Abstract

Introduction:

Since human papillomavirus vaccine introduction, incidence rates of cervical precancers have decreased; however, the vaccine’s impact on noncervical anogenital precancers has not been shown. These precancers are identified opportunistically and are not collected routinely by most cancer registries.

Methods:

This study examined the incidence rates of high-grade (intraepithelial lesions grade 3) vulvar, vaginal, and anal precancers among persons aged 15–39 years using 2000–2017 data from select cancer registries covering 27.8% of the U.S. population that required reporting of these precancers. Trends in incidence rates were evaluated with Joinpoint regression. Analyses were conducted in 2020.

Results:

High-grade vulvar precancer rates declined by 21.0% per year after human papillomavirus vaccine introduction among females aged 15–19 years. In addition, high-grade vaginal precancer rates declined by 19.1% per year among females aged 15–29 years after human papillomavirus vaccine introduction. Compared with that in the prevaccine period when high-grade anal precancer rates were increasing, anal precancer rates after human papillomavirus vaccine introduction were stable among females aged 15–29 years and among males aged 30–39 years. Among males aged 15–29 years, the rates increased over the entire period but less so after human papillomavirus vaccine introduction.

Conclusions:

Opportunistically-detected high-grade vulvar and vaginal precancers among females aged 15–29 years decreased and anal precancers stabilized in years after the introduction of the human papillomavirus vaccine, which is suggestive of the impact of the vaccine on noncervical human papillomavirus cancers.

INTRODUCTION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) causes nearly all cervical cancers and a large proportion of vaginal, vulvar, and anal cancers.1 In contrast to cervical cancer,2 understanding of carcinogenic progression at noncervical anogenital sites is limited because screening is not routinely performed and detection is opportunistic. Since the introduction of routine HPV vaccination at age 11–12 years (2006 for girls and 2011 for boys) in the U.S., decreases occurred in vaccine-type HPV infections,3,4 anogenital warts,5 cervical precancers,6–8 and invasive cervical cancers.9 Population-level impact of HPV vaccine on vulvar, vaginal, and anal precancers is unknown because few registries collect these cases. Published U.S. incidence trends of vulvar and anal precancers10–12 have not yet examined the rates in the years after HPV vaccine implementation or among younger cohorts more likely to be vaccinated. This study used population-based cancer registries and examined recent trends in high-grade vulvar, vaginal, and anal precancers among persons aged 15–39 years in the U.S.

METHODS

This study included data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program during 2000–2017 from 18 central cancer registries covering 27.8% of the U.S. population. Most cancer registries stopped routinely collecting high-grade cervical precancer data in 1996, but SEER registries continued to require reporting of high-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (VIN3), vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia Grade 3 (VAIN3), and anal intraepithelial neoplasia Grade 3 (AIN3).13 Noninvasive cases were identified using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition site Codes C51 (VIN3), C52 (VAIN3), and C21 and C20.9 (AIN3), and histology codes were limited to squamous cell histology (8050–8084 and 8120–8131).

Incidence rates per 100,000 population were calculated using SEER*Stat, version 8.3.8,14 and were stratified by age group (15 –29 and 30–39 years). The larger number of VIN3 cases allowed more detailed age categories (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39 years). The year of diagnosis was grouped into 2-year intervals because of sparse data. Changes in rates during 2000–2017 were evaluated using Joinpoint regression, version 4.8.0.1,15 which fits a series of joined straight lines on a logarithmic scale to the trends in the annual age-standardized rates.16 Year of diagnosis was included as a continuous independent variable using the midpoint of each interval. A total of 9 observation points allowed a maximum of 1 Joinpoint (2-line segments). The line segment trend was used to quantify the annual percentage change (APC). The average APC (AAPC) for 2000–2017 was calculated using a weighted average of the slope coefficients of the underlying Joinpoint regression line with the weights equal to the length of each segment over the interval. The Bayesian Information Criterion was used for model selection and the empirical quantile method (Method 2) to calculate APC CIs.17 Rates were considered to increase if the APC was >0 and to decrease if it was <0 (p<0.05); otherwise, rates were considered stable. All analyses were conducted in 2020.

RESULTS

During 2000–2017, a total of 6,128 VIN3, 945 VAIN3, 462 AIN3 cases among females and 2,154 AIN3 cases among males were identified. Most VIN3 and VAIN3 cases were among females aged 30–39 years (62.8% and 60.7%, respectively) and non-Hispanic White females (64.6% and 61.1%, respectively). Most AIN3 cases were among females and males aged 30–39 years (77.9% and 77.1% respectively), with non-Hispanic White persons comprising the largest group (55.8% female and 46.0% male) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Persons Aged 15–39 Years With High-Grade Precancers—U.S., 2000–2017

| Characteristics | VIN3 (n=6,128), n (%) | VAIN3 (n=945), n (%) | AIN3 (F) (n=462), n (%) | AIN3 (M) (n=2,154), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age, years | ||||

| 15–29 | 2,279 (37.2) | 371 (39.3) | 102 (22.1) | 626 (29.1) |

| 15–19 | 277 (4.5) | NA | NA | NA |

| 20–24 | 923 (15.1) | NA | NA | NA |

| 25–29 | 1,079 (17.6) | NA | NA | NA |

| 30–39 | 3,849 (62.8) | 574 (60.7) | 360 (77.9) | 1,528 (70.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 3,957 (64.6) | 577 (61.1) | 258 (55.8) | 990 (46.0) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 751 (12.3) | 85 (9.0) | 89 (19.3) | 514 (23.9) |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native | 62 (1.0) | 8 (0.8) | 5 (1.1) | 13 (0.6) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander | 256 (4.2) | 59 (6.2) | 23 (5.0) | 80 (3.7) |

| Hispanic (all races) | 714 (11.7) | 145 (15.3) | 72 (15.6) | 388 (18.0) |

| Non-Hispanic unknown race | 388 (6.3) | 71 (7.5) | 15 (3.2) | 169 (7.8) |

Source: National Cancer Institute’s SEER Program.

ICD-O-3 site codes for VIN3 (ICD-O-3 site Code C52.9), VAIN3 (ICD-O-3 site Codes C51.0-C51.9), and AIN3 (including rectal SCC; ICD-O-3 site Codes C20.9 and C21.0-C21.9 are limited to SCCs; ICD-O-3 histology Codes 8050–8084 and 8120–8131). This includes 18 SEER cancer registries that cover 27.8% of the U.S. population.

AIN3, anal intraepithelial neoplasia Grade 3; F, female; ICD-O-3, International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition; M, male; NA, not applicable; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; VAIN3, vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia Grade 3; VIN3, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia Grade 3.

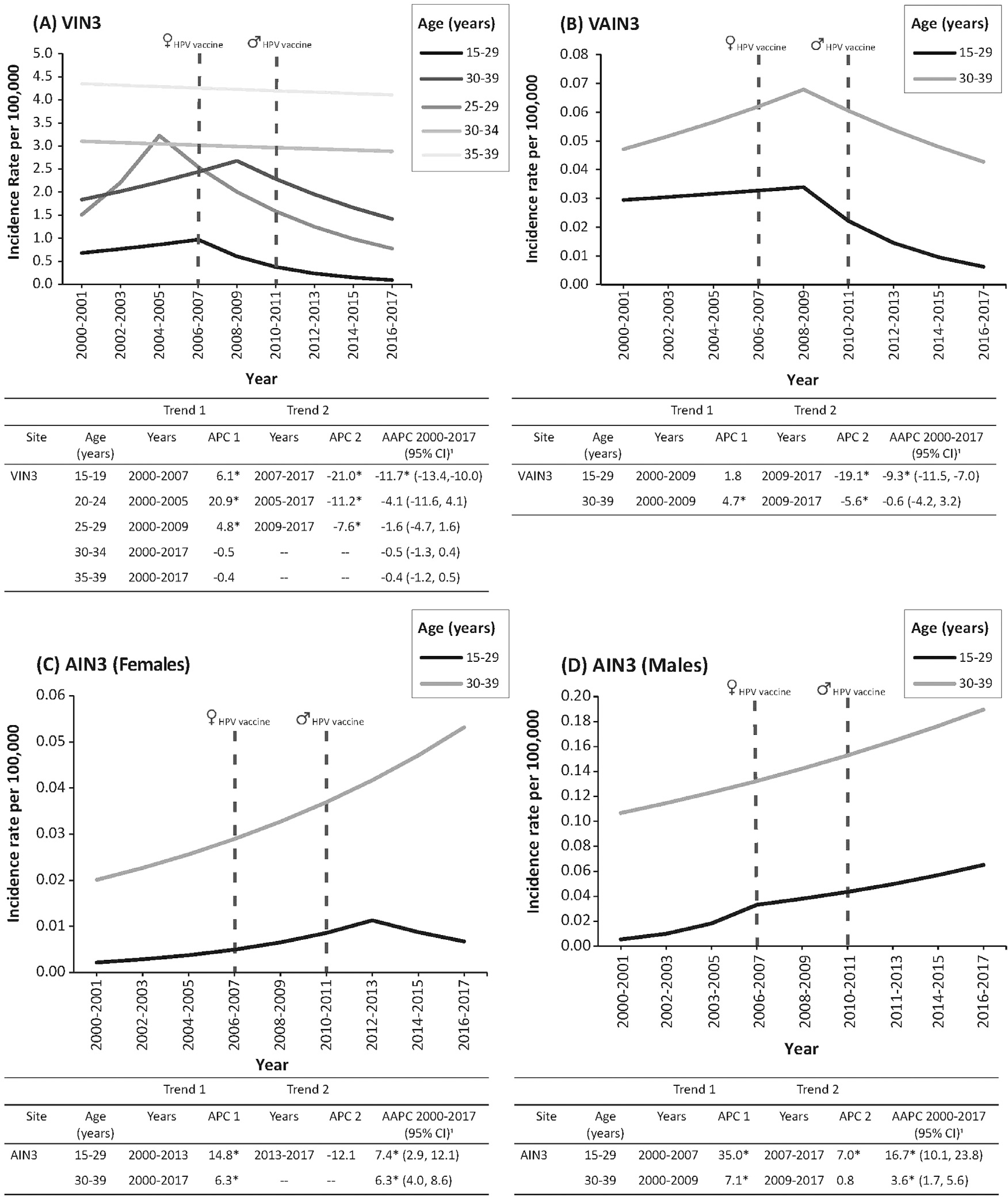

Incidence rates of VIN3 increased by 6.1% (2000 –2007), 20.9% (2000–2005), and 4.8% (2000–2009) per year among females aged 15–19, 20–24, and 25–29 years, respectively (Figure 1). VIN3 rates then decreased by 21% (2007–2017), 11.2% (2005–2017), and 7.6% (2009–2017) per year among females aged 15–19, 20–24, and 25–29 years, respectively. Among females aged 30–34 and 35–39 years, VIN3 rates were stable.

Figure 1.

Incidence trends for noncervical high-grade anogenital precancers by age. Results are shown for (A) vulvar precancers (VIN3); (B) vaginal precancers (VAIN3); (C) anal precancers (AIN3) among females; and (D) anal precancers (AIN3) among males.

Note: For all trend graphs, solid lines represent trends in incidence rates. Vertical dashed lines indicate when the recommendation for routine HPV vaccination began for females (June 2006) and for males (October 2011). In each graph, the APC in specific trend segments from 2000 to 2017 are shown, which were calculated using Joinpoint regression. Asterisk (*) indicates that APC is significant at p<0.05.

AIN3, anal intraepithelial neoplasia Grade 3; APC, annual percentage change; AAPC, average annual percent change; HPV, human papillomavirus; IPV, inactivated polio vaccine; NS, not significant; VAIN3, vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia Grade 3; VIN3, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia Grade 3.

During 2000–2009, VAIN3 rates were stable among females aged 15–29 years and increased by 4.7% per year among females aged 30–39 years. The rates then decreased by 19.1% per year (2009–2017) and 5.6% per year (2009–2017) among females aged 15–29 and 30–39 years, respectively.

The rates of AIN3 increased by 14.8% per year during 2000–2013 and were stable during 2013–2017 among females aged 15–29 years. Among females aged 30–39 years, the rates increased by 6.3% per year during 2000–2017. AIN3 rates increased by 35.0% per year during 2000–2007 and increased by 7.0% per year during 2007–2017 among males aged 15–29 years. Among males aged 30–39 years, the rates increased by 7.1% per year during 2000–2009 and were stable during 2009–2017.

DISCUSSION

After HPV vaccine introduction, the largest decreases in incidence rates of VIN3 and VAIN3 occurred among the youngest females. These declines are similar to those observed among high-grade cervical precancers after HPV vaccine introduction6–8 and may suggest vaccine impact. In addition, after a prevaccination period when AIN3 rates increased, the rates were stable among females aged 15–29 years and among males aged 30–39 years after HPV vaccine introduction.

U.S. HPV vaccine coverage has been increasing since its introduction: in 2019, a total of 69.9% of female adolescents and 66.3% of male adolescents had received at least 1 dose.18 Decreases in the incidence of HPV infection,3 anogenital warts,19 and cervical precancers7,8 have been observed within 4 years of HPV vaccine introduction, attributable to both direct vaccine protection and herd immunity. Among cervical precancers, the largest decreases in the incidence have been found among younger females, who are more likely to have been vaccinated.6–8 Our study findings support that decreasing incidence may also be occurring among the youngest age groups for other HPV-associated precancers, especially vaginal and vulvar precancers. The story is a bit more complicated with AIN3 because the rates stabilized after HPV vaccine introduction among women aged 15–29 years and males aged 30–39 years but without significant declines. In addition, AIN3 rates among younger males continued to increase but at a lower rate than before HPV vaccine introduction. These findings may be due to very few diagnosed cases among younger females, a later recommendation for routine vaccination among males, and cases occurring among males who may have not benefited directly from herd immunity.

Although routine screening is not recommended for anogenital cancers other than cervical cancer, these precancers can be diagnosed opportunistically during cervical cancer screening. Changes in screening guidelines and recommendations20 may have affected the detection of VIN3, VAIN3, and AIN3 among women. Higher AIN3 detection among males compared to females could be a result of increased anal cytologic screening in geographic areas with a high prevalence of HIV infection.11 Nonsystematic detection of these endpoints adds variation to the time interval between incidence and detection that could affect the reliability of the trends in diagnosis to reflect early HPV vaccine impact. A clinical trial of HPV efficacy against VIN3 and AIN3 is in progress.21

Limitations

This study had at least 3 limitations. First, most cancer registries stopped collecting cervical precancer data in 1996 because of concerns about appropriate case definitions, diagnostic terminology changes, and increased diagnosis or treatment in outpatient settings.22 These changes may have resulted in decreased reporting of VIN3, VAIN3, and AIN3. Second, age groups were based on sparse data that were not optimized for evaluating vaccine impact. Third, factors not routinely collected by SEER, including vaccination status, HPV type, screening, and HIV status, could not be examined. The strength of this study was the use of high-quality population-based cancer registry data designed to be representative of the U.S. general population. Cancer registries outside of the SEER program also collect VIN3, VAIN3, and AIN3 data but are not reportable at the federal level. Continued collection of these data in sentinel sites and expanding reportability could enhance the ability to examine the impact of HPV vaccine as vaccinated cohorts enter screening programs.

CONCLUSIONS

Decreasing rates in VIN3 and VAIN3 among younger age groups is analogous to decreases observed in cervical precancers, which have been attributed to the introduction of the HPV vaccine. This is a key step toward building population-level data on the impact of HPV vaccine in noncervical HPV-associated anogenital precancers. In addition, anal precancers stabilized in the years after HPV vaccine introduction, which is a promising finding. Continued collection of precancer data by sentinel cancer registry sites will be important to examining HPV impact among HPV-associated anogenital cancers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Funding support for the primary author was received from the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, an asset of the U.S. Department of Energy.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

CREDIT AUTHOR STATEMENT

Jacqueline Mix: Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Writing - original draft. Mona Saraiya: Conceptualization; Supervision; Writing - review & editing. Virginia Senkomago: Methodology; Writing - review & editing. Elizabeth R. Unger: Writing - review & editing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saraiya M, Unger ER, Thompson TD, et al. U.S. assessment of HPV types in cancers: implications for current and 9-valent HPV vaccines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(6):djv086. 10.1093/jnci/djv086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiffman M, Doorbar J, Wentzensen N, et al. Carcinogenic human papillomavirus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16086. 10.1038/nrdp.2016.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliver SE, Unger ER, Lewis R, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus among females after vaccine introduction-National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2003–2014. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(5):594–603. 10.1093/infdis/jix244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gargano JW, Unger ER, Liu G, et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus in males, United States, 2013–2014. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(7):1070–1079. 10.1093/infdis/jix057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flagg EW, Schwartz R, Weinstock H. Prevalence of anogenital warts among participants in private health plans in the United States, 2003–2010: potential impact of human papillomavirus vaccination. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):1428–1435. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gargano JW, Park IU, Griffin MR, et al. Trends in high-grade cervical lesions and cervical cancer screening in 5 states, 2008–2015. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(8):1282–1291. 10.1093/cid/ciy707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benard VB, Castle PE, Jenison SA, et al. Population-based incidence rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in the human papillomavirus vaccine era. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(6):833–837. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleveland AA, Gargano JW, Park IU, et al. Cervical adenocarcinoma in situ: human papillomavirus types and incidence trends in five states, 2008–2015. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(3):810–818. 10.1002/ijc.32340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mix JM, Van Dyne EA, Saraiya M, Hallowell BD, Thomas CC. Assessing impact of HPV vaccination on cervical cancer incidence among women aged 15–29 years in the United States, 1999–2017: an ecologic study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(1):30–37. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-0846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Judson PL, Habermann EB, Baxter NN, Durham SB, Virnig BA. Trends in the incidence of invasive and in situ vulvar carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(5):1018–1022. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000210268.57527.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simard EP, Watson M, Saraiya M, Clarke CA, Palefsky JM, Jemal A. Trends in the occurrence of high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia in San Francisco: 2000–2009. Cancer. 2013;119(19):3539–3545. 10.1002/cncr.28252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saraiya M, Watson M, Wu X, et al. Incidence of in situ and invasive vulvar cancer in the U.S., 1998–2003. Cancer. 2008;113(10 suppl):2865–2872. 10.1002/cncr.23759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adamo M, Dickie L, Ruhl J. SEER program coding and staging manual 2018. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; Published January 1, 2018. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/manuals/2018/SPCSM_2018_maindoc.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.SEER*Stat software. NIH, National Cancer Institute, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/. Accessed August 25, 2020.

- 15.Joinpoint trend analysis software. NIH, National Cancer Institute, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/. Updated March 25, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2021.

- 16.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for Joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates [published correction appears in Stat Med. 2001;20(4):655]. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–351. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HJ, Luo J, Chen HS, et al. Improved confidence interval for average annual percent change in trend analysis. Stat Med. 2017;36 (19):3059–3074. 10.1002/sim.7344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years - United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(33):1109–1116. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6933a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flagg EW, Torrone EA. Declines in anogenital warts among age groups most likely to be impacted by human papillomavirus vaccination, United States, 2006–2014. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(1):112–119. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saraiya M, Steben M, Watson M, Markowitz L. Evolution of cervical cancer screening and prevention in United States and Canada: implications for public health practitioners and clinicians. Prev Med. 2013;57(5):426–433. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stankiewicz Karita HC, Hauge K, Magaret A, et al. Effect of human papillomavirus vaccine to interrupt recurrence of vulvar and anal neoplasia (VIVA): a trial protocol. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e190819. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Association of Cancer Registries, Data Standards Committee. Subcommittee on Noninvasive Cervix Lesions, Working Group on Preinvasive Cervical Cancer Neoplasia and Population-based Cancer Registries: Final Subcommittee Report. Rockville, MD; April 5–6, 1993. [Google Scholar]