Abstract

Previously using a series of monovalent vaccines, we demonstrated that the optimal method for inducing an antibody response against cancer cell-surface antigens is covalent conjugation of the antigens to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) and the use of a saponin adjuvant. We have prepared a heptavalent-KLH conjugate vaccine containing the seven epithelial cancer antigens GM2, Globo H, Lewisy, TF(c), Tn(c), STn(c), and glycosylated MUC1. In preparation for testing this vaccine in the clinic, we tested the impact on antibody induction of administering the individual conjugates plus adjuvant compared with a mixture of the seven conjugates plus adjuvant, and of several variables thought to augment immunogenicity. These include approaches for decreasing suppressor cell activity or increasing helper T-lymphocyte activity (low dose cyclophosphamide or anti-CTLA-4 MAb), different saponin adjuvants at various doses (QS-21 and GPI-0100), and different methods of formulation (lyophilization and use of polysorbate 80). We find that: (1) Immunization with the heptavalent-KLH conjugate plus GPI-0100 vaccine induces antibodies against the seven antigens of comparable titer to those induced by the individual-KLH conjugate vaccines, high titers of antibodies against Tn (median ELISA titer IgM/IgG 320/10,240), STn (640/5,120), TF (320/10,240), MUC1 (80/20,480), and globo H (640/40); while lower titers of antibodies against Lewisy (160/0) and only occasional antibodies against GM2 are induced. (2) These antibodies reacted with the purified synthetic antigens by ELISA, and with naturally expressed antigens on the cancer cell surface by FACS. (3) None of the approaches for further altering the suppressor cell/helper T-cell balance nor changes to the standard formulation by lyophilization or use of polysorbate 80 had any impact on antibody titers. (4) An optimal dose of saponin adjuvant, QS-21 (50 μg) or GPI-0100 (1000 μg), is required for optimal antibody titers. This heptavalent vaccine is sufficiently optimized for testing in the clinic.

Keywords: Conjugate vaccines, Cancer vaccines, Polyvalent vaccines, Carbohydrates, Synthetic antigens, KLH

Introduction

There is a broad and expanding body of preclinical and clinical studies demonstrating that naturally acquired, actively induced, and passively administered antibodies are able to eliminate circulating tumor cells and micro metastases. Both glycolipid and mucin antigens have been demonstrated to be susceptible targets for antibody-mediated elimination of cancers in experimental animals [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], and cancer patients with natural or vaccine-induced antibodies against GM2 and STn have been reported to survive longer than patients without these antibodies [6, 7], though vaccination with GM2-KLH plus QS-21 failed to prolong disease-free or overall survival in melanoma patients [8]. Induction of antibodies against tumor antigens is more difficult than induction of antibodies against viral and bacterial antigens because most tumor antigens are normal or slightly modified autoantigens and because actively growing tumors may set in motion mechanisms that suppress the anti–cancer cell immune response [9]. Consequently it may be necessary to overcome not only some level of tolerance but also some additional level of active suppression, making the immunization approach critical. We have previously reported the optimal approach for induction of antibodies against gangliosides and a variety of other carbohydrate and peptide antigens in mice and in patients with various cancers. This includes covalent attachment of the tumor antigen to an immunogenic carrier molecule (keyhole limpet hemocyanin [KLH] was the optimal carrier [10, 11]) plus the use of a potent immunological adjuvant. In our previous experience saponin adjuvants such as QS-21 and GPI-0100 were optimal [12, 13].

Due to tumor and host heterogeneity, it is assumed that antibodies against several different antigens will be required for optimal effect [14]. The logical targets for antibody-mediated therapy of cancer are antigens expressed on the cancer cell surface where they are accessible to passively administered or actively induced antibodies. In our experience [15, 16, 17], the most widely and intensively expressed cell surface antigens in cancers of the breast, prostate, and ovary have been the glycolipids GM2 ganglioside, globo H, and Lewisy (Ley), and the mucin antigens MUC1, Tn, STn, and TF. While the glycolipids are held at the cell surface by intercalation of their ceramide moiety into the lipid membrane, Tn, STn, and TF are O-linked to the many serines and threonines that characterize mucins expressed at the cell surface of epithelial cancers. We have previously vaccinated mice with four separate KLH conjugates (2 glycolipid and 2 mucin antigens) plus QS-21 and shown that the antibody response against each of the four antigens was the same whether the conjugates were administered to separate mice, to separate sites in the same mouse, or mixed together and injected to one site [14].

In preparation for clinical trials with a heptavalent KLH-conjugate vaccine we first confirmed that the antibody response in mice against each of the seven antigens is comparable to that with the use of the individual monovalent vaccines. We also tested the impact on antibody titers against the individual antigens and tumor cells expressing these antigens, of several variables that might further augment vaccine immunogenicity. These include (1) vaccine formulation (lyophilization or the use of polysorbate 80), (2) a decrease in suppression or increasing helper T-cell activity (low dose cyclophosphamide or anti-CTLA-4 mAb), or (3) various doses of the two saponin adjuvants we have found previously to be optimal (QS-21 and GPI-0100).

Materials and methods

Adjuvants and chemicals

QS-21 [18] was obtained from Aquila Biopharmaceuticals (Framingham, MA [now Antigenics, New York, NY]), GPI-0100 [19] was obtained from Galenica Pharmaceuticals (Birmingham, AL). KLH was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Cytoxan (25 mg/kg) was purchased from Bristol-Myers Squibb (Princeton, NJ) and injected intraperitoneally (IP) 1 day prior to the first immunization. The 9H10 hamster hybridoma against CTLA-4 [20] was obtained from Dr James Allison (University of California, Berkeley, CA). 9H10 MAb was prepared and purified using a protein A column by Dr Polly Gregor (MSKCC). The reactivity of 9H10 MAb with CTLA-4 was confirmed by strong FACS reactivity against the CTLA-4 positive cell line DT230. Polysorbate 80 was purchased from Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems (Sparks, MD).

Vaccines

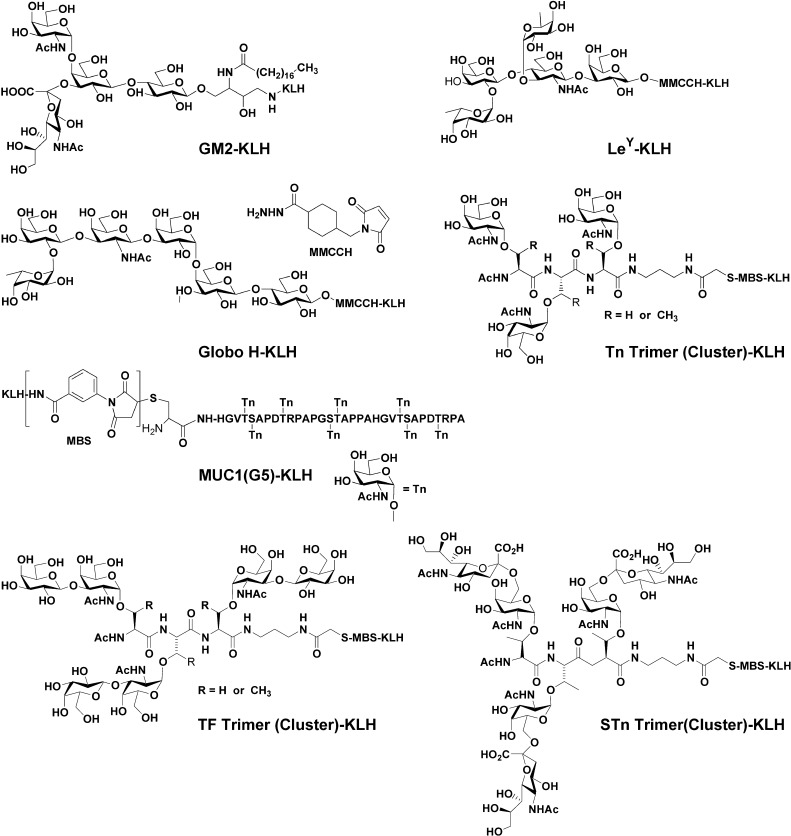

GM1 was extracted from rabbit brain and converted to GM2 by treatment with β galactosidase as previously described [6]. Globo H and Ley were synthesized as allyl glycosides using glycal assembly as previously described [21, 22]. Tn(c), TF(c), and STn(c) were synthesized as individual trimers, conjugated to sequential threonines as previously described [23, 24]. MUC1 peptide containing 1½ repeats (32 amino acids) of the MUC1 tandem repeat was synthesized in a peptide synthesizer with a terminal cysteine for conjugation to KLH [3]. All available serines and threonines were glycosylated with Tn molecules using T2 and T4 acetylgalactosaminyltransferases as previously described [25, 26]. Conjugation to KLH by reductive amination (GM2) or use of heterobifunctional linkers MMCCH (globo H and Ley) or MBS (MUC1, STn(c), TF(c) and Tn(c)) were performed as previously described [3, 10, 21, 22, 23, 24]. Antigen concentration and antigen/KLH epitope ratio were determined using resorcinol to measure sialic acid concentration or high pH anion exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) for globo H, Ley, Tn(c), TF(c) and glycosylated MUC1 concentration. The structures of these seven components are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of antigen used to make heptavalent vaccine

Immunization of mice

Pathogen-free female BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice 6–10 weeks of age were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Groups of five mice were immunized 3 times at 1-week intervals with monovalent or heptavalent vaccines containing 3 μg of each of the seven antigens covalently conjugated to KLH and mixed with QS-21 or GPI-0100 as indicated. Vaccines were administered subcutaneously above the lower abdomen. A fourth booster immunization was given at week 8.

Serological assays

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

For the ELISA assay [3, 10, 22, 27], GM2, glycosylated MUC1, globo H-ceramide, Ley-ceramide, Tn(c)-HSA, STn(c)-HSA, or TF(c)-HSA were coated on ELISA plates at an antigen concentration of 0.1–0.2 μg per well. Serial dilutions of mouse sera were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Phosphatase-conjugated goat antimouse IgG or IgM was added at a dilution of 1:200 (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL). Antibody titer was the highest dilution yielding absorbance at 405 nm of 0.10 or greater. Prevaccination sera were uniformly negative against all antigens and immunization with GM2-KLH served as negative control since fewer than 10% of mice produced detectable anti-GM2 antibody response.

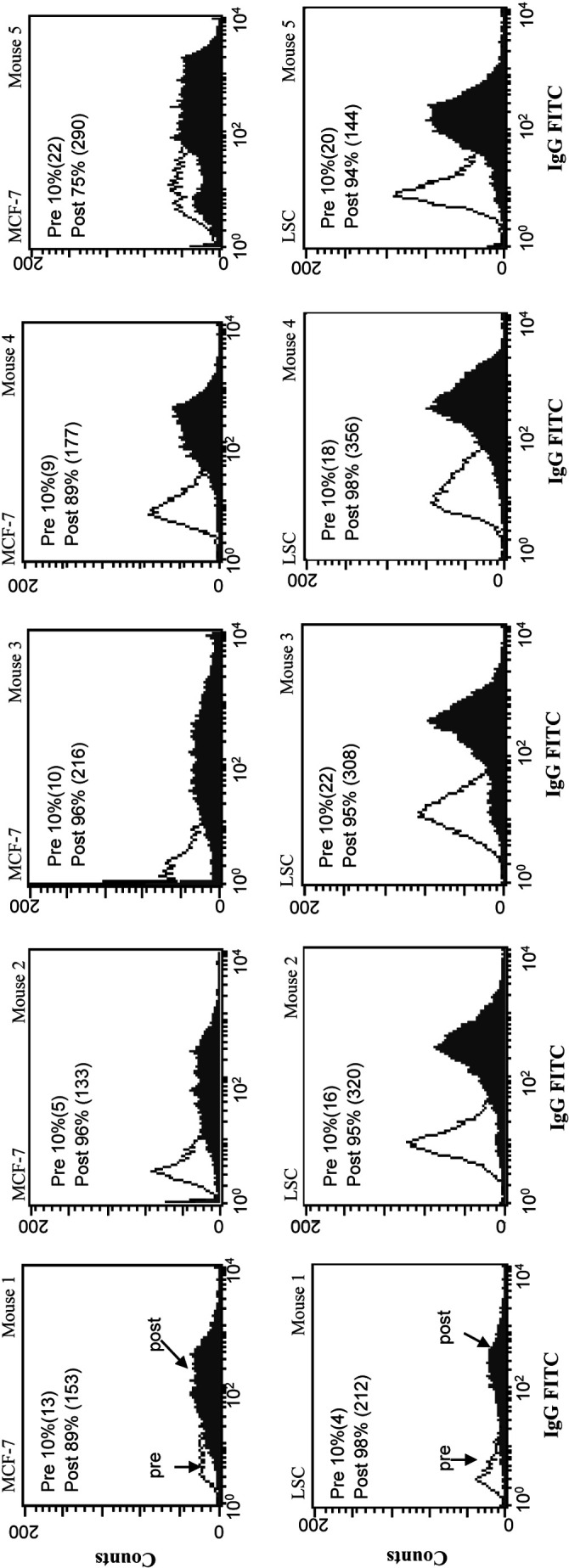

Fluoresence-activated cell sorting (FACS) assay

For FACS analysis [14, 23], MCF-7 human breast cancer cells expressing all seven antigens but especially Ley and MUC1, and LSC expressing especially Ley and STn, were used. Single cell suspensions of 5×106 cells/tube were washed in PBS with 3% fetal calf serum and incubated with 20 μl of 1:20 or 1/200 diluted antisera for 30 min on ice. Twenty five microliters of 1/25 goat antimouse IgG or IgM labeled with FITC were added and percent positive cells and mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of stained cells were analyzed using a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Pre- and postvaccination sera were analyzed together. Prevaccinated sera were used to set the FACScan result at 10% as background for comparison to positive cells with postvaccination sera.

Statistical analysis

A Two Sample Ranks Test was used to determine statistical significance and to estimate the p value when comparing antibody titers in different groups within an experiment [28].

Results

Comparison of heptavalent and monovalent vaccines

ELISA

IgM and IgG antibody titers against the individual antigens by ELISA were comparable in the monovalent- and heptavalent-vaccine-treated mice as summarized in Table 1. As in the past, antibodies against GM2 are rarely induced in mice because GM2 is such a prevalent constituent of normal tissues in the mouse, antibodies against MUC1 are readily induced because human MUC1 is a xenoantigen in the mouse, and responses to the other antigens are in between because they are, it is thought, minimally expressed autoantigens in the mouse.

Table 1.

Comparison of ELISA titers against target antigens and FACS reactivity against MCF-7 and LSC cells after immunization with monovalent and heptavalent vaccines plus 100-μg GPI-0100

| Target (Immunizing Ag) | Vaccine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monovalent | Heptavalent | Monovalent | Heptavalent | |||

| Median ELISA titera | Median % Positive Cells by FACSb | |||||

| IgM/IgG | MCF-7 | LSC | MCF-7 | LSC | ||

| GM2 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Globo H | 2,560/320 | 640/40 | 27 | 7 | ||

| Ley | 80/80 | 160/0 | 67 | 74 | ||

| MUC1-G5 | 160/10,240 | 80/20,480 | 95 | 7 | ||

| STn | 320/5,120 | 640/5,120 | 12 | 97 | ||

| TF | 320/10,240 | 320/10,240 | 10 | 6 | ||

| Tn | 2,560/10,240 | 320/10,240 | 16 | 12 | ||

| Heptavalent FACS | - | - | - | - | 98 | 96 |

aReciprocal median antibody titers in groups of 5 mice (C57BL/6 J) immunized with monovalent or heptavalent KLH-conjugate vaccine plus GPI-0100 (100 μg), IgM/IgG.

bPre- and postvaccination sera were analyzed together, the prevaccinated sera were used to set the FACScan at 10% as a background, and increases in percentage of positive cells were measured with postvaccinated sera at dilutions of 1:20

Flow cytometry using MCF-7 and LSC cells

By IgM FACS, mice immunized with GM2, globo H, and Tn(c) had low antibody responses against MCF-7. Mice immunized with Ley had moderate responses against MCF-7 and LS-C, and mice immunized with MUC1 and STn(c) produced high titers of antibodies against either MCF-7 or LSC respectively. However, all mice immunized with heptavalent vaccine produced high titer antibodies against both cell lines (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

IgG FACS profiles for the 5 mice immunized with heptavalent vaccine plus 100-µg GPI-0100 tested against MCF-7 and LS-C cell lines. % positive cells (MFI)

Impact of vaccine formulation and antisuppressor cell treatments on antibody response

The predominant antibody response against the glycolipids GM2, globo H, and Ley was IgM, while against the mucin antigens it was IgG. As summarized in Table 2, neither vaccine lyophilization, the use of polysorbate 80, pretreatment of the mice with low dose cyclophosphamide (500 μg/mouse) injected intraperitoneally, nor treatment of mice with monoclonal antibody against CTLA-4 by three regimens had any significant impact on ELISA or FACS reactivity. At a dose of 10 μg QS-21 and 100 μg GPI-0100, the resulting ELISA antibody titers were comparable, but cell surface reactivity by FACS was slightly higher with QS-21.

Table 2.

Effect of heptavalent vaccine formulation and antisuppressor cell treatment on ELISA and FACS reactivity in vaccinated mice

| ELISA targets | FACS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM titera | IgG titera | MCF-7 | |||||||

| Heptavalent vaccine plus | GM2 | GloboH | Ley | MUC1-G5 | STn | TF | Tn | % positive cellsb | |

| IgM | IgG | ||||||||

| 10-μg QS-21 | 0 | 640 | 1,280 | 1,280 | 1,280 | 20,480 | 25,600 | 81 | 96 |

| 100-μg GPI | 0 | 160 | 5,120 | 2,560 | 320 | 20,480 | 25,600 | 93 | 96 |

| 100-μg GPI lyoc | 0 | 160 | 640 | 320 | 1,280 | 20,480 | 25,600 | 58 | 92 |

| 100-μg GPI + polysord | 0 | 160 | 1,280 | 2,560 | 1,280 | 20,480 | 25,600 | 91 | 61 |

| 100-μg GPI + Cy 100-μg GPI + CTLA-4 | 0 | 320 | 80 | 2,560 | 640 | 20,480 | 25,600 | 71 | 91 |

| CTLA-4 in vaccine 100-μg, day 0 | 0 | 160 | 40 | 2,560 | 1,280 | 20,480 | 25,600 | 63 | 91 |

| CTLA-4 in vaccine 100-μg, days 0 and 7 | 0 | 160 | 160 | 5,120 | 2,560 | 20,480 | 25,600 | 85 | 90 |

| CTLA-4 not in vaccine, given IP, days –1, 0, +1 | 0 | 160 | 160 | 2,560 | 640 | 40,960 | 10,240 | 45 | 90 |

aReciprocal median titers in groups of 5 mice(Balb/c) immunized with heptavalent KLH-conjugate vaccines with different adjuvants or formulations or antisuppressor cell treatments

bPre- and postvaccination sera were analyzed together, the prevaccination sera were used to set the FACScan at 10% as a background, and increase percentage of positive cells were measured with prevaccinated sera at dilutions of 1:20 is shown

c lyo lyophilized, polysor in polysorbate 80, CY pretreated with low dose cyclophosphamide (25 mg/kg); CTLA-4 pretreated with MAb 9H10 against cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated antigen 4, GPI semi-synthetic saponin adjuvant GPI-0100

dConcentration of polysorbate 80 is 4 mg/ml

Impact of saponin adjuvant dose on antibody titers

QS-21 doses of 10, 50, and 100 μg were compared with GPI-0100 doses of 10, 100, 500 and 1,000 μg. The optimal QS-21 dose appeared to be 50 μg while the optimal GPI dose appeared to be 1,000 μg (500 µg–1,000 µg). Mice treated with 100 µg QS-21 lost weight and looked sick for 2–3 days. Mice in no other groups showed evidence of toxicity. At these optimal doses the median IgM and IgG responses measured by ELISA against the five tested antigens, and by FACS against MCF-7 breast cancer cells at a serum dilution of 1/200, was in every case higher in the GPI-0100 treated mice (see Table 3). The differences achieved statistical significance only for IgM titers against Globo H and STn, and IgG titers against LeY (p<0.05, <0.05, and <0.025, respectively), and by FACS (p<0.05).

Table 3.

Effect of adjuvant dose in heptavalent vaccine on ELISA and FACS reactivity

| Adjuvant dosea | ELISA targets | FACS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Globo H | Ley | MUC1-G5 | STn | TF | MCF-7 | ||

| % Positive cells/MFIc | |||||||

| IgM | IgG | ||||||

| No adjuvant | 40 | 0 | 100 | 40 | 100 | 22/30 | 23/13 |

| QS-21 10 μg | 160 | 80 | 3,200 | 640 | 800 | 76/64 | 97/45 |

| QS-21 50 μg | 320 | 640 | 6,400 | 320 | 3,200 | 93/110 | 95/70 |

| QS-21 100 μgb | 160 | 640 | 6,400 | 1,280 | 1,600 | 95/186 | 95/53 |

| GPI 10 μg | 80 | 40 | 400 | 160 | 200 | 65/60 | 62/15 |

| GPI 100 μg | 160 | 320 | 6,400 | 320 | 3,200 | 90/102 | 93/39 |

| GPI 500 μg | 640 | 2,560 | 6,400 | 640 | 6,400 | 96/146 | 96/97 |

| GPI 1,000 μg | 1,280 | 1,280 | 12,800 | 640 | 6,400 | 96/151 | 98/125 |

aGroups of 5 mice (Balb/C) were immunized subcutaneously on days 0, 7, 14, and 56 with KLH conjugate heptavalent vaccine containing 3 μg of each antigen plus the indicated adjuvant and dose

bMice looked poorly and lost weight for several days after each vaccination

cPre- and postvaccination sera were analyzed together, the prevaccination sera were used to set the FACScan at 10% as a background, and increase percentage of positive cells were measured with prevaccinated sera at dilutions of 1:20 is shown. MFI mean fluorescence intensity of each cell

Discussion

The seven antigen-KLH conjugates in the heptavalent vaccine have each been tested individually with adjuvants QS-21 or GPI-0100 in mice and have each been used to vaccinate cancer patients [6, 11, 22, 29, 30, 31]. Antibody responses against the immunizing antigens (by ELISA) and against cancer cells expressing these antigens (by FACS) have resulted in 80–100% of patients (GM2, STn, MUC1), 50–80% of patients (globo H, Tn, TF), or 30–50% of patients (Ley). Our previous study with a tetravalent vaccine in mice suggested that combination of four antigen-KLH conjugates plus saponin adjuvant in a single injection does not result in any loss of immunogenicity of the individual components [14]. There are however competing factors affecting the antibody response when separate conjugate vaccines using the same carrier are administered as a polyvalent vaccine [32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42]. On the one hand the increased exposure to carrier has been described to result in an amplified population of helper T cells which may result in an increased antibody response against the conjugated antigens [34, 41]. On the other hand, the increased exposure to the same carrier has been described to result in an antibody response against the carrier in some cases which lead to diminished helper T-cell response resulting in a decreased antibody response against the conjugated antigens [32, 33, 37]. Carrier dose may be important here with increasing doses of carrier resulting in increasing antibody responses against carrier and decreasing antibody responses against the conjugated antigens. Antibody responses against the individual antigens in a polyvalent conjugate vaccine may also be decreased due to competition for limited number of carrier specific helper T cells. This phenomenon has been termed epitopic overload [35, 36, 38, 40, 42]. Epitopic overload is also a dose-dependent process with increasing doses of vaccine resulting in increasing overload [39]. For these reasons, as we prepare to immunize patients with this heptavalent vaccine, it was reassuring to confirm that antibody responses against each of the seven antigens after vaccination with the heptavalent vaccine remained undiminished compared with mice immunized with the individual components.

Details of vaccine formulation may play a critical role in overall immunogenicity. It has been our observation as we have tested a series of monovalent vaccines in mice that when the vaccines were lyophilized, there was a higher and more consistent antibody response than when the same vaccines were stored at 4°C or were stored frozen. We theorized that this was due to small aggregates of conjugates or closer adherence of saponin to carrier, resulting in increased immunogenicity. We demonstrate here that at least with regard to the heptavalent vaccine, lyophilization results in no increased immunogenicity compared with vaccine simply frozen at −80°C. Polysorbate 80 has been widely used in vaccines as a solubilizer and stabilizer. We demonstrate here that as with lyophilization, the use of polysorbate 80 has no detectable impact on vaccine immunogenicity. Consequently as polyvalent vaccine is prepared for clinical trials, it will be stored frozen at −80°C (but not lyophilized) and will be formulated in saline without polysorbate 80.

A recurring theme in cancer immunology over the last 40 years has been the balance between suppressor cells and helper T lymphocytes in the cancer-host interaction in general and in the host response to vaccination against cancer in particular. Treatment of the host with low dose cyclophosphamide has been demonstrated to decrease suppressor cell activity and continues to be widely used with various cancer vaccines (reviewed in [43]). A more recent approach is the use of anti–CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody prior to vaccination or tumor challenge [43, 45, 46]. CTL-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) down-regulates T-cell responsiveness. It shares its ligands (CD80 and CD86) with CD28, which is the major costimulatory molecule on T cells [45]. This suggested that treatment with anti–CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody had the potential to augment CD4 positive T-cell reactivity that might in turn result in an increased antibody response. Disruption of this negative regulatory feedback mechanism through CTLA-4 blockade using MAb 9H10 has resulted in effective treatment of cancer in mice [44, 46]. Mice challenged with B-16 melanoma cells and vaccinated with GM-CSF producing B16 tumor cells in combination with MAb 9H10 were protected. When administered in the prophylactic setting, this combination resulted in full protection even in the absence of CD8+ T cells [46]. The protection was mainly mediated by CD4+ T cells, suggesting that combination of anti-CTLA-4 MAb with our conjugate vaccines might result in increased CD4 reactivity against KLH and thus in increased antibody titers. We demonstrated here that with regard to this heptavalent conjugate vaccine administered with saponin adjuvants such as QS-21 or GPI-0100, neither pretreatment with low dose cyclophosphamide nor treatment with anti–CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody resulted in increased antibody responses. Consequently, neither will be utilized as we initiate clinical trials with the heptavalent vaccine.

These results suggest that neither suppressor T cells, epitopic suppression, nor anticarrier antibody levels are interfering with the efficacy of this conjugate vaccine. The basis for this may well be the potency of this vaccination approach that utilizes a carrier and immunological adjuvant each selected as optimal in a long series of studies and trials. In particular, KLH was the most potent carrier of the many we tested [10], and the use of a potent adjuvant such as QS-21 or GPI-0100 resulted in a 1,000–100,000-fold augmentation of antibody responses in the mouse compared with the use of GD3-KLH and MUC1-KLH conjugates with no adjuvant [12, 13]. A 20 to 1,000-fold augmentation of antibody titers is presented here. None of the previous studies demonstrating suppression of antibody responses by anticarrier antibody, epitopic overload, or suppressor T-cell reactivity utilized broadly reactive immunological adjuvants, much less potent adjuvants such as these saponins. Consequently the likely explanation for lack of suppression in our experiments is the use of these saponin adjuvants. We found here that the optimal dose of both saponin adjuvants was higher than initially thought. For QS-21, 50 μg appeared optimal, with 100 μg inducing toxicity and lower antibody titers. For GPI-0100 it was the highest two doses tested, 500 µg and 1,000 μg, that were optimal, and there was no evident toxicity at either dose. The optimal well-tolerated dose of QS-21 in patients is 100 μg [47]. We are currently determining the optimal well-tolerated dose of GPI-0100 in patients. We demonstrated here that once the adjuvant and dose have been determined, this heptavalent vaccine is sufficiently optimized for testing in the clinic.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (PO 1 CA 33049 and 52477), the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and the Danish Cancer Society. C.A.R. was supported by FCT (POCTI/36376/99).

Abbreviations

- Ag

antigen

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen-4

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FACS

fluorescence activated cell sorting

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- GM-CSF

granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor

- HSA

human serum albumin

- IP

intraperitoneal

- KLH

keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- MBS

m-maleimidobenzoyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- MMCCH

4-(4-maleimidomethyl) cyclohexane-1-carboxyl hydrazide

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

Footnotes

Philip O. Livingston is a Paid Consultant and Shareholder in Progenics Pharmaceuticals Inc., Tarrytown, NY 10591, USA and Galenica Pharmaceuticals Inc., Birmingham, AL 35344, USA.

References

- 1.Fung Cancer Res. 1990;50:4308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singhal Cancer Res. 1991;51:1406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Cancer Res. 1996;55:3364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasi Melanoma Res. 1997;7:S155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Cancer Res. 1998;58:2844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Livingston J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1036. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.5.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacLean J Immunother. 1996;19:59. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkwood J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2370. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrone Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:1. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helling Cancer Res. 1994;54:197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helling Cancer Res. 1995;55:2783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim Vaccine. 1999;18:597. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00316-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SK, Ragupathi G, Cappello S, Kagan E, Livingston PO. Effect of immunological adjuvant combinations on the antibody and T-cell response to vaccination with MUC1-KLH and GD3-KLH conjugates. Vaccine. 2000;19:530–537. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ragupathi Vaccine. 2002;20:1030. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00451-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Int J Cancer. 1997;73:42. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Int J Cancer. 1997;73:50. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:2669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kensil J Immunol. 1982;12:91. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marciani Vaccine. 2000;18:3141. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krummel J Exp Med. 1995;182:459. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bilodeau J Amer Chem Soc. 1995;117:7840. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ragupathi Angewandte Chemie. 1999;38:563. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990215)38:4<563::AID-ANIE563>3.3.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ragupathi Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1999;48:1. doi: 10.1007/s002620050542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuduk J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:12474. doi: 10.1021/ja9825128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wandall J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennett J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ragupathi Int J Cancer. 2000;85:659. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000301)85:5<659::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huntsberger DV, Leaverton PE (1970) Measurement data: II. tests for statistical significance. In: Huntsberger DV, Leaverton PE (eds) Statistical inference in the biomedical sciences. Allyn Bacon, Boston

- 29.Adluri Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1995;41:185. doi: 10.1007/s002620050217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilewski Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sabbatini Int J Cancer. 2000;87:79. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20000701)87:1<79::AID-IJC12>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters Infect Immun. 1974;59:3504. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3504-3510.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarvas Scand J Immunol. 1974;3:455. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1974.tb01278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson Infect Immun. 1983;39:233. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.1.233-238.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarnaik Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:181. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199003000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barington Infect Immun. 1993;61:432. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.432-438.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barington Infect Immun. 1994;62:9. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.9-14.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cross J Infect Dis. 1994;170:834. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Insel Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;754:35. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molrine Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:828. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-11-199512010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurika Vaccine. 1996;14:1239. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(96)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fattom Vaccine. 1999;17:126. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(98)00162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bass Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1998;47:1. doi: 10.1007/s002620050498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van J Exp Med. 1995;182:459. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee Science. 1998;282:22263. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sutmuller J Exp Med. 2001;194:823. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Livingston Vaccine. 1994;12:1275. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(94)80052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]