Abstract

Primate polyomavirus genomes all contain an open reading frame at the 5′ end of the late coding region called the agnogene. A simian virus 40 agnoprotein with unknown functions has previously been demonstrated. We now show that a BK virus agnoprotein appears in the perinuclear area and cytoplasm late in the infectious cycle. It is phosphorylated in vivo and coimmunoprecipitates with a subset of host cell proteins.

The primate polyomaviruses constitute a group of three small DNA viruses which naturally infect monkeys (simian virus 40 [SV40]) or humans (BK virus [BKV] and JC virus). Their circular genomes are remarkably similar in both organization and sequence (8, 19). The early region of the genome encodes the large and small T antigens, while the late region, which is transcribed in the opposite direction, encodes the viral structural proteins. In addition, each of the three viruses contains an open reading frame (ORF) at the 5′ end of the late region, potentially coding for a polypeptide of 62 amino acids in SV40, 66 amino acids in BKV, or 71 amino acids in JC virus (8). This ORF is known as the agnogene (9).

An SV40 agnogene product was described in 1981 (21, 22) and called the agnoprotein, although some researchers prefer to call it LP-1 (24). The SV40 agnoprotein is produced late in the infectious cycle (21, 22) and is largely confined to the cytoplasm (26). However, unlike other proteins produced from the SV40 late region, no agnoprotein is detected in virions (21). Mutation of the agnogene ORF did not arrest viral reproduction in vitro, although virus yield was considerably reduced or delayed (2, 24, 25, 33). Published results indicate an agnoprotein-mediated effect(s) at the level of viral assembly (4, 23–25), maturation (18), or release of mature virus (30). However, possible effects on transcription, processing, and translation of late viral proteins have also been suggested (1, 14, 16, 29), and the exact role of the agnoprotein in the SV40 life cycle remains controversial.

Although the agnogene is conserved among the primate polyomaviruses (32, 36), agnoprotein expression has not previously been demonstrated for the two human polyomaviruses. Here we show that the BKV agnoprotein is expressed in BKV-infected cell cultures and that it specifically interacts with a subset of human cellular proteins.

The agnoprotein is expressed in BKV-infected cells.

We examined agnoprotein expression in the highly permissive (30b) human endothelial cell line HUV-EC-C (ATCC CRL 1730). HUV-EC-C cells were cultured in MCDB 105 medium (M-6395; Sigma) supplemented with 30 μg of endothelial cell growth supplement (ECGS; Sigma) per ml, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco BRL), and 10 IU of heparin (Nova) per ml. BKV infection was performed with a gradient-purified batch of the naturally occurring virus strain BKV(TU) (34) at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 to 1.0 as previously described (12). Aliquots were removed at different time points, and the total protein was isolated with TRIzol (Gibco BRL), separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 4 to 20% minigel (Bio-Rad), and analyzed by Western blotting. The blots were incubated at 4°C overnight with purified rabbit antiagnoprotein antibodies (A81038P) in phosphate-buffered saline with 3% bovine serum albumin (Sigma). These antibodies were raised against the expression product of a cloned BKV agnogene as described previously (17) and purified by affinity chromatography. Incubation with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated swine anti-rabbit immunoglobins (DAKO A/S, Glostrup, Denmark), diluted 1:500 in phosphate-buffered saline with 3% bovine serum albumin, took place for 2 h at room temperature. Color was developed by using nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate toluidinium (NBT/BCIP; DAKO A/S).

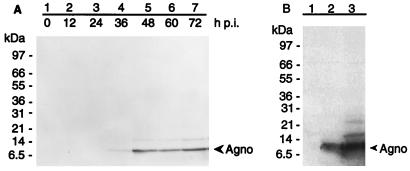

A band corresponding to a protein of approximately 8 kDa was detected (Fig. 1A, lanes 2 to 7). This compares well with the calculated molecular mass of the putative BKV agnoprotein (7.5 kDa). The band was not seen in blots of mock-infected cells (Fig. 1A, lane 1) or when unrelated antibodies were used (data not shown). A faint second band, corresponding to a protein with a molecular mass of 15 kDa, was also seen. This may represent a posttranslationally modified form of the protein. The agnoprotein bands first appeared 36 h postinfection (p.i.); this must be considered as being late in infection.

FIG. 1.

Western blot analysis of BKV agnoprotein (Agno) synthesis in HUV-EC-C. (A) Time course of agnoprotein synthesis, detected by using purified agnoprotein antibodies. (B) Extracts from cells transfected with an agnoprotein expression plasmid (lane 2), compared with mock-transfected (lane 1) and 48-h-p.i. BKV-infected (lane 3) cells. The positions of molecular mass markers are indicated.

To confirm the identity of the protein(s) that was detected with the antiagnoprotein antibodies, we transiently transfected (using Lipofectin reagent [Gibco BRL]) a cloned agnogene expression construct into HUV-EC-C cells. The construct consisted of the BKV agnogene ORF cloned into the pRC/CMV vector (Invitrogen). Radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer cell extracts were then analyzed by Western blotting with rabbit antiagnoprotein antiserum as described above, except that signals were enhanced by using a chemiluminescent substrate (CDP-Star; New England Biolabs). As demonstrated in Fig. 1B, the band detected in agnogene-transfected cells was identical to the lowest (8-kDa) band seen in BKV-infected cells, confirming its identity as the agnoprotein. In addition to the bands seen in Fig. 1A, a third band was observed in the BKV-infected cell extract (Fig. 1B, lane 3). This probably represents another posttranslationally modified form of the agnoprotein, detected because of the more sensitive substrate used. A single agnoprotein band, corresponding to the expected size, was seen in extracts from agnogene-transfected cells.

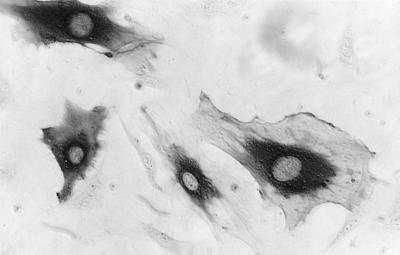

The subcellular localization of the BKV agnoprotein was investigated by immunoperoxidase staining with purified antiagnoprotein antibodies as previously described (12). Staining was strictly cytoplasmic in BKV-infected HUV-EC-C cells (Fig. 2), being most intense in the perinuclear area, and was first detected between 24 and 36 h p.i. This is about the same time or somewhat after VP1 was detected (30a). In SV40-infected cells, the agnoprotein seemed to be expressed after the structural proteins (14, 21, 22, 26).

FIG. 2.

Subcellular localization of the BKV agnoprotein (Agno). Shown are immunoperoxidase-stained BKV-infected HUV-EC-C cells at 72 h p.i. Purified antiagnoprotein antibodies were used.

BKV agnoproteins with identical molecular masses and subcellular localizations were present in all productively BKV-infected cell lines examined (30b), including Vero cells (ATCC CCL 81), CV-1 cells (ATCC CCL70), HEK cells (Whittaker M.A. Bioproducts, Inc., Walkersville, Md.; no. 70-151), and persistently BKV-infected human osteoblastoma cells established from the U2-OS cell line (ATCC HTB-96). No nuclear staining was detected in any of these cell types, contradicting reports that a small fraction of SV40 agnoprotein molecules are localized to the nucleus (26).

Immunoperoxidase staining of HUV-EC-C cells that had been transiently transfected with the BKV agnoprotein expression plasmid demonstrated that agnoprotein localization was identical to that in virus-infected cells (data not shown), supporting the conclusion that the subcellular localization of agnoprotein is independent of other viral proteins.

The BKV agnoprotein is phosphorylated in vivo.

An unconfirmed report has suggested that phosphorylation of the SV40 agnoprotein occurs in vivo (21). There are several potential phosphorylation sites in the BKV agnoprotein sequence, including two consensus protein kinase C phosphorylation sites (28) that are conserved among all three primate polyomavirus agnoprotein sequences, one protein kinase C phosphorylation site unique to BKV, and one casein kinase II phosphorylation site.

BKV-infected HUV-EC-C cell phosphorylated proteins were metabolically labelled by replacing the growth medium with 1 ml of 32P labelling medium per 9.5-cm2 well at 46 h p.i. Mock-infected cells were used as a control. The 32P-labelling medium consisted of 100 μCi of inorganic 32P (PBS-11; Amersham Corp.) per ml in phosphate-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (D3656; Sigma) with 10% FBS. Sodium bicarbonate and sodium phosphate were added at the concentrations recommended by the manufacturer. HUV-EC-C cells grow normally in this phosphate-deprived medium for at least a week if ECGS is added. After 2 h of labelling, cell lysates were made and agnoprotein was immunoprecipitated with purified antiagnoprotein antibodies bound to protein A beads from a Hi-Trap protein A column (Pharmacia). This was followed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting as outlined above. Phosphorylated proteins were detected by using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

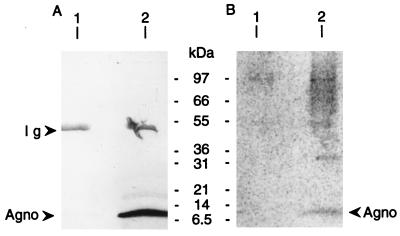

Western blotting of immunoprecipitates from mock-infected cells (Fig. 3A, lane 1) showed a single band at about 50 kDa. This was due to the binding of secondary (anti-rabbit immunoglobulin) antibodies to antiagnoprotein antibodies which were stripped off the beads used for immunoprecipitation along with the agnoprotein. The same band was seen in BKV-infected cell lysates (Fig. 3A, lane 2), along with a band at approximately 8 kDa corresponding to the agnoprotein.

FIG. 3.

In vivo phosphorylation of BKV agnoprotein. (A) Immunoblot of cell lysates from mock-infected (lane 1) and BKV-infected (lane 2) HUV-EC-C cells after metabolic labelling with 32P. The lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with purified antiagnoprotein antibodies prior to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. The elution positions of the immunoglobin heavy chain (Ig) and agnoprotein (Agno) are indicated by arrows. (B) PhosphorImager analysis of the blot in panel A, showing phosphorylated immunoprecipitated proteins. The positions of molecular mass markers are indicated.

Immunoprecipitates from BKV-infected cells, but not control cells, showed a faint radioactive band corresponding to a protein of approximately 8 kDa (Fig. 3B, lane 2). The faintness of the band was probably due to unlabelled phosphate in the FBS present in the labelling medium. The band of radioactivity could be superimposed on the one obtained by Western blotting with purified antiagnoprotein antibodies, strongly indicating that it represents phosphorylated BKV agnoprotein. This band was absent in lysates of mock-infected cells (Fig. 3B, lane 1), and it was also not evident when immunoprecipitation was performed with unrelated rabbit antibodies (G31028P) (results not shown).

32P-labelled proteins of higher molecular mass were coimmunoprecipitated with the agnoprotein (Fig. 3B, lane 2). The molecular mass distribution of the coimmunoprecipitated phosphoproteins was consistent among the cell lysates. They were not seen in immunoprecipitates from mock-infected cells or in unrelated-antibody immunoprecipitates from BKV-infected cells. The phosphorylated cellular or viral proteins may have associated with the agnoprotein in vivo, although we cannot formally eliminate the possibility that association occurred during immunoprecipitation or that proteins phosphorylated during BKV infection bound nonspecifically to the antiagnoprotein antibodies.

A subset of cellular proteins coimmunoprecipitate with the BKV agnoprotein.

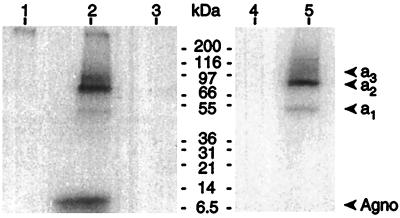

Genetic evidence of interactions between the SV40 agnoprotein and the viral VP1 protein has been reported (3, 23). This, and the results described in the previous paragraph, prompted us to investigate whether the coimmunoprecipitated proteins were of cellular or viral origin. BKV- or mock-infected HUV-EC-C cells were washed with leucine-free DMEM (Sigma no. D4655) (with l-lysine–HCl, l-methionine, l-glutamine, and sodium bicarbonate added at the concentrations recommended by the manufacturer) at 24 h p.i. Further incubation was carried out for 24 h in [3H]leucine labelling medium (50 μCi of [3H]leucine [NET-135H; Amersham Corp.] per ml in leucine-free DMEM containing 10% FBS and supplemented with 30 μg of ECGS per ml (1 ml/9.5 cm2 well]). Cell lysates were then subjected to immunoprecipitation with purified antiagnoprotein antibodies or unrelated antibodies. The immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE. The gels were stained with Coomassie blue R250 (31) and subjected to fluorography (Amplify; Amersham).

Several radioactive bands were seen after immunoprecipitation of BKV-infected cell lysates with purified antiagnoprotein antibodies (Fig. 4, lane 2). The lowest band could be readily identified as the BKV agnoprotein from its apparent molecular mass (8 kDa). The other bands represented much larger proteins, with apparent molecular masses of approximately 50, 75, and 100 kDa. Appropriate controls demonstrated that these results were specific for BKV-infected cells and antiagnoprotein antibodies (Fig. 4, lanes 1 and 3). No labelled proteins were immunoprecipitated from radiolabelled, mock-infected cell lysate (Fig. 4, lane 4), but when lysate from these cells was mixed with lysate from unlabelled 48-h-p.i. cells, the pattern of bands was identical to that seen for labelled BKV-infected cells, except for the absence of the agnoprotein band (Fig. 4, lane 5). These results show that the coimmunoprecipitated proteins are of cellular, not viral, origin. The possibility that the protein interactions took place during extraction cannot be formally eliminated, but since the agnoprotein appears to be distributed throughout the cytoplasm, the interacting proteins must be well hidden to prevent in vivo encounters.

FIG. 4.

Coimmunoprecipitation of higher-molecular-weight proteins of cellular origin with BKV agnoprotein. BKV- or mock-infected HUV-EC-C cells were metabolically labelled with [3H]leucine, and then cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with purified antiagnoprotein antibodies or unrelated antibodies and subjected to SDS-PAGE and fluorography. Lanes: 1, lysates from mock-infected cells immunoprecipitated with antiagnoprotein antibodies; 2, lysates from BKV-infected cells immunoprecipitated with antiagnoprotein antibodies; 3, lysates from BKV-infected cells immunoprecipitated with unrelated antibodies; 4, lysates from radiolabelled, mock-infected HUV-EC-C cells; 5, lysates from mock-infected [3H]labelled HUV-EC-C cells that were incubated with lysates from unlabelled, BKV-infected HUV-EC-C cells prior to immunoprecipitation. The positions of molecular mass markers are indicated.

Discussion.

We have demonstrated the expression of a BKV agnogene product in virus-infected cells. The expression pattern, including subcellular localization and time of appearance, is similar to that of the SV40 agnoprotein (21, 22, 26).

The SV40 agnoprotein is apparently translated from the same mRNA as that encoding the major virion protein VP1 (3, 24, 30). There is no reason to assume that the situation for BKV is different, since the mRNA species of the two viruses are very similar (19). One might expect the agnoprotein to be expressed at the same time, or even before, VP1, since the agnogene is 5′ of the VP1 ORF. However, in SV40-infected cells, the agnoprotein appears several hours after VP1 (22, 26). At present we are investigating the situation in BKV-infected cells. If the agnoprotein is expressed later than VP1, the discrepancy between the time of appearance of the agnoprotein and its position on the mRNA implies that there exists a special control mechanism, which suggests that the agnoprotein plays an important role in the primate polyomavirus life cycle in vivo.

It has previously been stated that the SV40 agnoprotein is phosphorylated (21), although to our knowledge the evidence for this has not been published. We have now shown that the BKV agnoprotein is phosphorylated. Phosphorylation appears to be a common mechanism for regulation of biologically active proteins (10, 11), so it may be interesting to examine whether the phosphorylation state of the BKV agnoprotein affects its binding to cellular proteins, for example.

A number of putative roles for the SV40 agnoprotein (and, by implication, the BKV agnoprotein) have been suggested. We are, however, of the opinion that most of these roles fail to comprise the subcellular location of the protein and its late appearance. For example, roles in the control of VP1 transcription (1, 14, 15) or virus assembly (4, 23–25) would seem to require nuclear localization. Our own results and those of others (5, 24, 26) clearly show the dominant fraction of the protein to be cytoplasmic, which suggests that neither of these functions represents the main purpose of the agnoprotein. A role for the SV40 agnoprotein in nuclear localization of VP1, either directly (4, 30) or by prevention of aggregation into virus-like particles (3), has also been suggested. However, VP1 from primate polyomaviruses contains an efficient nuclear localization signal which has proven functional in SV40 in the absence of agnoprotein (20, 35). Nomura et al. (26) also clearly found SV40 VP1 in the nucleus 24 h after infection, before agnoprotein was detected.

Nonenveloped viruses were thought to leave host cells by cytolysis (13). However, the exodus of SV40 can take place without cell lysis, perhaps via a vesicular transport process (6, 27). Since SV40 virions (and, by inference, BK virions) are strongly karyophilic (7), the role of the agnoprotein may be the promotion of virion release from the cell. This hypothesis, proposed by Resnick and Shenk (30), accounts for all published data, including the very late appearance of the agnoprotein in the virus life cycle.

The use of genetic techniques to investigate the role of the agnoprotein in the primate polyomavirus life cycle is complicated by the fact that this protein is nonessential during infection of cell cultures and that it is produced from an ORF situated 5′ in the mRNA of an essential protein. The subtle effects produced by mutations in the agnoprotein ORF, and the danger of inducing unintended effects on VP1 by altering its upstream mRNA sequences, have probably contributed to the multiplicity of roles attributed to the agnoprotein. Direct investigation of proteins such as those we have detected, which interact with agnoprotein in vivo, may provide more reliable clues as to the role of this protein in primate polyomavirus infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from The Research Council of Norway, the Norwegian Cancer Society, and the Olav and Erna Aakres Foundation for Fighting Cancer.

We thank Ole Morten Seternes for the BKV agnoprotein expression plasmid and Inger Danielsen for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alwine J C. Evidence for simian virus 40 late transcriptional control: mixed infections of wild-type simian virus 40 and a late leader deletion mutant exhibit trans effects on late viral RNA synthesis. J Virol. 1982;42:798–803. doi: 10.1128/jvi.42.3.798-803.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barkan A, Mertz J E. DNA sequence analysis of simian virus 40 mutants with deletions mapping in the leader region of the late viral mRNA’s: mutants with deletions similar in size and position exhibit varied phenotypes. J Virol. 1981;37:730–737. doi: 10.1128/jvi.37.2.730-737.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barkan A, Welch R C, Mertz J E. Missense mutations in the VP1 gene of simian virus 40 that compensate for defects caused by deletions in the viral agnogene. J Virol. 1987;61:3190–3198. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3190-3198.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carswell S, Alwine J C. Simian virus 40 agnoprotein facilitates perinuclear-nuclear localization of VP1, the major capsid protein. J Virol. 1986;60:1055–1061. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.3.1055-1061.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carswell S, Resnick J, Alwine J C. Construction and characterization of CV-1P cell lines which constitutively express the simian virus 40 agnoprotein: alteration of plaquing phenotype of viral agnogene mutants. J Virol. 1986;60:415–422. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.2.415-422.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clayson E T, Jones Brando L V, Compans R W. Release of simian virus 40 virions from epithelial cells is polarized and occurs without cell lysis. J Virol. 1989;63:2278–2288. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2278-2288.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clever J, Yamada M, Kasamatsu H. Import of simian virus 40 virions through nuclear pore complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7333–7337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole C N. Polyomavirinae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1997–2025. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhar R, Subramanian K N, Pan J, Weissman S M. Structure of a large segment of the genome of simian virus 40 that does not encode known proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:827–831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.3.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dynlacht B D. Regulation of transcription by proteins that control the cell cycle. Nature. 1997;389:149–152. doi: 10.1038/38225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer E H. Cellular regulation by protein phosphorylation: a historical overview. Biofactors. 1997;6:367–374. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520060307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flaegstad T, Traavik T. BK virus in cell culture: infectivity quantitation and sequential expression of antigens detected by immunoperoxidase staining. J Virol Methods. 1987;16:139–146. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(87)90038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gwaltney J M., Jr Rhinoviruses. Yale J Biol Med. 1975;48:17–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hay N, Aloni Y. Attenuation of late simian virus 40 mRNA synthesis is enhanced by the agnoprotein and is temporally regulated in isolated nuclear systems. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:1327–1334. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.6.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hay N, Kessler M, Aloni Y. SV40 deletion mutant (d1861) with agnoprotein shortened by four amino acids. Virology. 1984;137:160–170. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hay N, Skolnik David H, Aloni Y. Attenuation in the control of SV40 gene expression. Cell. 1982;29:183–193. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hey A W, Johnsen J I, Johansen B, Traavik T. A two fusion partner system for raising antibodies against small immunogens expressed in bacteria. J Immunol Methods. 1994;173:149–156. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou-Jong M-H J, Larsen S H, Roman A. Role of the agnoprotein in regulation of simian virus 40 replication and maturation pathways. J Virol. 1987;61:937–939. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.3.937-939.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howley P M. Molecular biology of SV40 and the human polyomaviruses BK and JC. In: Klein G, editor. Viral oncology. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1980. pp. 489–537. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishii N, Minami N, Chen E Y, Medina A L, Chico M M, Kasamatsu H. Analysis of a nuclear localization signal of simian virus 40 major capsid protein Vp1. J Virol. 1996;70:1317–1322. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1317-1322.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson V, Chalkley R. Use of whole-cell fixation to visualize replicating and maturing simian virus 40: identification of new viral gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6081–6085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jay G, Nomura S, Anderson C W, Khoury G. Identification of the SV40 agnogene product: a DNA binding protein. Nature. 1981;291:346–349. doi: 10.1038/291346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margolskee R F, Nathans D. Suppression of a VP1 mutant of simian virus 40 by missense mutations in serine codons of the viral agnogene. J Virol. 1983;48:405–409. doi: 10.1128/jvi.48.2.405-409.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mertz J E, Murphy A, Barkan A. Mutants deleted in the agnogene of simian virus 40 define a new complementation group. J Virol. 1983;45:36–46. doi: 10.1128/jvi.45.1.36-46.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng S C, Mertz J E, Sanden Will S, Bina M. Simian virus 40 maturation in cells harboring mutants deleted in the agnogene. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:1127–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nomura S, Khoury G, Jay G. Subcellular localization of the simian virus 40 agnoprotein. J Virol. 1983;45:428–433. doi: 10.1128/jvi.45.1.428-433.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norkin L C, Ouellette J. Cell killing by simian virus 40: variation in the pattern of lysosomal enzyme release, cellular enzyme release, and cell death during productive infection of normal and simian virus 40-transformed simian cell lines. J Virol. 1976;18:48–57. doi: 10.1128/jvi.18.1.48-57.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearson R B, Kemp B E. Protein kinase phosphorylation site sequences and consensus specificity motifs: tabulations. Methods Enzymol. 1991;200:62–81. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)00127-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piatak M, Subramanian K N, Roy P, Weissman S M. Late messenger RNA production by viable simian virus 40 mutants with deletions in the leader region. J Mol Biol. 1981;153:589–618. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90409-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Resnick J, Shenk T. Simian virus 40 agnoprotein facilitates normal nuclear location of the major capsid polypeptide and cell-to-cell spread of virus. J Virol. 1986;60:1098–1106. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.3.1098-1106.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30a.Rinaldo, C. H., and A. Hey. Unpublished observations.

- 30b.Rinaldo, C. H., and T. Traavik. Unpublished data.

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seif I, Khoury G, Dhar R. The genome of human papovavirus BKV. Cell. 1979;18:963–977. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shenk T E, Carbon J, Berg P. Construction and analysis of viable deletion mutants of simian virus 40. J Virol. 1976;18:664–671. doi: 10.1128/jvi.18.2.664-671.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sundsfjord A, Johansen T, Flaegstad T, Moens U, Villand P, Subramani S, Traavik T. At least two types of control regions can be found among naturally occurring BK virus strains. J Virol. 1990;64:3864–3871. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.8.3864-3871.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wychowski C, Benichou D, Girard M. A domain of SV40 capsid polypeptide VP1 that specifies migration into the cell nucleus. EMBO J. 1986;5:2569–2576. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang R C, Wu R. BK virus DNA: complete nucleotide sequence of a human tumor virus. Science. 1979;206:456–462. doi: 10.1126/science.228391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]