, the objective of the systematic literature review was to examine the association between COVID-19 vaccination and the occurrence or exacerbation of CLs.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and study selection

This study was conducted under the Guideline of Preferred Reporting Items Systematic Meta-Analyses Checklist (PRISMA) (37). The review protocol was registered at Research Registry (UIN: Review Registry 1723). The online search was conducted independently by two authors (B.O and A.Z.) on electronic websites, databases, and journals, including PubMed, Scopus, and EBSCO from January 01, 2019, to March 01, 2023. Discrepancies were solved by the third reviewer. Additionally, we manually screened references or citations of each article. The search was conducted using the combination of the following keywords and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms: COVID vaccine, BNT162, ChAdOX1, AstraZeneca, mRNA-1273, cutaneous lymphoma, Lymphomatoid papulosis, Mycosis fungoides, Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2.

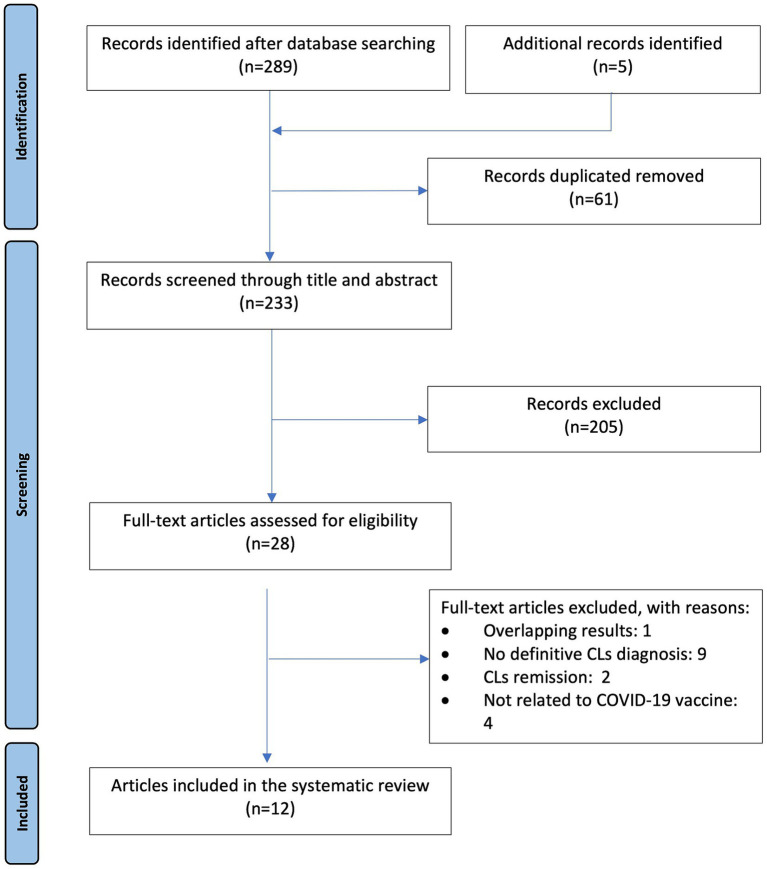

Inclusion criteria were studies describing patients with a definitive diagnosis of CLs who experienced onset, relapse, or exacerbation after immunization with a COVID-19 vaccine with WHO Emergency Use Listing. Case reports, letters to the editor, conference abstracts and case series were included. Articles involving children (<18 years), reviews, duplicate studies, personal experience summaries, lymphomas other than primary cutaneous, resolution of CLs, doubtful diagnosis of CLs, studies not meeting the inclusion criteria of this study or in a language other than English were excluded. Initial screening involved the evaluation of titles and abstracts, followed by a full-text assessment for eligibility. Additionally, references cited in relevant papers were also followed up for additional studies. The PRISMA flow diagram of the search method used in this systematic review is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study according to PRISMA (37).

Data extraction and data synthesis

Two researchers (B.O. and A.Z.) extracted the following information from full-text articles: first author (reference); age; sex; SARS-CoV-2 vaccine type and doses administered; the time between administration and lesions onset; definitive diagnosis before and after vaccination; management; outcomes. The selected articles were double-checked by other researchers. A narrative synthesis was performed, and data focusing on population, intervention, comparison and outcome were synthesized through descriptive statistical analyses using Microsoft Excel software.

Quality assessment

The quality of case reports and case series included in the systematic review was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Reports and Case Series (38). The overall quality of the included studies was assessed: A “low risk” of bias score was defined when responses of “yes” to all of the applicable questions was provided. When at least one answer to applicable questions was found “unclear,” a scoring of “moderate risk” was defined. The response of “no” to at least one of the questions rendered it to be of “high risk” of bias.

Results

We identified potential 294 records, 61 duplicates were excluded, 204 were excluded after the title and abstract screening and 17 were excluded after the full-text screening. Finally, 12 articles met the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the systematic review. The majority of publications were case reports (n = 5) and letters to the editor (n = 5), followed by research letter (n = 1) and conference abstract (n = 1). The cohort comprised 24 patients, including 15 males and 9 females, with a median age of 60.5 years (range, 20–80 years). All 24 patients were diagnosed with CLs after COVID-19 vaccination, all of which were CTCLs. The details of each case are presented in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies reporting primary cutaneous lymphomas following COVID-19 vaccination.

| No./reference | Age/gender | Time from vaccination to onset of lesions | Type and dose of vaccine | Type of CLs before vaccination | HP examination after vaccination | CD30 | Stage before vaccination | Course of CLs after vaccinations | Treatment and outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (11) | 70/M | 2 days after 1st dose | mRNA vaccine-BNT162b2 | pcALCL | pcALCL | + | CR | Relapse | SR |

| 2 (12) | 60/M | 4 weeks after 1st dose | Viral vector- AZD122 | Folliculotropic MF-early stage | CD30+ LCT-MF tumor stage | + | R | Exacerbation; Progression after 2 dose | ? |

| 3 (12) | 73/F | 10 days after 1st dose | Viral vector- AZD122 | MF – early stage and LyP type-A | LyP type-A | + | R | Relapse | ? |

| 4 (13) | 60/M | 7 days after 1 st dose | Viral vector - AZD122 | − | LyP type- D | + | − | New-onset | SR |

| 5 (13) | 66/F | 10 days after 1 st dose | mRNA vaccine-BNT162b2 | − | Ly type-D | + | − | New-onset; Exacerbation after 2 dose | NB-UVB – CR, recurrence, MTX- current treatment |

| 6 (14) | 56/F | 2 days after 1st dose | mRNA vaccine-BNT162b2 2 dose; mRNA1273 | − | CD8+ MF | ? | − | New-onset; Exacerbation after 2 dose | TCS – CR |

| 7 (15) | 28/F | Few days after 1st dose | Viral vector– Ad26.COV2.S | − | SPTCL | − | − | New-onset | CsA, SCS – CR (with atrophy) |

| 8 (16) | 79/M | 3 days after vaccine booster | mRNA vaccine booster- mRN-1273 | − | PCGD-TCL | − | − | New-onset | Surgical excision, RT- CR |

| 9 (17) | 53/M | 3 days after 1st dose | mRNA vaccine- BNT162b2 | − | pcENKTL | + | − | New-onset; Exacerbation after 2 dose | CHT, RT-? |

| 10 (18) | 76/M | 10 days after vaccine booster | mRNA vaccine booster- mRN-1273 | - | PC-ALCL | + | − | New-onset | SR |

| 11 (19) | 62/F | Several days after 2nd dose | mRNA vaccine- BNT162b2 | − | CD8+ pcPTL-NOS | +/− | − | New-onset; progression after SARS-CoV-2 infection | TCS, SCS, MTX, BV- Lack of response |

| 12 (20) | 50/M | 4 days after 1st dose | mRNA vaccine- BNT162b2 | − | LyP type-A | − | − | New-onset | MTX- CR |

| 13 (20) | 20/F | 42 days after 1 dose | mRNA vaccine- BNT162b2 | − | LyP type-A | + | − | New-onset | MTX- CR |

| 14 (21) | 79/M | 30 days after 1st dose | Inactivated SARSCoV2 viral vaccine- CoronaVac (Sinovac) | − | pcPTL-NOS | − | − | New-onset; exacerbation after 2 nd (inactivated virus vaccine) and 3 rd dose (recombinant adenovirus mechanism) | ? |

| 15 (22) | 67/M | 15 days after 2nd dose | mRNA vaccine-BNT162b2 | LyP type-A diagnosed in 2019, relapsed in 2020 | LyP type-A | ? (+) | − | Relapse | MTX- CR |

| 16 (22) | 49/M | 15 days after 2nd dose | mRNA vaccine-BNT162b2 | CD4+ PCSM-LPD | CD4+ PCSM-LPD | ? | CR | Relapse | SR |

| 17 (22) | 58/M | 2 days after 2nd dose | mRNA vaccine-BNT162b | SS | SS | ? | CR | Relapse | TCS, SCS, MOGA – CR |

| 18 (22) | 61/M | 14 days after 3rd dose | mRNA vaccine-BNT162b | MF-early-stage | Erythrodermic MF | ? | SD | Progression | OCS, PUVA - CR |

| 19 (22) | 61/M | 15 days after 3rd dose | mRNA vaccine-BNT162b | SS | SS | ? | Well-managed | Relapse | ECP- PR |

| 20 (22) | 80/F | 15 days after 3rd dose | mRNA vaccine-BNT162b | − | SS | ? | − | New-onset | TCS, SCS- CR |

| 21 (22) | 60/M | 30 days after 2nd dose | mRNA vaccine-BNT162b | − | LyP type- A | ? (+) | − | New-onset | SCS, Trimeton- CR |

| 22 (22) | 52/F | 3 days after 1st dose | mRNA vaccine-BNT162b | − | CD4+ PCSM-LPD | ? | − | New- onset | RT- CR |

| 23 (22) | 61/F | 10 days after 1st dose | mRNA vaccine-BNT162b | − | LyP type- A | ? (+) | − | New- onset | SR |

| 24 (22) | 45/M | 20 days after 3rd dose | mRNA vaccine- BNT162b | − | CD4+ PCSM-LPD | ? | − | New- onset | Surgical excision – CR |

Ad26.COV2.S, Janssen vaccine; AZD122, AstraZeneca vaccine; BNT162b2, BioNTech, Pfizer COVID-19 mRNA vaccine; BV, brentuximab vedotin; CD4+ PCSM-LPD, CD4+ primary cutaneous small/medium T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder; CHT, chemotherapy; CR, complete remission; CsA, cyclosporin; ECP, extracorporeal photopheresis; LyP, lymphomatoid papulosis; MF, mycosis fungoides; MOGA, mogamulizumab; mRNA1273, Moderna COVID-19 vaccine; MTX, methotrexate; pcALCL, primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma; PCGD-TCL, primary cutaneous γ/δ T-cell lymphoma; pcENKTL, primary cutaneous extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma; pcPTL-NOS, primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified; R, remission; RT, radiotherapy; SCS, systemic corticosteroids; SD, stable disease; SPTCL, Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma; SR, spontaneous remission; SS, Sézary syndrome; TCS, topical corticosteroids;?: data not provided.

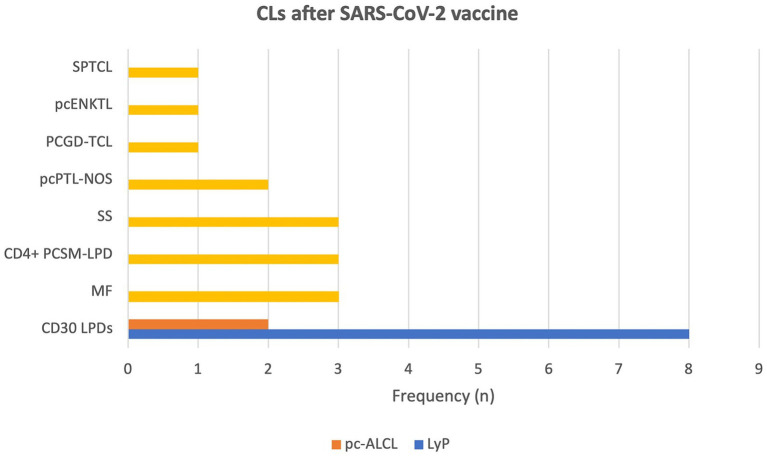

The majority of reported CLs were indolent CTCLs (66,7%; 16/24), followed by aggressive CTCLs (33,3%; 8/24). CD30+ LPDs were the most frequently reported subgroup of CTCLs (41,7%; 10/24) with LyP being the most common type (33,3%; 8/24) (12, 13, 20, 22) followed by primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (pc-ALCL) (8,3%; 2/24) (11, 18). Other reported CLs were 2 cases of MF (14, 22) including CD8+ MF, 3 cases of primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder (CD4+ PCSM-LPD) (22) and single case of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) (15). Reported cases of aggressive CTCLs included 3 cases of SS (22), 2 primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphomas, not otherwise specified (pcPTL-NOS) (19, 21) followed by single case of primary cutaneous γ/δ T-cell lymphoma (PCGD-TCL) (16), mycosis fungoides with large cell transformation (MF-LCT) (12) and primary cutaneous (extranodal) NK/T-cell lymphoma (pcENKTL) (17). The summarized data are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of frequencies in reported types of primary cutaneous lymphomas after SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. (CD4+ PCSM-LPD, CD4+ primary cutaneous small/medium T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder; LyP, lymphomatoid papulosis; MF, mycosis fungoides; pcALCL, primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma; PCGD-TCL, primary cutaneous γ/δ T-cell lymphoma; pcENKTL, primary cutaneous extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma; pcPTL-NOS, primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified; SPTCL, subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma; SR, spontaneous remission; SS, Sézary syndrome).

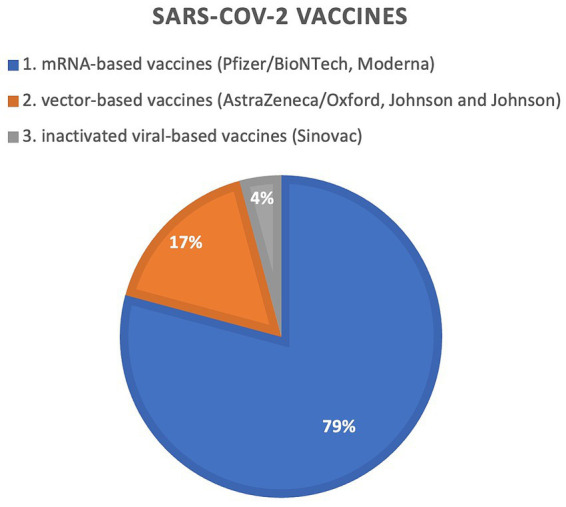

The available data are limited, however, histologic examination revealed a predominant feature of T-cell phenotype, 12 out of 16 (75%) reported cases presented expression of CD30+ antigen (11–13, 17–20, 22). In 8 cases, data regarding CD30 expression in histopathology were missing (14, 22). The vast majority of patients (79,2%; 19/24) developed lesions after receiving COVID-19 mRNA-based vaccines, followed by vector-based vaccines (16,7%; 4/24) and inactivated SARSCoV2 viral vaccine (4,1%; 1/24). We have summarized the data in Figure 3. More than half (66,6%; 16/24) of the patients received the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine (11, 13, 14, 17, 19, 20, 22), while the rest got AstraZeneca/Oxford (12,5%; 3/24) (12, 13), Moderna (12,5%; 3/24) (14, 16, 18), Johnson and Johnson (4,2%; 1/24) (15) and Sinovac (4,2%; 1/24) (21). The majority of cases (66,7%; 16/24) (13–22) were new-onsets of CLs, while the rest of the cases were exacerbation/progression (8,3%; 2/24) (12, 22) and recurrence of CLs (25%; 6/24) (11, 12, 22). Most of the cases (54,2%; 13/24) were recorded after the first immunization dose (11–15, 17, 20–22), followed by 5 cases that developed after the second immunization dose (20,8%; 5/24) (19, 22) and 6 after the third (booster) COVID-19 vaccine dose (25%; 6/24) (16, 18, 22). Five studies provided data regarding the deterioration of lesions following second and subsequent COVID-19 vaccinations (12–14, 17, 21). The median time from vaccination to symptom onset was 10 days (ranging from 2 to 42 days).

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of frequencies in reported SARS-CoV2 vaccines inducing primary cutaneous lymphomas.

Treatment of CLs following COVID-19 vaccination comprised systemic, topical treatment, and combination. Five out of 21 (24%) recorded cases experienced spontaneous remission (11, 13, 18, 22). Overall, 16 patients needed systemic treatment, including methotrexate (MTX), cyclosporin (CsA), brentuximab vedotin (BV), mogamulizumab (MOGA), systemic corticosteroids (SCS), chemotherapy (CHT) and extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP). Local treatment methods included corticosteroids (TCS), radiotherapy (RT), and surgical excision of lesions. The majority of CLs cases achieved complete remission (CR) (14–16, 20, 22) or partial remission (PR) (22) following standard treatment. One case achieved remission with subsequent relapse of disease (13), and one did not respond to therapy (19). In three cases, data concerning treatment outcome were incomplete (12, 17, 21).

Quality assessment of included studies

Most of the studies were assessed as low (11, 14–16, 18, 20, 22) or moderate risk of bias (12, 17, 21), mainly due to incomplete treatment outcome data (Supplementary Tables S1, S2).

Discussion

Since the global introduction of vaccination programs, our understanding of COVID-19 vaccine-related cutaneous reactions is continually expanding. Numerous diverse cutaneous reactions following COVID-19 vaccination have been reported, whereby some of them appear to have an immunological or autoimmunological background. According to the available data, the predominant cutaneous side effect associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccination is a mild and self-limited local injection-site reaction, followed by unspecified cutaneous eruptions, urticaria, angioedema, herpes zoster, pityriasis rosea-like eruptions, pernio, vasculitis, morbilliform eruption and facial dermal filler reactions (39–44). Additionally, rare cutaneous AEs such as the new onset or exacerbation of autoimmune blistering disease, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, eczema, lichen planus, cutaneous lupus erythematosus, as well as the new onset or recurrence of lymphoproliferative disorders, have been reported (11–22, 39–44).

Upon completing the analysis of the 24 CLs after COVID-19 vaccination, several observations can be drawn regarding a possible association between these events. In this systematic review of case reports and case series, we found that CD30 LPDs, namely LyP and PC-ALCL, were the most frequently reported CLs after immunization with a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. However, marked positive expression of CD30 antigen was also noted in MF, pcENKTL, and PCGD-TCL. Most cases occurred after the administration of COVID-19 mRNA-based vaccines, with the majority of CLs being triggered by the first immunization dose and were newly diagnosed. At the same time, the presented cases of CLs showed a tendency to exacerbate following the second and subsequent administrations of COVID-19 vaccine. The disease courses were rather favorable resulting in remission following standard treatment in the majority of cases, including aggressive CTCLs. Moreover, approximately one-quarter of the described patients experienced spontaneous resolution of lesions.

The observed predominance of CD30+ positive cutaneous lymphomas induced by COVID-19 vaccinations raises the question of whether the COVID-19 vaccine might induce the proliferation of CD30+ T-cells in patients with active disease. The CD30 antigen is expressed on a small subset of activated T and B lymphocytes in hematopoietic malignancies, including Hodgkin lymphoma and CTCL (45). Antigenic stimulation by mitogens and viruses has been demonstrated to drive CD30 expression on lymphocytes (46). Moreover, a highly potent adaptive immune response after repeated immunizations with COVID-19 vaccines is suggested to trigger immune exhaustion, leading to the depletion of both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, which exhibit altered or diminished effector functions against both tumor antigens and pathogens (47). It is particularly interesting since exhaustion of activated T lymphocytes is a feature of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells isolated from advanced CTCL skin lesions (48). There have been suggestions that the recurrence of lymphomas is linked to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, possibly due to immune system overstimulation, leading to viral-associated CD30 expression and subsequent exhaustion of T-cells (11, 12). We hypothesize that overproduction and exhaustion of CD4+/CD8+ T cells expressing CD30 may lead to evasion of immune surveillance, thereby contributing to the exacerbation or development of CLs.

Another possible explanation for newly diagnosed and relapsed CLs after COVID-19 vaccinations is that the vaccines might stimulate signaling pathways that drive the pathogenesis. CLs were reported after immunization with both mRNA and vector-based vaccines. However, most of reported cases were induced by lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) formulated messenger RNA-based (LNP-mRNA) COVID-19 vaccines. We suspect that it might be partially related to the LNPs carrier. According to the literature, all components of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, including LNPs, mRNA, and the produced antigen- S protein, may trigger proinflammatory action (49). However, there is robust evidence of the highly inflammatory properties of LNPs, resulting in stronger adjuvant activity compared to other adjuvants (50–52). Mouse models have shown that LNPs induce an inflammatory milieu characterized by neutrophil infiltration, activation of various inflammatory pathways, and production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that might be responsible for reported side effects (50). LNPs were also demonstrated to exacerbate already existing inflammation in mouse models (51). In addition, LNPs and mRNA were shown to activate various Toll-like receptors (TLRs) that trigger signaling pathways involved in immune defense against pathogens (53–55). Interestingly, mRNA COVID-19 vaccine was demonstrated to activate immune cells via TLR3, leading to the secretion of IL-6 and subsequent STAT3 phosphorylation (56). Whereby, IL-6 is a common activator of both NF-KB and STAT3 signaling pathways (57) and has been found to be overexpressed in CTCL (58).

Apart from LNPs and mRNA, the SARS-CoV-2 S1 spike protein induces an excessive inflammatory response. Interestingly, Cheng et al. (59) demonstrated that S1 protein has a unique superantigen-like motif which is highly similar to the bacterial superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin (SE). Therefore, the SARS-CoV-2 S protein is suspected to have potent superantigen properties and to act similarly to bacterial superantigens, thus influencing T cell repertoire (59). This might be significant in terms of lymphomas, as SE are believed to induce disease activity in CLs (60). Moreover, several studies have reported that the SARS-CoV-2 S1 spike protein acts by inducing the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (TNF-alfa, IL-6, IFN gamma) and activating various pathways (ERK1/2 MAPK, NF-kB) (61–63). Therefore, AEs are suspected to be linked to vaccine synthesized SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins, as they may affect host cells in a similar way to COVID-19 infection (64). Taken together, immunization with the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine may trigger overstimulation of the IL-6/STAT3/NFkB loop. This finding is crucial when considering its impact on the CTCL course. Our findings suggest that, although COVID-19 vaccination may elicit CLs, it is not associated with an aggressive clinical course or resistance to treatment. The majority of reported CLs cases showed a very good response to standard treatment, leading to the remission of lesions, even in cases of aggressive CLs.

Notably, new onsets and relapses of CLs have been described following COVID-19 vaccination, but the exact pathogenic mechanism is not fully understood. The predominance of newly diagnosed CLs after vaccination raises the question of whether SARS-CoV-2 vaccine may elicit oncogenesis. There is too little data available to assume, with certainty, that COVID-19 vaccines may contribute to CLs occurrence. However, we suspect that Covid-19 vaccines have the potential to unmask the sub-clinical lymphoproliferative disorders rather than initiate tumorgenesis. It is probable that the newly diagnosed cases had smoldering lymphoproliferation that was controlled by immune surveillance, while vaccination created favorable conditions for the outbreak of the disease. It appears that SARS-CoV-2 vaccines may drive the modification of cytokine profiles in the skin milieu, exacerbate pre-existing inflammation, and activate diverse signaling pathways, potentially leading to either exacerbation or even resolution of the disease.

Nevertheless, it is crucial to emphasize that COVID-19 vaccines are generally safe and highly effective in preventing severe outcomes from COVID-19 infection. Moreover, there is compelling evidence indicating their benefits for patients with solid cancers and those on immunosuppressive treatment (65–67). Notably, two exceptional cases have been reported, demonstrating spontaneous regression of primary cutaneous follicle center cell lymphoma and resolution of organ involvement in PC-ALCL after COVID-19 vaccination (68, 69). These cases were not included in the systematic review as they met exclusion criteria. Such surprising observations suggest potent modulatory properties of COVID-19 vaccination, potentially enhancing the anti-tumor response in predisposed individuals (68).

Limitations

The limitations of this report include the restricted number of studies retrieved from the literature, despite a thorough literature search. This limitation arises from the fact that CLs are rare diseases. However, the findings of this study provide potentially valuable information about rare vaccine-related cutaneous reactions. Moreover, the available data on SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-related CLs primarily originate from case reports and case series, limiting the ability to assess incidence rates of these side effects. Additionally, the collected data were diverse and sometimes incomplete thus precluding meta-analysis, which might constitute the biggest limitation of this study. However, it should be stressed that the presented systematic review is the first to analyze and summarize available literature data on CLs occurring after the administration of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. In addition, due to potential underreporting of side effects such as CLs following immunization with COVID-19 vaccine, clinical trials are still needed to investigate the potential correlation between vaccines and lymphoproliferative disorders.

Conclusion

In this systematic review, we analyzed the cases of CLs occurrence or exacerbation following COVID-19 vaccination. Given the scarce data, establishing a definitive causal relationship between COVID-19 immunization and an increased risk of lymphoma development or exacerbation is challenging. Nonetheless, the striking similarities observed in the reported post-vaccine CLs cases should not be underestimated. The literature review highlights the potent stimulation of immune cells that may result in a flare-up or onset of post-vaccine CLs, particularly in susceptible populations. We believe that the components of COVID-19 vaccines may modulate the microenvironment of CLs leading to the exacerbation or outbreak of sub-clinical cutaneous lymphoproliferation. Further studies are needed to verify and understand the potential relationship between CLs and vaccination. Until then, patients with a history of lymphoproliferative disorders should always be carefully followed-up to monitor the disease course after COVID-19 vaccination.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

BO: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. AZ: Data curation, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. RN: Writing – review & editing. MS-W: Writing – review & editing.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the publication of this article. The study was supported by the Medical University of Gdańsk Project No. ST 01–10024 (0006023).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2024.1325478/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.World Health Organization Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard . (2024). Available at: https://covid19.who.int/ (Accessed January 21, 2024).

- 2.Dolgin E. How COVID unlocked the power of RNA vaccines. Nature. (2021) 589:189–91. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-00019-w, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:2603–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384:403–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Association. COVID-19 advice for the public: Getting vaccinated . (2022). Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines/advice (Accessed April 8, 2022)

- 6.Ling Y, Zhong J, Luo J. Safety and effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. (2021) 93:6486–95. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27203, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim HX, Arip M, Yahaya AA, Jazayeri SD, Poppema S, Poh CL. Immunogenicity and safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in clinical trials. Front Biosci. (2021) 26:1286–304. doi: 10.52586/5024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watad A, De Marco G, Mahajna H, Druyan A, Eltity M, Hijazi N, et al. Immune-mediated disease flares or new-onset disease in 27 subjects following mRNA/DNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Vaccine. (2021) 9:435. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050435, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldman S, Bron D, Tousseyn T, Vierasu I, Dewispelaere L, Heimann P, et al. Rapid progression of Angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma following BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine booster shot: a case report. Front Med. (2021) 8:798095. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.798095, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Çınar OE, Erdoğdu B, Karadeniz M, Ünal S, Malkan ÜY, Göker H, et al. Hematologic malignancies diagnosed in the context of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccination campaign: a report of two cases. Medicina. (2022) 58:1575. doi: 10.3390/medicina58111575, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brumfiel CM, Patel MH, DiCaudo DJ, Rosenthal AC, Pittelkow MR, Mangold AR. Recurrence of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorder following COVID-19 vaccination. Leuk Lymphoma. (2021) 62:2554–5. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2021.1924371, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panou E, Nikolaou V, Marinos L, Kallambou S, Sidiropoulou P, Gerochristou M, et al. Recurrence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma post viral vector COVID-19 vaccination. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2022) 36:e91–3. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17736, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koumaki D, Marinos L, Nikolaou V, Papadakis M, Zografaki K, Lagoudaki E, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) after AZD1222 and BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccines. Int J Dermatol (2022) 61: 900–902. doi: 10.1111/ijd.16296, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li HO, Lipson J. New mycosis fungoides-like lymphomatoid reaction following COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. (2022) 10:2050313X221131859. doi: 10.1177/2050313X221131859, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreher MA, Ahn J, Werbel T, Motaparthi K. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma after COVID-19 vaccination. JAAD Case Rep. (2022) 28:18–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.08.006, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hobayan CG, Chung CG. Indolent cutaneous lymphoma with gamma/delta expression after COVID-19 vaccination. JAAD Case Rep. (2023) 32:74–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.12.001, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zamfir MA, Moraru L, Dobrea C, Scheau AE, Iacob S, Moldovan C, et al. Hematologic malignancies diagnosed in the context of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccination campaign: a report of two cases. Medicina. (2022) 58:874. doi: 10.3390/medicina58070874, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Revenga-Porcel L, Peñate Y, Granados-Pacheco F. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma at the SARS-CoV2 vaccine injection site. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2023) 37:e32–4. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18615, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bresler SC, Menge TD, Tejasvi T, Carty SA, Hristov AC. Two cases of challenging cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates presenting in the context of COVID-19 vaccination: a reactive lymphomatoid papulosis-like eruption and a bona fide lymphoma. J Cutan Pathol. (2023) 50:213–9. doi: 10.1111/cup.14371, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooper MJ, Veon FL, LeWitt TM, Chung C, Choi J, Zhou XA, et al. Cutaneous T-cell–rich lymphoid infiltrates after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. JAMA Dermatol. (2022) 158:1073–6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.2383, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montoya VHG, Cardona LG, Morales S, Ospina JA, Rueda X. SARSCOV-2 vaccine associated with primary cutaneous peripheral T cell lymphoma. Eur J Cancer. (2022) 173:32–3. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(22)00617-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avallone G, Maronese CA, Conforti C, Fava P, Gargiulo L, Marzano AV, et al. Real-world data on primary cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a multicentre experience from tertiary referral hospitals. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2023) 37:451–5. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradford PT, Devesa SS, Anderson WF, Toro JR. Cutaneous lymphoma incidence patterns in the United States: a population-based study of 3884 cases. Blood. (2009) 113:5064–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184168, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dores GM, Anderson WF, Devesa SS. Cutaneous lymphomas reported to the National Cancer Institute's surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program: applying the new WHO-European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification system. J Clin Oncol. (2005) 23:7246–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.0395, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson LD, Hinds GA, Yu JB. Age, race, sex, stage, and incidence of cutaneous lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. (2012) 12:291–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2012.06.010, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, Cerroni L, Berti E, Swerdlow SH, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. (2005) 105:3768–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3502, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willemze R, Cerroni L, Kempf W, Berti E, Facchetti F, Swerdlow SH, et al. The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. (2019) 133:1703–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-11-881268, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dobos G, Pohrt A, Ram-Wolff C, Lebbé C, Bouaziz JD, Battistella M, et al. Epidemiology of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 16, 953 patients. Cancers. (2020) 12:2921. doi: 10.3390/cancers12102921, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dobos G, Miladi M, Michel L, Ram-Wolff C, Battistella M, Bagot M, et al. Recent advances on cutaneous lymphoma epidemiology. Presse Med. (2022) 51:104108. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2022.104108, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Litvinov IV, Shtreis A, Kobayashi K, Glassman S, Tsang M, Woetmann A, et al. Investigating potential exogenous tumor initiating and promoting factors for cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL), a rare skin malignancy. Onco Targets Ther. (2016) 5:e1175799. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1175799, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fanok MH, Sun A, Fogli LK, Narendran V, Eckstein M, Kannan K, et al. Role of dysregulated cytokine Signaling and bacterial triggers in the pathogenesis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Invest Dermatol. (2018) 138:1116–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.10.028, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slodownik D, Moshe S, Sprecher E, Goldberg I. Occupational mycosis fungoides - a case series. Int J Dermatol. (2017) 56:733–7. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13589, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talpur R, Cox KM, Hu M, Geddes ER, Parker MK, Yang BY, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome patients is similar to other cancer patients. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. (2014) 14:518–24. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2014.06.023, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tensen CP, Quint KD, Vermeer MH. Genetic and epigenetic insights into cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. (2021) 139:15–33. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004256, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rendón-Serna N, Correa-Londoño LA, Velásquez-Lopera MM, Bermudez-Muñoz M. Cell signaling in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma microenvironment: promising targets for molecular-specific treatment. Int J Dermatol. (2021) 60:1462–80. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15451, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubio Gonzalez B, Zain J, Rosen ST, Querfeld C. Tumor microenvironment in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Curr Opin Oncol. (2016) 28:88–96. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000243, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, et al. Available from chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Eds. Aromataris E., Munn Z., Adelaide (AU): Joanna Briggs Institute; (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Avallone G, Quaglino P, Cavallo F, Roccuzzo G, Ribero S, Zalaudek I, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-related cutaneous manifestations: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. (2022) 61:1187–204. doi: 10.1111/ijd.16063, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gambichler T, Boms S, Susok L, Dickel H, Finis C, Abu Rached N, et al. Cutaneous findings following COVID-19 vaccination: review of world literature and own experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2022) 36:172–80. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17744, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Washrawirul C, Triwatcharikorn J, Phannajit J, Ullman M, Susantitaphong P, Rerknimitr P. Global prevalence and clinical manifestations of cutaneous adverse reactions following COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2022) 36:1947–68. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18294, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Avallone G, Cavallo F, Astrua C, Caldarola G, Conforti C, De Simone C, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions following SARS-CoV-2 vaccine booster dose: a real-life multicentre experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2022) 36:e876–9. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18386, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martora F, Villani A, Battista T, Fabbrocini G, Potestio L. COVID-19 vaccination and inflammatory skin diseases. J Cosmet Dermatol. (2023) 22:32–3. doi: 10.1111/jocd.15414, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martora F, Villani A, Marasca C, Fabbrocini G, Potestio L. Skin reaction after SARS-CoV-2 vaccines reply to 'cutaneous adverse reactions following SARS-CoV-2 vaccine booster dose: a real-life multicentre experience'. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2023) 37:e43–4. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18531, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Weyden CA, Pileri SA, Feldman AL, Whisstock J, Prince HM. Understanding CD30 biology and therapeutic targeting: a historical perspective providing insight into future directions. Blood Cancer J. (2017) 7:e603. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2017.85, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horie R, Watanabe T. CD30: expression and function in health and disease. Semin Immunol. (1998) 10:457–70. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0156, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benitez Fuentes JD, Mohamed Mohamed K, de Luna Aguilar A, Jiménez García C, Guevara-Hoyer K, Fernandez-Arquero M, et al. Evidence of exhausted lymphocytes after the third anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine dose in cancer patients. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:975980. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.975980, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Querfeld C, Leung S, Myskowski PL, Curran SA, Goldman DA, Heller G, et al. Primary T cells from cutaneous T-cell lymphoma skin explants display an exhausted immune checkpoint profile. Cancer Immunol Res. (2018) 6:900–9. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0270, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trougakos IP, Terpos E, Alexopoulos H, Politou M, Paraskevis D, Scorilas A, et al. Adverse effects of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: the spike hypothesis. Trends Mol Med. (2022) 28:542–54. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2022.04.007, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ndeupen S, Qin Z, Jacobsen S, Bouteau A, Estanbouli H, Igyártó BZ. The mRNA-LNP platform's lipid nanoparticle component used in preclinical vaccine studies is highly inflammatory. iScience. (2021) 24:103479. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103479, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parhiz H, Brenner JS, Patel PN, Papp TE, Shahnawaz H, Li Q, et al. Added to pre-existing inflammation, mRNA-lipid nanoparticles induce inflammation exacerbation (IE). J Control Release. (2022) 344:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.12.027, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alameh MG, Tombácz I, Bettini E, Lederer K, Sittplangkoon C, Wilmore JR, et al. Lipid nanoparticles enhance the efficacy of mRNA and protein subunit vaccines by inducing robust T follicular helper cell and humoral responses. Immunity. (2022) 55:1136–8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2022.05.007, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verbeke R, Lentacker I, De Smedt SC, Dewitte H. Three decades of messenger RNA vaccine development. Nano Today. (2019) 28:100766. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2019.100766, PMID: 37884526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lonez C, Vandenbranden M, Ruysschaert JM. Cationic lipids activate intracellular signaling pathways. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. (2012) 64:1749–58. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.05.009, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karikó K, Buckstein M, Ni H, Weissman D. Suppression of RNA recognition by toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity. (2005) 23:165–75. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hirsiger JR, Tzankov A, Alborelli I, Recher M, Daikeler T, Parmentier S, et al. Case report: mRNA vaccination-mediated STAT3 overactivation with agranulocytosis and clonal T-LGL expansion. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1087502. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1087502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hirano T. IL-6 in inflammation, autoimmunity and cancer. Int Immunol. (2021) 33:127–48. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxaa078, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lawlor F, Smith NP, Camp RD, Bacon KB, Black AK, Greaves MW, et al. Skin exudate levels of interleukin 6, interleukin 1 and other cytokines in mycosis fungoides. Br J Dermatol. (1990) 123:297–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb06288.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheng MH, Zhang S, Porritt RA, Noval Rivas M, Paschold L, Willscher E, et al. Superantigenic character of an insert unique to SARS-CoV-2 spike supported by skewed TCR repertoire in patients with hyperinflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2020) 117:25254–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010722117, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Willerslev-Olsen A, Krejsgaard T, Lindahl LM, Bonefeld CM, Wasik MA, Koralov SB, et al. Bacterial toxins fuel disease progression in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Toxins. (2013) 5:1402–21. doi: 10.3390/toxins5081402, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Forsyth CB, Zhang L, Bhushan A, Swanson B, Zhang L, Mamede JI, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 S1 spike protein promotes MAPK and NF-kB activation in human lung cells and inflammatory cytokine production in human lung and intestinal epithelial cells. Microorganisms. (2022) 10:1996. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10101996, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khan S, Shafiei MS, Longoria C, Schoggins JW, Savani RC, Zaki H. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces inflammation via TLR2-dependent activation of the NF-κB pathway. eLife. (2021) 10:e68563. doi: 10.7554/eLife.68563, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Suzuki YJ, Nikolaienko SI, Dibrova VA, Dibrova YV, Vasylyk VM, Novikov MY, et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-mediated cell signaling in lung vascular cells. Vasc Pharmacol. (2021) 137:106823. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2020.106823, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suzuki YJ, Gychka SG. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein elicits cell Signaling in human host cells: implications for possible consequences of COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccines. (2021) 9:36. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010036, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cai SW, Chen JY, Wan R, Pan DJ, Yang WL, Zhou RG. Efficacy and safety profile of two-dose SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in cancer patients: an observational study in China. World J Clin Cases. (2022) 10:11411–8. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11411, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Almasri M, Bshesh K, Khan W, Mushannen M, Salameh MA, Shafiq A, et al. Cancer patients and the COVID-19 vaccines: considerations and challenges. Cancers. (2022) 14:5630. doi: 10.3390/cancers14225630, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shulman RM, Weinberg DS, Ross EA, Ruth K, Rall GF, Olszanski AJ, et al. Adverse events reported by patients with cancer after administration of a 2-dose mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. (2022) 20:160–6. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.7113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gambichler T, Boms S, Hessam S, Tischoff I, Tannapfel A, Lüttringhaus T, et al. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma with marked spontaneous regression of organ manifestation after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Br J Dermatol. (2021) 185:1259–62. doi: 10.1111/bjd.20630, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aouali S, Benkaraache M, Almheirat Y, Zizi N, Dikhaye S. Complete remission of primary cutaneous follicle Centre cell lymphoma associated with COVID-19 vaccine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2022) 36:e676–8. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.