Abstract

Background

Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) methylates multiple substrates dysregulated in cancer, including spliceosome machinery components. PF-06939999 is a selective small-molecule PRMT5 inhibitor.

Patients and methods

This phase I dose-escalation and -expansion trial (NCT03854227) enrolled patients with selected solid tumors. PF-06939999 was administered orally once or twice a day (q.d./b.i.d.) in 28-day cycles. The objectives were to evaluate PF-06939999 safety and tolerability to identify maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and recommended part 2 dose (RP2D), and assess pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacodynamics [changes in plasma symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) levels], and antitumor activities.

Results

In part 1 dose escalation, 28 patients received PF-06939999 (0.5 mg q.d. to 6 mg b.i.d.). Four of 24 (17%) patients reported dose-limiting toxicities: thrombocytopenia (n = 2, 6 mg b.i.d.), anemia (n = 1, 8 mg q.d.), and neutropenia (n = 1, 6 mg q.d.). PF-06939999 exposure increased with dose. Steady-state PK was achieved by day 15. Plasma SDMA was reduced at steady state (58%-88%). Modulation of plasma SDMA was dose dependent. No MTD was determined. In part 2 dose expansion, 26 patients received PF-06939999 6 mg q.d. (RP2D). Overall (part 1 + part 2), the most common grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events included anemia (28%), thrombocytopenia/platelet count decreased (22%), fatigue (6%), and neutropenia (4%). Three patients (6.8%) had confirmed partial response (head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, n = 1; non-small-cell lung cancer, n = 2), and 19 (43.2%) had stable disease. No predictive biomarkers were identified.

Conclusions

PF-06939999 demonstrated a tolerable safety profile and objective clinical responses in a subset of patients, suggesting that PRMT5 is an interesting cancer target with clinical validation. However, no predictive biomarker was identified. The role of PRMT5 in cancer biology is complex and requires further preclinical, mechanistic investigation to identify predictive biomarkers for patient selection.

Key words: PF-06939999, PRMT5 inhibitor, phase I, dose escalation, dose expansion, solid tumors

Highlights

-

•

This is a first-in-human dose-escalation/expansion study of PF-06939999, a selective small-molecule inhibitor of PRMT5.

-

•

Patients with selected solid tumors were treated with PF-06939999 0.5-12 mg daily (q.d. or b.i.d.).

-

•

PF-06939999 had a tolerable safety profile. Most common ≥G3 treatment-related AEs: hematological toxicities. RP2D: 6 mg q.d.

-

•

Response was seen in a subset of patients with metastatic NSCLC and HNSCC, suggesting PRMT5 is a cancer therapeutic target.

-

•

No predictive biomarker was identified. Additional mechanism studies of PRMT5 are needed for patient selection.

Introduction

Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) is a type II arginine methyltransferase that catalyzes the formation of a monomethyl arginine and symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM).1 PRMT5 methylates multiple protein substrates with a variety of biological functions known to be dysregulated in cancer such as pre-messenger RNA (mRNA) splicing, DNA damage, and other cell signaling processes.1 Inhibition of PRMT5 reduces SDMA levels and leads to growth arrest and cell death in tumors that harbor alterations in mRNA splicing pathways.1

PF-06939999 is an orally available small-molecule selective inhibitor of PRMT5 (Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102961).2 Cellular activity of PF-06939999 is measured by the reduction in its direct product, SDMA.2 PF-06939999 demonstrated anti-proliferative activity in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells in vitro and was less susceptible to the development of mutations that confer complete drug resistance versus previously described SAM-cooperative binding compounds.2 Furthermore, NSCLC response to PF-06939999 in vitro and in vivo in an animal model was associated with mutations in splicing factors, suggesting that tumors with dysregulated alternative splicing caused by mutations in splicing factors may be more sensitive to PRMT5 inhibitors.2

Splicing dysregulation is a well-known molecular feature of cancer and is driven by mutations and altered expression of splicing factor genes.3,4 In an analysis of the Cancer Genome Atlas, the incidence of recurrent somatic mutations and copy number alterations in 119 splicing factor genes, including genes encoding well-characterized splicing factors SF3B1, U2AF1, SRSF2, FUBP1, ZRSR2, and RBM1017, in tumors was identified.4 In NSCLC samples, the incidence of such mutations was 46%, one of the highest among all tumor types evaluated. Other solid tumors with high incidence of splicing factor mutations included head and neck cancer (51%), cervical cancer (42%), endometrial cancer (38%), esophageal cancer (44%), and bladder cancer (51%).

Given the preclinical data for PF-06939999 in NSCLC and the potential for targeting PRMT5 in other cancers enriched for splicing factor mutations, a first-in-human, phase I clinical study (NCT03854227) of PF-06939999 was conducted in patients with locally advanced/metastatic NSCLC or other selected advanced or metastatic solid tumors with high incidence of splicing factor gene mutations.5 Preliminary findings from this study demonstrated that PF-06939999 had dose-dependent and manageable toxicities, while achieving objective tumor responses in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and NSCLC.5

Here we describe the results from the final analysis of this first-in-human clinical study of PF-06939999 conducted in patients with selected advanced or metastatic HNSCC, NSCLC, or esophageal, endometrial, cervical, or bladder cancer.

Patients and methods

Study design

This was a first-in-human, phase I, open-label, multicenter, dose-escalation and dose-expansion study (NCT03854227) to assess the safety, pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacodynamics (PD), and antitumor activity of PF-06939999 monotherapy in patients with selected locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors. The study had two parts (Supplementary Figure S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102961): dose escalation (part 1) followed by dose expansion (part 2).

Part 1 evaluated the safety, PK, and PD of PF-06939999 in patients with HNSCC, NSCLC, esophageal, endometrial, cervical, or bladder cancer to determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and recommended part 2 dose (RP2D). Dose finding was guided by a Bayesian logistic regression model. The starting dose of PF-06939999 was 0.5 mg orally once daily (q.d.).

Part 2 evaluated the safety, tolerability, and preliminary antitumor activity of PF-06939999 at the RP2D in patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC (part 2A), urothelial carcinoma (UC; part 2B), and HNSCC (part 2C).

Patients received PF-06939999 orally q.d. or twice daily (b.i.d.) as monotherapy on an empty stomach in 28-day cycles continuously. This study was stopped in November 2021.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles derived from the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with the applicable International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. All local regulatory requirements, including privacy laws, were followed. The study protocol, protocol amendments, and informed consent documentation were reviewed and approved by institutional review boards. All patients provided informed consent before being enrolled in the study.

Primary and secondary objectives, endpoints, and assessments

For part 1 (dose escalation), the primary objectives were to assess the safety and tolerability of PF-06939999 to determine the MTD and RP2D. Primary endpoints were dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs, for criteria see Supplementary Material, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102961), adverse events (AEs), and laboratory abnormalities [using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) 5.0 criteria]. Secondary objectives were single- and multiple-dose PK at different dose levels and antitumor activities. Secondary endpoints were PK parameters, and objective response rate and duration of response (DoR) based on RECIST v1.1.

For part 2 (dose expansion), the primary objectives were to assess the safety, tolerability, and clinical efficacy of PF-06939999 in patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC, UC, and HNSCC. Primary endpoints were AEs and laboratory abnormalities (using CTCAE 5.0 criteria) and best overall response (BOR) assessed by investigators based on RECIST v1.1. Secondary objectives were to further evaluate the PK of PF-06939999 at RP2D and its antitumor activity in NSCLC, UC, and HNSCC. Secondary endpoints were PK parameters and DoR based on RECIST v1.1.

Tumor assessment by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging took place at screening, every 8 weeks for the first 6 months, and then every 12 weeks.

Patient population

Patients were aged ≥18 years with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1 and adequate bone marrow, renal, and liver function.

For part 1, patients had a histologically or cytologically confirmed advanced/metastatic HNSCC, NSCLC, or endometrial, bladder, cervical, or esophageal cancer, and were resistant or intolerant to standard therapy, or for whom no standard therapy was available.

For part 2, patients had a histologically or cytologically confirmed locally advanced/metastatic NSCLC (part 2A), UC (part 2B), or HNSCC (part 2C) and received up to three lines of systemic therapies in the metastatic setting. Part 2A: with 2L+ NSCLC and progressed after at least one line of checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs) and one line of platinum-based chemotherapy or targeted therapies (EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF, or NTRK positive). Part 2B: with 2L+ UC and progressed after at least one line of standard-of-care chemotherapy and one line of CPIs. Part 2C: with 2L+ HNSCC and progressed after at least one line of standard-of-care systemic chemotherapy and one line of CPIs.

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics analysis

Part 1 included intense plasma PK sampling on cycle 1 day 1 (C1D1) and C1D15 to characterize single-dose and multiple-dose PK parameters for PF-06939999. Part 2 included sparse plasma PK sampling throughout the study. PK samples were analyzed using a validated analytical method.

PD assessments included measurement of plasma SDMA, a stable catabolic product of PRMT5 enzymatic activity, at specified timepoints (for details see footnote of Figure 1) throughout the study. Plasma SDMA level was measured using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC/MS) to monitor levels of PRMT5 inhibition in peripheral blood.

Figure 1.

PK and PD of PF-06939999. (A) Concentration–time profiles of PF-06939999 on day 1 and day 15 (geometric mean + SD, linear scale; PK concentration analysis set).a (B) Plasma SDMA levels over time after the first dose of PF-06939999.b

aSummary statistics were calculated by setting concentration values below the LLOQ (0.250 ng/ml) to zero. Error bars are not presented when n < 3.

bPF-06939999 activity on the PD biomarker SDMA was assessed by a plasma-based LC/MS assay.

For Part 1, samples for SDMA analysis were collected at pre-dose and 2 and 6 h post-dose C1D1; 12 h post-dose C1D1 or pre-dose C1D2; pre-dose C1D8; pre-dose and 2 and 6 h post-dose C1D15; and pre-dose C1D22, C2D1, and C3D1. For Part 2, samples were collected at pre-dose C1D1, C1D8, C1D15, C1D22, C2D1, C3D1, and EOT.

BID, twice daily;C, Cycle; D, Day; EOT, end of treatment; LLOQ, lower limit of quantification; PD, pharmacodynamics; PK, pharmacokinetics; QD, once daily; SDMA, symmetric dimethylarginine; Std, standard deviation.

Exploratory genomic, transcriptome, and predictive biomarker analysis

The purpose of the exploratory biomarker analysis was to investigate the correlation between clinical response and (i) the mutations of splicing factors or tumor driver genes, and (ii) a set of predefined RNA gene signatures as potential response-correlated biomarkers.

Whole-exome sequencing and mutation analysis

Mutation analysis was carried out using whole-exome sequencing (WES) focusing on a set of 119 splicing factor genes with missense mutations grouped into three categories: (i) all missense mutations, (ii) missense mutations with both high and moderate impact to function, and (iii) missense mutations with high impact to function. Results were compared between patients with potential clinical benefit (CB), defined as a BOR of complete response (CR), partial response (PR), or stable disease (SD) lasting ≥6 months, and those without CB (non-CB), defined as a BOR of progressive disease or SD lasting <6 months. ImmunoID NeXT (Personalis Inc, Fremont, CA) was adapted for generating WES data. Cut-offs for mutation calls were at variant allele frequency ≥0.05 and read depth ≥15 (https://www.personalis.com/technology/ace-technology/).

Transcriptome analysis

ImmunoID NeXT was used for generating whole-transcriptome sequencing data (https://www.personalis.com/products/immunoid-next/). RNAseq raw counts were used to measure differential gene expression between patients who had and did not have CB.

Statistical analyses

Dose escalation in part 1 was guided by a Bayesian analysis of cycle 1 DLT data for PF-06939999. Toxicity was modeled using two-parameter Bayesian logistic regression to estimate the probability of a patient experiencing DLT at a given dose. A dose could only be used for newly enrolled patients in part 1 if the risk of overdosing at that dose was <25%.

Clinical safety data (DLTs and AEs based on CTCAE 5.0) were summarized descriptively by dose levels. Tumor responses based on RECIST v1.1 were summarized descriptively by dose levels, and the Kaplan–Meier method was used to analyze all time-to-event endpoints.

Individual patient plasma PF-06939999 concentration–time data within a dose interval after C1D1 and C1D15 were analyzed using noncompartmental methods to determine single-dose and multiple-dose PK parameters. PK parameters were summarized descriptively by dose level, cycle, and day.

The RP2D selection was based on PK/PD modeling of plasma SDMA and thrombocytopenia as the main AE of concern, as described in detail by Guo et al.6

For the exploratory analysis of differential gene expression between patients having and not having CB, a cut-off of abs [log2(fold change)] >1.7 and P value <0.01 between the two groups was applied.

Results

Patient demographics, baseline disease characteristics, and disposition

A total of 54 patients were enrolled across 10 centers in the United States and received PF-06939999.

In part 1 dose escalation, 28 patients were enrolled across six tumor indications, including bladder cancer (n = 3), cervical carcinoma (n = 2), endometrial cancer (n = 10), NSCLC (n = 4), esophageal carcinoma (n = 2), and HNSCC (n = 7). The median (range) number of prior chemotherapies, immunotherapies, and targeted therapies was 2 (0-5), 1 (0-3), and 1 (0-4), respectively (Table 1). The median (range) duration of PF-06939999 treatment was 56.5 (20.0-337.0) days.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics (safety analysis set)

| Part 1 (N = 28) | Part 2 (N = 26) | Total (N = 54) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) years | 61.5 (32-84) | 67.0 (45-79) | 64.0 (32-84) |

| Male, n (%) | 13 (46) | 18 (69) | 31 (57) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 25 (89) | 19 (73) | 44 (82) |

| Black of African American | 3 (11) | 1 (4) | 4 (7) |

| Asian | 0 | 1 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Unknown | 0 | 5 (19) | 5 (9) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 22 (79) | 17 (65) | 39 (72) |

| Not reported | 0 | 3 (12) | 3 (6) |

| Primary cancer diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Endometrial | 10 (36) | 0 | 10 (19) |

| HNSCC | 7 (25) | 10 (39) | 17 (32) |

| NSCLC | 4 (14) | 14 (54) | 18 (33) |

| Bladder | 3 (11) | 2 (8) | 5 (9) |

| Cervical | 2 (7) | 0 | 2 (4) |

| Esophageal | 2 (7) | 0 | 2 (4) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 6 (32) | 5 (19) | 11 (20) |

| 1 | 22 (79) | 21 (81) | 43 (80) |

| Number of prior therapies, median (range) | 4 (1-16) | 3 (1-5) | 3 (1-16) |

| Number of prior chemotherapies, median (range) | 2 (0-5) | 2 (0-3) | 2 (0-5) |

| Number of immunotherapies, median (range) | 1 (0-3) | 1 (0-3) | 1 (0-3) |

| Number of targeted therapies, median (range) | 1 (0-4) | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-4) |

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer.

In part 2 dose expansion, 26 patients were enrolled across three tumor indications, including NSCLC (part 2A, n = 14), bladder cancer (part 2B, n = 2), and HNSCC (part 2C, n = 10). The median (range) number of prior chemotherapies, immunotherapies, and targeted therapies was 2 (0-3), 1 (0-3), and 0 (0-2), respectively (Table 1). The median (range) duration of PF-06939999 treatment was 57.5 (12.0-204.0) days.

All patients discontinued PF-06939999 treatment due to progressive disease/disease relapse [31 (57%) patients], AEs [6 (11%) patients], or for other reasons. Thirty-five (65%) patients discontinued the study during the follow-up phase due to death [13 (24%) patients], withdrawal of consent [6 (11%) patients], or for other reasons (Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102961).

Part 1 dose escalation

DLT and clinical safety

In part 1, 28 patients were enrolled at nine doses: 0.5 mg q.d. (n = 1), 0.5 mg b.i.d. (n = 1), 1 mg b.i.d. (n = 2), 2 mg b.i.d. (n = 3), 4 mg b.i.d. (n = 3), 6 mg b.i.d. (n = 4), 8 mg q.d. (n = 3), 6 mg q.d. (n = 6), and 4 mg q.d. (n = 5). Twenty-four (86%) patients in part 1 were assessable for DLTs, and 4/24 (17%) reported DLTs including grade 3 and grade 4 thrombocytopenia (n = 1 each) in the 6-mg b.i.d. cohort, grade 3 anemia (n = 1) in the 8-mg q.d. cohort, and grade 3 neutropenia (n = 1) in the 6-mg q.d. cohort (Table 2).

Table 2.

DLTs and grade 3 or higher TRAEs by dose level in part 1 (per-protocol and safety analysis sets, respectively)

| 0.5 mg q.d. | 0.5 mg b.i.d. | 1 mg b.i.d. | 2 mg b.i.d. | 4 mg b.i.d. | 6 mg b.i.d. | 8 mg q.d. | 6 mg q.d. | 4 mg q.d. | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLTa | ||||||||||

| N | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 24 |

| n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (100) | 1 (33) | 1 (17) | 0 | 4 (17) |

| Grade ≥3 TRAEb | ||||||||||

| N | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 28 |

| Anemia, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (50) | 0 | 1 (33) | 1 (25) | 1 (33) | 2 (33) | 2 (40) | 8 (28) |

| Thrombocytopenia, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 2 (50) | 2 (67) | 0 | 0 | 6 (21) |

| Fatigue, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33) | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 2 (7) |

| Neutropenia, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Lymphocyte count decreased, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (33) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Muscular weakness, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (20) | 1 (4) |

AE, adverse event; b.i.d., twice daily; DLT, dose-limiting toxicity; q.d., once daily; TRAE, treatment-related adverse event.

A patient was classified as having a DLT if they met any of the following criteria: reported AE DLT on the AE page in the first 28 days of treatment; had a dose reduction due to an AE reported during the first 28 days of treatment; or had consecutive dose interruption for >2 weeks in the first 28 days of treatment.

Patients were only counted once per treatment per event in each row according to the maximum CTCAE v5 grade. MedDRA v25.0 coding dictionary was applied.

All 28 (100%) patients in part 1 reported at least one all-causality treatment-emergent AE (TEAE) of any grade; the most frequent (≥20% of patients) were fatigue (50%), anemia (46%), nausea (39%), thrombocytopenia (36%), dysgeusia (32%), dyspnea and decreased appetite (29% each), and vomiting (21%) (Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102961).

In part 1, any-grade treatment-related AEs (TRAEs) were reported in 24 (86%) patients, and grade ≥3 TRAEs were reported in 12 (43%) patients. The most frequent (≥10% of patients) TRAEs of any grade were anemia (43%); dysgeusia, fatigue, and thrombocytopenia (32% each); nausea (29%); decreased appetite (21%); hypomagnesemia (14%); and leukopenia and neutropenia (11% each). Grade 3 or higher TRAEs in more than one patient included anemia (n = 8, 29%), thrombocytopenia (n = 6, 21%), and fatigue (n = 2, 7%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

TRAEs reported in ≥10% of patients in part 1 or part 2 (safety analysis set)

| Part 1 N = 28 |

Part 2 N = 26 |

Total N = 54 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade ≥3a | Any grade | Grade ≥3a | Any grade | Grade ≥3a | |

| Any | 24 (86) | 12 (43) | 21 (81) | 11 (42) | 45 (83) | 23 (43) |

| Anemia | 12 (43) | 8 (29) | 11 (42) | 7 (27) | 23 (43) | 15 (28) |

| Dysgeusia | 9 (32) | 0 | 3 (12) | 0 | 12 (22) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 9 (32) | 2 (7) | 6 (23) | 1 (4) | 15 (28) | 3 (6) |

| Thrombocytopeniab | 9 (32) | 6 (21) | 13 (50) | 6 (23) | 22 (41) | 12 (22) |

| Nausea | 8 (29) | 0 | 9 (35) | 0 | 17 (32) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 6 (21) | 0 | 7 (27) | 0 | 13 (24) | 0 |

| Hypomagnesemia | 4 (14) | 0 | 1 (4) | 0 | 5 (9) | 0 |

| Leukopenia | 3 (11) | 0 | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 5 (9) | 1 (2) |

| Neutropenia | 3 (11) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 4 (7) | 2 (4) |

| Dyspepsia | 2 (7) | 0 | 4 (15) | 0 | 6 (11) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 1 (4) | 0 | 3 (12) | 0 | 4 (7) | 0 |

| Weight decreased | 0 | 0 | 3 (12) | 0 | 3 (6) | 0 |

Values are presented as n (%) of patients. Patients are only counted once per treatment per event in each row according to the maximum CTCAE v5 grade. MedDRA v23.1 coding dictionary was applied.

b.i.d., twice daily; q.d., once daily; TRAE, treatment-related adverse event.

No grade 5 TRAEs were reported. One patient in the 6-mg b.i.d. cohort (part 1) reported a grade 4 TRAE of thrombocytopenia. One patient with NSCLC (part 2A) and one with HNSCC (part 2C) who received 6 mg q.d. reported grade 4 TRAEs of thrombocytopenia/platelet count decreased.

Including thrombocytopenia and platelet count decreased.

Pharmacokinetics and SDMA PD biomarker

Plasma PF-06939999 concentration–time profiles following a single oral dose on C1D1 and multiple oral doses on C1D15 are presented in Figure 1A. Following single and multiple oral doses, PF-06939999 was absorbed rapidly, with a median time to maximum plasma concentration (Tmax) of 0.5-2.1 h. Both the area under the plasma concentration–time curve over the dosing interval (from time 0 to time τ) (AUCτ) and the maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmax) increased in a dose-dependent manner. Following b.i.d. dosing, the geometric mean of the observed accumulation ratio based on AUCτ (Rac) was 7.1, indicating effective half-life >24 h. Together with low peak-to-trough ratio, the dosing regimen was switched from b.i.d. to q.d. for patient convenience during part 1 dose escalation. Steady state was achieved by day 15 for both b.i.d. and q.d. regimens. The variability at the RP2D, 6 mg q.d., was moderate (38% for AUCτ and 26% for Cmax) (Figure 1A, Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102961).

PD activity of PF-06939999 was assessed using an LC/MS assay to measure plasma SDMA levels. Previous preclinical mouse SW1990 and A427 xenograft models indicated that a 70% (or greater) inhibition of plasma SDMA corresponded to ∼100% tumor growth inhibition (data not shown). Clinically, ∼60% plasma SDMA inhibition was observed 14-28 days post-dose of PF-06939999 (0.5 mg q.d. or b.i.d.), and 70%-80% inhibition was achieved at subsequent doses of 1-8 mg (q.d. and/or b.i.d.) (Figure 1B), without a clear dose dependency. These data suggested that robust blood PD (plasma SDMA) inhibition was achieved at ≥1 mg daily dose.

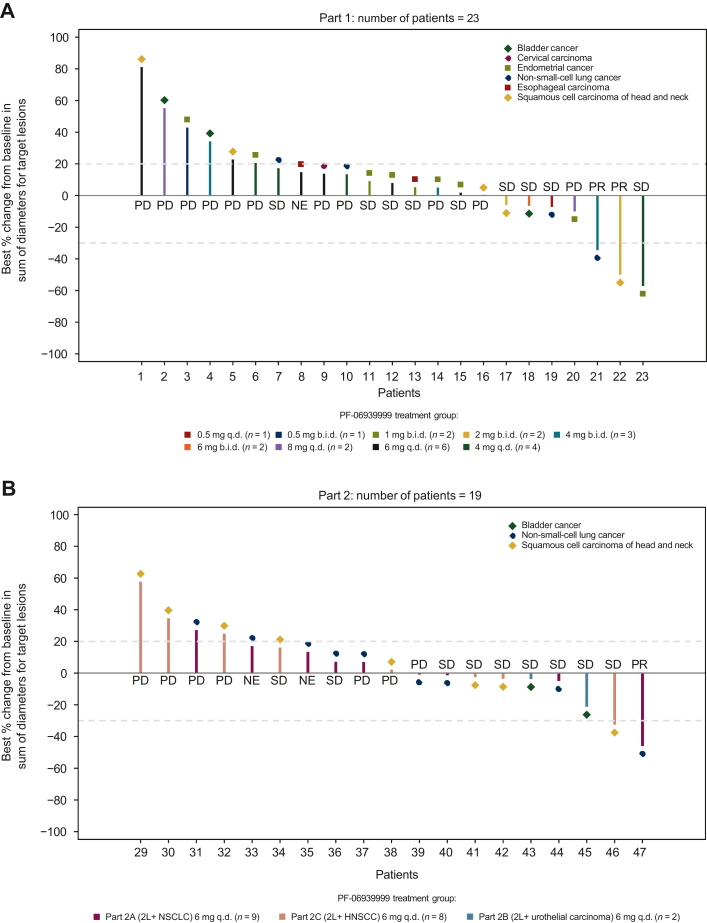

Clinical efficacy

Twenty-eight patients were treated with 22 patients assessable for clinical response based on RECIST v1.1. Two (7%) patients had confirmed PRs: one with HNSCC who received 2 mg b.i.d. and one with NSCLC who received 4 mg b.i.d. (Figure 2). The DoRs for these confirmed responders were 4 and 5 months, respectively (Figure 2). Of these two patients, the one with NSCLC harbored potential driver mutations of KRAS Q61L, BRAF G469V, and ING4 splicing variant (associated with regulation of cell growth and motility) and the one with HNSCC had NOTCH1 and CYLD mutations, both genes are potential tumor suppressors in HNSCC and regulate tumor cell growth and proliferation.7,8 Nine patients (32%) had SD, 11 (39%) had progressive disease, and 6 (21%) were not assessable. In total, 11 (39%) patients achieved disease control (CR + PR + SD + non-CR/non-progressive disease), and 3 (11%) patients had SD ≥6 months.

Figure 2.

Tumor response in the response-evaluable analysis set and duration of treatment in the safety analysis set. (A, B) Best percentage change from baseline in sum of diameters for target lesions.a (C, D) Duration of treatment.b aOnly included patients of the response-assessable population, defined as all patients who received at least one dose of PF-06939999 and had baseline disease assessment or measurable disease at baseline, and at least one post-baseline disease assessment. The response-assessable population included 44 patients with assessments of target lesions at baseline and at least one nonmissing post-baseline percentage change from baseline assessment up to the time of progressive disease or new anticancer therapy. Of the 44 patients, 2 patients in part 2A (2L+ NSCLC 6 mg q.d. PF-06939999 treatment group) did not have all target lesions assessed at post-baseline, and the post-baseline percentage change in tumor size from baseline did not meet the ≥20% criteria; therefore, they were considered as not assessable and excluded in the waterfall plots. Tumor response was based on investigator assessment using RECIST v1.1. bDuration was from the first to the last day (inclusive) of each study treatment. PR, SD, and progressive disease were based on investigator assessment. The number included in each label of the y-axis of panels C and D is patient ID. 2L+ NSCLC, patients with NSCLC who had progressed after at least one line of checkpoint inhibitors and one line of platinum-based chemotherapy; BC, bladder cancer; b.i.d., twice daily; CC, cervical carcinoma; ECM, metastatic endometrial cancer; ENDC, endometrial cancer; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; LA, lung adenocarcinoma; LC/MS, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry; MSCC, metastatic squamous cell carcinoma; NE, not evaluable; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; EC, esophageal carcinoma; PR, partial response; q.d., once daily; SCCL, squamous cell carcinoma of the lung; SD, stable disease; UC, urothelial carcinoma.

RP2D selection

According to the DLT rates at different dose levels and Bayesian logistic regression design, MTD was not reached. The RP2D of 6 mg q.d. was selected based on mechanistic PK/PD modeling of plasma SDMA (the clinically relevant biomarker for target engagement) and thrombocytopenia (the main AE of concern). The probabilities of reaching the target PD effect (i.e. 78% reduction in plasma SDMA) and of developing grade ≥3 thrombocytopenia were simulated for different dose levels. Simulations suggested that plasma SDMA inhibition plateaued above 4 mg q.d., whereas the platelet count nadir continued to drop with further increase in dose. Compared with 6 mg q.d., the 8-mg q.d. dosage would provide minimal incremental benefit of SDMA inhibition while resulting in an undesirable probability (>40%) of developing grade ≥3 thrombocytopenia. Therefore, 6 mg q.d. was considered to offer the maximum benefit-to-risk ratio for patients.6 In addition, the median predicted exposure at 6 mg q.d. was within the range of exposure at which the two PRs were observed, serving as supportive evidence given the limited sample size.

Part 2 dose expansion

Clinical safety

In part 2 dose expansion, 26 patients were enrolled across three tumor indications, including NSCLC (part 2A, n = 14), bladder cancer (part 2B, n = 2), and HNSCC (part 2C, n = 10).

All 26 (100%) patients in part 2 reported at least one all-causality TEAE of any grade, and 23 (88%) reported grade ≥3 TEAEs. The most frequent (≥20% of patients) all-causality TEAEs of any grade were thrombocytopenia (54%), anemia and nausea (42% each), fatigue and decreased appetite (35% each), and hypomagnesemia (23%) (Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102961).

Any-grade TRAEs were reported in 21 (81%) patients, and grade ≥3 TRAEs were reported in 11 (42%) patients. The most frequent (≥10% of patients) TRAEs of any grade were thrombocytopenia/platelet count decreased (50%), anemia (42%), nausea (35%), decreased appetite (27%), fatigue (23%), dyspepsia (15%), and dysgeusia, vomiting, and weight decreased (12% each). Grade 3 or higher TRAEs in more than one patient included anemia (n = 7, 27%) and thrombocytopenia/platelet count decreased (n = 6, 23%) (Table 3).

Duration of treatment, dose modification, and dose intensity

The median (range) duration of treatment for part 2 in total was 57.5 (12.0-204.0) days. For part 2A, 2B, and 2C, the median (range) duration of treatment was 46.5 (12.0-204.0), 125.5 (82.0-169.0), and 62.5 (15.0-177.0) days, respectively. Twenty-one (81%) patients had ≥1 dose interruption due to AEs. Eight (31%) patients had ≥1 dose reduction due to AEs. The most frequent AEs leading to dose reduction were anemia [5 (19%) patients] and thrombocytopenia [4 (15%) patients]. The median (interquartile range) relative dose intensity was 85.9% (53.3%-93.5%).

Clinical efficacy

Twenty-six patients were treated with 19 patients assessable for response based on RECIST v1.1. One patient (4%) with NSCLC who received PF-06939999 6 mg q.d. had confirmed PR (Figure 2). Ten (38%) patients had SD, 8 (31%) had progressive disease, and 7 (27%) were not assessable. In total, 11 (42% %) patients achieved disease control, and 1 (4%) patient had SD ≥6 months.

Genome, transcriptome, and exploratory predictive biomarker analysis

Patients enrolled in this study had solid tumors (HNSCC, NSCLC, or bladder, esophageal, cervical, or endometrial cancers) that were known to carry the highest frequencies of mutations with potential loss-of-function properties on 119 splicing factor genes. Considering PRMT5 inhibitors may be more efficacious in tumor types with dysregulated alternative splicing caused by mutations in splicing factors, the potential relationship between CB of PF-06939999 and splicing factor mutation status was explored in patients who had CB (NSCLC, n = 3; HNSCC, n = 3), defined as a BOR of CR, PR, or SD lasting ≥6 months, or did not have CB (NSCLC, n = 7; HNSCC, n = 10), defined as a BOR of progressive disease or SD lasting <6 months (Supplementary Table S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102961).

The association of splicing factor mutations (high-impact mutation) with CB showed a nonsignificant trend in patients with NSCLC but not in patients with HNSCC (Supplementary Table S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102961). All three patients with NSCLC who had CB had more than one splicing factor mutation with high/moderate impact to function. The only patient with HNSCC who had a PR did not have a splicing factor mutation with high/moderate impact to function.

WES data from 38 patients (CB, n = 6; non-CB, n = 32) were analyzed to evaluate the potential association between CB and driver mutation status. There was no correlation between 115 driver mutations (e.g. RBM10, TP53, ARID1A, KDM5A, KDM6A, KMT2C, KMT2D, and KRAS) and CB (all P > 0.1, data not shown). Furthermore, while an association between efficacy of PRMT5 inhibition and MTAP deletion has been documented,9 no MTAP deletion was observed in the current study to conduct the correlation analysis.

RNAseq analysis identified a 731 differentially expressed gene signature between patients with CB and those without CB. An upstream regulator analysis of RNAseq data using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (https://digitalinsights.qiagen.com/products-overview/discovery-insights-portfolio/analysis-and-visualization/qiagen-ipa/) suggested that tumor necrosis factor-α, lipopolysaccharide, interleukin (IL)-33, and IL-1β were key regulators of the gene signature that was up-regulated in patients with CB. Consistent with these results, patients with CB had higher inflammation-associated signature scores than patients without CB using three published inflammation-related gene signatures: (i) a pan-cancer predictive gene expression profile associated with T-cell-related inflammation,10 (ii) a dendritic cell-associated gene signature,11 and (iii) a natural killer cell-related gene signature.11 However, the correlation between CB and inflammation-related gene signatures was not statistically significant (Supplementary Figure S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.102961).

Discussion

PF-06939999 demonstrated dose-dependent and manageable toxicities and antitumor activity in this phase I dose-escalation and -expansion study in patients with selected advanced/metastatic solid tumors. PF-06939999 6 mg q.d. was chosen as the RP2D based on part 1 safety, antitumor activity, and clinical PK and PD (plasma SDMA) data, using a PK/PD modeling approach. PK/PD simulations suggested that 6 mg q.d. could be safely administered (staying below an acceptable probability of developing grade ≥3 thrombocytopenia6) while achieving the target PD effect (78% reduction in plasma SDMA) with high probability.

In the current study, the most common (≥20%) TRAEs were anemia (43%), thrombocytopenia (41%), nausea (32%), fatigue (28%), decreased appetite (24%), and dysgeusia (22%), whereas the most common grade ≥3 TRAEs (≥10%) were anemia (28%) and thrombocytopenia/platelet count decreased (22%). Hematological toxicities were reversible, dose dependent, and were managed by dose interruption and reduction. Similar type and incidence of TRAEs were reported in studies of the PRMT5 inhibitor GSK3326595 in patients with advanced solid tumors (fatigue, 39%; anemia, 31%; nausea, 31%; and dysgeusia, 26%)12 and the PRMT5 inhibitor JNJ-64619178 in patients with advanced solid tumors, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, or lower-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (thrombocytopenia, 52%; anemia, 19%-41%; nausea, 39%; fatigue, 32%; and dysgeusia, 14%-30%).13,14 These observations demonstrate that PF-06939999 had a comparable safety profile to other PRMT5 inhibitors currently in development and suggest that some TRAEs (e.g. thrombocytopenia, anemia, nausea, fatigue, and dysgeusia) may reflect effects of the drug class.

In the current study, confirmed PRs were observed in 3/54 patients (including 2 patients with NSCLC and 1 patient with HNSCC) for an objective response rate of 6%. In total, 22/54 (41%) patients achieved the protocol-specified definition of disease control (CR + PR + SD + non-CR/non-progressive disease), and 4/54 (7%) patients had SD ≥6 months. Preliminary evidence of antitumor activity was also demonstrated in studies of JNJ-64619178 and GSK3326595 with patients achieving PRs.12,14

As only a small subset of patients in the current study achieved objective response, genome and transcriptome analyses were carried out to investigate the potential relationship between mutation status and non-progressive disease. Genomic analysis demonstrated an association of high-impact splicing factor mutations with disease control in patients with NSCLC, but the finding was exploratory and did not meet statistical significance. Furthermore, no correlation was observed when the analysis was extended to a list of 115 key driver mutation genes. Although several recent publications suggested a correlation between MTAP deletion and response to PRMT5 inhibition,9,15, 16, 17, 18 no MTAP deletion was observed in the limited dataset of the current study; therefore, a correlation analysis could not be conducted.

Transcriptome analysis identified an inflammation-related gene signature (i.e. the 18-gene T-cell-related inflammation-associated signature10) that is up-regulated in patients with potential CB; however, the correlation between this inflammation-related gene signature and CB was not statistically significant.

Overall, although the prior hypothesis and preclinical evidence showed that cancer cells with splicing factor mutations and MTAP deficiency were more sensitive to PRMT5 inhibition, we were not able to confirm preclinical findings in the clinical setting. In addition, we have not identified statistically significant, novel, predictive clinical biomarkers associated with potential CB in solid tumors from the phase I clinical trial. These findings suggest that although PRMT5 is an interesting cancer target with clinical validation in a subset of cancer patients, the role of PRMT5 in cancer biology remains complex in a context-dependent fashion and requires further mechanistic investigation to identify predictive biomarkers for patient selection.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in a phase I clinical study, PF-06939999, a selective small-molecule PRMT5 inhibitor, demonstrated a tolerable and manageable safety profile and dose-dependent increase in exposure. MTD was not identified in this study, and 6 mg q.d. was determined to be the RP2D based on integrated PK/PD and clinical safety analyses, with potent PD plasma SDMA inhibition around 80%. During dose escalation and expansion, confirmed PRs were observed in a subset of patients with HNSCC and NSCLC. From exploratory genome and transcriptome analyses, no statistically significant, predictive biomarkers were identified in the phase I study. These findings suggest that PRMT5 is an interesting cancer target with clinical validation in a small subset of patients. However, the role of PRMT5 in cancer biology remains complex and requires further preclinical mechanistic investigation to identify predictive biomarkers for patient selection.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledged all study investigators, Pfizer study team, and participants. The authors thank Tao Xie, Pfizer, for bioinformatic support, and Kristen Jensen-Pergakes, Pfizer, for making suggestions about the figure of mechanism of action of PF-06939999. Medical writing support was provided by Elyse Smith, PhD, CMPP, and Shuang Li, PhD, CMPP, of Engage Scientific Solutions and was funded by Pfizer.

Funding

This work was supported by Pfizer (no grant number). Medical writing support was provided by Engage Scientific Solutions and was funded by Pfizer (no grant number). Employees of the funding source were involved in the study design, data collection and analysis, and reviewing of the manuscript as co-authors. All authors had access to the study data, were involved in data interpretation, drafted and provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final version for submission and publication.

Disclosure

JRA: consulting or advisory role: AADi, Avoro Capital Advisors, Boxer Capital, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Clarion Healthcare, Columbus Venture Partners, Cullgen, Debiopharm Group, Ellipses Pharma, Envision Pharma Group, iOnctura, Macrogenics, Merus, Monte Rosa Therapeutics, Monte Rosa Therapeutics, Oncology One, Pfizer, Sardona Therapeutics, Tang Advisors, and Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology/Ministerio De Empleo Y Seguridad Social. Research funding: AADi (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Bicycle Therapeutics (Inst), BioAtla (Inst), BioMed Valley Discoveries (Inst), Black Diamond Therapeutics (Inst), Blueprint Medicines (Inst), Cellestia Biotech (Inst), Curis (Inst), CytomX Therapeutics (Inst), Deciphera (Inst), Fore Biotherapeutics (Inst), Genmab (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Hummingbird (Inst), Hutchison MediPharma (Inst), IDEAYA Biosciences (Inst), Kelun (Inst), Linnaeus Therapeutics (Inst), Loxo (Inst), Merck Sharp & Dohme (Inst), Merus (Inst), Mirati Therapeutics (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Nuvation Bio (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Roche (Inst), Spectrum Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Symphogen (Inst), Taiho Pharmaceutical (Inst), Takeda/Millennium (Inst), Tango Therapeutics (Inst), Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology/Cancer Core Europe (Inst), and Yingli Pharma (Inst). Travel, accommodations, expenses: ESMO. Other relationship: Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology/Ministerio De Empleo Y Seguridad Social. ER: consulting or advisory role: Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation, Janssen Oncology, Novartis, Oncocyte, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Research to Practice. MLM: consulting or advisory role: Acceleron Pharma, Actelion/Janssen, Gossamer Bio, Reata Pharmaceuticals, and United Therapeutics. Research funding: AstraZeneca (Inst) and Pfizer (Inst). FYCT: stock and other ownership interests: Salarius Pharmaceuticals. Consulting or advisory role: Aptitude Health and Tempus. Patents, royalties, other intellectual property: Clinical trial software. MAS: honoraria: Arcus Biosciences, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Coherus Biosciences, G1 Therapeutics, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Gritstone Bio, Guardant Health, Janssen Oncology, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Lilly, Merck, Mirati Therapeutics, Novartis, Regeneron, Roche/Genentech, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda. Consulting or advisory role: Genentech, Janssen, Lilly, and Spectrum Pharmaceuticals. Speakers’ bureau: Amgen, AstraZeneca, Blueprint Medicines, Bristol-Myers Squibb, G1 Therapeutics, Genentech, Guardant Health, Janssen Oncology, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Lilly, Merck, Sanofi/Regeneron, and Takeda. Research funding: AstraZeneca/MedImmune (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo/Astra Zeneca (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Mirati Therapeutics (Inst), and Spectrum Pharmaceuticals (Inst). JDB: consulting or advisory role: Bayer Health, Bexion, BioSapien, insmed, ipsen, Merck KGaA, Merus, Mirati Therapeutics, and Oxford BioTherapeutics. Research funding: 23andMe (Inst), Abbvie (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Atreca (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb/Celgene (Inst), Day One Biopharmaceuticals (Inst), Dragonfly Therapeutics (Inst), EMD Serono (Inst), hibercell (Inst), I-MAB (Inst), Incyte (Inst), Karyopharm Therapeutics (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), PsiOxus Therapeutics (Inst), Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Oncology (Inst), Totus Medicines (Inst), and Tyra Biosciences (Inst). Other relationship: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and novocure. TAB: stock and other ownership interests: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Epizyme, and HERON. Honoraria: Cardinal Health. Consulting or advisory role: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cardinal Health, Genentech/Roche, Kite, a Gilead company, and Lilly. AWT: employment: Next Oncology. Leadership: Next Oncology. Stock and other ownership interests: Pyxis. Consulting or advisory role: AbbVie, Aclaris Therapeutics, Adagene, Agenus, Aro Biotherapeutics, Asana Biosciences, Ascentage Pharma, Aximmune, Bayer, BioInvent, BluPrint Oncology, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bright Peak Therapeutics, Daiichi Sankyo Inc, Deka Biosciences, Eleven Biotherapeutics, Elucida Oncology, EMD Serono, Gilde Healthcare, HBM Partners, HiberCell, IDEA Pharma, Ikena Oncology, Immuneering, Immunome, Immunomet, IMPAC Medical Systems, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Karma Oncology, Kirilys Therapeutics, Lengo Therapeutics, Lilly, Link Immunotherapeutics, Mekanistic Therapeutics, Menarini, Mersana, Mirati Therapeutics, Nanobiotix, NBE Therapeutics, Nerviano Medical Sciences, Novo Nordisk, Nurix, Ocellaris Pharma, Partner Therapeutics, Pelican Therapeutics, Pfizer, Pieris Pharmaceuticals, Pierre Fabre, Pyxis, Qualigen Therapeutics, Roche, Ryvu Therapeutics, Seagen, Senti Biosciences, SK Life Sciences, Sotio, Spirea, Sunshine Guojian, Transcenta, Transgene, Trillium Therapeutics, Verastem, Vincerx Pharma, VRise Therapeutics, Zentalis, ZielBio, and Zymeworks. Research funding: AbbVie, ABL Bio, Adagene, ADC Therapeutics, Agenus, Aminex, Amphivena, Apros Therapeutics, Arcellx, ARMO BioSciences, Arrys Therapeutics, Artios, Asana Biosciences, Ascentage Pharma, Astex Pharmaceuticals, Basilea, Bioinvent, Birdie, BJ Bioscience, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Biomedical, CStone Pharmaceuticals, Daiichi Sankyo Inc, Deciphera, eFFECTOR Therapeutics, EMD Serono, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, ImmuneOncia, Inhibrx, Innate Pharma, Janssen Research & Development, K-Group Beta, Kechow Pharma, Kiromic, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Mersana, Mirati Therapeutics, Naturewise, NBE Therapeutics, NextCure, Nitto BioPharma, Odonate Therapeutics, ORIC Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Pieris Pharmaceuticals, Qilu Puget Sound Biotherapeutics, Samumed, Seagen, Shanghai HaiHe Pharmaceutical, Spring Bank, Sunshine Guojian, Symphogen, Syndax, Synthorx, Takeda, Tizona Therapeutics Inc, and Zymeworks. Expert testimony: Immunogen. Travel, accommodations, expenses: Sotio. MG: stock and other ownership interests: Pfizer. IMW, CG, MG, LNC, and ML: employment: Pfizer. Stock and other ownership interests: Pfizer. JST has declared no conflicts of interest.

Data sharing

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions, and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Stopa N., Krebs J.E., Shechter D. The PRMT5 arginine methyltransferase: many roles in development, cancer and beyond. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72(11):2041–2059. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1847-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen-Pergakes K., Tatlock J., Maegley K.A., et al. SAM-competitive PRMT5 inhibitor PF-06939999 demonstrates antitumor activity in splicing dysregulated NSCLC with decreased liability of drug resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2022;21(1):3–15. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dvinge H., Kim E., Abdel-Wahab O., Bradley R.K. RNA splicing factors as oncoproteins and tumour suppressors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(7):413–430. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seiler M., Peng S., Agrawal A.A., et al. Somatic mutational landscape of splicing factor genes and their functional consequences across 33 cancer types. Cell Rep. 2018;23(1):282–296.e284. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.01.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodon J., Perez C.A., Wong K.M., et al. PF-06939999, a potent and selective PRMT5 inhibitor, in patients with advanced or meta-static solid tumors: a phase 1 dose escalation study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:3019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo C., Liao K.H., Li M., et al. PK/PD model-informed dose selection for oncology phase I expansion: case study based on PF-06939999, a PRMT5 inhibitor. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2023;12(11):1619–1625. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sambandam V., Frederick M.J., Shen L., et al. PDK1 mediates NOTCH1-mutated head and neck squamous carcinoma vulnerability to therapeutic PI3K/mTOR inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(11):3329–3340. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui Z., Kang H., Grandis J.R., Johnson D.E. CYLD alterations in the tumorigenesis and progression of human papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancers. Mol Cancer Res. 2021;19(1):14–24. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-20-0565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalev P., Hyer M.L., Gross S., et al. MAT2A inhibition blocks the growth of MTAP-deleted cancer cells by reducing PRMT5-dependent mRNA splicing and inducing DNA damage. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(2):209–224.e211. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayers M., Lunceford J., Nebozhyn M., et al. IFN-γ-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(8):2930–2940. doi: 10.1172/JCI91190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barry K.C., Hsu J., Broz M.L., et al. A natural killer-dendritic cell axis defines checkpoint therapy-responsive tumor microenvironments. Nat Med. 2018;24(8):1178–1191. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0085-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siu L.L., Rasco D.W., Vinay S.P., et al. METEOR-1: a phase I study of GSK3326595, a first-in-class protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) inhibitor, in advanced solid tumours. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:v159–v193. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haque T., Cadenas F.L., Xicoy B., et al. Phase 1 study of JNJ-64619178, a protein arginine methyltransferase 5 inhibitor, in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2021;138:2606. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2023.107390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villar M.V., Spreafico A., Moreno V., et al. First-in-human study of JNJ-64619178, a protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) inhibitor, in patients with advanced cancers. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S462–S504. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Busacca S., Zhang Q., Sharkey A., et al. Transcriptional perturbation of protein arginine methyltransferase-5 exhibits MTAP-selective oncosuppression. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):7434. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86834-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engstrom L.D., Aranda R., Waters L., et al. MRTX1719 is an MTA-cooperative PRMT5 inhibitor that exhibits synthetic lethality in preclinical models and patients with MTAP deleted cancer. Cancer Discov. 2023;13(11):2412–2431. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-23-0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fedoriw A., Rajapurkar S.R., O’Brien S., et al. Anti-tumor activity of the type I PRMT inhibitor, GSK3368715, synergizes with PRMT5 inhibition through MTAP loss. Cancer Cell. 2019;36(1):100–114.e125. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kryukov G.V., Wilson F.H., Ruth J.R., et al. MTAP deletion confers enhanced dependency on the PRMT5 arginine methyltransferase in cancer cells. Science. 2016;351(6278):1214–1218. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.