Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

The effects of genetic factors on pregnancy outcomes in chronic pancreatitis (CP) patients remain unclear. We evaluated the impacts of clinical features and mutations in main CP-susceptibility genes (SPINK1, PRSS1, CTRC, and CFTR) on pregnancy outcomes in Chinese CP patients.

METHODS:

This was a prospective cohort study with 14-year follow-up. The sample comprised female CP patients with documented pregnancy and known genetic backgrounds. Adverse pregnancy outcomes were compared between patients with and without gene mutations. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to determine the impact factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes.

RESULTS:

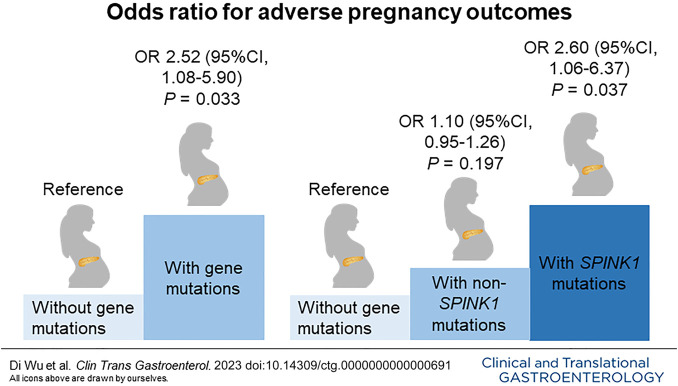

Totally, 160 female CP patients with a pregnancy history were enrolled; 59.4% of patients carried pathogenic mutations in CP-susceptibility genes. Adverse pregnancy outcomes occurred in 38 patients (23.8%); the prevalence of adverse outcomes was significantly higher in those harboring gene mutations than those without (30.5% vs 13.8%, P = 0.015). Notably, the rates of preterm delivery (12.6% vs 3.1%, P = 0.036) and abortion (17.9% vs 4.6%, P = 0.013) were remarkably higher in patients with gene mutations (especially SPINK1 mutations) than those without. In multivariate analyses, both CP-susceptibility gene mutations (odds ratio, 2.52; P = 0.033) and SPINK1 mutations (odds ratio, 2.60; P = 0.037) significantly increased the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Acute pain attack during pregnancy was another risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes.

DISCUSSION:

Pathogenic mutations in CP-susceptibility genes, especially SPINK1, were independently related to adverse pregnancy outcomes in CP patients. Significant attention should be paid to pregnant females harboring CP-susceptibility gene mutations (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT06055595).

KEYWORDS: Chronic pancreatitis, CP-susceptibility gene mutations, SPINK1 mutations, adverse pregnancy outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a progressive disease characterized by fibrosis and inflammation of the pancreas, which is caused by genetic and environmental factors (1). Morphological changes, including atrophy, fibrosis, duct distortion, and strictures, and calcification lead to irreversible damage to pancreatic endocrine and exocrine functions. Abdominal pain is the most dominant clinical feature of CP. Both the recurrent pain and the development of pancreatic insufficiency contribute to poor quality of life and increase mental and economic burdens for patients (2).

Female patients account for around 30% of all CP patients (3). The course of CP may cover the duration of childbearing age; therefore, there are concerns about the fertility and outcomes of pregnancies in female CP patients. There is a paucity of studies focused on the effect of CP on pregnancy outcomes, with inconsistent conclusions. One study by Mahapatra et al (4) enrolled 99 CP patients and found no increased risk of CP on adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Another retrospective study of 46 patients by Rana et al (5) also found that CP was not associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Both of the above studies had relatively small sample sizes and were designed as retrospective studies. The most recent population-based study conducted by Niu et al (6) analyzed the clinical data of 3,094 CP patients obtained from the US National Inpatient Sample database and concluded that CP was associated with elevated rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) (adjusted odds ratios [AOR], 1.63), gestational hypertensive complications (AOR, 2.48), preterm labor (AOR, 3.10), and small for gestational age (AOR, 2.40). To date, no study has focused on the risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes among CP patients.

Different from the etiology of male patients, which is predominated by alcoholic CP, the most common etiology of female patients is idiopathic CP (ICP) (7), which is characterized by high rates of CP-susceptibility gene mutations. Genetic factors are known to play important roles in the development, clinical manifestations, and progression of CP. SPINK1 (encoding pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor), PRSS1 (encoding cationic trypsinogen), CTRC (encoding chymotrypsin C), and CFTR (encoding cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) are the 4 major germline susceptibility genes for CP (8). Our previous study (7) of 1,061 Chinese CP patients found that 50.42% of patients harbored at least one rare pathogenic variant in the above 4 genes; these variants were associated with earlier median ages at disease onset and diagnosis of pancreatic stones, diabetes mellitus, and steatorrhea. Muller et al (9) also found that SPINK1-related pancreatitis was associated with earlier onset and pancreatic insufficiencies, based on a European cohort of 209 CP patients with gene mutations. It is also known that germline genetic alterations significantly contribute to reproductive failure. Thus, whether variants in CP-susceptibility genes impact pregnancy outcomes in female CP patients is worthy of further exploration.

Given the current uncertainty regarding the pregnancy outcomes of CP patients with or without gene mutations, this study explored the effects of genetic factors on pregnancy outcomes using a well-phenotyped cohort of Chinese female CP patients. The aim was to provide valuable information to assist maternal healthcare providers in counseling female CP patients and identifying those at high risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes to inform clinical decision-making.

METHODS

Study setting and patients

This prospective observational study was performed at Changhai Hospital. Female CP patients from January 2010 to December 2014 were enrolled in the study after informed consent was obtained. Study participants provided a blood sample for genetic testing. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Changhai Hospital (CHEC2020-008), and all procedures were performed according to the ethical standards in the Declaration of Helsinki. All diagnostic and therapeutic procedures were performed according to the approved guidelines.

Patients were under regular annual follow-up as described in our previous study (3). The patients' clinical features and pregnancy-related data were updated by telephone. Data for this study were obtained in May 2023. The exclusion criteria were (i) patients without documented pregnancy, (ii) patients who refused to provide pregnancy-related information or those with incomplete pregnancy data, and (iii) patients with other autoimmune comorbidities that might influence pregnancy outcomes, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and autoimmune thyroid diseases.

Genetic testing

This study examined 4 major CP-susceptibility genes, i.e., the SPINK1, PRSS1, CTRC, and CFTR genes. A detailed description of the procedures for DNA preparation and gene sequencing has been provided previously (7). Known rare pathogenic gene mutations (those with a minor allele frequency of <1% in the general population) were included in the final analysis.

Outcomes

The outcome was a composite variable of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including adverse maternal outcomes (CP-associated cesarean delivery, CP-associated preterm delivery, GDM, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy [HDP]) and adverse fetal outcomes (low birth weight, CP-associated abortion, congenital anomaly, and stillbirth).

Definitions

The diagnosis of CP was established according to the Asia-Pacific consensus (10). Alcoholic CP was defined as alcohol intake of ≥60 g/d for at least 2 years. Hereditary CP was defined as more than 2 first-degree relatives or more than 3 second-degree relatives with CP or recurrent acute pancreatitis. Other etiologies of CP included abnormal anatomy of the pancreatic duct, trauma, and so forth. ICP was diagnosed when none of the known causes were identified (3). Diabetes was diagnosed according to the diagnostic criteria of the American Diabetes Association (11). Steatorrhea was diagnosed in accordance with our previous study (7). Pseudocysts, portal hypertension, and biliary stricture were diagnosed on imaging examination (12).

The pregnancy outcomes in this study were defined as follows. CP-associated cesarean delivery was defined as cesarean delivery because of acute attacks of CP or comorbidities associated with CP, such as GDM or HDP (6). Acute attacks of CP could be diagnosed if at least 2 of the following 3 criteria were fulfilled: (i) The current attack displayed typical abdominal pain, (ii) serum lipase or amylase level was at least 3 times the upper limit of normal, and (iii) ultrasonography showed morphological changes in the pancreas. CP-associated preterm delivery was defined as preterm delivery (i.e., delivery at less than 37 weeks' gestation (13)) because of acute attacks of CP or comorbidities associated with CP. GDM was defined as the onset or first recognition of abnormal glucose tolerance during pregnancy (14). The diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy was based on characteristic symptoms and elevated serum bile acids in the absence of other hepatobiliary diseases (15). HDP included preeclampsia/eclampsia, chronic hypertension with/without superimposed preeclampsia, and gestational hypertension (16). Low birth weight was defined as a weight <2,500 g at birth (17). CP-associated abortion was defined as abortion (i.e., pregnancy loss before 28 weeks' gestation (18)) because of acute attacks of CP or comorbidities associated with CP. Congenital anomaly was defined as inborn errors of development (19). Stillbirth was defined as a fetus ≥20 weeks' gestation with no signs of life (20).

Statistical analysis

For continuous variables, tests of data normality were performed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were presented as mean ± SD and were compared using Student t tests; non-normally distributed variables were presented as median (interquartile range [IQR]) and were compared using Mann-Whitney U tests. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. χ2 analysis or Fisher exact test was used for the comparison of categorical variables. Two-sided P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. For multiple comparisons, Bonferroni adjustment was applied. Variables with a P value <0.05 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression model. For multivariate analysis, the likelihood ratio statistic was calculated with an “enter” logistic regression model. AORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 23 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

General characteristics of the enrolled patients

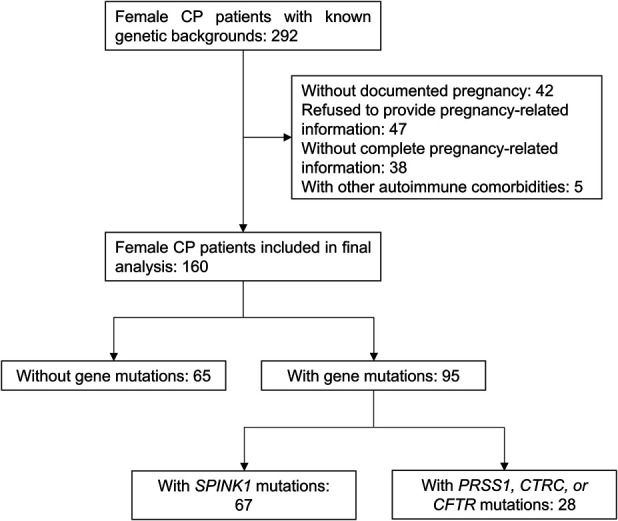

The enrollment flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. A total of 292 females from our previously reported prospective Chinese CP cohort (3) were enrolled. After the application of the exclusion criteria, 42 patients without documented pregnancy, 47 patients who refused to provide pregnancy-related information, 38 patients without complete pregnancy-related information, and 5 patients with other autoimmune comorbidities that might influence pregnancy outcomes were excluded from this study. Finally, data from 160 patients who had known genetic backgrounds and a pregnancy history were analyzed.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study participants. CP, chronic pancreatitis.

The characteristics of the cohort are presented in Table 1. At least one rare pathogenic mutation in the 4 genes mentioned above was identified in 95 patients (59.4%). Among these, SPINK1 mutations were the most common, observed in 67 patients (41.9%). Compared with patients without gene mutations, more patients with gene mutations were classified as ICP (P < 0.001), and the prevalence of pseudocysts was lower (7.4% vs 18.5%, P = 0.033).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the enrolled patients

| Total (n = 160) | Patients with gene mutations (n = 95) | Patients without gene mutations (n = 65) | P | |

| Age at diagnosis of CP, yr (IQR) | 38.5 (27.0–48.0) | 33.0 (24.0–41.0) | 46.0 (35.5–54.0) | <0.001 |

| Age at onset of CP, yr (IQR) | 32.5 (22.0–44.0) | 29.0 (19.0–39.0) | 42.0 (29.5–50.5) | <0.001 |

| Age at the end of follow-up, yr (IQR) | 49.5 (38.9–58.0) | 44.0 (37.0–53.0) | 56.0 (46.5–64.0) | <0.001 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 4 (2.5) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (4.6) | 0.367 |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | 4 (2.5) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (4.6) | 0.367 |

| Age at marriage, yr (IQR) | 24.0 (22.0–26.0) | 24.0 (22.5–26.0) | 23.0 (21.0–26.0) | 0.055 |

| Age at first pregnancy, yr (IQR) | 25.0 (22.0–28.0) | 25.0 (23.0–28.0) | 24.0 (22.0–27.8) | 0.278 |

| Age at first delivery, yr (IQR) | 25.0 (23.0–28.0) | 25.0 (23.0–28.0) | 24.0 (22.0–27.8) | 0.237 |

| Onset symptoms, n (%) | 0.565 | |||

| Pain | 50 (31.3) | 33 (34.7) | 17 (26.2) | |

| AP | 78 (48.8) | 41 (43.2) | 37 (56.9) | |

| Diabetes | 14 (8.8) | 9 (9.5) | 5 (7.7) | |

| Steatorrhea | 10 (6.3) | 7 (7.4) | 3 (4.6) | |

| Asymptomatic | 8 (5.0) | 5 (5.3) | 3 (4.6) | |

| Etiology of CP, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Idiopathic | 131 (81.9) | 84 (88.4) | 47 (72.3) | |

| Alcoholic | 4 (2.5) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (4.6) | |

| Hereditary | 6 (3.8) | 6 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Othersa | 19 (11.9) | 4 (4.2) | 15 (23.1) | |

| Complications of CP, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 48 (30.0) | 28 (29.5) | 20 (30.8) | 0.861 |

| Steatorrhea | 36 (22.5) | 24 (25.3) | 12 (18.5) | 0.312 |

| Pseudocyst | 19 (11.9) | 7 (7.4) | 12 (18.5) | 0.033 |

| Portal hypertension | 6 (3.8) | 3 (3.2) | 3 (4.6) | 0.958 |

| Biliary stricture | 4 (2.5) | 3 (3.2) | 1 (1.5) | 0.897 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — |

| Gene mutations, n (%) | 95 (59.4) | — | — | — |

| SPINK1 mutations | 67 (41.9) | 67 (70.5) | — | — |

| PRSS1 mutations | 24 (15.0) | 24 (25.3) | — | — |

| CTRC mutations | 6 (3.8) | 6 (6.3) | — | — |

| CFTR mutations | 16 (10.0) | 16 (16.8) | — | — |

| Acute pain attack during pregnancy, n (%) | 13 (8.1) | 10 (10.5) | 3 (4.6) | 0.179 |

| ERCP and/or ESWL, n (%) | 156 (97.5) | 95 (100.0) | 61 (93.8) | 0.053 |

| Surgery, n (%) | 10 (6.3) | 5 (5.3) | 5 (7.7) | 0.771 |

AP, acute pancreatitis; CP, chronic pancreatitis; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; ESWL, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy; IQR, interquartile range.

Other etiology of CP includes abnormal anatomy of pancreatic duct and trauma.

Pregnancy outcomes and comparison between patients with and without gene mutations

The pregnancy outcomes of the patients are shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Digital Content (see Supplementary Figure 1, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B93). There was a total of 364 pregnancies and 227 deliveries among the enrolled patients. CP-associated adverse pregnancy outcomes occurred in 38 patients (23.8%).

Table 2.

Pregnancy outcomes of female CP patients with and without gene mutations

| Total (n = 160) | Patients with gene mutations (n = 95) | Patients without gene mutations (n = 65) | P | |

| No. of pregnancies per woman, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.604 |

| No. of deliveries per woman, median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.069 |

| Delivery, n (%) | 157 (98.1) | 93 (97.9) | 64 (98.5) | 1.000 |

| CP-associated adverse pregnancy outcomes, n (%) | 38 (23.8) | 29 (30.5) | 9 (13.8) | 0.015 |

| CP-associated adverse maternal outcomes, n (%) | 25 (15.6) | 19 (20.0) | 6 (9.2) | 0.065 |

| CP-associated cesarean delivery | 19 (11.9) | 15 (15.8) | 4 (6.2) | 0.064 |

| CP-associated preterm delivery | 14 (8.8) | 12 (12.6) | 2 (3.1) | 0.036 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 4 (2.5) | 3 (3.2) | 1 (1.5) | 0.897 |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | 5 (3.1) | 4 (4.2) | 1 (1.5) | 0.623 |

| Gestational hypertension | 4 (2.5) | 3 (3.2) | 1 (1.5) | 0.897 |

| Eclampsia | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| CP-associated adverse fetal outcomes, n (%) | 27 (16.9) | 21 (22.1) | 6 (9.2) | 0.033 |

| Low birth weight | 10 (6.3) | 7 (7.4) | 3 (4.6) | 0.708 |

| CP-associated abortion | 20 (12.5) | 17 (17.9) | 3 (4.6) | 0.013 |

| Congenital anomaly | 2 (1.3) | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.515 |

| Stillbirth | 2 (1.3) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.5) | 1.000 |

CP, chronic pancreatitis; IQR, interquartile range.

Patients with gene mutations had a significantly higher incidence of CP-associated adverse pregnancy outcomes than those without (30.5% vs 13.8%, P = 0.015). In terms of maternal outcomes, the overall incidence of adverse outcomes was higher in patients with gene mutations, and this difference was borderline significant (20.0% vs 9.2%, P = 0.065). Notably, the proportion of CP-associated preterm deliveries was remarkably higher in patients with gene mutations (12.6% vs 3.1%, P = 0.036). For fetal outcomes, the overall incidence of adverse outcomes was significantly higher in patients with gene mutations (22.1% vs 9.2%, P = 0.033). Moreover, there was a significant difference between the 2 groups in the proportion of CP-associated abortion (17.9% vs 4.6%, P = 0.013) (Table 2).

Gene mutation distribution in patients with and without adverse pregnancy outcomes

The distribution of gene mutations in patients with and without adverse pregnancy outcomes is shown in Table 3. The prevalence of SPINK1 mutations (57.9% vs 36.9%, P = 0.022), as well as the most common variant c.194 + 2T>C (57.9% vs 33.6%, P = 0.007), was significantly higher in those with adverse pregnancy outcomes compared with those without. The distributions of gene mutations in patients with CP-associated preterm delivery and abortion, the 2 most serious adverse events, are shown in Supplementary Digital Content (see Supplementary Table 1, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B93).

Table 3.

Distribution of CP-susceptibility gene mutations in patients with and without adverse pregnancy outcomes

| Patients with adverse pregnancy outcomes (n = 38) | Patients without adverse pregnancy outcomes (n = 122) | P | |

| Gene mutations, n (%) | 29 (76.3) | 66 (54.1) | 0.015 |

| SPINK1 mutations | 22 (57.9) | 45 (36.9) | 0.022 |

| c.194 + 2T>C | 22 (57.9) | 41 (33.6) | 0.007 |

| c.101A>G | 1 (2.6) | 3 (2.5) | 1.000 |

| c.202C>T | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1.000 |

| c.206C>T | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.238 |

| c.75C>G | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.238 |

| PRSS1 mutations | 7 (18.4) | 17 (13.9) | 0.499 |

| c.86A>T | 2 (5.3) | 2 (1.6) | 0.239 |

| c.346C>T | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | 1.000 |

| c.364C>T | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1.000 |

| c.365G>A | 3 (7.9) | 3 (2.5) | 0.293 |

| c.623G>C | 2 (5.3) | 9 (7.4) | 0.934 |

| CTRC mutations | 1 (2.6) | 5 (4.1) | 1.000 |

| c.180C>T | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.3) | 0.573 |

| c.181G>A | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1.000 |

| c.649G>A | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.238 |

| c.703G>A | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.238 |

| CFTR mutations | 2 (5.3) | 14 (11.5) | 0.421 |

| c.1865G>A | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1.000 |

| c.2909G>A | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | 1.000 |

| c.2936A>C | 1 (2.6) | 1 (0.8) | 0.420 |

| c.3205G>A | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | 1.000 |

| c.3635delT | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1.000 |

| c.4056G>C | 1 (2.6) | 7 (5.7) | 0.733 |

CP, chronic pancreatitis.

Risk factors associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes

The impact of genetic factors and clinical features on adverse pregnancy outcomes was further explored in univariate and multivariate analyses. In univariate analyses, harboring gene mutations (P = 0.017) and acute pain attack during pregnancy (P = 0.003) were associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. These variables were then included in a subsequent multivariate analysis. In the final multivariate logistic regression model, harboring gene mutations (OR, 2.52; 95%CI, 1.08–5.90; P = 0.033) and acute pain attack during pregnancy (OR, 5.63; 95%CI, 1.68–18.87; P = 0.005) were identified as independent risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes (Table 4).

Table 4.

The impact of genetic factors and clinical features on adverse pregnancy outcomes in CP (n = 160)

| Comparison of characteristics | Univariate analyses | Multivariate analyses | ||||

| Patients with adverse pregnancy outcomes (n = 38) | Patients without adverse pregnancy outcomes (n = 122) | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 1 (2.6) | 3 (2.5) | 1.07 (0.11–10.62) | 0.953 | ||

| Alcohol use, n (%) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (0.8) | 3.27 (0.20–53.57) | 0.406 | ||

| Age at first pregnancy, yr (IQR) | 25.0 (23.0–28.0) | 24.0 (22.0–27.0) | 1.09 (0.98–1.20) | 0.113 | ||

| Age at first delivery, yr (IQR) | 26.0 (24.0–28.8) | 25.0 (22.0–27.0) | 1.11 (1.00–1.23) | 0.063 | ||

| Onset symptoms, n (%) | ||||||

| Pain | 12 (31.6) | 38 (31.1) | Reference | |||

| AP | 20 (52.6) | 58 (47.5) | 1.09 (0.48–2.49) | 0.834 | ||

| Diabetes | 4 (10.5) | 10 (8.2) | 1.27 (0.34–4.78) | 0.727 | ||

| Steatorrhea | 1 (2.6) | 9 (7.4) | 0.35 (0.04–3.07) | 0.344 | ||

| Asymptomatic | 1 (2.6) | 7 (5.7) | 0.45 (0.05–4.06) | 0.478 | ||

| Etiology of CP, n (%) | ||||||

| Idiopathic | 31 (81.6) | 100 (82.0) | Reference | |||

| Alcoholic | 2 (5.3) | 2 (1.6) | 3.23 (0.44–23.86) | 0.251 | ||

| Hereditary | 1 (2.6) | 5 (4.1) | 0.65 (0.07–5.73) | 0.694 | ||

| Othersa | 4 (10.5) | 15 (12.3) | 0.86 (0.27–2.78) | 0.802 | ||

| Gene mutations, n (%) | 29 (76.3) | 66 (54.1) | 2.73 (1.19–6.26) | 0.017 | 2.52 (1.08–5.90) | 0.033 |

| Acute pain attack during pregnancy, n (%) | 8 (21.1) | 5 (4.1) | 6.24 (1.90–20.45) | 0.003 | 5.63 (1.68–18.87) | 0.005 |

AP, acute pancreatitis; CI, confidence interval; CP, chronic pancreatitis; IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio.

Other etiology of CP includes abnormal anatomy of pancreatic duct and trauma.

Impact of SPINK1 mutations on pregnancy outcomes

Next, the impact of SPINK1 mutations on pregnancy outcomes was explored. The characteristics and pregnancy outcomes of patients with and without SPINK1 mutations are shown in Supplementary Digital Content (see Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B93). Patients with SPINK1 mutations had a significantly higher incidence of CP-associated adverse pregnancy outcomes than those without gene mutations (32.8% vs 13.8%, P = 0.010). The impact of SPINK1 mutations on adverse pregnancy outcomes was then explored. In the final multivariate logistic regression model, harboring SPINK1 mutations (OR, 2.60; 95%CI, 1.06–6.37; P = 0.037) and acute pain attack during pregnancy (OR, 5.50; 95%CI, 1.60–18.92; P = 0.007) were identified as independent risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes (Table 5).

Table 5.

The impact of SPINK1 mutations on adverse pregnancy outcomes (n = 132)

| Comparison of characteristics | Univariate analyses | Multivariate analyses | ||||

| Patients with adverse pregnancy outcomes (n = 31) | Patients without adverse pregnancy outcomes (n = 101) | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (2.0) | 1.65 (0.15–18.84) | 0.687 | ||

| Alcohol use, n (%) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (1.0) | 3.33 (0.20–54.91) | 0.400 | ||

| Age at first pregnancy, yr (IQR) | 25.0 (23.0–28.0) | 24.0 (22.0–27.8) | 1.09 (0.97–1.22) | 0.136 | ||

| Age at first delivery, yr (IQR) | 25.0 (23.0–28.0) | 24.0 (22.0–27.8) | 1.11 (0.99–1.24) | 0.082 | ||

| Onset symptoms, n (%) | ||||||

| Pain | 11 (35.5) | 33 (32.7) | Reference | |||

| AP | 14 (45.2) | 46 (45.5) | 0.91 (0.37–2.26) | 0.844 | ||

| Diabetes | 4 (12.9) | 8 (7.9) | 1.50 (0.38–5.97) | 0.565 | ||

| Steatorrhea | 1 (3.2) | 7 (6.9) | 0.43 (0.05–3.88) | 0.451 | ||

| Asymptomatic | 1 (3.2) | 7 (6.9) | 0.43 (0.05–3.88) | 0.451 | ||

| Etiology of CP, n (%) | ||||||

| Idiopathic | 24 (77.4) | 84 (83.2) | Reference | |||

| Alcoholic | 2 (6.5) | 2 (2.0) | 3.50 (0.47–26.17) | 0.222 | ||

| Hereditary | 1 (3.2) | 1 (1.0) | 3.50 (0.21–58.06) | 0.382 | ||

| Othersa | 4 (12.9) | 14 (13.9) | 1.00 (0.30–3.32) | 1.000 | ||

| SPINK1 mutations, n (%) | 22 (71.0) | 45 (44.6) | 3.04 (1.28–7.26) | 0.012 | 2.60 (1.06–6.37) | 0.037 |

| Acute pain attack during pregnancy, n (%) | 8 (25.8) | 5 (5.0) | 6.68 (2.00–22.32) | 0.002 | 5.50 (1.60–18.92) | 0.007 |

AP, acute pancreatitis; CI, confidence interval; CP, chronic pancreatitis; IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio.

Other etiology of CP includes abnormal anatomy of pancreatic duct and trauma.

Impact of non-SPINK1 mutations on pregnancy outcomes

The characteristics and pregnancy outcomes of patients with and without non-SPINK1 mutations are shown in Supplementary Digital Content (see Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Table 5, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B93). Patients with non-SPINK1 mutations had fewer deliveries (P = 0.023). There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in CP-associated adverse pregnancy outcomes nor were there any differences in adverse maternal or fetal outcomes. Harboring non-SPINK1 mutations had no effect on adverse pregnancy outcomes in univariate logistic analyses (see Supplementary Table 6, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B93). We further performed multiple comparisons of the characteristics and pregnancy outcomes of CP patients with SPINK1 mutations, CP patients with non-SPINK1 mutations, and CP patients without gene mutations. The main results were consistent with the above-mentioned subgroup analyses (see Supplementary Table 7, Supplementary Table 8, http://links.lww.com/CTG/B93).

DISCUSSION

This study is the first prospective cohort study to explore the effects of genetic factors on pregnancy outcomes among CP patients. Data of 160 Chinese female CP patients were analyzed, and the results showed that rare pathogenic variants in major susceptibility genes for CP, especially SPINK1, were correlated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Moreover, acute pain attack during pregnancy was also a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Pregnancy, as well as pregnancy planning and outcomes, is a pivotal issue for women and families. A pre-existing or comorbid condition can be concerning for patients and can affect pregnancy outcomes. As a progressive inflammatory disease, CP may affect women of childbearing age. Thus, understanding of the associations between CP and pregnancy outcomes is necessary. Based on a well-phenotyped Chinese cohort of CP patients, this study found that the incidence of CP-associated adverse pregnancy outcomes was 23.8%. The 2 most serious adverse events, CP-associated preterm delivery and abortion, occurred in 8.8% and 12.5% of patients, respectively. These rates are higher than the rates reported in the Chinese general population (6.1% (21) and 9.0% (22), respectively). This confirms that CP is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. More careful assessment and monitoring of maternal and fetal conditions in CP patients are vital to improve pregnancy outcomes.

Of note, this study is the first to explore the effects of CP-susceptibility gene mutations on pregnancy outcomes. Although many studies have confirmed the effects of genetic factors on the occurrence and progression of CP (7,9), the relationship between pregnancy outcomes and CP-susceptibility genes has not attracted enough attention in clinical practice. In this study, patients harboring mutations in CP-susceptibility genes had a higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, with an adjusted OR of 2.52. Furthermore, patients with gene mutations were nearly 4 times more likely to experience CP-associated preterm delivery (12.6% vs 3.1%) and abortion (17.9% vs 4.6%) than those without, which was a striking difference. Preterm infants have an increased risk of short- and long-term morbidities, including respiratory distress syndrome, neurodevelopmental impairment, and glucose intolerance (21). In addition, complications associated with preterm birth are the leading cause of death in neonates and children younger than 5 years (21). Therefore, the effects of genetic factors on pregnancy outcomes are important. The identification of the harmful effects of variants in CP-susceptibility genes on pregnancy outcomes further stresses the significance of genetic testing for CP-susceptibility genes and also highlights the importance of closely monitoring these patients during pregnancy.

This study further established the harmful impact of SPINK1 mutations on pregnancy outcomes. SPINK1 is the most common CP-susceptibility gene in Chinese CP patients (7). The central role of the SPINK1 protein, which is synthesized in pancreatic acinar cells, is to protect the pancreas from prematurely activated trypsin (23). It has been suggested that most SPINK1 mutations declined inhibitor effects and increased the risk of CP (24). As the most common gene mutation in the current cohort and East Asian populations, SPINK1 c.194 + 2T>C is a loss-of-function variant that may lead to lower mRNA levels than the wildtype because of exon 3 being partially skipped (25). There are several possible reasons why loss-of-function SPINK1 mutations affect pregnancy outcomes. First, normal expression of SPINK1 is indispensable during the growth and development of both humans and animals. Animal experiments have shown that autophagic degeneration of pancreatic cells occurs in Spink1 homozygous deficient mice, resulting in death within 2 weeks of birth (26). Furthermore, our previous study found that mice with the homozygous Spink1 c.194 + 2T>C mutation died soon after birth (27). Second, the expression levels of both Spink1 mRNA and protein were found to increase on days 5–8 in pregnant mice, playing an important role in embryo implantation through their influence on stromal decidualization in mice (28). Another study by Kolho et al (29) also found that low concentrations of SPINK1 in amniotic fluid were associated with fetal malformations, and low values were common in cases with intrauterine fetal death or congenital nephrosis. Based on these evidence, SPINK1 mutations cause a reduction in SPINK1 expression, which may contribute to adverse pregnancy outcomes. Further investigation of the mechanism underlying the adverse effects of SPINK1 mutations on pregnancy outcomes is required. By contrast, non-SPINK1 mutations were not significantly associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes in this study. The null effect might be due to either insufficient statistical power or the low prevalence of these gene mutations in Chinese CP patients.

Another significant finding was that acute pain attack during pregnancy was also found to be a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes. This can be explained as follows. First, studies of pregnant rats with acute pancreatitis have indicated that proinflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress are involved in the development of maternal systemic complications such as lung and renal damage (30). Second, the maternal inflammation in pregnancy may program fetal inflammatory pathways and epigenetic machinery, resulting in adverse fetal outcomes (31). Furthermore, several animal model studies have referred to pancreatitis-related placenta injury. For example, Zuo et al (32) conducted a thorough investigation of pancreatitis-related placental injury and suggested that placental injury during pancreatitis might be related to the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinases pathway.

Notably, in our cohort, there were no associations between adverse pregnancy outcomes and pancreatic exocrine and endocrine insufficiency (P = 0.161 and 1.000, respectively; data not shown). In terms of steatorrhea, given that the CP patients with exocrine insufficiency in this cohort routinely received pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy according to the published guideline (12), the impacts of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency on pregnancy outcomes might be negligible. As for the association between pancreatogenic diabetes and GDM, we found no statistically significant relationship. This could be explained as follows: The mechanism of pancreatogenic diabetes involves pancreatic islet dysfunction and islet loss as a result of diseases of the exocrine pancreas (2), whereas GDM occurs mainly because of decreased insulin sensitivity in pregnant females (33).

There are several limitations of this study that should be noted. First, the relatively high rate of loss to follow-up is due to difficult access to pregnancy outcome data, which is considered privileged in Chinese culture. Second, this study only examined 4 major susceptibility genes for CP; other CP-susceptibility genes, such as CPA1 (encoding carboxypeptidase A1) (34), were not examined in this study. Nonetheless, these gene variants account for a low proportion of cases and have not been found to predispose Chinese individuals to CP in our previous studies (35,36). In the future, prospective multicenter studies with larger sample sizes and different ethnic backgrounds are warranted.

In conclusion, the incidence of CP-related adverse pregnancy outcomes was 23.8% in this well-phenotyped cohort of Chinese female CP patients. Rare pathogenic variants in major susceptibility genes for CP, especially SPINK1, were associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Furthermore, pain attack during pregnancy was identified as a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Genetic testing is highly recommended in CP patients, especially for females who plan to have a child. A thorough and accurate understanding of genetic predisposition is essential to establishing early surveillance strategies for high-risk populations.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Guarantors of the article: Wen-Bin Zou, MD, and Zhuan Liao, MD.

Specific author contributions: D.W.: study design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and final approval of the manuscript. N.R.: analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript. Y.W.: study design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript. G.M. and T.S.: acquisition of data, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript. S.X. and A.Y.: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript. L.W. and L.H.: acquisition of data, resources, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript. Z.L.: study concept, supervision of the study, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript. W.Z. and Z.L.: study concept and design, acquisition of funding, critical revision, and final approval of the manuscript.

Financial support: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 81970560, 82222012 and 82120108006) and the Scientific Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Committee (no. 201901070007E00052).

Potential competing interests: All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Changhai Hospital (CHEC2020-008).

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT06055595.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS KNOWN

✓ Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

✓ The effects of CP-susceptibility gene mutations on pregnancy outcomes remain unknown.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

✓ CP-susceptibility gene mutations, especially SPINK1 mutations, significantly increased the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

✓ Acute pain attack during pregnancy was also a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes.

✓ Genetic testing and management of acute pain attack are highly recommended in female CP patients who plan to have a child.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL accompanies this paper at http://links.lww.com/CTG/B93.

Di Wu, Nan Ru, and Yuan-Chen Wang contributed equally to this article and share cofirst authorship.

Contributor Information

Di Wu, Email: wdee1@foxmail.com.

Nan Ru, Email: runan@smmu.edu.cn.

Yuan-Chen Wang, Email: wangyuanchen@smmu.edu.cn.

Guo-Xiu Ma, Email: maguoxiu@126.com.

Tian-Yu Shi, Email: 407499735@qq.com.

Si-Huai Xiong, Email: sihuaixiong99@163.com.

Ai-Jun You, Email: youaijun@yeah.net.

Lei Wang, Email: comwanglei@smmu.edu.cn.

Liang-Hao Hu, Email: lianghao-hu@hotmail.com.

Zhao-Shen Li, Email: zhaoshenli@smmu.edu.cn.

Wen-Bin Zou, Email: dr.wenbinzou@hotmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singh VK, Yadav D, Garg PK. Diagnosis and management of chronic pancreatitis: A review. JAMA 2019;322(24):2422–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyer G, Habtezion A, Werner J, et al. Chronic pancreatitis. Lancet 2020;396(10249):499–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ru N, Xu XN, Cao Y, et al. The impacts of genetic and environmental factors on the progression of chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;20(6):e1378–e1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahapatra SJ, Midha S, Teja GV, et al. Clinical course of chronic pancreatitis during pregnancy and its effect on maternal and fetal outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol 2021;116(3):600–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rana A, Sharma S, Qamar S, et al. Chronic pancreatitis in females is not associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes: A retrospective analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2023;57(5):531–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niu C, Zhang J, Zhu K, et al. The hidden dangers of chronic pancreatitis in pregnancy: Evidence from a large-scale population study. Dig Liver Dis 2023;55(12):1712–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zou WB, Tang XY, Zhou DZ, et al. SPINK1, PRSS1, CTRC, and CFTR genotypes influence disease onset and clinical outcomes in chronic pancreatitis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2018;9(11):204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayerle J, Sendler M, Hegyi E, et al. Genetics, cell biology, and pathophysiology of pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2019;156(7):1951–68.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller N, Sarantitis I, Rouanet M, et al. Natural history of SPINK1 germline mutation related-pancreatitis. EBioMedicine 2019;48:581–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tandon RK, Sato N, Garg PK, et al. Chronic pancreatitis: Asia-Pacific consensus report. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;17(4):508–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Diabetes Association.Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2012;35(Suppl 1):S64–S71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zou WB, Ru N, Wu H, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic pancreatitis in China (2018 edition). Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2019;18(2):103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, et al. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008;371(9606):75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 190: Gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131(2):e49–e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood AM, Livingston EG, Hughes BL, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: A review of diagnosis and management. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2018;73(2):103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ACOG. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' task force on hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122(5):1122–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Global WHO. Nutrition targets 2025: low birth weight policy brief (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-14.5) (2014). Accessed October 23, 2023.

- 18.Wang H, Gao H, Chi H, et al. Effect of levothyroxine on miscarriage among women with normal thyroid function and thyroid autoimmunity undergoing in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;318(22):2190–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldkamp ML, Carey JC, Byrne J, et al. Etiology and clinical presentation of birth defects: Population based study. BMJ 2017;357:j2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 102: Management of stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113(3):748–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng K, Liang J, Mu Y, et al. Preterm births in China between 2012 and 2018: An observational study of more than 9 million women. Lancet Glob Health 2021;9(9):e1226–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rai R, Regan L. Recurrent miscarriage. Lancet 2006;368(9535):601–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Threadgold J, Greenhalf W, Ellis I, et al. The N34S mutation of SPINK1 (PSTI) is associated with a familial pattern of idiopathic chronic pancreatitis but does not cause the disease. Gut 2002;50(5):675–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szabo A, Toldi V, Gazda LD, et al. Defective binding of SPINK1 variants is an uncommon mechanism for impaired trypsin inhibition in chronic pancreatitis. J Biol Chem 2021;296:100343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou WB, Boulling A, Masson E, et al. Clarifying the clinical relevance of SPINK1 intronic variants in chronic pancreatitis. Gut 2016;65(5):884–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohmuraya M, Hirota M, Araki M, et al. Autophagic cell death of pancreatic acinar cells in serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 3-deficient mice. Gastroenterology 2005;129(2):696–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun C, Liu M, An W, et al. Heterozygous Spink1 c.194+2T>C mutant mice spontaneously develop chronic pancreatitis. Gut 2020;69(5):967–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen W, Han BC, Wang RC, et al. Role of secretory protease inhibitor SPINK3 in mouse uterus during early pregnancy. Cell Tissue Res 2010;341(3):441–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolho KL. Kazal type trypsin inhibitor in amniotic fluid in fetal developmental disorders. Prenat Diagn 1986;6(4):299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi X, Hu Y, Pu N, et al. Risk factors for fetal death and maternal AP severity in acute pancreatitis in pregnancy. Front Pediatr 2021;9(9):769400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao J, Liu Y, Zhang Y, et al. Retrospective analysis of the clinical features and pregnancy outcomes in 124 pregnant patients with non-obstetric acute abdomen. Altern Ther Health Med 2023;29(8):644–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zuo T, Yu J, Wang WX, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinases are activated in placental injury in rat model of acute pancreatitis in pregnancy. Pancreas 2016;45(6):850–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johns EC, Denison FC, Norman JE, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus: Mechanisms, treatment, and complications. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2018;29(11):743–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Witt H, Beer S, Rosendahl J, et al. Variants in CPA1 are strongly associated with early onset chronic pancreatitis. Nat Genet 2013;45(10):1216–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu H, Zhou DZ, Berki D, et al. No significant enrichment of rare functionally defective CPA1 variants in a large Chinese idiopathic chronic pancreatitis cohort. Hum Mutat 2017;38(8):959–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou WB, Boulling A, Masamune A, et al. No association between CEL-HYB hybrid allele and chronic pancreatitis in Asian populations. Gastroenterology 2016;150(7):1558–60.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]