Abstract

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV- 6), which belongs to the betaherpesvirus subfamily and infects mainly T cells in vitro, causes acute and latent infections. HHV- 6 contains two genes (U12 and U51) that encode putative homologs of cellular G-protein-coupled receptors (GCR), while three other betaherpesviruses, human cytomegalovirus, murine cytomegalovirus, and human herpesvirus 7, have three, one, and two GCR-homologous genes, respectively. The U12 gene is expressed late in infection from a spliced mRNA. The U12 gene was cloned, and the protein was expressed in cells and analyzed for its biological characteristics. U12 functionally encoded a calcium-mobilizing receptor for β-chemokines such as regulated upon activation, normal T expressed and secreted (RANTES), macrophage inflammatory proteins 1α and 1β (MIP-1α and MIP-1β) and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 but not for the α-chemokine interleukin-8, suggesting that the chemokine selectivity of the U12 product was distinct from that of the known mammalian chemokine receptors. These findings suggested that the product of U12 may play an important role in the pathogenesis of HHV- 6 through transmembrane signaling by binding with β-chemokines.

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV- 6) was first isolated in 1986 from the peripheral blood of patients with lymphoproliferative disorders (50). The distinct nature of HHV- 6 from that of other human herpesviruses was confirmed by molecular and immunological analyses (30). The virus replicates predominantly in CD4+ lymphocytes in vitro and in vivo (36, 53) and may establish latent infection in cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage (33). Infection with this virus is the cause of exanthem subitum, which is a common illness of infancy (58) but has not yet been clearly linked to other diseases which may occur during reactivation of HHV- 6 later in life or in immunosuppressed individuals. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the genome has demonstrated that HHV- 6 is more closely related to the other betaherpesviruses human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and human herpesvirus 7 (HHV- 7) than to the neurotropic alphaherpesviruses such as herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus or to the lymphotropic gammaherpesviruses such as Epstein-Barr virus (20, 34, 38). Furthermore, two variants of HHV- 6 have been identified based on differences in epidemiology, in vitro growth properties, antigenic differences, restriction endonuclease profiles, and nucleotide sequence (1, 4, 5, 12, 24, 51, 56, 57). Consequently, a nomenclature has been adopted designating viruses HHV- 6A (variant A) and HHV- 6B (variant B) (1).

Gompels et al. (25) have completed DNA sequence analysis for HHV- 6A strain U1102, and we have also sequenced the entire DNA of HHV- 6B strain HST (unpublished data). DNA sequence alignment has identified two candidates for G-protein-coupled receptors (GCR), open reading frames (ORFs) U12 and U51, within the HHV- 6 genome (25). GCR homologs have been identified in other betaherpesviruses, HCMV and HHV- 7 (13, 42), as well as in the gammaherpesviruses herpesvirus saimiri (HVS) (43) and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV or HHV- 8) (11). Recently, ORF74 of KSHV has been reported to encode a constitutively active GCR linked to cell proliferation (3, 11). The deduced amino acid sequences of ORFs U12 and U51 of HHV- 6, ORFs U12 and U51 of HHV- 7, ORFs US27, US28, and UL33 of HCMV, ORF ECRF3 of HVS, and ORF74 of KSHV are most similar to those of mammalian leukocyte chemokine receptors (11, 13, 42, 43). Furthermore, it was demonstrated that US28 and ECRF3 are functional β-chemokine and α-chemokine receptors, respectively (2, 23).

It has been shown by Ahuja and Murphy (2) that ORF ECRF3 of HVS encodes a promiscuous calcium-mobilizing receptor for the α-chemokines interleukin-8 (IL-8), Groα (growth- related gene product), and neutrophil-activating protein 2. The β-chemokines do not activate the ECRF3 product. The same group has demonstrated that the HCMV US28 product functions as a β-chemokine receptor linked to a calcium-mobilizing signal transduction pathway for macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α), MIP-1β, RANTES (regulated upon activation, normal T expressed and secreted), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) but not for IL-8 and gamma interferon-inducible protein-10 and (γIP-10) (23). We report here that the product encoded by ORF U12 in the genome of HHV- 6 strain HST, when produced in stable transfected K562 human erythroleukemia cells, is a promiscuous high-affinity chemokine receptor that can potentially be linked to a calcium-mobilizing signal transduction pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMCs) were separated on a Ficoll-Conray gradient and stimulated for 2 or 3 days in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 5 μg of phytohemagglutinin per ml. HHV- 6 strain HST, which was isolated from a patient with exanthen subitum (58) and belongs to the HHV- 6B subgroup (57), was grown in activated CBMCs. To prepare virus stocks, virus was propagated in stimulated CBMCs. When more than 80% of the cells showed cytopathic effect, the culture of infected cells was frozen and thawed twice, and after centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was stored at −80°C as a cell-free virus stock. After being washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), stimulated CBMCs (107 cells) were suspended in 1 ml of virus solution with 107 50% tissue culture infective doses per ml and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 40 min at 37°C for adsorption. The cells were then cultured for various periods in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS. For examination of the transcripts of the HHV- 6 genome in the presence of inhibitors of protein and DNA synthesis, cycloheximide (CHX) and phosphonoformic acid (PFA) were used for protein synthesis inhibition, and DNA synthesis inhibition, respectively. Both were dissolved in water, sterilized by filtration, and used at 50 and 200 μg per ml, respectively. Stimulated CBMCs were infected with strain HST as described above, except that CHX or PFA was added from the initiation of infection for 24 h. Nonadherent K562 human erythroleukemia cells were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS (complete medium).

Cloning of U12, CCR-1, and CXCR-1.

From 106 strain HST-infected CBMCs 2 days after infection, DNA was extracted in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer consisting of 0.001% Triton X-100, 0.0001% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mg of protease K (pH 8.0) per ml at 65°C overnight. The U12 ORF was amplified from 2 μl of the lysate or cDNA as described below by PCR with buffer containing EX Taq (Takara Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan) buffer, 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and a pair of PCR primers, 01GCR-Met-Kpn (5′-AAAGGTACCAAGCGACGAGATGGACACT) and 01GCR-Ter-Bam (5′-AAGGATCCTTAAGGGGGTTCGTTTTCATC), which were, respectively, sense, 28 bases upstream from the start codon with a KpnI recognition sequence appended at the 5′ end, and antisense, 29 bases downstream from the stop codon with a BamHI recognition sequence appended at the 5′ end. The PCR conditions were as follows: 25 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min and one final extension at 72°C for 10 min in a TP480 PCR thermal cycler (Takara Shuzo). The PCR product was cloned into pCR II (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) and sequenced completely. Sequencing was performed with a SequiTher Long-Read cycle sequencing kit and a 4000L DNA sequencer (Li-Cor, Inc., Lincoln, Neb.). Cloning of CCR-1 (22) and CXCR-1 (40) was also carried out as described above, except that DNA extracted from HL-60 and PCR amplimers of CCR-1 and CXCR-1 were CCR1-Met-Nhe (5′-GGCTTGAGCTAGCGAGAAGCCGGGATGGAAACT), CCR1-Ter-Xho (5′-TTTACTCGAGTCAGAACCCACAGAGAGTCATGCTC), CXCR1-Met-Kpn (5′-GGTACCATTGCTGCTGAAACTGAAGAGGACATG), and CXCR1- Ter-Kpn (5′-CTCGAGTCAGAGGTTGGAAGAGACATTGAC), respectively.

To express the N-terminal extracellular domain of the U12 protein, an expression plasmid was constructed by using bacterial expression vector pGEX-3X (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). In this plasmid, the segment of the U12 gene was fused to the glutathione S-transferase gene. Viral DNA from HHV- 6B strain HST was used as a template in PCR. PCR was performed as described above with EX Taq DNA polymerase and an appropriate a pair of primers, 01GCR-GST-N1 (5′-GCGGGATCCTGGACACTGTCATTGAG) and 01GCR-GST- N2 (5′-TGGAATTCGTGCTGTCTTTAGCGT), which were sense with a BamHI recognition sequence appended at the 5′ end and antisense with an EcoRI recognition sequence appended at 5′ end, respectively. The PCR product was inserted into pGEX-3X to create plasmid pGEU12-N (residues 2-32).

Antibodies and Western blot analysis.

For Western blot analysis, anti-U12-N antibodies in rabbits were raised against the fusion protein, purified by glutathione-Sepharose 4B column chromatography, from pGEU12-N. Two rabbits were first immunized with 250 μg each of the purified fusion protein in Freund’s complete adjuvant and then given injections of 200 μg each of antigen in Freund’s incomplete adjuvant 14 and 28 days after the first injection. The rabbits were bled 7 days after the last injection, and anti-U12-N antibodies in the sera were checked by indirect immunofluorescence assay with CBMCs infected with strain HST. HHV- 6- and mock-infected CBMCs were air dried on glass slides and fixed overnight in cold acetone. Sera were diluted with dilution buffer (PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin, 0.2% Tween 20, and 0.05% NaN3) and poured on slides for a 20-min incubation at room temperature. After washing the slides for 10 min with PBS, fluorescein-conjugated goat antibodies to rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Tago Immunologicals) were placed on the slides and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. Anti-U12-N IgGs were purified with the ImmunoPure (A) IgG purification kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). The concentration of the purified IgGs was 1.6 mg/ml.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was done essentially as described previously (45). Proteins from 5 × 105 HST-infected cells were separated in 10% polyacrylamide gels at various times after virus infection. Western blot analysis was done as described by Towbin et al. (55), with a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) and rabbit IgG anti-U12 (1:100) prepared in 5% skim milk–PBS (Western blocking buffer), and detected with the ProtoBlot nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate color development system (Promega, Madison, Wis.).

Creation of stable transfected cell lines.

Genomic U12 and ORFs for U12, CCR-1, and CXCR-1 were recloned from the plasmids described above between the KpnI and BamHI sites of the hygromycin-selectable, stable episomal vector pCEP4 (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) and designated pCEU12g, pCEU12c, pCECCR-1, and pCECXCR-1, respectively. K562 cells (107 cells) in the log phase were electroporated in the presence of 20 ng of plasmid DNA with a Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Electroporation conditions were 300-μl volume, 250 V, and 960 μF, with a 0.4-cm-gap electroporation cuvette. Transformed cells were cultured in complete medium, and 48 h later the cells were seeded at 105 cells/ml in complete medium containing 250 μg of hygromycin B per ml and selected for 5 days. Subsequently, the cells were maintained in complete medium with 150 μg of hygromycin B per ml.

Ligand binding analysis.

In triplicate, 106 cells were incubated with 0.1 nM 125I-labeled RANTES (specific activity, 2,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham) and different concentrations of unlabeled recombinant human chemokines (Immugenex Corp., Los Angeles, Calif.) in binding medium (RPMI 1640 with 1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml and 25 mM HEPES [pH 7.4]) in a total volume of 200 μl. After incubation for 2 h at 4°C, the cells were filtered in the MultiScreen assay system (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). The filters were washed five times with PBS and then completely dried with a heat lamp. After the filters were punched out from the sample 96-well filtration plate into sample containers, the radioactivities were measured using an Aloka γ-ray counter. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 1 μM unlabeled ligand. The rate of competition for binding by unlabeled chemokines was calculated as follows: percent competition for binding = (1 − [cpm obtained in the presence of unlabeled ligand/cpm obtained in the absence of unlabeled ligand]) × 100%.

Intracellular [Ca2+] measurements.

Cells were washed twice in HEPES-buffered Krebs solution, which consisted of 124 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.24 mM KH2PO4, 1.3 mM MgSO4, 2.4 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) (HBKS). Then 107 cells were incubated for 30 min at 37°C in the dark in 1 ml of HBKS containing 5 μM Indo-1 AM (Dojin Chemical Co.). The cells were subsequently washed twice with HBKS and resuspended at 2.5 × 106 cells/ml. A 1-ml volume of the cell suspension was placed in a continuously stirred cuvette at 37°C in a CAF-110 fluorometer (Jasco). Fluorescence was monitored at an excitation wavelength of 355 nm and emission wavelengths of 405 and 485 nm; the data are presented as the relative ratio of fluorescein excited at 405 and 485 nm. Data were collected every 10 ms.

RNA analysis.

Virus-infected cells or transfected cultured cells were pelleted and suspended in 4 M guanidium isothiocyanate containing 0.5% sodium N-lauroylsarcosine and 0.1 M 2-mercaptoethanol. Total RNA was extracted by the guanidium isothiocyanate method (14). For Northern blotting, total RNA or mRNA purified with Oligotex-dT (super) (JSR, Tokyo, Japan) was fractionated by size on a denaturing agarose gel, transferred to a solid support, and hybridized to 32P-labeled ORF probes of U12 as described previously by Murphy and Tiffany (40). For reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR), reverse transcription reactions for cDNA synthesis of the parts of HHV- 6 immediate-early 1 (IE-1), DNA polymerase (Pol), glycoprotein H (gH), elongation factor 1α (EF), and U12 were performed in a 20-μl solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 3 mM dithiothreitol and carried out at 42°C for 30 min with 20 U of RAV2 RT (Takara Shuzo), 1 μg of cellular RNA, and 0.4 μM oligo(dT). PCR was performed as described above with EX Taq DNA polymerase and appropriate pairs of primers as follows: for IE-1, Pol, gH, EF, and U12, IE03-F340 (5′-CAGAATTCATGGAAGTACAATCTCCTACTG), and IE03- MR (5′-CACTGCAGTTAATGACTTTTGACAGGAGTTGC), 06POL-R1 (5′-CGAACAGTTTTGCATCTCCGC), and 06-PARC3 (5′-GTTTGTATCCGAGCATTATG), gHF4 (5′-CCAGTCCAAGTCAGATGCGC), and gHR5 (5′-AATAGGGTTTGGATTCCTAGG), CEF1A (5′-GCTCCAGCATGTTGTCACCATTC) and EF1A (5′-GGTGAATTTGAAGCTGGTATCTC), and 01GCR-C (5′-CCATGGATCCCCAAAAGACTATGTAGT) and 01GCR-Ter-Bam, respectively.

Homology and ORF analysis.

The DNA sequences were analyzed for the presence of ORFs and for their translation products with the MacDNASIS (Hitachi Software Engineering Co., Ltd., Yokohama, Japan). The FASTA program was used to search the HHV- 6 U12 sequences for homologous protein sequences. Protein sequence databases searched with this program include the National Biomedical Research Foundation PIR and SWISS-PROT. The sequences were aligned to homologous genes with the Higgins et al. program in MacDNASIS (29).

RESULTS

Molecular cloning and cDNA analysis.

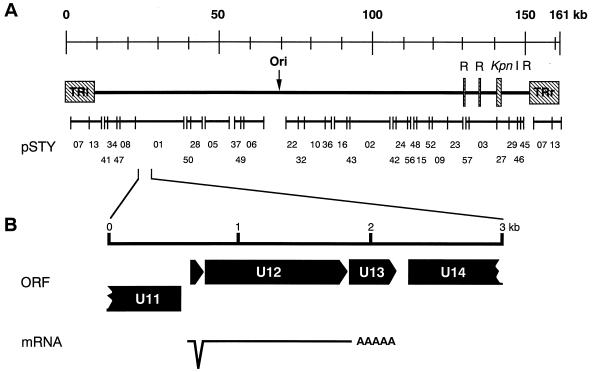

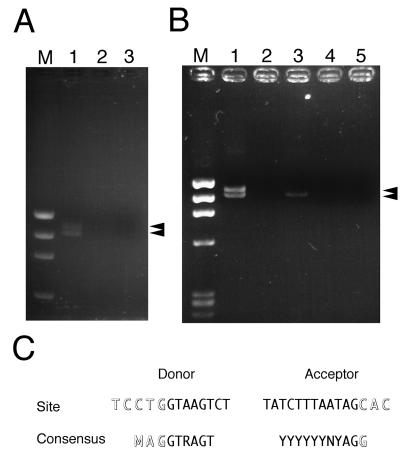

Inspection of the complete nucleotide sequence of HHV- 6 strain HST (29a), revealed that ORF U12 is located 22 kb from the left end (Fig. 1). We were particularly interested in the 915-bp ORF U12, because the deduced amino acid sequence of the original predicted ORF U12 had a high degree of similarity to chemokine receptors including GCR. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the original predicted ORF U12 was shorter than those of HCMV US28 and CCR-1 when the original predicted ORF U12 and the others were aligned. Primers 01GCR-Met-Kpn and 01GCR-Ter-Bam were designed to include a methionine site in a small ORF upstream of the original predicted U12 and the terminal site in the U12, respectively. With these primers, the U12 coding region was amplified from cDNA which was synthesized with oligo(dT) and from total RNA purified from HHV- 6-infected cells. Two bands, of 1,165 and 1,088 bp and of approximately equal intensity, were obtained (Fig. 2A, lane 1) and cloned into pCRII. These bands were not observed in the gel containing total RNA purified from HHV- 6-infected cells without RT treatment (lane 2) or in the gel containing total RNA purified from mock-infected cells with RT treatment (lane 3). These results suggested that virus-infected cells contained at least two species of mRNAs for U12 in approximately equal amounts. The nucleotide sequencing data of 5 clones for each band showed that 1,165- and 1,088-bp bands were amplified from unspliced and spliced mRNA, respectively. From the positions of consensus splice donor and acceptor sites, it appears that the shorter mRNA was generated from two exons after splicing out of a 77-nucleotide intron (Fig. 1 and 2C). The resultant 1,059 nucleotides of a coding region could be translated into a polypeptide encoding 353 amino acids of a GCR homolog (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

General organization of an HHV- 6 GCR-homologous gene, and structure of the HHV- 6 GCR transcript. (A) Location of a GCR-homologous gene in the HHV- 6 (HST) genome. (B) Direction of ORFs and splicing site of U12.

FIG. 2.

RT-PCR assay of U12 mRNA in the HST-infected cells and the U12- transfected cells. (A) U12 ORF was amplified from cDNA synthesized with total RNA purified from HST- or mock-infected CBMCs with a pair of primers, 01GCR- Met-Kpn and 01GCR-Ter-Bam, as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes: 1, HST-infected CBMCs; 2, HST-infected CBMCs without RT treatment; 3, mock-infected CBMCs; M, φX174 × HaeIII. (B) U12 ORF was amplified from cDNA synthesized with total RNA purified from U12-transfected K562 cells. Lanes: 1, genomic U12-transfected cells; 2, genomic U12-transfected cells without RT treatment; 3, U12 cDNA-transfected cells; 4, U12 cDNA-transfected cells without RT treatment; 5, pCEP4-transfected cells; M, φX174 × HaeIII. (C) Comparison of amino acid sequences between U12 splice sites and consensus donor-acceptor sites as reported by Green (26). Outlined letters are exon nucleotides, and normal letters are intron nucleotides.

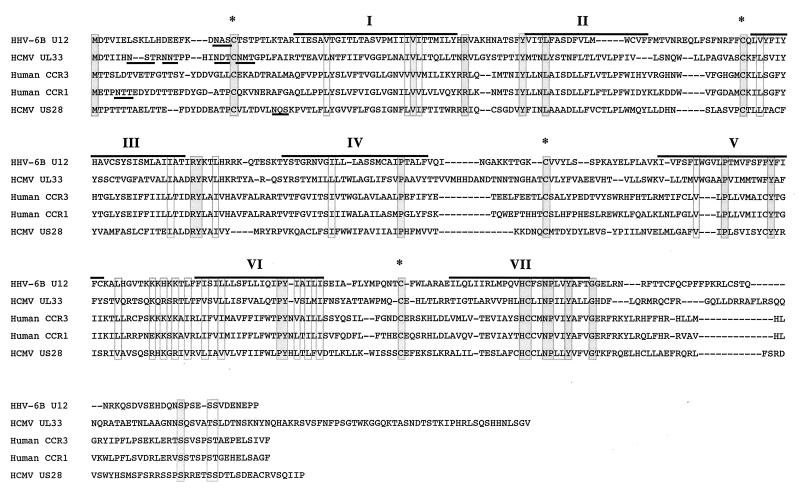

Since, as described above, there are counterparts of this gene in the HHV- 7 and HCMV genomes, the amino acid sequence was compared with those of the GCR homologs of these viruses as well as of cellular GCR homologs. U12 had highest homology to the U12 of HHV- 6A, followed by HHV- 7 U12 and HCMV UL33 (Table 1). U12 also exhibited homology to multiple mammalian GCRs; the highest was to CCR-3, but a lesser degree was found to CCR-1 and CCR-5 (Table 1). The lowest degree of homology was to HCMV US28 (14.0%).

TABLE 1.

Amino acid identity between the U12 GCR homolog of HHV- 6B and other chemokine receptors

| Gene homolog | % Identity | Scorea |

|---|---|---|

| HHV- 6A U12 | 88.4 | 1,638 |

| HHV- 7 U12 | 48.1 | 900 |

| HCMV UL33 | 23.9 | 468 |

| Human CCR-3 | 22.4 | 244 |

| Human CCR-1 | 22.1 | 236 |

| Human CCR-5 | 19.2 | 228 |

| HCMV US28 | 14.0 | 50 |

Optimized FASTA score.

Sequence alignment of the U12 product with human CCR-1, CCR-3, and HCMV UL33 and US28 products suggests that U12 contains seven transmembrane regions, four extracellular domains, and four cytoplasmic domains (Fig. 3). The N-terminal extracellular domain of the U12 product contains a potential N-glycosylation site, similar to most known GCRs. All the extracellular domains of the U12 product contain four highly conserved cysteine residues which are essential to the structure of GCRs (18, 31).

FIG. 3.

Sequence alignment of the U12 cDNA product with the HCMV US28 and UL33 products and human CCR-1 and CCR-3. Dashes indicate gaps that were inserted to optimize the alignment. The locations of predicted membrane-spanning segments are denoted by I to VII, and overlines indicate their amino acid sequences. Underlines designated predicted sites for N-linked glycosylation. Asterisks indicate the positions where the five sequences have the conserved cysteine residues in the predicted cytoplasmic domains. Identical and homologous amino acids of the five sequences are enclosed in dark and light gray boxes, respectively.

RT-PCR analysis for U12 expression in HHV- 6-infected cells.

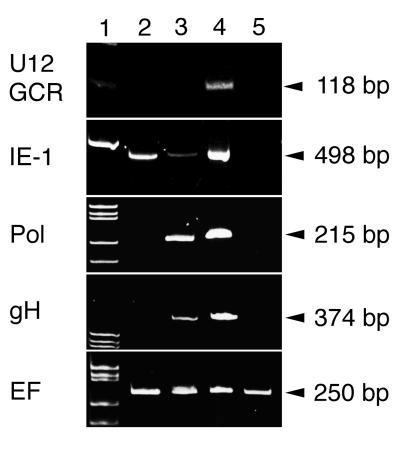

We examined the transcription of U12 in the presence of an inhibitor of protein and DNA synthesis. RNA was purified from CBMCs infected with strain HST in the presence of CHX and PFA as described in Materials and Methods. Specific RNAs were amplified by RT-PCR with primers for U12, IE-1, Pol, gH, and EF. The products were separated in a 10% polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 4). The EF bands, which were amplified from cellular control RNA, were displayed at approximately equal intensities in all lanes. No products were amplified from mRNA of mock-infected cells with the primers related to the HHV- 6 genome (Fig. 4, lane 5). In the presence of CHX, only the IE-1 band (498 bp) was detected by RT-PCR (lane 2). In the presence of PFA, the IE-1, Pol (215 bp), and gH (374 bp) bands appeared but the U12 band did not (lane 3). In untreated samples, all the bands were detected (lane 4). These results indicate that U12 is expressed as a late gene.

FIG. 4.

RT-PCR assay of the transcripts in the HST-infected cells treated with CHX and PFA. Total RNAs purified from mock-infected (lane 5) and HST-infected (lanes 2 to 4) CBMCs, which were treated with CHX for 24 h (lane 2) or PFA for 24 h (lane 3) or left untreated (lane 4), were used for RT-PCR of the parts of HHV- 6 IE-1, Pol, gH, EF, and U12, as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1 contains molecular size markers.

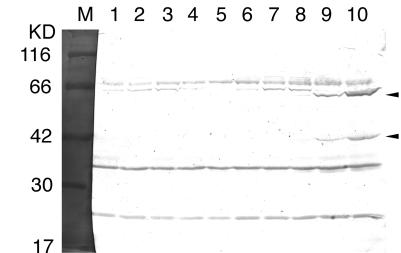

Western blot analysis for U12 expression in HHV- 6-infected cells.

CBMCs were infected with or without HHV- 6 strain HST, harvested in 1× SDS-PAGE sample buffer at various times after infection, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot assays (Fig. 5). After a 24-h infection, HST-infected cells expressed 42-kDa proteins (Fig. 5, lanes 8 to 10), which were reactive with the anti-U12-N IgGs. These bands were 2 kDa bigger than the computer-predicted molecular mass of the protein encoded by U12, which may associate with N-glycosylation of the N-terminal extracellular domain of the U12. The larger immunoreactive materials (62-kDa proteins [lanes 8 to 10]) are most probably dimers of U12 that did not dissociate during SDS-PAGE (37, 52). No similar protein was detected in mock-infected cells (lanes 1 to 5) or in the HST-infected cells between 0 and 12 h after infection (lanes 6 and 7). As shown by Takeda et al. (54), the IE-1 protein and glycoprotein B of HHV- 6 were first detectable at 4 and 24 h after infection, respectively (data not shown). These data suggested that U12 was the late gene.

FIG. 5.

Expression of U12 in HHV- 6B-infected cells at various times after infection. Western blot analysis shows proteins produced by CBMCs that were infected with the HST-infected cells (lanes 6 to 10) or mock-infected cells (lanes 1 to 5). Lanes: 1 and 6, mock- and HST-infected cells at 0 h; 2 and 7, mock- and HST-infected cells at 12 h; 3 and 8, mock- and HST-infected cells at 24 h; 4 and 9, mock- and HST-infected cells at 48 h; 5 and 10, mock- and HST-infected cells at 72 h; M, molecular size markers.

RNA analysis of U12-transfected cells.

When the coding region was amplified by PCR with the primers in Fig. 2A and total RNA purified from pCEU12g-transfected cells, two bands of approximately equal intensities appeared in an agarose gel (Fig. 2B, lane 1). These bands were the same sizes as those of amplified products from the RNA of HHV- 6-infected cells. Amplification of the U12 coding region by using cDNA synthesized with total RNA from pCEU12c-transfected cells resulted in one band (lane 3), which is the same size as the lower band of the PCR products from the genomic DNA-transfected cells. These bands were not observed in samples of total RNA purified from pCEU12g- or pCEU12c-transfected cells without RT treatment (lanes 2 and 4). No band was detected in a sample of total RNA from pCEP4 transfected cells with RT treatment (lane 5).

Similar results were obtained by Northern blot analysis, as shown in Fig. 2B. Northern blot analysis showed that the genomic U12-transfected K562 cells expressed large amounts of U12 mRNA of the expected sizes of 1.7 to 1.9 kb and the U12 cDNA-transfected cells expressed only the 1.7-kb mRNA, the expected size of the spliced RNA (data not shown). When Northern analysis of RNA from HHV- 6-infected cells was performed, U12 mRNA could not be detected (data not shown).

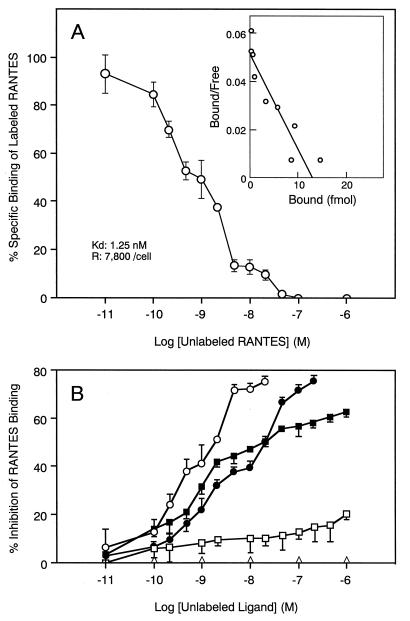

Binding of RANTES to the U12 GCR.

To test whether the U12 product functions as a chemokine receptor, we examined the binding activity of the U12 product with various chemokines. Since human T cells or cell lines have chemokine receptors, the K562 cell line, which does not express a chemokine receptor (23), was selected for these studies. To test the specific binding to RANTES, we performed a binding competition assay with unlabeled chemokines (Fig. 6). The U12-transfected K562 cells expressed specific binding sites for 125I-RANTES, whereas untransfected K562 cells did not. Figure 6A shows a typical binding profile of 125I-RANTES to U12-transfected cells with an estimated Kd of 1.3 nM. The binding of 125I- RANTES was efficiently displaced by RANTES itself and was blocked with similar efficiency by the unlabeled β-chemokines MCP-1 and MIP-1β (Fig. 6B). The β-chemokine MIP-1α only partially displaced 125I-RANTES binding, but the α-chemokine IL-8 did not compete for 125I-RANTES binding (Fig. 6B). MIP-1β and MCP-1 were less potent competitors for binding of radiolabeled RANTES to the U12 transfectant, with 50% inhibitory concentrations about 15 times higher than that of RANTES itself (20 and 1.3 nM, respectively). Since MIP-1α had a very limited effect, the 50% inhibitory concentration value for MIP-1α could not be determined. Scatchard analysis also revealed the number of binding sites per cell, which was about 7,800 for RANTES tested.

FIG. 6.

Binding of 125I-RANTES to K562 cells stably transfected with pCEU12c. (A) Binding isotherm of 125I-RANTES. (B) Displacement of RANTES binding to U12-transfected K562 cells by unlabeled chemokines. Each point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean for triplicate determinations. The average total binding was 6,300 cpm. Nonspecific binding was 600 cpm. The binding parameters for competing unlabeled RANTES are shown at the lower left of panel A. Untransfected K562 cells did not specifically bind the radioligand. ○, RANTES; •, MCP-1; □, MIP-1α; ▪, MIP-1β; ▵, IL-8.

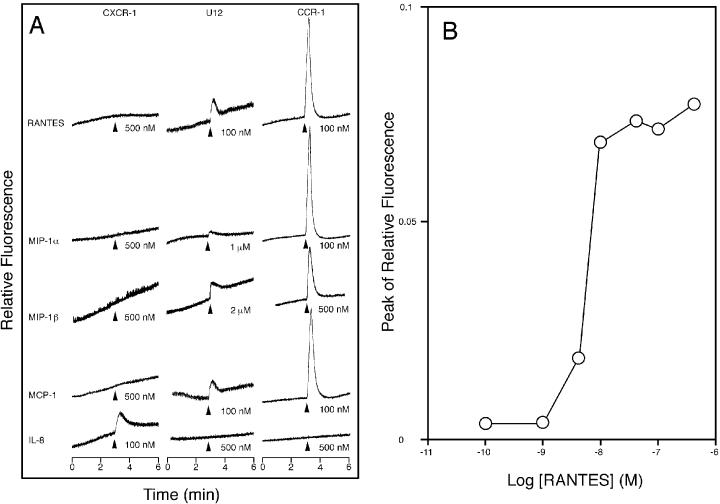

Signaling through the U12 GCR in response to CC chemokines.

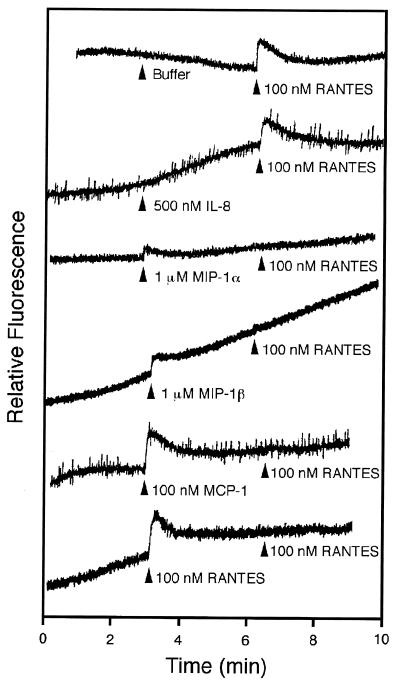

To test whether the U12 product is capable of signal transduction, intracellular Ca2+ levels were monitored by measuring the relative fluorescence of Indo-1-loaded cells stimulated with RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MCP-1, and IL-8 (Fig. 7A). Untransfected and pCEP4-transfected K562 cells did not respond to any of the chemokines tested (data not shown). U12-transfected K562 cells responded to all the β-chemokines tested (RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and MCP-1) but did not respond to the α-chemokine (IL-8). Treatment of U12 transfectants with RANTES induced transient elevations of intracellular Ca2+ level, with a 50% effective concentration of about 7 nM, a value similar to the Kd (Fig. 7B). MCP-1 and RANTES showed similar activities, while MIP-1α and MIP-1β were less effective agonists than RANTES, having a threshold for calcium mobilization of more than 100 nM. Furthermore, when the U12 transfectants were sequentially stimulated with the chemokines, all the β-chemokines tested could attenuate or abolish the normal response to a subsequent stimulus with 100 nM RANTES whereas IL-8 could not (Fig. 8). When the transfectants were stimulated with 100 nM RANTES, the normal responses to a subsequent stimulus with each β-chemokine tested completely disappeared (data not shown). These results suggest that the binding affinities of β-chemokines do not reflect their signaling capabilities for calcium mobilization.

FIG. 7.

Transmembrane signaling by the product of HHV- 6 U12. (A) Kinetics. The intracellular Ca2+ concentration was monitored by measuring the relative fluorescence of Indo-1-loaded K562 cells stably transfected with pCECXCR-1, pCEU12c, and pCECCR-1, indicated at the top of each column of tracings. The cells were stimulated, at the time indicated by the arrowheads, with the chemokine indicated on the left of each row of tracings and at the concentration indicated to the right of the corresponding arrow. The tracings shown are from a single experiment representative of three separate experiments. (B) Concentration dependence. The magnitude of the peak of the calcium transient elicited by the indicated concentration of RANTES is shown.

FIG. 8.

Transmembrane signaling by the product of HHV- 6 U12: desensitization. The relative fluorescence was monitored from Indo-1-loaded K562 cells stably transfected with pCEU12c and during sequential addition of test substances at the times indicated by the arrowheads. The concentration and identity of each stimulus are indicated to the right of each arrow. The tracings are from a single experiment representative of two separate experiments.

DISCUSSION

Chemokine receptors form a subgroup of GCRs which are seven-transmembrane-domain proteins that couple extracellular stimuli to cellular responses through heterotrimeric G-proteins. Fourteen human leukocyte chemokine receptors have been cloned and characterized in ligand binding assays. They include five α-chemokine receptors (CXCRs), designated CXCR- 1, CXCR-2, CXCR-3, CXCR-4, and CXCR-5 (27, 48), and nine β-chemokine receptors (CCRs), designated CCR- 1, CCR- 2A, CCR-2B, CCR-3, CCR-4, CCR-5, CCR-6, CCR-7, and CCR- 8 (6, 48, 49, 59). The CXCRs are approximately 30% identical in sequence to the CCRs. Chemokine receptor analogs have been identified in a number of herpesviruses (11, 13, 42, 43). In this paper, we report that the U12 gene of HHV- 6B encodes a chemokine receptor that exhibits higher binding affinity for RANTES and relatively lower binding affinities for MIP-1β and MCP-1. The U12 receptor is capable of transducing specific chemokine signals to the cytoplasm that result in transient elevations of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, most potently in response to RANTES.

A striking feature of the HHV- 6 U12 gene is that it contains an intron region in the ORF, as do its homologs, HCMV UL33, murine CMV (MCMV) M33, and HHV- 7 U12 (16). The short mRNA of U12 was constructed from two exons after 77 nucleotides of an intron from the longer mRNA was spliced out (Fig. 2). The consensus 5′ and 3′ splice sites are MAGGTRAGT and (Y)nNYAGG, respectively (the very highly conserved positions are underlined) (26). The splice sites of U12 were CTG|GTAAGT and TCTTTAATAG|C, respectively (vertical lines are cleavage sites). The predicted splicing sites of U12 contain the consensus sequences, 5′ and 3′ splice sites CTGGTAAGT and TCTTTAATAGC, respectively, and the very highly conserved positions were also completely conserved in U12. In mammals, the RNA branch, which is one of the splicing intermediates generated simultaneously with cleavage of the pre-mRNA at the 5′ splice site, always forms at the adenosine of a conserved sequence element, the UNCURAC box. Selection of the branch point is based primarily upon relative position, 18 to 38 nucleotides upstream of the 3′ splice site (26). In U12, there was a predicted branch point 19 nucleotides upstream of the 3′ splice site. The nucleotide sequence of this region, CAATAAC, was similar to the UNCURAC box; the sequence of the branch point and its nearest three neighbors was identical to that of the UNCURAC box. Although the sequences of the splice sites and the predicted UNCURAC box of U12 had a high degree of similarity to those of the consensus splice sites and the UNCURAC box, approximately half of the U12 mRNAs in the HHV- 6-infected cells remained unspliced (Fig. 2A). This phenomenon suggests at least two possibilities: (i) HHV- 6 infection directly or indirectly affected the splicing efficiency; and (ii) the slight differences in the sequences of the splice sites and the UNCURAC box between U12 and the consensus sequences affected the splicing efficiency. Because the genomic U12-transfected cells contained two species of U12 mRNA in approximately equal amounts, we favor the hypothesis that the decreased splicing efficiency was related to the slight difference between U12 and the consensus sequences, although we do not know which is the critical nucleotide(s). The results of Western blot analysis suggested that the U12 protein was translated from the spliced mRNA (Fig. 5). If proteins were translated from the unspliced mRNA, it is possible that 3- and/or 35-kDa proteins were expressed from first ATG and/or the alternative ATG. However, the 3- kDa protein from the unspliced mRNA was not detected with anti-U12-N IgGs (data not shown), although we do not know whether the protein was not expressed or was expressed and then quickly degraded. Since the next suitable methionine in the unspliced mRNA, which is the first methionine of the original predicted ORF U12, is located within transmembrane region 1, we do not have antibodies for detection of the 35-kDa protein. Therefore, we do not know whether the 35-kDa protein from the U12 mRNAs is present in the virus-infected cells. However, functional protein could not be expressed when the pCEP4 protein expression system was used for the first methionine of the original predicted ORF U12 (data not shown). These results suggest that a lot of the unspliced mRNA precursor might remain in the nuclei and that a functional protein(s) might not be translated from the unspliced mRNA in the virus infected cells. Functional U12 protein was at least translated from the spliced mRNA, although we do not know where the unspliced mRNA localized and/or what regulates translation from the unspliced mRNA.

The U12 sequence shares specific features with all human and viral chemokine receptors: (i) a length of 352 amino acids, (ii) a highly acidic amino-terminal sequence, (iii) conserved cysteines in the third predicted extracellular loop and in the amino-terminal segment, (iv) a 16-residue highly basic third intracellular loop, and (v) a consensus sequence for N-linked glycosylation. The U12 chemokine receptor differs, however, from other CC chemokine receptors in that its affinity for RANTES is higher than for other ligands. For example, human CCR-1 produced in transiently transfected 293 cells binds with high affinity to MIP-1α (Kd = 5 nmol), while RANTES, MIP-1β, and MCP-1 competed more than 100 times less efficiently than MIP-1α (41).

Our data showed that RANTES, MCP-1, and MIP-1α can induce the U12 product signal transduction responses as measured by the Ca2+ flux. However, its signal transduction response was about 10 times lower than that of CCR-1. The pCEU12c-transfected K562 cells expressed more than 10-fold fewer binding sites than does the HCMV US28 protein (23) and may reflect a low level of expression of the U12 protein or some inhibition of transport of U12 to the plasma membrane. Alternatively, the U12 receptor may respond better to another, unidentified ligand(s) or may use a signal transduction pathway different from those used by the ligands tested in this study. Chemokine receptors were hitherto thought to be linked to the pertussis toxin-sensitive G-proteins and to classical signaling pathways via phospholipase Cβ, phospholipase A2, and phospholipase D (10, 39). In T cells, RANTES induced a biphasic mobilization of Ca2+ (7). One phase is linked to the pertussis toxin-sensitive G-protein of the classical pathway, and the other is linked to the pertussis toxin-insensitive G-protein and to protein tyrosine kinase. The pertussis toxin-sensitive signaling pathway is related to chemotaxis, and the insensitive pathway is related to up-regulation of IL-2 receptor expression, IL-2 and IL-5 production, and T-cell proliferation by means of a protein tyrosine kinase cascade. U12 may also act through the pertussis toxin-insensitive G-proteins, since its signaling activity was not inhibited by the toxin (data not shown). It is possible that U12 is linked to proliferation of HHV- 6-infected cells, as has been suggested for the chemokine receptor encoded by HHV- 8 (3).

Chemokines are structurally related 70- to 90-amino-acid polypeptides that regulate the trafficking and activation of mammalian leukocytes and thus may be important mediators of inflammation (8, 32). Chemokines are classified into three subfamilies, α, β, and γ. The α-chemokines act primarily upon neutrophils, and the γ-chemokines act upon lymphocytes, while the β-chemokines generally act upon monocytes, lymphocytes, basophils, and eosinophils. The biological roles of the viral chemokine receptors in herpesviruses are not yet known. HHV- 6 can infect mononuclear cells in blood, astrocytes, and epithelial cells in vivo (28, 33, 35). HHV- 6 can cause acute, chronic, and latent infections (46). It is possible that through the action of these receptors, the virus is able to regulate cellular processes to enhance viral replication or to inhibit an apoptotic response, thereby allowing the establishment of a latent infection. It is also possible that a viral chemokine receptor in latently or persistently infected cells is activated by chemokines, resulting in reactivation of the virus, since the U12 was the late gene (Fig. 4 and 5). This may be a step in the process of tumor development, as has been recently proposed by Arvanitakis et al. (3) for the KSHV GCR. Alternatively, the viral chemokine receptor may act as a molecular mimic to divert chemokines from their natural ligands and thereby subvert a local immune response. Finally, the fact that the major targets of HHV- 6 are CD4+ T lymphocytes may be important in our understanding of the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. An interaction between HHV- 6 and HIV has been proposed (21), and it is conceivable that the U12 protein may be used as a cofactor for HIV infection of CD4+ cells, as has been reported for a number of cellular chemokine receptors (9, 15, 17, 19, 44, 60) as well as the HCMV US28 protein (47). Further studies exploring the function of U12 in vivo may provide new insights into the molecular pathogenesis and latency of HHV- 6 infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank to Y. Horiguchi for performing the assay of chemokine binding to the U12 GCR. We are grateful to P. L. Ward for critical reading of and valuable comments on the manuscript.

This study was supported partly by a grant-in-aid by the Ministry of Education, Welfare and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ablashi D V, Balachandran N, Josephs S F, Hung C L, Krueger G R F, Kramarsky B, Salahuddin S Z, Gallo R C. Genomic polymorphism, growth properties, and immunologic variations in human herpesvirus-6 isolates. Virology. 1991;184:545–552. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90424-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahuja S K, Murphy P M. Molecular piracy of mammarian interleukin-8 receptor type B by herpesvirus saimiri. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20691–20694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvanitakis L, Geras-Raake E, Varma A, Gershengorn M C, Cerarman E. Human herpesvirus KSHV encodes a constitutively active G-protein-coupled receptor linked to cell proliferation. Nature. 1997;358:347–350. doi: 10.1038/385347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aubin J-T, Agut H, Collandre H, Yamanishi K, Chandran B, Montagnier L, Huraux J-M. Antigenic and genetic differentiation of the two putative types of human herpesvirus 6. J Virol Methods. 1993;41:223–234. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(93)90129-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aubin J-T, Collandre H, Candotti D, Ingrand D, Rouzioux C, Burgard M, Richard S, Huraux J-M, Agut H. Several groups among human herpesvirus 6 strains can be distinguished by Southern blotting and polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:367–372. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.367-372.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baba M, Imai T, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Takagi S, Hieshima K, Nomiyama H, Yoshie O. Identification of CCR6, the specific receptor for a novel lymphocyte-directed CC chemokine LARC. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14893–14898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bacon K B, Premack B A, Gardner P, Schall T J. Activation of dual T cell signaling pathways by the chemokine RANTES. Science. 1995;269:1727–1730. doi: 10.1126/science.7569902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines—CXC and CC chemokines. Adv Immunol. 1994;55:97–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleul C C, Farzan M, Choe H, Parolin C, Clark-Lewis I, Sodroski J, Springer T A. The lymphocyte chemoattractant SDF-1 is a ligand for LESTER/fusin and blocks HIV-1 entry. Nature. 1996;382:829–833. doi: 10.1038/382829a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bokoch G M. Chemoattractant signaling and leukocyte activation. Blood. 1995;86:1649–1660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cesarman E, Nador R G, Bai F, Bohenzky R A, Russo J J, Moore P S, Chang Y, Knowles D M. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus contains G protein-coupled receptor and cyclin D homologs which are expressed in Kaposi’s sarcoma and malignant lymphoma. J Virol. 1996;70:8218–8223. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8218-8223.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandran B, Tirawatnapong S, Pfeiffer B, Ablashi D V. Antigenic relationships among human herpesvirus-6 isolations. J Med Virol. 1992;37:247–254. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890370403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chee M S, Satchwell S C, Preddie E, Weston K M, Barrell B G. Human cytomegalovirus encodes three G protein-coupled receptor homologues. Nature (London) 1990;344:774–777. doi: 10.1038/344774a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chirgwin J M, Przybyla A E, MacDonald R J, Rutter W J. Isolation of biologically active ribonucleic acid from sources enriched in ribonuclease. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5294–5299. doi: 10.1021/bi00591a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, Sullivan N, Rollins B, Ponath P D, Wu L, Mackay C R, LaRosa G, Newman W, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. The β-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis-Poynter N J, Lynch D M, Vally H, Shellam G R, Rawlinson W D, Barrell B G, Farrell H E. Identification and characterization of a G protein-coupled receptor homolog encoded by murine cytomegarovirus. J Virol. 1997;71:1521–1529. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1521-1529.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng H, Liu R, Elmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton R E, Hill C M, Davis C B, Peiper S C, Schall T J, Littman D R, Landau N R. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dixon R A F, Sigal I S, Candelore M R, Register R B, Scattergood W, Rands E, Strader C D. Structural features required for ligand binding to the beta-adrenergic receptor. EMBO J. 1987;6:3269–3275. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02645.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doranz B J, Rucker J, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Samson M, Peiper R C, Parmentier M, Collman R G, Doms R W. A dual-tropic primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the β-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3, and CKR-2B as fusion cofactors. Cell. 1996;85:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Efstathiou S, Lawrence G L, Brown C M, Barrell B G. Identification of homologues to the human cytomegalovirus US22 gene family in human herpesvirus 6. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1661–1671. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-7-1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ensoli B, Lusso P, Schachter F, Josephs S F, Rappaport J, Negro F, Gallo R C, Wong-Staal F. Human herpes virus-6 increases HIV-1 expression in co-infected T cells via nuclear factors binding to the HIV-1 enhancer. EMBO J. 1989;8:3019–3027. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08452.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao J-L, Kuhns D B, Tiffany H L, McDermott D, Li X, Fracke U, Murphy P M. Structure and functional expression of the human macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha/RANTES receptor. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1421–1427. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao J-L, Murphy P M. Human cytomegarovirus open reading frame US28 encodes a functional β chemokine receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28539–28542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gompels U A, Carrigan D C, Carss A L, Arno J. Two groups of human herpesvirus 6 identified by sequence analysis of laboratory strains and variants from Hodgkin’s lymphoma and bone marrow transplant patients. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:613–622. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-4-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gompels U A, Nicolas J, Lawrence G, Jones M, Thomson B J, Martin M E D, Efstathiou S, Craxton M, Macaulay H A. The DNA sequence of human herpesvirus-6: structure, coding content, and genome evolution. Virology. 1995;209:29–51. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green M R. Biochemical mechanisms of constitutive and regulated pre-mRNA splicing. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1991;7:559–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.07.110191.003015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunn M D, Ngo V N, Ansel K M, Ekland E H, Cyster J G, Williams L T. A B-cell-homing chemokine made in lymphoid follicles activates Burkitt’s lymphoma receptor-1. Nature. 1998;391:799–803. doi: 10.1038/35876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He J, McCarthy M, Zhou Y. Infection of primary human fetal astrocytes by human herpesvirus 6. J Virol. 1996;70:1296–1300. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1296-1300.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins D G, Bleasby A J, Fuchs R. CLUSTAL V: improved software for multiple sequence alignment. Comput Appl Biol Sci. 1992;8:189–191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Isegawa, Y., et al. Unpublished data.

- 30.Josephs S F, Salahuddin S Z, Ablashi D V, Schachter F, Wong-Staal F, Gallo R C. Genomic analyses of the human B lymphotropic virus. Science. 1986;234:601–603. doi: 10.1126/science.3020691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karnik S S, Sakmar T P, Chen H-B, Khorana H G. Cysteine residues 110 and 187 are essential for the formation of correct structure in bovine rhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:8459–8463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelner G S, Kennedy J, Bacon K B, Kleyensteuber S, Largaespada D A, Jenkins N A, Copeland N G, Bazan J F, Moore K W, Schall T J, Zlotnik A. Lymphotactin: a cytokine that represents a new class of chemokine. Science. 1994;266:1395–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.7973732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kondo K, Kondo T, Okuno T, Takahashi M, Yamanishi K. Latent human herpesvirus 6 infection of human monocytes/macrophages. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:1401–1408. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-6-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawrence G L, Chee M, Craxton M A, Gompels U A, Honess R W, Barrell B G. Human herpesvirus 6 is closely related to human cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 1990;64:287–299. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.1.287-299.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lusso P, Malnati M S, Garzino-Demo A. Infection of natural killer cells by human herpesvirus 6. Nature. 1993;362:458–462. doi: 10.1038/362458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lusso P, Markhan P D, Tschachler E, Di Marco Veronese F, Salahuddin S Z, Ablashi D V, Pahwa S, Grohn K, Gallo R C. In vitro cellular tropism of B-lymphotropic virus (human herpesvirus-6) J Exp Med. 1988;167:1659–1670. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.5.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Margulies B J, Browne H, Gibson W. Identification of the human cytomegalovirus G protein-coupled receptor homologue encoded by UL33 in infected cells and enveloped virus particles. Virology. 1996;225:111–125. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukai T, Isegawa Y, Yamanishi K. Identification of the major capsid protein gene of human herpesvirus 7. Virus Res. 1995;37:55–62. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00022-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy P M. The molecular biology of leukocyte chemoattractant receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:593–633. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy P M, Tiffany L H. Cloning of complementary DNA encoding a functional human interleukin-8 receptor. Science. 1991;253:1280–1283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neote K, DiGregorio D, Mak J Y, Horuk R, Schall T J. Molecular cloning, functional expression, and signaling characteristics of a C-C chemokine receptor. Cell. 1993;72:415–425. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90118-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nicolas J. Determination and analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of human herpesvirus 7. J Virol. 1996;70:5975–5989. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5975-5989.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicolas J, Cameron K R, Honess R W. Herpesvirus saimiri encodes homologues of G protein-coupled receptors and cyclins. Nature (London) 1992;355:362–365. doi: 10.1038/355362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oberlin E, Amara A, Bachelerie F, Bessia C, Virelizier J-L, Arenzana-Seisdenos F, Schwartz O, Heard J-M, Legler D F, Loetscher M, Baggiolini M, Moser B. The CXC chemokine SDF-1 is the ligand for LESTER/fusin and prevents infection by T-cell-line-adapted HIV-1. Nature. 1996;328:833–835. doi: 10.1038/382833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okuno T, Yamanishi K, Shiraki K, Takahashhi M. Synthesis and processing of glycoproteins of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) as studied with monoclonal antibodies to VZV antigens. Virology. 1983;129:357–368. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pellett P E, Black J B. Human herpesvirus 6. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2587–2608. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pleskoff O, Tréboute C, Brelot A, Heveker N, Seman M, Alizon M. Identification of a chemokine receptor encoded by human cytomegalovirus as a cofactor for HIV-1 entry. Science. 1997;276:1874–1878. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5320.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Premack B A, Schall T J. Chemokine receptors: gateways to inflammation and infection. Nat Med. 1996;2:1174–1178. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roos R S, Loetscher M, Legler D F, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M, Moser B. Identification of CCR8, the receptor for the human CC chemokine I-309. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17251–17254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salahuddin S Z, Ablashi D V, Markham P D, Josephs S F, Sturzegger S, Kaplan M, Halligan G, Biberfeld P, Wong-Staal F, Kramarsky B, Gallo R C. Isolation of a new virus, HBLV, in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders. Science. 1986;234:596–601. doi: 10.1126/science.2876520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schirmer E C, Wyatt L S, Yamanishi K, Rodriguez W J, Frenkel N. Differentiation between two distinct classes of viruses now classified as human herpesvirus 6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5922–5926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sung C-H, Schneider B G, Agarwal N, Papermaster D S, Nathans J. Functional heterogeneity of mutant rhodopsins responsible for autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8840–8844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takahashi K, Sonoda S, Higashi K, Kondo T, Takahashi H, Takahashi M, Yamanishi K. Predominant CD4+ T lymphocyte tropism of human herpesvirus 6-related virus. J Virol. 1989;63:3161–3164. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3161-3163.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takeda K, Nakagawa N, Yamamoto T, Inagi R, Kawanishi K, Isegawa Y, Yamanishi K. Prokaryotic expression of an immediate-early gene of human herpesvirus 6 and analysis of its viral antigen expression on human cells. Virus Res. 1996;42:193–200. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(96)01287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wyatt L S, Balachandran N, Frenkel N. Variations in the replication and antigenic properties of human herpesvirus 6 strains. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:852–857. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.4.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamamoto T, Mukai T, Kondo K, Yamanishi K. Variation of DNA sequence in immediate-early gene of human herpesvirus 6 and variant identification by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:473–476. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.473-476.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamanishi K, Okuno T, Shiraki K, Takahashi M, Kondo T, Asada Y, Kurata T. Identification of human herpesvirus-6 as a causal agent for exanthem subitum. Lancet. 1988;i:1065–1067. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91893-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoshida R, Imai T, Hieshima K, Kusuda J, Baba M, Kitaura M, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Nomiyama H, Yoshie O. Molecular cloning of a novel human CC chemokine EBI1-ligand chemokine that is a specific functional ligand for EBI1, CCR7. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13803–13809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang L, Huang Y, He T, Cao Y, Ho D D. HIV-1 subtype and second-receptor use. Nature. 1996;383:768. doi: 10.1038/383768a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]