Abstract

Objectives

To determine the prevalence of multiple long-term conditions (MLTC) at whole English population level, stratifying by age, sex, socioeconomic status and ethnicity.

Design

A whole population study.

Setting

Individuals registered with a general practice in England and alive on 31 March 2020.

Participants

60,004,883 individuals.

Main outcome measures

MLTC prevalence, defined as two or more of 35 conditions derived from a number of national patient-level datasets. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the independent associations of age, sex, ethnicity and deprivation decile with odds of MLTC.

Results

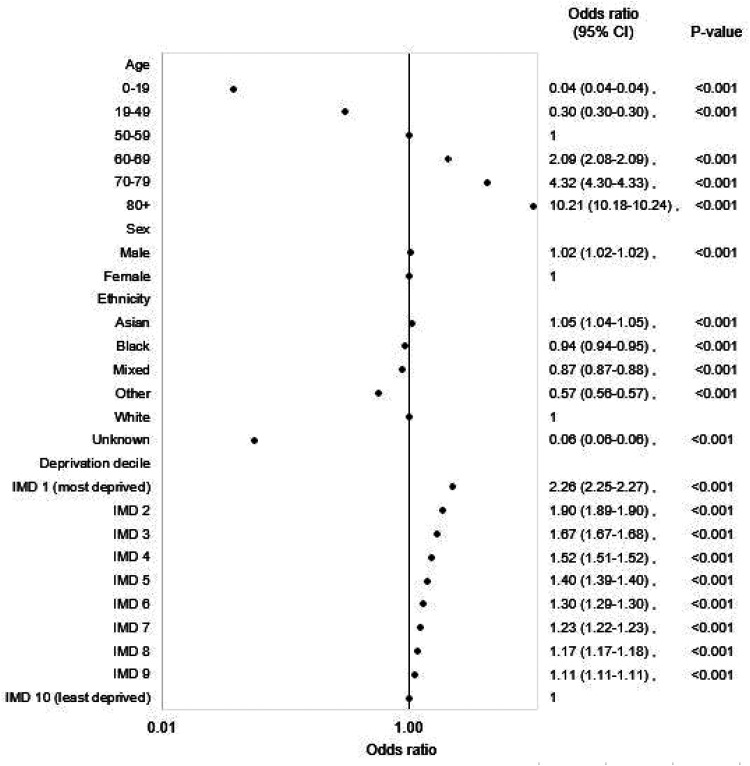

The overall prevalence of MLTC was 14.8% (8,878,231), varying from 0.9% (125,159) in those aged 0–19 years to 68.2% (1,905,979) in those aged 80 years and over. In multivariable regression analyses, compared with the 50–59 reference group, the odds ratio was 0.04 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.04–0.04; p < 0.001) for those aged 0–19 years and 10.21 (10.18–10.24; p < 0.001) for those aged 80 years and over. Odds were higher for men compared with women, 1.02 (1.02–1.02; p < 0.001), for the most deprived decile compared with the least deprived, 2.26 (2.25–2.27; p < 0.001), and for Asian ethnicity compared with those of white ethnicity, 1.05 (1.04–1.05; p < 0.001). Odds were lower for black, mixed and other ethnicities (0.94 (0.94–0.95) p < 0.001, 0.87 (0.87–0.88) p < 0.001 and 0.57 (0.56–0.57) p < 0.001, respectively). MLTC for persons aged 0–19 years were dominated by asthma, autism and epilepsy, for persons aged 20–49 years by depression and asthma, for persons aged 50–59 years by hypertension and depression and for those aged 60 years and older, by cardiometabolic factors and osteoarthritis. There were large numbers of combinations of conditions in each age group ranging from 5936 in those aged 0–19 years to 205,534 in those aged 80 years and over.

Conclusions

While this study provides useful insight into the burden across the English population to assist health service delivery planning, the heterogeneity of MLTC presents challenges for delivery optimisation.

Keywords: Epidemiologic studies, epidemiology, health policy, health service research, medical management, quality improvement

Introduction

While most health systems internationally have evolved to provide diagnosis and management for single chronic conditions, there is a growing concern about the increase in people with multiple long-term conditions (MLTC), also termed multimorbidity. 1 People with MLTC have poorer health-related quality of life, poorer physical function, greater psychological needs, greater use of healthcare services and higher mortality.2 –4 Healthcare needs for people with MLTC are often complex, presenting a key challenge for the future of healthcare systems globally. This has therefore led to an emergence in recent years of both clinical guidelines for the management of MLTC, 5 and of frameworks and definitions to support prioritisation of MLTC for global health research. 6

Because of limited standardisation, the estimated prevalence of MLTC when defined as two or more concurrent conditions varies widely in published studies, ranging from 3.5% to 100%. 7 A recent systematic review of studies assessing MLTC prevalence concluded that the overall estimate in adults across all the included studies was 42%, but with very high heterogeneity, much of which could be accounted for by the mean age of the cohort studied and the number of conditions included as contributory to MLTC. 8 Similar heterogeneity was reported in another systematic review that found overall MLTC prevalence of 33%. 9 In view of different conditions being used, recently a global Delphi study developed international consensus on the definition and measurement of MLTC in research, focussing primarily on which long-term conditions to include. 10

The associations of both age and socioeconomic status with MLTC prevalence in the UK and in other high-income countries have been well described, with both higher age and more deprived socioeconomic status being associated with higher prevalence.11,12 While some studies have aimed to assess multimorbidity prevalence in nationally representative cohorts,13,14 many more have assessed prevalence in specific, often elderly, and small cohorts, 15 contributing to the heterogeneity described above. Results of stratification by sex have been mixed, although more studies have reported higher prevalence in women. 12 However, there has been very little work stratifying by ethnicity within populations served by the same healthcare system, 6 and limited work in children, and while a recent study has assessed both in a subset of the UK population, 14 this has not been assessed in a whole national, multi-ethnic, population.

Our aim was to determine the prevalence of MLTC at whole population level in England. We align as far as possible the long-term conditions included in our definition of MLTC to the core conditions listed in the recent Delphi consensus, and we stratify prevalence by age, sex, socioeconomic status and ethnicity.

Methods

Data sources and information governance

The National Bridges to Health Segmentation dataset was used to identify long-term conditions for individuals registered with General Practices in England.16 –18 The segmentation dataset has been produced, maintained and updated regularly since 2019 to support operational functions, care planning and improvement and service evaluation within NHS England.17,18 The dataset includes individuals registered with a general practice in England since 2014 and includes socio-demographic data (age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic deprivation), geographical data (registered general practice and mapped administrative NHS organisation), as well as clinical diagnostic data. The segmentation dataset has been derived from a number of national, predominantly secondary-care, patient-level datasets included in the National Commissioning Data Repository, 19 each of which were linked by pseudonymised NHS Number. This includes more than 15 years of longitudinally accrued data from Secondary Uses Services (a collection of data from all hospitals in England, including admitted patient care data, outpatient data and emergency care data), Mental Health data, Community data and the National Diabetes Audit. The full list of source datasets used to derive the Segmentation dataset, including the time over which data have been longitudinally accrued, is provided (Supplementary Table S1). The Segmentation dataset includes 35 long-term conditions, the process for selection of which has been outlined previously. 20 The 35 conditions were derived using data definitions based on logic and clinical codes (e.g. International Classification of Diseases, version 10 diagnostic codes, Office of Population Censuses and Surveys classification and surgical operations procedure codes and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clincal Terms codes), and were developed for each condition following extensive clinical review and evaluation. 21 The 35 conditions were mapped against the conditions suggested by the Delphi study with good concordance: the Segmentation dataset contains 22 of the 24 conditions categorised as ‘always include’ by the Delphi study and 20 of the 37 additional conditions categorised as ‘usually include’ (Table 1). 10 Further information on the accuracy of the coding in the segmentation dataset is outlined in Supplementary S2.

Table 1.

The 35 conditions included in the National Bridges to Health Segmentation Dataset mapped against the conditions suggested by the recent Delphi study.

| Bridges to health segmentation dataset condition listOrdered as list of LTCs (with severity of certain conditions grouped/paired) | Delphi condition list | |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol dependence | Usually include | Drug and alcohol misuse |

| Asthma | Always include | Asthma |

| Atrial fibrillation | Usually include | Arrhythmia |

| Autism | Usually include | Autism |

| Bronchiectasis | Usually include | Bronchiectasis |

| Cancer and incurable cancer | Always include | Metastatic cancer, haematological cancers, solid organ cancers, melanoma (usually include), treated cancer requiring surveillance (usually include) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | Always include | Stroke, TIA (usually include) |

| Chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal failure | Always include | Chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal failure |

| Chronic liver disease and liver failure | Always include | Chronic liver disease |

| Chronic pain | Usually include | Peripheral neuropathy |

| COPD and Severe COPD | Always include | COPD |

| Coronary heart disease | Always include | Coronary artery disease |

| Cystic fibrosis | Always include | Cystic fibrosis |

| Dementia | Always include | Dementia |

| Depression | Usually include | Depression |

| Diabetes | Always include | Diabetes |

| Epilepsy | Always include | Epilepsy |

| Heart failure and severe heart failure | Always include | Heart failure |

| Hypertension | Usually include | Treated or untreated hypertension |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Always include | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Intermediate and high frailty risk (HFRS) | ||

| Learning disability | ||

| Multiple sclerosis | Always include | Multiple sclerosis |

| Neurological organ failure | ||

| Osteoarthritis | Usually include | Osteoarthritis |

| Osteoporosis | Usually include | Osteoporosis |

| Parkinson's disease | Always include | Parkinson's disease |

| Peripheral vascular disease | Always include | Peripheral arterial disease |

| Physical disability | Usually include | Vision or hearing impairment that cannot be corrected, long-term MSK problems due to injury, congenital disease and chromosomal abnormalities, paralysis (other than stroke) |

| Pulmonary heart disease | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Always include | Connective tissue disorders |

| Sarcoidosis | ||

| Serious mental illness | Always include | Schizophrenia / bipolar (usually include) |

| Severe interstitial lung disease | ||

| Sickle cell disease | ||

| Not included | Always include | HIV/AIDS |

| Not included | Usually include | Heart valve disorders, pancreatic disease, thyroid disorders, anaemia, chronic Lyme disease, eating disorders, tuberculosis, endometriosis, peptic ulcer, post-traumatic stress disorder, post-acute COVID-19, benign cerebral tumours, chronic urinary tract infection, Meniere’s disease, anxiety, gout |

LTC: long-term condition; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TIA: transient ischaemic attack; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; MSK: musculoskeletal.

Data are collected and used in line with NHS England’s purposes as required under the statutory duties outlined in the NHS Act 2006 and Health and Social Care Act 2012. Data are processed using best practice methodology underpinned by a Data Processing Agreement between NHS England and Outcomes Based Healthcare Ltd (OBH), who produce the Segmentation Dataset on behalf of NHS England. This ensures controlled access by appropriate approved individuals, to anonymised/pseudonymised data held on secure data environments entirely within the NHS England infrastructure. Data are processed for specific purposes only, including operational functions, service evaluation and service improvement. Where OBH has processed data, this has been agreed and is detailed in a Data Processing Agreement. The data used to produce this analysis have been disseminated to NHS England under Directions issued under Section 254 of the Health and Social Care Act 2012.

Outcome

The outcome assessed was prevalent MLTC for individuals registered with a general practice in England and alive as of 31 March 2020. MLTC was defined as two or more of the 35 long-term conditions recorded in the Segmentation dataset (Table 1). Secondary analyses assessed prevalence of three or more, four or more, five or more or six or more of the 35 conditions.

Combinations of conditions were calculated in two ways: where the combinations of conditions occurred both uniquely and together with one or more other conditions and, where the combinations of conditions occurred uniquely with no other conditions. The comparison of these two different approaches serves to quantify the differences in proportions in those with just two conditions compared with those with more than two conditions.

Covariates

Sex was recorded as male, female or indeterminate. Age was calculated as of 31 March 2020 and first, the five most frequent long-term conditions were assessed for each 10-year age band (Supplementary S3). Adjacent 10-year age bands were then grouped together if their long-term condition frequency patterns were similar. This resulted in the following age bands: 0–19 years, 20–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79 and 80 years and over. Socioeconomic status was measured using deciles of Index of Multiple Deprivation associated with the Lower Super Output Area derived from individual postcode. 22 For ethnicity, each individual was assigned their most frequently recorded ethnicity across all source datasets then allocated to one of the corresponding high-level groupings: Asian, black, mixed, other and white. It was not possible to identify the ethnicity for 17% of the population due to patients not accessing secondary-care services or ethnicity reported as unknown in the source datasets; however, 98.5% of those with MLTC had ethnicity recorded.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of MLTC as of 31 March 2020 by age, sex, ethnicity and deprivation was calculated. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to assess the independent associations of age, sex, ethnicity and deprivation decile with odds of prevalent MLTC. Separate models were run stratified by six age groups, 0–19 years, 20–49 years, 50–59 years, 60–69 years, 70–79 years and 80 years and over. Separate models were also run for prevalence of 3+, 4+, 5+ or 6+ conditions. The C-statistic was used to assess model fit. A sensitivity analysis was carried out excluding people of unknown ethnicity and the proportion of different ethnicities in the population with known ethnicity were compared with the 2021 census.

Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 and confidence intervals (CIs) were set at 95%. All data were analysed using Stata, version 16.

Results

There were 60,004,883 individuals who were registered with a general practice in England and alive on 31 March 2020. Characteristics of the population are shown in Table 2: the mean (SD) age was 40 (23) years; 50.2% were women and 67.7% were of white, 6.7% Asian, 3.3% black, 1.9% mixed, 3.1% other and 17.4% of unknown ethnicity. Nearly one-third (29.3%) of individuals had at least one recorded long-term condition and ranged from 6.6% in those aged 0–19 years to 82.9% in those aged 80 years and over (Supplementary S4). The prevalence of each long-term condition, stratified by the six age categories, is shown in Supplementary S5.

Table 2.

Characteristics of prevalence of multiple long-term conditions for individuals registered with a General Practice in England and alive on 31 March 2020.

| Number of individuals |

Percentage |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Not multimorbid | Multimorbid | Overall (%) | Not multimorbid (%) | Multimorbid (%) | Prevalence of multimorbid (2+) (%) | |

| Overall | 60,004,883 | 51,126,652 | 8,878,231 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 14.8 |

| Age band | |||||||

| 0–19 | 13,256,169 | 13,131,010 | 125,159 | 22.1 | 25.7 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

| 20–49 | 25,308,181 | 23,823,983 | 1,484,198 | 42.2 | 46.6 | 16.7 | 5.9 |

| 50–59 | 7,942,103 | 6,580,661 | 1,361,442 | 13.2 | 12.9 | 15.3 | 17.1 |

| 60–69 | 5,979,993 | 4,194,590 | 1,785,403 | 10.0 | 8.2 | 20.1 | 29.9 |

| 70–79 | 4,721,726 | 2,505,676 | 2,216,050 | 7.9 | 4.9 | 25.0 | 46.9 |

| 80+ | 2,796,711 | 890,732 | 1,905,979 | 4.7 | 1.7 | 21.5 | 68.2 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 29,905,854 | 25,755,849 | 4,150,005 | 49.8 | 50.4 | 46.7 | 13.9 |

| Female | 30,098,088 | 25,369,980 | 4,728,108 | 50.2 | 49.6 | 53.3 | 15.7 |

| Indeterminate | 941 | 823 | 118 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | 12.5 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Asian | 4,025,992 | 3,535,766 | 490,226 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 5.5 | 12.2 |

| Black | 1,976,149 | 1,728,473 | 247,676 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 12.5 |

| Mixed | 1,148,763 | 1,073,887 | 74,876 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 6.5 |

| Other | 1,836,965 | 1,696,586 | 140,379 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 1.6 | 7.6 |

| White | 40,604,214 | 32,812,336 | 7,791,878 | 67.7 | 64.2 | 87.8 | 19.2 |

| Unknown | 10,412,800 | 10,279,604 | 133,196 | 17.4 | 20.1 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| Deprivation quintile | |||||||

| 1 (most deprived) | 6,125,003 | 5,136,089 | 988,914 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 11.1 | 16.1 |

| 2 | 6,198,675 | 5,271,107 | 927,568 | 10.3 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 15.0 |

| 3 | 6,309,276 | 5,407,278 | 901,998 | 10.5 | 10.6 | 10.2 | 14.3 |

| 4 | 6,206,979 | 5,301,360 | 905,619 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 10.2 | 14.6 |

| 5 | 6,023,492 | 5,124,477 | 899,015 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.1 | 14.9 |

| 6 | 6,057,060 | 5,160,282 | 896,778 | 10.1 | 10.1 | 10.1 | 14.8 |

| 7 | 5,837,933 | 4,958,835 | 879,098 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 9.9 | 15.1 |

| 8 | 5,842,753 | 4,978,526 | 864,227 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 14.8 |

| 9 | 5,701,186 | 4,865,628 | 835,558 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 14.7 |

| 10 (least deprived) | 5,702,526 | 4,923,070 | 779,456 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 8.8 | 13.7 |

Of the 60,004,883 individuals registered with a general practice in England and alive as of 31 March 2020, 8,878,231 individuals had two or more conditions, corresponding to a prevalence of 14.8% (Table 2). There were 5,162,244 individuals (8.6%) who had three or more conditions, 3,102,389 (5.2%) who had four or more conditions, 1,891,121 (3.2%) who had five or more conditions and 1,152,357 (1.9%) who had six or more conditions (Supplementary S4). Univariate analyses of MLTC prevalence by age, sex, ethnicity and deprivation are shown in Table 2, S4 and S6. MLTC prevalence increased with age from 0.9% (95% CI: 0.9%–1.0%) in those aged 0–19 years to 68.2% (68.1%–68.2%) in those aged 80 years and over and was higher in women than men, 15.7% (15.7%–15.7%) vs. 13.9% (13.9%–13.9%), respectively. Prevalence was higher among those living in the most deprived decile compared with those living in the least deprived decile, 16.1% (16.1%–16.2%) vs. 13.7% (13.6%–13.7%), respectively and there were significant differences by ethnicity; 19.2% (19.2%–19.2%) for those of White ethnicity, compared with 12.2% (12.1%–12.2%), 12.5% (12.5%–12.6%) and 6.5% (6.5%–6.6%) for those of Asian, black and mixed ethnicities, respectively.

Multivariable regression analyses showed that the strong association between MLTC and age was retained, and indeed dominant (Figure 1). Compared with the 50–59 reference group, the odds ratio (OR) was 0.04 (95% CI: 0.04–0.04; p < 0.001), for those aged 0–19 years and 10.21 (10.18–10.24; p < 0.001) for those aged 80 years and over. Odds were statistically higher for men compared with women, although the differences were only small (OR: 1.02 (1.02–1.02; p < 0.001)). Odds were higher for the most deprived decile compared with the least deprived decile, 2.26 (2.25–2.27; p < 0.001). By ethnicity, odds were statistically higher for Asian ethnicity compared with those of white ethnicity (1.05 (1.04–1.05; p < 0.001), while odds were lower for Black, mixed and other ethnicities: 0.94 (0.94–0.95; p < 0.001), 0.87 (0.87–0.88; p < 0.001) and 0.57 (0.56–0.57; p < 0.001), respectively. The C-statistic was 0.87.

Figure 1.

Adjusted odds ratios for multiple long-term conditions for all individuals registered with a general practice in England.

Overall, the proportions of people of different ethnicities for whom ethnicity information was available were broadly similar to the proportions in the 2021 census (Supplementary S7). There was a greater proportion of missing data for ethnicity in those aged 20–49 years and in men (Supplementary S8), but in a sensitivity analysis excluding individuals with missing ethnicity data, the results were unchanged (Supplementary S9).

Separate regression models were run by age group (Supplementary Table S10) and for 3+, 4+, 5+ and 6+ conditions (Supplementary Table S11). The relative effect of deprivation increased as age group increased until 50–59 years and then decreased thereafter with the effect of deprivation smallest in the 80+ years age group (Supplementary Table S10). Odds were higher for men aged 0–19 years and 60 years and over, but lower in the 20–59 age groups, while odds were lower for Asian ethnicity in those aged 0–19 years and 20–49 years but were higher for those aged 50 years and over (Supplementary Table S10). Black ethnicity gave mixed results in that odds were higher in those aged 0–19 years and 70–79 years, lower in those aged 20–59 years and similar in the remaining age groups. The relative effect of age, male sex and deprivation increased as the number of conditions increased, while there was an increase in the relative effect for Asian ethnicity when the number of conditions increased from 2 to 3, but no change for higher minimum numbers of conditions (Supplementary S11).

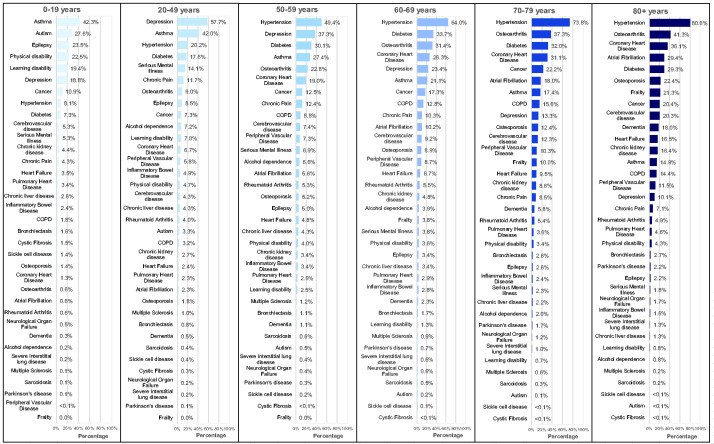

The prevalence of the 35 long-term conditions in those with MLTC, stratified by age group, is shown in Figure 2. In individuals aged 0–19 years, asthma, autism and epilepsy were dominant, while in individuals aged 20–49 years, depression and asthma were dominant and in individuals aged 50–59 years, hypertension and depression were dominant. In individuals aged 60–69 years, 70–79 years and 80+ years, cardiometabolic factors and osteoarthritis were dominant. There were differences in the most common conditions by sex, ethnicity and deprivation. For example, in those aged 0–19 years, men and those of white ethnicity had higher prevalences of autism compared with women and those of Asian ethnicity, while in those aged 20–49 years, women, those of white ethnicity and those from the most deprived quintile had higher prevalences of depression compared with men, those of Asian ethnicity and from the least deprived quintile. In older age groups, there were higher prevalences of coronary heart disease, diabetes and hypertension but lower prevalences of cancer and depression for those of Asian ethnicity compared with those of white ethnicity. However, differences between conditions were generally less marked than the differences observed due to age (Supplementary Tables S12–S14).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of the 35 long-term conditions in those with multiple long-term conditions stratified by age group.

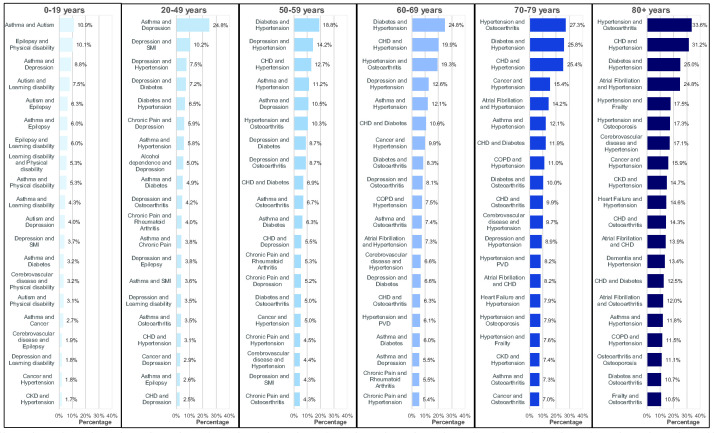

The most common combinations of long-term conditions, where the combinations may occur either uniquely or together with one or more other conditions, stratified by age group, are shown in Figure 3. For those aged 0–19 years, asthma and autism were the most common combination, with a prevalence of 10.9%, while asthma and depression were the most common for those aged 20–49 years, with a prevalence of 24.8%. For those aged 50–59 years and 60–69 years, diabetes with hypertension were the most common combination, with prevalences of 18.8% and 24.8%, respectively, while for those aged 70–79 years and 80+ years, hypertension and osteoarthritis were the most common, with prevalences of 27.3% and 33.6%, respectively. However, there were very large numbers of unique combinations of conditions: ranging from 5936 combinations for those aged 0–19 years to 205,534 combinations for those aged 80 years and over. The most common unique combinations of long-term conditions, occurring with no other conditions, stratified by age group, are shown in Supplementary Table S15. These unique combinations, in particular for older age groups, have significantly lower prevalences than combinations that can be either unique or occur together with one or more conditions. For example, while the prevalence of hypertension and osteoarthritis with or without any other conditions for those aged 80 years and over was 33.6%, the prevalence of hypertension and osteoarthritis with no other condition was 3.2%. In total, there were 84,138 unique combinations of conditions that included both hypertension and osteoarthritis for those aged 80 years and over; for example, 16,857 (2.6%) had hypertension, osteoarthritis and diabetes, 13,580 (2.1%) had hypertension, osteoarthritis and coronary heart disease, and 11,132 (1.7%) had hypertension, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. Supplementary S16 lists the most common unique combinations including hypertension and osteoarthritis.

Figure 3.

Top 20 most common combinations of conditions, where combinations occurred both uniquely, and together with one or more other conditions, for those with multiple long-term conditions stratified by age group.

The top 20 unique combinations of conditions accounted for decreasing proportions of the total number of people with MLTC by age group, ranging from 47.3% of people aged 0–19 years with MLTC to 15.6% of people aged 80+ years with MLTC. This increased to 67.6% of people aged 0–19 and 86.6% of people aged 80 years and over when considering those with at least one of the top 20 combinations, either uniquely or with one or more conditions.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study of MLTC to date, covering a whole national population, providing data on children as well as adults and stratified by ethnicity within a multi-ethnic population served by the same healthcare system. We have found overall prevalence of MLTC in the English population to be 14.8% with, as expected, age the dominant predictor. While asthma, autism and epilepsy were dominant in children aged up to 19 years, depression and asthma dominated for those aged 20–49 years, hypertension and depression for 50–59 years and cardiometabolic conditions and osteoarthritis for older age groups.

While the definition of MLTC as two or more conditions has been widely accepted internationally in recent years, the determination of which conditions to include has not. A nationally representative study of the Scottish population using data from general practice electronic health records in 2007 11 included data for 1,751,841 people and 40 conditions (24 of which overlapped with the conditions used in our study) and found a prevalence of MLTC of 23.3%. A similar study of adults in England in 2018 used data from general practice electronic health records for 403,985 people 23 and 36 conditions (largely based on the Scottish study) and found a prevalence of MLTC of 27.2%. A more recent study of a nationally representative cohort of 3,872,451 people in England used general practice electronic health records linked with secondary care admissions for 308 conditions and found a prevalence of 71.3%. 14 We have aligned our study to a recent global Delphi study that developed an international consensus for the definition and measurement of MLTC, and the inclusion of 35 conditions in our study has derived a predictably lower prevalence. Aligning our study with the Delphi consensus study will enable better comparison with future studies, although will not assist comparison of existing studies that do not follow this protocol. However, while we aligned with the Delphi consensus study as much as possible, it was not possible to achieve full alignment.

Previous studies have reported higher MLTC prevalence in those from the most deprived quintile compared with the least deprived quintile, which aligns with the findings of our study.11,23 We report that the association between multimorbidity and socioeconomic status is most pronounced in middle age, with prevalence of MLTC in the cohort aged 50–59 years in the most socioeconomically deprived decile nearly three times the odds (2.76 (95% CI: 2.73–2.78)) in the least deprived. The association between multimorbidity and socioeconomic status has the smallest effect in those aged 80 years and older.

In univariate analysis, MLTC prevalence is markedly lower overall in those of Asian or black ethnicity compared with those of white ethnicity (12.2 and 12.5 vs. 19.2%, respectively), similar to another recent UK study. 14 However, in our multivariable analysis, differences in MLTC prevalence by ethnicity are attenuated, and indeed, although differences were only small, were higher in those of Asian compared with those of white ethnicities. Prevalence remained lower in multivariable analysis in those of black, mixed and other ethnicities compared with those of white ethnicities. However, there were significant differences by age group for Asian and black ethnicities. In Asian ethnicity, the adjusted OR for younger ages was between 10% and 30% lower than white ethnicities, while for older age groups it was between 20% and 60% higher. Black ethnicity gave mixed results. This contrasts with US studies that found that black adults have higher prevalence of MLTC.24,25 A study in England found higher prevalence of MLTC in South Asian and black ethnicity compared with white ethnicity, while another study found higher MLTC prevalence in black ethnicity compared with white ethnicity.26,27 However, both studies were based on a subset of the respective populations and used different definitions of MLTC. Other representative studies in the United Kingdom have not presented the data by ethnicity.11,23 In the 17% of the English population of unknown ethnicity in the Segmentation dataset, prevalence of multimorbidity is particularly low, but reflects the fact that those without medical issues are less likely to have attended a medical healthcare facility where they might have their ethnicity recorded.

Stratification by sex also resulted in opposite signals in univariate compared with multivariable analyses, with odds for having MLTC higher for women than men in univariate analysis and higher for men in multivariable analysis, although these differences were small. However, the relative effect of men increased as number of conditions increased. There were also differences by age, in that odds were higher in those aged 0–19 years and in those aged 60 years and over, but lower in those aged 20–59 years. This would be consistent with the lack of clarity in the published literature, with results of stratification by sex mixed, although more studies reporting higher prevalence in women.11,12,23

Although the epidemiology of MLTC in younger populations is not well characterised, the prevalence in our study was unsurprisingly low in children, at 0.9% (125,159) of the 13,256,169 children and young adults aged 0–19 years. The selection of long-term conditions is, however, based on a focus on adult populations who use healthcare services more frequently. Australian data based on self-reporting have suggested a prevalence of MLTC of 20% in children, but these also included hayfever, allergic rhinitis, anxiety and psychological development problems, none of which are captured in the English Segmentation dataset used in our study, and which, along with asthma, formed the most prevalent conditions among all children with chronic conditions in the Australian data. 28 Furthermore, because the threshold for hospitalisation is often higher in children with chronic conditions, hospital-based administrative data may not capture all relevant conditions for children, a potential limitation regarding the current English Segmentation dataset. 29

The number of different combinations of conditions in those with MLTC is large, involving hundreds of thousands of combinations. Various statistical methods have been employed in other studies to try to identify dominant disease clusters.12,30 –32 However, different methods vary in the degree by which they take into account the possibility of combinations arising by chance, and indeed a study that compared the application of five different methodologies (factor analysis, hierarchical-clustering analysis, unified-clustering algorithm, multiple correspondence analysis, and network and cluster analyses) to the same Australian National Health Survey dataset, revealed different multimorbidity patterns dependent on the method employed. 33 The heterogeneity of MLTC therefore presents challenges in optimising health service delivery, which address the specific needs of patients with MLTC. However, similar risk factors are associated with a diverse number of MLTC and could therefore be potentially targeted for preventative intervention. Obesity has been recognised as a potentially important interventional target to prevent subsequent complex MLTC. 34 Lifestyle interventions, focussing on weight loss in those with raised body mass index, have been implemented at scale in England – for example, the NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme, a 9-month intensive lifestyle intervention, has now seen over 1.3 million individuals with pre-diabetes across England referred into the programme, and provides future opportunities to assess impact of weight-loss interventions on incident MLTC. 35 As part of the support made available for local and national health service planning, these data contribute to the Population and Person Insights dashboard, accessible by NHS organisations with dashboard data presented by different NHS administrative footprints, including at national level (https://apps.model.nhs.uk/report/PaPi).

Strengths and limitations

The study includes those registered with a General Practice in England as of 31 March 2020. Previous work has suggested that over 98% of the English population are registered with a general practice, 36 so the data are highly representative of the English population. This is the largest MLTC study to date that reports data on a whole population by age, sex, socioeconomic deprivation and ethnicity, and therefore provides new insights into areas so far under-investigated, in particular the characterisation of childhood multimorbidity and the associations with ethnicity. It applies the standard definition of MLTC and aligns well to recent consensus around which long-term conditions should be included in the MLTC entity. 10 Ascertainment of long-term condition status is derived predominantly from hospital and community coded datasets (Supplementary Table S1), rather than general practice datasets, so there is likely to be under-ascertainment for those conditions usually diagnosed in general practice: this particularly affects ascertainment of chronic kidney disease (without end-stage renal failure), depression and hypertension. 17 Furthermore, individuals associated with different socio-demographic factors may differ in the extent and manner in which they access healthcare. This could exacerbate differences between actual and diagnosed MLTC for some groups of patients (for example, particular ethnic or deprivation groups may be reluctant to see their general practitioner, even if they are registered with one). This could therefore lead to a biased comparison of MLTC between demographic groups. These differences may be more likely to impact primary care contact and less likely to impact more acute healthcare interactions (as these are generally less avoidable). Given source datasets for the National Bridges to Health Segmentation dataset are primarily secondary care datasets, the impact on this study may be expected to be low.

The current analyses presented are cross-sectional, and so can only highlight associations rather than providing new definitive insights into causality. The longitudinal capture of data will, however, provide opportunities to assess changing MLTC prevalence in England in the future, and opportunities to assess MLTC incidence, costs and associated outcomes, in our attempts to commission services that better meet the needs of people with MLTC. We have used simple counts of conditions and narrative descriptions of groups of conditions, rather than assessing differential severity of conditions or burden of conditions on health-related quality of life, or indeed employing more complex statistical methods to try to identify dominant disease clusters.

Implications

This study applies the most comprehensive and contemporary data to date to assess prevalence of MLTC across the English population, examines the influence of different demographic characteristics on prevalence and assesses frequency of disease combinations. While the study provides useful insight into the burden of MLTC across the English population to assist health service delivery planning into the future, the heterogeneity of MLTC presents challenges in optimising health service delivery to address the specific needs of patients with MLTC.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jrs-10.1177_01410768231206033 for Prevalence of multiple long-term conditions (multimorbidity) in England: a whole population study of over 60 million people by Jonathan Valabhji, Emma Barron, Adrian Pratt, Nasrin Hafezparast, Rupert Dunbar-Rees, Ellie Bragan Turner, Kate Roberts, Jacqueline Mathews, Robbie Deegan, Victoria Cornelius, Jason Pickles, Gary Wainman, Chirag Bakhai, Desmond G Johnston, Edward W Gregg and Kamlesh Khunti in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Jonathan Valabhji https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9756-4061

Emma Barron https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6257-9044

Kate Roberts https://orcid.org/0009-0001-3942-2353

Declarations

Competing Interests

JV is National Clinical Director for Diabetes and Obesity at NHS England. KK is National National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration Lead for MLTC and Director of NIHR Global Research Centre for MLTC. NH, EBT and RDR are employed by Outcomes Based Healthcare, which receives funding from NHS organisations (including NHS England) for providing analytical services. JM is NIHR Clinical Research Network (CRN) Project Lead for MLTC and Head of Cluster A, NIHR CRN Coordinating Centre. KR is NIHR Clinical Research Network Project Manager for MLTC.

Funding

None declared.

Ethics approval

Not applicable. Data is collected and used in line with NHS England's purposes as required under the statutory duties outlined in the NHS Act 2006 and Health and Social Care Act 2012. Data is processed using best practice methodology underpinned by a Data Processing Agreement between NHS England and Outcomes Based Healthcare Ltd (OBH), who produce the Segmentation Dataset on behalf of NHS England. This ensures controlled access by appropriate approved individuals, to anonymised/pseudonymised data held on secure data environments entirely within the NHS England infrastructure. Data is processed for specific purposes only, including operational functions, service evaluation and service improvement. Where OBH has processed data, this has been agreed and is detailed in a Data Processing Agreement. The data used to produce this analysis has been disseminated to NHS England under Directions issued under Section 254 of the Health and Social Care Act 2012.

Guarantor

JV.

Contributorship

JV, AP, EWG and KK conceived the study. EB and AP did the statistical analysis. All authors collaborated in interpretation of the results and drafting of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Imperial College London (JV, DGJ and EWG) is grateful for support from the North West London National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration and the Imperial NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. KK is supported by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands (ARC EM) and the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Sun Jae Park and Julie Morris.

References

- 1.Head A, Fleming K, Kypridemos C, Schofield P, Pearson-Stuttard J, O’Flaherty M. Inequalities in incident and prevalent multimorbidity in England, 2004–19: a population-based, descriptive study. Lancet Healthy Longev 2021; 2: e489–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chudasama YV, Khunti K, Gillies CL, Dhalwani NN, Davies MJ, Yates T, et al. Healthy lifestyle and life expectancy in people with multimorbidity in the UK Biobank: a longitudinal cohort study. PLoS Med 2020; 17: e1003332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frølich A, Ghith N, Schiøtz M, Jacobsen R, Stockmarr A. Multimorbidity, healthcare utilization and socioeconomic status: a register-based study in Denmark. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0214183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sathanapally H, Sidhu M, Fahami R, Gillies C, Kadam U, Davies MJ, et al. Priorities of patients with multimorbidity and of clinicians regarding treatment and health outcomes: a systematic mixed studies review. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e033445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management NICE guideline. 2016. See www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56/resources/multimorbidity-clinical-assessment-and-management-pdf-1837516654789 (last checked 19 August 2022).

- 6.Academy of Medical Sciences. Multimorbidity: a priority for global health research. 2018. See https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/82222577 (last checked 19 August 2022).

- 7.Xu X, Mishra GD, Jones M. Evidence on multimorbidity from definition to intervention: an overview of systematic reviews. Ageing Res Rev 2017; 37: 53–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho ISS, Azcoaga-Lorenzo A, Akbari A, Davies J, Hodgins P, Khunti K, et al. Variation in the estimated prevalence of multimorbidity: systematic review and meta-analysis of 193 international studies. BMJ Open 2022; 12: e057017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen H, Manolova G, Daskalopoulou C, Vitoratou S, Prince M, Prina AM. Prevalence of multimorbidity in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Comorb 2019; 9: 2235042X19870934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho ISS, Azcoaga-Lorenzo A, Akbari A, Davies J, Khunti K, Kadam UT, et al. Measuring multimorbidity in research: Delphi consensus study. BMJ Med 2022; 1: e000247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012; 380: 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Violan C, Foguet-Boreu Q, Flores-Mateo G, Salisbury C, Blom J, Freitag M, et al. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of observational studies. PLoS One 2014; 9: e102149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Britt HC, Harrison CM, Miller GC, Knox SA. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in Australia. Med J Aust 2008; 189: 72–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuan V, Denaxas S, Patalay P, Nitsch D, Mathur R, Gonzalez-Izquierdo A, et al. Identifying and visualising multimorbidity and comorbidity patterns in patients in the English National Health Service: a population-based study. Lancet Digit Health. 2023; 5: e16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhalwani NN, O’Donovan G, Zaccardi F, Hamer M, Yates T, Davies M, et al. Long terms trends of multimorbidity and association with physical activity in older English population. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity 2016; 13: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, Weaver A, Bradley D, Ismail H, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: a whole-population study. Lancet Diab Endocrinol 2020; 8: 813–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Background and information on the NHS England Segmentation dataset. See https://outcomesbasedhealthcare.com/nhse-segmentation-dataset-reference-guide/ (last checked 2 June 2023).

- 18.Lynn J, Straube BM, Bell KM, Jencks SF, Kambic RT. Using population segmentation to provide better health care for all: the “Bridges to Health” Model. Milbank Q 2007; 85: 185–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NHS England. NCDR Reference Library. See https://data.england.nhs.uk/ncdr/database/ (last checked 21 August 2022).

- 20.Hafezparast N, Turner EB, Dunbar-Rees R, Vodden A, Dodhia H, Reynolds B, et al. Adapting the definition of multimorbidity – development of a locality-based consensus for selecting included long term Conditions. BMC Fam Pract 2021; 22: 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subsegment/Condition Definitions. See https://outcomesbasedhealthcare.com/condition-definitions-overview/ (last checked 2 June 2023).

- 22.Gov.UK National Statistics. English Indices of Deprivation 2019. 2019. See www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019 (last checked 22 August 2022).

- 23.Cassell A, Edwards D, Harshfield A, Rhodes K, Brimicombe J, Payne R, et al. The epidemiology of multimorbidity in primary care. Br J General Pract 2018; 68: e245–e251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quiñones AR, Botoseneanu A, Markwardt S, Nagel CL, Newsom JT, Dorr DA, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in multimorbidity development and chronic disease accumulation for middle-aged adults. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0218462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathur R, Hull S, Badrick E, Robson J. Cardiovascular multimorbidity: the effect of ethnicity on prevalence and risk. Br J Gen Practice 2011; 61: e262–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bisquera A, Turner EB, Ledwaba-Chapman L, Dunbar-Rees R, Hafezparast N, Gulliford M, et al. Inequalities in developing multimorbidity over time: a population-based cohort study from an urban, multiethnic borough in the United Kingdom. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2021; 12: 100247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carabelloe C, Herrin J, Mahajan S, Massey D, Lu Y, Ndumele CD, et al. Temporal trends in racial and ethnic disparities in multimorbidity prevalence in the United States, 1999–2008. Am J Med 2022; 135: 1083–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Australian Government. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Children. See www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/6af928d6-692e-4449-b915-cf2ca946982f/aihw-cws-69-print-report.pdf.aspx?inline=true (last checked ▪ 2022) pp. 63–67.

- 29.van den Akker M, Dieckelmann M, Hussain MA, Bond-Smith D, Muth C, Pati S, et al. Children and adolescents are not small adults: toward a better understanding of multimorbidity in younger populations. J Clin Epidemiol 2022; 149: 165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirchberger I, Meisinger C, Heier M, Zimmermann AK, Thorand B, Autenrieth CS, et al. Patterns of multimorbidity in the aged population. Results from the KORA-Age study. PLoS One 2012; 7: e30556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zemedikun DT, Gray LJ, Khunti K, Davies MJ, Dhalwani NN. Patterns of multimorbidity in middle-aged and older adults: an analysis of the UK Biobank Data. Mayo Clin Proc 2018; 93: 857–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ioakeim-Skoufa I, Poblador-Plou B, Carmona-Pírez J, Díez-Manglano J, Navickas R, Gimeno-Feliu LA, et al. Multimorbidity patterns in the general population: results from the EpiChron Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 4242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ng SK, Tawiah R, Sawyer M, Scuffham P. Patterns of multimorbid health conditions: a systematic review of analytical methods and comparison analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2018; 47: 1687–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kivimäki M, Strandberg T, Pentti J, Nyberg ST, Frank P, Jokela M, et al. Body-mass index and risk of obesity-related complex multimorbidity: an observational multicohort study. Lancet Diab Endocrinol 2022; 10: 253–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valabhji J, Kar P. Rise in type 2 diabetes shows that prevention is more important than ever. BMJ 2023; 381: 910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K, Forbes H, Mathur R, van Staa T, et al. Data resource profile: clinical practice research datalink (CPRD). Int J Epidemiol 2015; 44: 827–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jrs-10.1177_01410768231206033 for Prevalence of multiple long-term conditions (multimorbidity) in England: a whole population study of over 60 million people by Jonathan Valabhji, Emma Barron, Adrian Pratt, Nasrin Hafezparast, Rupert Dunbar-Rees, Ellie Bragan Turner, Kate Roberts, Jacqueline Mathews, Robbie Deegan, Victoria Cornelius, Jason Pickles, Gary Wainman, Chirag Bakhai, Desmond G Johnston, Edward W Gregg and Kamlesh Khunti in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine