Abstract

The oncogene Aurora kinase A (AURKA) has been implicated in various tumor, yet its role in meningioma remains unexplored. Recent studies have suggested a potential link between AURKA and ferroptosis, although the underlying mechanisms are unclear. This study presented evidence of AURKA upregulation in high grade meningioma and its ability to enhance malignant characteristics. We identified AURKA as a suppressor of erastin-induced ferroptosis in meningioma. Mechanistically, AURKA directly interacted with and phosphorylated kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1), thereby activating nuclear factor erythroid 2 related factor 2 (NFE2L2/NRF2) and target genes transcription. Additionally, forkhead box protein M1 (FOXM1) facilitated the transcription of AURKA. Suppression of AURKA, in conjunction with erastin, yields significant enhancements in the prognosis of a murine model of meningioma. Our study elucidates an unidentified mechanism by which AURKA governs ferroptosis, and strongly suggests that the combination of AURKA inhibition and ferroptosis-inducing agents could potentially provide therapeutic benefits for meningioma treatment.

Keywords: Meningioma, Ferroptosis, Protein kinase, AURKA, NRF2

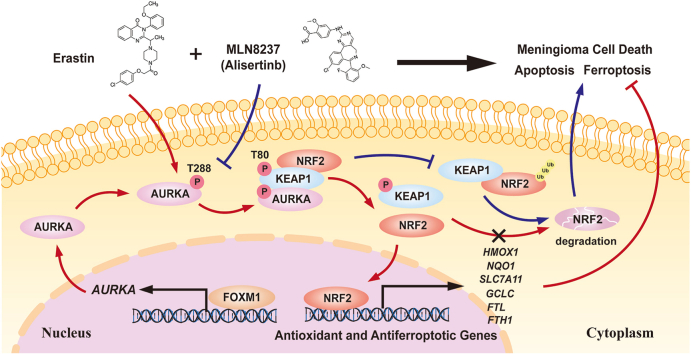

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Meningioma is the most prevalent primary central nervous system (CNS) tumor [1]. The 2021 WHO classification for grading CNS tumors categorizes meningiomas into 15 histological subtypes, ranging from WHO grade I to III. Surgical resection typically yields satisfactory outcomes in WHO grade I cases. However, 20% of meningiomas are classified as high-grade tumors (WHO grade II and III), demonstrate more aggressive biological behavior and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality in affected individuals [2]. The inadequate chemotherapeutic options and absence of targeted therapies have led to exceedingly unfavorable prognoses for patients afflicted with aggressive meningiomas, particularly those harboring WHO grade III tumors [3]. It is imperative to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying meningioma progression in order to facilitate the development of molecularly guided therapeutic interventions for meningioma.

Ferroptosis is an unconventional process of cellular demise induced by erastin, resulting in the reduction of glutathione and the deactivation of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), characterized by unrestricted accumulation of lipid peroxidation, dependent on iron, and subsequent rupture of the plasma membrane [4]. Exploiting ferroptosis have been shown potential as a viable approach in the treatment of cancer [5]. Numerous defense mechanisms have been discovered to counteract ferroptosis, thereby conferring resistance to this form of cell death. Among these mechanisms, one notable factor is NRF2 [5]. NRF2 is a crucial regulator of oxidative stress signaling, its expression and activation are controlled through various mechanisms, including transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and post-translational regulation. Our research group previously showed that the use of erastin to induce ferroptosis holds great potential as a molecular approach to target meningiomas. In meningioma cells, the transcription factor MEF2C upregulates the expression of NF2 and E-cadherin, thereby inhibiting erastin-induced ferroptosis [6]. However, the mechanisms that mediate the regulation of ferroptosis in meningiomas are still poorly understood.

AURKA, a member of the highly conserved serine/threonine kinases known as Aurora kinases, of which canonical function is regulating cell division during mitosis [7,8]. Overexpression of AURKA has been detected in different cancer forms, such as ovarian, colorectal, gastric, and hematological malignancies [9]. Recent studies have provided evidence indicating that AURKA might play a part in governing the process of ferroptosis [10,11]. Furthermore, the overexpression of AURKA was found to partially counteract the ferroptosis induced by Ophiopogonin B in NSCLC [12]. Nevertheless, the involvement of AURKA in meningioma progression and its mechanistic role in the regulation of ferroptosis are still undisclosed.

In this study, we noticed that AURKA exhibited upregulation in higher-grade meningiomas and facilitated malignancy of meningioma. AURKA bound to and phosphorylated KEAP1, hindering the interaction between KEAP1 and NRF2, thereby activating NRF2 and the expression of downstream anti-ferroptotic genes in meningioma. Additionally, FOXM1 acted as a transcriptional factor for AURKA. We also evaluated the potential therapeutic effects of combination of AURKA inhibition and ferroptosis induction in meningioma models.

2. Materials & methods

2.1. Tumor samples and datasets

Data related to transcription and clinical information were acquired from the official website of the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Clinical samples were obtained from the Department of Neurosurgery at the first affiliated hospital of Nanjing Medical University. Tumor tissues were collected during surgical procedures, promptly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and preserved at −80 °C until extraction of RNA and protein. Supplementary Table 1 lists the clinical information of the cohort.

2.2. Cell lines and cell culture

IOMM-Lee and CH157MN human meningioma cell lines were kindly given by Professor Wan's laboratory at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, FL. Both the meningioma cell lines were cultured in DMEM-F12 medium (Gibco, 11320033) containing 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Sigma) as a supplement. HEK293T cells were obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China) and were cultured according to the established procedure. The advanced stable cell line of HEK293T Tet-OFF Myc-AURKA and different NRF2 variants were generated by Corues Biotechnology, China. Indicated cell culture medium was supplemented with 1 μg/μl of Dox to block Myc-AURKA expression.

2.3. Antibodies and chemicals

For the Western blot (WB), immunoprecipitation (IP), immunohistochemistry (IHC), and immunofluorescence (IF) analyses: the following antibodies were utilized at the indicated dilutions: AURKA (ab52973, Abcam, 1:10000 for WB, 1:200 for IHC, 1:50 for IP), AURKA (ab13824, Abcam, 1:200 for IF), p-AURKA (3079, Cell signaling, 1:1000 for WB), NRF2 (16396-1-AP, Proteintech, 1:5000 for WB, 1:100 for IHC, 1:200 for IF), KEAP1 (10503-2-AP, Proteintech, 1:5000 for WB, 1:300 for IF), FOXM1 (sc-376471, Santa Cruz, 1:500 for WB, 1:100 for IHC), HO-1 (10701-1-AP, Proteintech, 1:3000 for WB), Actin (66009-1-Ig, 1:50000 for WB), GAPDH (60004-1-Ig, Proteintech, 1:100000 for WB), Histone H3 (ABL1070, Abbkine, 1:2000 for WB), Flag (66008-4-Ig, Proteintech, 1:5000 for WB, 1:125 for IP), Myc (60003-2-Ig, Proteintech, 1:5000 for WB, 1:250 for IP), HA (51064-2-AP, Proteintech, 1:2000 for WB, 1:200 for IP), Ki67 (27309-1-AP, Proteintech, 1:10000 for IHC). Mouse IgG (5415), rabbit IgG (3900) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled or fluorescently labeled secondary antibody conjugates were purchased from Abcam. To eliminate interference from heavy chain, a secondary antibody specific to light chains and conjugated with HRP was used (Abbkine, A25022). Erastin (S7242), RSL3 (S8155), IKE (S8877), NAC (S5804), ferrostatin-1 (S7243), Z-VAD-FMK (S7023), necrostatin-1 (S8037), alisertib/MLN8237 (S1133), MG132 (S2619), cycloheximide (CHX) (S7418), doxycycline (DOX) (S5159), sulforaphane (S5771), brusatol (S7956) and KI696 (E1141) were obtained from Selleck Chemicals.

2.4. Plasmids and lentivirus transduction of cells

The AURKA D274 N mutants and shRNA-resistant AURKA were produced by utilizing the Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit from NEB. Lentiviral constructs expressing Flag-tagged wild type AURKA, Flag-tagged AURKA mutants D274 N, Myc-tagged wild type AURKA, Myc-tagged AURKA mutants D274 N, Flag-tagged NRF2, Myc-tagged KEAP1(WT), Myc-tagged KEAP1(T80A), Myc-tagged KEAP1(T80D), Flag-tagged KEAP1(WT), Flag-tagged KEAP1(T80A), Flag-tagged KEAP1(T80D), Flag-tagged FOXM1, HA-tagged CUL3, and HA-tagged Ub were cloned and verified by DNA sequencing. Genechem (Shanghai, China) provided the lentivirus-based plasmids LV2-pGLV-u6-shRNA-puro, which containing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) that targeted AURKA or FOXM1 were purchased from. The target sequences were: AURKA 1#: 5′-GCATTTCAGGACCTGTTAAGG-3’; AURKA 2#: 5′-GGGTCTTGTGTCCTTCAAATT-3′; FOXM1 1#: 5′-TTGCAGGGTGGTCCGTGTAAA-3’; FOXM1 2#: 5′‐AGGACCACTTTCCCTACTTTA‐3′. According to the manufacturer's instructions, the Mission Lentiviral Packaging Mix (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to transfect the lentivirus plasmid into 293FT cells. 48 h post-transfection, the lentivirus was collected and the determination of titers were conducted using the Lenti-X p24 Rapid Titer Kit from Clontech. Cells that underwent transduction were chosen using puromycin (0.1–0.6 μg/ml, Sigma) for a duration of 7 days. Subsequently, the cells were treated with Dox (1 μg/ml, Sigma) for 4 days, and the levels of protein silencing were confirmed through Western blot analysis.

Generation of NRF2 Knock-out (KO), KEAP1 KO, KEAP1 Knock-in (KI) meningioma cell lines.

The CRISPR genome editing technique was used for the generation of KO meningioma cells. Briefly, the guide sequences were cloned into pLentiCRISPRv2 vector. IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells were seeded with about 70% cell density at 100-mm plate. After a 24-h incubation period, cells were transfected with pLenti-CRISPRv2, pmDC-gag/pol, pRSV-rev, and pmDK-VSVg using Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen). Following a 3-day incubation period, the cell media were filtered using a 0.22-μm filter (Satorius Stedim Biotech) to collect lentiviral particles, which were subsequently stored at −80 °C. IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells were cultured in six-well plates and exposed to 500 μl of the filtered lentiviral particles for transduction. After a 72-h transduction period, cells were selected using puromycin (5 μg/ml) for 3 days, and subsequently, single colonies were transferred to individual wells of a 96-well plate. The NRF2 and KEAP1 KO clones were screened by immunoblot analysis. KEAP1 T80A and T80D knock-in IOMM-Lee cells were generated following manufacturer's instructions (Corues Biotechnology, China). Briefly, the guide sequences were cloned into pCas-Puro-U6-KO vector. Donor DNA fragments containing KEAP1 point mutations were obtained and cloned into pDonor3-SV40-GFP(2A)Puro-LB-mutKEAP-RB vector. IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells were seeded and transfected with sgRNA and Donor DNA, followed by selection using puromycin. SgRNA used for KO and KI are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

2.5. RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Meningioma cells or tissues were subjected to Trizol-based isolation of total RNA, which was then converted into cDNA using a reverse transcription kit (Vazyme). A SYBR Green (Vazyme) assay was employed to perform quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). The expression levels of the target genes were normalized to the β-actin gene and are presented as 2ΔΔCt values. Supplementary Table 2 provides the primers used for amplification in this study.

2.6. Western botting

To lyse proteins, RIPA buffer supplemented with a mixture of protease and phosphatase inhibitors was utilized for both cells and tissues. Afterwards, the nuclear and cytoplasmic portions were isolated and separated utilizing the Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit (P0027, Beyotime, China). Then, the obtained samples were separated on SDS-PAGE gels with appropriate concentrations. Subsequently, the proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes (Merck Millipore). After a 2-h period of blocking using skim milk diluted to 5–10%, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. Following the TBST wash, the membranes were further probed with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h and then washed and detected with SuperSignal® Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Image Lab (Bio-Rad) was used to quantify the intensities of the bands.

2.7. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay

IHC analysis was conducted on human meningioma samples utilizing anti-AURKA, FOXM1, and NRF2 antibodies. Two independent researchers assessed the immunostaining results. In accordance with the established procedure, all tissues were fixed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution and subsequently embedded in paraffin. Next, the paraffin blocks were sectioned into 4-μm-thick slices, incubated with the specified primary antibodies overnight, then followed by incubation with secondary antibody.

2.8. Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

Meningioma cells were cultured in 96-well plates and allowed to grow for varying durations of 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h. The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (Dojindo, Japan) was used to evaluate cell proliferation or viability, according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Every 24 h, a volume of 10 μL of CCK8 solution in fresh culture medium was added and left to incubate at 37 °C for 2 h. Afterwards, at a wavelength of 450 nm, the optical density (OD) value was measured using a microplate reader (Multiskan FC, Thermofisher Scientific, USA).

2.9. EdU assay

The indicated cells were placed in 96-well plates using 10% FBS-supplemented DMEM for a duration of 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to 50 μM EdU reagent for a period of 2 h. After this incubation, the cells were treated with 4% paraformaldehyde for fixation, followed by permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100, and treated with 1 × Apollo reagent for a duration of 30 min to stain. The cell nuclei were stained using 1 × Hoechst 33342, and the cells were visualized using a fluorescent cell imaging reader (Cell Imaging Multi-Mode Reader, BioTek, USA).

2.10. Cell cycle and apoptosis assays

Cell cycle and apoptosis were assessed using a standard flow cytometry protocol. To analyze the cell cycle, cells were collected and fixed with 70% ethanol at −20 °C overnight before being subjected to propidium iodide (PI) staining. The Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (KeyGEN BioTECH, China) was utilized to analyze cell apoptosis. In brief, the cells were rinsed with ice-cold PBS and suspended in Annexin V staining buffer. The cells were then stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–Annexin V and PI at room temperature for 15 min, followed by immediate analysis using a flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, CytoFLEX, USA).

2.11. Cellular ROS detection

ROS levels were measured by utilizing the ROS Assay Kit (Beyotime, China) and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorsecein-diacetate (DCFH-DA). Following the indicated treatments, the cells were rinsed twice using PBS and subsequently exposed to 5 μM DCFH-DA for a duration of 30 min at a temperature 37 °C without light. An equal number of cells were rinsed and then suspended in culture medium for further analysis using a flow cytometry or a microplate reader (BioTek, Synergy H1, USA) to assess the fluorescent intensity (Ex: 488 nm, Em: 525 nm).

2.12. Cytotoxicity assay

The Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (LDH) (Beyotime Biotech, China) was used to measure the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) for evaluation of cytotoxicity, in accordance with the instructions provided by manufacturer. Briefly, 120 μl of culture media were collected after centrifugation at a speed of 400g for 5 min. Subsequently, each sample received an addition of 60 μl of the prepared LDH test working fluid. The plates were then incubated in the dark at room temperature for a duration of 30 min. Finally, the measurement of absorbance at 490 nm was conducted using a microplate reader (Multiskan FC, Thermofisher Scientific, USA).

2.13. Malondialdehyde (MDA) assay

Cell lysates were assessed for the concentration of relative MDA using an MDA Assay Kit (M496) obtained from Dojindo, following the guidelines provided by manufacturer. Briefly, specified reagents were used to treat transfected meningioma cells that were cultured in a 15 cm plate. Cells or 10 mg of tumor tissue were rinsed with ice-cold PBS and then homogenized on ice using Antioxidant PBS solution. After homogenizing, the samples were centrifuged at a speed of 10,000g for a duration of 5 min in order to eliminate insoluble substances. Subsequently, a volume of 100 μl from the supernatant of each homogenized sample was moved to a microcentrifuge tube. 100 μl of Lysis Buffer was added to each vial, then 250 μl of Working solution. Vortex the contents to ensure thorough mixing. Incubating the samples at 95 °C for a duration of 15 min, followed by cooling in an ice bath for 5 min. Extract 100 μl from each reaction mixture using a pipette and transfer it into a 96-well plate with a clear bottom and black surface for subsequent analysis. Utilizing a microplate reader (BioTek, Synergy H1, USA) to assess the fluorescent intensity (Ex: 540 nm, Em: 590 nm).

2.14. GSH assay

The processed cells were collected, rinsed twice in PBS, and then lysed in RIPA lysis buffer. Afterwards, the GSH concentation was measured using a commercially GSH assay kit (Beyotime, S0053) according to the protocol provided by manufacturers.

2.15. Iron assay

The intracellular concentration of ferrous iron (Fe2+) was quantified using the FerroOrange probe (Dojindo, Japan) following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Cells were cultured in 96-well black plates with clear bottom and then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 overnight. Afterwards, the cells underwent treatment with the specified reagents. Following three washes with HBSS, 100 μl of FerroOrange Working Solution was added to the cells. After a 30-min incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in the dark, the fluorescent intensity (Ex: 543 nm, Em: 580 nm) was measured using a microplate reader.

2.16. Lipid ROS assay using flow cytometer

Flow cytometry was utilized to assessed the level of lipid ROS by employing the BODIPY-C11 dye. The cells were cultured in 6-well plates and leaved to grow overnight. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to either DMSO or erastin for a duration of 24 h. Following the replacement of the culture medium with 2 ml of BODIPY-C11 (D3861, Thermo Fisher), the cells were incubated for a period of 20 min. To eliminate excess BODIPY-C11, the BODIPY-C11 was rinsed twice with PBS and then suspended in 300 μl of PBS. Afterwards, the cell suspension was analyzed using flow cytometry to quantify lipid ROS within the cells. Flow cytometry (CytoFLEX S, Beckman Coulter) was used to determine the fluorescence intensities of cells per sample. Each condition was analyzed with a minimum of 10,000 cells.

2.17. Immunofluorescence staining

Initially, cells were placed on glass coverslips and then treated with a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 30 min to fix them. After fixation, the cells were treated with a PBS solution containing 0.3% Triton X-100 for 20 min, then incubated with a 5% bovine serum albumin solution for 1 h. Afterwards, the cells were treated with primary antibodies that were diluted and incubated at a temperature of 4 °C for a period of 12 h. Additionally, the cells were subjected to an extra hour of treatment with Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 594) or Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488). The nuclei were stained with DAPI (C1005, Beyotime, China). Immunofluorescence imaging involved imaging the staining at × 40 using a fluorescence imaging system (Leica Thunder Imager; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). To conduct colocalization analysis, the staining was captured using a laser confocal microscopy (Leica Stellaris STED; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) at a magnification of × 63.

2.18. Protein half-life assay

To conduct AURKA half-life assay, the indicated cells were exposed to the protein synthesis blocker CHX (10 μg/ml) for the indicated time prior to sample collection.

2.19. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay

Indicated cells were collected and lysed with RIPA lysis buffer that included protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein A/G-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) were used to preclear cell lysates, which were then immunoprecipitated with the specified primary antibody at 4 °C for a duration of 6 h. To eliminate proteins that were not bound, microbeads were rinsed with 1 × loading buffer. Negative control was performed using either Mouse or Rabbit IgG. The immunoprecipitated complexes underwent immunoblotting analysis after being subjected to electrophoresis on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. The silver staining procedure followed the manufacturer's protocol using a Fast Silver Stain Kit (Beyotime, P0017S, China).

2.20. Mass spectrometry

BGI Tech Solutions Co., Ltd (BGI_Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) performed liquid chromatography (LC) coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (MS). The protein pellets were broken down using trypsin at a ratio of 1:20 and then left to incubate at 37 °C for a duration of 4 h. For each sample, an amount of protein ranging from 2 to 5 mg was loaded into the LC-MS/MS.

2.21. GST pulldown assay

For the GST pull-down test, glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare) were used to immobilize GST, GST-KEAP1, and GST-NRF2 that were expressed by bacteria. The beads were subsequently exposed to Flag-AURKA(WT) or Flag-AURKA(D274N) produced in HEK293T cells and incubated at 4 °C for a period of 2 h. Afterwards, the complexes underwent four washes with GST-binding buffer and were then analyzed by immunoblot.

2.22. In vitro kinase assay

The AURKA kinase was expressed in E. coli BL21 as a His-tagged protein. The AURKA kinase assay was performed by incubating the His-tagged AURKA which was immunoprecipitated with His beads (Sigma, P6611), with recombinant GST–KEAP1 in a kinase assay buffer consisting of 2 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 μM ATP, 40 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), and 1 mM EDTA. After being incubated for 30 min at 30 °C for reaction, the mixtures were subjected to SDS-PAGE and LC-MS/MS analysis.

2.23. Dual-luciferase reporter assay

We cloned genomic fragments corresponding to the AURKA promoter region into the pGL3 luciferase reporter vector (Promega) to evaluate the transcriptional activity of AURKA. Additionally, luciferase vectors driven by promoter sequences containing mutated putative FOXM1 binding sites were generated. The co-transfection of the reporter vector and beta-galactosidase cDNA expression plasmid into cells was achieved using Lipofectamine 2000. Luciferase activity driven by the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE) was evaluated to assess NRF2-mediated transcriptional activity. Eight copies of ARE-luciferase reporter plasmids, produced using the pGL3 promoter vector, were co-transfected with the pRL-TK plasmid at a ratio of 10:1 (8 × ARE pGL3:pRL-TK). After a 48-h incubation period, the cells were lysed using the lysis buffer provided by the luciferase assay kit (Promega), and luciferase activity was measured using a Synergy H1 luminometer (BioTek, USA). Transfection of control renilla was used to normalize luciferase activity.

2.24. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

The DNA-protein complexes were subjected to immunoprecipitation using FOXM1 antibody and protein A/G-agarose (Millipore). Subsequently, the DNA was extracted and purified from the complexes, followed by PCR amplification utilizing primers designed specifically for the AURKA promoters. Following the ChIP assay, a semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis was conducted using AURKA primers: 5′- GTGGCCCACCCCTAACTTCT-3′ and 5′- GTCCTCGTGTGCTCACCTGC-3′, subsequent to the ChIP assay.

2.25. 12-HETE and 15-HETE levels detection

12/15-HETE levels were assessed using a 12/15-HETE ELISA kits (ab133034/ab133035, Abcam) according to the manufacturer's instructions and our previous study [6].

2.26. Xenograft mouse model and drug administration

Male nude mice, aged 6 weeks and obtained from the Nanjing Medical University Animal Center, were selected as the experimental subjects. The mice were anesthetized using a mixture of 4% isoflurane in 70% N2O and 30% O2, and their anesthesia was maintained with 2% isoflurane. An orthotropic meningioma xenografts model was established in accordance with previous reports and our own previous study [6,13]. Briefly, a total of 4 × 105 cells, which had been lentivirally transduced with firefly luciferase (Fluc), were surgically implanted into the frontal subdural region of nude mice using stereo-tactical techniques. The implantation procedure was conducted at a lateral distance of 2.5 mm from bregma and a depth of 1.0 mm from the skull. Following the implantation, IKE (40 mg/kg) and/or MLN8237 (20 mg/kg), dissolved in 10% DMSO, or a vehicle, were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) every other day, starting on Day 5. Mice weight was recorded every 5 days starting at Day 5.

Tumor growth was evaluated by quantifying Fluc activity using the IVIS Imaging System (Caliper Life Sciences). Before imaging, each mouse received an intraperitoneal dose of 10 mg D-luciferin (YEASEN, Shanghai, China). The integrated flux of photons (photons per second) within each specific region was determined using the Living Images software package (Caliper Life Sciences). The animals were continuously monitored for clinical signs, and mice in a moribund state were euthanized to verify the presence of tumors.

2.27. Half-maximal inhibitory concentration assay (IC50)

The cells were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 1.0 × 104 cells per well. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to MLN8237 at corresponding concentrations for a duration of 24 h. Following this incubation period, the sensitivity of MLN8237 was assessed using CCK-8 (Dojindo, Japan) at a wavelength of 450 nm, employing a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher, USA) after a 2-h incubation at 37 °C.

2.28. Statistics

Graphpad Prism 8.0 was utilized for statistical analysis. Data are presented as the means ± SD or mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. The differences between two groups were analyzed by Student's t-test, one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The log-rank test was used to calculate the statistical significance of the Kaplan–Meier survival curve. P < 0.05 was considered to have statistical significance.

2.29. Study approval

All tumor collection and subsequent analyses were conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and ethics committees of Nanjing Medical University. All patients enrolled in this study according to the institutional protocols (JSSRY-KY16-022) provided prior informed consent. The animal experiments carried out in this study were conducted in accordance with the Animal Management Rule of the Chinese Ministry of Health (documentation 55, 2001) and adhered to the approved guidelines and experimental protocol of Nanjing Medical University.

3. Results

3.1. AURKA levels show an increasing trend with higher grade meningiomas

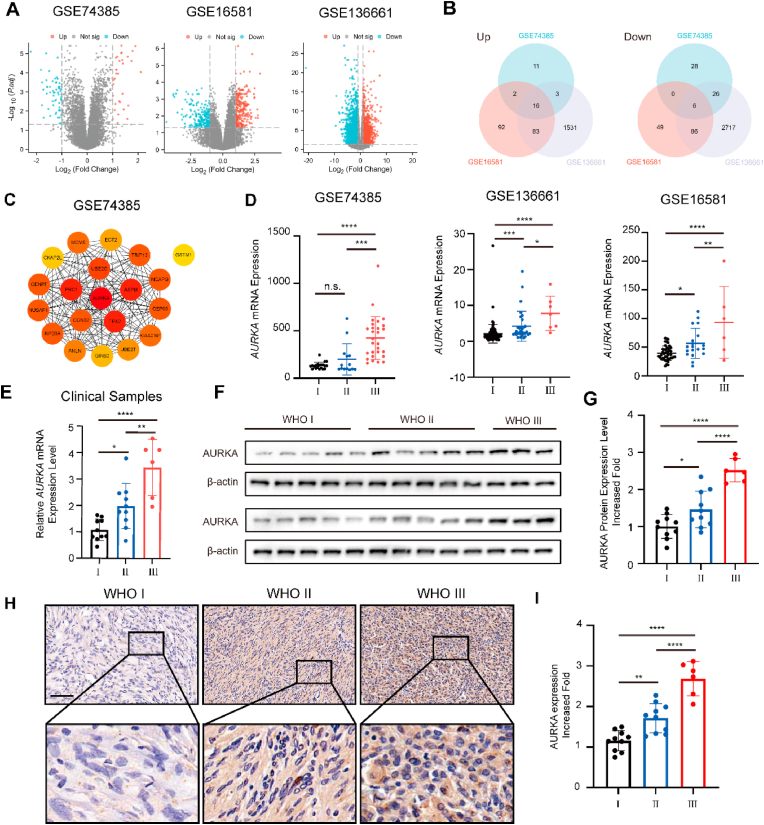

Three Meningioma-related GEO datasets, GSE74385, GSE16581 and GSE136661 were obtained for differentially express genes (DEGs) analysis between WHO grade III and grade I tumors, the DEGs were visualized as Volcano Plots (Fig. 1A). 22 overlapped DEGs were identified, with 6 downregulated and 16 upregulated (Fig. 1B). Notably, AURKA was one of the genes found to be upregulated. The protein-protein interaction network (PPI) of the top 20 differentially expressed genes from the GSE74385 dataset, which contains the highest number of WHO grade III tumor samples, was examined utilizing the STRING database. The resulting network was then visualized using Cytoscape, with AURKA being identified as the top-ranking gene (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

AURKA is overexpressed in high grade meningioma. (A) Volcano plot of DEGs in GSE74385, GSE136661, GSE16581. (B) Venn diagrams showed the number of upregulated and downregulated DEGs that overlap between GSE74385, GSE136661, GSE16581. (C) PPI network of the top 20 DEGs in GSE74385. (D) Relative mRNA expression of AURKA in meningioma samples according to GEO database and (E) clinical samples, as detected by qPCR. (F) Western blotting analysis of AURKA protein expression in human meningiomas. β-actin was used as a control. (G) Quantitative analysis of AURKA protein levels by ImageJ. (H) Representative IHC photos of AURKA protein expression. Scale bar, 100 μm. (I) IHC image quantification AURKA by ImageJ. Data in (D) are presented as means ± SEM, data in (E), (G) and (I) are presented as means ± SD and analyzed by one-way ANOVA. n.s. for P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

Data from the three published GEO datasets showed that AURKA expression increased with higher WHO grade, with a significant upregulation observed in WHO grade III tumor specimens compared to WHO grade I tissues (Fig. 1D). To validate these findings, qRT-PCR was performed on twenty-six randomly selected meningioma tissues, including ten WHO grade I, ten WHO grade II, and six WHO grade III specimens (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, the upregulation of AURKA protein was confirmed through Western blot assays conducted on these tissues (Fig. 1F and G). The higher-grade meningioma tissues were further confirmed to have an increase in AURKA protein expression through immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining (Fig. 1H and I). Hence, these findings suggest that AURKA could potentially facilitate the malignant progression of meningioma.

3.2. Facilitatory effects of AURKA on advancement of meningioma cells

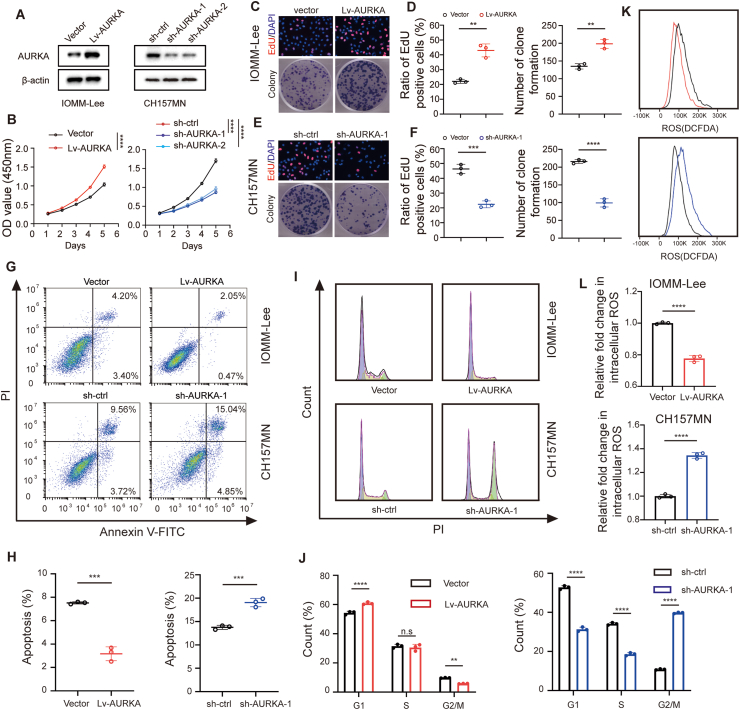

The first identified and the most common genetic alteration in meningioma is the inactivation of NF2, which is present in approximately half of sporadic primary meningiomas [14]. To investigate the impact of AURKA on meningioma progression, two malignant meningioma cell lines, namely CH157MN (with NF2 mutation) and IOMM-Lee (without NF2 mutation), were utilized to represent NF2-mutated and NF2-nonmutated meningiomas. Lentivirus-mediated transfection of sh-AURKA was employed to silence AURKA in the two cell lines. The results demonstrated that sh-1 displayed the utmost effectiveness in suppressing AURKA and was therefore chosen for additional examinations (Fig. 2A and B, Fig. S1A and B). Stable overexpression of AURKA was confirmed (Fig. 2A, Fig. S1A). CCK-8 assays indicated a significant enhancement in cell proliferation upon overexpression of AURKA, while its inhibition was observed following the silencing of AURKA (Fig. 2B, Fig. S1B). EdU assay and colony formation assay further confirmed the results (Fig. 2C–F, Fig. S1C-F). Additionally, the flow cytometric analysis demonstrated that the upregulation of AURKA led to the inhibition of cell apoptosis in both cell lines, whereas the inhibition of AURKA induced cell apoptosis (Fig. 2G and H, Fig. S1G and H). Subsequently, we examined the impact of AURKA on the progression of cell cycle in meningioma cells. G2/M arrest was observed with knockdown of AURKA, while G2/M transit increased following the overexpressing of AURKA (Fig. 2I and J, Fig. S1I and J). Furthermore, the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within meningioma cells transfected with sh-AURKA exhibited a notable increase when compared to the control group. In contrast, compared to the control group, intracellular total ROS in cells transfected with Lv-AURKA were significantly lower (Fig. 2K and L, Fig. S1K and L). To summarize, these results offer proof that AURKA plays a vital part in promoting the progression of meningioma and suppressing oxidative stress in vitro.

Fig. 2.

Facilitatory effects of AURKA on malignant phenotype of meningioma in vitro. (A) Immunoblotting of AURKA in transfected IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells. (B) CCK-8 assays in indicated IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells. (C, D) EdU assay and quantitative analysis in IOMM-Lee cells with AURKA overexpression. (E, F) Colony formation assay and quantitative analysis in CH157MN cells with AURKA knockdown. (G, H) Flow cytometry of apoptosis and quantitative analysis in indicated IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells. (I, J) Flow cytometry of cell-cycle and quantitative analysis in indicated IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells. (K, L) Flow cytometry and quantitative analysis of intracellular ROS in indicated IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells stained by DCFH-DA. Data are presented as means ± SD, n = 3 experiments. Data in (B) and (J) are analyzed by two-way ANOVA with post hoc test. Data in (D), (F), (H) and (L) are analyzed by unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. n.s for P > 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

3.3. AURKA confers ferroptosis resistance in meningioma

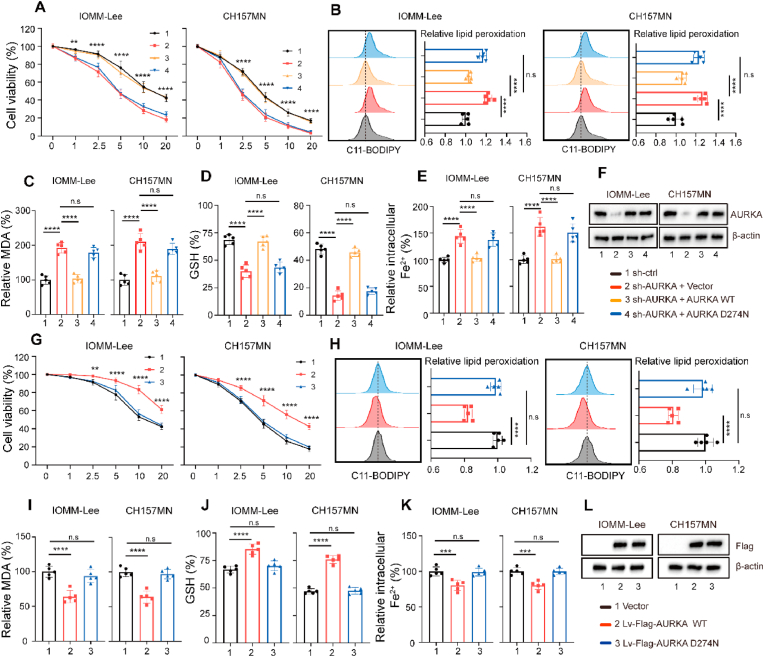

Our previous research demonstrated that utilizing erastin to trigger ferroptosis has significant promise as a molecular method to target meningiomas [6]. Recent research presented findings suggesting that AURKA may be involved in regulating the ferroptosis process [[10], [11], [12]]. For example, in the context of a diabetic limb ischemia model, the overexpression of AURKA was found to hinder oxidative stress and subsequent alterations in lipid peroxidation biomarkers, which serve as indicators of ferroptosis [11]. We also found that AURKA altered ROS levels in meningioma cells (Fig. 2K and L, Fig. S1K and L). Thus, we investigated whether AURKA is also involved in the regulation of ferroptosis in meningiomas. Firstly, we examined whether AURKA was activated during the ferroptotic process. We observed that erastin concentration- and time-dependently induced AURKA phosphorylation at Thr288 in IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells (Fig. S2A and B). In addition, the use of Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1), a specific ferroptosis inhibitor, completely inhibited AURKA phosphorylation induced by erastin (Fig. S2C and D). The findings indicated that AURKA might function as a sensor of erastin-induced ferroptosis. To ascertain whether direct induction of ferroptosis can be achieved through inhibition of AURKA, IOMM-Lee cells were transfected with shRNA targeting AURKA. The results revealed a significant increase in LDH release, which could be inhibited by Z-VAD-FMK, a particular blocker of caspase-mediated apoptosis, whereas Fer-1 or Necrosatatin-1 (RIP1-targeted inhibitor of necroptosis) did not have the ability to reverse the release (Fig. S3A). These findings suggest that direct induction of ferroptosis cannot be achieved through inhibition of AURKA. Consequently, we postulated that AURKA may regulate the sensitivity of ferroptosis. Subsequently, 6 μM erastin was employed to initiate ferroptosis in two distinct meningioma cell types, as per our prior investigation [6]. In IOMM-Lee cells with AURKA-knockdown, erastin elicited a significant increase in LDH and lipid peroxidation, as measured by malonaldehyde (MDA), compared to sh-ctrl cells. This effect was mitigated by the administration of Fer-1 (Fig. S3B and C). Similarly, elevated levels of LDH and MDA were observed in erastin-treated CH157MN cells, which were attenuated by Fer-1. Conversely, no alterations were detected in CH157MN cells overexpressing wild-type AURKA (Fig. S3D and E). We conducted additional experiments to validate the suppression of AURKA by specific shRNA, which led to increased cell death induced by erastin in both meningioma cell lines (Fig. 3A). This was accompanied by an increase in ferroptotic events including lipid ROS production, iron accumulation and glutathione (GSH) depletion. Conversely, the reintroduction of shRNA-resistant AURKA abolished the sensitivity to erastin (Fig. 3B–F). To investigate whether the regulatory function of AURKA on ferroptosis is dependent on its kinase activity, we expressed the kinase inactive form of AURKA with the D274 N mutation (AURKAD274N) and observed its inability to confer resistance to erastin. Similarly, the exogenous expression of AURKA, as opposed to AURKAD274N, was found to enhance cell viability in erastin-treated meningioma cells (Fig. 3G) by diminishing ferroptotic occurrences (Fig. 3H-L). RSL3 is a ferroptosis inducer that differs from erastin in its mechanism of action. It specifically targets a crucial antioxidant enzyme called glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4). Intriguingly, in meningioma cells, neither downregulation nor overexpression of AURKA had a significant effect on RSL3-induced ferroptosis (Fig. S4A–F). These findings collectively indicate that AURKA specifically plays a crucial role in regulating the vulnerability of meningioma cells to erastin-induced ferroptosis depending on its kinase activity.

Fig. 3.

AURKA regulates erastin-induced ferroptosis. (A, G) Transfected IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells were exposed to the respective indicated dose of erastin (1–20 μM) for 24 h and the cell viability was examined using CCK8 assays. n = 5 experiments. (B-E, H–K) Indicated IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells were exposed to 6 μM erastin for 24 h n = 5 experiments. (B, H) Flow cytometric analysis for lipid peroxidation levels using C11-BODIPY. (C, I) MDA levels were detected using MDA assay kits. (D, J) Concentrations of GSH were detected using GSH assay kits. (E, K) Intracellular Fe2+ level was measured by FerroOrange using a fluorescent microplate reader. (F, L) Immunoblotting of AURKA expression with β-actin as internal reference. Data are presented as means ± SD. Data in (A), (G) are analyzed by two-way ANOVA with post hoc test. Data in (B–E), (H–K) are analyzed by one-way ANOVA. n.s for P > 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

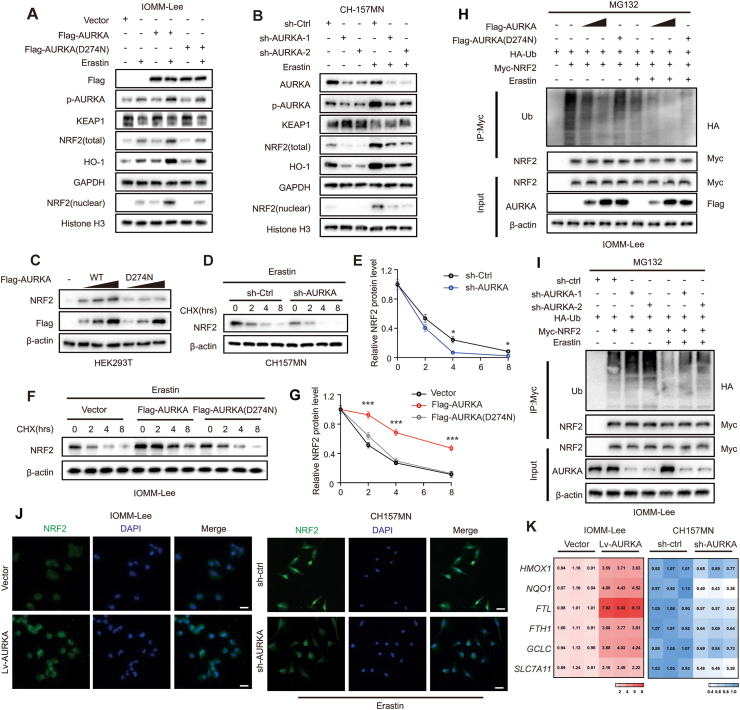

3.4. AURKA activates NRF2 pathway by inhibiting NRF2 ubiquitination and degradation

To explore the potential mechanism by which AURKA confers ferroptosis sensitivity in meningioma, we conducted RNA-seq analysis to compare the transcriptome changes between the control group and the AURKA overexpression (Lv-AURKA) group of IOMM-Lee cells. A total of 1160 upregulated genes and 958 downregulated genes were identified in the Lv-AURKA group based on fold changes in expression (Log2FC > 1 or < -1, adjusted P value < 0.05) (Fig. S5A). Based on TF target gene sets obtained from the ENCODE (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements) and ChEA (ChIP-X Enrichment Analysis) databases from Enrichr, we conducted transcription factors (TFs) enrichment analysis [15]. Intriguing, the TFs enrichment analysis revealed that the upregulated genes exhibit enrichment in NFE2L2/NRF2 (Fig. S5B). Additionally, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was conducted to examine the altered gene sets between the control and overexpression groups, and it was observed that these DEGs were enriched in the signaling pathways associated with NRF2 pathway (Fig. S5C). Gene expression profiles demonstrated that upon AURKA overexpression, NRF2 downstream target genes were significantly upregulated (Fig. S5D). Given that NRF2 is widely acknowledged as a crucial controller of the cellular antioxidant reaction, including ferroptosis [16], we hypothesized that AURKA might provide resistance to ferroptosis through the NRF2 pathway.

Firstly, we assessed the change in NRF2 mRNA levels in meningioma cells. NRF2 mRNA expression showed no notable disparity in IOMM-Lee cells when comparing control and AURKA overexpression, as well as control and knockdown of AURKA in CH157MN cells (Fig. S5E). However, following erastin treatment, significant increase was observed in the protein levels of total and nuclear NRF2, as well as phosphorylated AURKA, while the total AURKA protein level moderately decreased (Fig. 4A). In the sh-AURKA group of CH157MN cell, NRF2 protein levels were significantly lower than in the control group. Conversely, in the IOMM-Lee cell, the Lv-AURKA group exhibited increased NRF2 levels, whereas the Lv-AURKAD274N group did not show this increase (Fig. 4A and B). These findings imply that the upregulation of NRF2 protein levels may be influenced by a post-transcriptional control mechanism associated with AURKA expression and its kinase activity.

Fig. 4.

AURKA promotes anti-ferroptotic capacity of meningioma cells through activating NRF2. (A–B) Immunoblot analysis of indicated protein levels in transfected meningioma cells treated with DMSO or erastin (6 μM for 24 h). (C) HEK293T cells were transfected with increasing amounts of AURKA(WT) or AURKA(D274 N) and NRF2 protein level was detected by immunoblotting. (D–G) In indicated meningioma cells, NRF2 protein half-life was determined. Cells were treated with 10 μg/mL CHX and lysed at indicated time points followed by immunoblotting. n = 3 experiments. (H–I) Indicated transfection of IOMM-Lee cells were harvested after treatment with MG132 (50 μM) for 4 h and were lysed for immunoprecipitation with anti-Myc antibody, followed by immunoblot analysis. (J) Immunofluorescent imaging of NRF2 (green) showed subcellular location in indicated IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells. CH157MN cells were treated with 6 μM Erastin for 24 h. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 20 μm. (K) QRT-PCR was used to detect the mRNA expression of NRF2 downstream anti-ferroptotic genes. Heatmaps show transcript levels normalized by those of cells transduced with empty vectors. n = 3 experiments. Data are presented as means ± SD. Data in (E and G) are analyzed by two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, and ***P < 0.001.

Based on prior research, it has been established that the degradation of NRF2 is primarily facilitated by the ubiquitination-mediated proteasome pathway [17]. In order to investigate whether AURKA regulates the protein levels of NRF2 through its impact on stability, we conducted an experiment wherein wild-type AURKA or AURKAD274N were overexpressed in HEK293T cells. The results indicated that AURKA led to an increase in NRF2 protein levels, whereas AURKAD274N, lacking kinase activity, did not exhibit the same effect (Fig. 4C). This suggested that AURKA modulates the stability of NRF2 in a manner that is reliant on its kinase activity. Consistently, following erastin stimulation, the knockdown of AURKA in CH157MN cells resulted in the destabilization of NRF2 protein. Conversely, the enforced expression of wild-type AURKA, but not the kinase inactive mutant AURKA, led to a significant increase in the half-life of NRF2 protein in IOMM-Lee cells, as determined by cycloheximide (CHX) chase assay (Fig. 4D–G). Through ubiquitination assays, we observed a marked decrease in NRF2 ubiquitination in AURKA overexpressing IOMM-Lee cells, but not in AURKAD274N cells (Fig. 4H). In line with these findings, we discovered that the knockdown of AURKA significantly increased the ubiquitination of NRF2 in CH157MN cells (Fig. 4I). These results indicate that AURKA mediated NRF2 stability and ubiquitination dependent on AURKA kinase activity.

Subsequently, we investigated the impact of AURKA on the translocation of NRF2 to the nucleus and the levels of mRNA for various NRF2 target genes associated with redox and ferroptosis regulation. The immunofluorescence staining results revealed a significant enhanced nuclear NRF2 staining signal in AURKA overexpressing IOMM-Lee cells compared to the vector-control cells. Conversely, the nuclear NRF2 signal was attenuated in the CH157MN with sh-AURKA cells relative to the sh-ctrl counterparts (Fig. 4J). These findings were further validated through immunoblotting analysis of both total and nuclear protein extracts (Fig. 4A and B). Consistent with these findings, AURKA overexpression in IOMM-Lee cells led to a significant elevation in the mRNA levels of crucial NRF2 target antioxidant and anti-ferroptotic genes. Conversely, the knockdown of AURKA in CH157MN cells led to a decrease in the mRNA levels of these genes (Fig. 4K). Through measuring ARE-luciferase activity, we discovered that overexpression of AURKA in IOMM-Lee elevated the ARE-luciferase activity, whereas knockdown of AURKA in CH157MN diminished it (Fig. S5F). This indicates that the upregulation of mRNA levels of NRF2 target genes occurs via transcriptional regulation. Furthermore, to determine whether AURKA inhibits erastin-induced ferroptosis through NRF2, we used CRISPR-Cas9 system to knockout NRF2 in both IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells. We observed that in NRF2-KO meningioma cells, neither knockdown nor overexpression of AURKA could change the cells sensitivity to erastin (Fig. S6). These results indicate that AURKA inhibited ferroptosis induced by erastin dependent on NRF2.

Collectively, AURKA seems to prevent the ubiquitination and degradation of NRF2 protein, thereby facilitating its translocation to nucleus and enhancing its functional activation, ultimately augmenting the anti-ferroptotic potential of meningioma cells.

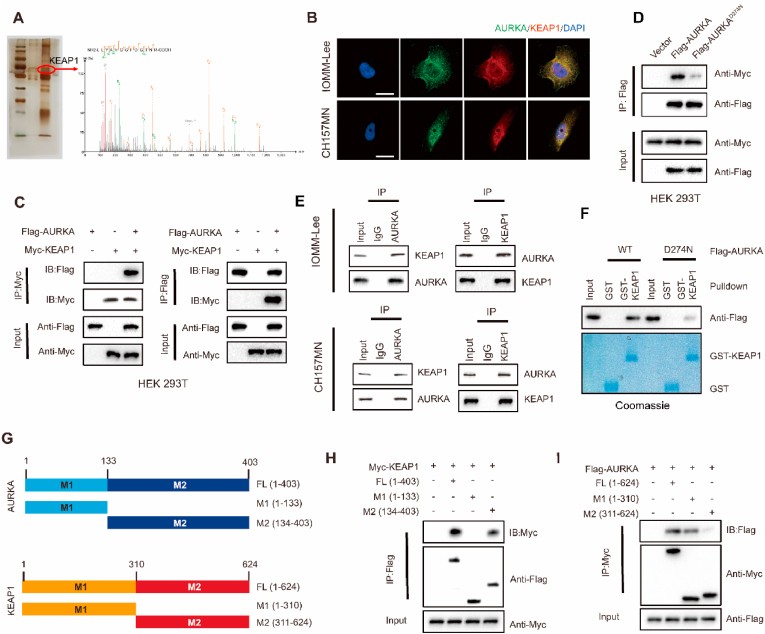

3.5. AURKA directly combines with KEAP1

Based on prior research findings, AURKA has been observed to interact with various proteins as a serine/threonine protein kinase, including tumor suppressors and oncogenes, thereby facilitating the process of carcinogenesis [9]. Additionally, there have been reports indicating that the activity of NRF2 can be regulated through phosphorylation events [18,19]. Hence, we sought to examine the possible regulatory function of AURKA in maintaining NRF2 stability by their interaction. In HEK293T cells, we performed reciprocal Co-IP experiments by co-transfecting Flag-tagged AURKA (WT) and Myc-NRF2, which showed the interaction between AURKA and NRF2 (Fig. S7A and B). We conducted GST pull-down experiments to investigate whether AURKA directly interacts with NRF2 in vitro, however, the results showed that AURKA was unable to bind to immobilized GST-NRF2 (Fig. S7C). These findings indicate that AURKA was unable to directly bind to NRF2, and instead, AURKA may modulate NRF2 activity by interacting and phosphorylating an intermediary molecule.

To explore how AURKA regulates NRF2, we employed immunoprecipitation of AURKA from lysates of IOMM-Lee cells followed by mass spectrometry analysis. Notably, our mass spectrometry results identified several previously unknown AURKA-interacting proteins, including KEAP1 (Fig. 5A). It is widely recognized that KEAP1 interacts with NRF2 and facilitates NRF2 ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation under normal conditions [20]. Subsequently, we sought to investigate the potential direct interaction of AURKA with KEAP1. Confocal imaging demonstrated the colocalization of AURKA (green) and KEAP1 (red) in the cytoplasm of IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells (Fig. 5B). In HEK293T cells transfected with Flag-tagged AURKA and Myc-KEAP1, reciprocal co-IP experiments showed that AURKA interacted with KEAP1 (Fig. 5C). Co-IP experiments demonstrated the detectability of Myc-tagged KEAP1 in Flag-AURKAWT immunoprecipitates within HEK293T cells. However, in Flag-AURKAD274N immunoprecipitates, the detection of Myc-tagged KEAP1 was reduced, suggesting that the interaction between AURKA and KEAP1 depends on the kinase activity of AURKA (Fig. 5D). Additionally, IOMM-Lee and CH157MN meningioma cells exhibited a physical connection between endogenous AURKA and KEAP1 proteins (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, an in vitro GST pull-down assay was conducted to investigate the interaction between purified GST-KEAP1 and purified recombinant proteins Flag-AURKAWT or Flag-AURKAD274N. The findings showed that both AURKA WT and its D274 N mutant could bind to immobilized GST-KEAP1. However, the binding of D274 N mutant to GST-KEAP1 is significantly lower compared to AURKA WT, while no binding was observed with GST alone (Fig. 5F), thereby confirming the kinase-dependently direct interaction between AURKA and KEAP1. Moreover, to identify the specific regions of AURKA and KEAP1 implicated in this interaction, we created deletion mutants of AURKA and KEAP1 and co-expressed them into HEK293T cells (Fig. 5G). The direct interaction between AURKA and KEAP1 was found to require the C-terminal sequences (amino acids 134–403) of AURKA and N-terminal sequences (amino acids 1–310) of KEAP1 (Fig. 5H and I).

Fig. 5.

AURKA interacts with KEAP1. (A) AURKA interacts with KEAP1 according to silver staining and IP/MS analysis. (B) AURKA (green) and KEAP1 (red) colocalize in IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells shown by confocal images. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 20 μm. (C) IP detection of exogenous protein interactions between AURKA and KEAP1 using Flag-tagged AURKA and Myc-tagged KEAP1 plasmids transfected into HEK293T cells. (D) Myc-KEAP1 alone or in combination with Flag-tagged AURKA WT or AURKA D274 N were transfected into HEK293T cells, and were lysed for immunoprecipitation with anti-Flag antibody. (E) IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with control IgG, anti-AURKA, or KEAP1 antibodies to detect endogenous protein interactions between AURKA and KEAP1. (F) Purified Flag- AURKA (WT) or AURKA (D274 N) was incubated with GST or GST-KEAP1 coupled to glutathione-Sepharose beads. Sepharose-retained proteins were then immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. (G) Constructs of Flag-tagged full-length AURKA (FL), N-terminal of AURKA (M1(1–133)), C-terminal of AURKA (M2(134–403)), and Myc-tagged full-length KEAP1(FL), N-terminal of KEAP1 (M1(1–310)), C-terminal of KEAP1 (M2(311–624)). (H) Myc-KEAP1 and the indicated Flag-tagged AURKA constructs, (I) or Flag-AURKA and the indicated Myc-tagged KEAP1 constructs were co-transfected into HEK293T cells, and were lysed for immunoprecipitation with Myc or Flag beads and immunoblotting.

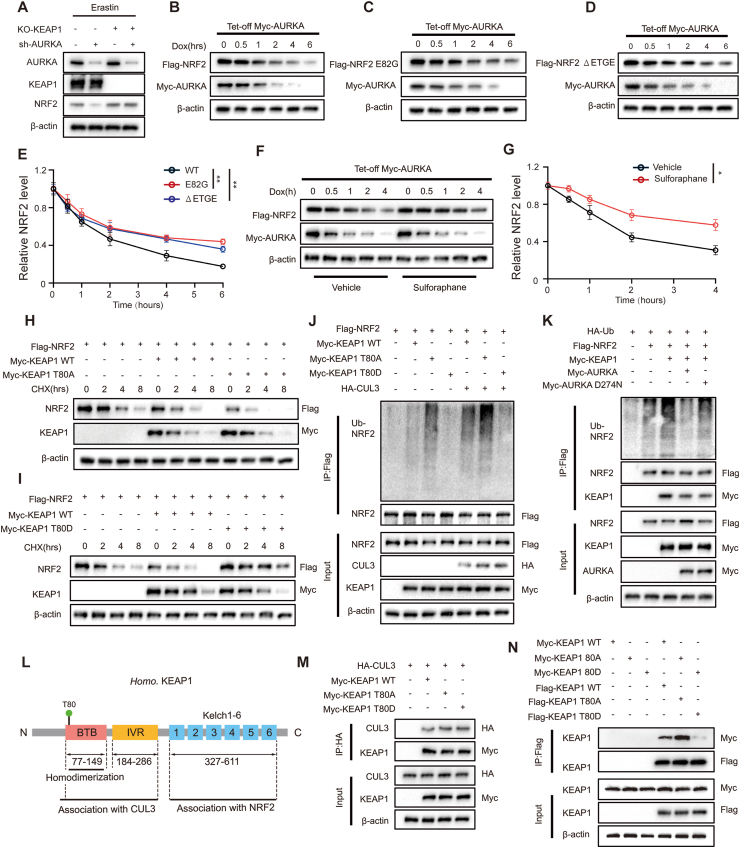

3.6. AURKA stabilizes NRF2 by combining with and phosphorylating KEAP1

We next explored whether the regulation of NRF2 by AURKA depend on KEAP1. Immunoblot analysis revealed that the reduction in NRF2 levels observed upon AURKA silencing in wild-type KEAP1 IOMM-Lee cells was prevented in the KEAP1 knock-out cells (Fig. 6A). In our experiments, we observed that erastin downregulated KEAP1 protein level (Fig. 4A and B), considering that erastin-induced upregulation of NRF2 could be due to the inactivation of KEAP1 by increased ROS, and KEAP1 is well known for its oxidative modification by ROS [23], we employed acetylcysteine (NAC) in the two meningioma cell lines to scavenge ROS. Immunoblot analysis revealed that the protein level of phosphorylated AURKA remained consistent upon erastin treatment, regardless of the presence or absence of NAC. Additionally, the NAC treatment only partially reversed the downregulation of KEAP1 and the upregulation of total and nuclear NRF2 induced by erastin, even when the levels of ROS were reduced to those observed in the control groups (Fig. S8A-D). This result suggests that erastin can directly activate NRF2 by phosphorylation of AURKA, even in the absence of ROS. In order to further examine the KEAP1-mediated NRF2 proteasomal degradation regulated by AURKA, a HEK293T Tet-Off cell line was created. This cell line allows for the expression of Myc-tagged AURKA and can be induced silencing with doxycycline (DOX). As anticipated, the Myc-AURKA expression decreased upon exposure to Dox, which corresponded with a reduction in NRF2 expression (Fig. 6B). These findings provide additional support for the previous findings that AURKA impedes the NRF2 proteasomal degradation. Subsequently, we introduced mutations in the Neh2 domain of NRF2, which have been shown to hinder the KEAP1-binding location with high affinity and impede interaction with NRF2. This was done to investigate whether the degradation of NRF2, inhibited by AURKA, is influenced by KEAP1. The outcomes revealed that both the E82G and ΔETGE variants of NRF2 effectively prevent the degradation of NRF2 (Fig. 6C–E). Furthermore, sulforaphane, an activator of NRF2, was utilized to alter important cystine residues in KEAP1, thereby preventing the ubiquitination of NRF2. Before the silencing of AURKA, sulforaphane demonstrated an ability to increase the NRF2 expression. Additionally, sulforaphane effectively slowed down NRF2 degradation rate in response to silencing of AURKA, as compared to its absence (Fig. 6F and G). Taken together, these results indicate that AURKA inhibits the proteasomal degradation of NRF2 through an interaction between NRF2 and KEAP1.

Fig. 6.

AURKA stabilizes NRF2 depends on the phosphorylation of KEAP1. (A) Immunoblot analysis of AURKA, KEAP1, NRF2 in IOMM-Lee cells with indicated transfection. (B) Flag-tagged NRF2 was expressed in HEK293T Tet-Off Myc-AURKA cells with doxycycline (Dox) inducible silencing of Myc-AURKA. Cells were treated with Dox for the indicated periods, followed by lysing and immunoblotting with anti-Flag and anti-Myc antibodies. (C–D) Transfection of plasmids encoding NRF2 variant deficient for KEAP1 binding including E82G or ΔETGE to HEK293T, followed by lysing and immunoblotting with anti-Flag and anti-Myc antibodies. (E) Quantification of Flag-NRF2 expression level in (B–D), n = 3 experiments. (F) Cells were treated with a vehicle or sulforaphane for 4 h before administration of Dox, followed by lysing and immunoblotting with anti-Flag and anti-Myc antibodies. (G) Quantification of Flag-NRF2 expression level in (F), n = 3 experiments. (H–I) A total lysate of HEK293T cells expressing HA-tagged wildtype and indicated mutant KEAP1 and Flag-tagged NRF2 followed by CHX treatments with the indicated time were analyzed by immunoblot. (J) Immunoblot analysis of the ubiquitination of NRF2 in anti-Flag IP (top) and total lysates (bottom) of transfected HEK293T cells with indicated vectors. (K) Immunoblot analysis of the ubiquitination of NRF2 in anti-Flag IP (top) and total lysates (bottom) of HEK293T cells expressing various indicated combinations of vectors. (L) Diagram of the structure of KEAP1 showing the domains of BTB, IVR, and Kelch1-6 and the location of the phosphorylated site T80 by AURKA; numbers below diagrams indicate amino acid range of each domain. (M) Immunoblot analysis of CUL3 and KEAP1 in anti-HA IP (top) and total lysates (bottom) of HEK293T cells expressing various combinations of HA-tagged CUL3, Myc-tagged KEAP1 WT, KEAP1 T80A or KEAP1 T80D. (N) Immunoblot analysis of KEAP1 in anti-Flag IP (top) and total lysates (bottom) of HEK293T cells expressing various combinations of Myc-tagged or Flag-tagged KEAP1 WT, KEAP1 T80A or KEAP1 T80D. Data are presented as means ± SD and are analyzed by two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01.

To investigate the potential phosphorylation of KEAP1 by AURKA, we conducted mass spectrometry analysis on an in vitro kinase reaction involving bacterially expressed GST-tagged KEAP1 and His-tagged AURKA. Our findings revealed that AURKA phosphorylated KEAP1 at the amino residue T80 (Fig. S9). To further examine the effect of AURKA-mediated KEAP1 phosphorylation on NRF2 stability, we created KEAP1 mutants that mimic phosphorylation or cannot be phosphorylated by substituting the T residues with aspartate (designated as KEAP1 T80D) or alanine (designated as KEAP1 T80A), respectively. We examined the impact of wild-type (WT) or mutant KEAP1 on the stability of NRF2 protein by CHX assays. Following a 2-h treatment of CHX, the overexpression of KEAP WT led to a notable reduction in NRF2 levels. In contrast, cells transfected with KEAP1 WT showed an accelerated degradation of NRF2 compared to cells transfected with the empty vector control. Cells transfected with KEAP1 T80A exhibited more significant NRF2 degradation compared to those transfected with KEAP1 WT. On the other hand, cells that were transfected with KEAP1 T80D exhibited noticeable amounts of NRF2 until 8 h of CHX treatment (Fig. 6H and I). In the presence of CUL3, NRF2 and KEAP1 WT, KEAP1 T80D, or KEAP1 T80A coexpressed respectively, which showed that KEAP1 T80A increased the level of NRF2 ubiquitination, whereas KEAP1 T80D reduced it (Fig. 6J). To examine whether mutation of endogenous KEAP1 at T80 affects NRF2 ubiquitination, we generated KEAP1 T80A and T80D knock-in IOMM-Lee cell lines using CRISPR-Cas9. Our observations mirrored those seen in the overexpression systems utilized in HEK293T cells (Fig. S10A-C). Additionally, the overexpression of wild type AURKA, but not kinase-dead AURKA (AURKAD274N), mitigated the impact of KEAP1 on NRF2 ubiquitination (Fig. 6K). Furthermore, we observed reversal of erastin-induced ferroptosis enhancement resulting from AURKA knockdown when KI696, a small molecule KEAP1-NRF2 PPI inhibitor [21], was utilized (Fig. S11A-F).

The phosphorylation of amino residue Threonine 80 on KEAP1, mediated by AURKA, is situated within the BTB domain [22,23], which plays a crucial role in the binding of the E3 ubiquitin ligase CUL3 or KEAP1 dimerization or polymerization (Fig. 6L). Our investigation revealed that the binding capacities of CUL3 to KEAP1 WT, KEAP1 T80A, and KEAP1 T80D are equivalent in HEK 293T cells co-expressing CUL3 with KEAP1 WT, KEAP1 T80A, or KEAP1 T80D (Fig. 6M), suggesting that AURKA-mediated phosphorylation of KEAP1 does not impact the interaction between KEAP1 and CUL3. The impact of AURKA-mediated KEAP1 phosphorylation on KEAP1 polymerization was assessed through Co-IP assays conducted on HEK293T cells co-transfected with Myc- and Flag-tagged KEAP1 WT or mutant KEAP1 (KEAP1 T80A or KEAP1 T80D). The results indicated that both KEAP1 WT and KEAP1 T80A exhibited the ability to form protein dimers/polymers, whereas the constitutive phospho-mimic KEAP1 T80D failed to undergo polymerization (Fig. 6N). Consequently, these findings collectively suggest that AURKA prevents ubiquitination and degradation of NRF2 by interacting with and phosphorylating KEAP1 at Thr80 and blocking its dimerization/polymerization.

Following this, we performed immunohistochemical staining of AURKA and NRF2 on a total of 50 clinical samples of meningioma. The results showed that 58% of the samples with lower AURKA levels also exhibited lower NRF2 levels, whereas 74% of the specimens with higher AURKA showed higher NRF2 expression as well (χ2 = 4.78, P = 0.0288, Fig. S12A and B). These observations imply that AURKA could potentially function as a biomarker with clinical relevance in assessing the susceptibility of meningioma to ferroptosis.

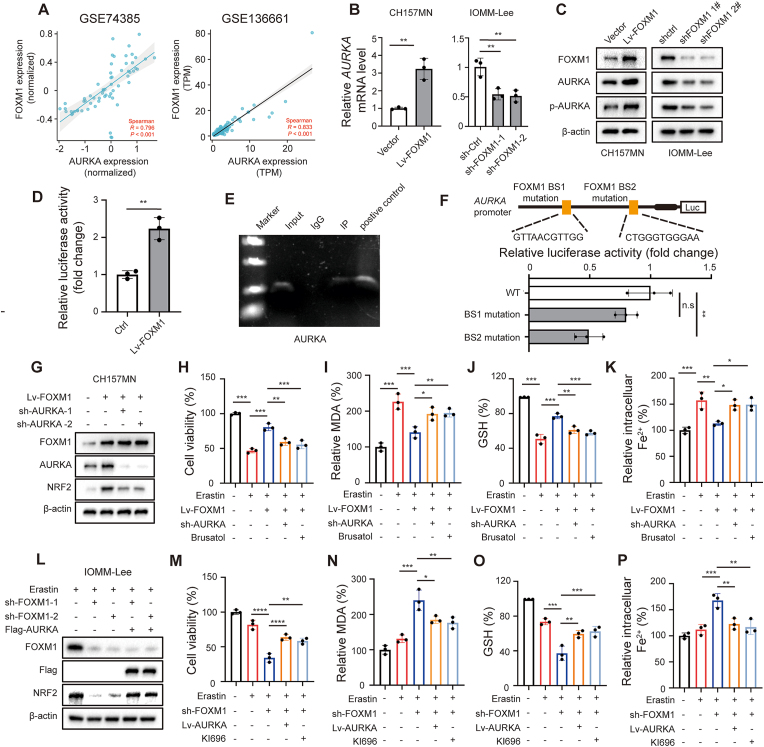

3.7. FOXM1 inhibits ferroptosis by increasing AURKA transcription

Considering AURKA mRNA level was increased with meningioma grade, we speculate that upregulation of AURKA in high grade meningioma is stimulated by transcriptional regulation. Previous studies have identified several transcriptional factors, including FOXM1, ARID3A, PUF60, STAT5 and TCF4, that can regulate AURKA transcription [9]. To identify potential transcription factors regulating AURKA in meningioma, we examined the reported factors and their expression correlation with AURKA levels obtained from two meningioma GEO datasets, GSE74385 and GSE136661, and only FOXM1 and AURKA mRNA showed a consistently and significantly strong positive correlation in both datasets (Fig. 7A, Fig. S13A and B). Notably, FOXM1 has previously been identified as a key transcription factor involved in meningioma progression [[24], [25], [26], [27]]. Additionally, a previous study has demonstrated that FOXM1 upregulates AURKA in breast cancer stem cells through specific binding to the AURKA promoter sequence [28]. Thus, we here investigated if FOXM1 controlled the transcription of AURKA in meningioma.

Fig. 7.

FOXM1 upregulates AURKA and inhibits ferroptosis in meningioma cells. (A) Correlation analysis of AURKA and FOXM1 expression obtained from GEO74385 and GEO136661. R = 0.5–0.8 represents a moderate correlation, R = 0.8–1 represents a strong correlation. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. (B) AURKA mRNA levels in meningioma cells. n = 3 experiments. (C) Immunoblot analysis of FOXM1, AURKA, phosphorylated AURKA in indicated cells. (D) Dual-luciferase reporter gene assays for AURKA promoters in IOMM-Lee cells. n = 3 experiments. (E) ChIP assays shows occupancy by FOXM1 on AURKA promoter in IOMM-Lee cells. (F) Structure of AURKA promoter showing the two FOXM1 binding sites mutation (in yellow), dual-luciferase reporter gene assays for AURKA promoters with ectopic expression of FOXM1 and FOXM1 binding sites mutant. n = 3 experiments. (G) CH157MN cells transfected with indicated constructs, the protein levels of FOXM1, AURKA, and NRF2 were assayed by Western blot. (L) IOMM-Lee cells transfected with indicated constructs and were treated with 6 μM erastin for 24 h, the protein levels of FOXM1, AURKA, and NRF2 were assayed by Western blot. (H–K, M-P) CH157MN and IOMM-Lee cells were treated by 6 μM erastin for 24 h to trigger ferroptosis. n = 3 experiments. (H, M) The cell viability was assayed by CCK-8. (I, N) The lipid formation was measured by MDA assay, (J, O) concentrations of GSH were detected by relative assay kits, and (K, P) the intracellular Fe2+ level was measured by FerroOrange using a fluorescent microplate reader. Data are presented as means ± SD and are analyzed by unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA. n.s for P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

The expression of AURKA was found to be significantly increased in IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells treated with erastin in a manner that depended on both time and concentration. However, the mRNA and protein levels of FOXM1 did not show significant changes in response to erastin treatment (Fig. S14A-D). Nevertheless, when FOXM1 was overexpressed in CH157MN cells, it resulted in increased levels of AURKA mRNA and protein, as well as phosphorylated AURKA. Conversely, knockdown of FOXM1 in IOMM-Lee cells resulted in a decrease in the level of AURKA expression and phosphorylated AURKA (Fig. 7B and C). Additionally, the dual-luciferase reporter assay conducted in IOMM-Lee cells demonstrated that FOXM1 overexpression promoted the transcription of AURKA (Fig. 7D). Furthermore, the ChIP assay provided evidence that FOXM1 has the ability to directly bind to the AURKA promoters at specific region in IOMM-Lee cells (Fig. 7E). In addition, we performed dual-luciferase reporter assays utilizing constructs driven by promoter sequences harboring mutations in the putative binding sites. Notably, mutations in the secondary binding regions of the AURKA promoter led to a significant reduction of promoter activity (Fig. 4F). In meningioma clinical samples, we also confirmed FOXM1 protein was strongly positively correlated with AURKA expression by IHC (Fig. S15A and B). Together, these observations suggest that FOXM1 regulates AURKA expression in meningiomas by acting as a transcription factor.

We further validated the regulatory role of FOXM1-AURKA-NRF2 pathway in determining the susceptibility to ferroptosis of meningioma cells. In CH157MN cells, the overexpression of FOXM1 led to an elevation of NRF2 protein levels and inhibited erastin-induced ferroptosis. The cells became more vulnerable to erastin-induced ferroptosis when AURKA was knocked down or NRF2 was inhibited with brusatol in FOXM1 overexpressed cells (Fig. 7G–K). Similarly, the knockdown of FOXM1 in IOMM-Lee cells resulted in a decrease in the upregulation of NRF2 protein induced by erastin and an increase in erastin-induced ferroptosis. In FOXM1 depleted cells, the overexpression of AURKA or the activation of NRF2 with KI696 resulted in a partial reduction of erastin-induced ferroptosis (Fig. 7L-P). Collectively, these results indicate that FOXM1 suppressed ferroptosis in meningioma cells by modulating AURKA and subsequent NRF2 expression.

3.8. Inhibition of AURKA enhances ferroptosis-induced suppression of meningioma growth

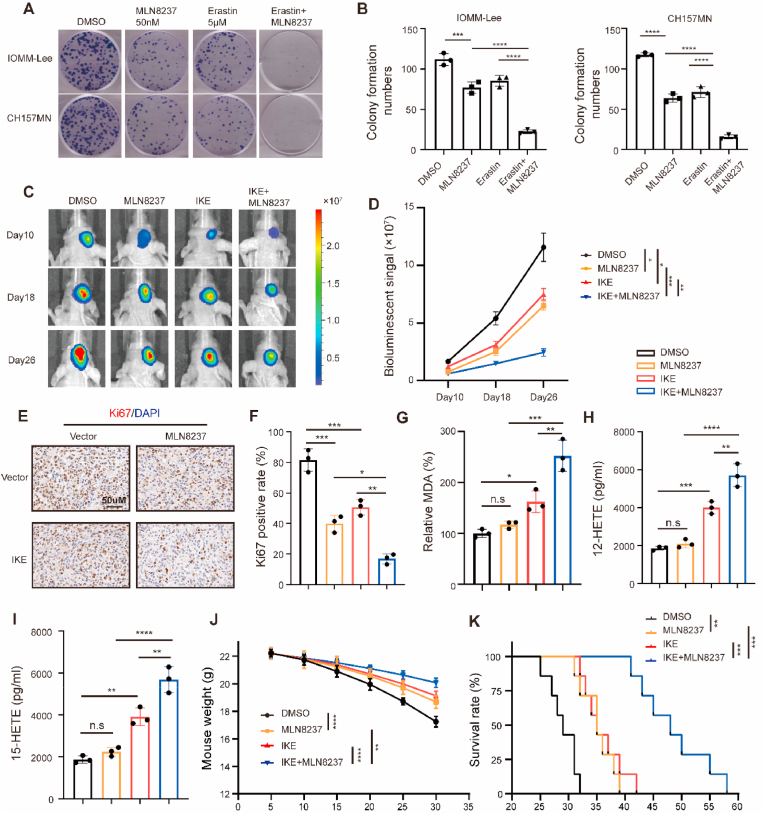

Our study revealed that suppressing AURKA in meningioma cells induces apoptosis and increases their susceptibility to ferroptosis by reducing NRF2 activity. To translate these discoveries into clinical application, we investigated the impact of inhibiting AURKA using MLN8237, individually or in combination with erastin, in models of meningioma both in vitro and in vivo. MLN8237 (Alisertib) is a potent inhibitor of AURKA that effectively blocks phosphorylation of AURKA. Noteworthy, this AURKA inhibitor is the only one that has reached phase III trials, having been tested for various cancers [29]. In the context of meningioma cells, MLN8237 demonstrated a dose-dependent inhibition of meningioma proliferation (Fig. S16A-D). Additionally, MLN8237 significantly suppresses the erastin-induced increase in phosphorylated-AURKA and NRF2 levels, while concurrently reducing the overall AURKA protein level following erastin treatment (Fig. S16E). MLN8237 treatment also increased NRF2 ubiquitination level in meningioma cells (Fig. S16F). When combined with erastin, MLN8237 showed a significant suppressive impact on the growth of meningioma cells, as demonstrated by colony formation assays (Fig. 8A and B). In an orthotopic meningioma model, treatment with MLN8237 led to a deceleration in tumor growth rate, with a more pronounced tumor inhibition observed when MLN8237 was combined with imidazole ketone erastin (IKE), a metabolically stable analog of erastin, which is suitable for in vivo assessment in murine cancer models [30] (Fig. 8C and D). Furthermore, MLN8237 demonstrated the ability to suppress the proliferation of IOMM-Lee cells (as indicated by Ki-67 labeling) in vivo, which was further decreased in the MLN8237 and IKE combination group (Fig. 8E and F). The administration of MLN8237 led to a rise in MDA concentrations, along with an increase in the production of 12-HETE and 15-HETE, which are metabolites of lipid peroxidation. These effects were further amplified when MLN8237 was combined with IKE (Fig. 8G–I). Additionally, the development of orthotopic meningioma led to a significant decrease in mouse weight, which was mitigated by administering MLN8237 or IKE, and further improved when both interventions were combined (Fig. 8J). Importantly, the administration of MLN8237 demonstrated an extension in the survival time within the model of orthotopic meningioma, which was further augmented upon the combination of MLN8237 with IKE (Fig. 8K).

Fig. 8.

Combination of MLN8237 with erastin inhibits meningioma growth in vitro and in vivo. (A) Colony formation assays in IOMM-Lee and CH157MN cells treated with 50 nM MLN8237, 5 μM erastin or combination for 10 days. (B) Quantitative analysis of colony formation assay. n = 3 experiments. (C–D) IOMM-Lee cells were implanted into the intracranial of nude mice. Starting on day 5, MLN8237 (20 mg/kg), IKE (40 mg/kg) or the two combinations were administered twice every other day to treat orthotopic meningiomas. Tumor formation was assessed using bioluminescence imaging at days 10, 18, and 26 after implantation. (E–F) IHC assay for Ki-67. Scale bar is 50 μm. n = 3/group. (G) The relative levels of MDA of indicated tumors were measured. n = 3/group. (H) 12-HETE level. n = 3/group. (I) 15-HETE level. n = 3/group. (J) Weight of mice during the experiment. n = 5 mice/group. (K) Kaplan-Meier analysis of animal survival. n = 7 mice/group. Data are presented as means ± SD and are analyzed by one-way or two-way ANOVA. n.s for P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

These findings collectively indicate that the combined inhibition of AURKA and erastin or IKE effectively suppresses the growth of meningioma both in vitro and in vivo.

4. Discussion

In addition to its involvement in mitosis, a growing body of research has indicated that aberrant expression of AURKA functions as an oncogene in the process of tumorigenesis [9]. AURKA contributes to tumorigenesis by actively participating in various cellular processes, including cancer cell proliferation, EMT, metastasis, apoptosis, and self-renewal of cancer stem cells. Analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) UALCAN database reveals that AURKA is significantly upregulated in most tumor types compared to normal tissues [9]. In the current investigation, we have examined the meningioma GEO datasets and our own clinical specimens to ascertain that AURKA amplification is also observed in high grade meningioma. Through in vitro experiments involving loss- and gain-of-function manipulations, we have demonstrated that the overexpression of AURKA, an understudied molecular alteration in meningioma, can facilitate the development of malignant characteristics in both NF2 wild-type and NF2 mutant meningioma. This finding also aligns with the established role of AURKA in other tumor types.

During interphase, AURKA activation occurs through self-phosphorylation at threonine 288 and plays a significant role in various crucial oncogenic signaling pathways by phosphorylating its substrates. Numerous substrates of AURKA have been identified. For example, the oncogenic transcription factors SOX2 and YBX1 have been observed to undergo phosphorylation by AURKA. Phosphorylating SOX2 contributes to preservation of stem-cell-like cells [31], while stabilizing YBX1 promotes EMT, formation of stem cells, and resistance to chemotherapy [32]. AURKA phosphorylates LDHB at Ser162, which enhances its activity in converting pyruvate to lactate, subsequently promoting glycolysis, biosynthesis, and tumor growth [33].

Importantly, the cell possesses several inherent antioxidant defense mechanisms to regulate the presence of reactive species, one of which is NRF2. As a key regulator of the antioxidant reaction, NRF2 governs numerous downstream genes that play a role in preventing or rectifying redox imbalances within the cell. Under normal circumstances, NRF2 protein is kept degradation and its basal level is maintained low by different E3-ubiquitin ligase complexes, mainly the KEAP1-CUL3-RBX1 complex [16,34,35]. When genetic mutations, endogenous stress-induced modifications, competitive binding of other interacting partners, or exogenous pharmacological inhibition prevent the degradation of NRF2, it can subsequently undergo nuclear translocation to start transcribing genes that have the antioxidant response element (ARE). Sun et al. observed that the utilization of erastin in hepatocellular carcinoma cells led to the suppression of NRF2 degradation and a rise in its protein expression [36]. Wang et al. discovered that ROS play a crucial role in activating Mst1/2, which subsequently phosphorylates Keap1 and impedes its interaction with Nrf2. This process effectively hinders Nrf2 ubiquitination and degradation, ultimately safeguarding cells from oxidative harm [23]. In the present research, we employed RNA sequencing to uncover NRF2 as the main downstream effector molecule of AURKA in the defense against erastin-induced ferroptosis. Additionally, we identified KEAP1, rather than NRF2, as a previously undisclosed substrate of AURKA phosphorylation. Following phosphorylation by AURKA at Thr80, the functional role of KEAP1 in promoting NRF2 ubiquitination and degradation was effectively inhibited. Consequently, NRF2 was activated, leading to the translation of downstream antioxidant and anti-ferroptotic target genes, ultimately conferring resistance to ferroptosis in meningioma. Furthermore, our findings offered a potential mechanism of the increase in NRF2 levels induced by erastin.

A previous study has observed a positive correlation between NRF2 expression levels and the World Health Organization (WHO) grade of meningioma. The authors reported significantly higher NRF2 immunostaining scores in WHO grade II meningiomas compared to grade I, suggesting that elevated NRF2 expression is linked to reduced survival rates in these patients [37]. Our current study suggests that the increased NRF2 levels in higher-grade meningiomas could be attributed to the overactivation of the FOXM1-AURKA axis. This supports the notion that elevated NRF2 expression could serve as a valuable biomarker for predicting a higher WHO grade, more aggressive tumor behavior, and increased resistance to ferroptosis in meningioma. Recently, the role of NRF2 and its regulatory mechanisms in the ferroptosis of the most malignant brain tumors, glioblastoma (GBM), has garnered significant attention. NRF2 expression in gliomas were found positively correlated with WHO grades [37]. Several mechanisms regulating NRF2 or the KEAP1/NRF2 pathway have been identified. For example, a ferroptosis regulator P53 has shown a negligible impact on NRF2 gene activity in IDH wild-type glioblastoma [38]. Conversely, the PI3K/AKT pathway inhibits GSK3β activity, stabilizing NRF2. Inhibiting AKT activity in combination with the genotoxic agent Temozolomide, leads to increased ferroptotic cell death in IDH-mutated glioma [39]. Additionally, Src tyrosine kinase activation stabilizes and activates the NRF2 pathway in glioblastoma [40]. The activation of NRF2 also has been associated with the maintenance of the malignant phenotype in various cancers, including lung [41], breast [42] and gastric cancers [43]. Further research to determine whether the mechanisms identified in our study are also present in other tumors with higher incidence and mortality rates would significantly enhance the clinical relevance of our findings.

We also found that AURKA gene transcription was regulated by transcription factor FOXM1 in meningioma. FOXM1, a member of the Forkhead box (Fox) transcription factor family, plays crucial roles in the development and progression of tumors [44]. In meningioma, FOXM1 was first noticed by Laurendeau and his colleagues. They found that FOXM1 mRNA levels markedly increase in meningioma compared to normal tissues, and more so in high-grade meningioma than in grade I tumors [45]. Primary meningioma with atypical characteristics harbors elevated levels of gene expression associated with the cell cycle, such as the FOXM1 transcription factor networks [25]. Thus, FOXM1 has been recognized as a crucial transcription factor in the advancement of meningioma and is gaining increasing notices, however, the mechanisms of it in meningioma progression are still under discovered. In our current investigation, we demonstrated that FOXM1 possesses the ability to impede erastin-induced ferroptosis in meningioma, aligning with the findings of Yang et al. who reported the inhibitory role of FOXM1 in ferroptosis. Their research revealed that FOXM1 hinders ferroptosis in melanoma cells by controlling Nedd4 transcription and causing subsequently degradation of VDAC2/3 [46]. Additionally, in stem cells of breast cancer, FOXM1 transcriptionally activates AURKA expression [28]. Similarly, our study also confirmed that FOXM1 acts as a transcription factor responsible for the upregulation of AURKA in meningioma.

MLN8237, also named as alisertib, is a potent and selective inhibitor targeting AURKA, effectively impeding the phosphorylation and subsequent activation of AURKA. Extensive clinical trials have been carried out to assess its efficacy in various cancer types, and notably, it is the sole AURKA inhibitor to have advanced to phase III evaluation [47]. Previous studies have demonstrated that MLN8237 exerts a significant impact on the susceptibility of cancer cells towards chemotherapy or radiaotherapy. In esophageal adenocarcinoma cells, MLN8237 has been found to augment the efficacy of cisplatin-induced cell death [48]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, the antitumor activity of sorafenib is enhanced by MLN8237, demonstrating a synergistic effect [49]. Intriguingly, recent research has indicated that both cisplatin and sorafenib serve as inducers of ferroptosis [50,51]. Cisplatin operates through the similar mechanisms as erastin, which involve the reduction of GSH levels and the inactivation of glutathione peroxidases (GPXs) have been identified as the underlying mechanisms of action for cisplatin. Sorafenib affects ferroptosis through two main mechanisms. Firstly, similar to erastin, sorafenib hinders the import of cystine mediated by system Xc−, resulting in endoplasmic reticulum stress, GSH depletion, and iron-dependent lipid ROS accumulation. The second mechanism involves the p62-Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. By deactivating Keap1, the substrate adaptor protein p62 inhibits NRF2 degradation and promotes its nuclear translocation when treated with sorafenib. By controlling redox and iron metabolism, NRF2 inhibits sorafenib-induced ferroptosis, and inhibiting NRF2 can increase the resistance to sorafenib. Radiotherapy can directly induce ferroptosis in cancer cells. Following exposure to cytotoxic radiotherapy, ATM, a crucial element of the DNA repair system, becomes activated. This activation results in the decrease of SLC7A11 and ultimately causing ferroptosis in cancer cells [52]. The findings from our current research may offer an explanation on the synergistic effects of MLN8237 in combination with these drugs and radiation therapy. Furthermore, our study provides a mechanistic rationale for combining MLN8237 with ferroptosis inducers to treat meningioma and other tumor types. Erastin and RSL3 are two classical ferroptosis inducer with different mechanism of action. In our study, we discovered that AURKA specifically inhibits erastin-induced ferroptosis, rather than RSL3, by activating NRF2 and subsequently upregulating SLC7A11, FTH1, FTL, and HMOX1, which are upstream regulators of ferroptosis [5]. Therefore, we speculated that the lack of significant regulation on the effect of GPX4 inhibitors like RSL3 upon manipulating AURKA was attributed to the potent role of GPX4 as a terminal regulatory factor in the ferroptosis pathway. Erastin is currently not used clinically for tumor treatment, but as the first discovered drug capable of inducing ferroptosis, it has been widely applied in preclinical studies concern the role and mechanisms of ferroptosis. There also have been attempts to use an erastin analog, PRLX93936, in two phase I/II clinical trials for the treatment of multiple myeloma (NCT01695590) and various advanced cancer forms (NCT00528047). Nevertheless, various ferroptosis inducers and AURKA inhibitors are gaining attention, so it would be of interest to screen those clinical candidates in preclinical meningioma and other tumor models for efficacy and safety in future studies. Further studies are needed towards clinical translation of our findings.

In summary, our findings revealed AURKA as a previously unrecognized molecular participant in the malignant progression of meningioma. Notably, we have provided compelling evidence demonstrating that AURKA functions as a suppressor of ferroptosis by phosphorylating KEAP1, thereby inhibiting NRF2 ubiquitination and activating the translation of NRF2 target anti-ferroptotic genes. Additionally, we confirmed AURKA as a transcriptional target of FOXM1 in meningioma. Overall, this study offers new perspectives on the involvement of AURKA in meningioma and its regulatory mechanism in ferroptosis, highlighting the potential therapeutic strategy of inhibiting AURKA and combining it with ferroptosis inducers for the treatment of malignant meningioma, and possibly other tumor types.

CRediT authorship contribution statement