Abstract

Background: Trans people are incarcerated at disproportionately high rates relative to cisgender people and are at increased risk of negative experiences while incarcerated, including poor mental health, violence, sexual abuse, dismissal of self-identity, including poor access to healthcare. Aims: This scoping review sought to identify what is known about the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of correctional staff toward incarcerated trans people within the adult and juvenile justice systems. Method: This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the five-stage iterative process developed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), utilizing the PRISMA guidelines and checklist for scoping reviews and included an appraisal of included papers. A range of databases and grey literature was included. Literature was assessed against predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria, with included studies written in English, online full text availability, and reported data relevant to the research question. Results: Seven studies were included with four using qualitative methodologies, one quantitative, and two studies employing a mixed methods approach. These studies provided insights into the systemic lack of knowledge and experience of correctional staff working with trans people, including staff reporting trans issues are not a carceral concern, and carceral settings not offering trans-affirming training to their staff. Within a reform-based approach these findings could be interpreted as passive ignorance and oversights stressing the importance of organizational policies and leadership needing to set standards for promoting the health and wellbeing of incarcerated trans persons. Conclusions: From a transformational lens, findings from this study highlight the urgent need to address the underlying structural, systemic, and organizational factors that impact upon the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors staff have and hold in correctional, and other health and community settings to meaningfully and sustainably improve health, wellbeing, and gender-affirming treatment and care for trans communities, including make possible alternative methods of accountability for those who do harms.

Keywords: Attitudes, behaviors, correctional staff, incarceration, juvenile justice system, knowledge, trans/transgender

Introduction

An estimated 16% of adult trans persons in the United States (US) have been incarcerated at some point in their lives (Grant et al., 2011) and 1.6% of the United Kingdom (UK) general adult incarcerated population reported identifying as trans (Hymas, 2019). Due to systemic and structural discrimination and targeting within the criminal legal system, trans people are incarcerated at a disproportionate rate to the general population (Brömdal et al., 2019; Buist & Stone, 2014; Clark et al., 2017; Hughto et al., 2022; Mitchell et al., 2022), and are under-represented (in research and prison data) due to ongoing stigmatization and persecution (Brömdal et al., 2019; Brömdal et al., 2023; Nulty et al., 2019; Penal Reform, 2022; Van Hout & Crowley, 2021; Wilson et al., 2017). In addition to the incarcerated adult population (Clark et al., 2023), trans youth are also incarcerated at a disproportionate rate, especially youth of color and First Nations persons, and report prejudicial treatment compared to non-trans incarcerated people (Mallon & Perez, 2020; Mountz, 2020). The systemic societal and institutional violence and discrimination toward trans people (Clark et al., 2023; Hughto et al., 2022; Reisner et al., 2014; Stanley & Smith, 2015; White Hughto et al., 2015), in great part rooted in trans persons’ restricted access to material and financial resources, including education, employment, and housing, in turn translate to some trans persons turning to street economies and sex work for economic survival (Garofalo et al., 2006; Hughto et al., 2022; White Hughto et al., 2018). These experiences, coupled with biased policing practices (Grant et al., 2011; Miles-Johnson, 2015; Mitchell et al., 2022; Poteat et al., 2023) then place trans persons at much higher risk of arrest and incarceration than their cisgender counterparts (Buist & Stone, 2014; Hughto et al., 2022; LaChance & Dwyer, 2023; Lamble, 2014; Miles-Johnson, 2015; Mitchell et al., 2022; Poteat et al., 2023; Reisner et al., 2014; Sevelius & Jenness, 2017)

From a health perspective, trans persons are classified as a ‘vulnerable group’ (Brömdal et al., 2023; Brown, 2014; Du Plessis et al., 2023; Winter, 2023) due to the discrimination, marginalization, and the extensive violence they experience, and thus often arrive at detention or incarceration facilities after shouldering considerable pressures on their mental health (Clark et al., 2017; Creasy et al., 2023; Dalzell et al., 2023; Hughto et al., 2022). Exacerbated by mistreatment from not only other incarcerated persons but those in authority, some trans people experience mental health issues such as depression, suicide ideation and self-harm or self-mutilation (Brooke et al., 2022; Brown & McDuffie, 2009; Halliwell et al., 2022; Hughto et al., 2022; Jaffer et al., 2016; Jenness, 2021; Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014; Ledesma & Ford, 2020; Nulty et al., 2019; Phillips et al., 2020; Van Hout et al., 2020; Watson et al., 2023; Wilson et al., 2017).

When considering the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors correctional staff have toward incarcerated trans persons, it is important to highlight that although correctional staff work within a system that is primarily charged with maintaining safety and security of their facilities, these systems are “grounded in a dominantly cisgender prison culture”—a culture in which it is assumed that all incarcerated persons’ gender, expression, and anatomy align with their sex assigned at birth (Adorjan et al., 2021, p. 1372). This cisgendered prison culture, in turn creates a series of problems and issues that correctional staff and the system are pressed to address (Ricciardelli et al., 2020). In seeking to find solutions to these ‘problems’ some correctional staff and their systems employ reformist strategies that are, to some extent, needs- and safety-based, and in part have been derived from trans persons’ preference within a cisnormative carceral framework (California Department of Corrections & Rehabilitation, 2023). From a housing perspective, these may include trans-specific sections within carceral systems for trans persons, single-cell occupation, segregation or solitary confinement to either ‘protect’ incarcerated trans persons from harm, or for the supposed protection of others—arising and conforming with the cisnormative prison logic and culture (Allspach, 2010; Lamble, 2015; Oparah, 2015). Rather than eliciting safety for incarcerated trans persons, these housing policies, especially segregation and solitary confinement, enact further harm and violence by subjecting trans persons being cut off from “recreational, educational, and occupational opportunities, and associational rights” (Peek, 2004, p. 1220). To note, the reformist strategies remain rooted in the vision of strengthening the power, legitimacy, and persistence of the prison system through continued surveillance, punishment, and control (Lamble, 2015).

In an attempt to maintain carceral control, correctional authorities are known to disregard trans persons’ gender identity when disclosed and/or deny them access to medically necessary, gender-affirming hormone therapy resulting in additional and inhumane punishment (Brömdal et al., 2019; Brömdal et al., 2023; Clark et al., 2017; Phillips et al., 2020; Sanders et al., 2023; Tadros et al., 2020). Parallel to this, studies suggest that the knowledge and behaviors of correctional staff are a product of and contribute to a reformist context characterized by structural discrimination and over-representation of trans people in the criminal legal system. Where Brömdal et al. (2019) and Clark et al. (2017) highlight a gross lack of understanding and disregard by correctional staff regarding the distinctions between gender identity and expression and sexual orientation, we suggest that the carceral system maintains the status quo by reproducing and reinforcing broader socio-cultural heteronormative and cisnormative logics and practices. Further, authorities perceive incarcerated trans persons’ requests for gender-affirming care as manipulative (Brown & McDuffie, 2009; Clark et al., 2017) which correlates with cisnormative discourse suggesting that trans people are “fakers”, “non-feminine, bizarre, creepy” individuals (Reinl, 2022) inciting fear of deviation and disruption of the carceral system; and/or are fragile, victims and at risk (Ashley, 2018; Serano, 2016).

In stark contrast to the reformist framework, a transformative approach seeks to curtail the power of the prison system (Lamble, 2015; Spade, 2015) by critically examining the reasons, methods, and motives behind the disproportionate incarceration of trans persons, especially trans women (Clark et al., 2023; Hughto et al., 2022; Oparah, 2015; Reisner et al., 2014). A transformative approach does so by addressing the causes rooted in systemic societal and institutional violence and discrimination toward trans people (Clark et al., 2023; Hughto et al., 2022; Reisner et al., 2014; Spade, 2015; Stanley & Smith, 2015; Walker et al., 2022; White Hughto et al., 2015), including biased policing practices (Grant et al., 2011; Mitchell et al., 2022; Poteat et al., 2023) placing trans women at much higher risk of arrest and incarceration than their cisgender counterparts (Buist & Stone, 2014; Hughto et al., 2022; Mitchell et al., 2022; Poteat et al., 2023; Reisner et al., 2014; Sevelius & Jenness, 2017). As such, the transformative model aims to dismantle the current carceral structure and system, in a broader attempt at decarceration, and to disrupt the dominant and neo-liberal cisnormative prison logic and culture that cause harm, while also addressing contributing factors placing trans women at higher risk of arrest and incarceration (Ball, 2021; Clark et al., 2023; Lamble, 2014; Oparah, 2015; Spade, 2015; Stanley & Smith, 2015; Stanley et al., 2012; Walker et al., 2022).

As trans rights and health scholars, including with lived trans incarceration experiences, focused on contributing to a credible evidence-base toward alleviating injustices and health inequities experienced by trans people facing systemic and structural violence, we seek to better understand the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors correctional staff have regarding trans persons in carceral settings and consider how transformative approaches to incarceration may inform this discourse differently. To this end, this scoping review is framed by the following research question: What is known about the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of correctional staff toward incarcerated trans people within the adult and juvenile justice systems?

Methods

This scoping review adhered to the five-stage iterative process developed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), which included the following steps: 1) identify the research question/s; 2) identify relevant studies; 3) select relevant studies; 4) chart the data; and 5) collate, summarize and present the results.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria followed the Joanna Briggs Institute’s guidelines (2020) that include participants, concept, and context, and further explored below.

Participants

Participants within the studies were limited to correctional staff, including COs (who provide supervision and regulation of the prison functions), correctional managers, and contractual staff, including educators and allied health practitioners (e.g. nurses, counselors, psychologists). The incarceration setting referred to adult and juvenile prisons, jails and other settings as outlined in the concept section below. Participants needed to currently, previously or be intending to work directly with incarcerated trans people (trans people were defined as people whose gender is different from the socially prescribed gender associated with one’s assigned birth sex).

Concept

The concept was restricted to the correctional setting, defined as any setting housing individuals who become incarcerated following arrest, before sentencing, and while serving sentences, as well as immigration detention centers, watchhouses, prisons, jails, and half-way houses (e.g. community corrections facility) for adults and adolescents (defined as between ages 10 to 19; World Health Organization, 2022).

Context

This review examined existing literature regarding reported knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors toward incarcerated trans persons in the above settings. All literature was to be available in English. Grey literature was included if available on the internet regardless of possible restrictions (such as copyright). No geographical or date limitations were enforced.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed for this scoping review, utilizing preliminary searches to trial, and adapting the search terms to maximize relevant results (see Table 1). The following electronic databases were used: EBSCOHost Megafile Ultimate, Academic Search Ultimate, APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, Biological Abstracts, CINAHL with full text, eBook Collection, Education research complete, eJournals, ERIC, Psychology and Behavioral sciences collection, Sociology Source Ultimate, SCOPUS, Trove (theses), Google Advance (grey literature such as reports). The literature searches were conducted in April 2023 and did not utilize any date nor geographical restrictions, grey literature was included (theses, book chapters, scholarly material), however conference abstracts were not included due to the scope of this review. Language was restricted to English.

Table 1.

Search strategy.

| Search | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| #1 (truncated) | Prison* OR detention* OR incarcerat* OR custod* OR jail OR goal OR “correction* facility*” OR “correction setting*” OR “correction* service*” OR “detain* setting*” OR probation OR confinement OR penitentiar* OR penal OR imprison* OR lockup OR detention OR “Juvenile justice system” OR juvenile prison OR youth juvenile OR youth justice |

| “correctional officer” OR “correct* officer” OR “correct* manager” OR staff OR worker OR workers OR “prison educat*” check OR immigration detention | |

| Transgender OR transmen OR transman OR transmale OR “trans man” OR “trans men” OR “trans male” OR transmasc OR transmasculine OR transfem OR transfeminine OR transwoman OR transwoman OR transfemale OR “trans woman” OR “trans women” OR “trans female” OR LGBT* OR trans OR “gender identity” OR “gender identities” OR “trans identity” OR “trans identities” OR “Female to Male” OR “Male to Female” OR transsexual? OR transexual? OR trans* OR FTM OR MTF OR “gender reassignment” OR “sex reassignment” OR “gender minority” OR “sex change” OR “gender change” OR “gender dysphoria” OR transsexualism OR “gender identity disorder” | |

| knowledge OR attitude* OR behavior* OR behavior* OR perception OR view* OR management OR practice* | |

| #2 (non-truncated) | Prison OR prisoner OR detention OR detained OR incarcerated OR incarceration OR custody OR jail OR goal OR “correction facility” OR “correctional facility” OR “correction facilities” OR “correctional facilities” OR “correction setting” OR “correction settings” OR “correction service” OR “correctional services” OR “detain setting” OR probation OR confinement OR penitentiary OR penitentiaries OR penal OR imprison OR imprisonment OR lockup OR detention OR “Juvenile justice system” OR juvenile prison OR youth juvenile OR youth justice |

| “correctional officer” OR “corrections officer” OR “correctional officers” OR “corrections manager” OR “correctional manager” OR staff OR worker OR workers OR “prison educators” OR check OR immigration detention | |

| Transgender OR transmen OR transman OR transmale OR “trans man” OR “trans men” OR “trans male” OR transmasc OR transmasculine OR transfem OR transfeminine OR transwoman OR transwoman OR transfemale OR “trans woman” OR “trans women” OR “trans female” OR LGBT OR LGBTI OR LGBTIQ OR LGBTIQA OR LGB OR trans OR “gender identity” OR “gender identities” OR “trans identity” OR “trans identities” OR “Female to Male” OR “Male to Female” OR transsexual? OR transexual? OR FTM OR MTF OR “gender reassignment” OR “sex reassignment” OR “gender minority” OR “sex change” OR “gender change” OR “gender dysphoria” OR transsexualism OR “gender identity disorder” | |

| Knowledge OR knowledges OR attitude OR attitudes OR behavior OR behaviors OR behavior OR behaviors OR perception OR view OR views OR management OR practice OR practices |

Screening procedure

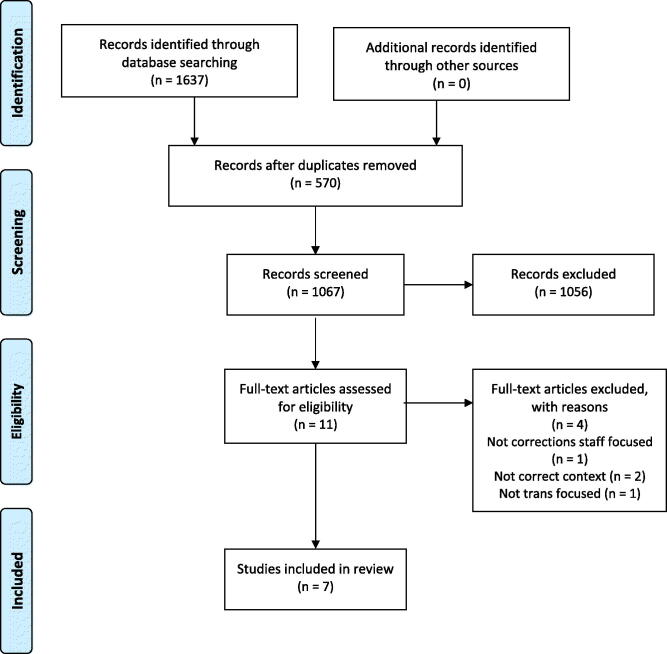

Two members of the authorship team (KD and TE) completed the searches together at the same time but on different computers, with the same number being obtained in both. The first stage of eligibility screening involved these two team members independently reviewing resultant literature titles, abstracts, and full text documents against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion decisions were discussed, with outcomes agreed upon together. Any disagreements regarding inclusion were resolved through the involvement of a third research team member (AB; Figure 1). Forward and backward searches were conducted, no additional records were included.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of review search for research question.

Quality appraisal

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) appraisal method was utilized, using the online JBI appraisal tools (JBI, 2020). This approach is consistent with the methodology of a scoping review, while also allowing for all relevant literature (including grey literature) to be included in the comprehensive review (Peters et al., 2015).

Data extraction and analysis

With the involvement of the researchers’ science librarian, the data extraction was completed by two researchers (KD and TE), with analysis completed by KD and reviewed for clarification and verification by TE (as per Table 2). This process was reviewed by the wider research team for clarification and verification. The initial data extraction criteria included author, year of publication, country of research study, aim(s)/objectives, methods, and findings.

Table 2.

Characteristics of reviewed studies (n = 7).

| Author and Year | Location of Research Study | Aim(s)/Objectives | Study Population | Methods | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adorjan et al., (2021) | Canada Adult setting |

What are correctional officer recruits’ views about working with trans colleagues and around the new trans prisoner placement policy allowing prisoners to choose which gendered prison they are placed in. | Correctional officer recruits (n = 66) | Qualitative research paradigm: data collected using semi-structured interviews; analyzed using semi-grounded approach to qualitative coding. | Identified knowledge from cisgender COs, regarding policy changes and views. Reported overwhelming support for trans colleagues, however, is contingent upon safety and security within a cisgender prison culture situated within a wider unsettled prison culture. |

| Byrd (2020) [doctoral dissertation] | US Adult setting |

What is the level of knowledge prison staff have about their responsibilities regarding equal treatment and protection of trans incarcerated persons, and how does this influence prison staff perceptions around the various types of maltreatment trans incarcerated persons experience? | Prison Officials (n = 7) | Qualitative action research. Data collected using focus groups/policy and procedure documents; analyzed using coding procedures. | Findings suggest that personal biases of correctional staff and lack of accountability from management/ supervisors were causes for maltreatment of trans officers in prisons. |

| Clark et al. (2017) | US Adult setting |

What is the knowledge of, attitudes toward, and experiences of correctional health care providers’ around providing care to trans incarcerated people? | Correctional Healthcare Proiders (n = 20) |

Qualitative research. Data collected using semi-structured in-depth interviews; analyzed using modified grounded theory framework and thematic analysis. | Findings revealed incarcerated trans people do not receive consistent adequate or gender-affirming care during incarceration due to factors including lack of training, restrictive healthcare policies, unsupportive prison culture and lack of trans cultural and clinical competence. |

| White Hughto et al. (2017) | US Adult setting |

By adapting, delivering and evaluating a trans cultural and clinical intervention, can the knowledge, attitudes, skills, self-efficacy and subjective norms held by correctional healthcare providers be increased to improve the gender-affirming care provided for trans patients? | Correctional healthcare providers. Baseline and immediate follow-up n = 34; 3-month follow-up n = 28. Interviewed after 3-month follow-up n = 12. |

Mixed methods approach at a single session, group-based intervention. Quantitative data collected using longitudinal repeated measure design over three time points (baseline survey/post-training survey/ 3-month follow-up). Qualitative data collected after the third time point, n = 12 semi-structured interviews. Quantitative data analyzed using descriptive statistics; qualitative data analyzed using thematic analysis. |

Findings showed that the intervention resulted in an immediate increase post-intervention of providers willingness to provide gender-affirming care, as well as increases over time in trans cultural competence, medical gender affirmation knowledge, self-efficacy to start hormones for trans women and subjective norms related to trans care. |

| Marlow et al. (2015) | UK Adult setting |

In relation to correctional staff and trans incarcerated persons are there any identifiable equity and diversity issues surrounding the interactions between them, and what is the knowledge and information available to staff regarding trans* incarcerated persons? | Correctional Staff (n = 6) | Qualitative research. Data collected using semi-structured interviews; analyzed using thematic analysis. | Findings indicate that correctional staff collaborate with incarcerated trans people but recommends additional guidance with identifying boundaries, as well as staff benefiting from more education on the impact of trans identity on criminogenic needs. |

| Matarese et al. (2023) | US Youth setting |

To understand the impact the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of juvenile justice workers on behaviors toward diverse incarcerated youth. | Correctional staff (n = 237) | Quantitative analysis including independent samples t-tests. | Positive correlation between knowledge level and self-reported demonstrated protective and supportive behavior toward incarcerated youth. |

| Walker (2020) [doctoral dissertation] | US Youth setting |

Would religious beliefs, lack of LGBTQI training, and inadequate policies and procedure hinder correctional staff members’ interactions with trans juvenile incarcerated persons? | Correctional Staff Pretest-sensitivity training-post-test n = 80; Focus group n = 20 |

Mixed methods quasi-experimental approach: Pretest and post-test survey responses collected, focus group; analyzed using descriptive statistics/content analysis | Higher education and professional occupations positively impact interactions with trans persons in the juvenile justice system. Importance of how organizational work environments and culture can override personal beliefs, leading to reduced discrimination. |

Results

The searches were conducted on April 13, 2023, with seven publications being included upon final review (see Figure 1; Matarese et al., 2023). All articles received scores over 70% (agreed upon cut off) and were included in the study. While the searches were not restricted by country, only three countries were represented. Five studies were conducted in the United States (US), one in Canada and one in the United Kingdom (UK; see Table 2). Four studies were qualitative in methodology, one was quantitative, and two studies employed a mixed methods approach. Two doctoral dissertations met the inclusion criteria and were included as grey literature. Content analysis (Krippendorff, 2019) of each of these seven documents identified key concepts explored, including knowledge, attitude, and behaviors of correctional staff toward trans persons in adult (n = 5) and juvenile (n = 2) carceral settings. One study that involved trans correctional staff was included due to still meeting the criteria of exploring the knowledge, attitude, and behaviors of correctional staff for trans incarcerated people (Adorjan et al., 2021).

Correctional staff knowledge about needs of incarcerated trans people

Knowledge regarding how trans people’s carceral needs differ from that of non-trans people is an important consideration for more optimally supporting and upholding the health and rights of trans persons in carceral settings. As part of a focus group (N = 7), prison staff (defined as any official prison officers or workers) in Byrd’s study (2020) indicated knowledge about the various ways incarcerated trans people are more vulnerable in a prison setting than non-trans people. However, the study reported a lack of knowledge regarding their responsibilities in providing affirming care. These findings were supported by participants (N = 6) in Marlow, Winter and Elliot’s study (2015) as being generally representative of correctional staff (correctional officers), with the study reporting increased awareness following training, but with an ongoing lack of direction on how to implement changes. The awareness by correctional staff to the need for privacy among trans people in correctional settings was highlighted, with one prison official saying: “It becomes a little bit more difficult, I think, for the male population that is trying to transition into a female, because now they’re having these breasts and they’re in a dorm where they have to take showers. Sometimes, they don’t have the privacy they need” (Byrd, 2020, p. 51). Knowledge of trans people’s needs is important as such conditions can have a significant impact on incarcerated persons as it can exacerbate mental health concerns, as well as create an uncomfortable environment. One compliance specialist working within the carceral setting noted that during transitioning, individuals may not experience their expected physical changes, leading to emotional and mental challenges (Marlow et al., 2015). Correctional staff in Walker’s study (2020) expressed their concerns around ensuring juvenile trans people in particular were able to safely (physically, mentally) exist in the incarceration setting and cited specific policies as a key element. While these results demonstrate the awareness by staff of some key issues faced by incarcerated trans people, they are unfortunately being reported by a small population of participants (correctional staff including security and health care providers) within a small subset of the studies being reviewed.

While some staff demonstrated increased knowledge around the basic needs (e.g. safety) of incarcerated trans people, a lack of knowledge was also identified as a barrier to providing essential supports, such as appropriate healthcare. A lack of competency (both clinically and culturally safe practices) among correctional healthcare providers was demonstrated as a salient problem, highlighting low knowledge regarding the provision of gender-affirming care for incarcerated trans people (Clark et al., 2017). Healthcare providers within carceral settings frequently lacked the ability (e.g. willingness, organizational support) to provide and manage hormone therapies (Clark et al., 2017). This lack of support was also demonstrated in terms of mental health, with providers frequently linking trans identity with mental health issues (with co-morbidities in prison especially prominent due to pre-disposing and exacerbating factors; Clark et al., 2017). Clark et al. (2017) also found that the lack of staff competencies related to the care of trans people obstructed trans people’s access to essential care. Lack of trans cultural competency was due to healthcare providers’ perception that such requests/needs (social and medical) by trans persons in prison were manipulations to gain attention (Clark et al., 2017).

COs reported obtaining training on the needs of incarcerated trans people through self-directed learning, in-house training (intervention), and trans persons themselves. One social worker in Clark et al. (2017) reported that the only way to gain sufficient knowledge about trans health was to independently seek professional development outside the prison facility/workplace/environment, stating: “I have done trainings on my own. [Transgender health] was briefly covered in an LGBT training, and then just my own kind of readings. But [the prison] doesn’t offer anything in particular about it” (p. 82). Correctional staff in one study described obtaining in-house training from their employer. White Hughto et al. (2017) reported only a few correctional healthcare providers indicated they were culturally competent to provide trans care prior to intervention. Post-intervention 91.7% of participants reported obtaining increased knowledge due to the training intervention (developed by researchers as part of a pilot program), suggesting that such training can have positive impacts on competency. In some studies, correctional staff described leaning on incarcerated trans people for knowledge, with one participant stating:

I’ve only learnt that from him and what he’s told me and okay it might not be the same for everybody, but it’s given me a better understanding of things that might be difficult for people or the kind of process they might have gone through to get to that stage where they, they just even are aware that they might be in the wrong gender body (Marlow et al., 2015, p. 246).

A 2017 study showed that less than one quarter (23.5%) reported attending training on trans health (White Hughto et al., 2017). Lack of experience interacting with incarcerated people, including trans people, was a significant barrier for staff. It was reported that while staff were willing to discuss topics that are important to self-identity with those incarcerated, concerns and difficulties setting appropriate boundaries often arose (Marlow et al., 2015). The lack of regular training by facilities were identified by a social worker as a barrier that contributed to confusion among healthcare staff about gender-affirming care (Clark et al., 2017). Likewise, staff in Marlow et al. (2015) study reported concern that staff would not be able to adapt treatment appropriately due to a lack of specific skills and expertise. COs suggested their competency in working with trans youth could be improved through LGBTQIA + training and indicated the need for updates in organizational policies and procedures (Walker, 2020). However, some correctional staff were reported as being non-receptive and at times unwilling to engage in the use of correct pronouns and names when in a sex-segregated facility (Clark et al., 2017).

Correctional staff attitudes toward incarcerated trans people

Four out of the seven studies specifically described correctional staff attitudes toward trans people including stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs which often culminated in denial of healthcare services or lack of supportive policies (Byrd, 2020; Marlow et al., 2015; Walker, 2020; White Hughto et al., 2017). Attitudes held by COs toward incarcerated trans people ranged from enthusiastic (willingness to engage with and support) to disrespect (impacting stigma). This in turn impacted the level of appropriate and dignified gender-affirming care provided to incarcerated trans people in their facility. A baseline statistic for willingness to provide gender-affirming care was shown to be moderate within a pilot intervention study (White Hughto et al., 2017). Personal beliefs and backgrounds (implicit/explicit bias) were frequently noted as significant influences on staff attitudes, identified as directly impacting the way correctional staff treated and interacted with incarcerated persons, especially stigmatized and marginalized populations such as trans people (Marlow et al., 2015). White Hughto et al. (2017) indicated that staff reported in the follow-up measure having utilized what they had learnt in the trans cultural and clinical competence intervention, with 68% providing care for a trans person since participating in the intervention.

Walker’s study (2020) reported that an organization’s attitude toward the trans community had a direct impact on staff attitudes and behaviors. Walker (2020) also noted the importance of amending policies and procedures to directly address the needs of trans youth in carceral settings (Walker, 2020). Additionally, lack of management and leadership in enforcing related policies was evident throughout the studies, with participants reporting a lack of accountability for ensuring staff compliance to relevant policies (Byrd, 2020). This study reported that the lack of accountability from leadership meant that correctional staff were often comfortable ignoring professional policies, instead allowing the expression of personal beliefs and intolerance for the trans community to directly shape their behavior and interactions at work (Byrd, 2020). It was also noted that while standards had been established, correctional staff were often unsure about expectations or related consequences for any inappropriate or discriminatory behavior (Byrd, 2020).

Personal biases interfered with adherence to policies relating to care, with discrimination, oppression, marginalization and bigotry, frequently denied access to scheduled mental health and medical appointments shown toward incarcerated trans people, including trans-affirming correctional staff-members (Byrd, 2020). A para-militaristic hierarchy within the prison setting negatively influenced continued advocacy for any trans health patient, with one trans-affirming psychologist who worked in a male prison explaining:

It’s hard because I have to walk a fine line, I have to, like, align myself with custody, while still hearing the inmates too. Because if you get looked at by custody, they’ll call you an ‘inmate lover’ then they’ll shun you. But I see things here every day that I wish I didn’t have to see. They’ll yell at them, call them a piece of shit, they’re rough with them. It’s a very adversarial relationship and with me, they view me very differently (Clark et al., 2017, p. 84).

In Walker’s (2020) study, the frequent use of incorrect pronouns, names, and non-affirming language occurred during interviews with providers. Another study reported correctional staff (defined as including security, chaplaincy, management, mental health and support roles) frequently engaged in misgendering, erasure, denial and dismissal, with correctional staff taunting trans persons such as saying, “you are a female, because you are in a female facility” indicating a lack of knowledge (Byrd, 2020, p. 52).

At times, positive attitudes toward the treatment of trans persons were reported through the observation of consideration to the specific needs of individuals, and trans incarcerated persons as a group (Marlow et al., 2015). This was demonstrated through correctional staff being mindful to ensure they did not unintentionally cause any offense to the trans person by monitoring their gestures and body language, the use of preferred pronouns, adaptations to accommodation, and not drawing unnecessary/avoidable attention to the trans person, such as while celebrating “a transgendered awareness day” (Marlow et al., 2015, p. 249).

Correctional staff behaviors toward incarcerated trans people

Prison staff reported taking several factors into consideration in their interactions with incarcerated people, such as acknowledging that rapport building is of high importance in such an environment (Marlow et al., 2015). Knowledge was found to be directly correlated with demonstrating reported protective and supportive behaviors toward youth with diverse sexual orientations, gender identities, and expression (SOGIE; Matarese et al., 2023); behaviors that have also been shown to impact self-esteem and self-worth. Staff reported caution in their approach to ensure that offense is not caused with consideration given as to how incarcerated trans persons may perceive their actions (Marlow et al., 2015). Uncertainty about interactions also included being mindful of non-verbal (including body language, facial expressions and gestures) and verbal cues (paying attention to what is said; Marlow et al., 2015). One staff member reported: “I think if my face had leaked, if I had [given] something away, disapproval or something like that, that would have really damaged that relationship” (Marlow et al., 2015, p. 248). Boundary setting was also reported as an important aspect of the incarceration setting, particularly in regard to approaching potentially sensitive topics, with staff reporting being mindful of their level of engagement with trans people in comparison to others in order to be seen to treat everyone equally and to maintain rapport (Marlow et al., 2015). There were also reports that staff faced uncertainty in considering both criminological and trans-related factors (such as the level of helpfulness/friendliness given they are incarcerated) to inform interactions (Marlow et al., 2015).

Discussion

This scoping review elucidates timely and valuable insights into the existing literature regarding the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of correctional staff toward incarcerated trans adults and youth. These knowledges, attitudes, and behaviors are reported to have a significant impact on the lived experiences of incarcerated trans people, and would contribute to the increased stigmatization, discrimination and poorer health (physical and mental) outcomes previously reported (Brömdal et al., 2019; Brömdal et al., 2023; Clark et al., 2017; Creasy et al., 2023; Halliwell et al., 2023; Hughto & Clark, 2022; Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2016; Sumner & Sexton, 2016; White Hughto et al., 2018).

Operating within a reformist framework, several key findings were identified within the literature examining knowledge among correctional staff surrounding the unique needs of incarcerated trans persons. Studies reported correctional staff had a satisfactory level of knowledge of how trans persons experience greater vulnerabilities and have additional and unique basic needs as compared to non-trans persons in carceral settings. However, while the rights and importance of not being misgendered is clearly noted in the literature (Brömdal et al., 2019; Dalzell et al., 2023; Dolan et al., 2020; Sanders et al., 2023; Seely, 2021), some studies in this review demonstrate that this is not filtering down into practice with a reported lack of knowledge around appropriate engagement, including appropriate and preferred pronouns or names used by correctional staff when interacting with incarcerated trans persons (Byrd, 2020; Clark et al., 2017; Walker, 2020). Further within a reformist approach, and consistent with existing literature (McCauley et al., 2018; Mullens et al., 2017) several studies in this review highlighted incompetency brought about by a lack of training for healthcare providers (e.g. physicians, social workers, psychologists, mental health counselors) regarding trans health and gender-affirming needs, including medical and psychological healthcare, including within correctional settings (Brömdal et al., 2023; Byrd, 2020; Drakeford, 2018; Kendig et al., 2019; National Center for Transgender Equality, 2018a, 2018b; Van Hout & Crowley, 2021; Van Hout et al., 2020; Walker, 2020; White Hughto et al., 2017; White Hughto et al., 2018). Some correctional staff also reported their organization did not provide them with sufficient training on incarcerated trans persons’ needs, and as a result either engaged in independent learning outside of their organization or sought to learn directly from the person themselves to increase their competency (Clark et al., 2017, p. 82). Interpreted from a transformational lens, the so-called lack of knowledge and incompetency reported in these findings, including the oversight of not offering carceral staff gender-affirming training would collectively not be viewed as passive ignorance or oversights. Rather, they would be viewed as administrative, systemic, and structural attempts to maintain carceral control, where the ignorance and oversights are actively produced and reinforced by a dominant and neo-liberal cisnormative and heteronormative socio-cultural logic within and outside the carceral system (Ball, 2021; Clark et al., 2023; Lamble, 2015; Mitchell et al., 2022; Oparah, 2015; Spade, 2015; Stanley & Smith, 2015; Stanley et al., 2012; Walker et al., 2022).

Concern from correctional staff around safety was expressed, particularly in ensuring trans youth within the juvenile system were safe and included (Walker, 2020). A notable lack of literature was available on the lived experiences of trans adolescents in the incarceration setting, as also suggested elsewhere (Watson et al., 2023).

The attitudes of prison staff toward incarcerated trans people were reported as ranging from enthusiastic (willingness to engage and support) to a noticeable lack of respect. This large discrepancy was reported throughout the studies. While some staff reported understanding the need for sensitivity on some topics, as well as taking consideration and care to not ‘put the spotlight’ on trans people and their needs, other staff reported that trans issues were not of concern, instead focusing on the general issues of the prison setting (Marlow et al., 2015, p. 249). The latter attitude, within a transformative framework, is another act of violence toward trans people, which in turn actively contributes to diminishing and erasing the lives and experiences of trans people in carceral settings, in turn placing them at greater risk of harm (Lamble, 2014, 2015; Miles-Johnson, 2015; Mitchell et al., 2022; Spade, 2015; Stanley & Smith, 2015; Stanley et al., 2012). Some studies positively highlighted the impact of reformist organizational approaches and attitudes (such as policies and procedures) had on attitudes and the treatment of incarcerated trans person (Walker, 2020; White Hughto et al., 2017). However, several articles highlighted the ongoing lack of appropriate care for trans people, as well as significant denials of services (such as physical and mental health related), and a denial of acknowledging self-identity (Adorjan et al., 2021; Byrd, 2020). Consistent with other literature (Brömdal et al., 2019; Metwally et al., 2019; Tadros et al., 2020; Van Hout et al., 2020; White Hughto et al., 2018) the lack of leadership and clear direction or expectations was reported as other significant reformist factors on staff attitudes across studies. In an attempt to maintain carceral control, correctional authorities are known to disregard trans persons’ gender identity when disclosed and/or deny them access to medically necessary, gender-affirming care resulting in additional and inhumane punishment (Brömdal et al., 2019; Brömdal et al., 2023; Phillips et al., 2020; Sanders et al., 2023; Tadros et al., 2020).

Staff behavior was impacted by their knowledge and attitudes regarding trans persons as reported above. Consistent with existing literature, there were some clear factors that affected staff behavior in carceral settings. First, several staff articulated the importance of building rapport with incarcerated people, while being cautious and aware of their approach and need to treat people equally (Marlow et al., 2015). It was reported that boundary setting could be challenging when faced with unique needs of different people (Marlow et al., 2015). Some studies identified the impact that personal beliefs and attitudes had on staff behaviors, while some reported it did not affect their behavior, and others demonstrated a clear lack of awareness resulting in reduced quality of care and access to services (Byrd, 2020). Solutions such as the importance training and education can have on overcoming personal beliefs and attitudes, as well as organizational expectations helping to set clear requirements in quality of treatment (Brömdal et al., 2019; Brömdal et al., 2023; Matarese et al., 2023; Phillips et al., 2020; Redcay et al., 2020; Sevelius & Jenness, 2017; Tadros et al., 2020; Tarzwell, 2006; White Hughto et al., 2018) are reform-based attempts that seek “to improve the conditions inside of prisons or the people within them, but not to implement structural changes” (Lawston & Meiners, 2014, p. 13). As such, findings from this study highlight the urgent need to address the underlying structural, systemic, and organizational factors that impact upon the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors staff have and hold in correctional and other health and community settings to meaningfully and sustainably improve health, wellbeing and gender-affirming treatment and care for trans communities (Brömdal et al., 2019; Franks et al., 2022; McCauley et al., 2018; Mullens et al., 2017; Swan et al., 2023; Van Hout et al., 2020; Watson et al., 2023). As such, reform-based solutions are not sustainable in the long-term given the over-representation of trans and gender-diverse persons in the criminal legal system, limited prison spaces, and economic costs associated with building new prisons, including structures within existing prisons, let alone the human and societal costs (Lamble, 2015; Lawston & Meiners, 2014). Employing a transformative lens, it is possible to envisage an approach formulated outside a reformist justice system and its settings, that affirms the intersectional diversity of trans adults and youth, and their needs (Clark et al., 2023; Lamble, 2015; Oparah, 2015; Spade, 2015; Stanley & Smith, 2015; Stanley et al., 2012). This approach would provide an opportunity to reflect on and address the pervasive systemic discrimination and violence faced by trans adults and youth that hinders access to and excludes them from employment, housing, education, health, and family, and that aims to reduce the very need to undertake activities deemed illegal in order to survive (Stanley, 2015). To this end, eliminating transphobia through education rooted in social justice, and building cultures and institutions that embrace trans embodiment would not only contribute to reducing trans-biased policing practices (Grant et al., 2011; Miles-Johnson, 2015; Mitchell et al., 2022; Poteat et al., 2023) informing the over-representation of trans people in the prison system (Clark et al., 2023; Hughto et al., 2022; Reisner et al., 2014), but also make possible alternative methods of accountability for those who do harms (Lamble, 2015).

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations were identified within this study. First, the available literature on this topic was very limited making a full review difficult, which further illustrates the gap in the field, and adds weight to our claim that this is an emerging area of critical social importance. Correctional staff self-reported knowledge, attitudes and behaviors were likely influenced by several biases. It is possible that the correctional staff that participated in the existing studies were already interested in this area of research and/or providing a high level of appropriate care to their diverse incarcerated communities. It is also possible that the participants within the studies demonstrated social desirability bias and were aware of the intention of the research and so reflected on their interactions in a more positive way. It is important to note that the literature on incarcerated trans youth within the juvenile justice system is very limited, as demonstrated in this review (Walker, 2020) and elsewhere (Watson et al., 2023). As noted previously, the available literature within the trans incarcerated space is very limited globally, especially within the youth justice space. As such, it is not unexpected that the range of countries included in this review were limited to three geographical areas (Canada, the UK, and the US). The lack of research and data in this area may be due in part to the overall challenges of conducting research within correctional settings, and as such with correctional personnel. More specifically, it is widely acknowledged that pursuing research in carceral settings is obstructed by multiple barriers (Adams et al., 2017; Apa et al., 2012; Brömdal et al., 2019; Watson & van der Meulen, 2019). For example, researchers may experience challenges in obtaining approval to pursue research into the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of correctional staff toward trans people in their care by university ethics committees and/or correctional institutions. This may in part be due to the controversial nature of pursuing research related to this vulnerable population (Adams et al., 2017; Apa et al., 2012; Brömdal et al., 2019). Further to this, institutional barriers may be grounded in the carceral systems’ lack of familiarity with the research team, conflicting perspectives regarding research objectives and/or lack of willingness to forge a collaborative research relation (Apa et al., 2012; Watson & van der Meulen, 2019). The institutional barriers may be further exacerbated by an absence of mutual goals or research priorities due to the needs and culture within carceral settings, including possible fear of ‘uncovering’ and ‘unveiling’ controversial attitudes and behaviors by correctional staff toward trans people, in turn possibly resulting in negative publicity or institutional reviews among carceral centers (Apa et al., 2012; Brömdal et al., 2019; Watson & van der Meulen, 2019). Collectively, these barriers may restrict scholars to explore this space, however if overcome in the short-term they equally present themselves as opportunities to access correctional staff and point to an important research gap that warrants further exploration.

Conclusion

This scoping review provides valuable insight into correctional staff’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors toward incarcerated trans people. The findings within the seven literary artifacts were consistent with the wider existing reformist-informed literature, particularly regarding the lived experiences of trans incarcerated persons, including the emerging research concerning trans youth in the juvenile justice system (Watson et al., 2023). Within a short-term reformist framework, this collection of works highlights the importance of improved training and education, and changes to organizational procedures and policies to reduce the violence and harmful experiences of incarcerated trans adults and youth and uphold their rights and health while incarcerated. Such reform-based work would seek to enhance the conditions trans persons experience within carceral systems, however, they would not attempt to address the structural and systemic changes required to address the lifetime harms trans people experience from childhood to adulthood in diverse settings, including trans-biased policing procedures in turn informing the over-representation of trans people in carceral settings. Taken a step further, adopting a transformative approach, is where society and carceral systems, at large, are offered the opportunity to reflect on and address the pervasive systemic discrimination and violence trans adults and youth face that contribute to their overrepresentation in the prison systems (Clark et al., 2023; Hughto et al., 2022; LaChance & Dwyer, 2023; Reisner et al., 2014).

With the clear lack of existing literature worldwide on the experiences of both adult and youth incarcerated trans people, future research should focus on further exploring intersectional lived experiences, unique needs, policy changes, and more importantly structural and systemic changes that collectively may have short- and long-term positive impacts for trans people in contact with the law. Examination at an organizational level of policies and processes that are supported and support corrections management in meeting the immediate needs of incarcerated trans adults and youth would also be a beneficial area for future research. Informed by a transformative framework, research exploring the ways in which correctional staff may envision alternative methods of accountability for those who do harm, would be another much-needed research area contributing insights to the current body of work within queer criminology, decarceration and prison abolition.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank UniSQ research librarian Tricia Kelly for their assistance with the search terms and databases.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the University of Southern Queensland through an Internal Research Capacity Grant with the last author (AB) as the lead investigator [Project ID 1007573, 2020].

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Adams, N., Pearce, R., Veale, J., Radix, A., Castro, D., Sarkar, A., & Thom, K. C. (2017). Guidance and ethical considerations for undertaking transgender health research and institutional review boards adjudicating this research. Transgender Health, 2(1), 165–175. 10.1089/trgh.2017.0012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adorjan, M., Ricciardelli, R., & Gacek, J. (2021). ‘We’re both here to do a job and that’s all that matters’: Cisgender correctional officer recruit reflections within an unsettled correctional prison culture. The British Journal of Criminology, 61(5), 1372–1389. 10.1093/bjc/azab006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allspach, A. (2010). Landscapes of (neo-)liberal control: The transcarceral spaces of federally sentenced women in Canada. Gender, Place & Culture, 17(6), 705–723. 10.1080/0966369X.2010.517021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Apa, Z. L., Bai, R. Y., Mukherejee, D. V., Herzig, C. T. A., Koenigsmann, C., Lowy, F. D., & Larson, E. L. (2012). Challenges and strategies for research in prisons. Public Health Nursing (Boston, Mass.), 29(5), 467–472. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2012.01027.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, F. (2018). Genderfucking non-disclosure: Sexual fraud, transgender bodies, and messy identities. Dalhousie Law Journal, 41(2), 339–377. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, M. (2021). Queering penal abolition. In Coyle M. J. & Scott D. (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of penal abolition (pp. 179–189). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brömdal, A., Clark, K. A., Hughto, J. M. W., Debattista, J., Phillips, T. M., Mullens, A. B., Gow, J., & Daken, K. (2019). Whole-incarceration-setting approaches to supporting and upholding the rights and health of incarcerated transgender people. The International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(4), 341–350. 10.1080/15532739.2019.1651684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brömdal, A., Halliwell, S., Sanders, T., Clark, K. A., Gildersleeve, J., Mullens, A. B., Phillips, T. M., Debattista, J., Du Plessis, C., Daken, K., & Hughto, J. M. W. (2023). Navigating intimate trans citizenship while incarcerated in Australia and the United States. Feminism & Psychology, 33(1), 42–64. 10.1177/09593535221102224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brömdal, A., Mullens, A. B., Phillips, T. M., & Gow, J. (2019). Experiences of transgender prisoners and their knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding sexual behaviors and HIV/STIs: A systematic review. The International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(1), 4–20. 10.1080/15532739.2018.1538838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, J. M., Biernat, K., Shamaris, N., & Skerrett, V. (2022). The experience of transgender women prisoners serving a sentence in a male prison: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. The Prison Journal, 102(5), 542–564. 10.1177/00328855221121097 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G. R. (2014). Qualitative analysis of transgender inmates’ correspondence. Journal of Correctional Health Care: The Official Journal of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, 20(4), 334–342. 10.1177/1078345814541533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G. R., & McDuffie, E. (2009). Health care policies addressing transgender inmates in prison systems in the United States. Journal of Correctional Health Care: The Official Journal of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, 15(4), 280–291. 10.1177/1078345809340423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist, C. L., & Stone, C. (2014). Transgender victims and offenders: Failures of the United States criminal justice system and the necessity of queer criminology. Critical Criminology, 22(1), 35–47. 10.1007/s10612-013-9224-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, J. R. (2020). Transgender protection and best practices in the prison setting (Publication Number 9337) Walden University]. Minneapolis, MN. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/9337 [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Corrections & Rehabilitation . (2023). Senate Bill 132 FAQs. Retrieved 9 August 2023 from https://www.cdcr.ca.gov/prea/sb-132-faqs/

- Clark, K. A., Brömdal, A., Phillips, T., Sanders, T., Mullens, A. B., & Hughto, J. W. H. (2023). Developing the “oppression-to-incarceration cycle” of Black American and First Nations Australian trans women: Applying the intersectionality research for transgender health justice framework. Journal of Correctional Health Care: The Official Journal of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, 29(1), 27–38. 10.1089/jchc.21.09.0084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K. A., White Hughto, J. M., & Pachankis, J. E. (2017). “What’s the right thing to do?” Correctional healthcare providers’ knowledge, attitudes and experiences caring for transgender inmates. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 193, 80–89. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creasy, S. L., Hawk, M., Friedman, M. R., Mair, C., McNaboe, J., & Egan, J. E. (2023). Previously incarcerated transgender women in Southwestern Pennsylvania: A mixed methods study on experiences, needs, and resiliencies. Annals of LGBTQ Public and Population Health, 4(3), 281–296. May. 10.1891/LGBTQ-2021-0045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dalzell, L. G., Pang, S. C., & Brömdal, A. (2023). Gender affirmation and mental health in prison: A critical review of current corrections policy for trans people in Australia and New Zealand. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 0(0), 48674231195285. 10.1177/00048674231195285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, I. J., Strauss, P., Winter, S., & Lin, A. (2020). Misgendering and experiences of stigma in health care settings for transgender people. The Medical Journal of Australia, 212(4), 150–151.e1. e151. 10.5694/mja2.50497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakeford, L. (2018). Correctional policy and attempted suicide among transgender individuals. Journal of Correctional Health Care: The Official Journal of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, 24(2), 171–182. 10.1177/1078345818764110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Plessis, C., Halliwell, S., Mullens, A., Sanders, T., Gildersleeve, J., Phillips, T., & Brömdal, A. (2023). A trans agent of social change in incarceration: A psychobiographical study of Natasha Keating. Journal of Personality, 91(1), 50–67. 10.1111/jopy.12745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks, N., Mullens, A. B., Aitken, S., & Brömdal, A. (2022). Fostering gender-IQ: Barriers and Enablers to Gender-affirming Behavior Amongst an Australian General Practitioner Cohort. Journal of Homosexuality, 0(0), 1–24. 10.1080/00918369.2022.2092804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo, R., Deleon, J., Osmer, E., Doll, M., & Harper, G. W. (2006). 2006/03/01/) Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: Exploring the lives and HIV risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health : official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 38(3), 230–236. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, J. M., Mottet, L., Tanis, J. E., Harrison, J., Herman, J., Keisling, M. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality, and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, S. D., Du Plessis, C., Hickey, A., Gildersleeve, J., Mullens, A. B., Sanders, T., Clark, K. A., Hughto, J. M. W., Debattista, J., Phillips, T. M., Daken, K., & Brömdal, A. (2022). A critical discourse analysis of an Australian incarcerated trans woman’s letters of complaint and self-advocacy. Ethos (Berkeley, Calif.), 50(2), 208–232. 10.1111/etho.12343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, S., Hickey, A., Du Plessis, C., Mullens, A. B., Sanders, T., Gildersleeve, J., Phillips, T. M., Debattista, J., Clark, K. A., Hughto, J. M. W., Daken, K., & Brömdal, A. (2023). Never let anyone say that a good fight for the fight for good wasn’t a good fight indeed”: The enactment of agency through military metaphor by one Australian incarcerated trans woman. In Panter H. & Dwyer A. (Eds.), Transgender people and criminal justice: An examination of issues in victimology, policing, sentencing, and prisons (pp. 183–212). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-031-29893-6_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughto, J. M. W., Clark, K. A., Daken, K., Brömdal, A., Mullens, A. B., Sanders, T., Phillips, T., Mimiaga, M. J., Cahill, S., Du Plessis, C., Gildersleeve, J., Halliwell, S. D., & Reisner, S. L. (2022). Victimization within and beyond the prison walls: A latent profile analysis of transgender and gender diverse adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(23–24), NP23075–NP23106. 10.1177/08862605211073102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughto, J. W., & Clark, K. A. (2022). Transgender and gender diverse people and incarceration. In Keuroghlian A. S., Potter J., & Reisner S. L. (Eds.), Transgender and gender diverse health care: The fenway guide. McGraw Hill. accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?aid=1184177455 [Google Scholar]

- Hymas, C. (2019). One in 50 prisoners identifies as transgender amid concerns inmates are attempting to secure prison perks. The Telegraph. Retrieved 1 June 2023 from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/07/09/one-50-prisoners-identify-transsexual-first-figures-show-amid/

- Jaffer, M., Ayad, J., Tungol, J. G., Macdonald, R., Dickey, N., & Venters, H. (2016). Improving transgender healthcare in the New York City correctional system [Article]. LGBT Health, 3(2), 116–121. 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenness, V. (2021). The social ecology of sexual victimization against transgender women who are incarcerated: A call for (more) research on modalities of housing and prison violence. Criminology & Public Policy, 20(1), 3–18. 10.1111/1745-9133.12540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenness, V., & Fenstermaker, S. (2014). Agnes goes to prison: Gender authenticity, transgender inmates in prisons for men, and pursuit of “the real deal” [Article]. Gender & Society, 28(1), 5–31. 10.1177/0891243213499446 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenness, V., & Fenstermaker, S. (2016). Forty years after brownmiller: Prisons for men, transgender inmates, and the rape of the feminine [Article]. Gender & Society, 30(1), 14–29. 10.1177/0891243215611856 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joanna Briggs Institute . (2020). Critical appraisal tools. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

- Kendig, N. E., Cubitt, A., Moss, A., & Sevelius, J. (2019). Developing correctional policy, practice, and clinical care considerations for incarcerated transgender patients through collaborative stakeholder engagement. Journal of Correctional Health Care: The Official Journal of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, 25(3), 277–286. 10.1177/1078345819857113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. (4th ed.). 10.4135/9781071878781 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LaChance, D., & Dwyer, A. (2023). Transgender and gender non-conforming young people and the school-to-prison pipeline: Too crucial to ignore. In Panter H. & Dwyer A. (Eds.), Transgender people and criminal justice: An examination of issues in victimology, policing, sentencing, and prisons (pp. 73–96). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-031-29893-6_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamble, S. (2014). Queer investments in punitiveness: Sexual citizenship, social movements and the expanding carceral state*. In Haritaworn J., Kuntsman A., & Posocco S. (Eds.), Queer necropolitics (1st ed., pp. 151–171). Routledge. 10.4324/9780203798300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamble, S. (2015). Transforming carceral logics: 10 reasons to dismantle the prison industrial complex using a queer/trans analysis. In Stanley E. & Smith N. (Eds.), Captive genders: Trans embodiment and the prison industrial complex (2nd ed., pp. 269–299). AKA Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lawston, J. M., & Meiners, E. R. (2014). Ending our expertise: feminists, scholarship, and prison abolition. Feminist Formations, 26(2), 1–25. 10.1353/ff.2014.0012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma, E., & Ford, C. L. (2020). Health implications of housing assignments for incarcerated transgender women. American Journal of Public Health, 110(5), 650–654. 10.2105/ajph.2020.305565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallon, G. P., & Perez, J. (2020). The experiences of transgender and gender expansive youth in Juvenile justice systems. Journal of Criminological Research, Policy and Practice, 6(3), 217–229. 10.1108/JCRPP-01-2020-0017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marlow, K., Winder, B., & Elliott, H. J. (2015). Working with transgendered sex offenders: Prison staff experiences. Journal of Forensic Practice, 17(3), 241–254. 10.1108/JFP-02-2015-0013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matarese, M., Aaron Betsinger, S., & Weeks, A. (2023). The influence of juvenile justice workforce’s knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs on behaviors toward youth with diverse sexual orientations, gender identities, and expressions. Children and Youth Services Review, 148, 106917. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2023.106917 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley, E., Eckstrand, K., Desta, B., Bouvier, B., Brockmann, B., & Brinkley-Rubinstein, L. (2018). Exploring healthcare experiences for incarcerated individuals who identify as transgender in a southern jail. Transgender Health, 3(1), 34–41. 10.1089/trgh.2017.0046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metwally, D., Ruiz-Palomino, P., Metwally, M., & Gartzia, L. (2019). How ethical leadership shapes employees’ readiness to change: The mediating role of an organizational culture of effectiveness [original research]. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2493. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles-Johnson, T. (2015). Policing transgender people: discretionary police power and the ineffectual aspirations of one Australian Police Initiative. SAGE Open, 5(2), 215824401558118. 10.1177/2158244015581189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M., McCrory, A., Skaburskis, I., & Appleton, B. (2022). Criminalising gender diversity: Trans and gender diverse people’s experiences with the Victorian Criminal Legal System. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 11(2), 99–112. 10.5204/ijcjsd.2225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mountz, S. E. (2020). Remapping pipelines and pathways: Listening to queer and transgender youth of color’s trajectories through girls’ juvenile justice facilities. Affilia, 35(2), 177–199. 10.1177/0886109919880517 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mullens, A. B., Fischer, J., Stewart, M., Kenny, K., Garvey, S., & Debattista, J. (2017). Comparison of government and non-government alcohol and other drug (AOD) treatment service delivery for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community. Substance Use & Misuse, 52(8), 1027–1038. 10.1080/10826084.2016.1271430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Transgender Equality . (2018a). Ending abuse of transgender prisoners: A guide to winning policy change in jails and prisons. Retrieved 1 June 2023 from https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/EndingAbuseofTransgenderPrisoners.pdf

- National Center for Transgender Equality . (2018b). LGBTQ People Behind Bars: A Guide to understand the issues facing transgender prisoners and their legal rights. Retrieved 1 June 2023 from https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/TransgenderPeopleBehindBars.pdf

- Nulty, J. E., Winder, B., & Lopresti, S. (2019). “I’m not different, I’m still a human being […] but I am different.” An exploration of the experiences of transgender prisoners using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Forensic Practice, 21(2), 97–111. 10.1108/JFP-10-2018-0038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oparah, J. C. (2015). Maroon abolitionists: black gender-oppressed activists in the anti-prison movement in the US and Canada. In Stanley E. & Smith N. (Eds.), Captive genders: Trans embodiment and the prison industrial complex (2nd ed., pp. 327–356). AKA Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peek, C. (2004). Breaking out of the prison hierarchy: Transgender prisoners, rape, and the eighth amendment. Santa Clara Law Review, 44, 1211–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Penal Reform . (2022). Global prison trends 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2023 from https://www.penalreform.org/resource/global-prison-trends-2022/

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation, 13(3), 141–146. https://journals.lww.com/ijebh/fulltext/2015/09000/guidance_for_conducting_systematic_scoping_reviews.5.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, T., Brömdal, A., Mullens, A. B., Gildersleeve, J., & Gow, J. (2020). We don’t recognise transexuals…and we’re not going to treat you": Cruel and Unusual and the Lived Experiences of Transgender Women in US Prisons. In Harmes M., Harmes M., & Harmes B. (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of incarceration across popular culture (pp. 331–360). Palgrave MacMillan. 10.1007/978-3-030-36059-7_20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat, T. C., Humes, E., Althoff, K. N., Cooney, E. E., Radix, A., Cannon, C. M., Wawrzyniak, A. J., Schneider, J. S., Beyrer, C., Mayer, K. H., Brinkley-Rubinstein, L., Reisner, S., & Wirtz, A. L. (2023). Characterizing arrest and incarceration in a prospective cohort of transgender women. Journal of Correctional Health Care: The Official Journal of the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, 29(1), 60–70. 10.1089/jchc.21.10.0118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redcay, A., Luquet, W., Phillips, L., & Huggin, M. (2020). Legal battles: Transgender inmates’ rights. The Prison Journal, 100(5), 662–682. 10.1177/0032885520956628 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinl, J. (2022). The transgender prison experiment UNCOVERED: Male-to-female inmates in women’s cellblocks drive rising numbers of rapes and abuse on the new frontline in America’s culture wars. Retrieved 14 July 2023 from https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-11458335/Male-female-Trans-inmates-drive-rising-numbers-rapes-abuse-womens-prisons.html?ito=native_share_article-nativemenubutton

- Reisner, S. L., Bailey, Z., & Sevelius, J. (2014). Racial/ethnic disparities in history of incarceration, experiences of victimization, and associated health indicators among transgender women in the U.S [Article]. Women & Health, 54(8), 750–767. 10.1080/03630242.2014.932891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardelli, R., Phoenix, J., & Gacek, J. (2020). ‘It’s complicated’: Canadian correctional officer recruits’ interpretations of issues relating to the presence of transgender prisoners. The Howard Journal of Crime and Justice, 59(1), 86–104. 10.1111/hojo.12354 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, T., Gildersleeve, J., Halliwell, S., Du Plessis, C., Clark, K. A., Hughto, J. M. W., Mullens, A., Phillips, T., Daken, K., & Brömdal, A. (2023). Trans architecture and the prison as archive: “Don’t be a queen and you won’t be arrested. Punishment & Society, 25(3), 742–765. 10.1177/14624745221087058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seely, N. (2021). Reporting on transgender victims of homicide: Practices of misgendering, sourcing and transparency. Newspaper Research Journal, 42(1), 74–94. 10.1177/0739532921989872 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serano, J. (2016). Whipping girl: A transsexual woman on sexism and the scapegoating of femininity. Hachette UK. [Google Scholar]

- Sevelius, J., & Jenness, V. (2017). Challenges and opportunities for gender-affirming healthcare for transgender women in prison [Article]. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 13(1), 32–40. 10.1108/ijph-08-2016-0046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spade, D. (2015). Normal life: Administrative violence, critical trans politics, and the limits of law. Duke University Press. 10.1215/9780822374794 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, E., & Smith, N. (Eds.) (2015). Captive genders: Trans embodiment and the prison industrial complex. (2nd ed.). AK Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, E. A. (2015). Fugitive flesh: Gender self-determination, queer abolition, and trans resistance. In Stanley E. & Smith N. (Eds.), Captive genders: Trans embodiment and the prison industrial complex (2nd ed., pp. 7–17). AK Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, E. A., Spade, D., & Queer (In)Justice . (2012). Queering prison abolition, now? American Quarterly, 64(1), 115–127. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41412834 10.1353/aq.2012.0003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner, J., & Sexton, L. (2016). Same difference: The ‘dilemma of difference’ and the incarceration of transgender prisoners [Article]. Law & Social Inquiry, 41(03), 616–642. 10.1111/lsi.12193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swan, J., Phillips, T. M., Sanders, T., Mullens, A. B., Debattista, J., & Brömdal, A. (2023). Mental health and quality of life outcomes of gender-affirming surgery: A systematic literature review. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 27(1), 2–45. 10.1080/19359705.2021.2016537 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros, E., Ribera, E., Campbell, O., Kish, H., & Ogden, T. (2020). A call for mental health treatment in incarcerated settings with transgender individuals. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 48(5), 495–508. 10.1080/01926187.2020.1761273 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarzwell, S. (2006). The gender lines are marked with razor wire: Addressing state prison policies and practices for the management of transgender prisoners. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 38(167), 167–219. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hout, M. C., & Crowley, D. (2021). The “double punishment” of transgender prisoners: A human rights-based commentary on placement and conditions of detention. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 17(4), 439–451. 10.1108/IJPH-10-2020-0083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hout, M. C., Kewley, S., & Hillis, A. (2020). Contemporary transgender health experience and health situation in prisons: A scoping review of extant published literature (2000–2019). International Journal of Transgender Health, 21(3), 258–306. 10.1080/26895269.2020.1772937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, A., Petersen, A. M., Wodda, A., & Stephens, A. (2022). Why don’t we center abolition in queer criminology? Crime & Delinquency, 00111287221134595, 001112872211345. 10.1177/00111287221134595 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, T. (2020). Identifying what hinders effective interactions between correctional staff and transgender juvenile offenders (Publication Number 9008) Walden University]. Minneapolis, MN. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/9008

- Watson, J., Bryce, I., Phillips, T. M., Sanders, T., & Brömdal, A. (2023). Transgender youth, challenges, responses, and the juvenile justice system: A systematic literature review of an emerging literature. Youth Justice, 0(0), 147322542311673. 10.1177/14732254231167344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, T. M., & van der Meulen, E. (2019). Research in carceral contexts: Confronting access barriers and engaging former prisoners. Qualitative Research, 19(2), 182–198. 10.1177/1468794117753353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto, J. M., Clark, K. A., Altice, F. L., Reisner, S. L., Kershaw, T. S., & Pachankis, J. E. (2017). Improving correctional healthcare providers’ ability to care for transgender patients: Development and evaluation of a theory-driven cultural and clinical competence intervention. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 195, 159–169. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto, J. M., Clark, K. A., Altice, F. L., Reisner, S. L., Kershaw, T. S., & Pachankis, J. E. (2018). Creating, reinforcing, and resisting the gender binary: A qualitative study of transgender women’s healthcare experiences in sex-segregated jails and prisons. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 14(2), 69–88. 10.1108/IJPH-02-2017-0011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto, J. M., Reisner, S. L., & Pachankis, J. E. (2015). Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 147, 222–231. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M., Simpson, P. L., Butler, T. G., Yap, L., Richters, J., & Donovan, B. (2017). ‘You’re a woman, a convenience, a cat, a poof, a thing, an idiot’: Transgender women negotiating sexual experiences in men’s prisons in Australia [Article]. Sexualities, 20(3), 380–402. 10.1177/1363460716652828 [DOI] [Google Scholar]