Abstract

The envelope glycoprotein (Env) of human immunodeficiency virus mediates virus entry into cells by undergoing conformational changes that lead to fusion between viral and cellular membranes. A six-helix bundle in gp41, consisting of an interior trimeric coiled-coil core with three exterior helices packed in the grooves (core structure), has been proposed to be part of a fusion-active structure of Env (D. C. Chan, D. Fass, J. M. Berger, and P. S. Kim, Cell 89:263–273, 1997; W. Weissenhorn, A. Dessen, S. C. Harrison, J. J. Skehel, and D. C. Wiley, Nature 387:426–430, 1997; and K. Tan, J. Liu, J. Wang, S. Shen, and M. Lu, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:12303, 1997). We analyzed the effects of amino acid substitutions of arginine or glutamic acid in residues in the coiled-coil (heptad repeat) domain that line the interface between the helices in the gp41 core structure. We found that mutations of leucine to arginine or glutamic acid in position 556 and of alanine to arginine in position 558 resulted in undetectable levels of Env expression. Seven other mutations in six positions completely abolished fusion activity despite incorporation of the mutant Env into virions and normal gp160 processing. Single-residue substitutions of glutamic acid at position 570 or 577 resulted in the only viable mutants among the 16 mutants studied, although both viable mutants exhibited impaired fusion activity compared to that of the wild type. The glutamic acid 577 mutant was more sensitive than the wild type to inhibition by a gp41 coiled-coil peptide (DP-107) but not to that by another peptide corresponding to the C helix in the gp41 core structure (DP-178). These results provide insight into the gp41 fusion mechanism and suggest that the DP-107 peptide may inhibit fusion by binding to the homologous region in gp41, probably by forming a peptide-gp41 coiled-coil structure.

The envelope glycoprotein (Env) of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) attaches virus to target cells and fuses viral and cellular membranes, releasing the viral nucleocapsid to the cell cytoplasm (reviewed in reference 14). Env is synthesized as a fusion-inactive precursor (gp160) that is cleaved in the biosynthetic pathway to generate the mature, noncovalently associated surface (gp120) and transmembrane (gp41) subunits (21). gp120 binds to the CD4 cellular and chemokine receptors (13, 23, 25), and gp41 catalyzes membrane fusion (18, 19). Cleavage of gp160 positions a hydrophobic stretch of residues (fusion peptide) at the extreme N terminus of gp41 (4, 16) that is believed to initiate fusion by directly inserting into the target cell membrane.

The mechanism of Env-mediated membrane fusion is not known, but precedents set by other viruses suggest that the fusion process involves large conformational changes in Env and movement of Env oligomers in the plane of the membrane (reviewed in reference 3). The best-characterized viral fusion glycoprotein, the hemagglutinin of influenza virus, undergoes dramatic conformational changes when the virus is exposed to mildly acidic pH during receptor-mediated endocytosis (reviewed in reference 36). A critical part of the conformational change involves a transition from a loop to a helix structure in a heptad repeat segment near the fusion peptide, creating an extended, triple-stranded, coiled coil (reviewed in reference 20) that relocates the fusion peptide approximately 100 Å closer to the target cell membrane (the “spring-loaded mechanism”) (5, 7).

Several studies have indicated that conformational changes occur when Env binds CD4 (26, 29, 30). Recently, it has been proposed that Env binding to receptor triggers conformational changes in a coiled-coil (heptad repeat) region in gp41 near the fusion peptide (17). At present, it is not clear whether this change involves altered exposure of the coiled-coil region or a change in conformation such as a loop-to-helix transition as is the case for hemagglutinin activation. The coiled-coil segment probably subsequently associates with a downstream gp41 amphipathic helical segment to form an extremely stable alpha-helical bundle, consisting of an internal, triple-stranded parallel coiled-coil core (heptad repeat segment) with three antiparallel gp41 amphipathic alpha helices packing in the grooves (see Fig. 1B, core structure), as shown in crystallographic studies of gp41 peptides that self-assemble (8, 32, 35).

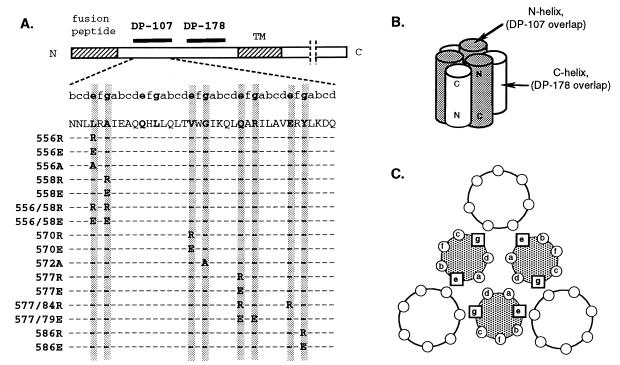

FIG. 1.

(A) Map of gp41 showing heptad repeat residues, mutations, and helical regions and peptides that make up the core structure. (B) Schematic diagram of six-helix bundle of the gp41 core structure, showing overlap with the DP-107 and DP-178 peptides. (C) Cross section through core structure showing position of heptad repeat residues in the coiled-coil domain. TM is the transmembrane region of gp41. The breaks in the cytoplasmic domain indicate that this region is longer than what is shown. Shaded cylinders represent the coiled-coil domain (N helices), which overlaps the DP-107 peptide. White cylinders represent the external helices (C helices), which overlap the DP-178 peptide.

In this report, we describe the results of studies involving mutations in the coiled-coil domain (residues 553 to 595, hereafter referred to as the heptad repeat) near the fusion peptide of gp41 that potentially affect both the stability of the coiled-coil core itself and the interactions with the external antiparallel helices (see Fig. 1A and B). The mutated residues occupy the “e” and “g” positions in the heptad repeat motif (abcdefg) and generally line the groove of the coiled-coil core against which the antiparallel outer helix packs (see Fig. 1C). Several of these mutations also surround a deep hydrophobic cavity that has been proposed as a good target for pharmacological intervention (8). Our studies showed that 14 of the 16 nonconservative mutations in these residues completely abolish fusion activity and that some mutations clustering in one region of the heptad repeat inhibit Env expression. We further assessed the sensitivity of each mutant to gp41 peptide inhibitors predicted to interact with this region and discuss results in the context of structural requirements for Env-mediated membrane fusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and plasmids.

293T, U87-T4-CXCR4, and U87-T4-CCR5 cells and the Env expression plasmid pSM-WT (HXB2) and Env-deficient HIV reporter plasmid pNL43-Luc-R−E− were kindly provided by Dan Littman (New York University, New York, N.Y.). COS-7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). The REV expression vector pREV was kindly provided by Tris Parslow (University of California, San Francisco). Mutant Envs were generated by site-directed mutagenesis from a uridine-substituted single-stranded template (pSM-WT) with the Bio-Rad mutagenesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). Primers used for mutagenesis are available on request. Mutations were confirmed by sequencing with the Sequenase quick-denature plasmid sequencing kit (U.S. Biochemical, Cleveland, Ohio).

Envelope glycoprotein expression.

Approximately 2.5 × 105 COS-7 or 8 × 105 293T cells were plated in six-well dishes (Falcon, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) 1 day prior to transfection so that cells would reach 60 to 70% confluency on the day of transfection. Two micrograms of Env plasmid DNA and 1 μg of pRev DNA were cotransfected with the Lipofectamine reagent (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). After 6 h of incubation at 37°C, Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) was added to the cultures. The cultures were continued at 37°C for 40 h before harvesting for cell-cell fusion assays or immunoblots, as described below.

Env expression in transfected cells was assessed by lysing cells with 0.1 ml of 1% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40)–150 mM NaCl–100 mM Tris (pH 8.0) buffer (lysis buffer). Approximately 10 μl of the clarified lysate was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (4 to 12% NuPAGE gels; NOVEX, San Diego, Calif.) and transferred to an ECL nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.). The membranes were then probed with anti-gp120 polyclonal goat serum (Env 2-3; kindly provided by Kathelyn Steimer, Chiron Corp., Emeryville, Calif.) at 1:5,000 in 5% milk–phosphate-buffered saline, washed, reprobed with peroxidase-conjugated anti-goat antiserum (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and then washed again before detection by chemiluminescence (Amersham) and autoradiography.

Cell-cell fusion assay.

COS-7 cells transfected with mutant or wild-type Envs were assessed for fusion activity as previously described (33). Briefly, approximately 5 × 106 SupT-1 lymphocytes were labeled with 6 μg of calcein-AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) for 30 min and then washed before cocultivation with an equal number of adherent Env-expressing cells. Fusion was scored approximately 1 h after cocultivation by assessing dye transfer to Env-expressing cells under epifluorescence microscopy.

Pseudovirion generation and infectivity assay.

Pseudovirion stocks with wild-type or mutant Envs were generated as previously described (12). Briefly, 3 × 106 293T cells in 10-cm dishes were cotransfected with 5 μg each of the Env expression vector and the Env-deficient viral reporter vector (pNL43-Luc-R−E−) by the Lipofectamine method (GIBCO BRL). The supernatants containing pseudoviruses were collected 48 h posttransfection and frozen at −80°C. Virus quantities were determined by p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Coulter, Westbrook, Maine). One day before infection, 3.5 × 104 U87-CD4-CXCR4 cells were plated in 48-well dishes in DMEM containing 10% FCS, 2 mM glutamine, 1× antibiotics, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 1× nonessential amino acids (DMEM+) and infected with pseudovirus (80 ng of p24) in a total volume of 300 μl containing 8 μg of Polybrene (Sigma) per ml. After 8 h of incubation, 0.5 ml of fresh DMEM+ containing 15% FCS was replaced in the wells, and cultures were continued for 40 h at 37°C. The cells were then lysed, and luciferase activity was measured with the luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and a LumiCount (Packard, Meriden, Conn.) luminometer.

Detection of envelope glycoproteins in pseudovirions.

gp120 in the pseudovirion stocks was assessed by immunoprecipitating 250 ng of p24 pseudovirion stocks that were lysed with lysis buffer with 1 μg of soluble CD4-immunoglobulin G (IgG) (kindly provided by Genentech, South San Francisco, Calif.) while mixing them at room temperature for 1 h. Approximately 25 μl of a 25% suspension of protein A-agarose (GIBCO BRL) was then added to the sample, and the mixture was incubated for an additional hour at room temperature with mixing. The precipitates were then washed three times with lysis buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE (4 to 12% NuPAGE gels), and immunoblotted with the polyclonal gp120 antiserum, as described above.

To detect gp41 in pseudovirions, pseudovirion stocks containing 500 ng of p24 were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 3 h at 4°C to pellet pseudovirions. Pseudovirion pellets were then lysed with 50 μl of lysis buffer, and half of the pseudovirion lysate was applied to SDS-PAGE gels (10% NuPAGE gels), immunoblotted with Chessie 8 antibody (1) (obtained from National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program), and detected by chemiluminescence and autoradiography, as described above.

To detect soluble and pseudovirion-bound gp120 in the pseudovirion stocks, pseudovirion stocks containing 500 ng of p24 were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 3 h at 4°C to pellet pseudovirions. Supernatants were adjusted to 1% (vol/vol) NP-40, and pseudovirion pellets were lysed with NP-40 lysis buffer. The supernatant and pseudovirion fractions were then adjusted to equal volumes with lysis buffer before immunoprecipitation with soluble CD4-IgG, separation by SDS-PAGE (10% NuPAGE gels), and immunoblotting with gp120, as described above. Detection for these blots involved alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody and development with nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate substrate (Promega).

Peptide inhibition assay.

The peptides DP-107 (NNLLRAIEAQQHLLQLTVWGIKQLQARILAVERYLKDQ) and DP-178 (YTSLIHSLIEESQNQQEKNEQELLELDKWASLWNWF) (kindly provided by Carl Wild, Biotech Research Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) were synthesized by 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chemistry, purified by high-performance liquid chromatography on a C18 column, and analyzed by electron spray mass spectroscopy. Then 3.5 × 104 U87-T4-CXCR4 cells per well were plated in 48-well dishes in DMEM+ 1 day before infection and inoculated with 80 ng of p24 pseudovirus containing peptide at the indicated concentration in a total volume of 300 μl of DMEM+ with 8 μg of Polybrene per ml. After 8 h of incubation, the inoculum containing peptide was replaced with 0.5 ml of fresh DMEM+ containing 15% FCS, and cultures were continued for 40 h at 37°C. Infection was determined by the luciferase assay as described above.

RESULTS

Effect of gp41 mutations on Env expression.

Heptad repeat motifs, characteristic of coiled coils, typically contain bulky hydrophobic residues that alternate every third and fourth residue (the “a” and “d” positions) to create a hydrophobic face to an alpha helix (Fig. 1A), (reviewed in reference 2). Residues in the “a” and “d” positions in opposing helices interact hydrophobically to stabilize the coiled-coil structure (Fig. 1C). In addition, ionic interactions in the “e” and “g” positions can influence coiled-coil specificity and have been shown to influence heterodimerization versus homodimerization of coiled-coils, as in the case of the Fos and Jun transcription factors (27). Previous mutational studies of the gp41 heptad repeat segment have shown that mutations in the “a” and “d” positions, particularly helix-disrupting mutations, impair fusion activity (6, 10, 11, 15). In this study, we introduced mutations in the “e” and “g” positions because these residues occupy positions that can potentially interact with the external antiparallel helices as well as helices in the coiled coil itself.

Eight “e” and “g” positions from residues 556 to 588 (HXB2 strain) in the heptad repeat region were mutated to arginine or glutamic acid (Fig. 1A). These nonconservative substitutions were chosen because these amino acids occur naturally in other “e” and “g” positions in the heptad repeat segment and are unlikely to disrupt overall helix structure. In addition, we hoped that these charged residues would facilitate analysis of gp41 peptide inhibitors that are predicted to interact with this region. For the position 572 mutant, alanine was substituted instead of arginine or glutamic acid because the naturally occurring glycine, which is an uncommon residue in helical structures, suggested that only a small amino acid would be tolerated.

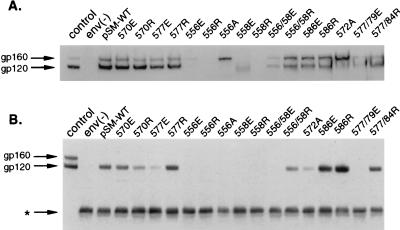

Studies examining transient Env expression in whole-cell lysates showed that both arginine and glutamic acid substitutions in the 556 position (556R and 556E, respectively) resulted in undetectable amounts of Env expression (Fig. 2A and Table 1). An alanine was also substituted in this position (556A) to assess whether a more conservative mutation would be tolerated. This mutant expressed Env but showed impaired cleavage of the gp160 precursor relative to that for wild type. Arginine substitution at the 558 position (558R) also resulted in undetectable amounts of Env, but the double mutant with an arginine substitution in both the 556 and 558 positions (556/58R) restored Env cleavage and expression, though at reduced levels. Glutamic acid substitution in position 558 (558E) resulted in expression of a faster-migrating Env with reduced expression levels. All other single mutants (570E, 570R, 577R, 577E, 586E, and 586R) and two double mutants (556/58R and 577/84R) expressed substantial amounts of Env and showed normal gp160 cleavage. One double mutant with glutamic acid substitutions in positions 577 and 579 (577/79E) showed greatly reduced Env expression compared to that of wild type.

FIG. 2.

(A) Immunoblots of cell lysates transiently expressing wild-type or mutant Envs probed with a polyclonal anti-gp120 antiserum. (B) Immunoblots of wild-type or mutant Env pseudovirion stock lysates probed with a polyclonal anti-gp120 antiserum after immunoprecipitation with CD4-IgG. env(−) is a negative control using REV expression vector only (A) or Env-deficient HIV reporter vector (B). pSM-WT is the wild-type Env. Control is a cell lysate from stable CHO cells expressing Env. Arrows indicate gp120 and gp160 bands. The asterisk indicates IgG heavy chain. Experiments were performed at least three times with similar results.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Env expression and function

| Mutation | Env expressiona | Cell-cell fusionb | % Infectivityc | Virion incorporationd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTe | ++ | ++ | 100 | ++ |

| 556R | − | − | − | NDf |

| 556E | − | − | − | ND |

| 556A | + | ND | − | ND |

| 558R | − | ND | − | ND |

| 558E | + | ND | − | ND |

| 556/58E | + | ± | − | ND |

| 556/58R | + | ± | − | + |

| 570R | ++ | − | − | ++ |

| 570E | ++ | ++ | 76 | ++ |

| 572A | ++ | − | − | ± |

| 577R | ++ | ND | − | ++ |

| 577E | ++ | + | 18 | + |

| 577/84R | ++ | − | − | + |

| 577/79E | + | − | − | ND |

| 586R | ++ | ND | − | + |

| 586E | ++ | ND | − | + |

gp120 and gp160 bands from cell lysates of a representative experiment were analyzed by densitometry (NIH Image 1.60 software). ++, expression ranging from 100 to 45% of wild-type levels; +, expression ranging from 40 to 20% of wild-type levels; −, expression less than 5% of wild-type levels.

Cell-cell fusion was scored by counting dye transfer between fusing cells. Results shown are averages of at least three experiments. ++, fusion activity greater than 75% of wild-type levels; +, fusion activity ranging from 30 to 10% of wild-type levels; ±, fusion activity ranging from 5 to 2% of wild-type levels; −, no detectable fusion activity.

Infectivity of pseudovirions was averaged over three experiments and calculated as described in Materials and Methods. −, infectivity less than 5% of wild-type levels.

gp41 bands from pseudovirion lysates were analyzed by densitometry and averaged from two independent experiments. ++, gp41 detection at 100 to 40% of wild-type levels; +, gp41 detection at 39 to 10% of wild-type levels. ±, gp41 detection at 9 to 5% of wild-type levels.

WT, wild type.

ND, not done.

We also assessed Env expression in the context of virion production, by generating pseudovirions with the mutant and wild-type Envs with an Env-defective, HIV packaging vector (9) (Fig. 2B). gp120 present in these pseudovirion stocks likely represents a mixture of gp120 shed from the cell surface, gp120 secreted in the biosynthetic pathway (31), and gp120 incorporated into pseudovirions. Immunoprecipitation studies of these pseudovirion stocks with CD4-IgG showed that total Env expression in the pseudovirion stocks paralleled overall Env expression in cell lysates with the Env expression vector alone (Fig. 2A). The greater amounts of gp120 than of gp160 in the pseudovirion stocks compared to cell lysates probably reflect several factors, including a high degree of gp120 shedding seen with the HXB2 strain, better binding of gp120 than of gp160 to CD4-IgG (data not shown), and possibly also better incorporation of the cleaved mature Env than of the gp160 precursor into the pseudovirions.

Effect of gp41 mutations on infectivity.

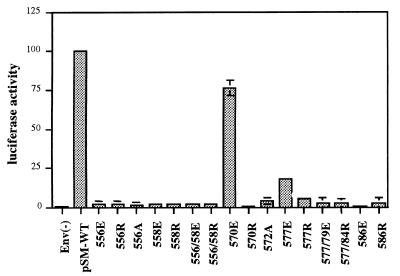

The effects of the gp41 mutations on HIV entry were assessed in a single-round, infectivity assay using pseudotyped viruses generated from the mutant Envs and an Env-deficient HIV packaging vector containing a luciferase reporter gene (12). Our results showed that most positions appeared to be intolerant of nonconservative changes as demonstrated by complete inhibition of infectivity with two different mutations (Fig. 3). Only the 570E and 577E mutants retained significant infectivity. Both of these mutants were impaired in infectivity, with the 570E and 577E mutants showing approximately 76 and 18% fusion activity, respectively, compared to that of wild type. In contrast to these glutamic acid mutants, substitution of arginine in these same positions caused complete loss of infectivity.

FIG. 3.

Infectivity of wild-type and mutant Env pseudotyped viruses. y axis shows luciferase activity as a measure of infectivity as described in Materials and Methods. Luciferase activity is shown as relative luciferase activity units normalized to wild type. Data points are averages of three independent experiments. Error bars show 1 standard deviation each and are absent where standard deviations are too small to show.

Because the single-round infectivity assay depends on virus uncoating, reverse transcription, integration, and transcription and translation of a reporter gene, in addition to Env function to measure infectivity, the effects of the mutation on Env fusion activity were confirmed in a virus-free cell-cell fusion assay (Table 1). The results of these studies paralleled those of the infectivity assay, showing that only 570E and 577E had fusion activity.

Effect of gp41 mutations on Env incorporation into virions.

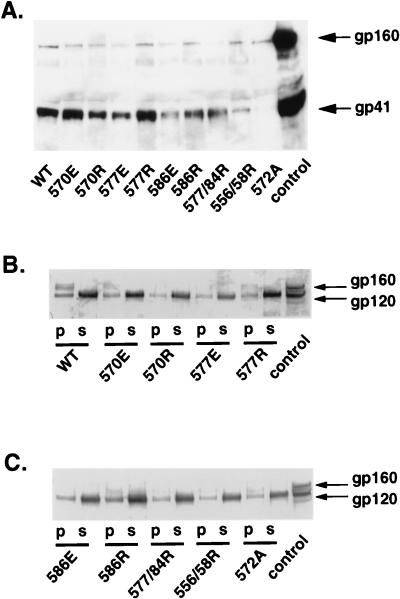

With the exception of the single mutants involving residues in the 556 and 558 positions and the double mutants 556/58E and 577/79E, most mutants demonstrated Env expression in pseudovirion stocks (Fig. 2B), and yet only two mutants (570E and 577E) produced infectious virus. In order to determine more directly whether the gp120 detected in the pseudovirion stocks accurately reflected incorporation of the mutant Envs into the pseudovirions, we pelleted the pseudovirions and probed the pseudovirion lysates for gp41 (Fig. 4A and Table 1). For these studies, we analyzed only the mutants that showed good Env expression in earlier studies. Immunoblots of the pseudovirion lysates showed gp41 bands in all samples, but the levels for 556/58R and 572A mutants were reduced well below those for wild type and the other mutants. The reduced detection of gp41 in the 572A mutant is consistent with the inefficient cleavage of gp160 seen in previous experiments.

FIG. 4.

Incorporation of wild-type and mutant Envs into pseudovirions. (A) Immunoblots of pseudovirion lysates probed with anti-gp41 monoclonal antiserum. Experiments were performed twice with similar results. Arrows indicate gp160 and gp41 bands. (B and C) Pseudovirion stocks were centrifuged to pellet virus, and the pellet (p) or supernatant (s) fractions were then immunoprecipitated with CD4-IgG and immunoblotted with polyclonal anti-gp120 antiserum. Control is a cell lysate from stable CHO cells expressing Env. Arrows indicate gp120 and gp160 bands. These experiments were performed three times with similar results. WT, wild type.

Pseudovirion lysates and supernatants from pelleted pseudovirion stocks were also assessed for gp120 and gp160 by immunoprecipitation with CD4-IgG (Fig. 4B and C). All mutants showed gp120 bands in both pellet and supernatant fractions, confirming incorporation of the mutant Envs into the pseudovirions. We noted better detection of gp120 than of gp41 in the pellet fractions for the 556/58R mutant and especially the 572A mutant, but the reasons for this are not clear. Consistent with the high degree of gp120 shedding with the HXB2 strain, both wild-type and mutant Env pseudovirion stocks showed stronger gp120 detection in the supernatant fraction. Although the relative degree of gp120 shedding between the mutants and wild type was not rigorously quantified, it appears unlikely that the differences could account for the loss of Env function seen in the mutants.

Effect of gp41 mutations on sensitivity to peptide inhibition.

Two peptides (DP-107 and DP-178) corresponding to helical regions in gp41 have been shown elsewhere to be potent inhibitors of HIV infectivity (37, 39, 40) (Fig. 1A). These peptides overlap the gp41 helices that self-assemble to form the gp41 core structure (Fig. 1B). It is believed that the gp41 inhibitory peptides bind gp41 and in a dominant-negative manner prevent the formation of the Env structure(s) required for fusion (22, 24). Recently, it has been shown that the DP-178 peptide directly binds gp41 after gp120 binds receptors, indicating that the heptad repeat domain (DP-107 region) changes conformation and/or becomes accessible during fusion and that changes in the gp41 core structure occur during entry (17). We therefore tested the DP-107 and DP-178 peptides against fusion-competent gp41 mutants.

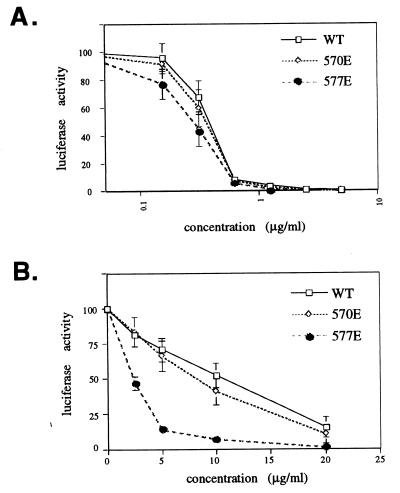

The dose-response curves of the DP-178 peptide against wild-type or mutant viruses did not show significant differences in sensitivity to peptide (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the 577E mutant virus appeared to be more sensitive to inhibition by the DP-107 peptide, giving 50% inhibition at fourfold-lower concentrations than those that are required to inhibit wild-type and 570E viruses (Fig. 4B). This increased sensitivity to inhibition by the DP-107 peptide is probably specific to the 577E mutation and not a consequence of impaired fusion activity, because the 577E mutant can be inhibited by the DP-178 peptide, similar to wild type. This finding suggests that the 577E mutation facilitates binding of the DP-107 peptide to gp41.

DISCUSSION

The heptad repeat segment of gp41 is one of the most highly conserved regions in Env and plays a critical role in HIV entry. In this report, we analyzed the effects of substitution in residues in the heptad repeat that generally line the grooves between the coiled-coil core and the exterior antiparallel helices (Fig. 1C). Mutations in these “e” and “g” positions potentially affect the stability of the coiled coil itself as well as interactions with the external helix to form the core structure. We found that nonconservative mutations at two positions (556 and 558) near the N terminus of the heptad repeat (DP-107) region resulted in undetectable levels of Env expression. These results may be due to misfolding of Env and rapid degradation. However, because the mutations also lie in the Rev-responsive element, impaired expression could relate to problems of mRNA transport from nucleus to cytoplasm. The extreme conservation of the heptad repeat region may be due to the combined selective pressure for Env and Rev function.

Eight nonconservative mutations (570E, 570R, 577E, 577R, 586E, 586R, 556/58R, and 577/84R) generated Envs that were incorporated into virions, processed to gp120, and able to bind CD4, indicating that these mutations probably did not cause major disruption of the Env structure in its native conformation (prior to fusion-inducing changes). Yet only the 570E and 577E mutants were fusion competent. Both of these mutants were impaired relative to wild type; the 570E and 577E mutant Envs showed infectivity at approximately 76 and 18% of wild-type levels, respectively. Although several fusion-incompetent mutants showed reductions in virion-associated Env compared to wild type (577E, 577/84R, and 556/58R), these differences are unlikely to account for the complete absence of fusion function. Therefore, the mutations in the eight fusion-incompetent mutants that showed gp120 and gp41 incorporation in virions likely affect a fusion-active conformation of Env, possibly the core structure. Interestingly, the 570 and 577 residues occupy “e” positions one helical turn away from each other and lie on the same face of the deep cavity shown in the crystallized core structure. For both the 570 and 577 positions, glutamic acid but not arginine substitutions permitted Env function. A neutral mutation from glycine to alanine in position 572 also completely abolished fusion activity.

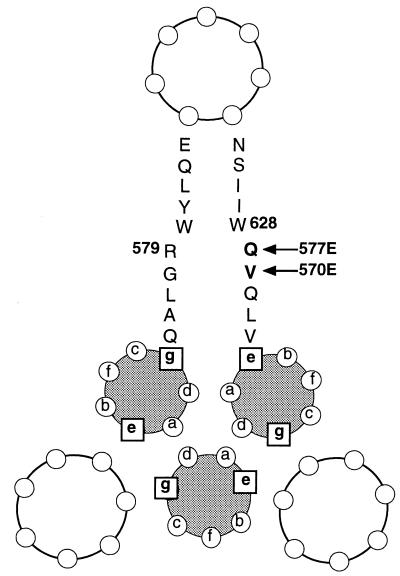

Experiments comparing inhibition of mutant and wild-type viruses by the DP-107 and DP-178 peptides showed differences only with the DP-107 peptide against the 577E virus. The crystal structures of the gp41 core domain indicate that the 570 and 577 positions in the coiled-coil domain are distant from residues corresponding to the DP-178 peptide. Therefore, it is not surprising that inhibition by the DP-178 peptide was not significantly different between the 570E and 577E mutants compared to wild type. The crystallography data also indicate that glutamine 577 has potential for hydrogen bonding with tryptophan 628 of the exterior helix (Fig. 5). Perhaps loss of hydrogen bonding between these residues by the glutamic acid substitution at position 577 contributes to impairment of fusion activity, through destabilization of the interactions between the external helix and the coiled-coil core.

FIG. 5.

Dose-response curves of inhibition by the DP-178 (A) and DP-107 (B) peptides against the wild-type (WT), 570E, and 577E Env pseudotyped viruses. y axis shows luciferase activity as a measure of infectivity as described in Materials and Methods. Data points are averages of three independent experiments. Error bars show 1 standard deviation each and are absent where standard deviations are too small to show.

The crystal structure also suggests ways that the 577E mutant could be more sensitive to inhibition by the DP-107 peptide. Molecular modeling of the 577E mutant using coordinates from the core crystal structure (34) (Insight software; Molecular Simulations Inc., San Diego, Calif.) shows the potential for ionic interactions between glutamic acid 577 in gp41 and arginine 579 in the neighboring coiled-coil helix, representing interactions between “e” and “g” residues in opposing coiled-coil helices (Fig. 6). Conceivably, this ionic interaction may improve binding of the DP-107 peptide to the mutant 577E Env, resulting in greater inhibition of function compared to wild-type Env, which has no potential for ionic interactions with the DP-107 peptide in this position. Molecular modeling of the 570E mutant did not show similar potential for improved binding to the DP-107 peptide. Because data from peptide studies demonstrate that DP-107 and related peptides interact with themselves to form trimeric coiled coils and also interact with DP-178 and related peptides to form heterodimers (8, 22, 28, 32, 34, 38), the DP-107 peptide could block HIV entry by binding to the DP-107 region and/or the DP-178 region in gp41. The increased sensitivity of the 577E mutant (in the DP-107 region) to inhibition by the DP-107 peptide (wild-type sequence) suggests that the DP-107 peptide may work by binding to the homologous region of gp41, preventing formation of the gp41 coiled-coil structure required for fusion.

FIG. 6.

Helical wheel representation of cross section through core structure, showing residues in the “e” and “g” position in the coiled-coil domain and neighboring residues in the external helix. Numbers indicate potential interacting residues (numbering for HXB2 strain). Changing glutamine in position 577 to glutamic acid destroys potential hydrogen bonding with the tryptophan in position 628 and creates potential ionic interaction with arginine in position 579.

These data provide insights into the structural constraints in the gp41 fusion mechanism and also suggest that the heptad repeat region would be a good target for therapeutic intervention. Our data indicate that mutations in this position are often lethal to the virus, so the ability of HIV to mutate and become resistant to inhibitors directed against the heptad repeat region is likely to be very limited.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ira Berkower and Darón Freedberg (Center for Biologics, Food and Drug Administration, Bethesda, Md.) for critical review of the manuscript, Rika Furuta (Center for Biologics, Food and Drug Administration) and Carl Wild (Biotech Research Laboratories) for many helpful discussions, and Terry Oas (Duke University, Durham, N.C.) for molecular modeling of the 570 and 577 mutants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abacioglu Y, Fouts T, Laman J, Claassen E, Pincus S, Moore J, Roby C, Kamin-Lewis R, Lewis G. Epitope mapping and topology of baculovirus-expressed HIV-1 gp160 determined with a panel of murine monoclonal antibodies. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:371–381. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alber T. Structure of the leucine zipper. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1992;2:205–210. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80275-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentz J E. Viral fusion mechanisms. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosch M L, Earl P L, Fargnoli K, Picciafuoco S, Giombini F, Wong-Stahl F, Franchini G. Identification of the fusion peptide of primate immunodeficiency viruses. Science. 1989;244:694. doi: 10.1126/science.2541505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bullough P A, Hughson F M, Skehel J J, Wiley D C. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of fusion. Nature. 1994;371:37–43. doi: 10.1038/371037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao J, Bergeron L, Helseth E, Thali M, Repke H, Sodroski J. Effects of amino acid changes in the extracellular domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1993;67:2747–2755. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2747-2755.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carr C M, Kim P S. A spring-loaded mechanism for the conformational changes of influenza hemagglutinin. Cell. 1993;73:823–832. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90260-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan D C, Fass D, Berger J M, Kim P S. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell. 1997;89:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen B, Saksela K, Andino R, Baltimore D. Distinct modes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral latency revealed by superinfection of nonproductively infected cell lines with recombinant luciferase-encoding viruses. J Virol. 1994;68:654–660. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.654-660.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen S S. Functional role of the zipper motif region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane protein gp41. J Virol. 1994;68:2002–2010. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.2002-2010.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen S S, Lee C N, Lee W R, McIntosh K, Lee T H. Mutational analysis of the leucine zipper-like motif of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope transmembrane glycoprotein. J Virol. 1993;67:3615–3619. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3615-3619.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connor R I, Chen B K, Choe S, Landau N R. Vpr is required for efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 in mononuclear phagocytes. Virology. 1995;206:935–944. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalgleish A G, Beverley P C, Clapham P R, Crawford D H, Greaves M F, Weiss R A. The CD4 (T4) antigen is an essential component of the receptor for the AIDS retrovirus. Nature. 1984;312:763–767. doi: 10.1038/312763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimitrov D S. How do viruses enter cells? The HIV coreceptors teach us a lesson of complexity. Cell. 1997;91:721–730. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubay J W, Roberts S J, Brody B, Hunter E. Mutations in the leucine zipper of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein affect fusion and infectivity. J Virol. 1992;66:4748–4756. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.4748-4756.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freed E O, Myers D J, Risser R. Characterization of the fusion domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein gp41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4650–4654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furuta R A, Wild C T, Weng Y, Weiss C D. Capture of an early fusion-active conformation of HIV-1 gp41. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:276–279. doi: 10.1038/nsb0498-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallaher W R. Detection of a fusion peptide sequence in the transmembrane protein of human immunodeficiency virus. Cell. 1987;50:327–328. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez-Scarano F, Waxham M N, Ross A M, Hoxie J A. Sequence similarities between human immunodeficiency virus gp41 and paramyxovirus fusion proteins. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1987;3:245–252. doi: 10.1089/aid.1987.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughson F. Molecular mechanisms of protein-mediated membrane fusion. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1995;5:507–513. doi: 10.1016/0959-440x(95)80036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lasky L A, Nakamura G, Smith D H, Fennie C, Shimasaki C, Patzer E, Berman P, Gregory T, Capon D J. Delineation of a region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 glycoprotein critical for interaction with the CD4 receptor. Cell. 1987;50:975–985. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu M, Blacklow S C, Kim P S. A trimeric structural domain of the HIV-1 transmembrane glycoprotein. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:1075–1082. doi: 10.1038/nsb1295-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maddon P, Dalgleish A G, McDougal J S, Clapham P R, Weiss R A, Axel R. The T4 gene encodes the AIDS receptor and is expressed in the immune system and the brain. Cell. 1986;47:333–348. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matthews T J, Wild C, Chen C-H, Bolognesi D P, Greenberg M L. Structural rearrangements in the transmembrane glycoprotein after receptor binding. Immunol Rev. 1994;140:93–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1994.tb00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDougal J S, Kennedy M S, Sligh J M, Cort S P, Mawle A, Nicholson J K A. Binding of HTLV-III/LAV to T4+ T cells by a complex of the 110K viral protein and the T4 molecule. Science. 1986;231:382–385. doi: 10.1126/science.3001934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore J P, McKeating J A, Weiss R A, Sattentau Q J. Dissociation of gp120 from HIV-1 virions induced by soluble CD4. Science. 1990;250:1139–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.2251501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Shea E K, Rutkowski R, Kim P S. Mechanism of specificity in the Fos-Jun oncoprotein heterodimer. Cell. 1992;68:699–708. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rimsky L T, Shugars D C, Matthews T J. Determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to gp41-derived inhibitory peptides. J Virol. 1998;72:986–993. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.986-993.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sattentau Q J, Moore J P. Conformational changes induced in the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein by soluble CD4 binding. J Exp Med. 1991;174:407–415. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sattentau Q J, Moore J P, Vignauz F, Traincard F, Poignard P. Conformational changes induced in the envelope glycoproteins of the human and simian immunodeficiency viruses by soluble receptor binding. J Virol. 1993;67:7383–7393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7383-7393.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spies C P, Compans R W. Alternate pathways of secretion of simian immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoproteins. J Virol. 1993;67:6535–6541. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6535-6541.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan K, Liu J, Wang J, Shen S, Lu M. Atomic structure of a thermostable subdomain of HIV-1 gp41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss C D, Barnett S W, Cacalano N, Killeen N, Littman D R, White J M. Studies of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1) envelope glycoprotein-mediated fusion using a simple fluorescence assay. AIDS. 1996;10:241–246. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199603000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison S C, Skehel J J, Wiley D C. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature. 1997;387:426–430. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weissenhorn W, Wharton S A, Calder L J, Earl P L, Moss B, Aliprandis E, Skehel J J, Wiley D C. The ectodomain of HIV-1 env subunit gp41 forms a soluble, alpha-helical, rod-like oligomer in the absence of gp120 and the N-terminal fusion peptide. EMBO J. 1996;15:1507–1514. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White J. Membrane fusion: the influenza paradigm. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1995;60:581–588. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1995.060.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wild C, Greenwell T, Matthews T. A synthetic peptide from HIV-1 gp41 is a potent inhibitor of virus-mediated cell-cell fusion. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1993;9:1051–1053. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.1051. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wild C, Greenwell T, Shugars D, Rimksy-Clark L, Matthews T. The inhibitory activity of an HIV type 1 peptide correlates with its ability to interact with a leucine zipper structure. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:323–325. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wild C, Oas T, McDanal C, Bolognesi D, Matthews T. A synthetic peptide inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus replication: correlation between solution structure and viral inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10537–10541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wild C T, Shugars D C, Greenwell T K, McDanal C B, Matthews T J. Peptides corresponding to a predictive alpha-helical domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are potent inhibitors of virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9770–9774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]