Abstract

Mycobacteria and their cell wall components have been used with varying degrees of success to treat tumors, and Mycobacterium bovis BCG remains in use as a standard treatment for superficial bladder cancer. Mycobacterial immunotherapy is very effective in eliciting local immune responses against solid tumors when administered topically; however, its effectiveness in eliciting adaptive immune responses has been variable. Using a subcutaneous mouse thymoma model, we investigated whether immunotherapy with Mycobacterium smegmatis, a fast-growing mycobacterium of low pathogenicity, induces a systemic adaptive immune response. We found that M. smegmatis delivered adjacent to the tumor site elicited a systemic anti-tumor immune response that was primarily mediated by CD8+ T cells. Of note, we identified a CD11c+CD40intCD11bhiGr-1+ inflammatory DC population in the tumor-draining lymph nodes that was found only in mice treated with M. smegmatis. Our data suggest that, rather than rescuing the function of the DC already present in the tumor and/or tumor-draining lymph node, M. smegmatis treatment may promote anti-tumor immune responses by inducing the involvement of a new population of inflammatory cells with intact function.

Keywords: Mycobacterium smegmatis, Immunotherapy, Dendritic cell, Thymoma, Mycobacteria, BCG

Introduction

In 1891, William Coley pioneered the use of bacteria to enhance anti-tumor immunity, by successfully treating sarcomas with extracts of pyogenic bacteria [1]. Following on from these early observations, mycobacteria and their cell wall components have been used with varying degrees of success to treat melanoma and leukemia as well as bladder, colon, and lung cancers [2]. The complex mycobacterial cell wall is a rich source of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [3]. These cell wall constituents, which include peptidoglycans, arabinogalactans, phosphatidylinositol mannans, lipoarabinomannans, and mycolic acids, have been shown to stimulate pattern-recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleoside-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein-like receptors [4]. Ligation of these receptors activates dendritic cells (DCs), enhancing their ability to present antigen [5]. Once activated by PAMPs, DCs are able to drive enhanced anti-tumor immune responses [6].

Mycobacterium bovis BCG, the live, attenuated tuberculosis vaccine, was first used as a treatment for superficial bladder cancer more than 35 years ago [7] and remains in use as a standard treatment to reduce tumor recurrence and progression as it is more effective than chemotherapy alone [8, 9]. Although it is essential for BCG to have direct contact with the tumor cells to elicit the protective effect [10], there is an appreciable role for DC in modulating [11] or recruiting cells to elicit [12, 13] the anti-tumor effects of intravesical BCG therapy, through the production of cytokines and chemokines [12].

Tumor immunotherapy with other mycobacterial species, including Mycobacterium smegmatis [14], Mycobacterium indicus pranii [15], Mycobacterium obuense [16], and Mycobacterium vaccae [17, 18], has also been effective in pre-clinical and clinical studies. In particular, M. smegmatis, a fast-growing mycobacterium of low pathogenicity, has been shown to be as effective as BCG in several tumor immunotherapy models [14, 19].

Although mycobacterial immunotherapy is clearly effective in eliciting local immune responses against solid tumors when administered topically, its effectiveness in eliciting adaptive immune responses has been variable [2]. Thus, using a subcutaneous mouse thymoma model, we asked whether M. smegmatis immunotherapy induces a systemic adaptive immune response. We found that M. smegmatis must be delivered adjacent to the tumor site to elicit an anti-tumor immune response that is primarily mediated by CD8+ T cells. Of note, we identified an inflammatory DC population in the tumor-draining lymph nodes that was detected only in mice treated with M. smegmatis, which may be important for driving the anti-tumor response.

Materials and methods

Mice

All mice were housed under SPF conditions in the Biomedical Research Unit at the Malaghan Institute of Medical Research, Wellington, New Zealand. Tumor challenge and treatments were conducted in C57Bl/6 or CD45.1+ B6.SJL/PtprcaPep3b age- and sex-matched mice. All experimental procedures were approved by the VUW Animal Ethics Committee and carried out according to Institutional guidelines.

E.G7-OVA tumor model

The mouse thymoma E.G7-OVA [20] was maintained in IMDM supplemented with 5 % fetal calf serum (FCS, PAA Laboratories, Pasching, Austria), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 55 μM 2-ME, and 0.5 mg/mL geneticin (Gibco, Invitrogen, Auckland, NZ). Prior to injection, cells were washed three times, resuspended in IMDM without FCS, and then 5 × 105 cells were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) on the left lower flank.

M. smegmatis treatment

Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155 was gifted by Ronan O’Toole, School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Mice were injected with 2 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU) of M. smegmatis in a 100 μL volume adjacent to the tumor inoculation site, or on the contralateral flank to the tumor where indicated, based on a previously described treatment regimen [14]. The first injection was immediately after tumor challenge and then a further four injections of 2 × 106 CFU were given at the same site 2, 4, 6, and 8 days after the first treatment. Control mice received injections of 100 μL PBS. All peritumoral injections were given under anesthesia. Tumor size was measured using calipers and is expressed as the product of the two perpendicular tumor diameters. Mice were euthanized once tumor size exceeded 150 mm2. Heat-killed M. smegmatis was prepared by incubation at 70 °C for 30 min and was administered in the same way as live M. smegmatis.

Preparation of single-cell suspensions

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from pooled donor spleens by infusion and 30-min digestion with 2.4 mg/mL collagenase type I (Invitrogen) and 100 μg/mL DNase I (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) in IMDM. Digested spleens were passed through 70-μm cell strainers (Falcon, BD, Auckland, NZ), and then red blood cells were lysed using red cell lysing buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, Ayrshire, UK).

Tumor-draining axillary, brachial, and inguinal lymph nodes were harvested at 1, 3, or 8 days after E.G7-OVA injection and commencement of treatments. Lymph nodes were digested in a 30-min enzymatic digestion as described above. Digested lymph nodes were passed over 70-μm cell strainers, washed, and resuspended. Total viable cells were counted using Trypan blue exclusion.

T cell enrichment and adoptive transfers

Washed suspensions were incubated with a cocktail of biotinylated CD11b (M1/70), B220 (6B2), and MHC class II (3JP) mAbs, and then washed and incubated with anti-biotin Dynal beads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Suspensions were depleted of bound cells by 2 incubations of 2 min against a Dynal magnet (Invitrogen). Unbound cells were collected and purity of >70 % CD4+ or CD8+ events was confirmed by flow cytometry. Forty million T cell-enriched splenocytes were given intravenously via the tail vein. In a second experiment, splenocyte suspensions were incubated with cocktails of biotinylated B220, CD11c, CD11b, or B220 and CD8 (2.43) mAbs, and then were magnetically depleted of bound cells as described above. Twenty-five million cells were given to naïve recipients via the tail vein 1 day prior to tumor challenge.

Flow cytometry

Two million lymph node cells were used for staining of cell surface molecules. After incubation with anti-mouse CD16/32 (2.4G2) diluted in FACS buffer (PBS with 1 % (v/v) FCS), cells were labeled with combinations of primary antibodies, as indicated in figure legends, including CD11c (HL3)-PE-Cy7, CD11b (M1/70)-PerCP-Cy5.5, CD8 (53-6.7)-APC-H7, CD86 (GL1)-FITC, CD40 (3/23)-PE, CD103 (M290)-PE, F4/80-biotin, B220 (RA36B2)-Pacific blue (all purchased from DB Biosciences), Gr-1 (RB6-8C5)-APC (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA), Ly6B.2 (7/4)-FITC (Serotech, Kidlington, UK), MHC class II (3JP)-Alexafluor647 or -biotin (prepared in house), and Live/Dead Fixable blue (Invitrogen). Stained cells were fixed in 4 % formaldehyde before resuspension in FACS buffer. At least 30,000 live, CD11c+, MHC class II+ events were collected on a BD LSRII SORP (Becton–Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and were analyzed using FlowJo version 9.3.1 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (La Jolla, CA). p values were determined from the Kaplan–Meier survival curves by use of the log-rank test. Where multiple comparisons were made, probability values were appropriately adjusted.

Results

Peri-tumoral M. smegmatis injections delay tumor growth

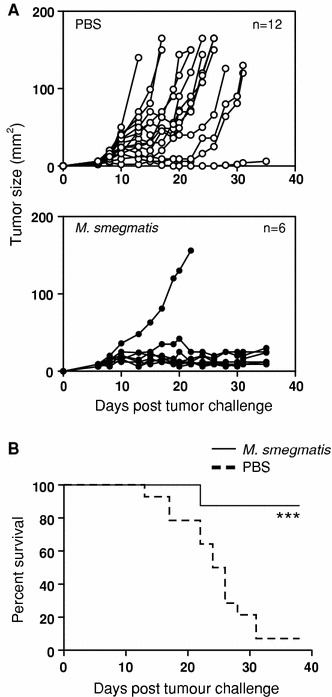

To determine whether M. smegmatis treatment delayed growth of the mouse thymoma E.G7-OVA in vivo, M. smegmatis therapy was initiated at the same time as tumor challenge (day 0). Thereafter, subcutaneous injections of 2 × 106 CFU M. smegmatis were given every 2 days, adjacent to the tumor injection site, until day 8 after tumor challenge. Control mice received vehicle-only treatment (PBS). Palpable tumors were first detected between days 8–10 after tumor challenge, in both M. smegmatis-treated mice and control PBS-treated mice (Fig. 1a). By day 12, mice treated with M. smegmatis had noticeably smaller tumors than control PBS-treated mice, and a significant reduction in tumor growth was observed until completion of the experiment, at day 35 post-challenge. Tumors in mice treated with M. smegmatis took significantly longer to reach a size of 150 mm2, at which point the mice were required to be euthanized, than tumors in PBS-treated mice (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Peritumoral injection of M. smegmatis slows the growth of E.G7-OVA tumors. Mice received 5 × 105 E.G7-OVA tumor cells s.c. and 5 injections of 100 μL PBS or 2 × 106 CFU M. smegmatis peritumorally commencing on the day of tumor injection and every 2 days thereafter. a Tumor growth curves of individual animals. PBS control treatment is shown in open circles and M. smegmatis treatment in filled circles. The experiment was repeated five times with similar results. b Mice were euthanized when tumors exceeded 150 mm2. The percent of surviving mice that received PBS treatment (dashed line) or M. smegmatis treatment (solid line) is shown. *** p < 0.001 in a log-rank (Mantel–Cox) comparison of survival curves

To determine whether it was necessary to administer M. smegmatis adjacent to the tumor to elicit a protective effect, mice that received the E.G7-OVA tumor challenge were treated with M. smegmatis treatment either adjacent to the tumor or on the contralateral flank. Tumor growth was significantly delayed only when M. smegmatis treatment was administered adjacent to the tumor and no mice in this group had developed tumors ≥100 mm2 by day 22 post-challenge (data not shown). By contrast, 7 of 8 mice that had received M. smegmatis on the contralateral flank had developed tumors ≥100 mm2.

Treatment with heat-killed M. vaccae has been shown to induce protective anti-tumor responses [17, 18]. To determine whether the protection we observed required live bacilli, one group of mice was treated with heat-killed M. smegmatis adjacent to the tumor site. Interestingly, heat-killed M. smegmatis retained the ability to delay tumor growth with only 1 of 6 mice developing a tumor ≥100 mm2 (data not shown). Together, these findings demonstrate that peritumoral administration of M. smegmatis treatment delayed the growth of the E.G7-OVA thymoma in vivo.

CD8+ T cells mediate delayed tumor growth following M. smegmatis immunotherapy

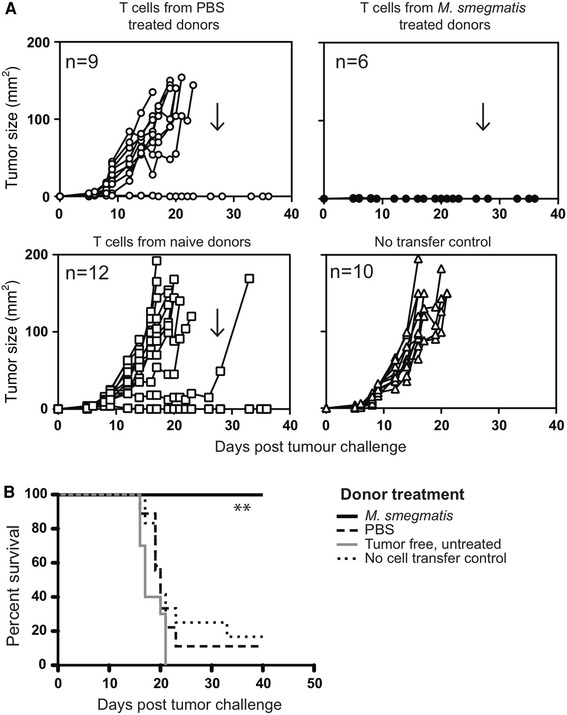

To establish whether the delayed tumor growth observed in M. smegmatis-treated mice was T cell mediated, we conducted adoptive transfer studies using enriched T cells from the spleens of treated, tumor-bearing mice. Donor mice received 5 peritumoral injections of M. smegmatis or PBS commencing at the time of tumor challenge. At day 17 post-tumor challenge, when mice from both experimental groups still survived although with tumors of different sizes, mice were culled and their spleens harvested. T cell-enriched splenocytes from M. smegmatis- or PBS-treated mice were injected intravenously (4 × 107 cells) into naïve recipient mice, which were subsequently challenged with EG7-OVA. Mice that received T cell-enriched splenocytes from PBS-treated mice or mice not challenged with tumors developed tumors at a similar time after challenge to naïve control mice that had not received any T cell transfers (Fig. 2a). The median time for the tumors to reach 150 mm2 was 18–20 days post-challenge for groups of mice that had received T cell-enriched splenocytes from PBS-treated mice or tumor-free mice (Fig. 2b). Strikingly, recipients of T cells from M. smegmatis-treated donors were fully protected from the E.G7-OVA challenge and no tumors were detectable in these mice at any point during the experiment (Fig. 2b). At day 28 after challenge, recipients of T cells from M. smegmatis-treated donors were re-challenged with EG7-OVA (Fig. 2a) and once again, no palpable tumors were detectable by the end of the experiment, at day 16 post-re-challenge. By contrast 8 of 9 naïve, no transfer control mice challenged at the same time had developed tumors by day 16 (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Adoptive transfer of T cell-enriched splenocytes from M. smegmatis-treated, tumor-bearing animals protects recipient mice from tumor challenge. Donor mice received tumor inoculation and commencement of PBS or M. smegmatis treatment as described in Fig. 1. Spleens were harvested 17 days after tumor challenge and were enriched for T cells. Recipient mice received 4 × 107 T cell-enriched splenocytes i.v. via the tail vein. The following day, recipients were injected s.c. with 5 × 105 E.G7-OVA tumor cells. Tumors’ sizes for individual mice are shown in a. Arrows indicate when mice were rechallenged with 5 × 105 E.G7-OVA tumor cells. Animals were culled when the tumor size exceeded 150 mm2 and survival curves are shown in b **indicates p < 0.005 in a log-rank (Mantel–Cox) comparison of survival curves comparing transfer of T cells from M. smegmatis or PBS treatment donors

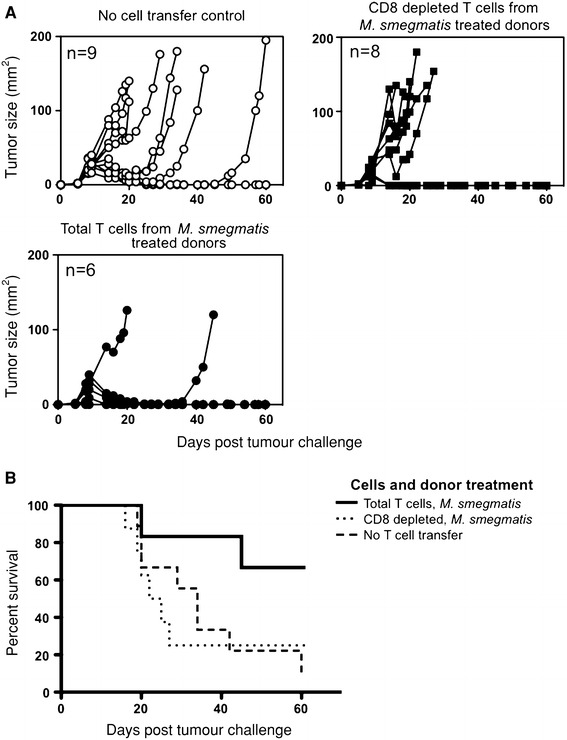

To establish which T cell subset was mediating tumor protection, T cell-enriched splenocytes from M. smegmatis-treated mice were depleted of CD4+ or CD8+ cells prior to adoptive transfer. In this experiment, 4 of 6 mice that received T cells from M. smegmatis-treated donors were fully protected from the tumor challenge (Fig. 3a). The median survival time of mice that received T cells from M. smegmatis-treated donors was >60 days, significantly different from mice that had not received a cell transfer (Table 1). By contrast, mice that received T cells from PBS-treated mice had a similar mean survival time to mice that had not received a cell transfer (Table 1). When enriched T cells from M. smegmatis-treated, tumor-bearing mice were depleted of CD8+ cells, tumor growth in the recipient mice was similar to growth in control mice that had not received a T cell transfer (Fig. 3b) and the mean survival time reduced to 23.5 days (Table 1). Depletion of CD4+ T cells slightly reduced the mean survival time, but this was not significant (Table 1). Together, these data demonstrate that CD8+ T cells from M. smegmatis-treated, tumor-bearing donor mice are required in order to transfer tumor protection to recipient mice.

Fig. 3.

CD8+ T cells are required for tumor protection of recipients. Pooled spleens from donors that had received an E.G7-OVA challenge 15 days previously and were M. smegmatis or PBS treated (as described in Fig. 1), were enriched for T cells (total T cells), or then depleted of CD8+ cells using magnetic bead separation (CD8-depleted T cells). Recipients received 2.5 × 107 cells and the following day were given 5 × 105 E.G7-OVA tumor cells subcutaneously. a Tumor growth curves are shown for individual recipients. b Survival curves are shown. p = 0.096 for a log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test comparing transfer of total T cells to CD8-depleted T cells from M. smegmatis-treated donors

Table 1.

Adoptive transfer of tumor protection

| PBS-treated donor | M. smegmatis-treated donor | No cell transfer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total T cells | 32 | >60* | 34 |

| CD4+-depleted T cells | 19.5 | 43 | |

| CD8+-depleted T cells | 24.5 | 23.5 | |

| Median survival (days) |

Pooled spleens from donors that had received an E.G7-OVA challenge 15 days previously and were M. smegmatis or PBS treated (as described in Fig. 1), were enriched for T cells, or then depleted of CD8 or CD4 cells using magnetic bead separation. Recipients received 2.5 × 107 cells and the following day were given 5 × 105 E.G7-OVA tumor cells subcutaneously. Mice were euthanized when tumors exceeded 150 mm2

*p < 0.05 compared to the no cell transfer control

Mycobacterium smegmatis treatment induces a population of inflammatory monocyte-derived dendritic cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes.

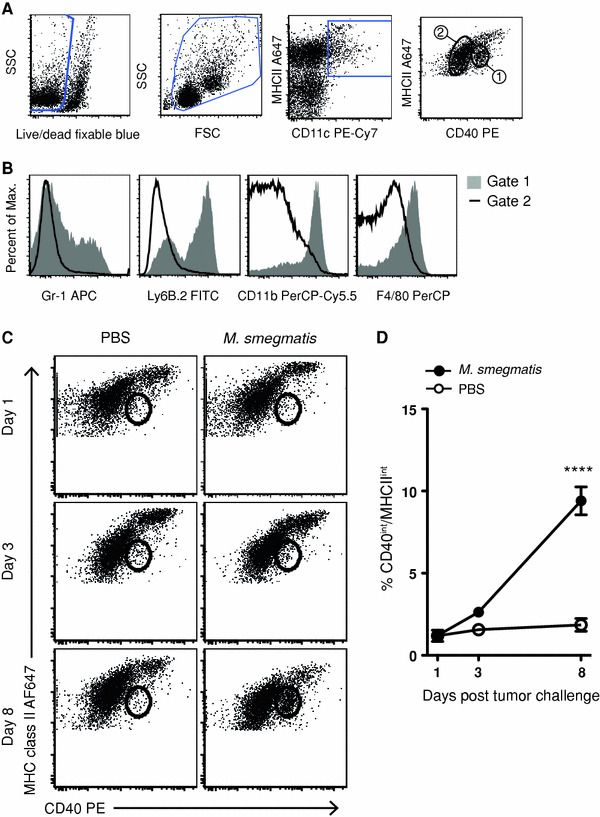

Following intravesical BCG treatment, patients who do not develop recurrent bladder cancer tend to increase the percentage of DCs in their urine [13]. To determine whether M. smegmatis treatment altered the number or phenotype of DCs present in the tumor-draining lymph nodes, at days 1, 3, and 8 post-tumor challenge, and commencement of treatment, the axillary and brachial lymph nodes were harvested and examined by flow cytometry (Fig. 4a). One day after tumor challenge and the first M. smegmatis injection, no significant changes were observed in the DC populations within the tumor-draining lymph node compared to PBS treatment. However, after 4 injections of M. smegmatis, on day 8, there was a significant increase in CD11c+ cells that expressed high levels of CD11b (Fig. 4a–c). This population was MHC class IIint, CD40int, had a broad expression of Gr-1 and was bimodal for Ly6B.2, a marker associated with inflammation and monocytes [21] (Fig. 4a). This expression pattern is suggestive of an inflammatory monocyte-derived dendritic cell population [22, 23].

Fig. 4.

M. smegmatis treatment induces a population of CD11c+ cells with a monocyte-derived DC phenotype in the tumor-draining lymph nodes. Mice received E.G7-OVA tumors and M. smegmatis treatment as described in Fig. 1. Tumor-draining axillary, inguinal, and brachial lymph nodes harvested at time points indicated after tumor challenge and were analyzed for DC phenotype and activation state. a Lymph node dendritic cells (DC) were gated to include single, live, CD11c, MHC class II positive events. DC populations were gated based on CD40 and MHC class II expression (1 and 2) and then were compared in b, with histograms showing expression of Gr-1, Ly6B.2, CD11b, and F4/80. c Tumor-draining lymph nodes were analyzed by flow cytometry and gated as in a. The number indicates the percentage of events in the CD40int and MHC class IIint gate. This population increases after M. smegmatis treatment as shown in d, where open circles represent PBS treatment and filled circles, M. smegmatis treatment. This experiment was repeated twice, with similar results (n = 3–5 mice/group)

Discussion

To determine whether M. smegmatis treatment could induce a systemic anti-tumor immune response, we adoptively transferred T cells from treated, tumor-bearing mice into naïve recipient animals that were subsequently tumor challenged. We found that administration of M. smegmatis treatment adjacent to the tumor slowed the tumor growth. Once an anti-tumor response was generated, it appeared to be systemic since spleen-derived T cells from M. smegmatis-treated mice were able to transfer tumor protection. Our data suggest that CD8+ T cells are essential for this protective effect. Interestingly, analysis of the tumor-draining lymph nodes revealed an increase in monocyte-derived DCs with an inflammatory phenotype, which may play an important role in orchestrating the anti-tumor response.

Although BCG is routinely used in the clinic to treat bladder cancer, its use is complicated by its toxicity, which in one large study led to nearly a third of patients discontinuing treatment [24]. In our study, we have used a related organism, M. smegmatis, which is arguably less pathogenic than BCG. BCG has been shown to cause systemic, and on occasion fatal, disease. By contrast, M. smegmatis is a commensal organism commonly found in the genital tract that has been associated with systemic disease only rarely, with a single fatality described in the literature in an individual with a congenital immunodeficiency [25]. Aside from its low pathogenicity, M. smegmatis offers potential for use as an immunotherapeutic agent owing to its ability induce significantly higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in macrophages than BCG [26].

In our tumor model, heat-killed M. smegmatis retained its protective efficacy, in keeping with an earlier study showing that heat-killed M. vaccae preparations elicited protective anti-tumor responses in vivo [18]. Together, these findings suggest that heat-killed preparations of fast-growing, non-pathogenic strains of mycobacteria may have potential as alternatives to BCG, particularly in cases where treatment toxicity affects compliance.

Cheadle et al. [27] used recombinant BCG or recombinant M. smegmatis expressing a hen egg ovalbumin epitope to treat mice given a B16 melanoma that also expressed ovalbumin. It was found that the recombinant BCG afforded protection against the tumor while recombinant M. smegmatis did not. The recombinant BCG secreted ~750-fold more ova than the recombinant M. smegmatis, and the authors acknowledge that this may have significantly impacted on the efficacy of the therapeutic vaccines. However, it is important to note that it was found that antigen from the recombinant M. smegmatis strains was not as efficiently processed and presented on MHC class I by in vivo–generated, bone-marrow-derived DCs, as BCG [27]. Interestingly, in the same study, it was shown in vitro that M. smegmatis was a more potent inducer of DC maturation than BCG.

Following infection, or vaccination with adjuvants that include mycobacterial cell wall components, it has been shown that inflammatory DCs, derived from inflammatory Gr-1+ monocytes, are able to migrate to the lymph nodes via the lymphatics or directly from the blood [28, 29]. These CD11c+CD40intCD11bhiGr-1+ inflammatory monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs) have been shown to be a major source of IL-12(p70) and are potent stimulators of interferon (IFN)-γ production by T cells [28, 29]. Moreover, MoDCs have been shown to be capable of presenting exogenous antigen to CD8 T cells [30, 31], an activity usually restricted to specialized DC subsets.

Monocyte extravasation from the blood into lymph nodes can be driven by a number of chemokines, including monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (CCL2) [32]. Interestingly, a study of intravenous infection of M. smegmatis in mice found significantly increased expression of CCL2 7 days after infection [26], the timing of which coincides with our identification of MoDCs in the lymph nodes 8 days after subcutaneous M. smegmatis treatment. The chemokines involved in extravasation appear to be dependent on the type and timing of the inflammatory stimulus, as well as the peripheral tissue being drained [29]. To determine whether CCL2 is essential for the accumulation of inflammatory DCs after M. smegmatis treatment, mice deficient in this chemokine could be used.

MoDCs are the predominant DC subset infected with M. tuberculosis or BCG, and can be detected in the lung as early as 48 h after intranasal infection [33]. It has recently been reported that MoDCs migrate through both acute and chronic granulomas induced by BCG and importantly that the DCs that leave granulomas are able to migrate to systemic sites where they induce T cell priming [34]. If this is also the case with M. smegmatis treatment, the ability of MoDCs to migrate away from the treatment site may promote the induction of systemic anti-tumor responses.

DC defects have been associated with the suppressive intratumoral environment and inefficient generation of anti-tumor T cell responses [35]. In particular, Gerner et al. showed that DC from subcutaneous EG7-OVA tumors and B16.OVA tumors were unable to present OVA antigen to specific CD4+ T cells in vivo and in vitro, resulting in defective initiation of CD8+ T cells responses due to the lack of CD4+ T cell help [36, 37]. Treatment with individual TLR ligands [35, 37] or depletion of regulatory T cells [38] was not sufficient to rescue the function of those DC. The precise mechanism by which the M. smegmatis-induced CD8+ T cells in our study mediated tumor protection remains to be determined; however, it is likely that their ability to produce interferon-γ and ability to infiltrate the tumor are key [39–41]. Although not investigated in the EG7.OVA model, in another murine tumor model (B16F1 melanoma) we have administered M. smegmatis together with monosodium urate crystals, and show that decreased tumor growth is associated with increased CD8+ T cells in the tumor, and more interferon-γpos CD8+ T cells by intracellular cytokine staining without restimulation (manuscript in preparation).

In this paper, we show that local treatment with M. smegmatis resulted in the activation of systemic CD8+ T cell immunity and was associated with the appearance of a population of inflammatory DC in the tumor-draining lymph node. These data suggest that, rather than rescuing the function of the DC already in the tumor and/or tumor-draining lymph node, mycobacterial treatment may act by inducing the involvement of a new population of inflammatory cells with intact function. As mycobacterial treatment was effective if given locally in the tumor, but not when given at distant sites, we presume that accumulation of inflammatory DC occurred at the tumor site first, and then in the lymph node where these DC may present antigen to T cells, either directly or by interacting with resident DC populations. Cytokine production by inflammatory DC may also play a critical role by restricting the function of local regulatory T cells [42, 43].

It is important to note that the MoDCs detected in the draining lymph nodes after M. smegmatis treatment expressed lower levels of CD40 and MHC class II than the CD11c+CD11b− DCs. MoDCs are known to be CD40int, but this does not appear to affect their ability to effectively stimulate T cell responses [29]. In contrast to our findings, MoDCs detected in the liver 3 weeks after a system BCG infection increased MHC class II expression, although expression had decreased by 10 weeks after infection [34]. Whether the decreased MHC class II expression detected following M. smegmatis treatment would impair the development of an effective CD8-mediated anti-tumor response through decreased CD4 T cell help is unknown. Nonetheless, the inflammatory DC population we identified in tumor-draining lymph nodes appears to be a likely candidate for driving the activation and differentiation of the tumor-protective, CD8 T cell responses we identified.

In summary, we have shown that M. smegmatis treatment of a subcutaneous mouse thymoma slowed tumor growth and elicited a systemic CD8 T cell-mediated, anti-tumor immune response. Treatment with M. smegmatis was associated with the appearance of MoDCs in the draining lymph node. It will be of great interest to determine whether the MoDC population is key for driving the anti-tumor response.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the Cancer Society of New Zealand and from the Malaghan Institute of Medical Research. Joanna Kirman is the Wellington Medical Research Foundation Malaghan Haematology Fellow; Sabine Kuhn was supported by a PhD scholarship from DAAD and Victoria University of Wellington. The authors thank the Biomedical Research Unit at the Malaghan Institute for their excellent animal husbandry, and Kelly Prendergast and Lindsay Ancelet for assistance with experiments.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Franca Ronchese, Email: fronchese@malaghan.org.nz.

Joanna R. Kirman, Phone: +64-4-9033046, FAX: +64-4-4996915, Email: jo.kirman@otago.ac.nz

References

- 1.Coley WB (1910) The treatment of inoperable sarcoma by bacterial toxins (the mixed toxins of the Streptococcus erysipelas and the Bacillus prodigiosus). Proc R Soc Med 3 (Surg Sect):1–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Grange JM, Bottasso O, Stanford CA, Stanford JL. The use of mycobacterial adjuvant-based agents for immunotherapy of cancer. Vaccine. 2008;26(39):4984–4990. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleinnijenhuis J, Oosting M, Joosten LA, Netea MG, Van Crevel R. Innate immune recognition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . Clin Dev Immunol. 2011;2011:405310. doi: 10.1155/2011/405310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jo EK. Mycobacterial interaction with innate receptors: TLRs, C-type lectins, and NLRs. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21(3):279–286. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f88b5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsuji S, Matsumoto M, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Azuma I, Hayashi A, Toyoshima K, Seya T. Maturation of human dendritic cells by cell wall skeleton of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin: involvement of toll-like receptors. Infect Immun. 2000;68(12):6883–6890. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.12.6883-6890.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gnjatic S, Sawhney NB, Bhardwaj N. Toll-like receptor agonists: are they good adjuvants? Cancer J. 2010;16(4):382–391. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181eaca65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morales A, Eidinger D, Bruce AW. Intracavitary bacillus Calmette-Guerin in the treatment of superficial bladder tumors. J Urol. 1976;116(2):180–183. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)58737-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, Kaasinen E, Bohle A, Palou-Redorta J, Roupret M. EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, the 2011 update. Eur Urol. 2011;59(6):997–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shelley MD, Mason MD, Kynaston H. Intravesical therapy for superficial bladder cancer: a systematic review of randomised trials and meta-analyses. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(3):195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bevers RF, Kurth KH, Schamhart DH. Role of urothelial cells in BCG immunotherapy for superficial bladder cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(4):607–612. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayari C, LaRue H, Hovington H, Decobert M, Harel F, Bergeron A, Tetu B, Lacombe L, Fradet Y. Bladder tumor infiltrating mature dendritic cells and macrophages as predictors of response to bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy. Eur Urol. 2009;55(6):1386–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higuchi T, Shimizu M, Owaki A, Takahashi M, Shinya E, Nishimura T, Takahashi H. A possible mechanism of intravesical BCG therapy for human bladder carcinoma: involvement of innate effector cells for the inhibition of tumor growth. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58(8):1245–1255. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0643-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beatty JD, Islam S, North ME, Knight SC, Ogden CW. Urine dendritic cells: a noninvasive probe for immune activity in bladder cancer? BJU Int. 2004;94(9):1377–1383. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young SL, Murphy M, Zhu XW, Harnden P, O’Donnell MA, James K, Patel PM, Selby PJ, Jackson AM. Cytokine-modified Mycobacterium smegmatis as a novel anticancer immunotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2004;112(4):653–660. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rakshit S, Ponnusamy M, Papanna S, Saha B, Ahmed A, Nandi D. Immunotherapeutic efficacy of Mycobacterium indicus pranii in eliciting anti-tumor T cell responses: critical roles of IFNgamma. Int J Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/ijc.26099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stebbing J, Dalgleish A, Gifford-Moore A, Martin A, Gleeson C, Wilson G, Brunet LR, Grange J, Mudan S. An intra-patient placebo-controlled phase I trial to evaluate the safety and tolerability of intradermal IMM-101 in melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanford JL, Stanford CA, O’Brien ME, Grange JM. Successful immunotherapy with Mycobacterium vaccae in the treatment of adenocarcinoma of the lung. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(2):224–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel PM, Sim S, O’Donnell DO, Protheroe A, Beirne D, Stanley A, Tourani JM, Khayat D, Hancock B, Vasey P, Dalgleish A, Johnston C, Banks RE, Selby PJ. An evaluation of a preparation of Mycobacterium vaccae (SRL172) as an immunotherapeutic agent in renal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(2):216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yarkoni E, Rapp HJ. Immunotherapy of experimental cancer by intralesional injection of emulsified nonliving mycobacteria: comparison of Mycobacterium bovis (BCG), Mycobacterium phlei, and Mycobacterium smegmatis . Infect Immun. 1980;28(3):887–892. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.3.887-892.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore MW, Carbone FR, Bevan MJ. Introduction of soluble protein into the class I pathway of antigen processing and presentation. Cell. 1988;54(6):777–785. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(88)91043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosas M, Thomas B, Stacey M, Gordon S, Taylor PR. The myeloid 7/4-antigen defines recently generated inflammatory macrophages and is synonymous with Ly-6B. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88(1):169–180. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0809548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leon B, Lopez-Bravo M, Ardavin C. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Semin Immunol. 2005;17(4):313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geissmann F, Manz MG, Jung S, Sieweke MH, Merad M, Ley K. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science. 2010;327(5966):656–661. doi: 10.1126/science.1178331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden AP, Oosterlinck W, Hoeltl W, Bono AV. The side effects of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin in the treatment of Ta T1 bladder cancer do not predict its efficacy: results from a European organisation for research and treatment of Cancer Genito-Urinary Group Phase III Trial. Eur Urol. 2003;44(4):423–428. doi: 10.1016/S0302-2838(03)00371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierre-Audigier C, Jouanguy E, Lamhamedi S, Altare F, Rauzier J, Vincent V, Canioni D, Emile JF, Fischer A, Blanche S, Gaillard JL, Casanova JL. Fatal disseminated Mycobacterium smegmatis infection in a child with inherited interferon gamma receptor deficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(5):982–984. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.5.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roach DR, Bean AG, Demangel C, France MP, Briscoe H, Britton WJ. TNF regulates chemokine induction essential for cell recruitment, granuloma formation, and clearance of mycobacterial infection. J Immunol. 2002;168(9):4620–4627. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheadle EJ, O’Donnell D, Selby PJ, Jackson AM. Closely related mycobacterial strains demonstrate contrasting levels of efficacy as antitumor vaccines and are processed for major histocompatibility complex class I presentation by multiple routes in dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73(2):784–794. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.784-794.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leon B, Lopez-Bravo M, Ardavin C. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells formed at the infection site control the induction of protective T helper 1 responses against Leishmania. Immunity. 2007;26(4):519–531. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakano H, Lin KL, Yanagita M, Charbonneau C, Cook DN, Kakiuchi T, Gunn MD. Blood-derived inflammatory dendritic cells in lymph nodes stimulate acute T helper type 1 immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(4):394–402. doi: 10.1038/ni.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Borgne M, Etchart N, Goubier A, Lira SA, Sirard JC, van Rooijen N, Caux C, Ait-Yahia S, Vicari A, Kaiserlian D, Dubois B. Dendritic cells rapidly recruited into epithelial tissues via CCR6/CCL20 are responsible for CD8+ T cell crosspriming in vivo. Immunity. 2006;24(2):191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segura E, Albiston AL, Wicks IP, Chai SY, Villadangos JA. Different cross-presentation pathways in steady-state and inflammatory dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(48):20377–20381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910295106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palframan RT, Jung S, Cheng G, Weninger W, Luo Y, Dorf M, Littman DR, Rollins BJ, Zweerink H, Rot A, von Andrian UH. Inflammatory chemokine transport and presentation in HEV: a remote control mechanism for monocyte recruitment to lymph nodes in inflamed tissues. J Exp Med. 2001;194(9):1361–1373. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.9.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reljic R, Di Sano C, Crawford C, Dieli F, Challacombe S, Ivanyi J. Time course of mycobacterial infection of dendritic cells in the lungs of intranasally infected mice. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2005;85(1–2):81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schreiber HA, Harding JS, Hunt O, Altamirano CJ, Hulseberg PD, Stewart D, Fabry Z, Sandor M. Inflammatory dendritic cells migrate in and out of transplanted chronic mycobacterial granulomas in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(10):3902–3913. doi: 10.1172/JCI45113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stoitzner P, Green LK, Jung JY, Price KM, Atarea H, Kivell B, Ronchese F. Inefficient presentation of tumor-derived antigen by tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57(11):1665–1673. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0487-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerner MY, Casey KA, Mescher MF. Defective MHC class II presentation by dendritic cells limits CD4 T cell help for antitumor CD8 T cell responses. J Immunol. 2008;181(1):155–164. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerner MY, Mescher MF. Antigen processing and MHC-II presentation by dermal and tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2009;182(5):2726–2737. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ataera H, Hyde E, Price KM, Stoitzner P, Ronchese F. Murine melanoma-infiltrating dendritic cells are defective in antigen presenting function regardless of the presence of CD4CD25 regulatory T cells. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mellman I, Coukos G, Dranoff G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature. 2011;480(7378):480–489. doi: 10.1038/nature10673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Helmich BK, Dutton RW. The role of adoptively transferred CD8 T cells and host cells in the control of the growth of the EG7 thymoma: factors that determine the relative effectiveness and homing properties of Tc1 and Tc2 effectors. J Immunol. 2001;166(11):6500–6508. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hollenbaugh JA, Dutton RW. IFN-gamma regulates donor CD8 T cell expansion, migration, and leads to apoptosis of cells of a solid tumor. J Immunol. 2006;177(5):3004–3011. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Toll pathway-dependent blockade of CD4+ CD25+ T cell-mediated suppression by dendritic cells. Science. 2003;299(5609):1033–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.1078231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zanin-Zhorov A, Ding Y, Kumari S, Attur M, Hippen KL, Brown M, Blazar BR, Abramson SB, Lafaille JJ, Dustin ML. Protein kinase C-theta mediates negative feedback on regulatory T cell function. Science. 2010;328(5976):372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1186068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]