Abstract

Objectives

Systematically synthesise evidence of physical activity interventions for people experiencing homelessness (PEH).

Design

Mixed-methods systematic review.

Data sources

EMBASE, Web of Science, CINAHL, PubMed (MEDLINE), PsycINFO, SPORTDiscus and Cochrane Library, searched from inception to October 2022.

Eligibility criteria

PICO framework: population (quantitative/qualitative studies of PEH from high-income countries); intervention (physical activity); comparison (with/without comparator) and outcome (any health/well-being-related outcome). The risk of bias was assessed using Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools.

Results

3615 records were screened, generating 18 reports (17 studies, 11 qualitative and 6 quantitative (1 randomised controlled trial, 4 quasi-experimental, 1 analytical cross-sectional)) from the UK, USA, Denmark and Australia, including 554 participants (516 PEH, 38 staff). Interventions included soccer (n=7), group exercise (indoor (n=3), outdoor (n=5)) and individual activities (n=2). The risk of bias assessment found study quality to vary; with 6 being high, 6 moderate, 4 low and 1 very low. A mixed-methods synthesis identified physical and mental health benefits. Qualitative evidence highlighted benefits carried into wider life, the challenges of participating and the positive impact of physical activity on addiction. Qualitative and quantitative evidence was aligned demonstrating the mental health benefits of outdoor exercise and increased physical activity from indoor group exercise. Quantitative evidence also suggests improved musculoskeletal health, cardiovascular fitness, postural balance and blood lipid markers (p<0.05).

Conclusion

Qualitative evidence suggests that physical activity interventions for PEH can benefit health and well-being with positive translation to wider life. There was limited positive quantitative evidence, although most was inconclusive. Although the evidence suggests a potential recommendation for physical activity interventions for PEH, results may not be transferable outside high-income countries. Further research is required to determine the effectiveness and optimal programme design.

Keywords: Physical activity, Exercise, Health, Physical fitness, Public health

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

People experiencing homelessness suffer a higher burden of physical and mental health conditions than housed populations.

Limited studies suggest that regular physical activity may address many health conditions prevalent among people experiencing homelessness, although the evidence has not been systematically reviewed.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

A variety of physical activity interventions have been designed and provided to engage people experiencing homelessness, including soccer, outdoor and indoor group activities, and individual activities.

The synthesis of qualitative and quantitative evidence suggests that physical activity can benefit the mental and physical health of people experiencing homelessness with positive translation of benefits to wider life.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Group physical activity interventions seemed to be the most benefitical to people experiencing homelessness, perhaps due to its facilitation of social support and connection.

Qualitative data highlighted the pressure some participants felt in competetive tournament settings. Organisers should recognise this and consider support to ameliorate impacts of pressure experienced.

Consideration should be given to the intensity level of physical activity interventions for this population. Given the high prevalence and poor health of many people experiencing homelessness, lower threshhold activities are likely to be more inclusive for the population.

Introduction

Homelessness is an extreme form of social exclusion1 2 related to poverty in high-income countries.3 People experiencing homelessness (PEH) are defined as those who are ‘roofless’ (eg, no fixed abode) and ‘houseless’ (eg, living in hostel, shelter, temporary accommodation) in accordance with the European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless.4 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, homelessness in the UK had increased annually since 20105 with estimates of all categories of homelessness in England standing at 280 000 people,6 of which 4266 were estimated to be sleeping on the streets.7 The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates that almost 2 million people are experiencing homelessness in 35 OECD countries.8

PEH have poorer health than the general population,9 10 often characterised by a tri-morbidity of mental health diagnoses, chronic physical health conditions and addiction.9 Poor health is thought to be both precipitated and exacerbated by poor living conditions, lack of resources, social exclusion, stigmatisation and difficulty accessing suitable health services.11

Physical activity is beneficial for people with disabilities and chronic health conditions, both from a physical health and a social perspective. Guidance suggests that the type and amount of physical activity should be determined by a person’s abilities and the severity of their condition or disability, which may change over time.12 PEH live with a high burden of physical deficits,13 falls and frailty,14 respiratory disease, cardiac problems, stroke and diabetes,15 which could be positively influenced by physical activity. A recent scoping review found that among PEH, overall levels of physical activity appeared to be low, though the authors recognised that across studies reviewed, physical activity levels varied.16 Low levels of physical activity could be due to limited opportunities or barriers to accessing physical activity, rather than through choice. Consequently, PEH may miss out on health gains and a reduced risk of harm that physical activity affords people with these conditions. It is important that this population has opportunities for physical activity to stabilise or reverse physical declines associated with homelessness. Given the multiple barriers PEH face accessing services, it may be important that physical activity interventions are specifically tailored to their needs to optimise reach and participation. This perspective is consistent with public engagement activities with PEH and staff who care for them, which took place prior to the commencement of this research. This research poses two research questions: what is the range of physical activity interventions provided to PEH? And, what is the evidence supporting the effectiveness of these interventions?

Aims

This review aims to summarise the available evidence for physical activity interventions intended to improve health outcomes of adults experiencing homelessness, focusing on physical activity interventions and their effectiveness in improving health outcomes.

Methods

Design

A preliminary scoping review revealed that published literature in the field of physical activity for PEH comprised both quantitative and qualitative research. Therefore, a mixed-methods systematic review was adopted. This allowed for the findings of effectiveness (quantitative evidence) and participant experiences (qualitative evidence) to be brought together, to facilitate a broader understanding of whether and how interventions worked.17 18 This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines19 and checklist,20 and the protocol was registered a priori in PROSPERO database (reference number: CRD42020216716).

Identification

Defining search terms

Initial search terms were generated by reviewers (JFD, RR-W and JB), who between them, have extensive clinical and research expertise and experience in the health of PEH, physical activity and systematic review methodology. The search terms were refined and tailored for a preliminary search of MEDLINE, and used to test the proof of concept and search strategy. The search syntax (online supplemental file 1) was designed by a professional librarian in collaboration with two reviewers (JFD and RR-W).

bjsports-2023-107562supp001.pdf (75.6KB, pdf)

Searches

Search terms were refined, adapted and run in MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, CINAHL, PsycINFO, SPORTDiscus and the Cochrane Library. The searches were conducted on 17 February 2021, including literature from the previous 30 years (1991–2021) and restricted to English language only. The searches were re-run using the original search terms by a specialist librarian at Trinity College Dublin on 19 October 2022 to identify any new reports published between 21 October 2021 and 19 October 2022. All previous databases were searched, except SPORTDiscus, as it was unavailable in the institution’s library databases. Duplicates were removed at this stage. The reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and all included studies were hand-searched for reports to be added for screening. Corresponding authors of records that comprised an abstract only were contacted, where possible, to request full-text reports. Additionally, an expert reviewer suggested a study unidentified by searches, but met the inclusion criteria, so it was put forward for screening.

Screening

Title and abstract screening

On completion of the identification process, all report titles and abstracts were uploaded to the online systematic reviewing management system, Covidence. Two pairs of reviewers (JFD/RR-W and JFD/JB) independently performed (a) title and abstract screening and (b) full-text screening, judged against predetermined protocol criteria. In the event of disagreement, the third reviewer (JB or RR-W) was consulted for an additional opinion.

The PICO framework was used to identify inclusion criteria. For inclusion, all the following criteria were to be met:

Population

Studies that included adults who were homeless under the European Typology of Homelessness and housing Exclusion (ETHOS) criteria for homelessness,4 that is rooflessness, houselessness, living in insecure housing or living in inadequate housing. Age >18 years.

Intervention

Studies that included any physical activity intervention delivered as a stand-alone intervention or part of multimodal intervention, in any setting. Studies undertaken in high-income countries21 were included, where there is assumed consistency in health and social care infrastructure as well as in family and community support systems, which impact how homelessness is perceived and managed.22

Outcome

This mixed-methods review included quantitative studies reporting any measures demonstrating health outcomes, including but not limited to primary measures such as cardiovascular fitness and strength, and qualitative findings describing participant perceptions linking physical activity intervention to health and/or well-being outcomes.

Comparison

The presence of a comparison group was not required as an inclusion criterion.

Study types

This review considered quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies.

Risk of bias assessment

In recognition of the diverse study designs included in this review, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tool portfolio was a key resource for judging quality and risk of bias.23 24 These tools provide a criterion-based checklist for determining presence (yes), absence (no), a lack of clarity (unclear) or a lack of applicability (not applicable) of quality in studies across a variety of methods.25 To determine the dependability and credibility of qualitative reports, their ConQual ratings were calculated.26 Although Munn et al discourage cut-off values in determining the quality level in quantitative studies, for clarity and consistency of this mixed-methods review, a pragmatic decision was made to select cut-offs of <25% (very low), <50% (low), <75% (moderate) and >75% (high). Munn et al state that if cut-offs are preferred, these thresholds are best decided by the reviewers themselves.25 A summary of the quality assessment of all reports is given in online supplemental file 2.

bjsports-2023-107562supp002.pdf (105.8KB, pdf)

Protocol deviation

This review was registered on PROSPERO, registration number: CRD42020216716. Found at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=216716. In the PROSPERO protocol, we stated we would use Cochrane and Downs and Black risk of bias tools. However, once the diversity of the final studies was identified, the review team recognised that JBI risk of bias tools were more suited to the studies within our review.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted to an excel spreadsheet: study design, inclusion criteria, participants (description, number, accommodation, age, education, employment, ethnicity, race, biological sex, mental health and physical health), intervention (setting, frequency, intensity, time, type, group or individual, presence of other non-physical activity intervention components), quantitative outcome measures and qualitative themes.

Initially, JFD carried out and collated data extraction from five reports. This was reviewed by RR-W and JB to ensure accuracy and consistency. Once all three team members agreed on the data extraction process, the remaining reports were divided among the team for completion of data extraction. Data from each report were checked for accuracy by another member of the research team. Any inconsistencies in interpretation or reporting were discussed, and consensus was reached.

Strategy for mixed-methods data synthesis

The synthesis followed the JBI methodology for mixed-methods systematic reviews,27 whereby established convergent, segregated, results-based mixed-methods frameworks for systematic reviewing were employed.28 29 First, qualitative and quantitative data were meaningfully categorised by JFD and JB, respectively. Each reviewer conducted their analysis separately, independently and concurrently. JFD adopted a reflexive thematic analysis approach to synthesise the qualitative data, by extracting all qualitative results into an excel spreadsheet and following the six processes of thematic analysis, namely: familiarisation; coding; generating initial themes; reviewing and developing themes; refining, defining and naming themes; and writing up.30 Details of themes are outlined in online supplemental file 3. Due to the heterogeneity of quantitative studies, it was not possible for JB to carry out a meta-analysis. So narrative synthesis was used. Quantitative findings were then ‘qualitized’ to transform them into a qualitative, descriptive format. Next, quantitative and qualitative evidence were linked and organised to produce an overall ‘configured analysis’27 and reported as a series of tables and combined narrative synthesis.

bjsports-2023-107562supp003.pdf (94.3KB, pdf)

Equality and diversity statement

Our author and librarian team consisted of three women and two men. The author team included early and mid-career researchers and clinicians across two disciplines (medicine and physiotherapy) from two countries (UK and Ireland). This research explores physical activity interventions for PEH, an under-served, often marginalised and excluded population who experience extreme socioeconomic disadvantage. This population is known to have complex and chronic health needs and is an often-overlooked group in physical activity research.

Results

Study selection

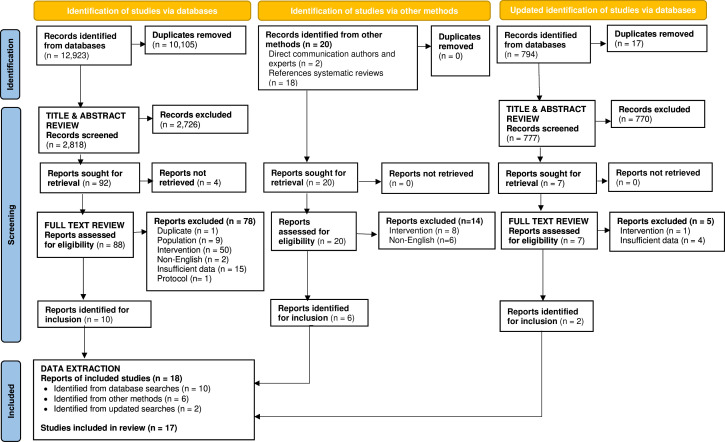

13 737 records were identified through searches. After the removal of duplicates (n=10 122), 3615 records were screened by title and abstract, with 3496 records excluded at this stage. 119 reports were sought for full-text review, 4 could not be found, so 115 full-text reports were reviewed. Of these, 97 records were excluded at this stage (exclusions based on: 1 duplicate, 9 population, 59 intervention, 8 non-English language, 19 insufficient data, 1 protocol only). Finally, 18 reports were included for quality checking. Two reports described different aspects of a single study. Therefore, data were extracted from 18 reports describing 17 studies. The full identification, screening and inclusion process are outlined in a PRISMA diagram (figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses.

Quality assessment

The majority of the 11 qualitative studies were high quality, with 8 reporting at least 7 out of 10 quality criteria on the JBI checklist for qualitative studies (online supplemental file 2). One study was of very low quality,31 with only the statement of researcher positionality being clear, and all other criteria either unreported or unclear. Of the quantitative studies, the one randomised controlled trial (RCT)32 was assessed as moderate quality due to methodological limitations, for example, lack of clarity regarding blinding of assessor and whether treatment groups were concealed. The analytical cross-sectional study was of moderate quality, and in general, quasi-experimental studies were of high quality.

Description of studies

Eighteen reports, describing 17 studies, were included (table 1). Of these studies, 7 were from the USA, 5 from the UK, 3 from Denmark and 2 from Australia. The variety of designs across these studies comprised 11 qualitative and 6 quantitative reports (4 quasi-experimental, 1 RCT and 1 analytical cross-sectional). The interventions addressed varied, including soccer (n=7); group outdoor exercise (n=5); group indoor multimodal exercise (n=3) and individual multimodal interventions (n=2) (online supplemental file 4).

Table 1.

Summary of included studies

| Study | Location | Study design | Description of homelessness/accommodation | Inclusion and exclusion criteria/study drop-outs | No of participants | Intervention |

| Dawes et al, 201938 | UK | Qualitative (interview) | No fixed abode, living in hostel, temporary accommodation and permanent accommodation after being homeless | Attendees of one of two park-based running groups operated by the charity ‘A Mile in her Shoes’ in London for women defined as homeless, no specified exclusion criteria or study drop-outs reported | 11 | Outdoor Running (groups) |

| Grabbe et al, 201347 | USA | Qualitative (interview) | No fixed abode or living in shelters | Participation in at least eight gardening sessions in a daytime shelter for homeless women in a large south-eastern US city, no specified exclusion criteria or study drop-outs reported | 8 | Outdoor Gardening (groups) |

| Grimes and Smirnova, 202048 | USA | Qualitative (interview) | Temporarily housed and most had experienced two or three episodes of homelessness | Men experiencing homelessness who has completed the earn-a-bike programme in the previous year in Kansas, no specified exclusion criteria or study drop-outs reported | 16 | Mixed individual intervention (bicycle provision, cycle safety and maintenance training) |

| Helge et al, 2014 and Randers et al, 201239 41 |

Denmark | Quasi-experimental (non-randomised controlled intervention study) | Recruited from homeless shelters and unemployment offices. | Men experiencing homelessness who were accessing services in shelters and unemployment offices in Copenhagen, no specified exclusion criteria, withdrawals football group (6/33 consented but did not show up for testing and 9/27 did not complete intervention), control group (4/22 consented but did not show up for testing and 8/18 completed the intervention), no differences in pre-test scores among drop-outs compared with the rest of the subjects | 28 | Soccer (group training) |

| Kendzor et al, 201732 | USA | Randomised controlled trial | Living in a transitional shelter for people experiencing homelessness | (1) At least 18 years of age, (2) willing and able to attend study visits, (3) score ≥4 on the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine—Short Form (REALM-SF) indicating >sixth-grade literacy level, (4) physically ambulatory, (5) residents of a transitional shelter in Dallas, Texas (able to show an ID badge) and (6) had been living in the transitional shelter for ≤3 months, exclusions (n=10) due to not reaching the minimum reading level (n=9) and/or staying at the shelter for more than 3 months (n=3), Drop-outs, control group (n=0), intervention (2/17). Reason for drop-out not stated. | 32 | Mixed individual intervention (pedometer with step count goals, health education, provision of fruit and vegetables) |

| Knestaut et al, 201031 | USA | Qualitative (self-reported form, debrief and journal) | People living in homeless shelter | Adults who had taken part in shelter-based dance programme, no specified exclusion criteria or study drop-outs reported | 11 | Indoor multimodal exercise (Instructor-led dance group) |

| Magee and Jeanes, 201344 | UK | Qualitative (interview) | Living in social services, accommodation or hostels and spent time with no fixed abode | Male participants of the UK squad who attended the inaugural Homeless World Cup, no specified exclusion criteria or study drop-outs reported | 6 | Soccer (group training and Homeless World Cup participation) |

| Malden et al, 201936 | UK | Qualitative (interview) | Living in hostel accommodation or on the streets | Participants of the Street Fit Scotland intervention who attended both the fitness classes and peer support components of the intervention in March 2016, no specified exclusion criteria, 2/12 of those eligible did not participate—no reason specified. | 10 | Indoor multimodal exercise (Instructor-led, leisure centre-based group, with peer support) |

| Norton et al, 202034 | USA | Quasi-experimental (non-equivalent groups longitudinal design) | Living at a shelter for women without housing | Women residents of a shelter in a large city in Texas, USA who had participated in the HOPE Adventure Therapy pilot programme, no specified exclusion criteria or study drop-outs reported | 82 | Outdoor Adventure (groups) |

| Parry et al, 202135 | UK | Qualitative (realist evaluation: interviews, focus groups and diary room) | Young people experiencing or at risk of homelessness (no further details provided) | Young people with experience or at risk of homelessness who attended at least one MST4Life programme workshop (Phase 1) during the time of data collection and housing staff with one-to-one experience of working with the MST4Life participants, no specified exclusion criteria or study drop-outs reported | 30 PEH 6 housing service staff 5 OAE staff |

Outdoor Adventure (groups) |

| Parry et al, 202146 | UK | Qualitative (diary room) | Living in supported accommodation for young people experiencing homelessness | Young people with experience or at risk of homelessness who attended and engaged in Phase 1 of MST4Life from different cohorts of MST4Lifeover a 5-year period (2014–2019). 50/113 eligible participants did not participate-reasons not specified, no drop-outs | 54 | Outdoor Adventure (groups) |

| Randers 201042 | Denmark | Quasi-experimental (non-randomised controlled intervention study) | Nature of homelessness among ‘homeless participants’ undefined | Homeless men, no specified exclusion criteria or study drop-outs reported | 15 | Soccer (group training) |

| Randers et al, 201840 | Denmark | Analytical cross-sectional (intervention study) | Described as homeless, no further details provided | Women experiencing homelessness from three countries (Denmark, Norway and Belgium) who participated in 4-a-side street soccer at Women’s Homeless World Cup in Amsterdam in December 2015, no specified exclusion criteria or study drop-outs reported | 15 | Soccer (Homeless World Cup tournament participation) |

| Sherry, 201045 | Australia | Qualitative (interview) | Experience of homelessness in the preceding 2 years or were participating in a drug or alcohol rehabilitation programme | Team members of the ‘Street Socceroos’, the Australian Homeless World Cup team and, no specified exclusion criteria or study drop-outs reported | 8 | Soccer (group training and Homeless World Cup participation) |

| Sherry and Strybosch, 201243 | Australia | Qualitative (Ethnographic case study) | Past or current experience of homelessness and associated social disadvantage | Team members of Australia’s Community Street Soccer Programme (CSSP) over a 4-year period, which is for people who are homeless or experience of homelessness/social disadvantage, staff from the CSSP and key stakeholder or support workers involved in the development and delivery of the programme, no specified exclusion criteria, no study drop-outs | 165 players 11 Coaches 10 (support workers) |

Soccer (group training) |

| Shors et al, 201456 | USA | Quasi-experimental (intervention study) | ‘Recently homeless’ with experience of poverty, trauma or addictive behaviours | Young mothers who were recently homeless then ‘rescued from the streets’ and given housing and food in a residential centre, where they lived with their children, no specified exclusion criteria or study drop-outs reported | 15 | Indoor multimodal exercise (Instructor-led meditation and choreographed aerobic group exercise) |

| Peachey et al, 201333 | USA | Qualitative (focus groups) | Recruited from a tournament for homeless individuals. So, assumption that all participants were homeless—no further details supplied | Players and coaches who ‘represented the geographic areas’ of the US-based Street Soccer USA Cup, no specified exclusion criteria or study drop-outs reported | 11 players 6 staff |

Soccer (National Cup tournament participation) |

PEH, people experiencing homelessness.

bjsports-2023-107562supp004.pdf (101.5KB, pdf)

Study populations

Online supplemental file 5 provides detail of each study population included in this systematic review. Across the 17 studies, 516 PEH were participants. Some studies included women only (n=5), men only (n=5) or mixed cohorts (n=7). Three qualitative studies reported staff/coaches’ perspectives (n=38). The age range of participants who were homeless was 16–65 years. It was specified in the review protocol that only studies with participants >18 years would be included. However, for pragmatic reasons, several studies33–37 were included despite containing participants from the age of 16 years. In these studies, proportions of participants <18 years were not specified, although one study38 stated that the ‘majority’ of participants were between the ages of 20 and 24 years. Descriptions of study participants’ experiences of homelessness varied but were mainly focused on: street homeless, living in hostel/shelter, transitional/social service accommodation or ‘homeless at time of intervention’. Studies that focused on Street Soccer and the Homeless World Cup invited participation from PEH and other socially excluded groups, for example, people attending unemployment offices or drug rehabilitation services. Although these studies did not define proportions of participants experiencing homelessness, for pragmatic reasons they were included, as the intervention had been specifically designed for PEH. Only one study specified exclusion criteria,32 which were based on reading ability and length of time staying in the shelter. In two studies, several participants were eligible but chose not to participate,39 40 the reasons for which was not specified. The number of study drop-outs was described in three reports/two studies,32 36 37 but the reasons for drop-out were not specified.

bjsports-2023-107562supp005.pdf (92.1KB, pdf)

Physical activity interventions and their components

Online supplemental file 4 provides a description of all included interventions. The studies included seven soccer interventions (tournament focused (n=2), group training focused (n=3) and combining group training and tournament participation (n=2)); five group outdoor exercise (adventure training (n=3), running (n=1) and gardening (n=1)); three group indoor multimodal exercise (aerobic-based circuits (n=2) and dance (n=1)) and two individual multimodal interventions (pedometer with step goals and earn-a-bike scheme). Online supplemental file 4 also provides programming variables, including: setting; frequency; intensity; time; type and the presence of other non-physical activity components of multimodal interventions.

Soccer

Seven studies investigated the impact of soccer for PEH. These studies (eight reports) explored soccer group training (n=4),39 41–43 tournament participation (n=2)33 40 and interventions of training for and participating in tournaments (n=2).44 45 The studies involving tournaments were focused around national or international tournaments such as the Homeless World Cup or Street Soccer USA Cup.33 40 44 45

Group outdoor exercise

Five studies provided evidence of the value of group outdoor exercise. These included group outdoor adventure (n=3),34 35 46 women’s running groups (n=1)38 and women’s gardening groups (n=1).47 These studies described multimodal interventions, including outdoor adventure interventions which contained multiple activities (eg, archery, rock climbing, hiking), and all studies reported additional support, such as the provision of education, debriefing, opportunities for reflection, childcare, food or clothing.

Group indoor multimodal exercise

All group indoor multimodal exercise studies (n=3) were instructor-led interventions provided to small groups in settings such as leisure centres36 or shelter recreation rooms.31 All studies were multimodal as they combined different types of activity, for example, stretching, cardiovascular exercise, dance, aerobic circuits, strength-based exercise to music and meditation.

Individual multimodal interventions

Two studies reported interventions for individuals.32 48 One involved participants wearing a pedometer and working towards a step goal. This was provided along with an educational newsletter and fruit/vegetable snacks.32 The other study described cycle training to learn road safety and cycle maintenance, alongside earning a bicycle for individual use.48

Intervention and outcomes

Findings are described across four tables (tables 2–5). Table 2 shows all synthesised findings relating to mental health and table 3 shows all synthesised findings relating to physical health where the configured analysis identified qualitative and quantitative evidence supporting matched themes. Table 4 shows evidence that was identified in either quantitative or qualitative reports alone. For example, findings, where only quantitative data existed, were related to bone health and blood markers. Whereas qualitative evidence only was identified relating to other important aspects of physical activity, not specifically or directly health-related, such as the benefits carried into wider life, challenges of participation and addiction.

Table 2.

Summary of synthesised findings relating to mental health benefits of physical activity participation

| Qualitative | Quantitative | Synthesis | ||||

| Theme | Subtheme | Level of confidence in evidence for intervention type | Description of outcome and measurement tool | Outcome data | Level of confidence in evidence for intervention type | Overarching synthesised finding |

| Belief that physical activity facilitated people experiencing homelessness in self-development and their ability to cope with life situations | Confidence, empowerment and self-esteem | High (Group running,38 Soccer-group training and tournament participation,44 Indoor group instructor-led exercise36) Moderate (Earn-a-bike,48 Group outdoor adventure35) Low (Gardening group,47 Soccer-group training43) Very low (Group instructor-led dance31) |

No change to goal directed energy, measured using The Hope scale (agency subscale) | No significant difference between intervention and control groups | Moderate (Group outdoor adventure34) | High quality qualitative evidence that group running, soccer and indoor group exercise and moderate quality qualitative evidence that group outdoor adventure and Earn-a-bike enhance confidence, empowerment and self-esteem. However, quantitative evidence does not support this. |

| Resilience, coping and hope | High (Group running,38 Group outdoor adventure46) Moderate (Group outdoor adventure35) Low (Gardening group,47 Soccer-group training43) Very low (Group instructor-led dance31) |

No change to planning and accomplishing goals, measured using The Hope scale (pathway) | No significant difference between intervention and control groups | Moderate (Group outdoor adventure34) | High quality qualitative evidence that group running and group outdoor adventure enhances resilience, coping and hope, but quantitative evidence does not support this. | |

| Independence, focus, personal development and relationships | High (Group running,38 Soccer-group training and tournament participation44) Moderate (Group outdoor adventure,35 Earn-a-bike48) Low (Gardening group,47 Soccer-group training and tournament participation45) Very low (Group instructor-led dance31) |

Positive changes in life functioning, measured by (Outcomes rating scale), including interpersonal and social well-being | Significant difference between IG and CG for social wellness (p<0.01) | Moderate (Group outdoor adventure34) | High quality qualitative evidence that group running, and soccer and moderate quality qualitative evidence that group outdoor adventure and Earn-a-bike enhance independence, self-regulation and personal development. This is supported by moderate quality quantitative evidence that outdoor adventure improves life functioning. | |

| Belief that physical activity resulted in people experiencing homelessness feeling mentally better | Positive effect on stress and anxiety | High (Group running,38 Indoor group instructor-led exercise,36 Group outdoor adventure46) Moderate (Soccer-tournament participation,33 Earn-a-bike48) Low (Gardening group,47 Soccer-group training and tournament participation45) Very low (Group instructor-led dance31) |

Positive changes to flow and worry, measured by the Flow Kurtz Scala (Flow Short scale) | People who anticipated in soccer tournament scored highly for flow (5.5±0.8) whereas the score for worry was moderate (4.6±1.3) | Moderate (Soccer-tournament participation40) | High quality qualitative evidence that group running, indoor group exercise and outdoor adventure and moderate quality qualitative evidence that soccer and Earn-a-bike have a positive effect on stress and anxiety. This is not supported by quantitative evidence. |

| Decreased anxiety levels, measured by Beck Anxiety Inventory | A significant decrease in anxiety in intervention group, but p value not supplied | Low (Indoor group aerobic-based dance56 | ||||

| Positive effect on mood and state of mind | High (Group running,38 Soccer-group training and tournament participation,44 Indoor group instructor-led exercise,36 Group outdoor adventure46) Moderate (Earn-a-bike48) Low (Gardening group47) Very low (Group instructor-led dance31) |

Positive changes in life functioning, measured by (Outcomes rating scale), including personal and overall well-being | An increase in overall well-being at a faster rate in intervention group compared with control group (p<0.05) | Moderate (Group outdoor adventure34) | High quality qualitative evidence that group running, soccer and indoor group exercise and moderate quality qualitative evidence that Earn-a-bike enhances mood and state of mind. This is supported by moderate quality quantitative evidence that group outdoor adventure improves well-being. | |

| Decreased depression levels, measured by Beck Depression Inventory | Significant decrease in depression in intervention group, p value not supplied | Low (Indoor group aerobic-based dance56) | ||||

The impact of physical activity interventions on the mental health of PEH.

CG, control group; IG, intervention group; PEH, people experiencing homelessness.

Table 3.

Summary of synthesised findings relating to physical health benefits of physical activity participation

| Qualitative | Quantitative | Synthesis | ||||

| Theme | Subtheme | Level of confidence in evidence for intervention type | Description of outcome and measurement tool | Outcome data | Level of confidence in evidence for intervention type | Overarching synthesised finding |

| Belief that physical activity improves the body shape of people experiencing homelessness | Improved body shape and self-image | High (Running groups,38 Indoor group instructor-led exercise36) | Positive changes to body composition, measures using X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) | Weightbearing fat mass decreased by 13% from 14.0±7.2 kg to 12.2±6.5 kg. This change was significantly different (p=0.008) in the intervention group compared with the control group. | High (Soccer-group training41) | High quality qualitative evidence that group running and indoor group exercise can improve body shape and weight loss. This is supported by high quality quantitative evidence that soccer significantly decreases fat mass. |

| Weight loss | High (Running groups38) Low (Soccer-group training43) |

|||||

| Total fat mass decreased by 13% from 1.7 kg (95% CI: −2.6 to −0.9 kg over 12 weeks. This change was significantly different (p<0.01) in the intervention group compared with the control group. | High (Soccer-group training39) | |||||

| Belief that physical activity improves physical condition of people experiencing homelessness | Perception of improved fitness levels | High (Running groups,38 Soccer-group training and Tournament participation,44 Indoor group instructor-led exercise36) Moderate (Earn-a-bike48) Low (Soccer-group training43) Very low (Group instructor-led dance31) |

Positive changes to cardiovascular fitness, measured using cycle ergometer test to exhaustion | Maximal oxygen uptake was elevated from 2.69±0.47 to 2.95±0.52 L O2/min (95% CI: 6.7 to 13.1%) after 12 weeks in the intervention group. This change was significantly different (p<0.01) compared with the control group. | High (Soccer-group training39 42) | High quality qualitative evidence that group running, soccer and indoor group exercise and moderate quality qualitative evidence that earn-a-bike improves fitness levels. This is supported by high quality quantitative evidence that soccer improves cardiovascular fitness and endurance. |

| Positive changes to cardiovascular fitness, measured using yo-yo endurance test | Endurance was improved by 45% which was 81 s (1034±218 to 1116±225 s, 95% CI: 47 to 128) s after 12 weeks. This change was significantly different (p=0.05) in the intervention group compared with the control group. | High (Soccer-group training39) | ||||

| Positive changes to cardiovascular fitness, measured using submaximal treadmill exercise test | There was a significant pre-post difference in maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 peak) in the intervention group (p≤0.05). No between group comparison was available. | Low (Indoor group aerobic-based dance)56 | ||||

| Physical skill development | Moderate (Group Outdoor adventure35) Low (Soccer-group training43) Very low (Group instructor-led dance31) |

No changes to postural balance, assessed by single legged flamingo balance test | Postural balance increased by 39% (p=0.004) and by 46% (p=0.006) in the right and left leg respectively in the intervention group only but no there was no difference between pre-post intervention changes in postural balance between intervention and control groups | High (Soccer-group training41) | Moderate quality qualitative evidence that group outdoor adventure improves physical skill development, this was not backed up by quantitative findings among a soccer cohort. | |

| Belief that participating in physical activity interventions makes people experiencing homelessness more active in general | Participating in the physical activity intervention increased physical activity in everyday life | High (Running groups,38 Indoor group instructor-led exercise36) Moderate (Earn-a-bike48) Low (Soccer-group training43) |

Positive changes to physical activity levels, as measured by accelerometry | Min/day of moderate and vigorous physical activity was greater among participants in the intervention group (median 60 min/day) compared with the control group (median 41 min/day) (p=0.00036) | Moderate (Pedometer with step-count32) | High quality qualitative evidence that group running and indoor group exercise and moderate quality qualitative evidence that Earn-a-bike can positively influence physical activity levels among intervention participants. This is supported by moderate quality quantitative evidence that a pedometer with step-count goal significantly increased moderate/vigorous minutes per day of physical activity per day. |

| Broader aspects of the intervention (clothes, equipment, skill) facilitated physical activity participation | High (Running groups38) Very low (Group instructor-led dance31) |

|||||

Table 4.

Outcomes where quantitative only or qualitative only findings exist, no mixed-methods synthesis

| Qualitative findings | ||

| Theme | Subtheme | Level of confidence in evidence for intervention type |

| Belief that the benefits of physical activity interventions carry into wider life of people experiencing homelessness | Development of life and interpersonal skills | High (Group running,38 Group outdoor adventure46) Moderate (Soccer-tournament participation,33 Earn-a-bike,48 Group outdoor adventure35) Low (Soccer-group training and tournament participation,45 soccer-group training,43 Gardening group47) Very low (Group instructor-led dance31) |

| Improved social connection and building relationships with others | High (Group running,38 Group outdoor adventure46) Moderate (Soccer-tournament participation,33 Earn-a-bike,48 Group outdoor adventure35) Low (Soccer-group training and tournament participation,45 soccer-group training,43 Gardening group47) |

|

| Physical activity as a catalyst for positive healthy life change | High (Group outdoor adventure46) Moderate (Soccer-tournament participation33) Low (Soccer-group training and tournament participation,45 Gardening group47) |

|

| Practical and functional benefits developed from participation | Moderate (Earn-a-bike48) Low (Soccer-group training and tournament participation,45 soccer-group training43) |

|

| Perception of challenges related to physical activity participation while homeless | Homelessness presents specific barriers to PA participation | High (Group running38) Moderate (Earn-a-bike48) Low (Soccer-group training and tournament participation,45 soccer-group training43) Very low (Group instructor-led dance31) |

| Participating in soccer tournaments can be stressful | High (Soccer-group training and tournament participation44) Moderate (Soccer-tournament participation33) |

|

| Perceived poor performance/aptitude can negatively impact confidence and coping | High (Soccer-group training and tournament participation44) Moderate (Soccer-tournament participation33) Very low (Group instructor-led dance31) |

|

| Belief of physical activity positive impact on self-medication, prescribed medication and addiction for people experiencing homelessness | Reduction in need for prescription medication and self-medication | Moderate (Earn-a-bike48) |

| Reduced substance misuse | High (Soccer-group training and tournament participation44) Moderate (Earn-a-bike48) Low (soccer-group training43) |

|

| Diversion from temptation of addiction | Low (soccer-group training43) | |

| Quantitative findings | ||

| Description of outcome and measurement tool | Outcome data | Level of confidence in evidence for intervention type |

| Positive bone health, measured from a blood sample and X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in context of physical activity participation in people experiencing homelessness | Osteocalcin increased by 27% from pre to post intervention. This change was significantly different between the control and intervention groups (p=0.042) | High (Soccer-group training41) |

| Pre-post trunk bone mineral density increased by 1% (p=0.02) in the intervention group. There was no difference between intervention and control groups. | High (Soccer-group training41) | |

| No change to bone health, measured by X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), from participation in physical activity among people experiencing homelessness | Pre-post weight-bearing z-score increased from 0.6±1.1 to 0.7±1.1 (p=0.07) in the intervention group. There was no difference between intervention and control groups. | High (Soccer-group training41) |

| No pre-post changes in TRACP5b (bone resorption), plasma leptin or bone mineral density in intervention group (p>0.05) | High (Soccer-group training41) | |

| Positive changes to blood markers after participation in physical activity among people experiencing homelessness | LDL-cholesterol was lowered by 0.4 mmol/L (95% CI: −0.7 to −0.2; 3.2±1.1 to 2.8±0.8 mmol/L) in intervention group after 12 weeks, this change was significantly different to the control group (p=0.05) | High (Soccer-group training39) |

| HDL:LDL ratio increased by 0.06 (CI: 0.02 to 0.11) after 12 weeks in the intervention group (0.43±0.13 to 0.48±0.19), which was different to the control group (p=0.05) | High (Soccer-group training39) | |

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; PA, physical activity.

Table 5.

Summary of available evidence for physical activity interventions categorised by intervention type, findings and evidence quality

| Theme | Subtheme | Soccer | Group outdoor exercise | Group indoor multimodal | Individual multimodal | |||||||

| Group training | Tournament | Training + Tournament | Outdoor adventure | Running | Gardening | Instructor-led dance | Instructor-led exercise | Aerobic-based dance | Pedometer + step count | Earn-a-bike | ||

| Mental health | Self-development and coping |

|

|

† † |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Independence, focus, personal development/relationships |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Feeling better mentally |

|

|

† † |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Physical health | Improved body shape/weight |

* * |

|

|

||||||||

| Physical condition (fitness and physical skill levels) |

* * |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Become more physically active |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Improved bone health |

|

|||||||||||

| Improved blood markers—cholesterol |

|

|||||||||||

| Wider life benefits | Interpersonal skills and social connectedness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Catalyst for healthy life |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Practical and functional (employment/education/travel) |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Medication/self-medication/addiction | Reduced need for prescribed medication |

|

||||||||||

| Positive impact on addiction issues |

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Challenges associated with participation | Homeless lifestyle a barrier to participation |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Tournament participation can increase stress |

|

|

||||||||||

| Poor performance negatively impacts sense of self |

|

|

||||||||||

Very low quality evidence.

Very low quality evidence.

Low quality evidence.

Low quality evidence.

Moderate quality evidence.

Moderate quality evidence.

High quality evidence.

High quality evidence.

Qualitative evidence.

Qualitative evidence.

Quantitative evidence.

Quantitative evidence.

*Additional qualitative evidence, but of lower quality.

†Additional quantitative evidence, but of lower quality.

The impact of physical activity interventions on the mental health of PEH

There were several domains within mental health where both quantitative and qualitative evidence was synthesised, suggesting physical activity was beneficial (summarised in table 2). These included enhanced confidence, empowerment and self-esteem; resilience, coping and hope; independence, self-regulation and personal development; stress and anxiety; and mood and state of mind.

Enhanced confidence, empowerment and self-esteem

There was high quality qualitative evidence that group running, soccer and indoor group exercise, and moderate quality qualitative evidence that group outdoor adventure and earn-a-bike enhanced confidence, empowerment and self-esteem. However, the only quantitative study to assess outcomes in this domain used the Hope scale (agency subscale), finding no significant differences between groups. One soccer player suggested:

… Football gave me confidence and took away feelings of depression as it made me more social.44

Resilience, coping and hope

There was high quality qualitative evidence that group running, and group outdoor adventure enhanced resilience, coping and hope. However, the only quantitative study to measure relevant outcomes using the Hope Scale (pathway domain) found no significant difference between intervention and control groups. A member of staff involved in delivering group outdoor adventure described changes in a participant’s ability to cope:

… when we went to Coniston, not even 10 min, we was there she wanted to come home, but she didn’t and she learned how to cope… she really enjoyed herself.35

Independence, self-regulation and personal development

Qualitative evidence suggested that group running, and soccer (both high quality) and group outdoor adventure and earn-a-bike (both moderate quality) enhanced independence, self-regulation and personal development. This was supported by moderate quality quantitative evidence that outdoor adventure improved life functioning. An outdoor adventure participant describes how it impacted them:

when I leave here, I face any challenges… in my life, then I know that I will be able to do them because I’ve become a stronger person from coming here.35

Stress and anxiety

There was high quality qualitative evidence that group running, indoor group exercise and outdoor adventure and moderate quality qualitative evidence that soccer and earn-a-bike had a positive effect on stress and anxiety. The studies that used quantitative measures to assess stress/anxiety in soccer (moderate quality) and indoor group exercise (low quality) did not conclusively support the qualitative evidence. A participant at a gym-based programme said:

I… didn’t have the confidence to go outside, I felt a lot of like anxiety and this, the gym and stuff helps me with my anxiety really well.36

Mood and state of mind

There was high quality qualitative evidence that soccer, group running and indoor group exercise and moderate quality qualitative evidence that earn-a-bike enhanced mood and state of mind. This was supported by moderate quality quantitative evidence that group outdoor adventure improved well-being.

The impact of physical activity interventions on the physical health of PEH

Changes were shown in the following physical health domains: body shape and weight loss; fitness levels; physical skills development and physical activity levels. The synthesised findings are summarised in table 3. Quantitative findings not corroborated by qualitative findings are summarised in table 4.

Body shape and weight loss

Synthesised findings showed that indoor group exercise and group running (both high quality qualitative evidence) were perceived as improving body shape and facilitating weight loss, while soccer was shown to significantly decrease weight-bearing fat mass and total fat mass (high quality quantitative evidence).

I took my measurements when I started street fit, and I took my measurements now, and I’m a lot more buff.36

Fitness levels

Synthesised findings for fitness levels showed that group running, group indoor training and earn-a-bike (all high-quality qualitative evidence) significantly improved fitness and endurance levels, a finding backed up by a high-quality quantitative study of soccer. A person who cycled with earn-a-bike described trying to increase fitness:

… after riding, you know, for an hour, two hours, and sometimes I’ll ride for four hours. You know, I really want to make sure that my body is fit.48

Physical skill development

While moderate quality qualitative evidence for group outdoor adventure was suggestive of positive changes in physical skills development, the quantitative research exploring this domain through measuring postural balance showed no significant difference between intervention and control groups. However, when comparing pre to post values in the intervention group, postural balance improved by 39% (p=0.004) in the right leg and 45% (p=0.006) in the left leg.

Physical activity levels

Synthesised findings showed that group indoor exercise and running groups (both high quality qualitative evidence) and earn-a-bike (moderate qualitative evidence) positively influenced physical activity levels. This was supported by a moderate quality quantitative pedometer and set a step count study. A woman from a running group described how since joining the group she now runs on her own:

I feel so much more body confident … I can actually run for the whole session without nearly dying. I also go out for runs on my own and I definitely think I’ve got faster.38

Bone health and cholesterol

A high quality study measured markers of bone health41 and cholesterol levels39 in PEH who played soccer. Although not all bone markers improved, increases in osteocalcin from pre-intervention to post-intervention were reported and this change was significantly different between controls and intervention groups. With regards to cholesterol markers (low-density lipoprotein-lipid (LDL)/high-density lipoprotein (HDL)) cholesterol was lowered and LDL:HDL ratios increased in the intervention group after 12 weeks of soccer—findings which were significantly different (p=0.05) from the control group.

Other considerations relevant to physical activity interventions for PEH

There were some findings relevant which described the impact of physical activity for PEH described in qualitative literature only. Themes include addiction, self-medication and medication; benefits carried into wider life and challenges to participation in physical activity when homeless (outlined in table 4).

Addiction, self-medication and medication

Across several qualitative studies of soccer (high quality) and earn-a-bike (moderate quality), physical activity positively influencing addiction was described. One person who played football stated:

I’m drinking less and do not think I need alcohol as much now… It’s great to feel this way and football is a focus for us.44

Benefits of physical activity participation carried into wider life

Most of the qualitative studies, including soccer, running groups, earn-a-bike, outdoor adventure, gardening and dance, described benefits to wider life. Subthemes included: development of life and interpersonal skills, improved social connectedness and relationships with others, practical and functional benefits, and physical activity as a catalyst for positive healthy life change. A participant who undertook leisure centre-based group indoor training said:

I’ve noticed a massive improvement in my fitness, and it’s definitely keeping me motivated to live a healthy lifestyle, because you don’t put in all that hard work and then want to ruin it, you know what I mean?36

… and similarly, how a participant of soccer described life change:

We can go back there and show that homelessness isn’t permanent and that you can change your life through sports.33

Challenges to participation in physical activity when homeless

Qualitative evidence demonstrated the importance of acknowledging specific challenges related to physical activity PEH faced, which impacted uptake and dropout rates across a variety of interventions. Those who participated in soccer tournaments described heavy defeats impacting on self-worth.44 Women who participated in running groups described lack of funds for transport or the unpredictability of homelessness as a barrier to attending.38 There was also worry about loss of donated kit (eg, running clothes)38 and equipment (eg, bicycle)48 through theft and staff who led dance groups reported inconsistent attendance among shelter-dwellers.31

An overall summary of available evidence for physical activity interventions categorised by intervention type, findings and evidence quality is provided in table 5.

Discussion

This review identified evidence for diverse physical activity interventions for PEH. The mixed-methods methodology enabled a meaningfully configured synthesis of the breadth of available evidence. This review demonstrated positive impacts of physical activity for PEH in relation to mental and physical health outcomes with translation of benefits to wider life.

Physical activity interventions were heterogeneous, grouped into broad categories of soccer, group outdoor exercise, group indoor multimodal exercise and individualised multimodal interventions. In terms of specific sports, soccer predominated (7/17). This is unsurprising considering its global resonance.37 The mental health benefits of physical activity participation identified in our review align with research carried out in non-homeless populations, for example, the psychological state of ‘flow’ (where a person feels simultaneously cognitively efficient, motivated and happy) has been found to be increased by soccer training and running.49 However, the majority (4/7) of soccer interventions included in our review included tournament participation. While benefits to tournament participation exist, negative experiences of pressure and fear of letting down teammates were qualitatively reported. Organisers of soccer tournaments for PEH should consider support to ameliorate impacts of possible pressure experienced, which could negatively impact mental health or self-management of addiction. Moreover, our review highlights that comparing the nuances of benefits and challenges of tournament participation and training warrants further research.

Group exercise appeared to be most beneficial for PEH. It is likely that group activities facilitated social support, which is especially pertinent for PEH whose social networks are often fragmented.50 Configured qualitative and quantitative findings highlighted most evidence for mental health benefits in group outdoor exercise. Specifically, these benefits related to an improvement in mood and state of mind and increased independence, focus, personal development and ability to foster relationships. This may be related to emerging evidence for optimised benefits of outdoor exercise.51 Corroboration of qualitative and quantitative evidence indicated that PEH who participated in physical activity interventions increased their physical activity levels. There is inherent difficulty comparing types of interventions for levels of benefit, as interventions and outcome measures were heterogeneous. Many physical activity interventions included additional intervention components such as counselling, food or sports kit. Consequently, it is not known if these additional components, enhanced or diluted the effect of physical activity. Moreover, descriptions of physical activity programme variables such as dosage were often lacking, limiting judgment of interventions.

Programme intensity deserves consideration. Soccer, which predominated, is a vigorous intensity sport (10 metabolic equivalent of task (METs) for competitive soccer and 7 METs for casual soccer)52 so it is likely this high entry level may be exclusionary for some PEH. It should also be considered that some participants may be content to participate on the field while exerting minimal energy, so a diversity in intensity levels is also possible. Given the high prevalence and early manifestation of non-communicable diseases and poor general physical health in many PEH,53 specifically focused lower threshold physical activity interventions should be also considered. Some low threshold programmes were identified such as gardening and dance. People designing physical activity interventions for PEH should consider a range of abilities and likely poor physical condition, perhaps offering a choice of low threshold activity, as well as higher intensity options, depending on ability and interest.

Qualitative studies dominated the evidence base, justifying the methodological decision of a mixed-methods review. The quality of evidence of most qualitative studies was judged to be high, with perspectives of staff enhancing credibility to the understanding of intervention impact. Significant changes were reported for the outcomes of weightbearing fat mass and overall fat mass in one soccer study,41 although changes in muscle mass were not reported. Cardiovascular fitness and endurance also improved significantly in soccer studies.39 42 While these findings were in small, uncontrolled studies, the implication of even minor changes to outcomes such as cardiovascular fitness and endurance may be of importance to PEH, as this group is significantly more likely than housed people to be hospitalised due to acute trauma.54 Although not specifically explored in this population, it is likely that higher baseline fitness and strength levels may aid recovery post-hospitalisation, so multifaceted programmes addressing cardiovascular endurance and strength may be most beneficial for this population. A limitation of the evidence identified was that only one quantitative study was an RCT. While RCTs are considered the highest evidence level, this review attests to the usefulness of other study designs in this novel and emerging topic. It is acknowledged that RCTs may be especially difficult to undertake due to possible implementation barriers and complexities within this cohort. We propose that to build the evidence base, forms of controlled trials should be conducted where possible, with a view to including more randomised trials in the future. A further limitation was that feasibility outcomes such as adherence and retention rates were not well described, though challenges to participation were described in several qualitative studies. Feasibility analysis, including assessment of adherence and retention, should be included in future studies. Outcome measures employed were not consistent, for example, cardiovascular fitness was measured in three different ways: the Yo-Yo endurance test, cycle ergometry and maximal treadmill testing. The evidence base is limited in terms of the most suitable outcome measures55 to use in physical activity interventions for PEH. Future studies should explore the most suitable outcome measures with a view to improving consistency in their use to enable future evidence syntheses.

Strengths of this review were its mixed-methods design and the global spread of identified research including studies from the UK and Europe, North America and Australia. However, only high-income countries were included, as low-income and middle-income settings were considered to have different structural influences on homelessness. So a limitation of this systematic review is that the translation of findings to other settings is not known. With regards to descriptions of exclusion criteria, included studies appeared to be pragmatic with minimal reporting of these. For example, no studies listed addiction status or gender diversity as pre-specified barriers to inclusion. Notably, most studies described the outcomes of ‘real world’ established programmes for PEH. In these cases, study eligibility criteria were dependent on those who engaged with the specific programme in the first instance, the eligibility criteria for which were not described, and were most likely self-selection. Only a small number of drop-outs were reported and there was minimal detail about their characteristics. We recognise that a level of stability in addiction and overall socioeconomic status is required to enable engagement in any type of physical activity intervention. Consequently, conclusions drawn from our review may not be applicable to the full diversity of PEH.

A final strength was that the review team capitalised on expertise in inclusion health, physical activity interventions and evidence synthesis with input from expert medical librarians. Studies were quality assessed using a consistent ‘family’ of critical analysis tools from JBI.

Conclusion

This mixed-methods systematic review demonstrates the value in exploring literature across a wide variety of methodological domains to gain insights into the existence and impact of a variety of physical activity interventions for PEH. To confidently inform policy, more research in this topic is required, however, from a practice and research perspective, our results provide initial justification for the inclusion of this typically under-represented group in targeted physical activity interventions with benefits to multiple aspects of physical and mental health, and positive translation into wider life demonstrated. Future research should include larger-scale high quality quantitative research to provide more robust evidence regarding objective impact.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jacqui Smith, clinical librarian at UCL for sharing her extensive knowledge and supporting the team with their protocol design, searching strategy and carrying out the searches. Thanks also to and David Mockler, librarian, Trinity College Dublin, Dr Cliona Ni Cheallaigh and Professor Andrew Hayward for their advice and support of this work.

Footnotes

Twitter: @DawesJo

Contributors: JFD, RR-W and JB all contributed to the planning, conduct and reporting of the work described in the manuscript. JFD is responsible for the overall content as guarantor. JFD and RR-W designed and contributed to the initial registration of the research and the identification of literature at the search stage. JFD, RR-W and JB all contributed to the screening, data extraction and reporting. All authors contributed to the writing up, review, editing and finalising of the manuscript.

Funding: JFD was funded by a pre-doctoral fellowship from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) School for Public Health Research (SPHR), Grant Reference Number PD-SPH-2015. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Marmott M, Wilkinson RG. Social Determinants of Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Straaten B, Rodenburg G, Van der Laan J, et al. Changes in social exclusion indicators and psychological distress among homeless people over a 2.5-year period. Soc Indic Res 2018;135:291–311. 10.1007/s11205-016-1486-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shinn M. Homelessness, poverty and social exclusion in the United States and Europe. Eur J Homelessness 2010;4:19–44. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Edgar B, Meert H, Docherty J. European Observatory on Homelessness: Third Review of Statistics on Homelessness in Europe. Developing and Operational Definition of homelessness. European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless (FEANTSA), 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fitzpatrick S, Bramley G, Johnsen S. Pathways into multiple exclusion homelessness in seven UK cities. Urban Studies 2013;50:148–68. 10.1177/0042098012452329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shelter . 280,000 people in England are homeless, with thousands more at risk. Shelter; 2019. Available: https://england.shelter.org.uk/media/press_release/280,000_people_in_england_are_homeless,_with_thousands_more_at_risk [Accessed 19 Oct 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ministry of Housing CLG . Investigation into the housing of rough sleepers during the COVID-19 pandemic. National Audit Office; 2021. 4–31. [Google Scholar]

- 8. OECD . Better data and policies to fight homelessness in the OECD, policy brief on affordable housing. Paris: OECD; 2020. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet 2014;384:1529–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arnold EM, Strenth CR, Hedrick LP, et al. Medical Comorbidities and medication use among homeless adults seeking mental health treatment. Community Ment Health J 2020;56:885–93. 10.1007/s10597-020-00552-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Armstrong M, Shulman C, Hudson B, et al. Barriers and facilitators to accessing health and social care services for people living in homeless hostels: a qualitative study of the experiences of hostel staff and residents in UK hostels. BMJ Open 2021;11:e053185. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018;320:2020–8. 10.1001/jama.2018.14854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kiernan S, Ní Cheallaigh C, Murphy N, et al. Markedly poor physical functioning status of people experiencing homelessness admitted to an acute hospital setting. Sci Rep 2021;11:9911. 10.1038/s41598-021-88590-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rogans-Watson R, Shulman C, Lewer D, et al. Premature Frailty, geriatric conditions and multimorbidity among people experiencing homelessness: a cross-sectional observational study in a London hostel. HCS 2020;23:77–91. 10.1108/HCS-05-2020-0007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lewer D, Aldridge RW, Menezes D, et al. Health-related quality of life and prevalence of six chronic diseases in homeless and housed people: a cross-sectional study in London and Birmingham, England. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025192. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kiernan S, Mockler D, Ní Cheallaigh C, et al. Physical functioning limitations and physical activity of people experiencing homelessness: a scoping review. HRB Open Res 2020;3:14. 10.12688/hrbopenres.13011.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stern C, Lizarondo L, Carrier J, et al. Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI Evid Synth 2020;18:2108–18. 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bressan V, Bagnasco A, Aleo G, et al. Mixed-methods research in nursing – a critical review. J Clin Nurs 2017;26:2878–90. 10.1111/jocn.13631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. PRISMA . PRISMA 2020 checklist. 2020. Available: https://prisma-statement.org/PRISMAStatement/Checklist [Accessed 28 Oct 2022].

- 21. OECD . Our global Reach- members and partners. 2022. Available: https://www.oecd.org/about/members-and-partners/ [Accessed 28 Oct 2022].

- 22. Pottie K, Mathew CM, Mendonca O, et al. PROTOCOL: a comprehensive review of prioritized interventions to improve the health and wellbeing of persons with lived experience of homelessness. Campbell Syst Rev 2019;15:e1048. 10.1002/cl2.1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vardell E, Malloy M. Joanna Briggs Institute: an evidence-based practice database. Med Ref Serv Q 2013;32:434–42. 10.1080/02763869.2013.837734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hannes K, Lockwood C. Pragmatism as the philosophical foundation for the Joanna Briggs meta-aggregative approach to qualitative evidence synthesis. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:1632–42. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid Synth 2020;18:2127–33. 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Munn Z, Porritt K, Lockwood C, et al. Establishing confidence in the output of qualitative research synthesis: the conqual approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:108. 10.1186/1471-2288-14-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lizarondo LSC, Carrier J, Godfrey C, et al. Chapter 8: mixed methods systematic reviews. In: Aromataris EMZ, ed. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, et al. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev 2017;6:61. 10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Barroso J. Defining and designing mixed research synthesis studies. Res Sch 2006;13:29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Braun V, Clarke V. Can I use TA? should I use TA? should I not use TA? comparing Reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns and Psychother Res 2021;21:37–47. 10.1002/capr.12360 Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/17461405/21/1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Knestaur M, Devine MA, Verlezza B. ''It gives me purpose': the use of dance with people experiencing homelessness'. Ther Recreation J 2010;44:289–301. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kendzor DE, Allicock M, Businelle MS, et al. Evaluation of a shelter-based diet and physical activity intervention for homeless adults. J Phys Act Health 2017;14:88–97. 10.1123/jpah.2016-0343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Peachey J, Lyras A, Borland J, et al. Street soccer USA cup: preliminary findings of a sport-for-homeless intervention. ICHPER-SD J Res 2013;8:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Norton CL, Tucker A, Pelletier A, et al. Utilizing outdoor adventure therapy to increase hope and well-being among women at a homeless shelter. JOREL 2020;12:87–101. 10.18666/JOREL-2020-V12-I1-9928 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Parry BJ, Quinton ML, Holland MJG, et al. Improving outcomes in young people experiencing homelessness with my strengths training for lifeTM (Mst4LifeTM): a qualitative realist evaluation. Child Youth Serv Rev 2021;121:105793. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Malden S, Jepson R, Laird Y, et al. A theory based evaluation of an intervention to promote positive health behaviors and reduce social isolation in people experiencing homelessness. J Soc Distress Homeless 2019;28:158–68. 10.1080/10530789.2019.1623365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Collins J, Maughan RJ, Gleeson M, et al. UEFA expert group statement on nutrition in elite football. current evidence to inform practical recommendations and guide future research. Br J Sports Med 2021;55:416. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dawes J, Sanders C, Allen R. A mile in her shoes': a qualitative exploration of the perceived benefits of volunteer led running groups for homeless women. Health Soc Care Community 2019;27:1232–40. 10.1111/hsc.12755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Randers MB, Petersen J, Andersen LJ, et al. Short-term street soccer improves fitness and cardiovascular health status of homeless men. Eur J Appl Physiol 2012;112:2097–106. 10.1007/s00421-011-2171-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Randers MB, Marschall J, Nielsen T-T, et al. Heart rate and movement pattern in street soccer for homeless women. Ger J Exerc Sport Res 2018;48:211–7. 10.1007/s12662-018-0503-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Helge EW, Randers MB, Hornstrup T, et al. Street football is a feasible health-enhancing activity for homeless men: biochemical bone marker profile and balance improved. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2014;24 Suppl 1:122–9. 10.1111/sms.12244 Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/16000838/24/S1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Randers MB, Nybo L, Petersen J, et al. Activity profile and physiological response to football training for untrained males and females, elderly and youngsters: influence of the number of players. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010;20 Suppl 1:14–23. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01069.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sherry E, Strybosch V. A kick in the right direction: longitudinal outcomes of the Australian community street soccer program. Soccer Soc 2012;13:495–509. 10.1080/14660970.2012.677225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Magee J, Jeanes R. Football’s coming home: a critical evaluation of the homeless world cup as an intervention to combat social exclusion. Int Rev Sociol Sport 2013;48:3–19. 10.1177/1012690211428391 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sherry E. (Re)Engaging marginalized groups through sport: the homeless world cup. Int Rev Sociol Sport 2010;45:59–71. 10.1177/1012690209356988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]