Abstract

In the course of examining the various factors which affect the metabolism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) RNA, we examined the role of intron sequences and splice sites in determining the subcellular distribution of the RNA. Using in situ hybridization, we demonstrated that in the absence of Rev, unspliced RNA generated with an HIV-1 env expression construct displayed discrete localization in the nucleus, coincident with the location of the gene and not associated with SC35-containing nuclear speckles. Expression of Rev resulted in a disperse signal for the unspliced RNA throughout both the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Subsequent fractionation of the nucleus revealed that the majority of unspliced viral RNA within the nucleus is associated with the nuclear matrix and that upon expression of Rev, a small proportion of the unspliced RNA is found within the nucleoplasm. Mutations which altered splice site utilization did not alter the sequestration of unspliced RNA into discrete nuclear regions. In contrast, a 2.2-kb deletion of intron sequence resulted in a shift from discrete regions within the nucleus to a disperse signal throughout the cell, indicating that intron sequences, and not just splice sites, are required for the observed nuclear sequestration of unspliced viral RNA.

Control of RNA metabolism (splicing, transport to the cytoplasm, translation, and stability) plays an important role in determining the nature and quantity of a protein produced and, in the case of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), in determining the successful replication of the virus. From a single 9-kb primary transcript, more than 25 mRNAs are generated (20, 52). These mRNAs fall into three size classes: the unspliced, 9-kb mRNA encoding the Gag and Gag-Pol proteins; singly spliced, 4-kb mRNAs encoding the Vif, Vpr, Vpu, and Env proteins; and the doubly spliced, 2-kb mRNAs encoding the Tat, Rev, and Nef proteins (64). In addition to the requirement to maintain an appropriate balance of viral RNA splicing to ensure adequate levels of all the viral proteins, transport of the 9- and 4-kb viral RNAs to the cytoplasm is absolutely dependent on expression of the Rev protein (14, 15, 25, 35). Consequently, viral gene expression is found to consist of two phases: the early phase, during which proteins encoded by the 2-kb class of mRNAs are expressed, followed by the late phase, at which time the remaining viral proteins are produced (29, 30). Disruption of the transition from the early to the late phase of viral gene expression has been observed both in experimental systems and in patients, resulting in a latent infection established at the posttranscriptional level (7, 30, 38, 39, 46, 47, 54).

Sequestration of the unspliced and singly spliced viral RNAs in the nucleus has been attributed to either the entrapment of the RNAs into spliceosome complexes due to the inherent inefficiency of the HIV-1 splice sites (5, 9, 32) or the presence of cis-acting regulatory sequences (CRS) within the gag-pol and env sequences that form the introns of the 2-kb class of viral RNAs (6, 12, 33, 40, 48, 51, 53). Data in support of both hypotheses exist. Analysis of the mechanism by which Rev relieves the block to the transport of viral 9- and 4-kb mRNAs into the cytoplasm has demonstrated that it is dependent on the interaction of Rev with a 240-nucleotide (nt) sequence (designated the Rev-responsive element [RRE]) present within env (26, 43, 68). Mutational analysis has determined that the arginine-rich, amino-terminal portion (amino acids [aa] 1 to 68) is required for interaction with RRE RNA but is not sufficient for biological activity (11, 23, 26, 35, 48, 68). In addition to the RRE binding domain, a 10-aa sequence (aa 73 to 83) is essential for biological activity; this sequence, which has been demonstrated to be a nuclear export signal (16, 34, 37, 42), requires interaction with a host factor (hRIP/Rab, CRM1, or eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5a) in order to achieve export from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (4, 17, 18, 49, 58, 61). Recent work by our laboratory has demonstrated that Rev function requires interaction of Rev with newly synthesized target RNA in order to achieve export of the RNA to the cytosol (27). Consequently, rather than disrupting complexes that sequester HIV-1 RNA in the nucleus, it would appear that Rev functions in competition with the splicing/nuclear sequestration pathway and that once RNA has become committed to this latter pathway, it is no longer accessible to Rev-mediated nuclear export. Consequently, inhibition of Rev function might be achieved either by inhibiting the Rev-dependent pathway or accelerating the rate of entry of viral RNAs into the splicing/nuclear sequestration pathway.

In an effort to examine the factors affecting the entry of HIV-1 RNA into the nuclear sequestration/splicing pathway, we have examined the effects of various mutations on the subcellular distribution of an RNA corresponding to the 4-kb env RNA of HIV-1. Previous analyses of HIV-1 RNA subcellular distribution in infected cells or cells transfected with constructs expressing subgenomic fragments of HIV-1 have demonstrated that the unspliced viral RNA accumulates in discrete domains within the nucleus, with appearance of the RNA in the cytoplasm being dependent on the expression of Rev (3, 70). Using stable cell lines constitutively producing HIV-1 env mRNA but expressing Rev in a tetracycline-dependent fashion, we demonstrate that unspliced env mRNA is highly localized within the nucleus but that the nuclear distribution is altered upon Rev expression. Consistent with prior observations (3, 70), a significant proportion of unspliced env mRNA is localized to a discrete domain in the absence of Rev. In the presence of Rev, a disperse distribution throughout the nucleus and cytoplasm is observed in addition to an intense focus of staining within the nucleus. To discriminate between the two models for HIV-1 RNA nuclear retention (inefficient splicing versus CRS elements), we examined the effects of (i) modulating splice site utilization and (ii) deletion of intron sequences on the subcellular distribution of unspliced viral RNA. These studies revealed that mutations which dramatically reduce splice site efficiency had no effect on unspliced RNA distribution. In contrast, deletions which retain the endogenous splice sites and remove only intron sequences resulted in a dramatic redistribution of unspliced RNA throughout the cell. Finally, fractionation of the nucleus revealed that in the presence and absence of Rev, the majority of unspliced viral RNA is found associated with the nuclear matrix.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and transfections.

HeLa cells and COS-7 cells were maintained in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 μg of gentamicin sulfate per ml, and 2.5 μg of amphotericin B (Fungizone) per ml. The HeLa CMV*Rev/pgEnvHygro stable cell line was generated (61a) and maintained in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, gentamicin (50 μg/ml), amphotericin B (2.5 μg/ml), G418 (400 μg/ml), hygromycin B (200 μg/ml), puromycin (1 μg/ml), and tetracycline (1 μg/ml). Expression of the env gene by this cell line was maintained by replacement of the nef reading frame with the hygromycin resistance gene, rendering growth in hygromycin B dependent on expression and splicing of the inserted env expression cassette. In addition, Rev was placed under the control of a tetracycline-regulated promoter (21). Induction of Rev expression within these cell lines was achieved by growth for 5 days in the absence of tetracycline. COS-7 cells were transiently transfected as previously described (13). HeLa cells were transiently transfected by using the calcium phosphate reagent as described by the manufacturer (Pharmacia).

Plasmids.

Plasmids pgTat, pSVHTSB, and pSVCTSB have been previously described (35, 59). The HIV-1 sequences from the Hxb2 proviral clone (nucleotide numbering system corresponds to the sequence for GenBank accession no. KO3455) spanning nt 7131 to 8511, 8181 to 8511, or 8391 to 8511 were introduced into the EcoRV site of pBluescript (BlSK; Stratagene) to generate Bl-PT, Bl-HT, and Bl-CT, respectively. The KpnI/blunted-XbaI fragments from these plasmids were introduced into the KpnI/blunted-XhoI site of pgTat (35) to generate pgPT, pgHT, and pgCT, respectively. Bl-TatS/K was generated by insertion of the SalI-KpnI fragment from pgTat into the SalI-KpnI site of pBluescript SK+ (Stratagene). Bl-EnvHindIII was constructed by introducing the HIV-1 sequences spanning nt 6081 to 8181 into the HindIII site of pBluescript SK+ in the sense orientation relative to the T7 promoter. Bl-EnvΔnef was obtained by introducing the HIV-1 sequence spanning nt 8181 to 8831 into the HindIII/blunted-XbaI site of pBluescript SK+ in the sense orientation relative to the T7 promoter. pgTatΔESE was constructed by inserting the EcoRV-HindIII fragment from pSVHTΔpur (60) into the blunted-XbaI/HindIII site of pgTat, resulting in the insertion of linker sequences in addition to the HIV-1 sequences. pgTatΔESEΔESS was constructed by inserting the blunted-BamHI/HindIII fragment from pSVHH (60) into the blunted-XbaI/HindIII site of pgTat. To generate probes for S1 nuclease protection assays, the HindIII-ScaI fragments (encompassing the HIV-1 tat/rev 3′ splice site [3′ss] and the rat preproinsulin polyadenylation signal sequence) of pgTat, pgTatΔESE, and pgTatΔESEΔESS were cloned into the HindIII-EcoRV site of pBluescript SK+ to generate Bl-TatRPP, Bl-TatΔESERPP, and Bl-TatΔESEΔESSRPP.

In situ hybridization.

Probes used for in situ hybridization were generated as follows. To detect unspliced HIV-1 env mRNA from the HeLa CMV*Rev/pgEnvHygro cells, plasmid Bl-EnvHindIII was linearized with XhoI (antisense) or XbaI (sense) and used for generation of digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled RNA by in vitro transcription with T3 or T7 RNA polymerase, respectively, as detailed by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim). For colocalization of chromosomal viral DNA and RNA, a DNA-specific probe was generated by transcription of Bl-EnvHindIII linearized with XbaI (sense), using biotin-UTP (Boehringer Mannheim) in the nucleotide pool. Probes used to detect unspliced env mRNA from pgPT, pgHT, and pgCT consisted of antisense RNA generated by linearizing Bl-TatS/K with SspI followed by in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase by using DIG-UTP (Boehringer Mannheim). Finally, to detect unspliced RNA from pSVHTSB and pSVCTSB, a fragment was generated by PCR amplification using the pSVHTSB DNA as a template with the β-globin sense primer 5′-GGTGAGGCCCTGGGCAGG-3′ and the CTT7 antisense primer 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGAAACGATAATGGTGAAT-3′. The amplicon was subsequently used as a template for in vitro transcription (Boehringer Mannheim).

For in situ hybridization, we used a modification of the protocol of Lawrence et al. (31). HeLa cells grown on glass coverslips were harvested 48 h after transfection; coverslips were washed two or three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed at room temperature for 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS buffered to pH 7.4. Following fixation, coverslips were washed twice with PBS and stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C. For prehybridization, each coverslip was inverted onto a 100 μl of prehybridization solution (50% deionized formamide, 2× SSPE [1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA {pH 7.7}], 5× Denhardt’s reagent, 1 mg of tRNA per ml), and the chamber was sealed with Parafilm and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. For each sample, the appropriate RNA probe was resuspended at 1 to 4 ng/μl in fresh hybridization solution and heated at 80°C for 10 min. The coverslips were then placed onto 30 μl of fresh hybridization solution, and the chambers were sealed with Parafilm and incubated overnight at 37°C. Unbound probe was removed by four 15-min washes in 50% deionized formamide–2× SSPE at 37°C. Hybrids were detected by using sheep anti-DIG antibodies conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Boehringer Mannheim). Samples were incubated in 1% blocking reagent (Boehringer Mannheim) containing sheep anti-DIG-FITC (1/40 dilution). Unbound antibody was removed by four 15-min washes at room temperature in 0.1 M maleic acid–0.15 M NaCl (pH 7.4). In some instances, samples were stained with propidium iodide for 1 min at 0.5 μg/ml in PBS, for detection of the cell nuclei. Samples were mounted in antibleach medium (Boehringer Mannheim) and stored in the dark at 4°C.

To examine colocalization of HIV-1 env mRNA relative to splicing factors, samples were incubated with 1% blocking reagent (Boehringer Mannheim) containing mouse monoclonal anti-SC35 antibody (Sigma) after unbound RNA probes had been removed. Samples were then washed and incubated with both FITC-conjugated sheep anti-DIG antibody (1/40 dilution) and Texas red-conjugated donkey anti-mouse antibody (1/80 dilution). To examine relative localization of HIV-1 env mRNA and DNA, fixed cells were heated at 70°C for 2 min in 70% deionized formamide–2× SSPE prior to hybridization with RNA probes. Cells were incubated with sense biotinylated RNA (1 to 4 ng/μl) and antisense DIG-RNA (1 to 4 ng/μl) and incubated at 42°C overnight. Following removal of excess RNA probe, hybrids were detected by incubation in 1% blocking reagent (Boehringer Mannheim) containing FITC-conjugated sheep anti-DIG antibody (1/40 dilution) and Texas red-conjugated avidin (15 μg/ml). Unbound antibody was removed, and samples were mounted as detailed above. Samples were subsequently analyzed by laser-scanning confocal microscopy using a Zeiss LSM 410 inverted microscope as described previously (3). In general, images were captured at a magnification of approximately ×1,500 except in instances where large fields of cells are shown, in which case magnification was ×350.

Subcellular fractionation.

At 48 h posttransfection, cells transfected with expression vectors were separated into nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions as previously described (22). In brief, cells were washed once with cold PBS and then lysed on the plate in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–250 mM sucrose–25 mM NaCl–5 mM MgCl2–1.0% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40 (NP-40). After lysis was monitored by microscopy, the supernatant was collected and cleared of cellular debris by centrifugation (250 × g, 4°C, 5 min) and RNA was precipitated by addition of isopropanol (the resultant pellet was designated the cytoplasmic fraction). The nuclei (which remain attached to the surface of the petri dish) were subjected to two washes on ice under more stringent conditions: 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–3 mM CaCl2–2 mM MgCl2–1.0% (vol/vol) NP-40, 1% (wt/vol) sodium deoxycholate. To isolate RNA from each fraction, 600 μl of 4 M guanidine thiocyanate–25 mM sodium citrate (pH 7.0)–0.5% Sarkosyl–0.1 M β-mercaptoethanol was added to the isopropanol precipitate or nuclei remaining on the plate, and the sample was processed as previously described (10).

Nuclear matrix preparations were prepared from HeLa CMV*Rev/pgEnvHygro cells. Cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS, 1.5 ml (per 10-cm-diameter dish) of extraction buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 250 mM sucrose, 25 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% [vol/vol] NP-40) was gently added, and the petri dish was placed on ice. Lysis of the plasma membrane was monitored with a microscope but was usually complete within 10 min. The lysate (designated the cytoplasmic fraction) was collected and cleared of cellular debris by centrifugation (250 × g, 4°C, 5 min). RNA was precipitated with isopropanol and resuspended in 600 μl of 4 M guanidine thiocyanate–25 mM sodium citrate (pH 7.0)–0.5% Sarkosyl–0.1 M β-mercaptoethanol. The nuclei (which remain attached to the surface of the petri dish) were subjected to two washes on ice under more stringent conditions: 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–3 mM CaCl2–2 mM MgCl2–0.5% (vol/vol) NP-40–1% (wt/vol) sodium deoxycholate. The nuclei were further processed into the insoluble matrix fraction and soluble nucleoplasmic fraction by the ammonium sulfate matrix extraction protocol (2) as follows. One milliliter of TM-2 buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) was added to the nuclei on ice; the nuclei were gently scraped off the plate, transferred to a conical tube, and incubated at room temperature for 1 min and then for 5 min on ice. After addition of Triton X-100 to 0.5% (vol/vol), the nuclei were incubated on ice for an additional 5 min, sheared by passage through a 22-gauge needle three times, separated from any remaining cytoplasmic components by centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 6 min at 4°C, washed twice in TM-2 buffer, and resuspended to a DNA concentration of ∼1 mg/ml. MgCl2 was added to the nuclei in TM-2 buffer to a final concentration of 5 mM. DNase I (RNase free) digestion was then performed by adding DNase I (30 IU/mg of DNA; Boehringer Mannheim) for 45 min at 4°C. Following digestion, an equal volume of (NH4)2SO4 in TM-0.2 buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 0.2 mM MgCl2) was slowly added to a final concentration of at least 0.2 M. The total volume was brought to 6 ml by adding TM-0.2 buffer containing the appropriate salt concentration and centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 15 min at 4°C; the pellet fraction corresponds to the matrix fraction, while the supernatant was designated the nucleoplasmic fraction. RNA from the nucleoplasmic fraction was precipitated with isopropanol and resuspended in 600 μl of 4 M guanidine thiocyanate–25 mM sodium citrate (pH 7.0)–0.5% Sarkosyl–0.1 M β-mercaptoethanol. The matrix fraction was directly resuspended in 600 μl of 4 M guanidine thiocyanate–25 mM sodium citrate (pH 7.0)–0.5% Sarkosyl–0.1 M β-mercaptoethanol, and RNA was isolated from the three fractions as previously described (10).

S1 nuclease protection analysis.

The DNA fragment used as the probe to detect the 5′ splice site (5′ss) was from the SalI-PvuII fragment of Bl-TatS/K encompassing the 5′ss of the HIV-1 tat/rev intron. To distinguish reannealed probe from protected probe resulting from unspliced RNA, DNA fragments contained heterologous, BlSK-derived DNA sequences. This DNA fragment was radiolabeled at the SalI site by using [α-32P]dCTP with Klenow enzyme (50). The probes for the 3′ss were derived from the HindIII-NdeI fragments from Bl-TatRPP, Bl-TatΔESERPP, and Bl-TatΔESEΔESSRPP. The 3′ss probes were treated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (Pharmacia) to dephosphorylate the 5′ end of the DNA fragments and radiolabeled at the 5′ end with [γ-32P]ATP by using T4 polynucleotide kinase. The probe used to detect spliced and unspliced env mRNA from the HeLa CMV*Rev/pgEnvHygro cells was generated by in vitro transcription of Bl-EnvΔnef linearized with HindIII (antisense) with [α-32P]GTP as indicated by manufacturer (Promega). Probes used to hybridize RNA from pSVHTSB and pSVCTSB have been described previously (60). Hybridization and S1 protection assays were carried out as described previously (60).

RESULTS

Localization of HIV-1 env unspliced RNA in stable cell lines.

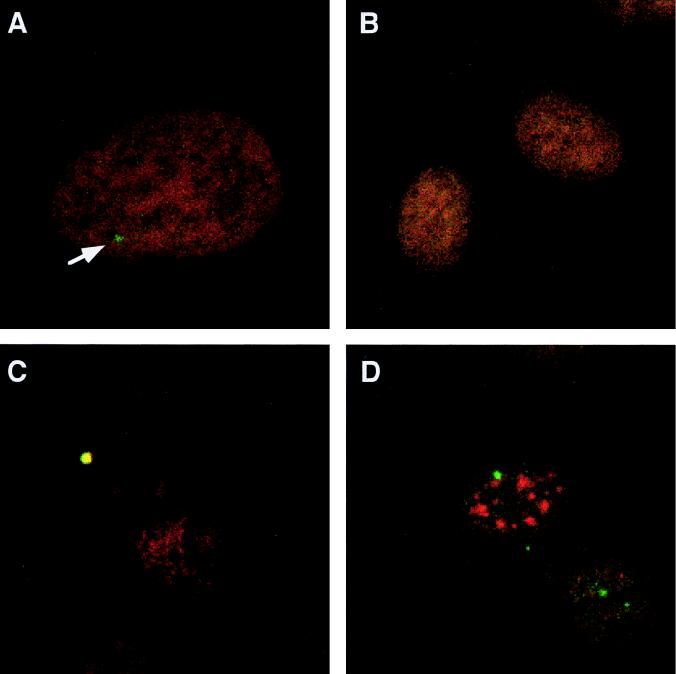

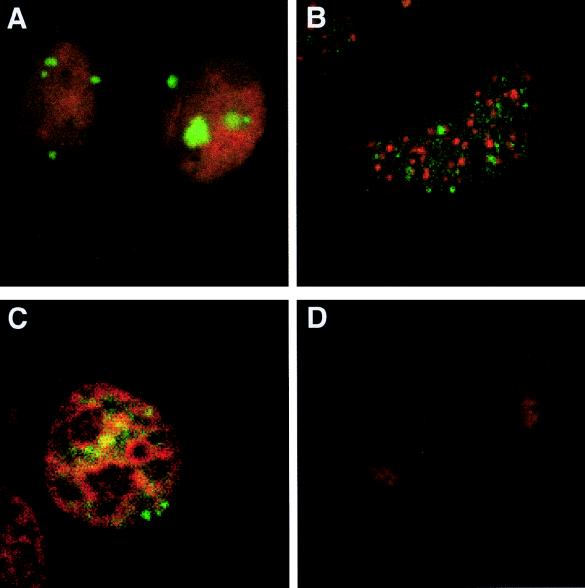

To determine the intracellular distribution of the stably expressed unspliced HIV-1 env mRNA, we used HeLa CMV*Rev/pgEnv Hygro, a stable cell line that constitutively produces HIV-1 env mRNA but in which Rev expression is dependent on removal of tetracycline from the medium. Hybridization to unspliced HIV-1 env mRNA (pseudocolored in green) in the absence of Rev expression revealed that the unspliced RNA was located in the nucleus as a discrete signal (Fig. 1A). Hybridization observed in Fig. 1A was specific since the sense RNA probe failed to give rise to any signal (Fig. 1B). Detection of a singular point of hybridization is not unexpected and probably reflects a single site of integration of the transgene within this stable cell line. To determine whether unspliced HIV-1 env mRNA accumulated at the site of transcription, following denaturation, cells were hybridized to DIG-labeled antisense RNA probe and biotinylated sense RNA probe. RNA- and DNA-specific signals were obtained by laser-scanning confocal microscopy, and individual signals were overlaid to assess their relative positions. As shown in Fig. 1C, the signal of HIV-1 unspliced env mRNA exactly colocalized with its corresponding DNA-dependent signal (resulting in the observed yellow signal). In agreement with previous observations (3, 70), analysis of the localization of env mRNA relative to nuclear speckles revealed that unspliced env mRNA does not colocalize with the sites of splicing factor accumulation (as indicated by the SC35 staining pattern (19, 56) (Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

In situ detection of unspliced HIV-1 env pre-mRNA. HeLa CMV*/Rev/pgEnv Hygro cells uninduced for Rev expression were fixed, hybridized to DIG-labeled antisense (A, C, and D) or sense (B) RNA probes to HIV-1 env sequences, and immunostained with anti-DIG antibody conjugated to FITC. (A and B) Cells counterstained with propidium iodide. The arrow in panel A indicates the position of unspliced HIV-1 env mRNA. (C) Cells hybridized to DIG-labeled antisense and biotinylated sense RNA probes. Hybrids were detected with anti-DIG antibody conjugated to FITC (green) and Texas red-avidin (red). Superpositioning of the two signals results in yellow signal. (D) Location of nuclear speckles, determined by using anti-SC35 antibody (red). The immunofluorescence images were scanned separately by confocal microscopy and stored as overlaid pictures.

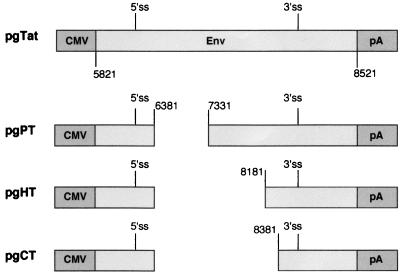

In contrast to the discrete localization of unspliced HIV-1 env mRNA in the absence of Rev (Fig. 2A), induction of Rev expression resulted in a dispersed signal throughout the cell for the unspliced HIV-1 RNA in addition to a discrete focus within the nucleus (Fig. 2B). The observed phenotypes in both the absence and presence of Rev expression were observed in all cells (Fig. 2C and D). Subsequent optical Z sectioning by confocal microscopy confirmed that the signal for unspliced env mRNA was detectable throughout the nucleus in the presence of Rev (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Intranuclear distribution of unspliced HIV-1 env mRNA in the presence or absence of Rev expression. HeLa CMV*/Rev/pgEnv Hygro cells were grown for 5 days in the absence (A and C) or presence (B and D) of Rev expression, fixed, hybridized to DIG-labeled antisense RNA probe specific to HIV-1 unspliced env RNA, and immunostained with FITC-conjugated anti-DIG antibody (green). In all panels, cells were stained with anti-SC35 antibody (red).

Unspliced HIV-1 env mRNA within the nucleus is found in association with the nuclear matrix.

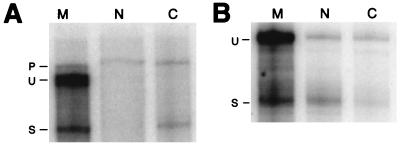

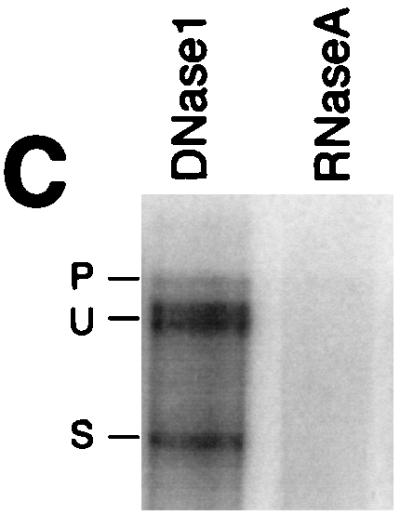

In light of the many reports that have demonstrated a tight association of cellular pre-mRNAs with the nuclear insoluble structural framework known as the nuclear matrix (41, 45, 57, 67, 69), we were interested in determining if HIV-1 unspliced env mRNA associated with the nuclear matrix as a possible basis for the observed nuclear retention. The protocol of Belgradier et al. (2) was used to prepare nuclear matrix from isolated nuclei of HeLa CMV*Rev/pgEnv Hygro cells. The RNA associated with the nuclear matrix was isolated and analyzed by S1 protection. To ensure that the RNA probes, specific for unspliced and spliced HIV-1 env RNA, were protecting RNA and not DNA, the samples were treated with either DNase I (RNase free) or RNase A prior to hybridization with probe (Fig. 3C). The S1 protection experiments revealed that the DNase I-treated sample still generated the anticipated protection pattern whereas the RNase A-treated sample lost all (both unspliced and spliced) protection products. This result confirms that the nucleic acid detected in the matrix fractions was indeed RNA and not attributable to residual DNA within the preparations. The HeLa CMV*Rev/pgEnv Hygro cells were grown in the presence or absence of tetracycline and subsequently fractionated into matrix, nucleoplasmic, and cytoplasmic fractions. S1 protection of the env unspliced RNA from each of these fractions revealed that the RNA was indeed associated with the nuclear matrix in both the absence (Fig. 3A) and presence (Fig. 3B) of Rev. In cells incubated in the presence of tetracycline, we detected no RNA in the nucleoplasmic fraction and only spliced RNA in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3A). In contrast, upon induction of Rev expression, we detected unspliced and spliced RNA in the nucleoplasm and in the cytoplasm, consistent with the export of unspliced RNA (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

S1 analysis of HIV-1 env RNA present in the nuclear matrix. HeLa CMV*/Rev/pgEnv Hygro cells, in the absence (A) or presence (B) of Rev, were used for nuclear matrix preparations; 10 μg of either matrix (M), nucleoplasmic (N), or cytoplasmic (C) RNA was used in S1 protection reactions. Bands corresponding to unspliced and spliced protection products are labeled U and S, respectively. (C) The matrix-associated nucleic acid was aliquoted into two samples and treated with either DNase I (RNase free) or RNase A prior to S1 protection analysis. Bands corresponding to unspliced and spliced protection products are labeled U and S, respectively.

Deletion of exon splicing regulatory elements does not alter nuclear retention of HIV-1 unspliced pre-mRNA.

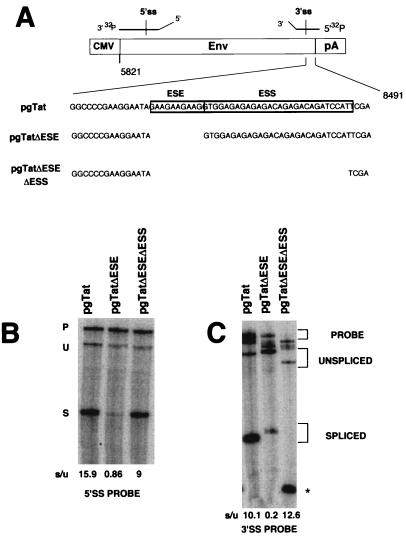

Previous suggestions that suboptimal splicing (9) is responsible for the nuclear retention of HIV-1 unspliced env mRNA led us to evaluate whether modifying HIV-1 splice site utilization affected RNA nuclear distribution. Toward this end, we analyzed the effects of deletion mutations on splicing efficiency and nuclear retention by S1 protection and in situ hybridization. To alter splice site efficiency, mutations were focused on the exon splicing enhancer (ESE) and exon splicing silencer (ESS) within the terminal tat/rev exon (60). To verify the effects of the deletions on splice site utilization, S1 protection analyses were carried out to monitor both tat/rev 5′ss and 3′ss use. S1 protection of a region encompassing the 5′ss revealed that pgTatΔESE RNA resulted in ∼20-fold reduction in spliced RNA compared to the wild-type pgTat RNA (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 and 2). This result confirms previous results on the role of the ESE in affecting splicing efficiency of the HIV-1 tat/rev intron (1, 60). However, despite the decrease in spliced RNA abundance, no reciprocal increase in unspliced RNA was observed for pgTatΔESE. The failure of unspliced RNA to accumulate could be attributed to an increased rate of degradation due to a failure to be engaged by the splicing machinery of the cell. In contrast to pgTatΔESE, the extent of utilization of the tat/rev 5′ss in the pgTatΔESEΔESS construct was comparable to that observed with pgTat (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 and 3). The results indicated that in all constructs, the HIV-1 tat/rev 5′ss was being correctly utilized. To determine if the HIV-1 tat/rev intron 3′ss was correctly used in these constructs, S1 protection analysis of a region encompassing the 3′ss was carried out. Consistent with the analysis in Fig. 4B, pgTatΔESE displayed reduced accumulation of spliced product (Fig. 4C, lanes 1 and 2) relative to pgTat. In sharp contrast, protection at the tat/rev 3′ splice site for the pgTatΔESEΔESS RNA revealed that a cryptic splice site rather than the correct HIV-1 3′ss was used (Fig. 4C, lane 3). This result suggests that the ESS functions to mask not only the authentic HIV-1 tat/rev 3′ss but also adjacent cryptic splice sites.

FIG. 4.

Effects of exonic splicing regulatory elements on utilization of tat/rev splice sites. CMV, cytomegalovirus early promoter; pA, simian virus 40 early polyadenylation signal. (A) Schematic representation of the pgTat, pgTatΔESE, and pgTatΔESEΔESS constructs. Positions of probes for analysis of both 5′ss and 3′ss are indicated. (B and C) COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with pgTat, pgTatΔESE, or pgTatΔESEΔESS and harvested 48 h posttransfection; then 10 μg of total RNA was analyzed by S1 nuclease protection assay. End-labeled probes used for the S1 protection encompassed either the 5′ss (B) or the 3′ss (C). Bands corresponding to unspliced and spliced protection products are labeled U and S, respectively. Reannealed probe is labeled P, and the asterisk denotes the position of a spliced product generated by use of a cryptic splice site for pgTatΔESEΔESS. The increased size of the spliced product generated from pgTatΔESE relative to pgTat is due to the presence of additional linker sequences inserted during construction of the clone. Indicated at the bottom panels B and C are the ratios of spliced to unspliced RNA (s/u) for each of the constructs as determined by quantitation using a PhosphorImager.

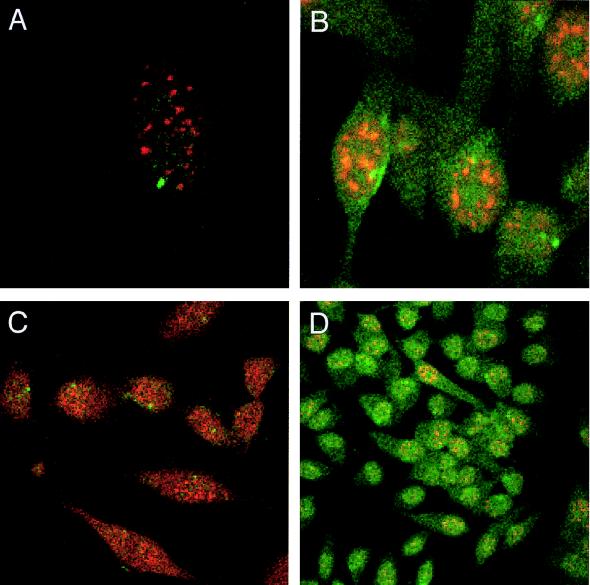

Having determined the effects of these mutations on splice site usage, we examined their effects on RNA subcellular distribution. pgTat, pgTatΔESE, and pgTatΔESEΔESS were transiently transfected into HeLa cells, and in situ analysis for unspliced HIV-1 env mRNA was carried out. For all constructs examined, unspliced env mRNA in the nucleus was distributed as small dot-like granules and did not differ from that of pgTat (Fig. 5A to C, pseudocolored in green). Similarly, colocalization experiments revealed that the pgTat, pgTatΔESE, and pgTatΔESEΔESS unspliced RNAs do not colocalize with the nuclear speckles, as revealed by staining with anti-SC35 antibody (pseudocolored in red in Fig. 5) (19, 56).

FIG. 5.

Effect of HIV-1 splice site utilization on env mRNA subcellular distribution. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with pgTat (A and D) pgTatΔESE (B), or pgTatΔESEΔESS (C); 48 h posttransfection, cells were fixed, hybridized to antisense (A to C) or sense (D) DIG-labeled RNA probe specific to HIV-1 unspliced env RNA, and immunostained with anti-DIG antibody conjugated to FITC (green). (A to C) Cells immunostained with anti-SC35 antibody (red); (D) cells counterstained with propidium iodide.

Sequences in addition to the splicing signals are required to effect nuclear retention of HIV-1 env unspliced mRNA.

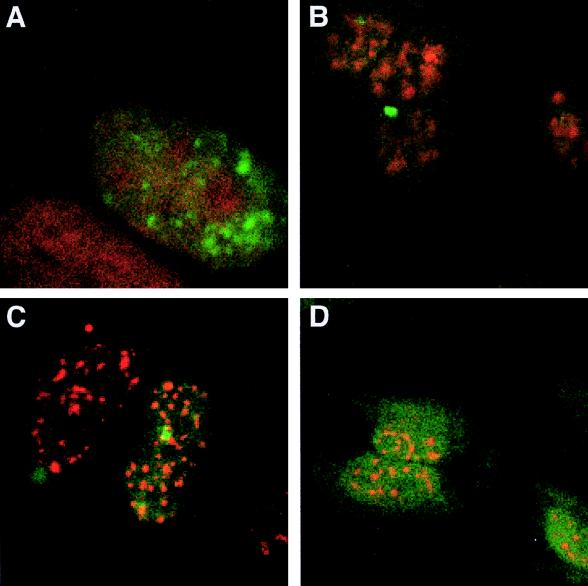

The failure of splicing mutants to alter the subcellular distribution of env mRNA raised the possibility that intron sequences play a role in determining the observed nuclear staining pattern. Therefore, we examined the subcellular distribution of the unspliced RNA from plasmids pgPT, pgHT, and pgCT by fluorescence in situ hybridization. In these constructs, the intron consisted of 1.95, 0.9, and 0.7 kb, respectively, of HIV-1 sequence, in addition to both the 5′ss and 3′ss (Fig. 6). In situ hybridization using antisense DIG-labeled RNA probes specific for the unspliced env mRNA revealed the presence of the RNA in the nucleus, as granules in the case of the pgTat, pgPT, and pgHT constructs (Fig. 7A to C, green). Deletion of 0.7 kb of the tat/rev intron in pgPT and of 1.7 kb in pgHT did not alter the intranuclear localization of these RNAs; the unspliced RNAs remained punctuate and nuclear. However, deletion of an additional 200 bp, generating pgCT, revealed the presence of unspliced RNA as a diffuse signal throughout the cell (Fig. 7D). Moreover, the RNA from pgCT no longer displayed a punctuate localization within the nucleus. As before, none of the unspliced RNAs from pgPT, pgHT, or pgCT colocalized with the SC35 splicing factor (Fig. 7B to D, red).

FIG. 6.

Schematic representation of pgPT, pgHT, and pgCT mutant constructs containing various deletions within the HIV-1 tat/rev intron. CMV, CMV early promoter; pA, simian virus 40 early polyadenylation signal.

FIG. 7.

In situ detection of unspliced RNA from deletion mutants. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with pgTat (A), pgPT (B), pgHT (C), or pgCT (D); 48 h posttransfection, cells were fixed, hybridized to antisense DIG-labeled RNA probe specific to unspliced RNA, and immunostained with anti-DIG antibody conjugated to FITC (green). In all panels, cells were immunostained with anti-SC35 antibody (red).

Sequences required for nuclear pre-mRNA enrichment can function in a chimeric context.

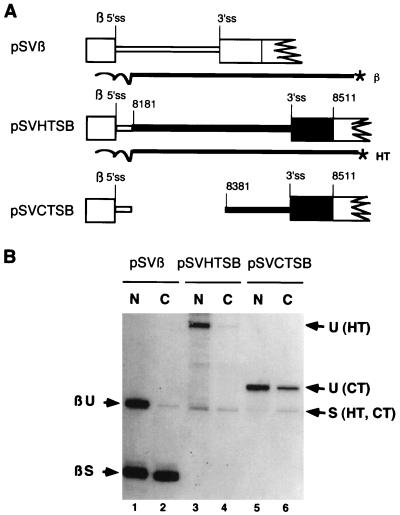

The effect of tat/rev intron deletions on RNA subcellular distribution suggested that the 200-nt region deleted from pgHT to generate pgCT was responsible for the punctate staining pattern observed within the nucleus. However, the pg series of constructs also contain the tat/rev 5′ss and approximately 300 nt of intron sequence adjacent to the 5′ss. Consequently, to verify that the staining pattern is attributable to the 200-nt sequence alone, we used a second set of a constructs (pSVHTSB and pSVCVTSB) which place HT and CT fragments in the context of a chimeric intron replacing the HIV-1 tat/rev 5′ss with the β-globin 5′ss (59). These constructs also position the 5′ end of the HIV-1 sequences within 25 nt of the β-globin 5′ss such that use of any cryptic 3′ss in this region would be detected by the S1 probes used. Cells were transfected with pSVβ, pSVHTSB, or pSVCTSB (Fig. 8A) (59) and fractionated into nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. Plasmid pSVβ contains the first intron of the human β-globin gene and served as a control to mimic cellular genes whose pre-mRNAs are retained in the nucleus. Indeed, the unspliced pSVβ pre-mRNA was predominantly nuclear (Fig. 8B, lanes 1 and 2). Unspliced pSVHTSB pre-mRNA was also predominantly nuclear, with only low levels being detected in the cytoplasm (Fig. 8B, lanes 3 and 4). In contrast, a significant amount of unspliced pSVCTSB pre-mRNA was detected in the cytoplasm (Fig. 8B, lane 5 and 6) despite the fact that a similar accumulation of spliced RNA relative to pSVHTSB was observed.

FIG. 8.

Subcellular distribution of unspliced and spliced chimeric RNA. (A) Schematic representation of chimeric β-globin/HIV-1 introns. Exons are depicted as boxes, and introns are shown as lines. Empty boxes and lines denote sequences of the parental plasmid, pSVβ; black boxes and lines denote HIV-1 sequences. The chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) open reading frame (not shown) is located further downstream in the second exon. β 5′ss, β-globin 5′ss; 3′ss, HIV-1 tat/rev intron 3′ss. The HIV-1-derived sequences in pSVHTSB include 236 nt of the tat/rev intron and 85 nt of the HIV-1 downstream exon. pSVCTSB differs from pSVHTSB only in the deletion of ∼200 nt of intron sequence as indicated. Also shown are the probes used for the detection of the unspliced and spliced RNA from the constructs. Homologous sequence spanned from the EcoRI site within the CAT gene to 25 nt 3′ of the 5′ss. The β probe was used to probe RNA from pSVβ. The HT probe was used to analyze RNA from both pSVHTSB and pSVCTSB. (B) S1 nuclease protection analysis of subcellular RNA (5 μg of either nuclear [N] or cytoplasmic [C] RNA) isolated from COS-7 cells transfected with pSVβ, pSVHTSB, or pSVCTSB. 5′-end-labeled probes used for S1 analysis span part of the CAT gene and the entire HIV-1 segment and contain heterologous sequences (wavy line) at their 3′ ends. Bands corresponding to unspliced (U) and spliced (S) protection products of pSVHTSB (HT) or pSVCTSB (CT) are indicated.

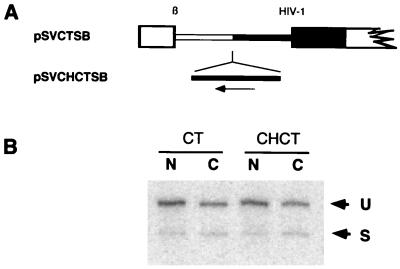

The 82-nt intron of pSVCTSB is ∼200 nt smaller than that of pSVHTSB. To rule out the possibility that unspliced RNA generated by pSVCTSB accumulated in the cytoplasm due to a decrease in intron size relative to pSVHTSB, deleted sequences were inserted in the inverse orientation (pSVCHCTSB) to restore intron size (Fig. 9A). As shown in Fig. 9B, the presence of such stuffer sequences did not significantly alter either the efficiency of splicing or the subcellular distribution of the unspliced and spliced RNA generated by these vectors.

FIG. 9.

HIV-1 nuclear retention sequences function in an orientation-specific fashion. (A) Schematic representation of pSVCHCTSB, a construct designed to test the effect of intron size on export of unspliced RNA. A HindIII-ClaI fragment was inserted in the antisense orientation into the unique SalI site at the junction of β-globin and HIV-1 sequences in pSVCTSB to restore the intron size to that of pSVHTSB. (B) S1 nuclease protection analysis of subcellular RNA (5 μg of either nuclear [N] or cytoplasmic [C] RNA) isolated from COS-7 cells transfected with pSVCTSB or pSVCHCTSB. The probe used for S1 analysis was the HT probe (Fig. 8A). Bands corresponding to unspliced and spliced protection products are labeled U and S, respectively.

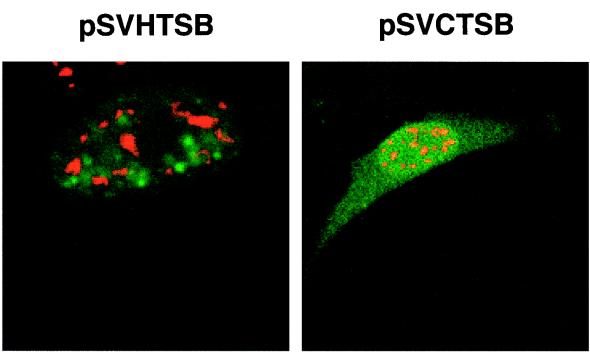

The small amount of unspliced pSVβ RNA and pSVHTSB RNA detected in the cytoplasm by S1 analysis probably reflects a low level of nuclear disruption during the fractionation. To confirm the S1 protection data, we transiently transfected pSVHTSB and pSVCTSB into cells and examined the intracellular location of the unspliced pre-mRNAs by in situ hybridization using DIG-labeled probes specific for the introns of these unspliced pre-mRNAs. Fluorescence in situ hybridization using a probe consisting of the intron sequences revealed that the pSVHTSB unspliced mRNAs were present as dot-like granules in the nucleus (Fig. 10, green). In contrast, the pSVCTSB unspliced pre-mRNAs were present as a diffuse signal throughout the cell (Fig. 10, green) and showed no punctate pattern of localization within the nucleus, similar to the pattern seen for pgCT (Fig. 7D).

FIG. 10.

In situ detection of unspliced chimeric RNA. pSVHTSB or pSVCTSB was transiently transfected into HeLa cells; 48 h posttransfection, cells were fixed, hybridized to an antisense DIG-labeled RNA probe corresponding to the intron sequences of both constructs, and immunostained with anti-DIG antibody conjugated to FITC (green). Cells were also immunostained with anti-SC35 antibody (red).

DISCUSSION

Previous analysis of the nuclear distribution of unspliced HIV-1 RNAs had demonstrated that RNAs containing either the gag or env sequence were found to be localized to discrete foci within the nucleus (3, 70). However, in the case of env sequences, a diffuse signal throughout the nucleus was also observed. The use of transient transfection within these studies does introduce some degree of variability due to differences in the extent of DNA uptake from cell to cell as well as variation from transfection to transfection. Use of the stable cell line HeLa CMV*Rev/pgEnvhygro allowed us to study the effect of Rev expression within a uniform population of cells, providing a highly reproducible system for the study of changes in unspliced viral RNA distribution in response to Rev. As in the previous studies, unspliced viral RNA was observed to accumulate in a discrete focus coincident with the location of the gene. In addition, the site of RNA accumulation was distinct from that of the nuclear speckles, sites of splicing factor assembly and storage (19, 56, 57). This observation does not preclude that splicing factors are present at the site of HIV-1 RNA accumulation, only that they do not accumulate to a significant extent there. The fact that splicing of the RNA must occur to produce the drug resistance phenotype used to generate the cell line suggests that splicing factors are present. In contrast to observations for the transient transfection system examined previously (3, 70), there was little or no signal detectable above background outside of the foci within the nuclei, reflecting retention of unspliced RNA close to the site of synthesis. Induction of Rev expression did not abolish the intense foci of RNA but resulted in a diffuse distribution throughout the cell. Optical Z sectioning confirmed that a diffuse signal throughout the nucleus was present in a Rev-dependent fashion (data not shown). This finding is significant and conflicts with a model for a singular path of movement of RNA from its site of synthesis to site of export from the nucleus. The Rev-induced dispersal of unspliced viral RNA throughout the nucleus suggests a random movement of the RNA destined for transport through the nuclear pore. Maintenance of the focal regions of RNA within the nucleus in the presence of Rev is also consistent with the previously proposed model that only a fraction of viral RNA within the nucleus is susceptible to Rev-induced transport to the cytoplasm (27). The fractionation studies presented here imply that the discrete localization of unspliced viral RNA is achieved by the interaction of the RNA with the insoluble scaffold within the nucleus designated the nuclear matrix (41, 45, 67, 69). Analysis of nuclear matrix composition has revealed the presence of factors involved in multiple processes including DNA synthesis, RNA polymerase II transcription, and RNA splicing (36, 44, 55, 57, 62, 63, 67, 69). The observed shift in unspliced viral RNA distribution from the matrix-associated fraction into both nucleoplasm and cytoplasm upon induction of Rev is consistent with the observed shift in distribution seen by in situ analysis. However, it is unclear at present whether the appearance of RNA in the nucleoplasm is the result of the release of RNA from the matrix fraction or movement of RNA from the site of transcription prior to an interaction with the nuclear matrix.

Previous evaluation of the mechanism for the retention of HIV-1 RNA in the nucleus had suggested that it was the result of inefficient splice sites within the RNA (9). This conclusion was reached by analysis of the effects of mutations within the 5′ss and 3′ss of the β-globin intron on its subcellular distribution and the capacity of Rev to effect transport to the cytoplasm of unspliced RNA in an RRE-dependent manner. It was observed that mutations in either the conserved GT or AG of the splice site sequences resulted in nuclear accumulation of unspliced RNA which required Rev for transport to the cytoplasm in the presence of the RRE. Mutation of both sites resulted in transport of the unspliced RNA to the cytoplasm in the absence of Rev (9). If nuclear sequestration was solely due to the formation of partial spliceosomes on the RNA, then one would anticipate that nuclear retention would depend solely on the splice sites and be unaffected by changes in intron sequences outside the splicing signals. In addition, formation of these pseudo-spliceosome complexes could result in accumulation of splicing components at the site of RNA accumulation, as this has been seen for some efficiently spliced RNAs (8, 28, 55, 65, 66). The failure to observe colocalization of unspliced env mRNA with nuclear speckles raised questions as to the role of splicing in the nuclear sequestration of the RNA, particularly in light of the demonstration of a high degree of association of nuclear speckles with regions of transcription of intron-containing vector DNA for efficiently spliced, transiently expressed genes (28). Failure to observe colocalization of unspliced viral RNA with nuclear speckles may reflect the inefficient nature of the intron present (59). To study the role of splicing in HIV-1 RNA nuclear retention in greater detail, we examined the effect of modulating the splicing efficiency of the tat/rev intron on RNA subnuclear distribution. To alter tat/rev intron splicing efficiency, we made use of the previously identified splicing regulatory elements within the terminal tat/rev exon: an ESE that increases the efficiency of the adjacent env 3′ss and an ESS that counteracts the effect of the ESE (60). As shown in Fig. 4, deletion of the ESE resulted in a ∼20-fold reduction in spliced RNA generated but no alteration in its subcellular distribution relative to the unmodified vector (Fig. 5). Failure of the ESE deletion to affect unspliced RNA distribution raised the possibility that nuclear retention is attributable to an inhibitory complex formed by the action of the ESS. Deletion of both the ESE and ESS restored splicing efficiency (albeit through the use of a cryptic 3′ss) but failed to alter the nuclear distribution of the RNA. Therefore, modulating splice site efficiency has no effect on the subnuclear distribution of the viral RNA.

As an alternative approach to assess whether the inefficient tat/rev 3′ss was sufficient for the nuclear sequestration of unspliced viral RNA, the effect of removal of intron sequences on unspliced RNA distribution was also examined. As shown in Fig. 7, deletion of a significant proportion (∼2.2 kb) of the tat/rev intron sequences resulted in a dramatic shift in unspliced RNA subcellular distribution from the discrete foci within the nucleus to uniform distribution throughout the cell. This finding is significant in that all constructs tested retained both the 5′ss and the 3′ss of the HIV-1 tat/rev intron, indicating that the splice sites are not sufficient for the retention of HIV-1 RNA in the nucleus. Deletion analysis of intron sequences demonstrated that a 200-nt sequence 5′ of the 3′ss was sufficient for nuclear retention of the unspliced RNA (comparable in distribution pattern to that seen for constructs containing the full intron, pSVHTSB versus pgTat). Introduction of the 200-nt sequence in the inverted orientation failed to result in nuclear retention of the unspliced RNA (Fig. 9), indicating that the effect cannot be ascribed to intron size but rather appears to be sequence dependent. The identification of this nuclear retention element does not conflict with previous reports that suggested the presence of multiple CRS elements within the env region (6, 33, 40, 48), as this study defines the minimal element required for nuclear sequestration and does not test for the presence of redundant elements elsewhere. Previous work has shown that nuclear sequestration of env RNA is dependent on the presence of a 5′ss since deletion of the 5′ss and the presence of an efficiently spliced intron are sufficient to permit transport of env RNA into the cytoplasm in a Rev-independent manner (24, 32). The fact that the 200-nt sequence confers nuclear retention in the context of a chimeric intron (consisting of the β-globin 5′ss [pSVHTSB]) indicates that there are no unique features within the HIV-1 5′ss required for the observed sequestration of the unspliced RNA.

The determination that an element within the intron is required for the nuclear sequestration of unspliced viral RNA and that it functions in the absence of the previously characterized exon splicing control elements (ESE and ESS) of HIV-1 indicates that multiple processes operate to yield the observed pattern of HIV-1 RNA metabolism. Understanding the mechanism by which these elements (nuclear retention, ESE, and ESS) function and how their effects could be modulated will add to our understanding of the control of not only HIV-1 RNA metabolism but also mRNA metabolism in general, given that the factors involved are derived from the host cell.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

B.S. is a recipient of a scholarship from Fonds pour la formation de Chercheurs et l’Aide a la Recherche. A.S. is supported by a studentship from the Medical Research Council of Canada. A.C. is supported by a scholar award from the Medical Research Council of Canada. Research was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council of Canada and Health Canada under the auspices of the National Health and Research Development Program.

We thank Howard Lipshitz for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amendt B, Si Z, Stoltzfus C M. Presence of exon splicing silencers within human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat exon 2 and tat-rev exon 3: evidence for inhibition mediated by cellular factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4606–4615. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belgradier P, Siegel A J, Berezney R. Nuclear matrix. J Cell Sci. 1991;98:281–291. doi: 10.1242/jcs.98.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berthold E, Maldarelli F. cis-acting elements in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNAs direct viral transcripts to distinct intranuclear locations. J Virol. 1996;70:4667–4682. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4667-4682.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogerd H, Fridell R, Madore S, Cullen B. Identification of a novel cellular cofactor for the Rev/Rex class of retroviral regulatory proteins. Cell. 1995;82:485–494. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90437-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borg K, Favaro J, Arrigo S. Involvement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 splice sites in the cytoplasmic accumulation of viral RNA. Virology. 1997;236:95–103. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brighty D W, Rosenberg M. A cis-acting repressive sequence that overlaps the Rev-responsive element of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 regulates nuclear retention of env mRNAs independently of known splicing signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8314–8318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butera S, Roberts B, Lam L, Hodge T, Folks T. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA expression by four chronically infected cell lines indicates multiple mechanisms of latency. J Virol. 1994;68:2726–2730. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2726-2730.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter K, Bowman D, Carrington W, Fogarty K, McNeil J, Fay F, Lawrence J. A three-dimensional view of precursor messenger RNA metabolism within the mammalian nucleus. Science. 1993;259:1330–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.8446902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang D D, Sharp P A. Regulation by HIV Rev depends upon recognition of splice sites. Cell. 1989;59:789–795. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90602-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cochrane A W, Chen C-H, Rosen C. Specific interaction of the HIV Rev transactivator protein with a structured region in the env mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1198–1201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cochrane A W, Jones K S, Beidas S, Dillon P J, Skalka A M, Rosen C A. Identification and characterization of intragenic sequences which repress human immunodeficiency virus structural gene expression. J Virol. 1991;65:5305–5313. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5305-5313.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cullen B R. Use of eukaryotic expression technology in the functional analysis of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1988;152:684–704. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emerman M, Vazeux R, Peden K. The rev gene product of the human immunodeficiency virus affects envelope-specific RNA localization. Cell. 1989;57:1155–1165. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felber B K, Hadzopoulou-Cladaras M, Cladaras C, Copeland T, Pavlakis G N. The rev protein of HIV-1 affects the stability and transport of the viral mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1495–1499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer U, Huber J, Boelens W, Mattaj I, Luhrmann R. The HIV-1 Rev activation domain is a nuclear export signal that accesses an export pathway used by specific RNAs. Cell. 1995;82:475–483. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90436-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fornerod M, Ohno M, Yoshida M, Mattaj I. CRM1 is an export receptor for leucine-rich nuclear export signals. Cell. 1997;90:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritz C, Zapp M, Green M. A human nucleoporin-like protein that specifically interacts with HIV Rev. Nature. 1995;376:530–533. doi: 10.1038/376530a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu X-D, Maniatis T. Factor required for mammalian spliceosome assembly is localized to discrete regions in the nucleus. Nature. 1990;343:437–444. doi: 10.1038/343437a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furtado M, Balachandran R, Gupta P, Wolinsky S. Analysis of alternatively spliced human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mRNA species, one of which encodes a novel Tat-Env fusion protein. Virology. 1991;185:258–270. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90773-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gossen M, Bujard H. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenberg M, Ziff E. Stimulation of 3T3 cells induces transcription of the c-fos proto-oncogene. Nature. 1984;311:433–438. doi: 10.1038/311433a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hadzopoulou-Cladaras M, Felber B K, Cladaras C, Athanassopoulos A, Tse A, Pavlakis G N. The Rev (Trs/Art) protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 affects viral mRNA and protein expression via a cis-acting sequence in the env region. J Virol. 1989;63:1265–1274. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1265-1274.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammarskjold M-L, Li H, Rekosh D, Prasad S. Human immunodeficiency virus env expression becomes Rev independent if the env region is not defined as an intron. J Virol. 1994;68:951–958. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.951-958.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammarskjöld M L, Heimer J, Hammarskjöld B, Sangwan I, Albert L, Rekosh D. Regulation of human immunodeficiency virus env expression by the rev gene product. J Virol. 1989;63:1959–1966. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.1959-1966.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heaphy S, Dingwall C, Ernberg I, Gait M J, Green S M, Karn J, Lowe A D, Singh M, Skinner M A. HIV-1 regulator of virion expression (Rev) protein binds to an RNA stem-loop structure located within the Rev response element. Cell. 1990;60:685–693. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90671-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iacampo S, Cochrane A. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev function requires continued synthesis of its target mRNA. J Virol. 1996;70:8332–8339. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8332-8339.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jimenez-Garcia L F, Spector D L. In vivo evidence that transcription and splicing are coordinated by a recruiting mechanism. Cell. 1993;73:47–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90159-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim S, Byrn R, Groopman J, Baltimore D. Temporal aspects of DNA and RNA synthesis during human immunodeficiency virus infection: evidence for differential gene expression. J Virol. 1989;63:3708–3713. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.3708-3713.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laughlin M, Pomerantz R. Retroviral latency. R. G. Austin, Tex: Landes Company; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawrence J B, Villnave C A, Singer R H. Sensitive, high-resolution chromatin and chromosome mapping in situ: presence and orientation of two closely integrated copies of EBV in a lymphoma line. Cell. 1988;52:51–61. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90530-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu X, Heimer J, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold M-L. U1 small nuclear RNA plays a direct role in the formation of a rev-regulated human immunodeficiency virus env mRNA that remains unspliced. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7598–7602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maldarelli F, Martin M A, Strebel K. Identification of posttranscriptionally active inhibitory sequences in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA: novel level of gene regulation. J Virol. 1991;65:5732–5743. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5732-5743.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malim M H, Bohnlein S, Hauber J, Cullen B R. Functional dissection of the HIV-1 rev trans-activator—derivation of a trans-dominant repressor of rev function. Cell. 1989;58:205–214. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90416-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malim M H, Hauber J, Le S-Y, Maizel J V, Cullen B R. The HIV-1 rev trans-activator acts through a structured target sequence to activate nuclear export of unspliced viral mRNA. Nature. 1989;338:254–257. doi: 10.1038/338254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattern K, van Goethem R, de Jong L, van Driel R. Major internal nuclear matrix proteins are common to different human cell types. J Cell Biochem. 1997;65:42–52. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(199704)65:1<42::aid-jcb5>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyer B, Meinkoth J, Malim M. Nuclear transport of human immunodeficiency virus type 1, visna virus, and equine infectious anemia virus Rev proteins: identification of a family of transferable nuclear export signals. J Virol. 1996;70:2350–2359. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2350-2359.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michael N, Mo T, Merzouki A, O’Shaughnessy M, Oster C, Burke D, Redfield R, Birx D, Cassol S. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cellular RNA load and splicing patterns predict disease progression in a longitudinal cohort. J Virol. 1995;69:1868–1877. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1868-1877.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michael N, Morrow P, Mosca J, Vahey M, Burke D, Redfield R. Induction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression in chronically infected cells is associated primarily with a shift in RNA splicing patterns. J Virol. 1991;65:1291–1303. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1291-1303.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nasioulas G, Zolotukhin A, Tabernero C, Solomin L, Cunningham C, Pavlakis G, Felber B. Elements distinct from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 splice sites are responsible for the Rev dependence of env mRNA. J Virol. 1994;68:2986–2993. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2986-2993.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nickerson J A, Krocmalnic G, Wan K M, Penman S. The nuclear matrix revealed by eluting chromatin from a cross-linked nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4446–4450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olsen H, Beidas S, Dillon P, Rosen C A, Cochrane A W. Mutational analysis of the HIV-1 Rev protein and its target sequence, the Rev responsive element. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:558–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olsen H, Nelbock P, Cochrane A, Rosen C. Secondary structure is the major determinant for interaction of HIV Rev protein with RNA. Science. 1990;247:845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.2406903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pardoll D, Vogelstein B, Coffey D. A fixed site of replication in eukaryotic cells. Cell. 1980;19:527–536. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Penman S. Rethinking cell structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5251–5257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pomerantz R, Seshamma T, Trono D. Efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 requires threshold level of rev: potential implications for latency. J Virol. 1992;66:1809–1813. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1809-1813.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pomerantz R, Trono D, Feinberg M, Baltimore D. Cells nonproductively infected with HIV-1 exhibit an aberrant pattern of viral RNA expression: a molecular model for latency. Cell. 1990;61:1271–1276. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosen C A, Terwilliger E, Dayton A, Sodroski J G, Haseltine W A. Intragenic cis-acting art gene-responsive sequences of the human immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2071–2075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruhl M, Himmelspach M, Bahr G, Hammarschmid F, Jaksche H, Wolff B, Aschauer H, Farrington G, Probst H, Bevec D, Hauber J. Eukaryotic initiation factor 5A is a cellular target of the human immunodeficiency virus type I Rev activation domain mediating trans-activation. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1309–1320. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwartz S, Campbell M, Nasioulas G, Harrison J, Felber B, Pavlakis G. Mutational inactivation of an inhibitory sequence in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 results in Rev-independent gag expression. J Virol. 1992;66:7176–7182. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7176-7182.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwartz S, Felber B K, Benko D M, Fenyo E-M, Pavlakis G N. Cloning and functional analysis of multiply spliced mRNA species of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1990;64:2519–2529. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2519-2529.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwartz S, Felber B K, Pavlakis G N. Distinct RNA sequences in the gag region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 decreases RNA stability and inhibit expression in the absence of Rev protein. J Virol. 1992;66:150–159. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.150-159.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seshamma T, Bagrasa D, Trono D, Baltimore D, Pomerantz R. Blocked early-stage latency in the peripheral blood cells of certain individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10663–10667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singer R H, Green M R. Compartmentalization of eukaryotic gene expression: causes and effects. Cell. 1997;91:291–294. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spector D L. Higher order nuclear organization: three-dimensional distribution of small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:147–152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spector D L. Macromolecular domains within the cell nucleus. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:265–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stade K, Ford C, Guthrie C, Weis K. Exportin 1 (Crm 1p) is an essential nuclear export factor. Cell. 1997;90:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Staffa A, Cochrane A. The tat/rev intron of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is inefficiently spliced because of suboptimal signals in the 3′ splice site. J Virol. 1994;68:3071–3079. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3071-3079.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Staffa A, Cochrane A. Identification of positive and negative splicing regulatory elements within the terminal tat-rev exon of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4597–4605. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stutz F, Neville M, Rosbash M. Identification of a novel pore-associated protein as a functional target of the HIV-1 Rev protein in yeast. Cell. 1995;82:495–506. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90438-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61a.Swenarchuck, •., et al. Unpublished data.

- 62.Vaughn J, Dijkwel P, Mullenders L, Hamlin J. Replication forks are associated with the nuclear matrix. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1965–1969. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.8.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vogelstein B, Hunt B. A subset of small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle antigens is a component of the nuclear matrix. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1982;105:1224–1232. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)91099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wong-Staal F. Human immunodeficiency viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, editors. Fields virology. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1990. pp. 1529–1543. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xing Y, Johnson C V, Dobner P R, Lawrence J B. Higher level organization of individual gene transcription and RNA splicing. Science. 1993;259:1326–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.8446901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xing Y, Johnson C V, Moen P T, McNeil J A, Lawrence J B. Nonrandom gene organization: structural arrangements of specific pre-mRNA transcription and splicing with SC-35 domains. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1635–1647. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xing Y, Lawrence J B. Preservation of specific RNA distribution within the chromatin-depleted nuclear substructure demonstrated by in situ hybridization coupled with biochemical fractionation. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:1055–1063. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.6.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zapp M, Green M. Sequence-specific RNA binding by the HIV-1 Rev protein. Nature. 1989;342:714–716. doi: 10.1038/342714a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zeitlin S, Parent A, Silverstein S, Efstratiadis A. Pre-mRNA splicing and the nuclear matrix. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:111–120. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Z, Zapp M, Yan G, Green M. Localization of HIV-1 RNA in mammalian nuclei. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:9–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]