Abstract

Adenovirus vectors delivered to lung are being considered in the treatment of cystic fibrosis (CF). Vectors from which E1 has been deleted elicit T- and B-cell responses which confound their use in the treatment of chronic diseases such as CF. In this study, we directly compare the biology of an adenovirus vector from which E1 has been deleted to that of one from which E1 and E4 have been deleted, following intratracheal instillation into mouse and nonhuman primate lung. Evaluation of the E1 deletion vector in C57BL/6 mice demonstrated dose-dependent activation of both CD4 T cells (i.e., TH1 and TH2 subsets) and neutralizing antibodies to viral capsid proteins. Deletion of E4 and E1 had little impact on the CD4 T-cell proliferative response and cytolytic activity of CD8 T cells against target cells expressing viral antigens. Analysis of T-cell subsets from mice exposed to the vector from which E1 and E4 had been deleted demonstrated preservation of TH1 responses with markedly diminished TH2 responses compared to the vector with the deletion of E1. This effect was associated with reduced TH2-dependent immunoglobulin isotypes and markedly diminished neutralizing antibodies. Similar results were obtained in nonhuman primates. These studies indicate that the vector genotype can modify B-cell responses by differential activation of TH1 subsets. Diminished humoral immunity, as was observed with the E1 and E4 deletion vectors in lung, is indeed desired in applications of gene therapy where readministration of the vector is necessary.

Adenovirus vectors have been used widely in preclinical and clinical applications of gene therapy (21). First-generation constructs with deletions of E1 efficiently transduce a variety of cells in vivo. Therapeutic doses of vector are often associated with inflammation, transient gene expression, and problems with vector readministration. Early experiments in immune-deficient or immune-suppressed animals suggested that these problems may be related to host immune responses (4, 22, 25). Initially, we proposed that cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) in response to the vector-transduced cells contribute to the loss of transgene expression whereas B-cell responses to the input viral capsid proteins elicit neutralizing antibodies which block repeated attempts at gene transfer (24).

The concept of cellular immunity to vector-encoded viral antigens led to the development of a number of advanced-generation adenovirus vectors further disabled by the inactivation of other essential genes. The most extensive experimentation has been in applications of liver-directed gene transfer in murine models, regarding which the literature has been conflicting and somewhat difficult to reconcile. Several themes have emerged, however. It appears that vector-encoded viral proteins as well as the transgene product can serve as targets for CTLs in a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-restricted manner (9, 19, 23). Improvements in transgene stability were modest at best with vectors in which E1 and E2a were defective, although inflammation was substantially diminished (6). Results with constructs from which E1 and E4 were deleted have been more encouraging. Three independent groups have demonstrated marked prolongation of transgene expression in mouse liver with vectors from which E1 and E4 have been deleted, although this advantage was not demonstrated in two other experimental models (2, 5, 9, 14, 20). Studies with vectors with deletions of all viral open reading frames have yielded impressive results in mouse liver, where they are associated with substantially diminished toxicity and extremely stable transgene expression (18). Less impressive results were obtained with an adenovirus vector with deletions of all genes except E4 (15). Modifications in the vector genome described above do not significantly impact the development of neutralizing antibodies, which presumably are elicited by the input viral capsid proteins.

The application to the lung of E1 deletion vectors has confirmed the role of humoral and cellular immunity. Transgene expression is stable and vector readministration is possible in lungs of mice that are genetically immunodeficient or transiently immunosuppressed (24, 25). Further disabling the vector through the incorporation of a temperature-sensitive mutation in E2a resulted in a modest increase in transgene stability in both mice and nonhuman primates (7, 10). Analysis of vectors with deletions of E1 and E4 has been complicated by problems of transcriptional extinction (2). Apparently, ongoing expression of the transgene in mouse lung from a viral promoter such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) requires the presence of E4 viral open reading frames (2). The impact of vector genotype on humoral immune responses is less well characterized in the lung.

In this study, we performed a direct comparison of host immune responses to adenovirus vectors expressing the cystic fibrosis gene with deletions of E1 or of E1 and E4. Comparisons were performed in both C57BL/6 mice and nonhuman primates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were purchased from Taconic Laboratory Animals and Services, Germantown, N.Y., and housed in a specific-pathogen-free environment. Mice were prepared for intratracheal instillation by dissecting the tracheas and directly instilling various concentrations of the vector through small incisions. Animals were sacrificed on days 11 and 29, and spleen, serum, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were obtained for immunological analyses.

Rhesus monkeys were acclimatized for a 4-week period before initiation of experiments. Vector administration (5 × 1012 particles) was performed by bronchoscopy as described previously (10). Monkeys were anesthetized with ketamine and atropine. A physical exam was performed on and a 22-gauge intravenous needle was inserted into each monkey. In the operating room suite, a pulse oximeter was applied and each monkey was placed supine with its head in the “sniffing position.” The vocal cords were visualized with a laryngoscope and sprayed with Cetacaine, and the bronchoscope was passed through the vocal cords and the membranous trachea. The left main stem bronchus was identified and entered under direct vision. Sterile saline (10 ml) was injected into a peripheral branch and aspirated into a mucus trap. Vector (1.75 ml containing 5 × 1012 particles) was instilled into the left main stem bronchus through the biopsy port of the bronchoscope. The bronchoscope was withdrawn under direct vision and the monkey was allowed to emerge from anesthesia. Two animals received the E1 deletion vector and two received an equivalent dose of vector with deletions of E1 and E4. Peripheral blood and BAL fluids were drawn for immunological analyses. One animal from each group was sacrificed on day 11 and day 29. Extensive toxicological analyses of these experiments will be published elsewhere. All animal studies were approved by the University of Pennsylvania, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Institutional Biosafety Committee.

Recombinant adenoviruses.

The structure and production of the vector with the deletion of E1, H5.020CBCFTR, has been described. Basically, the vector expresses a human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) cDNA from a chicken β-actin promoter enhanced by sequences of the immediate early gene of CMV. Sequences spanning E1 and E3 are deleted. The plasmid containing the minigene and 5′ adenovirus type 5 sequences were used to construct H5.001CBCFTR, from which E1 and virtually all of E4 (except orf1) are deleted. To construct H5.001CBCFTR virus, the E1 and E4 double-complementing cells (27-18) were seeded in 60-mm plates and cotransfected with ClaI-digested dl1004 (mutant from which E4 was deleted) viral DNA and NheI-digested pAdCBCFTR plasmid DNA (2 μg of viral DNA and 10 μg of plasmid DNA per plate) by the calcium phosphate precipitation method (9). Twenty hours posttransfection, the cells were overlaid with top agar containing 20 mM dexamethasone to induce expression of E4. Well-isolated plaques were picked 10 days posttransfection following neutral red staining, amplified in 27-18 cells, and screened for recombinant viruses by viral DNA analysis (PCR and restriction endonuclease digestion). Positive plaques were confirmed by infecting HeLa cells with the viral lysates and detecting CFTR protein by immunofluorescent staining. After three rounds of plaque purification, the recombinant viruses were amplified in cells expressing E1 and E4 and purified by standard protocols (9). The CFTR viruses used in these studies were derived from the production lots used in phase I clinical trials. Recombinant adenovirus-expressing β-galactosidase (H5.010CMVlacZ) used for in vitro assays has been described previously (7). Selected in vivo experiments were performed with a CMV-driven lacZ vector with deletions of E1 (H5.000CMVlacZ) or of E1 and E4 (H5.001CMVlacZ) (9).

Lymphoproliferative assays.

Splenocytes from mice or peripheral blood samples from monkeys were obtained on day 11 of each study. Mouse splenocytes were prepared as a single-cell suspension made on a wire mesh following passage through a nylon filter. Rhesus monkey lymphocytes were isolated by standard Ficoll-Hypaque density gradients. Triplicate cultures of lymphocytes (105 cells) were cultured with either inactivated lacZ virus (multiplicity of infection [MOI] based on particles equal to 10) or medium alone. Antigen-stimulated cultures were harvested on day 6. Proliferation was measured by a 16-h [3H]thymidine (1-μCi/well) pulse.

Cytokine release assays.

Lymphocytes were cultured with or without antigen (i.e., inactivated lacZ virus at a particle MOI equal to 10) for 72 h in a 24-well plate. Cell-free supernatants were collected and analyzed for presence of interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and IL-10 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For the mouse cytokine ELISA, 96-well flat-bottomed, high-binding Immulon-IV plates were coated with 200 μl of rat anti-mouse IL-2, IL-4, IFN-γ, and IL-10 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight at 4°C, washed four times in PBS–0.05% Tween, and blocked in PBS–1% bovine serum albumin for 2 h at 4°C. Culture supernatants were added to antibody-coated plates and incubated overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed four times in PBS–0.05% Tween and incubated with biotin-conjugated rat anti-mouse IL-2, IL-4, IFN-γ, and IL-10 (1:1,000 dilution; Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) for 2 h at 4°C. Plates were washed as described above, and peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin was added to the plates for 2 h at 4°C. After another washing, ABTS [2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolesulfonic acid)] substrate (Kirkegaard and Perry, Gaithersburg, Md.) was added. Optical densities were read at 405 nm on a MRX Dynatech Microplate reader. Cytokine secretion in the mouse BAL fluid and culture supernatants of rhesus monkey and mouse lymphocytes was analyzed with commercial ELISA kits for IL-2, IL-4, IFN-γ, IL-10 (BioSource), and IL-8 (R&D Systems).

Cytotoxicity assay.

The CTL assay was performed as described previously (24). In brief, mice were sacrificed on day 11 and a single-cell suspension of spleen cells from groups of three to six mice was cultured for 5 days at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/well in a 24-well plate. Purified lacZ virus was added at an MOI of 0.8. After secondary in vitro stimulation, nonadherent spleen cells were harvested and assayed on MHC-compatible target cells (M57SV) in different ratios of effectors to target cells. Target cells (2 × 106) were infected overnight with adenovirus at a particle MOI of 100. Cells (106) were labeled with 100 μCi of 51Cr (Na251CrO4; NEN Research Products) for 1 h, washed three times with 10 ml of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium, and resuspended in assay medium at 5 × 104/ml. Aliquots of target cells (100 μl) were plated with spleen cells (100 μl) at various effector/target cell ratios in V-bottom microtiter plates. The plates were spun down for 3 min at 1,100 rpm and incubated for 6 h at 37°C in 10% CO2. A 100-μl sample of the supernatant was removed from each well and counted in a Wallach gamma counter. The percentage of specific 51Cr release was calculated as the following: [(cpm of sample − cpm of spontaneous release)/(cpm of maximal release − cpm of spontaneous release)] × 100, where cpm stands for counts per minute. All sample values represent the averages of quadruplicate wells; maximum (i.e., target cells incubated with 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate) and spontaneous (i.e., target cells incubated with medium only) releases were averaged from eight wells.

Neutralizing-antibody assays.

Neutralizing-antibody titers were evaluated by measuring the ability of serum antibody to inhibit transduction of reporter lacZ virus into HeLa cells. Various dilutions of antibodies were preincubated with reporter virus for 1 h at 37°C and added to 90% confluent HeLa cell cultures. Cells were incubated for 16 h and expression of lacZ was measured by X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) staining. The neutralizing titer of antibody was calculated as the highest titer that inhibited transduction to ≤50% of the cells.

Adenovirus-specific Ig.

Serum (diluted 1:200) and BAL fluid (diluted 1:20) from animals were analyzed for adenovirus-specific, isotype-specific immunoglobulins (Ig) (IgM, IgG, IgA, and IgE) by ELISA. For the ELISA, 96-well flat-bottomed, high-binding Immulon-IV plates were coated with lacZ virus (109 particles) in PBS overnight at 4°C, washed four times in PBS–0.05% Tween, and blocked in PBS–1% bovine serum albumin for 2 h at 4°C. Appropriately diluted samples were added to antigen-coated plates and incubated overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed four times in PBS–0.05% Tween and incubated with peroxidase- and biotin-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, or IgA (1:2,000 dilutions; Pharmingen) for 2 h at 4°C. Plates were washed as described above and ABTS substrate (Kirkegaard and Perry) was added. Optical densities were read at 405 nm on an MRX Dynatech Microplate reader.

RESULTS

Adenovirus vectors.

The first-generation adenovirus vector H5.020CBCFTR has been evaluated in mice, nonhuman primates, and humans. It has a deletion of E1 and expresses the human CFTR cDNA from a CMV-enhanced, chicken β-actin promoter. The nonessential gene E3 is also deleted to make room for the CFTR minigene, which is inserted in place of E1. The next generation vector, called H5.001CBCFTR, has deletions of the two essential genes E1 and E4. This is grown in a cell line stably expressing E1 and E4 from an inducible promoter. H5.001CBCFTR is currently being evaluated in a phase I clinical trial.

Clinical-grade production lots of both vectors were made in a pilot manufacturing facility at the University of Pennsylvania that operates under good manufacturing practices. The yields and ratios of PFU to particles were consistently twofold lower for the vector from which E1 and E4 were deleted than for the vector with a deletion of E1. The protein compositions of the resulting virions were indistinguishable in Western blot analyses (data not shown).

Dose-dependent activation of T cells by adenovirus vectors in the mouse.

C57BL/6 mice were intratracheally given various concentrations (i.e., 1.5 × 108 to 5 × 1010 particles) of vectors with deletions of either E1 or E1 and E4. Six animals were given each vector at each concentration. Extensive analyses of cell-mediated immune responses were performed on splenocytes obtained on day 11.

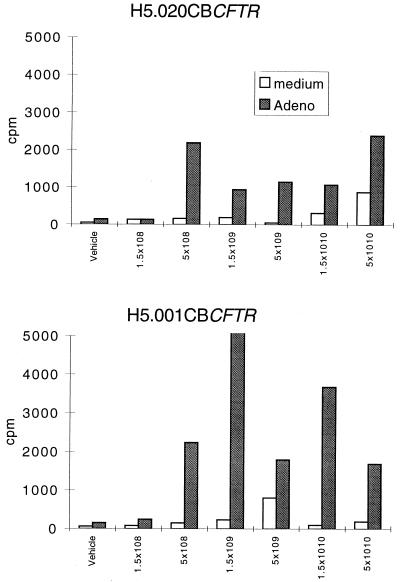

Activation of spleen-derived T cells by vector was characterized in a lymphoproliferation (LPR) assay. This assay represents CD4 T-cell responses, since in vivo administration of a depleting anti-CD4 antibody completely abrogates LPR (data not shown). Figure 1 shows that the administration of at least 5 × 108 particles of the adenovirus vector was required to induce in vitro LPR which was indistinguishable from those of the vectors with deletions of E1 or E1 and E4. Further analyses of activated CD4 and CD8 T cells by three-color flow cytometry showed that animals that were given either vector had equivalent CD69 expression (data not shown). These results indicate that both vectors that were tested are capable of activating CD4 T-cell responses in mice.

FIG. 1.

Threshold of in vivo adenovirus instillation vector required for inducing measurable T-cell proliferative responses. C57BL/6 mice were given vehicle alone or various concentrations of either H5.020CBCFTR or H5.001CBCFTR intratracheally. Splenocytes harvested on day 11 were cultured in the presence or absence of inactivated adenovirus (Adeno) for 7 days. LPR responses were measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation. The results are means of triplicate cultures from spleens of six animals in each group and one of three separate experiments.

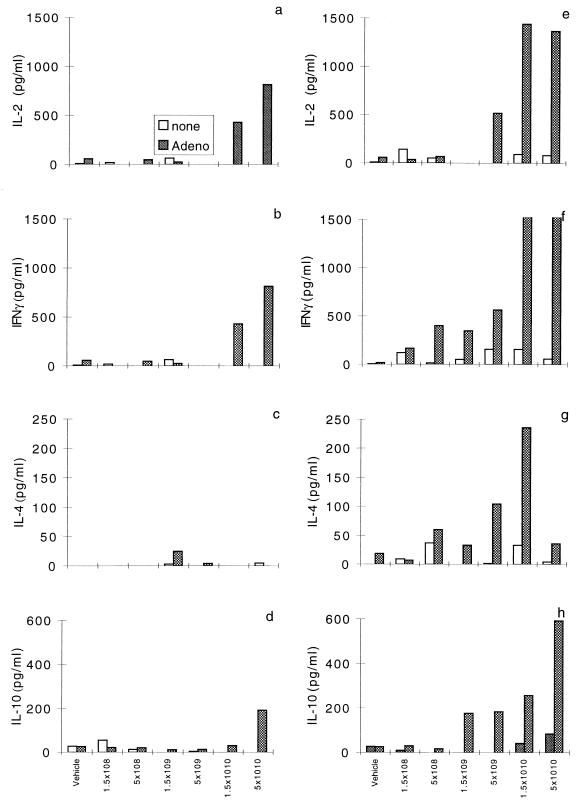

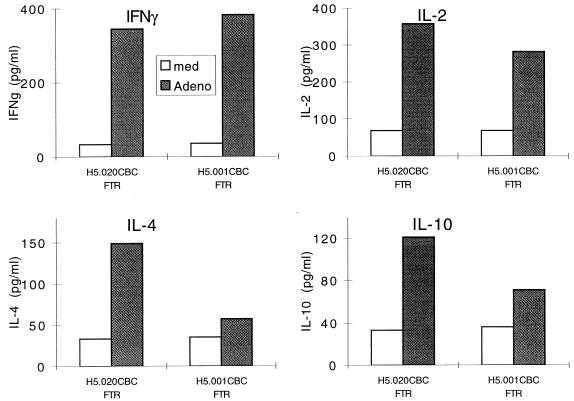

Analyses of the cytokine secretion profiles of activated CD4 T cells showed concentrations of released cytokines that increased in proportion to the concentrations of the administered vectors (Fig. 2). Significant IL-2 and IFN-γ responses were observed with both vectors, although they were attenuated with the construct with deletions of E1 and E4. There was a marked difference in the patterns of TH2 cytokine secretion in animals given the vector with deletions of E1 and E4, which failed to mount appreciable IL-4 and IL-10 responses. This contrasts with the patterns in animals given the E1 deletion vector, which consistently developed IL-4 and IL-10 responses in a dose-dependent manner.

FIG. 2.

Dose-dependent induction of cytokine secretion profile. C57BL/6 mice were given vehicle alone or various concentrations of either H5.020CBCFTR or H5.001CBCFTR intratracheally. Splenocytes harvested on day 11 were cultured in the presence or absence of inactivated adenovirus (Adeno) for 48 h. Culture supernatants were analyzed for IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-10 by ELISA. Panels a to d show cytokines for H5.001CBCFTR vector and panels e to h show cytokines for the H5.020CBCFTR vector. Values are for duplicate culture supernatants from spleens of six animals in each group and one of three separate experiments.

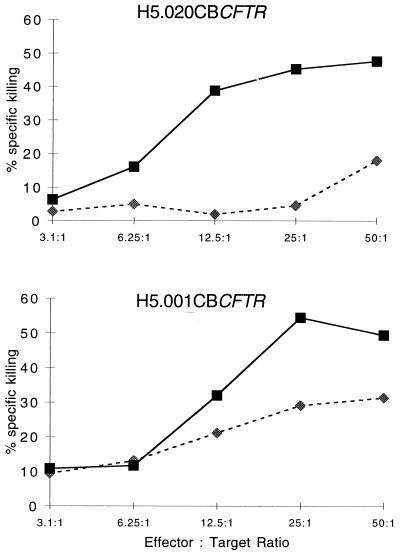

CTL activity against viral proteins has been shown previously to correlate with the elimination of transgene expression (23, 24). Cytotoxic T-cell responses were assessed by the ability of splenocytes to kill adenovirus-infected autologous H-2b target cells. Figure 3 shows that animals given either vector that was tested in this study generated CTL against the vector. Note that this is an assay of bulk-cultured in vitro-stimulated lymphocytes and, therefore, is not necessarily quantitative.

FIG. 3.

CTL responses in mice infected with H5.020CBCFTR and H5.001CBCFTR. C57BL/6 mice were given either H5.020CBCFTR or H5.001CBCFTR intratracheally. Splenocytes harvested on day 11 were cultured in the presence of adenovirus for 5 days and tested for specific lysis on mock-infected or adenovirus-lacZ-infected C57SV target cells in a 51Cr release assay. The percentage of specific lysis is expressed as a function of different ratios of effector cells to target cells. Dashed lines with diamonds indicate values from mock-infected target cells while solid lines with squares indicate values from target cells infected with the first-generation lacZ virus. The results show CTL responses of six spleens in each group and one of three separate experiments.

Deletion of E4 in an adenovirus vector with a deletion of E1 substantially diminishes humoral immune responses in mouse lung.

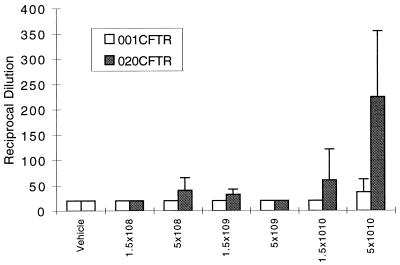

Humoral immune responses following intratracheal administration of vector were analyzed in serum and BAL fluid on day 29. Figure 4 shows that mice instilled with the vector from which E1 was deleted developed neutralizing antibodies in serum in a dose-dependent manner that was substantially blunted in animals given the vector with deletions of E1 and E4. Analysis of BAL fluid on day 29 following the instillation of 5 × 1010 particles revealed reciprocal dilutions of neutralizing antibodies of 340 ± 30 (mean ± standard deviation) with the vector with one deletion and 30 ± 14 with the vector with two deletions. Vehicle control yielded a neutralizing-antibody reciprocal dilution equal to 20.

FIG. 4.

Dose-dependent induction of adenovirus-specific neutralizing antibodies. Day 29 sera obtained from mice given either vehicle or various concentrations of H5.020CBCFTR or H5.001CBCFTR were analyzed for the presence of neutralizing antibody by the ability of sera to block infection of HeLa cells with lacZ virus. The reciprocal dilution is plotted against vector dose. The results represent means and standard deviations of six animals in each group and one of five separate experiments.

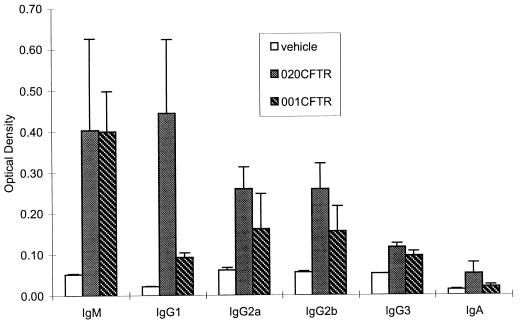

Analyses of the adenovirus-specific Ig isotypes in Fig. 5 showed that both vectors generated levels of IgM and IgG3 equivalent to those generated by adenoviral antigens, both of which are T-cell independent. Substantially more adenovirus-specific TH2-dependent isotype, IgG1, was obtained following exposure to the E1 deletion vector than following exposure to the vector from which E1 and E4 were deleted. The TH1-dependent isotypes IgG2a and IgG2b were generated in essentially equivalent quantities by the two vectors.

FIG. 5.

Anti-adenovirus vector-specific Ig isotypes. Day 29 sera obtained from animals given either vehicle, H5.020CBCFTR, or H5.001CBCFTR were analyzed for the presence of adenovirus-specific IgM, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, IgG1, and IgA by ELISA. The optical densities determined by the ELISAs are presented. The results represent means and standard deviations of six animals in each group and one of three separate experiments.

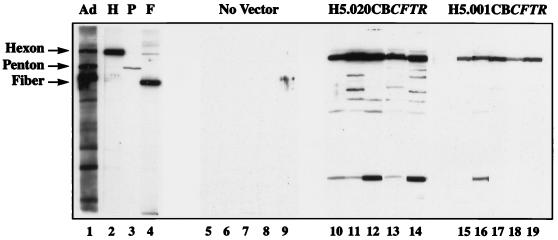

Western blot analyses of adenoviral capsid proteins were performed to determine whether there was preferential induction of antibody responses directed against hexon, penton, or fiber (Fig. 6). Animals given the vector with a deletion of E1 generated antibodies against all three capsid proteins. The vector from which E1 and E4 had been deleted induced primarily antihexon antibodies, weak antipenton antibodies, and no antifiber antibodies.

FIG. 6.

Western blot analyses of sera of mice receiving adenovirus vectors. Day 29 sera obtained from five animals given either vehicle (lanes 5 through 8), H5.020CBCFTR (lanes 10 through 14), or H5.001CBCFTR (lanes 15 through 19) were analyzed for the presence of adenovirus-specific antibodies to hexon, penton, and fiber by Western blot analyses. Control lanes show control polyclonal sera to complete adenovirus (Ad) (lane 1) and polyclonal antibodies to hexon (H) (lane 2), penton (P) (lane 3), and fiber (F) (lane 4). The results represent one of two separate experiments.

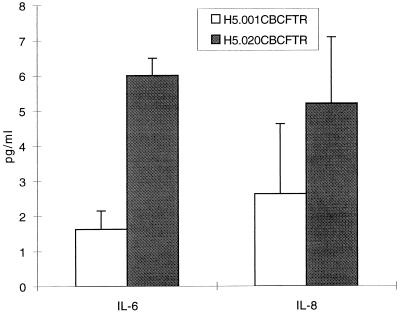

Inflammatory responses following vector administration were analyzed by measuring IL-6 and IL-8 levels in BAL fluid. Figure 7 shows that mice given the vector with a deletion of E1 had significantly higher levels of IL-6 and IL-8 cytokines than animals given the vector with deletions of E1 and E4. No measurable cytokines were detected in BAL fluid from monkeys that had been given vehicle (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Induction of inflammatory cytokines in BAL fluid of mice. BAL fluid obtained from animals given either vehicle, H5.020CBCFTR, or H5.001CBCFTR intratracheally was analyzed for the presence of IL-8 and IL-6 by commercial ELISA kits as recommended by the manufacturer. The results are means and standard deviations of six animals in each group.

Humoral and TH2 responses are substantially diminished in nonhuman primate lungs when E4 is deleted from the first-generation adenovirus vector.

Antigen-specific immune responses to the CFTR adenovirus vectors were analyzed in lungs of rhesus monkeys. A total of four monkeys were studied. Two received the vector with a deletion of E1 and two received the vector with deletions of E1 and E4. Equivalent concentrations of vector were directly instilled into the airways of monkeys with a bronchoscope. Animals from each group were necropsied at days 11 and 29. A report of the clinical and pathological analyses of these animals will be provided elsewhere.

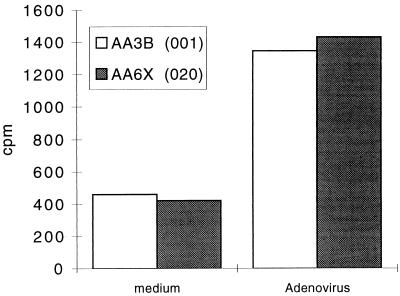

CD4 T-cell responses to adenovirus vector were studied from peripheral blood harvested at day 11. LPR was identical in animals that received either vector (Fig. 8). The vector with one deletion resulted in secretion of TH1 (i.e., IL-2 and IFN-γ) and TH2 (i.e., IL-10 and IL-4) cytokines. The TH1-specific cytokines were retained with the vector with two deletions, although the TH2-specific cytokines (IL-4 and IL-10) were diminished (Fig. 9).

FIG. 8.

Lymphoproliferative responses in rhesus monkeys. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells obtained on day 11 from animals given either H5.020CBCFTR (animal AA6X) or H5.001CBCFTR (animal AA3B) intratracheally were cultured in medium alone or in the presence of inactivated adenovirus for 7 days. LPR responses were measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation and are presented as means of triplicate cultures.

FIG. 9.

Cytokine secretion profiles in rhesus monkeys. Rhesus monkeys were given either H5.020CBCFTR (animal AA6X) or H5.001CBCFTR (animal AA3B) intratracheally. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from heparinized blood on day 11 were cultured in medium alone (med) or in the presence of inactivated adenovirus (Adeno) for 48 h. Culture supernatants were analyzed for the presence of IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-10 by commercial ELISA kits, and results are presented as means of duplicate cultures.

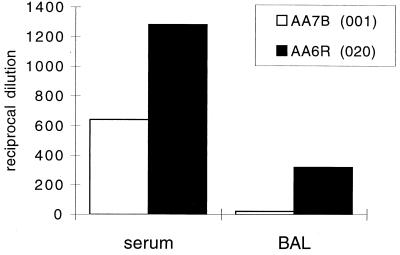

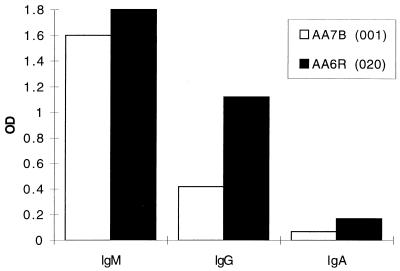

Humoral immune responses following vector administration were analyzed in the serum and BAL fluid obtained on day 29. Animals that were given the vector with a deletion of E1 developed a strong neutralizing-antibody responses both in serum and BAL fluid, whereas those given vector with deletions of E1 and E4 showed a weaker neutralizing-antibody response in the serum and failed to generate neutralizing antibody in BAL fluid, as observed in the studies in mice (Fig. 10). IgM responses to adenovirus were equivalent with both vectors while IgG and IgA responses were weaker in the animal that received the vector with deletions of E1 and E4 (Fig. 11).

FIG. 10.

Neutralizing antibodies in serum and BAL fluid of rhesus monkeys. Day 29 sera and BAL fluid obtained from animals given either H5.020CBCFTR (animal AA6R) or H5.001CBCFTR (animal AA7B) intratracheally was analyzed for the presence of neutralizing antibody by the ability of sera to block infection of HeLa cells with lacZ virus. The reciprocal dilution is presented. The results are means of duplicate wells.

FIG. 11.

Adenovirus-specific Ig in rhesus monkeys. Day 29 sera obtained from animals given either H5.020CBCFTR (animal AA6R) or H5.001CBCFTR (animal AA7B) intratracheally were analyzed for the presence of adenovirus-specific IgM, IgG, and IgA by ELISA. The results denote means of duplicate wells. OD, optical density.

DISCUSSION

Immunologic responses to recombinant adenoviruses have emerged as a major issue in the success of in vivo gene therapy (21). The initial paradigm suggested that the activation of CTLs in response to proteins expressed from the vector genome (i.e., in first-generation constructs this includes products from the transgene and viral genes) and the formation of neutralizing antibodies to the input viral capsid proteins were critical for the transient transgene expression and problems with readministration. The role of CTLs in vector performance for transgene persistence and inflammation has been confirmed in multiple settings. The relative importance of different vector-derived antigens in cellular immunity as well as the contribution of other factors, such as transcriptional inactivation or vector genome instability, is more controversial and is likely to be vector and model specific.

The formation of neutralizing antibodies to viral capsid proteins is a reproducible finding that was present in virtually all models studied. The emergence of neutralizing antibodies to inactivated adenovirus vectors at levels similar to that obtained with an identical dose of infectious virus from which E1 had been deleted suggested that this B-cell response is primarily mediated by MHC class II presentation of capsid proteins from the input vector (24). Our studies implicate factors other than the capsid antigens in modulating the resulting humoral response. Specifically, identical particle quantities of viruses with the deletions described above administered to lung yielded identical LPR and TH1 responses but very different TH2 and B-cell responses. The net effect was substantially diminished production of neutralizing antibody to the vectors with deletions of E1 and E4.

Our findings are consistent with the concept that both the antigen and the context in which it is presented influence immune responses. Activation of naïve T cells requires presentation of antigen by a professional antigen-presenting cell (APC), such as a dendritic cell. Environmental factors, such as the inflammation associated with an infection, trigger key steps in the activation and maturation of the APC to modulate the T-cell response (3, 16). The innate immune system, which is capable of recognizing and responding to infection, may provide a key link to the acquired immune response via the regulation of APCs (8, 11).

How can vector genotype affect the innate immune response and impact antigen presentation? A vector with deletions of E1 and E4 is more attenuated than one with a deletion of E1, which leads to diminished inflammation prior to the development of antigen-specific processes. Relevant to our studies is the observation that the vectors from which E1 and E4 have been deleted induced lower IL-6 and IL-8 levels in BAL fluid than did the vectors with deletions of E1. Previous experiments in mice, in the setting of autoimmune disease and parasitic infections, have demonstrated a critical role of IL-6 in the expression of B7 and in the induction of TH2 responses (12, 17). The E4 gene products are toxic and interfere with a number of cellular proteins involved in the cell cycle and apoptosis (13). One can envision models in which direct transduction of the APC or a bystander effect from a nearby transduced cell could impact antigen presentation.

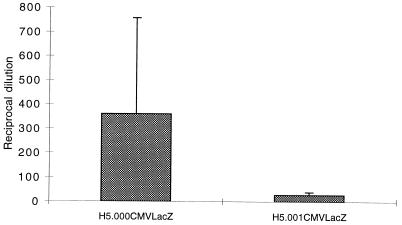

The adenovirus vectors characterized in this study are being or have been evaluated in clinical trials. The vectors differ at the E4 and E3 loci. Introduction of the CFTR minigene into our first-generation construct required the deletion of the nonessential E3 genes to maintain an overall genome length of <105% of wild type. For a variety of reasons, however, we do not believe that E3 genes play a role in the observed effect. In the absence of E1, there is no detectable transcription of E3 from its endogenous promoter. We have in fact evaluated cellular and humoral immune responses to vectors with deletions of E1 which express the smaller transgene β-galactosidase and which differ by the presence or absence of E4. The lacZ vector with a deletion of E1 that contained an intact E3 region generated far less neutralizing antibody after intratracheal administration than did the version from which E1 and E4 had been deleted (Fig. 12). Another question concerns the impact of the host on the differential CD4 T-cell and humoral responses noted in our studies. In fact, qualitatively different T-helper subset responses to pathogens such as Leishmania in different strains of mice have been observed (1). The fact that the E4 effects were observed in multiple strains of mice (H-2b, C57BL/6; H-2d, BALB/c; and H-2k, C3H; data not shown) and in two species (mice and nonhuman primates) suggests that it may have broader implications in gene therapy directed to the lung.

FIG. 12.

Neutralizing-antibody response to lacZ vectors. Day 29 sera obtained from animals given either vehicle H5.000CMVlacZ or H5.001CMVlacZ intratracheally were analyzed for the presence of neutralizing antibody by the ability of sera to block infection of HeLa cells with lacZ virus. The dose of vector was 5 × 1010 particles. The figure shows means for three animals in each group plus standard deviation.

Our studies point out another advantage of using advanced-generation adenovirus vectors with deletions of multiple essential genes. Problems of neutralizing antibody are substantial in applications of gene therapy that require repeated administrations of vectors. It remains to be seen if the advantage afforded by the deletion of E4 is sufficient to enable effective repeated administrations of vector. Administration of a pharmacologic inhibitor of T cells with the vector from which E1 and E4 have been deleted may provide sufficient additive and/or synergistic inhibition of B-cell activation necessary for their repeated use in chronic diseases such as cystic fibrosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

These studies were performed in the context of the Translational Research Program at the Institute for Human Gene Therapy (study numbers 96-20, 96-27, 96-32, 96-39, and 97-11). Support from the Vector and Cell Morphology Cores and the excellent technical help of George Qian and Ruth Qian in the Immunology Core are appreciated.

This work was supported by grants from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, the NIDDK of the NIH (P30 DK47757-05), CFSCOR (P50 DK49136-04), and Genovo, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas A K, Murphy M M, Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature. 1996;383:787–793. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armentano D, Zabner J, Sacks C, Sookdeo C C, Smith M P, St. George J A, Wadsworth S C, Smith A E, Gregory R J. Effect of the E4 region on the persistence of transgene expression from adenovirus vectors. J Virol. 1997;71:2408–2416. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2408-2416.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cella M, Engering A, Pinet V, Pieters J, Lanzavecchia A. Inflammatory stimuli induce accumulation of MHC class II complexes on dendritic cells. Nature. 1997;388:782–787. doi: 10.1038/42030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai Y, Schwarz E M, Gu D, Zhang W W, Sarvetnick N, Verma I M. Cellular and humoral immune responses to adenoviral vectors containing factor IX gene: tolerization of factor IX and vector antigens allows for long-term expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1401–1405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dedieu J-F, Vigne E, Torrent C, Jullien C, Mahfouz I, Caillaud J-M, Aubailly N, Orsini C, Guillaume J-M, Opolon P, Delaère P, Perricaudet M, Yeh P. Long-term gene delivery into the livers of immunocompetent mice with E1/E4-defective adenoviruses. J Virol. 1997;71:4626–4637. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4626-4637.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engelhardt J F, Litzky L, Wilson J M. Prolonged transgene expression in cotton rat lung with recombinant adenoviruses defective in E2a. Hum Gene Ther. 1994;5:1217–1229. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.10-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engelhardt J F, Ye X, Doranz B, Wilson J M. Ablation of E2A in recombinant adenoviruses improves transgene persistence and decreases inflammatory response in mouse liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6196–6200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fearon D T, Locksley R M. The instructive role of innate immunity in the acquired immune response. Science. 1996;272:50–54. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao G-P, Yang Y, Wilson J M. Biology of adenovirus vectors with E1 and E4 deletions for liver-directed gene therapy. J Virol. 1996;70:8934–8943. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8934-8943.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldman M J, Litzky L A, Engelhardt J F, Wilson J M. Transfer of the CFTR gene to the lung of nonhuman primates with E1-deleted, E2a-defective recombinant adenoviruses: a preclinical toxicology study. Hum Gene Ther. 1995;6:839–851. doi: 10.1089/hum.1995.6.7-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janeway C A. Approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. pp. 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenschow D J, Herold K C, Rhee L, Patel B, Kooks A, Qin H-Y, Fuchs E, Singh B, Thompson C B, Bluestone J A. CD28/B7 regulation of TH1 and TH2 subsets in the development of autoimmune diabetes. Immunity. 1996;5:285–293. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leppard K N. E4 gene function in adenovirus, adenovirus vector and adeno-associated virus infections. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:2131–2138. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-9-2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lieber A, He C-Y, Kay M A. Adenoviral preterminal protein stabilizes mini-adenoviral genes in vitro and in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:1383. doi: 10.1038/nbt1297-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lieber A, He C-Y, Kirillova I, Kay M A. Recombinant adenoviruses with large deletions generated by Cre-mediated excision exhibit different biological properties compared with first-generation vectors in vitro and in vivo. J Virol. 1996;70:8944–8960. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8944-8960.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierre P, Turley S J, Gatti E, Hull M, Meltzer J, Mirza A, Inaba K, Steinman R M, Mellman I. Developmental regulation of MHC class II transport in mouse dendritic cells. Nature. 1997;388:787–792. doi: 10.1038/42039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rincon M, Anguita T, Nakamura T, Fikrig E, Flavell R A. Interleukin 6 directs the differentiation of IL-4 producing CD4 T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:461–469. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schiedner G, Morral N, Parks R J, Wu Y, Koopmans S C, Langston C, Graham F L, Beaudet A L, Kochanek S. Genomic DNA transfer with a high-capacity adenovirus vector results in improved in vivo gene expression and decreased toxicity. Nat Genet. 1998;18:180–183. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tripathy S K, Black H B, Goldwasser E, Leiden J M. Immune responses to transgene-encoded proteins limit the stability of gene expression after injection of replication-defective adenovirus vectors. Nat Med. 1996;2:545–550. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Q, Greenburg G, Bunch D, Farson D, Finer M H. Persistent transgene expression in mouse liver following in vivo gene transfer with a delta E1/delta E4 adenovirus vector. Gene Ther. 1997;4:393–400. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson J M. Adenoviruses as gene-delivery vehicles. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1185–1187. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605023341809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y, Nunes F A, Berencsi K, Furth E E, Gonczol E, Wilson J M. Cellular immunity to viral antigens limits E1-deleted adenoviruses for gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4407–4411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, Jooss K U, Su Q, Ertl H C, Wilson J M. Immune responses to viral antigens versus transgene product in the elimination of recombinant adenovirus-infected hepatocytes in vivo. Gene Ther. 1996;3:137–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y, Li Q, Ertl H C J, Wilson J M. Cellular and humoral immune responses to viral antigens create barriers to lung-directed gene therapy with recombinant adenoviruses. J Virol. 1995;69:2004–2015. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2004-2015.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zsengeller Z K, Wert S E, Hull W M, Hu X, Yei S, Trapnell B C, Whitsett J A. Persistence of replication-deficient adenovirus-mediated gene transfer in lungs of immune-deficient (nu/nu) mice. Hum Gene Ther. 1995;6:457–467. doi: 10.1089/hum.1995.6.4-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]