Abstract

The epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) resembles that of a sexually transmitted pathogen. However, human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), the proposed cause of KS, is found in semen only infrequently and at low titers. To determine whether HHV-8 was present in the urogenital tract, transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsies were obtained from six men with KS (five with concurrent HIV infection) and four without KS (three with concurrent HIV) and assayed for HHV-8 by PCR. Nine of the 10 men were seropositive for HHV-8. Five of nine HHV-8-seropositive men had HHV-8 DNA detected in prostate tissue by solution-based PCR. All five currently had KS or had it previously. In two subjects, prostate tissue was the only identified source of HHV-8. In situ PCR on serial sections of prostate indicated that HHV-8 infection was localized to discrete areas of the prostate. When detected, HHV-8 DNA was present in the nuclei of >90% of the glandular epithelial cells. In situ hybridization for HHV-8 mRNA revealed that between 1 and 5% of cells harboring HHV-8 DNA expressed viral transcripts associated with HHV-8 replication (T1.1 transcript), while >90% expressed gene products associated with viral latency (T0.7 transcript). Intermittent replication of HHV-8 in the prostate and subsequent shedding of virus in semen may be crucial factors for determining whether HHV-8 can be transmitted through sexual activity.

Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is the most common AIDS-associated malignancy in male homosexuals. Epidemiological evidence suggests that human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated KS may be due to a sexually transmitted pathogen that is distinct from HIV; KS is 10 times more frequent in homosexual men infected with HIV than in men infected through parenteral routes (11). In 1995, Moore and Chang detected DNA sequences of a herpesvirus now known as human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) in KS lesions from men with and without HIV infection (9). The seroprevalence of HHV-8 is higher in groups at risk for sexually transmitted diseases than in those not at risk (5). Several groups have reported the presence of HHV-8 in seminal secretions. However, the frequency, titers, and consistency of such findings have varied greatly, and the source of HHV-8 shedding in semen was unclear (1, 4, 7, 8). The purpose of the present study was to determine if HHV-8 was present in the prostate glands of HHV-8-seropositive men. We report that HHV-8 infects the prostate epithelia of men with KS and appears to be focal in its distribution in the prostate. Virus replication is highly restricted in vivo in such men. HHV-8 was not present in the prostates of HHV-8-seropositive men without KS, suggesting that prostatic tissue is not an early site of viral infection and entry.

The study group included 10 men recruited through advertisements and physician referrals, and the study protocol was approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Committee. Written, informed consent was obtained prior to study enrollment. All of the men had the HIV risk factor of sex with men. Eight were HIV infected; two were HIV seronegative. Prostate samples from four HHV-8-seronegative men who underwent radical prostatectomies were used as PCR and hybridization controls (Table 1). Among the HIV-infected men, CD4 counts ranged from 11 × 106 to 863 × 106/liter. Nine of the men were seropositive for HHV-8, but only six had clinical KS (Table 1). Semen, saliva, and blood were obtained prior to prostate biopsy. Mononuclear cells were separated by density gradient centrifugation, and samples were prepared by methods described previously (6).

TABLE 1.

Participant profiles and solution-based HHV-8 PCR result

| Participant no. | Age (yr) | HHV-8 titer | HIV status | CD4 count × 106/liter | KS site(s) | Results of solution-based HHV-8 PCR

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of prostate samples positive/total no. examined (copy no.)b | Semen | No. of copies

|

|||||||

| Per 106 PBMC | Per ml of saliva | ||||||||

| 1 | 35 | 1:640 | + | 321 | Skin | 2/6c (100) | —e | 33 | 5 × 105 |

| 2 | 45 | 1:640 | + | 477 | Skin | 3/6c (5,000) | NAa | — | 5 × 105 |

| 3 | 48 | 1:160 | + | 11 | Mouth | 0/6 | — | — | — |

| 4 | 36 | 1:320 | + | 60 | Skin | 6/6 (500) | — | — | — |

| 5 | 45 | 1:160 | + | 134 | Skin | 1/6 (50) | — | — | — |

| 6 | 47 | 1:160 | − | 667 | Skin, lymph nodes | 2/6 (100) | — | — | 1 × 106 |

| 7 | 37 | 1:40 | − | NA | None | 0/6 | — | — | — |

| 8 | 57 | 1:40 | + | 473 | None | 0/6 | — | — | — |

| 9 | 55 | 1:40 | + | 466 | None | 0/6 | — | 3.3 × 103 | 2.5 × 105 |

| 10 | 32 | + | 863 | None | 0/6 | — | — | — | |

| 11–14d | 55–69 | − | NA | None | 0/4 | NA | NA | NA | |

NA, not available.

Copy number estimated per 50 ng of tissue.

Evaluated by in situ PCR.

Samples obtained by radical prostatectomy from HHV-8-seronegative men and used for assay controls.

—, negative.

The prostate gland was evaluated systematically by transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy with a Bard Biopty system (Covington, La.) with an 18-gauge needle. Six prostate samples were obtained from each subject. The samples were from the middle, the bladder base, and the apex sections from the left and right sides of the prostate. The specimens were fixed in tissue fixative (Streck Laboratories Inc., Omaha, Nebr.) and embedded in paraffin, and 5-μm-diameter sections were mounted on silane-coated glass microscope slides.

Solution-based PCR methods, controls, and quantification procedures were as reported previously (6). KS1 and KS2 primers were used to amplify the KS330 Bam233 fragment of ORF 26 (9). This laboratory has participated in a collaborative trial evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of PCR-based methods for HHV-8 detection (10). The sensitivity of solution-based PCR was less than 10 copies of HHV-8 DNA per reaction, and there was no cross-reactivity between HHV-8 and other known human herpesviruses (6, 15). Serological tests to detect antibodies to HHV-8 involved the use of an immunofluorescence assay (IFA) for lytic cycle cytoplasmic antigen and were performed as described previously (6, 13). The solution-based and in situ PCR assays were performed independently at separate laboratories by investigators who had no knowledge of the other laboratory’s assay results.

For in situ hybridization, full-length cDNAs (sense and antisense) encoding the HHV-8 T0.7 (155 bp; found in latent cells) and T1.1 (211 bp; found in replicating cells) (16) transcripts were cloned into transcription vectors under the control of T7 and SP6 RNA polymerase promoters (pGEM; Promega, Madison, Wis.). The constructs were linearized and used as templates for in vitro transcription in which digoxigenin (DIG)-11-UTP (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) was incorporated. The resulting DIG-labeled transcripts were precipitated with ethanol and quantified spectrophotometrically. The specificities of the final products were determined by dot blot analysis, and a working concentration was established by hybridization to BCBL-1 cell lines persistently infected with HHV-8 (12).

Serial sections of prostate were deparaffinized, rehydrated in Tris-buffered saline (0.1 M Tris [pH 7.5], 0.1 M NaCl), digested with proteinase K (20 μg/ml at 37°C for 60 min; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), succinylated (5 g of succinic anhydride per liter in 0.1 M triethanolamine [pH 8.0]), and washed in diethyl pyrocarbonate water. The riboprobes (sense and antisense) were applied separately to tissues in a hybridization solution (20% SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 50% formamide, 0.5% Tween-20, 100 mg of sonicated salmon sperm DNA per ml, and 5× Denhardt’s solution) so that the final probe concentration was 50 ng per tissue section. The tissues were hybridized with probe for 4 h at 42°C in a humidified chamber. Slides were then washed in 2× SSC–0.5% Tween-20 for 20 min at 37°C, followed by 0.2× SSC–0.5% Tween-20 for 20 min at room temperature. Hybridized probe was detected with alkaline-phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibodies (1,500 mU/ml) and nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate toluidinium substrate, following the manufacturer’s recommendations (Boehringer Mannheim). The presence of viral nucleic acid was indicated by a purple cell-associated precipitate. Cytospin preparations of BCBL-1 cells and prostate tissue from the four control patients (Table 1, no. 11 to 14) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. In addition, DIG-labeled RNA probes transcribed in sense orientation and probes specific for the antibiotic gene neomycin phosphotransferase (nonsense probes) were used as controls for all hybridizations.

To estimate virus copy number in situ, experiments were performed to evaluate the sensitivities of the T0.7 and T1.1 riboprobes. Briefly, cytospin preparations of BCBL-1 cells were made with untreated (uninduced) cells or cells treated with 12-O-tetradecanoyl phorbol-13-acetate at 20 ng/ml for 5 days (induced) (15) and then subjected to in situ hybridization with the T0.7 and T1.1 riboprobes. Viral RNA was not detected in uninduced cells, which were shown by end-point PCR to have <50 HHV-8 DNA copies per cell. In contrast, >70% of induced cells and >90% of cells in which HHV-8 DNA was amplified by PCR (see below) demonstrated HHV-8 by in situ hybridization with both the T0.7 and T1.1 riboprobes, indicating that >50 HHV-8 copies/cell were required for detection by the RNA probes. This finding is consistent with our previous studies with RNA and similar DIG-labeling strategies indicating probe sensitivities of about 20 RNA copies (2).

For in situ PCR, a solution containing PCR buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.3], 4 mM MgCl2, 0.01% gelatin, 200 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 50 pM KS1 and KS2 primers [9], and Taq polymerase [0.15 U/ml]) was prepared. The primers were specific for the HHV-8 minor capsid protein (GenBank accession no. U18551 [47289–47521]) and upon amplification produced a 233-bp product (9). The PCR mixture was heated to 70°C and applied to deparaffinized and proteinase K-treated (20-μg/ml) tissue sections in volumes that ranged from 30 to 50 μl, depending on the size of the tissue section, and coverslips were placed on top. Coverslips were surrounded with mineral oil, and the slides were placed directly on the aluminum block of the thermocycler (Omnigene; Hybaid, Woodbridge, N.J.). After 25 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min and annealing at 55°C for 2 min, followed by polymerization for 2 min at 72°C, the slides were treated for 5 min with xylenes to remove mineral oil, 5 min in 100% ethanol, and then air dried. The PCR product was detected by in situ hybridization with a cocktail of three DIG-labeled oligonucleotides, all in sense orientation (5′[47308] AGCAGCTGTTGGTGTACCACAT-3′, 5′[47424]-ATCTACTCCAAAATATCGGCCG-3′, 5′[47454]-GATGATGTAAATATGGCGGAAC-3′), all complementary to DNA encoding the HHV-8 minor capsid protein, and all internal to the primer binding sites. The remainder of the procedure, including that for the controls, was as described for in situ hybridization.

Of the 10 men who underwent transrectal prostate biopsy, 9 were seropositive for HHV-8 by IFA to lytic cycle cytoplasmic antigen and 8 had concurrent HIV infection (Table 1). In the nine HHV-8-seropositive men, HHV-8 DNA was detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from two men, in saliva from four men, and in the prostates of five men. Semen from eight of the nine HHV-8-seropositive participants was examined for HHV-8 DNA, and none of the eight specimens demonstrated detectable HHV-8. In contrast, we detected HHV-8 DNA in prostate by solution-based PCR in five of the nine seropositive men, including the one HHV-8-seropositive, HIV-seronegative man. All five men with HHV-8 DNA in prostatic tissue currently had or once had KS. In two of these five men, prostate was the sole body fluid or biopsy source of PCR positivity for HHV-8. None of the three HHV-8-seropositive men without KS exhibited HHV-8 in their prostates; one of these three (no. 9) exhibited HHV-8 in his PBMC and his saliva. The HIV-infected HHV-8-seronegative man (no. 10) who underwent prostatic biopsy exhibited no HHV-8 in any samples. Similarly, none of the control patients (no. 11 to 14) exhibited HHV-8 by either technique. HHV-8 was detected in prostate at relatively low copy numbers (≤5 × 103/per 50 ng of prostatic tissue DNA as assessed by solution-based PCR). In comparison, saliva demonstrated much-higher copy numbers (2.5 × 105 to 1 × 106 copies/ml).

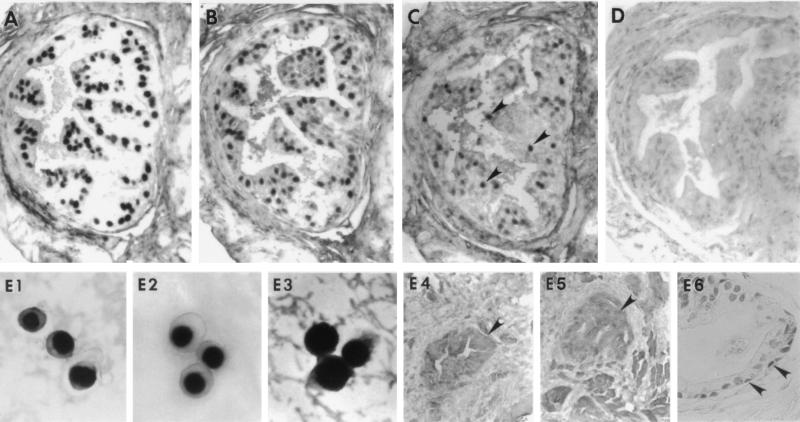

To localize HHV-8 in prostate tissue and define virus-permissive cell types, we performed in situ PCR and in situ hybridization assays for HHV-8 on prostate biopsy samples from two participants (Table 2, participants 1 and 2) who had HHV-8 in prostate by solution-based PCR. Participant 1 had HHV-8 DNA in PBMC, saliva, and prostate, and participant 2 had HHV-8 in saliva and prostate tissue but not in PBMC (Table 1). Epithelial cells from the columnar (luminal) zone and, to a lesser extent, the basilar zone of the prostate glands from both men were shown to harbor HHV-8 DNA by in situ PCR (Fig. 1). In certain fields, HHV-8 DNA was detected by in situ PCR in >90% of glandular epithelial cells. HHV-8 infection of the prostate appeared to be localized; not all biopsies had HHV-8 DNA by either solution-based or tissue-based PCR (Table 2). Hybridization signal following in situ PCR was intranuclear, similar to cytospin preparations of BCBL-1 cells which were employed as positive controls for all hybridization reactions (Fig. 1, E1). Diffusion of amplimers into adjacent tissues was not observed. Moreover, PCR product was clearly retained within the nuclear membrane. Histologic analysis of prostate from participants 1 and 2 revealed no evidence of inflammation or neoplasia.

TABLE 2.

Localization and quantification of HHV-8 in prostate by in situ PCR and solution-based PCR

| Prostate specimen | Results for PCRb

|

|

|---|---|---|

| In situ | Solution-based (no. of copies/50 ng of tissue) | |

| Participant 1 | ||

| Right side | ||

| Bladder base | − | − |

| Middle | − | − |

| Apex | − | − |

| Left side | ||

| Bladder base | + | 100 |

| Middle | + | 5–10 |

| Apex | − | − |

| Participant 2 | ||

| Right side | ||

| Bladder base | − | 5–10 |

| Middle | − | − |

| Apex | −a | 5,000 |

| Left side | ||

| Bladder base | + | − |

| Middle | + | 1,000 |

| Apex | − | − |

Biopsy specimen did not contain glandular prostate.

−, negative; +, positive.

FIG. 1.

Cellular localization of HHV-8 DNA and HHV-8 gene expression in serial sections of prostate obtained by transrectal biopsy from an HHV-8-seropositive, HIV-infected individual (participant 2). (A) HHV-8 DNA tissues were subjected to in situ PCR with primers specific for DNA encoding the HHV-8 minor capsid protein and then hybridized to a cocktail of sense-strand-oriented DIG-labeled oligonucleotide probes that were internal to the primer binding sites. HHV-8 DNA localized to the nucleus and was present in the majority of glandular epithelia within the columnar (luminal) zone. (B, C, and D) Expression of HHV-8 RNA as assayed by in situ hybridization with DIG-labeled antisense RNA probes specific for the T0.7 (B) and T1.1 (C) transcripts. The T0.7 RNA probe, which is encoded and transcribed in high copy number during viral latency, hybridized predominantly within the nucleus of columnar glandular epithelia. The T1.1 transcript, which is associated with virus replication, hybridized to the T1.1 antisense RNA probe, but only within the nucleus (arrowheads). However, signal was weak and sparse and mostly within cells in the columnar zone. Antisense RNA probes (D) of similar length and GC content were constructed against the antibiotic gene neomycin and shown not to hybridize to tissues. (E1 to E6) Higher-power views of the hybridization procedures. (E1) In situ PCR for HHV-8 DNA in BCBL-1 cells. Note that the staining is exclusively intranuclear. (E2) Similarly, phorbol-induced BCBL-1 cells that were hybridized to the T1.1 riboprobe showed only intranuclear staining. (E3) Conversely, BCBL-1 cells that were hybridized with the T0.7 riboprobe had both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining. Glandular prostate (arrowheads) obtained from individuals that were HHV-8 positive by in situ PCR (participant 2) did not hybridize to T0.7 RNA probes transcribed in sense orientation (E4), and tissues from individuals without risk factors for HHV-8 were consistently virus negative by in situ PCR (E5). (E6) HHV-8 DNA was also seen on occasion within the nucleus of basal prostate epithelia (arrowheads) following in situ PCR. There was no histologic evidence of prostatitis or other abnormalities on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining, and HHV-8 was not detected in prostatic stromal cells from any of the study participants. Magnification, ×200 (panels A to D); ×1,000 (panels E1 to E3); ×100 (panels E4 and E5); ×250 (panel E6).

Table 2 compares solution-based and in situ PCR results from each of six prostate samples from these two men. Concordance between the two assays was seen in nine (75%) of 12 specimens. In two specimens, solution-based PCR was positive and in situ PCR was negative. In one of these two specimens, glandular tissue was absent as indicated by histologic exam of the tissue. In another specimen, the in situ PCR was positive and the solution-based assay was negative.

Intense hybridization signal was also present in the nuclei of glandular epithelial cells following hybridization with the T0.7 antisense RNA probe (Fig. 1B, participant 1), a marker for viral latency. In contrast, weak and sparse signals were present in the same tissues, as indicated by reaction with the T1.1 antisense RNA probe (Fig. 1C). Tissues that were hybridized to antisense DIG-labeled RNA showed no signal when developed (Fig. 1D). Additional controls consisted of BCBL-1 cells that were reacted with the T1.1 (Fig. 1, E2) and T0.7 (Fig. 1, E3) riboprobes, the resulting hybrids forming mostly within the nucleus. Signal was also seen in the cytoplasm of cells hybridized to the T0.7 riboprobe, as would be expected with RNA having coding potential. Since nucleic acid within the tissue was not denatured prior to hybridization and there was no detectable hybridization with the sense probes derived from the same clones (Fig. 1, E4), it is viral RNA rather than DNA that is detected with the antisense probes. Moreover, other cell types did not hybridize with the antisense riboprobes and neither did prostate tissues obtained from four HHV-8-seronegative men that were first subjected to in situ PCR (Fig. 1, E5).

Studies concerning the prevalence of HHV-8 in prostate and semen have given diverse and conflicting data (1). Italian investigators have detected HHV-8 in a large proportion of ejaculates (30 of 33; 91%) and prostate specimens (7 of 16; 44%) from men at low risk for HIV infection (8). Corbellino et al. found HHV-8 in five autopsy prostate specimens from HIV-infected men with KS (3). Staskus et al. found that HHV-8 localized within the prostate of three HIV-infected men but also found HHV-8 RNA by in situ hybridization in prostatic autopsy tissue from 9 of 11 adult men without apparent HIV infection, suggesting widespread infection with the virus in the male urogenital tract (14). In contrast, Lebbe et al. did not detect HHV-8 in 22 prostate specimens from HIV-seronegative men without KS (7). Some of the widespread disparity in prevalence rates may be related to laboratory techniques as well as to differences in the geographical distribution of HHV-8 seropositivity.

Our study was initiated because we have detected HHV-8 in semen only rarely among HHV-8-seropositive individuals (4). As such, we designed our study to evaluate HHV-8-seropositive men and to process the prostatic biopsy material in two separate labs by three separate procedures. While the number of patients tested is relatively small, the patients were all enrolled consecutively and evaluated extensively. We evaluated prostate tissue from HIV-infected men with and without KS as well as nearly 60 separate biopsy specimens. Moreover, the biopsy specimens were processed specifically for the in situ hybridization and PCR-based studies outlined.

We detected HHV-8 in histologic sections of prostate but not in the semen of HIV-infected men with clinical KS. HHV-8 DNA was found in the prostates of HHV-8-seropositive men with clinical KS but not in men without KS. All five of the men with HHV-8 present in prostate had HHV-8 titers of ≥1:160, while only one of the four seropositive men without HHV-8 in his prostate had a similarly elevated titer. The virus was not found uniformly throughout the prostate; each man had six biopsies, but only one man demonstrated HHV-8 in all six specimens. The veracity of these findings is strengthened by the fact that our laboratory has passed strict proficiency testing for HHV-8 by PCR (10), the high correlation between the solution-based and in situ PCR results, and the manner in which these assays were performed—by different people, in different laboratories, at different times, and without prior knowledge of the other group’s results. In addition, there was a correlation between the adequacy of the biopsy and the results; tissue which lacked glandular epithelia was generally negative for HHV-8 DNA in both assays.

The HHV-8 T0.7 transcript is widely expressed in KS tumor cells and potentially encodes a small (60-amino-acid) membrane protein of unknown function (16). In contrast, the T1.1 transcript is a marker for virus replication that is expressed at much lower levels in KS tumor cells (16, 17). Intense and widespread hybridization signal was present mostly within the nucleus of prostate epithelium following hybridization with T0.7 antisense RNA probe. Signal was most intense in the columnar (luminal) zone of the glandular prostate. Conversely, very weak and sparse signal was present in the same tissue as demonstrated by reaction with the T1.1 antisense RNA probe, the expression of which is highly restricted and confined within the nucleus. When the same tissues were examined by in situ PCR, the majority of the columnar layer and, to a lesser extent, the basilar layer of glandular prostate epithelium were shown to harbor HHV-8 DNA (Fig. 1, panel E6). Viral nucleic acid was not detected in prostate tissues obtained from men without risk factors for HIV or HHV-8. Furthermore, tissues reacted with sense strand oligonucleotide probes did not reveal hybridization signal. Collectively, these findings suggest that most of the HHV-8-infected glandular epithelial cells were latently infected or contained cells in which virus replication was highly restricted or had an abortive replication cycle.

This low level of viral transcription may be one reason why detection of HHV-8 in semen is uncommon (4). HHV-8 shedding in semen may be only intermittent. As-yet-unidentified cofactors that upregulate HHV-8 expression may influence the presence of virus in and transmission of infection through semen. Fluctuations in virus replication may also be affected by host immunity, as is the case with other herpesviruses. One caveat to our results is that the men provided samples by masturbation, and semen specimens obtained by masturbation might contain fewer prostatic secretions than semen obtained through sexual intercourse. Prostatic massage prior to ejaculation might increase the detection of HHV-8 infection in semen.

The sporadic distribution of HHV-8 infection in the prostate and the finding that prostate tissue was the only body fluid or biopsy source of HHV-8 DNA in two men with skin KS raise several interesting issues regarding the time and means by which HHV-8 colonizes the prostate or male genitourinary tract. HHV-8 infection of prostate may be the result of direct extension of genital infection or due to viremia with primary infection or recurrent viremia with HIV-related immunosuppression. Of note, the men we sampled were younger (median age, 45 years) than the elderly men with benign prostatic hypertrophy or prostate cancer who comprise the usual population with archived prostatic tissue available for study. Older men have a relatively smaller percentage of glandular tissue than our cohort, thus explaining some of the differences between other studies and our own.

In summary, our study suggests that the prostate can be a unique site of HHV-8 infection or one of many sites of HHV-8 replication. It is of interest that among the nine HHV-8-seropositive men described here, one man without clinical KS did have HHV-8 DNA in saliva and PBMC (participant 9), despite the absence of HHV-8 in prostate and semen, suggesting that body reservoirs of HHV-8 other than the prostate may exist. Detailed studies of the tissue distribution of HHV-8 may provide further insight into the pathogenesis and means of transmission of this agent.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paddy O’Hearn, Heather L. Parker, and Matthew Johnson for technical assistance, Bala Chandran for serologic results, and Peter Trethewey and Susan O. Ross for assisting with prostate biopsies.

This study was funded in part by grants CA-15704-245, AI-26503, AI-30731, and CA-70017.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blackbourn D J, Levy J A. Human herpesvirus 8 in semen and prostate. AIDS. 1997;11:249–250. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199702000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brodie S J, Bardsley K D, Diem K, Mecham J O, Norelius S E, Wilson W C. Epizootic hemorrhagic disease: analysis of tissues by amplification and in situ hybridization reveals widespread orbivirus infection at low copy numbers. J Virol. 1998;72:3863–3871. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3863-3871.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbellino M, Poirel L, Bestetti G, Pizzuto M, Aubin J T, Capra M, Bifulco C, Berti E, Agut H, Rizzardini G, Galli M, Parravinci C. Restricted tissue distribution of extralesional Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12:651–657. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diamond C, Huang M-L, Kedes D H, Speck C, Rankin G W, Ganem D, Coombs R W, Rose T M, Krieger J N, Corey L. Absence of detectable human herpes virus eight in the semen of HIV-infected men. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:775–777. doi: 10.1086/517299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kedes D H, Operskalski E, Busch M, Kohn R, Flood J, Ganem D. The seroepidemiology of human herpesvirus 8 (Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus): distribution of infection in KS risk groups and evidence for sexual transmission. Nat Med. 1996;2:918–924. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koelle D M, Huang M-L, Chandran B, Vieira J, Piepkorn M, Corey L. Frequent detection of Kaposi’s Sarcoma associated Herpesvirus (HHV-8) in saliva of human immunodeficiency virus infected men: clinical and immunologic correlates. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:94–102. doi: 10.1086/514045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebbe C, Pellet C, Tatoud R, Agbalika F, Dosquet P, Desgrez J P, Morel P, Calvo F. Absence of human herpesvirus 8 sequences in prostate specimens. AIDS. 1997;11:270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monini P, de Lellis L, Fabris M, Rigolin F, Cassai E. Kaposi’s Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus DNA sequences in prostate tissue and human semen. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1168–1172. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605023341805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore P S, Chang Y. Detection of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in Kaposi’s Sarcoma in patients with and those without HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1181–1185. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pellet, P. E., T. Spira, L. Corey, C. Boshoff, L. de Lellis, M.-L. Huang, J. C. Lin, S. Matthews, P. Monini, P. Rimessi, C. Sosa, C. Wood, and J. A. Stewart. Multi-center comparison of polymerase chain reaction detection of human herpesvirus 8 DNA in semen. J. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Peterman T A, Jaffe H W, Beral V. Epidemiologic clues to the etiology of Kaposi’s sarcoma. AIDS. 1993;7:605–611. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199305000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renne R, Zhong W, Herndier B, McGrath M, Abbey N, Kedes D, Ganem D. Lytic growth of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat Med. 1996;2:342–346. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith M S, Bloomer C, Horvat R, Goldstein E, Casparian J M, Chandran B. Detection of human herpesvirus 8 DNA in Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions and peripheral blood of human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients and correlation with serologic results. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:84–93. doi: 10.1086/514043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Staskus K A, Zhong W, Gebhard K, Herndier B, Wang H, Renne R, Beneke J, Pudney J, Anderson D J, Ganem D, Haase A T. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gene expression in endothelial (spindle) tumor cells. J Virol. 1997;71:715–719. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.715-719.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vieira J, Huang M-L, Koelle D M, Corey L. Transmissible Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in saliva of men with a history of Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Virol. 1997;71:7083–7087. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.7083-7087.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong W, Wang H, Herndier B, Ganem D. Restricted expression of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) genes in Kaposi sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6641–6646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong W, Ganem D. Characterization of ribonucleoprotein complexes containing an abundant polyadenylated nuclear RNA encoded by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) J Virol. 1997;71:1207–1212. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1207-1212.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]