Abstract

BACKGROUND

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM), which is a complication of diabetes, poses a great threat to public health. Recent studies have confirmed the role of NLRP3 (NOD-like receptor protein 3) activation in DCM development through the inflammatory response. Teneligliptin is an oral hypoglycemic dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitor used to treat diabetes. Teneligliptin has recently been reported to have anti-inflammatory and protective effects on myocardial cells.

AIM

To examine the therapeutic effects of teneligliptin on DCM in diabetic mice.

METHODS

Streptozotocin was administered to induce diabetes in mice, followed by treatment with 30 mg/kg teneligliptin.

RESULTS

Marked increases in cardiomyocyte area and cardiac hypertrophy indicator heart weight/tibia length reductions in fractional shortening, ejection fraction, and heart rate; increases in creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), aspartate transaminase (AST), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels; and upregulated NADPH oxidase 4 were observed in diabetic mice, all of which were significantly reversed by teneligliptin. Moreover, NLRP3 inflammasome activation and increased release of interleukin-1β in diabetic mice were inhibited by teneligliptin. Primary mouse cardiomyocytes were treated with high glucose (30 mmol/L) with or without teneligliptin (2.5 or 5 µM) for 24 h. NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Increases in CK-MB, AST, and LDH levels in glucose-stimulated cardiomyocytes were markedly inhibited by teneligliptin, and AMP (p-adenosine 5‘-monophosphate)-p-AMPK (activated protein kinase) levels were increased. Furthermore, the beneficial effects of teneligliptin on hyperglycaemia-induced cardiomyocytes were abolished by the AMPK signaling inhibitor compound C.

CONCLUSION

Overall, teneligliptin mitigated DCM by mitigating activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Keywords: Diabetic cardiomyopathy, Teneligliptin, NLRP3, AMPK, Interleukin-1β

Core Tip: Teneligliptin mitigated diabetic cardiomyopathy by mitigating the activation of NLRP3 (NOD-like receptor protein 3) inflammasome. Teneligliptin reversal markedly increased cardiomyocyte area and heart weight/tibia length, reduced fractional shortening, ejection fraction, and heart rate, increased creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), aspartate transaminase (AST), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, and upregulated NADPH oxidase 4 in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Teneligliptin repressed activated NLRP3 inflammasome and increased CK-MB, AST, and LDH levels in glucose-stimulated cardiomyocytes, accompanied by an upregulation of phosphorylated-adenosine 5‘-monophosphate and activated protein kinase.

INTRODUCTION

With the rapid development of international society and the economy, living standards have improved qualitatively. However, the prevalence of diseases has greatly increased, and diabetes mellitus (DM) is common. According to the International Diabetes Federation, there are 8.75 million people with type 1 diabetes (T1D) worldwide, or 0.11% of the global population. 1.52 million (17.0%) patients were younger than 20 years of age, 5.56 million (64.0%) patients were between 20 and 59 years of age, and 1.67 million (19.9%) patients were 60 years of age or older. In 2022, there will be 530000 newly diagnosed cases of T1D in all age groups, of which 200000 will be under 20 years old[1], posing a threat to public health. As a complication of DM, diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a condition in which the heart has abnormal myocardial structure and function in the absence of coronary artery disease, severe valvular lesions, or other conventional cardiovascular factors. DCM is characterized by lipid accumulation in the heart, myocardial fibrosis, and an increased probability of myocardial cell death, leading to left ventricular remodeling, hypertrophy, and diastolic dysfunction, which, in turn, contributes to systolic dysfunction[2]. The pathophysiological mechanism of DCM is related to an abnormal glucose supply and lipid metabolism owing to increased oxidative stress (OS), cellular activation regulated by multiple inflammatory pathways, extracellular damage, pathological cardiac remodeling, and diastolic and systolic dysfunction induced by DM[3]. NLRP3 (NOD-like receptor protein 3) is an inflammasome found in both immune and nonimmune cells, such as macrophages, cardiomyocytes, and fibroblasts. NLRP3 is upregulated in multiple diseases, including DCM and atherosclerosis[4]. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome has been shown to participate in DCM and the death of cardiomyocytes. In response to a variety of pathological factors, the NLRP3 inflammasome, and the expression of downstream cytokines are triggered, leading to a cascade of inflammatory reactions and causing damage to myocardial cells[5]. Furthermore, NLRP3 activation correlates with reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Under high glucose conditions, ROS levels are elevated, which is important for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. In addition, ROS activate the NLRP3 inflammasome mainly by forcing cytochrome C to enter the cytoplasm and bind to NLRP3. NLRP3 is inactivated by inhibiting ROS production, which alleviates hyperglycaemia-induced myocardial cell damage[6]. Therefore, NLRP3 is a critical target for treating DCM.

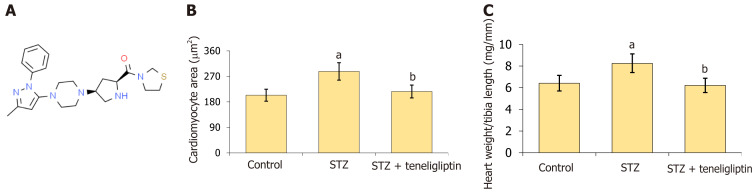

Teneligliptin (Figure 1A) is an oral hypoglycemic dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitor developed by Mitsubishi Pharmaceutical Company in Japan that is mainly used to treat type II diabetes. By suppressing the inactivation of glucagon-like peptide in vivo by selectively inhibiting the activity of DPP-IV, teneligliptin promotes the production of insulin by islet cells and reduces the concentration of glucagon, thereby reducing blood glucose. Teneligliptin is well tolerated and has a low incidence of adverse reactions[7,8]. Recently, teneligliptin was shown to have a promising suppressive effect on inflammation[9] and OS[10]. Teneligliptin has been used to treat T2DM patients with renal impairment, including those with end-stage renal disease. Moreover, teneligliptin has cytoprotective effects on myocardial cells[11]. Our study examined the possible therapeutic effectiveness of teneligliptin in DCM in diabetic mice.

Figure 1.

Teneligliptin ameliorated myocardial hypertrophy in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. A: Molecular structure of teneligliptin; B: Quantitative analysis of cardiomyocyte area; C: Heart weight/tibia length. aP < 0.05 vs control group; bP < 0.05 vs streptozotocin group, n = 8. STZ: Streptozotocin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal experiments

The streptozotocin (STZ) solution (S0130; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, United States) was prepared with citric acid/sodium citrate buffer, and 55 mg/kg STZ was administered to C57BL/6 male mice by intraperitoneal injection for 5 consecutive days. One week later, blood was collected from the tail vein and fasting blood glucose levels were detected by a Roche blood glucose meter. The mouse model of DCM was considered successfully constructed if the fasting blood glucose level was higher than 16.7 mmol/L. The mice were divided into three groups: Vehicle, STZ, and teneligliptin (SML3077; Sigma-Aldrich). In the vehicle and STZ groups, normal mice and diabetic mice received oral doses of normal saline. In the teneligliptin group, diabetic mice were orally administered 30 mg/kg teneligliptin for 4 wk. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiangxi Provincial People's Hospital.

Measurement of heart function

The mice were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital to maintain a heart rate of approximately 300 beats/min and then placed on a thermostatic heating plate connected to a high-resolution small animal ultrasonic apparatus (VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada). The following parameters were recorded: End-systolic diameter (ESD) and end-systolic volume (ESV), end-diastolic diameter (EDD) and end-diastolic volume (EDV), and heart rate. Fractional shortening was calculated as (EDD-ESD)/EDD × 100%, and the ejection fraction was calculated as (EDV-ESV)/EDV × 100%.

Detection of myocardial injury indicators and interleukin-1β

The levels of creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), aspartate transaminase (AST), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and interleukin (IL)-1β were detected by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, United States). The supernatant was collected and added to a 96-well plate and the standards were added. After incubation for 1.5 h, the conjugate solution was added to the wells, after which the plates were incubated for another 1.5 h. Next, tetramethylbenzidine solution (861510; Sigma-Aldrich) was added, followed by a 15 m of incubation. Finally, the stop solution was added to stop the reaction, after which the optical density was detected with a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, United States) at 450 nm.

HE staining

The collected myocardium was rinsed with water for 2 h. After being dehydrated with different concentrations of ethanol, the tissues were dehydrated with xylene until transparent, embedded for 1 h and then sliced. After being heated, dewaxed, and hydrated, the sections were immersed in water and subsequently stained with hematoxylin aqueous reagent for 2–3 min. After being differentiated in hydrochloric acid ethanol, the sections were stained with the blue-returning reagent for several seconds. After being stained with eosin for 180 s, images were obtained using an inverted microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from tissues or cells with TRIzol reagent, after which the RNA concentration was quantified with an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (Hach, Loveland CO, United States). RNA was transcribed to cDNA using a cDNA synthesis kit (SolelyBio, China). Subsequently, PCR was performed by using an SYBR Premix Ex TaqII kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan), and gene expression was determined by using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Western blot analysis

Tissues or cells were lysed to extract total proteins, followed by quantification using the bicinchoninic acid assay method. The proteins were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred to PVDF membranes. After the membranes were blocked, primary antibodies against NADPH oxidase 4 (1:2000, 14347-1-AP; Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, United States), NLRP3 (1:2000, 14347-1-AP; Proteintech), caspase-1 (1:2000, 22915-1-AP; Proteintech), p-AMPK (1:1000, 4186; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, United States), and β-actin (4970; Cell Signaling Technology) were used. Then, secondary antibodies (1:2000, 7074, 7076; Cell Signaling Technology) were added. The bands were visualized with en-hanced chemiluminescence solution for quantification.

Primary cardiomyocyte culture

Immature mice (0–2 d of age) were disinfected by immersion in 75% alcohol for 1–2 m. Then, a small incision was made under the sternum with sterilized ophthalmic scissors, after which the heart was collected and was placed in a Petri dish with precooled Hanks solution. The heart was then cut into 1 mm–3 mm pieces with scissors on an ultraclean table, followed by the addition of 7 mL of 0.1% type II collagenase. The rubber plug was blocked, the sealing membrane was added, and cells were then placed in a 37 °C incubator for 10 m until the cells naturally precipitated. The supernatant was discarded, and the digestion was terminated by gently mixing the solution approximately 60 times with a pipettor for 15 m. Then, the cell suspension was transferred to high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium. The cell suspension obtained from each digestion was mixed until the tissue block was completely digested. The supernatant was discarded after being centrifuged at 1000 × rpm for 10 m, and an appropriate amount of complete medium was subsequently mixed with a 100 μm nylon screen and inoculated into the culture flask, which was subsequently cultured at 37 °C in a 5% carbon dioxide incubator. After 90 m, the supernatant was mostly purified, and the cardiomyocytes were transferred to another culture flask for further culture.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± SD and were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with GraphPad Prism software 6.0 (La Jolla, CA, United States). P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

RESULTS

Teneligliptin ameliorated myocardial hypertrophy in STZ-induced diabetic mice

WGA staining was used to detect myocardial hypertrophy. Cardiomyocyte area in STZ-treated mice increased from 203.6 μm2 to 287.5 μm2 and was markedly reduced to 216.7 μm2 by teneligliptin (Figure 1B). Moreover, the heart weight/tibia length in STZ-treated mice increased from 6.4 mg/mm to 8.3 mg/mm and was decreased to 6.2 mg/mm by teneligliptin (Figure 1C). Moreover, teneligliptin alleviated myocardial hypertrophy.

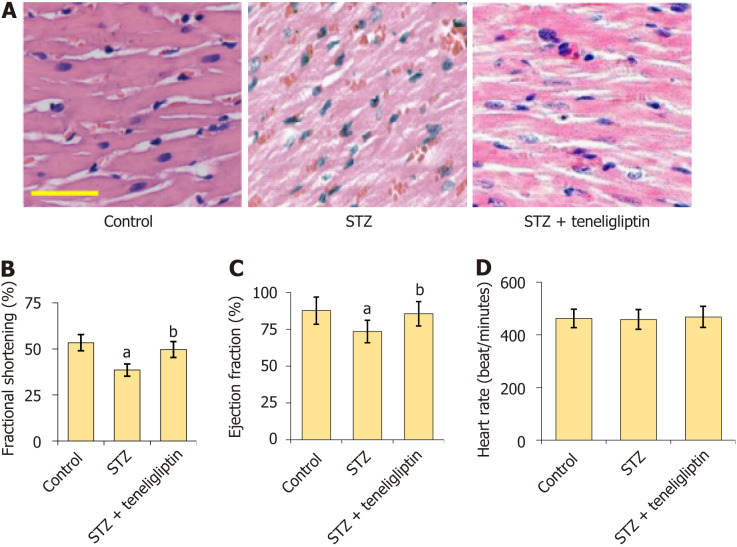

Teneligliptin improved heart function in STZ-induced diabetic mice

HE staining (Figure 2A) showed that myocardial cells in the vehicle group had a normal morphology, complete structure, dense and regular arrangement, and uniform distribution of nuclei. However, myocardial cells in diabetic mice were hypertrophic with a fuzzy structure, disordered arrangement, and some fiber breakage. The morphological structures of myocardial cells in the teneligliptin group were neat with relatively regular arrangements and improvements in hypertrophy and fiber breakage. The fractional shortening of diabetic mice decreased from 53.5% to 38.7% and was markedly increased to 49.6% by teneligliptin (Figure 2B). Furthermore, the ejection fractions in the vehicle, STZ, and teneligliptin groups were 87.6%, 73.5%, and 85.5%, respectively (Figure 2C). The heart rates of the diabetic mice decreased from 462.5 beats/min to 458.7 beats/minute and then increased to 468.3 beats/min in response to teneligliptin (Figure 2D). The heart function of diabetic mice was improved by teneligliptin.

Figure 2.

Teneligliptin improved heart function in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. A: The results of HE staining, Scale bar = 50 µm; B-D: Mice heart fractional shortening, ejection fraction, and heart rate was measured by echo. aP < 0.05 vs control group; bP < 0.05 vs streptozotocin group, n = 8. STZ: Streptozotocin.

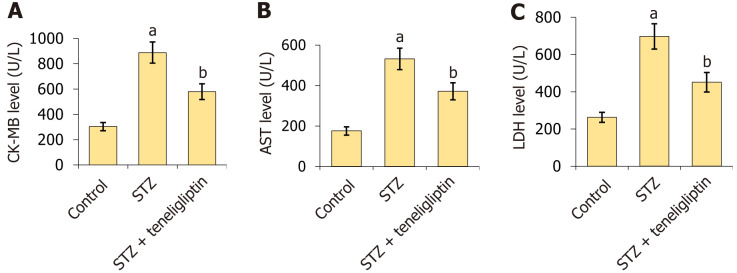

Teneligliptin reduced the expression of myocardial injury indicators in STZ-induced diabetic mice

CK-MB levels in diabetic mice increased from 303.5 U/L to 888.8 U/L but were markedly reduced to 578.8 U/L by teneligliptin (Figure 3A). Moreover, AST levels in the vehicle, STZ, and teneligliptin groups were 176.3, 522.6, and 371.8 U/L, respectively (Figure 3B). LDH levels in diabetic mice increased from 262.7 U/L to 697.5 U/L and then decreased to 451.2 U/L in response to teneligliptin (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Teneligliptin reduced the expression of the myocardial injury indicators in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. A: Creatine kinase-MB level; B: The aspartate transaminase level; C: The lactate dehydrogenase level. aP < 0.05 vs control group; bP < 0.05 vs streptozotocin group, n = 8. STZ: Streptozotocin; CK-MB: Creatine kinase-MB; AST: Aspartate transaminase; LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase.

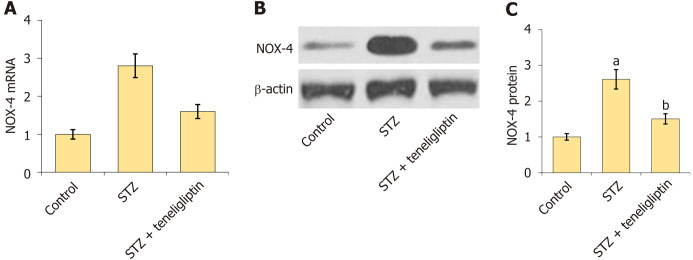

Teneligliptin reduced NOX4 levels in diabetic mice

NOX4 is a critical pathological factor in DCM[12]. The increase in NOX4 levels in diabetic mice was markedly inhibited by teneligliptin (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Teneligliptin reduced the expression of NOX4 in diabetic mice. A: mRNA of NOX-4; B: Protein of NOX-4; C: Quantitative analysis of protein expression levels for panel B. aP < 0.05 vs control group; bP < 0.05 vs streptozotocin group, n = 8. STZ: Streptozotocin.

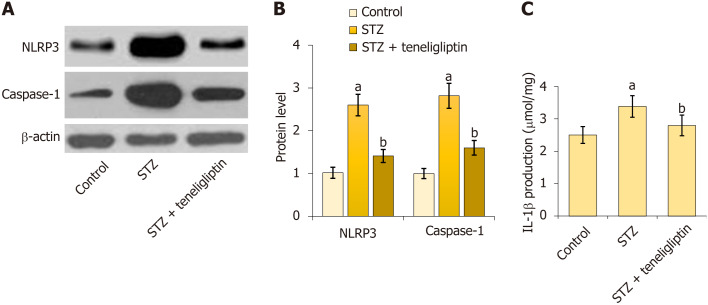

Teneligliptin reduced activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the heart in diabetic mice

First, NLRP3 and caspase-1 were notably upregulated in diabetic mice but markedly decreased by teneligliptin (Figure 5A and B). Moreover, IL-1β levels in diabetic mice increased from 2.5 μmol/mg to 3.4 μmol/mg protein and then decreased to 2.8 μmol/mg protein in response to teneligliptin (Figure 5C). The suppressive effect of teneligliptin on the NLRP3 inflammasome in the heart was observed.

Figure 5.

Teneligliptin reduced activation of the cardiac NLRP3 inflammasome in the control and diabetic mice. A: NLRP3 and caspase-1 measured by Western blot assays; B: Quantitative analysis of protein expression levels for panel A; C: Production of interleukin-1β as measured by ELISA. aP < 0.05 vs control group; bP < 0.05 vs streptozotocin group, n = 8. STZ: Streptozotocin.

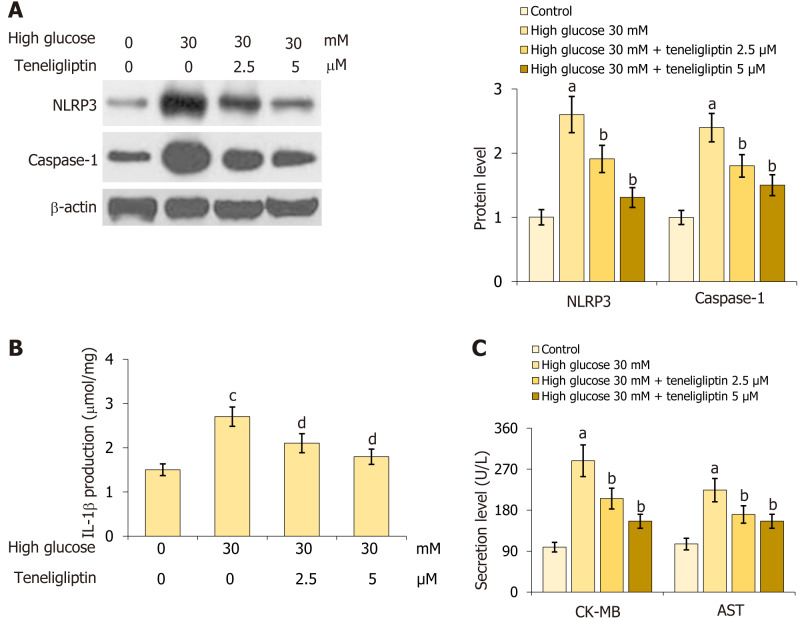

Teneligliptin prevented activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the heart and injury in cardiomyocytes

Primary mouse cardiomyocytes were extracted and treated with high glucose (30 mmol/L) with or without teneligliptin (2.5, 5 µM) for 24 h. NLRP3 and caspase-1 Levels in cardiomyocytes were markedly increased by 30 mmol/L glucose but were inhibited by 2.5 and 5 µM teneligliptin (Figure 6A). Moreover, IL-1β levels in the control, high glucose, 2.5 µM teneligliptin, and 5 µM teneligliptin groups were 1.5, 2.7, 2.1, and 1.8 μmol/mg protein, respectively (Figure 6B). CK-MB levels increased from 98.8 U/L to 288.5 U/L in 30 mmol/L glucose-treated cardiomyocytes and then decreased to 205.6 and 155.7 U/L in response to 2.5 and 5 µM teneligliptin, respectively. Furthermore, AST levels in the control, high glucose, 2.5 µM teneligliptin, and 5 µM teneligliptin groups were 105.6, 223.9, 170.5, and 146.6 U/L, respectively (Figure 6C). The suppressive effect of teneligliptin on the NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiomyocytes was observed.

Figure 6.

Teneligliptin prevented activation of the cardiac NLRP3 inflammasome and injury in cardiomyocytes. Primary cardiomyocytes were treated with high glucose (30 mmol/L) with or without teneligliptin (2.5 or 5 µM) for 24 h. A: Expression of NLRP3 and caspase-1 were measured by western blot assays; B: Levels of IL-1β as measured by ELISA; C: Levels of creatine kinase-MB and aspartate transaminase level. aP < 0.05 vs control group; bP < 0.05 vs high glucose 30 mmol/L group; cP < 0.05 vs high glucose 0 mmol/L + teneligliptin 0 µM group; dP < 0.05 vs high glucose 30 mmol/L + teneligliptin 0 µM group, n = 5. CK-MB: Creatine kinase-MB; AST: Aspartate transaminase; IL: Interleukin.

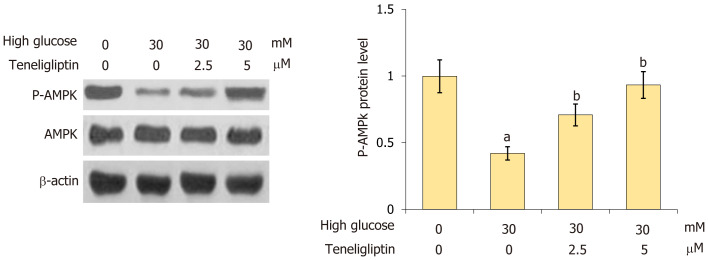

Treatment with teneligliptin increased the phosphorylation of AMPK in cardiomyocytes under high glucose conditions

AMPK signaling reportedly regulates the NLRP3 inflammasome[13]. The decrease in p-AMPK in cardiomyocytes was reversed by 30 mmol/L glucose and this effect was markedly reversed by 2.5 and 5 µM teneligliptin (Figure 7), suggesting that teneligliptin affected AMPK signaling.

Figure 7.

Teneligliptin increased the phosphorylation of AMPK against high glucose in cardiomyocytes. Primary cardiomyocytes were treated with high glucose (30 mmol/L) with or without teneligliptin (2.5 or 5 µM) for 24 h. Levels of p-AMPK were measured by western blot assays. aP < 0.05 vs control group; bP < 0.05 vs high glucose 30 mmol/L + teneligliptin 0 µM group, n = 5.

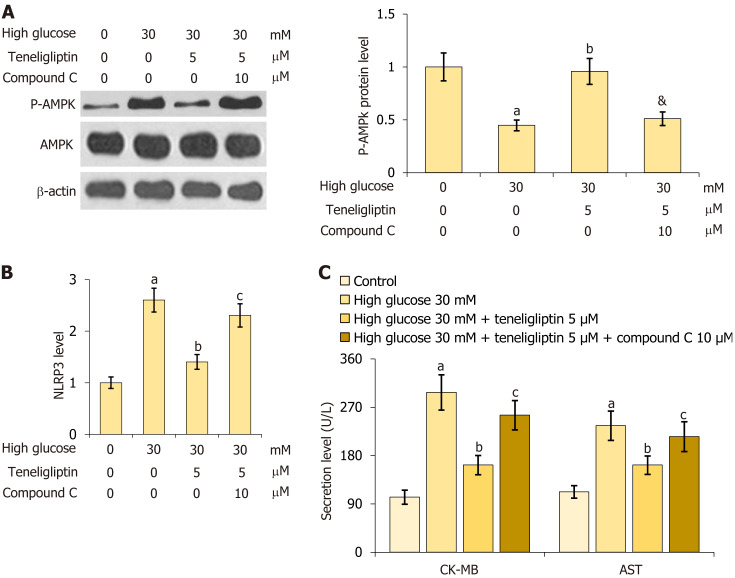

Inhibiting AMPK abolished the beneficial effects of teneligliptin on hyperglycaemia-induced cardiomyocytes

For verification, primary mouse cardiomyocytes were treated with high glucose (30 mmol/L) with or without teneligliptin (5 µM) and in the presence or absence of compound C (10 μM) for 24 h. First, the reduction in p-AMPK in 30 mmol/L glucose-treated cardiomyocytes was notably attenuated by teneligliptin, and this effect was reversed by compound C (Figure 8A). Furthermore, the increase in NLRP3 observed in 30 mmol/L glucose-treated cardiomyocytes was strongly reduced by teneligliptin but was elevated by compound C (Figure 8B). Moreover, CK-MB levels increased from 102.5 U/L to 297.6 U/L in 30 mmol/L glucose-treated cardiomyocytes and then greatly decreased to 162.3 U/L in response to teneligliptin. After the administration of compound C, CK-MB levels were reversed to 255.2 U/L. AST levels in the control, high glucose, teneligliptin, and teneligliptin+ compound C groups were 112.3, 235.6, 155.3, and 215.3 U/L, respectively (Figure 8C). The beneficial effects of teneligliptin on hyperglycaemia-induced cardiomyocytes were abolished by AMPK inhibition.

Figure 8.

Inhibition of AMPK abolished the beneficial effects of teneligliptin against high glucose in cardiomyocytes. Primary cardiomyocytes were treated with high glucose (30 mmol/L) with or without teneligliptin (5 µM) and compound C (10 μM). A: Levels of p-AMPK; B: The levels of NLRP3; C: Levels of creatine kinase-MB and aspartate transaminase level. aP < 0.05 vs control group; bP < 0.05 vs high glucose 30 mmol/L group; cP < 0.05 vs high glucose 30 mmol/L + teneligliptin 5 µM group, n = 5.

DISCUSSION

Studies have shown that NLRP3 is activated during DCM development through the inflammatory response and that teneligliptin exerts anti-inflammatory and protective effects in myocardial cells. In this study, we established an STZ-induced diabetes model and found that teneligliptin significantly inhibited cardiac hypertrophy and reduced fractional shortening and the ejection fraction induced by diabetes. Additionally, teneligliptin significantly reversed diabetes-induced increases in CK-MB, AST, and LDH. In addition, activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and the increased release of IL-1β in diabetic mice were inhibited by teneligliptin, which was accompanied by the upregulation of p-AMPK. The same results were obtained in primary mouse cardiomyocytes treated with high glucose.

Teneligliptin is a low-cost oral hypoglycemic dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitor that is used for diabetes treatment. Singh et al[14] searched 13 eligible studies containing data on 15720 subjects and showed similar efficacy (or better) and safety of teneligliptin compared with other DPP4Is. The average cost per tablet of teneligliptin (20 mg) was markedly lower than that of sitagliptin, vildagliptin, or other commonly used DPP4Is. Teneligliptin has various effects on both cardiovascular disease and other disorders. Teneligliptin can improve vascular endothelial function by improving flow-mediated vascular dilatation through divergent actions, including changes in circulating endothelial progenitor cells[15]. Teneligliptin-induced vasodilation occurs via the activation of protein kinase G, SERCA pumps and protein kinase G channels[16]. A systematic review of 13 randomized controlled trials that enrolled 2853 patients showed that teneligliptin was an effective and safe therapeutic option for patients with T2DM as a monotherapy and add-on therapy[17].

Teneligliptin has recently been reported to have anti-inflammatory and protective effects on myocardial cells, and DPP4 inhibitors have been reported to be associated with mitochondrial metabolism. Notably, teneligliptin enhances SIRT1 protein expression and activity through USP22, a ubiquitin-specific peptidase. Activated SIRT1 prevents hyperglycaemia-induced PRDX3 acetylation by SIRT3, resulting in the inhibition of PRDX3 hyperoxidation and thereby enhancing mitochondrial antioxidant defense[18]. In rat cardiac microvascular endothelial cells, teneligliptin significantly ameliorated the reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential induced by hypoxia/reoxygenation, indicating that teneligliptin could affect mitochondrial function[19]. In 5/6-nephrectomized mice, indoxyl sulfate induced mitochondrial dysfunction by decreasing the expression of PGC-1α and inducing autophagy, as well as decreasing the mitochondrial membrane potential, and teneligliptin reversed this effect[20]. In summary, although teneligliptin has been reported to have anti-inflammatory and protective effects on myocardial cells, future studies should focus on its ability to improve mitochondrial metabolism.

NLRP3 is a NOD-like receptor sensor molecule[21] that belongs to the cytoplasmic NOD family of pattern recognition receptors. After being activated, NLRP3 undergoes self-oligomerization and assembles with ASC and the protease caspase-1 to form the NLRP3 inflammasome. This process results in the production of the active form of the caspase-1 p10/p20 splicer and induces the conversion of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 from their immature forms to their active forms, inducing an inflammatory response[22]. The NLRP3 inflammasome triggers a form of cell death known as pyroptosis. NLRP3 activation triggers the autocatalytic activation of caspase-1, which drives the cleavage of the gasdermin D protein to produce N'-segment protein fragments that bind to phospholipid proteins on the cell membrane, form holes, and release inflammatory factors. Subsequently, cells continue to expand until the membrane ruptures, which is the process of pyroptosis[23]. NLRP3 inhibition improves insulin sensitivity in obese mice, suggesting that NLRP3 may participate in metabolism-related diseases such as diabetes[24]. In addition, hyperglycemia reportedly activates NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis in myocardial cells, and knocking down NLRP3 in DCM rats reduces the inflammatory response in myocardial tissues, inhibits the occurrence of myocardial pyroptosis and myocardial interstitial fibrosis, and improves cardiac function[25,26]. These findings suggest that the NLRP3 inflammasome is involved in DCM development. In our study, DCM model mice were generated by STZ injection, and the results were verified by assessing myocardial hypertrophy, impaired heart function, and myocardial injury indicator production; these findings were consistent with previous studies[27,28]. Following the administration of teneligliptin, myocardial hypertrophy was alleviated, heart function was improved, and myocardial injury indices were reduced, suggesting that teneligliptin alleviated DCM in mice. Moreover, the NLRP3 inflammasome was activated in both DCM mice and primary mouse cardiomyocytes stimulated with 30 mmol/L glucose, which is consistent with the findings of Song et al[29] and Shi et al[30]. Following the administration of teneligliptin, NLRP3 inflammasome activity was inhibited in both DCM mice and primary mouse cardiomyocytes stimulated with 30 mmol/L glucose, suggesting that the effect of teneligliptin might be mediated by inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

This study showed that teneligliptin improved cardiac function in DCM in vivo and in vitro and exerted its effect through NLRP3. One shortcoming of this study is that the direct effect of NLRP3 was not verified by knocking down or overexpressing NLRP3. In addition, the effect of teneligliptin on NLRP3-induced autophagy will be examined in future studies.

AMPK regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation through multiple pathways, such as mitochondrial homeostasis, endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, and SIRT1 activation. p-AMPK/AMPK is an important sensor molecule that regulates bioenergy homeostasis and reduces the activation of NF-κB to control the inflammatory response mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome[31]. A previous study showed that autophagy was induced, mitochondrial ROS production was reduced, and IL-1β secretion was inhibited by mTOR inhibitors[32]. Autophagy is facilitated by AMPK through the activation of ULK or inhibition of the mTOR pathway. Furthermore, NLRP3 inflammasome activity is negatively regulated by autophagy through different mechanisms[33]. In our study, AMPK signaling was inhibited in primary mouse cardiomyocytes stimulated with 30 mmol/L glucose, which is consistent with the findings of Yang et al[13]. The suppressive effect of 30 mmol/L glucose on AMPK signaling was reversed by teneligliptin, suggesting that the AMPK pathway mediates the effects of teneligliptin. Moreover, the beneficial effects of teneligliptin on hyperglycaemia-induced cardiomyocytes were abolished by inhibiting AMPK, suggesting that the regulatory effect of teneligliptin on DCM was controlled by AMPK. In the future, the exact mechanism will be identified by treating diabetic mice with teneligliptin plus compound C. This study limitation study should be mentioned. The study did not determine how teneligliptin interfered with AMPK/NLRP3 signaling in cardiomyocytes. It has been reported that NLRP3 plays an important role in cardiomyocyte pyroptosis during DCM. Future studies will further explore the effect of teneligliptin on cardiomyocyte pyroptosis during DCM. LCZ696 is a dual inhibitor of the AT1 receptor and of neprilysin signaling, and it remains unclear whether the effect of LCZ696 is dependent on these two pathways. The role of neprilysin in endothelial cells is not well known.

In summary, in this study, we established an STZ-induced diabetes model and found that teneligliptin significantly inhibited cardiac hypertrophy and reduced fractional shortening and the ejection fraction induced by diabetes. Through animal in vivo and cell in vitro experiments, we found that teneligliptin can improve DCM through NLRP3 pathway, which take to us that cell pyroptosis plays an important role in the improvement of DCM by treatment with teneligliptin. Future study should performed by NLPR3 knocking down and overexpressing to verified its direct effect, which is the main limitations of this study.

CONCLUSION

Overall, teneligliptin mitigated DCM by mitigating activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, which suggests that in future clinical work, teneligliptin may treat diseases involving the NLRP3 pathway.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM), which is a complication of diabetes, poses a great threat to public health. Recent studies have confirmed the role of NLRP3 (NOD-like receptor protein 3) activation in DCM development through the inflammatory response. Teneligliptin is an oral hypoglycemic dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitor used to treat diabetes. Teneligliptin has recently been reported to have anti-inflammatory and protective effects on myocardial cells.

Research motivation

This study examined the therapeutic effects of teneligliptin on DCM in diabetic mice.

Research objectives

Teneligliptin improves DCM by means of NLRP3, providing a new target for teneligliptin in the treatment of DCM.

Research methods

Streptozotocin (STZ) was administered to induce diabetes in mice, followed by treatment with 30 mg/kg teneligliptin. Small animal ultrasonic apparatus was used to measure mice heart function, The levels of creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), aspartate transaminase (AST), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and interleukin (IL)-1β were detected by ELISA, cardiomyocytes areas were measured by HE staining, Real-time PCR was used to measure NOX-4 mRNA expression, western blot was used to measure NOX-4, NLRP3, caspase-1, AMPK, p-AMPK protein expression level, primary cardiomyocytes was isolated in neonatal mice. The data are presented as the mean ± SD and were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with GraphPad Prism software 6.0. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Research results

Marked increases in cardiomyocyte area and heart weight/tibia length; reductions in fractional shortening, ejection fraction, and heart rate; increases in CK-MB, AST, and LDH levels; and upregulated NADPH oxidase 4 were observed in diabetic mice, all of which were significantly reversed by teneligliptin. Moreover, NLRP3 inflammasome activation and increased release of IL-1β in diabetic mice were inhibited by teneligliptin. Primary mouse cardiomyocytes were treated with high glucose (30 mmol/L) with or without teneligliptin (2.5 or 5 µM) for 24 h. NLRP3 inflammasome activation and the increases in CK-MB, AST, and LDH levels in glucose-stimulated cardiomyocytes were markedly inhibited by teneligliptin, and AMP (p-adenosine 5‘-monophosphate)-p-AMPK (activated protein kinase) levels were increased. Furthermore, the beneficial effects of teneligliptin on hyperglycaemia-induced cardiomyocytes were abolished by the AMPK signaling inhibitor compound C.

Research conclusions

Overall, teneligliptin mitigated DCM by mitigating activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Research perspectives

Our study suggests that in future clinical work, teneligliptin may treat diseases involving the NLRP3 pathway.

Footnotes

Institutional animal care and use committee statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Jiangxi Provincial People's Hospital Institutional Review Board (Approval No. KT089).

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the Authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

ARRIVE guidelines statement: The authors have read the ARRIVE Guidelines, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the ARRIVE Guidelines.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: October 8, 2023

First decision: December 6, 2023

Article in press: February 27, 2024

Specialty type: Endocrinology and metabolism

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Pappachan JM, United Kingdom; Soriano-Ursúa MA, Mexico S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhang YL

Contributor Information

Gu-Lao Zhang, Department of Cardiology, Jiangxi Provincial People's Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang Medical College, Nanchang 330000, Jiangxi Province, China.

Yuan Liu, Department of Cardiology, Jiangxi Provincial People's Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang Medical College, Nanchang 330000, Jiangxi Province, China.

Yan-Feng Liu, Department of Cardiology, Jiangxi Provincial People's Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang Medical College, Nanchang 330000, Jiangxi Province, China.

Xian-Tao Huang, Department of Cardiology, Jiangxi Provincial People's Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang Medical College, Nanchang 330000, Jiangxi Province, China.

Yu Tao, Department of Cardiology, Jiangxi Provincial People's Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang Medical College, Nanchang 330000, Jiangxi Province, China.

Zhen-Huan Chen, Department of Cardiology, Jiangxi Provincial People's Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang Medical College, Nanchang 330000, Jiangxi Province, China.

Heng-Li Lai, Department of Cardiology, Jiangxi Provincial People's Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang Medical College, Nanchang 330000, Jiangxi Province, China. laihengli@163.com.

Data sharing statement

The data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, Stein C, Basit A, Chan JCN, Claude Mbanya J, Pavkov ME, Ramachandaran A, Wild SH, James S, Herman WH, Zhang P, Bommer C, Kuo S, Boyko EJ, Magliano DJ. Erratum to "IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045" [Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 183 (2022) 109119] Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2023;204:110945. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2023.110945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Japp AG, Gulati A, Cook SA, Cowie MR, Prasad SK. The Diagnosis and Evaluation of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2996–3010. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan Y, Zhang Z, Zheng C, Wintergerst KA, Keller BB, Cai L. Mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy and potential therapeutic strategies: preclinical and clinical evidence. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:585–607. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0339-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng C, Duan F, Hu J, Luo B, Huang B, Lou X, Sun X, Li H, Zhang X, Yin S, Tan H. NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis contributes to the pathogenesis of non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Redox Biol. 2020;34:101523. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng Y, Xu L, Dong N, Li F. NLRP3 inflammasome: The rising star in cardiovascular diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:927061. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.927061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang H, Chen X, Zong B, Yuan H, Wang Z, Wei Y, Wang X, Liu G, Zhang J, Li S, Cheng G, Wang Y, Ma Y. Gypenosides improve diabetic cardiomyopathy by inhibiting ROS-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:4437–4448. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott LJ. Teneligliptin: a review in type 2 diabetes. Clin Drug Investig. 2015;35:765–772. doi: 10.1007/s40261-015-0348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma SK, Panneerselvam A, Singh KP, Parmar G, Gadge P, Swami OC. Teneligliptin in management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2016;9:251–260. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S106133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X, Cao Y, Zhang Y, Sun B, Liang H. Teneligliptin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced cytotoxicity and inflammation in dental pulp cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;73:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sagara M, Suzuki K, Aoki C, Tanaka S, Taguchi I, Inoue T, Aso Y. Impact of teneligliptin on oxidative stress and endothelial function in type 2 diabetes patients with chronic kidney disease: a case-control study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:76. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0396-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng W, Rao D, Zhang M, Shi Y, Wu J, Nie G, Xia Q. Teneligliptin prevents doxorubicin-induced inflammation and apoptosis in H9c2 cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2020;683:108238. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2019.108238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan L, Xiao Q, Zhang L, Wang X, Huang Q, Li S, Zhao X, Li Z. CAPE-pNO(2) attenuates diabetic cardiomyopathy through the NOX4/NF-κB pathway in STZ-induced diabetic mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;108:1640–1650. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang F, Qin Y, Wang Y, Meng S, Xian H, Che H, Lv J, Li Y, Yu Y, Bai Y, Wang L. Metformin Inhibits the NLRP3 Inflammasome via AMPK/mTOR-dependent Effects in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:1010–1019. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.29680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh H, Arora E, Narula S, Singla M, Otaal A, Sharma J. Finding the most cost-effective option from commonly used Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in India: a systematic study. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2023;18:347–354. doi: 10.1080/17446651.2023.2216279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akashi N, Umemoto T, Yamada H, Fujiwara T, Yamamoto K, Taniguchi Y, Sakakura K, Wada H, Momomura SI, Fujita H. Teneligliptin, a DPP-4 Inhibitor, Improves Vascular Endothelial Function via Divergent Actions Including Changes in Circulating Endothelial Progenitor Cells. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2023;16:1043–1054. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S403125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, An JR, Park M, Choi J, Heo R, Kang M, Mun SY, Zhuang W, Seo MS, Han ET, Han JH, Chun W, Park WS. The antidiabetic drug teneligliptin induces vasodilation via activation of PKG, Kv channels, and SERCA pumps in aortic smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol. 2022;935:175305. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2022.175305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelluri R, Kongara S, Nagasubramanian VR, Mahadevan S, Chimakurthy J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of teneligliptin for treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Endocrinol Invest. 2023;46:855–867. doi: 10.1007/s40618-023-02003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elumalai S, Karunakaran U, Moon JS, Won KC. High glucose-induced PRDX3 acetylation contributes to glucotoxicity in pancreatic β-cells: Prevention by Teneligliptin. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;160:618–629. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Z, Jin X, Yang C, Li Y. Teneligliptin protects against hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced endothelial cell injury. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enoki Y, Watanabe H, Arake R, Fujimura R, Ishiodori K, Imafuku T, Nishida K, Sugimoto R, Nagao S, Miyamura S, Ishima Y, Tanaka M, Matsushita K, Komaba H, Fukagawa M, Otagiri M, Maruyama T. Potential therapeutic interventions for chronic kidney disease-associated sarcopenia via indoxyl sulfate-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017;8:735–747. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoue M, Shinohara ML. The role of interferon-β in the treatment of multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis - in the perspective of inflammasomes. Immunology. 2013;139:11–18. doi: 10.1111/imm.12081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swanson KV, Deng M, Ting JP. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:477–489. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0165-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mangan MSJ, Olhava EJ, Roush WR, Seidel HM, Glick GD, Latz E. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:688. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shao BZ, Xu ZQ, Han BZ, Su DF, Liu C. NLRP3 inflammasome and its inhibitors: a review. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:262. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo B, Huang F, Liu Y, Liang Y, Wei Z, Ke H, Zeng Z, Huang W, He Y. NLRP3 Inflammasome as a Molecular Marker in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Front Physiol. 2017;8:519. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frangogiannis NG. The Extracellular Matrix in Ischemic and Nonischemic Heart Failure. Circ Res. 2019;125:117–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.311148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tong M, Saito T, Zhai P, Oka SI, Mizushima W, Nakamura M, Ikeda S, Shirakabe A, Sadoshima J. Mitophagy Is Essential for Maintaining Cardiac Function During High Fat Diet-Induced Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2019;124:1360–1371. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arow M, Waldman M, Yadin D, Nudelman V, Shainberg A, Abraham NG, Freimark D, Kornowski R, Aravot D, Hochhauser E, Arad M. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor Dapagliflozin attenuates diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:7. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0980-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song S, Ding Y, Dai GL, Zhang Y, Xu MT, Shen JR, Chen TT, Chen Y, Meng GL. Sirtuin 3 deficiency exacerbates diabetic cardiomyopathy via necroptosis enhancement and NLRP3 activation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2021;42:230–241. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0490-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi C, Wu L, Li L. LncRNA-MALAT 1 regulates cardiomyocyte scorching in diabetic cardiomyopathy by targeting NLRP3. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2022;67:213–219. doi: 10.14715/cmb/2021.67.6.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cordero MD, Williams MR, Ryffel B. AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Regulation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome during Aging. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018;29:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen-Scarabelli C, Agrawal PR, Saravolatz L, Abuniat C, Scarabelli G, Stephanou A, Loomba L, Narula J, Scarabelli TM, Knight R. The role and modulation of autophagy in experimental models of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2014;11:338–348. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong Y, Chen H, Gao J, Liu Y, Li J, Wang J. Molecular machinery and interplay of apoptosis and autophagy in coronary heart disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2019;136:27–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available on reasonable request.